Among the various symbolic systems employed, two stand out for their structural and interpretive significance: the Five Phases (wuxing) and the Stems-and-Branches (ganzhi) calendrical framework. The Five Phases—Wood (mu 木), Fire (huo 火), Soil (tu 土), Metal (jin 金), and Water (shui 水)—anchor a wide-ranging network of correspondences linking internal organs, directions, colors, and celestial animals (e.g., Azure Dragon of the East, Vermilion Bird of the South). This system enables the mapping of macrocosmic forces directly onto the human body as a site of alchemical transformation. Closely interwoven with this is the Stems-and-Branches system, a sixty-fold cycle formed by the combination of ten Heavenly Stems and twelve Earthly Branches. While originally calendrical, this temporal model was adopted into neidan as a way of regulating inner alchemical processes—especially the timing of fire (huohou 火候) and the alignment of practice with cosmic rhythms. These two systems appear repeatedly in the diagrams not as background theory, but as integral logics that structure visualized processes of transformation. As subsequent sections will demonstrate, the Illustrated Commentary mobilizes them to translate abstract cosmological patterns into embodied stages of cultivation, fusing numerological time with internal physiology.

These classifications aim to outline the scope of Cheng Yiming’s diagrams rather than impose rigid boundaries, as some diagrams may overlap categories. Cheng’s diagrams exhibit four distinctive features. First, in form, they predominantly use circular diagrams (over 90%)—a large Taiji circle containing specific content, reflecting Cheng’s intentional design. He regarded the Taiji circle (太極一圈) as the cosmic origin and universal law, with alchemical theories being its applied manifestations. Each diagram, while macrocosmically a Taiji circle, microscopically addresses fire phases, medicinal agents, or cultivation stages. Second, in theoretical application, they heavily utilize Yijing principles such as lunar phases, Yin–Yang dynamics, hexagram transformations, Five Phase arrangements (五行), and Four Symbol symbolism (四象). Cheng viewed Yijing symbols as natural expressions of cosmic order, necessitating their use in aligning alchemy with heavenly patterns. Third, in format, text is integrated into diagrams, either as annotations or as intrinsic components—a rare feature in other alchemical texts that enhances accessibility. Fourth, thematically, despite occasional forced interpretations, the diagrams offer greater intuitive clarity than purely textual descriptions in classical alchemical works. Due to space constraints, only select diagrams will be analyzed here, focusing on those that advanced the principles of Mundane Continuation vs. Alchemical Inversion (順凡逆仙) and the joint cultivation of Inner Nature and Vital Force (性命雙修), surpassing earlier contributions.

4.1. Diagrams of Continuation–Inversion and the Three-Five-One (《順逆之圖》《三五一之圖》): A Visual Exposition of Foundational Alchemical Principles

The fundamental principle of alchemy is “Mundane Continuation vs. Alchemical Inversion” (順凡逆仙), which takes ordinary human existence as the reference: following the mundane path is “mundanity” (凡), while reversing it leads to “transcendence” (仙). Specifically, the Precelestial Dao of Non-Being (先天虛無大道) generates ordinary humans through a “Continuation” (順) process of differentiation, while ordinary humans must return to this Precelestial Dao through an “Inversion” (逆) process—emphasizing “Continuation and Inversion” (順逆) in an ontological sense. The Dao, through sequential stages of differentiation, gives rise to humanity (順), and humanity, through sequential stages of refinement, returns to the Dao (逆)—highlighting “Continuation and Inversion” in an evolutionary sense. The

Illustrated Commentary visually codified this principle for the first time.

