Abstract

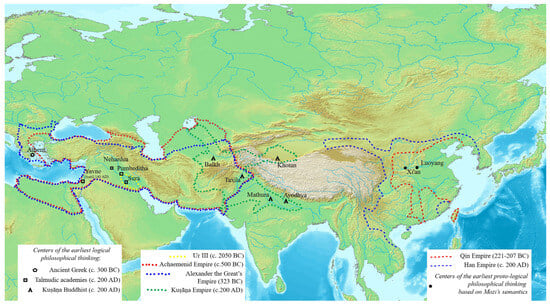

This paper explores the origins and global significance of Judaic hermeneutics as a foundational logical culture, arguing that it constitutes one of the earliest and most sophisticated systems of reasoning in human history. Far beyond a method of religious interpretation, Rabbinic hermeneutics represents a logic in practice: a structured, culturally embedded framework of inference rules (middôt), such as qal wāḥōmer (a fortiori reasoning), that guided legal deliberation and textual exegesis. By comparing Judaic hermeneutic methods with Greco-Roman rhetoric, Indian logic, and Chinese philosophy, this study reveals that similar logemes—elementary reasoning units—appear only in these four ancient traditions. All emerged within a narrow geographic corridor (32–38° N latitude) historically linked by trade routes, particularly the Silk Road. Drawing on legal documents and logic history, this paper argues that logical cultures did not arise from isolated individuals, but from collective intellectual traditions among elites engaged in commerce, law, and education. Judaic hermeneutics, with its roots in Babylonian legal traditions and its codification in the Talmud, offers a clear example of logic as a communal, evolving practice. This study thus reframes the history of logic as a pluralistic, global phenomenon shaped by cultural, economic, and institutional contexts.

Keywords:

Judaic hermeneutics; Judaic logic; Talmud; Indian logic; Greek logic; Chinese logic; Silk Road 1. Introduction

The tradition of Judaic hermeneutics—particularly as it evolved through the Babylonian and Jerusalem Talmuds—constitutes one of the most sophisticated and enduring systems of legal and textual interpretation in world intellectual history. Far from being limited to scriptural commentary, this tradition functions as a form of applied logic (Schumann 2023b): a culturally embedded, normatively governed, and philosophically robust system of reasoning. Central to this tradition is a body of interpretive principles known as middôt (מִדּוֹת, ‘measures’ or ‘rules’), which serve as foundational tools for halakhic (legal) and haggadic (historical) analysis and exegesis.

One of the most frequently employed of these principles is qal wāḥōmer (קל וחומר), or a fortiori inference. This structure, deeply integrated into Rabbinic thought, mirrors certain forms of abductive inference, which today can be formalized through non-monotonic matrices (Abraham et al. 2009) or modeled using frameworks of parallel reasoning (Schumann 2011). The logical force of this and other inference types was recognized and systematized by the early sages of the Talmud, which embedded them within a recurring framework for deriving legal conclusions from canonical texts. However, this is only one dimension of a much broader and more nuanced landscape of Rabbinic reasoning.

A distinctive hallmark of this tradition is its complex treatment of rationality, agency, and conditionality. One particularly rich example is the legal construct of gēṭ ʿal tənaʾi (גֵּט עַל תְּנַאי), or ‘conditional divorce’. In this halakhic structure, a divorce may be made retroactively effective upon the fulfillment of a specified future condition. As demonstrated by Abraham et al. (2014) and Rowe and Gabbay (2024), this practice anticipates modern discussions in logic and legal theory, engaging with temporal loops, counterfactual conditions, and forms of non-monotonic reasoning. What appears at first as a legal technicality is in fact a highly sophisticated application of logical principles in real-life contexts.

The unique status of Judaic hermeneutics as a system of logic was first brought to scholarly attention by Hirsch S. Hirschfeld (1840), who argued that its principles could be formalized and analyzed as rigorous logical operations, rather than merely rhetorical tools. Later scholars, including Sergey Dolgopolsky (2012a, 2012b, 2024), further demonstrated that Rabbinic hermeneutics is rooted in a distinct conceptual framework, one that assumes specific ideas about rational agents, interpretive authority, and normative dialogue. Logic in this setting is not isolated from communal life—it is enacted through legal discourse, textual tradition, and social practice. It represents not a logic of detached propositions, but a logic of living law: dialogical, situated, and historically responsive.

This article aims to offer a comprehensive analysis of the logical operations embedded in Judaic hermeneutics and to evaluate their significance in the broader history of logic. In doing so, it critiques the still-prevalent view that attributes the origins of logic almost solely to Greek philosophy. Instead, this study adopts a comparative and global lens, positioning Rabbinic logic alongside the three other major ancient traditions of structured reasoning: Greco-Roman, Indian, and Chinese.

Crucially, there is substantial evidence that Judaic hermeneutics was shaped in part by the Babylonian intellectual and legal milieu, particularly during and after the Babylonian Exile. Various Rabbinic terms and interpretive strategies show strong resemblances to those found in Akkadian commentary traditions, suggesting more than incidental overlap. Rather, what emerges is a shared logic game, with structurally parallel forms of legal argumentation and textual analysis. Within this historical framework, the figure of Ezra—scribe, priest, and reformer—appears as a pivotal systematizer of this early Judaic logical culture, drawing perhaps upon Babylonian legal templates to develop a distinctly Jewish model of legal rationality.

The structure of the article is as follows. Section 2 examines the Babylonian context of the Judaic diaspora, highlighting parallels with Akkadian legal and exegetical traditions and the possible influence of Babylonian legal culture on Rabbinic structures of argument. Section 3 focuses on the earliest Rabbinic schools of interpretation, particularly those of Hillel, Rabbi Ishmael, Rabbi Akiva, and Rabbi Eliezer ben Rabbi Yose ha-Glili, who transmitted and refined the foundational principles of Talmudic logic and exegesis. Section 4 presents a comparative analysis between Judaic hermeneutics and Greco-Roman logic and rhetoric, exploring similarities in logical schemata, such as enthymemes, inferences by analogy, and rhetorical figures. Section 5 explores the Indian intellectual traditions, especially Nyāya logic, Mīmāṃsā hermeneutics, and Alaṅkāraśāstra poetics, uncovering surprising parallels in methods of textual interpretation and normative reasoning. Section 6 turns to classical Chinese philosophy, with particular attention to the Mohist school’s logical tools and the Confucian doctrine of the ‘rectification of names’, which, like Rabbinic logic, integrates ethical normativity with linguistic precision and inference rules. Section 7 offers a synthesis of the findings and reflects on the unique historical conditions that gave rise to formalized reasoning in only a few ancient cultures: Judaic, Greco-Roman, Indian, and Chinese. Despite their geographical and cultural differences, these cultures developed structurally analogous approaches to logical reasoning.

To sum up, this study argues that Judaic hermeneutics should not be understood merely as a religious form of interpretation. Instead, it represents a vital and globally significant contribution to the history of logic—one grounded in textual rigor, communal ethics, and legal creativity. Through its distinctive techniques of inference and interpretation, Rabbinic reasoning offers a powerful model of how logic can serve not only abstract analysis but the real, lived complexities of social and legal life.

2. The Mesopotamian Roots of Judaic Hermeneutics

Akkadian documents provide strong evidence that many Judeans after the Babylonian captivity became deeply integrated into Babylonian society, securing a middle-tier or even high position within its intricate social and economic hierarchy. Many exiles engaged in trade, maintaining strong connections with Judah. The Hebrew Bible reinforces this notion, underscoring continued communication between the Judean exiles in Babylonia and those who remained in their homeland. Jeremiah 29 describes the exchange of letters between these regions, while Jeremiah 51 records a prophecy against Babylon delivered by a Judean royal official. Similarly, Ezekiel 33:21–22 recounts how a Judean refugee brought news of Jerusalem’s destruction to the exiles. These accounts reflect the sustained connections and dynamic interactions between the Jewish communities of Babylonia and Judah.

Starting with the Babylonian captivity, the movement of people, goods, and ideas between Jewish communities across various regions of Eurasia and Africa is thoroughly documented (Oppenheimer 2005, pp. 417–32; Hezser 2011, pp. 311–64). Trade along the Silk Road has facilitated these interactions since the 2nd century CE, and Jewish businessmen have continued playing a crucial role in international commerce. For instance, a Jewish prayer written in Hebrew, dating from the 7th to 9th centuries (Pelliot hébreu 1 or hébreu 1412), was found in the Buddhist monastery’s Library Cave (Cave 17) in Dunhuang (Chinese Turkestan), alongside pure Buddhist texts (Koller 2024).

Babylonia’s economy, rather than being strictly state-controlled, provided opportunities for diverse participants, including Jewish merchants, to engage in trade. Some Judean individuals were designated as tamkāru (‘merchant’) or tamkār (ša) šarri (‘royal merchant’), but many urban families participated in trade without holding these official titles, demonstrating the diverse economic roles available to Judeans (Alstola 2007, p. 80). Meanwhile, it is significant that none of their documents were issued on Jewish holidays, which serves as additional evidence of their Judean identity.

One of the notable Judean merchant families in Babylonia was the Arih lineage, a family of Judean royal merchants based in Sippar. A marriage contract (BM 65149 = BMA 26) published by Martha T. Roth (1989) details the union of Kaššāya/Amušê, a Judean bride from the Arih family, with Guzānu/Kiribtu/Ararru, a Babylonian groom, during the fifth year of Cyrus. Her union with a Babylonian, the presence of Babylonian witnesses in the contract, and adherence to Babylonian legal norms all illustrate the high integration of Judeans into Babylonian society. A notable detail in her dowry is the inclusion of an Akkadian bed (gišná ak-ka-di-i-tu4), a rare but prestigious item, reinforcing her family’s social standing (Alstola 2007, p. 97).

