Compositional Analysis of Cultic Clay Objects from the Iron Age Southern Levant

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. The Case Studies: Results

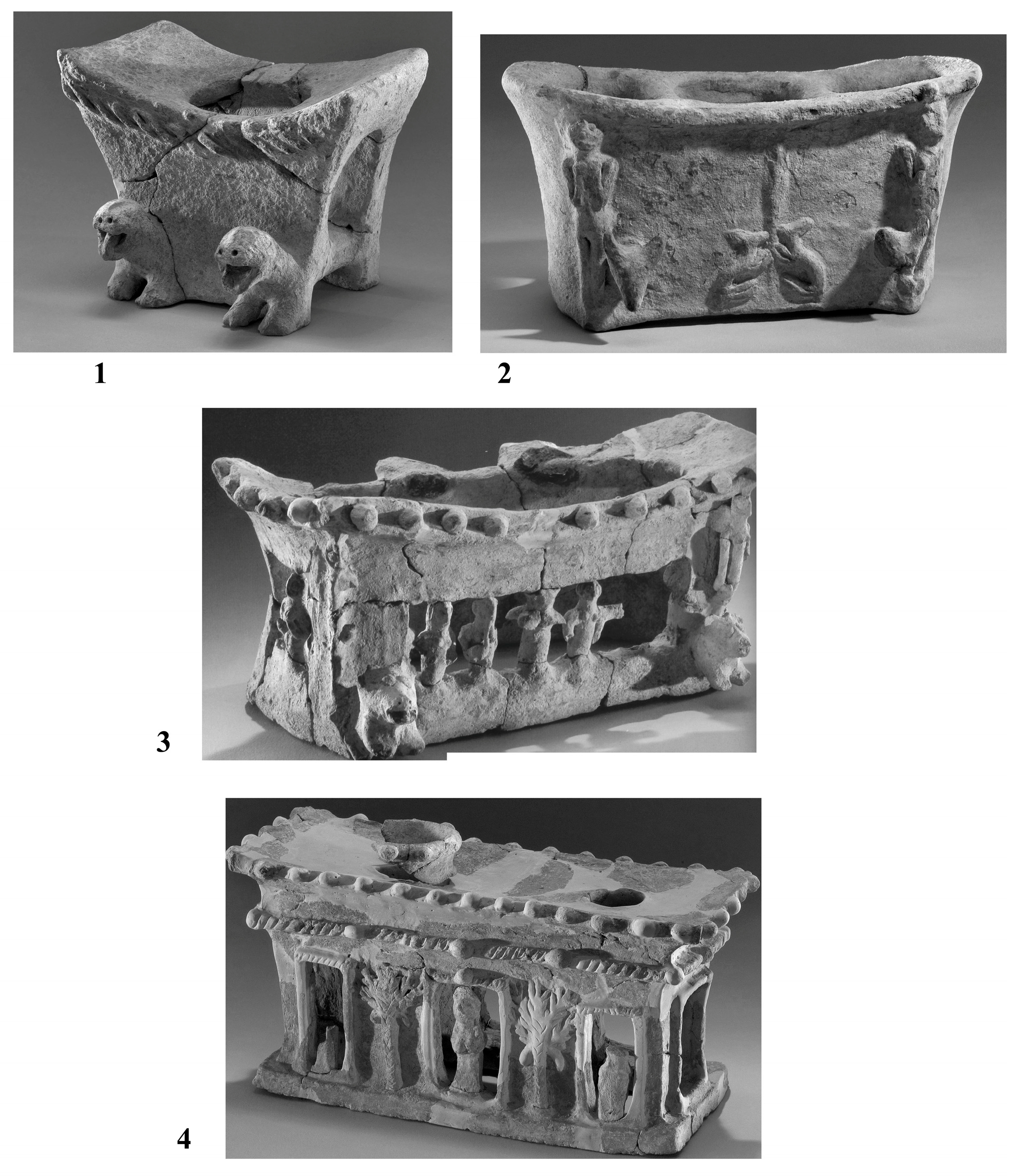

3.1. Temple Cult

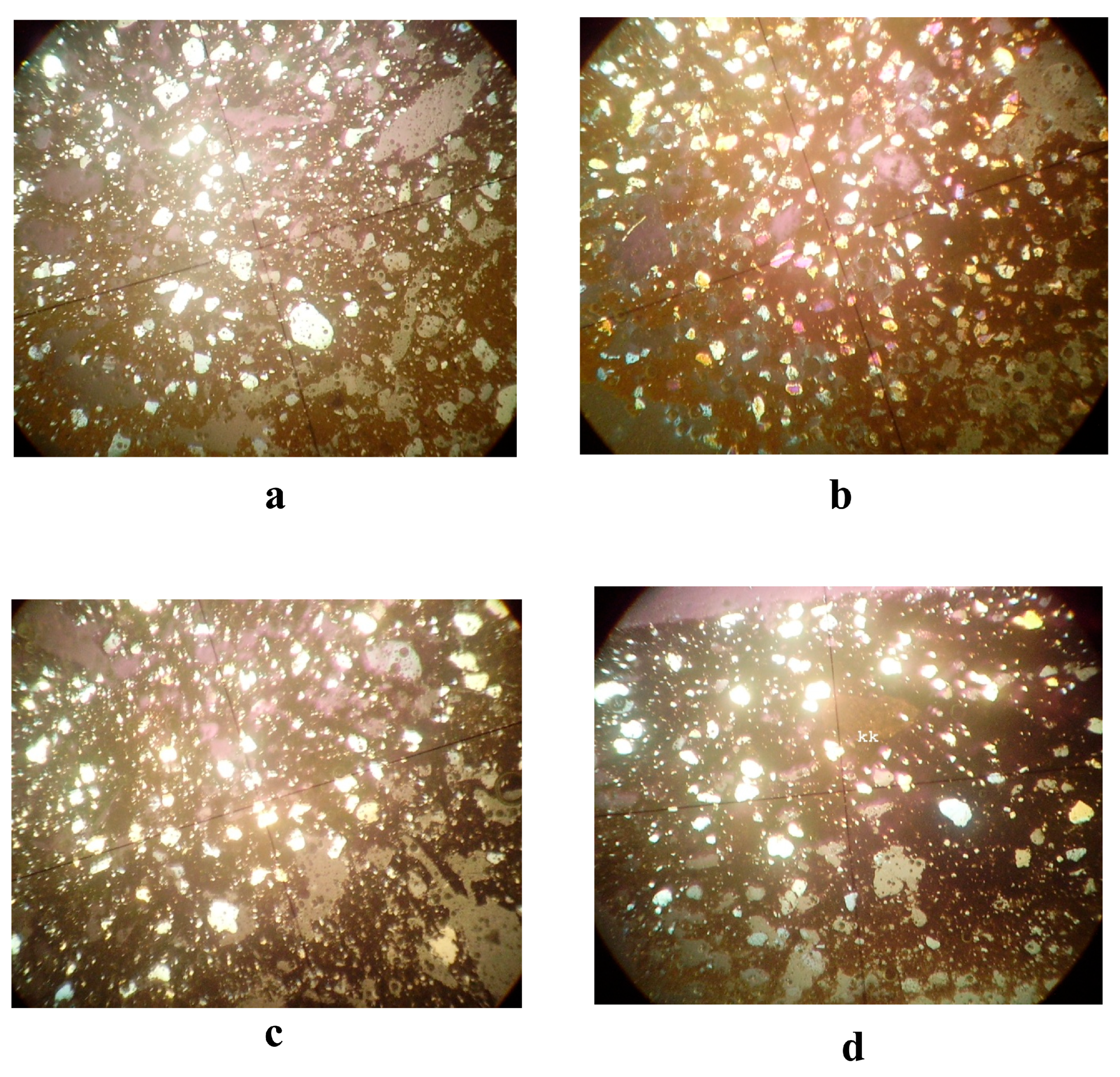

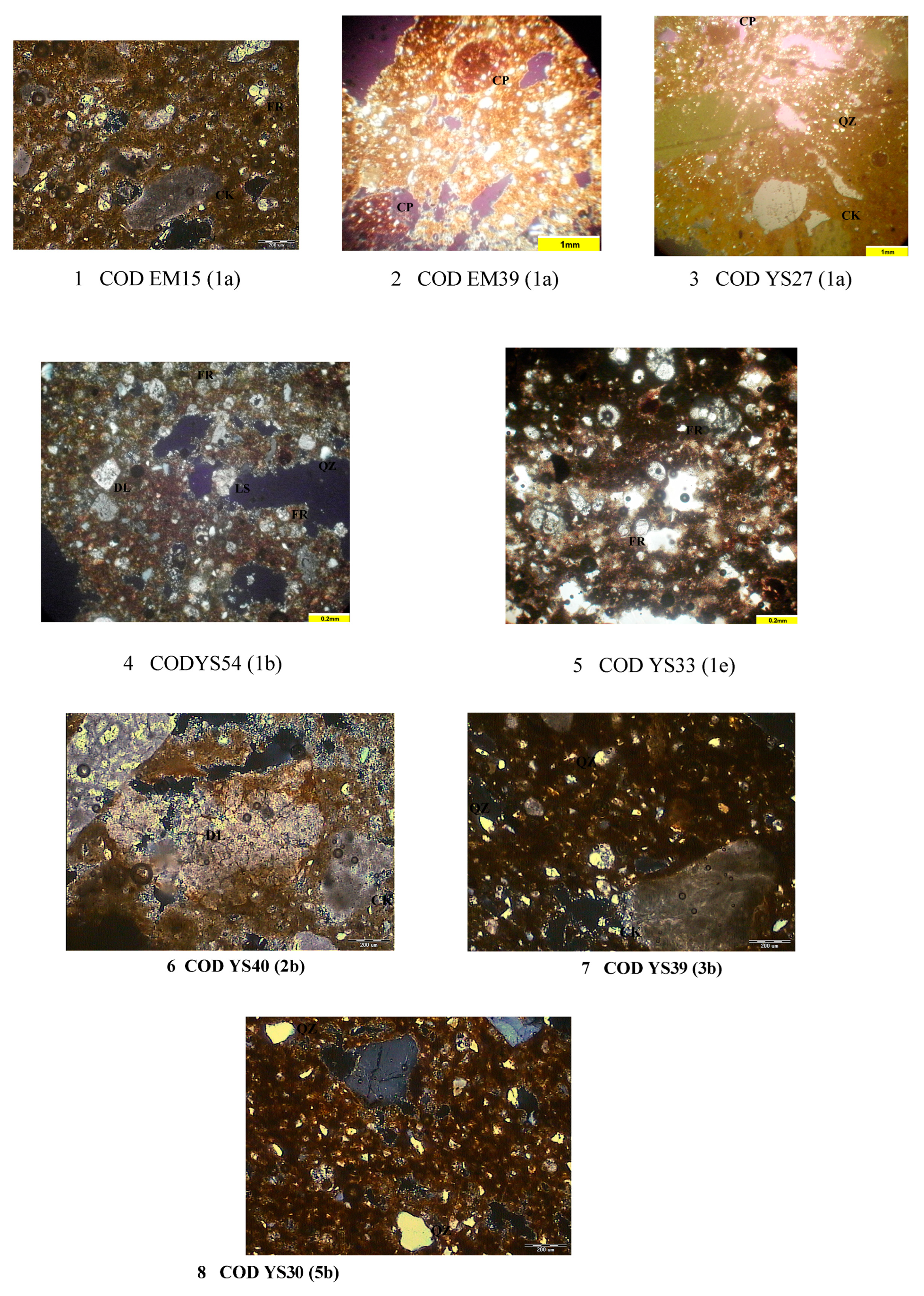

