1. Introduction

In 1509, shortly before Afonso de Albuquerque took over as governor of India, Diogo Lopes de Sequeira commanded the first Portuguese fleet to reach Malacca. In 1513, at the behest of King Manuel I, Jorge Alvares’s voyage found the “land of the chins” (

Braga 1955, p. 27) and opened the way for the first time to the routes from Malacca and Canton. It meaningfully led to closer Sino-Portuguese relations and, consequently, to the beginning of a process of discovery of a civilization that was very closed and ignored by the Western world but to which the Portuguese accommodated themselves and relatively opened to the new world. Forty years later, the settlement of the Portuguese in 1553 on the island of Macau expanded relations with the Chinese authorities. As a result, Christianity and other local religions inevitably crossed paths in an ingenious confluence, demonstrating a religious and artistic syncretism with Ming China. It can be observed that the nature of Sino-Portuguese contacts and the essential role that Portugal (and Macau) played in the early modern period on the political and economic stage, as well as artistic and religious interaction between the Far East and Europe.

Then, in 1582, with the arrival of Father Matteo Ricci, the process of missionizing China was even more encouraged, which soon involved a hybrid experiential form, with the backdrop of Christianity in its deep dialogue with Asian religions, within different cultural contexts and religious policies during historical periods. Focusing on Sino-Portuguese relations, we can observe some continuity in Portugal’s ways of dealing with China over successive centuries—peacefully, in harmony, and with wisdom. Especially the Christian objects made by Chinese craftsmen lived through the experience of contact with others and embodied multiple layers of symbolic meaning, presenting an approach to artistic hybridization, thus creating an innovative and accommodating visual symbiosis that linked different cultural and religious contexts. As Jorge Flores summarizes, highlighting the material universe of Sino-Portuguese relations, in the objects we read the Portuguese East as much or more than in the documents (

Flores 1998, p. 51). And David Morgan also emphasizes that attention to the reliquaries, relics, images, and sacred spaces in which and before which acts of devotion take place would have ‘enfleshed’ what texts have to tell us (

Morgan 2010, p. 43).

The present study is mainly based on Homi K. Bhabha’s conception of cultural hybridity (

Bhabha 1994) and Peter Burke’s cultural translation (

Burke 2007) to frame the artwork analysis. Bhabha proposes a theory of cultural hybridity, including phenomena such as mimicry, ambivalence, and slippage, especially in colonial art history. Mimicry reflects that which is “almost the same, but not quite” (p. 122). Ambivalence enables the development of fluid colonized identities, as colonial discourse itself lies within a state of in-betweenness (pp. 122–23). The slippage is the excess or difference that appears in an act of mimicry within an ambivalent colonial state (p. 122). During the ivory manufacturing process, mimicry and slippage were effective tools for Chinese carvers to establish the religious iconography they or the society at that time needed. It is precisely because of the mutual mimicry between the image of Songzi Guanyin and the Virgin and Child that the visual images of two different religions collide and overlap, blurring the visual boundaries and giving the Sino-Portuguese ivory sculpture a visual bilingualism that provides different interpretations for different audiences. Moreover, ambivalence is the state and result presented by intentionally or unintentionally created iconography, which allows viewers to interpret and understand according to their aesthetic codes, cultural ideology, and religious beliefs. Multiple religious interpretations can be conveyed in a single ivory sculpture.

Burke asserts that translation implies ‘negotiation’, moving beyond the worlds of trade and diplomacy to refer to the exchange of ideas and the consequent modification of meanings. And the idea of negotiated translation is particularly appropriate to the mission field. Christian missionaries had to decide how far they could go in adapting (or ‘accommodating’) the Christian message to the culture in which they were working (p. 9). Burke also discusses that the activity of translation necessarily involves both decontextualizing and recontextualizing, first reaching out to appropriate something alien and then domesticating it (p. 10). In this cultural encounter between China and Portugal (or Europe), the ivory sculpture of the Virgin and Child undoubtedly played an important role, and missionaries also used the power of images to carry out appropriate cultural translation.

The images of the various invocations of Our Lady constitute, due to their abundance, diversity, and iconographic value, the most important group of Luso-Eastern imagery (

Távora 1983, p. 35). The Christian iconography of the Virgin Mary has been extensively studied in the academic world, especially by Chinese scholars

Chen (

2010,

2013,

2018) and

Song (

2008,

2018). Chen indicates that in an intercultural setting, the female figure with child could be identified as both the Buddhist Guanyin and the Catholic Virgin Mary. Moreover, the interactions of the Catholic Madonna Images with Chinese Visual discourses went beyond Catholic iconography and missionary control. Song in detail explores Marian devotions’ emergence and early development in China from the 7th century to the 17th century. Both examined how the Jesuit missionaries presented and reproduced Marian images in China through in-depth analysis of textual and visual sources. In visual representations, two-dimensional visual images are extensively analyzed, like Madonna and Child carved on a tombstone in Yangzhou; Christian iconography in European prints, such as João da Rocha’s

Rules for Reciting the Rosary (誦念珠規程 [

Song nianzhu guicheng]); Giulio Aleni’s

Explanations on the Images of the Incarnated Lord of Heaven (天主降生出像經解 [

Tianzhu jiansheng chuxiang jingjie]); and Johann Adam Shall von Bell’s

Books and Pictures Presented to the Emperor (進呈書像 [

Jincheng shuxiang]), and the well-known Chinese Marian image painting housed in the Field Museum of Chicago, which is the Chinese-style copy of the Madonna icon of the Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome. Moreover, a recent study explores the religious syncretism through a comprehensive analysis of the Guanyin/Madonna and Child painting housed in the British Museum (

Liu et al. 2025). Although the fact that missionaries ordered statues and preached through them has been documented in the textual material, there has not been a detailed visual analysis of this three-dimensional image, especially the ivory sculpture of the Virgin and Child representing Sino-Portuguese imagery and early Portuguese religious influence in China.

This article will approach a case study on a representative Sino-Portuguese ivory sculpture of the Virgin and Child, dating from the late 16th or early 17th century, currently housed in the National Museum of Ancient Art (Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga) in Lisbon. Under the influence of Christianity and through the cultural prism of Chinese carvers, this ivory sculpture exhibits a distinct artistic hybridity. As a piece of religious art, this ivory sculpture transcends time and region. It exhibits visual bilingualism, offering different narratives to Chinese audiences and Catholic missionaries. Through modifications to details and invisible interactions with the “Child-giving Guanyin”, two artistic and religious iconographies converge, conveying significant religious and cultural meanings differently.

Through an in-depth iconographic study of the Sino-Portuguese ivory sculpture and a comparative visual critique with Guanyin representations and European prototypes in ivory sculptures, this study seeks to explore the characteristics of Sino-Portuguese ivory sculptures as a three-dimensional iconography and to discover how Sino-Portuguese ivory sculptures of the Virgin and Child can “speak” in two languages, in other words, how they could be legible visual forms in both Chinese and Christian contexts, using “visual bilingualism” as a central concept in this article. With objectives, this article examines the mentioned Sino-Portuguese ivory sculptures of the Virgin and Child and other representative ivory sculptures, highlighting their hybridization and adaptation. Moreover, it provides a fresh perspective on the significance of religious art in intercultural exchanges through a new case study, aiming to explain the results of complex religious and cultural encounters more reasonably.

The first part will provide a brief introduction to the Sino-Portuguese ivory sculpture, with particular reference to the complex identity embodied in it. The second part analyzes the incorporation of elements of Chinese culture into the materiality and visuality of the Christian mission in China during the Late Ming, considering religious sculpture as a visual religion. That means that, in an interdisciplinary approach, images are not only objects of aesthetic contemplation but also material evidence for historical analysis, traces of rite and myth, and elements of devotion (

Morgan 2010, p. 42). The third part discusses the interaction between the images of the Virgin and Child and the Songzi Guanyin in an intercultural setting. It explores their cultural transformation and mutual intelligibility under the religious policy and historical context. And the last part explores the characteristics of the Sino-Portuguese Virgin and Child ivory sculpture.