Other cuneiform tablets provide insight into the commercial activities of the Arih family. Among them, from the tenth year of Nabonidus (BM 75434, 18-II-10 Nbn, 546 BCE), is a promissory note indicating that the royal merchant (tamkār šarri) Basia, son of Arih, owed silver to Marduka/Bēl-īpuš/Mušēzib, a Babylonian tithe farmer (ša muhhi ešrî) of the Ebabbar temple in Sippar (Alstola 2007, p. 83). We see, as a consequence, that Basia occupied a high social position. Another cuneiform document (BM 74411, 544 BCE) is a receipt of sale, likely connected to the Ebabbar temple. The seller of gold was Amušê/Arih, reinforcing the commercial role of Judeans in the region. Other records illuminate the social networks of the Arih family. A lease agreement (CT 4 21a, 503 BCE) documents the rental of 30 haṣbattu vessels for a beer brewing and tavern business (Alstola 2007, p. 90). The lessee, Šamaš-uballiṭ/Nādin/Bāˀiru, and the lessor, Rīmūt/Šamaš-zēr-ibni, transacted before key witness Bēl-iddin/Amušê, likely a brother of Kaššāya. This suggests strong Judean involvement in urban economic enterprises, further illustrating the breadth of Judean participation in Babylonia’s economy.

Arih’s family had their residence in the city of Sippar, located on the Euphrates, which was a key trade hub, allowing Jewish merchants to integrate into Babylonian commercial networks. Its proximity to major trade routes connected Babylonia with the Iranian plateau and the Levant, reinforcing economic ties between Jewish communities in both regions.

The Murašû archive provides further evidence of the middle or even high status of Judeans in Babylonia. Discovered in Nippur, the archive documents the dealings of the Murašû family, who served as intermediaries between state authorities and landholders. Judeans appear in this context as key participants in the land-for-service sector, though their precise roles varied. Some may have been landholders, representatives of community groups, minor officials, or entrepreneurs engaged in subleasing agricultural holdings. A collection of twelve texts shows the involvement of Judean figures such as Pili-Yāma/Šillimu, Yadi-Yāma/Banā-Yāma, and YadiYāma’s son Yāhû-natan, all of whom were active in land transactions and leasing agreements in Bīt-Gērāya between 441–425 BCE (Alstola 2007, p. 170).

Further evidence of Jewish participation in Babylonian society is contained in land records. Eleven Judeans appear in seven documents as co-holders of these agricultural plots, indicating a collective approach to land tenure. In six cases, bow lands (ša qašti) were registered under multiple names, and four documents refer to groups identified as ‘brothers’ (šeš.meš; BE 10 118; EE 111) or ‘lords of the bow land’ (lúen.meš gišban; PBS 2/1 89, 218)—see (Alstola 2007, p. 182). This pattern, consistent throughout the Murašû archive, suggests that bow lands were typically managed by groups rather than individuals, further supporting the idea that Judeans held a middle position in Babylonian society, actively participating in its economic framework while maintaining their own communal structures.

Akkadian documents mention a major Jewish settlement in Babylonia called Ālu ša Yāhūdāya (C1, 20-I-33 Nbk, 572 BCE), Āl-Yāhūdāya (B1, 7-IX-38 Nbk, 567 BCE), or Āl-Yahūdu, ‘City of the Judeans’, located near Babylon. Sometimes, Āl-Yahūdu is mentioned along with Ālu ša Našar (‘Town of Našar’) and Bīt-Našar (‘House of Našar’). For example, in the tablet C83, a tax record mentions a dēkû official from Āl-Yahūdu collecting payments in Našar, and in the tablet C84, a promissory note from Našar specifies the delivery of goods to Āl-Yahūdu (Alstola 2007, p. 105). This Āl-Yahūdu was incorporated into a larger administrative unit known as šušānu Yahūdāya, or the ‘unit of Judean state dependents’. It was established by the local authorities to streamline the collection of rent and taxes from the Judeans and to regulate their conscription into the army. However, many Jewish exiles seem to have also been relocated to central and southern Mesopotamia. In these regions, toponyms such as Tel-Aviv, Tel-Melah, and Tel-Harsha appear (Ezra 2:59; Zadok 2002).

After the fall of the Neo-Babylonian Kingdom and the rise of the Achaemenid (Persian) dynasty of Mesopotamia, Aramaic emerged as the lingua franca of the Achaemenid Empire, becoming the dominant language used for administration, communication, and trade across a vast swath of territories stretching from the Indus Valley to the Mediterranean. The Achaemenids, recognizing the practical utility of Aramaic for managing a large and diverse empire, adopted it as the main official language of the state. Despite the ascendancy of Aramaic, Akkadian, the leading official language of the former New Babylonian Kingdom, was not entirely abandoned. It continued to be used in some contexts, particularly in legal and scholarly settings, as well as in certain administrative areas in the region of Mesopotamia.

The widespread use of Aramaic as the official language had significant consequences for the Jewish communities within the empire. While many Jews continued to speak Hebrew, especially in religious contexts, Aramaic became increasingly important for everyday life, trade, and governance. This transition is evident in various texts and inscriptions from the period, including those from Jewish communities outside of the immediate region of Judah.

One prominent example comes from the Jewish community in Elephantine, an island in the Nile River in Egypt, where a thriving Jewish settlement existed during the Achaemenid period. Legal documents and letters from this community, written in Aramaic, provide valuable insights into the lives of Jews living under Persian rule (Porten 1996). These documents reveal that Jews maintained significant social and economic positions within the larger Achaemenid Empire. Many Jews in Elephantine were engaged in various administrative roles, such as guards for the Persian administration, a position of trust and authority. Others were active in trade, functioning as merchants who facilitated commerce between different parts of the empire.

The fact that Judeans held such prominent positions in the administration and economy reflects not only their integration into the broader Babylonian (and later Persian) imperial structure but also the relative autonomy and prosperity they enjoyed in some regions, such as Elephantine. These roles suggest that Judeans were well-respected and trusted within the imperial system, a situation that allowed them to retain a significant degree of influence and maintain their social status in both local and regional contexts. The use of Aramaic in these documents also underscores the linguistic shift that took place in the Achaemenid period, marking a clear break from earlier Babylonian dominance and reflecting the broader cultural changes occurring in the empire.

In 539/8 BCE, after the conquest of Babylon by King Cyrus II, the Persian king issued a significant edict that is famously recorded in the Bible in the Book of Ezra (1:2–4 and 6:3–5). This decree allowed the Jewish people, who had been exiled in Babylon for several decades, to return to their ancestral homeland in Judah and rebuild the Temple in Jerusalem, which had been destroyed by the Babylonians under King Nebuchadnezzar II in 586 BCE. This return was not only a religious act but also a political one, signaling Cyrus’s desire to restore local religious practices and consolidate his empire by gaining the favor of his subjects. In his decree, Cyrus also ordered the return of sacred vessels that had been looted by Nebuchadnezzar when he sacked Jerusalem. The Persian king, in his decree, recognized the influence and authority of the Jewish diaspora in Babylonia over the returnees in Judah. This acknowledgment suggests that the Jewish community in Babylonia (such as in Āl-Yahūdu), which had flourished and developed its own institutions during the exile, maintained a kind of parental authority over the newly re-established community in Judah (Ezra 7:14).

Ezra, a priest and scribe, was commissioned by the Persian king Artaxerxes to return to Judah to teach the laws of God and ensure their observance. Ezra’s arrival marked a significant moment in Jewish history, as he brought with him not only religious leadership but also the legal traditions of the Babylonian diaspora. The practices and laws followed by Jews in Babylon had evolved during the exile and were now incorporated into the governance of the community in Judah. One of the key aspects of this integration was the emphasis on Torah observance, which became central to the community’s identity. Ezra’s efforts to establish the Torah as the foundation for the laws and customs of the Jewish people were instrumental in solidifying the distinctiveness of the Jewish community, both in Judah and in the diaspora. As a result, the Jewish community in Judah became increasingly aligned with the religious practices of the Babylonian diaspora, indicating a shift towards a more unified and standardized Jewish identity across the Persian Empire.

Nevertheless, the historical accuracy of the accounts in Ezra and Nehemiah, describing the Jewish diaspora in the Persian Empire, remains a topic of scholarly discussion. Some researchers argue that both books contain a mix of authentic archival material and later editorial additions. The use of Aramaic in portions of Ezra 4:8–6:18 suggests the inclusion of official Persian-era documents, though the extent to which they were modified or redacted is uncertain. The presence of both first-person and third-person narratives in Ezra 1–6 further complicates the issue, raising questions about the composition process and the role of later editors. In addition to the Aramaic documents of Ezra, the narratives of Nehemiah also provide valuable insights into the socio-political dynamics of Persian-period Judah. The ‘Memoir of Nehemiah’, which forms the core of Nehemiah 1–7 and 11–13, is considered a crucial historical source. Scholars generally agree that this memoir, written in the first person, reflects Nehemiah’s own account of his leadership efforts in rebuilding Jerusalem’s walls and reforming the community. The dating of the ‘Memoir of Nehemiah’ varies, with some scholars placing it in the middle of the 5th century BCE and others closer to the century’s final quarter.

