1. Introduction

Daoist ritual garments function as a material medium through which the body enters into dialogue with the cosmos, profoundly embodying the philosophical wisdom of “Dao follows nature”. Under the cosmological vision of “unity of heaven and humanity” (天人合一), the practitioner employs attire as an interface of the body to transform abstract doctrines of cosmic genesis into concrete practices of cultivation. In this process, Daoist costume reveals extraordinary interpretive value: it is neither a mere marker of social identity nor a simple visual translation of abstract doctrine; rather, through the symbolic weaving of material, color, and pattern, it converts the body into an operative “Way-body” interface. The uniqueness of this “wearable cosmology” lies in the dynamic co-construction of its material attributes and spiritual dimensions, which both adhere to the hierarchical logic of “Human follows the earth, the earth follows heaven” (人法地,地法天) (

Laozi 2011, p. 66) and, through ritual practice, continually reconstruct a network of symbolic meanings.

Existing studies that reveal the philosophical connotations of Daoist dress exhibit three theoretical lacunae. The first is the divide between materiality and spirituality; much existing scholarship focuses on shape type and formulation (

Xia et al. 2018) or institutional evolution (

Lin 2004), clarifying historical trajectories yet failing to address the ontological question of how ramie comes to bear the Way. The second is the staticization of the semiotic system; even scholars who touch upon the ritual functions of ritual robes (

Lagerwey 2010;

Dong 2021) treat the Five-Element color spectrum and astral patterns as fixed codes, overlooking their dynamic recomposition within ritual contexts. The third is the absence of the embodied dimension; although

Zhou (

2024) offers valuable semiotic decoding, he stops short of linking attire with practitioners’ lived embodied experiences and thus cannot account for the lived wisdom of garment as practice. Together, these limitations point to the core dilemma in the study of religious material culture: how to transcend a form–function binary and capture the symbiotic mechanisms of materiality and divinity within their historical contexts.

This study takes the Daodejing’s principle of the Way accords with nature as its theoretical core to construct a three-dimensional interpretive model of material–symbol–phenomenon, inaugurating a new paradigm in religious art research. This framework integrates

Appadurai’s (

1988) theory of materiality and meaning, exploring the resonance between the ramie growth cycle and cultivation ethics;

Cassirer’s (

2023) philosophy of symbolic forms as cognitive mediators, decoding the transformation of the Five-Element spectrum within power struggles; and

Merleau-Ponty et al.’s (

2013) phenomenological perspective of embodiment, revealing the coordination between robe structure and the steps of the gang-bu ritual. Through these three theoretical lenses, this study proposes the concept of the “natural halo”, distinguishing Daoist vestments from the glorious divinity of Christian vestments (

MacDonald 2016;

Naydler 1996) and the dependent origination of Buddhist monastic robes (

Kieschnick 1999). Daoist attire, by means of an aesthetics of imperfection (e.g., the serendipitous results of tie dye techniques), dynamic coding (e.g., semantic contests within the imperial purple robe system), and spatiotemporal narrative (e.g., the orientation-regulating function of Big Dipper motifs), constructs a unique cultivation interface.

To break from the traditional static form–function analytical model, this research adopts a multi-evidential cross-verification approach. First, it conducts exegeses of Daoist canon

1 texts such as the

Yunji Qiqian (云笈七签,Cloud Scriptures) and the

Dongxuan Lingbao Sandong Fengdao Kejie Yingshi (洞玄灵宝三洞奉道科戒营始, Codex of Ritual Regulations for the Three Caverns) to analyze the implicit norms and energy-coding systems embedded in costume regulations. Second, it employs iconographic methods to study astral and Bagua patterns on Daoist robes in the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum, revealing their spatial narrative logic. Finally, it combines semiotics and theories of embodied practice to deconstruct how costume elements function as a symbolic system of cultivation interfaces. This interdisciplinary methodology not only bridges the gap between material culture and spiritual symbolism but, through threefold evidential triangulation, dynamically presents the process of meaning-generation in Daoist attire within its historical contexts.

The theoretical contributions of this study are threefold. First, it is the first to construct a three-dimensional interpretive model grounded in the concept of the Way accords with nature, thereby facilitating a theoretical dialogue between Daoist philosophy and contemporary semiotics and phenomenology. Second, by examining categories such as material tension, chromatic duality, and spatiotemporal patterning, it systematically reveals the dynamic characteristics of Daoist robe symbolism. Third, it introduces the concept of a dynamic cultivation interface, offering a novel analytical paradigm for the study of religious material culture. These innovations deepen theoretical discussions of the agency of things (

Gell 1998) and contribute a Chinese perspective to cross-cultural research on the body as cultivation interface (

Kohn 2008), with significant implications for sustainable design and embodied aesthetics.

2. The Philosophical Foundation of Daoist Clothing in Accordance with the Principle of “Dao2 Follows Nature”

The formation logic of Daoist clothing is deeply rooted in the core philosophy of “Dao follows nature” (道法自然). Daoism’s concept of “Dao follows nature” not only emphasizes emulating the natural laws of heaven and earth but also reveals the dialectical relationship between “nature” and “human intervention”. As the “second skin” of the human body, clothing, in its design and use, should conform to the inherent properties of its materials while simultaneously embodying the spiritual ideal of the practitioner to “align with Dao”. This section explores how Daoist clothing, in terms of materials, the body, and the cosmos, specifically presents the philosophy of nature, based on the progressive logic found in the

Daodejing (道德经): “Human follows the earth, the earth follows heaven, heaven follows the Dao, and the Dao follows nature” (人法地,地法天,天法道,道法自然) (

Laozi 2011, p. 66).

