Abstract

This study examines the evolution and integration of Buddhist architecture in East Asia and emphasizes the preservation of indigenous building traditions by adapting pre-Buddhist architectural typologies, vernacular construction techniques, and localized worship practices. In addition, this study highlights the adaptive transformation of Indian Buddhist structures as they incorporate regional architectural forms, resulting in distinct monumental styles that had a profound symbolic significance. By introducing the concept of a cosmopolitan attitude, it underscores the dynamic coexistence and reciprocal influence of universalized and vernacular architectural traditions. The findings highlight the interplay between cultural universality and particularity, illustrating how architectural meaning and intention define the uniqueness of structures beyond their stylistic similarities. This study demonstrates that even when architectural forms appear similar, their function and underlying intent must be considered to fully comprehend their historical and cultural significance.

1. Introduction

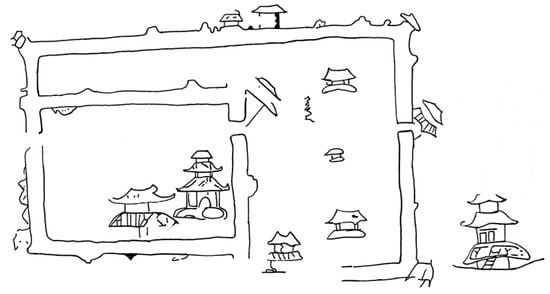

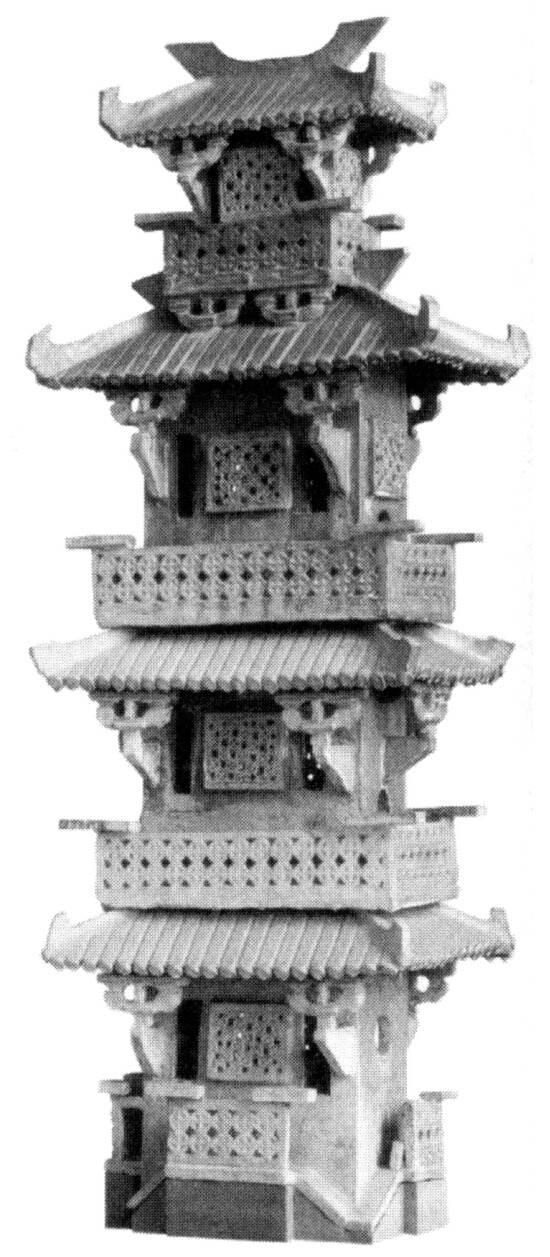

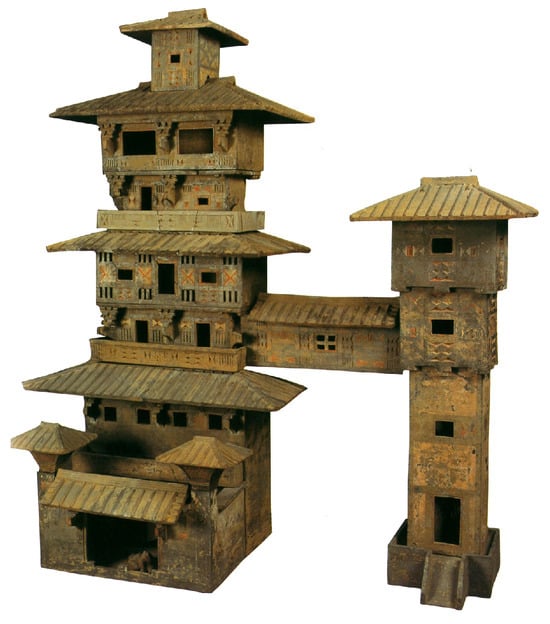

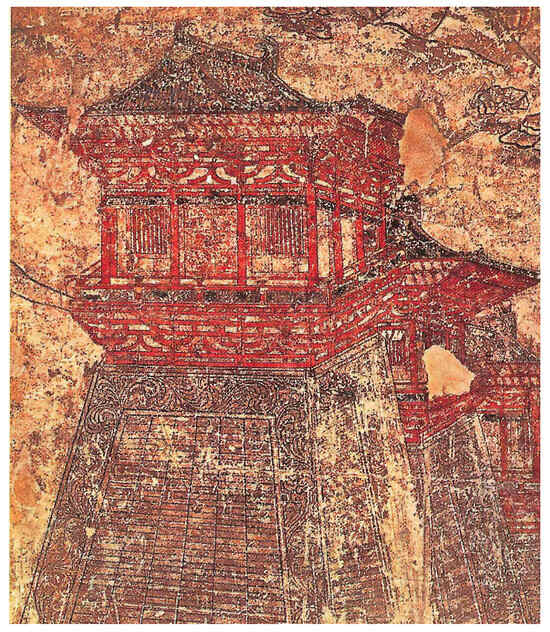

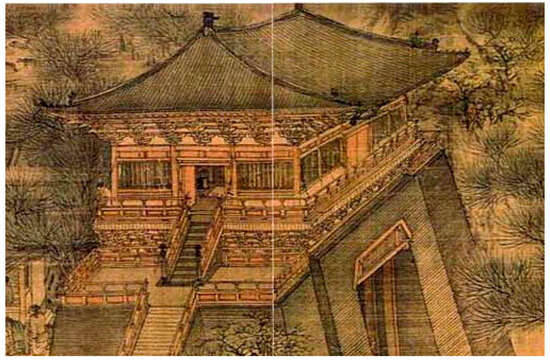

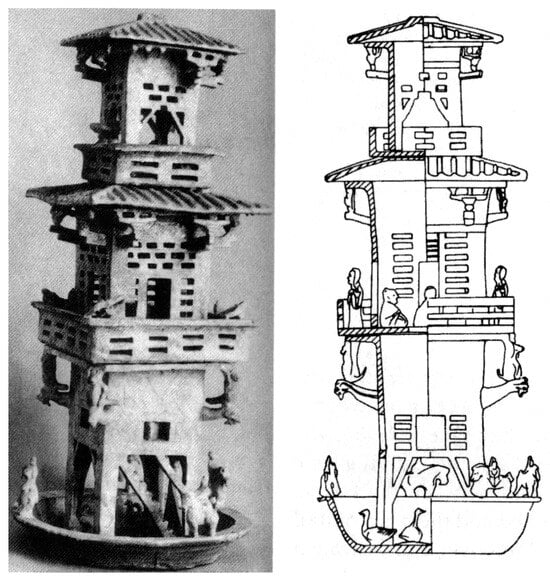

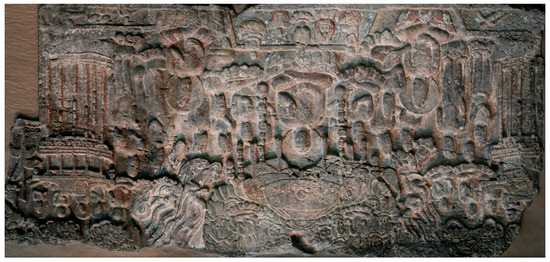

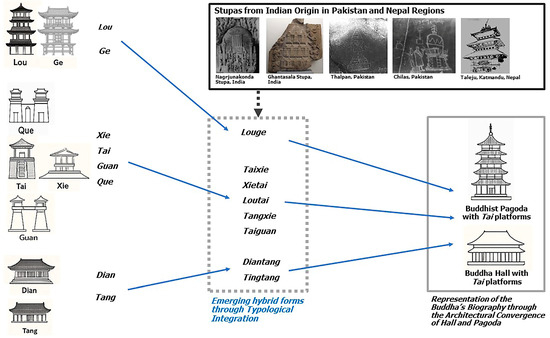

The evolution of Buddhist architecture in East Asia involves a complex adaptation process, integrating pre-Buddhist building typologies, vernacular construction techniques, and ritual spatial arrangements into emerging Buddhist architectural traditions. Existing monuments, such as stupas and cetiyas in the Indian subcontinent, emerged from socio-religious, cultural, and political traditions, influenced by local customs and external architectural elements from Iranian, Greek, and Roman territories. These structures did not arise in isolation but rather reflected diverse origins and developmental trajectories. The stupa closely resembles funerary mounds traditionally constructed from brick and stone in concept and structure. This is believed to have originated either from the thatched hut of the Toda tribes or the hollow cave stupas of South India. Similarly, the cetiya was adapted from vernacular house types, including sabhā, kutāgāra, prāsāda(paśāda), and vihāra, as described in Buddhist literature and depicted in inscribed reliefs (Y.-J. Kim 2015). Building upon these foundational types, the pagoda emerged as a uniquely East Asian architectural form, synthesizing Buddhist and indigenous design elements. The pagoda integrated multistory structural forms with vernacular building types such as lou (樓, multi-story towers), tai (臺, terraced platforms), ge (閣, pavilions), que (闕, watchtowers), guan (觀, observatory pavilions), and xie (榭, open terraced structures). These forms are illustrated in ancient relief sculptures, pottery, paintings, and existing architecture. Early Chinese architects utilized clay models as design tools to aid in construction. The unearthing of these models, often found in tombs, has granted scholars crucial insights into early Chinese architecture, much of which has not endured (Y.-J. Kim 2021). The pagoda merged the stupa with pre-Buddhist designs and transformed into a tiered, tapering structure topped with a sacred finial, showcasing a blend of local architectural styles and Buddhist symbolism (Y.-J. Kim 2024b). The elongated form of the pagoda, inspired by Central Asian architectural traditions, changed the circular plan of the Indian stupa into a four-cornered design with a prominent plinth, increasing its height in accordance with the architectural aesthetics of China, Japan, and Korea. Although square plans were previously employed in the Gandhara Buddhist monuments, their integration into East Asian Buddhist architecture was influenced by Greek–Roman styles in temples and tumuli design (Kuwayama 1978; Kim and Han 2011).

However, this study focused on the conceptual and typological transmission of pre-Buddhist architectural forms, such as lou, tai, ge, que, guan, and xie, within the process of Buddhist adaptation across East Asia. These architectural forms comprise an early vocabulary reminiscent of “skyscraper-like” verticality in pre-modern East Asian architecture. This study examines how these types serve as symbolic and structural frameworks to introduce Buddhist space into newly localized ritual contexts. Ultimately, this study provides a new theoretical framework for understanding Buddhist architectural transformation through the lens of the “cosmopolitan attitude.” By bridging the universal principles of Buddhist architecture with localized adaptations, this research highlights the dynamic interplay between cultural universality and particularity, demonstrating how Buddhist architecture in East Asia emerged as a fluid and adaptive tradition rather than a static transmission of Indian prototypes.

2. Cosmopolitan Attitude for the Adoption of Buddhist Building Types in Ancient East Asia

Although popularized in the twentieth century, the concept of cosmopolitanism traces back to the Cynics of the fourth century BCE, who introduced the idea of being a “citizen of the world.” Rooted in skepticism toward rigid customs, early cosmopolitanism emphasized moral universality over local affiliations. In modern discourse, Appiah (2006) describes cosmopolitanism as an ethical stance marked by openness to cultural plurality, mutual respect, and the transformative potential of cross-cultural interaction.

In the East Asian context, this ethos finds resonance in the Confucian notion of “harmonized yet different” (he er bu tong, 和而不同), as articulated by Yijie Tang (1997). Tang employed this concept as a theoretical framework for integrating diverse ideological systems, particularly in advocating for democratic reform in China, necessitating moving beyond the traditional sangang 三綱 model, an authoritarian and patriarchal order, toward a more inclusive and adaptive coexistence system. This study adapts a theoretical lens originally developed to examine the cultural internalization, particularly how foreign ideologies are received, reinterpreted, and vernacularized in new sociopolitical contexts. This analytical framework, although political in origin, offers valuable insights into how transregional architectural forms such as Buddhist structures are transformed through cultural adaptation. In architectural terminology, this model presents vernacular building types (A) and universal concepts emerging from transregional exchanges (B) not as conflicting entities, but as dynamically coexisting elements. Their interactions produce hybrid forms through mutual adaptations instead of privileging one over another. This framework sheds light on the evolution of Buddhist architecture in East Asia, where pre-Buddhist typologies from vernacular building types (A) were reshaped by the universal principles of sacred prototypes from India (B)—including Bodh Gaya, Sarnath, Lumbini, and Sravasti, which are significant sites in the Buddha’s life. As Buddhism spread into new cultural contexts, it integrated local beliefs and deities, resulting in regionally unique yet doctrinally cohesive architectural forms (Tang 1997, pp. 32–33).

