Abstract

Physical and mental health are fundamental human needs, yet modern medicine cannot always preserve them. At this point, alternative and complementary medical approaches sometimes offer significant contributions. In this context, religious healing stands out as a practice that plays a complementary role in many cultures and is frequently relied on, although it often faces criticism from the perspective of official religious doctrine. This study examines the phenomenon of “religious healing” from a sociological perspective. The provinces of Iğdır, Ağrı, and Erzurum, located in eastern Türkiye, were selected for the fieldwork. Interviews were conducted with 31 individuals who sought religious healing. The main purpose of this article is to understand the motivations of individuals who participate in such practices and how their healing experiences are transformed into religious experiences. The field data indicate that religious healing commonly involves practices such as recitation and blowing of the Qur’an, drinking blessed water, and the preparation of amulets. Feelings of helplessness and fear of social stigma are prominent in participants’ reasons for resorting to religious healers. The participants’ turn to healers can be seen as a defense mechanism, shifting blame to external forces like the evil eye, jinn, and magic, thereby reducing personal responsibility. Religion was instrumentalized to make the behavior of applying to a healer reasonable and acceptable.

1. Introduction

Religious healing is a deep-rooted practice that has persisted for thousands of years across different cultures and social structures. Although it is often thought that the interest in religious healing has declined with the advancement of modern medicine, it still holds a significant place today, sometimes functioning as a complement to contemporary medicine. The rise of alternative and complementary medical approaches has also contributed to the re-popularization of certain forms of religious healing. While some religious healing practices are accepted as rooted in sacred texts, others face criticism. Moreover, some religious healing practices have been detached from their religious context over time, becoming more secularized and revitalized in urban settings by responding to new social demands within the framework of spirituality. In recent years, social media and digital platforms have also enhanced the visibility of religious healing practices and facilitated access to wider audiences.

Indeed, in recent years, the growing visibility of religious healing practices has attracted the attention of the Presidency of Religious Affairs, the highest official body responsible for religious affairs in Türkiye. One of the Friday sermons delivered in all mosques across Türkiye in 2025 was devoted to this subject. The sermon, titled “The Knowledge of the Unseen Belongs Only to Allah,” emphasized a religion based on the Qur’an and the Sunnah. It warned that “those who practice magic and sorcery are sorcerers. Those who engage with jinn are jinn-conjurers. Those who tell fortunes are fortune-tellers. Those who write amulets for personal gain are amulet-makers. Those who claim to heal people by blowing over them are charlatans” (The Presidency of Religious Affairs 2025). The sermon highlighted that such practices are innovations (bid’ah), which are unacceptable in Islam. As a state institution, the Presidency of Religious Affairs aims to inform and warn the public about these practices, while the Ministry of Treasury and Finance has begun to regulate the revenues generated from these practices. According to a report by the state-run Anadolu Agency dated 16 March 2025, the Ministry of Treasury and Finance has launched investigations into individuals involved in activities such as fortune-telling, astrology, star chart readings, mediumship, numerology, spiritualism, cupping and leech therapy, sorcery, and meditation. Approximately a thousand individuals under scrutiny were found to have earned hundreds of millions of dollars in undeclared income (Anadolu Agency 2025). The fact that these practices have reached a level of economic activity significant enough to draw the attention of the Ministry of Treasury and Finance clearly indicates the increasing prevalence of these practices in society. Despite the persistent warnings of the Presidency of Religious Affairs that such practices harm the essence of religion, the appearance of new variants remains noteworthy. This situation underscores the necessity of examining spiritual trends and alternative religious practices on an academic level.

This study examines the phenomenon of “religious healing,” a deeply rooted tradition in popular culture that exists outside of institutional religious practices, from a sociological perspective based on field research. The research investigates religious healing practices in the Eastern Anatolia Region of Türkiye, exploring the motivations of individuals participating in these practices and how their healing experiences are transformed into a religious experience.

2. Literature Review

In the history of Islam, following the death of Prophet Muhammad and the expansion of Islam beyond the Arabian Peninsula, new religious formations began to emerge that diverged from the institutional understanding of Islam. When Islam reached Anatolia, it blended with the local cultural elements of this region. The previous religious habits of individuals who converted to Islam, along with the surrounding religious influences, gradually shaped how Islam was interpreted and practiced (Yılmaz 2014, p. 6). It is often not possible to recognize these elements that have been incorporated into the new religion through culture. Over time, they become an inseparable part of the adopted religion. For instance, Christmas, which is celebrated as the birthday of Jesus in Christianity, can be traced back to the celebrations held as a winter festival in the old pagan culture (Erkal 2024, p. 915). Clifford Geertz (1973), one of the pioneering figures of cultural anthropology, illustrated how Islam became localized in Indonesia. According to him, the Abangans adopted a syncretic understanding of Islam that was intertwined with local culture. Similar assessments apply to various geographies from Africa (Insoll 2004, p. 101; Günay 2001, p. 354) to Central Asia (Polonskaya and Malashenko 1994, p. 33; Maghsudi 2013, p. 112; Dupaigne 2013, p. 125).

Anatolia has also developed its own distinctive interpretation of Islam. The ways in which religion has taken shape in different contexts can be classified as “folk Islam,” “institutional Islam,” “Sufi Islam,” and “state Islam.” Folk Islam generally blends cultural elements and beliefs regarded as superstitions (Ocak 2007, pp. 57–67). The version of Islam adopted by nomadic Turks was largely based on oral culture and contained remnants of pre-Islamic beliefs. Since Turks inherited Anatolia as a cradle of many religions and cultures for centuries, it was natural for them to embrace pre-existing local traditions. Ahmet Yaşar Ocak (2007) suggests that many sacred sites, mountains, hills, and tree cults in Anatolia may have origins in pre-Islamic cultures. Moreover, the Islamization of the Turks occurred over time, during which they continued to practice certain shamanic traditions (Melikoff 2010, pp. 35–36; Uluğ 2017, p. 45). Hikmet Tanyu (1976) identified approximately 200 beliefs associated with religious folklore and spirituality in Anatolia. As a result, the heterodox Islam embraced by the Anatolian people has persisted throughout history in various forms. Especially during turbulent times such as natural disasters, political turmoil, and economic crises, the propensity for superstitious beliefs tends to increase (Uluğ 2017, p. 116). In this context, shrine visits stand out as one of the most prominent expressions of folk Islam. While shrine visits are commonly observed in rural areas, they also attract attention in urban settings, particularly on special religious days such as festivals and holy nights. Contemporary research indicates that interest in these practices continues today (Ak 2018; Günay 2003; Koç 2019).

Religious healing has been practiced in Anatolia for centuries as one of the significant manifestations of folk Islam. In Anatolian folk beliefs, various healing practices—especially those blending pre-Islamic elements with Islamic motifs and whose legitimacy is questioned by institutional Islam—are nowadays gaining new meaning and becoming increasingly widespread among urban upper-middle-class individuals under the umbrella of “spirituality.” Despite advances in modern medicine, the persistence of religious healing rituals reveals the vulnerability of human beings in the face of health problems and their need for spiritual quests during moments of helplessness. Christopher Dole’s (2015) study, which examines healing practices in Ankara, stands out as a significant fieldwork contributing to the understanding of the sociocultural dimensions of this phenomenon. From a broader perspective, Arthur Kleinman’s (1980) work provides a valuable framework for understanding how illness is shaped not only by biology but also by social and cultural meaning. Kleinman distinguishes between disease (biomedical dysfunction), illness (the individual’s subjective experience of being unwell), and sickness (the societal understanding and labeling of that condition). He argues that modern medicine often privileges disease while neglecting the cultural and personal dimensions of illness. This approach is particularly relevant to our field research, where many participants seek out religious healers not because of a medically diagnosable condition, but because they feel unwell and seek to make sense of their suffering. In such cases, healing is not only a physical but also a symbolic and existential process embedded in cultural narratives.

The search for religious healing can generally be divided into several categories: I. personal prayers for healing; II. the ocak tradition, which advances as an alternative to modern medicine and is also seen as a form of traditional treatment that incorporates religious rituals; III. visits to shrines and sacred sites seeking healing; and IV. visiting a person believed to possess a powerful or mystical breath and following their instructions in pursuit of healing.