2. Sino-Portuguese Ivory Sculpture

Sculpture has been essential in art history, especially in the 12th and 13th centuries. It shares the same three-dimensional space with its viewer, and through its facial expressions, movements, and vivid clothing, it has a more powerful visual impact on the viewer and fulfills the function of an image. Meanwhile, the sculpture is not just an image but a physical object with both material and visual nature. It is often placed in a specific location to connect the environment and even viewers’ thoughts to another order or a spiritual world, thus having the power to change the way of thinking, influence viewers’ feelings, and guide them to perceive the world in a completely different way. Roland Recht states that seeing becomes believing in late medieval sensibility, and the arts were ‘progressively affected by a discernible change, namely, an enhancement of their visual value’ (

Recht 2008, p. 1).

Figural carving in ivory had a long tradition in China, and this rare material had been used to produce images of immortals, gods, and other figures before the thirteenth or fourteenth century (cited in

J. Park 2020, p. 77). From the Age of Navigation, ivory was generally acquired by the Portuguese in Mozambique and taken to Macau or other oriental centers, like Manila and Goa, to produce sculptures. Starting from the late 16th century, the production of ivory carvings developed mainly in Fujian Province, especially in Zhangzhou on the western coast of Fujian. There was a very profitable market in Haicheng, a district in Zhangzhou prefecture. Yue Port (Yue Gang) of Haicheng has always maintained its status as the only legal port in the country for private trade on the Maritime Silk Road in the late Ming and early Qing dynasties (

Li and Yang 1993, p. 515). A gazetteer dated 1628 for Fujian’s Zhanzhou Prefecture also indicates that ivory carving had become a prized industry by the early seventeenth century: “Elephant ivory can no longer be found in the prefecture and is wholly traded by those who come into the port markets. Zhangzhou people carve it into immortals and that sort of thing, supplying them for the purpose of providing pleasure. Their ears, eyes, limbs, and torso are all lifelike. Exceptionally skillful work comes from Haicheng” (cited in

J. Park 2020, p. 78).

The geographical location of Zhangzhou and its deep ties to maritime activity also shaped ivory carving in colonial Manila. In the mid-16th century, officials and local elites of coastal China pressured the central government, and in 1567 lifted a century-long foreign trade ban (

J. Park 2020, p. 72). Since Manila was located only ten days’ voyage from south Fujian, many Fujianese, merchants or nonmerchants, immigrated to this colonial city, from about 40 in 1570 to 150 in 1572 to more than 10,000 in 1588 (cited in

J. Park 2020, p. 73). Zhangzhou was the southernmost and nearest among the three great ports (the others were Fuzhou and Quanzhou) to Manila. By 1600, trade with China began to shift away from Fujian to Macau, as the bulk of Spanish silver flowed through the Macau port. Other luxury goods were obtainable from Guangzhou, which drew many talented artists to Portuguese-controlled Macau. Macau was both a production center and an emporium for export goods. Frequent trade and a large immigrant population make it difficult to identify the origin of the Sino-Portuguese ivory sculpture. For many Christian ivories made before the end of the seventeenth century, it seems fruitless to try to distinguish between Chinese artists working in Manila, Macau, Zhangzhou, Guangzhou, or elsewhere in China (

Onn 2020, pp. 636–37). Conversely, it also indicates that they were not only influenced by Sino-Portuguese relations but were also a product of multicultural and multireligious exchanges. As Clement Onn indicated, when dealing with cross-cultural, hybrid works of art, one often encounters ambiguity and a variety of perplexing nuances (

Onn 2020, p. 647).

Within a simplistic criterion, the four primary regional schools of the imaginary of the Portuguese East would encompass the Indo-Portuguese, the Luso-Ceylonese, the Sino-Portuguese, and Nipo-Portuguese productions (

Távora 1983, p. 8). Jessie Park mentions that scholars also have presented the ivories under two broadly conceived categories that stress stylistic characteristics developed within the confines of geography: “Hispano-Philippine” for objects believed to have been made in the Spanish Philippines (also known as “Fil-Hispanic”), Fujian, or Macao (also known as “Sino-Portuguese”), and “Indo-Portuguese” and “Singhalese-Portuguesa” to describe the objects ordered by the Portuguese and produced in major carving centers within the Indian Portuguese colonies of Goa and Ceylon (

J. Park 2020, p. 69). Manila and southeast China were the most important purveyors of ivory sculptures depicting Christian subjects, and academic research focuses on Hispano-Philippine-style ivory carvings and Zhangzhou ivory carvings. Jessie Park explored the early development of ivory carving and trade centered around colonial Manila from 1590 to 1640 (

J. Park 2020). Stephanie Porras tried to locate the novelty of Hispano-Philippine ivories in their exploitation of multiple points of reference, addressing markets and models across several oceans (

Porras 2020). Zhou Meng discussed the relationship between Hispano-Philippine ivory figures and Zhangzhou ivory carving (

Zhou 2021). Dani Putney demonstrated the Sino-Filipino Artistic Collaboration by analyzing the ivory sculpture production in seventeenth-century colonial Manila (

Putney 2022). Scholars realized those ivory sculptures cannot be identified with a single location and are freighted with a surplus of geographic vectors. However, past and present research has consistently focused on the Hispano-Philippine style of ivory sculpture. Besides, this categorization assumes where or by whom these ivory sculptures were made but lacks a fundamental understanding of the relationships of the commercial trade and has separated Spanish and Portuguese interaction (

Blackwell 2024, p. 34).

As Etsuko Miyata observed, the success of the ivory trade depended on the cooperation of Portuguese and Spanish traders, as the Spanish needed access to Portugal’s many trading posts for large quantities of raw ivory. The Portuguese needed access to Spain’s Manila galleons to transport the ivory to their American colonies (

Miyata 2016). The Portuguese were the pioneers of trade with Asia and the first missionaries in Asia. Portuguese traders and missionaries focused on Christianizing and converting local inhabitants to Catholicism throughout their colonies in Goa, Ceylon, Malacca, and Macau, among many others. Ivory sculptures are perhaps the most significant contribution Asia made to Christian art (

Chong 2016, p. 204). Sino-Portuguese ivory sculptures have rarely come into the light of research due to their rare quantity and complex identity. However, there is no doubt that their iconographic study can shed light on Sino-Portuguese trade relations, the influence of Christianity in China and other Asian regions, and the complexity of trade relations between Portugal and Spain.

3. Materiality, Visuality, and Religiosity

Materiality refers to the property of being related to or consisting of a material. It involves the use of ‘materials’ in making, forming, or creating a thing. Images and objects are not coded messages that deliver meaning, but rather social actors. The shift is not merely metaphorical but driven by the consideration of how materials interact with human beings. Rather than regarding artifacts as placeholders or tags of human intention, the material turn urges scholars to scrutinize the material affordances of objects—that is, what their features enable. This means learning about how images and objects operate culturally as material culture, as in the social process of religious conversion (

Morgan 2021, p. 649). Art history has much to learn from the interdisciplinary practices of material culture. One central revelation is that art has a physical, sensual dimension, not just a visual one. Objects may possess aesthetic appeal but also carry some more mundane, functional significance (

Yonan 2011, pp. 234, 243). Ivory sculptures were first portable, practical, and functional objects designed for personal devotional practices, and those with images of the Virgin and Child represented one of the most interesting dimensions of Christian art in China in its combination of the aesthetics and iconography of Christianity and other religions. In fact, in addition to the portable needs of individual missionaries, Catholic churches were erected at the end of the sixteenth century in Guangzhou, Macao, and other cities. Missionaries also ordered sculptures of the Holy Mother, Christ, and Catholic Saints to decorate churches and chapels and donations to monasteries, nunneries, and churches in Spain and Portugal (

Levenson 2007, p. 147).

