Abstract

In this study, we explored how people experience love and how these experiences are linked to their overall mental health, well-being, and spirituality. A total of 1499 U.S. adults completed a survey that measured six different aspects of love. Using Latent Profile Analysis (LPA), we found evidence in support of four distinct profiles: High Love, Above-Average Love, Below-Average Love, and Low Love. The High Love group, which was characterized by particularly strong feelings of religious love, reported the highest levels of life satisfaction, gratitude, and positive emotions, as well as the lowest levels of anxiety and depression. The Above-Average Love group showed moderately high levels of love with some emphasis on spirituality, while the Below-Average Love and Low Love groups experienced lower overall levels of love and spiritual connection, along with poorer mental health outcomes. Our findings suggest that a deep sense of love—especially when it involves a connection to a higher power—may be a crucial factor in promoting mental health and life satisfaction.

1. Introduction

Love is quintessential to the human experience and has recently been the subject of systematic scientific inquiry. Social scientists have developed frameworks and instruments to measure subjective experiences of love, progressing from unidimensional to increasingly nuanced multidimensional conceptualizations. Early empirical investigations focused on distinguishing love from related constructs. Rubin (1970) pioneered love research by differentiating “love” from “liking”, characterizing love through three essential components: affiliative dependency, predisposition to help, and exclusiveness or absorption (p. 266). His early work set the stage for studies seeking to capture the complexity of love in more nuanced ways. For instance, Berscheid and Walster (1974) proposed a dual-factor model, distinguishing passionate love—marked by physiological arousal and intense emotion—from companionate love, defined by affection and attachment. Sternberg (1986) expanded this framework into a tripartite theory of love encompassing attachment, intimacy, and commitment. Around the same time, Shaver et al. (1987) offered a prototype approach and identified key forms of love such as affection, lust, and longing while Fehr (1988) highlighted everyday qualities like trust, caring, honesty, and friendship as foundational to what people associated love with. Further enriching this discussion and drawing on Lee’s typologies of love (Lee 1977), Hendrick and Hendrick (1986) identified six primary styles of love based on Greek terms: eros (passionate), storge (friendly), pragma (practical), mania (obsessive), agape (unconditional), and ludus (playful). Aware of the complexity and nuanced meanings, researchers have attempted to integrate and synthesize these various definitions and approaches. For example, Sternberg and Grajek (1984) postulated a general factor of love, and found that love consists of “primarily a unifactorial entity with possible subfactors” (p. 327) and that the “structural composition of love is surprisingly similar across different close relationships” (p. 327). Love, in Sternberg and Grajek’s (1984) description, involves interpersonal communication, sharing, and support along subcomponents that include an understanding of the other, the sharing of ideas and information, of feelings, the exchange of emotional support, the experience of personal growth, of helping, of making the other feel needed. Likewise, and reviewing the literature at large, Aron and Westbay (1996) extended the prototype approach to love and found three primary latent dimensions of prototypical love: intimacy, which they rated as the most important, commitment, of intermediate importance, and passion, rated as the least important. Finally, Graham (2011) conducted a meta-analysis and factor analyses to extract the core aspects of love from the empirical literature and found three higher-order factors: love, romantic obsession, and pragmatic friendship, but concluded only love (“l”) matched theoretical notions of love per se held in romantic relationships.

Despite these advances and disparate renditions and descriptions of love, a significant gap remains in the social science literature at large: the general understanding of love’s spiritual, mystical, and transpersonal dimensions remains sparse and understudied. Though compelling, the bulk of previous social science theories, measures, and research pigeonholes love into, mostly, its romantic component. Few researchers have done otherwise. By contrast, and drawing upon diverse empirical research from biology, psychology, and public health, Post (2007) showed that altruistic love—generous acts and genuine care for others—is significantly related to happiness, meaning, mental well-being, and even physical health, including reduced mortality rates. Post’s (2007) findings suggest that love, when expressed beyond personal or romantic contexts and oriented toward altruistic goals, has profound implications for individual well-being. Along these lines, Sorokin (1954, 2015) addressed the spiritual, mystical, and transpersonal dimensions through a comprehensive framework and identified seven primary types of love: biological, social, psychological, religious, ontological, ethical, and physical love. Biological love referred to love expressed sexually, passionately, and through the pursuit of pleasure; social love addressed love in interpersonal dimensions; psychological love implied feeling loved as one is by others; religious love referred to the experience of feeling embraced and accepted by God or a higher power; ontological love involved feeling that love composes the fabric of life and the universe; ethical love emphasized the belief that love is the morally appropriate way to be, to act; physical love highlighted love found in the cosmic order and in the self-organizing principles ruling an integrated universe. Sorokin’s framework uniquely reaches beyond the traditional attachment-based, passion-focused conceptualizations to encompass broader manifestations, including love of life, divine love, and philanthropy.

Building on Sorokin’s broader theory of love, the present study examines such distinct dimensions of love and their relationship with well-being, anxiety, depression, and spirituality. From previous research, theologians and social scientists have established love’s importance for health and well-being (Ai and Hall 2011; Esch and Stefano 2005; Levin 2001; Traupmann and Hatfield 1981). However, the differential impacts of such distinct love dimensions, especially those of a religious, spiritual, and transpersonal element, remain understudied. Using Sorokin’s Multidimensional Inventory of Love Experience (SMILE; Levin and Kaplan 2010), this study aims, first, to identify distinct profiles of love experiences in a U.S. sample; second, to examine associations between these potential profiles and indicators of well-being, psychopathology, and spirituality, and third, to investigate the relative importance of different love dimensions in distinguishing between love profiles. To our knowledge, the present investigation is the first to perform a comprehensive examination of love profiles using the SMILE and latent profile analyses, offering potential insights into how different patterns of love experience relate to psychological and spiritual well-being.

