An Ambitious Itinerary: Journey Across the Medieval Buddhist World in a Book, CUL Add.1643 (1015 CE)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Manuscript

3. The Program

4. Transporting Visions

5. Buddha in the Great Ocean

6. Epilogue

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Fol. No. | Painted Panel(s) Placement [Left-Center-Right] | Specificity Level | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fol.1v | Yellow Paper Replacement | |||||

| Fol.2r | Dīpaṅkara in Java island [Java] (yavadvīpe dīpaṅkara) | D | ||||

| Fol.5v | Vajrasattva on Mt. Meru (sumerovajrasatvaḥ) | E | ||||

| Fol.8v | Dīpaṅkara in Sinhala island [Sri Lanka] (sinhaladvīpe dīpaṅkara) | D | ||||

| Fol.11v | Lokanātha on Mt. Kapota in Magadha [Bihar] (magadhe kāpotaparvate lokanāthaḥ) | C | ||||

| Fol.13v | Prajñāpāramitā on vulture peak [Rajgir, Bihar] (gṛdhrakūṭaparvate prajñāpāramitā) | A | ||||

| Fol.14r (Ch.1 ends) | Svayambhū-Lokanātha, Nepal [Nepal, Kathmandu valley, Bunga-dyah] (nepāle svayamṁbhūlokanāthaḥ) | A | ||||

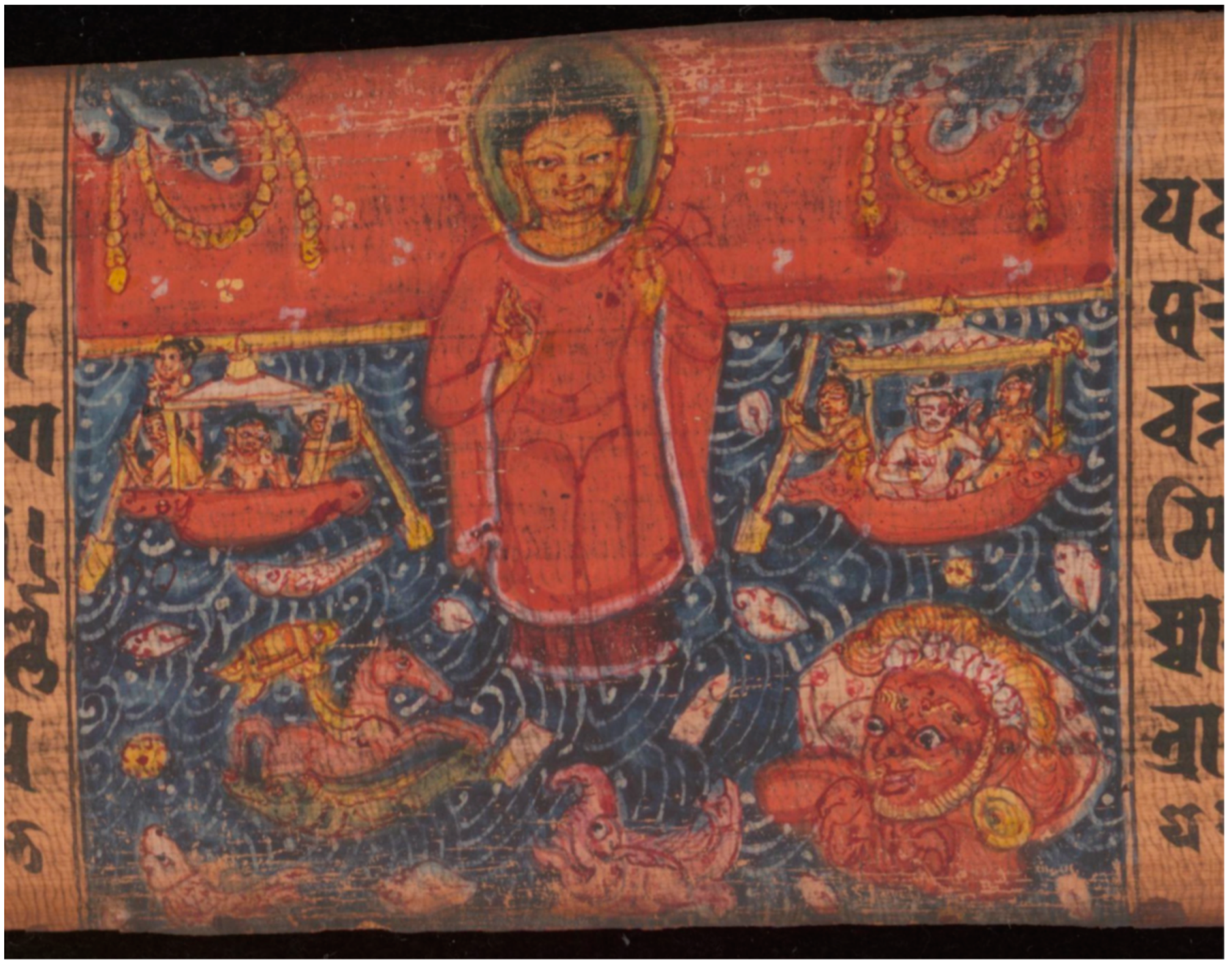

| Fol.20v (Ch.2 ends) | Rāhukṛta-Abhayapāṇi in Great ocean (mahāsamudre rāhukṛta-abhayapāṇi), Maldives? | Preaching Buddha in Punḍavardhana [ Mahasthangarh, Bangladesh] (puṇḍavarddhane triśaraṇa-buddhabhaṭṭārakaḥ) | D-B | |||

| Fol.40v (Ch.3 ends) | Macchītivahti-Lokanātha in Magadha [Bihar] (magadhe macchītivahti-lokanāthaḥ) | Maitreya in Tuṣita heaven (tuṣitabhavane maitreya) | D-E | |||

| Fol.44r (Ch.4 ends) | Buddha of Gandhavati [lit. fragrant lord], Kalaṣavarapura (kalaṣavarapure gandhavatyā bhagavān) | Buddha in Trāyatriṁśa heaven (trāyatriṁśe bhagavān) | ?-E | |||

| Fol.59r (Ch.5 ends) | Vardhamāna stūpa of Tulakṣetra [Śrīksetra in Burma? But later it has Varendra attached to Tulākṣetra on folio 174] (tulākṣetra-varddhamāna-stūpaḥ) | Tārā (of forest) in Vārendra [Northern Bangladesh/northeastern W. Bengal] (vārendrā-vāṇā-icchā-mahāttarāyī) | D-D | |||

| Fol.74v (Ch.6 ends) | Preaching Buddha in Yānavyūha [Sarnath?] (yānavyūha-bhagavan) | Tārā in Potalaka (potalake bhagavī-tārā) | ?-B | |||

| Fol.80v (Ch.7 ends) | Tārā in Candradvīpa [SE Bengal] (candradvīpe bhagavatī-tārā) | Jambhala in Sinhala Island [Sri Lanka] (sinhaladvīpe jambalaḥ) | B-D | |||

| Fol. 86r (Ch.8 ends) | Campitalā-Lokanātha in Samataṭa [SE Bengal] (campitalā-lokanāthaḥ samātaṭe) | Ārogyaśālā-Lokanātha in Sinhala island [Sri Lanka] (sinhaladvīpe ārogaśālā-lokanāthaḥ) | D-D | |||