2.1. The Dual Dimensions of the Concept of Nature: From “Emulating Nature” to “Returning to Simplicity”

In Daoist thought, the concept of “nature” has both ontological and methodological meanings: it refers to the constant laws governing the operation of all things in the universe and embodies primal authenticity that is unrefined. This duality is evident in material selection for Daoist clothing. For example, plant fibers like ramie and hemp, due to their breathability and durability, are widely used. This choice not only aligns with the natural properties of the material but also carries the symbolic meaning of “earthly garments and heavenly robes”. As noted in the

Baopuzi (抱朴子): “Practitioners replace elaborate official robes with coarse cloth and use wild vegetables (such as bracken and purslane) instead of refined meals” (被褐代衮衣,薇藿当嘉膳) (

Ge 2011, p. 261). This suggests that material choices are not solely for practical purposes but also encapsulate the cultivation of unity between body and mind through attunement with natural energies. Conversely, silk, derived from “heavenly silk” (silk from silkworms), is imbued with a spiritual quality of “connecting to heaven” and is often used in the ceremonial robes of high-ranking Daoist priests. The

Sandong fafu kerongwen (三洞法服科戒文, Codex of Ritual Attire in the Three Caverns) states that “The Daoist priest of the Perfect Dao wears a purple gauze robe, lined with azure, the hem flowing gracefully” (褐帔用紫纱,以青为裹,飞清华裙) (DZ788, 5a). The attention to the material and texture here metaphorically alludes to the practitioner’s ultimate transcendent state of immortality.

Additionally, the plainness of unprocessed hemp symbolizes a critique of the alienation of civilization. As stated in

Zhuangzi (庄子), “Only by following the Great Dao can one possess complete virtue; external behavior will then align with natural laws; the spirit will attain clarity and focus” (执道者德全,德全者形全,形全者神) (

Zhuangzi 2019, p. 195). This philosophy emphasizes that by returning to the Great Dao and returning to simplicity, practitioners use the rough texture of their clothing as a practice of “shedding false adornments and returning to authenticity”. Through this practice, their external behavior and spiritual state align with the natural order. Daoist practitioners, through the primitive texture of their clothing, aim to awaken their inner spirituality, embodying the aesthetic practice of “emulating nature”.

2.2. The Mediatory Concept of the Body: Clothing as the Interface for “Heaven and Human Unity”

Daoist views on the body differ from the Western dualism of “spirit and flesh”. Daoism constructs a triune cultivation model of “form—qi—spirit” (形—气—神).

The Huainanzi (淮南子) states that “The body is the foundation of life, qi is the driving force of vital activity, and spirit (shen) is the sovereign of life. Only when these three elements are in harmonious unity can life function properly” (形者生之舍也;气者生之充也;神者生之制也。) (

Liu 2017, p. 38). This underscores the interdependence and significance of form, qi, and spirit in sustaining life. In this system, clothing is not merely a cover for the body; it is a mediatory tool that regulates the body and spirit, achieving the “unity of heaven and humanity” (天人合一). According to the

Yaoxiu Keyi Jielü Chao(要修科仪戒律钞), “The width of the Daoist ritual robe

pei is four chi and nine cun, corresponding to the seasonal changes of the year; its length is five chi and five cun, symbolizing the harmonious resonance of qi between Heaven and Earth” (四极明科曰:帔令广四尺九寸以应四时之数;长五尺五寸,以法天地之气) (DZ463, 2b–3a). According to Daoist thought, the human body is seen as part of nature and is inseparably linked to it (

Jung and Kan 2019;

Kohn 1991). The human body is regarded as a vessel for “Qi” (气

3), and the design of clothing (such as wide-sleeved robes and the ten-holed design of Daoist shoes) follows the principle of ensuring the free flow of “qi”. As stated in the

Huangdi neijing (黄帝内经) and

Zunsheng bajian (遵生八笺), clothing that is too tight can obstruct the flow of “qi”, while loose clothing helps align with the seasonal energies, reflecting Daoist wisdom for health and longevity. The design of Daoist clothing is always based on the principle of facilitating the flow of “qi”.

Furthermore, the “dust-blocking” function of Daoist robes reflects the Daoist dialectic of “concealment and revelation”. As noted in Ziyang zhenren wuzhenpian zhushu (紫阳真人悟真篇注疏, Commentary on the Awakening to Truth by Perfected Ziyang), “Dao itself is hidden and nameless, and its true essence must be revealed through concrete symbols and metaphors” (道本无名,圣人强名;道本无言,圣人强言耳) (DZ141, 12b–13a). This suggests that while the Dao is abstract and formless, it must be symbolized and metaphorized for its essence to be perceived. Daoist clothing, by concealing and revealing, not only shields the practitioner from worldly distractions (as in the phrase “the dust of the world is three thousand feet deep”) but also uses the flowing garment to subtly imply the ineffable nature of the Dao. Thus, Daoist clothing is not merely an accumulation of symbols but directly intervenes in the practitioner’s transformation of form and spirit through its tactile properties (such as the roughness of hemp fibers) and its form (such as wide sleeves).

2.3. The Cosmic Mediation of Yin–Yang and the Five Elements in Daoist Clothing

The Yin–Yang and Five Elements system (阴阳五行) is reflected in the careful arrangement of materials, colors, and patterns in Daoist clothing, which serve to regulate cosmic energies. For example, the five-colored silk ribbons (azure (青), red, yellow, white, and black) correspond to the Five Elements theory outlined in

Huainanzi’s (淮南子), creating an energetic field of “Five Qi Toward the Origin” (五炁朝元).

