The Jamāl Gaṛhī Monastery in Gandhāra: An Examination of Buddhist Sectarian Identity Through Textual and Archaeological Evidence

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Jamāl Gaṛhī Monastery Site

1.2. The Gandhāra Region’s Historical Buddhist Context as It Pertains to the Jamāl Gaṛhī Monastery Site

1.3. Objectives of the Study

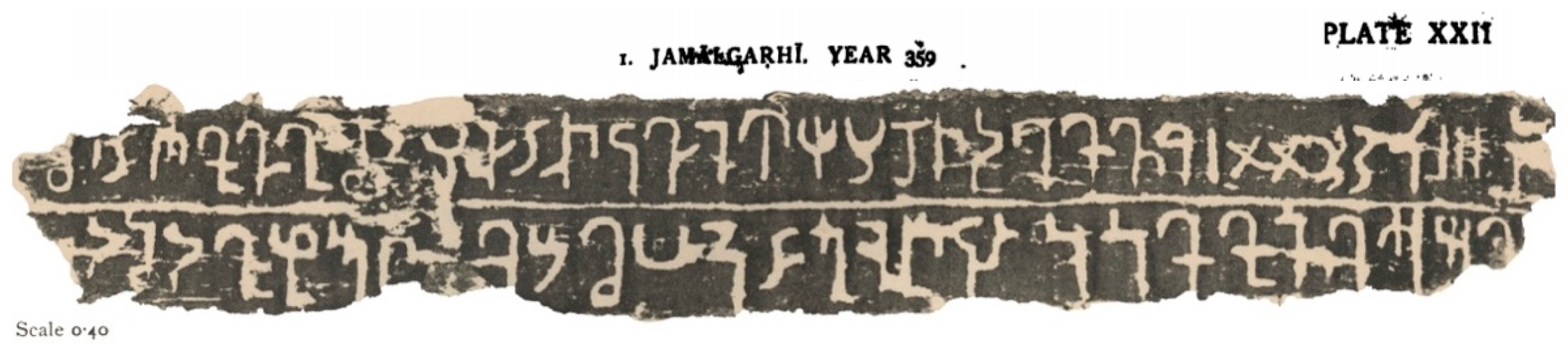

2. The ‘Sectarian Affiliation’ and Chronology Reconstruction of the Jamāl Gaṛhī Monastery Based on Epigraphical Data

| Text: | |

| 1 | saṃ 1 1 1 100 20 20 10 4 4 1 Aśpaï [u] sa paḍhaṃmaṃmi ṣa- |

| vaena Poda [ena sa] haehi pida [pu] [trehi*] | |

| 2 | [U] ḍiliakehi i [ś] e rañe preṭhavide dhamaüte [oke] parigrahe sar- |

| vasa [pana*] | |

In the year 359, on the first day of Aśvayuj, Podaa, together with his companions, fathers, and sons—the Uḍiliakas—constructed [this] for acceptance by the Dharmaguptakas in honor of all beings.[Im Jahre 359, am ersten des Aśvayuj, hat Podaa zusammen mit seinen Genossen, Vätern und Söhnen, den Uḍiliakas, …… errichtet zur Entgegennahme durch die Dharmaguptīyas, zu Ehren aller Wesen.]

The inscription […] shows plainly, characters of the Kushāṇa period [c. 30–c. 375 CE]. Its chronological interest is evident; for placed as it was and scratched into a stone of no great hardness, it could not have retained its legibility if it had lain exposed for a long series of years […] It seems, therefore, probable that the period when the Stūpa court was finally abandoned is not separated by a very great interval from the time when these characters were scratched in, perhaps by some pious visitor.44

3. The Architectural Remains of the Stūpa Courtyard at Jamāl Gaṛhī in Connection with Vinaya Literature

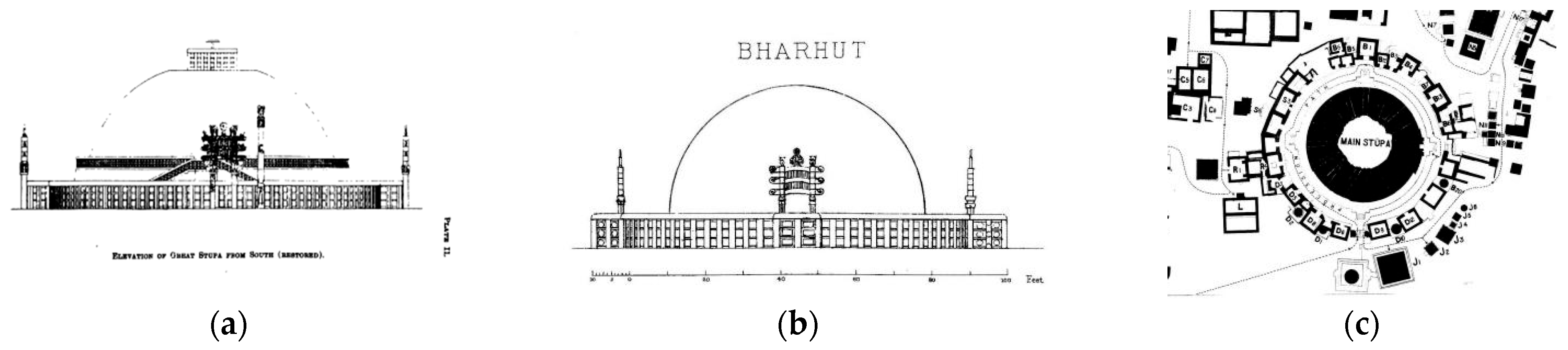

3.1. Stūpa Formation

As for the method of constructing a stūpa: railings [should] surround all four sides of the square foundation/platform. Two domes (*aṇḍa) [should] be constructed, one on top of the other (on the foundation). [Atop of them], a square tusk-like (construction; 方牙) (*harmikā) [should] protrude in the four directions. Canopies (槃蓋), long banners (長表), and discs (chattra; 輪相) [should] be attached atop.

作塔法者, 下基四方周匝欄楯, 圓起二重, 方牙四出, 上施槃蓋長表輪相.52

The Buddha says, ‘Construct it as square, round, or octagonal’

佛言: “四方作, 若圓, 若八角作”.53

3.2. Layout and Orientation of the Stūpa Courtyard

Vinaya and sāstra texts distinguish between ‘flat bounded areas’ “chang 場” and ‘raised platforms’ “tan 壇”. Unsurprisingly, all the countries of the Western kingdoms (西天諸國, i.e., India) have established separate rituals, whereas here (the Chinese) have never done so. [……] The name “raised platform” (壇; i.e., ‘altar’) was established during the Buddha’s time! 律論所顯, “場”, “壇” 兩別, 西天諸國皆立別儀, 此土中原素未行事, 不足怪也. [……] “壇” 之立名在佛世矣!61

Concerning matters of stūpas (塔事; stūpavastupratisaṃ-yuktaṃ): When a saṃghārāma (monastery) is built, one should choose (lit. “plan”) a suitable place, in advance, for the stūpa. The stūpa should not be located to the south or west (of the monastery). It should be located to the east, (or) located to the north. The area of the (monastic Community) is not allowed to transgress the area of the Buddha (i.e., stūpa). The area of the Buddha (i.e., stūpa) is not allowed to transgress the area of the Community. If the stūpa is located near a cemetery and if dogs, which feed on leftovers, bring them and dirty the area, fences should be made. Cells of monks should be built to the west or south of (the stūpa). Used water of the area of the Community should not flow into the area of the Buddha (i.e., stūpa). Used water from the area of the Buddha (i.e., stūpa) is allowed to flow into the area of the Community. The stūpa should be built on a high place and at a vantage point.

塔事者, 起僧伽藍時, 先預度好地, 作塔處. 塔不得在南, 不得在西, 應在東, 應在北, 不得僧地侵佛地. 佛地不得侵僧地. 若塔近死屍林, 若狗食殘持來污地, 應作垣牆. 應在西若南作僧坊, 不得使僧地水流入佛地, 佛地水流入僧地. 塔應在高顯處作.62

The Mohesengqi lü reflects the Mahāsāṃghika school’s (Ch. Dazhong bu 大衆部) strong emphasis on the spatial positioning of stūpas. Whenever a monastic community constructs a new monastery, it is required to reserve the most desirable plot of land specifically for the stūpa courtyard, which should be situated in the northern and eastern sections of the site. The term ‘stūpa courtyard’ indicates not only the prominence of the stūpa’s location within the monastery but also its architectural separation as a dedicated space. The Mohesengqi lü further stipulates that the grounds of the stūpa must not overlap with the monks’ residential quarters, and that the stūpa should be enclosed by a wall or fence to protect it from contact with impure objects.

The Mahāsāṃghika-Vinaya says: Concerning matters of stūpas (塔事; stūpavastupratisaṃ-yuktaṃ): When a saṃghārāma (monastery) is built, one should choose (lit. “plan”) a suitable place for a stūpa. A stūpa should not be located to the south or west (of the monastery). It should be located to the east, (or) north. (In “the middle country” [中國, madhyadeśa, i.e., ‘central north India’],69 monastery entrances typically face east, so stūpas and monastery buildings are oriented accordingly. Even kitchens and toilets are in the southwest due to the prevalence of northeasterly winds there.70 In the ‘divine continent/holy land’ [神州; i.e., China], the west is considered the primary direction [正陽],71 so [monastery and stūpa constructions] do not need to follow Indian customs).

《僧祇》: 塔事者. 起僧伽藍時, 先規度好地, 作塔處. 其塔不得在南, 在西. 應在東, 在北 (中國伽藍門皆東向故. 佛塔廟宇皆向東開. 乃至厨廁亦在西南. 由彼國東北風多故. 神州尚西爲正陽. 不必依中土法也).72

The propositions originally held in common by the Dharmaguptakas are: (1) Although the Buddha is included in the Saṅgha, giving separate gifts to the Buddha procures great fruition (merit), but giving to the Saṅgha [does not]. The act of making offerings to a stūpa procures great merit; (2) The deliverance obtained by the Buddha [vehicle] and that obtained by the [other] two vehicles is the same, but the noble paths [of each vehicle] are different; (3) Heretics cannot obtain the five supernatural powers; (4) The whole body of the arhat is pure (anāsrava 無漏). Most of the other teachings [of this school] are the same as those of the Mahāsāṃghikas (大眾部).