Visuality means “the visual perspective from which certain culturally constituted aspects of artifacts and pictures are visible to informed viewers” or, put more bluntly, the element of visual experience that is contingent on culture. The term is a tool for getting at that most compelling and difficult of art historical questions: how did people in past or alien cultures perceive the objects we now study, what experiences and ideas grounded their viewing, and what, in the end, did they see? (

Sand 2012, p. 89). In the late Middle Ages in Europe, there was a shift in Christianity towards a “visible religion,” in which seeing was believed to reinforce faith and access to the divine. “Seeing strengthens faith” gave art the power of visibility in religion. Beyond the question of the vision of God, Nicolas of Cusa establishes numerous debates about visibility in general and several questions concerning the icon as a type of phenomenon. The gap between the physical vision of the image put into a painting (

figura,

imago,

facies subtili arte pictoria, and

tabella) and the icon’s aim (

visus iconae) thus structures the entire experience in praxi and therefore the entirety of De visione Dei (

Marion 2016, p. 311). Augustine thinks three existing visions exist: the first is the

visio corporalis, the literal sight of the eye or, more generally, knowledge using the external senses; the second is the

visio spiritualis, or imaginative knowledge using the imagination; and the third and highest of the classes of vision is intellectual, the direct intuition of God Himself (

Newman 1967, p. 59). The last one, intellectual vision, is, in fact, a pivotal concept in Augustine’s philosophy.

Missionaries, especially the Jesuits, understood the importance of materiality and visuality during their evangelization. According to missionary sources, the most used subjects were the Savior (a half-length portrait of Christ). However, the images of the Virgin Mary were especially popular in Chinese missions. Due to the blurred line between the Virgin and Guanyin, the Chinese adoration of the figure of Mary came with the unfortunate corollary that Jesus was neglected. Moreover, in accepting the Mother of God, the Chinese tended to forget the Son of God, who should have been the more prominent figure (

S. Park 2020, p. 3).

Before Matteo Ricci, Michele Ruggieri (羅明堅, 1543–1607) played a crucial role in the early Jesuit Mission and introduced Matteo Ricci to China. Unlike Ricci, who adopted the persona of a Chinese scholar, Ruggieri maintained his identity as the ‘foreign monk’, converted Chinese by accommodating to Buddhism, and thus published the Tianzhu Shilu, the first Catholic work in the Chinese language, under his Chinese name Luo Mingjian (

Hsia 2010). During a banquet with Wang Pan (jin shi degree 1572), Zheng Yilin, and their colleagues, Ruggieri presented Zheng with a picture of the Madonna and Child. Zheng was so impressed by the picture that he spontaneously promised Ruggieri to accompany him on his journey to Peking. However, Zheng took Ruggieri to his hometown, Shaoxing, instead of Peking, considering the inconvenience of bringing foreigners to the imperial capital (

Hsia 2010, p. 3). In addition, in his letters of 1580 and 1584, Michele Ruggieri also stated that he hoped Rome would send paintings illustrating the life of Jesus and prints of the Virgin and Child, as they were beneficial for explaining doctrine (cited in

Chen 2013, p. 15).

An anecdote from 1583 in Ricci’s diaries registers about a Madonna image placed on an altar in Zhaoqing and the reaction of Chinese believers: “Everyone, in short, paid reverence to the Madonna in her picture above the altar, with the customary bows and kneeling and touching of the forehead to the floor. All of this was performed with an air of real religious sentiment. They never ceased to admire the beauty and the elegance of this painting: the coloring, the very natural lines, and the lifelike posture of the figure”. This would be the first record of the response of the Chinese people to the image of Madonna with Child (

Chen 2013, p. 7). However, when Ricci believed that the Chinese might confuse the difference between the Virgin Mary and God and consider God to be female, he suggested replacing the picture of the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child with one of Christ the Savior (

Gallagher 1953, p. 155). It exemplifies the visual function of icons as a universal language and the different interpretations of the Chinese. The dual meaning of the iconography of the Madonna and Christ Child was incomprehensible to the Chinese mind, which also caused several problems for the missionaries.

Between 1599 and 1600, Manuel Dias (李瑪諾, 1559–1639), as the rector of the College of the Madre de Deus in Macau, prepared gifts for the Chinese emperor, including a large and exquisite statue of the Virgin Mary in Santa Maria Maggiore style, which was sent from Rome. This gift list is also the first record of the appearance of the Virgin Mary in the Chinese missionary district (

D’Elia 1949, pp. 230–31). Moreover, in 1601, Matteo Ricci arrived in Beijing. He successfully presented “valuable European items” to Emperor Wan Li, including “a painting of Jesus, two paintings of the Virgin Mary, a copy of the Lord’s Prayer, a precious inlaid cross, two chiming clocks, a gazetteer map of the world, and an elegant zither” (

Wang 2007, p. 142). Matteo Ricci describes the painting as “a huge image in the form of St. Maria Maggiore, brought from Rome and well painted (una imagine molto grande della forma di S. Maria Maggiore, venuta di Roma et assai ben pinta)” (

D’Elia 1939, pp. 31–32). When the emperor saw two images of the Virgin with Child, he reacted spontaneously identically to their technical level and remarked acutely, “Questo è Dio vivo” (

D’Elia 1949, pp. 123, 125). The emperor inadvertently revealed the truth: the statues they worship are all lifeless. In the meantime, it also reveals the profound visual effect on Chinese sensibilities.

In addition to the conversion of ordinary people, the power of images in the literati class should not be underestimated. Xu Guangqi (徐光啟, 1562–1633; baptized as Paul in 1603) had several experiences in which he viewed Christian images, which would affect his path to conversion. In 1576, Xu met the Jesuit Lazzaro Cattaneo (1560–1640) in a chapel of Shaozhou and first saw an image of Christ (Salvatore; savior type) from Rome. Moreover, when he was baptized in Nanjing in 1603, João da Rocha (1587–1639) showed Xu an image of the Madonna with Child in St. Luke’s style, and Xu was so moved by beholding the Holy Mother image that he asked the Jesuit to introduce him to Christianity and later decided to be baptized (

Chen 2010, p. 77).

In 1627, the Jesuit Rodrigo de Figueiredo (1594–1642) had his altar set up and his devotional painting displayed, and he commenced proselytizing. He stood before his altar, kowtowed repeatedly before the image of the Savior, and invited his audience to do the same. Moreover, he said to Chinese Christian followers about the portrait, the one “the Creator of everything, neither a pagoda nor an idol, but the true and living God” and enjoined them “not to worship other gods or to fear demons, but to serve the one true Lord.” (

Brockey 2007, p. 307).

Though the Christian missions to China had started as early as the seventh century, it was not until the seventeenth century that the images of Christ and Mary gained unprecedented visibility. Especially after the publication of Cardinal Gabriele Paleotti’s remarkable treatise Discourse on Sacred and Profane Images in 1582, this archbishop of Bologna confirmed the power of art in his orthodox Roman Catholic position. It ensured that sacred and profane art would move viewers away from vice and towards virtue and knowledge of God. Most Virgin and Child images were based on the portrait attributed to Saint Luke, called the Salus Populi Romani, at the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome.

The above examples reveal the importance of religious images in missionary work in China and prompt some thinking. The Catholic missionaries, especially the Jesuits, brought sacred images from the very beginning, and at the same time, they needed to learn the local language to explain images to be understood in the correct sense; that is, non-verbal images could not be substituted entirely for what language can convey, which also met their accommodation policy. Visual objects could be used in evangelical activities, especially on some specific occasions, thus implementing effective communication via visuality.

Although religious images’ function differs from pure aesthetic appreciation, it often relies on outstanding aesthetic effects to achieve a transcendental religious experience. An extraordinary visual impact is often a prerequisite for the smooth progress of missionary work. Moreover, Western techniques such as perspective began to play a role in these images to achieve realistic visual effects. The reaction of the Wanli Empire to the images highlights the “real” effect accomplished by technical achievement rather than the understanding of the sacred content.

