Abstract

This article examines four block-printed Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī amulets from late Tang to early Song China, highlighting how Sanskrit-script texts circulated in everyday religious life. Through a philological and visual analysis, it reveals a decentralised dhāraṇī culture shaped by variant bījākṣara (seed syllable) arrangements, divergent textual recensions, and diverse ritual uses—from burial and temple consecration to daily wear and cave enshrinement. Rather than static texts, these amulets reflect dynamic interactions among sacred sound, material form, and vernacular Buddhist practice, offering rare insight into non-canonical transmission and popular engagement with Indic scripture.

1. Introduction

Dhāraṇī maṇḍala amulets, those circular or square ritual objects inscribed with Indic scripts, have long been marginalised in Buddhist textual studies.1 Regarded more as protective charms than as textual witnesses, they have largely escaped serious scholarly attention—particularly in terms of their Sanskrit content. Rather than offering a single definitive argument, this article contributes to a broader re-evaluation of Buddhist material textuality by drawing attention to these often-overlooked objects and the vibrant multilingual culture that they reflect.

While the amulets discussed here may not have been typically intended for reading or chanting and were often produced by craftsmen without formal knowledge of Indic languages, they nonetheless preserve some of the oldest extant versions of Buddhist dhāraṇī texts in South and East Asia. Their seed syllables, mantra structures, and script choices offer a unique lens into popular and vernacular engagements with Sanskrit, suggesting that these objects were embedded in everyday religious life far more deeply than previously assumed.

This article examines four Indic-script Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī amulets from late Tang (9th–10th centuries) to early Song (10th–11th centuries) China. While prior studies have focused on their iconography and devotional significance, their Indic-script content, ranging across Siddhaṃ, Nāgarī, and hybrid forms, has not yet received a sustained philological analysis. This project treats these amulets not only as material culture but also as living fragments of a multilingual textual tradition and as evidence of ordinary people’s engagement with sacred sound and foreign scripts. It introduces transliterations, comparative analyses, and readings of dhāraṇī variants, contributing to the growing field of editorial and historical studies of Buddhist incantation literature.

A central objective of this study is to investigate whether original Sanskrit texts (those that are now lost in their manuscript form) might survive in these dhāraṇī amulets. While current scholarship often relies on Nepalese manuscript evidence to reconstruct the Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī, these Chinese artefacts may represent an alternate and possibly earlier lineage of transmission. By identifying parallels between the Sanskrit content in these artefacts and known manuscript traditions, this section seeks to clarify how accurately Sanskrit was copied, how faithfully it was preserved, and whether these texts reflect local adaptations or a direct link to transregional Buddhist networks.

Therefore, a key argument of this project is that block-printed dhāraṇī maṇḍala amulets, especially those produced in China with little to no Indic literacy, nonetheless preserve early versions of Buddhist texts now lost in manuscript form. Though these amulets were not created for reading or chanting and were often carved by printers unfamiliar with Sanskrit, their fine workmanship and faithful reproduction of older materials make them unexpectedly valuable textual witnesses. Through a detailed analysis of mantra structures, seed syllable arrangements, script use, and the visual layout, this study repositions these artefacts at the centre of Buddhist textual transmission. Some reveal script styles, textual recensions, or mantric elements found nowhere else, pointing to lost lines of transmission distinct from canonical manuscripts in Nepal or Tibet.

In doing so, this study also contributes to our understanding of medieval Sino-Indian cultural exchange. The appearance of up-to-date Nāgarī script, previously thought to be absent from Chinese Buddhist materials, reveals that Chinese Buddhists had access to—or at least knowledge of—contemporary South Asian textual styles. This points to ongoing scribal exchanges and devotional interactions between India and China during the late first millennium CE.

By foregrounding the editorial potential of these amulets, this project reimagines their role within Buddhist textual history. They are not simply ritual accessories, but dynamic records of textual adaptation, visual creativity, and cross-cultural religious transmission.

The following sections are structured as follows: Section 2 provides the necessary historical and religious background, including the development of dhāraṇī literature in Indic Mahāyāna and its transmission to China, as well as the evolution of printing and amulet production in the medieval period. Section 3 presents four case studies—amulets commissioned by Xu Yin, Li Zhishun, the Hangzhou National Archives, and Ruiguangsi—offering an in-depth textual and material analysis. This section forms the core of the research, showcasing how close the philological study of these artefacts can illuminate broader networks of Buddhist textual transmission.

2. Background

2.1. Dhāraṇī in Indic Mahāyāna

This overview clarifies the mantric logic and flexible structure of dhāraṇī texts, providing a lens for interpreting their transformation and adaptation in later Chinese material forms. Dhāraṇīs are texts that emerged within Indic Mahāyāna from the first century CE and were transmitted during the earliest stages of the spread of Buddhism to China. Dhāraṇīs are variously interpreted as symbolic or codes to significant teachings or qualities of the Buddha or, in contrast, as nonsensical phrases to encapsulate the ineffability of reality.

Dhāraṇī is the name for a phrase or an element of text found in Mahāyāna Buddhist literature, believed to bestow some form of support on the path, access to broader teachings represented in the phrase, or of protection or power. The dhāraṇī may be relatively short, consisting of a number of syllables, or quite long, often equal to a section within a sūtra. It may stand on its own or be found within a larger text or, if extensive, form a complete text in its own right, the equivalent of several pages long (around a few hundred short sentences or phrases).

The body of a longer dhāraṇī text is often divided into padas (smaller sections) of short phrases, invocations, and mantras (spells) (). In brief, dhāraṇīs usually consist of a list of feminine vocatives embedded with some series of literally incomprehensible yet potent syllables.

The use of incantation of mantra and dhāraṇī existed more broadly in Indic religion and became familiar within the Buddhist monastic community since at least the first century of the common era (). This incantational function of dhāraṇī is a feature that continues from its Indic origin into East Asia. While similar in function to mantras, the latter are shorter and usually preserved in the formula that begins with oṃ and sometimes ends with svāhā, neither of which has a clear discursive meaning (). Some dhāraṇīs have known names. The one that concerns us most here, the Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī, is found on amulets discovered in China, which also usually contain mantras written immediately after the dhāraṇī proper.

As noted above, dhāraṇī can also be the focus or even content of entire texts—dhāraṇī sūtras (incantation scriptures). These sūtras are sometimes named with a long title that encompasses one or more terms denoting power, such as dhāraṇī, mantra, and vidyā; other terms like kalpa, pratyaṅgirā, and sūtra are also applied.2

Given their mantric components and functions, dhāraṇī sūtras, such as the Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī sūtra, are attributed to a new Buddhist soteriological path within the Mahāyāna tradition during the first half of the first millennium—the Mantranaya (Method of Mantras). This is an early stage of what we now call tantric Buddhism in general, which received its name for its unique employment of mantras and other potent linguistic phrases for soteriological and practical purposes (). Although modern scholars usually refer to this school as Vajrayāna, it is a name received far later than its actual establishment. This study uses the name Mantranaya for chronological clarity, for it occurs earlier than the seventh-century appearance of the Vajrayāna (the Path of Diamond or the Diamond Way).3

2.2. Mahāpratisarā and Transmission (Textual History and Iconography)

The extant versions of the Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī sūtra usually include two dhāraṇīs, four mantras, an introduction to the background, and cause of the nidāna (the frame story), a frame story of the Buddha teaching the dhāraṇīs, two kalpas (ritual manuals) for each dhāraṇī, instructions for amulet-making and healing, general sections enumerating the anuśaṃsāḥ (various benefits), and nine narratives about how the dhāraṇīs were used in the past. Among these nine narratives, six seem to be the original works of this scripture, while the second, third, and seventh can be found in earlier Buddhist literature ().

The Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī sūtra was composed probably no later than the sixth century, instructing the creation of a protective and wish-fulfilling amulet through the writing down of the Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī with provided rituals (ibid., p. 20). This sūtra was incorporated into a collection of five dhāraṇī sūtras called the Pañcarakṣā (Five Protections) some centuries after its composition.

The first dhāraṇī and mantras from the Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī Sūtra are often inscribed on physical objects to empower the object and create ‘amulets.’ For the sake of convenience, I shall refer to this dhāraṇī as the Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī in this investigation. These amulets may be in the form of paper or silk, fixed onto bracelets, armlets or necklaces. There are also carved brick amulets inserted into buildings, for example, in temple foundations or tomb walls.

Baosiwei (Chinese: 寶思惟, d. 721),4 a Kashmiri monk, was the first person to translate the Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī sūtra into Chinese in 693 CE, marking an early phase in the text’s transmission.5 Almost forty years later, Vajrabodhi from South India deemed this edition incomplete.6 Although the version of Baosiwei’s translation preserved in the Taishō canon may reflect Vajrabodhi’s corrections, the nature and extent of such revisions remain uncertain.7 This ambiguity is significant, as it highlights the fluidity of early textual transmission and suggests that the dhāraṇī found in Chinese amulets may reflect earlier, less systematised variants predating Vajrabodhi’s ritual reforms.

A generation later, Amoghavajra (Chinese: 不空, fl. 705–774), a key figure in Tang esoteric Buddhism, produced a more elaborate translation.8 His version integrates more developed Mantranaya ritual frameworks, including supernatural elements such as the mountain of Vajrameru in place of Baosiwei’s more conventional Gṛdhrakūṭa setting. Amoghavajra’s translation thus marks a turning point in the sūtra’s reception, linking it more explicitly to the growing tantric ritual landscape of eighth-century China.

Several Chinese translations of the Mahāpratisarā Dhāraṇī Sūtra have been preserved in the Taishō Tripiṭaka, primarily across volumes 18 to 21, offering different versions shaped by distinct translators and ritual lineages (; , T1061, 1153, 1154, and 1155). The sūtra is commonly referred to in Chinese as “大隨求陀羅尼經” (Dà suíqiú tuóluóní jīng), which may be translated as “The Great Amulet Dhāraṇī” or “The Great Wish-Fulfilling Dhāraṇī”. For further discussion on the nuances of the name’s translation and transmission, see () and ().

In most manuscripts dated after the sixth century, the Mahāpratisarā Dhāraṇī Sūtra opens with a frame story, followed by the Buddha’s exposition on the dhāraṇī’s benefits and a detailed ritual manual (kalpa) introducing the first dhāraṇī.9 A sequence of nine efficacy narratives illustrates its power in various contexts, with four mantras inserted midway. The sūtra then includes instructions for creating protective amulets. A parallel structure follows in the second part of the text, centred on a second dhāraṇī and healing ritual. This dual structure underscores the sūtra’s emphasis on both protective and curative applications (; ).