其法藏部本宗同義. 謂佛雖在僧中所攝, 然別施佛果大, 非僧. 於窣堵波興供養業獲廣大果. 佛與二乘解脱雖一, 而聖道異. 無諸外道能得五通. 阿羅漢身皆是無漏. 余義多同大眾部執.73

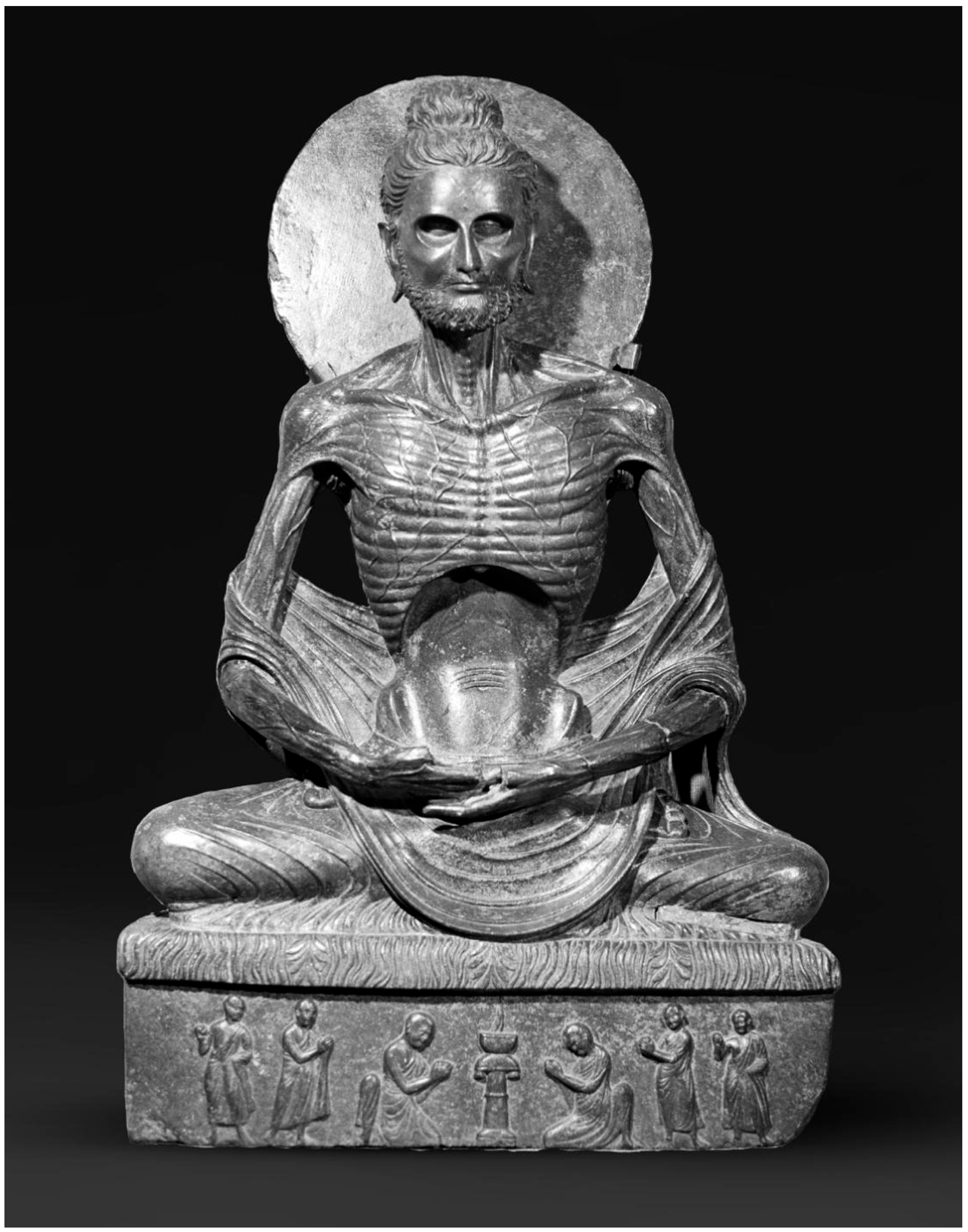

4. Ideas Embodied in the Iconography of the “Fasting Buddha” Images

Then the Bodhisattva recalled, “Long ago, when I was sitting under a jambu tree by a field belonging to my father the king, I eliminated the desire for sensual pleasure, as well as all other evil and unwholesome states; with applied thought, reflection, joy, happiness, and one-pointedness of mind, I attained mastery of the first dhyāna.”The Bodhisattva then contemplated, “Could this path bring an end to the origins of suffering?” It occurred to him, “Indeed, this path will bring an end to the origins of suffering.” Thereupon, motivated by this realization, the Bodhisattva undertook cultivation with great effort. Through this path, he brought an end to the origins of suffering.Then the Bodhisattva wondered, “Is it possible to attain happiness through desire or unwholesome states?” It occurred to him, “No, it is not possible to attain happiness through desire or unwholesome states.”He further considered, “Is it possible to attain happiness by cultivating desirelessness and abandoning unwholesome states?”It occurred to him, “Whether or not that is possible, I will not obtain happiness through mortification of my body. I shall eat a little rice porridge to regain my strength.”爾時菩薩自念: “昔在父王田上坐閻浮樹下, 除去欲心惡不善法, 有覺有觀喜樂一心, 遊戲初禪.”時菩薩復作是念: “頗有如此道可從得盡苦原耶?” 復作是念: “如此道能盡苦原.” 時菩薩即以精進力修習此智, 從此道得盡苦原.時菩薩復作是念: “頗因欲不善法得樂法不?” 復作是念: “不由欲不善法得樂法.”復作是念: “頗有習無欲捨不善法得樂法耶?然我不由此自苦身得樂法, 我今寧可食少飯麨得充氣力耶?”75

The Bodhisattva’s damaged forearms originally met in dhyāna; he is naked to the waist where a twisted roll of textile forms a girdle…His head, unevenly sliced at right angles to the slab, is bearded on one side along the jaw to the chin and still has one deep-set eye, a prominent cheek-bone and horizontal mouth below a moustache…The flat-shouldered torso is ribbed, the top of the rib cage plunging in a deep ‘V’ below the protruding vertebrae. Nippled breasts project slightly, and the waist is indrawn at the navel. The posture is dramatically straight and still, the arms bony. The face of the grass-covered rectangular seat has triangular panels each containing a large, roughly triangular indentation.77

At that time, Sujātā having heard these words, took a vessel from the Bodhisattva’s hand. She entered her house and filled it with fragrant, delicious, sweet food and drinks, along with various cakes, fruits, and stews. The vessel overflowed, and she then knelt before the Bodhisattva, offering it to him.……At that time, the Bodhisattva saw that the brāhmaṇa Deva had developed a heart inclined toward him and was filled with joy. He then said to Deva the brāhmaṇa:“Great Brāhmaṇa! Could you provide me with a small amount of food so that I may sustain my life? Even just a little broth made from lentil beans, soybeans, kidney beans, red beans, or the like—if I eat it, I can maintain my life.”The brāhmaṇa, being narrow-minded, petty in thought, with limited understanding and no expansive vision, nonetheless wished to practice almsgiving. He accepted this request and replied to the Bodhisattva:“Great noble prince! I can indeed provide such food.” Thus, for six years, the brāhmaṇa provided the Bodhisattva daily with the aforementioned food. The Bodhisattva accepted it each day, consuming it in accordance with the teachings of the Dharma to sustain his life. During that time, the Bodhisattva would receive the food with his bare hands, taking only a small portion daily—be it a soup of mung beans or red beans, just enough to preserve life.As a result of this meager sustenance, the Bodhisattva’s body grew emaciated, his breathing became faint, and he appeared as frail as an aged man of eighty or ninety, utterly without strength, his limbs failing to respond. Likewise, his joints and bones became rigid and brittle.By thus reducing his intake of food and drink, and practicing intense asceticism, the Bodhisattva’s skin grew deeply wrinkled. Like a bitter gourd not yet fully ripe, severed from its stem and left in the sun to wither yellow under the heat—its flesh parched, its skin wrinkled, flaking off in patches like dried bone—so too was the Bodhisattva’s skull, appearing no different.Due to his meager intake, the Bodhisattva’s two eyes had sunken deep into their sockets, like water at the bottom of a well from which stars might be seen reflected. Thus, his eyes barely appeared visible.Again, due to eating so little, the Bodhisattva’s ribs protruded widely apart, covered only by skin, resembling the exposed rafters of a cowshed or a goat shed.時善生女聞是語已, 從菩薩手而取瓦器, 入自家中, 滿盛香美甘味飲食, 并及種種餅果羹臛, 溢瓦器中, 即出胡跪, 奉授菩薩.……爾時, 菩薩見彼提婆婆羅門, 心向於菩薩, 生歡喜已, 即告提婆婆羅門言: “大婆羅門!汝能爲我辦少許食, 活我已不? 若小豆臛, 大豆, 菉豆, 赤豆等羹, 而我食之, 持用活命.” 彼婆羅門, 心狹劣故, 少見少知, 無廣大意, 欲行布施, 述可此語, 報菩薩言: “大聖太子! 如是之食, 我能辦之.” 彼婆羅門, 於六年中, 日別如上所須之食, 以供菩薩. 菩薩日日受取此食, 依法而食, 以活身命. 爾時菩薩, 但以手掌日別從受, 隨得少許而食活命, 或小豆臛及赤豆等. 是時菩薩, 受食既少, 隨掌所容, 如上所説, 諸豆汁食, 菩薩如是食彼食已, 身體羸瘦, 喘息甚弱, 如八九十衰朽老公, 全無氣力, 手脚不隨. 如是如是, 菩薩支節連骸亦然. 菩薩如斯減少食飲, 精勤苦行, 身體皮膚, 皆悉皺. 譬如苦瓠, 未好成熟, 割斷其蔕, 置於日中, 被炙萎黃, 其色以熟, 肌枯皮皺, 片片自離, 如枯頭骨. 如是如是, 菩薩髑髏, 猶是無異. 菩薩既以少進食故, 其兩眼睛深遠陷入, 猶井底水, 望見星宿. 如是如是, 菩薩兩眼, 覩之纔現, 亦復如是. 又復菩薩以少食故, 其兩脅肋, 離離相遠, 唯有皮裹, 譬如牛舍, 或復羊舍, 上著椽木.78

It further explains:…A bhikṣu who has eliminated the two extremes [of reality] (除此二邊已) can attain the Middle Way (更有中道), wherein the eyes are illuminated (眼明), wisdom is clarified (智明), and there is eternal tranquility and cessation (永寂休息). Such a one achieves supernatural abilities (成神通), perfect enlightenment (得等覺), and the conduct of a śramaṇa leading to nirvāṇa (成沙門涅槃行).……比丘除此二邊已, 更有中道, 眼明智明永寂休息, 成神通得等覺, 成沙門涅槃行.81

What is called ‘the Middle Way’? (云何名中道) ‘The Middle Way’ is characterized by the following: Eyes illuminated (眼明), cognition supranormal (智明), permanent cessation (永寂休息), achieving supernatural abilities (成神通), perfect enlightenment (得等覺), and the śramaṇa’s conduct toward nirvāṇa (成沙門涅槃行).This is the Noble Eightfold Path (賢聖八正道 āryāṣṭāṅga-mārga):Right View (正見, samyag-dṛṣṭi, correct understanding),Right Action (正業, samyak-karmānta, the righteous behavior of post-learners),Right Speech (正語, samyag-vāc, correct articulation),Right Practice/Intention (正行, samyak-saṃkalpa? proper engagement),Right Livelihood (正命, samyag-ājīva, virtuous means of subsistence),Right Skillful Means (正方便, samyag-vyāyāma appropriate techniques),Right Mindfulness (正念, samyak-smṛti, attentive awareness),Right Concentration (正定, samyak-samādhi, accurate focus and determination).This is called the Middle Way (是謂中道).云何名中道? 眼明智明永寂休息, 成神通得等覺, 成沙門涅槃行, 此賢聖八正道: 正見, 正業, 正語, 正行, 正命, 正方便, 正念, 正定, 是謂中道.82

The chapels, which formed the enclosure, stood on a continuous basement like that of the stupa [sic] itself. This was divided into straight faces of unequal length, according to the size of the chapels above them. Some of these faces were covered with plain stucco; but most of them were ornamented with seated figures of Buddha, alternately Ascetic and Teacher, and smaller standing figures of Buddha between them.