Rabbinic Judaism began to take shape during the Babylonian captivity and the subsequent expansion of the Jewish diaspora in Babylonia. This period saw the development of legal traditions and interpretative methods that would later form the foundation of the Talmud. The dialect of Aramaic used in the Babylonian Talmud is closely related to Imperial Aramaic, distinguishing it from the Aramaic of the Peshitta, which differs more significantly from the Imperial Aramaic grammar. This linguistic connection suggests that the legal traditions of the Talmud emerged in Babylonia during Achaemenid rule.

Beyond language, there is evidence that Mesopotamian scholarly traditions influenced Judaic exegetical methods. The interpretative techniques found in Mesopotamian cuneiform commentaries from the second half of the first millennium BCE bear striking similarities to later Judaic hermeneutics. One such example is the Akkadian term kayyān(u) (‘regular, real, actual’), which was used in commentaries to indicate the literal or contextual meaning of a word, in contrast to a more expansive interpretation. This term has a parallel in the Hebrew words waddaʾi (וַדַּאי) and mammāš (מַמָּשׁ), which serve a similar function in Tannaitic halakhic mid̲rāš (Gabbay 2017).

The influence of Mesopotamian exegetical traditions on Judaic interpretation can also be seen in the use of nôṭārîqôn, a method of deriving new meanings from words based on their individual components. Akkadian commentaries employed similar techniques, as illustrated in the interpretation of the word agurru (‘baked brick’)—see (Gabbay 2017, p. 78). In this example, agurru is interpreted in three ways: (1) literally, as a baked brick, (2) metaphorically, as a reference to a man who has returned from a river ordeal, based on the breakdown of the word into components meaning a (‘water’) and gur (‘return’), and (3) as a symbol for a pregnant woman, with its components meaning a (‘son’) and gur (‘carry’). This multilayered approach to textual meaning mirrors the midrashic methods later used in Rabbinic literature.

Additionally, Mesopotamian commentaries applied analogical reasoning in their interpretations. The Akkadian phrase kīma . . . ibaššīma (‘it is like…’) functioned as a tool for drawing comparisons (Gabbay 2016, p. 119), much like the Judaic method of gəzērāh šāwāh (גְּזֵרָה שָׁוָה), which links Biblical passages based on similar language. Similarly, the Akkadian verb mašālu (‘to resemble’) was used to establish connections between concepts, as seen in a commentary likening a ‘bird-snare’ to a specific type of vessel, emphasizing its wide base and narrow opening:

[k]i-ma ḫu-ḫa-ri ana sa-ḫa-pi-ia/ma-a ḫu-ḫa-ru: ana giškak-kul-li ma-šil/šá ME UD x ˹SUḪUŠ-šú˺ DAGAL KA-šú qa-ta-an/ZA? [x x (x x)] x-ni-iš ana É.SIG4 x [x Š]UB?-u?

““To clamp down on me as a bird-snare”—thus: “bird-snare”—it resembles a kakkulu-vessel, whose . . . base(?) is wide and whose opening is narrow … towards the wall … are cast(?)”.(Gabbay 2016, p. 120)

Another notable parallel is the Akkadian phrase (lū …) lū (‘either… or…’), which introduced alternative interpretations or explanations (Gabbay 2016, p. 122). This corresponds to Rabbinic hermeneutic techniques that present multiple possibilities for understanding a text, reflecting a shared tradition of layered and flexible exegesis.

These similarities suggest that Judaic scholars in Babylonia, particularly during the Neo-Babylonian, Achaemenid, and subsequent periods, were engaged with and influenced by the broader intellectual traditions of Mesopotamia. Being deeply integrated into the Babylonian business environment, the Judeans were thereby integrated into the complex legal practices of the Babylonians, including legal exegesis. The methods they developed were likely shaped by the interpretative frameworks already in use in the region, demonstrating a cultural and scholarly exchange between Jewish and Mesopotamian traditions.

3. Early Judaic Hermeneutics in the First Rabbinic Academies

Hillel the Elder (c. 110 BCE–10 CE) was one of the earliest Tannāʾîm (תַּנָּאִים), the Judaic scholars who became the founders of the Talmud. Born in Babylonia, he was a leading Judaic teacher during the time of King Herod. Hillel played a key role in developing methods for interpreting Jewish law, particularly through his seven hermeneutic principles, known as middôt (מִדּוֹת). For the first time, he presented these principles to the sages of the House of Bathyra. The ʾĀb̲ôt̲ dərabbî Nāt̲ān (35:10)1 enumerates these rules as follows:

- qal wāḥōmer (קַל וָחֹמֶר)—‘an a fortiori argument’;

- gəzērāh šāwāh (גְּזֵרָה שָׁוָה)—‘analogy based on identical terms’;

- binyan ʾāb̲ (בִּנְיַן אָב)—‘a general principle derived from a single case’;

- kəlāl ûp̲ərāṭ (כְּלָל וּפְרָט)—‘a general statement followed by a specific one’;

- pərāṭ ûk̲əlāl (פְּרָט וּכְלָל)—‘a specific statement followed by a general one’;

- kayyôṣēʾ bô bəmāqôm ʾaḥēr (כַּיּוֹצֵא בּוֹ בְּמָקוֹם אַחֵר)—‘an analogous case found elsewhere’;

- dāb̲ār halômēd̲ mēʿinyānô (דָּבָר הַלוֹמֵד מֵעִנְיָנוֹ)—‘a rule derived from context’.

Hillel’s middôt laid the foundation for the later evolution of Judaic hermeneutics, particularly as scholars expanded, refined, and systematized these rules. Over time, later sages, such as Rabbi Ishmael and Rabbi Akiva, built upon Hillel’s principles, developing more complex methods of interpretation to address various legal and theological questions.

The only relative of Hillel explicitly mentioned in Rabbinic sources is his brother, Šeb̲nāʾ (שֶׁבְנָא) (Sôṭāh 21a), who was a merchant involved in international trade. Considering the context of Akkadian and Aramaic texts from the Judean diaspora, this implies that their family was well-integrated into Mesopotamian society while retaining a middle-tier social status. Additionally, Hillel’s background implies that he, like his brother, was familiar with Babylonian legal traditions and methods of textual interpretation, an essential skill for conducting business in an environment governed by sophisticated legal contexts. The influence of Mesopotamian legal hermeneutics, particularly methods of reasoning and contractual interpretation, may have shaped Hillel’s approach to Jewish law. Babylonian legal texts from the Neo-Babylonian and Achaemenid periods exhibit patterns of analogical reasoning, conditional clauses, and structured exegesis that parallel aspects of Rabbinic interpretation. This suggests that Hillel’s legal methodology was not formed in isolation but was, at least in part, a product of the broader Babylonian intellectual and legal milieu.

According to the Sip̲rê dəb̲ārîm (357), Hillel’s life follows a pattern similar to that of Moses: both lived for 120 years, divided into three distinct stages. Hillel arrived in Judea at the age of forty, dedicated the next forty years to study, and spent his final forty years as the spiritual leader of Israel. His teachings, which promoted a more lenient and inclusive approach to Jewish law, often stood in contrast to those of his contemporary, Šammaʾi (שַׁמַּאי, 50 BCE–30 CE). Hillel emphasized the value of peace, humility, and the importance of understanding one’s duties toward both God and fellow human beings.

Neḥunya ben Ha-Qanah (נְחוּנְיָא בֶּן הַקָּנָה, 1st century CE), a disciple of Hillel, further advanced his teacher’s hermeneutic approach. According to Yoḥanan bar Nappaḥa (יוֹחָנָן בַּר נַפָּחָא, 279–180 CE) (Šəb̲ûʿôt̲ 26a), Neḥunya consistently applied the interpretative method of ‘general and particular’ (kəlāl ûp̲ərāṭ, כְּלָל וּפְרָט) to the Torah, demonstrating his commitment to Hillel’s exegetical framework. His methodology was later systematized by his student, Rabbi Ishmael (רַבִּי יִשְׁמָעֵאל, c. 70–135 CE), who incorporated it as the eighth of his thirteen foundational hermeneutic principles for interpreting Jewish law. As mentioned in the Ḥullin (129b), Neḥunya participated in a halakhic debate with two other leading scholars of his time, Eliezer ben Hurqanus (אֵלִיעֶזֶר בֶּן הוּרְקָנוֹס, c. 45–117 CE) and Yehošua ben Ḥananyah (יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בֶּן חֲנַנְיָה, c. 50–131 CE). These discussions illustrate his influence in shaping legal discourse and his role in the dynamic development of Rabbinic law.

Neḥunya’s disciple, Rabbi Ishmael, systematized and expanded upon the hermeneutic principles, developing a framework of thirteen rules (middôt) in his Bārayt̲āʾ dərabbî Yišmāʿēʾl that became a cornerstone of halakhic exegesis. While largely maintaining Hillel’s framework, Rabbi Ishmael renamed two principles:

- binyan ʾāb̲ (בִּנְיַן אָב) became binyan ʾāb̲ mikkāt̲ûb̲ ʾeḥād̲ (בִּנְיַן אָב מִכָּתוּב אֶחָד) (‘a prototype based on a single passage’);

- kayyôṣēʾ bô bəmāqôm ʾaḥēr (כַּיּוֹצֵא בּוֹ בְּמָקוֹם אַחֵר) became binyan ʾāb̲ miššənê kət̲ûb̲îm (בִּנְיַן אָב מִשְּׁנֵי כְּתוּבִים) (‘a prototype based on two passages’).