The images of the Virgin and Child not only had a missionary function but also served as gifts for cultivating a friendship with the Chinese. In the process of religious function and material and cultural contact, the image of the Virgin and Child conveyed multiple understandings from different cultural views. They contained sacred meaning for missionaries using their visual function, and they were often regarded as secular objects by non-Catholic Chinese. The missionaries felt gratified that their devotional objects fit so readily into the symbolic context of Chinese religious practice. Furthermore, in this cross-cultural preaching, the devotional objects transcended their materiality and forged a Chinese Christian identity through their visuality. The Catholic missionaries, especially the Jesuits, imported varied types of devotional images from Europe, and meanwhile, they ordered Chinese craftsmen to make devotional objects to facilitate proselytization and propaganda. The following piece is one of the most representative.

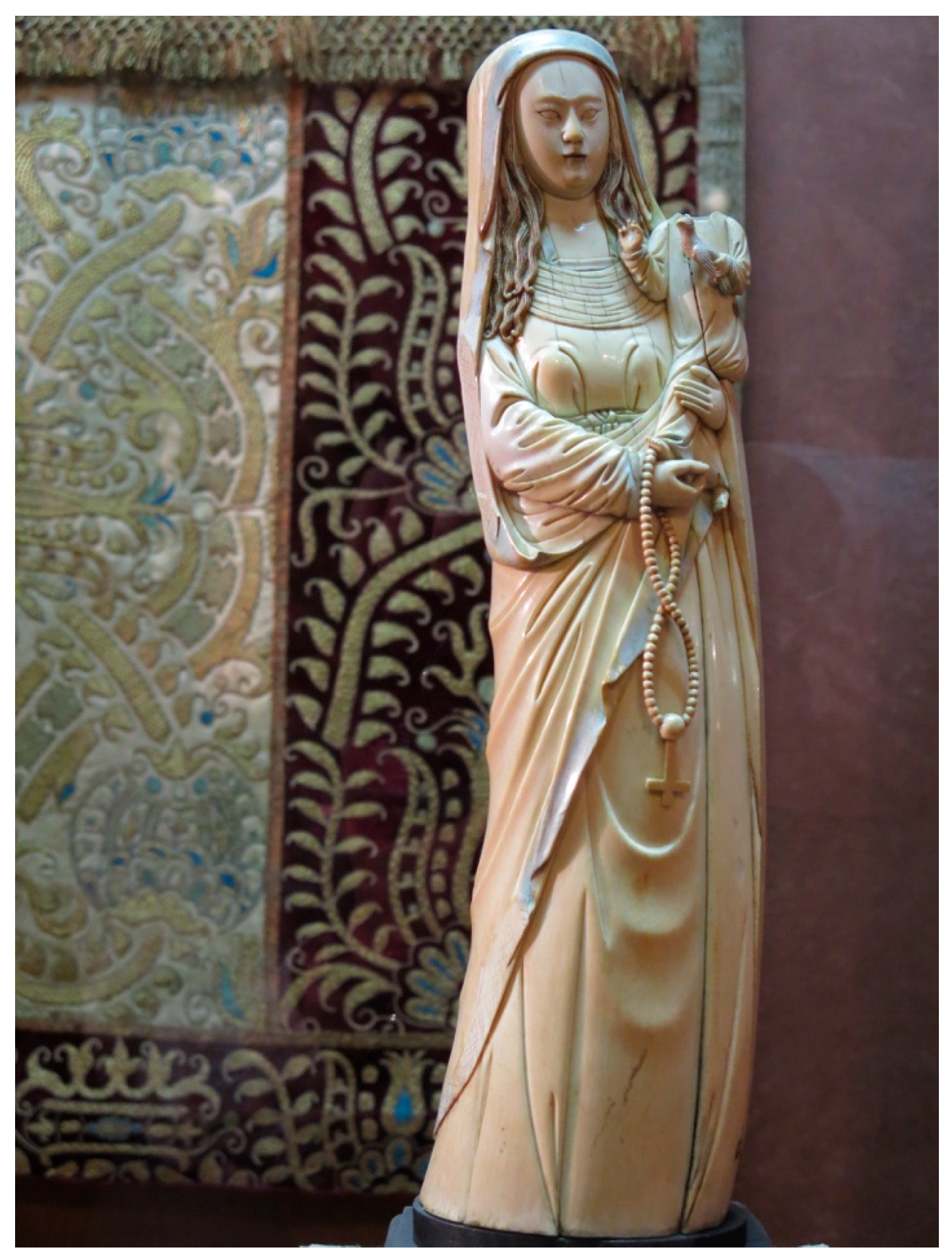

This sculpture (

Figure 1) represents the outstanding skills of Chinese ivory carvers in the late sixteenth century or the early seventeenth century. The larger-scale devotional sculpture (height 43 cm), the depth of the carving, the graceful movement, the care of the drapery, and the portrait of facial features are unparalleled.

The image of the Virgin with the Infant Jesus is delicately carved from ivory and stands on a wooden pedestal. The Virgin wears a straight-necked shirt and a tunic with a round pleated neckline cut below the chest. The cloak covers her head, falls over her back, and is gathered at the side in a pleated flap under her left arm. Her hair, in vast waves, reaches down to her shoulders. The back is worked with sculpted vertical pleats that widen from a deeper inverted V-shaped horizontal pleat. A beaded rosary, which is topped with an inverted Latin Cross, hangs from the Virgin’s wrist. Bernardo Ferrão de Távora summarized the characteristics of the clothing of the Virgin and Child. The basic costume consists of two pieces: a robe down to the feet, with long sleeves and a cinched neckline, fastened by a belt with a front loop, and a cloak draped over the shoulders, the ends of which are caught under the left forearm, the right one rising to cross diagonally in front (

Távora 1983, p. 37).

The figure is carved with detail and sensitivity from a single piece of African ivory. The overlapping garments are rendered with elegance and believability, contributing to the Virgin’s grace and accentuating the body’s forms. The sculptural figure establishes a sense of rhythmic balance through the interplay of the drapery, which falls precisely. Such artistic techniques had been perfected in earlier Chinese sculptures of the Buddha and Bodhisattvas.

In a very graceful representation, the figure of the Virgin, taking advantage of the natural curvature of the elephant tusk, is structured along a diagonal axis that emphasizes the sinuosity of the pose. The carver carved her standing slightly inclined to the right, thus highlighting the expressive inclination of the veiled head, prolonged in the movement of the left leg, which seems to be presenting “Contrapposto” and thus gives the Virgin a certain flexibility and elegance. She holds the Child dressed in a tunic in her left arm and supports his feet with her right hand.

Although the Christ Child’s head is now missing, his hands and lower body show many details. The playful Christ Child has caught a bird in flight. The bird symbolizes the soul and its resurrection. The bird nourishes itself on the blood of Christ, an act that refers to the Eucharist. The Christ Child is shown as Salvator Mundi (Savior of the World). He makes the sign of the cross with his right hand, blessing the viewer.

Now, let us turn our attention back to the depiction of the Virgin’s face. The treatment of the Virgin’s face shows strong Chinese characteristics. Her face is oval, with willowy arched eyebrows, a small cherry mouth, and a flat nose, showing a peaceful smile. The articulation of the face with slightly pouting lips, the conscious treatment of drapery, and the wavy hair all point to the hand of a Chinese carver who may have understood but thoroughly transformed the classical style. The museum’s data about this sculpture tells us it follows the model of Guanyin, Buddhism’s secondary deity. It was carved in China for a Christian clientele. This type of image was exported from Macau (1557).