The “Four Contemplations” (四相, i.e., ‘the four contemplations of the truth of suffering’) are distinct. How can they be meditated upon and realized simultaneously? The answer is through the process of “meditative imagination” (想). As the sūtras explain: “By cultivating (修習) the ‘mental image/conception of impermanence’ (無常想), one eradicates all forms of desire.” This conceived (想) “confirmatory vision” (境界) is, namely, “the truth of ‘suffering’” (苦諦 duḥkha). All forms of desire correspond to “the truth of ‘the arising’ of suffering” (集諦 samudaya). The act of eradicating (desire) represents “the truth of the ‘cessation’ of suffering” (滅諦 nirodha). Lastly, the “conception of impermanence” (無常想) aligns with “the truth of ‘the path to liberation’” (道諦 mārga)—the way to liberation. For this reason, although the “Four Truths” (四諦) are distinct, they can be realized simultaneously (一時得見).Furthermore, through critical analysis/reflection (思擇), the process is clarified. As the sūtras state: “Because of the conception/‘mental image’ of impermanence and other contemplations (因無常等想), one carefully reflects on the five aggregates (五陰, pañca-skandha), and thus desire (貪愛) that has not yet arisen will not arise (未生不得生), and desire that has already arisen will cease (已生則滅).” Among these, ‘the five aggregates’ (五陰) represent ‘the truth of suffering’ (苦諦); ‘desire’ corresponds to ‘the truth of the arising of suffering’ (集諦); their ‘non-arising and cessation’ (不生及滅) represent ‘the truth of the cessation of suffering’ (滅諦); and the ‘conception of impermanence’ along with ‘critical reflection’ aligns with ‘the truth of the path’—the path to liberation (道諦). For this reason, one can realize the “Four Noble Truths” (四諦) simultaneously.Moreover, by contemplating transgressions or flaws (由觀失故), the process becomes clearer. As the sūtras state: “In contemplating the basis of the tangling (afflictions), which lead to transgressions (觀結處過失), desire ceases.” The basis of these afflictions (結處) corresponds to ‘the truth of suffering’ (即苦諦); desire (貪愛) aligns with ‘the truth of the arising of suffering’ (即集諦); cessation (滅) represents ‘the truth of the cessation of suffering’ (即滅諦); and the contemplation of these faults or flaws (過失觀) aligns with ‘the truth of the path’ (道諦). For this reason, one can clearly perceive and attain “the Four Noble Truths.”四相不同, 云何一時而得並觀者? 答: 由想故, 經中説: “修習無常想, 拔除一切貪愛.”是想境界, 即是苦諦; 一切貪愛, 即是集諦; 拔除, 即是滅諦; 無常想, 即是道諦; 以是義故, 雖四不同, 一時得見. 復次, 由思擇故, 如經言: “因無常等想, 思擇五陰, 貪愛, 未生不得生, 已生則滅.” 此中五陰, 即是苦諦; 貪愛, 即集諦; 不生及滅, 即是滅諦; 無常等思擇, 即是道諦; 以是義故, 一時得見四諦. 復次, 由觀失故, 如經言: “觀結處過失, 貪愛即滅.” 結處, 即苦諦; 貪愛, 即集諦; 滅, 即滅諦; 過失觀, 即是道諦; 以是義故, 一時見諦. 復次, 由思擇故, 如經言: “因無常等想, 思擇五陰, 貪愛, 未生不得生, 已生則滅.” 此中五陰, 即是苦諦; 貪愛, 即集諦; 不生及滅, 即是滅諦; 無常等思擇, 即是道諦; 以是義故, 一時得見四諦. 復次, 由觀失故, 如經言: “觀結處過失, 貪愛即滅.” 結處, 即苦諦; 貪愛, 即集諦; 滅, 即滅諦; 過失觀, 即是道諦; 以是義故, 一時見諦.84…The Vibhajyavāda school (分別部) states: If one assembles the contemplation/vision of the ‘marks of suffering’ (聚苦相[duḥkhākāra]觀), penetrates the arising and ceasing mind (達生滅心), and becomes disillusioned with the conditioned (厭有爲; saṃskṛta), one can cultivate the ‘gate of liberation through wishlessness’ (修無願解脱門). If one contemplates the conditioned (觀有爲)—that is, all phenomena—and recognizes them as merely arising and ceasing (唯有生滅), without perceiving any other dharmas (不見余法), one can cultivate liberation through emptiness (修空解脱門; meditation on nonsubstantiality). If one contemplates tranquility (觀寂靜) without perceiving the conditioned (不見有爲), or the marks of arising and ceasing (及生滅相), one can cultivate liberation through signlessness (修無相解脱門; the meditation on no characteristics). Although ‘the four contemplations of the truth of suffering’ (四相) are distinct (雖別), they can be cognized all at once (得一時觀).……分別部説: 若聚苦相觀, 達生滅心, 厭有爲, 修無願解脱門. 若觀有爲, 唯有生滅, 不見余法, 修空解脱門. 若觀寂靜, 不見有爲, 及生滅相, 修無相解脱門. 此中苦相, 即是苦諦; 相生, 是煩惱業, 即是集諦; 相滅, 即是滅諦; 是法, 能令心離相, 見無相, 即是道諦. 若見無爲法寂, 離生滅, 四義一時成. 異此無爲寂靜, 是名苦諦; 由除此故, 無爲法寂靜, 是名集諦; 無爲法, 即是滅諦; 能觀此寂靜, 及見無爲, 即是道諦; 以是義故, 四相雖別, 得一時觀.85

Dharmaguptakas (曇無得等) explain the attainment of insight into the Four Noble Truths as a state of ‘seeing them without uncertainty’ (一無間等). […] Regarding this ‘seeing without uncertainty’ (一無間等), the text further states: ‘In attaining an uninterrupted and unified insight into the truths (於諦一無間等), what is the rationale (何以故)? It is grounded in faith in the noble and wise (信聖賢故), as the World-Honored One (Bhagavat) (世尊) proclaimed: “A bhikṣu (比丘) who has no doubt regarding suffering (苦), no doubt regarding the arising of suffering (集), and similarly, no doubt regarding the cessation of suffering (滅) and the path (道), is said to possess such insight.” This insight is compared to a lamp, which integrates four essential functions:

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGBG | (Foucher 1905–1918) |

| ASI | Archaeological Survey of India |

| ASIAR | Archaeological Survey of India Annual Report |

| ASIFCAR | Archaeological Survey of India Frontier Circle Annual Report |

| ASIR V | (Cunningham 1875) |

| List | (Majumdar 1924) |

| JASB | Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal |

| BD | The Book of Discipline (Vinaya-Piṭaka), 6 vols, translated by Isaline B. Horner, London: Pali Text Society, 1938–66 |

| Vin | The Vinaya Piṭakaṃ, edited by H. Oldenberg, London: Pali Text Society, 1879–83 |

| Skt | Sanskrit |

| P | Prakrit [Prākṛit] |

| Kh | Kharoṣṭhī |

| Gk | Greek |

| Ch | Chinese |

| Jp | Japanese |

| c. | Circa |

| r. | Reigned/ruled |

| j. | juan 卷 |

| d. u. | Date unknown |

| * | Reconstructed |

| T | Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經 [Buddhist Canon Compiled during the Taishō Era (1912–26)]. 100 vols. Takakusu Junjirō 高楠順次郎 and Watanabe Kaigyoku 渡邊海旭 et al., eds. Tōkyō: Taishō Issaikyō Kankōkai 大正一切經刊行會, 1924–1934. Digitized in CBETA (https://cbetaonline.dila.edu.tw/zh/, accessed on 26 March 2025) and SAT Daizōkyō Text Database (https://21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/SAT/satdb2015.php, accessed on 26 March 2025). |

| X | Xinbian xu zangjing 新編卍字續藏經 [Man Extended Buddhist Canon]. 150 vols. Xin wenfeng chuban gongsi 新文豐出版公司, Taibei 臺北, 1968–1970. Reprint of Nakano Tatsue 中野達慧, et al., comps. Dai Nihon zoku zōkyō 大日本續藏經 [Extended Buddhist Canon of Great Japan], 120 cases. Kyoto: Zōkyō shoin 藏經書院, 1905–1912. Digitized in CBETA (https://cbetaonline.dila.edu.tw/zh/, accessed on 26 March 2025). |

| B | Da zangjing bubian大藏經補編 [Supplement to the Dazangjing]. Huayu chuban she 華宇出版社, Taibei 臺北, 1985. Ed. Lan Jifu 藍吉富. |

| Baums and Glass | Catalogue of Gandhari Inscriptions published by Baums and Glass (Item: CKI 116): https://gandhari.org/catalog?itemID=90 [accessed on 26 March 2025]. The entry lists other analyses and mentions of the “Jamālgaṛhī Inscription”. |

| GAB | Gandhāran Art Bibliography (https://www.carc.ox.ac.uk/GandharaConnections/bibliography) [accessed on 26 March 2025] |

| 1 | Official British attempts to organize a system for gaining information on the antiquities of the region began in 1851. Cf. (Punjab Proceedings 1851; Cunningham 1875, pp. 46–48; Errington 2022, pp. 1–2). |

| 2 | In early January 1848, Alexander Cunningham discovered the Buddhist site of Jamāl Gaṛhī using what he considered the first accurate map of the Peshawar basin, produced by Claude-Auguste Court, a French officer under the Sikh ruler Ranjit Singh who created the map while searching for sites associated with Alexander the Great (Court 1836, p. 394; Cunningham 1848, p. 130). Cunningham collected sculptures, including one he misidentified as Queen Māyā, a mistake that later aided in cataloging efforts. His early documentation laid the groundwork for subsequent archaeological research. For further details, see Cunningham (1848, 1873, 1875, 1885); see also Errington (1987, pp. 80, 131, 325) for a chronology of these events. |

| 3 | |

| 4 | See (Cunningham 1875), especially, notes on Jamāl-garhi, pp. 46–53, 197–202, Pl XIII and XIV. |

| 5 | Archaeological Survey of India. 1921. Annual Report of Archaeological Survey of India, Frontier Circle for the Year 1920–1921. Peshawar: Government Press; (Hargreaves 1921a, 1921b, 1922, 1923, 1924a, 1924b, 1926). For a chronological overview of this report and the photographs produced, see (Errington 1987; Behrendt 2004, pp. 17–18). |