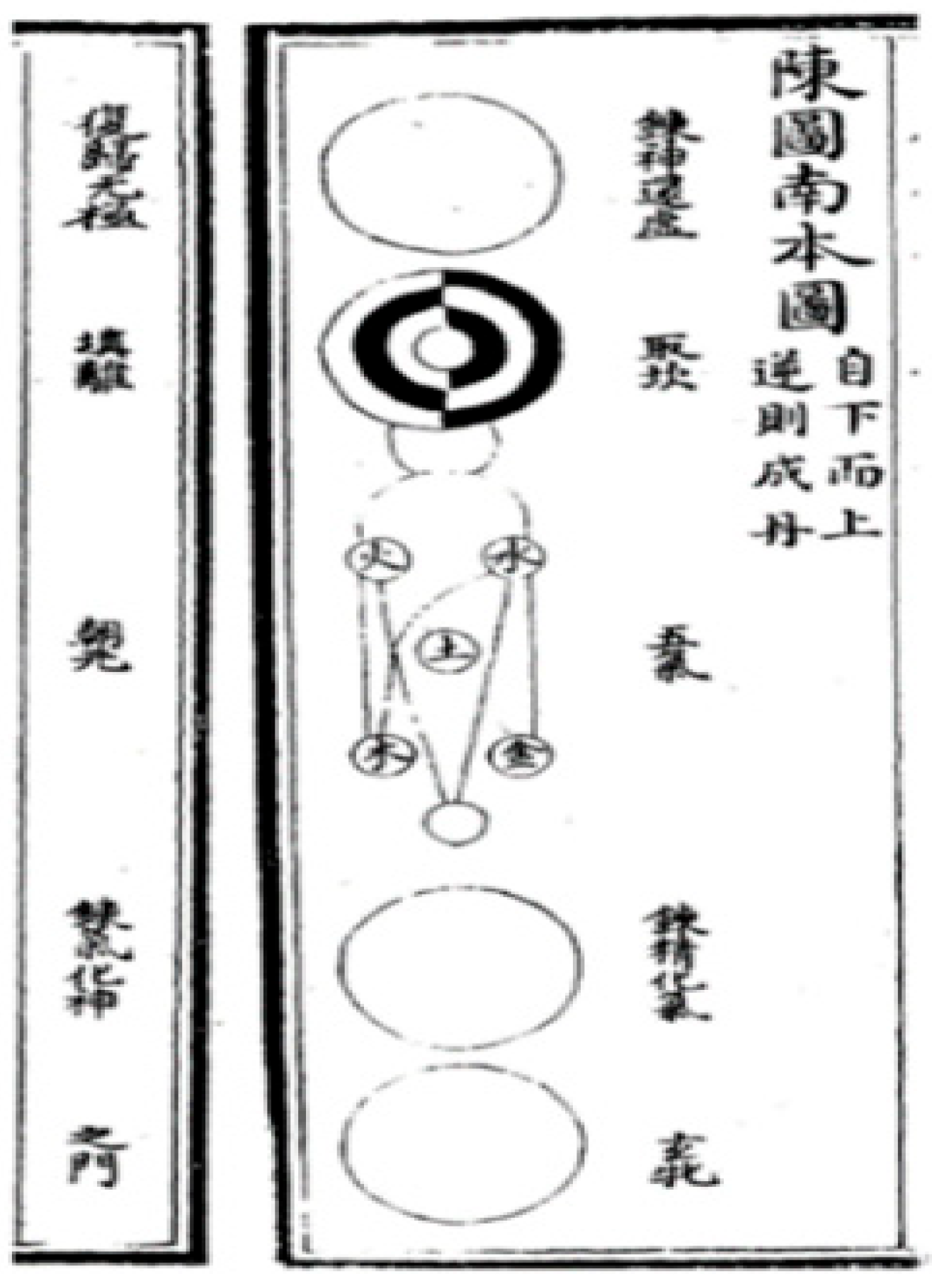

8Chen Tuan’s

Wuji Tu (無極圖,

Figure 1) (

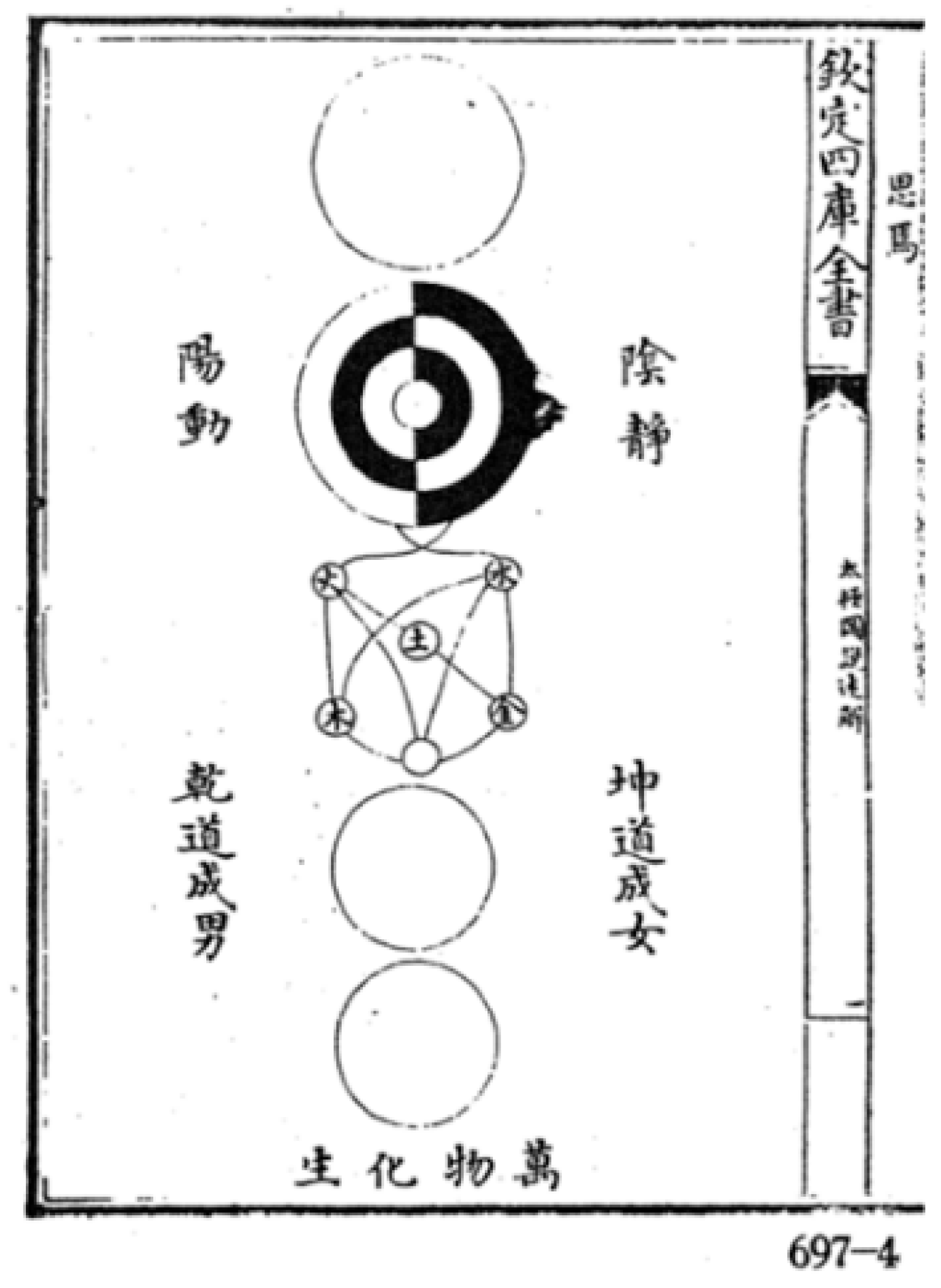

Huang 1986, vol. 40, pp. 750–51) culminates in “returning to the original wuji” (復歸無極), interpreted from bottom to top, while Zhou Dunyi’s

Taiji Tu (太極圖,

Figure 2) (

Cao 1986, vol. 697, p. 4) emphasizes “the generation of all things” (萬物化生), interpreted from top to bottom. The

Illustrated Commentary synthesized these two diagrams, integrating the

Wuji Tu’s concept of “returning to the precelestial” and the

Taiji Tu’s “generative cosmology”, while refining both. Ontologically, the “Continuation” (順) process moves from the precelestial (先天) to the postcelestial (後天), while the “Inversion” (逆) ascends from the conditioned back to the precelestial. Evolutionarily, the “Continuation” clarifies the path of human formation, while the “Inversion” elucidates the method of alchemical refinement. This synthesized diagram is thus termed