This investigation pursues three primary aims. The first aim is to examine the interrelationships among Sorokin’s (1954, 2015) six dimensions of love as captured by the validated Sorokin Multidimensional Inventory of Love Experience (SMILE) questionnaire (Levin and Kaplan 2010): biological, psychological, social, religious, ethical, and ontological love. Understanding these interrelationships may provide insight into how different aspects of love experience may reinforce or compete with each other in individuals’ lives. The second aim is to identify distinct profiles of love experiences in a U.S.-based sample. While previous research has typically examined love dimensions independently, this person-centered approach allows us to understand how these dimensions naturally combine (or not) within individuals. The third aim is to investigate how these love profiles differentially relate to well-being, psychopathology, and spirituality. This aim extends previous research by examining how different configurations of love dimensions, rather than individual, interpersonal and intrapersonal dimensions alone, relate to psychological, well-being and spiritual outcomes.

To achieve these aims, we employed a systematic analytical approach. First, we conducted correlation analyses to examine the magnitude and direction of relationships among Sorokin’s six love dimensions as captured in the SMILE (Levin and Kaplan 2010). We then utilized latent profile analysis (LPA) to identify naturally-occurring groups of individuals with similar patterns across love dimensions. Finally, we examined how membership in these profiles related to various indicators of psychological and spiritual well-being. Based on recent profile analyses demonstrating population heterogeneity across multidimensional constructs (De Souza Marcovski and Miller 2022; Phillips 2021), we developed two primary hypotheses. First, we hypothesize that distinct, meaningful profiles of love may emerge from our analysis, reflecting different patterns of emphasis across Sorokin’s six dimensions contained in the SMILE. Second, we hypothesize that these profiles may show differential associations with well-being outcomes, specifically: (a) profiles characterized by higher overall love indices would demonstrate stronger positive associations with well-being, flourishing, life satisfaction, and spirituality, while showing lower levels of anxiety and depression; (b) profiles characterized by lower overall love indices may show the opposite pattern, with lower levels of well-being indicators and higher indices of anxiety and depression. To the best of our knowledge, this systematic investigation represents the first attempt to identify and characterize love profiles using Sorokin’s comprehensive framework, potentially offering valuable insights into how different patterns of love experience relate to psychological and spiritual well-being.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Procedure

A sample of 1499 adults (age range: 18–80 years) from the United States participated in this study through Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk). Prior to joining our study, participants were informed about the study’s focus on quality of life, well-being, spirituality, and psychological distress. To ensure data quality, we implemented multiple verification procedures, including attention checks, IP address verification to confirm U.S. presence, time stamps to monitor survey completion patterns, and response-time analyses regarding onset and completion. The dataset used in this study has been the basis for several prior publications on the themes of mental health and spirituality, including in McClintock et al. (2016), which examined distinct research questions. The study protocol adhered to ethical guidelines as established in the Belmont Report and the Helsinki Declaration for research on human subjects, and was approved by an Institutional Review Board.

2.2. Measures

Our assessment battery comprised three primary domains: love dimensions, psychological functioning (both positive and negative indicators), and spiritual and religious experiences. All measures demonstrated good to excellent internal consistency in our sample.

Love. The Sorokin Multidimensional Inventory of Love Experience (SMILE; Levin and Kaplan 2010) served as our primary measure. This 24-item instrument assesses six distinct dimensions of love using four items per dimension and a five-point Likert Scale. Love subscales included Biological, assessing pleasure-seeking, satisfaction, and the pursuit of rewarding experiences (α = 0.79), social, measuring unconditional love for friends and others (α = 0.76), psychological, evaluating subjective experiences of feeling loved (α = 0.76), ethical, assessing love-based moral behavior and virtuous action (α = 0.89), religious, measuring feeling embraced by a Higher Power or God (α = 0.98), and ontological, evaluating metaphysical beliefs about love’s role in existence (α = 0.84). Previous validation studies have demonstrated clear factor structure and significant intercorrelations among all subscales except biological love, which showed independence from other dimensions (Levin and Kaplan 2010).

Anxiety. The Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7; Spitzer et al. 2006) provided an assessment for anxiety symptoms (α = 0.93). The GAD-7 is a seven-item instrument that has shown excellent internal consistency and substantial evidence of diagnostic and criterion validity for anxiety.

Depression. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al. 2001) measured depressive symptomatology (α = 0.91). The PHQ-9 has excellent internal consistency and evidence of depressive disorders’ diagnostic validity among samples from the U.S. and around the world (Arroll et al. 2010; Costantini et al. 2021; Kroenke et al. 2001; Lotrakul et al. 2008).

Negative Affect. The negative subscale of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson et al. 1988) assessed current distress emotions (α = 0.92). Some of the emotions assessed included fearfulness, upset, irritability, and distress.

Gratitude. The Gratitude Questionnaire (Emmons et al. 2003; McCullough et al. 2002) measured thankfulness and appreciation (α = 0.82). The Gratitude Questionnaire is brief, unidimensional scale, based on a seven-point Likert scale assessing one’s gratefulness. Sample items include: “I have so much in life to be thankful for” and “I am grateful to a wide variety of people”.

Life Satisfaction: The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al. 1985) assessed global life satisfaction (α = 0.94). The SWLS scale is a widely used, five-item instrument measuring life satisfaction.

Subjective Vitality. The Subjective Vitality Scale (SVS; Ryan and Frederick 1997) evaluated perceived energy, vitality, and aliveness (α = 0.92). Sample items include “I feel alive and vital”, “I have energy and spirit”, “I look forward to each day”, and “I feel energized”.

Social Support: The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS; Zimet et al. 1988) assessed perceived support across family, friend, and significant other domains (Zimet et al. 1988; α = 0.95). Robust empirical research suggests that social support serves as an important buffer against negative emotions and stress (Zimet et al. 1990).

Positive Affect: The positive items within the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson et al. 1988) measured current positive emotional states (α = 0.91), including positive emotions such as joyfulness, cheerfulness, contentment, among others.

