Abstract

Ludwig Wittgenstein kept a box file titled “Nonsense Collection” that is now archived in the Research Institute Brenner-Archiv. Several items in this collection concern both science and religion (or spiritualism). Although Wittgenstein may have thought of them as jokes, these items do reflect his thoughts on the relationship between science and religion. In this paper, three items from the Nonsense Collection that touch both science and religion are presented. It will discuss first why these items are nonsensical by applying interpretation of the concept of nonsense given by McGuinness. Then it will take up different ideas of Wittgensteinian philosophy of religion proposed by Pichler, Schönbaumsfeld, Somavilla, and Sunday Grève; it shows that the items presented in this paper would also be nonsensical, according to this kind of philosophy of religion. It concludes with historical and modern cases that also show dysfunctional relationships between science and religion and that these cases may have found their way into the Nonsense Collection.

1. Introduction

Ludwig Wittgenstein, during his lifetime, had a box file containing mainly newspaper cuttings. The box file was titled “Nonsense”, and in it we find items that Wittgenstein thought nonsensical. In several letters, Wittgenstein refers to this box file as a “collection of nonsense” or “nonsense collection” (NC). Today, we still have the contents of NC: Wittgenstein passed this box to Rush Rhees soon before his death, and Rhees passed it in turn to Brian McGuinness. McGuinness then gave it to the Research Institute Brenner-Archiv.1 Thus, at the time of writing, NC is part of the collection kept in Brenner-Archiv and open for visiting researchers.2 Most of the items are cuttings from newspapers or magazines, but we can also find personal letters, academic articles, booklets and even a whole volume of “Der Stürmer”, a Nazi propaganda magazine, there. The dating of the items ranges from the 1920s to 1947.

Several features of NC must be noted here. First, Wittgenstein did not collect all the items in NC, but several people (e.g., Wittgenstein’s brother Paul and Hermine Wittgenstein, but also his friends, like W.H. Watson) sent them to him. Wittgenstein’s correspondence documents that different people contributed to items in NC.3 Second, Wittgenstein did not “accept” just any item for NC. Instead, the nonsense had to fulfill some standards, as the letter to Piero Sraffa cited below shows. And third, Wittgenstein probably ridiculed these items; in fact, letters document that he even shared these items with his friends! It is doubtful that Wittgenstein had a stringent idea on we can doubt that.

Items in NC touch a large variety of subjects, just as we can find nonsense in many contexts. One can find items about music (including musicians and composers), as well as literature. Astonishingly, there are many items concerning religion and science in a broader sense. Of the 127 items in NC, below is a list of items that concern “religion” in a broad sense, as well as those items concerning science or scientists.4 Those items in the list marked with an R are items that have religious or spiritual contents in them; those marked with an S touch the broader subject of science and scientists. If the title is not in English, the translation is given in brackets. A short description is given in footnotes for items concerning both religion and science that are not described further in the paper.

| No. | Title | ||

| 4 | Florizel v. Reuter: “Zwei mysteriöse Erlebnisse” [Two mysterious experiences] | R | |

| 6 | Viktor Claudius: “Spiritismus—ja oder nein?” [Spiritualism—yes or no?] | R | |

| 10 | Bishop E. A. Knox: “The Unspeakable Glory of Eternity” Items 10–28 consist of articles in the series “Where are the deads?”, see below. | R | |

| 11 | Arnold Bennett: “Where are the Dead?” | R | |

| 12 | Julian S. Huxley: “My Idea of Survival” | R | S |

| 13 | Henry Townsend: “The Meaning of Heaven” | R | |

| 14 | G. B. Shaw: “Shaw Butts In” | R | |

| 15 | Sir Arthur Keith: “Where are the Dead?” | R | S |

| 16 | Rev. R. J. Campbell: “The Dead Are Alive” | R | |

| 17 | Oliver Lodge: “The Discovery of the Spiritual World” | R | S |

| 18 | H. R. L. Sheppard, G. K. Chesterton: “In the Hands of Love” | R | |

| 19 | Hilaire Belloc: “Immortality” | R | |

| 20 | Hugh Walpole, G. B. Shaw, H. Belloc: “The Little Minds of Men” | R | |

| 21 | H. J. Spooner: “My Evidence for Survival” | R | S |

| 22 | Sir Arthur Conan Doyle: “The Answer of the Spiritualist” | R | |

| 23 | Lord Gorell: “The Ante-Rooms of Eternity” | R | |

| 24 | J. A. Spender: “The Eternal Vision” | R | |

| 25 | Lloyd George: “The Simple Faith” | R | |

| 26 | Robert Blatchford: “The Secrets of Life and Love” | R | |

| 27 | T. R. Glover, G. B. Shaw: “The Lesson of Life” | R | |

| 28 | E. S. Waterhouse: “What Is Eternal if Not the Soul?” | R | |

| 29 | “Die Hasenclever(ische Erklär)ung vor Gericht” [The Hasencleverness/explanation by Hasenclever before the court] | R | |

| 31 | Paul Sünner: “Spontaneous Phenomena through Frau Silbert” | R | |

| 34 | Ludwig Hänsel: “Katholische Bildung” [Catholic education] | R | |

| 35 | Several pages from Hamburger Illustrierte, No. 40. This item contains a report on a statue of Einstein—along with other statues modeled after Buddha, the Prophet Muhammad and Immanuel Kant—decorating the entrance of a newly funded church in New York, today’s Riverside Church in New York. | R | S |

| 37 | Picture of Albert Einstein with Jacques Feyder and Ramon Navarro | S | |

| 39 | H. W. B. Joseph, Lord Olivier: “The Universe” | S | |

| 40 | Picture of Albert Einstein with a woman in a film studio | S | |

| 41 | J. B. Haldane, G. M. Spooner: “Habit and the evolutionary process. Professor Haldane replies” | S | |

| 44 | J. B. S. Haldane: “The Gold Makers” | S | |

| 45 | “Erholung von der Politik” [Resting from the politics] | S | |

| 47 | E. W. Macbride, J. W. Heslop Harrison: “The evolutionary process. Lamarkism and its opponents. Prof. Macbride replies” | S | |

| 49 | “Pio XI inaugura “in nomine Deo” la stazione radio del Vaticano” [Pope Pius XI inaugurates the Vatican radio station in the name of God] | R | |

| 50 | “Convocation of Canterbury. Bishop on wrong ideas of God” This item reports on Bishop Haldane’s idea that science will be an aid for religion. | R | S |

| 51 | Picture of Pope Pius XI | R | S |

| 52 | “Broadcast by the Pope” This and the previous item concern the inauguration of the Vatican radio by Pope Pius XI. | R | S |

| 53 | Herbert Barker: “The religion of a plainman” This item is the reflection of Sir Herbert Barker, a surgeon, after having read Sir James Jeans’s Mysterious Universe. | R | S |

