Abstract

Outcome research is becoming increasingly important in chaplaincy. However, current outcome measures rarely reflect outcomes reflecting chaplaincy goals. This limits the understanding of the effect of chaplaincy care. Therefore, we have developed the Dutch Chaplaincy Outcome Measure (NUGV). It uses a Q-methodology, comprising a two-step sorting task of 25 statements and a brief post-sorting interview. The statements relate to four goals of chaplaincy: worldview development, coping with life events and circumstances, relational affirmation, and transcendence and connectedness. The statements were derived from a literature review, interviews with 24 clients of chaplaincy in primary, outpatient, or community care, and eight focus groups with clients, chaplaincy, and other professionals in primary, outpatient, or community care. Acceptability, clarity, and (face) validity were examined with a client council, in a workshop, and through two pilot studies. They were found to be satisfactory. Thus, the NUGV seems to be a promising instrument for outcome assessment in chaplaincy. More research is needed on the construct validity and specificity of the outcomes, as well as the use of the instrument in inpatient settings and among people with lower language and cognitive capabilities. We recommend that researchers administer the NUGV in person, to enable more support during the sorting task and to facilitate richer data in the post-sorting interview.

1. Introduction

In recent years, an increasing number of studies examine the outcomes or effects of chaplaincy care. This research not only shows effects of care, but could also help to improve its quality by showing to what extent chaplaincy care is meeting its objectives. A review of the Dutch literature on the goals of chaplaincy showed that the development of one’s worldview—clarifying it, personalizing it, integrating new perspectives in it, living in accordance with it, and engaging with it to find answers to life questions and/or to process life events—was most often considered a goal of chaplaincy (Visser et al. 2023).

However, these dimensions are not present in most of the measures currently used in chaplaincy outcome research. Instead, these studies focus more on emotional and physical well-being (Visser et al. 2023). To name a few, Iler et al. (2001) examined the effects of chaplaincy visits on lower anxiety and a shorter length of hospital stay in a quasi-experimental study among COPD patients. Similarly, Berning et al. (2016) investigated whether patients at an ICU receiving a chaplaincy intervention reported lower anxiety and stress after the intervention. Though well-being was considered a goal in the Dutch chaplaincy literature examined by Visser et al. (2023), it was considered a secondary goal. Thus, current studies might not adequately assist with the quality-improvement objective of outcome research.

One of the reasons why studies on chaplaincy may not have assessed outcomes that are more closely related to chaplaincy goals might be that there are very few outcome measures available that have been developed with chaplaincy care in mind. The Lothian PROM is the only outcome measure for chaplaincy available at present. However, in this instrument, which is said to assess spiritual well-being, this construct is operationalized as a mix of anxiety, being able to be honest with oneself, having a positive outlook on one’s situation, feeling in control of one’s life, and feeling a sense of peace (Snowden and Telfer 2017). This raises the question of if this operationalization missed the mark, because this operationalization of spiritual well-being does not seem to be in line with other, more well-known, measures of this construct, such as the FACIT-SP (Peterman et al. 2002). In this and other spiritual well-being measures, spiritual well-being is generally defined as a sense of meaning, peace, purpose in life, and comfort as well as strength derived from one’s faith (Austin et al. 2018). It is thus unclear whether the Lothian PROM assesses spiritual well-being or rather a sense of emotional well-being, and, with that, how representative it is of chaplaincy goals.

Therefore, we have developed the Dutch Chaplaincy Outcome Measure (NUGV: Nederlandse Uitkomstmaat Geestelijke Verzorging), an outcome measure that represents the primary objectives of chaplaincy care. In this paper, we report on its development.

Background: PROM Development

The NUGV is a so-called PROM: a patient-reported outcome measure. PROMs are typically self-report questionnaires in which patients indicate their experience of their health or functioning (Visser 2019). These questionnaires are used to evaluate the efficacy of a certain treatment, so they are filled out before and after the treatment to determine whether the health or functioning of the person has changed in the desired direction and to the desired extent. Such evaluations can take place at the level of an individual patient for monitoring, the level of an individual chaplain, a department or an organization for internal quality assessment, or the level of a profession for external quality assessment or research.

It is important in a PROM that the aspects of health or functioning that are assessed are addressed by the treatment under scrutiny and that they are amenable to change. The aspects of health or functioning that are assessed in a PROM are called PROs: patient-reported outcomes (Terwee et al. 2015). PROs can cover any aspect of health or functioning, such as whether a person can climb a flight of stairs without becoming out of breath, their level of pain, feelings of anxiety, issues concentrating, feelings of safety, experiences of social support, or experiences of meaning in life. A PROM for chaplaincy care should assess aspects that are affected by this type of care.

Verkerk et al. (2017) stress that the PROs should not only reflect the perspective of the care providers on the objectives of care, but also (and perhaps even more) that of the patients. After all, patients’ goals for a specific type of care may differ from those of the care provider. Both perspectives are important when deciding on which factors reflect whether a profession is ‘doing good’. In addition, it is considered important to include the perspectives of other care providers, because care is often offered in a multidisciplinary context and patients are referred to a care provider by their colleagues for specific reasons. In the development of the Lothian PROM, patients were only included in item construction, not in decision making about the themes that should be included in the PROM (Snowden and Telfer 2017). In the development of the NUGV, we have included chaplains, patients, other care providers, and other partners of chaplains (for example, managers and researchers) in all stages of development.

Finally, in the present study, we have examined and taken into account differences in goals between populations. Different contexts of chaplaincy may emphasize different goals of care. For example, in the context of hospitals, anxiety and length of stay might be very relevant outcomes even though they are not chaplaincy-specific, because a main goal of chaplaincy might be to support the emotional and physical recovery of patients. In contrast, in primary, outpatient, and community care, outcomes such as a sense of identity or control might be more relevant, because in these contexts chaplains might more often offer longer-term support for chronic and complex issues that intersect the physical, emotional, social, and financial domains (Macdonald 2019; McSherry et al. 2016). Within these domains, there might also be differences between target populations, for example, between people receiving palliative care and people with psychiatric problems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

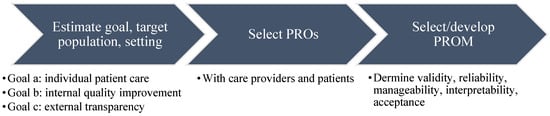

For this study, we followed the first three steps of the PROM cycle as described by Verkerk et al. (2017). The steps are displayed in Figure 1. The first step is to determine the goal, target population, and setting of the PROM. The second step is to select the outcomes that need to be assessed. The third step consists of determining the criteria for the PROM, selecting and/or developing instruments, determining the validity, reliability, manageability, interpretability, and acceptance of the PROM, and planning the test phase.

