1. Introduction

Generally, the first use of the expression “public theology” is attributed to

Martin E. Marty (

1974); and yet we cannot disregard the ecumenical book series

Theologia publica published since 1966, reaching the 14th volume by 1970. It was published by Ingo Hermann, Catholic theologian and radio journalist, together with Heinz Robert Schlette, professor at the University of Education in Bonn, Germany (

Pirner 2019b, p. 41). Then there are those who had engaged in public theology much earlier, without making use of the term, like M. M. Thomas (1916–1996) in the Indian context (

Moe 2024, pp. 88–95). We can safely affirm that, since the second half of the 20th century, public theologizing has evolved in varied ways, engaging progressively numerous intersecting perspectives and methodologies. On his part,

Pope Francis (

2023) recently urged theology to overcome its obsession with self-referential preoccupations and exit into the public square characterized by multiple types of diversity (religious, ethical, cultural, linguistic, social, political, economic, ecological, etc.) and contribute to a better world along with others engaged in the same venture. Instead of being reduced to another sector of theology, public theology transpires as a paradigm shift in theologizing as a whole that necessitates rethinking and widening of the entire field of reflection, research, and action with reference to diverse realms of human and ecological welfare. By exiting into the public sphere, theology then can lay bare its public significance.

A manifest challenge and opportunity for public theology in the Indian context is its time-honoured religious pluralism that touches every other sector of the public domain. Religions with their anthropological vision bound to the transcendent or immanent Reality can differ in their notion of human welfare and fulfilment. In effect, the three major religions in the Indian context, namely, Hinduism, Islam, and Christianity, approach human reality in diverse ways. We can then expect differences between Christians, Muslims, and Hindus in their approach to human development and common good, not only on the basis of their specific religious beliefs, practices, and socialization but also on account of their relative group size: according to the last available census of 2011, Christians (2.3% in India, 6.1% in Tamil Nadu) and Muslims (14.2% in India, 5.9% in Tamil Nadu) are minority groups, while Hindus (79.8% in India, 87.6% in Tamil Nadu) form the majority.

In the multifaceted Indian context, youth is a crucial category for the present and future of society. According to the National Statistical Office of India, the youth population, defined as those between the ages of 15 and 29, comprised 27.2% of the country’s overall population of 1.4 billion in 2021. This proportion is expected to decline to 22.7% by 2036, but the youth population is projected to still be large, around 345 million. It means that the welfare of Indian society is to a great extent determined by the education of youth who form about one-fourth of the population. Education of youth is a complex process that aims at their integral human development, encompassing religious, cultural, socio-political, and economic formation, and empowers them to be active agents of their own wellbeing and that of society at large.

The educational process that aims at the human development of the young in various sectors of the public domain cannot ignore the challenges and opportunities posed by religious diversity. Here our focus is on Salesian/Christian educational institutions. In effect, since its origin Christianity has witnessed its faith through diverse forms of service to those in need. Religious orders and congregations and Christian lay associations and movements articulate their service (ministry) in the public square on the basis of their charism inspired by the Spirit of God. According to

Pope John Paul II (

1998), charism and ministries are inspired by the Holy Spirit, with the variety of charisms corresponding to the variety of services (ministries). In this sense, Salesians, the religious congregation founded by St. John Bosco (1815–1888), popularly known as Don Bosco, display the charism of educating the youth. On the basis of his own experience among youth in Turin, Italy, Don Bosco developed a religious pedagogy, which he presented as a “preventive system” in 1877 as opposed to the then prevalent “repressive system”. In the contemporary multireligious Indian context, the question that arises is whether people of “neighbour religions”—an expression assumed by the Federation of Asian Bishops’ Conferences (

FABC 2023) in the place of “other religions”—namely, Hindus and Muslims, can share the Salesian pedagogy, namely, the methodology of Salesian educational engagement. It is our contention that the prism of public theology can shed some light on such a possibility.

With this intent, we first elucidate the configuration of public theology amidst religious pluralism, focusing successively on public practical theology of education, public religious education, and public religious pedagogy. This is then followed by a synthesis of Salesian pedagogy and the research design of a qualitative study on its lived experience among Hindu and Muslim colleagues in educational engagement, namely, professors in Salesian colleges, teachers in Salesian schools, and collaborators in Salesian social service centres involved in education of the young in Tamil Nadu, India. Lastly, based on the emerging findings we highlight the relevance and advancement of Salesian pedagogy as public religious pedagogy.

2. Multiple Perspectives of Public Theology

The debate over the years has identified public theology as a theology intelligible, assessable, and convincing to those inside the Church and those outside in the public square. “Public” here refers to that which is available to all intelligent, reasonable, and responsible members of a society despite their religio-cultural differences. Public theology should then be capable of persuading and moving to action both followers of Christian and neighbour religions. In other words, public theology stands for how faith is accessible and accountable to the public; how it contributes to the public sphere of common good. As a theology focused on humanizing goals, it should encourage humanizing actions and challenge dehumanizing trends; with its ability for reason, debate, and consensus it should engage in public discourses that reinforce transformative processes. In a way, it adds to the public debate, to the vitality of a democratic society (

Himes and Himes 1993, pp. 1–27;

Breitenberg 2010, pp. 3–17).

2.1. Theology “Ad Intra” and “Ad Extra”

Theology ad intra has a centripetal focus of gathering everyone into the Church, the Universal Sacrament of Salvation, and making available the divine revelation and God’s offer of eschatological salvation. As such, theology is concerned with the comprehension and progressive realization of the Reign of God. In its evolution, theological tradition has gradually differentiated its various branches assuming specific methodologies: scriptural/biblical theology with its literary method of textual and inter-textual analysis providing the basis for ecclesial faith; systematic/philosophical theology with its analytical-critical method of seeking ever deeper and coherent comprehension of ecclesial faith; historical theology with its historical-critical method focused on the diachronic development of ecclesial faith and life; and practical/pastoral theology with its hermeneutical and empirical-critical method attentive to the ongoing synchronic development of ecclesial life and praxis.

The paradigm shift that is called for in these intersecting branches of theology stems from the “glocal” (global–local) nature of theologizing and accordingly reviewing the epistemologies and methodologies with reference to the public sphere. That is, in the academic sphere the envisioned paradigm shift induces a theological advancement in terms of public scriptural theology, public systematic theology, public historical theology, and public practical theology (cf.

Jacobsen 2012;

