Sacred Space and Faith Expression: Centering on the Daoist Stelae of the Northern Dynasties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Background and Research Design

2.1. Research Background

2.2. Research Design

2.2.1. Visual Culture Study

- Iconographic Analysis: Examine the imagery depicting the main Daoist deity, the Heavenly Palace, and the Xiwangmu Xianjing 西王母仙境 (Queen Mother of the West’s transcendent realm) represented on the stelae.

- Phenomenological Analysis: Apply Eliade’s theory of symbols and myth to interpret these two types of imagery.

- Key Argument: The combined presence of these visual elements transforms the Daoist stelae from profane stelae into manifestations of the sacred (hierophanties).

- Emerging Question: How do believers utilize the stele as a hierophany to facilitate the transformation from the profane to the sacred?

2.2.2. Material Culture Study

- Material Analysis: Investigate the religious spaces and religious rituals associated with the stelae.

- Phenomenological Analysis: Employ Eliade’s theory of sacred space to analyze both spatial and ritual dimensions.

- Key Argument: Within the sacred space centered around the stelae, ritual activities are performed by believers who envision, experience, and engage with the divine, commune with deities, and ultimately seek both self-transcendence and divine blessings.

3. Visuality: Symbol, Myth, and Faith Expression

3.1. Symbols: The Main Deity and Heavenly Palace

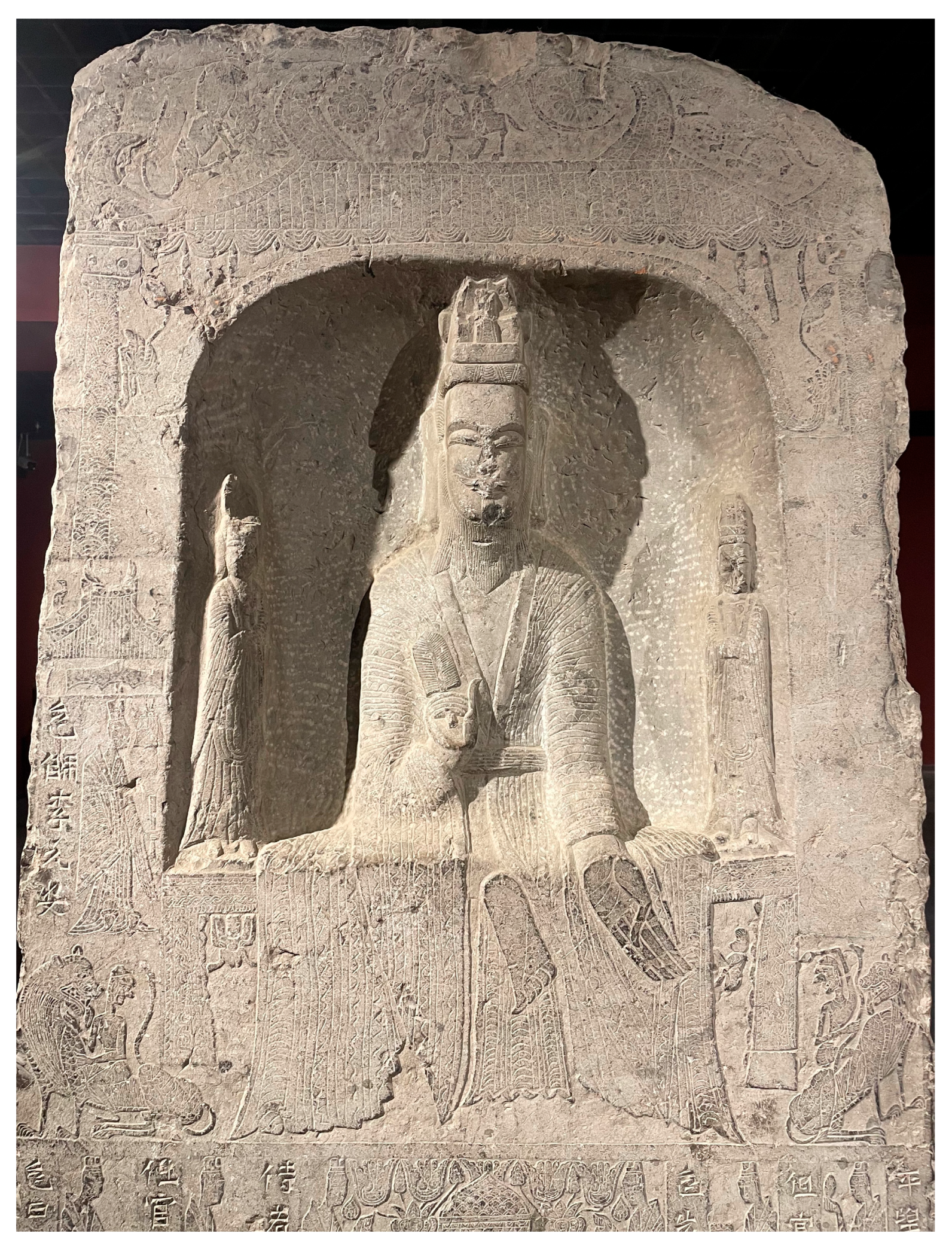

3.1.1. Main Deity

- Wearing a Daoist crown: Most crowns are typically shaped like a mountain or a cross, featuring a prominent central peak.