| Fol.89r (Ch.9 ends) | Lokanātha in Mt. Kuṭa in Gandhara [NW Pakistan] (gandhāramaṇḍale kūṭaparvate lokanāthaḥ) | Maṅgakoṣṭa-Vajrapāni in Oddiyana [Swat Valley, Pakistan] (ottiyāna-maṅgakoṣṭa-vajrapāṇi) | C-C | |||

| Fol.99v (Ch.10 ends) | Lokanātha in Śrīvijayapura in Suvarṇṇapura [Palembang, Sumatra?] (suvarṇṇapure śrīvijayapure lokanātha) | Tārā in Tārapur, Laṭadeśa [Broach, S. Gujarat] (lahtadīse tārapure tārā) | B-C | |||

| Fol.120(a)r [109] (Ch.12 ends) | Lokanātha [South India?] ([dakṣiṇāpathe mūl..?] lavāsa-lokanāthaḥ) | Lokanātha in Mt. Valavatī in Kahṭāhadvīpa [modern day Kedah near Penang, Malaysia] kahtāhadvīpe valavatīparvate lokanāthaḥ] | D-A | |||

| Fol.120(b)r (Ch.12 ends) | Mūlavāsa-Lokanātha in South India (dakṣiṇāpathe mūlavāsalokanāthaḥ) | Lokanātha of Mt. Valavatī, Kaṭāhadvīpa [Kedah near Penang, Malaysia] (kahtāhadvīpe valavatīparvata-lokanātha) | Tārā in Kambojadeśa [Afghanistan] (kambojadeśe tārā[ḥ]) | D – A-D | ||

| Fol.123v (Ch.13 ends) | Śrī Kanakacaitya in Peshawar, in the northern country [Shaji-ki-dheri stūpa?, Peshawar, Pakistan] (uttarāpathe puruṣapuramaṇḍale śrīkanakacaityaḥ) | Buddharūpaka-Lokanātha in Mahācīna [Lokanātha in the form of Buddha in China—Dizang] (mahācine buddharūpaka-lokanāthaḥ) | A-A | |||

| Fol.127r (Ch.14 ends) | Samantabhadra in China (mahacīne samantabhadraḥ) | Kanyārāma-Lokanātha in Radya [Radhiya, Bihar] (rādyakanyārāma-lokanāthaḥ) | Dharmarājikā-caitya in Radya [Rādhiya, Bihar] (rādyadharmarājikā-caityaḥ) | A-B-A | ||

| Fol.133r (Ch.15 ends) | Rāmājaṭa-Lokanātha in Rādya [Radhiya, Bihar] (rādyarāmājāhta-lokanāthaḥ) | Lokanātha of Yajñapiṇḍī in Daṇḍabhuktī [N.Odisha] (daṇḍabhuktau yajñapiṇḍī-lokanāthaḥ) | B-D | |||

| Fol.139r (Ch.16 ends) | Vajrāsana Buddha, Lūtū, Rāḍha [W.Bengal] (rāḍhalūtū-vajrāsanaḥ) | Vattavanā-Lokanātha in Rāḍha [W. Bengal] (rāḍhavattavanā-lokanāthaḥ) | D-D | |||

| Fol.147r (Ch.17 ends) | Bhaṭṭāraka-Valiya Lokanātha (bhaṭṭāraka-valiya-lokanāthaḥ) | Thousand-armed Lokanātha in Śivapura, Koṅkan [Shivpur?, Coastal Maharashtra] (koṅkane śivapure sahasrabhujā-lokanāthaḥ) | ?-C | |||

| Fol.151r (Ch.18 ends) | Lokanātha in Śrī-Khairavaṇa, Koṅkan [Coastal Maharashtra] (candraṭura-koṅkaṇe śrīkhairavaṇe lokanāthaḥ) | Lokanātha in Jāruha, Magadha [Bihar] (magadhe jāruhe punnavā-lokanāthaḥ) | C-C | |||

| Fol.157v (Ch.19 ends) | Tārā of Vaiśāli, Tirabhukti [Vaishali, Mithila, Northern Bihar] (tirabhuktau vaiśālī-tārā) | Lokanātha of Candragomin in Nālandā [Nalanda, Bihar] (śrīnālendrāyāṁ candragomiṇa-lokanāthaḥ) | A-A | |||

| Fol.164v (Ch.20 ends) | Vandikoṭo Lokanātha (vandikoṭo-lokanāthaḥ) | Khadiravaṇi-Tārā in Koṅgomaṇḍala [Odisha] (koṅgomaṇḍale khadiravaṇi-tārā) | ?-C | |||

| Fol.169v (Ch.21 ends) | Alagacchattra-Caitya in Odisha (oḍḍadese alagacchattra-caityaḥ) | Tārā in Tārapura, Laṭa [Broach district, S. Gujarat] (lāhtadese tārapure tārāḥ) | D-C | |||

| Fol.174v (Ch.22 ends) | Alagataru-Tārā in Odisha (oḍradese alagataru-tārā) | Lokanātha of Tulākṣetra, Vārendra (vārendrā-tulākṣetra-lokanāthaḥ) | D-D | |||

| Fol.176v (Ch.23 ends) | Cundā in Cundāvarabhavan in Paṭṭikera [Comila district, Bangladesh] (paṭṭikere cundāvarabhavane cundā) | Stūpa of Mṛgasthāpana, in Vārendrā (vārendrā-mṛgasthāpana-stūpaḥ) | C-C | |||

| Fol.179v (Ch.24 ends) | Kurukulā on Kurukulā peak, in Laṭadeśa [Broach, S. Gujarat] (lāhtadese kurukulāśikhare kurukulā) | Vedakoṭo-Lokanātha, Koratra (koratre vedakoṭo-lokanāthaḥ) | C-? | |||

| Fol.184r (Ch.25 ends) | Stone Lokanātha in Harikella [SE Bangladesh] (harikelladese śila-lokanāthaḥ) | Tārā, Varendra (varendrā-mahattarāyī-tārā) | D-D | |||

| Fol.188r (Ch.26 ends) | Lokanātha of Dedapura, Varendra (varendrā-dedapura-lokanātha) | Cundā in Vuṅkarānagara, Laṭa [Broach, S. Gujarat] (lāhtadese vuṁkarānagare cundā) | C-C | |||

| Fol.193r (Ch.27 ends) | Jayatuṅga-Lokanātha in Samataṭa [SE Bengal] (samataṭe jayatuṅga-lokanātha) | Mahāviśva-Lokanātha in Koṅkan [Coastal Maharashtra] (koṅkane mahāviśva-lokanātha) | D-D | |||

| Fol.200v (Ch. 28 ends) | Vasudhārā in Kanci in South India [Kancipuram, Tamil Nadu] (dakṣiṇāpathe kaṁcīnagare vasudhārāḥ) | Oḍḍiyana-Mārīcī (ottiyana-mārīcī) [Swat Valley, Pakistan] | B-D | |||

| Fol.202v (Ch. 29 ends) | Kurma-stūpa in Odisha (oḍradese kurmmastūpaḥ) | Mañjughoṣa in China (mahācīne maṁjughoṣaḥ) | D-A | |||