Figure 1.

First three steps of the PROM cycle as described by Verkerk et al. (2017).

This study took place in the context of the first phase of the Knowledge Workplace on Meaning and Spiritual Care (Kenniswerkplaats Zingeving) in the Netherlands. The Knowledge Workplace is a collaboration between research, education, and practice in the Netherlands, aiming at the development and collection of knowledge around spiritual care in primary, outpatient, and community care. The first phase ran from October 2021 to October 2023.

2.2. Participants

Participants consisted of a convenience sample of chaplains, clients, healthcare workers, and various other colleagues of chaplains (see Table 1). The primary participants represented eight learning networks of the Knowledge Workplace. The learning networks represented four contexts of chaplaincy: care for victims of earthquakes attributed to gas extraction,1 general healthcare, pediatric palliative care, and care for the unhoused. Some people participated in only one part of the study and others participated in several. This depended on the availability of the group and/or person. In Table 1, it is explicated which groups were represented in which parts of the study.

Table 1.

Overview of participants in the four stages of the study.

In addition, the client council of the Knowledge Workplace (n = 4), chaplains and chaplaincy researchers at a meeting of the Dutch Association of Spiritual Caregivers (VGVZ; n = 10), and chaplains, researchers, students, healthcare professionals, policymakers, and one client (n = 27) at a workshop at a symposium of the Knowledge Workplace were consulted during the study. No sociodemographic data were gathered from the participants. They represented people from different denominations, ethnicities, and chaplaincy contexts.

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

The primary form of data collection consisted of two focus group sessions with each individual learning network. For each focus group session, a person from the learning network (the chair, coordinator, junior researcher, or a chaplain) was asked to send an information letter and an informed consent form to the members of the network, with the request to find at least two chaplains, two healthcare workers, and two clients. If not enough members from the learning network itself were available, the contact persons were asked to approach others from the same context. Most focus groups were conducted in person or in a hybrid format; a few were conducted fully online. The first focus group sessions with the learning networks took place between November 2022 and March 2023. The second session took place between March and June 2023. Each focus group session took 90 min. The conversations were audio-recorded and transcribed, to support the interpretation of the findings. In accordance with the general policy of the Knowledge Workplace, participants received compensation of EUR 100 per hour and reimbursement of their travel costs. Data collection and analysis took place in several stages. In the first two stages, we determined the goal, target population, setting, and PROs (steps 1 and 2 of the PROM cycle). In the third and fourth stages, we developed and evaluated the instrument (step 3 of the PROM cycle). We describe the stages in more detail below.

2.3.1. Stage 1: Goals of Chaplaincy

The first focus group session of each learning network centered on the goals of chaplaincy in primary, outpatient, and community care: what are the main objectives of chaplaincy in this context? We used the nominal group technique in this round (McMillan et al. 2016). This is a structured brainstorming technique for reaching consensus, in which generated ideas are prioritized and voted on. The participants were first asked to silently list as many goals of chaplaincy as they could think of within 5 min. To facilitate a broad range of ideas, the concept of goals was explained with the following questions: If you are a chaplain, what do you hope for your client? If you are a healthcare worker, what do you hope will happen for your client when they meet with the chaplain? If you are a client, what do you hope for yourself in your contact with the chaplain? After 5 min, the goals that people wrote down were gathered one-by-one, until everyone had mentioned the goals that they had written down. People could spontaneously add goals, or they could skip one if they felt someone else had already mentioned it. The goals were written verbatim in a spreadsheet that was projected on a screen for all participants to see or on a flip chart. Then, a discussion round took place in which people could ask clarifying questions or slightly rephrase goals for clarification. Sometimes goals that appeared similar were rephrased into an overarching goal.

The next step was to prioritize goals. To this end, each participant was asked to choose the five most important goals from those that had been mentioned, and to place them in order of importance. When they had done so, the top 5 of each participant were gathered one-by-one, assigning scores between 1 (least important of the five) and 5 (most important of the five). The scores were added up to create a total score for each goal and an overall ranking of the goals. The ordering was then discussed to learn whether it adequately represented what the group felt was most important about the meaning of chaplaincy for the population represented by their learning network.

After the first focus group sessions with all the learning networks had been completed, the data were analyzed to determine the level of consensus about goals between the learning networks. This would help us determine if a generic or population-specific instrument was needed. To do so, content analysis (Krippendorff 2019) was used to categorize the top 5 goals within and between learning networks. The goals of chaplaincy in the Netherlands identified in the review by Visser et al. (2023) served as a conceptual framework in this analysis, to help categorize the goals. Though the exact phrasing and emphasis of the goals mentioned sometimes differed between learning networks, four dimensions or overarching goals could be observed that were present for each learning network. We named these worldview development, coping with life events and circumstances, relational affirmation, and transcendence and connectedness. Through further literature study and data gathered from interviews with 24 clients of chaplains associated with the Knowledge Workplace (Damen et al. 2024), the representativeness of these four domains for goals of chaplaincy was verified. The dimension of worldview development included goals in which the chaplain and client work toward a fuller understanding of the worldview, identity, and life story of the client. Coping with life events and circumstances involved goals in which the chaplain and client seek to articulate, relate to, and/or process specific events and circumstances in life. Relational affirmation included goals in which the client comes to feel seen, heard, validated, and encouraged through the relationship with the chaplain. Transcendence and connectedness included goals in which the chaplain and client seek to (re)establish the connection of the client with themselves, others, the transcendent, and/or sources of spirituality and meaning.

2.3.2. Stage 2: Outcomes of Chaplaincy

After having developed a framework from which to approach chaplaincy in primary, outpatient, and community care with the four overarching goals or domains, new focus group sessions were organized with each of the learning networks to determine which outcomes were representative of these four goals. For this purpose, we took expressions about the outcomes of their chaplaincy encounters from the 24 interviews with clients of chaplains associated with the Knowledge Workplace (Damen et al. 2024). We grouped these expressions under the four goals. Some outcomes seemed to fit with more than one goal, so they were repeated.