| 6 | |

| 7 | |

| 8 | |

| 9 | The scholarship on Gandhāra includes multiple disciplines that extend beyond the immediate scope of this paper and is too extensive to be fully reviewed here. Nevertheless, several recent studies in Gandhāran art and archaeology have directly informed this research. Many of these are listed in the Gandhāran Art Bibliography (GAB), accessed on 26 March 2025, at https://www.carc.ox.ac.uk/GandharaConnections/bibliography. Notable examples include the following: Kurt Behrendt’s (2004) The Buddhist Architecture of Gandhāra, which offers a comprehensive overview and description of the development of 2nd century BCE to 8th century CE Buddhist sacred centers in ancient Gandhāra and present-day northwest Pakistan; Shōshin Kuwayama’s (2006) comprehensive synthesis of the term “Gandhāra,” drawing on diverse source materials in his essay “Pilgrimage Route Changes and the Decline of Gandhāra,” in Gandhāran Buddhism: Archaeology, Art, Texts, ed. P. Brancaccio and K. Behrendt, pp. 107–34; Jessie Pons’ (2018) critical examination of the geography and terminology of Gandhāran art in “Gandhāran Art(s): Methodologies and Preliminary Results of a Stylistic Analysis,” in The Geography of Gandhāran Art, ed. Rienjang, W. and P. Stewart, pp. 3–42; Luca Maria Olivieri’s (2022b) up-to-date overview of the field in “The Archaeology of Gandhāra,” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Anthropology 21; and Stefan Baums’ (2018) “A framework for Gandhāran chronology based on relic inscriptions,” in Problems of Chronology in Gandhāran Art, ed. Rienjang, W. and P. Stewart, pp. 53–70. For further discussion, see also Rienjang and Stewart (2018, 2022), Behrendt (2004, 2007, 2009, 2010, 2017), Dietz (2007), and Rhi (2005, 2008a, 2008b). |

| 10 | |

| 11 | |

| 12 | Now preserved in the “Records of the Monasteries of Luoyang” (Luoyang jialan ji 洛陽伽藍記) of Yang Xuanzhi 楊衒之 from around 547 CE. See the more recent translations by Wang Yi-t’ung, A Record of Buddhist Monasteries in Lo-yang by Yang Hsüan-chih (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984), and Jean Marie Lourme, Yang Xuanzhi: Mémoire sur les monastères bouddhiques de Luoyang (Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 2014). Also see notes by Chavannes (1903, 1915), Liu (2024), and commentary and annotations by Zhou (2010) and Yang (2006). |

| 13 | |

| 14 | Here, defined as solid, round masonry structures in which relics of the Buddha were embedded. |

| 15 | Behrendt (2007, p. 4) notes that a dramatic increase in the construction of Buddhist monasteries and in donations to sacred areas within Gandhāra occurred from about the fourth to the early fifth century CE. Most of the extant stūpas, image shrines, and monasteries date to this late period, and consequently this is when the largest portion of sculpture must have been produced. |

| 16 | Sometimes referred to as the Ephthalites (’White Huns’ mid-4th century CE; cf.: Luoyang Qielanji Jiaoshi 洛陽伽藍記校釋, j. 5: B 12, No. 77, p. 229a9–10). |

| 17 | (Yang 2006, pp. 213–214). For further historical accounts of Gandhāra and the decline of Buddhist institutional life during this period, as well as its effects on visual and textual culture, see (Neelis 2011; Salomon 2018; Olivieri 2022a, 2022b; Pons 2018; Errington 1999–2000). |

| 18 | Da tang xiyu ji 大唐西域記, J. 2: “僧徒五十餘人, 並大乘學也.” (Ji [1985] 2000, p. 256). English translation, see (Beal 1884, p. 112): “Outside the eastern gate of the town of Po-lu-sha is a sangharama with about fifty priests, who all study the Great Vehicle. Here is a stupa built by [sic] Asôka-râja. In old times, Sudana the prince, having been banished from his home, dwelt in Mount Dantalôka. Here, a Brahman begged his son and daughter, and he sold them to him.” |

| 19 | |

| 20 | Cf. Rienjang (n.d.). “Jamālgarhī”, Gandhāra Connections website, https://www.carc.ox.ac.uk/XDB/DMS/Jamalgarhi%20v.%202.pdf accessed on 30 March 2025. |

| 21 | See, for example, Majumdar (1924, pp. 7–8, No. 14); Konow (1929, pp. 110–13); Lüders (1940, pp. 17–20); Bailey (1946, p. 790); Brough (1962, p. 44, n. 3); Shizutani (1965, p. 132; pp. 135–36, No. 1736); Vertogradova (1995, p. 63); Tsukamoto (1996–1998, p. 967); Lin (1998, pp. 349–50); Salomon (2005, p. 377); Neelis (2011, p. 241); and Jantrasrisalai et al. (2016, p. 81), all of whom have, to varying degrees, examined or discussed the epigraphical material addressed in this study and have been recorded in Baums and Glass’s Catalogue of Gāndhārī Inscriptions (see Items: CKI 116; 117; 118; 119; 122; 123); https://gandhari.org/catalog. accessed on 16 June 2025. |

| 22 | Concerning the conventional use of the nomenclature “Fasting Buddha,” see (Rhi 2008b, p. 127, note 9). |

| 23 | Here, “material evidence” refers to both archaeological and epigraphic material. |

| 24 | Schist represents a metamorphic stone that ranges in color from green to black and was commonly used in Gandhāra for masonry and sculpture. See discussion by (Konow 1929, pp. 110–13). |

| 25 | The ASI’s original report notes: “Many antiquities were recovered in removing the debris in this area, the most valuable being the Kharoshthi inscription of the year 369.” See Archaeological Survey of India. 1921. Annual Report of Archaeological Survey of India, Frontier Circle for the Year 1920—1921, Peshawar: Government Press, p. 4. |

| 26 | Image Source: from (Konow 1929, pp. 110–13, No. XLV, pl. XXII.1). For a detailed discussion of the inscriptions’s text, including its romanization and translation, see (Konow 1929; Lüders 1940, pp. 15, 20). |

| 27 | “Year 359” = possibly referring to “Day 1 of Āśvayuj, year 359 of Yona”? For a detailed discussion of the inscriptions’ text, including its romanization and translation, see (Konow 1929, pp. 110–13, pl. XXII.1; Lüders 1940, pp. 15, 20). Concerning further notes on this dating format, see (Salomon 2000, pp. 55–56). |

| 28 | Archaeological Survey of India 1921, p. 4; p. 5, No. 4 “Epigraphy”. |

| 29 | Archaeological Survey of India 1921, p. 5, No. 4. Concerning the ‘Jamālgaṛhī Inscription’s’ excavation process, see (Konow 1929, pp. 110–13; Lüders 1940, pp. 15–49; Shizutani 1974, pp. 87–92; Lin 1988, pp. 150–57; 1998, pp. 349–50; Salomon 2005, p. 377; C. Li 2019, p. 330; Errington 2022, p. 7). |

| 30 | “[]” indicates amendments added by the authors for readability of text, and based on (Salomon 2000, p. 55). |

| 31 | |

| 32 | On the name Dharmaguptaka, see (Salomon 1999, pp. 169, 176; Silk 1999, p. 373, note 34). |

| 33 | “Dhamaüte[ana],” cf. glossing recorded in Baums and Glass (CKI 116); https://gandhari.org/catalog?itemID=90. accessed on 24 February 2025. |

| 34 | (Lüders 1940, p. 20). “Für die Geschichte der buddhistischen Kirche ist die Inschrift nicht ohne Interesse, weil sie zeigt, daß die Dharmaguptakas in den ersten Jahrhunderten n. Chr. auch im Nordwesten Indienseine Stätte hatten, während sie bisher inschriftlich nur für Mathurä bezeugt waren. Im 7. Jahrhundert waren sie nach den Angaben Hüen-tsang’s noch in Udyāna vertreten.” |

| 35 | |

| 36 | For discussions on the problems of determining ‘sectarian’ and ‘school’ affiliations, see Salomon (2008, p. 14), Boucher (2008, p. 190), Anālayo (2017, pp. 58–77), Fussman (2012, p. 198), Willemen (2023, p. 10), and Fukita (2017). |

| 37 | |

| 38 | These two large scriptures were translated by Zhu Fonian 竺佛念 (d. u.) between 412 CE and 413 CE. See (Legittimo 2014, pp. 65–84). |

| 39 | Daoxuan 道宣 was a strong advocate for making the Vinaya for the Dharmaguptaka-Vinaya the most standard version in China. See the Xu gaoseng zhuan 續高僧傳, Further Biographies of Eminent Monks (T. 2060: 620c2-3), and the Sifen lü shanfan buque xingshi chao 四分律刪繁補闕行事鈔 An Abridged and Explanatory Commentary on the Dharmaguptaka-Vinaya (T. 1804: 51c7-9); Daoxuan (T. 1804: 2b19-20); See also, (Heirman 2002a; 2014, pp. 193–206). |

| 40 | Baums and Glass [https://gandhari.org/catalog?section=inscriptions. accessed on 26 March 2025]. |

| 41 | Behrendt (2004, p. 27) notes that typical Buddhist religious centers in Gandhāra comprised a sacred area for public worship and a more private monastic section with vihāras (monasteries) and small devotional structures. The public sacred area and private monastic space were designed to serve the religious needs of at least three distinct communities—lay followers, resident monks, and local and long-distance pilgrims—which included a main stūpa surrounded by smaller stūpas and shrines for either relics or images. Main stūpas refer to the large, central stūpa characteristic of Greater Gandhāran sacred areas; together with a monastery, the main stūpa was among the first structures constructed when a new Buddhist site was established. |

| 42 | See description by Konow (1929, pp. 116–17). |

| 43 | |

| 44 | |

| 45 | In the Catalogue of Gāndhārī Inscriptions, Baums and Glass (see Item: CKI 123) list this inscription as Item: CKI 123, “Jamalgarhi Pavement Stone Inscription,” based on Konow 1929. They reconstruct the text as: “[B]u[dharakṣi]da[sa] tanam(*ukhe)” See: https://gandhari.org/catalog?itemID=97 [accessed on 10 June 2025]. |

| 46 | |

| 47 | (Konow 1929, pp. 115–16). Errington notes that Cunningham reported that seven of the eight Kushāṇa coins found in 1873 were again those of Vāsudeva (Cunningham 1875, p. 194). However, no other details are given, so it is impossible to determine if they were, in fact, issues of “Vāsudeva I” (c. 190–230 CE) or were later imitations (c. 230–380 CE). |

| 48 | |

| 49 | |

| 50 | Errington (2022, p. 19) notes that although scholars have provided similar numismatic evidence found in the region dating to the early 2nd century (c. 113–127 CE), the surviving ruins of Jamāl Garhī’s main stūpa complex are primarily later renovations, despite these no doubt including the extensive re-use of earlier sculptures. Therefore, their combination of elements might be random and may not indicate their original location. |

| 51 | Stūpa courtyards are usually parts of the public sacred area consisting of the main stūpa, surrounding small stūpas, relic shrines, stūpa shrines, and (in later construction) image shrines. For a detailed account of the main stūpa courtyard at Jamāl Garhī, see (Errington 2022, pp. 9–10). |

| 52 | Mohesengqi lü 摩訶僧祇律, j. 33: T. 22, No. 1425, p. 498. See also (Karashima 2018c, pp. 439–69, esp. p. 441). |