Spirituality: The Delaney Spirituality Scale (DSL; Delaney 2005; α = 0.94) assessed four dimensions of spirituality: ecological awareness (i.e., “I believe that nature should be respected”), self-discovery (i.e., “My life is a process of becoming”), relational spirituality (i.e., “I respect the diversity of people”), and sacred connection (i.e., “my faith in a higher power/universal intelligence helps me cope with the challenges of my life”).

Religious/Spiritual Meaning Krause’s (2003) six-item measure evaluating faith-based meaning in life (α = 0.97).

2.3. Demographics

Our sample (N = 1499) included consenting participants from the United States. Regarding racial and ethnic composition, the majority of participants identified as White (83.6%), with smaller representations of African American (8.3%) Hispanic (7.2%); East Asian (2%), Native American (1.4%), and South Asian (0.7%). Religious affiliations included Christian, (48.5%) non-religious (39.2%), Buddhist (2.4%), Jewish (1.3%), Muslim (0.9%) and Hindu (0.5%). The sample demonstrated relatively high education attainment: 9.7% held a graduate degree, 33.4% a bachelor’s degree, 28.9% some college education, 11% obtained an associate’s degree, 14% obtained up to a high school diploma, and only 0.7% had less than high school completion. Regarding contemplative practices, 24% reported regular engagement in mind–body or meditation practices, 15% of reported regular mind–body practice (e.g., yoga, chi-gong, tai chi) alone; 17% reported engaging in regular meditation practice (e.g., mindfulness, Zen, Christian prayer, etc.), while 9% reported engaging in both a mind–body contemplative practice and practicing meditation. The majority (76%) of participants reported having neither a meditation nor a mind–body practice.

2.4. Data Analyses

Our analytical approach proceeded in three phases: preliminary analyses, latent profile identification, and profile characterization. Initial data processing and descriptive analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS version 27. We examined completion rate, missing data patterns, and scale reliabilities, and assessed the demographic composition of our sample. The SMILE demonstrated high completion rates (97.8%) with no systematic patterns of missingness. Following tidyLPA (version 1.0.8; Rosenberg et al. 2019) software guidelines, we employed simple imputation to maximize data inclusion while preserving cases with missing values on outcome variables for profile comparisons. We also preserved participants with missing items in the love scales as we compared profiles across distal outcomes, except in cases in which participants showed missing values specifically on the distal outcomes analyzed. Intercorrelations among love dimensions were computed to examine preliminary relationships. Table 1 displays the correlation matrix. There were no patterns among participants who did not complete the items; upon visual inspection and analysis, we also found no patterns in the missingness in the data.

Table 1.

Two-tailed Pearson correlation indices among the six dimensions of love.

- Latent Profile Analysis

We conducted latent profile analyses (LPA) using the tidyLPA (version 1.0.8; Rosenberg et al. 2019) in R to identify distinct profiles of love. We used the six dimensions of love in the Sorokin Multidimensional Inventory of Love Experience (SMILE; (Levin and Kaplan 2010)) as profile indicators. Following established guidelines for LPA (e.g., Pastor et al. 2007), we computed and used the six sum scores of each love dimension as the indicators for our LPA.

We tested four model parameterizations with increasing complexity, allowing variances and covariances to vary or to remain equal, and covariances to vary, to remain equal, or to be kept at zero. Model 1 is the most constraining and restrictive: variances are held as equal across different profiles, and covariances between indicators are constrained to zero. Model 2 allows variances to vary among individual profiles, yet constrains covariances to zero. Model 3 maintains variances among indicators equal, but allows covariances to be estimated while maintaining them equally. Model 4, the least constrained and most complex, estimates both variances and covariances across profiles. Model selection criteria then included measures of, goodness-of-fit, interpretability of profiles. We examined the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC; Bozdogan 1987), the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC; Schwarz 1978), the bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (BLRT), and entropy as the main indices for model-selection. In addition, we employed alpha level 0.05 for decision-making and carefully considered profile distinguishability and theoretical coherence in final model selection.

- Profile Characterization

To examine profile differences across outcome measures, we conducted a series of statistical analyses. First, we conducted ANOVAs comparing profiles on spirituality, well-being, and anxiety and depression measures, using the most likely profile of membership as the independent variable. Second, we performed chi-square tests of independence to examine demographic associations with profile membership. When multiple comparisons were performed, we used Tukey’s HSD procedure along pair-wise multiple comparisons to control for Type I error inflation. This comprehensive analytical strategy allowed us to identify meaningful love profiles and to understand their relationships with important psychological and spiritual outcomes.

3. Results

Our analysis investigated three primary aims: examining interrelations among love dimensions, identifying distinct love profiles, and investigating associations between these profiles and psychological outcomes. As Table 1 demonstrates, analysis of the six SMILE dimensions revealed significant positive correlations among most love dimensions (0.197 ≤ r ≤ 0.724, p < 0.01), with one notable exception. Consistent with Levin and Kaplan’s (2010) findings, biological love showed no significant association with religious love (r = −0.011, p > 0.05) and demonstrated the weakest relationships with other dimensions (r ranging from 0.197 to 0.360). The strongest correlations emerged between ethical and ontological love (r = 0.724, p < 0.001), ontological and psychological love (r = 0.687, p < 0.001), and psychological and ethical love (r = 0.582, p < 0.001). These patterns suggest substantial overlap among the more abstract and internally oriented love dimensions, while biological love appears to function somewhat independently.

Latent profile analysis, in turn, revealed four distinct profiles of love experience, showing clear differentiation across most love dimensions. We evaluated models using established fit criteria (AIC, BIC, entropy) and theoretical interpretability. Model 3, which allowed free estimation of variances and covariances while equalizing them across profiles, demonstrated superior fit compared to more constrained parameterizations. The four-profile solution emerged as optimal based on multiple criteria, including a significant improvement in fit indices over solutions with fewer profiles, highest entropy values, indicating more precise classification, adequate group sizes (with over 20% per profile), and theoretical coherence. The four profiles identified were a High-Love (29.4% of the sample), an Above-Average (20.8%), a Below-Average (20.6%), and a Low-Love (29.2%) profiles.