In the focus groups, the participants were first introduced to the four goals and could ask clarifying questions to try to come to a shared understanding. Then, they were presented with a sheet of paper that contained the explanation of the goal and the outcomes that might represent this (so, four sheets in total). The participants were asked to select the five outcomes that they felt most clearly represented the goal, by circling, highlighting, or marking them in some other way. The term ‘outcome’ was clarified with the following questions: What thoughts, feelings or behaviors do you observe in yourself or in your client as a result of the meeting(s) with the chaplain? What changes do you observe in yourself or in the client? Each participant was presented with each goal in turn. If an outcome had already been selected by the previous person, they were asked to add a marking. Participants could also add outcomes if they felt something important was missing. When all participants had responded to all goals, the outcomes that were selected were typed into a spreadsheet or written on a flip chart, along with the number of people who had selected them. This overview was visible for all participants. Finally, the findings were discussed with the participants to learn if the resulting prioritization matched their experience.

A total of 128 outcomes were circled. Various outcomes had been added by the participants themselves. In the analysis, we grouped the outcomes that reflected very similar thoughts, feelings, behaviors, or attitudes, and then summed the number of times these outcomes were selected. For example, the outcomes ‘Being able to give words to thoughts and feelings’, ‘Facing what happens internally’, ‘Seeing what’s behind the anger’, ‘Facing one’s own sorrow’, and ‘Reaching the core of a thought/feeling’ were grouped under the outcome ‘Being able to express or allow thoughts and feelings’ (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Outcomes selected for the NUGV, with their composing statement, the frequency with which participants chose them, and the statements with which they are represented in the NUGV.

We also summed the frequency of the selection of outcomes that were duplicated under various goals. Then, we selected the outcomes or categories that were chosen at least 13 times. This frequency does not represent unique votes, because we had grouped outcomes or because some outcomes were mentioned under more than one goal domain. The frequency merely gave a representation of the relative importance of the outcome/category compared to the others and served as a pragmatic cut-off for the selection of outcomes. Thirteen was chosen as a cut-off, because in the case of outcomes that were not grouped or duplicated under various goals, this represented selection by at least one-third of the total number of participants (n = 38).

2.3.3. Stage 3: Instrument Construction

From the start, we questioned whether a self-report questionnaire format would fit well with chaplaincy practice. Therefore, several groups were consulted to determine the most suitable form for the PROM. In the second focus group sessions with the learning networks, we asked for advice and preferences: what did they feel the goal of the instrument should be and what kind of format (written, drawn or spoken answers, closed-ended or open-ended questions, etc.) would they prefer? Then, this question was also put to the members of the client council of the Knowledge Workplace (n = 4). The input was very varied, with some people preferring a closed format and others preferring an open one. Therefore, chaplains and chaplaincy researchers were consulted at a meeting of the Dutch Association of Spiritual Caregivers (VGVZ; n = 10). They were specifically asked to indicate their preference for the answer format: closed, with numbers, symbols, or smileys, or open, with written or spoken answers. Further discussions with assessment experts and the research team led to the Q-methodology design of the NUGV, as is presented here. The Q-methodology involves a sorting task through which attitudes (subjectivity) toward specific topics can be examined (Watts and Stenner 2012). In the Results section, we describe in detail the decisions we made regarding the goal, target population, setting, form, and content of the NUGV.

2.3.4. Stage 4: Evaluation

Feedback on the first version of the NUGV was sought from the client council of the Knowledge Workplace (n = 3). They were sent the instrument and a short user manual, so that they could try it out themselves. Feedback centered on the acceptability, clarity, and face validity of the instrument. Based on the feedback, several changes were made to the phrasing of the statements and some of the instructions were clarified (see Section 3.3.3. Changes Made).

The improved version was then tested for acceptability, clarity, and face validity in a workshop at a symposium of the Knowledge Workplace. Participants in the workshop included chaplains, researchers, students, healthcare professionals, policymakers, and one client (n = 27). After having received some background information about the instrument and its development, the participants were asked to make groups of three to five people. Each group received an envelope with instructions for the workshop, the materials for the completion of the instrument, note paper, and post-it notes. In each group, one person played the role of a client and completed the NUGV, one person played the role of a researcher and guided the assessment, and the other people observed the various aspects of the interaction and took notes. The questions for the observers were as follows: Where did the assessor struggle to keep to the script? How does the assessor deal with questions or comments of the client? How much time does completion of the instrument take? Which instructions or statements are difficult or raise questions? How long does each step of the process take? How do the assessor and client interact? The participants were given 20 min to complete the assessment. The researchers walked around and made notes of comments, questions, and observations. At the end of the 20 min, the participants were asked to end the assessment and return all the materials to the researchers, and to use the post-it notes to write comments on the acceptability, clarity, and face validity of the instrument and to attach these to the appropriate flip chart.

To reach the version described here, the first author read and grouped the comments of the workshop participants, together with several comments of the client council that had not yet been implemented. Then, changes were made where possible. These changes are described in the Results section.

Finally, between February and April 2024, two pilot studies took place using the NUGV to test its interpretability and validity. The first pilot study involved a four-week writing intervention for women who had experienced sexual abuse, led by a chaplain-in-training. The writing intervention focused on four existential themes related to sexual abuse: connectedness with others, recovery, self-worth, and a meaningful life (De Ruiter 2024). Six women participated. They completed the NUGV before the intervention and within two weeks afterwards. The second pilot study concerned a nine-week course in which chaplaincy students worked on a spiritual autobiography. Though this is not a ‘traditional’ form of spiritual care, the course aims relate to the four goals of chaplaincy observed in this study. Therefore, it was deemed an appropriate trial context for the NUGV. Eleven students completed the pre-test with the NUGV during the first session of the course. Eight students completed the post-test with the instrument within two weeks after the last session of the course.