Petrographic Results

3.2. Domestic Cult

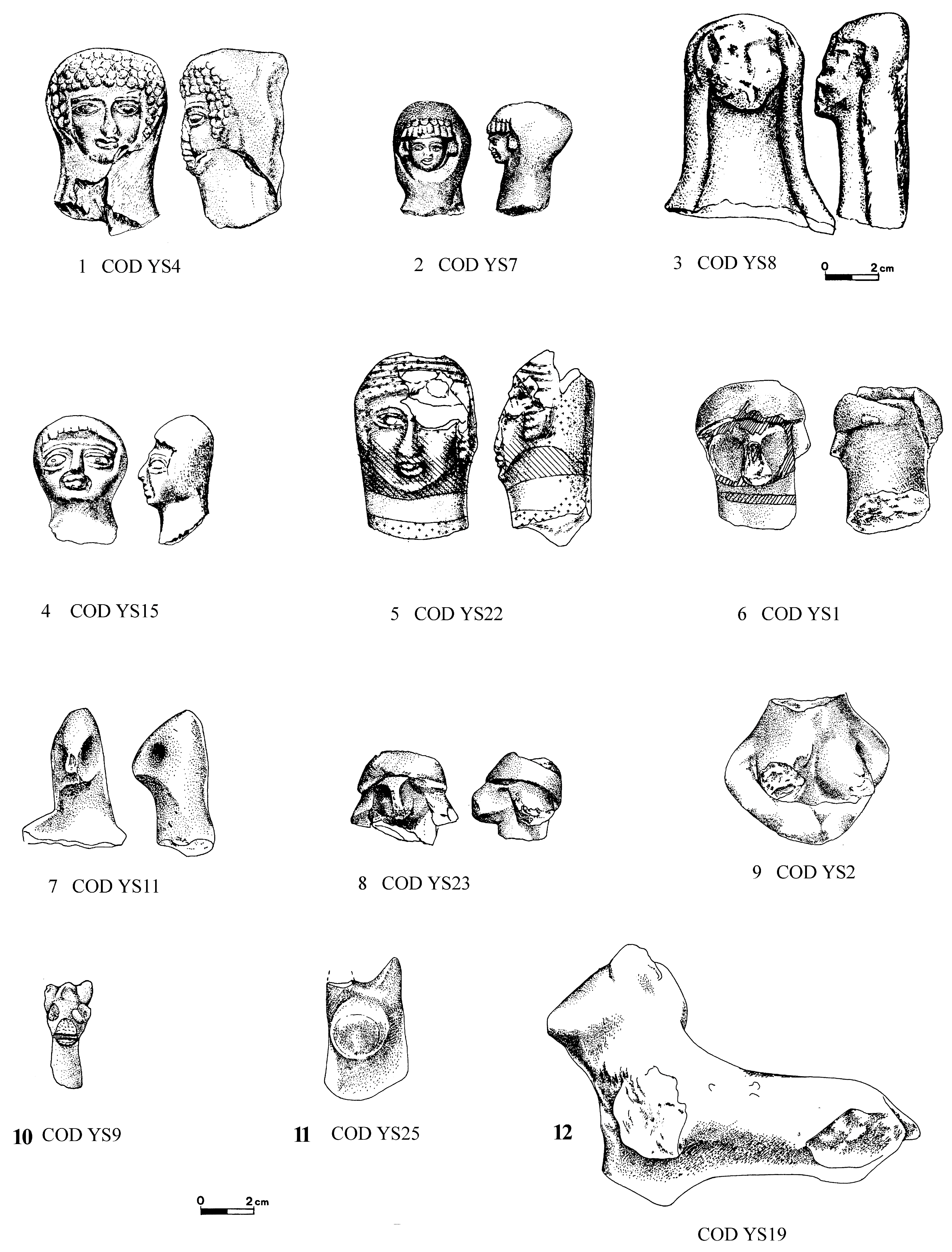

3.2.1. Figurines from Jerusalem

3.2.2. Petrographic Analysis

3.2.3. Tell En-Naṣbeh

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The JPFs can be interpreted in a non-religious or non-cultic manner (an “amuletic” function can also be considered cultic), for example, toys or “dolls” (e.g., Kletter 2001, pp. 195–201). However, this interpretation seems unlikely, particularly in this case, due to their quantities, distribution, and rather standardized modeling. |