The thirteen rules of Rabbi Ishmael provided a structured methodology for deriving legal rulings from the Torah, addressing textual ambiguities, reconciling contradictions, and uncovering deeper meanings embedded in the scriptural text (Schumann 2023b). This system of interpretation became a defining feature of Rabbinic literature and remains fundamental to Jewish legal thought to this day.

It is known that Ishmael descended from a wealthy priestly family in Upper Galilee (Tôsep̲tāʾ, Ḥallāh I:10; Bāb̲āʾ Qammāʾ 80a). He was taken by the Romans in his youth but was freed through the efforts of Yehošua ben Ḥananyah, becoming a scholar upon returning to Israel (Tôsep̲tāʾ, Hôrāyôt̲ II: 5; Giṭṭîn 58a). Although Neḥunya ben ha-Qanah is named as one of his teachers (Šəb̲ûʿôt̲ 26a), Ishmael’s close bond with Yehošua ben Ḥananyah, who called him ‘brother’, was also central to his education (ʿĂb̲ôd̲āh Zārāh II: 5; Tôsep̲tāʾ, Pārāh, X: 3).

In addition to Neḥunya ben Ha-Qanah, another prominent disciple of Hillel was Rabban Gamliel I (גַּמְלִיאֵל, 1st century CE). His leading students, Rabbi Eliezer ben Hurqanus and Rabbi Yehošua ben Ḥananyah, later became the primary mentors of Rabbi Akiva (רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא, c. 50–135 CE), who further expanded Hillel’s hermeneutic principles, developing them alongside the contributions of Rabbi Neḥunya and Rabbi Ishmael. Rabbi Akiva, like Hillel, began studying the Torah at age 40 under Eliezer ben Hurqanus and became one of the most prominent rabbis of his time, establishing his school in Bnei Brak (Bene Beraq) near Jaffa (Sanhed̲rîn 32b). He is also known for his association with the Bar Kokhba revolt (Yərûšalmî Taʿănît̲ IV: 68d).

Rabbi Akiva had a profound impact on Halakha and hermeneutics, playing a key role in organizing Jewish law and advancing Rabbinic exegesis into a structured and dynamic discipline. He occasionally debated with Rabbi Ishmael (Sanhed̲rîn 51b), highlighting their intellectual exchange. While Ishmael favored a more structured and logical approach, Akiva adopted a broader and more interpretative method of legal inference, focusing on the significance of every word, letter, and grammatical structure in the Biblical text. His method emphasized that no part of Scripture was superfluous, allowing for broader interpretations and additional laws to be derived from even minor textual variations. These interpretative methods became essential tools for Talmudic scholars, enabling them to apply Torah law to new circumstances while maintaining continuity with tradition. The development of Rabbinic hermeneutics also influenced the structure of the mid̲rāš (מִדְרָשׁ), a genre of Rabbinic literature that provides explanations and interpretations of Biblical texts.

Rabbi Eliezer ben Rabbi Yose ha-Glili (רַבִּי אֶלִיעֶזֶר בֶּן רַבִּי יוֹסֵי הַגְּלִילִי; 2nd century), a disciple of Rabbi Akiva and a fourth-generation Tannāʾ (Bərāk̲ôt̲ 63b), contributed to the further development of Rabbinic hermeneutics by establishing an additional set of interpretative methods, encapsulated in his Barayta of the Thirty-Two Rules, shaping the study of the Scriptures by offering a structured approach to interpretation, blending syntactical, phraseological, and other textual peculiarities. He was renowned for his contributions to hermeneutic rules used in both Halakhah and Haggadah. Later scholars praised his homiletical interpretations (Ḥullîn 89a; Yərûšalmî Qiddûšîn 1:61d), which were mainly applied in Haggadah. But even in Halakhah, he relied on exegesis, emphasizing strict adherence to the law and rejecting judicial compromise (Tôsep̲tāʾ Sanhed̲rîn 1:2; Sanhed̲rîn 6b; Yərûšalmî Sanhed̲rîn 1:18b).

Hence, Hillel’s contributions to Judaic hermeneutics established a structured approach to interpreting sacred texts, and his legacy gave rise to two distinct but complementary traditions:

- The tradition of Neḥunya ben Ha-Qanah and Rabbi Ishmael—this school of thought emphasized a logical and structured approach to legal exegesis, focusing on general principles and their specific applications. Rabbi Ishmael formalized this method in his thirteen hermeneutic rules, which became essential for halakhic interpretation.

- The tradition of Rabbi Akiva and Rabbi Eliezer ben Rabbi Yose ha-Glili—this approach was more expansive, seeking to extract meaning from every detail of the Biblical text, including a repetition of some words. Rabbi Eliezer systematized this approach into thirty-two hermeneutic rules, which are fundamental for deriving the haggadic meaning from studied texts.

Despite their differences, both traditions played crucial roles in shaping Rabbinic jurisprudence, laying the groundwork for later Talmudic scholarship. Over time, their methodologies were synthesized and refined by later sages, contributing to the dynamic and evolving nature of Jewish legal and exegetical thought.

Hillel, after ascending from Babylon to Judea, established one of the earliest Rabbinic academies in Jerusalem. His school became a cornerstone of Jewish learning and legal interpretation, forming the foundation of Talmudic hermeneutics. This institution flourished during the late Second Temple period, attracting scholars and disciples who would later play pivotal roles in the transmission and development of Jewish law.

Following the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, Jewish scholarship faced a crisis, necessitating a new center for legal and religious study. Rabban Yoḥanan ben Zakkai (יוֹחָנָן בֶּן זַכַּאי; 1st century CE), recognizing the urgency of preserving Rabbinic tradition, secured permission from the Roman authorities to establish an academy in Yavne (Jamnia)—see Giṭṭîn 56a. This academy became the intellectual and spiritual heart of post-Temple Judaism, where sages engaged in critical discussions that ultimately laid the groundwork for the Mishnah. This academy was a residence of Rabbi Ishmael. Another important center of Rabbinic learning emerged in Lydda (Lod), where prominent scholars such as Rabbi Eliezer ben Hyrcanus (אֵלִיעֶזֶר בֶּן הוּרְקָנוֹס; 1st–2nd century CE) and Rabbi Akiva taught.

During the Judean wars, Rabbinic academies were disrupted, and Jewish teaching was preserved by being transmitted to Babylonia. There, among others, two major Rabbinic academies were established: Pumbeditha and Sura. The Pumbeditha Academy, founded by Judah bar Ezekiel in the middle of the third century CE, became one of the most influential centers of Jewish learning, operating for nearly 800 years. It was known for its analytical approach to Talmudic study, emphasizing logical reasoning and dialectical discussion, which played a key role in shaping Jewish law. Similarly, the Sura Academy, founded in c. 220 CE by Abba Arikha (Rav), was another major center of Jewish scholarship. Located in southern Babylonia, it focused on the textual study of the Talmud and produced some of the most distinguished Jewish scholars, including Rav Huna, Rav Ḥisda, Rav Ashi, Yehudai ben Naḥman, Natronai ben Hilai, and Saadia Gaon. These sages contributed significantly to the compilation and interpretation of the Talmud, influencing Jewish law and tradition across the diaspora.

Hillel is often considered the founder of logical hermeneutic rules (middôt) in Judaism, as he is mentioned in the Talmud as the first Tannāʾ to formulate these principles systematically. However, there is evidence that similar interpretative methods existed in Judaism long before Hillel. For example, the New Testament frequently applies these rules in various forms of reasoning, indicating their widespread use in Jewish thought during the first century CE—something that would only be possible if this hermeneutic tradition had already been well-established for a long time.

One of the key hermeneutic rules, qal wāḥōmer (a fortiori argument), appears in Jesus’ teachings very often. A notable instance occurs when Jesus responds to the Pharisees’ objection to healing on the Sabbath. He employs qal wāḥōmer by pointing out that circumcision is permitted on the Sabbath, so restoring a person’s health should be even more permissible:

ᵓen barnāšā meṯgəzar bəyawmā dəšabbəṯā meṭṭul dəlā neštəre nāmūsā dəmūše ᶜəlay rāṭnīn ᵓətton dəḵullēh barnāšā ᵓaḥləmeṯ bəyawmā dəšabbəṯā.(Peshitta, John 7:23)

ᵓn br ᵓnš mtgzr bywmᵓ dšbtᵓ mṭl dlᵓ nštrᵓ nmwsᵓ dmwšᵓ by ḥyrb ᵓntwn dklh br ᵓnšᵓ ᵓḥlmt bywmᵓ dšbtᵓ.(Old Syriac Sinaitic Palimpsest, John 7:23)

“So if a man is circumcised on the Sabbath day, that the law of Moses may not be broken; yet you murmur at me, because I healed a whole man on the Sabbath day?”.(tr. G. Lamsa)

The phrase ‘healing a whole man’ can be understood broadly, not only as physical healing but as restoring wholeness. In this qal wāḥōmer, the minor premise (circumcision on the Sabbath) and the major premise (healing on the Sabbath) must belong to the same category. In this case, both are medical procedures performed on the Sabbath, reinforcing the argument that healing is permissible.