In both pilot studies the NUGV was completed online using Q-Method software (Lutfallah and Buchanan 2019). At the pre-test, some sociodemographic information was gathered in both pilot studies. At both assessment moments, a written post-sort interview was held. At the pre-test, the participants in both pilot studies were asked what their Q-sort said about how they are doing; if there were any statements they did not understand and, if so, which; and if they had missed any statements or topics and, if so, which ones. The women in the first pilot study were also asked what they hoped for with the intervention. Because of the different context, the students in the second pilot study were asked how easy they found the sorting task and why. At the post-test, the participants were asked what their Q-sort said about how they are doing; if they felt anything had changed compared to the pre-test and, if so, why; if they had missed any statements or topics and, if so, which ones; and what was least and most helpful in the intervention.

3. Results

We describe the findings and decisions made in the order of the PROM cycle: In Section 3.1, we discuss the choices regarding the goal of the instrument, the target population, and the setting. We also discuss choices regarding the form of the instrument. These choices influenced the procedure for outcome selection and operationalization, which is described in Section 3.2. In Section 3.3, we describe the findings regarding the face validity, acceptability, and manageability of the first and the final version of the NUGV.

3.1. Goal and Form of the PROM

Chaplains, clients, healthcare workers, chaplaincy researchers, and managers gave input on the goal and form of the PROM (Table 1, stage 3). There was a lack of consensus on the goal of the instrument. The members of the client council were generally in favor of the outcome assessment on the individual client level or for research. The members of the learning networks expressed a clear preference for use at the individual client level or for internal quality assessment. They did not mention research as a possible goal of the instrument. A strong antipathy was expressed by various participants of the learning networks against the use of an instrument for external quality assessment. Some of these participants also feared that any instrument would ultimately lead to use for external quality assessment, so they did not recommend instrument development. Some participants at the meeting of the Dutch Association of Spiritual Caregivers mentioned that it would require a big shift in the mentality of chaplains to use an instrument at the individual level, even though they saw its utility, so they thought a research instrument would be a safer option.

After discussion with the research team and with assessment experts, it was decided to develop a research instrument as a first step. Though the respondents saw the use of an outcome instrument for assessment at the individual level and for internal quality assessment, uptake of such an instrument seemed unlikely at this point in time. In addition, the assessment experts indicated that more time than was available would be needed to develop an instrument with adequate psychometric qualities for use at the individual level and/or internal quality assessment.

Regarding the target population, a generic instrument seemed appropriate, because few differences were found between the goals and outcomes preferred by the learning networks (Rosie et al. 2025). Because the study was conducted in the context of the Knowledge Workplace, which focused on the settings of primary, outpatient, and community care, the utility of the instrument seems highest in this setting.

Regarding the form of the instrument, the opinions in the client council and the learning networks were divided between people who preferred a standardized, quantifiable, and short-answer format for ease of use and people who preferred a qualitative and open format for a more person-centered approach. In all cases, brevity was considered essential. The ten chaplains and researchers consulted at the meeting of the Dutch Association of Spiritual Caregivers were all in favor of a closed-ended assessment format over an open-ended format, because they considered it clearer and easier to answer and interpret. The particular choice of a closed-ended format was associated with differences in opinion on what was easier to understand and how much freedom the person needed to give their own answer. Four preferred a closed-answer format with a visual analog scale (VAS), which allows for more freedom, whereas three preferred a closed-answer format with smileys and colors, two preferred a closed-answer format with symbols and colors, and one preferred a Likert-type scale.

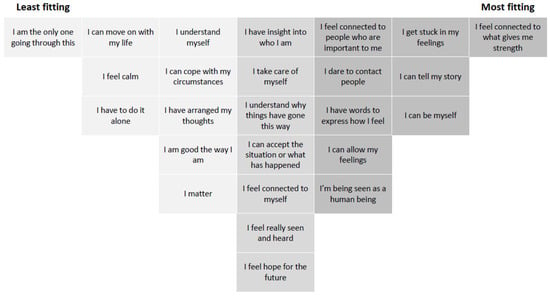

As a research team we also experienced a dilemma between respecting the qualitative and person-centered nature of chaplaincy and respecting the needs of researchers and policymakers for results that are easy to interpret and show clear answer patterns. A consultation with assessment experts led us to choose a Q-methodology as the form for the PROM. A Q-methodology is used to gather information about a person’s opinions, beliefs, self-understanding, emotions, etc., by asking them to rank order stimuli such as statements or pictures according to their level of agreement or applicability to a person. This rank order forms a single gestalt entity of the subjectivity of a person on the specific topic that is being asked about (Watts and Stenner 2012). This feature of a Q-methodology fits well with the person-centered and holistic nature of chaplaincy. In a Q-methodology, the stimuli are sorted in a standardized grid, allowing for the assignment of scores to individual stimuli (see Figure 2). These Q-sorts are then analyzed with factor analysis, leading to a typology of opinions, emotions, beliefs, self-understandings, etc. In relation to outcome assessments in chaplaincy, if the Q-method is used in a pre–post design, the factor analysis would show the profiles of the effects of chaplaincy care (Morea 2022).

Figure 2.

The sorting grid with a sort from the pilot study among chaplaincy students, translated from Dutch by the author.

3.2. Selecting Outcomes and Statements

The interviews with the clients, the second focus group sessions with the learning networks, and discussions within the research group showed that it was difficult to fully separate the four goal domains found in the first focus group sessions. This finding underscored the usefulness of a Q-methodology as the form for the PROM, because this approach also assumes that the subjectivity around multi-dimensional topics ultimately forms one gestalt entity. Thus, no distinctions were made between the outcomes on the four goal domains of worldview development, coping with life events and circumstances, relational affirmation, and connectedness and transcendence were represented.

Of the 128 outcomes chosen by the learning networks as representative of the four goals, 20 outcomes/categories were selected because they were chosen at least 13 times. These are displayed in Table 2, first column. Examples are ‘Being able to bear circumstances in life’, ‘Moving forward’, and ‘(Re)connecting with people’. In line with a Q-methodology, we kept the formulation of the outcomes as close as we could to how they were expressed by the participants in the focus groups. The outcomes show a broad spectrum of capabilities, cognitions, emotions, relations, and experiences.