4 The

Wuzhen Pian (悟真篇) explains that “The generative and restrictive relationships of the Five Phases (五行) manifest as the five major planets in Heaven, the Five Sacred Peaks on Earth, the five Celestial Emperors among the deities, the five directions in space, the five internal organs in the human body, the five cardinal virtues in ethics, and in the material world, the five elemental properties and five corresponding colors…” (五贼者,在天为五星,在地为五岳,在神为五帝,在隅为五方,在人为五脏,在行为五常,在物为五行、五色、五气…) (DZ145, 16a). The

Lingbao yujian (灵宝玉鉴) from the Song dynasty stipulates that when performing the Eastern rites, one must wear an azure ribbon to invoke the energy of the Azure Dragon. The pairing of gold leaf crowns and wooden hairpins subtly reflects the generative and restraining relationships of the Five Elements, using the interactions between materials to metaphorically suggest the alchemical logic of “reverse refining into elixir” (逆炼成丹).

Furthermore, the design of patterns on the robes adheres to the natural laws of heaven, earth, and the four seasons, striving to view the human body as a microcosm of the universe. In the Sandong Fafu Kerongwen (三洞法服科戒文), it is written that “The crown imitates Heaven, adorned with the images of the sun, moon, and stars; the robe follows the Earth, its design cut in the shape of the Five Sacred Mountains; the pei represents the Dao of yin and yang, embodying the generative virtue that nourishes all beings” (冠以法天,有三光之象;裙以法地,有五岳之形;帔法阴阳,有生成之德) (DZ788, 5a–6b). Practitioners, by visualizing patterns like the Big Dipper stars (北斗七星纹), bring the cosmic laws into their bodies, aligning their energy with the universe’s. Symbols such as the Eight Trigrams (八卦) and constellations help establish a connection between clothing and the cosmic energy field, ultimately achieving a balance between physiological function and energy transformation. By adhering to natural and moral laws, practitioners can invite blessings and transcend the limitations of body and mind. Clothing, with its threefold integration of the Five Colors, Five Elements, and star patterns, reconstructs a “body-heaven congruence” energetic network on the surface of the body.

3. Materials, Craftsmanship, and Natural Symbolism

The material practice of Daoist clothing is, in essence, a concrete manifestation of the “Dao follows nature” philosophy that is achieved through technical shaping. This section explores how Daoism transforms abstract cosmology into a “wearable cultivation interface” through material selection, craftsmanship, and institutional regulation. In this process, the material system constructs a natural hierarchy based on the triadic “earth—human—heaven” logic; craftsmanship adheres to the philosophical principle of “revealing wholeness through imperfection” in an effort to resist technological alienation; and the hierarchical system of ritual clothing reflects the dynamic interplay between natural symbols and secular power. Together, these elements form the material foundation and historical context for the generation of “naturalness” in Daoist clothing.

3.1. Material Ethics: The Triadic Proof of Dao Through Earth–Human–Heaven Logic

Daoist clothing deeply embeds the cosmological view of “Dao follows nature” in its material selection, constructing the triadic “earth—human—heaven” logic through an ethical system that emphasizes “ramie for the earth, silk for heaven, and prohibition of animal pelts”. As Yang Rong notes, “When Daoism constructs the form and symbolic representations of ‘Dao—clothing,’ it is still derived from the cosmic life order and ethical structure of the Dao” (

Yang 2021, p. 70).

The Sandong Fengdao Kejie Yingshi (三洞奉道科戒营始) stipulates that “the Daoist robe (道袍) and sash (帔) for both male and female practitioners must be sewn from plain-colored cloth and silk” (布帛纯绢,漫饰衣帔) (DZ1125, 7a). The term cloth here refers specifically to hemp fabric made from ramie (苎麻) (

Na 2014, pp. 113–16). Ramie, with its rough texture and growth in the wild, is considered the “earthly garment” for ordinary Daoist practitioners. The

Daode zhenjin jiyi (道德真经集义, Collected Meanings of the Daoist Canon) states that “The reason heaven and earth can endure is that they follow natural laws without human intervention, allowing the natural qi to flow” (天地任气自然,故长存也) (DZ723, 5a). Here, the physical characteristics of ramie (such as moisture absorption and breathability) and its symbolic significance (such as simplicity and lack of adornment) both serve the goal of “unity of form and spirit” in Daoist cultivation. It should be noted that the discomfort caused by wearing ramie clothing (such as the itchy tactile experience) is intentionally preserved and transformed into a mental trial for practitioners, teaching them to “endure humiliation and relinquish desires”. In contrast to the Buddhist pāṃśukūla (粪扫衣) (ascetic clothing) logic, which uses the impurity of materials to break attachment, Daoist clothing uses materials as a mirror of nature to reflect one’s true nature.

In contrast, high-level ceremonial robes are often made from silk, with its sheen and lightness seen as embodying “cloud qi”. The Xiuzhen Shishu (修真十书) describes the attire of the immortals as follows: “Purple clouds and mists flow like dancing hems, and gauze as light as vapor floats like celestial haze” (紫霞飞裙云气罗) (DZ263, 9a). The Dongxuan lingbao Sandong fengdao kejie yingshi (洞玄灵宝三洞奉道科戒營始, Codex of Ritual Regulations for the Three Caverns) requires that high-level Daoist priests wear “cloud-colored scarves in five colors” (五色云霞帔) (DZ1125, 5a), specifying that the silk must adhere to the rhythms of sericulture. The reflective qualities of silk under sunlight create a visual communion between humans and deities, emphasizing the cosmic spirituality it embodies. Additionally, according to the Shangqing Lingbao Dafa (上清灵宝大法), “The Xuan Capital Code (玄都律) declares that all acts of killing sentient beings or willfully harming any living entity are strictly forbidden” (DZ1221, 17a). Daoism’s prohibition of animal pelts is not only rooted in compassion but also grounded in the concept of “preserving the integrity of the body”. Animal pelts are seen as vessels of “violent qi”, which may pollute the “pure Yang body” of the practitioner. This ethical system perfectly embodies the Daoist idea that “material qualities and spiritual qualities are coextensive”.