- Holding a zhuwei 麈尾 (elk tail whisk): This iconic Daoist implement first appeared in visual representations of Daoist figures during the Northern Wei.

- Wearing a chin mustache: The mustache is typically styled as whiskers or in the form of one or three wisps (X. Zhang 2010, p. 171).

- Wearing a waist belt: The main deity is portrayed with a belt fastened around the waist to secure the garments tightly.

The bas-relief design emerges, luminous as the true countenance manifests in the present age.

隱起形圖,煥若真容現於今世。9

Inscribing the true countenance in stone.

刊石真容。10

Carving a [visible] image on the stone reveals the true countenance.

刊石出真容。11

When the carving was complete, the stele was considered to represent the true countenance.

雕刻成就,與真容並應。12

The sacred image and true countenance—transcendently swirling in sublime beauty.

聖相真容、妙絕婆娑。13

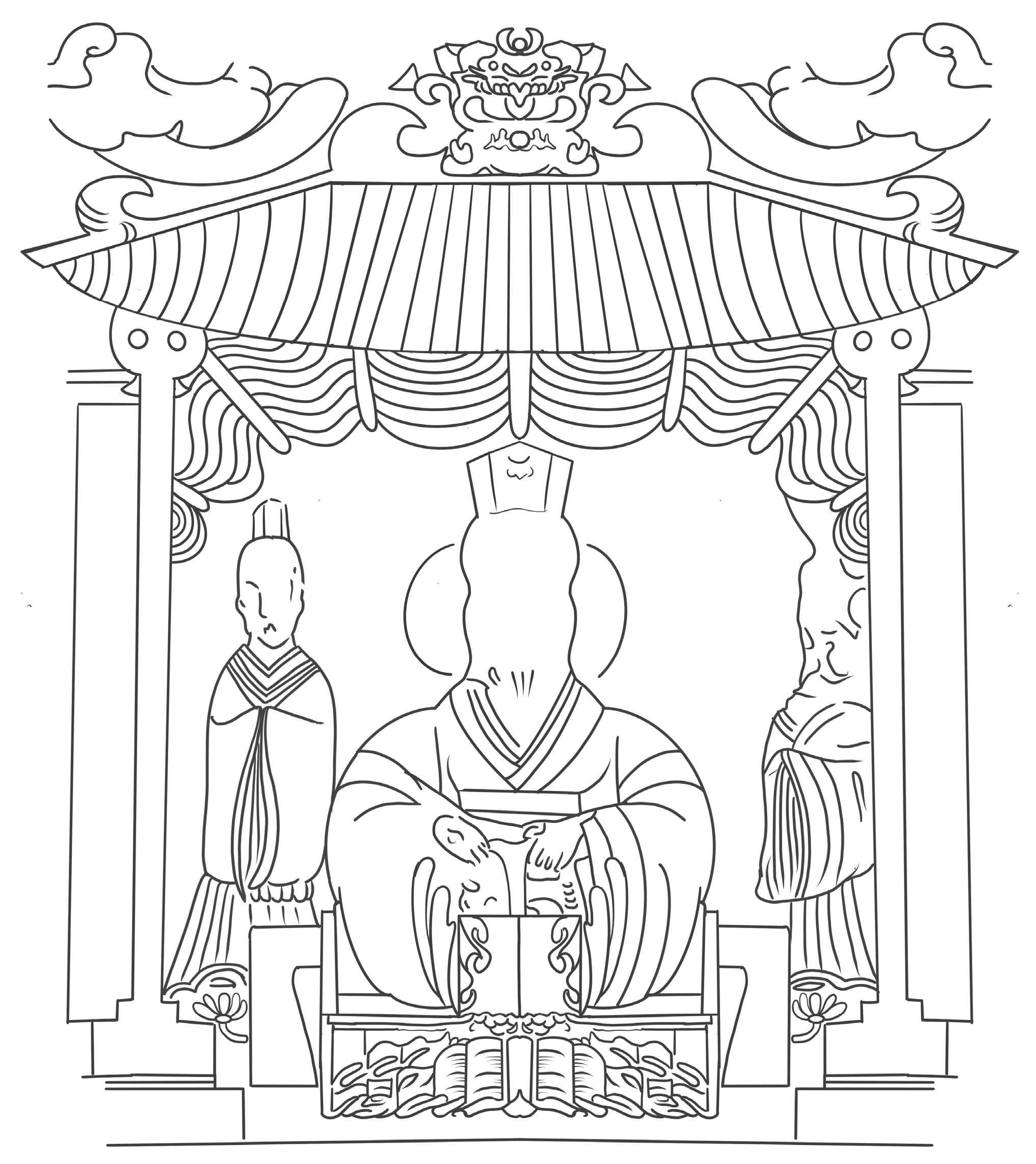

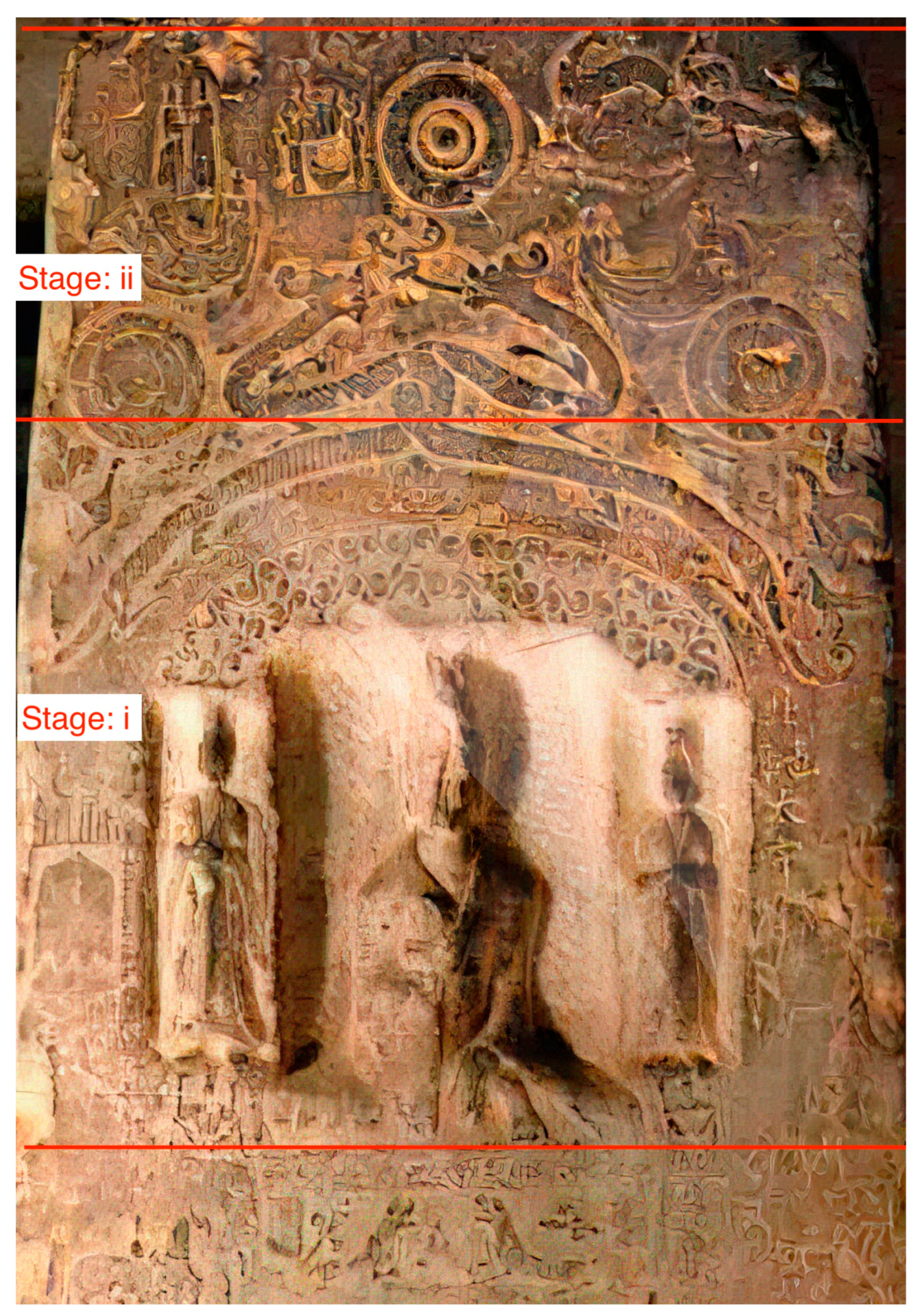

3.1.2. Heavenly Palace

3.2. Myth: The Queen Mother of the West’s Transcendent Realm

- Regarding the sun and moon, Liji 禮記 (Records of Rites) depicts, “The sun rises in the east and the moon emerges in the west” (日出於東,月生於西). In a manner akin to Eliade’s symbolic framework, the sun and moon within the myth of the Xiwangmu symbolize the cyclical themes of rebirth and immortality—that is, a return to the original unity of the sacred.