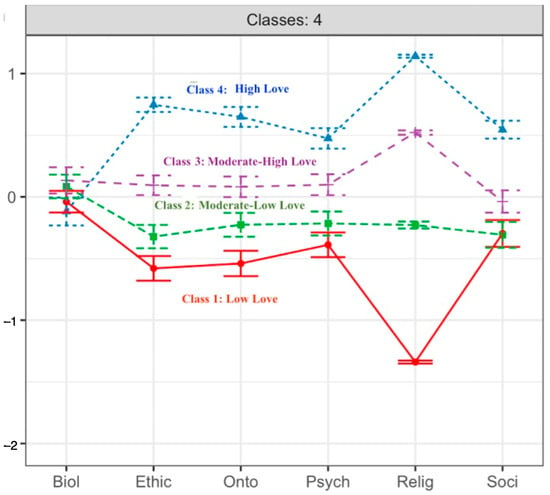

Table 2 displays results from our latent profile analyses for Model 1 and Model 3. (Parameterizations using Model 2 and Model 4 were non-computable and therefore unattainable because of the statistical complexity these two parameterizations demand and poor fit with the data.) The four identified profiles of love showed distinct patterns of love experience. We visually inspected emerging profiles for theoretical meaning. Figure 1 depicts the four-profile solution, with standardized means across the six dimensions of love. Subsequent analyses were conducted comparing these four profiles of love generated through Model 3.

Table 2.

Fit indices and LPA results including AIC, BIC, entropy, smallest profile class, and BLRT for Model 1 and Model 3 featuring profile solutions from 1 to 5 profiles.

Figure 1.

Line graph indicating the four-profile solution featuring standardized mean values (z) on the y-axis and each of the six dimensions of love as the LPA indicators on the x-axis. Note. Biol: biological love; Ethic: ethical love: Onto: ontological love; Psych: psychological love; Relig: religious love; Soci: social love. Bars represent 95% confidence intervals around the standardized mean value for a given indicator. Profile 1: Low Love (29.2%); Profile 2: Below-Average Love (20.6%); Profile 3: Above-Average Love (20.8%); Profile 4: High Love (29.4%).

Overall, 29.4% of participants presented in the pattern of elevated levels among almost all dimensions of love (0.47 ≤ z ≤ 1.14), except for biological love (z = −0.09), and especially elevated indices of religious love (z = 1.14). We labeled this profile “High Love”. Diametrically opposite, 29.2% of participants presented with low levels of love across most aspects of love (−1.34 ≤ z ≤ −0.04), except for biological love (z = −0.04) and with especially low levels of religious love (z = −1.34). We labeled this profile “Low Love”. In the middle, 20.8% of our sample displayed marginally above average indices across most dimensions of love (−0.04 ≤ z ≤ 0.51), except for religious love (z = 0.51), which was more pronounced than other aspects of love in this profile. We labeled this profile “Above-Average Love”. Finally, 20.6% of our sample showed low-average indices among five of six dimensions of love (−0.32 ≤ z ≤ −0.21), except for biological love (z = 0.08). We labeled this profile “Below-Average Love”. The four profiles of love displayed distinct levels across most dimensions of love when compared to each other via ANOVAs and pair-wise comparisons. The exceptions were biological love, which was indistinguishable among all four profiles, and psychological and social love, which were similar between the Low-Love and Below Average love groups, but different when comparing the High Love and the Above-Average Love with other profiles. Table 3 displays the means and standard deviations of the six dimensions of love for each of the four emerging profiles of love, where higher scores represent higher levels of love indicators.

Table 3.

Standardized means and standard deviations on love subscales for each multidimensional profile of love.

ANOVAs revealed significant differences among profiles across all outcome measures. The High Love profile, comprising 29.4% of the sample, demonstrated superior psychological adjustment, the highest levels of satisfaction with life (z = 0.33), gratitude (z = 0.57), and positive emotion (z = 0.42), the highest indices of religious meaning (z = 1.03) and personal spirituality (z = 0.88), as well as the lowest markers of depression (z = −0.23), anxiety (z = −0.17), and negative emotion (z = −0.18) among all four profiles. Findings among the other three profiles were more nuanced. While the Above-Average profile showed the second-highest levels of well-being indicators, they remained significantly lower than the High Love profile. The Below-Average and Low Love profiles showed similar, below-average levels across well-being measures.

A clear linear trend emerged across profiles in spiritual dimensions. The High Love profile demonstrated the highest levels of both religious meaning (z = 1.03) and personal spirituality (z = 0.88), followed by the Above-Average profile with moderate elevation (religious meaning: z = 0.44; spirituality: z = 0.32). The Below Average and Low Love profiles showed significantly reduced levels in both spiritual dimensions. Regarding anxiety and depression scores, the High Love profile uniquely demonstrated lower levels of depression (z = −0.23), anxiety (z = −0.17), and negative emotion (z = −0.18). Interestingly, the other three profiles showed no significant differences in psychological distress, suggesting that high levels of love across dimensions might serve as a particular buffer against psychological distress. Table 4 summarizes the means, the standard deviations, and the F statistic comparing means across profiles of love.

Table 4.

Means and standard deviations for standardized outcome measure by profile and F-statistic of ANOVA tests comparing four profiles of love under Model 3.

Demographic Associations

Demographic analyses revealed several notable patterns. Members of the High Love profile were significantly older (M = 37.94, SD = 11.99) than other profile groups. Furthermore, we found a clear linear relationship between profile membership and religious/spiritual importance, with the High Love profile reporting the highest religious importance (M = 3.37, SD = 0.82), followed by decreasing levels through Above Average (M = 2.64, SD = 0.94), Below Average (M = 1.73, SD = 0.93), and Low Love (M = 1.18, SD = 0.55) profiles. These findings suggest that age and spiritual orientation may play important roles in the development and expression of love across multiple dimensions.