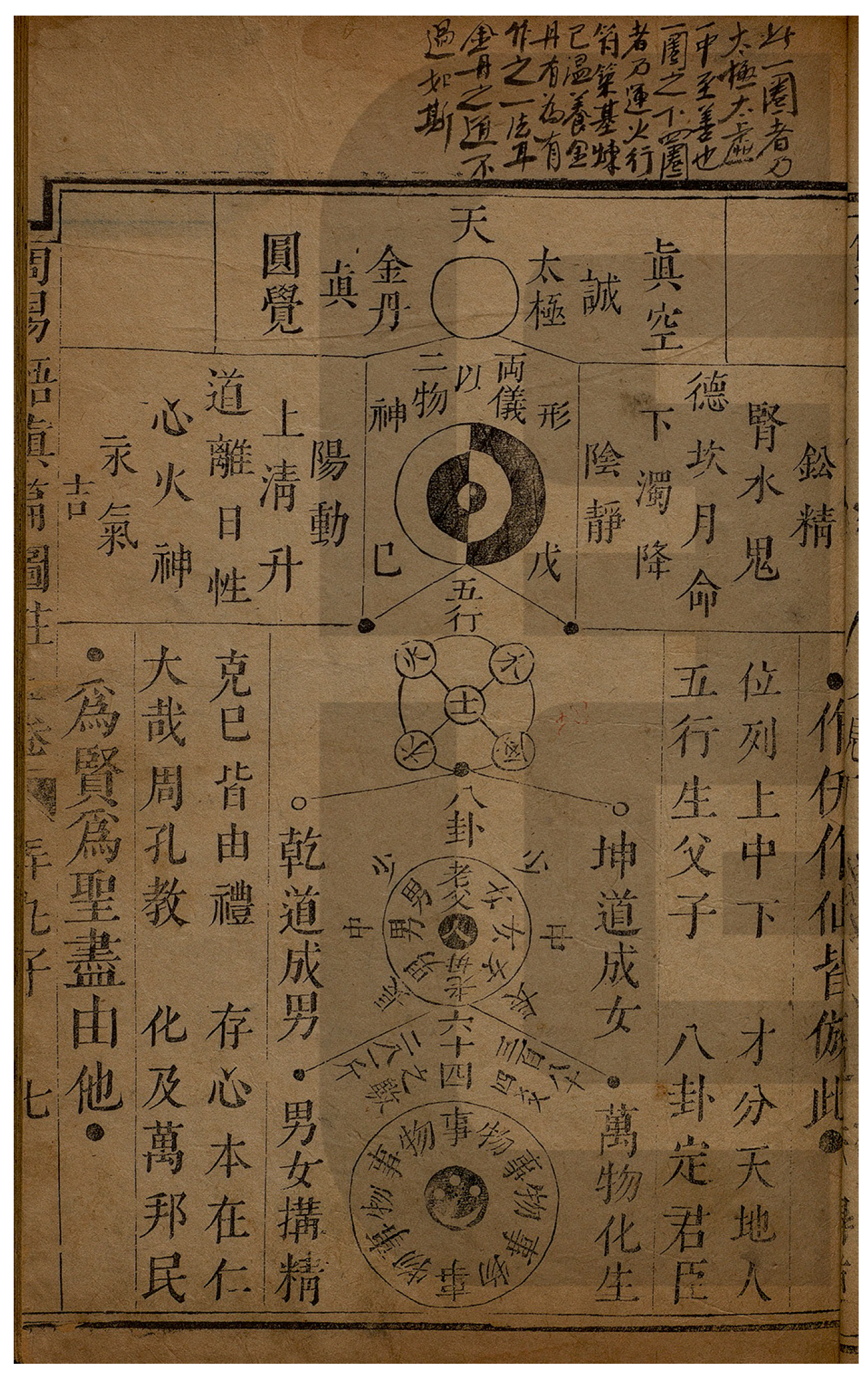

The Diagram of Continuation-Inversion (順逆之圖) (

Cheng [1611] 1717, Wood Volume, folio 8). Cheng Yiming’s refinements primarily focus on the evolutionary framework, as illustrated in

Figure 3.

Viewing the content in

Figure 3 from top to bottom exemplifies the Method of Becoming Human through the Continuation Process (順則成人

shunze chengren), which aligns with the natural flow of cosmic differentiation. This method emphasizes Yin and Yang. Yang is pure and ascends, while Yin is turbid and descends. The ascending Yang and descending Yin constitute Qian 乾 (Heaven 天) and Kun 坤 (Earth 地). The Way of Qian brings forth the male, and the Way of Kun gives birth to the female. Through the union of male and female essences, the ten thousand things (

wanwu 萬物) are generated. The topmost circle of the diagram is labeled

Taiji (太極), which represents the undifferentiated Dao body of emptiness (虛無道體). The Dao gives birth to the precelestial Qi (一炁) from this state of emptiness, and from that the precelestial Qi, Yin and Yang are generated.

The next circle, Two Modes (兩儀), depicts intertwined black and white halves symbolizing Yin–Yang. Their interaction generates the Five Phases (五行): Wood and Fire (Yang) on the left, Metal and Water (Yin) on the right, and Soil (neutral) at the center. Wood and Fire reside above Soil, while Metal and Water lie below. Fire, being more dynamic than Wood, represents the Ultimate Yang (至陽); Water, positioned lower than Metal, represents the Ultimate Yin (至陰). Soil mediates between them. Water nourishes Wood, initiating the Five Phases’ mutual generation (五行相生): Wood → Fire → Soil → Metal → Water → Wood. Mutual generation and restraint reflect Yin–Yang dynamics. The Five Phases and Eight Trigrams (八卦) are further products of Yin–Yang interplay.

The next circle in the diagram is the “Eight Trigrams.” The Illustrated Commentary asserts that “yin and yang recombine to form the Three Bodies” (陰陽再合成三體), and that the “Three Bodies” correspond to the “three lines” (三爻) of the trigrams. As illustrated, Qian (☰) forms males (Father), Kun (☷) forms females (Mother), while Gen 艮 (☶), Kan 坎 (☵), and Zhen 震 (☳) each inherit one Yang line (陽爻) from Qian, becoming Younger Son, Middle Son, and Elder Son; Dui 兌 (☱), Li 離 (☲), and Xun 巽 (☴) each inherit one Yin line (陰爻) from Kun, becoming Younger Daughter, Middle Daughter, and Elder Daughter. These “Father, Mother, and Six Children” constitute the Eight Trigrams. The phrase “threefold synthesis generates all flourishing things” (三體重生萬物昌) refers to the 64 hexagrams (via overlapping trigrams), symbolizing all phenomena, including humans, depicted in the final circle labeled “myriad things” (萬物)—completing the “Continuation” process of human creation.

Conversely, approaching it from bottom to top embodies the Method of Attaining Immortality through Inversion Practice (逆則成仙 nize chengxian)—a path where adepts reverse their vital processes to return to primordial authenticity and merge with the Dao, thereby ascending as transcendent beings (xian 仙). This method emphasizes Inner Nature and Vital Force (xing and ming 性命, also termed Water–Fire, Kan–Li, Lead–Mercury, etc.). Inner Nature (性) pertains to the mind; restless and scattered, it must be stabilized through stillness and nurturing warmth. Vital Force (命) pertains to the body: essence (精) and qi (氣) form its foundation. Essence tends to dissipate downward, qi to scatter outward; thus, qi must be regulated and essence preserved. The lowest circle, the Gate of the Vital Force (xuanpin zhi men 玄牝之門, or Gate of the Mysterious Female), denotes the Mysterious Pass (玄關一竅)—the meditative focus for entering stillness. Guarding the Pass (守竅, also called guarding the One 守一 or Centering 守中) initiates inner meditative alchemy. This practice nourishes essence, qi, and spirit (精氣神), culminating in essence plenitude, qi sufficiency, and spirit vigor, enabling progression.

The next circle, “refining essence into pneuma, refining pneuma into spirit” (煉精化氣, 煉氣化神), involves circulating refined essence and pneuma through the Control Channel and Function Channel (任督二脈), merging them with spirit to form Precelestial Qi (炁, or “Great Medicine” 大藥). Further refinement fuses this qi with the Precelestial Spirit (元神), coalescing into the “Elixir” (丹). The middle circle, labeled “the five pneumas have audience at the Origin” (五氣朝元), interconnects Wood–Fire (left), Metal–Water (right), and Soil (center). In internal alchemy, Fire represents spirit; since Wood generates Fire, Wood symbolizes Precelestial Spirit and Fire Postcelestial Spirit. Water symbolizes essence; as Metal generates Water, Metal represents Precelestial Essence and Water Postcelestial Essence. Wood–Fire and Metal–Water depend on spirit (the True Intention, zhenyi 真意) as the mediating agent, termed “True Soil (zhentu 真土). The convergence of Wood-Fire (one family), Metal-Water (second family), and Soil (third family) constitutes “the five pneumas have audience at the Origin”.

The subsequent circle, with interlocking black and white halves, is labeled “Extracting Kan to Replenish Li” (取坎填離). Kan (☵, Water) and Li (☲, Fire) are symbolic pairs, also termed Lead–Mercury 鉛汞, Essence–Qi 精氣, Heart–Kidneys 心腎, Water–Fire 水火, Ghost–Deity, 鬼神 Dao–Virtue 道德, Sun–Moon 日月, Inner Nature and Vital Force, Above–Below 上下, Pure–Turbid 清濁, Movement–Stillness 動靜, Ascent–Descent 升降, etc. In the postcelestial Eight Trigrams, Kan (☵) occupies the North and Li (☲) the South. However, in the Precelestial Eight Trigrams, North corresponds to Kun (☷, Earth) and South to Qian (☰, Heaven). During cosmic evolution (Dao generating phenomena 道化萬物), the central Yang line of Qian and the central Yin line of Kun exchanged positions. Thus, alchemists regard Kan’s inner Yang and Li’s inner Yin as precelestial residues (先天之物). To revert from postcelestial to precelestial (humanity returning to Dao), Kan’s Yang is extracted to replenish Li’s Yin, restoring the precelestial Qian and Kun—summarized as “Extracting Kan to Replenish Li”.