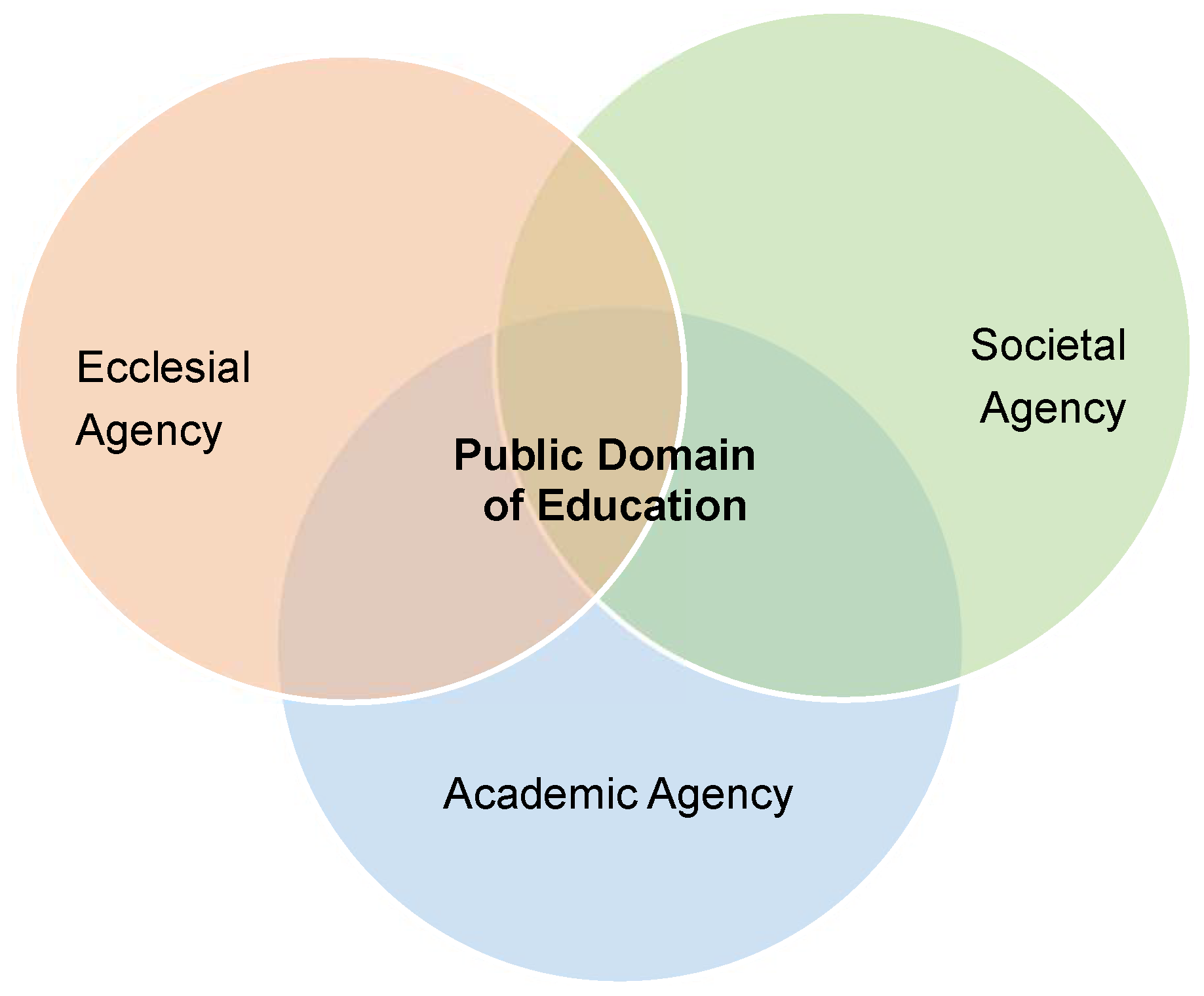

Day and Kim 2017). Such public theologies engage not only the academic agency but also the ecclesial and societal agencies (see

Figure 1). In other words, public theology is conceived in the Church, critically developed in the academy, and co-generated in conversation with society at large, using the public criteria of rationality (

Peters 2018).

In this vein, public scriptural theology with its literary method traces the source of Christian tradition beginning with the Aramaic, Hebrew, Greek, Latin, and Western linguistic and cultural underpinnings. While scriptural/biblical theology, with its textual and intertextual analysis, delves into the origin and development of Christian tradition shaped by these linguistic and cultural resources, the public theological shift would require recognizing how neighbour religions’ scriptures/religious literatures (Vedas, Agamas, Quran, etc.) embedded in their own languages and cultures inspire their believers and contribute to human flourishing (

Patrick 2023, pp. 222–25). Public theological thrust would also entail engaging religious and non-religious literatures of local and foreign languages in the process of shaping and representing human fulfilment and common good.

Although systematic/philosophical theology—with its analytical–critical method—aims at the universal understanding of Christian faith, its development is marked by the contribution of contextual linguistic–philosophical traditions in which Christianity had taken root. The question that arises now concerns the extent to which languages, philosophies, and cultural context of contemporary local churches in Latin America, Africa, Asia, and Oceania can actually shape or should shape the development of public systematic/philosophical theology, taking stock of local religious and anthropological visions. In its search for the ultimate truth, public systematic theology must likewise dialogue with the scientific world, particularly with natural sciences. Forming an integral part of this sector of theology are the public fundamental theology with its apologetic intent and public moral theology with its ethical concern. These can contribute to human wellbeing and social welfare, taking into consideration the plurality of religious and secular worldviews and values (cf.

Peters 2018,

2021;

Jacobsen 2012).

Likewise, public historical theology, with its historical–critical method, has to trace the development of Christian tradition with its internal divisions and external conflicts amidst religio-cultural pluralism. Although it has been contributing to common good and human development, Christianity’s historic links with imperialism and colonialism through the centuries cannot be ignored and which now would call for its commitment to a new world order through planetary decolonial theology (

Balasuriya 1984). In his recent letter on the study of Church history,

Pope Francis (

2024) bemoans the absence of historical awareness in the Church and in civil society and appeals for a participatory knowledge of history as fathoming the past can lead to transforming the present, overcoming ideological distortions. It is evident that Church history cannot be disconnected from the “glocal” history of peoples and nations.

Since our research study is focused on the academic sphere of public practical theology, in the pluralistic context, we shall elaborate on these in the following two subsections.

2.2. Public Practical Theology

With its hermeneutic dynamics of praxis–reflection–praxis, practical theology is already in tune with public theology (

Graham 2008). In the case of practical theology,

ecclesial praxis has to be understood in association with the underlying

Christian praxis shared by other denominations, and, in turn, with the underlying

religious praxis shared by diverse religious traditions, encompassing as well the underlying

human praxis common to non-religious or secularized persons. In other words, as its material object, practical theology is focused on the continuum of ecclesial–ecumenical–religious–human praxis with mostly

ad intra concern for transforming the Church and thus building up the Reign of God (formal object) (

Midali 2011b). In this vein, public practical theology with its interrelated view of ecclesial–ecumenical–religious–human praxis, but with a more

ad extra concern, seeks to promote the humanization of society as a sign of God’s Reign of peace and justice (

Peters 2018, pp. 160–62;

Dal Corso and Salvarani 2020;

Dal Corso 2022). Evidently, in humanizing society, the Church too acquires its authenticity, transforming its praxis ever more into authentic human action. Authentic human action is already Christian, just as Christian praxis is genuine when it is also authentically human.

In this vein, public practical theology seeks to transform current society along with other local religious and non-religious traditions by contributing in a collaborative manner to common good, human dignity, human rights, and human responsibility (

Himes and Himes 1993, pp. 16–17). Public practical theology, therefore, assumes the empirical–critical method that can engage the three agencies of public theology, namely, ecclesial, societal, and academic (see

Figure 1). Insofar as an individual’s agency comprises cognitive, affective, and operative dimensions, and societal reality encompasses religio-cultural, socio-political, and economic–ecological features, we can speak of intellectual (mental, emotional, spiritual), physical (health), psychological, cultural (linguistic, musical, aesthetic, etc.), social (relational, communicational), environmental, and economical/financial (occupational) welfare as the pursuit of public practical theology (cf

Aziz 2022;

Dreyer 2004).

As mentioned above, the material and formal objects of public practical theology necessitate the empirical–critical method of research that can engage the three agencies: ecclesial, societal, and academic. Intra-disciplinarity, i.e., assuming an empirical method in theology (analogous to incorporating literary, semiotic, philosophical, historical, archaeological, and other methods), enables appropriate interdisciplinarity with other human and natural sciences such as cultural, social, juridical, political, economic, biological, and ecological studies. In its turn, an interdisciplinary approach can enable a transdisciplinary (meta-disciplinary) focus on public aspirations of common good, human wellbeing, and environmental care. In this sector of public practical theology, we can situate the discipline of public spiritual theology aiming at physical, mental, relational, and spiritual wellbeing with its openness to mindfulness, zen, yoga, holotropic breathwork, etc. (

Grof and Grof 2010). Likewise, with reference to the public domain of education, we can associate public practical theology—as we shall see further below—with public theology of education and public religious pedagogy. But before that we shall briefly examine public theology amidst multiple pluralism.

2.3. Public Theology in the Pluralistic Indian Context

Public theology is essentially contextual in that it is determined by the situational factors of religious traditions: their being native or migrant, their having a minority or majority status, their historical development, and their resilience to globalization. Public theology of a native religion like Hinduism in the Indian context is quite different from that of a deterritorialized or migrant religion like Christianity in India. As the core of the local context, a native religion flourishes spontaneously in reciprocal interaction with other subsystems: cultural–linguistic, socio-political, and economic–ecological. Its relationship is like a natural bond between soul and body. For this reason, the public theology of Hinduism rooted in all the spheres of life through local languages is a natural occurrence. In other words, native religion has a natural propensity for public theological discourse in its context. A non-native or deterritorialized religion, like Christianity, has the difficult task of gradually entering the various spheres of local life, aware that it has been expressing itself in other subsystems inherent to its own origin and evolution. Of course, through native Christians the deterritorialized Christian tradition can become credible and meaningful to the extent it empathetically and critically engages the various spheres of life. Local language as an abstract representation of values and visions of these spheres is pivotal to Christian public theological discourse.

In order to contribute to common good in terms of public theology, deterritorialized Christianity, with its own culture of origin and historical development, will have to engage in the process of inculturation, interculturation and conculturation (

Anthony 1997, pp. 42–48). According to Ignatius Hirudayam SJ (1910–1995), who coined the term,

conculturation refers to the ability of Christianity to insert itself in a new culture so deeply that it is capable of contributing to the further development of local culture, together with other agencies and stakeholders of the local society, and consequently shape the other subsystems. A non-native Christian religion in this process can also play a disruptive and creative role in furthering the growth of local culture and society. At the same time, Christianity itself can make its creative advancement by engaging in dialogue with native religions that nourish the local culture.