4. Discussion

Love felt in relation to a Higher Power, God, the Divine, appears foundational to the broad range of forms of love for humanity. Specifically, our investigation identified four distinct profiles of love in a U.S. adult sample and examined their associations with psychological and spiritual well-being. Using latent profile analysis with data from 1499 participants who completed the Sorokin Multidimensional Inventory of Love Experience (SMILE; Levin and Kaplan 2010), we identified High Love, Above-Average, Below-Average, and Low Love profiles. In turn, these profiles showed distinctive patterns of relationship with well-being, psychopathology, and spirituality.

Three key findings emerged from our analyses. First, the six dimensions of love contributed unequally to profile differentiation. While biological love (i.e., pleasure-seeking and the pursuit of personal satisfaction) and social love showed minimal variation across profiles, religious love emerged as the strongest differentiating factor. This finding extends previous research on the epidemiology of love (Levin 2001, 2023) and aligns with literature demonstrating robust associations between religious love, spiritual coping, and well-being (Ano and Vasconcelles 2005). Recent research has shown that people, regardless of theological or conceptual belief in a Higher Power (as in the case of agnostics) who feel accepted and embraced by one report greater gratitude, life satisfaction, and self-esteem (Byerly 2023). Likewise, people who hold loving perceptions of God demonstrate robust and consistent higher levels of meaning and purpose in life (Stroope et al. 2013). Told another way, research shows that resistance to the presence of divine love and an anxious attachment in relation to God correlate negatively with well-being indicators (Byerly 2023).

The benefits of experiencing a positive image or perception of and attachment toward God has been established by research in relationship to positive religious coping (Abu-Raiya and Pargament 2015), secure attachment toward God (Beck 2006; Leman et al. 2018), and, as Stroope et al. (2013) reflected, within the relationship between one’s image of God and one’s self-image. Here, the study findings suggest that religious love—the perception of being accepted and embraced by God, a Higher Power—may serve as the most reliable single indicator of love for humanity, even across a gradation of types of human love.

Given the foundation of perceiving God’s love to psychological wholeness, it is not surprising that this study found a strong association between the higher love profiles on the one hand, and on the other hand, spiritual life, well-being and mental health. Participants in the High-Love profile, characterized by an integrated, love-centered worldview, demonstrated superior psychological adjustment and spiritual engagement. These participants reported extraordinary levels of religious love, suggesting they felt acceptance by a higher power. This pattern aligns with previous findings showing that the experience of divine love was associated with positive coping among cardiac surgery survivors facing existential challenges (Ai and Hall 2011). Additional research by Levin (2000, 2023) also summarized the salutary effects of love for physical and mental health, including negative associations with physical comorbidities such as angina and ulcers, chronic illness, and cancer mortality. The relationship between love and well-being finds further support in neuroendocrinological research demonstrating that loving cognition and behavior modulate autonomic nervous system function and regulate the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, potentially mitigating chronic stress effects (Esch and Stefano 2005). Additionally, oxytocin, often considered the neurobiological substrate for social bonding and love, may mediate between prosocial behavior and improved health outcomes (Poulin and Holman 2013). Finally, specific loving-kindness meditations, which invoke various dimensions of interpersonal warmth, empathy, interconnectedness and love, have been linked with significant reductions in anxiety, increases in prosocial behavior, relaxation, and self-efficacy (Galante et al. 2016), just as our High Love profile demonstrates.

Third, we observed a rich relationship between love profiles and psychological outcomes. Degree of spirituality showed a linear relationship with intensity of love profile membership. However, well-being and psychopathology each demonstrated non-linear associations with love profile membership. Only the High Love profile showed significantly lower anxiety and depression, suggesting a potential categorical effect or a threshold effect rather than a continuous relationship. This finding resonates with research indicating that spirituality may be particularly protective for individuals who rate it as “highly important” versus merely “important” or “not important” (McClintock et al. 2016; Miller et al. 2014). We reflect that those whose lives center around existential questions and spiritual reflection and who develop a spiritual view of human existence as non-contingent on outwardness, as holding inherent dignity, may also present with the highest levels of love. Perhaps cultivating strong feelings of and beliefs about love as central to one’s life may promote well-being, reduce psychopathology, anxiety, and depression, and manifest as increased spirituality.

Our findings also mark an important departure from previous social science research on love. By examining beliefs and experiences of love, particularly ontological, ethical, and spiritual dimensions, we demonstrate that individuals’ fundamental experiences of love are significantly associated with their psychological well-being. This perspective aligns with frameworks linking core beliefs and worldview with coping and well-being (Lewis Hall and Hill 2019). The clinical literature has long recognized the importance of addressing core beliefs in therapeutic approaches, including in cognitive behavioral therapy (Dozois et al. 2014; Koerner et al. 2015). Our findings suggest that maintaining love as a foundation and primary organizing principle in life may enhance well-being through multiple pathways.

Even in diverse and secular contexts, the relationship between love and spirituality appears robust. Contemporary secular practices such as mindful awareness, often characterized as inherently ethical and caring (i.e., see heartfulness; Maurits Kwee 2015; Voci et al. 2019), may facilitate experiences of love and spiritual connection. Mindful self-compassion practices, though secular in nature, have also demonstrated increases in loving-kindness and both self- and other-focused compassion (Boellinghaus et al. 2014; Fulton 2018). These mindfulness practices may represent important mechanisms through which love experiences develop and persist. Likewise, greater experiences of love have been elicited by the eight-week Awakened Awareness program, designed to foster a direct relationship with the God, the Higher Power or the Universe at large (Scalora et al. 2022). People who have had mystical experiences also routinely describe a palpable surge in subjective feelings of God, presence, of love and spirituality (Woollacott and Shumway-Cook 2020).