In addition to this general structuring of the content, one should notice a significant change and expansion to the scripture at the end of the seventh and start of the eighth centuries. Hidas points out that the scripture probably had only one kalpa, and therefore one dhāraṇī, when first compiled. One piece of evidence is Baosiwei’s 693 CE Chinese translation, which includes only the first dhāraṇī and kalpa. While the Taishō canon may have already been corrected by Vajrabodhi, Baosiwei’s translation nonetheless suggests that there had been refinements of the sūtra in the late seventh century to integrate it with Mantranaya, for its geographical location in the nidāna is still the historical Gṛdhrakūṭa instead of the later Mantranaya setting’s supernatural mountain, the Great Vajrameru, which appears to be in Amoghavajra’s translation ().

The Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī sūtra was also translated into Tibetan, Uigurian,10 and Mongolian from the eighth century onwards (). Most recently, Hidas published an annotated English translation of the entire sūtra in the same book where he puts the critical Sanskrit edition. This article primarily consults Hidas’ English translation.11

2.3. Dhāraṇī in China and the Development of Printing

Regardless of their origins, dhāraṇīs were ascribed protective powers and became integral to various aspects of Chinese Buddhist practice. In China, they were used for longevity, virtue, power, wealth, warding off danger, ensuring a favourable afterlife, and aiding spiritual progress. To harness these benefits, dhāraṇīs were presented in visual form as amulets, which were inscribed on various materials, such as paper, silk, and bricks. By the late Tang, the widespread use of printing enabled the mass production of dhāraṇīs in printed form, leading to the dhāraṇī amulets examined in this exploration.

Beyond their amuletic function, dhāraṇīs, in their written form, were also regarded as relics of the Buddha or his teachings. Copies of the dhāraṇī have been discovered in small stūpas (pagodas), a practice still observed in Buddhist communities today. This belief can be traced to South Asia, as Xuanzang (Chinese: 玄奘, fl. 602–664 CE) reported that people placed scripture fragments, referred to as ‘dharma relics,’ into stūpas in India (). In China, this belief extended to the practice of writing dhāraṇīs on banners.12 These varied understandings suggest that the significance of dhāraṇīs was not fixed but continuously reshaped in response to local ritual needs.

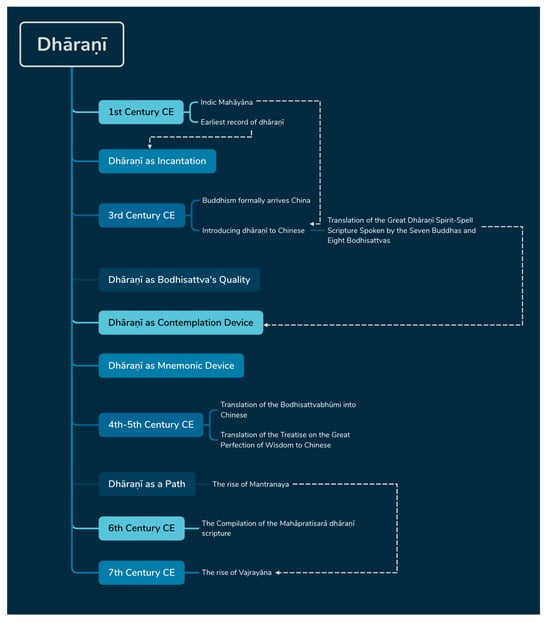

The following historical overview is crucial for understanding how the Sanskrit Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī sūtra was formally transmitted into China and subsequently adapted across various spheres of popular religious practice. A brief timeline of the development and changing roles of dhāraṇī is provided in Figure 1 (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ). One pivotal development in this process was the connection between dhāraṇī dissemination and the advent of printing. In the second year of Changshou (693 CE),13 a turning point occurred: in the ninth lunar month, Emperor Wu officially adopted the Buddhist title of Cakravartin (Chinese: 金輪聖神皇帝, “Divine Emperor of the Golden Wheel”) (). That same year, the Kashmiri monk Baosiwei arrived in Zhou and became the first person to translate the Sanskrit Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī sūtra into Chinese in Luoyang,14 the political centre of Zhou15.

While the amulets explored here date from the late Tang, some two hundred years later, they emerged as a direct result of these earlier developments. On the one hand, xylographic amulets were identified as containing the Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī first translated by Baosiwei. On the other hand, they were shaped by the emergence of printing under Emperor Wu and the belief in the power of sacred phrases. These beliefs included the idea that such phrases encapsulated the qualities of the Buddhas, were relics of the Buddha, ensured meritorious reproduction, and granted longevity and protection.

Some of the earliest printed works in existence are dhāraṇīs, such as the Hyakumantō, produced during the mid-seventh century under Empress Shōtoku in Japan (). Tim Barrett has suggested that early developments in printing during the rule of Emperor Wu Zhao (Chinese: 武曌, fl. 624–705 CE) were deeply shaped by ritual ideas:16 Buddhist sūtras were seen as relics, and their reproduction was considered a powerful meritorious act (). Wu Zhao promoted the mass copying of texts, particularly dhāraṇīs, which were believed to be exceptionally potent, functioning “100,000 times more effectively” than other scriptures17 (). These political–religious precedents created a discursive and ritual environment in which textual reproduction through printing became a form of devotional participation, laying the foundation for mass-produced dhāraṇī amulets.18

Around the same time, a significant parallel development occurred in Korea. In 1966, an early printed copy of the Wugou jingguang tuoluoni jing (無垢淨光大陀羅尼經) was discovered in the Sŏkkat’ap (釋迦塔) of Pulguksa Monastery (佛國寺). Korean scholars generally date this print to the first half of the eighth century, prior to its enshrinement in the pagoda around 751 CE (). This find offers further evidence that dhāraṇī texts were instrumental to the earliest experiments in printing technologies across East Asia.

Figure 1.

Timeline of dhāraṇī.

In most studies of Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī amulets in China, these amulets are classified into three types based on their method of production: (1) hand-written, (2) partially hand-written and partially printed, and (3) fully printed (; ). Table 1 at the end of this section details the discovery sites, colophons, devotee names, and sources of information where applicable. Moreover, Table 2 outlines a basic timeline for the development and transmission of the Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī, tracing its evolution from early Indic forms to Chinese translations in the 7th–8th centuries CE. This classification provides insight into the historical development of amulet production alongside the evolution of printing technology in China.

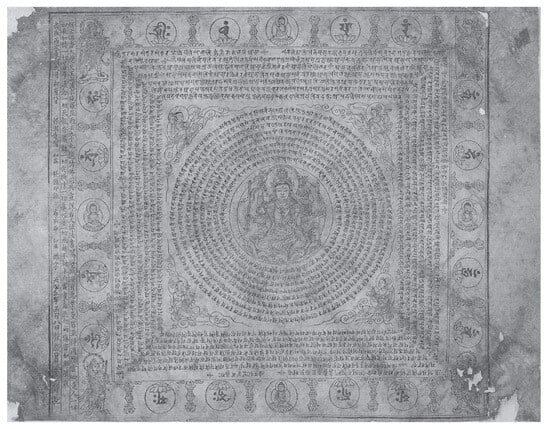

While the potency of Buddhist phrases as relics and sources of power contributed to printing’s spread, all the amulets discussed here date no earlier than the eighth century, when printing had become widely established. Over time, a trend of increasing amulet sizes emerged towards the end of the tenth century. Examples range from an amulet associated with Madame Wei (21.5 × 21.5 cm) (Figure 2) to that of a monk named Xingsi (44.5 × 44.3 cm), which will be discussed in the next section.19 Though precise dating remains uncertain for most amulets, the earliest ones are believed to date from the mid-eighth century, coinciding with the second translation of the Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī sūtra.20 According to Copp, the earliest of these amulets is the one that belongs to Madame Wei ().

Hand-written and partially hand-written amulets tend to be more personalised than printed ones. They often contain devotee names and Buddhist terms in Chinese characters alongside Indic scripts, presumably identifying the owners (ibid., p. 75). For instance, the silk hand-written dhāraṇī amulet associated with Madame Wei includes her name in the sixth circle from the centre (Figure 2) (). Similarly, the silk amulet of Jiao Tie-Tou features his name alongside phrases such as All Buddha’s Heart Spell (一切佛心咒, yīqiè fó xīn zhòu), ablution (灌湯, guàn tāng),21 and formation of enclosure (吉界, jí jiè).22 This practice of personalising sacred texts reflects an evolving understandings of sacred language, inscription, and devotional engagement.

Conversely, printed amulets were mass-produced and lacked such customisation. Their standardised scripts reflect broader trends and ‘fashion’ in Buddhist material culture. The colophons of some printed amulets reveal their commercialised distribution across China by the ninth century (). The most prominent example is an amulet discovered in a tomb in Xi’an, which took place in Chengdu, some seven hundred kilometres from Xi’an.23 Ma connects this amulet with another Chengdu-printed Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī amulet excavated at the site of Sichuan University. The similarities in the location and formatting suggest a shared origin. Since the dating of the Chengdu-discovered amulet was confirmed to be late Tang (late ninth century), Ma argues that the Xi’an amulet was likely produced in the second half of the ninth century24.

The rest of this article focuses on printed amulets, with a close analysis of four xylograph samples. These include specimens from Luoyang, Dunhuang, Hangzhou, and Suzhou, which collectively reveal evolving Indic script practices and regional ritual adaptation.

Table 1.

List of Indic script Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī amulets discovered in China (; ; ; , Tang dynasty woodblock print; )25.

Table 1.