Since public theology implies a “glocal” perspective, conculturation must be viewed in connection with interculturation, moving towards transculturation. On the one hand, public theology must emerge as the “lived theology” of those engaged in conculturation, a common engagement for the transformation of the local societal situation favouring human flourishing. On the other hand, non-native religions have to attend to diachronic and synchronic interculturation to maintain unity in diversity and be “glocally” relevant. In the case of a non-native religion, its public theology would show more hospitality received rather than hospitality offered in recognizing the sources of truth. This imposes not only interdisciplinary but also inter gentes dialogue based on the lived theology of people with their own specific religio-cultural identities. In addition, as cultures constantly evolve, public theological discourse evolves with intergenerational dialogue as well.

There is no gainsaying that the public significance of a religion is also determined by its majority or minority status. Obviously, a minority religion can play the role of a critical minority. In the historical development of Christianity up to the 4th century, it was a minority migrant religion in Europe, but during the next seventeen centuries, it progressively became a dominant presence. In the Indian context, up to the 15th century Christianity was a migrant marginal religion; but since then, although still a minority religion, it has been associated with the dominant colonial powers. This implies that public theology in the Indian context has to be a decolonial theology.

The contemporary milieu of globalization, modernity, and post-modernity has its impact on religion. Religion in such a secularized context appears to be outdated and reduced to the private sphere. In the context of separation between state and religion, civil society is the public sphere where individuals or non-governmental organizations can discuss issues of collective relevance of values and norms. Religions can use this public space to propose their worldviews, norms, and values. Religious praxis can combine “the material dimensions of social, economic, and human capital with other resources of metaphysical beliefs, ethics, and attitudes” (

Graham 2019, p. 17). In effect, religions can potentially represent an answer to the societal quest for common goals and shared values. To play such a role, according to Habermas, in the first place, religion is required to accept and tolerate the societal presence of various cohabiting confessions and religions; secondly, religion must acknowledge the rationality of arguments as a form of discussion; and thirdly, religion is obliged to obey propositions of the constitutional state (

Ziebertz 2011, pp. 14–15;

Habermas 1992;

Palmentura 2022). Likewise, by engaging at three levels of ethical discourse, i.e., meta-ethical, normative ethical, and legal ethical (

Magni 2011), public theology can become intelligible and assayable to all in local and global society.

3. Public Practical Theology of Education: Religious Education and Religious Pedagogy

Although the terms “education” and “pedagogy” are at times used as interchangeable synonyms, there is a subtle and significant difference between the two. Yet they cannot be considered as totally disconnected concepts as they to some degree involve each other. The etymological root of pedagogy takes us to the Greek terms

pais or

paidos (child, boy) and

agōgos (guide, caretaker), referring to the function of

paidagōgos, namely, of the slave or adult who had the task of accompanying the young to the gymnasium or school (

Nanni 1997b). “Pedagogy” thus points to the educator and his/her task or art of forming and leading the young. On the other hand, “education” deriving from the Latin

educere (drawing out, developing) or

educare (cultivate, raise) can be understood to focus on the whole process of drawing out the potential or nurturing the multifaceted growth of the young (

Nanni 1997a). This distinction and overlap are pertinent to what is emerging as public practical theology of education encompassing public religious education and public religious pedagogy.

3.1. Emerging Public Practical Theology of Education

In the academic sphere during the second half of the last century efforts were made to shape a theology of education. Already from 1945 theology of education appears as a distinct university discipline in what was then the Salesian Pontifical Athenaeum, Rome. Discussion and debate in the following years resulted in an ever-precise elaboration of its rationale and method. The theological nature of this discipline is founded on the scriptures and the faith-tradition of the Christian community. Given the focus on education, it necessarily involves interdisciplinary dialogue with educational sciences in drawing the ultimate significance of human activities—specifically of educational activities—for human development and wellbeing. It highlights the humanizing function of education (

Groppo 1997). Such an orientation is already in tune with the concept of public theology of education. At this juncture, we cannot ignore the fact that Jesus, the central figure of Christian faith, lived out his entire life in the public domain—i.e., in the religious, cultural, social, political, economic, and environmental spheres—from his birth in an abandoned grotto to his tragic death on the cross outside the city walls. In other words, the four gospels attest to the public life of Jesus, seeking to transform every sector of the public domain, embedding integral human wellbeing in the eternal good (

Hughson 2013). Following this Christological archetype and the charism inspired by the Spirit of God, some religious orders and congregations and Christian lay associations and movements articulate their service (ministry) in the public domain of education.

Besides the initial work of

Martin E. Marty (

2000), the international and interdisciplinary conference on “Public Theology—Religion—Education” held at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, Germany, in 2016, marks an important milestone in the direction of public theology of education. The discussion revolves around three fundamental approaches to the educational domain. First of all, as

Manfred L. Pirner (

2019a, pp. 1–4) sums up, in the contemporary democratic world, there is the need for educating those affiliated to religious and other secular traditions to promote common good and human welfare, namely, a humane society founded on human rights and responsibilities. Secondly, education itself is a matter of public theology insofar as the right to education is a basic human right, vital for the functioning of democracy. Significantly, the educational institutions affiliated to religious traditions generally have paid particular attention to the lower rung of society, contributing thus to the welfare of individuals and of society at large. Thirdly, religious and moral/value education in public institutions affiliated to religions and religious studies or ethics in public state institutions mark a specific feature of public theology of education, insofar as these courses aim at contributing to common good and peaceful co-existence. These perspectives vital to public practical theology of education converge on public religious education and public religious pedagogy.

3.2. Towards Public Religious Education

As in the ambit of neighbour religious traditions, educational institutions, like Christian schools, were established to cater to the faith formation of the younger generations. In effect, Christian faith education in schools aims at accompanying Christian students through various stages of faith maturation and moral development. The young are taught to grasp the Christian message, celebrate their faith meaningfully, and witness to it through their love for others and their service to the needy. In this vein, extracurricular activities for

enfaithing include moments of prayer, reading of scriptures in assemblies, celebration of feasts, days of reflection, retreats, etc. For the progressive qualification of teachers, in-service formation programmes are also offered: for example, Professional Approach to Christian Education (PACE) as in the Salesian schools of Tamil Nadu. In these Christian schools and colleges, besides the faith education courses for Christian students, ethics/value education classes are provided for those belonging to neighbour religions. With reference to the latter, it is proposed that the wisdom literature in the Bible and in the neighbour religious and cultural traditions (like the classical

Thirukural in the context of Tamil Nadu) could be integrated as shared wisdom offering insights for daily life (

Kim 2019). With the view to engage in such ethics/value education, in-service formation programmes such as Professional Approach to Value Education (PAVE) are offered by the

Deepagam (

2024), the catechetical centre of the Salesians in Chennai.

With the changing shades of religious pluralism and secularism, Christian education cannot ignore the denominational and religious differences among students. Therefore, the preoccupation of transmitting one’s own religious tradition has to be situated within a complex framework of integral human maturation exploring the specific function of religion with reference to the wider universal search for truth (

Trenti 1997). As in some Western countries, religious education elucidates different religious traditions according to the identity of the student population that frequents public schools. It can also be an instruction

about religious traditions rather than instruction

in one’s own religion, for inspiring peaceful and dialogical coexistence based on a pedagogy of difference (

Alexander 2019). At higher levels of schooling and academic pursuits, it takes the shape of religious studies, entailing description, critical analysis, and understanding of religion as a phenomenon without implying the faith of educators or students. In some traditionally Christian countries secondary levels of schooling not only include knowledge about the Scriptures, doctrines, and history of Christianity but also about world religions: their history, myths, festivals, sacred places, belief systems, ethics, spirituality, etc. In other words, a scientific approach that promotes critical understanding and respect for religious and denominational pluralism and secular ideologies. Taking a critical approach to transmitting religio-cultural content, religious studies also seek to establish scientific dialogue: between religion and other disciplines, between one’s religion and neighbour religions or ideologies, and between studied religion and lived religion (

Hull 1987;

Pajer 1987). These trends in religious education and religious studies are in line with what is emerging as public religious education, already advocated by German systematic theologian Sigurd Daecke in 1970 (

Pirner 2019b, p. 41;

Grümme 2019). As

Manfred Pirner (

2019b, p. 49) suggests the scope of public religious education is “to help young people find orientation and develop competence in matters of religion, worldview, and ethics—irrespective of their own present belief or disbelief”. In other words, public religious education addresses both believers and non-believers of religious traditions and explores the implications of religious beliefs, without the need to share them or practice them.