4.1. Clinical Implications

Our findings have several important implications for clinical practice. First, they suggest that assessment of love experiences, particularly religious or spiritual in kind, may provide valuable prognostic information in therapeutic settings. Clinicians might benefit from incorporating questions about patients’ experiences of love and their spiritual understanding of love into initial assessments. The strong association between religious love and positive mental health outcomes suggests potential therapeutic benefits from exploring and fostering positive spiritual coping mechanisms (Abu-Raiya and Pargament 2015; Ai and Hall 2011). Second, the relationship between love profiles and core beliefs warrants attention in therapeutic contexts. Using instruments such as the negative core beliefs inventory (Osmo et al. 2018), clinicians might examine how unlovability beliefs relate to spiritual experiences and overall well-being. The connection between love experiences and an expanded sense of identity—often described as interconnectedness or continuity of the “self–other” (Aron et al. 1991, 1992; Aron and Fraley 1999)—may offer therapeutic opportunities for fostering resilience and well-being. In addition, previous research shows that people who experience love and religious love tend to rely more on positive spiritual coping when handling challenges and life stressors (Abu-Raiya and Pargament 2015; Ai and Hall 2011), while spirituality is often used for coping with challenges and adversities (Ano and Vasconcelles 2005; Bjorck and Thurman 2007). Third, our findings suggest the importance of considering attachment patterns in both interpersonal and transpersonal domains. While the relationship between attachment and romantic love has been extensively studied (Hazan and Shaver 2017), the connection between transpersonal love experiences and attachment styles represents an important area for future clinical research. Little, if any, research to date has examined the explicit link between transpersonal endorsement of love and interpersonal attachment styles.

4.2. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

A few limitations warrant consideration. First, the cross-sectional nature of our study precludes causal inferences about the relationship between love profiles and well-being outcomes. For instance, directionality cannot be inferred between level of love and level of well-being, depression, and anxiety. Longitudinal research, particularly employing latent transition or latent growth analysis (Lanza et al. 2003) might clarify how these profiles develop and change over time. Second, our study relies on self-report data, which may introduce reporting biases, such as the halo effect, underreporting bias, and inattention (Chan 2009; van de Mortel 2020). Future research might also consider incorporating multiple assessment methods, including behavioral measures and physiological markers of love experiences, for example. Third, we acknowledge that empirical data collected through MTurk samples have been both embraced for sample diversity but criticized for potential concerns over participant attention, data validity, and representativeness (Chandler and Shapiro 2016; Hauser et al. 2019; Hauser and Schwarz 2016). Our U.S.-based sample also limits generalizability to other cultural or national contexts. In that love manifests both universal and culturally specific aspects (Jankowiak and Fischer 1992; Kim and Hatfield 2004; Shaver et al. 1996), cross-cultural investigations of love profiles merit further investigation: participants from other religious, national, cultural backgrounds would be crucial in future research. Notwithstanding these limitations, this is the first study to our knowledge that identifies love of the Higher Power as correlated with the broad gradations of love for humanity, and presents evidence supporting the foundational nature of love of God and humanity to mental health and well-being.

5. Conclusions

Pending replication in other cultural contexts and with behavior-oriented measurements, this investigation suggests that the experience of love, particularly of feeling loved by God or a Higher Power holds strong associations with spiritual life, well-being, and lower depression and anxiety. The relationship between love profiles and psychological outcomes appears non-linear, suggesting that love may function as a paradigmatic orientation, or as a choice in a way of being, rather than a more typical continuous, linear dimension. Our findings highlight the central role of religious love in profile differentiation and underscore the importance of considering spiritual dimensions in understanding the psychology of love to fellow human beings. These results call for increased attention to the foundation of love of a Higher Power, God, the Universe at large, and the extension of this relationship to love for humanity across the range of ways in which we might love fellow human beings. The primary choice to love God and, by extension, to love humanity appears to carry a profound categorical difference in how one’s experiences in life unfold, seen here specifically in relationship to broader spiritual life, well-being and mental health outcomes. The experience of love in relation to God or a Higher Power appears foundational to the various ways in which we experience love toward humanity and well-being in general.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.C.D.S.M. and L.M.; methodology, F.C.D.S.M.; formal analysis, F.C.D.S.M.; investigation, F.C.D.S.M. and L.M.; resources, L.M.; data curation, F.C.D.S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, F.C.D.S.M.; writing—review and editing, F.C.D.S.M. and L.M.; visualization, F.C.D.S.M.; supervision, L.M.; project administration, L.M.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Teachers College, Columbia University (Protocol code 23-177, 23 January 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset generated and analyzed during the current study is not publicly available. However, the data supporting the findings of this study may be made available from the corresponding author upon a reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the insights, support, and acknowledgment of colleagues and doctoral fellows at the Spirituality Mind–Body Institute, at Teachers College, Columbia University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abu-Raiya, Hisham, and Kenneth I. Pargament. 2015. Religious Coping among Diverse Religions: Commonalities and Divergences. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 7: 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Amy L., and Daniel E. Hall. 2011. Divine Love and Deep Connections: A Long-Term Followup of Patients Surviving Cardiac Surgery. Journal of Aging Research 2011: e841061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ano, Gene G., and Erin B. Vasconcelles. 2005. Religious Coping and Psychological Adjustment to Stress: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology 61: 461–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron, Arthur, and Barbara Fraley. 1999. Relationship Closeness as Including Other in the Self: Cognitive Underpinnings and Measures. Social Cognition 17: 140–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron, Arthur, and Lori Westbay. 1996. Dimensions of the Prototype of Love. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 70: 535–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron, Arthur, Elaine N. Aron, and Danny Smollan. 1992. Inclusion of Other in the Self Scale and the Structure of Interpersonal Closeness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 63: 596–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron, Arthur, Elaine N. Aron, Michael Tudor, and Greg Nelson. 1991. Close Relationships as Including Other in the Self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 60: 241–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroll, Bruce, Felicity Goodyear-Smith, Susan Crengle, Jane Gunn, Ngaire Kerse, Tana Fishman, Karen Falloon, and Simon Hatcher. 2010. Validation of PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 to Screen for Major Depression in the Primary Care Population. The Annals of Family Medicine 8: 348–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, Richard. 2006. God as a Secure Base: Attachment to God and Theological Exploration. Journal of Psychology and Theology 34: 125–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berscheid, Ellen, and Elaine Walster. 1974. A Little Bit about Love. Foundations of Interpersonal Attraction 1: 356–81. [Google Scholar]