2.1. Philosophical Foundations of Cosmopolitan Architecture

Buddhist thought found a strong alignment with Daoism, Confucianism, and various indigenous traditions in East Asia, which lays the groundwork for the late introduction of Buddhism. This cultural and philosophical harmony eased the acceptance and integration of Buddhism in East Asian cultures, where established religious and political systems affected the transformation of Buddhist architecture.

In this initial scenario from Yijie Tang’s (1997) model, vernacular building types (A) and universalized ideas (B) undergo dynamic exchanges, resulting in various modes of integration and adaptation. The compatibility of Buddhism with preexisting Daoist, Confucian, and indigenous traditions facilitated its cultural acceptance and architectural adaptation. In the second scenario, A interacts with B in ways that enrich A while maintaining its core principles. A notable example of synthesis is the combination of a pagoda and a hall in the central territory of Buddhist temples, which were more ritually and symbolically advanced than the early Buddhist temples of India and even supported the development of various political and religious cults. In Tang’s third scenario, A encounters an aspect within B that directly contradicts an essential principle of A. In such cases, incorporating B requires the partial or total replacement of some elements of A. This change is reflected in how Buddhist architecture adapted in East Asia, where new Buddhist structures gradually replaced some pre-Buddhist forms, establishing a new dominant architectural style. Over time, several Indian and Central Asian Buddhist sites, which initially influenced East Asian Buddhist architecture, were abandoned, combining local building types for political and religious rituals more deeply with indigenous construction techniques and aesthetic preferences. Tang’s fourth case approaches a cosmopolitan attitude. It demonstrates that Buddhist architecture has evolved to adopt a cosmopolitan attitude through the constant exchange between A and B; namely, A interacts with B, and both discover previously nonexistent concepts in their cultures, inventing new ones in the process, resulting in a confluence of their interactions. The interplay between A and B catalyzes the creation and continual reinvention of new architectural forms. In East Asia, Buddhist architecture was not merely an Indian import. Nevertheless, it was redefined and transformed into a distinctive architectural genre that combined universal Buddhist ideals with local building practices and styles.

2.2. Typological Synthesis in Practice

East Asian Buddhist architecture thus evolved not as a replication of Indian models but as a hybridized genre shaped by continuous negotiation between imported Buddhist ideals and local building traditions. This process involved reinterpreting forms, such as stupas and caityas, and their integration into vernacular construction practices. The result was an architectural ethos grounded in cosmopolitan adaptation, where universal religious principles were adapted to region-specific techniques, aesthetics, and ritual needs (Tang 1997; Y.-J. Kim 2024b).

Buddhist structures from India to East Asia are generally divided into two main categories: universal meanings reflected in Buddhist architectural styles and the recognition of local building techniques specific to each area (Cha and Kim 2021). While pre-Buddhist architectural styles were distinct from those in Buddhist temples, the designs for these temples frequently utilized existing regional typologies, especially for commemorative and ritual purposes. Such constructions typically included ceremonial structures honoring local deities and family shrines near tombs. Over time, the adapted Buddhist architectural styles incorporated Daoist and Confucian symbols, leading to a unique blend of architectural forms across East Asia. These local construction methods were preserved and actively incorporated into Buddhist temple design, maintaining their significance and practicality within Buddhist architectural traditions.

The regional adaptation of religious narratives is also evident in Buddhist cave murals, where transformation tableaux showcase localized reinterpretations of Buddhist teachings. A notable example is the Vimalakīrti-nirdeśa Sūtra, one of the earliest Mahāyāna texts, which details the compassionate deeds of Vimalakīrti, a lay bodhisattva, and his philosophical discussions with Mañjuśrī, a key figure in Buddhist doctrine. However, as Ning (1996) argues, the significance of Vimalakīrti in Chinese Buddhist tradition extends beyond his persona. Instead, Chinese engagement with the sutra was driven by its deeper ideological implications, particularly the symbolic debate between Vimalakīrti and Mañjuśrī, which mirrored the political and philosophical tensions between Daoist and Buddhist institutions in China. Although it originated outside of China, the Vimalakīrti-nirdeśa Sūtra was reinterpreted and adapted to fit the sociopolitical context of its time. This contextual adaptation accounts for the text’s remarkable popularity in China (Wang 2005) and demonstrates how Buddhist writings became part of regional discussions to address changing societal needs.

2.3. Material and Structural Adaptation

Cosmopolitan architecture incorporates vernacular characteristics (A) that predate Buddhism while maintaining universal identities (B). This ongoing interaction promotes a vibrant exchange, adaptation, and negotiation, which blends local cultural traditions with universal architectural principles. The cosmopolitan perspective is illustrated in the structural combination of two key building techniques: “piled-up” and “framed” construction. These techniques embody universal architectural concepts in wooden constructions such as the through-jointed framework (column beam-tie style) and beam–column framework (column beam–strut style) (Kim and Park 2017). By contrast, regional construction techniques showcase vernacular influences, such as full-length tie beams connecting all columns and utilizing locally sourced materials.