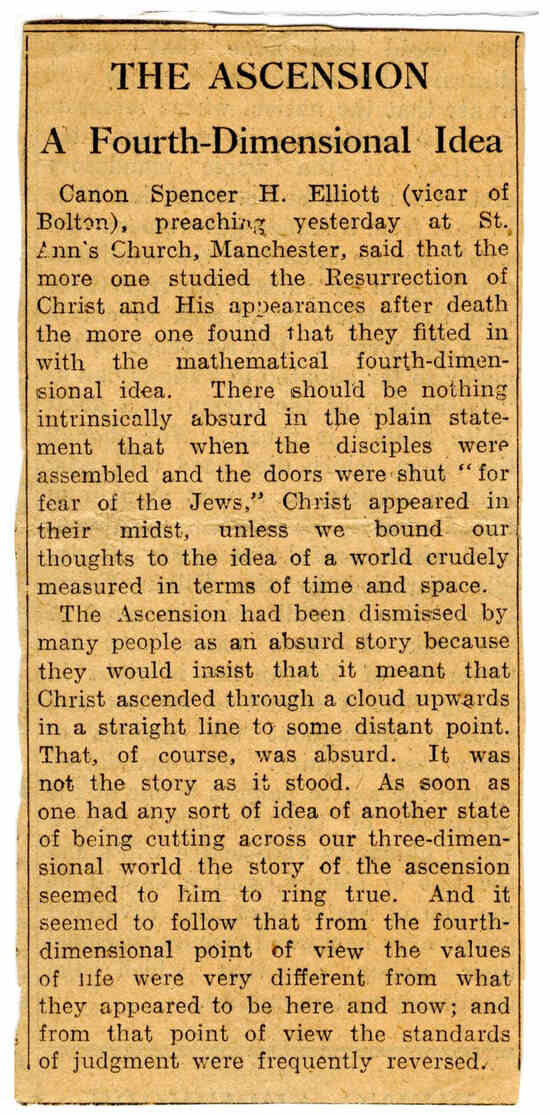

| 54 | “The Ascension. A Fourth-Dimensional Idea” | R | S |

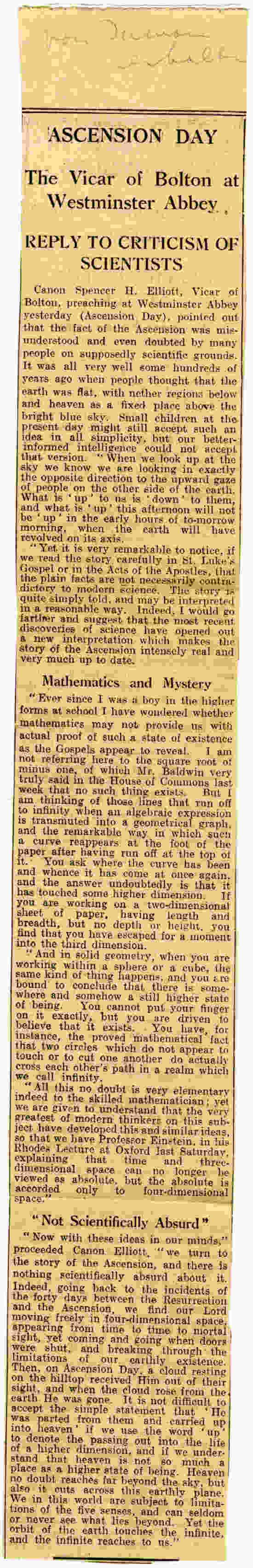

| 55 | “Ascension Day. The Vicar of Bolton at Westminster Abbey. Reply to criticism of scientist” Items 54 and 55 are reports of sermons, see below. | R | S |

| 56 | “Supernatural light” This is a report in which Sir Ambrose Fleming is said to reason upon the possibility of a “pillar of fire” that is reported in the Bible. | R | S |

| 58 | J. W. S, E. L: “A Talk about Philosophy” | R | |

| 59 | “Girl phenomenon of psychic world” | R | |

| 60 | “Radio to the earth from other worlds” | S | |

| 62 | Collins Owen: “Is the universe merely an ash-heap?” This item reports an event where “scientists, philosophers and theologians discuss the origin of mind and matter”. | R | S |

| 63 | “Time everlasting. Sir Jeans and A Mathematical Universe” | S | |

| 64 | “Lodge believes mind of Edison to direct work. Will continue to influence on earth from beyond” | R | S |

| 65 | A postcard advertisement | R | |

| 66 | Eugen Bleuler: “Meine okkulten Erlebnisse” [My occult experiences] | R | |

| 67 | Rene Thevenin: “A race of supermen who perished 20.000 years ago?” | S | |

| 68 | “Einstein is wrong, Callahan claims” This is an article reporting rev. J. J. Callahan’s plan to prove Einstein’s Theory of Relativity wrong. | R | S |

| 70 | “Scientists Four to One for Belief in God” | R | S |

| 71 | “Grounds of faith” | R | |

| 76 | Arthur Eddington: “The expanding Universe” | S | |

| 77 | Bishop E. W. Barnes: “The University Sermon” This item is a sermon in which Bishop E. W. Barnes defends religious belief against scientific knowledge. | R | S |

| 78 | J. S. Jeans: “The universe” | S | |

| 79 | Florizel v. Reuter: “Wie ich mit Paganinis Geist in Verbindung gelangte” [How I got in touch with the soul of Paganini] | R | |

| 81 | Picture of Das Magier-Experiment | R | |

| 83 | “The Atom Bombardiers” | S | |

| 84 | “Baldwin presents fifteen portraits to new building” | S | |

| 87 | “New conception of God foreseen. Discoveries of Einstein may bring about change” | R | S |

| 89 | “Trippers to Other Planets” | S | |

| 92 | Pages 5 and 6 from “Unser Pfarrblatt” No. 22 | R | |

| 93 | E. W. MacBride, A. Meek, D. F. Ritchie: “Habit and the evolutionary process. Prof. Haldane and his theory. Reply from Prof. MacBride” | S | |

| 94 | “Adventures of Ideas by Alfred North Whitehaed” | S | |

| 97 | J. W. N. Sullivan, W. Grieson: “An Outline of Modern Belief” | S | |

| 98 | A letter by Gilbert T. Sadler possibly to Wittgenstein | S | |

| 100 | “Die ‚Schwarze Magie’ und ihre Gegner” [The ‘black magic’ and its opponents] | R | |

| 102 | E. Dale: “Planets and the ascent of man. Headmaster analogy” This item is an open letter by Rev. E. Dale in which he claims that the names of the nine planets correspond with the development from chaos to truth and therefore the “upward progress of man”. | R | S |

| 106 | Pages 5 and 6 from “Unser Pfarrblatt”, No. 18 | R | |

| 109 | Dust wrapper of G. H. Hardy’s A Mathematician’s Apology | S | |

| 110 | Advertisement of Cambridge University Press | S | |

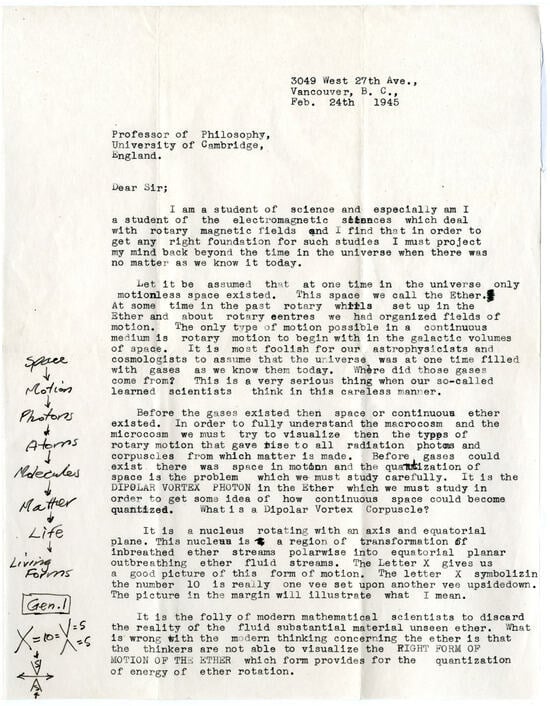

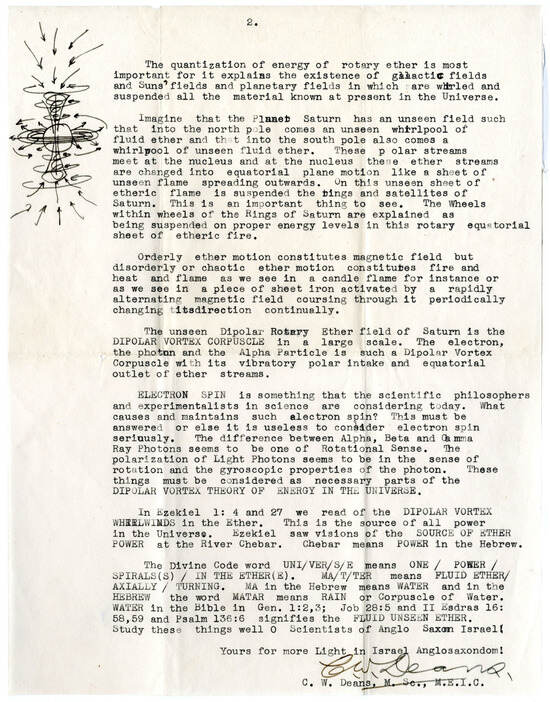

| 115 | A letter by C. W. Deans In the letter Deans explains his idea on physics, see below. | S | |