Because of the verbal nature of the data and the wide variety of outcomes, we decided to use only statements in the instrument instead of pictures or statements with a picture that would perhaps be more accessible to people with lower Dutch language skills. To determine the statements, we re-examined the interviews with the clients and gathered as many statements as possible that reflected the selected outcomes. Some interview statements were rephrased or summarized into one-sentence statements by the first and second authors. In total, 55 one-sentence statements were generated. Because some of the selected outcomes seemed to represent well-known psychological states and constructs, existing questionnaires were also screened for statements, but no new statements were found that adequately reflected the outcomes.

To keep the number of statements manageable for users of the NUGV, we chose a limited number of phrases that we felt best represented the meaning of the outcomes (n = 25; see Table 2, second column). All of the statements have been phrased as I-statements, which represent the current state of the person. For example, for the outcome ‘Having a broader perspective on events’, two statements were formulated: ‘I feel I am the only one going through this’ and ‘I understand why things have gone this way’. This is in line with the intentions of PROMs, which are used to assess differences in states pre- and post-treatment, and the intentions of a Q-methodology, which is used to examine subjectivity.

3.3. Constructing the NUGV

Because the outcomes represent such diverse dimensions of experience, we decided to use the question ‘How well do the statements fit with how you are doing?’ as the basic prompt for the sorting task. Given the small number of statements, the ranking distribution in the first version of the NUGV ran from −3 to +3, with −3 indicating ‘least fitting’, 0 indicating ‘don’t know, somewhat fitting’, and +3 indicating ‘most fitting’. In a Q-methodology, a brief interview takes place after the sorting task, in which the respondent can explain more about their sort.

3.3.1. Acceptability and Face Validity

Both the members of the client council and the majority of the workshop participants indicated that the NUGV was acceptable, because they enjoyed the Q-sort task and were happy that we had not designed a questionnaire. They felt that the statements were relatable to their own experiences with chaplaincy and to concepts of meaning making, identity, and well-being. A few participants did raise the question of how comprehensive the statements were for the different dimensions of chaplaincy. Several members of the client council commented on the lack of a timeframe for the prompt: was the client required to sort according to the current state or the past few days/weeks/months? We did not immediately take up this feedback, but tested it again at the workshop.

At the workshop, several participants commented that the instrument was insightful for both the assessor and the client, and that the post-sorting conversation was meaningful and in-depth. We had presented the instrument as suitable for research and, potentially, for individual monitoring. However, various chaplains in the workshop commented that the assessment as scripted was not well-suited for the application of the instrument for individual monitoring, because they experienced it as too distant, restrictive, and long. The script was based on the application of the instrument with a research goal. The 20 min given for the completion of the assessment was sufficient for most participants.

3.3.2. Clarity

An important comment of the client council was that statements such as ‘I feel I can be myself’ and ‘I feel I’m being seen as a human being’ did not make sense, because they contained a feeling about a thought. Therefore, these phrases were removed from the statements, changing them to, for example, ‘I can be myself’ and ‘I’m being seen as a human being’. It was further suggested to announce earlier in the instructions that the task included 25 statements and to add the question ‘To who or what do you attribute any changes in how you feel?’ to the interview post-test. All these points were adjusted before further testing at the workshop.

At the workshop, further comments were made on the clarity or manageability of the instrument. Many of the comments concerned the ability of clients to use the instrument. Eight participants suggested adding pictures to the cards to make them more attractive and understandable for less-literate clients. Five people indicated that the instrument ‘asks a lot of people’. Based on conversations with a few of the participants, we have understood this comment to mean that sorting the cards—to determine whether a statement applies and to what extent—requires quite some reflective capacity. The participants, therefore, expected that it would not work well with people who were amid a very emotional situation or with people with cognitive disabilities. The sorting grid was also experienced as too restrictive by some participants (two groups ignored this instruction), and it raised questions about how manageable the sorting task would be for people who experience much ambivalence. The sorting grid also raised questions about the meaning of the numbers, with 0 being interpreted as ‘neutral’ and the other numbers experienced as a Likert-type scale. Some participants felt slightly overwhelmed by the 25 statements and suggested that the client be allowed to choose a few statements from the 25 and sort only those.

3.3.3. Changes Made

Based on this evaluation, a timeframe of the past three days (the day before yesterday, yesterday, and today) was added to the prompt. This allows for a more stable evaluation of the state of the person, but also one that closely reflects the current state. The participants were able to complete the sorting task in 20 min, six of the eight groups were able to stick to the grid, and they felt that this sorting was meaningful, so the sorting of the full set of 25 cards and the sorting grid were maintained. In line with general theory about a Q-methodology, we expect this to contribute to the validity and interpretability of the results. However, we did remove the numbers from the top of the sorting grid, maintaining only the qualitative indicators of the meaning of the extremes: ‘least fitting’ and ‘most fitting’. We expect this to contribute to the sorting process and avoid associations with Likert-type scales. The final version of all the statements is shown in the last column in Table 2, and Figure 2 shows the final sorting grid.

3.3.4. Pilot Studies

Completion of the online sorting task in the pilot studies took on average 6 to 14 min, including questions on the background characteristics of the participants and a written post-sort interview. One participant in the pilot study on the writing intervention struggled with the task, but the other participants in either study did not comment that they found the task very difficult. This suggests that the instrument was manageable for these groups. Some participants indicated they missed statements, but the statements that were missed were very close to existing statements (such as, ‘I know who I am’) or were considered outside the scope of chaplaincy care (such as statements about physical well-being), so we did not make changes in response to this feedback. The data analysis using Brown centroid factor analysis with Varimax rotation in KADE v1.3.1 (Banasick 2019) resulted in meaningful factors or profiles for the pre- and post-test, and the observed changes in the profiles matched the descriptions of the participants of the process they had undergone during the writing intervention or spiritual autobiography course. This seems to suggest the interpretability and validity of the NUGV are sufficient. The descriptions of the participants were quite short because of the written format, which did make the interpretation of the findings more difficult. In-person administration of the instrument would lead to richer data.