I. Personal Prayers for Healing: According to the Pew Research Center’s survey results from 102 countries between 2008 and 2023, about half of these countries have a daily prayer rate above 50%. This rate is particularly high among Muslims as well as Christians in Latin America and Africa. For instance, it reaches up to 95% in Indonesia and nearly 60% in Türkiye (PEW 2024). Academic literature also devotes considerable attention to the subject of prayer, and numerous studies have explored the relationship between prayer and healing. While some studies firmly affirm the healing power of prayer (Shelly 2025), others remain skeptical of this relationship (Andrade and Radhakrishnan 2009). However, a substantial body of mental health research suggests that religious involvement is generally associated with positive psychological outcomes—such as better stress coping and lower rates of depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and suicide—across diverse populations, age groups, and cultural settings (Koenig 2009, 2012).

From an Islamic perspective, prayer is one of the most significant moments of direct communication with the Creator. In this act, individuals express their requests directly to Him. The verse, “And when My servants ask you, [O Muḥammad], concerning Me—indeed I am near. I respond to the invocation of the supplicant when he calls upon Me” (Baqarah, 2/186), illustrates this closeness between the individual and God. Similarly, the verse, “Call upon Me; I will respond to you” (Mu’min, 40/60), clearly encourages prayer. The Qur’an also mentions the prayers of prophets and other significant religious figures, such as Mary and Luqman, in several verses. Such encouragements lay a solid groundwork for the frequent practice of prayer among Muslims. In this context, certain chapters of the Qur’an are also regarded as having healing properties. Notably, the surah al-Fatiha is referred to as al-Shifa’ (the Healing), highlighting its spiritual and curative significance in Islamic tradition.

Field studies conducted on religiosity levels in Türkiye generally include questions about prayer practices. According to the results of “the Religious Life in Türkiye” survey conducted by the Presidency of Religious Affairs through the Turkish Statistical Institute, people frequently pray for all their material and spiritual needs. The percentage of those who reported never praying was strikingly low, at just 0.2% (The Presidency of Religious Affairs 2014, pp. 100–1). Moreover, individuals pray not only for themselves but also for others. In fact, prayer has increasingly functioned as a platform for social solidarity, with collective prayer gatherings being organized through social media initiatives (Demirdağ 2021).

II. The Ocak Tradition: Although individual prayer is considered a source of healing, it is sometimes not considered sufficient. Individuals may seek to combine the spiritual aspect of prayer with a tangible practice. In this regard, the ocak serves as a setting where spoken prayers merge with physical treatments. It is believed that individuals or families identified as ocaklı (healer) can cure illnesses through extraordinary means. Generally, these individuals pass on their healing abilities orally to a family member in a process known as el verme (transmission through blessing). Consequently, the ocak tradition is preserved and passed down orally from generation to generation within the same family. There are both traces of ancient Turkish beliefs and motifs from Islamic teachings in the ocak tradition (Tek 2019, p. 155). The reason we consider the ocak tradition as a separate category from those believed to have a powerful breath is that this tradition often incorporates elements that can be viewed as alternative medical practices. For example, physical interventions such as bone-setting and back adjustment are recognized as forms of complementary medicine.

Another feature of the ocak is specialization in treating specific health issues or ailments. For instance, the practice of pouring molten lead (kurşun dökme) is commonly employed to cleanse the body of negative energy or protect it from the evil eye. Lead is poured into boiling water accompanied by prayers, and the resulting shape is interpreted. Alazlama is an ailment that presents with skin redness and is treated by placing stones brought from Mecca on the diseased area while reciting verses from the Qur’an. Bulgurlama practice is used particularly for skin diseases; in this ritual, the healer conducts the treatment by spraying the bulgur grains held in their mouth onto the affected area. Temre specializes in treating a skin ailment characterized by round, red, or scaly lesions. Treatment involves encircling the lesion with a pencil mark while reciting specific Qur’anic verses, which are believed to cure the disease. Beyond these examples, dozens of other ocak traditions exist. These practices address both somatic disorders and spiritual unrest, forming a significant healing tradition among local communities (Yılmaz and Korkmaz 2021).

The most important advantage of traditional and alternative healing practices compared to modern medicine is their holistic approach, which considers the illness as part of the mind–body unity. This approach acknowledges the connection between physical and mental health and integrates both aspects into the treatment. In the ocak tradition, prayers, rituals, and physical interventions strengthen the patient’s belief in recovery, providing psychological motivation. This phenomenon shows a striking resemblance to the placebo effect, which is also recognized in modern medicine. The placebo effect refers to the generation of positive physiological responses by an otherwise pharmacologically inactive substance, triggered by the patient’s expectations and suggestions. This healing process derives its power not from the chemical composition of the drug but from the patient’s belief in the benefit of the substance or practice. In this regard, the placebo effect points to the capacity of individuals to initiate their own healing process through mental and psychological motivation, a mechanism that modern science has not yet to fully explain. Similarly, in the ocak tradition, rituals like “lead pouring” or “alazlama” can trigger the placebo effect by fostering an expectation of healing in the patient’s mind, which in turn strengthens the patient’s mental state and supports the physical healing process.

III. Visits to Shrines and Tombs: Shrine culture, including the veneration of saints and visits to shrines, is one of the most significant aspects of religious belief and a widely practiced form of religious devotion (Iloliev 2008). Seeking healing through shrine visits is a practice seen across the globe, from Brazil (Sansi 2011) to the United States (Endres 2016), from India (Ranganathan 2014) to Japan (Ohnuki-Tierney 1989), and from Ghana (Michael 2021) to Norway (Mikaelsson 2018). In 1924, anthropologists who collected 500 prayer slips from a Canton temple found that all but 16 contained prayers asking for healing for the writer or a relative (Day 1940, p. 13, as cited in DuBois 2015, p. 214). Today, shrines continue to fulfill this function, and in some cases, they even become integrated into the healthcare system. Michael’s study on sub-Saharan African healing shrines during the COVID-19 pandemic shows that “there are lively networks of referrals between African healing shrines, hospitals, and Christian healing/prayerhouses, which dramatically turned these diverse healing spaces into an animated transborder space of creative negotiation” (Michael 2021, p. 1).

Tomb visits, which can be shown among religious practices, are also frequently practiced in Türkiye. A recent study revealed that 71% of the adult population has visited a shrine at least once in their lifetime (Nişancı 2022, p. 131). Another study completed in 2000 found that over 50% of respondents had visited a saint’s tomb or shrine within the past five years (Çarkoğlu and Toprak 2000, p. 47). According to data from a 2009 study, 41% of people reported visiting these sites once a year or more (Çarkoğlu and Kalaycıoğlu 2009, p. 28). These figures highlight the significant role of shrine and saintly tomb visits among the religious practices of Turkish society.

Although visiting graves is encouraged in the hadiths because it reminds believers of death (Muslim, “Janaiz,” 106), over time, some of these visits have come to serve other purposes, such as seeking healing. According to a study by the Presidency of Religious Affairs, 8.3% of the Muslim population in Türkiye consider it acceptable to seek help for a need from a saint’s tomb or shrine (The Presidency of Religious Affairs 2014, p. 32). While the dominant spiritual sentiments during shrine visits involve finding peace and tranquility in a sacred place and seeking intercession for the afterlife, it is also frequently observed that these visits are made with the intention of finding healing (Köse and Ayten 2015, p. 391). Based on field research conducted by Ali Köse and Ali Ayten in 30 shrines, these sites are positioned as spaces where visitors connect with the sacred, nurture their spiritual feelings, and, with regard to our discussion, seek remedies for various problems (Köse and Ayten 2010, p. 14).