This cosmopolitan process of architectural adaptation extends beyond Buddhist temples to broader cultural transformations, influencing architectural practices, social identity formation, and political organization. This process, often described as vernacularization, entails the reinterpretation and localization of previously universal architectural principles and orders (Pollock 1996; 1998, pp. 41–42).

As new Buddhist building types met pre-Buddhist architectural traditions, they were adapted in diverse ways. Following Tang Yijie’s third scenario, early Buddhist structures like stupas and caityas, hailing from Indian and Central Asian Buddhist sites, were altered or substituted in East Asia. However, instead of completely relocating, early Buddhist architectural ideas were thoughtfully preserved and incorporated into East Asian Buddhist temple design, enhancing local architectural traditions rather than diminishing them.

The adaptation and synthesis process is apparent in Buddhist sites outside the Indian heartland, including Nagarjunakonda, Thotlakonda, Bavikonda, and Salihundam in India (Y.-J. Kim 2024a). Despite being unrelated to major locations in Buddha’s biography, these sites prominently feature apsidal architectural forms that predate the arrival of Buddhism (Fogelin 2004). Even after the introduction of Buddhism, apsidal structures persisted, serving both Buddhist shrines and Hindu temples. This continuity highlights the cross-religious adaptation of architectural forms, demonstrating their resilience and shared symbolic significance across diverse regions (Ray 2009; Kim and Han 2011).

Although some early Buddhist architectural styles vanished in certain regions, their conceptual foundations and spatial configurations remained deeply embedded in East Asian Buddhist architecture. This illustrates that Buddhism did not enforce uniformity but instead promoted architectural diversity. As a result, universal Buddhist ideals and vernacular traditions coexisted, culminating in a unique East Asian Buddhist architectural heritage.

The universality of culture is fundamentally tied to its diversity and particularity as it emerges from the integration of various traditions. Cultural particularity does not imply an isolated indigenous identity, and instead it coexists with universal influences that are constantly reshaped by intercultural interactions (S.-y. Kim 1995, pp. 313–20). The introduction of new building typologies based on foreign architectural concepts facilitated cultural exchange between these new Buddhist structures and pre-Buddhist building types, including dian (halls), lou (tall buildings), and ge (pavilions with vertical, straight columns). As East Asian societies observed the interchange among diverse architectural styles, they began to recognize commonalities within these differences, fostering a shared architectural identity.

Developing high-rise buildings, like pagodas, enhanced earlier construction techniques and led to new architectural styles, including palaces, homes, towers, and elevated structure platforms. The mutual influence between Indian and local vernacular architecture was vital in developing East Asian architectural principles. Although Indian architectural features were slowly adapted or replaced, essential building types—such as Buddha pagodas and monastic halls—successfully incorporated Indian and local influences, ultimately aiding the evolution of unique East Asian architectural traditions.

Consequently, Buddhist architecture evolved as an adaptive form, integrating Indian cultural elements while preserving local architectural characteristics. The infusion of Indian architectural principles into East Asian traditions fostered a harmonious synthesis between the two cultural spheres. With its cosmopolitan worldview, Buddhism provided East Asian societies, particularly social and religious elites, the means to assimilate Indian and Chinese cultural and technological elements while retaining and redefining their indigenous traditions within a Buddhist architectural context.

2.4. Meaning-Making in Architectural Forms

Architecture is inherently meaningful—no structure exists without significance. Perceiving architectural form requires attention to visual, functional, and conceptual dimensions, as buildings may appear typologically similar yet reflect divergent cultural meanings. As Pérez-Gómez (1983, p. 325) notes, “Buildings may be identical typologically… but their meaning is very different.” Similarly, Sullivan observed, “The Roman temple can no longer exist… Such a structure must… be a simulacrum” (Sullivan 1947, p. 39). Formal similarity alone cannot define architectural meaning; it must be read in relation to ritual use and cultural worldview (Vidler 1977).

This is evident in the transformation of the Indian stūpa into the East Asian pagoda. Though sharing features like verticality and tiered forms, the pagoda evolved through vernacular adaptation, incorporating East Asian elements such as lou, ge, and tang. Buddhist architecture did not replicate Indian prototypes but was reshaped by local cosmologies and building traditions.

The East Asian pagoda derives from Indian Buddhist multi-storied halls. When the White Horse Monastery was founded in Luoyang in 68 CE under Emperor Ming, Indian architectural models entered China. The Weishi describes temple-stūpas as “many-storied structures” called futu, a transliteration of “Buddha.” Historical records such as the Sanguozhi and Hou Hanshu depict Futu-si as a double-eaved pavilion with nine stacked disks, fusing Indic religious forms with Chinese ancestral worship and Daoist symbolism. The Daoist dew basin (lupan 露盤), placed atop pagodas to attract immortals, further exemplifies this ontological synthesis of pre-Buddhist traditions. The shift from “ci” 祠 to “si” 寺 parallels Buddhism’s institutional establishment in East Asia (Y.-J. Kim 2024b).

Cosmopolitan Buddhist architecture must thus be understood as hybridized not just stylistically, but ritually and ontologically. A tiered structure may serve various meanings—housing relics, invoking ancestors, or symbolizing cosmic ascent—depending on context. This hybridity reflects the principle of “harmonized yet different,” where universality and particularity intersect dynamically. Ultimately, architecture is never neutral. Forms like the stupa, pagoda, or pavilion embody the metaphysical values and ritual practices of their societies. East Asian Buddhist architecture, far from a derivative form, stands as a layered, localized rearticulation of transregional spiritual ideals.

3. Pre-Buddhist Tall Building Types in East Asia: Adaptation and Adoption

3.1. Tai, Xie, Guan, and Que Buildings

Monastic building compounds in East Asia have evolved from pre-existing architectural forms, including pavilions (ge, lou), watchtowers (que, guan), halls (tang, dian), and elevated terraced platforms (tai, xie). These tall structures were originally developed in northern China, where wooden and earth works were integrated into high-rise constructions. The early development of towering structures was closely linked to tai architecture, which significantly shaped the architectural landscape of pre-Buddhist East Asia. High terraces first appeared during the Shang dynasty and were extensively built for defense during the Warring States period (475–221 BCE). The origins of platform buildings traced back to the Spring and Autumn period (770–475 BCE) and the Warring States period when ongoing conflicts among competing principalities required elevated designs for protection and observation.

Nevertheless, with advancements in military technology, defensive strategies shifted from high platforms to robust walls accompanied by deep moats, which were more effective in protection. Over time, the meaning and function of these elevated structures expanded, incorporating elements from other building types, including ge, lou, dian, and tang. Tai, for instance, often comprised rammed earth foundations combined with timber-framed structures, forming large, multi-functional architectural complexes (M. Chen 1990). The construction of high-profile platforms involves the excavation and compaction of soil by combining additive (layering) and subtractive (excavation) techniques to ensure structural integrity and long-term stability.

3.1.1. Technological Developments in Tall Building Construction

The rise of high-rise construction techniques was directly linked to advancements in ramming technology, which involved using poles, sticks, wedges, and straw ropes to stabilize ramming molds. By the Western Zhou and Spring and Autumn periods, builders discovered that mixing loess with water produced a material with high plasticity, encouraging both pottery production and architectural innovation. By the third century, the wood-box tamping method became widespread in Korea, where it was used to construct rammed earth walls for Hanseong City, the first capital of the Baekje Kingdom. Archaeological evidence suggests that wooden planks were assembled to form square molds, into which soil was poured and compacted. This process was repeated in staggered layers, with the straw placed between levels to reinforce the structure. The remnants of these walls reveal a trapezoidal cross-section, 40 m in width and 15 m in height, indicating that the original structures were considerably taller. Historical texts also reference the construction methods used for tai buildings. The Guanfuji 關輔記describes the Liangfeng-tai (涼風臺, Cool Breeze Terrace), located north of the Jianzhang Palace 建章宫 built during the reign of Emperor Wu of Han (漢武帝, r. 141–87 BCE), as being constructed by layering wooden elements to form a complete structure (Q. He 2005, p. 288; Ho 1985; Zhang 2003). This description closely resembles Jinggan 井干 construction techniques involving stacking interlocking wooden beams. Similarly, the Shigongshi of the Shiming 釋名 defines tai as “a platform supported by rammed earth, elevated for observation,” further reinforcing its role as a multi-functional structure. Archaeological discoveries confirm that during the Warring States period, the dominant architectural forms included palatial complexes and ritual halls built on platforms, often part of fortified cityscapes comprising rammed-earth walls and multi-material constructions. Laozi’s Dao De Jing references this architectural tradition, stating that “a nine-story building is constructed by piling up a handful of loess or earth” illustrating the persistent use of rammed-earth foundations in ancient East Asian architecture.