| 53 | Sifen lü 四分律, j. 52: T. 22, No. 1428, p. 956. |

| 54 | Translated by Buddhajīva (Ch. Fotuoshi 佛陀什), Zhisheng 智勝, Daosheng 道生 and Huiyan 慧嚴 between 423 and 424 CE. See Huijiao, Gaoseng zhuan. See also the catalog Chu sanzang ji ji, j. 3: T. 55, No. 2145, pp. 21a25–b1 (Buddhajīva, Zhisheng, Daosheng and Huiyan), j. 15: T. 55, No. 2145, pp. 111a28–b2 (Buddhajīva and Zhisheng). |

| 55 | Sifen lü四分律, j. 52: “不如以一摶泥, 爲佛起塔勝….” T. 22, No. 1428, pp. 958b7–24. |

| 56 | Mishasai bu hexi wufen lü 彌沙塞部和醯五分律, j. 26: “摶泥, 而説偈言: ‘不如一[摶]團泥, 爲佛起塔廟.’” T. 22, No. 1421, pp. 172c27–173a1. |

| 57 | T. 22, No. 1421, pp. 172c27–173a1. |

| 58 | Shisong lü 十誦律, j. 56: T. 23, No. 1435, p. 415. |

| 59 | (Cunningham 1879), Pl. III “Plan [and Elevation] of Stūpa”. |

| 60 | |

| 61 | Guanzhong chuangli jietan tujing 關中創立戒壇圖經: T. 45, No. 1892, pp. 807–808. Author’s translation. |

| 62 | Mohesengqi lü 摩訶僧祇律 j. 33: T. 22, No. 1425, p. 498; Translation following (Karashima 2018c, p. 443) with modifications. |

| 63 | T. 22, No. 1425, p. 498. |

| 64 | |

| 65 | Recent discoveries of the so-called Gāndhārī Āgamas show that the manuscripts of the “The Robert Senior Collection of Gandhari/Kharoṣṭhī Buddhist manuscripts” were probably produced by monastics of the Dharmaguptaka lineage. See (Allon and Silverlock 2017, pp. 1–55; Chung 2013, pp. 14, 9–41). |

| 66 | For Prākrit features of the original Indic texts eventually translated into Chinese, including early Mahāyāna texts, see, (Karashima 1992, pp. 262–75; 2006b, 2013a, 2018b; Boucher 1998; Nattier 2008, pp. 21–22). |

| 67 | See (Salomon 2018, p. 62, note 82). |

| 68 | According to Chinese Buddhist art historian Ling Li 李翎, in her lecture titled “Analysis of the History of the Main Stūpa at Sāñchī” (桑奇大塔的歷史辨析), delivered on November 19, 2021, at the Research Center for Buddhist Texts and Art, Peking University (北京大學佛教典籍與藝術研究中心), Sāñchī Stūpa No. 2 was likely the earliest structure built at the site and occupies the northernmost position within the monastery complex. Furthermore, the remains of the early courtyard walls of the Dharmarājika Stūpa, constructed around the 1st century BCE, are located to the south and west. Based on this analysis, it can be inferred that the current location of Stūpa No. 2 would originally have been in the northeastern part of the site. |

| 69 | For discussions on the semantic scope of the term Zhongguo 中國 in Sinitic Buddhist texts, particularly in its use to refer to the ‘central region of northern India,’ see Karashima (2010, p. 647) and Wu (2020, p. 395, note 32). |

| 70 | The explicit reference to the veneration of the East in the Chinese context seems to convey another concept. According to Max Deeg (2023), through the travelogue of Xuanzang, the Datang Xiyu ji 大唐西域記, the idea spread that the eastern region of the Buddhist continent, Jambudvīpa (Ch. Zhanbu zhou 瞻部洲)—identified as China—would morally rank first among all the empires of the four cardinal directions, including Persia as the Western empire. According to Xuanzang, the Indians thus venerated the East and its ruler. Datang Xiyu ji, j. 1, T. 51, No. 2087, p. 869b29–869c, 2: “In the customs of the three rulers [of the South, the North, and the West], the East is highly revered. The doors of their residences are open to the east, and when the sun rises, [they] turn east to venerate [it]. The land of the ruler of men [(i.e., China)] honors the southern direction” 三主 之俗, 東方爲上. 其居室則東闢其戶, 旦日則東向以拜. 人主之地, 南面爲尊. For a discussion of this passage, see Deeg (1999, pp. 241–54; 2023, p. 141). |

| 71 | This “正陽” could allude to ‘facing the emperor.’ |

| 72 | T. 40, No. 1804, p. 134a16–19. Author’s translation. |

| 73 | Yibu zonglun lun 異部宗輪論: T. 49, No. 2031, p. 17. Translation based on (Tsukamoto 2004) with modifications. |

| 74 | There is some debate about which narrative or aspect of enlightenment these fasting images of the Buddha represent. While Rhi (2008a, 2008b), Behrendt (2010), and Wladimir Zwalf (1996) argue that these representations depict the Buddha prior to enlightenment, particularly during or at the point of his six-year fast, Robert Brown (1997) contends that these images might illustrate the 49-day fast under the bodhi tree on the vajrāsana throne, which followed immediately after the Buddha’s enlightenment. Nonetheless, Behrendt (2010) notes that, regardless of whether these images represent his pre- or post-enlightenment fast, they emphasize his role as the ultimate yogin in the wilderness, serving as powerful ascetic expressions of the Buddha’s path. |

| 75 | Sifen lü四分律, j. 32: T. 22, No. 1428, p. 781a3–14. Author’s translation. |

| 76 | The provenance of this rectangular panel piece remains controversial; its reverse side features an inscription of “J,” indicating its origins at Jamāl Gaṛhī. Cunningham proposed that sculptures from the site be incised with a ‘J’ (Cunningham 1885, p. 93), which has become the primary method for identifying artifacts from the 1873 excavation. Following the excavation, the discoveries were distributed among institutions in Calcutta, Lahore, and the British Museum, while some artifacts are in Chandigarh, with others located as far away as Stockholm (Väldskultur Museerna OS-120/S-113B). Errington (2022, p. 7) notes that numbered, photographed sculptures and the incised “J” allow tracking and reconstruction of much of the 1873 archaeological records (see Table of records for Appendix B sculptures, Errington 2022, pp. 7, 36–42), aiding in confirming this sculpture’s origins at the Jamāl Gaṛhī Monastery site. |

| 77 | Museum number 1880.67 “Description” (refer to: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/A_1880-67, accessed on 13 May 2025). |

| 78 | Fo benxing ji jing 佛本行集經, j. 24: T. 03, No. 190, p. 765b12-15, p. 767c1-17. Translated by author(s). For another English translation, see (Beal 1875, pp. 189–95). |

| 79 | |

| 80 | |

| 81 | Sifen lü四分律, j. 32: T. 22, No. 1428, p. 788a8–13. Author’s translation. |

| 82 | Sifen lü四分律, j. 32: T. 22, No. 1428, p. 788a8–10. Author’s translation. |

| 83 | Sifen lü四分律, j. 32: T. 22, No. 1428, p. 789a2–4. |

| 84 | Sidi lun 四諦論: T. 32, No. 1647, p. 377c11–22. Author’s translation. |

| 85 | Sidi lun 四諦論: T. 32, No. 1647, p. 378a1–11. Author’s translation. |

| 86 | Za apitan xin lun 雜阿毘曇心論, j. 11: T. 28, No. 1552, p. 962a20–b3–7. Author’s translation. |

| 87 | (Cunningham 1875, p. 202) (Appendix B: s.6). |

| 88 | Yibu zonglun lun shu shu ji 異部宗輪論疏述記: T. 53, No. 844, p. 577a18–b4. |

| 89 | |

| 90 | Behrendt (2014) also notes that during the turn of the Common Era, Maitreya served as an independent devotional icon. The relative popularity of Maitreya in Gandhāra, compared to northern and western India, suggests that Gandhāran Buddhists were following a different ideological trajectory during the time of the Great Kushans. The emerging Maitreya iconography appears to align with the Gandhāran typology, and the significantly larger production of Maitreya images may indicate that this tradition originated in the northwest and was likely influenced by outside sources. |

References

Primary Sources

Chang ahan jing 長阿含經 [Skt. Dīrghâgama; Lengthy Āgama]. Total 22 juans. Trans. Buddhayaśas 佛陀耶舍 (fl. early 5th cent. CE) and Zhu Fonian 竺佛念 (fl. late 4th to early 5th cent. CE) in 412/13 CE. T No. 1, vol. 1.Chu sanzang ji ji 出三藏記集 [Compilation of Notes on the Translation of the Tripiṭaka]. Total 15 juans. Initially compiled by Sengyou 僧佑 (445–518 CE) in 515 CE. T No. 2145, vol. 55 [Also: Chu sanzang ji ji 出三藏記集. 1995. Beijing 北京: Zhonghua Shuju 中華書局].Da Tang xiyu ji 大唐西域記 [Record of the Western Regions of the Great Tang (Dynasty)]. Total 12 juans. Composed by Xuanzang 玄奘 (fl. 603–664 CE) in 646 CE. T No. 2087, vol. 51 [Also: Da Tang xiyu ji jiaozhu 大唐西域記校注. 2000. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju].Fo benxing ji jing 佛本行集經 [Sūtra of the Collection of the Past Activities of the Buddha; Skt. *Buddha-carita-saṃgrāha]. 60 juans. Translated by Jñānagupta 闍那崛多 (523–600 CE) in 591 CE. T No.190, vol. 3.Gaoseng Faxian zhuan 高僧法顯傳 [Biography/Account of Faxian]. Total 1 juan. By Faxian 法顯 (337–422 CE) sometime between 413 and 420 CE. T No. 2085. [Also: Faxian zhuan jiaozhu 法顯傳校注. 2008. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju], vol. 51.Gaoseng zhuan 高僧傳 [Biographies of Eminent Monks]. Total 14 juans. Compiled by Huijiao 慧皎 (497–554 CE) between 519–520 CE. T No. 2059, vol. 50.Guanzhong chuangli jietan tujing 關中創立戒壇圖經 [Illustrated Sūtra/Scripture on the Ordination Platforms Established in Guanzhong]. Total 1 juan. Composed by Daoxuan 道宣 (596–667 CE). T No. 1892, vol. 45.Jiu Tang shu 舊唐書 [Old History of the Tang]. Total 200 juans. Compiled by Liu Xu 劉昫 (888–947 CE); et al., in 941–945.Mishasaibu hexi wufen lü 彌沙塞部和醯五分律 [Skt. Mahīśāsaka-vinaya; Vinaya of the Mahīśāsaka School]. Total 30 juans. Trans. Buddhajīva (Fotuoshi 佛陀什) and Zhu Daosheng 竺道生 (c. 355–434 CE). T No. 1421, 22: 1a–194b.Mohesengqi lü 摩訶僧祇律 [Skt. Mahāsāṃghika-vinaya; Great Canon of Monastic Rules]. Total 40 juans. Trans. Buddhabhadra 佛陀跋陀羅 (359–429 CE) and Faxian 法顯 (337–422 CE). T No. 1425.Sidi lun 四諦論 [Skt. Catuḥsatyaśāstra; Treatise on the Four Noble Truths]. Total 4 juans. Composed by by Vasuvarman 婆藪跋摩造; Trans. Paramārtha 真諦 (359–429 CE). T No. 1647, vol. 32.Sifen lü 四分律 [Skt. Dharmaguptaka-vinaya or Cāturvargīya- vinaya; Four-Part Vinaya]. Total 60 juans. Translated by Fotuoyeshe 佛陀耶舍 (Buddhayaśas, fl. 400 CE) and Zhu Fonian 竺佛念 (Skt. *Buddhasmṛti, fl. 400 CE) between 405/8 CE and 412. T No. 1428, vol. 22.Sifen lü shanfan buque xingshi chao 四分律刪繁補闕行事鈔 [A Commentary on Conduct and Procedure: Abridgments and Emendations to the Four-part Vinaya]. Total 1 juan. By Daoxuan 道宣 (596–667 CE). T No. 1804, vol. 40.Shisong lü 十誦律 [Skt. Sarvāstivāda-vinaya; Ten Recitations Vinaya]. Total 61 juans. Trans. *Puṇyatara (Foreduoluo 佛若多羅) and Kumārajīva (Jiumoluoshi 鳩摩羅什, 343–413 CE) between 399 and 413 CE. Last two rolls translated by *Vimalākṣa (Beimoluocha 卑摩羅叉) after 413 CE. T No. 1435, 23: 1a–470b.Wei shu 魏書 [Book of the (Northern and Eastern) Wei, 386–550 CE]. Total 114 juans. By Wei Shou 魏收 (506–572 CE) between 551–554 CE (revised 572 CE). Beijing: Zhonghua shuju 中華書局, 1974.Xu Gaoseng zhuan 續高僧傳 [Continued/Extended Biographies of Eminent Monks]. Total 30 juans. Initial completed by Daoxuan 道宣 (596–667 CE). T No. 2060, vol. 50.Yibu zonglun lun 異部宗輪論 [The Cycle of the Formation of the Schismatic Doctrines; Skt. Samayabhedoparacanacakra]. Total 1 juan. Written by By Vasumitra 世友; Translation by Xuanzang 玄奘 (fl. 603–664 CE). T No. 2031, vol. 49.Yibu zonglun lun shu shu ji 異部宗輪論疏述記 [The Cycle of the Formation of the Schismatic Doctrines; Skt. Samayabhedoparacanacakra: Commentary and Explanation Records]. Total 1 juans. Completed by Kuiji 窺基 (632–682 CE). X 53, No. 844.Za apitan xin lun 雜阿毘曇心論 [Heart of Abhidharma with Miscellaneous Additions; Skt. *Saṃyukta-abhidharma-hṛdaya-śāstra/*Abhidharma hṛdaya śāstra]. Total 11 juans. Translation by Fajiu 法救 (d. u.) and Saṅghavarman 僧伽跋摩 (d. u.) from –434? CE. T No. 1552, vol. 28.Secondary Sources