References

- Abusch, Tzvi. 2002. Mesopotamian Witchcraft. Towards a History and Understanding of Babylonian Witchcraft Beliefs and Literature. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Amr, Abdul-Jalil. 1980. A Study of the Clay Figurines and Zoomorphic Vessels of Trans-Jordan During the Iron Age, with Special Reference to Their Symbolism and Function. Ph.D. dissertation, University of London, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Arieh, Sarah. 2011. Temple Furniture from a Favissa at ‘En Hazeva. Atiqot 68: 107–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shlomo, David. 2015. Petrographic Analysis of Iron Age IIA Figurines from the Ophel. In The Ophel Excavations to the South of the Temple Mount 2009–2013. Edited by Eilat Mazar. Final Reports Volume I. Jerusalem: Shoham, pp. 563–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shlomo, David. 2019. The Iron Age Pottery of Jerusalem: A Typological and Technological Study. Ariel University Institute of Archaeology Monograph Series 2. Ariel: Ariel University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shlomo, David. 2021. Petrographic Analysis of Iron Age Pottery from Tell en-Naṣbeh. Judea and Samaria Research Studies 30: 57–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Shlomo, David, and Amir Gorzalczany. 2010. Petrographic Analysis. In Yavneh I: The Excavation of the ‘Temple Hill’ Repository Pit and the Cult Stands. Edited by Raz Kletter, Irit Ziffer and Wolfganf Zwickel. OBO SA 30. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, pp. 142–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shlomo, David, and Erin D. Darby. 2014. A Study of the Production of Iron Age Clay Figurines from Jerusalem. Tel Aviv 41: 180–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Shlomo, David, and Lauren K. McCormick. 2021. Judean Pillar Figurines and “Bed Models” from Tell en-Nasbeh: Typology and Petrographic Analysis. BASOR 386: 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