3.1.2. Tai, Xie, Guan, and Que: Function and Evolution

The Shuowen Jiezi defines tai as “a structure built for observation, which must be elevated” (Xu et al. 2004). In the Erya’s Shiya chapter, it is stated that “the du 闍 (watchtower) is the tai (platform)” (Chi and Wang 1997b, p. 43), further reinforcing its function as an elevated vantage point. Similarly, the Shigong chapter of the Erya describes “the du speaks the tai,” indicating the close relationship between these structures’ forms and purposes. Guo’s commentary on the Erya elaborates on this distinction, noting that “the tai is constructed for panoramic observation, whereas the xie 榭 comprises a wooden framework.” Additionally, the commentary states that “the tai is built by layering earth to create an elevated mound,” while Li Xun 李巡 clarifies that “the piling of earth serves the purpose of creating an observation platform” (C. Xu 1987, p. 175). Furthermore, “a structure raised by amassing earth is referred to as a tai, whereas buildings supported by timber construction are called xie.” The Yishu 義疏 also supports this interpretation, stating: “xie is a house or pavilion constructed with a wooden framework and built upon a platform (tai)” (C. Xu 1987, p. 175). This definition implies that a wooden structure (xie) was often erected atop a preexisting earthen terrace (tai), creating a multifunctional space that combined stability with architectural refinement. A poetic illustration of this architectural relationship appears in the “Zhaohun” (Summoning the Soul) chapter of the Chuci 楚辞, which provides an abstract depiction of these structures: “Layering the tai, accumulating the xie, and gazing upon the distant mountains.” This passage indicates that tai and xie were frequently combined, with tai as an elevated platform and xie as a wooden structure placed upon it, reinforcing their dual functions as observation and ceremonial spaces (Zhu et al. 2018).

The xie was a wooden structure built on a rammed-earth platform, whereas the tai and du were earthen mounds constructed using rammed-earth techniques. Timber buildings were gradually constructed taller on these platforms. This provided convenient vantage points with bird’s-eye views of the surrounding city and suburbs. By the Ming period, the xie had evolved into an open-air pavilion set within gardens or landscapes, becoming synonymous with the ting, a type of pavilion (Ji 1988; Shen 1979). The function and meaning of xie continued to evolve, adapting to various architectural types over time. Only the rammed-earth terrace (tai) appeared in its earliest form, while the wooden pavilion (xie) was added later. This suggests that early terraces and pavilions were likely developed as a combined architectural form, reflecting their gradual functional transformation from purely structural platforms to integrated living and ceremonial spaces. This suggests that tai structures were crucial in martial training, particularly for archery drills and military exercises. The historical text Choe Chiwon’s Yeoljeon 6, Gwon 46 records the following: “Choe Chiwon roamed through mountains and forests, alongside rivers and coastal areas, constructing the xietai 榭臺, which were constructed in natural landscapes for reclusive living and aesthetic enjoyment, further expanding the architectural and functional diversity of these structures.” This highlights the diversity in applying xietai, which could serve both practical and aesthetic purposes, from military training and surveillance to hermitage retreats and contemplative spaces.

The guan and que originated from the taiguan 臺觀, a type of high-rise watchtower. The Erya’s Shigong chapter defines guan as equivalent to que, reinforcing their association with elevated gate structures. According to Guo’s commentary on the Erya, “The gate of the palace comprises two que. The outer gate is called the ringed gate, while the flanking structures are known as guan or que” (Chi and Wang 1997a, p. 78). This suggests that the guan and que were integral to palace entrances, marking hierarchical distinction and ceremonial grandeur. The Gujin Zhu (古今註, Ancient and Modern Commentary), compiled by Cui Bao 崔豹 during the Jin period, further elaborates “The que is the guan. The guan includes a house, and when one ascends the structure, a wider view of the surroundings can be seen” (Chi and Wang 1997a, p. 78). This passage confirms that guan and que were frequently combined in a single architectural form, resembling multi-story buildings with double-eaved roofs. These structures served as watchtowers and administrative centers and functioned as symbolic markers of power and status that reinforced the architectural hierarchy of imperial and religious sites.

The Shuowen Jiezi defines que as “an empty space that leads to a road,” while guan (观) is described as “a structure designed for viewing and observation from elevated ground” (Li and Liang 1983). This distinction suggests that que was traditionally positioned to flank a gate providing access to a walled city. In contrast, guan referred to elevated structures that did not necessarily serve as entry points. The Fengsu Tongyi 風俗通義 offers a clear definition of guan and que, explaining that “Zhao Gong, ruler of the Lu Kingdom, ordered the establishment of a gate between two guan structures, which were then collectively called que” (Li and Liang 1983; Jiang 1988).

According to this definition, when two guan structures were installed on either side of a gate, they became known as que. However, if a guan was built in a location not associated with a gate, it retained its original designation as guan. The Baihu Tongyi 白虎通義emphasizes the social and political significance of que, stating “Why should a gate include que? Because the que serves as a mechanism to differentiate between aristocrats and commoners, controlling access through the gate” (Li and Liang 1983).

Gujin Zhu also reflects this hierarchical function, and states “In the past, guan structures were placed in front of every gate to emphasize the importance of the entrance. The upper levels of the guan provided a vantage point for viewing the surroundings. However, as time passed, officials considered these structures outdated, referring to them as que.” The text also describes the ornamentation of que, noting that “The red-colored roof of the que was polished and whitewashed, while its base was adorned with images of floating clouds, divine beings, mythical creatures, and auspicious symbols. Depictions of the Blue Dragon, White Tiger, Black Tortoise, and Vermilion Bird were also present” (Chi and Wang 1997a, p. 78). This description confirms that que served as symbolic markers of status and authority, much like dian 殿 and tang 堂. However, while dian and tang varied in size and scale, que was categorized according to quantity. For instance, a triple que signified the emperor’s presence, while a double que was reserved for high-ranking officials (Paludan 1991, p. 34). Architecturally, guan was rarely constructed as a standalone building. Instead, it functioned in conjunction with lou (multi-story buildings), tai (elevated platforms), and que, with lou and tai often serving as supporting structures that enhanced the guan’s observational purpose.

The Shanhai Jing 山海經 frequently references tai structures, offering several notable examples: tai for Emperor Yao (堯, c. 2356–2255 BCE); tai for Emperor Ku (嚳, one of five legendary emperors); tai for Emperor Dan Zhu (丹朱); and tai for Emperor Shun (舜, c. 2200–2100 BCE). These platforms, each featuring a four-sided design, were said to be situated east and north of Kunlun Mountain (modern-day Xinjiang) (Yang and Qiu 1999, pp. 324, 367, 421, 445). Additionally, the text describes a cone-shaped platform used for military defense, stating that “Archers could not shoot westward, fearing the exposure of the open terraced platform. The Xikun Mountain housed the God of Water (共工) platform, and even the most skilled archers hesitated to fire northward” (Yang and Qiu 1999, p. 445).

The Mutian Zizhuan 穆天子傳 provides further insights into the use of tai structures by emperors, noting that “The emperor constructed a tai and resided in the western quarters to escape the heat of the world. The Son of Heaven is responsible for upholding the tai, which is fortified with multiple walls, resembling a form of rampart. (Zheng 1992, p. 113). These accounts indicate that tai structures were utilized for observation and functioned as imperial retreats and defensive structures.

The Erya’s Shigong 釋宮 chapter describes the progressive elevation of tai structures, stating that “The tai becomes higher and higher by accumulating earth around it. The lou is characterized by its narrow yet elaborately decorated walls” (C. Xu 1987, p. 175). In this architectural hierarchy, the lou functioned as a house constructed atop a tai, resulting in multi-story buildings that combined earthen and wooden frameworks. Historical sources further elaborate on this relationship, noting that houses (wu 屋) built on elevated platforms (tai) were commonly transformed into lou structures, encompassing both single-story and multi-story forms (D. Guo 2003, p. 102; Zhu 1996, p. 249).

The Daode Jing describes the Ling-tai (靈臺, Spirit Altar) as a raised, high structure used by kings, particularly during famine. The text notes that “A tower, tai, of nine storeys was raised out of the mud”. Berglund (1990, pp. 257–67) suggests that Buddhism incorporated several pre-Buddhist religious elements and architectural features in China, and that the Ling-tai may have served as a prototype for the later pagoda. This connection is reinforced by wooden watchtowers (guan or que) and multi-storied pavilions (lou or ge), which share structural and symbolic similarities with Buddhist architecture.

With the spread of Buddhism, secular and military structures such as tai, lou, and ge were repurposed into sacred spaces. This transformation is evident in the Samguk Yusa 三國遺事, particularly in the section “Jajang Establishes the Monk’s Discipline,” where it is recorded that “The image brought by Sakra said, ‘Even though you study myriads of doctrines, nothing will ever surpass this verse.’ Then, entrusting him with Buddha’s robe and relics, he vanished. Jajang, a Silla monk, knew he had received a holy writ. He descended to the Northern-tai, passed Taihe Lake, and entered Chang’an city.”

The tai, in this context, is defined as an altar for enshrining sacred images. The Samguk Yusa, in Eosan Bulyeong (魚山佛影, Fish Mountain Buddha’s Shadow) section of Tapsang (塔像, Pagodas and Images), further describes the use of tai in Buddhist religious practice, stating “At this moment, a dragon king made a seven-treasure-platform and offered the Tathagata the platform”. Additionally, another passage describes an event where “A slave crashed through the roof via a crossbeam and moved toward the western side. He was transformed into a true body as soon as he discarded his physical body and sat upon the lotus platform 蓮臺, radiating light.” These references show that tai evolved into a key Buddhist altar form shaping the construction of pagodas and temples. The Samguk Yusa discusses various architectural types—including tai, xie, tang, and dian—highlighting their evolution and integration into Buddhist monastic environments. A particularly illustrative example is King Gyeongdeok’s commission during the Tang Dynasty, where artisans constructed an artificial mountain ten feet high on a five-colored woolen textile. This Manbulsan (萬佛山, Ten Thousand Buddhas Mountain) was an elaborate representation of hills, streams, flowers, trees, birds, butterflies, temples, monks, nuns, countless Buddha statues, and sandalwood carvings adorned with gold and jewels. The text also describes the incorporation of various Buddhist structures, including louge (百步樓閣, multi-story pavilions of a hundred steps); taidian (臺殿, altar halls or halls on elevated terraces); and tangxie (堂榭, monastic hermitages). The taidian, based on historical interpretations, likely referred to halls built upon terraces or platforms, while tangxie functioned as hermitages for monastic communities, possibly influenced by pre-Buddhist retreat structures.