- Associated with the sun and moon are two mythical creatures: the sanzu wu and the toad. The Huainan zi 淮南子 (The Master of Huainan) records, “There is a Junwu in the sun” (日中有駿烏), and Gaoyou 高誘, a literati-official from the late Eastern Han, explains that Junwu refers to the sanzu wu. The Taiping yulan 太平御覽 (Imperial Readings of the Taiping era) states that toads are moon spirits. In Lingxian 靈憲 (Divine Rules [of Astrology]), authored by Zhang Heng 張衡, we learn that Chang’e 嫦娥, the wife of Hou Yi 后羿, stole the elixir of immortality from the Xiwangmu and, after consuming it, flew to the moon and transformed into a toad.

- The rabbit pounding medicine symbolizes the immortal elixir, and those who obtain it are believed to transcend mortality.

3.3. Constructing a Complex Religious Meaning System

- Daoist believers construct the sacred through depictions of the main deity and the Heavenly Palace, aspiring to enter this celestial domain, engage in prayer and commune with the deities, and ultimately dwell among them.

- Through the imagery of the Xiwangmu, believers envision the sacred in terms of rebirth and immortality.

4. Materiality: Daoist Fasts and Sacred Space

- Incense burning and praying. The presence of images such as Shixiang 侍香 (Server of Incense) and Tianxiang 添香 (Incense Replenisher), the timing of Xianglu zhu 香爐主 (Incense Burner Owner) on the stele, as well as the records in Daoist scriptures18, suggest that incense burning and worship constituted important ritual practices during this period. Du Guangting 杜光庭 (850–933), in his Taishang huanglu zhaiyi 太上黃箓齋儀 (Fast Ritual of the Yellow Register of the Most High, completed in 891 CE), records the following:When performing the retreat and practicing the Dao, the most urgent tasks are burning incense and lighting lamps. Burning incense conveys one’s thoughts, moving the true gods above.凡修齋行道,以燒香燃燈最為急務。香者,傳心達信,上感真靈。(DZ 507, 56.1a.)

- ii.

- Visualizing of deities. Local believers during the Northern Dynasties may have employed physical representations of deities carved on Daoist stelae as aids in cunxiang yi 存想儀 (visualization rituals), using these tangible forms to visualize the invisible celestial beings (Yuan Zhang 2025). In this way, they could “see the true form of the Most High” (睹太上真形),19 “often behold the sagely appearance” (常睹聖容),20 and “face upon the true Dao” (面睹真道).21 Dongxuan lingbao sandong fengdao kejie yingshi洞玄靈寶三洞奉道科戒營始 (The Regulations for the Practice of Daoism in Accordance with the Scriptures of the Three Caverns, of the Cavern Mystery and Numinous Treasure), composed during the mid to late Southern Dynasties 南朝 (420–589 CE), includes records concerning the use of images for visualization:The great image has no form; ultimate perfection has no shape. It is profoundly tranquil, void, and alone. Sight and hearing cannot reach it. But, in response to circumstance it manifests a body; momentarily seen, it returns to hiding. That by which those who visualize the perfected and attach their thoughts to the sagely appearances, is to use cinnabar and azure, gold and precious stones to draw pictures of their forms, so as to image the perfected appearances, and adorn them with white powder. All those who wish to focus their minds, should first make [visible] images. By burning incense to serve in reverence, and visualizing morning and evening as if facing the true forms. In past and future [lives], you gain boundless good fortune and realize the true Dao.(Translation from Raz 2017, p. 132)夫大像無形,至真無色,湛然空寂,視聽莫偕。而應變見身,暫顯還隱。所以存真者,係想聖容,故以丹青金碧摹圖形相,像彼真容,飾茲鉛粉。凡厥繫心,皆先造像。……禮拜燒香,晝夜存念,如對真形。過去未來,獲福無量,克成真道。(DZ 1125, 2.1–2b.)

- iii.