- Bjorck, Jeffrey P., and John W. Thurman. 2007. Negative Life Events, Patterns of Positive and Negative Religious Coping, and Psychological Functioning. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 46: 159–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boellinghaus, Inga, Fergal W. Jones, and Jane Hutton. 2014. The Role of Mindfulness and Loving-Kindness Meditation in Cultivating Self-Compassion and Other-Focused Concern in Health Care Professionals. Mindfulness 5: 129–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozdogan, Hamparsum. 1987. Model Selection and Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC): The General Theory and Its Analytical Extensions. Psychometrika 52: 345–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byerly, T. Ryan. 2023. Agnostics Who Accept God’s Supposed Love Experience Greater Well-Being. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 26: 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, David. 2009. So Why Ask Me? Are Self-Report Data Really That Bad. In Statistical and Methodological Myths and Urban Legends: Doctrine, Verity and Fable in the Organizational and Social Sciences. London: Routledge, pp. 309–36. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, Jesse, and Danielle Shapiro. 2016. Conducting Clinical Research Using Crowdsourced Convenience Samples. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 12: 53–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantini, Luigi, Cesira Pasquarella, Anna Odone, Maria Eugenia Colucci, Alessandra Costanza, Gianluca Serafini, Andrea Aguglia, Martino Belvederi Murri, Vlasios Brakoulias, and Mario Amore. 2021. Screening for Depression in Primary Care with Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9): A Systematic Review. Journal of Affective Disorders 279: 473–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, Colleen. 2005. The Spirituality Scale: Development and Psychometric Testing of a Holistic Instrument to Assess the Human Spiritual Dimension. Journal of Holistic Nursing 23: 145–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza Marcovski, Fabio Cezar, and Lisa J. Miller. 2022. A Latent Profile Analysis of the Five Facets of Mindfulness in a US Adult Sample: Spiritual and Psychological Differences among Four Profiles. Current Psychology 42: 14223–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, Ed, Robert A. Emmons, Randy J. Larsen, and Sharon Griffin. 1985. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment 49: 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dozois, David J. A., Peter J. Bieling, Lyndsay E. Evraire, Irene Patelis-Siotis, Lori Hoar, Susan Chudzik, Katie McCabe, and Henny A. Westra. 2014. Changes in Core Beliefs (Early Maladaptive Schemas) and Self-Representation in Cognitive Therapy and Pharmacotherapy for Depression. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy 7: 217–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, Robert A., Michael E. McCullough, and Jo-Ann Tsang. 2003. The Assessment of Gratitude. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Esch, Tobias, and George B. Stefano. 2005. Love Promotes Health. Neuroendocrinology Letters 26: 264–67. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fehr, Beverley. 1988. Prototype Analysis of the Concepts of Love and Commitment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 55: 557–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulton, Cheryl L. 2018. Self-Compassion as a Mediator of Mindfulness and Compassion for Others. Counseling and Values 63: 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galante, Julieta, Marie-Jet Bekkers, Clive Mitchell, and John Gallacher. 2016. Loving-Kindness Meditation Effects on Well-Being and Altruism: A Mixed-Methods Online RCT. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being 8: 322–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, James M. 2011. Measuring Love in Romantic Relationships: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 28: 748–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, David, Gabriele Paolacci, and Jesse Chandler. 2019. Common Concerns with MTurk as a Participant Pool: Evidence and Solutions. In Handbook of Research Methods in Consumer Psychology. London: Routledge, pp. 319–37. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser, David J., and Norbert Schwarz. 2016. Attentive Turkers: MTurk Participants Perform Better on Online Attention Checks than Do Subject Pool Participants. Behavior Research Methods 48: 400–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazan, Cindy, and Phillip Shaver. 2017. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. In Interpersonal Development. London: Routledge, pp. 283–296. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrick, Clyde, and Susan Hendrick. 1986. A Theory and Method of Love. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 50: 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowiak, William R., and Edward F. Fischer. 1992. A Cross-Cultural Perspective on Romantic Love. Ethnology 31: 149–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Jungsik, and Elaine Hatfield. 2004. Love Types and Subjective Well-Being: A Cross-Cultural Study. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal 32: 173–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koerner, Naomi, Kathleen Tallon, and Andrea Kusec. 2015. Maladaptive Core Beliefs and Their Relation to Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy 44: 441–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, Neal. 2003. Religious Meaning and Subjective Well-Being in Late Life. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 58: S160–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, Kurt, Robert L. Spitzer, and Janet B. W. Williams. 2001. The PHQ-9: Validity of a Brief Depression Severity Measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine 16: 606–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza, Stephanie T., Brian P. Flaherty, and Linda M. Collins. 2003. Latent Class and Latent Transition Analysis. In Handbook of Psychology. Hoboken: Wiley, pp. 663–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, John Alan. 1977. A Typology of Styles of Loving. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 3: 173–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leman, Joseph, Will Hunter, Thomas Fergus, and Wade Rowatt. 2018. Secure Attachment to God Uniquely Linked to Psychological Health in a National, Random Sample of American Adults. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 28: 162–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, Jeff. 2000. A Prolegomenon to an Epidemiology of Love: Theory, Measurement, and Health Outcomes. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 19: 117–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, Jeff. 2001. God, Love, and Health: Findings from a Clinical Study. Review of Religious Research 42: 277–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, Jeff. 2023. The Epidemiology of Love: Historical Perspectives and Implications for Population-Health Research. The Journal of Positive Psychology 18: 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, Jeff, and Berton H. Kaplan. 