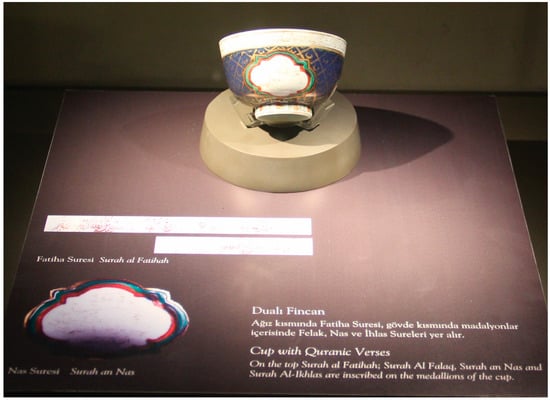

IV. Visiting Individuals Believed to Have a Powerful Breath: In the literature, this category is the least addressed aspect of religious healing. While prayer is also present in the ocak tradition, it is accompanied by physical interventions. In this distinct category, however, healing is sought primarily through prayer. Instead of direct physical interventions with the patient, spiritual and metaphysical practices such as writing amulets (muska) or drinking water over which verses from the Qur’an have been recited are utilized. In cases where direct access to the healer is not possible, healing bowls have been crafted. Frequently used during the Ottoman period, these bowls—typically made of copper, bronze, or brass—bore inscriptions of verses either on their outer surfaces or on the inside. These healing bowls are filled with clean water, zamzam, or rainwater, and then Ayat al-Kursi, along with surahs Ikhlas and Fatiha, are recited and blown over them. This water is either sprinkled over the person seeking healing or consumed. Healing pots have been utilized not only for people but also for animals (Aksoy 1976, p. 35). In some cases, inscriptions of verses similar to those on healing bowls have also been found on everyday food and drink containers. One of the most famous of these is the coffee cup used by Atatürk during the Republican period (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Atatürk’s coffee cup inscribed with Qur’anic verses, 1930s, Republic Museum (2025), Ankara.

While the rim of the coffee cup features the surah al-Fatiha, the medallion on its body includes the surahs al-Falaq and an-Nas, which are believed to provide protection against the evil eye. This particular cup is currently displayed at the Second Turkish Grand National Assembly building, now functioning as the Republic Museum, and stands as a significant example of the early Republican era’s cultural heritage. Today, these healing bowls—no longer widely used—are increasingly studied within the fields of archaeology and art history.

Despite its widespread use, sociology-based field research on amulets (muska), another object used in religious healing, remains limited. The Encyclopedia of Islam, published by the Türkiye Diyanet Foundation, addresses the topic in the entry “muska” from the perspective of the history of religions (Demirci 2020) and as a theological issue (Çelebi 2020). When examining recent studies that have indirectly addressed belief in amulets through their survey questions—both quantitative (Kandemir 2016) and qualitative (Kartopu and Ünalan 2019)—it becomes clear that amulet-related practices have garnered interest across diverse social groups. However, the quantitative study’s limited scope of questions on amulets and its sample confined to a single district, as well as the qualitative study’s small participant size of only 21 individuals, have constrained the potential for a more in-depth analysis of the subject.

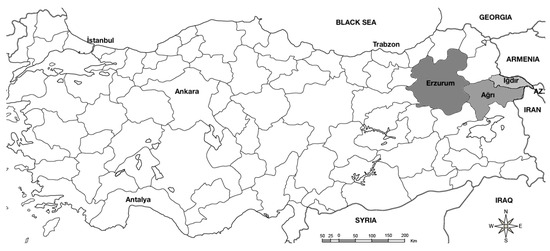

In short, our literature review reveals that academic studies on the practice of seeking healing by visiting individuals believed to have powerful breath and following their guidance are limited in Türkiye. In this respect, this study will fill an important gap. A further unique aspect of our study lies in its comparative design. The study area includes the provinces of Erzurum, Ağrı, and Iğdır in the Eastern Anatolia Region of Türkiye, chosen to represent the region’s religious diversity (Figure 2). In this respect, our research is the first of its kind in its field.

Figure 2.

Political map of Türkiye.

3. Methodology

This study adopts a qualitative research approach, based on the assumption that reality is socially constructed and multiple realities exist. The qualitative approach offers a suitable paradigm for developing an in-depth and contextual understanding of the phenomena under investigation. A fundamental characteristic of qualitative research is its focus on how individuals construct reality through their interactions with the social world. In this context, the researcher aims to understand the meaning of a phenomenon from the perspective of those directly involved in it (Merriam 2018, p. 22).

Considering the multilayered and subjective nature of reality, quantitative approaches based on questionnaires often fall short in conveying individuals’ meaning worlds and analyzing them in depth. Therefore, qualitative research approaches become especially prominent in studies examining complex and multifaceted phenomena such as religion. Unlike the positivist paradigm, the interpretive paradigm views social life not as a fixed reality “out there” waiting to be discovered, but as a dynamic process continuously constructed through individuals’ experiences, interpretations, and interactions. From this perspective, social reality is shaped and gains meaning through the interactions of individuals with each other (Neuman 2017, p. 132).

This study employs a phenomenological qualitative approach, a research design with deep roots in sociology that is increasingly being adopted in the field of health sciences (İlerisoy 2023, p. 525). The core phenomenon of this study, “religious healing,” is connected on one hand to the social and cultural dimensions within the framework of the sociology of religion and, on the other hand, to individuals’ health-seeking processes from a health sciences perspective. Since religious healing lies at the intersection of these two fields and requires an in-depth understanding of personal experiences, the phenomenological design was deemed the most suitable approach for the aims and nature of this research.

Eastern Anatolia, which preserves its cultural religious identity more than Western provinces and where religious healing practices are frequently encountered, was preferred for the research field. Considering that religious healing practices may be related to ethnic identity (Turkish, Kurdish) and sectarian affiliation (Sunni, Shia), the provinces of Ağrı, Iğdır, and Erzurum were selected for data collection, and the obtained data were compared specifically for these three provinces. The interview questions were developed with the intention of exploring participants’ motivations for seeking religious healers and delving deeply into how these experiences shape their individual religious practices. Participants were reached through purposive and snowball sampling techniques.

In this study, data collection was conducted through participant observation and semi-structured interviews consisting of 20 questions, alongside demographic information. In phenomenological studies, it is essential not only to capture participants’ genuine thoughts but also to understand the social and cultural context in which these thoughts are shaped. This context encompasses family, friends, and all social relationships participants engage in (Creswell 2016, p. 6). Therefore, for this research, the sites where participants sought healing were visited for observation, and field notes were taken. We conducted interviews with a total of 31 participants—at least 10 individuals from each of the 3 selected provinces. The necessary ethical approvals for this study were obtained from the Ethics Committee of Ankara University on 10 October 2024. The interviews, which were conducted between January and May 2025, lasted an average of 50 min. With the consent of the participants, the interviews were recorded and then transcribed. To adhere to ethical guidelines, participants’ real names were not disclosed in the article; instead, they were anonymized by province and interview sequence. For instance, the first participant from Ağrı was coded as (A1).

Research Questions

The research, in which we analyze religious healing practices in the Eastern Anatolia Region by focusing on Erzurum, Ağrı, and Iğdır provinces, has three main questions:

- What are the primary motivations that lead individuals to seek religious healing despite the warnings of the Presidency of Religious Affairs and the development of modern medicine?

- How do participants internalize such religious healing experiences, and how do they transform these practices into a religious experience?

- In what ways do the healing practices in these three neighboring provinces in Eastern Anatolia converge or diverge?

4. Results

Within the scope of the research, 31 people from 3 different provinces in the Eastern Anatolia Region were interviewed (Table 1); 10 of the participants were male, and 21 were female. The data suggest that men tend to be more distant and skeptical about such issues (A4, E8, E9). Nevertheless, one male participant rationalized his decision to consult a healer by referring the well-known proverb, “A drowning man will clutch at a snake,” to highlight his desperate hope (E8).

Table 1.

Participants and basic results.

The participants were mostly between 22 and 58 years old, with one individual aged 70. The median age was 42, and the average age was 40. In total, 5 participants were single, 25 were married, and 1 was divorced. Educational backgrounds varied widely, ranging from illiterate individuals to university graduates. There was one illiterate participant and one who had never attended school. A total of 7 had completed primary school, 11 had finished high school, and 11 held university degrees. Regarding their occupations, eight participants were housewives, and six worked in farming and livestock—reflecting the main sources of income in the study region. Additionally, some participants worked as imams (2), teachers (2), and nurses (2). The remaining 11 were employed in various other fields. Overall, most participants belonged to a middle or lower-middle income group. A notable common trait among the participants was their generally devout religious lifestyle. Some mentioned turning to religion later in life (A2, I7). Most sought religious healers for themselves, while others did so on behalf of their spouses, children, grandchildren, close relatives, or friends.