- Sitting cross-legged before the stele, closing their eyes, and meditating upon Daoist scriptures. As depicted on the Daoist Yao Boduo Stele of 496 CE 北魏太和廿年道民姚伯多造像碑, “Sitting in meditation with eyes closed, chanting Daoist scriptures while surrounded by fellow practitioners” (坐冥真经,四面竞求). The surrounding space was thus ritually sacralized and functioned as a sacred space of religious activity. Within this sacred space, believers engaged in sincere worship rituals—closing their eyes and softly chanting scriptures—to petition the deities for peace in the realm, population prosperity, the longevity and wealth of the living, and absolution for the sins of the deceased, allowing them to ascend to the celestial realm.

5. Conclusions

- Constructing sacredness through symbolism: The figure of Laojun and the image of “Laojun with the house” symbolize the Heavenly Palace, the dwelling place of deities, reflecting believers’ aspiration to enter the celestial realm.

- Constructing sacredness through mythology: Believers drew upon symbols associated with the Xiwangmu—including the sun, moon, sanzu wu, toad, and medicine-pounding rabbit—to construct a mythical world of immortality.

- An integrated religious system: These symbols and myths together formed a complete system of religious meaning that transformed the stele into a hierophany—an embodiment of sacred presence.

- The stele, as a three-dimensional artifact, occupies physical space; yet, through ritual activity, it also generates sacred space distinct from ordinary profane space.

- Ritual activities surrounding stelae include incense burning and praying, visualizing of deities, as well as closing the eyes and meditating upon Daoist scriptures.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The inscriptions used in this paper—including fayuanwen 發願文 (votive prayers) and timing 題名 (name inscriptions)—are primarily transcribed from the author’s fieldwork, supplemented by references to published sources, including Chen (1988), Zhang and Zhao (1996), Lu (2011), S. Li (2012) and H. Wei (2017). |

| 2 | In the early stages of Daoism, there were no Daoist images, primarily due to Daoism’s own theological system: since the Dao arose from non–being, it has no shape or physical image. See (Lai 1998, p. 13). |

| 3 | From the Zhuqi Brothers Stele of 512 CE 北魏延昌元年朱奇兄弟造像碑. |

| 4 | From the Stele of Lord Lao Dedicated by Male Official Jiang Zuan in 565 CE 北齊天統元年男官姜纂造老君像碑, the votive prayers of this stele have historically been regarded as derived from Buddhist terminology (Ye 1994, pp. 312–13; Qian 1979, p. 1511). In addition, the Buddhist terminology “under the dragon-flower tree” (longhua sanhui 龍花/華三會) and “the first assembly of the dragon flower” (longhua chuhui 龍花/華初會) are also frequently seen in various inscriptions, such as the Stele of Four-Sided Daoist Images Dedicated by Fu [given name] in 499 CE 北魏太和廿三年傅某造四面道像), Yang A-shao Stele of 500 CE 北魏景明元年楊阿紹造像碑, and Yang Manhei Stele of 500 CE 北魏景明元年楊曼黑造像碑. |

| 5 | The phenomenon of Daoism being predominant while also incorporating elements of Buddhism is related to the dependence of Buddhism on Daoism in the Guanzhong and Guandong regions during the Northern Dynasties, as well as the inclusiveness of Daoist beliefs as the mainstream culture towards Buddhism. For related research, see Z. Zhang (2003, p. 110), Abe (2000, p. 472), Luo (2008, pp. 220–77) and Wong (2004, pp. 109–14). |

| 6 | This paper examines Daoist stelae from the Northern Dynasties period, which were initially recorded in Qing Dynasty epigraphic compendia such as Huanyu Fangbei Lu 寰宇訪碑錄 (Sun and Xing 1977) and Jinshi Cuibian 金石萃編 (C. Wang 1977), primarily focusing on the collection and transcription of inscriptional texts. Over the past century, substantial advances have been made by both Chinese and international scholars in the study of these materials. These achievements may be broadly categorized into three areas: i. Describing and analyzing the iconographic themes, forms, and styles (S. Li 1995, pp. 112–16; Little and Eichman 2000, p. 167; Hu 2004, pp. 242–53; Ishimatsu 2017, pp. 69–91); ii. interpreting and verifying the inscriptions of fayuanwen and timing (Han and Yin 1984, pp. 46–51; Kamitsuka 1993, pp. 225–89; Zhang and Zhao 1996); and iii. combining the above to address external problems, such as the integration of Daoism and Buddhism, ethnic fusion, and social realities (James 1989, pp. 71–76; Matsubara 1995, pp. 35–52; Abe 2000, pp. 461–83; Zhang 2003). |

| 7 | For a more detailed discussion of pictorial reproductions, see Wu (2009, pp. 1–28). |