The topmost circle is labeled “refining spirit and reverting to Emptiness; reversion to the origin” (煉神還虛, 復歸無極). Refining spirit to return to emptiness means that the three treasures condensed through the refinement of qi into spirit are further refined into emptiness. In this way, the Golden Elixir (金丹) is achieved, culminating in a return to the precelestial Dao of the Wuji.

The

Diagram of Three-Five-One (三五一之圖,

Figure 4) (

Cheng [1611] 1717, Wood Volume, folio 34) directly corresponds to the stages of alchemical practice. “Three-Five-One” (三五一) is a core concept in Daoist internal alchemy, fundamentally revealing the cultivation principles of essence (精), qi (氣), and spirit (神) through the fusion of Five Phases’ mutual generation/restraint and the numerology of the

Hetu 河圖 (Chart of the [Yellow] River). The number two corresponds to Fire, three to Wood; Wood–Fire as one family (木火一家) sums to five, associated with the Precelestial Spirit (元神) in alchemical terms. The number one corresponds to Water, four to Metal; Metal–Water as one family (金水一家) sums to five, associated with the Precelestial Qi (元氣) in alchemy. The number five corresponds to Soil, forming its own family, associated with True Intention (真意) in humans. Through the mediation of True Intention, the three families harmonize, coalescing into the “inner Infant” (

Ying’er 嬰兒)—the Great Elixir (大丹). These layered correspondences are central to Cheng Yiming’s vision of inner alchemy, in which physiological processes are symbolically synchronized with cosmological forces. The diagrammatic representations of this model interweave numerology, elemental dynamics, spatial orientation, and temporal cycles. In this view, bodily cultivation proceeds through harmonizing these dimensions, and the diagrams serve as both maps and manuals for initiating such transformation. Thus, the correspondences listed here are not merely categorical—they articulate the metaphysical architecture of the inner elixir. The

Diagram of Three-Five-One is as follows:

Nongwanzi (弄丸子, Appellation of Cheng Yiming) writes the following:

The immortal masters elucidated Three-Five-One beneath the fourteen verses, anticipating that ordinary people could not grasp it. Truly, few can comprehend the Three-Five-One within the Hetu 河圖. The numbers of the Hetu, decoded by Fuxi伏羲 into the precelestial Eight Trigrams, form the foundation for cultivating the Dao and refining the Elixir, as well as the root of self-cultivation and life-nourishment. Thus, the numbers are divided into three families: East-3, South-2, North-1, West-4, and Center-5. ……. Guanjianzi (管見子) states: “This Three-Five-One encompasses the Three-Five-One of cosmic creation, the Three-Five-One of Yin–Yang division and union, the Three-Five-One of bodily fire-times (火候), and the Three-Five-One of Dragon-Tiger intercourse (龍虎交媾). The Three-Five-One of cosmic creation refers to the numerological interplay of the three families in the Hetu; the Three-Five-One of Yin–Yang division and union refers to the transformative numerological shifts in the Zhouyi; the Three-Five-One of bodily fire-times corresponds to the Taiji’s numerical principles of “threefold celestial and twofold terrestrial” (參天兩地); the Three-Five-One of Dragon-Tiger intercourse pertains to the numerical dynamics of “Gate of Wu” (戊門) and “Door of Ji” (己戶) in the interplay of self and other. Though the Three-Five-One shares the same numerical structure, its applications differ profoundly.”Thus, the Cantongqi states in Chapter 11: “When Three and Five harmonize…”; in Chapter 24: “Three-Five and One are the supreme essence of Heaven and Earth”; in Chapter 26: “If Three-Five fail to interact, rigidity and softness split apart”; in Chapter 32: “At root, there are but two substances; at the branches, they become Three-Five”; and in Chapter 33: “A circle of Three-Five inches and one part”—reiterating these principles to illuminate practitioners. Ignorant adherents fixate on one interpretation, recklessly concocting external practices like furnace-refining, altar-building, and chamber-construction, or internal practices like solitary cultivation and silent meridian-counting, oblivious to the inherent Three-Five-One synergy within Kan (☵) and Li (☲).

Boyang Weng (伯陽翁) clarifies: “Zi-Wu (子午) numbers sum to Three; Wu-Ji (戊己) are named Five. When Three-Five harmonize, the Eight Minerals (八石) are regulated.” Further commentaries by immortals, such as Shangyangzi’s (上陽子) precise deductions and Xue Daoguang’s (薛道光) exquisite analyses, elucidate that Kan’s inner Yang and Li’s inner Yin combine to form Three, while Kan’s Wu-Soil (戊土) and Li’s Ji-Soil (己土) each constitute Five. The harmony of Three-Five coalesces into One.”

Ziye (子野) explains: “Three-Five-One signifies the numerical essence of the Five Phases (金木水火土). One is the Taiji. When the Five Phases disunite, they retain their individual natures; when united, they revert to the Taiji. If humans can unify the Five Phases into One, they return to primordial chaos—the inner Infant emerges. Such is the profound meaning of “three families meeting.” After ten lunar months of cyclical refinement, timing and qi align naturally with the sages’ mechanisms. Additionally, Three-Five-One denotes 15 days for advancing fire (進火) and 15 days for retreating the tally (退符), or the synthesis of Three-Five-One into the Ninefold Reverted Golden Elixir (九還金液大還丹). Practitioners must contemplate this deeply, not dismiss it.”

仙師發明三五一,於十四詩下者,料世人不能知也。實然稀者,世人難測《河圖》中之三五一也。蓋《河圖》之數,伏羲演為先天八卦以為造道作丹之基,修身立命之本。故以東三、南二、北一、西四、中五分為三家……管見子曰:“此三五一者有天地生成之三五也,有陰陽分合之三五一也,有人身火候之三五一也,有龍虎交媾之三五一也。”蓋天地生成之三五一者,河圖中三家相見之數也;陰陽分合之三五一者,《周易》中三五一變之數也;人身火候之三五一者,太極中參天兩地之數也;龍虎交媾之三五一者,彼我中戊門己戶之數也。三五一數雖同,而其用各有興。故《參同契》十一章:“三五旣和諧。”二十四章云“三五與一,天地至精。”二十六章云:“三五不交剛柔離分。”三十二章云:“本之但二物兮末而為三五。”三十三章云:“圓三五寸一分。”如此重重發明無非使人洞曉。愚者執其一說,妄猜妄作為,外而燒煉鼎爐,立壇築室;內而獨修自己,默數周天。不思坎離二物之中,自有三五為一之妙。

伯陽翁云:“子午數合三,戊己號稱五;三五即和諧,八石正綱紀。”又加眾仙注釋忒殺分明,上陽子推理最精,薛道光分析極妙。孰知坎中一陽,離中二陰,合而為三。坎中戊土,離中己土,各稱為五。三五和諧,總名曰:一。

子野曰:三五一者,金木水火土五行之數也。一者,太極也。五行不合則各一其性,合則複為一太極。人能以五行合而為一,則複為混沌,嬰兒有兆矣,所謂三家相見之義其妙如此。十月數周,時至氣化,自然符合先聖之機也,又有三五一十五日為進火,三五一十五日為退符,又有三五一合為九還金液大還丹也,學者思之不可