According to

Bruce Grelle (

2019) secular academic study of religion in public schools, colleges, and universities can contribute to the common good and human welfare. The aim of public religious education is to make students aware of the diversity of religious traditions and learn about them, as distinct from faith-based religious education. It contributes to religious, cultural, historical, and civil literacy, clarifying the basic beliefs, aesthetics, and practices of world religions, and how they have promoted literature, art, music, philosophy, law, ethics, politics, human rights and responsibilities, and ecological sensitivity. In effect, understanding religious and secular worldviews can help in responding to the contemporary crisis of sustainability and justice. Likewise, alternative worldviews and values can help students to be self-critical of their assumptions about the meaning and goals of their life, and their rapport with others and the surrounding nature, stimulating ecological and moral imagination. Moreover, world religious traditions stipulate specific dynamics of human and ecological wellbeing: meditation, mindful breathing, yoga, prayer, chanting, etc., leading to mystical experience and transformation of consciousness. In this way, helping the young to mature as committed citizens pursuing the common good amidst multiple types of diversity calls for the intertwinement of religious/worldview education, human rights education, and citizenship education, combining respectively the sacred, the just, and the civic, in the educational process (

Miedema 2019).

3.3. Towards Public Religious Pedagogy

Religious pedagogy, as educational methodology, can be distinguished from the academic subject of religious education/studies. Pedagogy, as we mentioned above, focuses on the art and task of the educator: engaging in the varied sectors of curriculum (explicit, implicit, hidden, and null curriculum), employing teaching methods, setting educational goals, activating the style of relationality with students, creating a learning environment, etc. In this vein, religious pedagogy can be understood as the religious dimension that shapes the whole process of education, not just religious education/studies. While the official explicit curriculum of the school or college is set by the government educational policy, the extracurricular activities and hidden curriculum (the style of engaging the students and the configuration of the overall environment) are defined by the institutional policy and pedagogy. Through the specific resources of various sectors of the educational curriculum and by employing appropriate teaching methods, educators aim at shaping the young to be self-reliant and competent in contributing to the common good, aware of their human rights and responsibilities. This is what we mean by public religious pedagogy.

“Public Religious Pedagogy can be distinguished from Religious Pedagogy in that the former is a discipline that represents a broader outlook and does not focus exclusively on school and educational matters but is intended to provide more concrete recommendations with regard to social issues” (

Platow 2019, pp. 122–23). In other words, public religious pedagogy goes beyond didactic contents, methods, and media and beyond the explicit educational curriculum of schools and colleges to include style or system of governance, general public religious tenor, environmental care, etc. (

Platow 2019, pp. 129–30). Public religious pedagogy, with its inclusive approach to education, would aim at rendering the religious, cultural, and social differences a source of enrichment rather than barriers of isolation or conflict. It makes space for intercultural, interreligious, and ecumenical learning embedded in the life-world of students (

Schreiner 2019;

Anthony et al. 2014;

Lourdunathan 2022). It underscores the close link between religious education and citizenship education, highlighted by the traditional formula of forming “good Christians and honest citizens”. From the perspective of public religious pedagogy, it means that nurturing the young to be a good Christian or good religious person necessarily requires that he/she at the same time be equipped to be a generative and responsible citizen (

Gearon 2019;

Anthony 2013).

If public religious pedagogy aims at forming mature citizens, aware of human rights and responsibilities, such a pedagogy and institutional policy cannot ignore that education itself is a basic human right. In other words, educational justice has its relevance for public religious pedagogy and institutional policy. Option for the poor and the marginalized in society, with the view to overcoming social inequality and enabling equal opportunities and participation, social coherence, inclusivity, and human flourishing, have to be viewed as integral to public religious pedagogy. This can find expression in supporting educational initiatives such as study centres and skill development programmes aimed at the underprivileged (

Grümme 2019).

Pedagogy is a question of leading and moulding young leaders. Empirical research suggests that discernment competency, spiritual determinants, and situational contingencies shape educators in being transformational leaders (

Anthony and Hermans 2020;

Hermans and Anthony 2020). Making young transformational leaders in their turn can be viewed as a vital feature of public religious pedagogy. In the educational environment leaders emerge and function in groups, amidst both in-group and out-group relations. Forming the young to be leaders is more than just a transfer of skills, even more than shaping leadership traits and behaviours. It encompasses developing hermeneutic competence, critical competence, moral competence, collaborative competence, and technical competence (

Fourie 2019).

With reference to the overall educational environment, public religious pedagogy can also be grasped from the image of ethics displayed in schools and colleges. Images can be grasped in the dialectics of revelation and concealment, presence and absence, presentation and withdrawal. As the name and image of God can be misused to justify war and conflict, as well as possessing the truth to feel superior over neighbour religions, it is crucial to acknowledge the unavailability of the divine and refrain from sanctifying images of one’s own religious tradition. Obviously, goodness, truth, and beauty are not opposed to images but to a specific one-sided use that overlooks the unavailability or transcendence of the Sacred or the divine Reality. The educational effort is to help see “images as images” in the public educational domain. Obviously, images can also have a positive impact to overcome stereotypes, to see others and the context differently. The impact of images can also refer to the dynamic change of human beings, inspiring new beginnings, pointing to memory and new possibilities, e.g., images of reconciliation (

Höhne 2019).

In the current digital world, the learning potential of digital media in religious education cannot be ignored, for the internet brings people into contact in the public domain. Given the digital divide, public digital theology should be conceptualized as a theology of presence, as well as of absence, addressing the power structures that lead to exclusion. A religious pedagogy in this context would have to consider the interdependency of connectivity and reflexivity (

Simojoki 2019).

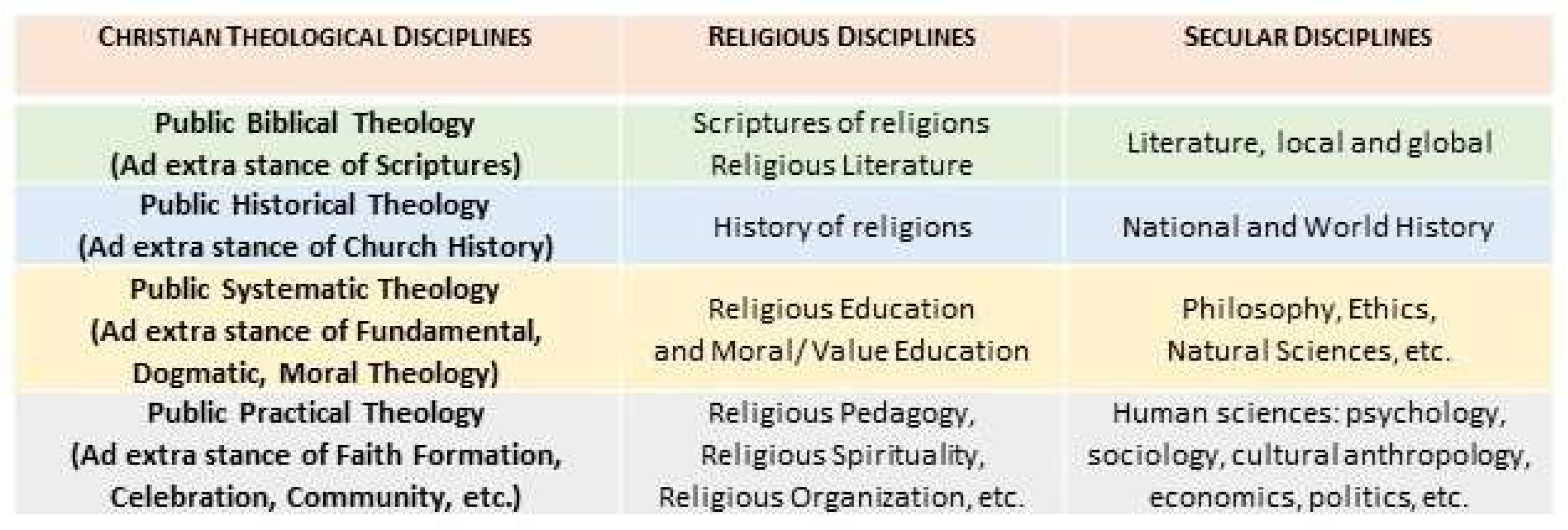

At the close of our discourse on public theologizing in the four sectors of public biblical theology, public historical theology, public systematic theology, and public practical theology, and the elaboration on public practical theology of education encompassing public religious education and public religious pedagogy, taking the cue from

Gavin D’Costa (

2005, p. 53), we postulate how the distinct orders of theological, religious, and secular disciplines can be viewed in an interrelated fashion (see

Figure 2). Public theology demands a constant interdisciplinary openness and dialogue between these three sets and levels of disciplines, each with its own specific assumptions, objects, and methods. To engage in this process, theologians must also grasp the worldviews and value systems underlying neighbour religious and secular traditions, having some grounding in social, human, and natural sciences. This warrants a genuinely plural voice in the public square, ensuring intellectual freedom, exchange, and excellence, with transdisciplinary convergence on truth, love, harmony, beauty, human wellbeing, and ecological flourishing.