List of Indic script Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī amulets discovered in China (; ; ; , Tang dynasty woodblock print; )25.

| Place of Discovery | Container | Name of Devotee | Name of Carver | Current Location | Estimated Date of Creation | Handwritten or Printed? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turfan (Turfan 72TAM188:5) | No case (covered on the corpse) | NA | NA | Turfan? | Early mid-eighth century? | Handwritten |

| Turfan (Turfan 72TAM189:13) | No case (covered on the corpse) | NA | NA | Turfan? | Early mid-eighth century? | Handwritten |

| Xi’an (Fenghao Rd 西凤路高洼) | Armlet of gold-enameled bronze, 1 cm in width, with copper box riveted to it, 4.5 × 2.4 cm | Jiao Tie-Tou | NA | Shaanxi Provincial Museum (陕西历史博物馆) | Late eighth century? | Handwritten |

| NA | NA | Madame Wei | NA | Yale Art Gallery | Ninth or tenth century | Handwritten |

| Xi’an (Diesel machine factory) | Arc-shaped copper pendant, 4.5 × 4.2 cm | Wu De [ _ ] | NA | Xi’an? | Ninth or tenth century? | Partially |

| Xi’an (Fenghe 冯河) | Copper tube, 4 × 1 cm | Jing Sitai | NA | NA | Mid/late eighth century? | Partially |

| NA. Previously owned by Jiuxitang | Copper container? | NA | NA | Hangzhou Branch of the National Archives of Publications and Culture (杭州国家版本馆) | Mid/late eighth century? | Printed |

| Sichuan University/Jin River, Chengdu | Silver armlet | NA | NA | National Museum of China (中国国家博物馆) | Late ninth (post 841) or very early tenth century | Printed |

| Xi’an (Sanqiao 三桥镇) | Copper armlet, 9 cm in diameter, 1 cm in width | Monk Shaozhen | NA | Shaanxi Provincial Museum (陕西历史博物馆) | Late ninth century | Printed |

| NA. Previously owned by Bodhi-nature/Shanghai auction? | Metallic container? | NA | NA | NA | Ninth or tenth century? | Printed |

| Luoyang | Small tube (dimensions and material unknown) found near ear of corpse | Xu Yin, Monk Zhiyi | Shi Hongzhan | Luoyang Cultural Relics Work Team (洛阳文物工作队) | 926 | Printed |

| Mogao Cave 17, Dunhuang | No case | Li Zhishun | Wang Wenzhao | British Museum and Musée national des Arts asiatiques—Guimet (Pelliot Collection) | 980 | Printed |

| Mogao Cave 17, Dunhuang | No case | Yang Fa | NA | Musée national des Arts asiatiques—Guimet (Pelliot Collection) | Late tenth century? | Printed |

| Ruiguangsi, Suzhou | Found in small pillar inside stūpa | Monk Xiuzhang | NA | Suzhou Museum (苏州博物馆) | 1005 | Printed |

| Xiasha Outlet Gallery Museum | NA | NA | NA | Xiasha Outlet Gallery Museum | Ninth or tenth century? | Printed |

| Xiasha Outlet Gallery Museum | NA | NA | NA | Xiasha Outlet Gallery Museum | Ninth or tenth century? | Printed |

| Xiasha Outlet Gallery Museum | NA | NA | NA | Xiasha Outlet Gallery Museum | Ninth or tenth century? | Printed |

| Xiasha Outlet Gallery Museum | NA | NA | NA | Xiasha Outlet Gallery Museum | Ninth or tenth century? | Printed |

| Xiasha Outlet Gallery Museum | NA | NA | NA | Xiasha Outlet Gallery Museum | Ninth or tenth century? | Printed |

| Xiasha Outlet Gallery Museum | NA | NA | NA | Xiasha Outlet Gallery Museum | Ninth or tenth century? | Printed |

| Xiasha Outlet Gallery Museum | NA | NA | NA | Xiasha Outlet Gallery Museum | Ninth or tenth century? | Printed |

| Xiasha Outlet Gallery Museum | NA | NA | NA | Xiasha Outlet Gallery Museum | Ninth or tenth century? | Printed |

| Time | Name | Place |

|---|---|---|

| 5th Century CE | Earlier layers or forms of the MPMVR | North India |

| 6th Century CE | Mahāpratisara Mahāvidyārāja | North India |

| Early 7th Century CE | Mahāpratisarā Mahāvidyārājñī, | North India |

| Late 7th Century CE | Refinement for integration into the Vajrayāna (the Diamond Way) and the appearance of the protective goddess Mahāpratisarā | NA |

| 693 CE | Chinese translation of the Fóshuō suíqiú jí dé dàzìzài tuóluóní shénzhòu jīng | Luoyang |

| Early 8th Century CE | (Grouped with the) Pañcarakṣā | Samye |

| 8th Century CE | Chinese translation of the Pǔbiàn guāngmíng qīngjìng zhìshèng rúyì bǎoyìn xīn wúnéngshèng dàsuíqiú tuóluóní jīng | Xi’an |

Figure 2.

Madame Wei (魏大娘)’s handwritten and painted silk, centre image Vajradhara empowering Wei, Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī, mid-eighth century (743–758 CE), now in (), The Hobart and Edward Small Moore Memorial Collection. © Yale University Art Gallery, “Buddhist Amulet with Bodhisattva and Donor”, Hobart and Edward Small Moore Memorial Collection, Accession No. 1955.7.1.

3. Case Studies

3.1. Introduction

The dhāraṇī amulets examined in this section provide a distinctive perspective on the interaction among Chinese Buddhist artisans, donors, and the broader Sanskrit manuscript tradition. Rather than indicating that these texts were intended for a Sanskrit-literate audience, their presence within these objects suggests a connection to Sanskrit textual traditions through reproduction and adaptation. Rather than focusing on script forms or transliteration, this study examines how these amulets preserve Sanskrit textual material, sometimes in imperfect yet revealing ways, offering alternative sources for studying Sanskrit dhāraṇīs outside traditional manuscript traditions.

This investigation, therefore, moves beyond the question of who could read these texts and instead asks the following: what do these inscriptions reveal about the transmission of Buddhist dhāraṇīs? How do these textual artefacts challenge existing manuscript-based reconstructions of Sanskrit Buddhist texts? And to what extent do these amulets serve as material witnesses to Indic scriptural traditions that may no longer survive in manuscript form? Through a close reading of the amulets’ textual components, this section reexamines the role of script, copying practices, and transmission networks in shaping Buddhist material culture during this period.

3.2. The Dhāraṇī Amulets as Textual Artefacts

The dhāraṇī amulets examined in this study offer critical insights into the transmission and adaptation of Sanskrit Buddhist texts in China. These artefacts, often discovered in reliquaries, caves, and private collections, contain intricate combinations of dhāraṇīs, bījākṣaras (“seed syllables”), and donor inscriptions that provide valuable context for their production and use. Across different examples, we observe the interplay of textual fidelity, artistic execution, and ritual intention, raising important questions about how these amulets were copied, transmitted, and perceived by their users.

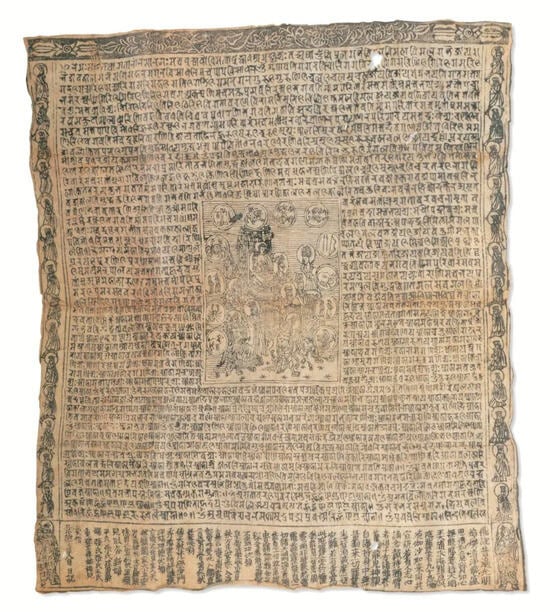

One of the earliest examples analysed in this study was unearthed in Shijiawan, Luoyang, dating to 926–927 CE (Figure 3). This amulet was commissioned by Monk Zhiyi (僧知益) of Baoguo Temple, inscribed by Shi Hongzhan (石弘展), and ultimately acquired by Xu Yin (徐殷), whose handwritten addition dates to early 927 CE. The main body consists of a large dhāraṇī square on the right, surrounded by sixteen bījākṣaras, with a Chinese inscription running down the left-hand side of the main square. The dhāraṇī itself is rendered in Siddhaṃ script, whereas the Chinese inscription provides an explanatory passage, stating that writing down and wearing this dhāraṇī would eliminate all bad karma and protect the wearer from disasters, in accordance with the scriptures. This particular amulet is significant not only for its meticulous carving but also for the additional layer of textual engagement provided by Xu Yin’s personal annotation, which allows us to trace both its initial printing (21 May, 926 CE) and subsequent acquisition (12 February, 927 CE).28 The careful arrangement of eight circular seals, seven square sections of Siddhaṃ script, and four offering bodhisattvas further reflects its role as an object of devotion and ritual efficacy.

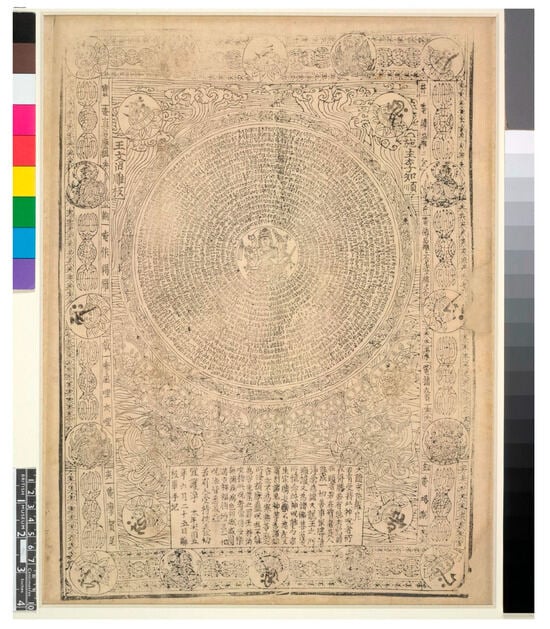

One of the earliest examples analysed in this study is an amulet discovered in Mogao Cave 17, Dunhuang, dated to 980 CE (Figure 4). This artefact, commissioned by Li Zhishun (李知順) and carved by Wang Wenzhao (王文沼), presents an intriguing combination of Siddhaṃ bījākṣaras and Nāgarī script dating to the 6th–8th centuries. Unlike earlier dhāraṇī amulets, which predominantly relied on Siddhaṃ as the standard script for rendering Sanskrit texts in Medieval China, this amulet demonstrates the presence of Nāgarī script as an alternative means of writing Indic syllables. The use of Nāgarī in a Chinese Buddhist context suggests that Siddhaṃ was not the only script employed for transcribing Sanskrit dhāraṇīs, highlighting the more diverse landscape of script usage in medieval China than previously assumed. Whether this reflects direct manuscript influence, an experimental variation, or the scribal choices of the block carver remains open to interpretation. However, this example contributes to a broader understanding of the multiplicity of Indic scripts in Chinese Buddhist textual culture.

Figure 3.

Xu Yin (徐殷)’s Block Print Paper, Siddhaṃ script, Eight-armed bodhisattva Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī. After (), “Dasuiqiu Tuoluoni Zhoujing de Liuxing yu Tuxiang [大隨求陀羅尼咒經的流行與圖像]”, [The Popularity and Imagery of the Dasuiqiu tuoluoni jing] 普門學報 [Pu men xue bao] no. 45 (May 2008): 127–167, 138.