To illustrate what the findings of such an analysis might look like, we describe a selection of the findings from the pilot study of the writing intervention for women who had experienced sexual abuse. In the pilot study, we found two profiles at the pre-test (T0) and three profiles at the post-test (T1). Examination of the changes among the participants showed that two people with profile 1 at T0 were on profile 2 at T1. The pre- and post-test statement rankings of these two people were highly correlated (r = 0.53 and r = 0.58). The profiles were also strongly related (r = 0.63). These correlations reflect some stability in their experience. However, comparing the two profiles showed that they felt more connected to significant others (s5, T0 rank 0, T1 rank +2) and to themselves (s7, T0 − 2, T1 + 1; s14, T0 + 1, T1 + 3), although they still did not feel connected to their feelings (s17, T0 and T1 − 3). One of these participants wrote the following: “I’m feeling confused, but at least I’m feeling something again. In the previous test I was completely cut off and frozen in time. Now I’m searching for what I need and what is happening”.

One person with profile 1 at T0 was on profile 3 at T1. The correlation between the statement rankings at the two time points was low (r = 0.23), as was the correlation between the profiles (r = 0.19), suggesting quite some change. Comparing the two profiles showed that, in particular, acceptance of the situation became less fitting to how they felt (s4, T0 0, T1 − 2; s9, T0 + 3, T1 0), but they felt more connected to themselves (s11, T0 − 1, T1 + 2; s7, T0 − 2, T1 + 1) and their feelings (s17, T0 − 3, T1 + 2). The person wrote the following: “I’m less afraid of moving toward my feelings and expressing them. It is still difficult to take care of myself and stay connected to others. But I’m a bit prouder of myself and how I’m doing!”.

4. Discussion

Chaplaincy needs an outcome measure that closely reflects its goals, which helps to show effects of care and improve its quality by showing to what extent the type of care is meeting its objectives. Therefore, we have developed the Dutch Chaplaincy Outcome Measure (NUGV). This measure is a Q-method sorting task consisting of 25 statements that reflect outcomes of chaplaincy in primary, outpatient, and community care as defined by chaplains, clients, healthcare workers, researchers, and various other colleagues of chaplains. The first tests with the NUGV have indicated it is acceptable, manageable, clear, interpretable, and valid.

Though the instrument was developed in the context of primary, outpatient, and community care, we noticed in the focus groups that chaplains who worked both in inpatient and outpatient settings sometimes did not fully differentiate between clients in these settings. This suggests that the goals and outcomes identified in this study might represent both settings. Conversations about our findings with chaplains and chaplaincy researchers from inpatient contexts showed that the dimensions and outcomes were very recognizable to them as well. Thus, the instrument might also be appropriate for other settings. Further validation studies are needed to test this.

Limitations

Several limitations of both the study and the instrument should be considered. First, this study was conducted in the Netherlands. The organization of and approach to chaplaincy can differ quite substantially between countries due to differences in systems of healthcare and religion (Danbolt et al. 2019). It is, therefore, not unlikely that in other countries other goals and/or outcomes of chaplaincy might be of importance.

Second, not all the relevant work contexts were represented in this study, such as chaplaincy for veterans and for people living in poverty, which may affect the representativeness of the instrument for outcomes of chaplaincy. On the other hand, the study by Rosie et al. (2025), in which chaplaincy for veterans was included, showed that there were negligible differences between the contexts in their choices of goals and outcomes.

More generally, even though the NUGV was found to be acceptable, outcome assessment in itself might not be acceptable in all settings. Several participants in the study commented on this and the learning network on chaplaincy for veterans within the Knowledge Workplace requested not to use the data that we had gathered with them for the development of the PROM. The participants of this learning network explained that the primary value of chaplaincy was that they did not have to meet treatment goals and that the chaplain was a neutral party. They did not want the contact with the chaplain to be instrumentalized by the army. Participating in the development of a PROM felt to them like it would sanction the quality assessment of chaplaincy by the military and, with that, a reduction in the free space that chaplaincy offers. We received a similar response when exploring possibilities for a pilot study in a prison. The chaplains felt that using an outcome assessment would compromise their role of representatives of humanitarianism. These responses express the goals of chaplaincy at a social level, rather than an individual level. Various authors have expressed that the sanctuary function of chaplaincy is also an important goal of the profession: to ensure opportunities for people to freely practice their religion and worldview, for confession, and for confidential and non-judgmental encounters (Carey et al. 2016; Jacobs et al. 2024; Timmins et al. 2018; Visser et al. 2023). To some extent, outcome assessment and effect research might be considered to be opposed to this goal, because assessment to understand how chaplaincy affects individual functioning is associated with a sense of normativity and a breach of confidentiality. Further reflection is needed on the relationship between these moral or normative frameworks and what their implications are for outcome assessment and effect research in chaplaincy.

Another question about the suitability of the instrument concerns the fact that it is language-based and the sorting process potentially takes more time and mental effort than completing a questionnaire. It might, therefore, not be suitable for all types of clients seen by chaplains, even though both the current study and other research show that it is generally also experienced as more engaging than a questionnaire and does not take an unreasonable amount of time to complete (ten Klooster et al. 2008). A Q-methodology with written statements has also been used with various populations that might be expected to have difficulties with language-based and longer tasks, including first- and second-generation migrants, people with schizophrenia or psychoses, nursing home residents, adolescents with chronic conditions, and people with dementia (Churruca et al. 2021). In addition, we have kept the statements as close as possible to expressions used by the interview participants, who included people from various backgrounds and ages. Nevertheless, when using the NUGV in a new study, it is advised to test it with a few people from the intended study population to explore if the method is suitable for them and what additional support they might need when using the instrument. In line with this recommendation, the pilots showed that it is preferable to conduct the NUGV in person rather than online. In-person administration offers the opportunity to clarify procedures and statements if people struggle. In-person use also facilitates richer data from the post-sorting interview to aid in the interpretation of the profiles.

Finally, the intention of the study was to develop an instrument that matched the goals of chaplaincy. We seem to have been successful in this, given that the instrument represents outcomes for four overarching goals—worldview development, coping with life events and circumstances, relational affirmation, and transcendence and connectedness—that are also mentioned most often as goals of chaplaincy in the Dutch chaplaincy literature (Visser et al. 2023). We also recognize these dimensions in the outcomes assessed in the Lothian PROM (Snowden and Telfer 2017), the only other PROM developed specifically for chaplaincy. An important advantage of the NUGV over the Lothian PROM is its scope: the NUGV includes 25 statements compared to 4 in the Lothian PROM, thereby spanning a wider range of outcomes, and the Q-methodological basis of the NUGV allows for a more nuanced understanding of the effects of chaplaincy than the Likert scale of the Lothian PROM.