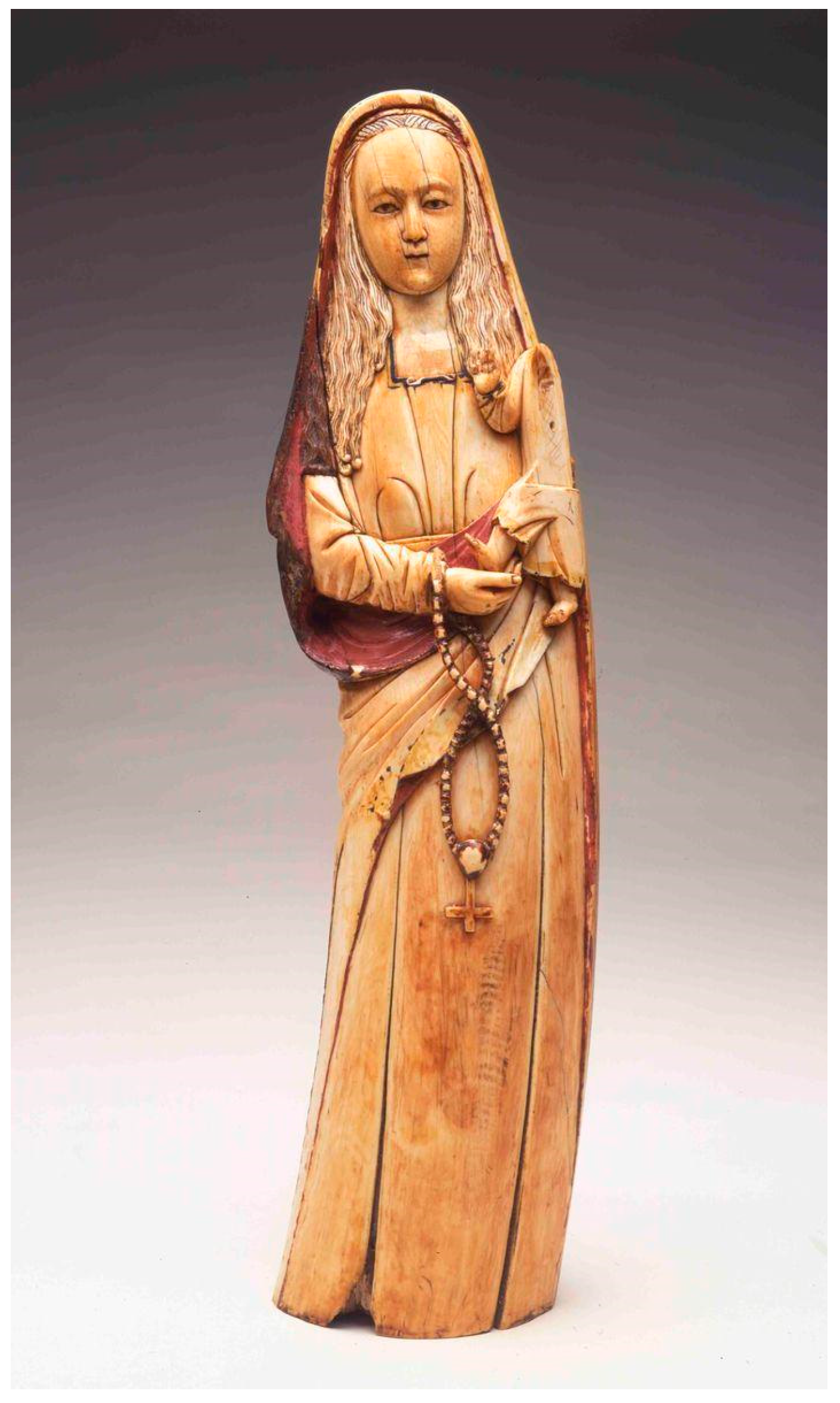

An ivory sculpture of the Virgin and Child (

Figure 2), very similar to

Figure 1, is in the collection of the Hispanic Society Museum. The Virgin’s oval-shaped face, with its tiny mouth and chin, closely reflects a sensibility associated with Chinese carving. And in pose and facial features, this sculpture exhibits similarities to Chinese renderings of the deity Guanyin. However, the museum’s data for this object shows the Philippines as the place it was made. There is no direct evidence of Chinese artisans producing Christian devotional objects in China, regardless of the efforts by the Jesuits to establish Christianity there. However, artisans within the Chinese merchant community in the Philippines actively produced devotional works for Spain’s worldwide network of colonies. Távora also mentioned this ivory sculpture (

Távora 1983, p. 81) and explained that as for the Sino-Portuguese Virgins, their attribution of carvers involves difficulties arising from the fact that the authors of the similar Hispano-Filipino images and the similarity with the representation of Guanyin, an androgynous deity and later feminine manifestation of the Bodhisattva Avalokiteçvara, covering the appearance of a young woman involved in drapes, holding a child in her arms, and holding a rosary of beads.

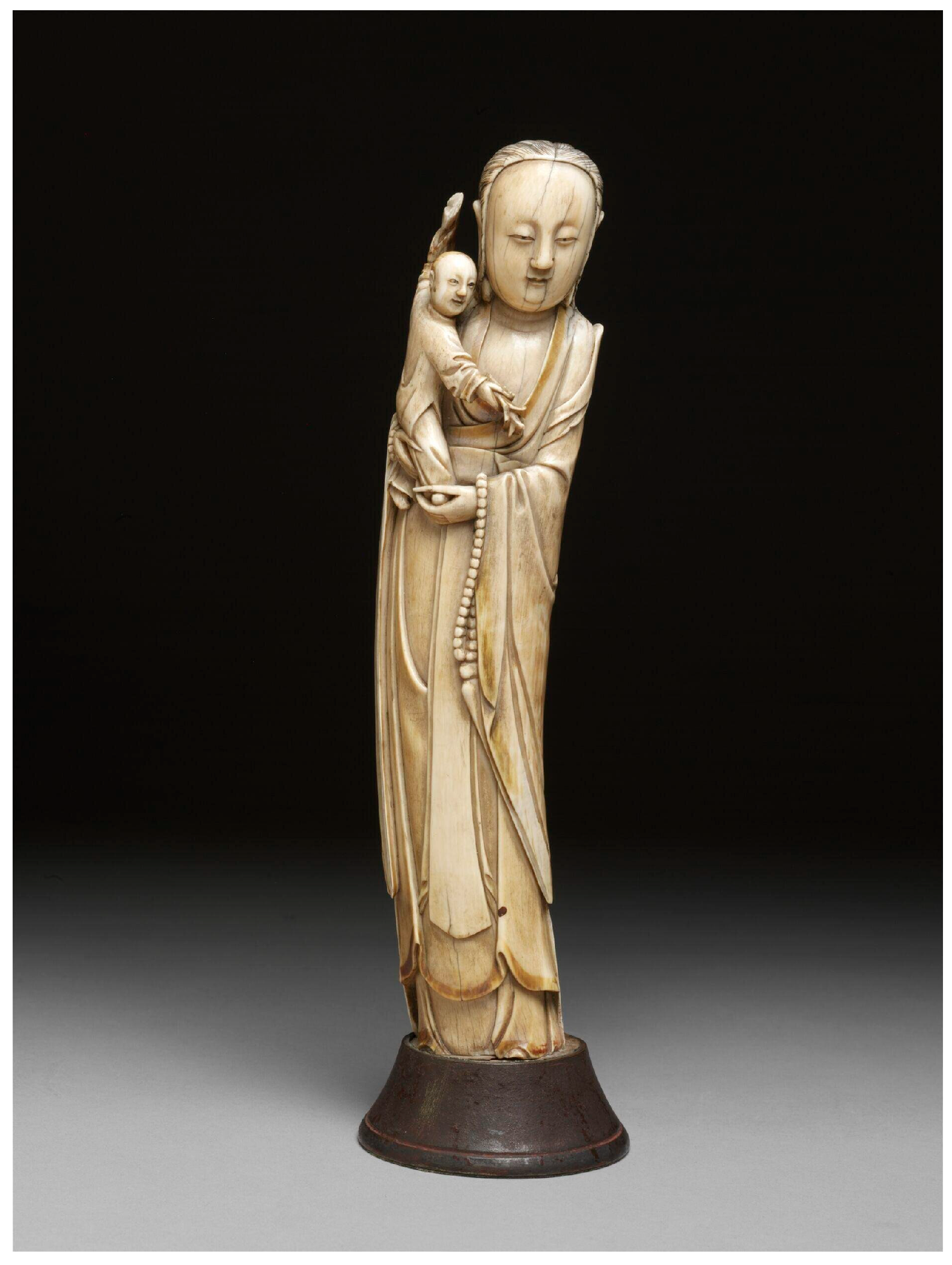

The Victoria and Albert Museum has an ivory sculpture with its gallery label [Guanyin the Bringer of Sons] (