A further example, now housed in the Hangzhou Branch of the National Archives of Publications and Culture, was originally acquired through auction by a private collector, Jin Liang (Figure 5) (). While its exact date remains uncertain, the museum has tentatively attributed it to the 8th–10th centuries (Museum Label for Paper Block-Print Dasuiqiu Tuoluoni Jingzhou, late Tang dynasty (). This amulet is largely illegible due to preservation issues and poor printing quality, making its Siddhaṃ script unrecognisable. However, another piece, believed to have been printed from the same woodblock, is now preserved in the Xiasha Outlet Gallery Museum. This second specimen is far clearer, with legible Siddhaṃ characters and a handwritten inscription at the bottom of the lotus seat (). The handwritten addition expresses a wish to be reborn in the Tuṣita Realm of Maitreya, a goal that the Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī promises to fulfil.29

The existence of two nearly identical prints from the same block suggests a larger production network for such amulets. While the Hangzhou-branch example is too faded for a detailed textual analysis, its presumed twin in the Xiasha Outlet Gallery Museum provides key insights into both the textual and ritual dimensions of these objects. Despite uncertainties about its precise provenance, this case further illustrates the continued use of bījākṣaras and dhāraṇīs in private devotional practice, reinforcing their role in esoteric Buddhist traditions. Further research is needed to clarify its place within the broader landscape of dhāraṇī circulation and transmission in medieval China.

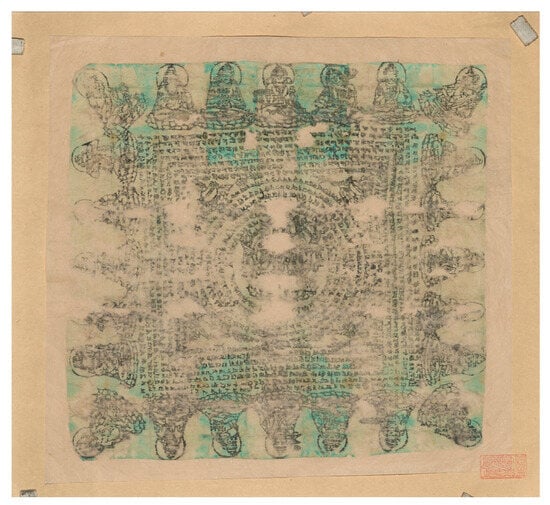

A compelling example of dhāraṇī amulets in medieval China comes from the Ruiguang Stūpa (瑞光寺塔) in Suzhou, dating to 1005 CE (Figure 6). Two copies of the Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī were found in a reliquary on the third floor of the stūpa: one written in swirling Chinese calligraphy (dated 1001) and the other in 9th-10th century Nāgarī script (dated 1005) (). This latter example, carved by Monk Xiuzhang (沙門秀璋) and donated by Geng[…]Wai (耿[…]外), presents a distinct composition. Instead of a standard bodhisattva icon or an image of devotees, its central figure is the Chishengguang Buddha (熾盛光佛), the Effulgent Buddha, surrounded by nine planetary luminaries and twelve zodiac signs.30 As Eugene Wang has shown, this celestial layout mirrors ritual cosmograms depicting the Buddhist response to planetary deities, especially those associated with calamity (). The iconography likely functioned to pacify “evil luminaries” (sida eyao 四大惡曜): Mars, Saturn, Rāhu, and Ketu, whose disruptive influence in astrology was believed to be mitigated through dhāraṇī and mantra recitation (ibid., 148). The inner precincts, encircled by lunar mansions and mantric syllables, symbolise the sanctified enclosure of one’s “life chamber” (benming gong 本命宮), within which celestial forces were ritually harmonized (ibid., 150). By the time this amulet was created, Chishengguang had come to embody the role of the celestial ruler of the northern pole, paralleling Ziwei Beiji Dadi (紫微北極大帝), and served as the Buddhist Thearch who subjugated unruly planetary spirits (ibid., 152).

Scholars such as Eugene Wang, Katherine R. Tsiang, and Paul Copp have examined this artefact in detail, noting its fusion of Daoist cosmology and Buddhist ritual imagery. The association between the astrological deities, such as Chishengguang Buddha and the Daoist deity Ziwei Beiji Dadi, suggests an ongoing process of syncretic adaptation, in which Buddhist protective dhāraṇīs absorbed liturgical elements from Daoist astrological traditions.

Beyond its iconographic significance, the use of Nāgarī script in this amulet is particularly noteworthy. While earlier Chinese Buddhist materials primarily employed Siddhaṃ script, this amulet, together with Li Zhishun’s amulet, reflects a gradual transition toward alternative Indic scripts in 10th-11th-century China. The presence of Nāgarī alongside Siddhaṃ suggests an increasing openness to new calligraphic traditions, possibly influenced by international Buddhist interactions. This shift may indicate broader developments in textual transmission, script adoption, and evolving scribal practices in Chinese Buddhist communities.

Across these case studies, dhāraṇī amulets functioned not only as ritual objects but also as markers of textual and artistic exchange. Whether meticulously copied, imprecisely carved, or infused with new iconographic elements, these amulets reflect the multifaceted processes of adaptation and transmission that shaped the material culture of esoteric Buddhism in medieval China.

Figure 4.

Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī amulet, print on paper, Dunhuang, 980 CE. Museum number: 1919,0101,0.249. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Source: British Museum Collection Online. ().

Figure 5.

Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī amulet, paper block-print, late Tang dynasty (8th–10th century). Curated by the Hangzhou Branch of the National Archives of Publications and Culture (杭州国家版本馆). Image reproduced with permission. All rights reserved.

Figure 6.

Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī amulet (摩訶般若波羅蜜多心經陀羅尼) discovered in the Ruiguangsi Stūpa (瑞光寺塔), Suzhou, dated 1005 CE. Suzhou Museum collection. © Suzhou Museum (苏州博物馆). ().

3.3. Sanskrit Texts

3.3.1. Amulet of the Hangzhou Branch of the National Archives of Publications and Culture

The Hangzhou National Archive Museum labels this print as a Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī. Although explicit documentation supporting this identification is absent from the Archives’ catalogues, the attribution remains plausible given the estimated date of the amulet and the widespread tradition of creating and using Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī amulets during the 8th to 10th century. Despite the severe damage preventing a conclusive textual identification, a comparison with the clearer Xiasha amulet—which, although not definitively confirmed to have used exactly the same woodblock, clearly contains readable Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī text in intelligible Siddhaṃ script—strengthens the attribution of the Hangzhou amulet as part of this dhāraṇī tradition ().

3.3.2. Xu Yin’s Amulet (926–927 CE)

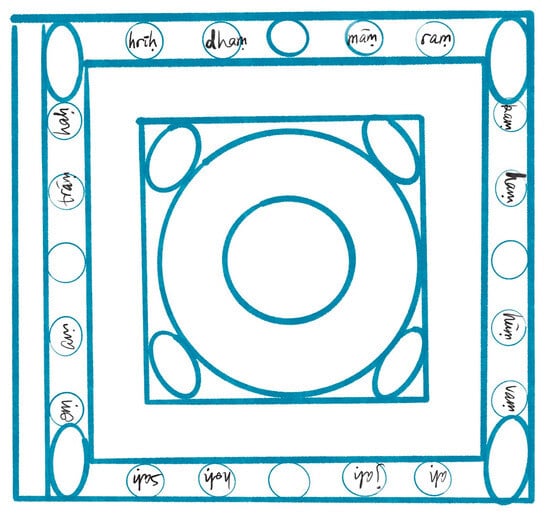

Xu Yin’s amulet features sixteen bījākṣaras arranged symmetrically around the central dhāraṇī. Each bījākṣara is seated on blooming lotuses, positioned in groups of four along each side, and separated by five vajras. These syllables are often understood as esoteric syllabic particles that constitute mantras or symbolise Buddhist deities (). The reading order follows the standard mantra structure, beginning with “oṁ” at the bottom left corner and continuing upwards along the square. The transliteration is as follows (also shown in Figure 7):

- (left) oṁ aṃ trāṃ haḥ

- (top) hrīḥ dhaṃ māṃ raṃ

- (right) kaṃ haṃ hūṁ vaṁ

- (bottom) aḥ jaḥ hoḥ saḥ

The bījākṣaras on this amulet appear to have been printed using a different woodblock from the dhāraṇī itself, or possibly added onto the woodblock after the lotuses were carved. Some of their strokes overlap onto the lotuses, suggesting a possible secondary layer of carving. This variation raises the question of whether these bījākṣaras served as ritual additions rather than being intrinsic to the amulet’s original design.

Intriguingly, the outermost layer of the amulet’s dhāraṇī maṇḍala contains four complete mantras:

- oṃ amṛtā vare vara vara pravara vipujre hūṃ hūṃ phaṭ phaṭ svāhā ||

- oṃ amṛtā vilokini garbhasaṃraḥkṣaṇi akaṣiṇi hūṃ hūṃ phaṭ phaṭ svāhā ||

- oṃ vajrāddhāna hūṃ jaḥ oṃ vimarajayavarī amṛte hūṃ hūṃ hūṃ hūṃ phaṭ phaṭ phaṭ phaṭ svāhā ||

- oṃ bhara bhara saṃbhara saṃbhara idriyavisodhani hūṃ hūṃ rūrūcari svāhā ||31

Given that some sounds from these mantras, such as aṃ from amṛtā and jaḥ from the penultimate mantra, correspond closely to certain bījākṣaras, it is plausible—though speculative—that the sixteen bījākṣaras might represent abbreviated or symbolic forms of these four mantras. However, each bījākṣara could carry multiple meanings, and thus, identifying a direct correspondence between specific bījākṣaras and individual mantras remains uncertain without additional evidence.

Figure 7.

Transliteration of the bījākṣaras on Xu Yin’s amulet.