Another example of Jesus using Judaic hermeneutic principles appears in John 10:11:

ᵓennā nā rāᶜyā ṭāḇā rāᶜyā ṭāḇā napšēh sāem ḥəlāp ᶜānēh.(Peshitta, John 10:11)

ᵓnᵓ ᵓnᵓ rᶜyᵓ ṭbᵓ wrᶜyᵓ ṭbᵓ yhb npšh ᶜl ᵓpy ᶜnh.(Old Syriac Sinaitic Palimpsest, John 7:23)

“I am the good shepherd; a good shepherd risks his life for the sake of his sheep”.(tr. G. Lamsa)

This statement about rāᶜyā suggests a connection to Isaiah 40:11, where God is depicted as a shepherd (ּרֹעֶה֙; rōʿeh). This type of reasoning follows the rule of gəzērāh šāwāh, which links similar phrases in different scriptural passages to derive meaning.

Paul’s writings, as well as the writings of other Apostles, also demonstrate the use of qal wāḥōmer and other examples of Hillel’s principles. In his letter to the Romans, he argues that if God showed love by sending the Messiah to die for sinners (the minor premise), then He will surely continue to show love to believers (the major premise):

hārkā məḥawe ᵓălāhā ḥūbbēh dalwāṯan den kaḏ ḥaṭāye ᵓīṯayn wayn məšīḥā ḥəlāpayn mīṯ

kəmā hāḵīl yattīrāyīṯ nezdaddaq hāšā baḏmēh wəḇēh neṯpaṣṣe men rūgzā

ᵓen gēr kaḏ ᵓīṯayn bəᶜeldəḇāḇe ᵓeṯraᶜī ᶜamman ᵓălāhā bəmawtā daḇrēh kəmā hāḵīl yattīrāyīṯ bəṯarᶜūṯēh nīḥe bəḥayaw.(Peshitta, Romans 5:8–10)

“God has here manifested his love toward us, in that, while we were yet sinners, Christ died for us. Much more then, being justified by his blood, we shall be delivered from wrath through him. For if when we were enemies, we were reconciled to God by the death of his Son, much more [kəmā hāḵīl], being reconciled, we shall be saved by his life”.(tr. G. Lamsa)

These examples indicate that the rules ascribed to Hillel in the Talmud were part of a broader Jewish interpretative tradition, influencing not only Rabbinic exegesis of Tannāʾîm but also the reasoning found in early Christian texts.

The fact that the New Testament extensively employs a family of Judaic hermeneutic rules suggests that these methods were an essential part of Jewish discourse and religious instruction in the first century CE. This indicates that such interpretative traditions had already been deeply embedded in Jewish thought long before the formalization of Rabbinic hermeneutics by Hillel. Consequently, it is reasonable to infer that some form of Judaic (pre-Rabbinic) academies existed well before Hillel. Therefore, we can assume that Hillel received a good Judaic education in Babylonia in one of the academies, although the Talmud states that he studied after moving to Jerusalem at the age of 40. One possible location for such early academies is Āl-Yahūdu, a Jewish settlement in Babylonia dating back to the exilic period. The existence of a well-organized Jewish community there suggests an environment conducive to scholarly learning. Ezra, who played a pivotal role in re-establishing Torah study in Judah, may have received his education in such a setting, preparing him to lead religious and legal reforms upon his return to Jerusalem.

4. Judaic Hermeneutic Principles in the Framework of Greco-Roman Rhetoric

Each of the Judaic hermeneutic rules (middôt) can find counterparts in Greek and Roman rhetoric, particularly within the structures of reasoning that were foundational to persuasive discourse in these traditions. While the specific terminology may differ between the Judaic and Greco-Roman traditions, the underlying logical techniques, such as analogical reasoning, deduction, induction, and the application of precedent and context, are central to both the interpretative methods of Jewish scholars, such as those of Hillel, Rabbi Ishmael, and Rabbi Eliezer ben Yose, and the rhetorical strategies employed by classical orators and philosophers. This cross-cultural similarity underscores the shared emphasis on structured argumentation, demonstrating how both the Jewish tradition and the Greco-Roman world highly valued logical reasoning as a means of persuasion and interpretation.

One of the most notable parallels can be observed in the Judaic principle of qal wāḥōmer (קַל וָחֹמֶר, ‘light and heavy’), which is analogous to the Greco-Roman a fortiori argument. The logical meaning of a fortiori is that if a particular rule or principle applies in a less significant case, it should certainly apply in a more significant one, and vice versa. This mirrors Aristotle’s articulation of reasoning based on inference ‘from the more and less’ (μᾶλλον καὶ ἧττον), which he describes in his Rhetorica:

Oἷον “εἰ μηδ᾽ οἱ θεοὶ πάντα ἴσασιν, σχολῇ οἵ γε ἄνθρωποι”: τοῦτο γάρ ἐστιν “εἰ ᾧ μᾶλλον ἂν ὑπάρχοι μὴ ὑπάρχει, δῆλον ὅτι οὐδ᾽ ᾧ ἧττον”.(Aristot. Rh. II.23.4)

“For example, “If even the gods do not know everything, then surely humans do not either”. For this means: “If that to which something would more likely belong does not possess it, then clearly that to which it would belong less does not possess it either”.”

The a fortiori argument, widely applied in Roman legal reasoning, also finds expression in the Topica of Marcus Tullius Cicero (106–43 BCE), where he explains the principle of reasoning by comparison:

Ex comparatione autem omnia valent quae sunt huius modi: Quod in re maiore valet valeat in re minore, ut si in urbe fines non reguntur, nec aqua in urbe arceatur. Item contra: Quod in minore valet, valeat in maiore. Licet idem exemplum convertere. Item: Quod in re pari valet, valeat in hac quae par est; ut: Quoniam usus auctoritas fundi biennium est, sit etiam aedium.(Cic. Top. IV.23)

“By comparison, however, all things are valid which are of this kind: What is valid in a greater thing is valid in a lesser thing, as if the boundaries of a city are not regulated, nor is water in the city blocked. Likewise, on the contrary: What is valid in a lesser thing is valid in a greater thing. It is permissible to reverse the same example. Likewise: What is valid in an equal thing is valid in this which is equal; as: Since the use of the land is authorized for two years, let there also be a building”.

This form of reasoning demonstrates that if a legal leniency is granted for a severe crime (maius), then it should logically be granted for a lesser offense (minus), a principle further explored in Cicero’s De Inventione under the notion of ‘which is greater and which is less’ (quod maius et quod minus). Similarly, Marcus Fabius Quintilianus (c. 35–c. 100 CE), in his Institutio Oratoria, explicitly identifies this as a form of comparative argument (ex comparativis), where a greater case is inferred from a lesser one. He provides an example of such reasoning: ‘If theft is a crime, sacrilege is a greater crime’ (Quint. Inst. V.10.89).

While the a fortiori method is well-documented within Rabbinic exegesis and Greco-Roman rhetoric, its origins can be traced even further back in the ancient Near Eastern tradition. In the Amarna Letters—correspondence from Canaan written in Akkadian—a similar form of reasoning appears with the use of the Akkadian term appūnamma, meaning ‘moreover’ (Rainey 1996). This suggests that such an inferential tool was already in use in the broader ancient Semitic world. Furthermore, qal wāḥōmer reasoning is frequently employed in the Torah itself, sometimes using the Hebrew term ʾap̲ (אַף), which is a cognate of appūnamma. One notable example appears in Deuteronomy 31:27, where Moses employs qal wāḥōmer inference:

“For I know your rebellion and your stiff neck: behold, while I am yet alive with you this day, ye have been rebellious against the Lord; and how much more (ʾap̲) after my death?”.(Deuteronomy 31:27)

Rabbi Eliezer ben Yose distinguishes between two types of qal wāḥōmer reasoning: məp̲ôrāš (מְפוֹרָשׁ) or ‘explicit’ and sāt̲ûm (סָתוּם) or ‘implicit’. The məp̲ôrāš form is one in which the inference is explicitly stated within the text or argument, making the logical connection immediately clear. In contrast, the sāt̲ûm form is implicit, meaning that the conclusion must be inferred rather than directly articulated. This implicit qal wāḥōmer bears a strong resemblance to Aristotle’s concept of the enthymeme (ἐνθύμημα), as discussed in his Rhetorica (I.2).

In addition to qal wāḥōmer, Judaic hermeneutics employs a broad range of analogical reasoning techniques, one of which is gəzērāh šāwāh (גְּזֵרָה שָׁוָה). This method of interpretation draws inferences by identifying identical terms in separate Torah passages, allowing scholars to establish legal or theological connections between different scriptural contexts. A well-known example of gəzērāh šāwāh is the linkage between Samson and Samuel’s vows based on the phrase ‘no razor’ (לֹא-יַעֲלֶה עַל-רֹאשׁוֹ), found in both Numbers 6:5 and Judges 13:5. By recognizing the recurrence of this phrase, Rabbinic interpretation infers a shared Nazirite status between these figures, even though the text does not explicitly state it in Samuel’s case.

This method of reasoning has parallels in Aristotelian dialectics, particularly in what Aristotle defines as παράδειγμα (paradeigma, ‘example’). In the Rhetorica, he describes paradeigma as a form of inductive reasoning that relies on precedent or analogy to establish a persuasive argument. Just as gəzērāh šāwāh links distinct Biblical passages through shared terminology, paradeigma operates by drawing comparisons between similar cases, often using historical examples to demonstrate a general principle. Aristotle illustrates this mode of reasoning as follows:

Oἷον ὅτι Δωριεὺς στεφανίτην ἀγῶνα νενίκηκεν: ἱκανὸν γὰρ εἰπεῖν ὅτι Ὀλύμπια νενίκηκεν, τὸ δ᾽ ὅτι στεφανίτης τὰ Ὀλύμπια οὐδὲ δεῖ προσθεῖναι: γιγνώσκουσι γὰρ πάντες.(Aristot. Rh. I.2, 1357a)

“For example, that Dorieus has won a contest with a wreath as a prize: it is sufficient to say that he has won at the Olympic Games, and there is no need to add that the Olympic Games award a wreath, for everyone knows it.”

