1. Introduction

A central focus of my research is the conceptual world of Mount Sumeru [須弥山], which I explore as a foundation of the universal cosmological framework in Asia. Mount Sumeru as the cosmic centre is a sacred mountain first imagined by Brahmin priests in ancient India, prior to the emergence of Buddhism. Buddhism later adopted this worldview, incorporating Śakra [帝釈天], who resides at the summit of Mount Sumeru, as one of its guardian deities. As Buddhism spread from India to China and the scriptures were translated into Chinese, this cosmology was transmitted throughout the Sinosphere—regions such as Korea, Japan and Vietnam that shared Chinese characters and cultural influences. Thus, Mount Sumeru came to represent the central axis of the Buddhist worldview widely shared across Asia.

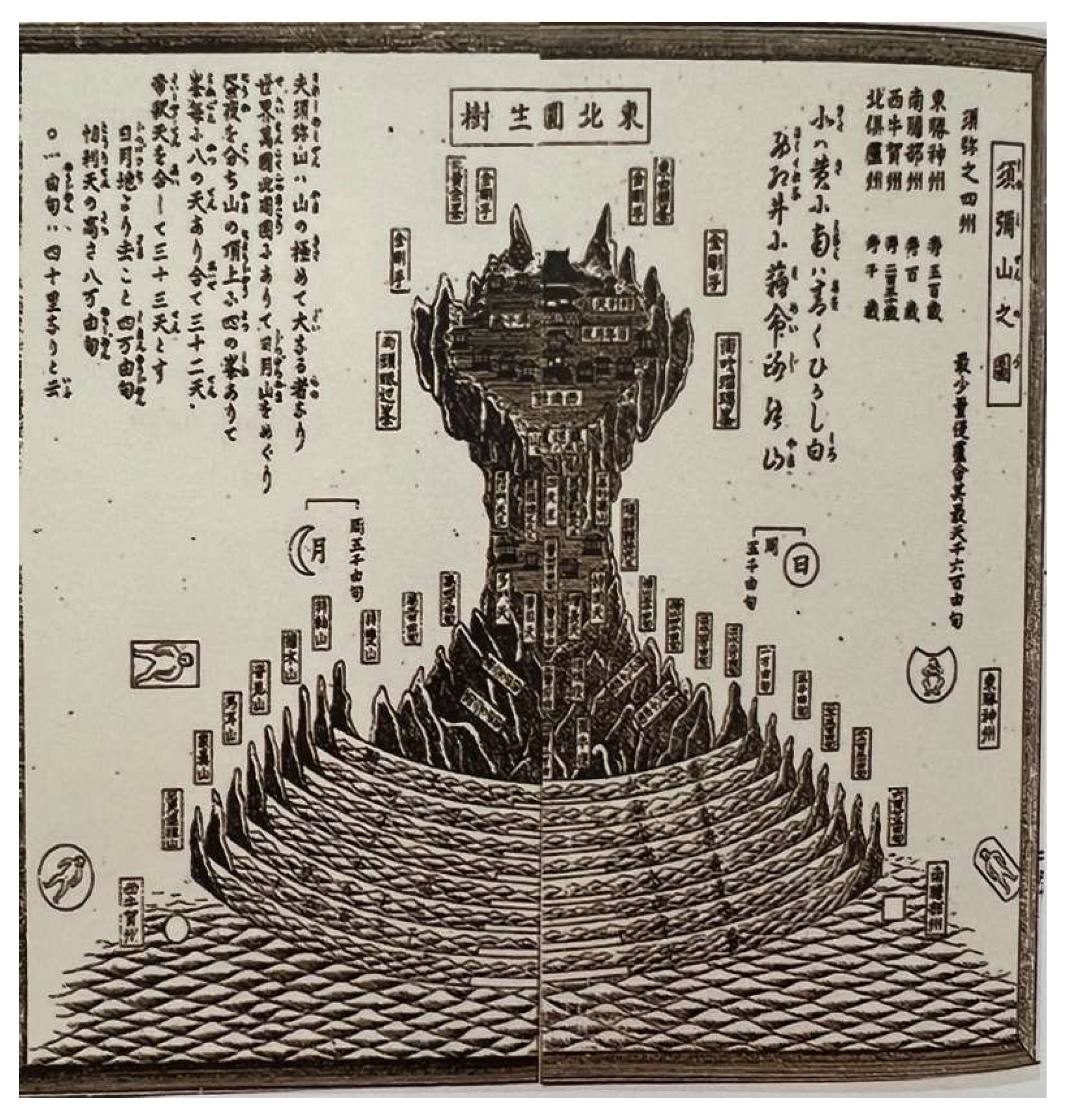

Mount Sumeru is said to appear in an inverted triangular shape and be located at the centre of the world, surrounded by nine mountains and eight seas, with the sun and moon on either side. There is a continent on each of its four sides, and humans live on Jambudvīpa [南瞻部洲] in south. Below Mount Sumeru is Hell, and above it is Heaven. Each location on Mount Sumeru has its own inhabitants. Depending on the quality of one’s austerities, one may ascend to the Heavenly Realms or descend to Hell. At the summit of Mount Sumeru is the Trāyastriṃśa Heaven [忉利天] where Śakra resides. Above that, there is the Realm of Desire [欲界], the Realm of Form [色界] and the Realm of Formlessness [無色界] in the Trailokya. All being illuminated by the same sun and moon, the entire structure of the world of Mount Sumeru consists of the realms from Hell below to the Trailokya in the Heavenly Realms above. The length of time differs according to the spatial differences.

This study focuses on extant paper-based materials from Japan and China within the Sinosphere. The oldest known example of one of these artefacts is

Three Realms and Nine Lands [三界九地之図; Sān jiè jiǔ de zhī tú], a 9th- to 10th-century Chinese handscroll painting discovered in Dūn Huáng. Another key work is

Buddhist Cosmology (1402) [日本須弥諸天図; Nihon shumi shoten zu], preserved in the Harvard Art Museums and first extensively discussed by Komine Kazuaki. Finally, I will analyse the depictions of Mount Sumeru in the

Establishment of the Dharma-Field with Illustrations (1548) [法界安立図; Fǎ jiè ān lì tú], a Ming-dynasty Buddhist text.

1In the Dūn Huáng and Harvard versions of the Mount Sumeru paintings, one element that has consistently drawn my attention is the Enshōju [円生樹 or 圓生樹], the great Pārijāta Tree

2, situated in the Trāyastriṃśa Heaven at the summit of Mount Sumeru. This paper examines the Pārijāta Tree’s role in Buddhist cosmology and its intertextual symbolism across key texts and visual representations.