| 123 | [Without title, on Einstein] | S | |

| 125 | “Girl amazes Einstein. ‘Things no one could know’” | R | S |

| 126 | Picture of Miss Gene Dennis | R | S |

Among the items concerning religion, we can find a series of commentaries (items 10–28) called “Where are the dead?”5 published in the “Daily News and Westminster Gazette” in 1928. Here, not only physicians and theologians, but also other intellectuals (e.g., Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Sean Bernard Shaw, and Hillaire Belloc), stated their opinions on the whereabouts of dead people. We can regard item 45 as a typical item concerning science, showing a picture of Ramsey MacDonald in conversation with Max Planck and Albert Einstein. Item 35, too, with a report on a church having Einstein as a stylite at its entrance, can be certainly regarded as a good representation of an item that concerns both religion and science.

While some items deal with spiritualism (in the sense of psychics), Wittgenstein did not include an item just because it had a connection with spiritualism. Wittgenstein refused to include an article on Joseph Rhine Banks, a rather famous psychic at that time. He writes to Piero Sraffa in 1950:

Thank you for the Listener. Rhine is one of those people who would make me feel sceptical about the law of gravitation if he told me about it. He isn’t quite concentrated enough, however, to be very amusing. If you meet him, please tell him that, if he wants to get into my collection of nonsense, he’ll have to compress his rubbish a little more.6

It is therefore even more remarkable that Gene Dennis, a lesser-known psychic, is represented in multiple items, namely in items No. 59, 125 and 126. We can only speculate why Miss Dennis has the questionable honor to be present in NC. The most convincing argument7 that I have encountered is because of Einstein. To Wittgenstein, Dennis is particularly nonsensical because there are reports that even Einstein was amazed about her (NC item 126).

Of the 127 items that are in NC, we can find no less than 52 items that deal with religion or spiritualism, and there are 44 items concerning science or scientists in a broader sense. The interesting part of this overview is that there are 21 items that touch both religion and science; in other words, more than ⅓ of the religious items also have scientific content.8

In this paper, I want to focus on items that concern the relationship between science and religion. As NC is a collection of nonsensical items, we can assume that the relationship between science and religion that is expressed in some of these items should be—at least according to Wittgenstein—avoided. I will therefore present three items in NC that concern both science and religion and discuss why they might be nonsensical. First, I will follow Brian McGuinness and his interpretation of “nonsense” and offer a first explanation of why these items could be nonsensical. Then, I will take up concepts of “Wittgensteinian” philosophy of religion that are described by Alois Pichler, Genia Schönbaumsfeld, Ilse Somavilla, and Sebastian Sunday Grève, and examine how these concepts can shed light onto these items in NC. While McGuinness gives a rough idea why the concept of nonsense applies to these items, philosophy of religion can show why the relationship between science and religion expressed in these items is rejected by Wittgenstein. I will conclude with a historical and a modern case that I think Wittgenstein would have put into NC.

2. Three Items, Two Incidents: Mixing Science and Religion in NC

2.1. C.W. Deans’ Letter to Ludwig Wittgenstein

The first item in NC described here is item No. 115. Transcription and facsimiles of this item can be found in Appendix A.1. It is a letter by C.W. Deans to a professor in philosophy in Cambridge. In this letter, Deans introduces himself as a student of physics and depicts his alternative theory on the beginning of the universe by referring to concepts of ether and rotational motion. At the end of the letter, Deans refers to the Book of Ezekiel and explains how the words ‘universe’ and ‘matter’ consist of words of deeper meaning and requests that his reader study his theory.

Some information should be added to this letter. The envelope of this letter was not kept in NC and is presumably lost. Dating information and metadata of the correspondence are therefore extracted from texts in the letter alone. The address line of the letter suggests that the letter is dated to 24 February 1945 and sent from Vancouver, Canada, to Cambridge, England. It is assumed from the greeting line that the letter is sent to a professor of philosophy at the University of Cambridge. McGuinness speculated that Wittgenstein is probably not the official recipient of this letter and that it could have been a colleague of Wittgenstein who gave him this letter as a contribution to NC.

While we do not have much information on C.W. Deans, the letter itself gives us some clues on what Deans believed. By calling his reader “Scientists of Anglo Saxon Israel” and ending his letter by wishing more light for “Israel Anglosaxondom”, the author has outed himself as a follower of British Israelism, a group of Christian believers who thought that Anglo-Saxons are descendants of Israel. This religious movement gained momentum in the second half of the 19th Century and had followers that were famous in GB and USA. (Cf. e.g., Wilson 1968; Moshenska 2008).

Claims about physics in this letter are—one might say—puzzling, even when we keep in mind that the letter was written in the year of 1945. Without doubt, sciences—especially physics—have advanced greatly since the 19th Century. Since the author of the letter claims that he is “a student of the electromagnetic sciences which deal with rotary magnetic fields”, we can assume that Deans, as a student of physics, had access to newer findings in his scientific discipline. In fact, Deans refers specifically to electron spin, which was discovered in 1925 (Uhlenbeck and Goudsmit 1926); he also shows insights into other fields of physics like cosmology and astronomy. However, Deans seems to interpret findings of other physicists differently. Specifically, he does not agree with some theories that are already common at his time, as he stated in the letter: “It is most foolish for our astrophysicists and cosmologists to assume that the universe was at one time filled with gases as we know them today. Where did those gases come from?”.

The most intriguing parts are the speculations that Deans has included in his letter. He speculates not only about the role of vortices for equilibrium of motion, but also on how Bible verses have reported on them. In the Book Ezekiel, a prophet reported on a vision, and Deans quickly identifies the vision as one that is about “dipolar vortex whirlwinds” and speculates that the vision of the prophet is really about his envisioned theory of vortex. At the end of the letter, we can also say that the way that Deans relates syllables and letters of a word to a deeper meaning of the words is also highly speculative and questionable.

2.2. Ascension of Christ, Mathematics and Physics: Two Reports

Let us look at two reports (kept as items No. 54 and No. 55) on sermons by Spencer H. Elliott that are kept in NC. Transcriptions and facsimiles of these items are available in Appendix A.2 (No. 54) and Appendix A.3 (No. 55). Elliott is vicar of St. Peter’s Church, Bolton9 between 1930 and 1933, and both of his sermons are given on the occasion of the Ascension Day. Item No. 54 tells the readers that a sermon was given in St. Ann’s Church in Manchester, and according to item No. 55, Elliott gives the sermon in Westminster Abbey in London. Due to the similar content in both sermons, it seems obvious that Elliott has given the same sermon in two places; however, this remains speculative as we do not even have any evidence that these sermons even take place in the same year.

Both articles report that Elliott has given an account on how the Ascension of Christ may be justified in the light of modern science advances. Elliott admits that a scientist who knows physics well would reject the idea that “Christ ascended through a cloud upwards” (NC item 54). However, if Christ was a being of a higher dimension, then what seems to be an impossible movement would actually be very easy to understand. Elliott concludes, therefore, that it is not absurd to believe in the Ascension of Christ and that this story in the Gospels “may be interpreted in a reasonable way” (NC item 55) such that it does not contradict modern science. In fact, he would go further and even claim that modern science has “opened out a new interpretation which makes the story of the Ascension intensely real” (NC item 55).