3.3.3. Li Zhishun’s Amulet (980 CE)

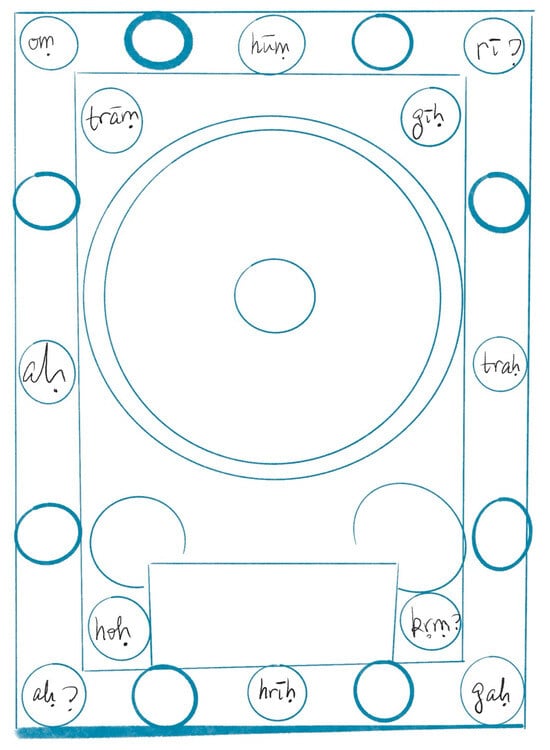

Li Zhishun’s amulet, unlike Xu Yin’s, contains twelve bījākṣaras, distributed between its inner and outer frame boundaries. The transliteration is as follows (also shown in Figure 8):

- Outer frame: oṁ hūṃ rī traḥ gaḥ hrīḥ aḥ aḥ

- Inner frame: trāṁ gīḥ kṛṁ hoḥ

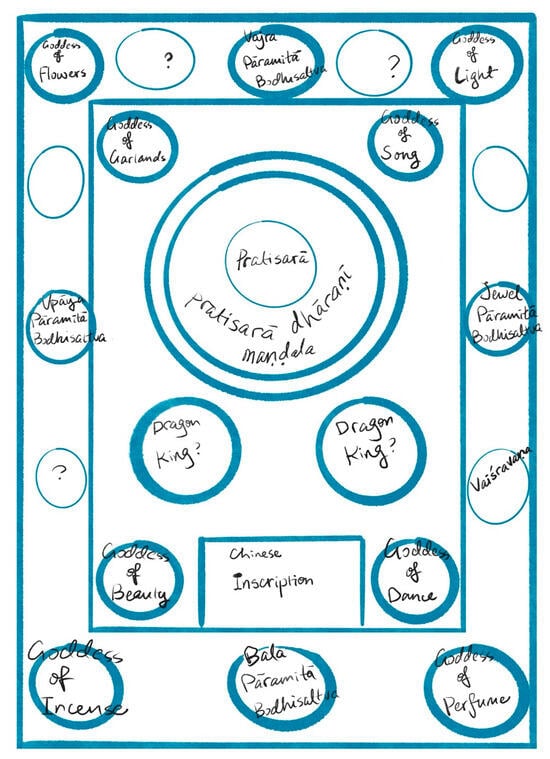

These bījākṣaras on this piece of amulet were first studied by Matsumoto Eiichi, who suggested that the ones in the inner boundary were the representatives of the four inner offering bodhisattvas,32 the four at the corners of the outer boundary stood for the outer offering bodhisattvas,33 and the four remaining ones at the middle of each side resemble and designate the four Pāramitā (perfection) bodhisattvas (). He also provided a diagram to show whom they symbolise (for a translation of this diagram, see Figure 9). Besides this suggestion, Ma notes that the bījākṣaras in the inner boundary are emblements of Sìshēn púsà (the Four-body bodhisattva) (). This structure indicates that the bījākṣaras on this amulet were not merely syllabic components of a mantra but also symbolic tokens representing deities, reinforcing their role in esoteric visualisation and ritual practice.

Figure 8.

Transliteration of the bījākṣaras on Li Zhishun’s amulet.

Another notable feature is the Chinese transliteration of Sanskrit mantras found on the sides of Li Zhishun’s amulet (980 CE). In addition to the symbolic arrangement of bījākṣaras, the Li Zhishun amulet also contains Chinese-transliterated Sanskrit mantras that invoke the eight tools held by Mahāpratisarā, the central figure in this amulet’s design. The transliteration and translation of these Chinese-transliterated Sanskrit mantras are as follows:

- Right side frame:

- 唵縛日羅二合唵縛日羅二合娑縛二合 唵播奢 唵竭誐

- oṃ vajra twice, oṃ vajra twice and sarva twice, oṃ pāśa, oṃ khaṅga

- Left side frame:

- 唵真多麽抳 唵作羯羅 唵底哩戍哩 唵摩賀尾

- oṃ kaṇṭhamaṇi, oṃ cakra, oṃ trisula, oṃ maghava34

These mantras are mostly assigned with the name of the powerful object written in Chinese characters before them (in order):

chǔ (club, Skt: vajra), fǔ (axe), suǒ (lasso, Skt: pāśa), jiàn (sword, Skt. khaṅga), bǎo (jewel, Skt. kaṇṭhamaṇi), lún (wheel, Skt. cakra), jǐ (spear, Skt. triśūla), jiá (folder).35

This direct association between the mantras and the eight ritual tools, also held in each of the central figure’s eight hands on this amulet,36 reinforces the idea that Mahāpratisarā was not only invoked through the dhāraṇī but also through her attributes, connecting textual and visual elements in a structured ritual composition. These findings suggest that the bījākṣaras and mantras functioned as ritual markers within a carefully structured tantric framework, aligning them with the esoteric Buddhist practice of visualisation and deity invocation.

Figure 9.

Translation of Matsumoto Eiichi’s diagram.

3.3.4. Comparison and Analysis of the Bījākṣaras

The sixteen bījākṣaras on Xu Yin’s amulet are placed only along the sides, while the twelve on Li Zhishun’s amulet are arranged both on sides and corners. Their patterns differ significantly, sharing only their initial and final syllables. Moreover, the four outer offering bodhisattvas are already decorated in the four corners of the dhāraṇī maṇḍala.37 Therefore, Matsumoto’s hypothesis linking the bījākṣaras on Li Zhishun’s amulet to offering and Pāramitā bodhisattvas is unlikely to apply directly to Xu Yin’s amulet. Any direct connection would require assuming a rapid change in symbolism within the fifty-three-year gap separating these two amulets.

Nevertheless, both amulets clearly reflect the concept of ritual space construction as suggested in Baosiwei’s and Amoghavajra’s translations of the Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī sūtra. Ma has identified a shift in iconography among Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī amulets, noting that earlier Tang-era examples frequently featured mudrās and Buddhist power instruments on their borders, whereas later amulets like Xu Yin’s emphasise bījākṣaras instead (). The Tang amulets often included elements such as mudrās on their frames—for example, the Xi’an suburb fragments (eight or ten mudrās) (ibid., 531–32), Wu De’s amulet (ten mudrās) (Figure 2),38 the Metallurgy Works amulet (ten mudrās) (ibid., 536–37), Jing Sitai’s amulet (four mudrās) (ibid., 538–39), and the Longchi Fang and Baoen Si fully printed amulet (eight mudrās) (ibid., 540, 542). The bījākṣaras on Xu Yin’s and Li Zhishun’s amulets could be seen as evolving from these earlier visual mudrās, potentially taking over their ritual function as ‘seals’ (印, yìn) or keys to the dhāraṇī-portal, as explicitly prescribed in the Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī sūtra translations.39 The scripture instructs that multiple seals should be drawn around the mantra for an amulet to be ritually effective.40 Each amulet embodies a ritual altar, visually representing powerful instruments—such as vajras, lotuses, and various offerings—around the central deity. This visual design directly follows the scriptural instructions, effectively making the amulet a portable ritual space for personal devotion. Thus, the most plausible theory for the configuration of bījākṣaras on Xu Yin’s amulet suggests that it may stem from an evolution—from mudrās, serving as “seals” for the “dhāraṇī-portal” to control its open and close, to the bījākṣaras, the need for “seals” on each side of the amulet, which form the mantras and dhāraṇīs that bridge the profound knowledge, a power received from a new interpretation of Amoghavajra’s translation.

3.3.5. The Ruiguangsi Amulet (1005 CE)

Unlike Xu Yin’s and Li Zhishun’s amulets, the Ruiguangsi amulet (1005 CE) does not feature bījākṣaras but introduces a Nāgarī script inscription that closely resembles 9th–10th-century Western Indian inscriptions, as classified by (). This resemblance suggests a possible textual transmission route from regions such as Vidarbha, which falls within this classification.41

A particularly intriguing aspect of the Ruiguangsi amulet is its final invocation, which differs significantly from earlier dhāraṇī amulets. The final mantra on the Ruiguangsi amulet includes the following unusual phrase:

vidani sulekha

This phrase is particularly interesting because it does not follow standard mantric structures, which typically begin with oṃ and conclude with hūṃ, phaṭ, or svāhā.42 The term sulekha is the Sanskrit word for “having or forming auspicious lines”43 or “well-written”, which suggests that the phrase may not have been part of the original dhāraṇī. Instead, it could represent a note of praise for the calligraphy or text or perhaps function as a signature-like attribution by the scribe, affirming the quality or legitimacy of the inscription.

However, the meaning of vidani remains uncertain. One hypothesis is that it represents a proper noun, possibly the carver’s name. Alternatively, it could relate to Vidarbha, aligning with the Nāgarī script’s resemblance to 9th–10th-century Western Indian inscriptions (). This hypothesis is strengthened by the fact that Nāgarī ni and bhi look very similar. If this was a scribal error and the word should instead be read as vidabhi, it would closely resemble the name “Vidarbha”, a historical, geographical region in Western India.44

These amulets illustrate how dhāraṇī practices in medieval China were not static but adapted dynamically, incorporating new deity associations, evolving script choices, and developing distinct regional mantra traditions that persisted beyond China into Japanese esoteric practices. Whether through the invocation of Mahāpratisarā’s attributes, the adaptation of deity-associated syllables, or the integration of newly emerging scriptural formulas, these amulets bear witness to a complex process of ritual and textual reinvention.

3.4. The Role of Copying Practices in Buddhist Transmission

3.4.1. Li Zhishun’s Amulet

The Li Zhishun amulet is significant in two primary ways: first, for its refined printing technology and embellished illustrations; second, for the script of the written dhāraṇī itself. While every character is clearly visible, the script employed diverges considerably from standard Siddhaṃ, rendering it difficult to decipher. The brushwork suggests an influence from Chinese calligraphy—characterised by predominantly straight strokes with abrupt turns—contrasting the typical carving patterns of Indic scripts. Despite the familiar iconography, this dhāraṇī does not match any known versions of the Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī.

For example, an attempt at transliteration of the innermost circle of the dhāraṇī reveals significant uncertainties, marked here as [?]:

baddhabadhi||[?][?]tathā[ga?]toyalaga[ja?][?]pra[rro?][?][?]hārvāhāyalidhāga[ya?]bharāyayadhā[?]badhi|li[?][?]|[?][?][?][?]rākṣa[?][ya?]dhara[?]traṇigabha[?]ṣaṇi[ga?][rdha?][?][ga?]

The phrase preceding the first double daṇḍa “||” may be buddha-bodhi, while the word immediately following the daṇḍas is tathāgata. However, most Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇīs (see Hidas’ transliterations and the one recorded in T1153_.20.0632b01) begin with a veneration phrase including the term namaḥ (to bow, honour, or salute). If this salutation is missing, the subsequent phrase still does not appear in any known versions of the Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī. Due to these uncertainties, further research is required to establish the textual basis of this dhāraṇī.

3.4.2. The Hangzhou Amulet

A key distinguishing feature of the Hangzhou amulet is the absence of a Chinese colophon, which is typically crucial for identifying printed dhāraṇīs. Despite its blurred state, the Siddhaṃ script provides two important insights regarding the structure and orientation of the dhāraṇī maṇḍala:

- Unconventional Script Orientation: The central circular maṇḍala follows an ‘inside-out’ writing pattern, whereas the surrounding square-shaped maṇḍalas are oriented ‘outside-in.’ This contrast in orientation is not observed in comparable dhāraṇī amulets, such as those by Xu Yin and Li Zhishun or those in the Pelliot Collection (MG 17689). However, the Xiasha amulet shares this exact script orientation, suggesting that the Hangzhou amulet may belong to the same production tradition or scribal lineage. This unique layout may indicate regional variation, a specific ritual function, or the stylistic preferences of the block carver.