| Fol.214v (Ch. 30 ends) | Vainakā-syama-Caitya, Tirabhukti [Mithila, N. Bihar] (tirabhutau vainakā-syamacaityaḥ) | Khaḍga-caitya in Kanheri, Koṅkan [Coastal Maharashtra] (koṅkane kṛṣṇagirau khaḍgacaitya) | D-A | |||

| Fol.216v | Haladī-Lokanātha in Varendra (varendrā-haladī-lokanāthaḥ) | Candranavihāra (by Vulbhukavītarāga) in Supacanagara [Sopara Monastery] (supācanagare vulbhukavītarāgakṛta-candranavihāraḥ) | D-A | |||

| Fol.218v | Marṇṇava- Lokanātha-Caitya in Konkan [Coastal Maharashtra] (valivaṅkāṇa-koṅkaṇe marṇṇava-lokanātha-caityaḥ) | Śrī-Dhānya caitya in Ambu [Amaravati?](ambuviṣaye śrīśrīdhanyacaityaḥ) | D-A | |||

| Fol.220v | Caitya of Pratyekabuddha peak, Kanheri, Koṅkan [Coastal Maharashtra] (koṅkaṇe kṛṣṇagirau pratyekabuddha-śikhara-caityaḥ) | Tātīhā-Tārā in Rādha [W.Bengal] (rāḍhe tātīhā-tārāḥ) | A-D | |||

| Fol.221r (Ch.31 ends) | Lokanātha in Potalaka (śrīpotalake lokanāthaḥ) | Bhṛkuṭī-Tārā in Potalaka (śrīpotalake bhṛkuṭī-tārāḥ) | B-B | |||

| Fol.222r (Ch.32 ends) | Two-armed Mārīcī-caitya (dvibhujamārīcī-caityaḥ) | Jeweled lotus flower (no caption) | Disease dispelling Bhaiṣajya-bhaṭṭāraka Vajrāsana Buddha (ārogasālībhaiṣajya-bhaṭṭāraka-vajrāsanaḥ) | ?-? | ||

| Fol.222v (Colophon page) | Buddha’s birth at Lumbini (no caption) | Descent from the Trayatriṁśa heaven at Saṁkasya (no caption) | Monkey’s offering of honey at Vaiśāli (no caption) | |||

| Fol.223r (Post Colophon continues) | Taming of a mad elephant at Rājagṛha (no caption) | Miracle at Śravāsti (no caption) | Māravijaya, Enlightenment at Bodhgaya (no caption) | First sermon at Sarnāth (no caption) | Parinirvāṇa at Kuśinagara (no caption) | |

- Color coding system for geo-data specificity level.

- Green: A Level (a known site identifiable with matching geo coordinates), 15.

- Blue: B Level (town/city level centroid geo coordinates), 9.

- Orange: C level (town/city level info given but unidentified; state/region level centroid), 14.

- Yellow: D level (region/state level centroid geo coordinates), 28.

- Purple: E level (cosmological, no geo data), 3.

- White: unidentified, 7.

- White: no caption, 1.

- Grey: last two folios with Buddha’s life scenes and no captions [could be A level], 8.

| 1 | |

| 2 | Despite being an early modern site, it is worth remembering the trans-sectarian and transregional importance of the Nagore Dargah in Tamil Nadu given the importance of Nagapattinam as a port city in the context of early medieval maritime connectivity across Monsoon Asia and Buddhist presence until the Cōḻa period (Akarsh 2019; Seshadri 2009; Kulke et al. 2009; Ray 2018). As the final resting place and shrine of the sixteenth-century Sufi pir (saint) Shahul Hamid of Nagaur [Nagore] (c. 1513–1579), it attracts both Muslim and non-Muslim (mainly Hindu) devotees as observed and discussed by Vasuda Narayan (2006). Unlike other Sufi dargahs as a resting place of a Sufi saint, Shahul Hamid Nagori’s dargah is replicated in two other locations in Southeast Asia, one in Georgetown, Penang, Malaysia, and another in Singapore (Asher 2009). The miracle-working Sufi Saints whose stories/hagiographic accounts are filled with water-themed miracles—Sevea calls them “wave-surfing saints”— connected disparate communities across the sea through their shrines (Asher 2009; Sevea 2022). Asher notes how even today Muslim men going on a journey over water invoke Shahul Hamid in their prayers before, during, and after a water-bound journey (Asher 2009, p. 248). |

| 3 | “Monsoon Asia” is used here to emphasize the interconnectivity across South and Southeast Asia through sea routes; monsoon winds connected many shores of South and Southeast Asia and further to the east (to China and beyond). The concept of Monsoon Asia as a geo-cultural category is helpfully articulated by Sri Lankan archaeologist Senake Bandaranayake (Bandaranayake 2012, pp. 24–25), and further elaborated by Acri (2023). |

| 4 | |

| 5 | This is a huge change from when I first examined the manuscript at the library in 2002. There was limited access to the manuscript’s images as the only reproductions of the folios available after the on-site research were published studies, which had limited color images, and microfilms and color slides that I ordered from the library for a fee. The Cambridge digital library has revolutionized the way we access and study millennia-old palm-leaf manuscripts and will open a new era of manuscript culture studies. The library’s blog post celebrates the availability of this manuscript in its post from 9 May 2015. See https://www.cam.ac.uk/research/features/the-1000-year-old-manuscript-and-the-stories-it-tells (accessed 23 January 2025). |

| 6 | Beal’s translation of Buddhist records was published in 1884, and Foucher published his detailed study of this manuscript and the Asiatic Society manuscript of the same text A.15 in 1900. Despite its early publication, the eleventh-century date of the manuscript probably diminished its value for colonial researchers obsessed with the idea of original Buddhism and associated sites. |

| 7 | |

| 8 | If the first wave of Esoteric Buddhism’s movement across Asia (documented by Chemburkar and Acri in their map) brought about the spread of what the Tibetan classification system calls the Yoga Tantra and the centrality of Vairocana (i.e., Mahāvairocana of the Vairocanābhisambodhi sūtra), the second wave may be characterized by the rise of the transgressive tantras (the Mahāyoga/yoginī tantras, also known as the Anuttarayoga Tantra in the Tibetan classification system of Buton Rinchen Drup [bu ton rin chen ‘grub 1290–1364]) with the centrality of Akṣobhya. |

| 9 | In the pothi-format manuscript tradition, a pagination system is developed from early on partly because the folios are not bound like a codex. For a helpful table of numerals and letter numerals in medieval Sanskrit manuscripts, see (Bendall 1883). |

| 10 | These two wooden covers are most likely supplied with the manuscript later: both are painted beautifully on the interior, but they are stylistically different from each other. Both covers’ paintings are also stylistically later than the painting inside the manuscript on palm-leaf folios. It is possible that the manuscript was given a fresh makeover when it was “rescued” in 1139 (Nepala Samvat 259) with a new painting on the book covers. One of the covers perhaps got mixed up with another manuscript’s cover by accident or it could have been damaged and was refurbished with a comparable book cover from another manuscript. |

| 11 | |

| 12 | Thus, one can easily find words that begin with “lh-” in a classical Newari dictionary. According to Alexander von Rospatt, lhaṁ makes more sense in Newar phonology, and he suggests that it may mean “stone” or “rock”, which is lvahaṁ or lhvaṁ in modern Newari. Alexander von Rospatt personal communication, 5 July 2021. |