2. The Pārijāta Tree in Chinese Translations of Buddhist Texts

The Pārijāta Tree holds a prominent position in Buddhist cosmology, often likened to Mount Sumeru in its symbolic importance. According to the fourth volume of

Saṃyukta Āgama [雑阿含経]

3, the Pārijāta Tree is regarded as the foremost among all trees, just as Mount Sumeru is considered the paramount among mountains. This significance is emphasised in the preface of the first volume of the

Lotus Sūtra [法華経]

4, which describes the Pārijāta Tree as follows:

- “…is as outstandingly wonderful and lovely

- as the heavenly king of trees

- when its flowers open and unfold.

- When the Buddha emits a beam of light…”5

The “heavenly king of trees [天樹王]” here refers to the Pārijāta Tree in the Trāyastriṃśa Heaven, one of the important realms in Buddhist cosmology, as noted in an annotated edition of the Lotus Sūtra. According to the

Treasury of Abhidharma [(阿毘達磨)倶舎論]

6, the Pārijāta Tree is distinguished not only by its immense size but also by the fragrance of its flowers. The Pārijāta Tree is located in the northeast of Nandanavana [歓喜園] in the Trāyastriṃśa Heaven, often juxtaposed with the Hall of Fine Dharma [善法堂] in the southwest. Furthermore, the Pārijāta Tree is the place where one receives the pleasures of the Trāyastriṃśa Heaven. Its roots extend fifty yojanas deep, while its branches rise over one hundred yojanas high. When the Pārijāta flowers bloom, their fragrance permeates a radius of fifty yojanas, extending up to one hundred yojanas.

The Pārijāta Tree is not only a cosmological marker but also a site of profound narrative and symbolic significance. One of the most notable stories involving the Pārijāta Tree recounts Śākyamuni’s journey to the Trāyastriṃśa Heaven to enlighten his mother, Queen Māyā. In this story, Śākyamuni stood beneath the Pārijāta Tree, where streams of milk from Māyā’s breasts flowed into his mouth, symbolising the proof of their mother–son relationship. Since Māyā had passed away seven days after giving birth to Śākyamuni and was reincarnated in the Trāyastriṃśa Heaven, she was unaware of Śākyamuni’s later life. Thus, this act of maternal recognition served not only as proof of their relationship but also as a means for Śākyamuni to express his gratitude and guide his mother toward liberation from the cycle of birth and death and reach the state of Nirvana. The story can be found in the

Sūtra of Mahamaya [摩訶摩耶經]

7 and

Shakya Genealogy [釋迦譜]

8. It also appears in the second story in the third volume of the

Anthology of Tales Old and New [今昔物語集] in a Japanese context, written during the late Heian period.