4. Salesian Pedagogy in the Perspective of Public Religious Pedagogy

For over a century and a half, Salesian pedagogy originating from the educative–pastoral experience of Don Bosco has found expression in the educational and social engagement of Salesians and Salesian Sisters (members of the Catholic religious congregations founded by him) and lay Christian co-operators and collaborators (

Braido 2009). In the Indian context, since the arrival of Salesians of Don Bosco (SDB) in Tanjore, Tamil Nadu, in 1906, a growing number of persons affiliated with neighbour religions, principally Hindus and Muslims, render their qualified service as professors and teachers in Salesian educational institutions and as collaborators in Salesian social action centres of supplementary education at the service of the poor and marginalized youth. Most of the young beneficiaries also belong to neighbour religions. The question that we address in this research study is whether Salesian pedagogy functions as public religious pedagogy, allowing Hindu and Muslim educators and collaborators to engage in it for promoting the integral development of the young.

According to

Pietro Braido (

1997,

1999) and

Michal Vojtáš (

2021), who researched the origin and development of Salesian pedagogy, respectively, the “preventive system” of Don Bosco as opposed to the “repressive system” is founded on three operational principles of religion, reason, and loving kindness, along with the animating and preventive presence of the educator among the young. Being a religious pedagogy, in nurturing the growth and maturation of the young, educators are to appeal to Christian/religious worldviews and values and make them grow in these through education. As a pedagogy of reason and reasonableness, it requires that educators rely more on reasoning than on punishment while correcting or stimulating the young to grow in their human and spiritual potentials and responsibilities. And above all, as a pedagogy of love, the dealings with the young are to be a manifestation of educators’ concern, kindness, and friendliness, ensuring a family atmosphere of freedom, trust, joy, and wellbeing. For Don Bosco it is enough that a person be young to deserve educators’ kind attention, particularly if the young person is poor and marginalized. It is by making a preferential choice for the last and the least that one can be open to all youth. Given the reciprocity that love implies, Don Bosco would encourage educators not only to love the young but also to learn to be loved and be esteemed by them, rather than be feared.

The overall scope of Salesian educational engagement is stated in the formula assumed by Don Bosco: forming “good Christians and honest citizens”, a formula that can be traced back to the introduction of pastoral/practical theology as a discipline in the University of Vienna in 1774 by the Benedictine monk Franz Stephan Rautenstrauch (1734–1785) under the solicitation of Queen Maria Therese of Austria (

Midali 2011a, pp. 22–25). It implies a fundamental commitment to civil society and its welfare fostered by generative and responsible actions: generative in the sense of creative and transformative actions; responsible in the sense of conscientious and altruistic actions. From a public practical theological perspective, we might say that the educative task of nurturing good Christian/religious persons is bound to making them generative and responsible citizens; without the latter, the former would lose its credentials (

Anthony 2013). As Elaine Graham put it: the intent is to forge “powerful and sustainable bonds between the practice of faith and the exercise of citizenship” (

Graham 2019, p. 23).

To explore the rapport between Salesian pedagogy and human rights, an international conference on

Sistema Preventivo e Diritti Umani (Preventive System and Human Rights) was organized in 2009 in Rome. In effect, Salesian pedagogy proffers an educative perspective on human rights, not only to defend the rights of the young and their right to education but making them sensitive to human rights and responsibility and in this way contribute to societal welfare both locally and globally (

Carazzone 2009;

Muñoz Villalobos 2009;

Villanueva 2021). In this vein, empirical studies have also been undertaken among Christian, Muslim, and Hindu school and college students in Tamil Nadu, India, on their attitudes towards the various categories of human rights as part of two international research projects, “Religion and Human Rights” (2005–2011, 2012–2023), with a series of publications. The aim was to verify the impact of religious beliefs, religious experience, religious practices, religious socialization, function of religion, approach to religious pluralism, etc. on students’ attitude and advocacy of human rights. Just to mention few pertinent examples: civil rights related to privacy, speech, assembly, religion, discrimination, and inhuman treatment (

Van der Ven and Anthony 2008); socio-economic rights concerning work, social security, wages, leisure, recreation, and education (

Anthony and Sterkens 2020); ecology and human flourishing (

Anthony 2023a); and state–religion separation amidst religious pluralism (

Anthony 2023b).

The objectives of Salesian pedagogy, described above, are generally specified in each institution’s vision and mission statements. For example,

Sacred Heart College (

1951)—Autonomous, Tirupattur one of the institutions participating in the present research—states its vision in these terms:

“We, the community of Sacred Heart College, inspired by the love of the Heart of Jesus and fundamental human values, following the educative system of Don Bosco, are committed to the creation of an educated, ethical, and prosperous society where equality, freedom and fraternity reign by imparting higher education to poor and rural youth which enables them towards integral human development”. This is to be achieved through academic excellence, healthy standards in extracurricular activities, socially relevant research, and an educational process that leads to employment and entrepreneurship. As mentioned, the college seeks to serve preferentially the underprivileged and rural youth, making them consciousness of their rights and responsibilities, to overcome social evils and build up healthy communities. Through the educational process the college strives to uphold core values such as primacy of God, honesty, respect for all, being responsible, and particularly pursuit of excellence in the academic sectors of arts (Tamil, English, economics, commerce), science (mathematics, physics, chemistry, computer science, business management), and skill programmes (communicative English, life skills, placement).

Similar vision and mission statements, based on Salesian pedagogy, are also expressed by

Assam Don Bosco University (

2008) and by the network of Salesian Institutions of Higher Education (

IUS Network 1997).

Besides formal educational institutions such as schools, colleges, and universities, Salesians also operate supplementary educational centres as a support strategy. One such organization is the Strategic Urban Rural Advancement Backing Institute (

SURABI 1988), a registered NGO of the Salesian Province of Chennai for holistic education, skilling, and empowering projects and programs. The projects include evening study centres for children and skill training and environmental awareness programmes for youth. In addition, programmes are also designed for women, farmers, and vulnerable communities. SURABI is of the view that education is the most effective tool for helping children to free themselves from the vicious cycle of ignorance, poverty, and environmental degeneration. It addresses the needs of the children both in rural and urban slums, with initiatives such as supplementary education and scholarships. Eight of these evening study centres were included in our research, besides five schools and four colleges of the Salesian Province of Chennai, Tamil Nadu.

5. Empirical Approach to Public Religious Pedagogy: Research Design

Theology of education offers the anthropological and Christological basis and perspectives for Christian educators, whereas public theology of education points to the religious experience underlying the educational engagement of Christians and of neighbour religions. In this vein, we examine the lived pedagogical experience of Hindu and Muslim professors, teachers, and collaborators in the public sphere of Salesian educational institutions. Such a lived experience of Salesian pedagogy is personal and autobiographical in nature, and as such, it is intersubjective, engaging aspects of institutional pedagogy and policy. We may describe it as the theological reflective horizon associated with personal and communal lived experience in the educational service, an instinctive theological–educational interpretation of one’s life situations and commitments (

Francisco and Cornelio 2022).

As highlighted earlier, in accordance with the scope of Salesian pedagogy, educators aim at the human development of the young, namely, their intellectual, physical, spiritual, and all-round growth, with the intent of building up society in terms of social, political, economic, and ecological welfare. In Salesian terms, educational engagements aim not only at making the young generative, responsible, and upright citizens but also mature as authentic Christian/religious persons. Salesian educational service in the context of multireligious and pluricultural Indian society denotes these goals, without ignoring its scientific academic features. What we seek to explore here is how and to what extent Hindu and Muslim teachers, professors, and collaborators perceive and engage in Salesian pedagogy. Do Hindu and Islamic theological–cultural traits contribute to their educational service and experience in Salesian institutions?