In the research area, religious healers are commonly identified by titles such as mullah, sayyid, or hodja. Healing practices are typically conducted within the healers’ residences. In terms of the people we interviewed and the places we visited, no designated office space or facility was encountered. Instead, a room in the healers’ houses or, if the layout of the house allows, a garden or a room at the entrance of the house is reserved for these practices. The size and configuration of such spaces varied according to the healer’s popularity and the breadth of their clientele. For instance, one healer we visited in Iğdır resides in a two-storey house, where visitors seeking healing are received in two pavilions located in the garden (Figure 3). These spaces were modestly arranged, consistent with the architectural character of the surrounding environment, and devoid of any ostentation.

Figure 3.

Visitor reception pavilion in the garden of M. C. Mullah, Iğdır, May 2025.

Although our study focuses solely on individuals who seek out healers rather than the healers themselves, we made efforts to visit the healers’ locations for observational purposes during the research process. These observations provided insights not only into the physical spaces but also into their surrounding social context. For instance, in Iğdır, local residents easily recognized the healer and willingly provided directions to their home, indicating that the healer is both well-accepted and respected within the community. It was observed that treats such as tea and water were offered at healers’ places. Participants stated that benefiting from these treats brought them spiritual comfort. During the observation period, numerous visitors were seen coming and going from the healer’s place. Another noteworthy aspect was that some individuals who could not physically visit the healer communicated their concerns through video calls. It was also observed that the healers spoke warmly and attentively to their visitors, smiling as they listened to their problems, and then calmly performed the necessary treatments or offered advice. The two healing sessions we attended took place in a calm and quiet environment, where from the moment we entered, the healer made a deliberate effort to instill a sense of trust that healing would occur.

5. Discussion

5.1. Reasons for Visiting Healers

5.1.1. Religious Dynamics

The first notable point in our research is that almost all of the participants we interviewed were religiously observant individuals. By religiously observant, we refer to those who actively observe the tenets of their faith—such as engaging in regular worship, adhering to the moral and legal prescriptions of Islam, and maintaining a consistent commitment to religious practices and beliefs. Among them were also individuals who had previously been distant from religion but later returned to it (A7, I7, I10). Given that the research focuses on faith-based healing practices, it might initially seem expected that participants would be committed adherents. However, the experience of seeking healing is often a deeply personal and urgent matter that can drive individuals, especially in moments of intense need or desperation, to explore any possible source of relief—regardless of their usual beliefs. Moreover, existing research indicates that the experience of seeking healing through visiting shrines and tombs is not confined to practicing believers. For example, a study by the Presidency of Religious Affairs found that 8.3% of the Turkish population considers it appropriate to turn to a shrine or tomb to fulfill a need. This rate drops to 7.8% among the religiously observant, while it rises to 17.4% among those who say they are not religious and 31.1% among those who say they are not religious at all (The Presidency of Religious Affairs 2014, p. 34). These findings suggest that the likelihood of visiting a shrine for healing is higher among non-religious individuals than their more observant counterparts. Considering this situation in tomb visits, the fact that the participants we interviewed draw a religiously active profile in general can be explained by the strong religious structure in the provinces in our research area.

Sectarian affiliation also has a significant impact on popular beliefs and religious practices. According to the Presidency of Religious Affairs, 1% of Muslims in Türkiye are Shia (Ja’fari). Twelver Shiism, also known as Imamism, is the largest branch of Shia Islam, comprising about 90% of all Shia Muslims and is referred to as Ja’fari in Türkiye. The same study found that individuals affiliated with the Ja’fari sect are approximately five times more likely to engage in shrine visits for healing than non-Shia Muslims (The Presidency of Religious Affairs 2014, p. 33). Iğdır, one of our research provinces located on the Iranian border, is home to a significant population of Turkish Shias. In the Shiite belief system, sacred places and religious figures hold a particularly high level of reverence (Balamir 2023). Responses to our questions about the religious and medical knowledge of the healers they consulted also reflected this dynamic. The data showed that the vast majority of participants had no information about the healer’s medical expertise and did not consider it necessary to inquire about it. This indicates that trust in the healer is based more on religious or traditional references than on medical competence. Only one participant mentioned that the healer she visited also had some medical knowledge (I1). Regarding religious knowledge, participants generally agreed that there are also those who engage in healing with malicious or fraudulent intent. Notably, only three participants expressed skepticism about the religious knowledge of the healer they had visited (A4, E8, E9). A shared feature among these three individuals is that none of them reported any benefit from the healer’s services.

Three key factors emerge in the trust placed in the healer’s knowledge: First, the belief that healers are sayyid, meaning they are descendants of the Prophet Muhammad, generates a high degree of trust. Since the lineage of the Prophet Muhammad continues through his daughter Fatima and her husband Ali, Shiites attribute special significance to the lineage of Ali. Ja’far al-Sadiq, considered the founder of Twelver Shiism (Ja’fariyya), defined the imamate as a right that passes from father to son. All 12 imams in Ja’fariyya descend from Ali and Fatima. For this reason, the imams are considered not only religious but also spiritual and political leaders. Because of the importance attached to the lineage of the Prophet Muhammad in Shia, sayyids occupy an eminent position.

In the Sunni tradition, although not as deeply rooted as the Shiite theology, there is a special reverence for the lineage of the Prophet Muhammad (Küçükaşçı 2009). For instance, sayyids in the Malabar diaspora are held in high esteem by the local population. These sayyids often possess extensive Hadhrami genealogical collections that connect them to a larger sayyid family network. Such collections serve not only as records of lineage but also as tools to remind younger generations of the nobility of their ancestry. Tracing their lineage back to the Prophet grants these individuals a form of charismatic authority (Hudawi and Abdul Jaleel 2011). Moreover, recent studies in Malaysia show that sayyids and Sufi leaders continue to maintain their social influence, demonstrating that figures with genealogically based charisma remain significant even under modern conditions (Woodward et al. 2012).

Hence, knowing that a person is a sayyid or attributing sayyid status naturally elevates that individual to a more valued and respected position in the community. Thus, the phenomenon of being sayyid is regarded as a religious title and a source of spiritual and social authority. The question “Can you give information about the level of religious and medical knowledge of the healer?” was answered by the Ja’fari participants in Iğdır by emphasizing that the healer was a sayyid: “The mullah I went to is a sayyid. As you know, sayyids are descendants of the Prophet” (I8). The participant seems to believe that this short, two-sentence response fully answered the question. The participant statements indicate a social trust relationship, rooted in the belief that those regarded as descendants of the Prophet Muhammad would not engage in deceitful or misleading behavior. Similarly, another participant linked the religious knowledge of the healer he visited to his sayyid status, emphasizing that sayyids do not deceive people: “The mullah I went to was a sayyid. I trust sayyids. Because they are descendants of the Prophet, they do not deceive people” (I9). Sayyids are believed to possess a powerful breath as a kind of familial inheritance: “The mullah’s ancestors were good. Because he is a sayyid, his breath is strong” (I4).

The sayyid culture is also widespread in other provinces of Eastern Anatolia. Many people trace their ancestry back to the Prophet Muhammad and take pride in it. A sense of competition in this regard is noticeable. For example, one participant from Ağrı expressed her frustration on the matter as follows: “I come from a sayyid family. If you look at our family tree, you can see this … In the East of Türkiye, everyone introduces themselves as sayyid and such, but ours is not like that” (A9). Although this participant herself graduated from a faculty of theology and her parents are both healers, she attributes her trust in her father’s spiritual and religious knowledge to his descent from the sayyid lineage, saying “I trust my father’s religious knowledge and spiritual world because he comes from a sayyid lineage” (A9).

Iranian influence is the second-most prominent factor in trust in healers in Iğdır. Participants from Iğdır stated that these healers, whom they refer to as mullahs, received their training in Iran (I1, I4, I10). In other words, the ability to heal is considered either a natural talent inherited from father to son through the lineage of the Prophet Muhammad or a spiritual capability acquired through a specialized training process in Iran: “The mullahs here have either studied in Iran or are sayyids. I trust these mullahs to truly provide healing—but only those who don’t turn it into a money-making business” (I4).

Thirdly, in our research areas outside of Iğdır, we found the influence of the Menzil Sufi order. This community, affiliated with the Naqshbandi Sufi order, is particularly widespread in the provinces of Eastern and Southeastern Anatolia in Türkiye. The order is named after the village of Menzil in Adıyaman province, where its headquarters are located. According to the beliefs of this order, the sheikh acts as an intermediary between Allah and the disciple. The disciple’s needs are presented to Allah through the sheikh, and it is believed that help will come through the sheikh’s favor in the eyes of Allah. Five of our participants are members of this community (A2, A3, A5, A6, E1). For some, joining the community occurred after experiencing a positive healing event. For example, a 45-year-old female interviewee shared that she had suffered eight miscarriages. Unable to find a solution, she visited a Menzil sheikh.