This section focuses on Cheng Yiming’s Three-Five-One numerological model in alchemical practice. Cheng Yiming interprets the Three-Five-One as a development of the numerological principles from the Hetu and Luoshu (洛書Writ of the Luo [River]), combined with the “Three-Five” theory from the Cantongqi. However, the Three-Five-One concept fundamentally stems from the Hetu (河圖, Diagram of the Five Agents’ Generation 五行生成圖) transmitted by Chen Tuan, which serves as the foundational numerological framework for Internal Alchemy (Neidan). Chen Tuan’s Diagram of the Five Agents’ Generation integrates ten numbers with the Five Directions, Five Phases (Wuxing 五行), Yin–Yang, and cosmic symbolism. Its structure is as follows: white circles represent Yang, Heaven, and odd numbers; black dots represent Yin, Earth, and even numbers. Heaven–Earth corresponds to the Five Directions: one and six are paired in the North—since Heaven’s one generates Water, and Earth’s six completes it (天一生水, 地六成之). Moreover, two and seven are in the South—Earth’s two generates Fire, Heaven’s seven completes it (地二生火, 天七成之). Furthermore, three and eight are in the East—Heaven’s three generates Wood, Earth’s eight completes it (天三生木, 地八成之). Four and nine are in the West—Earth’s four generates Metal, Heaven’s nine completes it (地四生金, 天九成之). Five and ten are in the Center—Heaven’s five generates Earth, Earth’s ten completes it (天五生土, 地十成之). This schema forms the core numerological model for alchemical theory. When alchemical terminology is mapped onto this framework, the following system emerges:

East-3 (Dong-3): In the Yijing it corresponds to Zhen 震 (Thunder) and the Eldest Son; in the Five Phases (wuxing) it is Wood; in the Heavenly Stems and Earthly Branches (ganzhi 干支) it is Jia-Yi 甲乙 and Yin-Mao 寅卯; in the human body it represents the Hun 魂 (Ethereal Soul), Xing 性, and Pre-Heaven Spirit (Yuanshen 元神); among the Four Symbols (Sixiang 四象) it is the Azure Dragon (Qinglong 青龍); in External Alchemy (Waidan) it is called True Mercury (Zhengong 真汞.) Alchemical texts also refer to it as “Wood’s Fluid” (Muye 木液), “Jade Rabbit” (Yutu 玉兔), “Green-Robed Maiden” (Qingyi nüzi 青衣女子), and “Turquoise-Clad Foreign Youth” (Bifu hu’er 碧服胡兒). East-3 (Wood-3) combines with South-2 (Fire-2) to form five, both rooted in the Heart.

South-2 (Nan-2): In the Yijing it corresponds to Li 離 (Fire) and the Middle Daughter; in the Five Phases it is Fire; in the ganzhi it is Bing-Ding 丙丁 and Si-Wu 巳午; in the human body it represents Postcelestial Spirit (Houtian shen 後天神, i.e., Consciousness); among the Four Symbols it is the Vermilion Bird (zhuque 朱雀); in waidan it is Cinnabar (Zhusha 朱砂.) Alchemical texts also call it “Red Snow” (Hongxue 紅雪), “Solar Essence” (Rijing 日精), “Crimson Phoenix” (Danfeng 丹鳳), “Vermilion Fire Palace” (Zhuling huofu 朱陵火府), and “Scarlet-Robed Envoy” (Chiyi shizhe 赤衣使者). South-2 (Fire-2) combines with East-3 (Wood-3) to form five, both rooted in the Heart.

North-1 (Bei-1): In the Yijing it corresponds to Kan 坎 (Water) and the Middle Son; in the Five Phases it is Water; in the ganzhi it is Ren-Gui 壬癸 and Hai-Zi 亥子; in the human body it represents Postcelestial Essence (Houtian jing 後天精, i.e., Generative Essence); among the Four Symbols it is the Black Tortoise (Xuanwu 玄武); in waidan it is Black Lead (Heiqian 黑鉛.) Alchemical texts also term it “Lunar Essence” (Yuehua 月華), “Mystic Tortoise” (Xuangui 玄龜), “Aged Ren” (Renlao 壬老), and “Golden Duke” (Jingong 金公). North-1 (Water-1) combines with West-4 (Metal-4) to form five, both rooted in the Body, forming one family.

West-4 (Xi-4): In the Yijing it corresponds to Dui 兌and the Youngest Daughter; in the Five Phases it is Metal; in the ganzhi it is Geng-Xin 庚辛 and Shen-You 申酉; in the human body it represents Po 魄 (Corporeal Soul), Qing 情 (Emotions), and Pre-Heaven Essence (Yuanjing 元精); among the Four Symbols it is the White Tiger (Baihu 白虎); in waidan it is True Lead (Zhenqian 真鉛.) Alchemical texts also name it “White Metal” (Baijin 白金), “Lunar Soul” (Yuepo 月魄), “Golden Crow” (Jinwu 金烏), “White-Haired Elder” (Baitou laozi 白頭老子), and “Plain-Robed Lord” (Sulian langjun 素鍊郎君). West-4 (Metal-4) combines with North-1 (Water-1) to form five, both rooted in the Body, forming one family.

Center-5 (Zhong-5): In the Yijing it is associated with Kun 坤 (Earth) as the Mother; in the Five Phases it is Soil; in the ganzhi, it is Wu-Ji 戊己 and Chen-Xu 辰戌; in the human body it represents True Intention (Zhenyi 真意), mediating and harmonizing the Four Symbols and Five Phases. Alchemical texts refer to it as “Yellow Chamber” (Huangfang 黃房), “Yellow Sprout” (Huangya 黃芽), “Yellow Court” (Huangting 黃庭), “Polaris” (Gouchen 勾陳), “Yellow Matron” (Huangpo 黃婆), “True Oneness” (Zhenyi 真一), “Matchmaker” (Meiren 媒人), “Sacred Embryo” (Shengtai 聖胎), and “True Soil” (Zhentu 真土). Center-5 (Soil-5) has no counterpart and stands alone as its own family.

Cheng Yiming’s discourse, as seen in the cited text, expounds the principle of “Three Families’ Convergence” (Sanjia xiangjian 三家相見) through the three dimensions of the Five Phases, human physiology, and stages of practice.

In terms of the Five Phases, East-3 (Wood-3) and South-2 (Fire-2) form the Wood–Fire family (Muhuo yijia 木火一家), as Wood generates Fire and serves as its “mother”; North-1 (Water-1) and West-4 (Metal-4) form the Metal–Water family (Jin shui yijia 金水一家), as Metal generates Water; Center-5 (Soil-5) stands alone as the Soil family (Tu yijia 土一家). The convergence of these Three Families yields the Great Medicine (Dayao 大藥).

From the perspective of human physiology, East-3 (Wood) corresponds to Xing 性 (Innate Nature), West-4 (Metal) to qing 情 (Emotions), South-2 (Fire) to shen 神 (Spirit), North-1 (Water) to jing 精 (Essence), and Center-5 (Soil) to yi 意 (Intention). Xing governs the Heart, and Shen resides within it, forming the Heart family; Jing governs the Body and aligns with Qing, forming the Body family; Yi mediates the Four Symbols and Five Phases, standing alone as its own family. The convergence of Heart, Body, and Intent likewise yields the Great Medicine.