According to the reports, Elliott’s main interest is the defense of Christ’s ascension against the allegation of absurdity, as a subheading of item 55 and many places in both reports suggest. He speculates that, with the help of mathematics, more specifically with the help of fourth-dimensional geometry, Christ’s ascension can be conceptualized as a movement of a being in the fourth dimension seen through the eyes of three-dimensional human beings. He takes the analogy of the relationship between a two-dimensional and a three-dimensional being: a two-dimensional being may see two spheres as two circles and is surprised that, while these two circles do not touch each other in the second dimension, they can still intersect in the third dimension. Similarly, Christ’s movement may be a simple one in the fourth dimension, while for people in the third dimension, this movement may seem to be an ascension into heaven.

Elliott even makes references to a so-called Rhodes Lecture given by Einstein on mathematical constructs (cf. NC Item No. 55 and Fox 2018, p. 297). In the report, Elliott emphasizes that Einstein has introduced the concept of the four-dimensional space that is superior to the old three-dimensional one. Elliott concludes that the Ascension of Christ may fit well into these new ideas coming from the sciences.

At the time of writing, we have not yet found out where these newspaper cuttings came from. We can, however, date the sermons around the year 1931. Item 55 must be reporting on a sermon that takes place on 14 May 1931. We conclude from the events that are being reported in the article—Einstein has given a lecture in Oxford on a Saturday, and the following Thursday is the Ascension Day of that year10—that the date of the sermon by Elliott must be the 14 May 1931. Due to the brevity of the article in Item 54, the sermon is more difficult to date. Still, from the vast similarity between two sermons and from the fact that Elliott is (still) reported as being vicar in Bolton, we can conclude that Elliott probably used the same idea for two sermons, and this makes 1931 very likely to be the year when Elliott preached in Manchester.

Two remarks on the reports should also be added here. Firstly, it is worth noting that Wittgenstein has made a remark on top of item 55 that reads: “Von Inman erhalten” (“received from Inman”). This shows that John Inman is among those friends who contributed to NC. Furthermore, we can learn much from the differences between both articles. We can immediately notice that the second article is longer and has more literal rendition of the sermon than the first one. However, the subtle difference in focus really separates these reports from another: item 55 has more information on the argument against the allegation of absurdity, and the reporter emphasizes that the Ascension of Christ does not contradict scientific knowledge, while item 54 seems to be more focused on the possible shift of values that follow from the idea of Christ as a being of higher dimension.

2.3. Nonsenses in These Items That Are Not Nonsensical Enough

Let us first discuss three smaller ideas on why these items were collected in NC. However, none of these ideas are very convincing.

The first idea is that Deans’ letter is preserved in NC because of its reference to the religious movement British Israelism. While we can speculate that Wittgenstein dislikes the idea of this religious group, it is more likely that Wittgenstein has not bothered himself with religious movements or groups of this kind. There are simply no other items in NC concerning religious groups comparable to British Israelism; item 115 is the only item that touches a religious movement. Therefore, it is highly unlikely that Wittgenstein selects the item 115 for NC mainly because of it hinting on this ideology.

One can furthermore theorize that the person Elliott is the reason why items 54 and 55 are collected in NC; Elliott may be another figure, like Einstein and Dennis, of whom Wittgenstein likes to make fun. Einstein is said to be special for the Wittgenstein brothers, as they often make fun of him.11 However, while Einstein and Dennis appear in multiple items and in different contexts in NC, Elliott only appears in these two items. The low number of appearances hints that Elliott may not be in focus in NC because of his person. Even though newspapers often reported on sermons and open speeches by Spencer H. Elliott,12 Wittgenstein only collects those articles on the compatibility of science and Christ’s ascension. Nor can we find references to Elliott in Wittgenstein’s “Nachlass”, his collected literary remains. Thus, while Einstein is qua persona in the items in NC, Elliott is in NC for his sermons.

The last idea sees the reference to Einstein as the actual reason why item 55 is kept in NC. However, this is not plausible because Einstein is not among the main figures of the report! In other items where Einstein plays a role, Einstein is always the main reason for the report or the photograph. However, in item 55 Einstein’s role is marginal. He is mentioned because Elliott mentions him and used his lecture to back up the claim that modern science can give an explanation of why Christ seems to have ascended to heaven. From what is said in the article, we can even assume that Elliott did not have a good understanding of Einstein’s lecture. Unlike other items dealing with Einstein, item 55 is not collected because of Einstein.13

3. Wrong Ways of Putting Science and Religion Together?

Before I can continue elucidating why the way science and religions are “put together” is the real reason for these items being collected in NC, I must first give an account on the concept of nonsense in NC. The first remark is that the concept of nonsense in NC is not a clear one; in fact, “nonsense” could have been used by Wittgenstein as a word with the family-semblance feature14. Given the fact that the items in NC, a curated collection of nonsensical items, are very heterogeneous, we must assume that “nonsense” is not defined by one overarching feature within NC. We must also assume that Wittgenstein may have changed his criteria of nonsense during his life. The dating of the items spans over several decades, and it is probable that Wittgenstein has also changed his idea of nonsense in the course of time: some items that have not been collected may—retrospectively—be suitable for the collection, and others that are now part of NC would have fallen out. Since NC is a collection of jokes, Wittgenstein certainly did not concern himself with the possible inconsistency among items in NC. We can say that NC is not the result of a serious undertaking in collecting newspaper articles or other items that are nonsensical in one special regard.

We should also note that Wittgenstein probably has ridiculed most (if not all) of these items. This again suggests that the notion of “Blödsinn” (often translated as “drivel”, “nonsense” or “idiocy”)—in his own word: “Stiefel”15—played a central role in forming the collection. Items in NC must have been “rubbish” for Wittgenstein.16 If we want to draw conclusions from items in NC for the notion of nonsense or for Wittgenstein’s thinking on the relationship between religion and science, we must be careful. Items in NC should not be treated as a philosophical treatise that Wittgenstein rejects! Taken as a source for inspiration, this heterogeneous collection may be misleading!

As can be seen in the list of items in NC, in many of those items, just like in the three examples given above, science and religion are intermingled in a special way. We could perhaps characterize them as unsuccessful attempts to “harmonize” religious beliefs with scientific findings.17 We can therefore assume that the reason for this failure lies in the cognitive dissonance that is created when one takes both scientific and religious sentences literally.

Let us take the ascension of Christ as an example. According to physics, a person cannot ascend upward to heaven, and according to the Bible Christ did ascend to heaven. Since both cannot be true, if “ascending into heaven” has the same meaning in both claims, believers who do not want to be skeptical about science must find strategies to cope with this inconsistency. The opposite also holds: a scientist who wants to remain a believer also needs a way to cope with the incompatibility of these claims.

One way to resolve the cognitive dissonance is by re-evaluating religious statements using the framework of science; in this manner Elliott uses a special kind of mathematics to explain religious belief. According to Elliott, both claims are true when people think of Christ as a being that is able to move in the fourth dimension. Another way to cope with the incompatibility of scientific and religious statements is by showing that religious scripture already captures scientific theory that has been just developed, as Deans has hinted upon. If the prophet in Ezekiel has already seen the latest scientific progress, believers can keep the faith that the Bible will continue to contain scientific advances. In this manner, the claim that it is impossible for human beings to move towards the sky can be seen as the result of physics that has not yet reached the knowledge contained in the Bible.

The list of items in NC gives a good hint that these three items are not the only ones that deal with the (apparent) inconsistency of science and religion (see, e.g., items 50, 56, 77 and 87). As these items are in NC, we can conclude that, for Wittgenstein, the above attempts are nonsensical. However, given the reservation about the concept of nonsense presented before, we can see that it is very difficult to deduce why Wittgenstein regards these items as nonsense from NC alone. While we can assume that Wittgenstein rejects approaches to harmonize religion and science that are similar to those of Eliott and Deans, we cannot say that Wittgenstein rejects all attempts to harmonize religious belief with scientific findings. Here, we can only gain more insights into the thinking of Wittgenstein when we take his philosophy into consideration.