| 8 | “Local Daoism” in this study refers to a distinct form of Daoist practice rooted in regional or popular traditions, in contrast to the institutionalized or philosophical Daoism described in canonic sources. It is characterized by three main features. First, its adherents were primarily drawn from the middle and lower strata of society in the Guanzhong and Guandong regions during the 5th and 6th centuries, rather than from the ranks of formally ordained Daoists. Second, their religious practices centered on stele dedicating, which diverged significantly from the ritual and doctrinal activities prescribed in Daoist scriptures. Third, in contrast to the ethnic and religious tensions often observed within elite circles of the period, local believers demonstrated varying degrees of integration in both cultural identity and religious belief. |

| 9 | From the Daoist Yao Boduo Stele of 496 CE 北魏太和廿年道民姚伯多造像碑. |

| 10 | From the 60 Members of the Association Stele of 517 CE 北魏熙平二年邑子六十人造像碑. |

| 11 | From the Wang Shouling Stele of 519 CE 北魏神龜二年王守令造像碑. |

| 12 | From the Qi Shuanghu Stele of 520 CE 北魏神龜三年錡雙胡碑. |

| 13 | From the Stele of Lord Lao Dedicated by Male Official Jiang Zuan in 565 CE 北齊天統元年男官姜纂造老君像碑. |

| 14 | From the Zhongyue Songgao Lingmiao Stele 中嶽嵩高靈廟碑. |

| 15 | From the Stele of the Most High Lord Lao Dedicated by Cai Hong in 548 CE 西魏大統十四年蔡洪造太上老君像碑. |

| 16 | From the Stele of the Celestial Worthy Dedicated by Li Yuanhai in 572 CE 北周建德元年李元海造天尊像碑. |

| 17 | Most of the existing literature on Daoism consists of official documents, such as the Daozang 道藏 and Weishu 魏書, which focus primarily on princes, nobles, and high officials, while rarely addressing the local beliefs of the Northern Dynasties. As these texts were composed by upper-class elites, they are insufficient to accurately reflect the religious beliefs of the common people during the Northern Dynasties. |

| 18 | In the Laojun yinsong jiejing老君音誦戒經 (Scripture of the Intoned Precepts of Lord Lao) (Kou 1988), “Method for Daoist Officers, novices, and Lay Devotees (Male & Female) to Burn Incense and Make Petitions: Enter the oratory, face east with solemnity. Offer incense three times, then perform eight prostrations…Finally, place pinches incense into the burner with ritual hand gestures” (道官籙生男女民燒香求願法:入靖,東向懇,三上香,訖,八拜……便以手捻香著爐中; DZ 785, 11). |

| 19 | For example, the Feng Shenyu Stele of 505 CE 北魏正始二年馮神育造像碑. |

| 20 | From the Xia Houseng___Stele from the Northern Wei Dynasty 北魏夏侯僧□造像碑. |

| 21 | From the 70 Members of the Association Stele of 519 CE 北魏神龜二年邑子七十人造像碑. |

References

- Abe, Stanley K. 阿部賢次. 2000. Shaanxisheng de beiwei diaoke: Laiyuan, zanzhu, yuanwang 陝西省的北魏雕刻:來源、贊助、願望 [Northern Wei Sculpture from Shaanxi Province: Provenance, Patronage, Desire]. In Hantang zhijian de zongjiao yishu yu kaogu 漢唐之間的宗教藝術與考古 [Northern Wei Sculpture from Shaanxi Province: Provenance, Patronage, Desire]. Edited by Hung Wu 巫鴻. Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe, pp. 461–83. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Yuan 陳垣. 1988. Daojia jinshilue 道家金石略 [A Compendium of Daoist Stone Inscriptions]. Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Eliade, Mircea. 1958. Patterns in Comparative Religion. New York: Sheed and Ward. [Google Scholar]

- Eliade, Mircea. 1987. The Sacred and The Profane: The Nature of Religion. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. [Google Scholar]

- Eliade, Mircea. 2001. The Sacred & The Profane: The Nature of Religion. Translated by Yang Su’e. Taibei: Guiguan Tushu Gufen Youxian Gongsi, p. 241. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Hong 葛洪. 1995. Baopuzi 抱樸子 [Master Embracing Simplicity]. Beijing: Yanshan Chubanshe, p. 228. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Wei 韓偉, and Zhiyi Yin 陰志毅. 1984. Yaoxian Yaowangshan de fodao hunhe zaoxiangbei 耀縣藥王山的佛道混合造像碑 [Buddhist-Daoist Syncretic Stele from Yaowang Mountain, Yaoxian County]. Archaeology and Cultural Relics 考古與文物 5: 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Wenhe 胡文和. 2004. Zhongguo daojiao shike yishushi 中國道教石刻藝術史 [The History of Chinese Daoist Art of Stone Carving]. Beijing: Gaodeng Jiaoyu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Ishimatsu, Hinako 石松日奈子. 2017. Zhongguo chuqi daojiao tuxiang he laonianxiang laojunxiang de dansheng 中國初期道教圖像和老年相老君像的誕生 [Early Daoist Iconography in China and the Emergence of the Elderly Laozi Image]. Translated by Chun Yu 于春. The Study of Art History 藝術史研究 19: 69–91. [Google Scholar]