3.1.3. Architectural Evolution and Adaptation in Buddhist Contexts

Early architectural forms varied; the tai, xie, guan, and que constructions fulfilled similar functions across different contexts, including watchtowers for surveillance, residences for rulers and aristocrats, venues for religious and ritual performances, and pavilions for retreat and contemplation. Over time, these functions were centralized within the tai structure, which combined materials, construction techniques, and design elements from other building types. The construction methods of tai, xie, guan, du, and que primarily relied on stacking timber members in successive layers atop a rammed-earth platform. This technique later influenced the construction of Buddhist multi-story structures such as pagodas. This “piled-up” structural method became a defining characteristic of East Asian wooden architecture, demonstrating continuity from pre-Buddhist military and administrative buildings to Buddhist temple complexes (Nakamura 1986; Kim and Park 2017).

The historical development of que, guan, tai, and lou reflects a continuous process of adaptation, wherein structures intended initially for defensive or hierarchical purposes gradually evolved into symbolic, ritualistic, and multi-functional buildings. Que served as monumental gate structures, reinforcing political authority and social stratification. Guan functioned primarily as watchtowers, providing elevated vantage points. Tai structures originated as earth-work platforms, later integrating timber frameworks to support additional architectural forms. Lou emerged as an extension of tai, transforming into multi-story residential and ceremonial buildings.

These pre-Buddhist architectural traditions were gradually incorporated into Buddhist temple complexes, influencing pagoda designs, monastic halls, and ceremonial altars. This process highlights the dynamic interplay between indigenous architectural practices and imported religious structures, illustrating how pre-existing building types were adapted to meet Buddhist architecture’s spatial and symbolic needs. The steady adaptation of tai-based structures into Buddhist architecture led to the emergence of new hybrid forms, including taixie 臺榭 or xietai 榭臺—combining terrace platforms (tai) with wooden pavilions (xie); loutai 樓臺—integrating multi-story buildings (lou) with terraces (tai); tangxie 堂榭—referring to monastic hermitages or ascetic retreats; taidian—temple halls situated on elevated terraces; and taiguan 臺觀—watchtowers or elevated observation platforms within monastic or palace complexes.

These early building innovations showcase the continuous interaction between indigenous East Asian architecture and Buddhist religious designs. The incorporation and advancement of these styles reflect the enduring influence of pre-Buddhist structures on subsequent Buddhist architecture, highlighting the ever-evolving relationship between cultural adaptation and architectural development.

3.2. Dian and Tang: Architectural Distinctions and Evolution

3.2.1. Dynamic Evolution of Tang and Dian Architecture

The Yingzao Fashi (State Building Standards) differentiates tang and dian, highlighting their distinct functions and structural characteristics. However, early East Asian texts exhibit considerable variation in their definitions and uses of these terms. The Shuowen Jiezi defines tang as dian, which implies that these two terms originally synonymous. Similarly, the Boya 博雅 equates tang with huangdian 皇殿, which means “palatial hall for an emperor.” Meanwhile, the Cangjiepian 倉頡篇 describes dian as “the dating (great hall),” reinforcing its association with imperial and ceremonial architecture. According to Xu Jian 徐堅, “Before the Shang and Zhou periods, the terms dian and tang were not in use. Their emergence coincided with the qiandian (前殿, front halls) construction during the Qin Dynasty.” The Yihun 義訓 records that the term dian referred to a hall during the Han period, whereas in the Zhou period, the equivalent term was qin 寢. The Shiming, an early lexicographical text attributed to Liu Xi 劉熙, dating from around 200 CE, further elaborates: “Tang represents a grand and conspicuous structure, while dian refers to the domain in which the hall is situated (diane 殿鄂) “ (Xi Liu 1959).

These historical texts indicate that tang and dian were sometimes used interchangeably, although their meanings diverged gradually. The Cangjiepian, compiled by Li Si (李斯) during the Qin Dynasty (221–206 BCE), states that dian was historically larger in scale than tang and that the dian predates tang, emerging after the Shang-Zhou period. The Boya, an expanded version of the Erya, compiled by Zhang Yi (张揖) during the Wei-Jin period (221–439 CE), similarly describes tang as huangdian, suggesting that tang was an imperial hall. Meanwhile, the Shuowen Jiezi, authored by Xu Shen (许慎, 55–149 CE), provides one of the earliest recorded definitions of tang and dian, reinforcing their synonymous usage during the Han period (Miller 1953, p. 69; Loewe 1993).

However, the Cangjiepian emphasizes a hierarchical distinction, stating that dian structures were elevated above tang buildings, symbolizing higher social status. Despite this distinction, dian and tang shared similar social functions, leading to architectural similarities. Both dian and tang buildings were constructed using the “sia” (四阿, four-sided structures) method, a traditional East Asian architectural technique. The sia structure comprised a ridge beam (tong 棟) at the apex of the roof, four corner beams (“a” 阿) connecting the roof to the supporting walls, and a well-framed configuration (“jing 井”) of transverse and longitudinal beams. The “sia” construction is characterized by a hipped roof, forming a four-cornered structure representing the primitive form of palace halls (gongshi 宫室). The Zhouyi 周易 describes this technique as “a ridgepole rises, and a roof falls,” or “A ridgepole above and rafters below” (shangdong xiayu 上棟下宇) (Wang et al. 1967).

The Song Dynasty’s Huizong expanded upon this concept in his commentary Benjingxun 本經訓, stating “a” 阿 signifies a bent roof, while zhong 重 represents multiple roof layers. Together, siazhongwu 四阿重屋 refers to a house with a double-eave roof (X. Xiao 2010). The etymology of “a” traces back to its curved shape, originally used to describe bent hills or earthen mounds, 丘阿, 曲阿也. Tanaka Tan (Tanaka 1989, pp. 334–35) further elaborates that the sia structure comprises a ridge beam and four supporting columns, creating a four-cornered building with a hipped roof. This architectural concept originated in the Shang period, where “a” referred to building corners, reinforcing the structural stability of palace halls. By the Song Dynasty, the meaning of sia shifted, as recorded in Juan 54 of the Song Shi: “The ‘e’ is positioned at the four corners, with a double-eave roof supported by four columns. The four ‘e’ buildings are constructed at the corners of the Luminous Hall, forming a square foundation upon which the central hall is situated” (D. Guo 2003, pp. 167–68). This description highlights a transformation in architectural meaning, where sia evolved from a structural concept into a layout for ritual buildings surrounding a religious mound.

Thus, the tang and dian became recognized as the principal halls of grandeur, typically constructed atop elevated platforms. While both terms refer to similar building types in function and architectural form, historical records indicate differences in scale and status. Over time, their meanings diverged, as documented in the “Shigongshi” 釋宮室 of the Shiming. Tang is an imposing, majestic structure, emphasizing its elevated and splendid design. The Shiming, compiled later than the Shuowen Jiezi, differentiates tang and dian. It describes dian as representing an authoritative domain, where the sacred realm of rulers was demarcated from lower, subordinate spaces. This classification suggests tang symbolized an architectural grandeur, while dian conveyed political and religious sanctity, reflecting hierarchical and territorial authority.

The historical development of dian and tang illustrates their transformation from interchangeable terms to distinct architectural types. Key observations include the following: Dian buildings were initially larger and of higher status than tang, though both structures shared functional and formal similarities. Both dian and tang were constructed using the sia framework, which evolved into the well-framed, hipped-roof form typical of imperial halls. Sia referred to structural components and ritual spaces in religious architecture during the Song period. Over time, these architectural elements were incorporated into the construction of Buddhist temples, shaping monastic halls, ritual buildings, and imperial temple complexes. This continuity highlights the interaction among East Asia’s palatial, religious, and vernacular traditions and architecture.

The Samguk Sagi 三國史記 and Samguk Yusa provide additional insights into the functional distinctions between tang and dian. These texts reveal that the tang was primarily associated with annexes of palaces, Buddhist temples, administrative offices, and platforms. By contrast, the dian served as official venues for rulers to reside and conduct state affairs. In historical records, tang appears in multiple sacred and ritualistic contexts, including Western 西堂 and Eastern 東堂 Halls, used to store coffins of deceased rulers before funerals and later as royal family shrines 願堂. Ancestral shrines, 祠堂, are dedicated to enshrining spirit tablets. State ritual structures, such as the Luminous Hall (明堂), were where state-sponsored rituals were performed to ensure ruling elites’ well-being, prosperity, and legitimacy. One prominent example is the palace temple constructed in Luoyang in 688 CE under the order of Empress Wu Zetian 武則天. Historical records describe the structure as 294 chi in height, with a square base measuring 300 chi.

Three narratives each embody distinct cosmological concepts: the foundational tale illustrating the four seasons; the intermediate tale portraying the twelve earthly branches, integral to the Chinese method of measuring time alongside the ten heavenly stems; and a domed roof sustained by nine dragons, topped with a gilt metal phoenix, measuring one zhang high (Fu 2001, pp. 409–14). These majestic ritual halls reflect tang structures’ symbolic and cosmological significance, emphasizing their ties to ancestral veneration and the alignment of celestial energies.