Educational engagements are structured on the basis of educational theories and pedagogical sciences. With reference to the configuration of the curriculum in the public sphere of education (

Anthony 1999, pp. 41–51), we can speak of an explicit curriculum involving not only secular sciences focused on scientific knowledge but also religious education for Christians and moral/value education for adherents of neighbour religions. Just as the religious and moral/value education is a fundamental resource for upholding the goals of human dignity, human wellbeing, and the common good, every other scientific discipline taught in the educational process encompasses values that further or disvalues that hinder the attainment of integral human development, as shown, for example, in the analysis of school text books by the

Value Education Group—Society of the Sisters of St. Anne (

1991).

Implicit promotion of religious or ethical values can be attained through co-curricular/extracurricular activities in artistic sectors of music, dance, drama, etc. Then there is the hidden curriculum, that has a life-long impact on the students. It is neither explicit nor implicit, it just happens in the ambience of the relationship (loving kindness, friendliness, sympathy, hospitality, etc.) between staff and students and through the presence of signs and symbols that enliven the educational environment. The null curriculum—the one that is absent—can emerge when visiting educational centres affiliated with neighbour religions or from the collaborators and co-workers of neighbour religions. The goals of the common good sought through these varied sectors of educational curricula can be to a great extent concretized in the intersecting facets of human rights and responsibilities. Public theology of education would then have to attend to how the integral wellbeing of the young and of society—the goal of Salesian pedagogy—can be endorsed through various curricular sectors of educational engagement.

As mentioned earlier, the prism of public theology entails three agencies: church, society, and academy. The use of empirical methodology can engage these agencies: the Christian/Salesian community with their educational (college, school, and study) centres, the students and staff of Christian and neighbour religions in society, and the academic community involved in research. In other words, empirical research undertaken by the academic agency can address the lived experience of Church members and also of the members affiliated with neighbour religions in society; thus, engaging the three agencies conjointly.

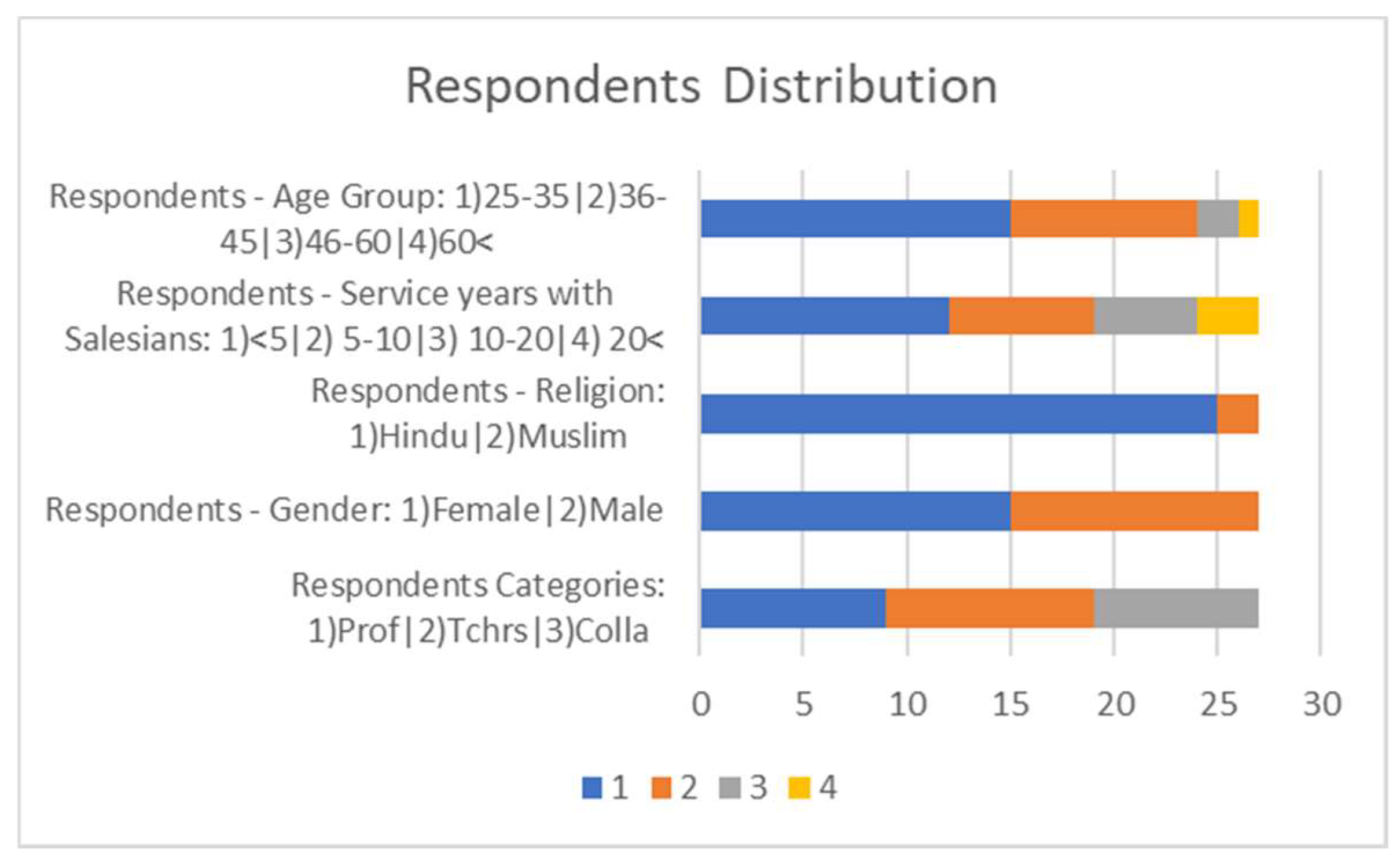

The present qualitative research (undertaken between 15 October and 31 December 2023) seeks to explore the educational engagement of Hindu and Muslim staff as their lived experience of Salesian pedagogy. With the view to study this phenomenon it was limited to Hindu and Muslim college professors, school teachers, and collaborators of evening study centres in the Salesian Province of Chennai. The sample (representing more the phenomenon than the population) comprised a total of 27 respondents distributed in 17 institutions, as shown in

Table 1 and represented in

Figure 3 (see also

Supplementary Materials S1).

As regards the type of profession, age group, and gender, the sample was found to be rather proportional. According to the last available census of 2011, 87.6% of Tamil Nadu’s population are Hindus, 6.12% are Christians, 5.86% are Muslims, 0.12% are Jains, 0.02% are Buddhists, and 0.02% are Sikhs. This explains why all our respondents are Hindus, with the exception of two Muslims.

On the basis of its core features, the Salesian pedagogy in the public educational sphere seeks to ensure human wellbeing by educating poor and marginalized youth, forming them to be good Christian/religious persons and upright citizens, respecting human dignity and environmental upkeep. These goals and features of Salesian pedagogy (reason, religion, and loving kindness) are to enliven the curriculum domains (explicit/written, implicit/unwritten, hidden/spirit, and null/ignored curricula) in the multireligious environment. Our structured interview schedule, soliciting written responses, included these intersecting features of Salesian pedagogy (see

Supplementary Materials S2).

The following section provides a concise view of the empirical analysis carried out, with its processes and a few cross-sectional data analyses from which interpretations and conclusions are drawn.

6. Empirical Analysis: Emerging Results

The qualitative data obtained from the 27 respondents were subjected to qualitative data analysis (QDA) using the QDA tool Atlas.ti which permits the classic methodology of codification. Three progressive levels of analysis were carried out, by way of codification, namely open coding, focused coding, and axial coding.

6.1. Open Coding

The process of open coding of the data resulted in 230 codes from the 27 texts analyzed. Codebook A (

Supplementary Materials S3a) presents the resultant codes in alphabetical order and Codebook B (

Supplementary Materials S3b) presents the same codes in order of frequency.

The open coding already offers a considerable indication as to how much the Hindu and Muslim colleagues appreciate the dedication of the Salesian educative system to holistic education, as the code (Code no.168) with highest frequency (19 times) emerges from at least 13 interview files, that is, 13 different persons, which is statistically 48% of the respondents (cf.

Table 2). There is one typical statement that can be cited here (from

P-IM.07): “The holistic approach, integrating values and academics, aligns with the broader goal of preparing the individuals not only for professional success but also for a life of purpose, service, and ethical leadership”.