| 13 | “nepālamaṇḍalasvalaṁkāraṇāyasamyak śrīlhamvihāra iti sarvajanānurāgo yasmin vibhāti vacanaṁ sugatasya sasvat [śaśvat]” Add.1643, folio 222 verso, line 5. |

| 14 | Locke (1985, p. 421) raised the possibility of the now defunct Lam bahal or Rāma bāhāḥ in Kathmandu (near Thamel by Paknajole). Locke reports “… several of the saṁghas of Kathmandu, who worship ‘Vajrayogini’ of Sankhu as their lineage deity, worship here… KTMV gives the Newari name of this shrine as Rām Bāhā, but the people who live in the area and the people who worship their lineage deity here say Lām bāhā…” If we take Alexander von Rospatt’s suggestion mentioned in footnote 12 of “Lham” being “lvaham”, meaning stone or rock in modern Newari and look for a location associated with Buddhist communities in and around the Kathmandu Valley on the DANAM Nepal heritage documentation project website (https://danam.cats.uni-heidelberg.de/danam/) accessed on 24 January 2025, we find Lvaham hiti in the vicinity of the Vajrayogini temple complex in Sankhu, which is mentioned by Locke as having a tie to the communities that worship their lineage deity in Lam bahal. See https://danam.cats.uni-heidelberg.de/report/11a9fb53-37b3-4bf7-8422-5559a2cd7a40, accessed 24 January 2025. Notably, the Vajrayogini temple and its neighbor Jogeśvara temple at Sankhu are both believed to have been built on a single rock. Vajrayogini is worshiped as the lineage deity by many different Newar communities, and this may be a completely serendipitous coincidence, but with the hope of further research into a longue durée history of these communities, I mention this observation here. The Danam heritage database is an incredible resource but given the impressive scale, some minor mistakes are expected: the description of the Rāma bāhāḥ (Lam Bahal) mentions “Lhāṃvihāra” in two manuscripts of the AsP (CUL Add.1643 and Add.866) based on Petech (1984, pp. 36–37), but the monastery’s name is written “śrī lham vihāra” in both manuscripts. |

| 15 | Three almost rectangular blank spaces demarcated for these roundels also anticipate the design principle of painted Indic Buddhist manuscripts: triple blank spaces for painting are occasionally reserved on the first and last two pages of the manuscript. The choice of these roundels and lotus motifs also supports the suggestion that the design principle of Indic Buddhist manuscripts that were prepared as sacred, cultic objects followed that of temples serving Indic religious communities (Kim 2015). |

| 16 | I have not examined this manuscript in person, but the manuscript’s painted book covers and a folio that happens to bear the colophon are published in Pal (2003, pp. 52–53). Although we do not know what is the referent of śrīmat-mahāpratima, it most likely refers to a famous cultic image known at the time that was associated with Śrī Lham. Further research into the thirteenth-century history of the Valley is necessary to understand the referent. |

| 17 | In other words, in Add.1643, the text of folio 109 is missing, which includes the last bit of chapter 11 and the chapter 11 ending rubric, and parts of chapter 12: “-myaksaṁbuddha udyogamāpatsyate ’nuparigrahāyeti āryāṣṭasāhasrikāyāṁ prajñāpāramitāyāṁ mārakarmaparivarto nāmaikādaśaḥ [Vaidya 125]” until “…samyaksaṁbuddhānāmasya” of Vaidya 126. The transcription here is cited from the GRETIL edition: https://gretil.sub.uni-goettingen.de/gretil/corpustei/transformations/html/sa_aSTasAhasrikA-prajJApAramitA.htm, accessed on 23 January 2025. |

| 18 | It is important to ascertain the date of this repair work. The use of indigenous paper to repair old palm-leaf manuscripts is commonly witnessed in medieval manuscripts that remained in use (i.e., in worship) among Buddhist communities in Nepal. For instance, the AsP manuscript now in the Detroit Institute of Art was made in eastern India and survived in Nepal, and bears evidence of seventeenth-century Nepalese conservation efforts using paper (Bisulca and Foster 2018). Also, see the discussion of indigenous conservation practice in chapter 5 of Kim (2006). |

| 19 | The existence of this manuscript came to my attention in 2013 when a colleague forwarded the announcement of the opening of the “Pattra-leaf Sūtra Preservation institute” (Ta la’i lo ma’i dpe cha zhib ‘jug khang 贝叶经研究所) in the CCTV news report of 30 December 2013. The news report shared the video of the exhibition of palm-leaf manuscripts as part of this research institute opening in the Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR), which included a display of a manuscript nearly identical to Add.1643 from paleography to painting style to its iconographic layout. Unlike the manuscript in the Cambridge University Library, which remained in Nepal until it came out to England at the end of the nineteenth century, the copy in Tibet was most likely transported there soon after its completion in Nepal, given profuse marginalia in Tibetan writings. It is unclear from the news report whether the manuscripts shown in the report are physically located in this institute. The label accompanying the folios shown in the CCTN news video identifies the ninth century as the manuscript’s date, but this is unlikely. This news is also shared by the Institute of Archaeology Chinese Academy of Social Sciences with the image of the sister manuscript on http://kaogu.cssn.cn/ywb/news/academic_activities/201312/t20131230_3928081.shtml. |

| 20 | His name is published as Karuṇāvajra, but the colophon actually reads karuṇāpūrveṇa vajreṇa. |

| 21 | According to Formigatti (2014, p. 14), this is the only surviving witness of the Sanskrit original of the Vajradhvajapariṇāmanā. |

| 22 | He eliminated margins and extended the text to the very edges of the writing area, maximizing the use of the limited space. While writing over existing text is less common, adding a post-colophon was regularly practiced in Nepal. These later hands sometimes appear in the main body of the text as editorial hands identifying and correcting errors and missing letters or even entire phrases—a common occurrence in the AsP due to the repetition of similar iterations of the same turn of phrase. These later hands bear witness to how these manuscripts were treated and used over many centuries within a changing community. See the discussion in Kim (2006, 2013). |

| 23 | The original total number would have been forty-three painted folios since the first folio was replaced much later, probably in the nineteenth century, and this may coincide with the addition of the pagination in Nāgarī-based numerals on the right-hand side of each page’s verso. |

| 24 | |

| 25 | |

| 26 | Three cosmological locations include Mountain Meru where primordial Vajrasattva sits (here Sumeru, folio 5v), Tuṣita heaven where the future Buddha Maitreya awaits his turn (folio 40v), and Trayatriṁśa heaven where the Buddha went to preach to his late mother (folio 44r). |

| 27 | Although the iconographic program and readings of captions are available in published studies (Foucher 1900–1905; Kim 2013, 2014), there are errors in readings and identification of sites, thus I present here an updated version. For instance, Kim (2013, 2014) identified six sites in the ancient region of Rāḍha in West Bengal despite reading two different spellings in the text, rādya (folio 127r center and right panels; folio 133r left panel) and rāḍha (folio 139r left and right panels; folio 220v right panel). As Foucher (1900–1905) suggested, the sites in rādya should be identified with the locations in today’s Radhya in East Champaran district in Northern Bihar; the table has been updated accordingly. Furui (2022, 2023) helps refine the location information for sites in medieval Bengal. |