Figure 3). According to the museum’s data, Guanyin wears a long flowing drapery with a row of beads over her left wrist. Moreover, the child Zen Zai is on her right shoulder, supported by both her hands, wearing a tunic and loose trousers, and holding a spray of leaves in his right hand. Moreover, the convention of representing Guanyin with a child was influenced by the Christian iconography of the Virgin and Child imported by the Spanish and Portuguese. Let us compare this Guanyin, the Bringer of Sons sculpture, with the Virgin and Child in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2. It can be observed that there is no noticeable difference in the body posture and facial expression of the female figures. However, a row of beads in Guanyin’s hand has been replaced by the cross in the Virgin Mary’s hand, and a spray of leaves has replaced the bird symbolizing the resurrection in the Christ Child’s hand.

Formal similarity is the reason for the overlapping identities that can be made between Guan Yin and the Virgin, and we can determine their cultural identity through these iconographic substitutions of details. When sculpting the Virgin and Child, the carvers choose to slip in Guanyin-like features, taking advantage of the ambivalent culture to offer a “similar, but not quite” representation of the popular Marian image that would satisfy the Catholic religious goals but maintain a sense of agency in terms of portraying aspects of more familiar cultures (

Bhabha 1994, p. 122).

4. Interaction Between Images of the Virgin and Child and the Songzi Guanyin

Guanyin and the Virgin Mary were depicted as the intercessors between the two cultures, and they shared many similarities in iconography, miraculous life, and worship patterns (

Song 2008, pp. 117–18). Historical accounts register that those early Christian missionaries themselves had confused Guanyin’s image at first sight with that of the Virgin Mary (cited in

Spence 1985, p. 250).

Guanyin (觀音), also known as Guanshiyin (觀世音), is the name for Avalokiteshvara, the Bodhisattva of Infinite Compassion. The translation comes from the Sanskrit “Avalokita,” which means to observe (觀 [guan]), and “svara,” which means sound (音 [yin]). In other words, the Bodhisattva is “the sound-perceiver” or the one who hears the sounds of the world (世 [shi]). It points to her unconditional compassion to save all sentient beings who need her help in this miserable time. In general, the gender of deities in Buddhism is neutral and rarely discussed. Early depictions show Avalokiteshvara as a noble, male-looking Bodhisattva, and the female form became more popular later in Mahayana Buddhism, particularly in China. By the late Ming dynasty, Avalokiteshvara had completely transformed into a feminine deity for all Buddhist believers.

During the late Ming, the feminized image of Guanyin absorbed various forms and elements from Chinese culture and enjoyed a vigorous evolution in terms of iconography and devotion. One of her most popular Indigenous iconography during this period was the “White-robed Guanyin” (白衣觀音 [Baiyi Guanyin]), which was depicted as a middle-aged woman wearing white robes and holding a baby in her hands or placed on her lap and which was associated with the petition for male heirs, thus giving Guanyin the name of the “Child-giving Guanyin” (送子觀音 [Songzi Guanyin]). The white color of the mantle carries this symbolic implication of the maternity of the deity (

Chen 2013, pp. 12–13). The Child-giving Guanyin was mentioned in the “Universal Gateway” chapter of the Lotus Sutra (妙法蓮華經). This ancient Buddhist scripture describes how Guanyin uses skillful means to help living beings reach the shore of liberation. Also, Gu Yanwu (1613–1682), a Confucian scholar living in the Ming and Qing transition period, noted in his book Random Notes Taken Amid the Reeds (菰中隨筆 [Guzhong Suibi]) that “Among the deities who enjoy the offerings of incense in the temples and monasteries under heaven, none can compete with Guanyin. The Great Being has many forms of transformation. However, people mostly worship that of the White-robed One.” (cited in

Song 2008, p. 103).

Alexander Soper Coburn pointed out that the word “Guanyin” was originally “Guangshiyin,” which becomes a being whose “voice illumines the world”, and that in early Christian texts, the symbol of “light” was closely associated with God. The formation of the early Guanyin belief should have been influenced by the Nestorian Christianity (景教 [jingjiao]) that was introduced to China in the Tang dynasty (

Coburn 1959, pp. 158–59).

The earliest surviving statue of the Virgin and Child in China is the gravestone of Katherina Vilionis of 1342 in Yangzhou. Lauren Arnold indicates a melding of medieval Christian iconography with traditional Chinese motifs on its carving, and the tombstone was Franciscan relics, which depicted a seated Virgin and Child of the

Sedes Sapientiae type favored by the Franciscans. He also considers that this Madonna and Child image borrowed many subtle details, such as the enlarged halo, from a Chinese folk goddess and may have influenced the evolution of Chinese Guanyin iconography. Moreover, his research suggests that the Franciscan Virgin of Humility may have inspired the iconographic depiction of the Child-giving Guanyin, and their iconography overlapped, likely linked to the Franciscan’s advantage regarding converts (

Arnold 1999).

Another well-discussed Chinese Marian image is the Chinese-style copy of the Madonna icon of Santa Maria Maggiore. The painting on silk scroll was found in Xi’an (西安) in 1910 and is now housed in the Field Museum of Chicago in the United States. Through a visual comparison, Chen indicates that this Madonna with Child is related to the Roman icon the Jesuits brought to China in the late sixteenth century and to the Buddhist white-robed Guanyin iconography. This reformulation of the Madonna image was made to suit the Chinese visual discourse (

Chen 2018).

There were reasons for the interaction between the images of the Virgin Mary and the Songzi Guanyin. Furthermore, the parallel between the worship of the Virgin Mary and the belief in Guanyin was not a haphazard episode. Coastal provinces like Fujian were visited by Jesuit missionaries who commissioned local carvers for ivory sculptures of the Virgin and Child. They were impressed by the resemblance between the Child-giving Guanyin and that of the Madonna and Child. Their images were often interchangeable. It is worth noting that for establishing meaningful similitude, the coincidence of the iconographies of Guanyin and the Virgin lies not only in visual correspondence but also in their content, such as compassion, mercy, purification, and child-giving power. The Virgin Mary with Child was adapted for their intended audience. The missionaries consciously blended the image of the Madonna and Child into Chinese culture by using the similarities in iconography and symbolic patterns.

Moreover, the Bodhisattva and the Christian deity were engaged in invisible yet realistic competition (

Song 2008, p. 117), in which the political and social situation in China, religious policies, and the religious situation, as well as the missionary strategies of Western missionaries, constantly influenced its progress. When the audience of a different culture and language perceived their visual similarity, there was confusion between the Virgin and Child and the Songzi Guanyin. The ivory sculpture of Guanyin holding a child raises a question of visual identification, as it could be confused with the Virgin with Child. On the one hand, missionaries intentionally exploited visual similarity for missionary purposes, while on the other hand, it caused problems for missionaries.