- Allon, Mark, and Blair Silverlock. 2017. Sūtras in the Senior Kharoṣṭhī Manuscript Collection with Parallels in the Majjhima-nikāya and/or the Madhyama-āgama. In Research on the Madhyama-āgama. Edited by Bhikkhunī Dhammadinnā. Taipei: Dharma Drum, pp. 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Anālayo, Bhikkhu. 2017. The ‘School Affiliation’ of the Madhyama-āgama. In Research on the Madhyama-āgama. Edited by Bhikkhunī Dhammadinnā. Taipei: Dharma Drum, pp. 55–77. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, Sir Harold Walter. 1946. Gāndhārī. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 11: 764–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bareau, André. 1955. Les sectes bouddhiques du Petit Véhicule. Paris: Publications de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient, Numéro de collection: 38. [Google Scholar]

- Baums, Stefan. 2018. A framework for Gandhāran chronology based on relic inscriptions. In Problems of Chronology in Gandhāran Art: Proceedings of the First International Workshop of the Gandhāra Connections Project, University of Oxford, 23rd-24th March, 2017. Edited by Wannaporn Rienjang and Peter Stewart. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 53–70. [Google Scholar]

- Beal, Samuel. 1869. Travels of Fah-Hian and Sung-Yun, Buddhist Pilgrims, from China to India (400 A. D. and 518 A. D.). London: Trübner and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Beal, Samuel. 1875. The Romantic Legend of Śakya Buddha. London: Trübner and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Beal, Samuel. 1884. Si-Yu-Ki: Buddhist Records of the Western World. Edited by Hiuen Tsiang. London: Trübner. [Google Scholar]

- Behrendt, Kurt A. 2004. The Buddhist Architecture of Gandhāra. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Behrendt, Kurt A. 2007. The Art of Gandhara in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, New Haven and London: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Behrendt, Kurt A. 2009. The Ancient Reuse and Recontextualization of Gandharan Images: Second through Seventh Centuries CE. Journal of South Asian Studies 25: 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrendt, Kurt A. 2010. Fasting Buddhas, Ascetic Forest Monks, and the Rise of the Esoteric Tradition. In Coins, Art and Chronology II: The First Millennium C.E. in the Indo-Iranian Borderlands. Edited by Michael Alram, Deborah Klimburg-Salter, Inaba Minoru and Matthias Pfisterer. Vienna: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, pp. 299–328. [Google Scholar]

- Behrendt, Kurt A. 2014. Maitreya and the Past Buddhas: Interactions between Gandhara and North India. In Proceedings of the 19th Conference of the European Association for South Asian Archaeology and Art. Edited by Deborah Klimburg-Salter and Linda Lojda. Turnhout: Brepols, vol. 1, pp. 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Behrendt, Kurt A. 2017. The Buddha and the Gandharan Classical Tradition. Arts of Asia 47: 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Bhandarkar, Devadatta R. 1919. Lectures on the Ancient History of India on the Period from 650 to 325 B.C., Delivered in February, 1918. Calcutta: University of Calcutta. [Google Scholar]

- Boucher, Daniel. 1998. Gāndhārī and the Early Chinese Buddhist Translations Reconsidered: The Case of the Saddharmapuṇḍarīkasūtra. Journal of the American Oriental Society 118: 471–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, Daniel. 2008. Review of Allon 2001. Bulletin of the Asia Institute 18: 189–93. [Google Scholar]

- Brough, John. 1962. The Gāndhārī Dharmapada. London Oriental Series; London: Oxford University Press, vol. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Robert. 1997. The Emaciated Gandharan Buddha Images: Asceticism, Health, and the Body. In Living a Life in Accord with Dharma: Papers in Honour of Professor Jean Boisselier on His Eightieth Birthday. Edited by Natasha Eilenberg, Mom Chao Subhadradis Diskul and Robert L. Brown. Bangkok: Silpakorn University Press, pp. 105–15. [Google Scholar]

- Chavannes, Édouard. 1903. Voyage de Song Yun dans l’Udyāna et le Gandhāra. Bulletin de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient 3: 379–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavannes, Édouard. 1915. Song Yun Xing Ji Jie (Notes on the Ancient Geography of Gandhara: A Commentary on a Chapter of Hiuan Tsang). Hong Kong: Superintendent Government Printing. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, Mingzhou 池明宙. 2018. Yindu fangwei guan, fangwei shen he shenmiao chaoxiang guanxi chu tan 印度方位觀、方位神和神廟朝向關係初探. Science & Culture Review Kexue wenhua pinglun 科學文化評論 1: 66–78. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, Jin-il 정진일/ 鄭鎮一. 2013. Vinaya Elements in Āgama Texts as a Criterion of the School Affiliation—Taking the Six vivādamūlas as an Example. Critical Review for Buddhist Studies 불교학리뷰 14: 9–41. [Google Scholar]

- Court, C. A. 1836. Conjectures on the March of Alexander. Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal 5: 387–95. [Google Scholar]

- Cribb, Joe. 2017. The Greek Contacts of Chandragupta Maurya and Ashoka and their Relevance to Mauryan and Buddhist Chronology. In From Local to Global: Pares in Asian History and Culture. Prof. A.K. Narain Commemoration Volume. Edited by Kamal Sheel, Charles Willemen and Kenneth Zysk. 3 vols. Delhi: World Press, pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Crompton, Charles Arthur. 1873. Report on the Exploration of the Buddhist Ruins at Jamāl Garhi during the Months of March and April by the 8th Company Sappers and Miners. In Punjab PWD Proceedings. Local Funds Branch, December. Civil Works: Buildings, No. 1A. Appendix A: 1–7 (reprinted in Punjab Government Gazette, supplement 12, February 1874: 1–7; abridged reprint in Indian Antiquary 3 [1874]: 143–59). Lahore: Punjab Public Works Department. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, Alexander. 1848. Letter to John Lawrence, dated 10-1-1848. Correspondence of the Commissioners Deputed to the Tibetan frontier. Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal 17: 89–132. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, Alexander. 1873. Descriptive list of selected sculptures in the Lahore Central Museum. Punjab Government Gazette 1873 S24: 631–36. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, Alexander. 1875. Jamâl-garhi. In Archaeological Survey of India Report for the Year 1872–1873. Calcutta: The Superintendent of Government, vol. 5, pp. 46–53, 197–202. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, Alexander. 1879. The Stûpa of Bharhut: A Buddhist Monument Ornamented with Numerous Sculptures Illustrative of Buddhist Legend and History in the Third Century B. C. London: W. H. Allen and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, Alexander. 1885. Memorandum for Peshâwar explorations. In Tour through Behar, Central India, Peshawar and Yusufzai 1881–1882. Edited by Henry Baily Wade Garrick. Archaeological Survey of India Report 19. Calcutta: Archaeological Survey of India, pp. 92–94. [Google Scholar]

- Deeg, Max. 1999. Umgestaltung buddhistischer Kosmologie auf dem Weg von Indien nach China. In Religion im Wandel der Kosmologien. Edited by Dieter Zeller. Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, Bern, New York, Paris and Vienna: Peter Lang, pp. 241–54. [Google Scholar]

- Deeg, Max. 2005. Das Gaoseng-Faxian-zhuan als religionsgeschichtliche Quelle: Der älteste Bericht eines chinesischen Buddhistischen Pilger- mönchs iiber seine Reise nach Indien mit Übersetzung des Textes. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Deeg, Max. 2007. A little-noticed Buddhist Travelogue- Senghui’s Xinyu-ji and its Relation to the Luoyang-jialin-ji. In Pramāṇakīrtiḥ: Papers Dedicated to Ernst Steinkellner on the Occasion of His 70th Birthday, Part 1. Edited by Birgit Kellner, Helmut Krasser, Horst Lasic, Michael Torsten Much and Helmut Tauscher. Wien: Arbeitskreis fur tibetische und Buddhistische Studien, pp. 63–84. [Google Scholar]

- Deeg, Max. 2014. Chinese Buddhists in Search of Authenticity in the Dharma. The Eastern Buddhist 45: 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Deeg, Max. 2020. Describing the Own Other: Chinese Buddhist Travelogues Between Literary Tropes and Educational Narratives. In Primary Sources and Asian Pasts. Edited by Peter C. Bisschop and Elizabeth A. Cecil. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 129–51. [Google Scholar]

- Deeg, Max. 2023. Chapter 4: The Christian Communities in Tang China: Between Adaptation and Religious Self-Identity. In Buddhism in Central Asia III. Edited by Lewis Doney, Carmen Meinert, Henrik H. Sørensen and Yukiyo Kasai. Leiden: Brill, pp. 123–44. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz, Siglinde. 2007. Buddhism in Gandhāra. In The Spread of Buddhism. Edited by Anne Heirman and Stephan Peter Bumbacher. Leiden: Brill, pp. 49–76. [Google Scholar]

- Errington, Elizabeth. 1987. The Western Discovery of the Art of Gandhāra and the Finds of Jamalgarhi. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, School of Oriental and African Studies, London University, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Errington, Elizabeth. 1999–2000. Numismatic Evidence for Dating the Buddhist Remains of Gandhāra. Silk Road Art and Archaeology 6: 191–216. [Google Scholar]

- Errington, Elizabeth. 2022. Reconstructing Jamālgarhī and Appendix B: The archaeological record 1848–1923. In The Rediscovery and Reception of Gandhāran Art: Proceeding of the Fourth International Workshop of the Gandhāra Connections Project, University of Oxford, 24th–26th March, 2021. Edited by Wannaporn Rienjang and Peter Stewart. Oxford: Archaeopress Archaeology. [Google Scholar]

- Foucher, Alfred. 1905–1918. L’art gréco-bouddhique du Gandhâra. 2 vols. Paris: L‘École française d‘Extrême-Orient. [Google Scholar]

- Foucher, Alfred. 1915. Notes on the Ancient Geography of Gandhara: A Commentary on a Chapter of Hiuan Tsang; Reprinted Gautam Jetley, New Delhi, 2005. Calcutta: Superintendent Government Printing.