3.2. Craftsmanship and Daoism: Revealing True Wholeness Through Imperfection

Daoist garment craftsmanship adheres to the concept of “technique nearing Dao”, which particularly emphasizes intentionally preserving imperfections (such as uneven textures and protrusions) in handcraft. This approach aims to achieve the goal of “carrying Dao through art”. The core idea critiques excessive human intervention and opposes the “false perfection” pursued by mechanized production. As the

Daodejing (道德经) states, “The most complete thing seems to have imperfections, but its function never fades” (大成若缺,其用不弊) (

Laozi 2011, p. 127). This practice has some similarity with the Japanese Wabi-sabi (侘寂) aesthetic, but its essence is quite different; Wabi-sabi seeks the beauty of natural imperfections, while Daoism intentionally creates flaws to highlight the Dao. The appreciation of natural dyes (such as indigo and cinnabar) is not only due to their colors being “in harmony with the seasons” but also because their material life cycle (from growth to fading and eventually decay) naturally evolves, echoing the cosmic law of “formation, existence, decay, and emptiness”. At the same time, Daoist robes, once faded, cannot be re-dyed, emphasizing that the natural traces and changes themselves constitute a form of beauty, elevating the aging process of materials as a path to “observe transformation and realize Dao”. This idea aligns with what is stated in the

Yinfujing (阴符经): “The self-generating and self-transforming phenomena of nature are the laws of the natural world” (天生天杀,道之理也) (

Huangdi 2013, p. 5). This concept engages in a cross-temporal ecological dialogue with contemporary “circular fashion”.

Daoist scholar Li Yu, in his

Xianqing ouji (闲情偶寄), proposed transforming Daoism’s concept of “the body and clothing as one” into a specific philosophy of garment practice. He believed that clothing worn on the body is like the body adhering to its environment. The body is not just a physical form but a complete existence that includes moral cultivation and the essence of life (

Li 2003, p. 82). This idea led him to develop the craft principle of “tailoring according to the body”, rejecting the judgment of garment value based on material luxury and instead emphasizing achieving a dialectical unity of “refinement within coarseness, and depth within lightness” through craftsmanship. As he stated, “Even fabrics like cloth and ramie (a type of plant used for weaving) with a rough texture, if their threads are tightly woven and the dyeing process is refined, they become exquisite items within roughness, and deep within light colors” (

Li 2003, p. 93).

3.3. Historical Reflection: Nature and Power in the Hierarchy of Ritual Clothing

The regulatory system of Daoist clothing forms a battleground between “natural symbolism” and “power hierarchy”. As

Wen (

2023, p. 79) notes, “The classification and hierarchy of Daoist clothing reflect the ordered ethics of traditional Chinese ceremonial clothing”. With the advancement of a Daoist practitioner’s rank, the complexity and grandeur of their clothing increase (

Li 2004, p. 56). According to the regulations in the

Sandong fafu kerongwen (三洞法服科戒文) regarding the attire of Daoist priests of different ranks (DZ788, 4b-5a), the chart illustrating the levels of ceremonial robes clearly demonstrates the symbolic coding rules among the crown style, material of the robes, and rank of the priest. (See

Table 1).

The Daode zhenjin jiyi (道德真经集义) states that “Dao is the origin of the universe, the metaphysical entity, transcending all worldly existence; the vessel is the tangible form, the carrier of Dao” (形而上者谓之道,形而下者谓之器) (DZ723, 20b). This philosophical view provides a profound commentary on the Daoist ritual clothing hierarchy: the simplicity of low-ranking robes (the form in the material realm) conceals their inner grandeur (the form in the metaphysical realm), maintaining the outward appearance of “Dao follows nature”, while high-ranking robes, through material hierarchy, reflect the power structure of secular society. This duality reached its peak in the Tang dynasty’s Purple Robe system, where the imperial authority monopolized purple ceremonial robes, co-opting Daoist sacred symbols for political discipline, reflecting the complex interaction between religious authority and secular power.

4. The Spiritual Encoding of Color—The Cycles of the Five Elements and the Fragmentation of Power

The color system in Daoist clothing is a concrete manifestation of the “Dao follows nature” philosophy in the visual dimension. Using the cyclical logic of the Five Elements color spectrum, the dynamic dialectics of ritual colors, and cross-cultural philosophical comparisons as an analytical framework, this section explores how color, through natural coding, power intervention, and bodily discipline, becomes a “dynamic energy medium” that facilitates communication between heaven and humanity. The Five Colors (五色), as representations of the Five Elements (五行) and Five Directions (五方), form the foundational symbolic system of Daoist color philosophy. Meanwhile, the critical transformations in rituals lend fluidity to color, and cross-religious comparisons further highlight the uniqueness of Daoist color philosophy—its nonlinear, cyclical logic is deeply tied to natural rhythms, providing new perspectives and paradigms for global material culture studies.