The motif of “beneath the tree” carries intertextual significance across Buddhist literature. For instance, in the nineth volume of the

Century of Noble Deeds [撰集百縁經]

9, Śākyamuni preaches a sermon beneath the Pārijāta Tree for the sake of his mother. This motif echoes earlier narratives of Queen Māyā raising her right hand to touch the branch beneath the Ashoka Tree and Śākyamuni being born from her side. The act of Śākyamuni receiving Māyā’s milk beneath the Pārijāta Tree may carry intertextual significance related to the recurring motif of “beneath the tree.”

Divergent Concepts in the Sūtras and Vinaya Texts [経律異相]

10, a Chinese Buddhist text compiling essential passages from the Sūtras, vinaya and treatises based on the

Nirvana Sūtra [涅槃経], recounts the story of King Murdhagata, who flew through the Heaven Realm and arrived at the Trāyastriṃśa Heaven. Upon spotting a tree with a blue-green colour, he inquired about it and was told by a secretary that it was the Pārijāta Tree, a gathering place for the heavenly beings during the summer. Next, he noticed something white resembling a cloud and learned that it was the Hall of Fine Dharma, where the heavenly beings discussed matters concerning humans and gods. This Hall of Fine Dharma is also where Śakra greeted King Murdhagata. Notably, the Pārijāta Tree is the first thing that captured King Murdhagata’s attention when he looked down upon the Trāyastriṃśa Heaven, and this aligns precisely with the depictions in the Dūn Huáng and Harvard handscrolls mentioned earlier. Thus, the Pārijāta Tree and the Hall of Fine Dharma emerge as two central parts of the Trāyastriṃśa Heaven, each holding distinct symbolic and functional significance.

The Pārijāta Tree is frequently referred to as the “king among the heavenly trees”. For example, in Volume 38 of the

Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra [大般涅槃經]

11, the luminous mind—a state surpassing the joy derived from practicing the Six Perfections [pāramitā]—is metaphorically likened to the Pārijāta Tree in the Trāyastriṃśa Heaven. Similarly, the first volume of the

Ākāśagarbha Bodhisattva Sūtra [虚空孕菩薩經]

12 states that when a pious individual progresses on the path to Buddhahood, the Chintamani Stone, a wish-fulfilling jewel, will emerge in response to him; for one who practices the Śūraṃgama-samādhi [首楞嚴三昧], he manifests qualities like those of the Pārijāta Tree. In Volume 22 of the

Abhidharma Mahāvibhāṣā Śāstra [阿毘曇毘婆沙論]

13, the Pārijāta Tree serves as a metaphor for the Arahants, individuals who have attained Nirvana. Furthermore, in the preface to the

Daśacakra Kṣitigarbha Sūtra [大乗大集地蔵十輪経]

14, it is said that the pious individual will gather various precious treasures while practicing the Buddhist austerities, like the flowers that naturally decorate the Pārijāta Tree.

In Volume 36 of the

Flower Adornment Sūtra [

Mahāvaipulya Buddhāvataṃsaka Sūtra, 大方廣佛華嚴經]

15, it states, “though not yet in bloom, the Pārijāta Tree and the Kovidāra Tree are known to be the origin of countless flowers, like the bodhicitta of the Bodhisattva Mahāsattva [菩薩摩訶薩].” The seeds of the Pārijāta Tree are compared to the pious man’s bodhicitta, namely, his enlightenment-mind, suggesting that even before they bloom, the seeds carry the potential for infinite blossoms in the near future. Similarly, in the second volume of the

Saptaśatikā-prajñāpāramitā Sūtra [文殊師利所説摩訶般若波羅蜜經]

16, the Buddha tells Kāśyapa [迦葉(shè)] that the heavenly beings are delighted to see the buds of the Pārijāta Tree appear for the first time in the Trāyastriṃśa Heaven, as the buds signal the tree’s impending bloom. This great delight mirrors the belief and understanding that arise upon reaching the enlightenment through the Perfection of Wisdom, as described in Volume 116 of the

Mahāratnakūṭa Sūtra [大寶積經].

As discussed earlier, the Pārijāta Tree holds significance in terms of symbolising the bond between mothers and children. Beyond this, it is widely recognised in the Buddhist context as a metaphor for the state of enlightenment or Buddhist austerities. Consequently, the Pārijāta Tree often serves as a symbol of spiritual attainment in Buddhist culture. Much like Mount Sumeru, which is metaphorically associated with its immensity and tenacity, the Pārijāta Tree is imbued with symbolic meaning through its blossoms in prosperity. Its seeds, which grow into majestic trees, parallel the spiritual journey of an arahant—a pious practitioner whose pure mind and heart ultimately lead to the awakening of bodhicitta and the attainment of enlightenment.