- Esoteric Symbolism and Script Blur: The amulet maker may have viewed the entire dhāraṇī maṇḍala not as a readable script but as a talismanic image designed for divine interaction rather than human interpretation. The indistinct yet Siddhaṃ-resembling characters suggest an intentional shift towards esotericism in Buddhist dhāraṇī talismans. This conclusion is further supported by the initial blurriness of the print, which indicates that the printer was likely more concerned with the symbolic and ritual function of the amulet rather than ensuring the legibility of the text itself.

3.4.3. Xu Yin’s Amulet

Xu Yin’s amulet presents an intriguing case within Buddhist copying practices. Unlike the other amulets discussed, this piece appears to have been purchased or received from Huguosi Temple (護國寺), yet the exact location of this temple remains uncertain. While the amulet was discovered in Luoyang, it is possible that it originated from a Huguosi Temple in Yuncheng, more than 200 km away. However, due to the lack of definitive records, we cannot rule out the possibility that there was a Huguosi Temple in or near Luoyang at the time. This raises broader questions about the movement of dhāraṇī amulets across monastic networks and commercial exchange within religious institutions.

The fact that Xu Yin’s amulet was initiated by a monk also aligns with patterns seen in the Ruiguangsi amulet, where monastic figures played a role in producing and circulating these sacred objects. This suggests that amulet production may not have been purely devotional but may have also involved an element of commercialised religious practice within Buddhist monasteries.

3.4.4. The Ruiguangsi Amulet

The Ruiguangsi amulet, found stored inside a stūpa, presents an unusual departure from the more common wearable format of Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī amulets. Typically, these amulets were designed for personal use, in accordance with the dhāraṇī sūtra’s prescription that they be worn on the body for protection. The stūpa placement of the Ruiguangsi amulet suggests a possible fusion of ritual practices between different dhāraṇīs. Notably, the Sarva Durgati Pariśodhana Uṣṇīṣa-vijaya Dhāraṇī, another protective Buddhist spell, was frequently enshrined in stūpas and pillars, yet it also appeared in wearable amulet forms similar to Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇīs. This cross-influence between dhāraṇī traditions may have contributed to the decision to enshrine this particular Mahāpratisarā amulet within a stūpa.

The involvement of monastic figures in commissioning both Xu Yin’s and Ruiguangsi’s amulets further reinforces the idea that Buddhist amulet production was embedded within monastic economies. Monasteries likely played an active role in facilitating both the devotional and commercial circulation of these sacred objects, allowing dhāraṇīs to reach a wider audience beyond immediate temple communities.

The copying practices observed in these amulets highlight the fluid nature of Buddhist textual transmission. The significant variations in script styles, orientations, and textual fidelity suggest that these amulets were not merely textual reproductions but also ritual objects shaped by evolving devotional and esoteric practices. Whether through the unconventional calligraphic influences seen in Li Zhishun’s amulet or the blurred script of the Hangzhou amulet, these objects reflect the broader landscape of Buddhist textual adaptation and transmission in medieval China.

4. Conclusions

This study has demonstrated that dhāraṇī maṇḍala amulets, long dismissed as ritual ephemera, offer untapped insights into Buddhist textual transmission, scribal adaptation, and cross-cultural exchange. Focusing on four representative examples from the late Tang and early Song periods—those associated with Xu Yin, Li Zhishun, the Hangzhou National Archives, and Ruiguangsi—I have argued that these artefacts not only preserve otherwise unattested versions of the Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī, but also reflect the evolving multilingual landscape and vernacular practices of Buddhism in medieval China.

Though not produced for active recitation or reading, these amulets preserve a wealth of textual data. Their use of Indic scripts, especially Siddhaṃ and Nāgarī, offers material evidence of script circulation stretching between South and East Asia. Moreover, their layouts, bījākṣara arrangements, and use of mantra formulations allow us to reconstruct lost or otherwise unrecorded ritual practices. In particular, the discovery of Nāgarī script in tenth- and eleventh-century Chinese amulets challenges previous assumptions about script standardisation and reveals a continuing dynamism in Sino-Indian textual relations well into the second millennium.

Each of the four amulets examined contributes distinct insights into the philological, ritual, or visual dimensions of dhāraṇī practice:

Xu Yin’s amulet (926–927 CE) provides one of the most complete and clearly dated examples of Mahāpratisarā recensions in Siddhaṃ, featuring carefully arranged bījākṣaras that likely functioned as seals or symbolic representations of the mantras.

Li Zhishun’s amulet (980 CE) presents the sophisticated use of both Siddhaṃ and early Nāgarī and includes rare Chinese-transliterated mantras. It also contains one of the earliest known structured visual mappings of bījākṣaras to Buddhist deities, suggesting highly developed ritual knowledge.

The Hangzhou amulet, although partially damaged, is part of a larger corpus of amulets preserved in the Xiasha Outlet Gallery Museum, revealing regional print networks and unexpected textual parallels that demand a further editorial analysis. It also hints at script visualisation becoming an object of devotion itself.

The Ruiguangsi amulet (1005 CE) stands out for its integration of Nāgarī script and planetary deities showing how Chinese Buddhist imagery absorbed and reinterpreted Indic and Daoist elements in new ritual contexts. Its mysterious ending phrase vidani sulekha opens the door to future research on scribal culture and textual closure.

Looking forward, three research directions are especially pressing. First, a comprehensive editorial study of Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī recensions is now possible, especially thanks to newly discovered amulets in the Xiasha Outlet Gallery Museum. Second, a lexicon or multilingual reference tool for bījākṣaras is needed to map their usage across traditions. These potent syllables recur across Buddhist and Hindu traditions but remain poorly understood outside of performative contexts. Scholarly tools are necessary to decode their meanings, functions, and patterns. Although this study draws primarily on the Mikkyō Daijiten, it is worth noting, as has been suggested in other scholarly contexts, that several other lexical and transliteration resources have also been developed by Buddhist scholars in Japan and Taiwan, as well as by Western researchers working in East Asia. However, many of these are focused on Japanese or Tibetan conventions and are not always suited to the specific script forms found in Chinese dhāraṇī amulets.45 One of the main challenges in building a comprehensive lexicon lies in the significant variation among the sinographs used to render the same Sanskrit syllables. These differences often reflect a mixture of canonical conventions, regional usage, and local scribal practices, making standardisation difficult. Any future tool will need to reflect this complexity while remaining grounded in the material and historical context of the artefacts themselves.

Third, the Mahāpratisarā amulets should be studied alongside other widespread dhāraṇīs, such as the Uṣṇīṣa-vijaya dhāraṇī, which also sometimes appear in maṇḍala-style printed formats. These formal similarities suggest possible shared modes of ritual production between dhāraṇīs. At the same time, greater care is needed in identifying such artefacts. Several amulets currently catalogued as Mahāpratisarā may in fact represent other dhāraṇī traditions: their Sanskrit script is often blurred, their layout generic, and the central iconography ambiguous. A more rigorous reassessment of attribution, textual, and iconographic is essential for building a clearer map of dhāraṇī transmission in medieval China.

Ultimately, this study is not only about four amulets, but of how Buddhist texts were transmitted, visualised, worn, and embedded in the lives of ordinary people. It is about challenging our assumptions regarding what counts as a text, who gets to produce it, and where meaningful textual histories might be found. These artefacts reveal that Sanskrit was not merely preserved but transformed: inscribed and reanimated within Chinese religious life through sound, script, and devotion.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All sources cited in this study are publicly available through referenced archives or institutions. No new datasets were generated.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| d. | died |

| fl. | floruit |

| MPMVR | Mahāpratisarā Mahāvidyārājñī |

| NA | Not applicable |

| Skt. | Sanskrit |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Diplomatic Transliteration of the Dhāraṇī in Xu Yin’s Xylograph (Luoyang)

Circle 1: namaḥ sayaṃ tathāgatānāṃ namo namaḥ sarvaṃ buddha bodhisattvābudhadhamasaṃghebhyaḥ oṃ vipragarbhe oṃ vipulavimale jayagarbhe vajrajvalagarbhe gatigahane gaganaviśodhane sarvapāpavi-

Circle 2: sodhane oṃ guṇavati gagariṇi giri giri gaṃbhari gaṃbhari gaḥ ha gaḥ gogari gāgari gagari gagari gaṃ[?]ri gaṃbhuri gati gati gamadi ai e gurū gurū gurūṇi cale maca samacale jaya vijaye sarvabha-

Circle 3: yavagate garbhasaṃbharaṇi siri siri siri giri ghiri ghiri saṃmaṃtākaṣaṇi sarvaśatrūpramathaniṃ raḥkṣa mama sarva sarvadaṃ ca diri diri vigatā varaṇa bhamānasami suri suri ciri kaṃmari piri jaye jaye jayavahe jayavati

Circle 4: ratnamakuṭamaladharivajravividhavicitravaṣarūmadhāriṇi bhagavati mahāvidyā devi raḥkṣa raḥkṣa mama sarvasathādaṃca saṃmaṃtā sarvatrā sarvapāpaviśodhani hurū hurū maḥṣatrā maladhariṇi raḥkṣa raḥkṣa māṃ sama[anathabhya?][trāmomarayamoṭya?]paramocaya pamarṇatuḥkyebhyā caṃḍi caṃḍi caṃḍi-

Circle 5: ni vegavati sarva[duṣṭini?]varaṇi śatrūmaḥṣapramathanaviruya vaṃhami hurū hurū mārū marū curū curū ayūmarani sūravaramathāni sarvadevatāmujite dhiri dhiri saṃmaṃttā va ghaharatrahaprake suprabhaviśuddhe sarvamāyavisodhāne dhāra dhāraṇi dhāra dhāri sūma rūrūcale cale mahaṣāṃ

Circle 6: murayameha māṃ srivasradhavajayakaṃmale ddhiṇi kṣiṇi varayevacadāṃ kūśe oṃ pradmavisuddhe sodhaya sodhaya buddhe hara hara hiri hiri hurū hurū māṃgalavisuddha mavitrāma[?][?]miṇi vegiṇi vera vera jvare tāmiri saṃmaṃddhāprasāre tāva bhasitā sujvala jvala sarvadevagalā saṃmalaghraṇi

Circle 7: sa[tyi?]vatet tāra tāraya māṃ nagavilokite lahra lahra hraḍa hraḍa kṣiṇi kṣiṇi sarvagrahā bhaḥkṣaṇi pigari piṃgari bumu bumu amu amu vavicale tāra tāra nagavilokiṇi tāravu māṃ bhagavati aṣṭamahābhavebhyā saṃmudrā sāgaramayaṃttāṃmatālagagavetrāṃ sarvatrā saṃmaṃtanani samaṃddhana vajraprakaravajrapasamaṃndhenane vajra-