They told me that if I didn’t take the repentance ritual (tövbe), they wouldn’t be able to give me an amulet. So, with my husband’s permission, I took the repentance ritual. The sheikh wrote me an amulet and said: “Tie it to a string and let it hang below your navel. If you don’t lose the baby and it is born healthy, bring a sacrificial animal here as an offering.” (A5)

Meanwhile, the participant continued her medical treatment, and a year later, she became pregnant and safely gave birth to a healthy child. Although she was uncertain whether the doctor or the sheikh had an effect, after the birth of the baby, she took a sheep to the sheikh’s place as a gift.

5.1.2. Fear of Social Exclusion

Participants generally try medical methods first when they believe that modern medicine can cure their illnesses. However, in some psychological or psychiatric cases, some of the participants directly consulted religious healers without resorting to modern medicine at all (A3, A9, E2, E6, I1, I2, I3, I4, I9). Going to religious healers is considered more natural for the participants in Iğdır compared to our participants in other provinces.

It is well known that social stigma has surrounded the fields of psychology and psychiatry since their emergence. When individuals seek treatment from these disciplines, they often face social stigma. It is not desirable to keep such mental problems in hospital records. Many people reported that they would feel embarrassed about seeking help from professionals and believed that others would react negatively or label them if they did so. While the prevalence of this stigma varies across countries, similar patterns have been documented globally from Australia (Barney et al. 2006) to Britain (Mehta et al. 2009) and from China (Yang et al. 2020) to Saudi Arabia (Abolfotouh et al. 2019).

Although attitudes toward seeking help from psychiatrists or psychologists/psychotherapists as well as toward medication and psychotherapy have markedly improved since the 2000s (Angermeyer et al. 2017), WHO World Mental Health surveys across 24 countries indicate that people still worry about stigmatization for visiting mental health treatment centers (Andrade et al. 2014). This type of stigmatization is also common in Türkiye. In particular, males have higher average total scores compared to females regarding internalized stigma (Sarıkoç and Öz 2016).

We also observed the reflections of this situation in our own research sample. Whether it was seeking help from a psychologist or from a religious healer for psychological reasons, in both cases, women were represented at higher rates than men. This is the main reason why we interviewed 21 women compared to only 10 men among our participants. Most of those who sought help from religious healers were women. The answer given by a female participant to the question “Have there been any previous experiences with healers in your family or among those close to you?” is noteworthy: “Our men do not really believe in such things. They find it ridiculous and dismiss it as women’s affair” (I8).

5.1.3. Limited Access to Medical Services

One of the questions we asked to understand the motivation of our participants to consult a religious healer was “Where does religious healing stand compared to modern medicine?” It appears that the younger generation is more open-minded when it comes to seeking treatment for psychological illnesses and tends to turn more readily to modern medicine. However, before the 2000s, particularly in Eastern Anatolia, this awareness had not yet taken root. As one participant explained, “Of course, these (religious healing and modern medicine) are different. Back then, psychiatry simply did not exist—it was not available in Iğdır. Every scared person was taken to a mullah. But then it (modern medicine) became more widespread, and people became more conscious” (I9). Another participant said,

At first, of course, I think it’s important to go to the doctor. In the past, there wasn’t much opportunity to see doctors, so people would go straight to a mullah or hodja. But now there are more opportunities to see doctors. I recommend going to the doctor first, getting tests done, and checking for any deficiencies in the body—vitamins, minerals, whatever it may be. But at the same time, I also go to a mullah to get checked. (I3)

As these responses show, participants noted that improved access to modern medicine has increased awareness of psychology and psychiatry-related issues.

5.1.4. Mistrust of Modern Medicine in Psychology

Although most of the participants we interviewed had previously received medical support to solve the problems they faced, it is noteworthy that there are also individuals who do not prefer to receive medical support. These participants shared a common belief that their issues did not have a medical basis and therefore needed to be resolved through alternative means. As one participant put it, “I could have pursued treatments like seeing a psychologist, but my problem was not a medical issue” (A9). Another explained,

No, I never thought of going to a doctor. Later on, I wondered if seeing a psychologist would have been helpful, but I was not sure. Because a psychologist cannot recite the Qur’an over me. What healed me was the prayers recited by the hodjas. A psychologist would have given me medication, but I do not think that would have worked. (E2)

It is noteworthy that even one of our participants, who works as a head nurse in a hospital, does not trust modern medicine when it comes to psychological issues.

As a healthcare worker and a nurse, honestly, I didn’t seek out treatment with medication or see a doctor. Medication-based treatment only goes so far. Since I am a healthcare worker, I think medication just keeps people occupied in an empty way. I mean, what can I expect from antidepressants? I don’t think they actually treat people. (I1)

5.1.5. Desperation

When examining the reasons for turning to religious healers, psychological ailments stand out prominently. These include unexplained fears, seeing unusual beings, feeling followed, and other psychological problems. Some participants also reported more tangible cases, such as fainting, eye infections, incessant crying of children, and headaches. In addition to those who visit religious healers to get married or have children, there are also individuals who go for themselves or on behalf of their relatives, friends, or even their livestock and pets.

The initial tendency of participants when facing problems is generally to believe that the issues will resolve on their own over time. However, when the problems worsen or become chronic, they begin to seek solutions. Due to low social acceptance, psychologists are rarely the first choice. Untreatable problems eventually lead individuals to both modern medicine and alternative treatment methods. Even people who do not believe in such practices state that they end up visiting healers out of necessity: “People do it when they are in a tough spot” (E1); “If I had benefited from the doctor, I would not have gone to the healer” (E3); “Actually, I was against these kinds of things. But we were desperate to solve our problem” (A4).

Some participants stated that although they were usually skeptical of such practices, they were forced to turn to healers when they could not find solutions to their own problems. After seeing positive results, they began to believe in the healing practices. For example, one participant, who introduced herself as a rational person and emphasized it several times, explained how she gradually came to believe in healing practices,

Even though I’m an extremely rational person, I was dealing with some spiritual problems. I didn’t feel well. I got help from a psychologist, and I also benefitted from my grandfather’s spiritual healing practices like reciting prayers and measuring the heart (yürek ölçme). When I was studying theology, I never would have believed in irrational things like this. I used to try to explain everything using the Qur’an or science. But now, I don’t think that way anymore. I experienced things through my grandfather’s reciting that I couldn’t explain rationally. When you think about it, it doesn’t make sense, but it happens. (E11)

In summary, even if people act rationally in their daily lives, the state of helplessness leads them to such experiences.

5.1.6. Escaping from Problems: Displacement

Defense mechanisms are behaviors that people develop to avoid thoughts, people, or events that make them feel uncomfortable. Dozens of different defense mechanisms have been identified, with some being more commonly used than others. The most common ones include denial, repression, projection, displacement, regression, rationalization, sublimation, reaction formation, intellectualization, and compartmentalization. In the interviews we conducted, we observed that some of these defense mechanisms were frequently employed. In particular, denial, repression, projection, and displacement stood out as significant motivational factors for seeking out religious healers. Denial is an outright refusal to admit or recognize that something has occurred or is currently occurring. Repression works by pushing distressing information out of conscious awareness. Projection involves attributing one’s own unacceptable qualities or feelings to other people. Displacement is taking out frustrations, feelings, and impulses on people or objects that are less threatening.

In psychological counseling and therapy processes, the source of the problems experienced by the client is often examined based on the individual’s internal psychological processes, cognitive structures, and emotional dynamics. In contrast, religious healers attribute the root of these problems to external spiritual beings, offering people a significant sense of relief.

When I have my problems checked by these healers, it makes me feel better. These mullahs and healers help me solve my problems. If I had gone to a psychologist because of my issues, the psychologist would have called me crazy, prescribed medication, and said I was schizophrenic. What good would that have done? I wouldn’t have gotten better because they would have dismissed it as just a fantasy. (I3)

A frequent explanation participants gave for their problems was that they were possessed by a jinn. In this way, the source of the problem is attributed to external entities rather than to the individual, allowing them to maintain their self-esteem. One participant who attempted suicide because of psychological issues said that the religious healer found three jinn in her and removed them (A3). In this way, an otherwise socially unacceptable behavior like suicide is attributed to these external beings. Another male participant who couldn’t find a cure for his son’s frequent fainting spells at school eventually came to believe that his son was possessed by a jinn.