Regarding stages of practice, the harmonization of qing and xing merges Metal and Wood (情合性即金木並); the union of jing and shen unites Water and Fire; and the Great Stability of Yi (Yi dading 意大定) completes the Five Phases. Refining Essence into Qi (Lianjing huaqi 煉精化氣), the Initial Pass (Chu guan 初關), involves North-1 (Water) and West-4 (Metal) stabilizing the Body—Body quiescence ensures Jing is replenished. Refining Qi into Shen (Lianqi huashen 煉氣化神), the Middle Pass (Zhong guan 中關), involves East-3 (Wood) and South-2 (Fire) stabilizing the Heart—Heart quiescence ensures Qi is consolidated. Refining Shen into Emptiness (Lianshen huaxu 煉神化虛), the Final Pass (Shang guan 上關), involves Center-5 (Soil) returning to its root number (5)—Intent quiescence ensures Shen becomes numinous. When Jing is replenished, Qi consolidated, and Shen numinous, the Three Primordials (Sanyuan 三元) unite and the Elixir (Dan 丹) is perfected.

4.2. True Lead, Fire Phases, and the Precious Moon (真鉛,火候,寶月): Refinement of Neidan Practice Theory (內丹工夫論)

The theory of practice, or the operational system for cultivating neidan (inner alchemy), revolves around xing (性, Inner Nature) and ming (命, Vital Force). The transformations of xing are governed by the heart (xin 心), while those of ming are rooted in the body (shen 身). The heart serves as the sovereign of spirit (shen 神), and the body harbors essence (jing 精), pneuma (qi 氣), and spirit. The dual cultivation of xing and ming entails refining and nurturing the “essence, pneuma, and spirit” within the human body. These terms—jing, qi, and shen—are specialized concepts distinct from ordinary “fluids, breath, and thoughts.” To clarify this distinction, they are often modified by qualifiers: jing is categorized as precelestial essence (xiantian jing 先天精, or Original Essence 元精) versus postcelestial essence (houtian jing 後天精, or “generative essence”); shen is divided into precelestial spirit (xiantian shen 先天神, or Original Spirit, yuanshen 元神) versus acquired consciousness (shishen 識神).

Peng Xiao’s

Mingjing tu (明鏡圖,

Figure 5) pioneered the use of diagrams to systematically elucidate

neidan theory, emphasizing the regulation of

huohou (火候, “fire phasing,” or temporal cycles in alchemical practice). Later, Yu Yan expanded this framework by deconstructing each ring of the

Mingjing tu into multiple diagrams, yet his work remained within Peng’s original paradigm. The

Illustrated Commentary further integrated the theoretical contributions of the

Mingjing tu and Yu Yan’s expansions while offering broader interpretive flexibility. By illustrating each verse of the

Wuzhen Pian, the

Illustrated Commentary not only absorbed existing theories but also advanced them, ultimately constructing a unique

neidan theoretical system.

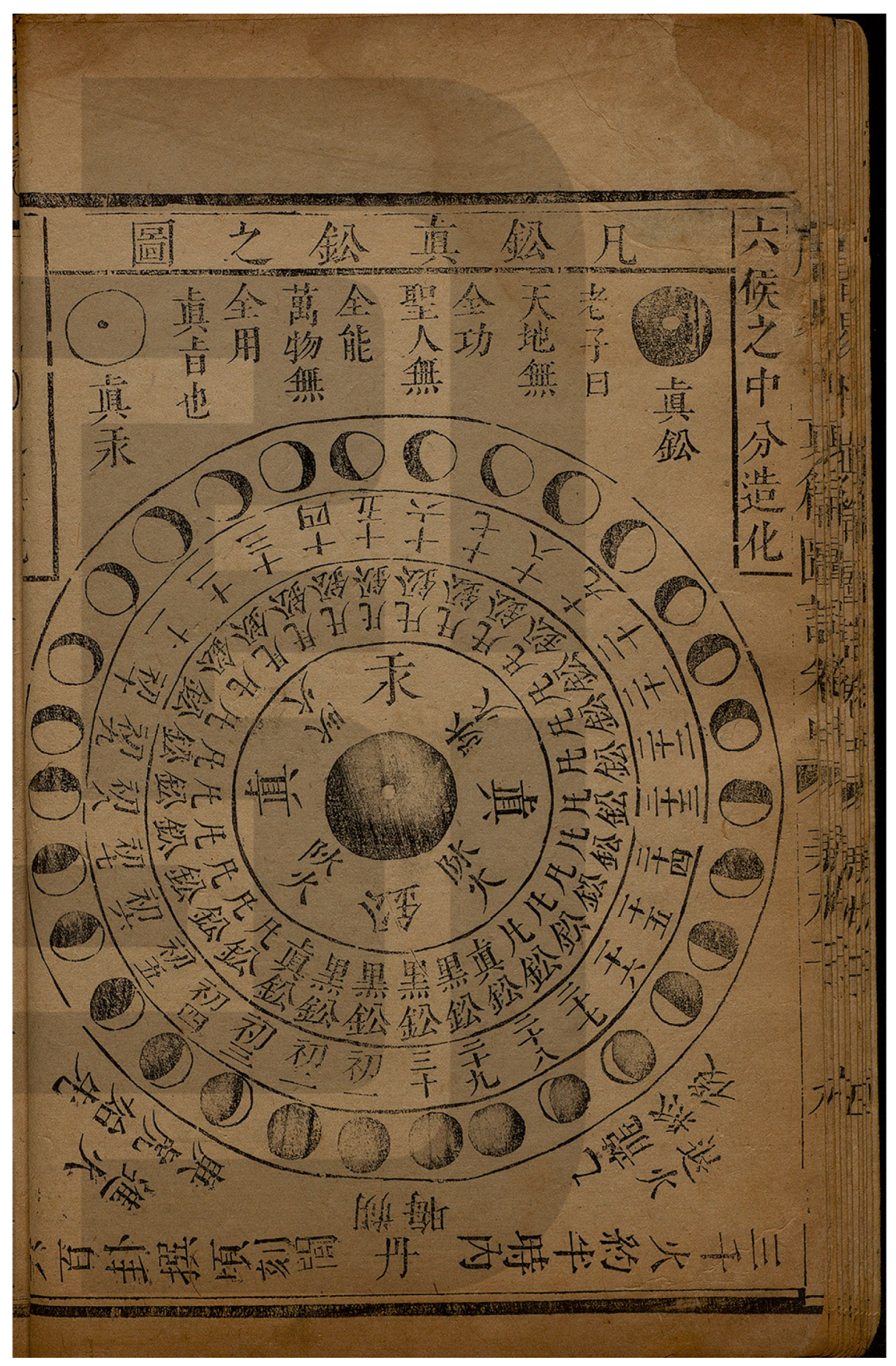

Neidan doctrine posits that to return from the postcelestial (後天) conditioned state to the precelestial (先天) Daoist primordial void, one must rely solely on the precelestial residues (先天之物) endowed by the Dao. Thus, in the cultivation of ming (命功, Vital Force cultivation), only the precelestial essence is employed. Alchemical texts universally use qian (鉛, “lead”) as a metaphor for jing (精, essence). Hence, understanding zhenqian (真鉛, “True Lead,” or true essence) is the first step in ming cultivation. The

Wuzhen Pian states: “Employ not ordinary lead; even True Lead must be relinquished once used,” underscoring the criticality of zhenqian. The commentator Wumingzi (無名子, sobriquet of Weng Baoguang 翁葆光) explains: “Zhenqian is the zhenyi zhi qi (真一之氣, True Unity Pneuma), the precelestial True Yang energy (DZ, vol. 4, p. 724)”. Other commentaries align with this view. The