Here, Aristotle assumes that his audience is already aware of the implicit connection—just as gəzērāh šāwāh assumes that shared terms between passages indicate a deeper, underlying relationship. Both methods function by drawing upon a common cultural or textual knowledge base, allowing the audience to infer conclusions without the need for exhaustive explanation. This type of reasoning closely corresponds to the Roman rhetorical principle of argumentum a simili (argument from similarity), which operates by reasoning from one analogous case to another. In Roman legal and rhetorical traditions, argumentum a simili was employed to extend legal precedents from one situation to another based on shared characteristics. Just as gəzērāh šāwāh and paradeigma rely on recognized similarities to draw conclusions, argumentum a simili functions within the framework of Roman law and oratory to argue that what applies in one known case should also apply in a comparable case.

A form of induction in Judaic reasoning arises from the principle of binyan ʾāb̲ (בִּנְיַן אָב). This is exemplified in Leviticus 17:13: ‘He shall even pour out the blood thereof, and cover it with dust’. The verse suggests that both actions—pouring out the blood and covering it—are governed by the same fundamental principle. Specifically, just as the pouring of blood is performed by hand, so too must the covering be done by hand rather than by foot. Through this reasoning, binyan ʾāb̲ establishes a general rule by recognizing a shared characteristic across different cases. Similarly, Aristotle defines induction (ἐπαγωγή) as the process of deriving universal principles (καθόλου) from specific observations (καθ’ ἕκαστον), as discussed in his Analytica Priora (II.23, 68b15–29) and Topica (VIII.2, 157a25). Likewise, in Roman rhetoric, Cicero’s concept of induction (inductio) follows the same logical progression, moving from particular cases, such as the unreliability of guardians and trustees, to establish a broader general principle regarding untrustworthiness in fiduciary roles.

Hence, in Judaic hermeneutics, a fundamental logical distinction is made between kəlāl (כְּלָל), genus (‘general’), and p̲ərāṭ (ּפְרָט), species (‘particular’). However, while Aristotle developed syllogistic reasoning—a formal system in which conclusions necessarily follow from major and minor premises—Judaic scholars emphasize a structured sequence of general and particular notions to derive meaning from texts. This structured approach is evident in the hermeneutic principles of pərāṭ ûk̲əlāl (פְּרָט וּכְלָל) and kəlāl ûp̲ərāṭ (כְּלָל וּפְרָט), which govern how general and particular concepts interact within Biblical interpretation. According to pərāṭ ûk̲əlāl, when a general statement follows a particular one, the general term expands the scope of the particular, suggesting that the broader category applies. Conversely, kəlāl ûp̲ərāṭ dictates that when a particular term follows a general one, the interpretation is restricted to the specific case mentioned. For instance, in Leviticus 1:2, the verse states: ‘bring as your offering an animal from either the herd or the flock’. Here, the initial term ‘animal’ is a general category, while ‘herd’ and ‘flock’ provide a specification that excludes undomesticated animals. In this case, the broader term ‘animal’ represents the general notion, whereas ‘herd’ and ‘flock’ serve as particular restrictions that refine the general category. We infer both particulars and ignore the general.

These interpretive rules of pərāṭ ûk̲əlāl and kəlāl ûp̲ərāṭ reflect a nuanced approach to legal and theological reasoning, differing from Aristotelian syllogistics by prioritizing contextual relationships within textual sequences rather than strict deductive structures. This method aligns more closely with the legal hermeneutics found in Roman jurisprudence, where general statutes are interpreted in light of specific cases. Thus, the interplay between the general and particular in Judaic interpretations not only shapes legal exegesis but also parallels broader traditions of logical and rhetorical reasoning.

Judaic hermeneutics emphasizes the importance of context in determining the legal meaning of Torah passages. This principle is encapsulated in Hillel and Rabbi Ishmael’s rule of dāb̲ār halômēd̲ mēʿinyānô (דָּבָר הַלוֹמֵד מֵעִנְיָנוֹ), which translates to ‘a matter is learned from its context’. According to this approach, a verse or legal statement cannot be understood in isolation; rather, its meaning must be derived from the surrounding text, ensuring that interpretations remain consistent with the broader thematic and legal framework of the Torah.

A parallel principle exists in Roman legal tradition, expressed in the maxim: Ex praecedentibus et consequentibus optima fit interpretatio—‘The best interpretation is made from what precedes and what follows’. This guideline reflects a similar commitment to contextual analysis in legal reasoning, where the meaning of a statute or legal clause is determined by considering its placement within a larger textual and legal structure. For example, in Jewish law, the interpretation of ‘an eye for an eye’ (Exodus 21:24) is clarified by its legal context, which discusses monetary compensation rather than literal retaliation. Likewise, in Roman jurisprudence, ambiguous legal terms were often clarified by examining preceding and subsequent clauses within the same statute, ensuring consistency in legal interpretations.

We can also find Greco-Roman counterparts for quite specific rules. For instance, Rabbi Eliezer ben Yose defines rîbûi (רִיבּוּי, ‘extension’) as a method of interpretation that expands the literal meaning of a text, allowing for broader applications beyond the explicit wording. For example, in Deuteronomy 16:3, the phrase ‘all days’ (כָּל יְמֵי) is understood through rîbûi to include not only the daytime but also the nighttime, extending the commandment beyond its apparent scope. A parallel to this hermeneutic principle can be found in classical rhetoric, particularly in Aristotle’s concept of αὔξησις, as discussed in Rhetorica (I.9, 1368a), and in Cicero’s amplificatio (De Inventione I.97). These rhetorical techniques serve to magnify the importance of an idea, often in legal or political discourse. In forensic oratory, for instance, a crime might be ‘amplified’ to highlight its severity, emphasizing its broader moral or societal implications. Cicero’s amplificatio closely aligns with rîbûi in its capacity to extend meaning beyond a term’s strict definition. Just as rîbûi infers a wider application of words in Biblical exegesis (e.g., ‘all days’ implying both day and night), amplificatio enhances the perceived significance of an argument by drawing out its larger ramifications. Both methods employ strategic expansion—whether in legal interpretation or rhetoric—to reinforce a particular understanding or persuasive effect.

The hermeneutic principle of miʿûṭ (מִעוּט), introduced by Rabbi Eliezer ben Yose, means ‘restriction’ or ‘limitation’ and serves to narrow the interpretation of a text by excluding certain possibilities. In its logical function, miʿûṭ corresponds to the Greek concept of διαίρεσις, meaning ‘division’ or ‘restriction’, as discussed in Aristotle’s Topica (I.5, 102a18–25). Both principles operate by distinguishing categories and setting boundaries within reasoning, ensuring that certain interpretations are either refined or explicitly excluded.

Moreover, many more specific hermeneutic methods of Rabbi Eliezer ben Yose have counterparts in Greco-Roman rhetorical techniques. These are not exact equivalents but serve similar functional roles in textual analysis and argumentation, including the following:

- Nôṭārîqôn (נוֹטָרִיקוֹן, ‘acronym-based interpretation’) corresponds to the Greek ἀκρονύμιον (akronymon), which refers to the formation and use of acronyms;

- Dābār šehûʾ šānûi (דָּבָר שֶׁהוּא שָׁנוּי, ‘repeated expression’) aligns with ἀναφορά (anaphora), a rhetorical figure in which a word or phrase is repeated for emphasis;

- Dābār šehûʾ məyuḥād bimqômô (דָּבָר שֶׁהוּא מְיֻחָד בִּמְקוֹמוֹ, ‘rare expressions’) is comparable to ἅπαξ λεγόμενον (hapax legomenon), a term that appears only once in a given text or body of literature;

- Dābār šenneʾĕmar bəmiqṣāt wəhûʾ nôhēg̲ bakkōl (דָּבָר שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר בְּמִקְצָת וְהוּא נוֹהֵג בַּכֹּל, ‘a statement with regard to a part may imply the whole’) corresponds to συνεκδοχή (synekdoche), a rhetorical figure in which a part is used to represent the whole (or vice versa).

- Māšāl (מָשָׁל, ‘allegory’ or ‘parable’) is closely related to παραβολή (parabolē), the Greek term for a parable or illustrative comparison used to convey moral or philosophical lessons.

Thus, while Judaic hermeneutics and Greco-Roman rhetoric share functional similarities, their interpretative frameworks differ in scope and intent. Judaic hermeneutic principles are primarily dedicated to scriptural exegesis, aiming to derive legal and theological insights from the Torah. In contrast, Greek and Roman rhetorical techniques extend to a wider range of applications, including public discourse, ethics, and persuasion. Nevertheless, these parallels underscore a common emphasis on structured reasoning and textual interpretation within the intellectual traditions of the ancient Mediterranean world.