3. The Image of Mount Sumeru in the Harvard and Dūn Huáng Versions of Handscroll Paintings

As introduced earlier, the Buddhist Cosmology preserved in the Harvard Art Museums is a mediaeval Japanese handscroll depicting the three realms of Japan, India and Heaven centred around Mount Sumeru. An additional picture is included in the section depicting India, illustrating Anavatapta [無熱池], the source of the world’s water. The illustration of Mount Sumeru features not only an image of the mountain rising from a round ocean, but also a concentric circle of the “nine mountains and eight oceans” as viewed from above the three realms, with a square at the centre representing Mount Sumeru. The four cardinal directions are marked by illustrations of human races, while the margins are filled with detailed annotations excerpted from Chinese translations of Buddhist texts.

As introduced by Komine, this scroll was created in June 1402 by the monk Ryū-i [隆意] of Daigo-ji Temple in Kyoto, with a signature of Ryū-yū [隆宥], believed to be his student. This work is exceptionally valuable as it can be precisely dated and attributed to its creators, making it a key reference for studying depictions of Mount Sumeru.

In contrast, the Dūn Huáng version, as the oldest existing form of a handscroll, depicts the summit of Mount Sumeru as a circular structure resembling a nine-story pagoda at the centre. The Hall of Fine Dharma and the Pārijāta Tree are positioned on opposite sides of the circle, corresponding to the description in the

Treasury of Abhidharma17, “the Pārijāta Tree in the northeast, the Hall of Fine Dharma in the southwest,” indicating that they serve as landmarks for the Trāyastriṃśa Heaven.

In the Dūn Huáng version, the Hall of Fine Dharma and the Pārijāta Tree are depicted as opposites, positioned behind the Trāyastriṃśa Heaven. In

Figure 1, the Harvard version, however, the Pārijāta Tree is prominently placed on the right within the Trāyastriṃśa Heaven, while the Hall of Fine Dharma is absent from the illustration. Instead, its location is noted in the annotations: “the Hall of Fine Dharma in the southwest, the Pārijāta Tree in the northeast, four gardens at the four corners.” A marginal note on the left side of the Harvard version further identifies the Hall of Fine Dharma as the Wonderful Law Hall [妙法堂] mentioned in the

Lotus Sūtra:

法華経云、釈提桓因在勝殿、若在妙法堂、為忉利天諸天、説法教化衆生之類云々。解釈提桓因、帝釈也。妙法堂者善法堂也。

It is said in the Lotus Sūtra, “Śakra is in his superb palace, or in the Hall of the Wonderful Law to preach the Law for the heavenly beings of Trāyastriṃśa Heaven.” Śakra, therefore, refers to Śakra, and the Hall of the Wonderful Law corresponds to the Hall of Fine Dharma.

Regarding the Pārijāta Tree, the following note is found in the margin above its image:

此円生樹者、高広百由旬、妙香芳馥、順風薫百由旬、逆風尚過五十由旬。

18

The Pārijāta Tree extends to a height over a hundred yojanas. Its delightful fragrance reaches distances of a hundred yojanas with the wind and extends over fifty yojanas even against the wind.

This description aligns with the Treasury of Abhidharma, which states, “Its height and width each measure 100 yojanas. Its leaves and flowers emit a delightful fragrance. With a favourable wind, the scent can reach 100 yojanas. Even against the wind, it still spreads over 50 yojanas.” A yojana, an ancient Indian unit of length, is estimated to correspond to seven to eight kilometres. Given that Mount Sumeru is described as 80,000 yojanas in height, the image of the Pārijāta Tree should be extraordinarily immense.

In the Harvard version, the Pārijāta Tree is depicted as a deciduous tree with branches extending to the right and left, adorned with leaves from the left to right branch. Other branches extend from its central upper body, the lower left and the mid-right part, each covered with leaves, more than half of which are red. This aesthetic image of the deciduous tree is consistent with the image of the Loquat Tree [yakuōju] beneath the Anavatapta in the section of India within the Harvard version. Although the Loquat Tree has fewer branches, it similarly features red leaves.

Figure 1.

The Pārijāta Tree in the “Harvard version”—Buddhist Cosmology, preserved in Harvard Art Museums. At the top of the figure, the text above the tree reads: 此円生樹者、高広百由旬、妙香芳馥、順風薫百由旬、逆風尚過五十由旬. On the left margin of the lower part, the text states: 法華経云、釈提桓因在勝殿、若在妙法堂、為忉利天諸天、説法教化衆生之類云々。解釈提桓因、帝釈也。妙法堂者善法堂也.

Figure 1.