One approach is to follow the concept of nonsense given by McGuinness, as he writes about NC. McGuinness has studied items in NC in great depth and has gained a deep insight into the concepts of “nonsense” that Wittgenstein might have in mind when items were put into NC. According to McGuinness, one way to explicate what nonsense is for Wittgenstein is to see that words are misused. If a person transfers the words from one language game into another without adapting its usage, often nonsense will happen. This is like “bumping into the limit of languages” (McGuinness 2006). In some occurrences this is harmless and amusing, but at other times, the misuse of words will lead to confusion and misunderstandings. Put into the context of religion and science, a nearby speculation would be that when we mix the language of religion with the language of science—as witnessed in several items in NC—nonsense has been made. We could claim that Elliott has taken the word “fourth-dimensional” that is used in language games of mathematical discourses and put it into language games in the context of religious belief, and by doing so he has created nonsense. The opposite is also nonsensical. One should not take words used in religious languages games and put them into language games of science. Deans plays the language game of “citing the Bible” that is common among religious believers and inserts it into scientific debates; by doing so, he, too, has created an example of nonsense.

According to McGuinness, the misuse of words in language games is a sign that some barriers may have been broken. “Breaking barriers”—which can also be rephrased as “illegally crossing borders”—is another common “feature” found in items in NC. Einstein posing himself together with popular film actors is an example of him crossing the border of “good behavior for physicists” into the realm of “popular figures in show business”.

As McGuinness (in McGuinness 2006) focused on the notion of nonsense and did not mention the relationship between science and religion explicitly, he did not give us hints on the barrier between science and religion that has been broken. Clearly, in the items presented in this paper, we can claim that the misuse of language created nonsense. However, the inconsistency between scientific and religious statements expressed in these items does not just go away. Is there a way to put science and religion together adequately?

Here, we can find hints in philosophy of religion that is inspired by Wittgenstein. As is documented in LC, Wittgenstein rejects attempts to make religion reasonable by giving scientific reasons that are claimed to be. In the first “Lecture on Religious Belief” we find the following passage in which Wittgenstein claims that religious statements have different “reasoning”:

Here we have people [religious believers] who treat this evidence in a different way. They base things on evidence which taken in one way would seem exceedingly flimsy. They base enormous things on this evidence. Am I to say they are unreasonable? I wouldn’t call them unreasonable.I would say, they are certainly not reasonable, that’s obvious.’Unreasonable’ implies, with everyone, rebuke.I want to say: they don’t treat this as a matter of reasonability.Anyone who reads the Epistles will find it said: not only that it is not reasonable, but that it is folly.Not only is it not reasonable, but it doesn’t pretend to be.What seems to me ludicrous about O’Hara is his making it appear to be reasonable.(LC, 57f, italics in original).

Here Wittgenstein seems to suggest that religious beliefs neither require nor are eligible for “reasonability” or “justification”. Any attempts to do so would seem both inappropriate and superfluous, much like the Chinese idiom of “drawing a snake and adding legs”. Wittgenstein’s rejection of this kind of endeavor fits well into other claims of Wittgenstein about religious statements.18

Ilse Somavilla and Genia Schönbaumsfeld have clearly worked out that, for Wittgenstein, being religious is something that has an impact on the whole life of the believer (Schönbaumsfeld 2024; Somavilla 2024). Being religious does not simply mean that a person believes in the existence of a god. Rather, being religious means foremost that because a person believes in god she acts in a certain way in different contexts. The religious belief shows itself in the life of the believer (Somavilla 2024). If a person merely worships god at Sunday masses but does not act otherwise according to Christian values, Wittgenstein would not call such a person religious; instead, he would say that she does not understand her own religious belief. Religion is a kind of form of life. It is not simply a collection of language games that a person plays but has a deep impact on how somebody plays language games in general.

Additionally, Schönbaumsfeld has given a great overview of the relationship between scientific and religious statements (Schönbaumsfeld 2024). She points out that there are several features of religious sentences that make them different from ordinary “beliefs”: among others, such features include the subjective perspective in which religious statements are often formulated, and the deep impact of religious statements in many different contexts in the life of a believer. We can perhaps add another of such features: scientific claims are “volatile”. Scientific knowledge, e.g., knowledge on the laws of gravitation, may change over time. Unlike religious belief, scientific knowledge improves over time and has limited impacts on the life of a person. We improve our scientific knowledge by applying scientific methods and playing the language games of conducting scientific discussions. Scientists gather data, model a theory and then present it for other scientists for their judgements and comments. If a scientist has made any mistake, others can come and correct them. We can base new knowledge upon old knowledge and push the limit of knowledge forward, and when new knowledge is accepted, older theories will either be revised or invalidated. Through this kind of discourse, scientific theories—at least ideally—get better and better. Changes of religious statements, on the other hand, happen very slowly, and usually by re-interpreting the text itself.

Taking these differences into account, we gain another educated guess why Wittgenstein thought of these items in NC as nonsensical. These items are not only nonsensical, because words are misused, but also because of the differences in reasoning in religious and scientific statements. If religious beliefs are justified by scientific theories, we need to “re-fit” religious belief again and again, whenever newer scientific theories are established. Religious statements will become a corollary of scientific statements, and this clearly stands in contradiction to the common claim that, unlike scientific advances, religious statements do not change easily.19 If we justify scientific theories through religious belief or citations from the Bible, it would not be possible to understand why the scientific method works so well in science. If every advancement of science must be checked for how it fits or impacts religious sources, we will need additional strategies to cope with cases when scientific evidence contradicts religious sources.

If what is written above can be accepted, Wittgenstein rejected these two scenarios: 1. Scientific statements can justify religious belief. 2. Religious belief can justify scientific statements. Does this mean that science and religion have nothing to do with each other? However, the third option, that science and religion have nothing to do with each other, a position that can be termed “compartmentalism” (cf. Pichler 2025), must also be wrong, as a religious person will act “religiously” even in scientific contexts. A thorough discussion on the relationship between science and religion will go far beyond the scope of this paper. Pichler and Sunday Grève have written an extensive overview of different positions on Wittgenstein’s philosophy of religion (Pichler and Sunday Grève 2024; Pichler 2024). Here, I should emphasize that, while Wittgenstein rejects certain kinds of relationships between science and religion, it does not mean that all kinds of relationships proposed by scientists, philosophers and theologians are nonsensical.20

4. A Personal Matter?

From NC alone, we can only be sure that Wittgenstein has regarded the letter by Deans, the sermons of Elliott and other items concerning science and religion as nonsense. In NC, there are no explanations (given by Wittgenstein) as to why these items are nonsensical. We only know that these are examples of how science and religion should not be put together. Since NC is a collection of nonsense, we cannot expect to find positive items of how we can correctly join them within our lives, as they would not be nonsensical.

To my knowledge, Wittgenstein did not provide us with readily available solutions on how to put religion and science together. However, it seems that Wittgenstein struggled with the question, as Sunday Grève, Pichler and Schönbaumsfeld have all pointed out. (Pichler and Sunday Grève 2024; Schönbaumsfeld 2024). I suspect that the main reason why there is no solution by Wittgenstein lies in the fact that Wittgenstein thought of this question as a personal matter, because being religious is something personal. Furthermore, as people have different religious needs, their need for putting religion together with science may also differ. Therefore, the solution one person finds for herself may not be suitable for another person. An atheist, for example, does not need to take religious statements and their possible impacts on scientific findings into account. She could say that all religious statements are either false or nonsensical. She would not have an issue when she encounters religious statements that do not fit into scientific knowledge. On the other hand, when a believer is also a scientist, the relationship between science and religion (her personal belief) will be more complicated. If an astrophysicist believes that God created the universe, she must find ways to combine her belief with cosmological theories. With some theories, e.g., the Big Bang theory, it seems prima facie easier to join religious belief with a scientific theory. However, as scientific theories advance, the Big Bang theory may be replaced by another theory. When this happens, the believing scientist must find another way to cope with the newer theory, until another, better theory replaces the new one. This scientist, therefore, must always be ready to change her idea; having adapted to the Big Bang theory is not enough.