4.1. The Five Elements Color Spectrum: The Symbolic Weave of Natural Order

The color system of Daoist clothing is essentially a wearable energy topology constructed based on the “Yin-Yang-Five Elements” cosmology. According to the concept of the Five Elements generating and overcoming logic in

Huainanzi (淮南子) (“Water nourishes Wood, Wood fuels Fire, Fire generates Earth, Earth produces Metal, and Metal generates Water”) (水生木,木生火,火生土,土生金,金生水) (

Liu 2017, p. 129), the Five Colors—azure (青), crimson (赤), yellow (黄), white (白), and black (黑)—correspond to the energy symbols of wood, fire, earth, metal, and water, respectively, forming a dynamic network of “Five Qi Toward the Origin” (五炁朝元). This color spectrum system is not merely a simple categorization of colors; through the coupling of “color-qi-spirit”, it regulates energy within the clothing. Color serves as both the material manifestation of the Five Elements’ energy fields and the ritual interface for “human-deity communion”. According to the

Yunji Qiqian (云笈七签) (Cloud Scriptures), in Daoism, the correspondence between the Five Emperors and the Five Elements, as well as the Five Organs, including related divine figures and their attire (

Zhang 1996, pp. 309–10), the symbolic characteristics of the Daoist Five Elements color spectrum can be summarized, as shown in

Table 2.

The Daoist Five Phase (五行) chromatic spectrum system transcends static semiotic cognition to construct a ternary “Color–Qi–Sheng” (形—气—神) energy model. In this framework, the hues of ritual vestments (色) function as dynamic vessels of energy that by means of the generative–conquering cycles of the Five Phases—for example, the mutual generation of metal and water evidenced by the interplay of white and black—establish conduits between the cosmos and the human body, thereby directing the flow of qi (气) (e.g., combinations of red activate cardiac qi) and culminating in transformative effects on the spirit (神). By extending the traditional directional palette of the Five Phases (五方五色) into what may be termed a programmable energy interface, Daoist practitioners effect an internal alchemical circulation—through the stationing of the Five Emperors within the Five Zang (五藏)—while also dynamically modulating functions within ritual contexts (e.g., red for petitions of blessing, black for return to the source). Such praxis exemplifies the “correspondence of Heaven and Man” (天人同构) theorized in the Yunji Qiqian (云笈七签), thereby constituting a wearable system of energy recomposition.

4.2. Critical Manifestation: Dialectics of Color in Rituals

In Daoist ritual practice, the sacredness of color exhibits a dynamic transformative quality, with its meaning manifesting in the threshold state of “purity—pollution” and the reconstruction of identity. Taking black as an example, in exorcism rituals, priests transform black into a medium that penetrates space and drives away evil spirits through practices such as face painting and the use of black flags. In this context, black is imbued with an impure connotation, serving as a warning for practitioners to stay away from malign forces. In the “Breaking the Prison” ritual of the death rites, black silk cords symbolize the channel to the underworld, undergoing a complete lifecycle from “binding and wearing” to “burning and dissolution”. The priest ties the cord at a specific time to communicate with the Nine Hells, and after the ritual, the cord is burned. Through this “contact and removal” mechanism, the symbolic meaning of the color shifts from a “medium for communication with the underworld” to a dialectical reversal of the “separation of Yin and Yang”. This transformation illustrates the strategic use of color in Daoism as a “temporary pollution”—an approach where the ritual operation of “use and discard” reveals the reversible conversion of color meaning within a specific spatiotemporal context.

The symbolic tension of red is even more intense. Cinnabar-dyed red ceremonial robes in rituals transform into the manifestation of the fire deity “Emperor Zhu Rong”, as described in

Taiping jinchao太平经钞: “During the beginning of summer, the divine officials wear red robes to guard, and the red robes’ fire power can expel the hundred demons” (立夏日盛德火,神吏赤衣守之,百鬼去千里) (DZ408, 3a-3b). In this ritual, the visual impact of red is transformed into the exorcistic force of “violence countering violence”. However, in daily practice, the color red is strictly regulated.

Zouyi Cantong Qi (周易参同契) warns that “The primordial spirit, like the sun’s red radiance, flows outward and scatters. If not cultivated and controlled, it will dissipate” (太阳流珠,常欲去人) (

Wei 2014, p. 270). This internal contradiction underscores the core principle of Daoist color philosophy: the symbolic power of color is not derived from absolute prohibition but from the dynamic balance of technique, which is precisely adjusted within ritual contexts, allowing a single color to move freely between sanctity and danger, embodying the fluidity of “Dao follows nature”.

Fundamentally, the establishment of the Tang-period Daoist “purple robe” (紫袍) system represents a dynamic interpenetration between religiously sacralized symbols and the secular apparatus of imperial power. At the level of semiotics, Daoism achieves a decodification of sartorial politics by restructuring the cultural genetics of the color purple. In the Confucian ritual canon, “Purple is regarded as an intermediate hue, in contrast to the primary colours (cyan, vermilion, yellow, white, and black). Among the five official pigments, purple is deemed a flaw or defect” (紫,疵也,非正色,五色之疵瑕。) (

Liu 2016, p. 62). “The Purple Forbidden Enclosure (紫微垣) comprises fifteen stars, and its nucleus the Purple Forbidden (紫薇) is conceived as the Celestial Emperor’s abode, mirroring the palace of the earthly Son of Heaven” (紫宫垣十五星,一曰紫微,大帝之坐也,天子之常居也) (

Fang 2015, p. 78). The very spatial arrangement of these star mansions mirrors the terrestrial imperial court. The modern name of the Forbidden City, for example, is derived from this “Purple Forbidden Palace” analogy. Daoist canonical texts further solidify this celestial theology: according to the

Lingbao Wuliang Duren Shangpin Miaojing (灵宝无量度人上品妙经), “Within the Xuan-du Ziwei Palace (玄都紫微宫) dwell the highest divinities who preside over and regulate the orthodox path of the cosmos” (玄都紫微宫正气大神) (DZ 92,2a). Through this topological reconfiguration—from terrestrial “blemish” to transcendent sacramental code—purple vestments are re-legitimated beyond mundane hierarchical chromatics.