The Pārijāta Tree in the “Harvard version”—Buddhist Cosmology, preserved in Harvard Art Museums. At the top of the figure, the text above the tree reads: 此円生樹者、高広百由旬、妙香芳馥、順風薫百由旬、逆風尚過五十由旬. On the left margin of the lower part, the text states: 法華経云、釈提桓因在勝殿、若在妙法堂、為忉利天諸天、説法教化衆生之類云々。解釈提桓因、帝釈也。妙法堂者善法堂也.

The Pārijāta Tree also appears in an Edo-period woodcut of Mount Sumeru. However, the woodcut is monochrome, meaning we lack information about its colours. In this regard, the coloured painting of the Harvard version is particularly valuable for understanding the Pārijāta Tree’s symbolic and aesthetic representation.

Another noteworthy text is the

Establishment of the Dharma-Field with Illustrations [法界安立図], see

Figure 2. It is an illustrated text interpreting Buddhist cosmology created during the Ming dynasty in 1584. Its illustration,

Palace of Trāyastriṃśa Heaven [忉利天宮之図], depicts the summit of Mount Sumeru as a circular structure viewed from above, encircled by two concentric layers of wall. The Supreme Palace [帝釈殊勝殿], namely, Śakra’s dwelling, lies in the very centre of the circle. The great tree situated to the northeast, outside the walls, is presumed to be the Pārijāta Tree, since the palace next to it is Pārijāta Tree Heaven [波利樹天].

4. The Pārijāta Tree in Japanese Classics and Later Literature

This section examines the representations of the Pārijāta Tree in selected Japanese Classics. First, the late 12th-century anthology Songs to Make the Dust Dance on the Beams [梁塵秘抄] includes the following lyrics:

忉利は尊き所なり、善法堂には未申、円生樹より丑寅に、中には喜見の城立てり

19Trāyastriṃśa is a sacred place. The Hall of Fine Dharma is in the southwest. The Pārijāta Tree lies is in the northeast. Śakra’s dwelling, Castle of Blissful Vision [kikenjō], stands at the centre.

These lyrics reflect how the Trāyastriṃśa Heaven, situated at the summit of Mount Sumeru, was perceived as a cosmological landmark. The songs, performed among the aristocracy of the Heian period, illustrate the influence of Buddhist cosmology on their life.

In the ending plot of Soga Monogatari [曽我物語; The Tale of Soga], a 14th-century text written entirely in kanji, Tora Gozen, the concubine of Soga Sukenari, becomes a nun and enshrines the remains of the Soga brothers at the Zenkōji Temple in Shinano Province. After returning to the Soga family, she influences the brothers’ parents, her own mother and several prostitutes to embrace Buddhism as well. Those connected to the Soga family gather at the Soga’s enshrinement hall to receive Buddhist preachment from Tora. Tora begins her preachment by claiming that one’s short life is merely their temporary stay, then emphasises that women should place their hope in Amitabha and aspire to rebirth in the Pure Land where the music far surpasses that of the heavenly beings. To underscore the superiority of the Pure Land, she enumerates several mythical trees:

釈天東北の円生樹 (shaku ten tō hoku no en shō ju), 歓喜苑の波利質多羅樹 (kan ki en no ha ri shi tta ra ju), 中陽院の天正樹 (chū yō in no ten shō ju), 四王天の朴刀樹 (shi ten non no boku tō ju), 迦毘羅城の無憂樹 (ka pi ra jo no mu u ju), 摩黎山の栴檀樹 (ma ri sen no sen dan ju), 涼水山の金正樹 (ryō sui zan no kin masa ki), 閻浮無双の瞻部樹 (en bu mu sō no sen bu ju), 転正山の好堅樹 (ten shō zan no kō ken ju), 奢提山の尼倶陀樹 (sha tei zan no ni ku da ju), 沙羅菓の音楽樹 (sa ra ka no on gaku ju), 菩提山の普沙羅樹 (bo dai sen no fu sa ra ju).

20

The Pārijāta Tree is notably listed first. However, Tora asserts that even if all these mythical trees were combined, they would pale in comparison to the golden forests of the Pure Land. She further emphasises that the ponds, palaces, pavilions and birds of the Pure Land are likewise unparalleled. Similar descriptions of the Pure Land’s superiority can be found in The Essentials of Rebirth in the Pure Land [往生要集].

It is noteworthy that the first tree mentioned is the Enshōju in the northeast of the Trāyastriṃśa Heaven, followed by the “歓喜苑の波利質多羅樹 (kan ki en no ha ri shi tta ra ju) [Harishittaraju in the Nandanavana]”. While Enshōju and Harishittaraju both refer to the Pārijāta Tree, their separate listing suggests that the distinction between the two names may have been forgotten over times.