| 28 | The prevalence of locations in ancient regions of undivided Bengal (thirteen entries) is noticeable, especially for the specificity of each sub-region identified in the captions (Samatata, Pundavardhana, Varendra, Candradvipa, Pattikera, and Harikella), which supports the close connection between Bengal (undivided, cultural region) and Nepal (specifically the Kathmandu Valley, known as nepāla maṇḍala or Nepal Mandala) during the medieval period suggested by others (Huntington and Bangdel 2001; Losty 1989) and observed until this date (Lewis 2023). Further analysis of these interregional and transregional relationships as gleaned from the location data will be published in a subsequent study. Sircar (1960, 1967) remains an important guide to study the toponyms in ancient and medieval epigraphic records and identify their geographical reference points. |

| 29 | Granoff (2018) attempted to demonstrate the relationship between the text and the images in Add.1643 with the assumption that previous studies did not read the immediate text next to the images. Despite her careful reading of the text, she finds that there is no direct relationship between the text and the images in Add.1643. Instead, she locates Add.1643’s choice of famous temples and images in the context of “a rich artistic tradition of depicting famous temples and images and mapping the cosmos”. Her attempt to locate this programmatic impulse in the larger cultural context of Indic religious communities includes Jain examples of depiction of pilgrimage sites and an earlier Buddhist practice of embodying the cosmos on the body of the Buddha from Central Asia and China. This method is admirable, but the Jain examples she cites all date later than Add.1643 and its kin (i.e., of the thirteenth century or later as opposed to the eleventh and the twelfth centuries) and the Cosmic Buddha iconography’s connection to the world of Add.1643’s makers is tangential and ahistorical given their early dates (sixth and seventh centuries). By relegating Add.1643’s innovative artistic program to a very broad, sweeping historical trend (her examples span almost a thousand years covered), this approach misses an opportunity to appreciate the genuine contributions of the Newar Buddhist manuscript makers (scribes, painters, and knowledge experts) and their community patrons. Here, we have a specific South Asian Buddhist community that made such novel choices to record a broad sacred geography of pilgrimage sites and cult images pictorially and textually at the turn of the millennium in the Kathmandu Valley. It seems Granoff (2018) was not aware of Kim (2014). |

| 30 | As Granoff (2018) mentions, the painted dhoti of Avalokiteśvara at Alchi’s Sumtsek is a great example that shows this impulse, featuring famous sites of Kashmir. Although Granoff assumes the date of this mural to be the eleventh century based on the date from Peter van Ham’s recent publication (2017), the date of this shrine and its paintings is not settled. Christian Luczanits’ and Roger Goepper’s conservative dating of the early thirteenth century (ca. 1220 CE) based on inscriptions on-site and other historical records still holds strong (Goepper and Luczanits 2023). See (Quill 2023) for a helpful introduction to Alchi Sumtsek with references to the most recent scholarship. |

| 31 | A structural emphasis on the middle of the book, with an additional number of painted panels in the middle of the manuscript, which often falls around chapter 11 or chapter 12, is common in medieval Indic Buddhist manuscript design. |

| 32 | The caption on folio 120(a) has āriṣasthāna after lokanāthaḥ, a phrase that disappears from the caption after this point in the manuscript. Foucher proposed to read this text as ālikha-sthāna, i.e., a place for an image. Parts of some letters are still visible on the caption of folio 120(a): it does seem to have “dakṣiṇāpathe -XX yaṁvāsa lokanātha”; the missing letters may be mūla and it has the additional letter ya or yam in front of vāsa. What “Mūlavāsa” or “mūlaya[ṁ]vāsa” refers to requires further research. The designation of “dakṣiṇāpatha or the southern region” and the non-specificity of the image in both cases—both depict a four-armed standing Avalokiteśvara, with green Tārā holding a utpala and four-armed yellow Bṛkuṭī against the red backdrop—suggest the second-hand nature of the information. |

| 33 | The jewelry is also depicted differently with folio 120(b) showing simpler ornaments and a single strand of necklace against double stands of necklace in folio 120(a), suggesting these details were mostly left to artists’ discretion. |

| 34 | Again, the caption of folio 120(a) is followed by dvādasaparivartta-āriṣa × X × [sthāna], i.e., “chapter 12, image (?) placement”. |

| 35 | This geometric pattern that often includes three-dimensional beams stacked together is already seen in the fifth-century murals at Ajanta. |

| 36 | For instance, in verse 49 of chapter 42 of the citrasūtra section of the Viṣṇudharmottara purāṇa, a text datable to sometime between 450 and 650 CE, we find sādṛśyakarṇam (i.e., painting as seen) as the ideal to pursue in painting (Mukherji 2001, pp. 202–3), but this “verisimilitude” is iconographic rather than stylistic, and capturing the essence of what is seen is the ideal. For example, verse 50 of Adhyāya 42 reads “… men in every land should be painted just as they are, after understanding [their] appearance, the way they dress and [their] colour”. The whole chapter describes various types of people and how they are supposed to be depicted, and the language of description is either metaphoric or iconographic, for example, with an explanation of attributes, types of clothes, headgear, and skin colors. |

| 37 | It is possible that now unnamed artists had seen some of these sites in person, but this possibility does not change the suggestion that what it looked like would have relied on one’s memory, which would have been activated through verbal cues of storytelling. |

| 38 | Foucher identified this site with the site of Lauriya Areraj in east Champaran district, near the city of Radhiya, northern Bihar. |

| 39 | I thank Arlo Griffiths for sharing the details of the reading of this inscription by him and his colleagues before publication. |

| 40 | In fact, the seventh-century inscription from Oc Eo records a grant made by King Jayavarman I to a monastery called Candana (śrī-candana-vihāra) for “the annual procession of the image of the Buddha on the full moon day of the month of Vaiśākha (April–May)” (Chhom et al. 2025, p. 148) Although almost four centuries later, is it possible that this painting remembers this practice of this annual procession of the image of the Buddha, represented by the floating standing monastic figure/Buddha (the top is damaged and it is difficult to determine the presence of uṣṇīṣa)? If so, it would be striking evidence of the longevity of the grant made by Jayavarman I and the Candana vihāra’s continued connection with Southeast Asia for subsequent centuries since the initial grant. |

| 41 | Foucher suggests alaga should be read as alagna, i.e., not joined, detached. The word “alag” in Hindi, Odiya, and several other North Indian languages means “separate”. I believe the choice of alaga is not necessarily a scribal mistake but rather a vernacular impulse coming through in this para-textual space in a canonical Sanskrit text. |

| 42 | An example of such a story from Odisha that I know of relates to the levitating idol of the Sun Temple at Konarak, a monumental building that served as a beacon for sailors for centuries and dates about two centuries later than Add.1643. |

| 43 | |

| 44 | Atīśa may have chosen to go with the Newar merchants in the first place for their shared Buddhist connection. |

| 45 | For examples of painted images of Raktayamāri, see the images in the Himalayan Art database: https://www.himalayanart.org/search/set.cfm?setID=2698/. |