This astro-theological reconstrual furnishes the theoretical underpinning for the purple robe’s emancipation from secular sumptuary restraints. As recorded in

Shiwu jiyuan (事物纪原) (

Gao 1989, p. 384), “Since the reign of Emperor Tang Daizong, when Li Mi received the purple robe for his great achievements, awarding purple robes to Daoists became institutionalized”. By reinterpreting the imperial vestiture as a “mandated sacramental robe”, the ceremonial lexicon of political investiture is transposed into a Daoist “alliance-authority ritual” (mengwei keyi), rendering the purple robe as a material carrier through which Daoist succession integrates—and yet remains distinct from—secular legitimacy. This dialectic of “institutional dependence versus symbolic autonomy” not only harnesses imperial power to sacralize Daoist orthodoxy but, through practices such as the ritual burning of obsolete talismans, actively forestalls the ossification of meaning—thereby sustaining a dynamic mutual permeation of sacral and secular spheres without unilateral co-optation.

4.3. Cross-Civilizational Reflections: The Color Poetics of Cyclical Cosmology

The Daoist Five Color system exhibits a fundamentally different logic than the chromatic lexicons of other religious traditions. In Christianity, liturgical colors intertwine biblical exegesis, ecclesiastical authority, and material culture in a multi-dimensional semiotic synthesis distinct from Daoist cosmogenic quintessence. Purple in the Roman Rite, for instance, marks both Advent and Lent—symbolizing penitential humility (

International Committee on English in the Liturgy 2003, p. 83) and, simultaneously, implicitly invoking imperial majesty (Joel 2:12–13, New Revised Standard Version). Red appears on Palm Sunday, on Good Friday, during the Pentecost, and in commemorations of martyrs—embodying both the Blood of Christ (Revelation 6:9, NRSV) and the fiery tongue of the Holy Spirit. Scarlet silk, which is reserved exclusively for cardinals, derives its significance from its costly dye, underscoring hierarchical distinction.

Early Buddhism, by contrast, institutes a protocol of “defiled hues” (坏色) for monastic robes: “Should a bhikṣu receive new robes, they are required to dye them in one of three colours—green, black, or indigo” (若比丘得新衣,应三种坏色,一一色中随意坏,若青,若黑,若木兰) (

Daoxuan 2015, p. 280). Yet, in its cross-cultural transmission, this chromatic austerity generated diverse adaptations: the reddish-brown and yellow-brown robes worn by Theravada Buddhist monks are cut, sewn, and dyed in accordance with the regulations of Buddhism. (

Ma 2016, p. 62), Tibetan Buddhism associates five colors with the Five Dhyani Buddhas in a tantric semiotic system (

Yin 2013, p. 29), and Shingon Buddhism in Japan merges esoteric bodhicitta symbolism with Shintō funerary traditions to establish a white-garbed ascetic praxis. These metamorphoses of color semantics manifest the Buddhist philosophy of

pratītyasamutpāda (dependent origination and emptiness).

By contrast, Daoism’s chromatic paradigm constitutes a self-sustaining energetic network: the Five Colors, each corresponding to one of the wuxing (Five Phases), circulate in perpetual renewal. This chromatic cycle not only models the cosmic rhythm but invests color itself with poetic resonance and philosophical depth, constructing nonlinear, dynamic poetics of color that epitomize Daoist cyclical cosmology.

5. Cosmological Narratives in Patterns—Symbolic Practices of the Unity of Body and Heaven

The pattern system of Daoist clothing centers around the principle of “following heaven and reflecting earth” (法天象地). Through symbols such as celestial imagery, sacred beasts, and the Eight Trigrams, it constructs a cosmological model that resonates both internally and externally, achieving a dynamic unity between the body and the universe. This practice not only responds to the concept of the body in

Yunji qiqian (云笈七签), which suggests that “the three primordial energies within the human body transform and internalize to form three energy centers” (

Zhang 1996, p. 59) but also symbolically expresses the ideas advocated in the

yinfujing (阴符经), which states that “by cultivating the body and understanding the natural laws, one can achieve harmony with the universe, thereby influencing and embodying cosmic changes” (

Huangdi 2013, pp. 14–15). Thus, a complete wearable interpretation of “Dao follows nature” is constructed.

5.1. Celestial Imagery as Latitude: The Topological Mapping of Heaven–Human Energy

The celestial patterns on Daoist clothing are not mere replicas of astronomical imagery but are carefully designed to align with specific directions, creating an energy network of “Heaven天—Human人—Qi气”. For example, the embroidery of the Big Dipper on high-level Daoist coronets is based on the principle from

Zouyi Cantong Qi (周易参同契), which states that “The Big Dipper’s handle follows a prescribed path, balancing the celestial Dao and determining the fundamental laws of the universe” (

Wei 2014, p. 330). The handle points to the crown of the head, the “Shen Palace” (or the crown chakra), the central energy zone of the brain, establishing a conduit for “heavenly light entering the body”. As recorded in

Yunji qiqian (

Zhang 1996, p. 169), “On the day of the Spring Equinox, people face east and observe the Big Dipper. The Dipper descends, and the handle points to the east, a sign of good fortune”. This design visually guides the wearer, facilitating a transformative embodied experience of unity between body and mind during cultivation. For example (