Illustrated Commentary acknowledges these perspectives while introducing novel developments, as illustrated in the

Diagram of Ordinary Lead and True Lead (凡鉛真鉛之圖,

Figure 6) (

Cheng [1611] 1717, Water Volume, folio 12), which can be seen below:

The diagram centers on the thirty phases of the moon’s waxing and waning, symbolizing the monthly cycle of huohou (火候, “fire phasing” or temporal regulation). Nongwanzi states: “Observe my diagram to grasp the subtlety of using Lead, which lies within the monthly huohou” 觀吾圖中則知用鉛之妙是一月火候也 (

Cheng [1611] 1717, Water Volume, folio 12). The secret of employing Lead resides precisely in this monthly huohou. Nongwanzi explains: “Lead is the Yang pneuma (yi yang zhi qi 一陽之氣) within the Kan 坎 trigram. Its application distinguishes the True from the Ordinary. For instance, on the third day of the lunar month, the moon emerges at Geng 庚; on the twenty-eighth day, it sets at Yi 乙. The union of Yi and Geng (乙庚合) forms the precelestial True Lead (xiantian zhenqian 先天真鉛), which is usable. From the fourth to the twenty-seventh day, it remains postcelestial ordinary Lead (houtian fanqian 後天凡鉛), which must not be used. This is the true secret of employing Lead” (

Cheng [1611] 1717, Water Volume, folio 12).

In neidan symbolism, “Water” represents postcelestial essence (houtian jing 後天精). The Kan trigram (☵) contains a Yang line, embodying the precelestial essence (xiantian jing 先天精, or True Essence) concealed within postcelestial essence. This is zhenqian (真鉛, True Lead), consistent with other commentaries. However, the Illustrated Commentary uniquely integrates this concept with the monthly huohou, specifying that only the third and twenty-eighth days—when Yi and Geng unite—yield precelestial True Lead, while all other days are invalid.

Why must Yi and Geng combine (乙庚合)? Though Nongwanzi does not explicitly state this, the diagram hints that “Geng (虎, Tiger) initiates first; Yi (龍, Dragon) concludes afterward” (庚虎始先, 乙龍終後) (

Cheng [1611] 1717, Water Volume, folio 12). In

neidan, the Tiger symbolizes precelestial essence (Metal phase 五行属金), and the Dragon represents precelestial spirit (xiantian shen 先天神, Wood phase 五行属木). The Dragon arises from Fire, the Tiger from Water (龍從火裏出, 虎向水中生)

9. Yet Metal and Wood clash, as do Fire and Water, preventing cyclical harmony. By incorporating “Soil” into the framework, the mutual generation of the Five Agents (wuxing) is established. This configuration gives rise to the phenomenon of Dunjia 遁甲 (Hidden Stem) (

Zhan 2001): Jia (甲, Wood Yang) conceals itself within Wu (戊, Soil Yang); Yi (乙, Wood Yin) assumes the role of active governance; and Geng (庚, Metal Yang, symbolized as the Tiger) and Yi (乙, Wood Yin, symbolized as the Dragon) form the Yi–Geng combination (乙庚相合), representing the alchemical union of Metal and Wood through their celestial stems. Unlike prior theories that equated zhenqian 真鉛 solely with precelestial essence, Nongwanzi redefines it as the fusion of precelestial essence and spirit, introducing the critical role of precelestial spirit—a significant advancement.

If zhenqian is the union of precelestial essence and spirit (i.e., the “medicine” 藥 for alchemy), how does this “medicine” coalesce into the “elixir” (dan 丹)? What principles govern the huohou required to refine it? Nongwanzi’s

Diagram of Celestial and Terrestrial Transformations in Huohou (天地變化火候之圖,

Figure 7) (

Cheng [1611] 1717, Wood Volume, folio 18) elaborates further on the cyclical interplay of

yin and

yang energies within

neidan practices, delineating the precise temporal phases (huohou 火候) of cosmic and bodily transmutations as codified in the

Zhouyi cantongqi.

The diagram is divided into four concentric rings (from outer to inner). The first ring represents the twenty-four orientations (二十四方位); the second ring consists of fifty black dots and fifty alternating black-and-white dots; the third ring displays twelve hexagrams (十二卦); the fourth ring illustrates twelve lunar phases (十二圓缺). The second, third, and fourth rings inherit principles from Peng Xiao’s Mingjing tu (明鏡圖):

“The fifty black and fifty alternating dots correspond to the hundred marks of Yin talismans and Yang fire, aligning with celestial rhythms. The twelve hexagrams manifest the monthly progression of hexagram lines and the undulations of Dragon and Tiger energies. The twelve time periods (twelve lunar phases) govern the ascent-descent and convergence-divergence of fire phases, operating celestial mechanisms.” 五十點黑,五十黑白,乃陰符陽火百刻之數,應天符動靜也;十二卦者,明逐月爻象進退,龍虎起伏也;十二辰(十二圓缺)者,火候升降鑽合,運天符也 (DZ, vol. 20, p.160)—all describing the principles of advancing and retreating fire phases (火候進退).

This section focuses on the symbolic system of the fifty black and fifty alternating dots, which corresponds to the dualistic structure of yin and yang as distributed through temporal cycles. Rooted in the calendrical logic of the Stems-and-Branches system and the Five Phases, this model encodes the alternation of energetic rhythms in both cosmology and human physiology. In the diagrams, these points mark temporal thresholds for energetic transformations within the body, particularly in regulating fire phases, breath cycles, and the alchemical balance of inner agents. Their systematic presentation shows how the Illustrated Commentary constructs an inner calendar, aligning human refinement with cosmic order.

The first ring constitutes Nongwanzi’s original innovation. How should this ring be interpreted? Nongwanzi quotes an annotation by Wumingzi 無名子 (sobriquet of Weng Baoguang 翁葆光) inscribed within the diagram:

“When lead encounters the birth of Gui, ‘birth of Gui’ signifies the Chou hour (丑時). When Metal meets ‘distant gaze,’ ‘distant gaze’ denotes the moon approaching waning. The fullness of the moon resides in oral formulae; the subtlety of the midnight hourlies in heart-to-heart transmission. The cosmic breath-count follows faint numerics, while the jade clepsydra’s chill echoes rhythmic drips. These are secret teachings orally transmitted by perfected beings.”

铅遇癸生,癸生者,时将丑也。金逢望远,望远者,月将亏也。月之圆,存乎口诀:时之子,妙在心传,周天息数微微数,玉漏寒声滴滴符。此真人口口相传之密旨也.

(See upper half of the diagram) (DZ, vol. 4, p. 717)

This serves as the key to deciphering the first ring, with its crucial information concerning the timing of medicinal substance collection (採藥) and fire phase modulation. Careful analysis reveals that Nongwanzi adapts the Daoist geomancy method of “Twenty-Four Mountains” in this ring, aligning it with the “hundred marks” system through specific derivations to represent the “cosmic fire phases” (Zhou Tian huo hou 周天火候) in neidan practice.