| 46 | Granoff (2018, p. 23) suggests that the choice of mahāsamudra as the site of Buddhist protection may relate to Rāhu’s palace in the ocean known “from other Buddhist texts”, but one wonders if the “Great Ocean or Mahāsamudra” in the caption refers to the Indian Ocean in the context of eleventh century Nepal. |

| 47 | As mentioned by Gippert (2013), the destruction of nearly all Buddhist artifacts in the National Museum of Male by extremists on 7 February 2012 jeopardized future research on the Buddhist heritage of the Maldives. One skepticism over the Maldives identification would be the country’s geological condition: at least today, the Maldives is the lowest-lying country on Earth. |

| 48 | For example, see Avukana Buddha (https://images.app.goo.gl/D2B7k1QNKVGajySx6) and Reswehera (Sasseruwa) Buddha (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:RESWEHERA_BUDDA_STATUE.jpg). |

| 49 | For instance, the Leishan Giant Buddha in Sichuan, China, is a monumental rock-cut sculpture at 233 feet (71 m) in height, and this statue is strategically located at the dangerous confluence of rivers with expressed wishes to offer protection, both spiritual and worldly, i.e., averting perils in raging rivers. I thank Huirong Ye, a student in HAA81 in Fall 2023 for sharing her insightful analysis of the Leishan Giant Buddha’s ecological and cartographic significance. |

| 50 | The popularity of Dīpaṅkara Buddha witnessed in these eleventh-century Nepalese manuscripts may also be connected with the famed Indian Buddhist master, Atīśa, whose full name is Dīpaṅkaraśrījñāna. In today’s Kathmandu, the festival of Dīpaṅkara during the Newar month of Gunla includes a procession of huge, masked effigies of Dīpaṅkara. Atīśa is supposed to have stayed at Bhagavan Baha in Thamel, and more research into the early history of Dīpaṅkara in Nepal is necessary to uncover this link. I thank Todd Lewis for sharing his observation about Dīpaṅkara’s potential connection to Atīśa. See Brown (2014), for the importance of Dīpaṅkara rituals in today’s Newar Buddhism. |

| 51 | On Buṅgama Lokeśvara, also known as Buṅgadya or Rāto Matsyendranāth, see Dhingra (2019) and Tuladhar-Douglas (2006), chapter 5. Given the name of Buṅgama given to the red Avalokiteśvara in A.15, one wonders if the epithet of svayambhū for a red Avalokiteśvara on fol. 14r of Add.1643 may mean the nature of this image, i.e., self-risen, rather than the place, the Svayambhū caitya as suggested above. |

| 52 | We can compare this iconography with the famous Reting Tārā in the Walters Art Museum (John and Berthe Ford collection): https://art.thewalters.org/object/F.112/. |

| 53 | My reading of captions is mostly the same as that of Foucher published in 1900, except for a few examples. |

References

- Acri, Andrea. 2016. Introduction: Esoteric Buddhist Networks Along the Maritime Silk Routes. In Esoteric Buddhism in Mediaeval Maritime Asia: Networks of Masters, Texts, Icons. Edited by Andrea Acri. Singapore: ISEAS Publishing, pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acri, Andrea. 2019a. Imagining Maritime Asia. In Imagining Asia(s): Networks, Agents, Sites. Edited by Andrea Acri, Murari K. Jha, Sraman Mukherjee and Kashshaf Ghani. Singapore: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute, pp. 36–59. [Google Scholar]

- Acri, Andrea. 2019b. Navigating the ‘Southern Seas’, Miraculously: Avoidance of Shipwreck in Buddhist Narratives of Maritime Crossings. In Moving Spaces: Creolisation and Mobility in Africa, the Atlantic and Indian Ocean. Edited by Marina Berthet, Fernando Rosa and Shaun Viljoen. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 50–77. [Google Scholar]

- Acri, Andrea. 2023. Revisiting the Monsoon Asia Idea: Old Problems and New Directions. In Monsoon Asia: A Reader on South and Southeast Asia. Edited by David Henley and Nira Wickramasinghe. Leiden: Leiden University Press, pp. 63–96. [Google Scholar]

- Acri, Andrea, Roger Blench, and Alexandra Landmann. 2017. Introduction: Re-Connecting Histories across the Indo-Pacific. In Spirits and Ships: Cultural Transfers in Early Monsoon Asia. Singapore: ISEAS Publishing, pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Akarsh, Raghunath. 2019. The Tamil Buddha Art, Epigraphs and Religious Networks of Buddhism in Tamilakam (c.6th to 13th centuries CE). Master’s dissertation, Buddhist Art: History and Conservation, Cortauld Institute of Art, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Asher, Catherine B. 2009. The Sufi Shrines of Shahul Hamid in India and Southeast Asia. Artibus Asiae 69: 247–58. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20801622 (accessed on 16 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Bandaranayake, Senake. 2012. Sri Lanka and Monsoon Asia: Hypotheses on the Unity and Differentiation of Cultures. In Continuities and Transformations: Studies in Sri Lankan Archaeology and History. Edited by Senake Bandaranayake. Colombo: Social Scientists’ Association, pp. 22–55. [Google Scholar]

- Beal, Samuel. 1906. Si-yu-ki. Buddhist Records of the Western World. Translated from the Chinese of Hiuen Tsiang (A.D.629). London: K. Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Bendall, Cecil. 1883. Catalogue of the Buddhist Sanskrit Manuscripts in the University Library, Cambridge, with Introductory Notices and Illustrations of the Palæography and Chronology of Nepal and Bengal. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattarai, Bidur. 2019. Dividing Texts: Conventions of Visual Text-Organisation in Nepalese and North Indian Manuscripts, 1st ed. Berlin: De Gruyter, vol. 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchini, Francesco. 2024. Invoking the Goddess along the Southern Silk Roads: A transregional survey of Prajñāpāramitā protective texts. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 34: 855–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisulca, Christina, and Christopher Foster. 2018. Perfection of Wisdom—A Spectroscopic and Microscopic Analysis of a Twelfth-Century Buddhist Sūtra. Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts 92: 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bopearachchi, Osmund. 2022. Indian Ocean Trade through Buddhist Iconographies. In The Maritime Silk Road: Global Connectivities, Regional Nodes, Localities. Edited by Franck Billé, Sanjyot Mehendale and James W. Lankton. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 243–66. [Google Scholar]

- Boucher, Daniel. 1991. The Pratītyasamutpādagāthā and Its Role in the Medieval Cult of the Relics. The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 14: 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Brancaccio, Pia. 2020. Monumental Rock-Cut Image from Sri Lanka: New Perspectives. In Bridging Heven and Earth: Art and Architecture in South Asia, 3rd Century Bce-21st Century Ce. Edited by Laxshmi Rose Greaves and Adam Hardy. New Delhi: Dev Publishers & Distributors, pp. 175–83. [Google Scholar]

- Brancaccio, Pia. 2023a. Indo-Mediterranean Trade and the Western Deccan Ports. BYRSA: Scritti sull’Antico Oriente Mediterraneo 43–44: 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Brancaccio, Pia. 2023b. Sopara, Kanheri, and the Early Buddhist Landscape on the West Coast of India. Paper presented at the Symposium Tree & Serpent: Early Buddhist Art in India and Its Global Reach, Metropolitan Museum, New York, NY, USA, September 29–30. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Kerry Lucinda. 2014. Dīpaṅkara Buddha and the Patan Samyak Mahādāna in Nepal: Performing the Sacred in Newar Buddhist Art. Ph.D. dissertation, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarti, Ranabir. 2021. An Enchanting Seascape: Through Epigraphic Lens. In Trade and Traders in Early Indian Society. London: Routledge, pp. 263–76. [Google Scholar]