Matteo Ricci (1552–1610) and his fellows arrived in China and presented Marian iconography and other fantastic objects to the Chinese audience. In his journal, later published by Nicolas Trigault (1577–1628), and his letters to European correspondents, Ricci recorded that some Chinese converts had visions of the Virgin Mary, wearing a white robe and holding a child, who miraculously saved them from serious diseases. These accounts did not fit the dominant icon of the black/robed Madonna (

Song 2018, p. 107). Ricci did not clarify that the Holy Mother often dressed in black instead of white, nor did he forbid the converts from circulating those miracles and dreams. However, in the latter half of the account of 1583 from Zhaoqing, Matteo Ricci reported that the Chinese interests resulted from the skill and technique of the painting but also their shocking conception of God as a female (

Chen 2013, pp. 7–8). Matteo Ricci removed the statue of the Virgin Mary and replaced it with a statue of God. Some Christian converts burned statues of Guanyin, the Buddhist goddess of mercy, along with other images, and perhaps with an added urgency, since even Christian missionaries themselves had confused her image at first sight with that of the Virgin Mary (cited in

Spence 1985, p. 250).

In Nanjing, it was commonly believed until the end of the 16th century that “God” was a woman holding a baby. Jonathan D. Spence believes that it is likely that during the introduction of Christianity to China during the late Ming Dynasty, Matteo Ricci did not immediately stop the spread of this misunderstanding because the influence of images of the Virgin Mary in their missionary work was too significant (

Spence 1985). Moreover, Gauvin Alexander Bailey also states that Ricci and his successors went on to capitalize upon the Madonna/Guanyin phenomenon and consciously employed the Songzi Guanyin to provide a link to the Virgin and Child, which is why the Virgin became such a typical image in Macao and China (

Bailey 1999, p. 89). The Chinese understood and adopted the Virgin and Child image not because of any comprehension of the Christian subject or religious doctrine, but because of the similarity in appearance and doctrine to the Guanyin they were familiar with. Conversely, missionaries who commissioned objects also used this understanding (or misunderstanding) to achieve missionary goals. They recognized the confusion between two female deities but did not correct it forcefully or consistently. If the fusion did not lead to “dangerous idolatry,” they tolerated this “amicable” misunderstanding (

Song 2008, pp. 105–7). Thus, this complicated interaction and transformation fostered accommodation, appropriation, and assimilation. Furthermore, the processes of cooperation, acceptance, confrontation and rejection, dialogue, and imposition led to the creation of new relational spaces and identities.

An ivory sculpture (

Figure 4) collected in the State Hermitage Museum is perfect material and visual proof of this interaction between the images of the Virgin and Child and the Songzi Guanyin. This piece is an important and rare example of a Christian model inspired by this artistic symbiosis that links Chinese goddesses with the Virgin Mary. The exquisitely carved mother and child sculpture, devoid of any exact identifying attribute, might have appealed equally to Chinese and Western viewers. Moreover, Buddhist and Christian believers would have interpreted it in different ways. For Buddhist believers, Guanyin is shown seated with a boy on her left thigh. Guanyin was carved with a high forehead, half-closed eyes, and a wide nose, showing a serene and mystic expression. Her face is rounded like the full moon, and the earlobes are oblong. Her stylized and extended right hand rests on her lap, with elongated fingers in the Chinese manner. The baby is bareheaded with oblong earlobes and a physiognomy like his mother’s. Moreover, this ivory sculpture shows a moment of contemplation, with a spiritual link between mother and baby. Levenson indicates that the figure’s interpretation and shape do not produce a feminine impression and hark back to Buddhist iconography and to the Chinese painted images and sculptures (

Levenson 2007, p. 148). However, for Christian believers, this seemingly straightforward image of the infant Jesus seated rigidly on the Virgin’s lap represents a complex, medieval theological notion known as a

Sedes Sapientiae (Throne of Wisdom), in which Mary serves as a throne for Christ, who in turn embodies divine wisdom.

Levenson registers, as for this rare Sino-Portuguese sculpture in ivory, the soft carving style, broad face, and rich drapery of the holy mother figure are characteristic of Late Ming carving and were performed by a native Chinese craftsman, showing a characteristic treatment of the folds and body contours. Such depictions of Mother and Child were uncommon for Chinese religious sculpture and may have been carved as an image of the Virgin and Child for a Portuguese commission (

Levenson 2007, p. 148). The Madonna and Child Enthroned (

Virgem em Majestade) is a poorly diversified group, an archaic revival of the model that was common in Portugal in the 15th century but disappeared entirely in the 17th century, replaced by the Immaculata, a creation of the Spanish Baroque (

Távora 1983, p. 36).

However, it seems possible to trace the prototype of this Sino-Portuguese ivory sculpture (

Figure 4) in many 13th-century European paintings and statues (

Figure 5). The Enthroned Virgin and Child composition is loosely based on the Hodegetria, one of the more powerful and enduring icon types of the Orthodox Christian church. The Byzantine painting (

Figure 5a) shows the Virgin seated on an elaborate wooden throne with openwork decoration. She supports the blessed Christ child on her left arm. We can see the abstracted style of Byzantine icons here. The ivory sculptures of Enthroned Virgin and Child (

Figure 5b,c) are French and were produced at a time when Paris was the principal European center of ivory carving. Moreover, these two ivory sculptures date from the height of the popularity of the cult of the Virgin. Our Lady’s face is delicately sculpted, creating an atmosphere of tenderness as she smiles and interacts with Christ, giving the impression that she is a loving mother rather than a Queen of Heaven.

Equally, let us compare Guanyin with a Boy in carved ivory (

Figure 4) with the European Enthroned Virgin and Child prototype. It is possible to observe the remarkable similarities in their forms and structures. However, if we compare the two, we can see not only a remarkable similarity in form but also a similarity in their function as worship iconography. Icons assume a communicative function; they elicit emotion and sympathy from their believers through empathy, sharing the presence of divine power in the believers’ perception of similarity. Both the Guanyin sculpture and the European sculptures of the Virgin and Child emphasize the motherhood of the Virgin as a means of allowing the believers to engage in their subjective emotional projections and dialogues with the sacred objects, thus facilitating conversion. Thus, Marian’s devotion to competing with Guanyin’s belief also offered an additional method to convert the Chinese to Christianity.

5. Hybridity and Interpretation

According to museum records or expert introductions, the three ivory sculptures discussed in the article are all Sino-Portuguese ivory sculptures (

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 4). It is common to find representations of the Virgin as Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception in Asian-Portuguese imagery. For Sino-Portuguese imagery, three factors were essential to the artistic ties between China and Portugal: the existence of the

Padroado Real (Royal Patronage), the importance of Macao (

Levenson 2007, pp. 141–42), and the trade between Zhangzhou and the Philippines.

The Portuguese Padroado dates from the beginning of the Portuguese maritime expansion in the mid-15th century and was confirmed by Pope Leo X in 1514. The Padroado Real enabled the missionaries to control religious activities extensively in China and other regions. In the seventeenth century, Macao became a commercial, maritime, and multiethnic city. After the establishment of the Diocese of Macau in 1576, Catholic orders such as the Jesuits, Franciscans, Augustinian Canons, and Dominicans successively stationed themselves in Macau, using Macau as a base to send missionaries and supplies to China, Japan, and other places. In the seventeenth century, Macao became a commercial, maritime, and multiethnic city. More complicatedly, Mazu (媽祖), considered a transformation of Guanyin, was the local deity in China who protected sailors and was well known by Portuguese traders and missionaries in Macau, giving rise to a distinctive worship system of the sea god in Macao. Thus, the connection between Mazu, Guanyin, and the Christian Virgin in Jesuit iconography for China could not be neglected (

Chen 2013, p. 21).

In 1565, Miguel Lopez de Legazpi conquered the Philippines and established its capital in Manila. Since then, the Spanish have performed business with the Chinese, mainly from Zhangzhou, and the Fujianese have also begun emigrating to the Philippines. The Spanish and Portuguese commissioned an enormous number of ivory images of the Virgin, which were produced in the Philippines. Within this commercial discourse, the commissioned ivory sculptures were from the same group, and ivory Guanyin sculptures were also carved for the Chinese market. Even with distinct Chinese styles or characteristics, determining whether it was made in Zhangzhou or the Philippines is often impossible. At the same time, some sculptures also have indistinguishable fusion characteristics that the West, Chinese culture, or the Philippines may have influenced.