Contrastingly, dian accomplished state and political functions. Historical records demonstrate that dian housed rulers during their governance and ceremonial duties, differentiating it from tang, which served for religious and ancestral veneration. Thus, a clear distinction emerged in these texts: Tang was dedicated to gods, ancestors, and celestial rituals. Rulers used dian for state administration and governance.

The Samguk Yusa records that tang and dian were adapted into Buddhist architecture, which was used interchangeably in monastic settings. Various monastic halls (tang) are described, including Main Buddha Hall 金堂 or 佛堂, Dharma Hall 法堂, Sacred Hall 殿堂, Monastic Hall 堂宇, Zen Dharma Hall 善法堂, Dining Hall 食堂, and Lecture Hall 講堂. In Buddhist monasteries, tang and dian served as sacred spaces for rituals and communal practices, suggesting that their earlier hierarchical distinctions gradually diminished in religious contexts. By the Goryeo period, a new classification system emerged, differentiating the functions of tang and dian within Buddhist temples. Contrary to earlier conventions, historical literature from Goryeo Korea reveals that dian became associated with halls that enshrined Buddhist images, where monks and laypeople conducted rituals. Tang came to refer to smaller spaces, including monastic quarters for ascetic practices and sleeping quarters for monks.

This shift suggests that, by the Goryeo period, dian had attained a higher status than that of tang in Buddhist temple architecture, possibly reflecting the growing influence of Chinese monastic traditions on Goryeo Buddhism. However, certain literary works from the Goryeo period do not strictly follow this distinction. For example, prose writings by scholars often use tang and dian interchangeably, referring to both guest rooms and Buddhist halls used to enshrine sacred images (Yi and Yi 1939).

The architectural and functional development of tang and dian reflects a continuous adaptation process across various historical, religious, and cultural contexts. Initially, tang and dian were used interchangeably, though dian was frequently associated with higher status and larger scale. Tang became predominantly linked to ancestral and celestial rituals, while the dian functioned as an official space for rulers. Both terms were applied to ritual spaces in Buddhist temple architecture, with dian used for halls housing sacred images and tang for monastic quarters. By the Goryeo period, dian acquired greater prestige within Buddhist temples, while tang became associated with smaller monastic spaces. These transformations illustrate the adaptability of architectural terminology within East Asia’s religious and secular contexts, highlighting the impact of political, cosmological, and religious ideologies on architectural classifications over time.

3.2.2. Social Stratification and Architectural Terminology in the Later Han Period

During the Zhou period, qin was also used with a similar meaning to tang and dian. These terminological changes in high-ranking buildings are examined in Mingtang Kao 明堂考 of the Daizhen Wenji 戴震文集 and the Kaogong Ji 考工記. As recorded, “During the Xia period, the term shishi (世室, ‘world room’) was used; in the Yin period, zhongwu (重屋, double-eaves house) was applied; and in the Zhou period, mingtang (Luminous Hall) became common” (Dai 2010). Despite differences in nomenclature across historical periods, these three terms essentially referred to the same type of building function. Similarly, the Erya states that “The gong (宮, palace) is called shi (chamber), and the shi is called gong 宮謂之室, 室謂之宮.”

Xu Bo’an, in his analysis of Chinese pictographs related to architecture, identifies a consistent relationship between gong and shi in classical texts, including the Erya, Shiming, and Shuowen Jiezi. He suggests that “gong and shi share a common architectural nature, representing a large building with an expansive roof. The character 至 in shi suggests ‘dwelling inside a tall house with a broad roof’” (B. Xu 1984, p. 75). Both gong and shi were exclusively used for the ruling class and were often mentioned together, reflecting their association with elite residences and governance halls.

However, the Shiming provides a refined distinction: “Gong represents a loft, depicting wu houses elevated above a wall. Shi represents an enclosed chamber, indicating that people are gathered inside the structure” (Li and Liang 1983).

More precisely, this distinction suggests that Gong refers to the scale and grandeur of the building. Shi emphasizes its function as a dwelling space. In the pre-Qin period, gong and shi were used interchangeably to describe various chambers, residences, and royal palaces. However, when gong was used in compound terms, it often denoted a palatial complex rather than a single structure. The Erya further clarifies that “A gate inside a gong is called wei, and a smaller wei is indicated gui. A small gui is called he; the gates in the alleys are called xiangmen 宮中之門, 謂之闈, 其小者, 謂之閨, 小閨, 謂之閤, 衖門” (B. Xu 1984).

By the Later Han period, building types became more socially stratified, leading to further differentiation in terminology. According to the Fengsu Tongyi 風俗通義, “Previously, gong and shi had equal status. However, after the Han period, gong became a term reserved for high-ranking individuals, while lower-ranking persons refrained from using it.”. Similarly, the Baihu Tongyi 白虎通義, compiled by Ban Gu 班固 during the Later Han, records that “The emperor built the gong.” These changes in terminology reflected shifts in political and social structures, with shi, wu, and tang adopting new meanings to align with evolving governance systems. Tang originally referred to taiqi (臺基, platform, or foundation), which emphasizes its role as an elevated structure. The Liji (禮記, Book of Rites) specifies the height of taiqi according to social hierarchy: “The Son of Heaven uses a tang hall nine zhi 雉 high, feudal vassals use a tang seven chi high, state ministers use a tang five chi high, and scholars or warriors use a tang three chi high” (H. Chen 1989). Similarly, the Shangshu Dachuan 尚書大傳 records that “The Son of Heaven uses a tang nine zhi high; the duke and marquis, seven zhi high; and the zinan (子男, baron), five zhi high.” The Mozi 墨子 notes that “During the reigns of Yao and Shun, the height of a tang platform was three chi”(Xujie Liu 2003). These accounts demonstrate a strict hierarchy in tang platforms, which reinforces early Chinese architectural stratification.

The Erya defines the structural differentiation within a tang. Tangxia 堂下 refers to the lower part of the platform, while tangshang 堂上 refers to the upper part of the platform. This implies that tang was fundamentally understood as a foundation upon which halls and residences were constructed. A related term, jie 階, held dual meanings in architectural descriptions: jie referred to the building’s foundation and staircase.

If the platform was multi-leveled, tangshang denoted the upper level, while tangxia referred to the lower level. Another key term, chen 陳, defined the pathway leading to the hall. The Shiming explains that “Chen refers to the path leading to the tang, the place where hosts and guests greet and face one another.” The Shiji (史記, Records of the Grand Historian) further elaborates: “The chen is the pathway to the tang, providing a narrow shortcut from the lower foundation to the entrance.” This suggests that chen was a functional passage connecting different elevations of the tang platform, facilitating processions, ceremonial movements, and hierarchical accessibility.

The historical development of gong, shi, tang, and dian reveals how political, social, and architectural changes shaped their meanings over time. Gong and shi were originally synonymous but became differentiated in the Han period, with gong reserved for elite palatial complexes. Tang was a platform (taiqi) and became a hierarchical architectural feature defined by rank and status. Tang and dian were later used in Buddhist architecture, with dian designated for religious halls and tang for monastic quarters. Jie and chen evolved as related terms, indicating the hierarchical structuring of elevated platforms. The dynamic evolution of these terms illustrates the fluidity of East Asian architectural classifications, emphasizing their symbolic, functional, and hierarchical importance in both imperial and religious contexts.

3.3. Ge Buildings and Evolution in East Asian Architecture

3.3.1. Ge in Classical Texts: Etymology and Architectural Meaning

The Yingzao Fashi does not provide a specific definition of ge. However, numerous references in classical East Asian literature provide insights into its historical use, structural characteristics, and evolving functions, illustrating its role in East Asian architecture. For instance, the Sanfu huangtu 三輔黄圖 says “The ge was built later, rising together with the Nansan Qi” (Q. He 2005, p. 59). It further explains the different functions of ge structures. Siqu-ge 石渠閣 was constructed by Xiao He 蕭何, with its lower grindstones designed to guide water as drainage, defending against flooding (Q. He 2005, p. 329). “The Tianlu-ge 天祿閣 was constructed for the possession of books.” The Miaoji 廟記 speaks of the Qilin-ge 麒麟閣, stating “Qilin-ge, Xiao built it”. The “Yangxiongchuan” 揚雄傳 of the Hanshu 漢書 records that Emperor Xuan commissioned paintings of eleven trusted aides, including Huo Guang, inside Qilin-ge (Q. He 2005, pp. 328–29). The “Tangtumu” 唐杜牧 of the Afanggong fu 阿房宮賦 describes the scale of ge structures, stating that “One lou should be situated every five paces, and ten ge should be situated every ten paces” (Zhongguo shehui kexue yuan 2015). In ancient Korean historical records, the Samguk Sagi states, “King Dongseong ordered the construction of the Overlooking Stream Pavilion 臨流閣, which stood five zhang (approximately 15 m) high. A pond surrounded the structure, housing rare animals for entertainment, and the king observed state affairs from within”. These references illustrate that ge structures served diverse functions, including memorial halls, entertainment pavilions, observatory towers, and book depositories.