All these challenges boil down to a list of “intellectual obligations” that a person must fulfill if she holds both science and religious belief to be important for her life. For one, personal belief should not be superstition. A believer should not believe in just everything, but she should be able to reflect upon religious contents critically. The religion must be (in some sense) reasonable and defendable. Furthermore, religion should play a role in the life of the believer, i.e., compartmentalism is wrong (Pichler 2025). It should not be the case that the believer separates her life into different parts, and in some of them religious sentences are true while in others they do not matter. A religious belief concerns the whole person and her whole life. Last but not least, when an inconsistency between religion and science appears, the believer should be able to adjust her belief in the light of scientific findings without just giving it up easily. When confronted with scientific knowledge that seems to be incompatible with her belief, she should keep her belief faithfully, not simply by rejecting scientific knowledge but by adapting herself. According to Wittgenstein, this kind of clarification of the relationship between science and religion is something each person must do on her own. It belongs to the “work on one’s self” (Schönbaumsfeld 2024). In addition, it can be very difficult to balance out science and religion in one’s life, as the picture of rope-dancing used by Wittgenstein suggests (Pichler 2024).

As this must be done by each person, there can be no generalized solution. Wittgenstein does not provide one. Of course, thanks to works of other philosophers, theologians and scientists, we have some “role models” or “templates” that can help us in developing our own strategies and solutions to cope with apparent inconsistencies between science and religion. However, this remains a personal effort and cannot be generalized for other people.

The flip side of personal belief is the impact of religion and science on society as whole. A glance into the history of religion shows that religious authorities have been challenged by scientific findings. Galileo Galilei opposed the teaching of the Catholic Church that the sun revolves around the earth by contrasting this teaching with his findings. In his case, he was “‘vehemently suspected of heresy’ for holding and defending the thesis that the earth revolves around the sun and for thinking ‘that one may hold and defend as probable an opinion after it has been declared and defined contrary to the Holy Scripture’” (Finocchiaro 2021, p. 285).21 From the point of view of this paper, the case of Galileo is nonsensical, in the sense that a report on this case may have found its way into NC. The Church refutes a scientific thesis on the basis of an interpretation of the Bible, and this conflation between scientific and religious statements is just as nonsensical as other items in NC. For people living in the 17th Century, however, it must have been difficult to separate religion from astronomy. For one, astronomy was a young discipline, and at that time it did not deliver convincing evidence for the claimed movement of the earth around the sun. Furthermore, the movement of the sun and earth had a religious significance: the Catholic Church had proclaimed the correct interpretation of the Bible that the sun moves around the earth (and not the other way around).

The Catholic Church has rehabilitated Galileo (Finocchiaro 2021, chp. 14.7). However, even today, we can find nonsense when people cannot get the relationship between science and religion right. Modern equivalents of funny and humorous items in NC can be found in court cases. An example is the conflict around teaching Intelligent Design and the Theory of Evolution in biology classes at schools.22 How species come into being is a question for the scientific discipline of biology; thus, whether the Theory of Evolution or Intelligent Design is accepted is a question for biologists and should be answered using the methods in biology. However, certain groups of people demand that Intelligent Design must be taught to students in their the ninth grade biology class as an alternative to Theory of Evolution; they even require biology teachers to read statements aloud to students (Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School Dist. 2005, p. 708f), as if the religious belief of the students will be lost if they do not know at least one alternative theory to that of evolution.23

If what has been laid out in this paper can be accepted, we can speculate that Wittgenstein might have given specimens of the discussion on teaching Intelligent Design at schools a place in NC! The main difference between this discussion and the items in NC, though, is that this discussion is not a simple ludicrous sermon of a vicar, or an inspired letter by a physics student to philosophy professors, but it is a real court case that impacts the education of many children.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Transcription and Facsimile of NC Item No. 115: A Letter by C.W. Deans

Dear Sir,

I am a student of science and especially am I a student of the electromagnetic sciences which deal with rotary magnetic fields and I find that in order to get any right foundation for such studies I must project my mind back beyond the time in the universe when there was no matter as we know it today.

Let it be assumed that at one time in the universe only motionless space existed. This space we call the Ether. At some time in the past rotary whirls set up in the Ether and about rotary centres we had organized fields of motion. The only type of motion possible in a continuous medium is rotary motion to begin with in the galactic volumes of space. It is most foolish for our astrophysicists and cosmologists to assume that the universe was at one time filled with gases as we know them today. Where did those gases come from? This is a very serious thing when our so-called learned scientist think in this careless manner.

Before the gases existed then space or continuous ether existed. In order to fully understand the macrocosm and the microcosm we must try to visualize then the types of rotary motion that gave rise to all radiation photons and corpuscles from which matter is made. Before gases could exist ether was space in motion and the quantization of space is the problem which we must study carefully. It is the DIPOLAR VORTEX PHOTON in the Ether which we must study in order to get some idea of how continuous space could become quantized. What is a Dipolar Vortex Corpuscle?

It is a nucleus rotating with an axis and equatorial plane. This nucleus is a region of transformation of inbreathed ether streams polarwise into equatorial planar outbreathing ether fluid streams. The Letter X gives us a good picture of this form of motion. The letter X symbolizing the number 10 is really one vee set upon another vee upsidedown. The picture in the margin will illustrate what I mean.

It is the folly of modern mathematical scientist to discard the reality of the fluid substantial material unseen ether. What is wrong with the modern thinking concerning the ether is that the thinkers are not able to visualize the RIGHT FORM OF MOTION OF THE ETHER which form provides for the quantization of energy of ether rotation.

The quantization of energy of rotary ether is most important for it explains the existence of galactic fields and Suns’ fields and planetary fields in which are whirled and suspended all the material known at present in the Universe.

Imagine that the Planet Saturn has an unseen field such that into the north pole comes an unseen whirlpool of fluid ether and that into the south pole also comes a whirlpool of unseen fluid ether. These polar streams meet at the nucleus and at the nucleus these ether streams are changed into equatorial plane motion like a sheet of unseen flame spreading outwards. On this unseen sheet of etheric flame is suspended the rings and satellites of Saturn. This is an important thing to see. The Wheels within wheels of the Rings of Saturn are explained as being suspended on proper energy levels in this rotary equatorial sheet of etheric fire.

Orderly ether motion constitutes magnetic fields but disorderly or chaotic ether motion constitutes fire and heat and flame as we see in a candle flame for instance or as we see in a piece of sheet iron activated by a rapidly alternating magnetic field coursing through it periodically changing its direction continually.

The unseen Dipolar Rotary Ether field of Saturn is the DIPOLAR VORTEX CORPUSCLE in a large scale. The electron, the photon and the Alpha Particle is such a Dipolar Vortex Corpuscle with its vibratory polar intake and equatorial outlet of ether streams.

ELECTRON SPIN is something that the scientific philosophers and experimentalists in science are considering today. What causes and maintains such electron spin? This must be answered or else it is useless to consider electron spin seriously. The difference between Alpha, Beta and Gamma Ray Photons seems to be one of Rotational Sense. The polarization of Light Photons seems to be in the sense of rotation and the gyroscopic properties of the photon. These things must be considered as necessary parts of the DIPOLAR VORTEX THEORY OF ENERGY IN THE UNIVERSE.

In Ezekiel 1:4 and 27 we read of the DIPOLAR VORTEX WHIRLWINDS in the Ether. This is the source of all power in the Universe. Ezekiel saw visions of the SOURCE OF ETHER POWER at the River Chebar. Chebar means POWER in the Hebrew.