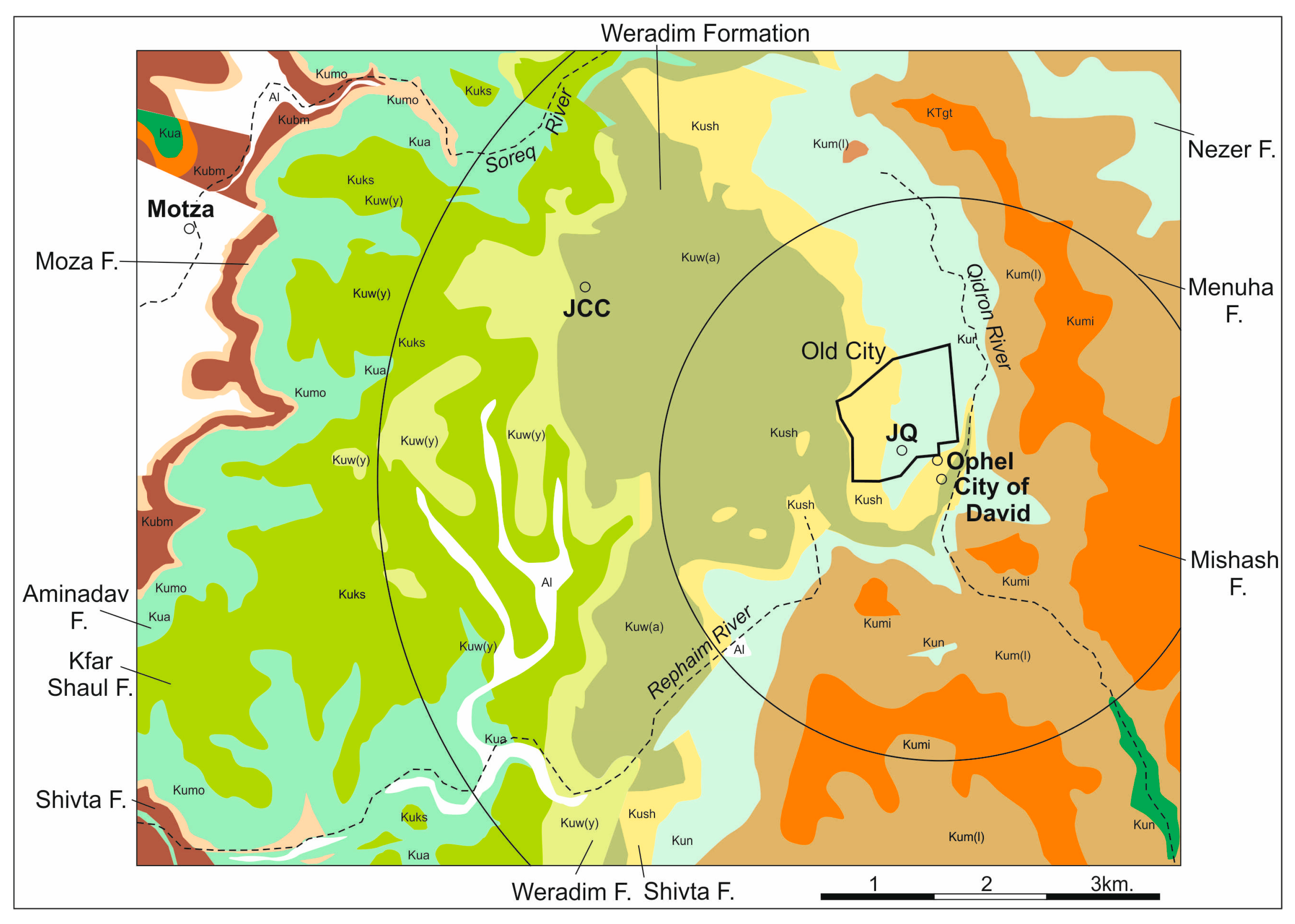

- Ben-Shlomo, David, and Oren Ackerman. 2019. The Geology and Environment of Jerusalem and its Potential Clay Sources. In The Iron Age Pottery of Jerusalem: A Typological and Technological Study. Edited by David Ben-Shlomo. Ariel University Institute of Archaeology Monograph Series 2. Ariel: Ariel University Press, pp. 37–57. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, Ryan. 2004. Lie Back and Think of Judah: The Reproductive Politics of Pillar Figurines. Near Eastern Archaeology 67: 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Weinberger, Anat. 2011. Provenance of the Clay Artifacts from the Favissa at ‘En Ḥaẓeva. Atiqot 68: 185–89. [Google Scholar]

- Dan, Joel, Dan H. Yaalon, and Hana Koyumdijsky. 1972. The Soil Association Map of Israel, 1:1,000,000. Israel Journal of Earth-Sciences 21: 29–49. [Google Scholar]

- Dan, Joel, Zvi Raz, Dan H. Ya’alon, and Hana Koyumdjisky. 1975. Soil Map of Israel. Jerusalem: Ministry of Agriculture. [Google Scholar]

- Darby, Erin D. 2011. Interpreting Judean Pillar Figurines: Gender and Empire in Judean Apotropaic Ritual. Ph.D. dissertation, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Darby, Erin D. 2014. Interpreting Judean Pillar Figurines: Gender and Empire in Judean Apotropaic Ritual. Forschungen zum Alten Testament, 2. Reihe 69. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Google Scholar]

- Day, Peter M., Louise Joyner, Vassilis Kilikoglou, and Geraldine C. Gesell. 2006. Goddesses, Snake Tubes, and Plaques: Analysis of Ceramic Ritual Objects from the LM IIIC Shrine at Kavousi. Hesperia 75: 137–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dever, William G. 2005. Did God Have a Wife? Archaeology and Folk Religion in Ancient Israel. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Duistermaat, Kim. 2008. The Pots and Potters of Assyria: Technology and Organisation of Production, Ceramic Sequence and Vessel Function at Late Bronze Age Tell Sabi Abyad, Syria. (Papers on Archaeology of the Leiden Museum of Antiquities 4). Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Fillieres, Dominique, Garman Harbottle, and Edward V. Sayre. 1983. Neutron-Activation Study of Figurines, Pottery, and Workshop Materials from the Athenian Agora, Greece. Journal of Field Archaeology 10: 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfinkel, Yosef. 2020. The Face of Yahweh? Biblical Archaeology Review 46: 30–33. [Google Scholar]

- Gheorgiu, Dragoş. 2010. Ritual Technology: An Experimental Approach to Cucuteni-Tripolye Chalcolithic Figurines. In Anthropomorphic and Zoomorphic Miniature Figures in Eurasia, Africa and Meso-America: Morphology, Materiality, Technology, Function and Context. Edited by Dragoş Gheorgiu and Ann Cyphers. BAR IS 2138. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert-Peretz, Diana. 1996. Ceramic Figurines. In City of David IV. Edited by Donald T. Ariel and Alon De-Groot. D. Qedem 35. Jerusalem: Hebrew University, pp. 29–86. [Google Scholar]

- Goren, Yuval. 1995. Shrines and Ceramics in Chalcolithic Israel: The View through the Petrographic Microscope. Archaeometry 37: 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goren, Yuval. 1996. The Southern Levant in the Early Bronze Age IV: The Petrographic Perspective. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 303: 33–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goren, Yuval, Israel Finkelstein, and Nadav Na’Aman. 2004. Inscribed in Clay: Provenance Study of the Amarna Tablets and Other Ancient Near Eastern Texts. Tel Aviv University, Institute of Archaeology Monograph Series 23. Tel Aviv: Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Archaeology. [Google Scholar]

- Goren, Yuval, Raz Kletter, and Elisheva Kamaiski. 1996. The technology and provenience of the Iron Age figurines from the City of David: Petrographic Analysis. In City of David Excavations, Final Report IV. Edited by Donald T. Ariel and Alon De-Groot. Qedem 35. Jerusalem: Hebrew University, pp. 87–89. [Google Scholar]

- Gunneweg, Jan, and Hans Mommsen. 1995. Instrumental Neutron Activation Analysis of Vessels and Cult Objects. In Horvat Qitmit. An Edomite Shrine in the Biblical Negev. Edited by Izhak Beit Arieh. Tel Aviv: Institute of Archaeology, pp. 280–86. [Google Scholar]

- Gunneweg, Jan, Thomas Beier, Ulrich Diehl, D. Lambrecht, and Hans Mommsen. 1991. ‘Edomite’, ‘Negbite’ and ‘Midianite’ Pottery from the Negev Desert and Jordan. Archaeometry 33: 239–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadley, Judith M. 2000. The Cult of Asherah in Ancient Israel and Judah. Evidence for a Hebrew Goddess. Cambridge: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, Thomas A. 1995. A Study of Palestinian Iron Age Baked Clay Figurines, with Special Reference to Jerusalem Cave I. In Excavations by K. M. Kenyon in Jerusalem 1961–1967: Volume 4: The Iron Age Cave Deposits on the South-east Hill and Isolated Burials and Cemeteries Elsewhere. Edited by Itzhak Eshel and Kay Prag. Oxford: University Press, pp. 159–89. [Google Scholar]