The Shuowen jieji states that “The ge is a doorpost (either of the two vertical pieces framing a doorway or supporting the lintel).” The door opens with a long peg or bar on both sides. The Erya explains that “therefore the doorpost is called ge.” In the Yishu, “the ge is referred to as the long timber, which is used as the opening panel of door on the both sides” (Chi and Wang 1997b). According to the Shuowen jieji and Erya, it can be inferred that the ge is made of wood and serves to divide the (protruded) side door. The ge is fundamentally different from elevated constructions used as buildings. However, the original meaning of the ge 閣 can be extended to include the wood components or through the ge 隔 (separation or partition). The Shuowen jiezhi defines “ge (partition) as barriers” (Duan and Xu 1997, 589), and it originated as a vertical or straight post used for dividing spaces in a building, derived from pillars or supports. Thus, the ge construction is similar to early building types following the ganlan method (pile construction 干欄). It is closely linked to plank roads supported by key posts and bridges (a connection made by horizontal beams between two areas), serving as a pile construction for a dwelling or as the lou of the warehouse used for food storage.

Therefore, a proper ge structure requires long posts to support entire buildings, implying a meaning of “ge (separation),” expecting the emergence of the pingzuo framework 平坐. Therefore, the ge is closely associated with the substructure beneath the platform, known as pingzuo, which is an elevated floor system derived from ganlan (pile construction). A wooden building is erected upon the pingzuo, supported by a framed structure. This method later evolved into a combination of piled-up structures, resembling the jinggan method (on the stilted construction). Combining load-bearing longitudinal and transverse frameworks with the column network significantly strengthens timber structures compared to buildings with framed designs. The accumulated structure effectively connects the bracket system to the column network to support a roof frame.

3.3.2. Structural Evolution of Ge: From Partition to Elevated Buildings

In the literature of the Warring States, Qin, and Han periods, the terms “gedao 閣道 (elevated passageway),” “feidao 飛閣 (flying passageway)” (Q. He 2005, p. 25), “qiaoge 橋閣 (bridge),” “ge 閣” (Sima et al. 1982, p. 239), “fudao 复道 (covered way)” (Sima et al. 1982, p. 239), and “niandao 辇道 (passageway for emperor’s carriage)” (Q. He 2005, p. 123) are frequently mentioned, all relevant to the pingzuo frame system (M. Chen 1990, p. 25). Similarly, the architectural form is closely linked to an influence on the partitions “ge” used in the pingzuo frame. The gedao is synonymous with the loudao (passageways of elevated buildings) built above the ground. According to the Qin Section of Discourses of the Warring States 戰國策 秦策, “Zhandao 棧道, a gallery road of 1000 li, passed through Shu-Han (present-day Sichuan) 蜀漢” (J. He 2019). The Shuowen jiezhi defines “wood or bamboo trestlework (zhan) as an elevated passageway across ravines, and a vehicle or a chariot made of bamboo as zhan” (Xu 225). The Qin Section of Discourses of the Warring States mentions “The wooden ge construction as a bridge facing a king and a queen in the Mount Chenyang” (J. He 2019). The Biography of Gaozhu 高祖本紀 in the Shiji’s says, “in the dangerous place, by chiseling mountain cliffs, and then inserting boards and beams into the cliffs, the ge was erected” (Sima et al. 1982, p. 367). The Shuijing zhu 水經注 (Annotated Waterways Classics), compiled by Li Daoyuan 酈道元 (d. 527), during the northern Wei period, provides an account of constructing a gallery road: “The trestlework rested on a beam, with one end embedded in the rock and the other supported by columns rising from the water 其閣梁一頭人山腹, 一頭立柱于於水中.” The zhandao (trestle–gallery road) was a bridge built against the cliff. The only difference between them is that the ends of the beams were inserted into the rock instead of being supported by columns, as in bridges. These records suggest that early ge structures were used for buildings and integrated into elevated passageways, trestle bridges, and fortified paths.

The historical development of ge demonstrates its transformation from a simple wooden partition to a sophisticated architectural feature used in elevated buildings and passageways. Key observations include the following. First, the earliest ge structures served as wooden partitions inside buildings, which were later applied to pile constructions (ganlan method). Second, by the Qin and Han periods, ge evolved into a multifunctional architectural element, including elevated walkways and covered passageways (gedao, fudao), bridges (qiaoge), flying corridors (feige), and cliffside trestle roads (zhandao). Third, ge structures became linked to upscale environments, such as imperial libraries, memorial halls, and entertainment pavilions. Fourth, the ge was instrumental in the shift from single-story wooden buildings to multi-tiered architectural complexes, facilitating the emergence of pagodas, palace towers, and fortified corridors. This progression highlights the versatility of ge structures within East Asian architecture, connecting traditional vernacular styles with imperial and religious influences on structures.

3.3.3. Architectural and Symbolic Evolution of the Ge as an Architectural and Symbolic Structure

Several historical records describe the Jianzhang Palace, constructed under Emperor Wu of the Han dynasty. The palace was situated outside Chang’an and connected to the Weiyang Palace 未央宮 via an elevated passageway called a ge. This ge extended over the walled city, linking the imperial residences across city walls and water bodies. According to the Cihai 辞海, “The cross-passageways between tall buildings have no foundation” (Cihai bianji weiyuanhui 2010). This description suggests that early ge structures were elevated bridges or corridors, enabling movement between imperial buildings while maintaining defensive security and functional accessibility. The Shishi 石氏 commentary further elaborates: “The gedao of the six stars is also a place where the gods mount.” Additionally, the Zhengyi 正義 notes “The gedao of the six stars is north of Wang Liang; and the feige (飛閣, flying corridor) is a secondary road leading to detached palaces, along which the Son of Heaven walks” (Sima et al. 1982, p. 1291). These passages confirm that early ge structures served as symbolic and functional elevated pathways, reflecting cosmological and imperial authority.

Over time, the definition of ge 閣 expanded, evolving from an elevated passageway into a standalone architectural form. References to imperial palatial complexes such as Qilin-ge and Tianlu-ge suggest a shift from connecting corridors to tall, freestanding structures. Unlike early ge, which denoted timber-made doorposts or elevated bridges, these later ge structures were square or rectangular in plan, built independently as towers or pavilions, and used for commemorative, entertainment, and administrative functions. This transition illustrates the gradual formalization of “ge” as an independent structure, which is distinct from its original, corridor-like form function.

The Han dynasty tombs provide further insights into the functional versatility of ge structures. Burial objects and tomb reliefs depict canglou (倉樓, warehouse towers), que (ceremonial towers), and guan (observatory pavilions). These towers were often fortified with earthen walls for defensive purposes. The ge (閣, pavilion) and ge (隔, separation) became conceptually intertwined, signifying both an elevated architectural form (watchtowers, ritual pavilions, and entertainment venues) and a spiritual intermediary (structures symbolizing the connection between heaven and earth).

According to Zhou (2001, p. 190), ge structures were primarily used for entertainment venues, observatories for celestial phenomena, and ritual pavilions for spiritual communion. Similarly, Buddhist ge constructions were designed to seek transcendence and immortality (Penglai-ge, 蓬萊閣), serve as scenic observation platforms (Tengwang-ge, 滕王閣), and host religious ceremonies and performances (Pengge 蓬閣, canopy pavilions with banisters) (Liao 1996, pp. 63–72). The original concept of goulan (鉤欄, carved balustrades) was closely linked to ge, influencing the segmented seating arrangements in Buddhist and theatrical venues. During the Tang and Song dynasties, ge structures became associated with public spaces, marking a shift toward audience-centered architectural forms. The earliest prototypes of ge were based on the ganlan structures, where plank roads and gallery roads were supported by beams inserted into cliffs or pillars in the water.

A significant advancement was the adaptation of pile construction techniques from bridge technology, employing horizontal beams to bridge water bodies and cliffs. As time progressed, these elevated pathways transformed into sturdy, enclosed structures, evolving from trestle bridges to solid pavilions. The ge construction gained symbolic importance by integrating natural landscapes with architectural design (X. Ma 2008). As architectural technology progressed, ge structures became fully integrated into larger complexes, influencing the development of pagodas and multi-tiered design halls.

The ge structure required two primary architectural elements: long vertical posts (隔, separation) supported elevated platforms (pingzuo) and provided structural integrity for multi-level buildings, while horizontal banisters (欄, railings) encircled the elevated structure and ensured safety for occupants. These elements are combined to reinforce the stability and functionality of ge structures, especially in multistory buildings.

By the Song dynasty, ge became synonymous with lou (storied buildings). This resulted in the term “louge”, reflecting a hybridization of architectural functions between lou (multi-story residential and administrative buildings) and ge (elevated pavilions for observation, storage, and ritual use). Furthermore, ge structures absorbed elements of other tall buildings, including xie (open pavilions built on platforms) and tai (terraces and altars used for rituals and celestial observation). This gradual transformation of ge culminated in its architectural influence on Buddhist pagodas. Pagodas inherited the structural innovations of ge, lou, tai, and xie and the symbolic function of ge as a bridge between the terrestrial and celestial realms.

The ge underwent a continuous transformation from simple wooden partitions into symbolic and functional multi-tiered structures that influenced East Asian monumental architecture. Early ge structures functioned as elevated passageways, connecting imperial palaces across city walls and water bodies. Over time, the meaning of ge expanded, and the form evolved into freestanding buildings for administrative, ceremonial, and entertainment purposes. The Han dynasty tomb architecture reveals ge’s dual role as a practical structure and symbolic monument. The ganlan method influenced ge constructions, incorporating pile-based frameworks into bridges, passageways, and elevated buildings. Structural innovations in ge contributed to the development of pagodas by integrating multitiered constructions, symbolic cosmology, and ritual functions. Ultimately, ge represents one of the most significant architectural evolutions in East Asian history, which bridges vernacular pile constructions with monumental forms of Buddhist and imperial architecture.