- Fukita, Takamichi. 2017. Back to the Future of Prof. Akanuma’s Age: A Research History of the School Affiliation of the Madhyama-āgama in Japan. In Research on the Madhyama-āgama. Edited by Bhikkhunī Dhammadinnā. Taipei: Dharma Drum, pp. 147–77. [Google Scholar]

- Fussman, Gérard. 2012. Review of Andrew Glass (2007). Four Gāndhārī Saṃyuktāgama Sūtras: Senior Kharoṣṭhī Fragment 5. (Gandhāran Buddhist Texts 4). Seattle: University of Washington Press. Indo-Iranian Journal 55: 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göbl, Robert. 1984. System und Chronologie der Münzprägung des Kušanreiches. Wien: Austrian Academy of Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, Harold. 1921a. Excavations at Jamālgarhī. In ASIAR 1918–1919; Part 1. Calcutta: Government Press, p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, Harold. 1921b. Excavations at Jamālgarhī. In ASIFCAR 1920–1921; Peshawar: Government Press, pp. 2–7, Appendix 5 (List of Antiquities Recovered during Operations: pp. 20–28). [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, Harold. 1922. Excavations at Jamālgarhī. In ASIAR 1919–1920; Calcutta: Government Press, p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, Harold. 1923. Excavations at Jamālgarhī. In ASIAR 1920–1921; Calcutta: Government Press, pp. 6, 24–25, IV–V. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, Harold. 1924a. Conservation and clearance at Jamālgarhī. In ASIAR 1922–1923; Calcutta: Government Press, pp. 19–22, 101, VIId, VIII (plan), IX, XI. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, Harold. 1924b. Excavations at Jamālgarhī. In ASIAR 1921–1922; Calcutta: Government Press, pp. 12, 54–62, XXIII–XXV. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, Harold. 1926. Conservation and Clearance at Jamālgarhī. In ASIAR 1923–1924; Calcutta: Government Press, pp. 16–17, V. [Google Scholar]

- Heirman, Anne. 2002a. Can We Trace the Early Dharmaguptakas? T’oung Pao 88: 396–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heirman, Anne. 2002b. The Discipline in Four Parts, Rules for Nuns according to the Dharma-guptakavinaya. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. [Google Scholar]

- Heirman, Anne. 2014. 9. Abridged Teaching (Lüe Jiao): Monastic Rules between India and China. In Buddhism Across Asia: Networks of Material, Intellectual and Cultural Exchange, Volume 1. Edited by Tansen Sen. Singapore: ISEAS Publishing, pp. 193–206. [Google Scholar]

- Jantrasrisalai, Chanida, Timothy Lenz, Lin Qian, and Richard Salomon. 2016. Fragments of an Ekottarikāgama Manuscript in Gāndhārī. In Buddhist Manuscripts. Edited by Jens Braarvig. Manuscripts in the Schøyen Collection. Oslo: Hermes Publishing, vol. IV, pp. 1–122. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Xianlin 季羨林, ed. 2000. Datang xiyuji jiaozhu 大唐西域記校注. Beijing 北京: Zhonghua shuju 中華書局. First published 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Xianlin 季羨林. 2001. Mile xinyang zai xinjiang de chuanbu 彌勒信仰在新疆的傳布 [The Spreading of Maitreya Faith in Xinjiang]. Wenshizhe 文史哲 Journal of Literature, History and Philosophy 1: 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Karashima, Seishi 辛嶋静志. 1992. The Textual Study of the Chinese Versions of the Saddharmapuṇḍarīka sūtra in the light of the Sanskrit and Tibetan Versions. Bibliotheca Indologica et Buddhologica 3. Tokyo: The Sankibo Press. [Google Scholar]

- Karashima, Seishi 辛嶋静志. 2006. Underlying Languages of Early Chinese Translations of Buddhist Scriptures. In Studies in Chinese Language and Culture: Festschrift in Honour of Christoph Harbsmeier on the Occasion of His 60th Birthday. Edited by Christoph Anderl and Halvor Eifring. Oslo: Hermes Academic Publishing, pp. 355–66. [Google Scholar]

- Karashima, Seishi 辛嶋静志. 2010. A Glossary of Lokakṣema’s Translation of the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā. Bibliotheca Philologica et Philosophica Buddhica XI. Tokyo: The International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology, Soka University. [Google Scholar]

- Karashima, Seishi 辛嶋静志. 2013a. A Study of the Language of Early Chinese Buddhist Translations: A Comparison between the Translations by Lokakṣema and Zhi Qian. Annual Report of the International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology at Soka University 16: 273–88. [Google Scholar]

- Karashima, Seishi 辛嶋静志. 2013b. Was the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā, Compiled in Gandhāra in Gāndhārī?”. ARIRIAB (Annual Report of the International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology at Soka University) 15: 171–88. [Google Scholar]

- Karashima, Seishi 辛嶋静志. 2017. The Underlying Language of the Chinese Translation of the Madhyama-āgama. In Research on the Madhyama-āgama. Edited by Bhikkhunī Dhammadinnā. Taipei: Dharma Drum, pp. 197–209. [Google Scholar]

- Karashima, Seishi 辛嶋静志. 2018a. Ajita and Maitreya: More evidence of the early Mahāyāna scriptures’ origins from the Mahāsāṃghikas and a clue as to the school-affiliation of the Kanaganahalli-stûpa. ARIRIAB (Annual Report of the International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology at Soka University) 21: 181–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karashima, Seishi 辛嶋静志. 2018b. Fodian yuyan ji chuancheng 佛典語言及傳承. Beijing 北京: Zhongxi shuju 中西書局. [Google Scholar]

- Karashima, Seishi 辛嶋静志. 2018c. Stūpas Described in the Chinese translations of the Vinayas. ARIRIAB (Annual Report of the International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology at Soka University) 21: 439–69. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Hidayat. 2015. Jamal Garhi: Tremors Unhinge Mardan’s Architectural Treasure. The Express Tribune. November 9. Available online: https://tribune.com.pk/story/987671/jamal-garhi-tremors-unhinge-mardans-architectural-treasure (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Konow, Sten. 1929. Kharoshṭhī Inscriptions with the Exception of Those of Aśoka. In Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum; Calcutta: Government of India Central Publication Branch, vol. II, Part I. [Google Scholar]

- Konow, Sten, and Rotterdam W. E. van Wijk. 1924. The Eras of the Indian Kharoṣṭhī inscriptions. Acta Orientalia. Ediderunt Societates orientales Batava, Danica, Norvegica curantibus F. Buhl, Havniæ, C. Snouck Hurgronje, Lugd. Bat., Sten Konow, Christianiæ, Ph. S. van Ronkel, Lugd. Bat. Redigenda curavit Sten Konow. Leiden: Brill, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Kuwayama, Shoshin. 2006. Pilgrimage Route Changes and the Decline of Gandhāra. In Gandhāran Buddhism: Archaeology, Art, and Texts. Edited by Kurt A. Behrendt and Pia Branaccio. Vancouver: UBC Press, pp. 107–34. [Google Scholar]

- Lamotte, Étienne. 1958. Histore du bouddhisme indien des origines à l’ère Śaka. Louvain: Bibliothèque du Muséon, vol. 43. [Google Scholar]

- Legittimo, Elsa. 2014. The First Agama Transmission to China. In Buddhism Across Asia: Networks of Material, Intellectual and Cultural Exchange, Volume 1. Edited by Tansen Sen. Singapore: ISEAS Publishing, pp. 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Lèvi, Sylvain, and É. Chavannes. 1895. ĽItinéraire ďOu-k’oung. Journal Asiatique Octobre: Série 9 6: 371–84. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Chongfeng 李崇峰. 2008. The Geography of Transmission: The ‘Jibin’ Route and the Propagation of Buddhism in China. In Kizil on the Silk Road: Crossroads of Commerce & Meeting of Minds. Edited by Rajeshwari Ghose. Mumbai: Marg Publications, pp. 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Chongfeng 李崇峰. 2019. Jiantuoluo yu Zhongguo 犍陀羅與中國 [Gandhāra and China]. Beijing 北京: Wenwu chubanshe 文物出版. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Wei 李薇. 2019. Lüzang yanjiu fangfa xintan: Yi Mulian ru chanding wen xiangsheng wei li 律藏研究方法新探——以目連入禪定聞象聲爲例. Zhexue men 哲學門 Beida Journal of Philosophy 20: 307–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Meicun 林梅村. 1988. Fazangbu zai Zhongguo 法藏部在中國 [Dharmaguptakas in China]. Beijing 北京: Wenwu chubanshe 文物出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Meicun 林梅村. 1998. Hantang xiyu yu Zhongguo wenming 漢唐西域與中國文明 [The Western Regions and Chinese Civilizational during the Han-Tang period]. Beijing 北京: Wenwu chubanshe 文物出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Yi 劉屹. 2024. Songyun Xingji Zhong De Liangchu Cuojian Ji Xiangguan Wenti 宋雲行記”中的兩處錯簡及相關問題 [Two Spots of Textual Misarrangement in the Travelogue of Songyun and Relevant Issues]. Xiyu Yanjiu 西域研究 The Western Regions Studies 2: 56–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lüders, Heinrich. 1940. Zu und aus den Kharoṣṭhī-Urkunden. Acta Orientalia 18: 15–49. [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar, N. G. 1924. A List of Kharoṣṭhī Inscriptions. Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal 20: 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, John. 1918a. A Guide to Sanchi; Calcutta: Superintendent Government Printing.

- Marshall, John. 1918b. A Guide to Taxila; Calcutta: Superintendent Government Printing.