- Karageorghis, Vassillis, Nota Kourou, Vassilis Kilikoglou, and Michael D. Glascock. 2009. Terracotta Statues and Figurines of Cypriote Type Found in the Aegean. Provenance Studies. Nicosia: Levantis Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Kletter, Raz. 1996. The Judean Pillar-Figurines and the Archaeology of Asherah. BAR IS 636. Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Kletter, Raz. 2001. Between Archaeology and Theology: The Pillar Figurines from Judah and the Asherah. In Studies in the Archaeology of the Iron Age in Israel and Jordan. Edited by Amihai Mazar. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series 331. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, pp. 179–216. [Google Scholar]

- Kletter, Raz, Irit Ziffer, and Wolfgang Zwickel. 2010. Excavations at Yavneh I: The ‘Temple Hill’ Repository of Cultic Stands. OBO SA 30. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Kletter, Raz, Irit Ziffer, and Wolfgang Zwickel. 2015. Excavations at Yavneh II: The ‘Temple Hill’ Repository of Cultic Stands. OBO SA 36. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Kreiter, Attila, and György Szakmány. 2011. Petrographic analysis of Körös ceramics from Méhtelek–Nádas. In The First Excavated Site of the Méhtelek Group of the Early Neolithic Körös Culture in the Carpathian Basin. Edited by Nándor Kalicz. BAR IS 2321. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 113–30. [Google Scholar]

- London, Gloria A. 1989. On Fig Leaves, Itinerant Potters, and Pottery Production Locations in Cyprus. In Cross-Craft and Cross-Cultural Interactions in Ceramics (Ceramics and Civilization 4). Edited by Patrick Edward McGovern. Westerville: American Ceramic Society, pp. 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Maeir, Aren M., Louise A. Hitchcock, and Liora Kolska Horwitz. 2013. On the Constitution and Transformation of Philistine Identity. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 32: 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCown, Chester C. 1947. Tell en-Naṣbeh I. New Haven: ASOR. [Google Scholar]

- Mommsen, Hans, A. Kreuser, and J. Weber. 1988. A Method of Grouping Pottery by Chemical Composition. Archaeometry 30: 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nodarou, E., and Christina Rathossi. 2008. Petrographic Analysis of Selected Animal Figurines from Syme Viannou. In The Sanctuary of Hermes and Aphrodite at Syme Viannou IV. Animal Images of Clay = Toiero toy Erme kai tes Aphrodites ste Syme Viannoy IV. Pelinazodiac. Edited by Polymnya Muhly. Library of the Archaeological Society at Athens 256. Athens: Archaeological Society at Athens, pp. 165–82. [Google Scholar]

- Olyan, Saul M. 1988. Asherah and the Cult of Yahweh in Israel. Atlanta: Scholars. [Google Scholar]

- Otis Charlton, Cynthia L., and Thomas H. Charlton. 2010. Figurines in the Heart of the Aztec Empire. In Anthropomorphic and Zoomorphic Miniature Figures in Eurasia, Africa and Meso-America: Morphology, Materiality, Technology, Function and Context. Edited by Dragoş Gheorgiu and Ann Cyphers. BAR IS 2138. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 151–58. [Google Scholar]

- Panitz-Cohen, Nava. 2010. The Pottery Assemblage. In Yavneh I: The Excavation of the ‘Temple Hill’ Repository Pit and the Cult Stands. (OBO.SA 30). Edited by Raz Kletter, Irit Ziffer and Wolfgang Zwickel. Freiburg and Göttingen: Academic Press Fribourg, pp. 110–45. [Google Scholar]

- Press, Michael D. 2012. Ashkelon 4: The Iron Age Figurines of Ashkelon and Philistia. Final Reports of the Leon Levy Expedition to Ashkelon. Harvard Semitic Museum Publications. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, Patrick S. 2013. Ceramic Petrography. The Interpretation of Archaeological Pottery and Related Artifacts in Thin Section. Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Shachnai, Edith. 2000. Ramallah. Sheet 8-IV. Geological Map of Israel 1:200,000. Jerusalem: GSI. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, Arieh. 2007. The Soils of Israel. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Sneh, Amihai, and Yoav Avni. 2011. Sheet 11-II: Jerusalem. 1:50,000 Geological Maps. Jerusalem: Geological Survey of Israel. [Google Scholar]

- Sneh, Amihai, Yosef Bartov, and Marcelo Rosensaft. 1998. Geological Map of Israel. Jerusalem: Geological Survey of Israel. [Google Scholar]

- Sterner, Judith A. 1992. Sacred Pots and ‘Symbolic Reservoirs’ in the Mandara Highlands of Northern Cameroon. In An African Commitment: Papers in Honour of Peter Lewis Shinnie. Edited by Judith A. Sterner and Nicholas David. Calgary: University Press, pp. 171–79. [Google Scholar]