The “Twenty-Four Mountains Method” (二十四山法) refers to the system of twenty-four directional orientations. Specifically, it arranges the “Eight Celestial Stems,” (八天干) “Twelve Earthly Branches,” (十二地支) and “Four Corner Trigrams” (四維卦) in a cyclical pattern, as stated in

Qing Nang Xu 青囊序: “The innate compass holds twelve divisions; the acquired framework adds the Stems and Corners.” 先天羅經十二文,後天再用干與維(

Zeng 1986, p. 85). Orientations include Mao (east), Wu (south), You (west), Zi (north), Kun (southwest), Xun (southeast), Qian (northwest), and Gen (northeast). Starting from the east, the sequence proceeds as follows: Jia 甲, Mao 卯, and Yi 乙; Chen 辰, Xun 巽, and Si 巳; Bing 丙, Wu 午, and Ding 丁; Wei 未, Kun 坤, and Shen 申; Geng 庚, You 酉, and Xin 辛; Xu 戌, Qian 乾, and Hai 亥; Ren 壬, Zi 子, and Gui 癸; and Chou 丑, Gen 艮, and Yin 寅. Nongwanzi quadruples these twenty-four orientations to obtain ninety-six divisions, then inserts a “Wei 維” character between each of the Four Corner Trigrams (Xun, Kun, Qian, and Gen), perfectly matching the “hundred marks” (百刻) numerical framework.

These “twenty-four orientations” (hundred-mark orientations) carry auspicious or inauspicious attributes based on interactions among the Five Phases, hexagram principles, and conjunctions/conflicts of Celestial Stems and Earthly Branches. Nongwanzi ingeniously repurposes this system; auspicious positions (吉位) mark times for medicinal substance collection and elixir refinement, while inauspicious ones signify phases of natural operation. As shown in the diagram, the Kun trigram position (southwest) corresponds to the third lunar day—the moment of medicinal substance generation—while the Gen trigram position (northeast) aligns with the twenty-eighth day—the time of elixir completion. These two orientations are “auspicious positions,” coinciding with the emergence of zhenqian (真鉛 True Lead, the medicinal substance) described earlier.

How does the huohou (火候, fire phasing) operate between the “medicinal substance” of the third day and the “elixir” of the twenty-eighth day? Nongwanzi states: “A full cycle of huohou completes through 384 zhu (銖, ancient weight units).” 火候一週三百八十四銖圓成 (

Cheng [1611] 1717, Wood Volume, folio 18). To count 384 zhu, the text adds the various hours together as follows. From the Zi to Si hours (子至巳), “the progression of Yang Fire進陽火”.

10 This corresponds to 216 ce (策, counting rods)

11 of Qian, excluding 36 ce reserved for the “bathing period” (沐浴, muyu, a time of purification or decontamination in which Fire and Water neither rise nor descend) during the Mao 卯 hour, resulting in 180 actualized zhu. From Wu to Hai hours (午至亥), “the descent of the Yin Fire 退陰符”.

12 This aligns with 144 ce of Kun, excluding 24 ce for the You-hour(酉時)bathing period, yielding 120 actualized zhu. Including the 60 zhu for bathing and 24 zhu as intercalary surplus, the total sums to 384 zhu.

Both diagrams feature a central “white dot within a black circle” derived from the

precelestial Lingji Diagram (先天靈極圖). Precelestial signifies the Dao of precelestial emptiness (虛無大道), while Lingji (靈極, “spiritual pivot”) denotes “When the Dao is empty 虚, it becomes vast 大; when the mind is empty, it attains spiritual potency 靈. Thus, the precelestial spiritual pivot (靈極) is the foundational aperture 始竅 of Heaven and Earth, and the transformative source of all things” (

Shi 2015, p. 559). By adopting this motif, Nongwanzi symbolizes zhenqian as the return to the root of the precelestial Dao.

After “obtaining the medicinal substance and coalescing the elixir (得藥結丹),” one enters xinggong (性功, Inner Nature cultivation)—the refinement of mental–spiritual nature where the heart governs spirit. This marks the “spirit-refining” stage. Spirit (shen 神) divides into shishen (識神, conscious spirit) and zhenshen (真神, true spirit). Post-elixir formation, conscious spirit recedes, and true spirit assumes sovereignty. Nongwanzi illustrates this through his

Diagram of the Precious Moon Wheel (一輪寶月之圖,

Figure 8) (

Cheng [1611] 1717, Soil Volume, folio 22), which is as follows:

The diagram’s main body comprises the following twenty-eight lodges (or constellations) (the system of the

ershiba xiu 二十八宿): the Azure Dragon of the East (角 Jiao, 亢 Kang, 氐 Di, 房 Fang, 心 Xin, 尾 Wei, and 箕 Ji); the Black Tortoise of the North (斗 Dou, 牛 Niu, 女 Nü, 虛 Xu, 危 Wei, 室 Shi, and 壁 Bi); the White Tiger of the West (奎 Kui, 婁 Lou, 胃 Wei, 昴 Mao, 畢 Bi, 觜 Zi, and 參 Shen); and the Vermilion Bird of the South (井 Jing, 鬼 Gui, 柳 Liu, 星 Xing, 張 Zhang, 翼 Yi, and 軫 Zhen). Unlike the Mirror Diagram, which uses these to represent “cosmic fire numerics of celestial cycles” (周天行度火數), Nongwanzi interprets them as “the celestial precious moon and the bodily golden elixir” (天上之寶月, 人身之金丹), correlating the twenty-eight lodges with the natural rhythms of human organs.

13 The set of correspondences relates to the twenty-eight lodges, an astral schema traditionally used for calendrical regulation and cosmography. In the

Illustrated Commentary, this star system is mapped onto the human body, correlating each constellation with an internal site or energetic node. The integration of this system reflects a hallmark of Daoist visual alchemy: the embedding of celestial rhythms within the practitioner’s physical form. Such correspondences allow the practitioner to embody the cosmos through a coded map of the stars, achieving an internal microcosm that mirrors macrocosmic order. This mapping is an essential example of how Yijing-based numerology and Daoist physiology are joined in the visual logic of the

Illustrated Commentary.

Specifically, ordinary people are burdened by incessant thoughts and worries—this is the work of shishen (識神, postcelestial spirit). Zhenshen (真神, true spirit)

14 abides in perpetual clarity and stillness, free from mental agitation. Both spirits coexist within the body. During the minggong (命功, Vital Force cultivation) stage, shishen must guide and harmonize the mind–body to stillness, allowing zhenshen (precelestial spirit) to emerge. After elixir coalescence, only zhenshen remains sovereign, enacting the method of vacuous stillness and non-action. Among the twenty-eight lodges, the Azure Dragon governs the East, the White Tiger the West, the Vermilion Bird the South, and the Black Tortoise the North. Aligning these with human physiology, East corresponds to Liver–Wood, South to Heart–Fire, West to Lung–Metal, North to Kidney–Water, and Center to Spleen–Soil. The Liver governs blood, the Heart governs spirit, the Lungs govern qi, the Kidneys govern essence storage, and the Spleen governs transformation. The natural cycles—Wood (Liver) generating Fire (Heart), Fire generating Soil (Spleen), Soil generating Metal (Lungs), Metal generating Water (Kidneys), and Water generating Wood—proceed spontaneously, requiring no intervention to refine the “bodily golden elixir (renshen jindan 人身金丹).” By correlating the celestial movements of the twenty-eight lodges with the autonomous functions of bodily organs, Nongwanzi demonstrates that this stage demands adherence to non-action (無爲), aligning with natural spontaneity. As Li Daochun 李道純 (fl. 1288–92) of the Yuan dyna sty states in

Zhong He Ji (中和集 Anthology of Central Harmony): “At this stage of practice, not a single word is needed” (DZ, vol. 4, p. 489). Through inner contemplation, stable illumination, nurturing warmth, returning to the origin, and realizing the mind’s true nature, one may ultimately shatter emptiness and unite with the Dao.