The Divine Code UNI/VER/S/E means ONE/POWER/SPIRALS(S)/IN THE ETHER(E). MA/T/TER means FLUID ETHER/AXIALLY/TURNING. MA in the Hebrew means WATER and in the HEBREW the word MATAR means RAIN or Corpuscle of Water. WATER in the Bible in Gen. 1:2,3; Jon 28:5 and II Esdras 16:58,59 and Psalm 136:6 signifies the FLUID UNSEEN ETHER. Study these things well O Scientists of Anglo Saxon Israel!

Yours for more Light in Israel Anglosaxondom!

C.W. Deans, M. Sc., M.E.I.C.

Figure A1.

NC item 115, recto. Courtesy of Research Institute Brenner-Archiv. Sig. 256/20-115.

Figure A2.

NC item 115, verso. Courtesy of Research Institute Brenner-Archiv. Sig. 256/20-115.

Appendix A.2. Transcription and Facsimile of NC Item No. 54, Report on a Sermon

THE ASCENSION

A Fourth-Dimensional Idea

Canon Spencer H. Elliott (vicar of Bolton), preaching yesterday at St. Ann’s Church, Manchester, said that the more one studied the Resurrection of Christ and His appearances after death the more one found that they fitted in with the mathematical fourth-dimensional idea. There should be nothing intrinsically absurd in the plain statement that when the disciples were assembled and the doors were shut “for fear of the Jews,” Christ appeared in their midst, unless we bound our thoughts to the idea of a world crudely measured in terms of time and space.

The Ascension had been dismissed by many people as an absurd story because they would insist that it meant that Christ ascended through a cloud upwards in a straight line to some distant point. That, of course, was absurd. It was not the story as it stood. As soon as one had any sort of idea of another state of being cutting across our three-dimensional world the story of the ascension seemed to him to ring true. And it seemed to follow that from the fourth-dimensional point of view the values of life were very different from what they appeared to be here and now; and from that point of view the standards of judgement were frequently reversed.

Figure A3.

NC item 54, recto. Courtesy of Research Institute Brenner-Archiv. Sig. 256/20-54.

Appendix A.3. Transcription and Facsimile of NC Item No. 55: A Report on a Sermon

ASCENSION DAY

The Vicar of Bolton at Westminster Abbey

REPLY TO CRITICISM OF SCIENTISTS

Canon Spencer H. Elliott, Vicar of Bolton, preaching at Westminster Abbey yesterday (Ascension Day), pointed out that the fact of the Ascension was misunderstood and even doubted by many people on supposedly scientific grounds. It was all very well some hundreds of years ago when people thought that the earth was flat, with nether regions below and heaven as a fixed place above the bright blue sky. Small children at the present day might still accept such an idea in all simplicity, but our better-informed intelligence could not accept that version. “When we look up at the sky we know we are looking in exactly the opposite direction to the upward gaze of people on the other side of the earth. What is ‘up’ to us is ‘down’ to them, and what is ‘up’ this afternoon will not be ‘up’ in the early hours of to-morrow morning, when the earth will have revolved on its axis.

“Yet it is very remarkable to notice, if we read the story carefully in St. Luke’s Gospel or in the Acts of the Apostles, that the plain facts are not necessarily contradictory to modern science. The story is quite simply told, and may be interpreted in a reasonable way. Indeed, I would go farther and suggest that the most recent discoveries of science have opened out a new interpretation which makes the story of the Ascension intensely real and very much up to date”.

Mathematics and Mystery

“Ever since I was a boy in the higher forms at school I have wondered whether mathematics may not provide us with actual proof of such a state of existence as the Gospels appear to reveal. I am not referring here to the square root of minus one, of which Mr. Baldwin very truly said in the House of Commons last week that no such thing exists. But I am thinking of those lines that run off to infinity when an algebraic expression is transmuted into a geometrical graph, and the remarkable way in which such a curve reappears at the foot of the paper after having run off at the top of it. You ask where the curve has been and whence it has come at once again, and the answer undoubtedly is that it has touched some higher dimension. If you are working on a two-dimensional sheet of paper, having length and breadth, but no depth or height, you find that you have escaped for a moment into the third dimension”.

“And in solid geometry, when you are working within a sphere or a cube, the same kind of thing happens, and you are bound to conclude that there is somewhere and somehow a still higher state of being. You cannot put your finger on it exactly, but you are driven to believe that it exists. You have, for instance, the proved mathematical fact that two circles which do not appear to touch or to cut one another do actually cross each other’s path in a realm which we call infinity”.

“All this no doubt is very elementary indeed to the skilled mathematician; yet we are given to understand that the very greatest of modern thinkers on this subject have developed this and similar ideas, so that we have Professor Einstein, in his Rhodes Lecture at Oxford last Saturday, explaining that time and three-dimensional space can no longer be viewed as absolute, but the absolute is accorded only to four-dimensional space”.

“Not Scientifically Absurd”

“Now with these ideas in our minds”, proceeded Canon Elliott, “we turn to the story of the Ascension, and there is nothing scientifically absurd about it. Indeed, going back to the incidents of the forty days between the Resurrection and the Ascension, we find our Lord moving freely in four-dimensional space, appearing from time to time to mortal sight, yet coming and going when doors were shut, and breaking through the limitations of our earthly existence. Then, on Ascension Day, a cloud resting on the hilltop received Him out of their sight, and when the cloud rose from the earth He was gone. It is not difficult to accept the simple statement that ‘He was parted from them and carried up into heaven’ if we use the word ‘up’ to denote the passing out into the life of a higher dimension, and if we understand that heaven is not so much a place as a higher state of being. Heaven no doubt reaches far beyond the sky, but also it cuts across this earthly plane. We in this world are subject to limitations of the five senses, and can seldom or never see what lies beyond. Yet the orbit of the earth touches the infinite, and the infinite reaches to us”.

Figure A4.

NC item 55, recto. Courtesy of Research Institute Brenner-Archiv. Sig. 256/20-55.

Notes

| 1 | It is necessary to note that the original box containing items of NC is probably lost. When McGuinness gave the Brenner-Archiv a box, the items were already organized in plastic wraps, simply because some of these items were already very fragile. |

| 2 | A more thorough description of the Nonsense Collection can be found in Wang-Kathrein (2023). For the purposes of their own research, Brian McGuinness and Anna Coda Nunziante have catalogued the items in NC. The catalogue is now also available in the Brenner-Archiv, and this article has used this catalogue extensively. |

| 3 | Aside from the letters mentioned in this paper, there are several letters in Wittgenstein’s correspondence showing that Wittgenstein consistently curated NC since the 1920s. See: Wang-Kathrein (2023). |

| 4 | Cf. the online collection inventory list of the Brenner-Archiv, especially Cassette No. 20: https://www.uibk.ac.at/de/brenner-archiv/bestaende/mcguinness/ (accessed on 31 January 2025). All items in NC are cited using “NC” and its item number. Please note that we have not discovered the identifies of all the authors / creators of items in NC; that is the reason why information on the list seems to be sparse. |

| 5 | See also the accompanying letter by W.H.Watson to Ludwig Wittgenstein, 6 March 1932. All letters are referenced after McGuinness and Wang (2011). |

| 6 | Letter from Wittgenstein to Piero Sraffa, dated on 24 October 1950. |

| 7 | I thank my colleague Ulrich Lobis for the explanation. |

| 8 | Here I should admit that both the counting of items and the attribution to categories “religion” and “science” are somewhat arbitrary and can therefore be misleading. For example, one could combine all articles from the series “Where are the Deads” into one item, and by doing so reduce the number of items in NC. One could also separate spiritualism from religion, and by doing so distinguish between religious beliefs and superstitions. Furthermore, it would make sense to distinguish articles about science from articles about scientists, as one can argue that some articles in NC are about the person Albert Einstein and not about his theories in physics. Given the small amount of items in NC, using different strategies to count will result in a large difference in the statistics. However, it will still be undeniable that the subjects “religion”, “science” and “religion with science” play dominant roles in NC. |