- Chhom, Kunthea, Dominic Goodall, and Arlo Griffiths. 2025. A Buddhist Procession Inaugurated in a 7th-century inscription from Oc Eo (K. 1426) and the ancient toponym Tamandarapura. Journal of the Siam Society 113: 141–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimpa, Alaka Chattopadhyaya, and Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya, eds. 1970. Tāranātha’s History of Buddhism in India. Shimla: Indian Institute of Advanced Study. [Google Scholar]

- Decleer, Hubert. 1995. Atiśa’s Journey to Sumatra. In Buddhism in Practice. Edited by Donald Lopez Jr. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 409–18. [Google Scholar]

- De Saxcé, Ariane. 2022. Networks and Cultural Mapping of South Asian Maritime Trade. In The Maritime Silk Road: Global Connectivities, Regional Nodes, Localities. Edited by Franck Billé, Sanjyot Mehendale and James W. Lankton. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 129–47. [Google Scholar]

- Dhingra, Sonali. 2019. Hindu-Buddhist Intersections in the Art of Nepal: Images of Avalokiteśvara. In Dharma and Puṇya: Buddhist Ritual Art of Nepal. Edited by Jinah Kim and Todd Lewis. Leiden and Boston: Hotei Publishing, pp. 128–41. [Google Scholar]

- Formigatti, Camillo A. 2014. The Illuminated Perfection of Wisdom. In Buddha’s Word: The Life of Books in Tibet and Beyond. Edited by Mark Elliott, Hildegard Diemberger and Michela Clemente. Cambridge: Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge, pp. 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Foucher, A. 1900–1905. Étude sur l’iconographie Bouddhique de l’Inde, d’après des Documents Nouveaux. Paris: A. Leroux. [Google Scholar]

- Furui, Ryosuke. 2022. Early Medieval Bengal. In Oxford Encyclopedia of Asian History (Online). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Available online: https://oxfordre.com/asianhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277727-e-658 (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Furui, Ryosuke. 2023. Buddhist Vihāras in Early Medieval Bengal:Organizational Development and Historical Context. Buddhism, Law and Society 7: 99–142. Available online: https://hal.science/hal-04100180 (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Gippert, Jost. 2004. A Glimpse into the Buddhist Past of the Maldives I. An Early Prakrit Inscription. Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde Südasiens und Archiv für indische Philosophie 48: 81–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gippert, Jost. 2013. A Glimpse into the Buddhist Past of the Maldives: II. Two Sanskrit Inscriptions. Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde Südasiens und Archiv für indische Philosophie 55: 111–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goepper, Roger, and Christian Luczanits. 2023. Alchi: Ladakh’s Hidden Buddhist Sanctuary. Chicago: Serindia Publications, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Granoff, Phyllis. 2018. Reading Medieval Buddhist Manuscripts: Thoughts on Text and Image. Hualin International Journal of Buddhist Studies 1: 14–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, John. 2019a. Long Distance Arab Shipping in the 9th Century Indian Ocean: Recent Shipwreck Evidence from Southeast Asia. Current Science 117: 1647–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, John. 2019b. Shipwrecks in Late First Millennium Southeast Asia: Southern China’s Maritime Trade and the Emerging Role of Arab Merchants in Indian Ocean Exchange. In Early Global Interconnectivity Across the Indian Ocean World. Edited by Angela Schottenhammer. Cham: Palgrve Macmillan, pp. 121–63. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington, John C., and Dina Bangdel. 2001. A Case Study in Religious Continuity: The Nepal-Bengal Connection. Orientations 32: 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jinah. 2006. Unorthodox Practice: Rethinking the Cult of Illustrated Buddhist Books in South Asia. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jinah. 2013. Receptacle of the Sacred: Illustrated Manuscripts and the Buddhist Book Cult in South Asia. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jinah. 2014. Local Visions, Transcendental Practices: Iconographic Innovations of Indian Esoteric Buddhism. History of Religions 54: 34–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Jinah. 2015. Painted Palm-Leaf Manuscripts and the Art of the Book in Medieval South Asia. Archives of Asian Art 65: 57–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Jinah. 2021. Garland of Visions: Color, Tantra, and a Material History of Indian Painting. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jinah. 2022. China in Medieval Indian Imagination: “China”-inspired images in medieval South Asia. International Journal of Asian Studies 19: 187–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulke, Hermann, Krishnasamy Kesavapany, and Vijay Sakhuja. 2009. Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to Southeast Asia, 1st ed. Edited by Hermann Kulke, Krishnasamy Kesavapany and Vijay Sakhuja. Singapore: Institue of Southeast Asian Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Seunghye. 2021. What Was in the “Precious Casket Seal”?: Material Culture of the Karaṇḍamudrā Dhāraṇī Throughout Medieval Maritime Asia. Religions 12: 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Todd T. 1993. Newar-Tibetan Trade and the Domestication of “Siṃhalasārthabāhu Avadāna”. History of Religions 33: 135–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Todd T. 2023. Newar Merchants in Tibet: Observations on Frontiers of Trade and Buddhist Culture. In Histories of Tibet: Essays in Honor of Leonard W. J. Van Der Kuijp. Edited by Kurtis R. Schaeffer, Jue Liang and William A. McGrath. New York: Wisdom Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Linrothe, Robert N. 1999. Ruthless Compassion: Wrathful Deities in Early Indo-Tibetan Esoteric Buddhist Art. Boston and New York: Shambhala. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, John K. 1985. Buddhist Monasteries of Nepal: A Survey of the Bāhās and Bahīs of the Kathmandu Valley. Kathmandu: Sahayogi Press. [Google Scholar]

- Losty, J. P. 1989. Bengal, Bihar, Nepal? Problems of Provenance in 12th Century Illuminated Manuscripts, Part 2. Oriental Art 35: 140–49. [Google Scholar]

- Mallinson, James. 2019. Kālavañcana in the Konkan: How a Vajrayāna Haṭhayoga Tradition Cheated Buddhism’s Death in India. Religions 10: 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markel, Stephen. 1990. The Imagery and Iconographic Development of the Indian Planetary Deities Rāhu and Ketu. South Asian studies (Society for South Asian Studies) 6: 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherji, Parul Dave. 2001. The Citrasūtra of the Viṣṇudharmottara Purāṇa = Viṣṇudharmottarapurāṇīyaṃ Citrasūtram. New Delhi: Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts and Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, Stephen A. 2018. Revisiting the Bujang Valley: A Southeast Asian Entrepôt Complex on the Maritime Trade Route. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 28: 355–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, Vasudha. 2006. Tolerant Hinduism: Shared Ritual Spaces- Hindus and Muslims at the Shrine of Shahul Hamid. In Life of Hinduism. Edited by John Stratton Hawley and Vasudha Narayan. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 266–70. [Google Scholar]