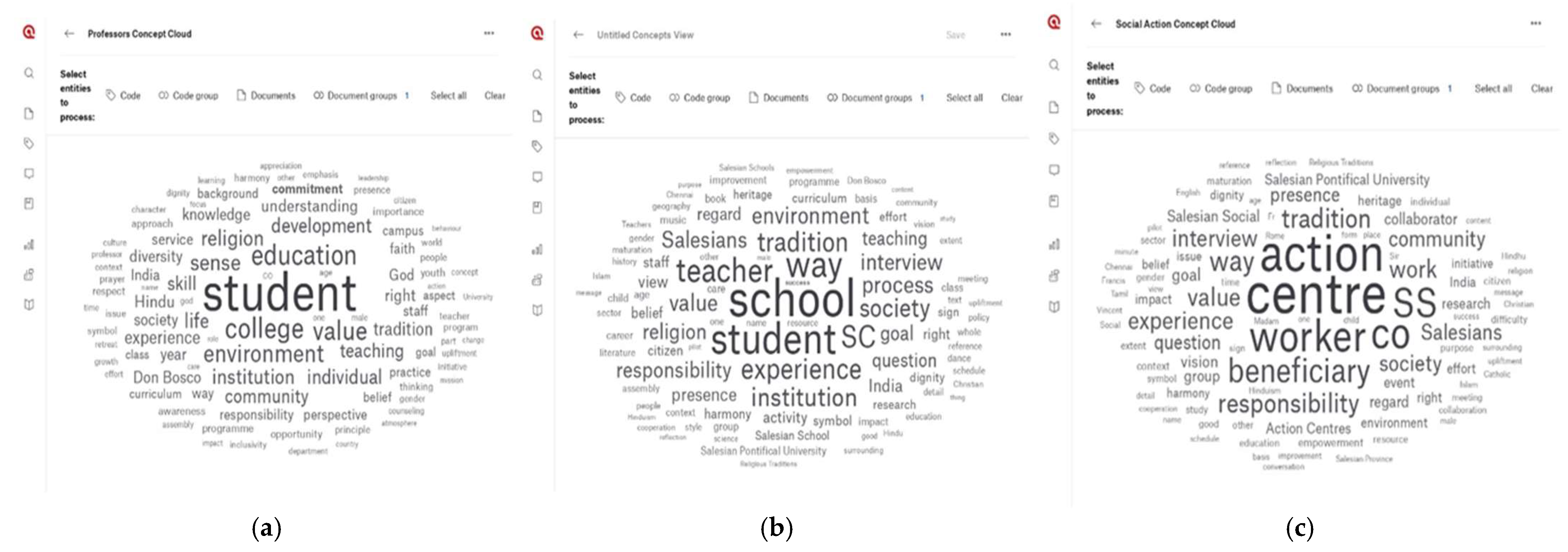

At this level of open coding, we could enquire about the dominant ideas expressed by the respondents category wise, with a concept cloud query (

Figure 4a–c):

These, apart from revealing some of the key concepts of interest of the respondents, can already be indicators of the common objectives and goals shared between the respective groups of respondents and management and among the respondent groups themselves. This, however, could make more sense, post-focus-coding, as seen in Tables 5 and 6.

6.2. Focus Coding

The transition from the phase of open coding to the phase of focus coding was facilitated by the identification of the 20 sensitizing categories (SC) from the categories sensitized already by the 10 questions that were posed, shown as the interview schedule.

Table 3 lists the 20 sensitizing categories with which the focus coding was launched and, at the end of the phase of focus coding, 25 emergent categories (EC) were identified, grouped under eight clusters of emerging themes, as listed in

Table 4. As observed just a while ago,

Table 5 and

Table 6 present the respondent distribution of sensitizing categories and emergent categories, respectively, among which a specific comparison could be made of the levels of understanding arrived at between the various categories of colleagues and the Salesians who wish to share their religious pedagogy.

From an analysis of these two tables of respondent distribution (

Table 5 and

Table 6), there could be an observation highlighted concerning the most frequent categories in each of the respondent groups. The results thus tabulated could be indicative of the fact that the Salesian religious pedagogy is shared by the colleagues on a large scale.

Table 7 reports an interesting fact that the top three referenced sensitizing categories for all the three respondent groups are the same, with the difference lying only in the order of their frequency. The category “Awareness of Educational Goals of Salesians” (SC1-1) is most commonly referenced among the professors (55) and the school teachers (29), while it is the second most common among the collaborators (29). It is an indication that reflects the importance that the colleagues attach to being aware of the educational goals proposed by the Salesian management. Another category on display is “Affirmation of Extra/Implicit Curriculum in Value Promotion” (SC5-1), which is the second most common among the professors (38) and the school teachers (20), while third most common among the collaborators in social action (17). Again, the indication here is the awareness of the colleagues of the presence of and the importance of an implicit curriculum that the educational institution has for the promotion of value education. While it is no surprise that the category “Affirmation of Salesian Social Empowerment” (SC8-1) is the most commonly referenced among the collaborators in social action (30), the table reveals that it is also the third most common for the professors (29) and the school teachers (17). This evinces the place of social empowerment within the educational processes according to the respondents and their recognition of the presence of the same in the Salesian educational process. One of the collaborators (

C-HF-20) observes, “Salesians actively promote justice by participating in initiatives that tackle challenges contributing to poverty and inequality” and she adds, “I am fully committed to the empowerment efforts of the Salesian social work centre, actively engaging in initiatives focused on uplifting the poor and marginalized sectors”. This is clearly a case of a collaborator who acknowledges not only the efforts of the institution but also one’s own contribution to the said mission. A category equally referenced, among the school teachers (17) is that of the “Affirmation of the Impact of Christian Environment” (SC0-1), which, although not among the top three, is frequently referenced in the other two respondent groups (professors—25; collaborators—15). This is an acknowledgement of the presence of Christians signs and symbols and the environment being Christian in general. The respondents not only acknowledge this fact but affirm that it has a positive impact on the overall educational process.

On the part of the emergent categories in the same table (

Table 7), we find one category in all three respondent groups as the most commonly referenced (collaborators—44; professors—48; teachers—32): “Social Dimension/Responsibility for Others” (EC-A4), which forms part of the cluster of the emerging themes, which refers to the “Implicit Recognition of the Dimensions of Religious Pedagogy, in Schools/Colleges/Institutions” (EC-A). This is an affirmation of the way the educational process is structured to promote social consciousness through assuming responsibility for the other, both interpersonally and socially. Among the professors, however, there is another category too, that shares first place as the most commonly referenced (48)—“Professional Sense of Fulfilment” (EC-F2). This EC is the second most commonly referenced among the school teachers (31) and the collaborators (37). It establishes a crucial fact that the colleagues of Salesians in the educational mission find a sense of professional fulfilment. The cluster of this emergent theme—“A Sense of Fulfilment in Collaboration” (EC-F)—has a high number of references (collaborators—63; professors—76; teachers—54) spread over all the interview files (or respondents, n = 27) without exception. The other EC within this cluster, it is relevant to note, is “Personal Sense of Fulfilment in Collaboration” (EC-F1) which has a considerable number of references too (collaborators—26; professors—28; teachers—23). Again, this is a verification of the hypothesis of this research, which aims to establish the importance of the sense of fulfilment in the context of collaboration. One of the professors has this to say: “the sense of fulfilment I derive from my work at Don Bosco goes beyond career satisfaction; it’s a realization of a deep-seated aspiration to be an agent of positive change in the lives of the underprivileged” (

P-HF-06). Another important emergent category to note could be, “General Acknowledgement of Salesian Educative System” (EC-A0) which is the third most common among the professors (41), and, although not within the top three, it is considerably referenced in the other two groups as well (collaborators—19; teachers—25). It is a reference to the fact that the colleagues in general understand the Salesian educative system or Salesian pedagogy and acknowledge its efficacy, participating in it with knowledge, acknowledgement, and appreciation. This creates a possibility that the colleagues are not merely executors of the plan or project but in their own way proponents and protagonists too.

7. Queries and the Phase of Axial Coding

The phase of focus coding takes advantage of the previous phase of analysis that has broken down the entire dataset into interpretable codes and clusters them into categories by substantiating the sensitizing categories already existing and by giving rise to the emergent categories from the clusters of the codes. These categories are already conceptualized interpretations of the data gathered. In the phase of axial coding, the categories are further correlated to theorize the data into interpretations and findings. The interpretations could be obtained by formulating specific queries from the categories and the way they correlate among themselves. Here, following the sensibilities of the theoretical phase, a few highlights of the research data could be queried in these specific lines: the way Hindu and Muslim colleagues share in the educative goals of the Salesians; how the Christian environment does not necessarily create a conflict with the non-Christian colleagues in their involvement in the mission; and the possibility of the specific contribution of neighbour religions within the educational project in the Christian institution.

7.1. Non-Christian Colleagues Sharing in Educational Mission

Querying on the lines of the way Hindu and Muslim colleagues in the educative project share the educational goals of the Salesians, we find the sensitizing category “Awareness of Educational Goals of Salesians” (SC1-1) (cf.