| 9 | In an archived version of the website of St. Peter’s Church, Bolton, Elliott is enlisted as vicar between 1930 and 1933. See the file “Life of the Priest” archived in the Internet Archives, online resource under: https://catholicebooks.wordpress.com/2023/08/08/online-text-letter-to-all-priests-1979-by-saint-john-paul-the-great/ (accessed on 5 February 2025). |

| 10 | Einstein gave a lecture on 9 May 1931 in Oxford, which was a Saturday (Fox 2018, p. 297). The following Thursday, 14 May 1931 happens to be the Ascension Day of that year. |

| 11 | McGuinness reported that Paul and Ludwig Wittgenstein both ridicule the way Einstein behaves in public. According to McGuinness, the Wittgenstein brothers must have thought that it does not behoove physicists to be pictured together with film stars. See: McGuinness (2006). |

| 12 | A query in The British Newspaper Archive (https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/, accessed on 4 February 2025) shows that the phrase “Spencer H. Elliott” shows up in many different—mostly clerical—newspapers. |

| 13 | Similarly, the article titled “Einstein is Wrong, Callahan Claims” (NC item 68) is not in NC because of Einstein. |

| 14 | Alois Pichler expressed this idea in a private conversation on NC. |

| 15 | The Wittgenstein brothers called these items “Stiefel”, a Viennese pejorative for nonsense. Cf. McGuinness (2006) and e.g., letter from Paul Wittgenstein to Ludwig Wittgenstein, 1. 5. 1936. |

| 16 | In a lecture Hanoch Ben-Yami uses the gesture of pulling out one’s hair to denote how Wittgenstein could have felt about items in NC. The lecture was given during the conference “Ingeborg Bachmann und Ludwig Wittgenstein. Literatur und Philosophie” and took place on 16 May 2024 in Innsbruck. See: https://www.uibk.ac.at/de/philosophie/forschung/veranstaltungen/ingeborg-bachmann-und-ludwig-wittgenstein-literatur-und-philosop/ (accessed on 6 February 2025). |

| 17 | Of course, in a single item there may be multiple factors that lead Wittgenstein to think it as nonsensical; these factors are subjects of interpretation. Even when science and religion play a role in one item, the main reason why it is nonsensical may not have anything to do with the relationship between these two disciplines. |

| 18 | See an excellent overview of different positions in Pichler and Sunday Grève (2024). |

| 19 | It should be remarked here that this does not mean that we cannot change or re-interpret religious belief in a new way in the light of scientific findings. However, while through re-interpretation the “power” of religious beliefs to impact on many different language games is not lost, justifying religious belief through scientific theories would really make religious belief a part of scientific discussions. |

| 20 | I thank an anonymous reviewer for hints on philosophers and theologians who have extensively worked on the borderline between science and religion. Scholars that are both scientists and theologians (like John Polkinghorne and Arthur Peacocke) have proposed different ways make scientific advance fruitful for theology. While Schönbaumsfeld in Schönbaumsfeld 2024 (already in Schönbaumsfeld (2007)) rejects certain traits of the so-called reformed epistemology from a Wittgensteinian perspective, philosophers like Nancey Murphy (e.g., in Murphy 2003) take up (not only) Wittgensteinian philosophy to make philosophy an indispensable tool for the dialogue between science and religion. Furthermore, Otto Muck has enlisted differences between scientific discussions and discourses on world views; by doing so, he works out that the criteria for scientific discourses and for world views must be different to each other (Muck 1999). All these endeavors can help us clarify the relationship between science and religion, and they are very different to items in NC presented in this paper. |

| 21 | Here Finocchiaro translates from Le opere di Galileo Galilei, edited by A. Favaro et al., vol. 19, p. 405. |

| 22 | See Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School Dist. (2005). Several academic articles have dealt with this matter, cf. e.g., Nagel (2008); Barnes/Church/Draznin-Nagy (Barnes et al. 2017). |

| 23 | Cf. the reasons given why teaching Intelligent Design is necessary in Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School Dist. (2005), e.g., p. 749f. |

References

- Barnes, Ralph M., Rebecca A. Church, and Samuel Draznin-Nagy. 2017. The Nature of the Arguments for Creationism, Intelligent Design, and Evolution. Science & Education 26: 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finocchiaro, Maurice A. 2021. Science, Method, and Argument in Galileo. Philosophical, Historical, and Historiographical Essays. Cham: Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, Robert. 2018. Einstein in Oxford. Notes and Records 72: 293–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School Dist. 2005. 400 F. Supp. 2d 707 (M.D. Pa. 2005). Available online: https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp2/400/707/2414073/ (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- McGuinness, Brian. 2006. Praise of Nonsense. In Le ragioni del conoscere e dell’agire. Edited by Rosa M. Calcaterra. Milano: Franco Angeli, pp. 357–65. [Google Scholar]

- McGuinness, Brian, and Joseph Wang, eds. 2011. Wittgenstein: Gesamtbriefwechsel/Complete Correspondence, 2nd Release. Innsbrucker Electronic Edition. Charlottesville: InteLex. [Google Scholar]

- Moshenska, Gabriel. 2008. ‘The Bible in Stone’: Pyramids, Lost Tribes and Alternative Archaeologies. Public Archaeology 7: 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muck, Otto. 1999. Rationale Strukturen des Dialogs über Glaubensfragen. In Otto Muck: Rationalität und Weltanschauung. Philosophische Untersuchungen. Innsbruck: Tyrolia, pp. 106–51. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, Nancey. 2003. On The Role of Philosophy in Theology-Science Dialogue. Theology and Science 1: 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, Thomas. 2008. Public Education and Intelligent Design. Philosophy & Public Affairs 36: 187–205. [Google Scholar]

- Pichler, Alois. 2024. Glaube und Aberglaube nach Wittgenstein: Zu nonkognitiven Deutungen der Grammatik des religiösen Glaubens. In Religionsphilosophie nach Wittgenstein—Sprachen und Gewissheiten des Glaubens. Edited by Esther Heinrich-Ramharter. Berlin: J. B. Metzler, pp. 245–86. [Google Scholar]

- Pichler, Alois. 2025. “For If There Is No Resurrection of the Dead, Then Christ Has Not Been Raised Either”: Wittgenstein and the Cognitive Status of Christian Belief Statements. Religions 16: 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichler, Alois, and Sebastian Sunday Grève. 2024. Cognitivism about Religious Belief in Later Wittgenstein. International Journal for Philosophy of Religion 97: 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönbaumsfeld, Genia. 2007. A Confusion of the Spheres: Kierkegaard and Wittgenstein on Philosophy and Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schönbaumsfeld, Genia. 2024. ‘Making it a Question of Science’—Wittgensteins Kritik an Father O’Hara und dem Szientismus in der Religion Wittgenstein über religiösen Glauben. In Religionsphilosophie nach Wittgenstein—Sprachen und Gewissheiten des Glaubens. Edited by Esther Heinrich-Ramharter. Berlin: J. B. Metzler, pp. 73–92. [Google Scholar]

- Somavilla, Ilse. 2024. “Wenn etwas Gut ist so ist es auch Göttlich”: Der Zusammenhang zwischen Ethik und Religion bei Wittgenstein. In Religionsphilosophie nach Wittgenstein—Sprachen und Gewissheiten des Glaubens. Edited by Esther Heinrich-Ramharter. Berlin: J. B. Metzler, pp. 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- Uhlenbeck, George E., and Samuel Goudsmit. 1926. Spinning Electrons and the Structure of Spectra. Nature 117: 264–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang-Kathrein, Joseph. 2023. Brian McGuinness and Wittgenstein’s Nonsense Collection. Paradigmi 41: 193–207. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, John. 1968. British Israelism: A Revitalization Movement in Contemporary Culture. Archives de Sociologie des Religions 13: 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig. 1966. Lectures and Conversations on Aesthetics, Psychology and Religious Belief. Edited by Cyril Barrett. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).