I took my son to doctors in places like Ankara. They ran every possible test, but nothing was found. Finally, I took him to a psychiatrist who said something in medical jargon that I didn’t understand. So, I asked the doctor if my son might have a jinn. The doctor looked at me and said, “We don’t believe in such things.” I thought to myself that this doctor must be an unbeliever. But there’s a surah in the Qur’an called “al-Jinn” and whoever denies one letter of the Qur’an denies all of it and becomes an atheist. So, I took my son and left immediately. Later, I took him to a respected hodja (seyda) I knew here. The seyda recited something over my son and blew onto his mouth. After that day, my son gradually started to get better. (A1)

One of the reasons people turn to healers is the issue of disapproved romantic relationships between males and females. For example, individuals who believe that their relatives have been deceived by the other party consult religious healers. When they learn from the healers that a spell has been cast on them, they believe that the source of the disapproved relationship has been found. The solution is again in the hands of the healer; by breaking the spell, it is aimed to save the relative. Thus, the problem is attributed not to the person themselves but to a third entity, such as a spell.

My brother had a girlfriend whom our family did not approve of. He could never give her up. The relationship had become an irrational obsession. We wondered why he couldn’t give it up, so we went to a religious healer. The healer put some water in a bowl, recited something, and then said a spell had been cast on my brother. He said he would break the spell and my brother would give up that relationship. Very shortly after, my brother spontaneously gave up on that person and married someone else who was approved by our family. We had experienced something quite strange like this. (I7)

Spells also break up happy marriages. For instance, a 55-year-old male participant (E10) who was on the verge of divorce shared that his wife had left home with children. The participant, who normally does not believe in religious healers, visited one with his friend’s suggestion to find a solution to save his marriage. There, he learned that the source of the family problems leading to divorce was “a spell” and that the spell had been cast by his eldest daughter. Although the healer identified the problem as being caused by a spell, he could not resolve it. According to the participant, the healer’s knowledge was not sufficient to break the spell. Attributing all problems that could lead to divorce to a spell seemed to bring some relief.

Sometimes, the cause of the problem is considered to be the “evil eye.” A female participant (E4), who could not find a solution to her little daughter’s constant crying, learned that the cause was the evil eye cast by someone who had looked at the child with impure eyes while in a state of ritual impurity. Another participant (E5) was advised by a friend—after sharing her troubles—to visit a healer because “it was either a spell, a haunting spirit (jinn), or the evil eye” affecting her. The healer diagnosed her with both a haunting spirit (jinn) and the evil eye and began treatment. When problems are attributed to the evil eye, modern medicine inevitably appears to be helpless: “The doctor doesn’t accept the evil eye, so how could he treat it? He just gives medicine and sends you away” (I4); “Of course, Allah is the one who grants healing, but for some illnesses you have to see a doctor. But what can a doctor do about a spell or the evil eye? They haven’t studied this knowledge” (I5); “Of course, I recommend (visiting a religious healer) because there are some things that doctors just cannot see such as the evil eye. Doctors don’t acknowledge the existence of the evil eye, so they’re unable to treat it. For the evil eye, only a mullah can prescribe something” (I8).

5.2. Religious Experience

5.2.1. Identifying the Problem

For all our participants, there are three elements at the source of the problems: evil eye, jinn, and black magic. These issues might show up alone, in pairs, or even all together in the same person. One striking aspect was that regardless of the problem, the healer would always identify it during the first session. No participant ever received an answer like, “There is nothing wrong with you” or “I couldn’t find the source of your problem.” Even though the treatment processes were sometimes prolonged, all diagnoses were made in the first session.

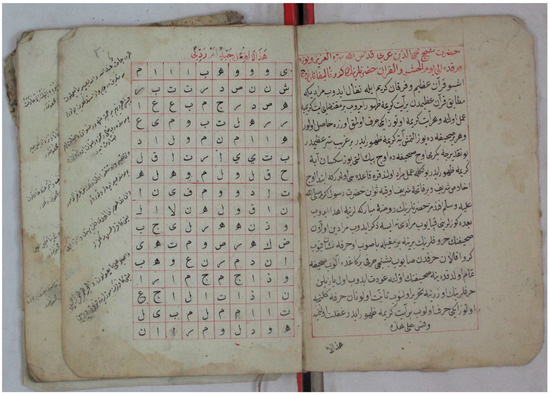

In the identification of problems or the personalized advice provided to individuals, two main methods generally stand out. The first is interpreting the situation by opening the Qur’an, and the second is interpreting by gazing into water. The practice of interpreting by opening the Qur’an has been widely used from Ottoman times to the present day in Turkish and Persian cultures. There are books called falname (fortune-telling/divination) that explain how this practice is carried out. These texts, written in either verse or prose in Arabic, Persian, and Turkish, are used to learn about the future, uncover the unknown, and reveal personality traits. Some of them are illustrated and were prepared with particular care, especially to be presented to sultans and statesmen. Although it is unlikely that Ali ibn Abi Talib, Ja‘far al-Sadiq, and Muhyiddin Ibn Arabi actually authored these texts, falnames are generally attributed to them because of their spiritual authority (Uzun 1995).

In the Ottoman falname attributed to Ibn Arabi, which we obtained from the manuscript collection of Ankara University Divinity Faculty (Figure 4), it is explained how to interpret the Qur’an to answer a range of important questions—from the gender of an unborn child to whether a prospective spouse is suitable. In the page we shared, the aim is to determine whether an intended action is good or bad. The person closes his eyes, expresses his wish, and places his index finger randomly on a spot in the chart on the left. He then records the first letter that appears and every fifth letter after it, reading them aloud. These letters will point to one of the Qur’anic verses listed on the left side of the chart. Based on the meaning of the identified verse, the conclusion is drawn as to whether the action in question is good or bad.

Figure 4.

Example of a falname book (divination) attributed to Ibn Arabi (1165–1240) (Ibn Arabi n.d.).

The tradition of seeking guidance by opening the Qur’an was found to be commonly practiced among Ja‘fari participants (I1, I3, I9, I10). For example, a female participant from Iğdır who works as a nurse found benefit from this method during her job search through a mullah she consulted.

Before starting this job, I had made an agreement with another place and was also waiting to hear from where I work now. (Mullah) C. told me, “Wait until Wednesday. They will call you from the place you want.” I waited somewhat hopelessly. Then Wednesday came. Just as C. said, they called me and invited me. Now, I hold a very good position here as the head nurse. (I1)

Our participant, who realized that Mullah C. was helpful regarding work matters, began to consult him at every critical stage of her life, almost like a life coach whom she turns to for advice in all areas.

For example, I currently have a boyfriend. I consult Uncle C. about him. I say, “If there’s a bad side to him that I can’t see, please tell me. If I’m mistaken, you don’t make mistakes.” Even with decisions that my family doesn’t know about, I ask him first, then take action. After that, I inform my family. (I1)

But how does Mullah C. make these decisions? It is understood that he refers to Qur’anic divination here. When the participant consults him about her decisions, she asks him to open the Qur’an for her: “One day, I had something on my mind. I didn’t tell anyone. A long time passed. I said to C., ‘Can you open the book for me?’ He did, and said, ‘It is good. Do it.’ I really did it, and it worked out” (I1).

One of our participants, whose 18-year-old son began experiencing fear, went to a healer and had the Qur’an opened for her son, learning that two of his ex-girlfriends had cast spells on him (I3). Another participant also has the Qur’an opened before making critical decisions.

When I need to make a decision, I always have the mullah open the Qur’an. If he says “no,” then I decide not to do it … When my daughter was about to get married, I had the mullah check (the Qur’an), and he approved. I trusted him and got my daughter married. I have been very pleased. But of course, only Allah knows the future. The mullah opens the book and tells whether the matter is good or not. That’s what’s in the book (Qur’an). The mullah tells it. Think of it like this, let’s say you are unsure about something, and you ask a friend, “Should I do this or not?” She gives you her opinion. The mullah does the same but by opening the book. The only difference is, before opening the book, you have to follow what the mullah’s divination says. If the mullah says, “This is not good, don’t do it,” then you must not attempt it. If you want to follow what he says, you have to get a divination from the book. (I10)

Another method used to identify the source of the problem is scrying. In this practice, the religious healer connects with his jinn through the water to understand the person’s problem and offer a solution.