5. Judaic Hermeneutic Principles in the Framework of Indian Reasoning

The rules (middôt) attributed to Hillel, Rabbi Ishmael, and Rabbi Eliezer ben Yose exhibit clear conceptual and methodological parallels with Indian traditions of logic (nyāya), hermeneutics (mīmāṃsā), and poetics (alaṅkāraśāstra). These Jewish and Indian traditions, despite emerging in distinct cultural and historical contexts, share common principles in their approaches to reasoning, interpretation, and textual analysis. In particular, both traditions employ fundamental logical techniques such as analogical reasoning, deduction, induction, precedents, and contextual interpretation. Jewish sages (Tannāʾîm) and Indian scholars (Paṇḍitas) developed these methods within their respective religious, legal, and literary frameworks. For example, in Mīmāṃsā, an interpretation of Vedic texts follows a structured system of reasoning that parallels the hermeneutic rules of the rabbis in the interpretation of the Torah. Similarly, the logical formulations found in Nyāya align closely with Rabbinic methods of argumentation, particularly in their use of structured debate, counterarguments, and inferential reasoning. Even in Alaṅkāraśāstra, where aesthetic considerations dominate, we find systematic frameworks for analyzing rhetorical figures that resemble Jewish midrashic techniques. These parallels suggest that both traditions, despite their geographical separation, were responding to similar intellectual challenges, namely how to derive reliable meaning from authoritative texts, resolve ambiguities, and establish sound reasoning practices.

For example, the qal wāḥōmer reasoning in Rabbinic tradition, known as kaimutika-nyāya in Mīmāṃsā, follows the same logical structure that can be summarized as: ‘What holds in a weaker case (Sanskrit: laghutara; Hebrew: qal) must hold in a stronger case (Sanskrit: gurutara; Hebrew: ḥōmer)’. This form of argumentation is widely used in both hermeneutic traditions to establish a principle by comparing a less expected case with a more expected one. This type of reasoning is commonly found in the commentaries on sacred texts throughout various Hindu schools. One striking example is found in the Ṭīkā commentary of Jīva Gosvāmī (c. 1513–c. 1598) on the Brahma-saṁhitā. Here, he applies kaimutika-nyāya to demonstrate the unparalleled mercy of Śrī Kṛṣṇa:

sa eva ca svayantu vairibhyo’pyanyadurlabhaphalaṃ dadāti kimuta svaviṣayakakāmādinā niṣkāmaśreṣṭhebyaḥ | tataḥ ko vānyo bhajanīya iti?.(Ṭīkā 55)

“That very same Bhagavān personally bestows, even upon His enemies, results that are difficult to attain by others. How much more (kimuta) must He bestow upon those who desire Him—whether they approach Him with love (kāma), or are among the best of the desireless (niṣkāma-śreṣṭha) sages? Therefore, who else is truly worthy of worship?”

In this passage, Jīva Gosvāmī reasons that if Kṛṣṇa is so merciful that He grants even His antagonistic enemies (such as Śiśupāla, Kaṁsa, and Pūtanā) liberation or divine association, then ‘how much more’ (kimuta) must He bestow the highest fruit upon those who worship Him with love and devotion? This argument reinforces Kṛṣṇa’s supreme compassion and the superiority of bhakti (devotional service) over all other spiritual paths. The same logical structure is found in the New Testament, where Paul employs the qal wāḥōmer in Romans 5:8–10 to emphasize divine mercy:

- Smaller/less expected case: Christ died for sinners;

- Larger/more expected case: If He did this for sinners, then ‘how much more’ (kəmā hāḵīl) will He save those who have been reconciled to Him?

Similarly, Jīva Gosvāmī’s argument follows the pattern below:

- Smaller/less expected case: Kṛṣṇa grants liberation or divine association even to His antagonistic enemies;

- Larger/more expected case: If He grants such a high reward even to His enemies, then ‘moreover’ (kaimutika-nyāya), He must bestow an even greater reward upon His pure devotees, who cultivate love and service toward Him.

By employing kaimutika-nyāya, Jīva Gosvāmī not only strengthens the argument that Kṛṣṇa is the most merciful and worthy object of worship, but also highlights the superiority of devotion (bhakti) over all other forms of spiritual practice. The rhetorical power of this reasoning makes it a compelling theological tool, demonstrating that divine grace operates beyond conventional expectations.

The Rabbinic rule qəzērāh šāwāh serves as an analogy based on identical terms. This method links two distinct scriptural texts through a shared term, enabling the derivation of legal or interpretive conclusions. Another logical inference of Judaic hermeneutics based on analogy is called heqqēš (הֶקֵּשׁ). It establishes a connection between two topics appearing in the same verse or passage of the Hebrew Bible. The principle assumes that if two subjects are juxtaposed within a single scriptural context, they must share a common legal or interpretive significance. One classic example appears in Qiddûšîn 2b, where ‘marriage’ is compared to the ‘acquisition of land’ because both appear in proximity in Deuteronomy:

כִּי־יִקַּח אִישׁ אִשָּׁה וּבְעָלָהּ.(Deut. 24:1)

“When a man takes (יִקַּח) a wife and marries her.”

The word ‘takes’ (יִקַּח) is compared to the word used for acquiring property in Genesis 23:13, where the phrase ‘take it from me’ (קַח מִמֶּנִּי) concerns buying a field. This heqqēš forms the basis for the halakhic principle that marriage can be effected through a monetary transaction, just as land is acquired with money. This hermeneutic principle finds a striking parallel in Indian logic (nyāya), particularly in the concept of upamāna (‘comparison’ or ‘analogy’), as presented in Gautama’s Nyāya-sūtra (2nd–4th century CE). The upamāna is defined as follows:

prasiddhasādharmyāt sādhyasādhanam upamānam(Nyāya-sūtra I.1.6)

“A simile (upamāna) is the means of establing the probandum (sādhya) through similarity (sādharmya) to that which is already established (prasiddha).”

This definition underscores the epistemological role of upamāna in reasoning—by drawing upon a known instance (prasiddha), one can infer the properties of an unknown entity (sādhya) through their shared characteristics (sādharmya). This principle closely mirrors heqqēš, where the presence of a common term in two passages serves as the foundation for the same legal reasoning.

Expanding upon this definition, Vātsyāyana’s Nyāya-bhāṣya (4th–5th century CE), a seminal commentary on the Nyāya-sūtra, offers further clarification:

prajñātena sāmānyāt prajñāpanīyasya prajñāpanam upamānam iti | yathā gaur evaṃ gavaya iti.(Vātsyāyana’s Nyāya-bhāṣya on Nyāya-sūtra I.1.6)

“Analogy (upamāna) is the process of making known (prajñāpanam) what is to be made known (prajñāpanīyasya) through a commonality (sāmānya) with what is already known (prajñātena). For example, just as (yathā) [there is] a cow (gauḥ), so (evaṃ) [there is] a gavaya [wild cow].”

Here, upamāna functions as a cognitive tool for extending knowledge. If one knows what a cow (gauḥ) is and is informed that a gavaya resembles it, one can correctly identify a gavaya when encountering it for the first time.

Analogy is also used as an illustration (udāharaṇa) that must accompany any deductive reasoning. This principle is a fundamental feature of both Epicurean and Indian logics. It ensures that an argument is not merely abstract but grounded in observable reality, making the reasoning process more tangible and verifiable. For the first time, Epicurus (341–270 BCE) explicitly formulated this requirement to accompany any deduction with an example, introducing the notion of ‘inference through similarity’ (καθ’ ομοιότητα μετάβασις), also termed ‘analogy’ (αναλογία). This doctrine emphasizes that valid conclusions must be supported by comparisons with prior knowledge, thereby establishing a structured and reliable mode of reasoning (Schumann 2024b). This concept of udāharaṇa or αναλογία, akin to upamāna and heqqēš, affirms that knowledge progresses through analogical reasoning, drawing connections between familiar and unfamiliar elements. Let us take a proposition (pratijñā): ‘The mountain has fire’. Its reason (hetu) is as follows: ‘Because it has smoke’. Its example (udāharaṇa) is: ‘Where there is smoke, there is fire, as in a kitchen’.

In Indian poetics (alaṅkāraśāstra), an analogy sometimes serves as dṛṣṭānta—a powerful literary and rhetorical device, functioning in the same way as māšāl (מָשָׁל), or a ‘parable’, in Hebrew tradition. The dṛṣṭānta is a form of alaṃkāra (rhetorical figure) used to illustrate a principle through comparison. This technique not only enhances poetic beauty but also strengthens argumentation by making abstract concepts more relatable. For instance, in Bhīṣmacarita VI.21, the city of Hastināpurī is metaphorically depicted as a beautiful woman. During a grand celebration, Hastināpurī appears even more dazzling than Amarāvatī, the celestial city of the gods. This leads to an allegorical portrayal where Amarāvatī experiences sorrow and jealousy, much like a woman envious of another woman’s beauty. Here, the poetic device of dṛṣṭānta creates a vivid analogy between the emotional world of human beings and that of divine realms, highlighting the grandeur of Hastināpurī through contrast.

Another form of analogical reasoning in Indian rhetoric is upalakṣaṇa (‘synecdoche’), which corresponds to the Greek συνεκδοχή and the Rabbinic principle of dāb̲ār šenneʾĕmar bəmiqṣāt̲ wəhûʾ nôhēg̲ bakkōl, meaning ‘a statement made about a part may apply to the whole’. This logical technique allows for generalization from a specific case, a common method in both legal and literary traditions. For example, in Rabbinic hermeneutics, a law stated for a particular instance in the Torah can be extended to broader applications, just as in Sanskrit poetics, a single image can symbolize a larger reality.