- James, Jean M. 1989. Some Iconographic Problems in Early Taoist-Buddhist Sculptures in China. Archives of Asian Art 42: 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kamitsuka, Yoshiko 神塚淑子. 1993. Nanbokuchō jidai no dōkyō zōzō: Shūkyō shisōshiteki kōsatsu o chūshin ni 南北朝時代の道教造像─宗教思想史的考察を中心に─ [Daoist Sculptures of the Northern and Southern Dynasties Period: A Focus on Religious and Ideological Perspectives]. Kyoto: University of Kyoto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kou, Qianzhi 寇謙之. 1988. Laojun yinsong jiejing 老君音誦誡經 [The Supreme Venerable Sovereign’s Book of Commandments for Chanting] (DZ 785). Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe and Shanghai: Shanghai Shudian. Tianjin: Tianjin Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Chi-tim 黎志添. 1998. The Opposition of Celestial–Master Taoism to Popular Cults during the Six Dynasties. Asia Major 11: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Daoyuan 酈道元. 1976. Shui jingzhu 水經註 [Commentary on the Water Classic]. Beijing: Qinding Siku Quanshu Chubanshe, p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Song 李凇. 1995. Guanzhong beichao daojiao zaoxiangbei zhaji 關中北朝造像碑研讀札記 [Research Notes on Northern Dynasties Stelae in the Guanzhong Region]. Journal of Stele Forest Studies 碑林集刊, 112–26. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Song 李凇. 2012. Zhongguo daojiao meishushi 中國道教美術史 [A History of Chinese Daoist Art]. Hunan: Hunan Meishu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Little, Stephen, and Shawn Eichman. 2000. Taoism and the Arts of China. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Rui 劉睿. 2015. 北朝道教造像再考察——以造像碑為中心 [重新审视北朝道士形象:以道家碑文为中心]. Archaeology and Cultural Relics 考古文物 4: 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Yang. 2003. Śākyamuni and Laojun Seated Side by Side: Catching a Glimpse of Northern Dynastics Buddhist/Taoist Relationship from a Popular Iconography. In Ancient Taoist Art from Shanxi Province. Edited by Susan Y. Y. Lam. Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong Press, pp. 54–63. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Yi 劉屹. 2003. Kouqianzhi shenhou de beitianshidao 寇謙之身後的北天師道 [The Northern Celestial Masters Daoism After Kou Qianzhi]. Journal of Capital Normal University (Social Sciences Edition) 首都師範大學學報 1: 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Hongcai 羅宏才. 2008. Zhongguo fodao zaoxiangbei yanjiu:yi guanzhong diqu wei kaocha zhongxin 中國佛道造像碑研究:以關中地區為考察中心 [The Study of Chinese Buddho–Daoist Sculpted–Image Stele: Centered on the Guanzhong Area]. Shanghai: Shanghai Daxue Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Xun 魯迅. 2011. Lu Xun jijiao shike shougao 魯迅輯校石刻手稿 [Lu Xun’s Compiled Manuscripts of Stone Inscriptions]. In Lu Xun daquanji 25 魯迅大全集 [The Complete Works of Lu Xun 25]. Edited by Xinyu Li 李新宇 and Haiying Zhou 周海嬰. Wuhan: Changjiang Wenyi Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Lü, Pengzhi 呂鵬志. 2020. Zhongguo zhonggu shidai de fodao hunhe yishi: Daojiao zhongyuanjie qiyuan xintan 中國中古時代的佛道混合儀式——道教中元節起源新探 [Buddhist-Daoist Rituals in Medieval China: A New Study on the Origin of the Daoist Middle Prime Festival]. Studies in World Religions 世界宗教研究 2: 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara, Saburou 松原三郎. 1995. Zōtei Chūgoku bukkyō chōkokushi kenkyū 増訂中国仏教彫刻史研究 [Studies in the History of Chinese Buddhist Sculpture: Revised Edition]. Tokyo: Toukyou Yoshikawakoubunkan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pals, Daniel L. 2015. Nine Theories of Religion. Oxford: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Zhongshu 錢鐘書. 1979. Guanzhui bian 管錐編 [Limited Views]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Randall, Studstill. 2000. Eliade, Phenomenology, and the Sacred. Religious Studies 36: 177–94. [Google Scholar]