The mullah put a bowl of water in front of me. He looked into the water and asked, “Do you see anything here?” I said “No, I do not see anything.” Then he said, “You poured hot water in the kitchen without reciting the Basmalah, and at that moment you burned the child of one of them (jinn).” … The mullah recited (verses) and blew onto the water, then looked to the side and said, “Will you go, or should I send you? Will you go, or should I send you?” It was like he was talking to someone standing next to him. In the end, he turned to me and said, “I burned it. Otherwise, it wouldn’t leave.” (I3)

Apart from these, there are many other fortune-telling practices—like using coffee grounds or tarot cards—but these types are not used in religious healing.

5.2.2. Treatment Processes

All participants, except for two, stated that they were satisfied with their experience and even recommended it to others. Two male participants who expressed dissatisfaction with the healers did not see any positive results from the treatments (A4, E8). One male participant (E8), whose wife was crying for no apparent reason and experienced some psychological problems, initially took her to a psychiatrist. Although the participant did not believe in religious healing, he eventually took her to a healer at the insistence of the family. The healer claimed that the source of his wife’s problems was the jinn, explaining that she had poured water on a fire at night, which had caused the problem. He recited over her and had her drink water that had been recited over. However, the woman did not see any benefit. Over time, as his wife recovered, the participant believed that the healer had no role in her recovery.

Among the people we interviewed, there are those who think that they will eventually find healing, even though they have not yet seen the expected benefit (E4, I7): “I have been here for 5 months but there has been no progress. Although I did what they said, the problem in my child hasn’t gone away. I don’t know if it will help from now on, but I want to believe” (I7).

The treatments performed can generally be grouped under the following categories: reciting Qur’an and blowing onto the head, face, or mouth; drinking, applying, or bathing with blessed water; using blessed salt or soap; wearing, using, or burning amulets; burning peganum harmala herbs; and spitting into the mouth.

One of the most common practices in religious healing is the healer reciting verses related to the treatment and blowing his breath onto the person (A1, A2, A3, A9, E6, E7, I2). This blowing can be so subtle that it is barely felt, or it can be strong enough to be directly sensed. Sometimes, after reciting the verses, the healer blows onto a glass of water placed in front of him and asks the person seeking treatment to drink it (A3, E8, E9). In some cases, this water is applied to the body (I5) or used for bathing (A5, A8). Reciting Qur’anic verses and blowing, along with drinking blessed water, are often used together. Although less common, practices such as blessed bread (A10), blessed salt (E6), and blessed soap for bathing (I6) can also be observed.

He recited the surah al-Hashr/(59) over the water and handed it to me, telling me to drink it. I drank the water. Then he came over to me while I was seated and leaned over my head, blowing directly on me. You might not believe this, but at that moment, the entire area was suddenly filled with light. I kept blinking, thinking I must be imagining things, but it wasn’t a dream—everything was truly illuminated. It was such an extraordinary experience. (A2)

The healer recited verses over the water, blew on it, and told me that he was sending benevolent spiritual entities to be with me. He instructed me to drink the water he had recited over. (A3)

Among those we interviewed, the most frequently used healing practice appears to be the writing of amulets (A2, A3, A5, A6, A7, A8, A10, E1, E2, E3, E4, E5, E9, I3, I5, I6, I8, I9, I10). In general, these amulets are meant to be worn on the body. They are usually tied around the neck with a string or pinned to the upper piece of underclothes.

A relative of mine had passed away. I loved her very much. After her death, I couldn’t bear any sadness. Whenever I heard something about condolences or death, I would faint. I had never had such a problem before my relative passed away. Eventually, my family took me to a healer. The healer wrote some prayers for me, and after that, I started to feel better. I had been to a doctor too, and used many psychiatric medications, but those only made me sleepy and worsened my state of mind. The healer wrote an amulet for me, and I still carry it. I feel so much better now. (E3)

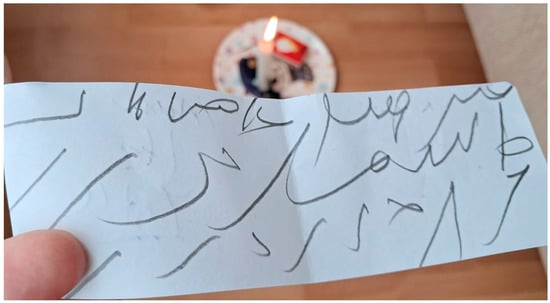

Religious healers write some verses, prayers, or special expressions on a piece of paper, folding it into a triangular shape. They usually seal it in a leather pouch, sewing it shut and instructing the person never to open it (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Examples of amulets.

Although the general practice is for these amulets to be carried on the person, in some cases, it has been observed that they are used for bathing (A8) or burned (A3, I8), or the smoke is inhaled (E5).

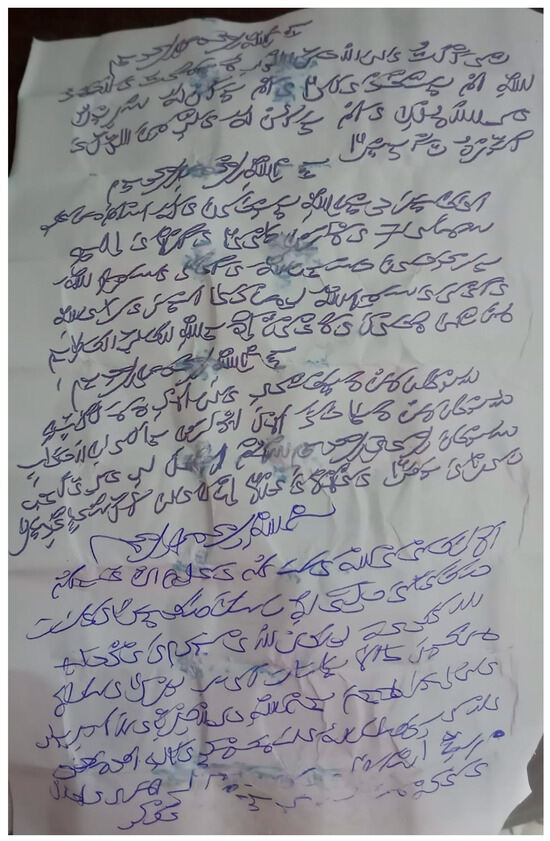

Although most amulets contain verses and prayers, it is sometimes observed that they also contain nonsensical writings. For example, in the writing prepared to be burned in candle flame (Figure 6), no meaningful expression could be identified. Sometimes, amulets begin with a known verse like the Basmalah, but the rest is unreadable (Figure 7). Making the amulet unreadable adds an air of mystery to it. In this way, the deformation or imitation of Qur’anic letters is used to create a sense of sacredness.

Figure 6.

An amulet prepared for burning.

Figure 7.

Example of amulet writing.

In addition to burning amulets for healing purposes, it has been observed that burning harmal seeds (peganum harmala, known locally as üzerlik) is also a common practice among Ja‘fari participants (Figure 8). According to this belief, when peganum harmala is burned while reciting salawat, i.e., invocations of peace and blessings upon the Prophet Muhammad, and prayers, it protects the household and family members from the evil eye (E6, I8, I9). One participant, who has two children with psychological problems, frequently uses this method for healing: “When you burn üzerlik, you’re protected from all kinds of troubles. You absolutely have to burn it with salawat and prayers for it to be effective. The secret lies in the salawat” (I9).

Figure 8.

Burning of peganum harmala herbs for spiritual healing.

Sometimes, those seeking treatment are also given saffron-infused water for bathing (Figure 9): “The mullah gave special saffron recited water and said the whole family should bathe with it” (I7).

Figure 9.

Water mixed with saffron for healing.

More than half of our participants paid a fee to the healers they visited. For some, this fee was predetermined, while for others, it was given voluntarily as they wished. Practices such as writing amulets or providing saffron water were perceived by individuals as justifying the payment of a fee.

6. Conclusions

This study is based on qualitative field research conducted between January and May 2025 in three provinces of Eastern Anatolia in Türkiye—Ağrı, Erzurum, and Iğdır. Through in-depth interviews with 31 participants and field observations, we examined the ongoing significance of religious healing practices in contemporary Türkiye.