In the Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika school of Indian philosophy, ‘particularity’ is classified as a distinct ontological category (padārtha) known as viśeṣa, which stands in direct contrast to sāmānya (‘generality’). This dichotomy plays a crucial role in structuring a hierarchy of universals and particulars, relying on both deductive and inductive reasoning. In the Indian system of deduction (nyāya), the emphasis is placed on ‘specific difference’ (lakṣaṇa), a concept that corresponds closely to the Aristotelian notion of differentia specifica (διαφορά ειδοποιός), which defines the distinguishing feature of a species within a genus. Within this framework, an individually unique entity (akin to the Aristotelian ἴδιον/ὑποκείμενον, meaning ‘substrate’) is referred to as svalakṣaṇa. Meanwhile, a ‘general characteristic’ or ‘genus’ (equivalent to the Aristotelian γένος) is categorized as sāmānyalakṣaṇa. This conceptual division underpins syllogistic techniques of deduction, which align with the modus Barbara and modus Camenes of both Aristotelian and Indian logic. Consequently, Indian logic shares a strong similarity with Greek logic in terms of its technical complexity. In turn, these logics are fundamentally different from Rabbinic hermeneutics, where the general principle (כְּלָל, k̲əlāl) and the particular instance (פְּרָט, pərāṭ) do not follow a syllogistic structure.

A form of abductive reasoning in Indian philosophy is exemplified by the Mīmāṃsā technique known as arthāpatti, or ‘presumption’. This method of inference is based on the necessity of an unstated fact to reconcile seemingly contradictory observations. A parallel to this can be found in Rabbinic hermeneutics, specifically in the principle of ʾûmədānāʾ (אוּמְדָּנָא), meaning ‘probabilistic estimation’ (Sanhed̲rîn 78b), and ḥăzāqāh (חֲזָקָה), meaning ‘presumption’ (Mišnāh Giṭṭîn 3:3). A classical example of arthāpatti is: ‘If Devadatta fasts but continues to gain weight, then he must be eating at night’. Here, we have two explicit premises:

- ‘Devadatta does not eat during the day’;

- ‘Devadatta remains fat’.

From these, we necessarily infer that he must be eating at night. Without this presumption, the given premises would contradict the observed reality.

Similarly, in the Talmudic tractate Bābā Batrā (24a), we find a form of abductive reasoning that mirrors the concept of ʾûmədānāʾ and ḥăzāqāh. The passage concerns a case where blood is found in the cervical canal (בַּפְּרוֹזְדוֹר), and there is uncertainty as to whether this blood is menstrual blood or not. The principle of ʾûmədānāʾ and ḥăzāqāh is employed here to make a logical presumption based on common experience. Even though it is uncertain whether the blood in question is menstrual, the Talmud presumes that it most likely comes from the uterus, as the cervical canal is a primary site for menstrual flow. The presumption is made that, given the nature of the blood and its location, it is indeed menstrual blood, and thus it is treated as such for the purposes of ritual purity, even though there might be another possible source of the blood in a different chamber. This reasoning draws on the general knowledge of how menstrual blood flows and the anatomical understanding of the female body, suggesting that it is more likely to have come from the uterus than from the upper chamber, despite the latter being physically closer to the cervical canal. Thus, by employing this abductive reasoning, the Talmud rules that the blood should be treated as menstrual, illustrating the application of ʾûmədānāʾ and ḥăzāqāh as a form of logical presumption.

Like Judaic hermeneutics, Mīmāṃsā interpretation is highly attuned to contextual clarification. In Sanskrit, this interpretive tool is known as prakaraṇa (‘context’), which is used to resolve ambiguities by examining the surrounding textual framework. For example, when determining the validity of an injunction or teaching, factors such as time (kāla), place (deśa), and recipient (pātra) must be considered within the specific context (prakaraṇa) of the passage. If the context is not explicitly stated, reasoning must be applied to deduce the intended meaning. However, it is worth noting that while Mīmāṃsā uses prakaraṇa for Brahmanic ritual injunctions, Judaic contextuality extends to law.

As we already know from the previous section, analogies between Judaic reasoning techniques and Greco-Roman rhetoric can be found not only in structural methods but also in underlying principles, revealing a shared intellectual heritage. Similarly, Indian reasoning, particularly in classical philosophy, aligns with certain Talmudic rules and practices. For instance, rare expressions, such as dāb̲ār šehûʾ məyuḥād̲ bimqômô in Hebrew and ἅπαξ λεγόμενον in Greek, reflect a common interest in language’s exceptional or unique usage, which is studied for its specific, often metaphorical, implications. This parallels the Indian concept of alpaprayoga, where a word’s usage in limited or rare contexts is analyzed for its deeper, nuanced meaning, emphasizing aesthetic novelty. Furthermore, the Jewish tradition of Gematria, where numerical values of letters are used to derive meaning, finds a parallel in Indian reasoning through aṅkaśāstra—although in Indian tradition, aṅkaśāstra primarily refers to numerology and sacred numbers in a broader cosmological sense, sometimes specifically applied to diagrammatic representations (such as yantras) in tantric practices, rather than strictly textual exegesis.

To sum up, the parallels between Jewish, Greco-Roman, and Indian intellectual traditions are not coincidental but reflect a deeper interconnectedness between them. They reveal how different cultures, despite their geographical and cultural distinctions, developed similar logical and rhetorical frameworks to explore meaning, language, and knowledge. This underscores the universality of certain intellectual principles across these three ancient traditions.

Thus, when examining the intellectual traditions of Judaic, Greco-Roman, and Indian cultures, we encounter deep functional parallels that demonstrate striking similarities in their methods of reasoning. These parallels suggest that, despite differences in linguistic, cultural, and historical contexts, the underlying cognitive processes across these traditions are closely aligned. However, to fully appreciate these connections, it is essential to recognize that the frameworks within which these reasoning methods operate—namely, the literary, ritual, and exegetical contexts—differ significantly between these cultures. In the Jewish tradition, for instance, much of the reasoning takes place within a religiously structured framework that emphasizes the interpretation of sacred texts (the Torah, Talmud, etc.), as well as the ritual observance of commandments (miṣwôt). Jewish exegesis, particularly in the Talmudic tradition, is steeped in a mix of legal and moral reasoning, supported by an intricate system of dialectical argumentation. In Greco-Roman traditions, particularly in philosophy and rhetoric, reasoning often operates within a literary context that is more focused on argumentative structures, political debates, and the quest for universal truths. Indian traditions, especially in classical philosophy and logic, such as that of Nyāya and Mīmāṃsā, also emphasize a formalized framework for reasoning, but it operates within a more metaphysical and cosmological context, often intertwined with rituals and spiritual practices. Despite these differences in cultural frameworks, the reasoning schemas in each tradition, such as the use of analogical inference, deductive, inductive, and abductive reasoning, and the application of metaphor, are strikingly similar. This suggests that these diverse traditions, while separate in their approach and context, share a common intellectual heritage in their methods of logical thought. We will say that they have the same logemes—units of reasoning.

6. Judaic Hermeneutic Principles in the Framework of Chinese Philosophy

The logemes of Judaic, Greco-Roman, and Indian thought may also be found echoed within Chinese classical philosophy, pointing to a shared undercurrent of logical reasoning across Eurasia. A particularly striking example lies in the parallel between the qal wāḥōmer (a fortiori reasoning) of Rabbinic hermeneutics and the tuī lèi (推类, ‘extend a class [by analogy]’) of classical Chinese philosophy. Structurally, both follow the same inferential mood: (1) minor premise: ‘If a lesser case is true;’ (2) major premise: ‘Then a greater case is certainly true’. In both traditions, the inference by analogy hinges on a proportional relationship between cases, where a judgment or principle valid in one instance necessarily applies to another with greater reason. In Chinese philosophy, this tuī lèi was a central method of knowledge extension, especially emphasized in Mohist reasoning. The Mòjīng (《墨經》, Mohist Canons, 4th–3rd century BCE) codifies this approach:

「以類取, 以類予。」

Yǐ lèi qǔ, yǐ lèi yǔ.(小取, Minor Illustrations 1)

“Take by classes [through analogy]; give by classes [through analogy].”

Here, ‘take by classes [through analogy]’ (以類取) refers to the inductive process of deriving general principles by observing similarities among things. ‘Give by classes [through analogy]’ (以類予) refers to the deductive or projective application of those principles to new, unobserved, or broader contexts. This logical motion—from known to unknown, from concrete cases to normative generalizations—formed the basis of early Chinese reasoning on law, morality, and governance. A typical example might go: ‘If a law against theft applies to a commoner (lesser case), it must apply even more to a ruler (greater case), since the ruler’s moral responsibility is greater’. While this may echo the qal wāḥōmer in form, its purpose in the Chinese context diverges. In contrast to Rabbinic hermeneutics, where qal wāḥōmer is primarily employed for textual exegesis—interpreting divine law within the Torah—the Chinese use of tuī lèi functions chiefly in ethical and political reasoning. This practical orientation aligns more closely with its application in the writings of Paul (e.g., Romans 5:8–10) and in vaiṣṇava commentaries such as Jīva Gosvāmī’s Ṭīkā 55, where analogical reasoning a fortiori supports moral and theological argumentation beyond mere textual interpretation. Thus, much like in Early Christianity and Vaiṣṇavism, Chinese philosophy employed this analogical method to advance foundational principles such as universal ethics (兼愛 jiān ài, ‘impartial care’), social justice, and the harmonization of legal and moral standards.