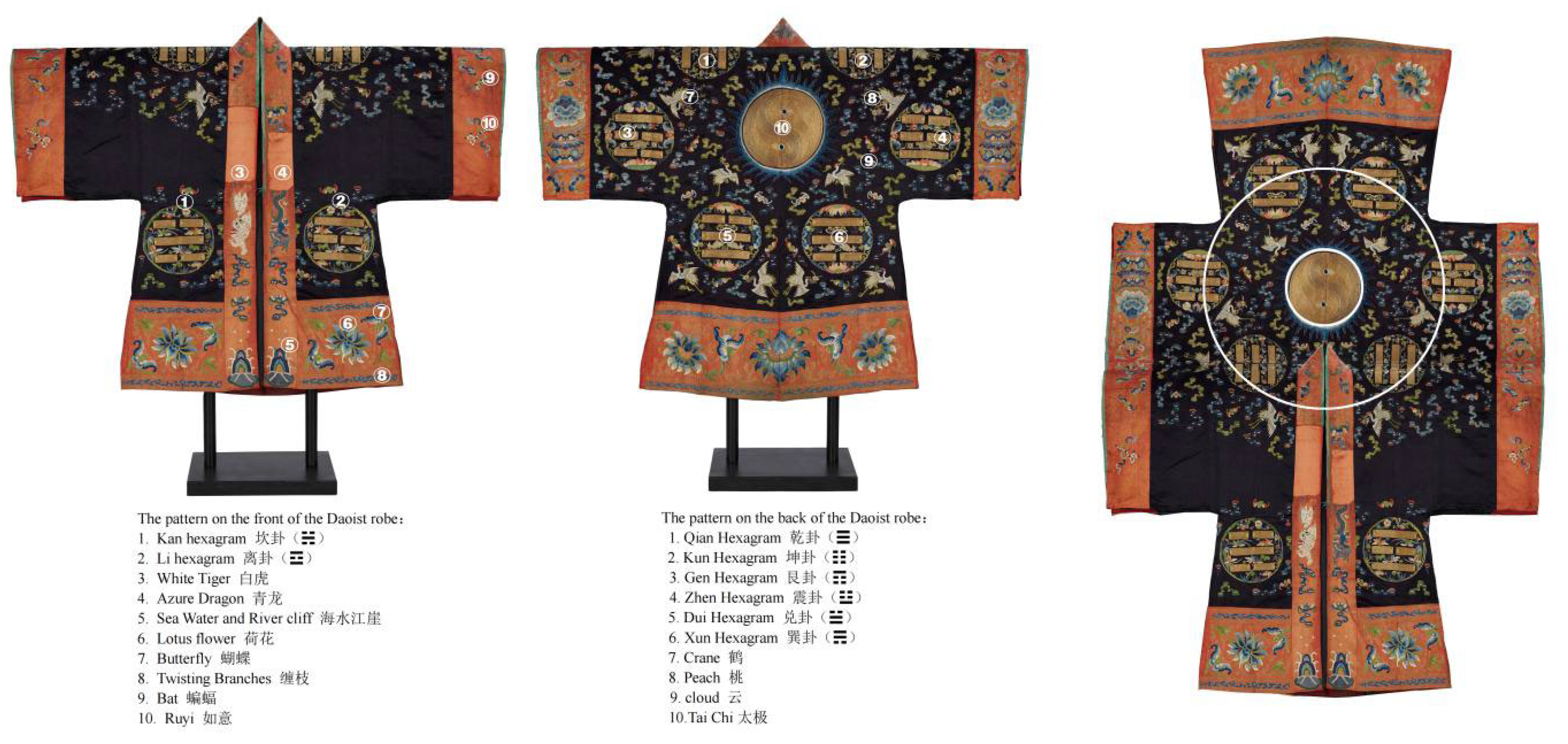

Figure 1), on the back of the ritual robe, the central round position symbolizes the “Yuluo Xiaotai” (郁罗箫台) (the platform of cosmic energy), surrounded by the 28 lunar mansions, representing the cosmic cycle and life energy’s reflection. This design aligns closely with the ritual practices of the Xuanmiao Temple’s orthodox Daoist sect in Suzhou, where priests, following specific steps, symbolically traverse the 28 lunar mansions (

Research Group of Chinese Dance Art Association 2009, p. 44). This synchronization of bodily movement with the positioning of the lunar mansions allows for a resonating practice of “unity between heaven and humanity”. This transition from static symbolism to dynamic regulation transcends traditional iconography, turning the clothing into a wearable celestial instrument capable of regulating and transmitting “Qi”.

5.2. Life Force as the Sutra: Natural Symbols as Life Metaphors

The natural symbol system in Daoist clothing is built on the core of “Dao follows nature”, constructing a unique dynamic view of life that contrasts ontologically with the transcendental symbols in Western religions. Unlike the Christian cross, which symbolizes redemption, or the Buddhist lotus, which symbolizes detachment, Daoism transforms natural imagery into an embodied practice medium through plant and animal motifs, presenting it as a cognitive paradigm of “unity between the body and heaven”.

The evolution of the peach pattern is a typical example of how Daoist symbols generate dynamic logic. From the mythological tales in

Shanhai jing (山海经) to the exorcism applications in

Jingchu suishiji (荆楚岁时记), the peach pattern ultimately transcended the “three-circle cycle” found in Daoist robes. The life cycle of the peach tree—“flowers bloom in spring, fruit ripens in autumn, and it rests in winter”—mirrors the fixed cycles of the sun and moon as described in the

Yinfujing (阴符经), embodying the Daoist principle that “everything has its predetermined course” (日月有数,大小有定) (

Huangdi 2013, p. 6). The entwined vine patterns break free from the constraints of Confucian ethical symbols. Their continuous spiral structure reflects the idea in the

Daodejing (道德经) that “the Dao generates one, one generates two, two generates three, and three generates all things” (道生一,一生二,二生三,三生万物) (

Laozi 2011, p. 120). This dynamic symbol transforms the pattern into the flow of qi and spatial–temporal coordinates, bestowing garments with a new energy-regulating function. The crane pattern, which symbolizes Daoist cultivation, evolved from the Han dynasty’s imagery of “becoming immortal” to the “Crane Cloak and Seven-Star Step” in ritual guidance. Through the integration of patterns and ritual movements, static symbols are transformed into lively and dynamic ones.