Circle 8: jvalavisuddhe bhuri bhuri garbhavati garbhaviśodhani kukṣisaṃpūraṇi jvala jvala cala cala jvarini pravaṣatu deva saṃmatena divyodakena amṛtavatāraṇi abhiṣicatumi sugatā vacanamṛtā vara vapūṣe raḥkṣa raḥkṣa mama sarvasatvānāṃca sarvatrā sarvadā sarvabhayebhyi sarvopadravebhyi samopasargebhyaḥ sarvadaṣṭabhayabhitebhyā sarvakali-

Square 1: kalahā vigrahā vivada duḥsvopadarnimitāmbhagatya mama vina sati sarvayaḥkṣaraḥkṣanāgaviharaṇi saraṇi sara mala mala malavati jaya jaya jayatu māṃ sarvatrā sarvakalaṃ sidhyaṃtu me imāṃ mahāvidyā sadhāya sadhāya sa[rva?] maṃ[lā? or ḍā?]lā sadhāni mohāya sarvavighnāna jaya jaya siddhe siddhe a siddhe sidhyi sidhyi budhyi budhyi pūraya pūraya pūraṇi pūraṇi pūrayasi āśāṃ sarvavidyovigattāvate jayātāri jayavati tiṣṭha tiṣṭha saṃmayayanupalaya tathāgatā hṛdaiya suddhe vyivalokaya māṃ aṣṭahimahatada-

Square 2: ṇabhaye sara sara prasara prasara sarvavaraṇa visodhāni saṃmaṃtākara maṃlālavisuddhe vigate vigate vigatāmaṃla viśodhāni kṣiṇi kṣiṇi sarvapāpavisuddhe mala vigate tejavati vajravati trailokyadiṣṭhete svāhā sarvatathāgatā budhābhiṣikte svāhā sarvabodhisattvā bhaṣikte svāhā sarvadevatābhiṣikte svāhā sarvatathāgatā hṛdayadhiṣṭhitā hṛdaya svāhā sarvatathāgatā saṃmaya siddhe svāhā idra idravati idra vyivaloktite svāhā brāhmā brahmadhyiṣite svāhā viṣṇā namaskṛte svāhā mahesvara dittā pūjitāye svāhā vajradhāra

Square 3: vajrapaṇimalaviryādhiṣṭhite svāhā dhṛtāraṣṭrāya svāhā virūha bhaya svāhā virūpaḥkṣaya svāhā veslamalāya svāhā catu mahāraja namaḥskṛtāya svāhā varūṇāya svāhā marūtāya svāhā mahāmarūtāya svāhā ag[ni? or vi?]ye svāhā nagavilokitāya svāhā devagaṇebhyaḥ svāhā nagagaṇebhyaḥ svāhā yaḥkṣagaṇebhyaḥ svāhā raḥkṣagaṇebhyaḥ svāhā gadharvagaṇebhyaḥ svāhā asuragaṇebhyaḥ garūḍagaṇebhyaḥ svāhā kidara gaṇebhyaḥ svāhā ma[hra? or ho?]ra gaṇebhyaḥ svāhā manuṣyebhyaḥ svāhā amanuṣyebhyaḥ svāhā sarvagrahebhyaḥ svāhā sarvabhutebhyā

Square 4: svāhā sarvapretebhyaḥ svāhā piśacebhyaḥ svāhā apasamarebhyaḥ svāhā kūmbhaṇebhyaḥ svāhā oṃ dhurū dhurū svāhā oṃ turū turū svāhā oṃ muru muru svāhā hāna hāna sarvasvātrūṇaṃ svāhā dahā dahā sarvaduṣṭapratraṣṭaṇaṃ svāhā paca paca sarvaprabhyāthika prabhyamitraṇaṃ ye mama ahiteṣiṇaḥ teṣāṃ sarva māṃ sariraṃ jvalaya duṣṭe cittānāṃ svāhā jvarittāya svāhā prajvarittā svāhā dimṛjvalapra svāhā saṃmaṃttā jvalaya svāhā maṇibhaṃ drāya svāha pūrṇa bhaṃdrāya svāhā mahākalaya svāhā matrīgaṇaya svāhā yaḥkṣaṇināṃ svāhā raḥkṣasānāṃ svāhā akasatrīṇaṃ svāhā saṃmudra vasinināṃ svāhā ratricaranāṃ svāhā divasāca-

Square 5: ranāṃ svāhā trimovyicaraṇaṃ svāhā velacaraṇaṃ svāhā avelacaraṇaṃ svāhā garbha hāresvaḥ svāhā garbha mettāraṇi hurū hurū svāhā oṃ svāhā svā svāhā bhūḥ svāhā bhuvaḥ svāhā oṃ bhūra bhūvaḥ svāhā ciṭi ciṭi svāhā vāraṇi svāhā vāraṇi svāhā aṣṭi svāhā tejavaipra svāhā cile cili svāhā siri siri svāhā budhyi budhyi svāhā sidhyi sidhyi svāhā maṃlāla siddhi svāhā maṃṇḍalamaṃddhe svāhā sīmavāndhi svāhā sarvasatrūṇaṃ jaṃbha jāṃbha svāhā staṃbhaya staṃbhaya svāhā cchinda cchinda svāhā bhinda bhinda svāhā bhaṃja bhaṃja svāhā maṃddhā maṃddhā svāhā mohāya mohāya svāhā maṇi vibuddhe svāhā sūrya sūrya sūrya visuddhe visodhāni svāhā caṃdrī sucaṃ-

Square 6: dre pūrṇaṃ caṃdre svāhā grahebhyaḥ svāhā naḥkṣadrebhyaḥ svāhā sāti svāhā sātityiyane svāhā śivaṃkari sātikari pūṣṭikari malamādhani svāhā srikari svāhā sriyamathāvi svāhā sriyajvalani svāhā namuci svāhā marūci svāhā vegavati svāhā|| ||oṃ sarvatathāgatā bute pravara vigatā bhaye samaya svāme bhagavate sarvabhamebhye svāstrī bhaya oṃ muni muni vimuni care calani bhaya vigate bhaya hāraṇi bodhi bodhi bodhaya bodhaya buddhili buddhili sarvatathāgatā hṛdaiya juṣṭī svāhā|| ||oṃ muni muni vimuni vara abhiyicatu māṃ sarvatathāgatā

Square 7: sarvavidyābhiṣekai mahāvajrakavacamudramudritai sarvatathāgatā hṛdaiyadhiṣṭitā vājra svāhā|| || oṃ amṛtā vare vara vara pravara vipujre hūṃ hūṃ phaṭ phaṭ svāhā|| || oṃ amṛtā vilokini garbhasaṃraḥkṣaṇi akaṣiṇi hūṃ hūṃ phaṭ phaṭ svāhā|| || oṃ vajrā[?]ddhāna hūṃ jaḥ oṃ vimarajayavarī amṛte hūṃ hūṃ hūṃ hūṃ phaṭ phaṭ phaṭ phaṭ svāhā|| || oṃ bhara bhara saṃbhara saṃbhara idriyavisodhani hūṃ hūṃ rūrūcari svāhā|| ||

Appendix A.2. Diplomatic Transliteration of Ruiguangsi Indic Xylograph

Line 1: namaḥ sarvatathāgatānāṃ namo namaḥ sarvabuddhabodhisatvābuddhadhamrasaṅghebhyaḥ tadyathā oṃ viprala garbhe vi[?]vimale vimala garbhe jaya ga-

Line 2: rbhe ja vajvā la garbhe gati gahana gagana visodhani sarvapāpa visodhana oṃ guṇavati gagana vicāni gagavi[?]ṇi gagariṇi 246 giri 2 gamari 2

Line 3: gaha 2 gargari 2 gargāri gambhari gaha 2 gati 2 gahi 2 gamana gana guru 2 guruṇi 2 culu 2 cala mūcale jaya vijaye sarvabhaya vigate garbha ga-

Line 4: rbha saṃrasvaṇi giri 2 miri 2 ghiri 2 sarvamantrā karṣaṇi sarvasatrū pramathani rakṣa 2 bhagavati māṃ saparivāraṃ sarvasattvāṃsca sarvanayasaḥ sarvo padrā-

Line 5: vebhyaḥ sarvavyādhibhyaḥ ciri 2 diri 2 viri 2 dhiri 2 vigatā varaṇa vināsani muni 2 cili 2 kamala vimale jaya jaya vahi jayavati bhagavate

Line 6: ratnamakuṭamālādhāriṇivaruvivadhavicitraveṣadhāraṇi bhagavati mahāvidyadevi rakṣa 2 bhagavati māṃ saparivāraṃ sarvasattvāṃsca samantā

Line 7: sarvatra sarvapāpavisodhani huru 2 rakṣa 2 bhagavati māṃ saparivāraṃ sarvasattvāṃsca nathānatraṇānaparāyaṇana parimocaya sarvaduḥkhebhyaḥ caṇḍi 2 ca-

Line 8: ṇḍini 2 vegavati sarva duṣṭanivāraṇi vijaya vāhina huru 2 muru 2 curu 2 ayūḥ ṣālani suravaramathani sarvadevagaṇapūjite dhiri 2 mama

Line 9: sarvalokite prabhe 2 suprabhe visuddhe sodhaya suddhe sarvapāpe visodhane dhara 2 dharaṇi dhari sumu 2 sumu 2 rurucale cala 2 [?]ya duṣṭāṃ puraya ā-

Line 10: sā srīvasudhare jayakamale kṣiṇi 2 varadīkuse oṃ padmavisuddhe sodhaya 2 suddhe 2 bhara 2 bhiri 2 bhuru 2 maṃgalavisuddhe pavitramukhikhaṅgire

Line 11: 2 khara 2 jvaleta sikhare samantāprasāritā vabhāsitā suddhe jvala 2 sarvadevagaṇasamākarṣaṇi satya vātara 2 tāraya oṃ bhagavata māṃ sapa

Line 12: rivāraṃ sarvasattvāṃsca nāgavilokite laru 2 hutu 2 kiṇi 2 kṣiṇi 2 ruṇi 2 sarva graha bhakṣaṇi piṅgale 2 cumu 2 mumu 2 cuvicare 2 nāgavi-

Line 13: lokite tara yatu bhagavate māṃ saparivāraṃ sarvasattvāṃsca aṣṭamahādāruṇabhayebhyaḥ sarvatra sarvattena disantinavajraprakarāvajrapāsavandhanina-

Line 14: vajrajvālavisuddhe bhuri 2 bhagavati garbhavati garbhavisoddhani kukṣismāpūraṇi jvāla 2 cala 2 jvāleni varṣatu divaḥ sarvattena divyodakena amṛta-