3.4. The Evolution of Lou as Ritual and Architectural Contexts

3.4.1. The Lou’s Evolution: From Celestial Towers to Secular Architecture

The earliest references to lou appear in the context of mingtang, a sacred structure used for imperial rites and celestial worship. According to the Hanzhi 漢志, “Jiaosi Zhixia” 郊祀志下, “Earlier, the Son of Heaven (Emperor Wu of Han) conducted the feng ritual at Mount Tai. The northeastern part of Mount Tai, at its foot, was the site of the mingtang, which was located in a perilous and constricted area. The emperor desired a mingtang at Fenggao 奉高 but was uncertain about its specifications.” A scholar from Jinan 濟南, Yugong Dai 玉公帶, described the mingtang layout from the Huangdi (Yellow Emperor) period: there was a central palatial hall with four sides open and a thatched roof; a circular water channel enclosed the palace precinct; elevated covered passageways led to a lou, entered from the southwest, called “Kunlun” 昆侖; and the Son of Heaven performed celestial sacrifices through this entrance.

In 109 BCE, Emperor Wu of Han ordered the construction of a mingtang along the Wen River at Fenggao based on Yugong Dai’s specifications (Ran et al. 1962). This was the first detailed record of the architectural form of mingtang. However, the mingtang at Mount Tai functioned differently from those in dynastic capitals, as it emphasized Daoist cosmology and celestial worship. A key feature of this mingtang was its lou structure, which is associated with “Kunlun.” It remains uncertain whether “Kunlun” in this context directly refers to Mount Kunlun, the legendary home of Daoist transcendents. If so, this lou symbolized a celestial gateway, reinforcing the Daoist connection between architecture and the divine realm.

The “Jiaosi Zhixia” further records that “Transcendents instructed the emperor to construct five fortresses and twelve tall buildings (lou) as sacred loci for hermits on Mount Kunlun. They also advised him to await the immortals and welcome the new year.” This suggests that lou structures were ritualistically significant, symbolizing cosmic harmony. Their elevated form symbolized celestial ascent, reinforcing their role as stairways to heaven and their integral part in imperial rites and Daoist cosmology, contributing to sacred imperial landscapes. Whether the emperor physically lived in a lou or constructed them as ceremonial monuments, these tall structures were conceptually connected to the celestial worship (Ran et al. 1962, p. 1246).

In the Huainanzi 淮南子, “Benjingxun” describes lou as “A structure extending upwards to form a high-rise building. A plank roadway, a flying tall building, and a covered passageway interconnect different spaces. The structure follows the well-formed jinggan method” (N. He 1998, p. 589). This implies that lou structures were vertically extended buildings designed for both observation and ceremonial use, that they incorporated plank roads and flying corridors (feilou 飛樓), resembling trestlework bridges, and that their construction followed the well-structured jinggan method, ensuring stability and adaptability for multi-story applications. The Erya defines lou as “A tall terraced platform with narrow, curved walls” (Li and Liang 1983, p. 28). The Yingzao Fashi in juan five states “A high-rise tower on the northwest side, rising together with the clouds, with triple stairways and intricately designed windows” (M. Ma 1981, p. 62). The Shiming elaborates: “A lou is a tower with loopholes between widely spaced open windows” (Liu, n.d.). Additionally, the description of the lou in the Mozi aligns with those found in the Erya and the Shiming. The Shuowen Jiezi defines the lou as a multi-story building. By the Han period, lou structures had transitioned from ritual architecture to practical multi-story buildings used for imperial residences and governmental halls, military watchtowers with defensive loopholes, and Buddhist monastic structures and pagoda adaptations.

The lou emerged as a pivotal architectural typology, evolving through its early role in celestial worship and Daoist immortality, its function as an imperial observatory and sacred structure, its technological development into a practical multi-story building, and its influence on Buddhist pagodas and monastic halls. This transformation illustrates how ritual architecture adapted to secular and monumental functions, influencing the evolution of East Asian wooden architecture, from imperial palaces to temple pagodas and residential pavilions.

3.4.2. The Evolution of Lou from Imperial Architecture to Buddhist Monastic Spaces

The louju (樓居, tower dwelling) concept extended to residential pavilions for the elite, aesthetic structures, entertainment, and theatrical venues. The Yingzao Fashi documents the lou’s technological advancements, including braced wooden frameworks for vertical stability, Jinggan techniques for seismic resistance, and elevated passageways interconnecting multi-tiered structures. According to the Shiji, Emperor Wu of Han commissioned the sia construction in 115 BCE, naming it the Bailiangtai Terrace (柏樑臺, High Terrace with Arborvitae Beams). This monumental platform was erected following the counsel of two ascetics, Shao Wen 少翁 and Gongsun Qing 公孫卿, who advised “Transcendents prefer a louju.” Despite being described as a lou, Bailiang-tai was, in reality, a multi-storied terrace (tai) constructed using a rammed-earth foundation, akin to Warring States-period terraces, and a celestial dew collector 露盤 at its summit, symbolizing divine connection. Gongsun Qing later explained: “Daoist immortals remain active in the heavens, though we cannot perceive them. Today, emperors can observe them by offering dried meats and jujubes in Goushi Cheng. The immortals should approve these rituals, as they favor a louju.”

This highlights the lou’s celestial function as an observatory for divine beings, its symbolic association with transcendence and Daoist immortality, and its integration into Han dynasty state rituals, which blended political power with religious ideology. However, Bailiang-tai was destroyed by fire in 104 BCE. Subsequently, Emperor Wu constructed new structures, including Shenming-tai Terrace 神明臺 and Jinggan-lou Pavilion 井干樓. Each fifty zhang high (approximately 115 m), these towering edifices were interconnected by a two-story elevated passageway (Pyŏn et al. 2021, p. 478; Forte 1988, p. 131).

The Tang emperor Taizong later reflected on the role of these elevated structures in Daoist imperial rituals, stating “The loudao (an elevated way linking palatial buildings) raises the lou. The dao (passageway) is a convenient yet narrow path. For the emperor to ride a chariot along this path to meet the gods is improper. Climbing stairways is also an arduous task for one who seeks the sacred” (Cen et al. 1995, p. 850). This passage suggests that structures like the Jinggan-lou and Shenming-tai were monumental symbols of imperial power and architectural manifestations of Emperor Wu’s Daoist aspirations for immortality. Moreover, they represent some of the earliest documented timber-building technologies, influencing subsequent wooden construction in Chinese, Korean, and Japanese architecture.

Over time, lou structures were increasingly incorporated into Buddhist temple complexes. The Samguk Yusa states “On the first day of the fourth month of the nineteenth year of King Gyeongdeok, an altar was erected at the Jowon-jeon (Royal Wish Hall). The king ascended the Cheongyang-ru (Highrise Pavilion) to await the arrival of a monk. Just then, Master Wolmyeong walked southward along the levee path”. Additionally, the text records that “Sakra descended toward the Sutra Tower of Hongnyunsa Buddhist Monastery, located on the left side, and remained there for ten days.” These accounts suggest that lou constructions were integral to Buddhist temple complexes, functioning as observation towers or pavilions (similar to Daoist celestial towers); architectural elements within temple precincts, positioned alongside pagodas and image halls; and symbolic structures used in rituals invoking divine presence.

The Mozi offers further insights into the lou’s architectural function, particularly in fortifications. In the “Beixue” 備穴 chapter, lou structures are described as follows: “Along the walls, one lou should be built every hundred bu (步, paces) at regular intervals. Each lou should be supported by four straight pillars, with the bottom connected by a timber foundation. The first floor should be ten chi high and the second floor nine chi high. Each lou should take the form of a ting (pavilion).” Additionally, the “Haoling” 號令 chapter states that “Official gatekeepers guard the city gates. Atop these gates, tall lou should face each other, and the best archers should be stationed there.” The “Beiechuan” 備蛾傳 chapter elaborates: “At each corner, a lou should be constructed as a double-eaved building.” (Cen 1958, pp. 55, 81, 98; Mo and Mao 2002). These descriptions highlight two primary functions of the lou in early China. First, fortifications served as defensive watchtowers and military observation points during the Warring States period. Second is architectural evolution: the lou gradually incorporated the double-eave structure, evolving into multi-story residential dwellings, temple halls, monastic towers, and administrative and imperial palatial buildings.

3.4.3. The Integration of Lou, Tai, Ge, and Xie into Architectural Legacy

The distinctions between lou (multi-story towers), tai (terraced platforms), ge (pavilions), and xie (open terraced structures) began to blur over time, especially in Buddhist temple design. For instance, lou structures were incorporated into monastic spaces, influencing the development of sutra towers and library pavilions. Tai platforms served as the foundation for temple complexes and pagodas. Ge pavilions evolved into elevated halls for sacred texts and relics. Xie terraces were used for open-air Buddhist ceremonies and meditation spaces. These architectural forms, derived initially from imperial and Daoist structures, were adapted into Buddhist monastic settings, reinforcing the religious, ritualistic, and cosmological symbolism of East Asian temple architecture.