Due to the above three important historical factors, Sino-Portuguese ivory sculpture generally has two prominent characteristics: simplification and hybridization.

According to Távora’s study, the Luso-Eastern ivory sculptures of the Virgin, based on their respective characteristics, mainly come from three areas where historical Portuguese evangelization intensified: India, Ceylon, and China (

Távora 1983, p. 35). With the inaugural voyage by Vasco da Gama from Lisbon to Calicut in 1498, Portugal established its relationship with India. Then, following the conquest of Goa by Afonso de Albuquerque, for over 300 years, Goa remained an important commercial center. Portugal contacted Sri Lanka in 1505 and established permanent trading ports there in 1517. And ivory devotional sculptures were produced in large numbers in Portuguese India and in Portuguese Sri Lanka (formerly called Ceylon), assisting in the presentation of Christian imagery, as well as being exported back to churches, convents, and private collectors in Europe, thus presenting the global history of humankind as a narrative of intersections and exchange. However, compared with similar sculptures of the Virgin and Child carved in India and Ceylon, the three representative Sino-Portuguese ivory sculptures mentioned stand out for their simplified modeling, with neither embellishment in other colors nor excessive decorations. It seems that Chinese carvers wanted to simplify and stylize forms to create a more expressive quality and highlight the holiness and purity of the Virgin Mary or Guanyin.

This peculiarity of simplification and stylization could be explained by enforcing the decrees from the Council of Trent (1545–1563) in Portuguese Asia. The worship of religious images was advocated for greater simplicity and dematerialization in favor of a return to spiritual content and a deeper, unobstructed religious faith. Moreover, suppose we associate the characteristics of Portuguese painting from this period (mannerist style or stylish style). In that case, we will also find similarities in the oversimplification (in Portuguese, despejo) with Sino-Portuguese ivory sculpture.

The Portuguese- or Spanish-commissioned Christian figures carved in ivory were not mere copies of established European types but also innovative amalgams of style and form. Asian carvers employed local skills by adjusting to European norms regarding sculptural tradition and iconography and, more significantly, creating some standard stylistic features within their interpretation. However, the identities of the ivory carvers were never discussed, or perhaps they are not even Christians, since the ivory sculpture has undergone a process of continuous circulation, which involves a tacit acceptance of sources from Christian Europe, internalization of unfamiliar forms and iconography, and culturally informed interpretation of European elements (

J. Park 2020). This “local” interpretation of the “European” inevitably leads to an artistic hybridization.

By observing the Sino-Portuguese ivory sculptures of the Virgin and Child, the facial contours of the Virgin were generally Sinicized, with almond-shaped eyes, elongated noses, heavy eyelids, and wavy hair flowing neatly. However, several decorations, such as a beaded rosary and a Latin Cross, could be an exotic touch to Chinese viewers. Derek Gillman states that Fujian ivory figure models were successful and popular precisely because of their novelty value and foreignness, which appealed to a South Chinese community busily engaged in overseas trade (

Gillman 1984). However, the acceptance of novelty is based on the Chinese carver’s “familiarity” and cultural interpretation. It was neither clumsiness nor oversight, but a deliberate choice intended to emphasize the foreign origin of the new religious doctrine (

Levenson 2007, p. 147). In the interaction between the Virgin Mary and the Songzi Guanyin, the Virgin Mary, as understood by the Chinese, has become a unique image with Chinese identity, promoting the localization of Christianity. The ivory sculptures ordered by the Portuguese and made by the Chinese were inevitably in hybrid forms. The characteristics depicted on the Sino-Portuguese ivory sculptures also reflect that artist and cultural exchanges are not one-directional transmissions but rather a more complicated process of hybridization.

However, Carolyn Dean and Dana Leibsohn state that the perception of hybridity is generated from the contexts in which things circulate and the settings in which mixed arts are performed or practiced. The object of hybridity is not an

objet d’art. Instead, it is the stories we choose to tell (

Dean and Leibsohn 2003, p. 26).

6. Conclusions

The Sino-Portuguese ivory sculpture of the Virgin and Child presents a fusion of materiality, visuality, and religiosity. The origins of Sino-Portuguese ivory sculpture interrelate with the Portuguese missions in the Orient, which faced a shortage of portable objects for devotional purposes; thus, the Portuguese and later the Spanish commissioned pieces from local carvers. Then, the ivory sculptures played an important functional role in accommodating religious strategies, facilitating missionary work, and conveying the unintelligible Christian doctrine to newly converted Christians. During this process, ivory sculptures, icons worshipped by Chinese Christians, were exchanged as secular gifts with the Chinese and were a vigorous method for missionaries to preach the gospel.

The image of the Virgin Mary interacted actively with the Chinese visual discourse of Songzi Guanyin. The Chinese response highlights the material function and visual effect rather than its sacred contents. Western missionaries also made full use of this feature of materiality and visuality, paying much more attention to whether and how the objects and images streamlined intercultural and interreligious communication, thus fulfilling their ultimate religious purpose. Whether it was the local understanding of Chinese carvers or the missionary purpose of Europeans, the ivory sculptures ultimately took on an artistic hybridization.

The scene of a mother holding her child, whether presented on a sculpture of the Virgin and Child or the Songzi Guanyin, is undoubtedly a product that transcends cultural and religious differences while taking on specific connotations among their respective audiences. Whether it was intentional borrowing of the iconography or the worship patterns of Guanyin, or whether Chinese carvers unintentionally confused the two, this complex cultural and religious encounter was not a linear cause-and-effect relationship but a kind of “tangled network through continuous appropriation and competition” (

Song 2008, p. 117). The images underwent adaptation and enrichment with local contributions, which have been inspired by the sculpture models brought from Europe and the carver’s interpretation and cultural connotation.

In a single Sino-Portuguese ivory sculpture, multiple meanings coexist in concordance without overcoming each other. The image of the Sino-Portuguese ivory sculpture of the Virgin and Child can be seen as establishing a free interaction between the “Chinese” and the “European”, the “sacred” and the “profane”, and the “Buddhist” and the “Christian”. The Sino-Portuguese ivory sculpture of the Virgin and Child plays the role of a “middle space” by providing legible visual forms in both Chinese and Christian contexts, thus facilitating the mutual understanding and interaction between different cultures and religions.

Michael Yonan states that we look at images, spectral traces of some reality. Images require deciphering, and how images operate in our eyes and minds is the process by which we locate their meanings (

Yonan 2011, p. 235). The European missionaries did indeed cause the viewer to perform an act of faith through the image of the Virgin and Child, while the image was also perceived as Songzi Guanyin in Chinese eyes, which conformed to their own social, cultural, and religious concepts. This phenomenon reflects a “cultural translation” proposed by Peter Burke, which describes what happens in a cultural encounter when each side tries to make sense of the actions of the other (

Burke 2007, p. 8). The interaction between images of the Virgin and Child and the Songzi Guanyin also led to the creation of a culture “in-between”—a space that does not maintain a single position but forms identities in an ongoing process and reveals hybrid forms of culture, art, and religion (

Curvelo 2021, p. 273). As represented by the Sino-Portuguese ivory sculpture of the Virgin and Child, the multicultural and multireligious iconography bears witness to the ability of Christianity to transcend cultural and religious boundaries and the power of materiality and visuality in religious belief.

The intimacy between art and religion has prevailed beyond historical convolutions, transformations, and permutations in global cultural and religious values. Religious art serves as both a reflection of humanity’s deepest spiritual convictions and a means to communicate with other cultures and religions. We believe that religious art is not just about the past; it is about bridging time, is a window into the soul of civilizations, revealing how we are understood by others, illuminating interactions between different religions and cultures, and fostering a better understanding of human history and culture.