However, this does not necessarily mean that the outcomes that are assessed are specific to chaplaincy. The outcomes and statements in the NUGV represent a large variety of aspects of human functioning in the domains of worldview, coping, self-esteem, identity, emotion processing, sense of belonging, social support, and more. It is not unreasonable to expect that care professionals other than chaplains affect such outcomes as well. In many ways, this also makes sense given that spirituality is often understood as entwined with the physical, psychological and social dimensions of life; spirituality shapes and is shaped through our physical, psychological, and social experiences (Smeets and Manley 2006; Sulmasy 2002). But if this is so, can studies using the NUGV tell us anything else about chaplaincy other than whether it is meeting its own goals? To answer this question, studies are needed that examine whether other care professionals would also consider the aspects covered in the NUGV sufficient outcomes for their work and studies that compare findings on the NUGV between chaplaincy and other types of care.

Some studies suggest that the primary unique feature of chaplaincy is its person-centered and accepting attitude, in contrast to a more symptom-centered and treatment-oriented attitude experienced with other care providers (Kirchoff et al. 2021; Tan et al. 2022; Tunks Leach et al. 2020, 2022). This might suggest the hypothesis that profiles on the NUGV will show more changes in aspects related to relational affirmation in response to chaplaincy care compared to other types of care.

The different focusses of the care professions also suggest that chaplains might strive for outcomes on a different level than, for example, psychologists or social workers. A psychologist and their client might not be satisfied with ‘having words to express how I feel’ and ‘understanding why things have gone this way’. To them, this might just be a step toward the final goal of, for example, experiencing happiness in a relationship (because they are able to express how they feel and understand why things have gone this way), whereas for a chaplain and their client such insights into feelings and one’s situation are enough to finalize their contact. This being the case, the NUGV might also be chaplaincy-specific at the level at which the outcomes are formulated. These hypotheses will need to be tested in future research.

To conclude, the Dutch Chaplaincy Outcome Measure (NUGV) is a promising standardized mixed-methods instrument for outcome or effect research in chaplaincy that reflects outcomes that patients, chaplains, and other professionals have experienced in chaplaincy in primary, outpatient, and community care. The instrument can be used by trained researchers and takes about 20 min to complete in person. More research is needed on the construct validity and specificity of the outcomes, as well as on the use of the instrument in inpatient settings and among people with lower language and cognitive capabilities. In the future, it would be worthwhile to explore use of the NUGV for purposes other than research, such as internal quality assessment or as a conversation starter to explore the aims of chaplaincy encounters between clients and chaplains.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.V. and A.D.; methodology, A.V., A.D. and C.S.; formal analysis, A.D., X.J.S.R. and A.V.; investigation, A.D., X.J.S.R. and M.v.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, A.V.; writing—review and editing, A.D., X.J.S.R., C.S., M.v.Z., H.M., E.O. and G.J.; visualization, A.V.; supervision, A.V., C.S. and G.J.; project administration, A.V., A.D. and X.J.S.R.; funding acquisition, G.J., H.M., E.O., A.V. and C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was financed by ZonMw, project number: 10050011910009.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the research ethics committee of the University for Humanistic Studies (protocol code: 2021-20, date of approval: 1 December 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available at https://dataverse.nl/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.34894/RNS4YI (accessed on 3 June 2025).

Acknowledgments

This publication is a result of the Knowledge Workplace on Meaning and Spiritual Care [Kenniswerkplaats Zingeving]. The Knowledge Workplace is a collaboration between research, education, and practice, aiming at the development and collection of knowledge around spiritual care in primary, outpatient, and community care. We thank all the people involved for their invaluable contributions to this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Note

| 1 | In the north of the Netherlands the extraction of natural gasses has been causing earthquakes since 1986. In 2013, the number of earthquakes a year with a magnitude of over 1.5 on the Richter scale reached a peak of 30 earthquakes. The number of small earthquakes was highest in 2017, with over 120 tremors recorded that year. There has been a decrease in the number of tremors since then (Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute n.d.). The earthquakes have caused material, psychological, and social damage in the region, which long went unnoticed by the Dutch government (Stroebe et al. 2021). In 2014, the Church and Earthquake platform was founded by several churches in the region, to provide spiritual support and draw attention to the problems. In 2018, this culminated in a government subsidy for the employment of two chaplains (de Kraker-Zijlstra et al. 2021). Currently, eight chaplains are active in the region, who provide care at both individual and community levels (GVA Groningen n.d.). |