After “迦毘羅城の無憂樹 (ka pi ra jo no mu u ju) [Ashoka Tree in Kapilavastu]”, the enumeration shifts to trees of the terrestrial realm. Only the Ashoka Tree associated with Śākyamuni’s birth is mentioned, and the Bodhi Tree of awakening or enlightenment is also absent. More, it remains unclear whether the 菩提山の普沙羅樹 (bo dai sen no fu sa ra ju) is identical to the 涅槃の沙羅双樹 (ne han no sa ra so ju) [Sal Tree of Nirvana].

It is noted in annotations of the Heibonsha Tōyō Bunko edition that a similar enumeration can be found in The Collection of Tamemori’s Resolve for Buddhism [為盛発心因縁集; tamemori hosshin innenshū]. But the enumeration continues with “Ashoka Tree, Chinaberry Tree, Jambu Tree, Nygrodha Tree, Sal Tree, and Music Tree” after the two names of the Pārijāta Tree, making the account in The Tale of Soga comparatively more detailed. A similar motif of listing mythical trees is also found in the story of Suwa no honji [諏訪の本地; The True Form of Suwa] in Shindōshū [神道集; Collection of Shrine Legends], suggesting that listing mythical trees in both the celestial and terrestrial realms is a recurring motif.

As suggested by Komine, Volume 22 of Tōdengyōhitsu [榻鴫暁筆; Written at Dawn when the Snipes Rise], a 16th-century narrative anthology, begins with references to the flying plum trees [飛梅 (tobi ume)] of Japan and the birchleaf pear trees [甘棠 (gān táng)] of China, before continuing with trees from India and Buddhist culture:

胡椒樹 (Hú jiāo shù), 宝多羅樹 (bǎo duō luó shù), 迦羅伽樹 (jiā luó jiā shù), 菴羅樹 (ān luó shù), 阿摩落伽 (ā mó luò jiā), 瞻部林樹 (zhān bù lín shù), 多羅樹 (duō luó shù), 大薬王樹 (dà yào wáng shù), 尼拘律樹 (ní jū lǜ shù),

好堅樹 (hǎo jiān shù), 菩提樹 (pú tí shù),

楽音樹 (yuè yīn shù), 羯尼迦樹 (jié ní jiā shù), 楊枝樹 (yáng zhī shù), 善求悪求樹 (shàn qiú è qiú shù), 優曇華 (yōu tán huá), 阿梨樹 (ā lí shù),

波利質多羅樹 (bō lì zhì duō luó shù),

天生樹 (tiān shēng shù), 衣領樹 (yī lǐng shù), 剣葉林 (jiàn yè lín).

21

The trees highlighted in bold overlap with those mentioned in The Tale of Soga. While some, such as the 菩提樹 [pú tí shù; Bodhi Tree] and 優曇華 [yōu tán huá; Cluster Fig], are well-known, the diversity of tree names is striking. Many of these names are based on sources like the Records of the Western Regions [大唐西域記] and A Forest of Pearls from the Dharma Garden.

The Pārijāta Tree aligns with descriptions found in the previously mentioned Chinese translations of Buddhist texts. When its leaves fall and flowers bloom, a delightful fragrance spreads with the wind and light from the tree illuminates up to fifty yojanas. As the leaves turn yellow, the fragrance intensifies and its light extends to eighty yojanas. The heavenly beings enjoy and appreciate this transformation in summer. The Buddha also uses it as a metaphor to teach his disciples, illustrating their journey from leaving home to attaining enlightenment.

Next, images of the Pārijāta Tree in other paintings of Mount Sumeru will be traced and examined. Two key references provide a wealth of visual material:

Ajia no kosumosu + Mandara [アジアのコスモス+マンダラ; Asian Cosmos + Mandala] (

Sugiura 1982), edited by Sugiura Kōhei and Iwata Keiji, and

The Japanese Buddhist World Map (

Moerman 2021) by D. Max Moerman. These works both feature a wealth of pictures and enable the identification of the Pārijāta Tree depicted in Mount Sumeru paintings in the following four examples:

① Sankai goshu zu [三界五趣図; Trailokya and Five Paths], in the late 17th century.

② Page 225 of Tenmonzukai [天文図解; Explanation of Astronomy by Figures], by Iguchi Tsunenori, 1688. Preserved by Waseda University Library.

③ Page 297 of Shin sen hou ryaku ō za ssho [新撰宝暦大雑書; New Miscellaneous Book of the Hōryaku Period], 1686. Preserved by the National Diet Library.

④ Page 298 of Unkikongen fukurokuju manpō dai zassho taizen [運気根元福禄寿万宝大雑書大全; The Root of Luck: A Miscellaneous Encyclopedia of Treasures of Happiness, Wealth, and Longevity], 1899. Preserved by National Diet Library.