Table 5) and the emerging cluster of themes (EC-A) on the “Implicit Recognition of the Dimensions of Salesian Religious Pedagogy, in Schools/Colleges/Institutions”, with 10 emergent categories (cf.

Table 6), reporting 692 references (

Table 8).

The non-Christian colleagues in general find the Salesian educative system and its mission holistic in its approach and promoting a shared vision of its goals. A sharing of a Muslim respondent brings out this fact succinctly: “Salesian educators strive to instil within their students a work ethic based on mutual trust, confidence, respect and cooperation and serve students as advisers, creating a welcoming environment where every young man can maximize his potential to become something greater than himself and feel at home” (S-IM-15).

7.2. The Impact of the Christian Environment in the Eyes of the Non-Christian Colleagues

A similar line of query could be, within the purview of the multireligious context, whether there would be a possibility of conflict between the religious affiliation of the colleagues and the Christian environment that dominates the Christian/Salesian institutional ambience. While the sensitizing categories “Affirmation of the Impact of Christian Environment” (SC0-1), “Impact of the Christian Environment on the Collaborator” (SC2-2), and “Affirmation of Christian Environment as Hidden Curriculum” (SC3-1) have together a considerable number of references (151), the contrary is reflected in the scanty references (9) that are noted from the two categories “Critique of the Impact of Christian Environment” (SC0-2) and “Critique of Christian Environment as Hidden Curriculum” (SC3-2) (

Table 9).

There is an overwhelming embracing of the Christian ambience as more educative than in any way obstructive to the holistic formation of the young. A Hindu professor observes with appreciation that “the Christian Symbols and Signs that we see in our campus gives a positive vibration among us. As we place the image of our gods in our houses, we try to tell our children that god is looking at us. So are the images and symbols in the college. We feel we are loved by God”. However, the same person continues to remark that “there is chance of misunderstanding these symbols, so a proper education on these symbols should be given” (P-HF-04). The observation urges the Christian ambience to be reflexive about the role it has in the holistic formation of the young in the institutional setting.

7.3. Contribution of the Non-Christian Religions to the Educative Process

Assessing the contribution of the religious traditions other than Christian toward the educative process, the analysis presents these considerably referenced categories (

Table 10): SC2-1—“Impact of Non-Christian Tradition on the Educational goals” (47); EC-B—“Recognition and Validation of Plurality and Related Educative Processes” (234).

Finding the opportunity for their own religious tradition, or traditions other than Christian, to contribute their part in taking forward the educational mission, a collaborator in social action states, “Many religious traditions emphasize the importance of community and fellowship. Leveraging this aspect can enhance the sense of belonging and support within the social-action centre, creating a tight-knit community that reinforces positive values” (C-HM-18).

8. Public Religious Pedagogy Verified Through Emergent Categories

While an array of interpretations of the data are possible from numerous viewpoints, from the aforementioned and a gamut of tables that can be produced from the data analyzed with the help of the tool, we could conclude this part, identifying from the emergent categories the references that verify the three fundamental approaches of public religious pedagogy, as enunciated in the theoretical framework (cf. p. 7): that the educational process needs to offer an education that prepares one to promote the common good; an education that has a strong human rights perspective; and an education that is marked by an openness to religious education and moral/value education. We restrict ourselves to the emergent categories in this query, for the simple reason that the sensitizing categories were already formulated from these underlying theoretical principles and might have had a direct influence on the respondents, by the very formulation or the orientation of the interview schedule. The emergent categories, which are spontaneous themes emerging from the responses, can lead to an objective verification of the principles discussed or a nullification of them. What could be seen in the case of this research is that the emergent categories affirm and verify the three mentioned fundamental approaches, affirming in turn the hypothesis that the colleagues in the educational mission of the Salesians do share and wish to promote the educational goals, making it a quality experience of public religious pedagogy.

Indicating the presence of the trait of preparing the educand towards promoting the common good and human welfare (cf.

Table 11), we find the query bringing out from the respondents a vast number of references (350), from all the interview files (that is, from all 27 respondents). It is an indication of the fact that the Salesian educative project is seen by all the colleagues, without any exception, as a preparation of the young towards contributing to the common good. A collaborator in social action looks at his collaboration positively, as he declares: “as a co-worker in a Salesian social centre, the efforts align with the Salesian mission to empower individuals, address systemic issues, and create a more equitable and harmonious society” (

C-HM-19). A professor in the college shares: “my journey took a significant turn when I became a part of Don Bosco. Here, within the institution’s ethos, my dream of actively participating in social upliftment becomes a daily reality” (

P-HF-06). Another professor affirms his contribution in this process of educating for promoting the common good, as he states, “Whether through incorporating sustainability themes in curriculum discussions or organizing eco-friendly initiatives within the campus, I strive to instil a sense of environmental consciousness in both staff and students” (

P-IM-07).

The other fundamental approach of implementing an educational process that has a strong human rights perspective is verified too by the respondents, as the query resulted in 145 references (cf.

Table 12) from 25 respondents (of the total 27). In particular, here we find the category “Right and Freedom of Religious Plurality” (EC-B4), referenced highly in all the three respondent groups (collaborators—22; professors—20; teachers—16), which has a particular significance. It establishes the fact that the educative process does not depend only on some human rights education syllabuses or content but focuses on forming a mentality of respecting the rights of all, in the context of religious plurality. We notice largely that the non-Christian colleagues look at the ambience created as an effective means to promote this human rights mentality, more than merely an academic exercise. However, a lecturer also affirms the importance of formal education to human rights, saying, “When young pupils are exposed to human rights education, it teaches them to respect diversity from an early age. This is because no matter the differences between people—race, gender, wealth, ethnicity, language, religion, etc., we all still deserve certain rights. Human Rights protect diversity” (

P-HM-27).

Referring to it as one of the typical experiences offered in a Salesian educational setting, the respondents (at least 24 of the total 27) underscore emphatically the significance of religious education or an alternative moral or value education within the educational context. As seen from

Table 13, this theme could be gathered broadly from the nine categories which amount to 446 references, proportionately distributed among the three respondent groups. However, numerically, the professors in the colleges emphasize it more (172 references). We find references from the respondents that refer not only to the formation of the students but also to sustenance that they personally receive for their religious or spiritual wellbeing. A Hindu teacher in a school acknowledges, “working in a Christian educational institution has a positive impact of drawing me closer to God, developing my faith and creating a religious maturity in me” (

S-HF-16). The Christian ambience, apart from not being an obstacle in the practice of one’s proper faith, is seen as a means to deepen one’s own faith although non-Christian. Highlighting the place of value education offered in the institution, a Hindu teacher (

S-HF-08) feels empowered to be contributing to the building up of a better Indian society. She says, “through teaching and telling moral stories” she develops within the students “tolerance, brotherhood and humanity” which according to her will lead to forming “a good citizen and good society”. Going a step further a professor in the college reflects on the importance of example and personal witness in value formation: “Just imparting subject knowledge is not sufficient to play the role of a teacher. Through my behaviour, speech and actions I motivate the students to stay positive, smiling and be tolerant with others” (

P-HF-03).

9. Conclusions

This empirical research on the lived experience of the Salesian pedagogy among Hindu and Muslim professors in Salesian colleges, teachers in Salesian schools, and collaborators in Salesian social action centres corroborates the thesis that Salesian pedagogy can be considered as public religious pedagogy. It also points to the relevance of considering public religious pedagogy in its close link with public religious education, as interrelated features of practical public theology of education. In this way, the overall framework of Christian public theology evinces the significance of Salesian pedagogy in the public square of education in a multireligious context. Likewise, within the pedagogical experience, the Hindu and Muslim colleagues point to how they bring their respective theological vision and related values into the public sphere of the educational context.

Obviously, the empirical study carried out in Tamil Nadu can be extended successively to all other Salesian educational institutions in India and also in the world at large. The extent to which Salesian pedagogy functions as public religious pedagogy can be explored contextually and globally in the network of Salesian Institutions of Higher Education (

IUS Network 1997). The IUS network today consists of more than 95 Institutions of Higher Education spread across five continents: India (36), Brazil (11), Argentina (9), and the rest distributed in 17 other countries; engaging over 150,000 students and over 8200 professors. Sharing of lived experiences and best practices of the IUS network in this regard can lead to the further development of Salesian pedagogy as worldwide public religious pedagogy. Such an effort would be of help to the Salesians and their colleagues of Christian and neighbour religions to grasp the public theological underpinnings of Salesian pedagogy as they prepare to celebrate in 2027 the 150th anniversary of Don Bosco’s first proposal of his lived experience as a model of religious pedagogy, the preventive system.