- McCrindle, John W., trans. 1893. The Invasion of India by Alexander the Great. London: Westminster. [Google Scholar]

- Nattier, Jan. 2008. A Guide to the Earliest Chinese Buddhist Translations: Texts from the Eastern Han 東漢 and Three Kingdoms 三國 Period. Bibliotheca Philologica et Philosophica Buddhica X. Tokyo: The International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology, Soka University. [Google Scholar]

- Neelis, Jason. 2011. Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks: Mobility and Exchange within and beyond the Northwestern Borderlands of South Asia. Dynamics in the History of Religion. Leiden: Brill, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Olivieri, Luca Maria. 2021. Gandhāra and North-Western India. In The Graeco-Bactrian Indo-Greek World. Edited by Rachel Mairs. New York: Routledge, pp. 386–417. [Google Scholar]

- Olivieri, Luca Maria. 2022a. Stoneyards and Artists in Gandhara: The Buddhist Stupa of Saidu Sharif I, Swat (c. 50 CE). Venezia: Edizioni Ca’ Foscari. Venice: Venice University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Olivieri, Luca Maria. 2022b. The Archaeology of Gandhāra. In Oxford Research Encyclopaedia of Anthropology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pons, Jessie. 2018. Gandhāran art(s): Methodologies and preliminary results of a stylistic analysis. In The Geography of Gandharan Art. Edited by Peter Stewart and Wannaporn Rienjang. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 3–42. [Google Scholar]

- Punjab Proceedings. 1851. Lahore Civil Secretariat, Press List 12. Serial No. 772. Week Ending 24-5-1851, Nos. 32–34: Preservation of historical monuments. Tokyo: Board of Administration General Department.

- Rhi, Juhyung. 2005. Images, Relics, and Jewels: The Assimilation of Images in the Buddhist Relic Cult of Gandhāra: Or Vice Versa. Artibus Asiae 65: 169–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhi, Juhyung. 2008a. Identifying Several Visual Types in Gandharan Buddha Images. Archives of Asian Art 58: 43–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhi, Juhyung. 2008b. Some Textual Parallels for Gandhāran Art: Fasting Buddhas, Lalitavistara, and Karuṇāpuṇḍarīka. Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 29: 125–53. [Google Scholar]

- Rienjang, Wannaporn. n.d. Jamālgarhī. Available online: https://www.carc.ox.ac.uk/XDB/DMS/Jamalgarhi%20v.%202.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Rienjang, Wannaporn, and Peter Stewart, eds. 2018. Problems of Chronology in Gandhāran Art: Proceedings of the First International Workshop of the Gandhāra Connections Project, University of Oxford, 23rd–24th March, 2017. Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Rienjang, Wannaporn, and Peter Stewart, eds. 2022. The Rediscovery and Reception of Gandhāran Art: Proceedings of the Fourth International Workshop of the Gandhāra Connections Project, University of Oxford, 24th–26th March, 2021. Oxford: Archaeopress Archaeology. [Google Scholar]

- Ru, Zhan 湛如. 2000. Zaoqi fota tudi suo shu yu bupai de sengzhongyoufowufo lun 早期佛塔土地所屬與部派的僧中有佛無佛論. Foxue yanjiu 佛學研究 Buddhist Studies 9: 81–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ru, Zhan 湛如. 2006. Jingfa yu fota: Yindu zaoqi Fojiaoshi yanjiu 淨法與佛塔: 印度早期佛教史研究 [Pure Dharma and Stūpas: Research on Early Indian Buddhism]. Beijing 北京: Zhonghua Shuju 中華書局. [Google Scholar]

- Ruehl, F. 1886. M. Ivniani Ivstini Epitoma Historiarvm Philippicarvm Pompei Trogi. Leipzig: Kessinger Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Salomon, Richard. 1990. New Evidence for a Gāndhārī Origin of the Arapacana Syllabary. Journal of the American Oriental Society 110: 255–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, Richard. 1999. Ancient Buddhist Scrolls from Gandhāra: The British Library Kharoṣṭhī Fragments. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Salomon, Richard. 2000. Two New Kharoṣṭhī Inscriptions. Bulletin of the Asia Institute, New Series 14: 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Salomon, Richard. 2005. The Indo-Greek Era of 186/5 B.C. in a Buddhist Reliquary Inscription. In Afghanistan: Ancien carrefour entre l’Est et l’Ouest: Actes du colloque international organisé par Christian Landes & Osmund Bopearachchi au Musée archéologique Henri-Prades-Lattes du 5 au 7 mai 2003. Edited by Osmund Bopearachchi and Marie-Françoise Boussac. Indicopleustoi: Archaeologies of the Indian Ocean, 3. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 359–401. [Google Scholar]

- Salomon, Richard. 2008. Two Gāndhārī Manuscripts of the Songs of Lake Anavatapta (Anavatapta-gāthā), British Library Kharoṣṭhī Fragment 1 and Senior Scroll 14. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Salomon, Richard. 2017. On the Evolution of Written Āgama Collections in Northern Buddhist Traditions. In Research on the Madhyama-āgama. Edited by Bhikkhunī Dhammadinnā. Taipei: Dharma Drum, pp. 239–68. [Google Scholar]

- Salomon, Richard. 2018. The Buddhist Literature from Ancient Gandhāra: An Introduction with Selected Translations. Somerville: Wisdom Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Shizutani, Masao 静谷 正雄. 1965. Indo bukkyō himei mokuroku: Guputa jidai izen no bukkyō himei インド仏教碑銘目録: グプタ時代以前の仏教碑銘. Kyōto 京都: Heirakuji shoten 平楽寺書店. [Google Scholar]

- Shizutani, Masao 静谷 正雄. 1974. hōzō bu no himei ni tsuite 法蔵部の碑銘について. Tokyo: Indo-gaku bukkyō-gaku kenkyū 印度學佛教學研究, vol. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Silk, Jonathan. 1999. Marginal Notes on a Study of Buddhism, Economy and Society on China. Journal of International Association of Buddhist Studies 22: 359–96. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Sir Marc Aurel. 1912. Excavations at Sahrī-Bahlol. In ASIFCAR 1911–1912. Part II, section v. Peshawar: D.C. Anand & Sons, pp. 9–416. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Sir Marc Aurel. 1915. Excavations at Sahrī-Bahlol. In ASIAR 1911–1912; Calcutta: Government Press, pp. 95–4119. [Google Scholar]

- Strauch, Ingo. 2017. The Indic Versions of the *Dakṣiṇāvibhaṅga-sūtra: Some Thoughts on the Early Transmission of Āgama Texts. In Research on the Madhyama-āgama. Edited by Bhikkhunī Dhammadinnā. Taipei: Dharma Drum, pp. 327–68. [Google Scholar]

- Swati, Muhammad Farooq. 2008. Gandhāra and the Exploration of Gandhāra Art of Pakistan. Ancient Pakistan 19: 131–44. [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto, Keishō 塚本 啓祥. 1961. Insukuripushon to buha インスクリプションと部派. Indogaku Bukkyōgaku Kenkyū 印度學佛教學研究 Journal of Indian and Buddhist Studies 9: 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukamoto, Keishō 塚本 啓祥. 1996–1998. Indo bukkyō himei no kenkyū インド仏教碑銘の研究 [A Comprehensive Study of Indian Buddhist Inscriptions]. 2 vols. Kyōto 京都: Heirakuji shoten 平楽寺書店. [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto, Keishō 塚本 啓祥. 1996–2003. Indo bukkyō himei no kenkyū インド仏教碑銘の研究 [A Comprehensive Study of Indian Buddhist Inscriptions]. 3: Pakisutan Hoppō Chīki no Kokubun 3: パキスタン北方地域の刻文 [Inscriptions in Northern Areas, Pakistan]. Kyōto 京都: Heirakuji shoten 平楽寺書店. [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto, Keishō 塚本 啓祥. 2004. The Cycle of the Formation of the Schismatic Doctrines Translated from the Chinese (Taishō Volume 49, Number 2031). In BDK English Tripiṭaka. Berkeley: Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research. [Google Scholar]

- Vertogradova, V. V. B. B. Bepтoгpaдoвa. 1995. Indiĭskaiâ ėpigrafika iz Kara-tepe v Starom Termeze: Problemy deshifrovki i interpretatŝii Индийcкaя эпигpaфикa из Kapa-тeпe в Cтapoм Tepмeзe: пpoблeмы дeшифpoвки и интepпpeтaции. Moscow: Izdatel’skaiâ firma “Vostochnaiâ literatura” RAN Издaтeльcкaя фиpмa “Bocтoчнaя литepaтypa” PAH. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Bangwei 王邦維. 1989. Lüe lun gudai yindu Fojiao de bupai ji daxiaocheng wenti 略論古代印度佛教的部派及大小乘問題 [A Brief Discussion on the Issues of Ancient Indian Buddhism’s Sects and ‘Smaller’ and ‘Larger’ Vehicles]. Beijing daxue xuebao (zhexue shehui kexue ban) 北京大學學報(哲學社會科學版) Journal of Peking University (Philosophy and Social Sciences) 4: 66–74. [Google Scholar]

- Willemen, Charles. 2001. Sarvāstivāda Developments in Northwestern India and in China. The Indian International Journal of Buddhist Studies 2: 163–69. [Google Scholar]

- Willemen, Charles. 2023. Any Chinese Translation of Theravada Pali. The Indian International Journal of Buddhist Studies 22: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Juan 吳娟. 2020. Mechanisms of Contact-induced Linguistic Creations in Chinese Buddhist Translations. Acta Orientalia Hung 73: 385–418. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Yong 楊勇. 2006. Luoyang jialan ji jiaojian 洛陽伽藍記校箋 [Records of the Monasteries of Luoyang Notes and Commentary]. Beijing 北京: Zhonghua shuju 中華書局. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Xun 章巽. 2008. Faxian zhuan jiaozhu 法顯傳校注 [Collated Annotation of the Biography of Faxian]. Beijing 北京: Zhonghua shuju 中華書局. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Zumo 周祖謨. 2010. Luoyang Qielanji Jiaoshi 洛陽伽藍記校釋 [Commentary on Record of the Monasteries of Luoyang]. Beijing 北京: Zhonghua Shuju 中華書局. [Google Scholar]

- Zin, Monika. 2022. Nagarjunakonda: Monasteries and Their School Affiliations. Acta Asiatica Varsoviensia 35: 315–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwalf, Wladimir. 1985. Buddhism: Art and Faith. London: British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zwalf, Wladimir. 1996. A Catalogue of the Gandhara Sculpture in the British Museum. 2 vols. London: British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jun, W.; Cavayero, M. The Jamāl Gaṛhī Monastery in Gandhāra: An Examination of Buddhist Sectarian Identity Through Textual and Archaeological Evidence. Religions 2025, 16, 853. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16070853

Jun W, Cavayero M. The Jamāl Gaṛhī Monastery in Gandhāra: An Examination of Buddhist Sectarian Identity Through Textual and Archaeological Evidence. Religions. 2025; 16(7):853. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16070853

Chicago/Turabian StyleJun, Wang, and Michael Cavayero. 2025. "The Jamāl Gaṛhī Monastery in Gandhāra: An Examination of Buddhist Sectarian Identity Through Textual and Archaeological Evidence" Religions 16, no. 7: 853. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16070853

APA StyleJun, W., & Cavayero, M. (2025). The Jamāl Gaṛhī Monastery in Gandhāra: An Examination of Buddhist Sectarian Identity Through Textual and Archaeological Evidence. Religions, 16(7), 853. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16070853