- Raz, Gil. 2017. Local Daoism: The Community of the Northern Wei Dao-Buddhist Steles. In Zhongguo zhonggu yanjiu 1 中國中古研究 [Studies in Medieval China]. Edited by Yu Xin 余欣. Shanghai: Zhongxi Shuju, vol. 1, pp. 103–50. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Xingyan 孫星衍, and Shu Xing 邢澍. 1977. Huanyu fangbei lu 寰宇訪碑錄 [Global Epigraphic Records]. In Shike shiliao xinbian 石刻史料新編 [Historical Materials from Stone Inscriptions, A New Compilation]. series 1; Taipei: Xinwenfeng Chubanshe, vol. 26. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Chang 王昶. 1977. Jinshi cuibian 金石萃編 [Compendium of Bronze and Stone Inscriptions]. In Shike shiliao xinbian 石刻史料新編 [Historical Materials from Stone Inscriptions, A New Compilation]. series 1; Taipei: Xinwenfeng Chubanshe, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Ming 王明. 1985. Baopuzi neipian jiaoyi 抱樸子內篇校譯 [Annotated Critical Edition of the Master Who Embraces Simplicity: Inner chapters]. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju Chubanshe, p. 274. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Hongli 魏宏利. 2017. Beichao Guanzhong diqu zaoxiangji zhengli yu yanjiu 北朝關中地區造像記整理與研究 [Compilation and Research on Inscriptions from the Guanzhong Region of the Northern Dynasties]. Beijing: Zhongguo Shehui Kexue Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Shou 魏收. 1974. Weishu 魏書 [Wei History]. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Dorothy C. 2004. Chinese Steles: Pre-Buddhist and Buddhist Use of a Symbolic Form. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Hung. 2009. Chongping: Zhongguo huihua zhong de meicai yu zaixian 重屏:中國繪畫中的媒材與再現 [The Double Screen: Medium and Representation in Chinese Painting]. Shanghai: Shanghai Century. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Changchi 葉昌熾. 1994. Yushi 語石 [Inscriptions]. In Yushi Yushi yitong ping 語石 語石異同評 [Epigraphic Studies: Critical Annotations on Stone Inscriptions]. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Xunliao 張勛燎. 2010. Beichao daojiao zaoxiangbei zaiyanjiu 北朝道教造像碑再研究 [Re-discussion on the Daoist Stelae of the Northern Dynasties]. Southern Ethnology and Archaeology 南方民族考古 6: 163–206. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Yan 張燕, and Chao Zhao 趙超. 1996. Bei Chao fodao zaoxiangbei jingxuan 北朝佛道造像碑精選 [Selected Northern Dynasties Buddhist and Daoist Stelae]. Tianjin: Tianjin Guji Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Yuan 張媛. 2025. Cong heyi zaoxiang yicun kan beichao daojiao yiyi 從合邑造像遺存看北朝道教義邑 [Daoist Association in the Northern Dynasties: Perspectives from Communal Statues]. Archaeology and Cultural Relics 考古與文物 1: 103–104. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Yuan 張媛. Forthcoming. An Examination of Local Daoist Activities during the Northern Dynasties: A Study of Daoist Stelae Inscriptions. Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae.

- Zhang, Zexun 張澤珣. 2003. Beiwei guanzhong daojiao zaoxiangji yanjiu: Diyu de zaongjiao wenhua yu yishihuodong 北魏關中道教造像記研究:地域的宗教文化與儀式活動 [The Daoist Epigraphs of the Northern Wei Dynasty: A Study of the Guanzhong District’s Religious Culture and Ritualistic Activities]. Ph.D. dissertation, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Chuan 趙川. 2022. Daojiao zaoxiang qiyuan xintan 道教造像起源新探 Revisiting the Origins of Daoist Sculpture: A New Investigation]. Literature and History 文史 3: 99–116. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y. Sacred Space and Faith Expression: Centering on the Daoist Stelae of the Northern Dynasties. Religions 2025, 16, 780. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16060780

Zhang Y. Sacred Space and Faith Expression: Centering on the Daoist Stelae of the Northern Dynasties. Religions. 2025; 16(6):780. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16060780

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yuan. 2025. "Sacred Space and Faith Expression: Centering on the Daoist Stelae of the Northern Dynasties" Religions 16, no. 6: 780. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16060780

APA StyleZhang, Y. (2025). Sacred Space and Faith Expression: Centering on the Daoist Stelae of the Northern Dynasties. Religions, 16(6), 780. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16060780