- Susnow, Matthew, and Naama Yahalom-Mack. 2023. Metalworking in Cultic Spaces: The Emergence of New Offering Practices in the Middle Bronze Age Southern Levant. Tel Aviv 50: 194–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissbein, Itamar, Yosef Garfinkel, Michael G. Hasel, Martin G. Klingbeil, Baruch Brandl, and Hadas Misgav. 2019. The Level VI North-East Temple at Tel Lachish. Levant 51: 76–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitbread, Ian K. 1986. The Characterization of Argillaceous Inclusions in Ceramic Thin Sections. Archaeometry 28: 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yellin, Joseph. 1996. Chemical Characterization of the City of David Figurines and Inferences about Their Origin. In Excavations at the City of David 1978–1985 Directed by Yigal Shiloh Volume IV, Qedem 35. Edited by Donald T. Ariel and Alon De Groot. Jerusalem: Hebrew University, pp. 90–99. [Google Scholar]

- Yellin, Joseph, and Jan Gunneweg. 1985. Provenience of Pottery from Tell Qasile Strata VII, X, XI and XII. Chapter XX1. In Excavation at Tell Qasile Part Two. Edited by Amihai Mazar. Qedem 20. Jerusalem: Hebrew University, pp. 111–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ziffer, Irit, and Raz Kletter. 2007. In the Field of the Philistines. Cult Furnishings from the Favissa of a Yavneh Temple. Tel Aviv: Eretz Israel Museum. [Google Scholar]

| Type | City of David (Y. Shiloh) | City of David (E. Mazar) | Ein Hamevaser | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Judean pillar figurines | 40 | 16 | 3 | 59 |

| Horse figurines (of these, horse and rider) | 13 (1) | 20 (3) | 0 | 33 (4) |

| Other zoomorphic figurines | 6 | 5 | 0 | 11 |

| Total | 59 | 41 | 3 | 103 |

| Aspect | Yavneh | Jerusalem |

|---|---|---|

| Samples analyzed | 107 | 103 |

| Types | Architectural shrine models, pans | Female pillar figurines, horse figurines |

| Iconography | Rich iconography with many themes; relatively naturalistic | Relatively standard, few themes, schematic depictions |

| Provenance | Locally produced 95%+ Few from distant sources | Locally produced 90%+ No evidence of distant sources |