A notable feature of later depictions is the overall shape of Mount Sumeru. In later periods, the mountain is depicted as an inverted triangle rising from the bottom, differing from earlier representations in the Dūn Huáng and Harvard versions, where the mountain stands upright on the bottom and appears like an inverted triangle only on the top; it narrows once at the hillside around the Cāturmahārājakāyika Heaven [四天王天] and expands again. The oldest known example of this shape is found in the

Establishment of the Dharma-Field with Illustrations, published in the late 16th century during China’s Ming dynasty. The exact time during which this shape emerged remains uncertain. Yet, the paintings of Mount Sumeru in Japan during the Edo period generally follow a similar pattern seen in the

Establishment of the Dharma-Field with Illustrations. However, not all depictions conform to this pattern. For instance, Mount Sumeru remains upright in a traditional shape in

Trailokya and Five Paths, see

Figure 3.

The Pārijāta Tree in

Figure 3 is depicted with a structure opposite to that in the Harvard version, as it branches to the left at first and then to the right at a higher point. The tree is shown in full bloom. On the right side of the tree, there is a prominent headword “Tōhoku enshōju” [東北圓生樹; the Pārijāta Tree in the Northeast] in a frame. Next to that, a passage from the

Treasury of Abhidharma is quoted, describing the Tree’s size and fragrance, similar to the annotations found in the Harvard version.

In

Figure 4,

Explanation of Astronomy by Figures, Mount Sumeru narrows at the hillside, with its summit depicted as a rounded square. The Pārijāta Tree is positioned at the centre of this square, beneath a horizontal headword “Tōhoku enshōju.” The tree’s branching pattern closely resembles that in

Figure 3. Palaces are sketched along the outer edge of the rounded square, with a relatively large, two-storey building at the front centre, identified as the Hall of Fine Dharma in the southwest [西南善法堂; Seinan zenpōdō]. In this version, the Hall of Fine Dharma is placed in the foreground, while the Pārijāta Tree is situated in the central background, directly opposite. The area surrounding the Pārijāta Tree appears as an empty square.

Figure 5 is nearly identical to

Figure 4. The headword “Shumisenzu” [須彌山圖, Mount Sumeru] is written in a frame in the upper right corner, and “Tōhoku enshōju” is inscribed horizontally in white text on a black background at the centre of the upper section. In the margins next to Mount Sumeru, the right side features the note, “the distance from the sun, moon, and earth is 40,000 yojanas,” while the left side includes the descriptions, “the north is yellow, the south is blue, the east is white, and the west is crimson. The mountain is dyed in colours,” as well as “the height of the Trāyastriṃśa Heaven is 80,000 yojanas.” Interestingly, the phrase “the mountain is dyed in colours [

someiro no yama]” is a pun on “

someiro”, a transliteration of Sumeru from Sanskrit, though these colours differ from those traditionally associated with the four cardinal directions in China. The locations of the palaces and the Pārijāta Tree on the summit are nearly same to those in

Figure 4.

Figure 6 is from the Meiji period. Its title, “Shumisenzu”, is framed and placed in the upper right corner, and “Tōhoku enshōju” is written horizontally within a frame above the mountain. In later depictions, the Pārijāta Tree increasingly becomes the focal point at the summit of Mount Sumeru. The shape of Mount Sumeru follows the same pattern, narrowing at the hillside near the Cāturmahārājakāyika Heaven before expanding into an inverted triangle. Palaces on the summit are positioned further inward and appear larger compared to those in

Figure 3, 4, and 5. Although the Pārijāta Tree is not explicitly annotated here, it is likely presented by the conifer-like tree on the right side.

From the above analysis, it is evident that the Pārijāta Tree’s representation exhibits both continuity and variation across different periods. Its image is deeply embedded in Japanese classical literature, where it is prominently featured as a leading symbol among depictions of trees. Notably, in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, “Shumisenzu” as the main title is positioned at the top centre. However, in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, “Shumisenzu” has been relocated to the right side, while the top centre features “Tōhoku enshōju” instead. This change indicates that in the later period, the Pārijāta Tree was depicted with special meanings as a central point at the summit of Mount Sumeru.

5. Envisioning the Cosmic Trees Within Environmental Literature

The preceding discussion, though limited in scope to literature on Mount Sumeru, explored the Pārijāta Tree as a landmark of the very mountain at the centre of Asian cosmology. The Pārijāta Tree can indeed be regarded as one of the Cosmic Trees, deeply embedded in cultural and spiritual consciousness. It is a crucial figure for understanding Asian cosmology and worldviews; meanwhile, as a tree, a living being that has always been closely tied to human daily life, it is also deeply relevant to the environmental issues being increasingly highlighted in the Anthropocene era.