- Pal, Pradapaditya. 2003. Himalayas: An Aesthetic Adventure. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago in association with University of California Press and Mapin Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Petech, Luciano. 1984. Mediaeval History of Nepal (c. 750–1482), 2nd ed. Rome: Istituto italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente. [Google Scholar]

- Quill, Jordan. 2023. An Interwoven World: Sensory Experiences of Textiles in the Sumtsek at Alchi, Ladakh. Immediations 23. Available online: https://courtauld.ac.uk/research/research-resources/publications/immeditations-postgraduate-journal/immediations-online/immediations-no-20-2023/an-interwoven-world-sensory-experiences-of-textiles-in-the-sumtsek-at-alchi-ladakh/ (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Ray, Himanshu Prabha. 2018. Trans-Locality and Mobility across the Bay of Bengal: Nagapattinam in Context. In Cultural and Civilisational Links between India and Southeast Asia. Edited by Shyam Saran. Singapore: Springer, pp. 31–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, Himanshu Prabha. 2019. Buddhist Monuments across the Bay of Bengal: Cultural Routes and Maritime Networks. Trans-Regional and -National Studies of Southeast Asia 7: 159–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, Himanshu Prabha. 2021. Coastal Shrines and Transnational Maritime Networks across India and Southeast Asia. Abingdon and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ricci, Ronit. 2011. Islam Translated: Literature, Conversion, and the Arabic Cosmopolis of South and Southeast Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Saraswati, Sarasi Kumar. 1977. Tantrayāna Art: An Album. Calcutta: Asiatic Society. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartzberg, Joseph E., and Shiva G. Bajpai. 1992. A Historical Atlas of South Asia, 2nd ed. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, Tansen. 2006. The Travel Records of Chinese Pilgrims Faxian, Xuanzang, and Yijing: Sources for Cross-Cultural Encounters between Ancient China and Ancient India. Education About Asia 11: 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, Tansen. 2014a. Buddhism and the Maritime Crossings. In China and Beyond in Mediaeval Period: Cultural Crossings and Inter-Regional Connections. Edited by Dorothy C. Wong and Gustav Heldt. Amherst: Cambria Press, Delhi: Manohar, pp. 39–62. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, Tansen. 2014b. Maritime Southeast Asia between South Asia and China to the Sixteenth Century. TRaNS: Trans-Regional and -National Studies of Southeast Asia 2: 31–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, Tansen. 2019. Buddhism and the Maritime Crossings. In Early Global Interconnectivity Across the Indian Ocean World. Edited by Angela Schottenhammer. Cham: Palgrve Macmillan, pp. 17–50. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, Tansen. 2023. Inventing the ‘Maritime Silk Road’. Modern Asian Studies 57: 1059–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seshadri, Gokul. 2009. New Perspectives on Nagapattinam: The Medieval Port City in the Context of Political, Religious, and Commercial Exchanges between South India, Southeast Asia and China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sevea, Teren. 2022. Indian Ocean studies and saintly materials from the Islamic East. History Compass 20: e12744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, Iain. 2018. New Light on the Karimun Besar Inscription (Prasasti Pasir Panjang) and the Learned Man from Gaur. NSC Highlights 11: 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, Iain. 2019. Coronation and Liberation According to a Javanese Monk in China: Bianhong’s Manual on the abhiṣeka of a cakravartin. In Esoteric Buddhism in Mediaeval Maritime Asia: Networks of Masters, Texts, Icons. Edited by Andrea Acri. Singapore: ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, pp. 29–66. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, Iain. 2021a. Dharmakīrti of Kedah: His Life, Work and Troubled Times. Temasekm Working Paper Series 2. Singapore: Temasek History Research Centre, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, Iain. 2021b. The Last Pāla–Sena paṇḍita, Gautamaśrībhadra, at the Ends of the Buddhist Earth. Public Lecture. Berkeley: The Center for Buddhist Studies, University of California, April 8. [Google Scholar]

- Sircar, Dineshchandra. 1960. Studies in the Geography of Ancient and Medieval India. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. [Google Scholar]

- Sircar, Dineshchandra. 1967. Cosmography and Geography in Early Indian Literature. Calcutta: Indian Studies, Past & Present. [Google Scholar]

- Tuladhar-Douglas, Will. 2006. Remaking Buddhism for Medieval Nepal: The Fifteenth-Century Reformation of Newar Buddhism. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Dorothy C., and Gustav Heldt. 2014. China and Beyond in the Mediaeval Period: Cultural Crossings and Inter-Regional Connections. Amherst and New York: Cambria Press. Delhi: Manohar. [Google Scholar]

| Geo Data Level | Color | Level Specificity | Number of Panels |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Green | a known site, identifiable with matching geo coordinates | 15 |

| B | Blue | town/city level centroid geo coordinates | 9 |

| C | Orange | town/city level info given but unidentified; state/region level centroid | 14 |

| D | Yellow | region/state level centroid geo coordinates | 28 |

| Locatable subtotal | 66 | ||

| E | Purple | cosmological, no geo data | 3 |

| Unknown | White | 7 | |

| Captioned Total | 76 | ||

| No Caption | White | 1 | |

| Life Scenes | Grey | 8 | |

| Painted panels Total | 85 |

| Location | Folio/Placement | Number |

|---|---|---|

| Java | Fol.2v/center | 1 |

| Sri Lanka | Fol.8v/center, fol. 80v/right, fol.86r/right | 3 |

| Sumatra | Fol.99v/left | 1 |

| Kedah, Malaysia | Fol.120(a)v/left, fol.120(b)r/center | 2 |

| Great Ocean (Maldives?) | Fol.20v/left | 1 |

| China | Fol.123v/left, fol.127/right, fol.202v/right | 3 |

| Outside subcontinent | 11 | |

| Pakistan/Afghanistan | Fol.89r left, fol.89r, right, fol.120(b)r left, fol.123 left, fol.200v right | 5 |

| Konkan (Coastal Maharasthra, Karnataka) | Fol147r/right, fol.151r/left, fol.193r/right, fol.214v/right, fol.218v/left, fol.220v/left | 6 |

| Lata (Southern Gujarat) | Fol.99v/right, fol.169v/right, fol.179v/left, fol.188r/right | 4 |

| South India (Andhra, Tamil Nadu) | Fol.120(a)v/left, fol.120(b)r, left, fol.200v/left, [Tamil Nadu] fol.218v/right, [Andhra] fol.221r/left, fol.221r/right, fol.74v/right [Potalaka] | 7 (includes Mt. Potalaka) |

| Outside Eastern India Total | 33 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, J. An Ambitious Itinerary: Journey Across the Medieval Buddhist World in a Book, CUL Add.1643 (1015 CE). Religions 2025, 16, 900. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16070900

Kim J. An Ambitious Itinerary: Journey Across the Medieval Buddhist World in a Book, CUL Add.1643 (1015 CE). Religions. 2025; 16(7):900. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16070900

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Jinah. 2025. "An Ambitious Itinerary: Journey Across the Medieval Buddhist World in a Book, CUL Add.1643 (1015 CE)" Religions 16, no. 7: 900. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16070900

APA StyleKim, J. (2025). An Ambitious Itinerary: Journey Across the Medieval Buddhist World in a Book, CUL Add.1643 (1015 CE). Religions, 16(7), 900. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16070900