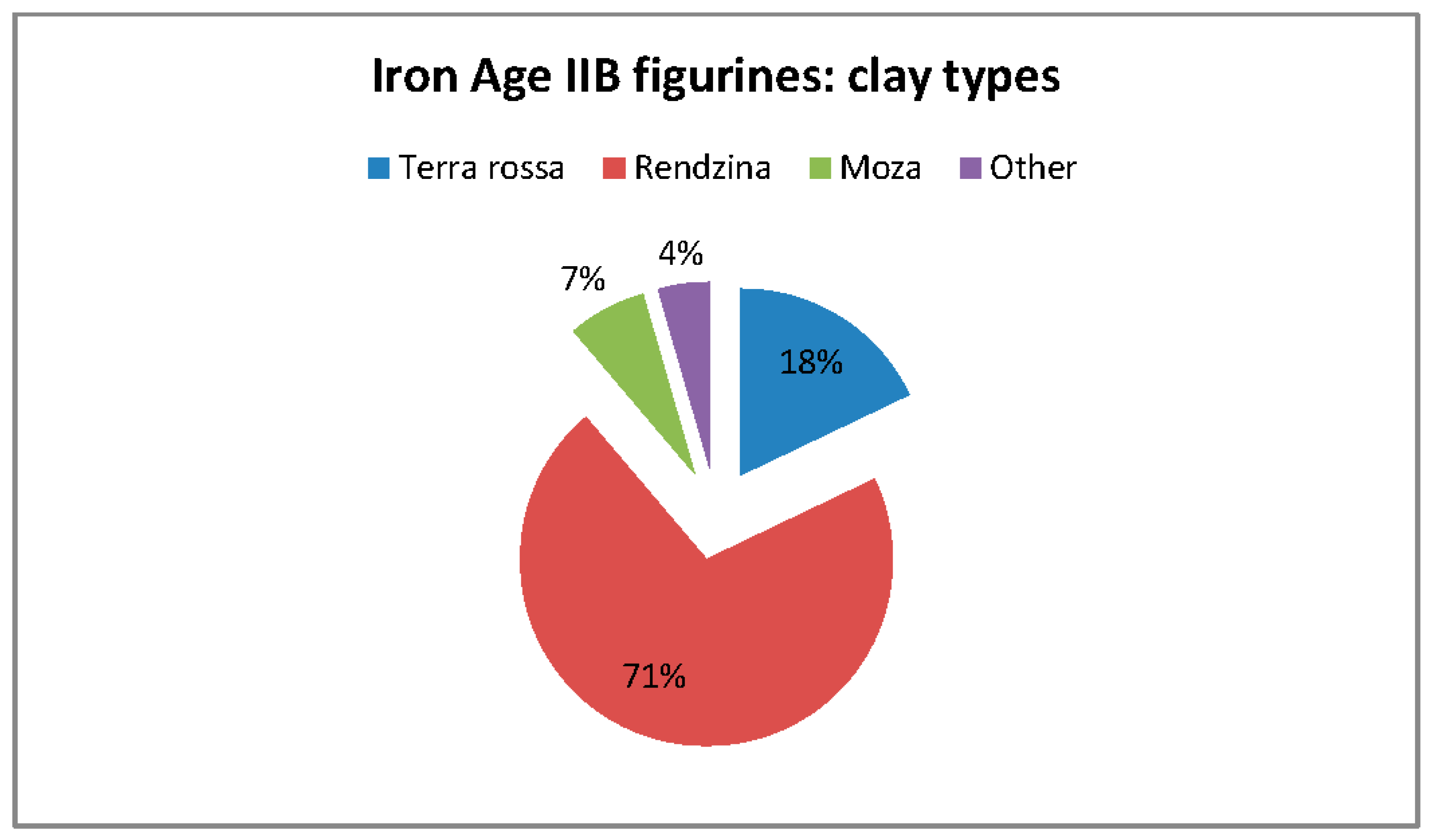

| Homogeneity (clay type) | Very high (ḥamra over 90%) | High (rendzina 70%) |

| Homogeneity (inclusions) | High | Low |

| Regional geological variability | Moderate | High |

| Tempering | Quartz, homogeneous | Calcareous, variable |

| Firing | Mostly high | Variable, usually relatively low |

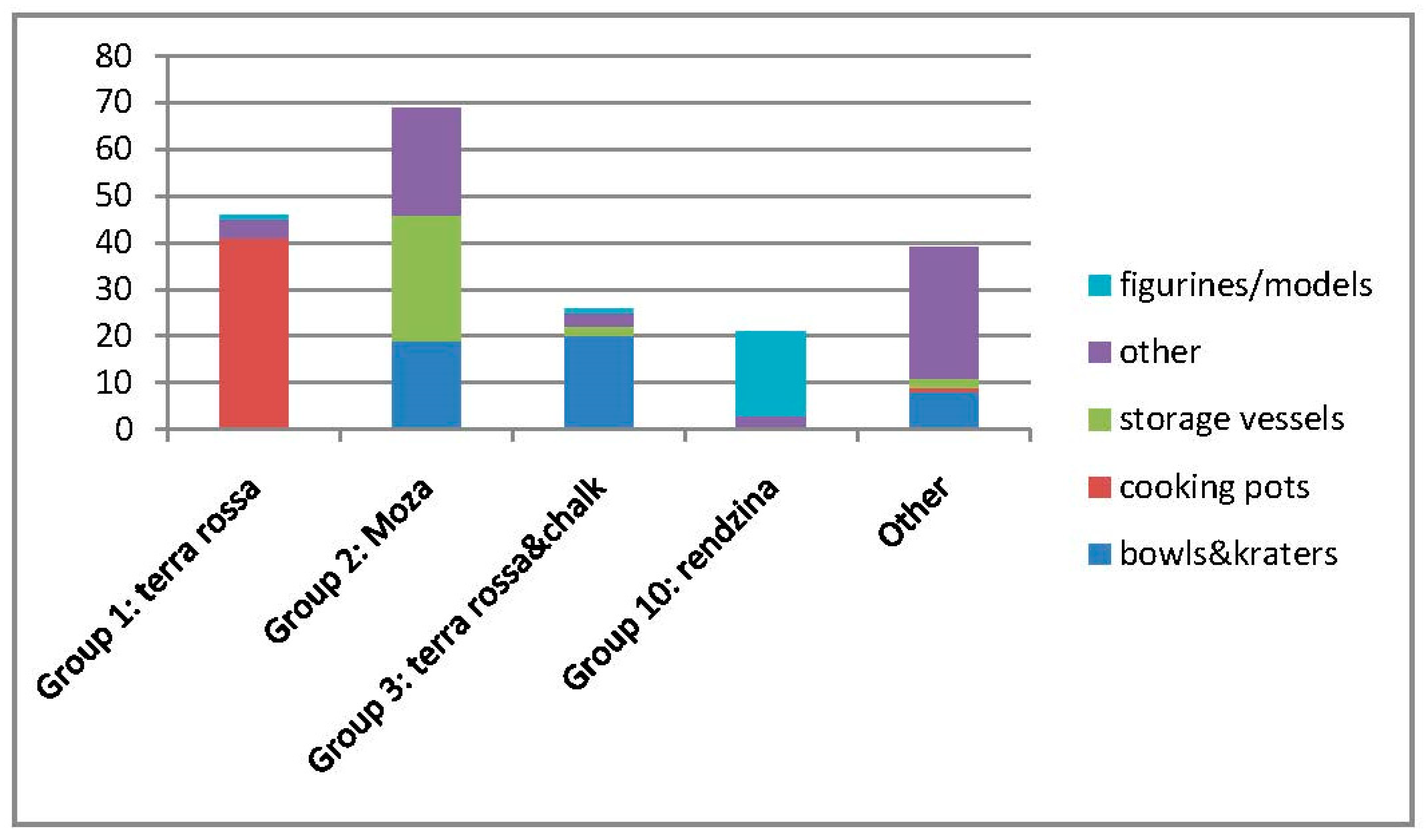

| Comparison to non-cultic pottery | Same production location and technique | Different production: same region, different clays |

| Interpretation: production mode | Single workshop (temple production?) high production control and standardization | Several workshops (household production?) or multiple potters |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ben-Shlomo, D. Compositional Analysis of Cultic Clay Objects from the Iron Age Southern Levant. Religions 2025, 16, 661. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16060661

Ben-Shlomo D. Compositional Analysis of Cultic Clay Objects from the Iron Age Southern Levant. Religions. 2025; 16(6):661. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16060661

Chicago/Turabian StyleBen-Shlomo, David. 2025. "Compositional Analysis of Cultic Clay Objects from the Iron Age Southern Levant" Religions 16, no. 6: 661. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16060661

APA StyleBen-Shlomo, D. (2025). Compositional Analysis of Cultic Clay Objects from the Iron Age Southern Levant. Religions, 16(6), 661. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16060661