2010. The Sorokin Multidimensional Inventory of Love Experience (SMILE): Development, Validation, and Religious Determinants. Review of Religious Research 51: 380–401. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis Hall, M. Elizabeth, and Peter Hill. 2019. Meaning-Making, Suffering, and Religion: A Worldview Conception. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 22: 467–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotrakul, Manote, Sutida Sumrithe, and Ratana Saipanish. 2008. Reliability and Validity of the Thai Version of the PHQ-9. BMC Psychiatry 8: 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurits Kwee, G. T. 2015. Pristine Mindfulness: Heartfulness and Beyond. In Buddhist Foundations of Mindfulness. Mindfulness in Behavioral Health. Edited by Edo Shonin, William Van Gordon and Nirbhay N. Singh. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 339–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClintock, Clayton H., Elsa Lau, and Lisa Miller. 2016. Phenotypic Dimensions of Spirituality: Implications for Mental Health in China, India, and the United States. Frontiers in Psychology 7: 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, Michael E., Robert A. Emmons, and Jo-Ann Tsang. 2002. The Grateful Disposition: A Conceptual and Empirical Topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 82: 112–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, Lisa, Ravi Bansal, Priya Wickramaratne, Xuejun Hao, Craig E. Tenke, Myrna M. Weissman, and Bradley S. Peterson. 2014. Neuroanatomical Correlates of Religiosity and Spirituality: A Study in Adults at High and Low Familial Risk for Depression. JAMA Psychiatry 71: 128–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmo, Flávio, Victor Duran, Amy Wenzel, Irismar Reis de Oliveira, Sara Nepomuceno, Maryana Madeira, and Igor Menezes. 2018. The Negative Core Beliefs Inventory: Development and Psychometric Properties. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy 32: 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastor, Dena A., Kenneth E. Barron, B. J. Miller, and Susan L. Davis. 2007. A Latent Profile Analysis of College Students’ Achievement Goal Orientation. Contemporary Educational Psychology 32: 8–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, Wendy J. 2021. Self-Compassion Mindsets: The Components of the Self-Compassion Scale Operate as a Balanced System within Individuals. Current Psychology 40: 5040–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, Stephen G. 2007. Altruism and Health: Perspectives from Empirical Research. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2009-07757-000 (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Poulin, Michael J., and E. Alison Holman. 2013. Helping Hands, Healthy Body? Oxytocin Receptor Gene and Prosocial Behavior Interact to Buffer the Association between Stress and Physical Health. Hormones and Behavior 63: 510–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, Joshua M., Patrick N. Beymer, Daniel J. Anderson, C. J. Van Lissa, and Jennifer A. Schmidt. 2019. TidyLPA: An R Package to Easily Carry out Latent Profile Analysis (LPA) Using Open-Source or Commercial Software. Journal of Open Source Software 3: 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, Zick. 1970. Measurement of Romantic Love. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 16: 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, Richard M., and Christina Frederick. 1997. On Energy, Personality, and Health: Subjective Vitality as a Dynamic Reflection of Well-Being. Journal of Personality 65: 529–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scalora, Suza C., Micheline R. Anderson, Abigail Crete, Elisabeth J. Mistur, Amy Chapman, and Lisa Miller. 2022. A Campus-Based Spiritual-Mind-Body Prevention Intervention against Symptoms of Depression and Trauma; An Open Trial of Awakened Awareness. Mental Health & Prevention 25: 200229. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, Gideon. 1978. Estimating the Dimension of a Model. The Annals of Statistics 6: 461–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaver, Phillip, Judith Schwartz, Donald Kirson, and Cary O’connor. 1987. Emotion Knowledge: Further Exploration of a Prototype Approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 52: 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaver, Phillip R., Hillary J. Morgan, and Shelley Wu. 1996. Is Love a ‘Basic’ Emotion? Personal Relationships 3: 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, Pitirim A. 1954. Forms and Techniques of Altruistic and Spiritual Growth: A Symposium. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sorokin, Pitirim A. 2015. Ways & Power of Love: Techniques of Moral Transformation. Conshohocken: Templeton Foundation Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer, Robert L., Kurt Kroenke, Janet BW Williams, and Bernd Löwe. 2006. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine 166: 1092–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, Robert J. 1986. A Triangular Theory of Love. Psychological Review 93: 119–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, Robert J., and Susan Grajek. 1984. The Nature of Love. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 47: 312–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroope, Samuel, Scott Draper, and Andrew L. Whitehead. 2013. Images of a Loving God and Sense of Meaning in Life. Social Indicators Research 111: 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traupmann, Jane, and Elaine Hatfield. 1981. Love and Its Effect on Mental and Physical Health. Aging: Stability and Change in the Family 12: 253–74. [Google Scholar]

- van de Mortel, Thea F. 2020. Faking It: Social Desirability Response Bias in Self-Report Research. The Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing 25: 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Voci, Alberto, Chiara A. Veneziani, and Giulia Fuochi. 2019. Relating Mindfulness, Heartfulness, and Psychological Well-Being: The Role of Self-Compassion and Gratitude. Mindfulness 10: 339–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, David, Lee Anna Clark, and Auke Tellegen. 1988. Development and Validation of Brief Measures of Positive and Negative Affect: The PANAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 54: 1063–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woollacott, Marjorie, and Anne Shumway-Cook. 2020. The Mystical Experience and Its Neural Correlates. Journal of Near-Death Studies 38: 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimet, Gregory D., Nancy W. Dahlem, Sara G. Zimet, and Gordon K. Farley. 1988. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Journal of Personality Assessment 52: 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimet, Gregory D., Suzanne S. Powell, Gordon K. Farley, Sidney Werkman, and Karen A. Berkoff. 1990. Psychometric Characteristics of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Journal of Personality Assessment 55: 610–17. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).