References

- Austin, Philip, Jessica Macdonald, and Roderick MacLeod. 2018. Measuring Spirituality and Religiosity in Clinical Settings: A Scoping Review of Available Instruments. Religions 9: 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banasick, Shawn. 2019. KADE: A desktop application for Q methodology. Journal of Open Source Software 4: 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berning, Joel N., Armeen D. Poor, Sarah M. Buckley, Komal R. Patel, David J. Lederer, Nathan E. Goldstein, Daniel Brodie, and Matthew R. Baldwin. 2016. A Novel Picture Guide to Improve Spiritual Care and Reduce Anxiety in Mechanically Ventilated Adults in the Intensive Care Unit. Annals of the American Thoracic Society 13: 1333–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carey, Lindsay B., Timothy J. Hodgson, Lillian Krikheli, Rachel Y. Soh, Annie-Rose Armour, Taranjeet K. Singh, and Cassandra G. Impiombato. 2016. Moral Injury, Spiritual Care and the Role of Chaplains: An Exploratory Scoping Review of Literature and Resources. Journal of Religion and Health 55: 1218–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churruca, Kate, Kristiana Ludlow, Wendy Wu, Kate Gibbons, Hoa Mi Nguyen, Louise A. Ellis, and Jeffrey Braithwaite. 2021. A scoping review of Q-methodology in healthcare research. BMC Medical Research Methodology 21: 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damen, Annelieke, Anja Visser-Nieraeth, Carmen Schuhmann, Sujin Rosie, Marjo van Zundert, Gaby Jacobs, Hanneke Muthert, and Erik Olsman. 2024. Doelen van geestelijke verzorging in de thuissituatie. Tijdschrift Geestelijke Verzorging 27: 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Danbolt, Lars J., Valerie DeMarinis, Mats Rydinger, and Hetty Zock. 2019. Chaplaincy—How and why. Tidsskrift for Praktisk Teologi 36: 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Kraker-Zijlstra, Anieljah, Hanneke Muthert, Hetty Zock, and Martin Walton. 2021. Attention for meaning-making processes: Context and practice of spiritual care in the earthquake area of Groningen. NTT Journal for Theology and the Study of Religion 75: 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ruiter, Ellen. 2024. Zin Schrijven. Een Onderzoek Naar de Zingevende Kracht van Schrijven voor Slachtoffers van Seksueel Misbruik. Master’s thesis, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- GVA Groningen. n.d. Het GVA Team. Available online: https://gvagroningen.nl/het-gva-team/ (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Iler, William L., Don Obenshain, and Mary Camac. 2001. The Impact of Daily Visits from Chaplains on Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD): A Pilot Study. Chaplaincy Today 17: 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, Gaby, Carmen Schuhmann, and Iris Wierstra. 2024. Healthcare chaplains’ conflicting and ambivalent positions regarding meaning in life and worldview. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy 30: 107–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchoff, Robert W., Beba Tata, Jack McHugh, Thomas Kingsley, M. Caroline Burton, Dennis Manning, Maria Lapid, and Rahul Chaudhary. 2021. Spiritual Care of Inpatients Focusing on Outcomes and the Role of Chaplaincy Services: A Systematic Review. Journal of Religion and Health 60: 1406–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krippendorff, Klaus. 2019. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutfallah, Susan, and Lori Buchanan. 2019. Quantifying subjective data using online Q-methodology software. The Mental Lexicon 14: 415–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, Gordon W. 2019. Primary care chaplaincy: An intervention for complex presentation. Primary Health Care Research & Development 20: e69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, Sara S., Michelle King, and Mary P. Tully. 2016. How to use the nominal group and Delphi techniques. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy 38: 655–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McSherry, Wilfred, Adam Boughey, and Peter Kevern. 2016. “Chaplains for Wellbeing” in Primary Care: A Qualitative Investigation of Their Perceived Impact for Patients’ Health and Wellbeing. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy 22: 151–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morea, Nicola. 2022. Investigating change in subjectivity: The analysis of Q-sorts in longitudinal research. Research Methods in Applied Linguistics 1: 100025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterman, Amy H., George Fitchett, Marianne J. Brady, Lesbia Hernandez, and David Cella. 2002. Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being scale (FACIT-Sp). Annals of Behavioral Medicine 24: 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosie, X. J. S. (Sujin), Anja Visser, Annelieke Damen, Erik Olsman, Carmen Schuhmann, Gaby Jacobs, Marjo van Zundert, and Hanneke Muthert. 2025. Goals and outcomes of chaplaincy in varying outpatient, primary, and community care contexts. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute. n.d. Aardbevingen Door Gaswinning. Available online: https://www.knmi.nl/kennis-en-datacentrum/uitleg/aardbevingen-door-gaswinning (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Smeets, Wim, and M. Manley. 2006. Goals and Tasks of Spiritual Care. In Spiritual Care in a Hospital Setting. Leiden: BRILL, pp. 145–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowden, Austin, and Iain Telfer. 2017. Patient Reported Outcome Measure of Spiritual Care as Delivered by Chaplains. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy 23: 131–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroebe, Katherine, Babet Kanis, Justin Richardson, Frans Oldersma, Jan Broer, Frans Greven, and Tom Postmes. 2021. Chronic disaster impact: The long-term psychological and physical health consequences of housing damage due to induced earthquakes. BMJ Open 11: 40710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulmasy, Daniel P. 2002. A Biopsychosocial-Spiritual Model for the Care of Patients at the End of Life. The Gerontologist 42: 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Heather, Bruce Rumbold, Fiona Gardner, Austyn Snowden, David Glenister, Annie Forest, Craig Bossie, and Lynda Wyles. 2022. Understanding the outcomes of spiritual care as experienced by patients. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy 28: 147–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ten Klooster, Peter M., Martijn Visser, and Menno D. T. de Jong. 2008. Comparing two image research instruments: The Q-sort method versus the Likert attitude questionnaire. Food Quality and Preference 19: 511–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terwee, Caroline B., Philip van der Wees, and Sandra Beurskens. 2015. Handreiking voor de Selectie van PROs en PROMs [Suggestions for the Selection of PROs and PROMs]. Utrecht: Nederlandse Federatie van UMC’s. [Google Scholar]

- Timmins, Fiona, Sílvia Caldeira, Maryanne Murphy, Nicolas Pujol, Greg Sheaf, Elizabeth Weathers, Jacqueline Whelan, and Bernadette Flanagan. 2018. The Role of the Healthcare Chaplain: A Literature Review. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy 24: 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tunks Leach, Katie, Joanne Lewis, and Tracy Levett-Jones. 2020. Staff perceptions on the role and value of chaplains in first responder and military settings: A scoping review. Journal of High Threat & Austere Medicine 2: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunks Leach, Katie, Paul Simpson, Joanne Lewis, and Tracy Levett-Jones. 2022. The Role and Value of Chaplains in the Ambulance Service: Paramedic Perspectives. Journal of Religion and Health 61: 929–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkerk, Eva, Marjolein Verbiest, Simone van Dulmen, Philip van der Wees, Caroline Terwee, Sandra Beurskens, Dolf de Boer, Carla Bakker, Ildikó Vajda, and Marloes Zuidgeest. 2017. De PROM-Toolbox: Tools voor de Selectie en Toepassing van PROMs in de Gezondheidszorg [The PROM-Toolbox: Tools for the Selection and Application of PROMs in Healthcare]. Diemen: Zorginstituut Nederland. [Google Scholar]

- Visser, Anja. 2019. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in healthcare chaplaincy: What, why and how? Tidsskrift for Praktisk Theologi: Nordic Journal of Practical Theology 2: 90–99. [Google Scholar]

- Visser, Anja, Annelieke Damen, and Carmen Schuhmann. 2023. Goals of chaplaincy care: A scoping review of Dutch literature. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy 29: 176–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, Simon, and Paul Stenner. 2012. Doing Q Methodological Research: Theory, Method and Interpretation. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).