5.3. The Metamorphosis of the Eight Trigrams: The Self-Reconstruction of Sacred Symbols

The semantic evolution of the Eight Trigrams (八卦) pattern reveals the adaptability and inherent resilience of the Daoist symbol system throughout historical changes. Early ritual robes placed the Eight Trigrams embroidery at the center of the back, following the principle of “observing phenomena and extracting their symbols” through directional arrangement and the symbolism of natural phenomena (e.g., the Li Trigram (离卦) representing the southern fire, and the Kan Trigram (坎卦) symbolizing northern water), fulfilling the divinatory function of “observing heavenly phenomena and examining earthly geography”. This practice resembles the directional divination tools used in shamanic rituals but emphasizes the use of the

Yinfujing (阴符经) concept of “combining the Eight Trigrams with the Heavenly Stems and Earthly Branches to reveal the cosmic mechanisms of heaven and earth” (八卦甲子,神机鬼藏) (

Huangdi 2013, p. 11). For example (

Figure 2), on the royal Daoist robe now housed in the Victoria and Albert Museum, the left side of the front shows the Li Trigram (representing south and fire), while the right side shows the Kan Trigram (representing north and water). This design aligns with the

Zouyi Cantong Qi (周易参同契) principle, which states that “the Kan and Li form the framework for the Yin-Yang changes, like the spokes of a wheel revolving around its axis, where the Yin and Yang energies circulate endlessly, giving birth to all things” (坎离匡郭,运毂正轴) (

Wei 2014, p. 2). The

Qiankun Trigram (乾坤卦) on the shoulders symbolizes the balance and harmony between heaven and earth, while the surrounding

Gen (艮),

Zhen (震),

Dui (兑), and

Xun (巽) Trigrams form a large circle around the Taiji symbol on the back. The embroidery of the Taiji symbol adheres to the Yin–Yang fusion concept, visually representing the

Daodejing’s (道德经) description, which states that “all things carry Yin but embrace Yang, the Yin and Yang energies clash and merge to achieve harmony” (万物负阴而抱阳,冲气以为和) (

Laozi 2011, p. 120). The two concentric circles centered around the Taiji symbol represent the cyclical and harmonious flow of all things (

Kohn 2014, p. 36), aligning with

Zhangzi’s (庄子) assertion that “The beginning and end of things are like a circle, constantly revolving without clear endpoints or order” (始卒若环,莫得其伦) (

Zhuangzi 2019, p. 475).

During the Quanzhen Daoist period, as Daoism became more secularized, the Eight Trigrams pattern gradually moved from the central region of the robe to the sleeves and hem, becoming more abstract in geometric decoration. This phenomenon reflects Jean Baudrillard’s theory of “symbolic implosion”, where sacred symbols gradually lose their original meaning in the process of secularization. However, Daoist craft traditions still maintain the ontological depth of these symbols through spatial narratives. As noted in the

Zhouyizhuan (周易传注), ”The Dao is constantly changing, not stagnant or unchanging” (为道也屡迁,变动不居) (

Li n.d., p. 15). The evolution of Daoist symbols is not only a transformation of symbolic meanings but also an expression of the generative nature of the “unity of Dao and vessel” (道器合一).

6. Conclusions

This study reveals the relationship between Daoist attire’s material practices and philosophical propositions, exploring how “materiality” becomes a practice path for experiencing the cosmos’s essence. By constructing a three-dimensional framework of “material—color—pattern”, it demonstrates how the Daoist concept of “Dao follows nature” is translated into matter through clothing symbols. The natural and artificial qualities of materials dialectically reconstruct the ethics of cultivation; colors balance the sacred and the secular; and patterns transform cosmological theories into embodied techniques.

We propose the concept of the dynamic cultivation interface, breaking the prevailing static semiotic approach in religious art studies and offering an embodied perspective for material–culture scholarship. Moreover, we identify the Daoist costume’s intentional imperfections—its “flawed body” philosophy—as a critical resource against modern technological rationality. We also uncover the nonlinear regulatory mechanism of the Five Color system, whose dynamic recombinatory patterns transcend the Five Phase generative–restrictive schema and inspire an eco-wisdom of harmonious resilience for sustainable global design. In dialogue with contemporary material–turn scholarship, this research both resonates with Alfred Gell’s thesis of the agency of things and advances it through a qi–pattern interaction model. Daoist dress not only acts as a social agent but, via topological mappings of stellar motifs, intervenes directly in the circulatory dynamics of cosmic energy. On a phenomenological plane, the tactile coding of the ritual robe (e.g., the coarse feel of hemp fabric) and its visual evanescence (e.g., the gradated Bagua pattern) jointly constitute an embodied cognitive technology, providing cross-cultural validation for Merleau-Ponty’s theory of the body schema.

Future research may also explore gender politics in Daoist attire, the use of digital technologies to reconstruct dynamic semantics of patterns, and uncovering Daoist “anti-consumerism” heritage for sustainable design. Overall, the ultimate value of Daoist attire transcends the aesthetic realm, with its core being the ontological insight of “attaining Dao through objects”, which encourages humanity to practice through the authentic existence of objects, re-examining the symbiotic relationship between nature and human nature.