The healing practices we encountered in our fieldwork generally followed certain patterns. Specifically, the diagnosis of problems was often made through divination with the Qur’an or through spiritual communication with the healer’s jinn by gazing into a bowl of water. Treatment methods typically included practices such as reciting and blowing Qur’anic verses onto the head, face, or mouth; using or drinking blessed water; applying or burning amulets; using blessed salt or soap; burning the peganum harmala herbs; and, in some cases, spitting into the mouth.

Although not endorsed by formal Islamic theology or modern medicine, the tradition of religious healing remains both widespread and resilient. The strong interest shown by both young and older participants suggests that this tradition is actively being transmitted across generations. Even devout individuals continue to turn to religious healing, despite its marginalization within official Islamic discourse. Notably, the ongoing vitality of these practices—which exist in a liminal space between faith and science—demonstrates the enduring strength of traditional frameworks in resisting to modern paradigms.

While participants often sought professional medical treatment for physical or psychological concerns, many also turned to religious healers for complementary support—drawn by the emotional warmth, spiritual reassurance, and interpersonal connection. Given these dynamics, individuals do not necessarily abandon biomedical approaches, but instead integrate them with spiritual remedies that reflect their cultural and religious worldview.

One of the most significant motivations driving individuals toward healers is the profound sense of helplessness they experience. As their problems intensify or become chronic, people increasingly seek solutions. Given the social stigma attached to mental health services, psychologists are rarely the first point of contact. When issues persist unresolved, many turn to both modern medicine and alternative spiritual methods. Even skeptics acknowledged that, in moments of desperation, they eventually sought out religious healers.

One of the key findings of this study is that turning to religious healers often functions as a psychological coping mechanism, allowing individuals to attribute their problems to external sources such as the evil eye, jinn, or black magic—thereby alleviating personal guilt or responsibility. This attribution enables a sense of coherence and emotional relief, especially when biomedical explanations fail to provide satisfactory answers.

We also found that participants often approached healers with an underlying assumption of their effectiveness. Statements such as “you must believe in order for it to work” reflected this internal conviction. Moreover, the religious titles of healers—such as mullah, sayyid, or seyda—and their use of religious objects and terminology contributed to the perception of these practices as legitimate and sacred. These dynamics illustrate how religion and culture are deeply intertwined in shaping individual meaning-making within our research context.

In our research, we identified significant regional and sectarian variation in healing practices. In Iğdır, where all participants identified as Shiite Muslims, trust in healers stemmed from the belief that they were sayyids—descendants of the Prophet Muhammad—or from the awareness that these healers had received religious training in Iran. In contrast, participants from Sunni-majority provinces like Ağrı and Erzurum tended to trust healers based on personal connections, affiliation with Sufi orders, or shared belief in their prophetic lineage.

In conclusion, this research does not view religious healing as a mere remnant of folkloric belief or a marginal religious practice. Rather, it should be seen as a nexus of cultural continuity, collective memory, and personal meaning-making. In seeking healing, individuals also seek to reconstruct a sense of trust, belonging, and harmony within a world marked by rapid social and cultural transformation. In light of these findings, this study contributes meaningfully to the sociology of religion, cultural anthropology, and broader academic discussions on religion and modernity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.B. and S.Y.; Methodology, F.B. and S.Y.; Validation, S.Y.; Formal analysis, F.B. and S.Y.; Investigation, F.B. and S.Y.; Resources, F.B. and S.Y.; Data curation, F.B. and S.Y.; Writing—original draft, F.B. and S.Y.; Writing—review & editing, F.B. and S.Y.; Visualization, S.Y.; Supervision, S.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Ankara University (protocol code 282 and date of approval 04/10/2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abolfotouh, Mostafa A., Adel F. Almutairi, Zainab Almutairi, Mahmoud Salam, Anwar Alhashem, Abdallah A. Adlan, and Omar Modayfer. 2019. Attitudes toward mental illness, mentally ill persons, and help-seeking among the Saudi public and sociodemographic correlates. Psychology Research and Behavior Management 12: 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ak, Muammer. 2018. Kültürel kimlik ve toplumsal hafıza mekânları olarak ziyaret yerlerï. Turkish Studies 13: 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, Osman. 1976. Şifa Tasları. Türk Etnografya Dergisi 65: 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Anadolu Agency. 2025. Faldan vergi, astroloji haritasından denetim çıktı. Available online: https://www.aa.com.tr/tr/ekonomi/faldan-vergi-astroloji-haritasindan-denetim-cikti/3510984 (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Andrade, Chittaranjan, and Rajiv Radhakrishnan. 2009. Prayer and healing: A medical and scientific perspective on randomized controlled trials. Indian Journal of Psychiatry 51: 247–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, L. H., J. Alonso, Z. Mneimneh, J. E. Wells, A. Al-Hamzawi, G. Borges, E. Bromet, R. Bruffaerts, G. de Girolamo, R. de Graaf, and et al. 2014. Barriers to mental health treatment: Results from the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Psychological Medicine 44: 1303–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angermeyer, Matthias C, van der Sandra Auwera, Mauro G. Carta, and Georg Schomerus. 2017. Public attitudes towards psychiatry and psychiatric treatment at the beginning of the 21st century: A systematic review and meta-analysis of population surveys. World Psychiatry 16: 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balamir, Figen. 2023. Türkiye’de Şii olmak: Etnografik bir araştırma. Ankara: Gazi Kitabevi. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, Lisa J., Kathleen Margeret Griffiths, Anthony Jorm, and Helen Christensen. 2006. Stigma about depression and its impact on help-seeking intentions. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 40: 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, John W. 2016. Nitel araştırma yöntemleri: Beş yaklaşıma göre nitel araştırma ve araştırma deseni, 3rd ed. Translated by Mesut Bütün, and Selçuk Beşir Demir. Ankara: Siyasal Kitabevi. [Google Scholar]

- Çarkoğlu, Ali, and Binnaz Toprak. 2000. Türkiye’de din, toplum ve siyaset. Istanbul: TESEV. [Google Scholar]

- Çarkoğlu, Ali, and Ersin Kalaycıoğlu. 2009. Türkiye’de dindarlık: Uluslararası bir karşılaştırma. Istanbul: Sabancı Üniversitesi. [Google Scholar]

- Çelebi, İlyas. 2020. Muska. In Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslam Ansiklopedisi. Istanbul: TDV Islamic Research Center, vol. 31, pp. 267–69. Available online: https://islamansiklopedisi.org.tr/muska#2-kelam (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Demirci, Kürşat. 2020. Muska. In Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslam Ansiklopedisi. Istanbul: TDV Islamic Research Center, vol. 31, pp. 265–67. Available online: https://islamansiklopedisi.org.tr/muska#1 (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Demirdağ, Muhammed Emin. 2021. Sosyal medyada dayanışma örneği olarak “dua acenteliği”. Kadim Akademi 5: 50–69. Available online: https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/kadimsbd/issue/67315/1027070 (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Dole, Christopher. 2015. Seküler yaşam ve şifacılık: Modern Türkiye’de kayıp ve adanmışlık. Translated by Barış Cezar. Istanbul: Metis Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- DuBois, Thomas David. 2015. Chinese folk festivals. In Routledge Handbook of Religions in Asia. Edited by Bryan S. Turner and Oscar Salemink. London: Routledge, pp. 209–18. [Google Scholar]

- Dupaigne, Bernard. 2013. Shamans in Afghanistan? In Shamanism and Islam: Sufism, Healing Rituals and Spirits in the Muslim World. Edited by Thierry Zarcone and Angela Hobart. London: I. B. Tauris, pp. 115–30. [Google Scholar]

- Endres, David J. 2016. What medicine could not cure: Faith healings at the Shrine of Our Lady of Consolation, Carey, Ohio. U.S. Catholic Historian 34: 25–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkal, Mehmet Mustafa. 2024. Estonların geleneksel inanışları üzerine. Ankara Üniversitesi İlahiyat Fakültesi Dergisi 65: 903–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geertz, Clifford. 1973. Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Günay, Ünver. 2001. Din sosyolojisi. Istanbul: İnsan Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Günay, Ünver. 2003. Türk halk dindarlığının önemli çekim merkezleri olarak dini ziyaret yerleri. Erciyes Üniversitesi SBE Dergisi 1: 5–36. [Google Scholar]