In recent years, the field of the environmental humanities has emerged from within the broader domain of the humanities, aiming to address such ecological concerns. Williams (1997) suggests, “in the academic community, scholars from a variety of disciplines have evaluated Buddhist perspectives on nature [and] ecological ethics. … Buddhologists have focused on Buddhist Sūtras and other textual sources.” However, in contrast to the significant progress made in environmental history, scholarly engagement with Buddhist texts from the perspective of environmental literature remains noticeably underdeveloped.

For example, in the field of Japanese classical literature, a groundbreaking essay collection titled Nihon to higashi ajia no kankyō bungaku [Environmental Literature in Japan and East Asia], edited by Komine Kazuaki and featuring contributions from over forty scholars from Japan and abroad, was published as recently as 2023. The collection explores a wide range of topics related to environmental literature, covering regions including Japan, China, the Korean Peninsula and Vietnam. They focus on classical literature from both Japanese and foreign contexts, primarily examining themes that are deeply connected to everyday life, such as seasons, weather, disasters and creatures. Despite the strengths of these approaches, they nonetheless leave the impression that issues concerning the imagined dimension, which is shaped through deep engagement with the natural environment, remain relatively underexplored. Thus, I would suggest that such fundamental themes of cosmology or worldview ought to be actively pursued as critical concerns within the framework of environmental literature, as Williams (1997) also emphasises, the various ways in which Buddhism, through its distinctive worldview and practices, has permeated the environmentalist community.

Giant trees possess an innate power to draw people toward them; their very presence often becomes a spiritual or emotional anchor for human communities. Such trees may serve as orienting markers around which people gather, forming original points of departure and return. Religious practitioners have drawn inspiration from natural objects in envisioning cosmological concepts, as exemplified by the imagined Pārijāta Tree in Buddhism and those which take the central position in many other cosmological discourses like the “World Tree”. This engagement with the natural world reflects a broader philosophical perspective within Buddhism, often expressed in phrases like “

sansen sōmoku shitsū busshō”, meaning “mountains, rivers, grass and trees, all possess Buddha-nature.” Today, some Buddhist temples and practitioners continue to embody this philosophy through active involvement in environmental protection efforts, such as forest conservation.

22As a cosmic tree, the Pārijāta Tree serves as an emblematic presence on Mount Sumeru, the axis of Asian cosmology. It should not be understood merely as an imaginary figure, but rather as a cultural artefact shaped through human interaction with the natural world. It should be examined in relation to real-world trees as part of the dynamic interplay between imagination and material ecology.

6. Conclusions

Although this study does not encompass all literature related to Mount Sumeru, it has examined the Pārijāta Tree as a central element of the mountain, the heart of Asian cosmology. The analysis has drawn on Chinese Buddhist texts, notable depictions of Mount Sumeru in the Dūn Huáng and Harvard handscroll paintings, and representations in classical and late-mediaeval Japanese literature. Additionally, it has explored discourses on trees in other Buddhist texts, particularly A Forest of Pearls from the Dharma Garden, to address issues related to tree felling and preservation.

Trees in Buddhist literature often symbolise coexistence and ecological balance. This theme, deeply intertwined with daily life, is reflected in Chinese translations of Buddhist texts. The Pārijāta Tree, as a cosmological symbol of the heavenly realm, embodies the harmony and sustenance of life on Earth. Just as Mount Sumeru serves as a metaphor for indomitability and immensity, the Pārijāta Tree represents the journey of enlightened practitioners. Its image has been deeply engraved in cultural and spiritual consciousness.

Based on my previous research

23, extant visual depictions of Mount Sumeru from India are extremely rare. Preserved in the

Tripiṭaka, the Indian discourses are primarily text-based, rather than pictorial. As a result, comparative studies involving Indian visual representations of Mount Sumeru are limited due to this lack of surviving imagery.

Most of the existing visual representations are found in China and Japan, with the Japanese versions largely derived from Chinese traditions. While this study has focused primarily on premodern examples from China and Japan, the Mount Sumeru cosmology is not limited to these two contexts. The idea is shared in Sinosphere, including the Korean Peninsula and Vietnam, and even extends into the wider pan-Asian area. Closely connected to Tibetan Buddhism and deeply embedded in various Buddhist cultures throughout Southeast Asia, this cosmological view invites further investigation in other regional contexts, which I hope to address in future research. Furthermore, beyond the motif of Mount Sumeru itself, representations of the otherworld, such as Hell, paradise and dragon palace, which are common across East Asia, should also be examined as part of a broader exploration of imagined cosmographies.