Line 15: varṣaṇi devāvatāraṇi abhiṣiñcantu māṃ sagativāraṃ sarvasattvāṃsca sugatā vara vacanāmṛtava-

Line 16: rapūṣe rakṣa 2 bhagavati māṃ saparisarvasattvāṃsca sarvatra sarvadā sarvabhayebhyaḥ sarvopadrāvebhyaḥ sarva-

Line 17: vyādhibhyaḥ sarvaduṣṭabhayabhūtebhya sarvakalakālāhavigrahavivādā duḥsvapardadunimittā maṃgalapā-

Line 18: pavisodhani sarvayakṣarakṣasanāgavidāriṇi cala 2 vala vate jaya 2 jayavnatu māṃ sarvakā-

Line 19: laṃ sidhyantu me[?]yaṃ maṃhā vidya sādhaya 2 māṇḍalaṃ ghātayaṃ vighnā jaya 2 siddhya 2 buddhya 2

Line 20: pūraya 2 puraṇi 2 puraṇi āsāṃ sarvavidyoṅgatattejaya jayotari jayakari jayavati tiṣṭha

Line 21: 2 samayam anupālaya sarvatathāgatā hṛdayasuddhe vyāvalokaya bhagavati mama saparivāraṃ sarvasa-

Line 22: ttvāṃsca aṣṭamahādāruṇabhayeṣu sarva māṃ paripūraya trayasvamahābhayebhyaḥ vārāṇi sarvabhayeṣu

Line 23: sara 2 prasara sarvavaraṇavisodhani samantākāramaṇḍalavisuddhe vigatamala sarvamalaviso-

Line 24: dhani kṣiṇi 2 sarvapāpavisuddhe malavigate tejovati vajravati tralokyā diṣṭhānādiṣṭhe te svāhā

Line 25: sarva tathāgatā gatā mūrddhābhiṣikte svāhā sarvabuddhābodhisattvābhiṣikte svāhā sarvatathagatā hṛdaye suddha svāhā sarva

Line 26: devatābhiṣikte svahā sarva tathāgatā hṛdayādhiṣṭhita hṛdaye svāhā sarva tathagatā samayasiddhe svāhā indre

Line 27: indravati indravyāvalokite svāhā brahme brahmādhyūṣikte svāhā viṣṇunamaskṛte svāhā mahesvaravanditā pūji-

Line 28: tāyai svāhā_ rāṣṭrāya svāhā virūdhakāya svāhā virūpakṣaya svāhā vaisravanāya svāhā caturmahārājana-

Line 29: maskṛtāya svāhā yajmāya svāha yamrapūjite namaskṛtaya svāhā varuṇaya svahā mārutāya svāha mahāmahāmaru-

Line 30: tāya svāhā agne svāhā vayava svāhā nagavilokitāya svāhā devagaṇebhyaḥ svāhā nāgaganebhyaḥ svāhā yakṣaga-

Line 31: ṇebhyaḥ svāhā rakṣasagaṇebhyaḥ svāhā gandharvagaṇebhyaḥ svāhā asūrāgaṇebhyaḥ svāhā kinnā-

Line 32: rāgaṇebhyaḥ svāhā mahoragagaṇebhyaḥ svāhā manuṣyebhyaḥ svāhā amanuṣyebhyaḥ svāhā sarvagrahebhyaḥ svāhā sarvabhute-

Line 33: bhyaḥ svāhā sarvapretebhyaḥ svāhā sarvapasmārebhyaḥ svāhā sarvakumbhaṇḍebhyaḥ svāḥā oṃ dhuru 2 svāhā oṃ turu 2 svāhā oṃ ku-

Line 34: ru 2 svāhā oṃ curu 2 svāhā oṃ muru 2 svāhā hana 2 sarvasatru svāhā daha 2 sarvaduṣṭaṃ svāhā paca 2 sarvapabhyarthikaprabhyamitrāṃ svāhā ye mama u hetiṣiṇas teṣāṃ sarīraṃ jvālaya sa-

Line 35: rvaduṣṭacittārāṃ svāhā jvalītāya svāhā prajvālatāya svāhā dipujvālāya svāhā vajra jvālāya svāha samantā jvālāya svāhā maṇibhadrāya svāhā pullābhadrāya svāhā kālāya svāhā ma-

Line 36: hākālāya svāhā mātṛgaṇaya svāhā yakṣiṇināṃ svāhā rākṣasīnāṃ svāhā pretapisācadākinināṃ svāhā ākāsamatrīṇā svāhā samudravāsinīnāṃ svāhā rātṛcatrāṇaṃ 2 svāhā

Line 37: divamācarāṇaṃ svāhā grisa[?]acarāṇaṃ svāhā velācarāṇaṃ svāhā āvelācarāṇāṃ svāhā garbhahārebhyaḥ svāhā garbhahāraṇebhyāḥ svāhā garbhasandhārāṇi svāhā huru 2 svāhā

Line 38: oṃ svāhā svaḥ svāhā bhuḥ svāhā tuvaḥ svāhā oṃ bhurtuvaḥ svāhā ciṭi 2 svāhā viṭi 2 svāhā dharaṇaya svāhā agni svāhā tejā vapuḥ svāhā cili 2 svāhā sili 2 svāhā

Line 39: giri 2 svāhā dukṣa 2 svāhā tikṣa 2 svāhā maṇḍalā siddhe svāhā maṇḍalā bandhe svāhā sīmavandhe svāhā sarvasatrūr bhajeyaṃ 2 svāhā jagna 2 svāhā cchinda 2 svāhā bhinda

Line 40: 2 svāhā bhañja 2 svāhā vandhu 2 svāhā jambhaya 2 svāhā mohaya 2 svāhā maṇivisuddhe svāhā sūya sūya visuddhe svāhā visodhani svāhā candre 2 sucandreṇa _ svāhā

Line 41: grahebhyaḥ svāhā nakṣatrebhyaḥ svāhā viṣebhyaḥ svāhā sivebhyaḥ svāhā sānti svāhā svastāyana svāhā sivaṃkāri svāhā sāntikari sāṣṭikari svāhā valadhani

Line 42: svāhā valavarddhani svāhā srīkāri svāhā srīvarddhani svāhā srījvalani svāhā namuci svāhā muci svāhā maruci svāhā vegavati svāhā|| ||oṃ sarvatathāgatā mūrttipravara-

Line 43: vigatā bhaye samayasvama bhagavati sarvapāpaṃ svāsta bhavatu mama sarvasattvānāñca muni 2 cari 2 cala 2 ne bhayavigate bhayahariṇi bodhi 2 bodhaya 2 buddha

Line 44: li 2 sarvatathāgatā hṛdayajuṣṭi svāhā|| oṃ muni 2 vare abhiṣiñcātu māṃ sarvatathāgatāḥ sarvavidyābhiṣekaiḥ mahāvajrakavacamudrataiḥ sarvatathāgathā hṛdayadhi-

Line 45: ṣṭi vajre svāhā|| atra sarvapadmaḥ siddhaḥ sarvakammakagasuṇaḥ|| oṃ amṛtāvara 2 pravaravisuddhe hūṃ hūṃ phaṭ phaṭ svāhā|| oṃ amṛtavilokini garbhasaṃrakṣaṇi

Line 46: akarṣaṇi hūṃ hūṃ phaṭ phaṭ svāhā|| oṃ aparājitā hṛdaya oṃ vimali jayavā(?) amṛte hūṃ hūṃ phaṭ phaṭ svāhā|| oṃ bhara bhara sambharā indriyavalavi-

Line 47: sodhani hūṃ hūṃ phaṭ phaṭ rurucale svāhā||oṃ amoghavairocanamahāmudrāpadmapravarttani hūṃ phaṭ svāhā|| oṃ pravathani svāhā|| vidarbhi sulekha

Notes

| 1. | These amulets are those that are discovered in the Chinese context, typically produced as single-page, circular or square-shaped objects, often surrounding a central figure such as the bodhisattva Mahāpratisarā. Other figures—such as the devotee or deities like Chishengguang (Chinese: 熾盛光佛)—also occasionally appear. It is worth noting that dhāraṇī manuscripts were also commonly produced in palm-leaf format, especially in a more Indian context, which could sometimes function as protective or ritual items. However, these differ materially and iconographically from the maṇḍala-style amulets under discussion in this article. |

| 2. | Gergely Hidas, “Dhāraṇī Sūtras”, The Definition of Dhāraṇī sūtra. Additionally, South Asian dhāraṇī sūtras do not necessarily have the word dhāraṇī in their title. |

| 3. | (ibid., 166; ; ; ), provide further explanation and distinguishment between Vajrayāna and Mantranaya. |

| 4. | Reconstructed Sanskrit name: *Ratnacintana or *Maṇicintana. For information on the construction process, see (). |

| 5. | This is recorded in the Taishō Tripiṭaka, numbered T1154. |

| 6. | 至十八年庚午[…]沙門智[…]又於舊隨求中更續新呪 “Until the eighteenth year of Kāiyuán (開元, 730 CE), Buddhist monk [Vajra]bodhi updated new spells to the old suíqiú (隨求, pratisarā dhāraṇī)”. T2154_.55.0571c11. |

| 7. | See (), esp. p. 59. |

| 8. | This is recorded in the Taishō Tripiṭaka, numbered T1153 and T1155. |

| 9. | Note on manuscripts: manuscripts of the Mahāpratisarā Dhāraṇī Sūtra and the dhāraṇī itself are discovered in a wide range spanning from the south of Asia across the deserts and snow mountains to the very east of this continent. The earliest independent Sanskrit manuscripts of the scripture are written on five fragmentary birch bark manuscripts from Gilgit, which Hidas dates from the first half of the seventh century. Starting from the eighth century and ending in the tenth, a plentiful collection of painted or printed Mahāpratisarā Dhāraṇī amulets is found in Central and East Asia, and those discovered in China are the top focus of this research. Another abundant source of manuscripts, mostly the entire scripture, is discovered in Eastern India and Nepal, where there is an extensive series of Pañcarakṣā manuscripts spanning from the ninth to the twentieth centuries. In addition to this, on page 7 of Hidas’ Mahāpratisarā-Mahāvidyārājñī, he writes “While four of these fragments (GBMFE 1080–1165) most likely contain parts of the MPMVR, the fifth one (GBMFE 3328–3335) does not seem to be the MPMVR itself. Approximating the length of this ms. on the basis of its folio numbers, it seems that this ms. contains a shorter auxiliary scripture of the MPMVR, perhaps a Mahāpratisarā-dhāraṇī.” More recently, Oskar von Hinüber, Klaus Wille, and Noriyuki Kudo identified additional fragments of the Mahāpratisarā from the Gilgit collection, and Hidas published a study and edition of five such folios, demonstrating a previously unrecognised extent of the text’s transmission and its ritual importance within the Buddhist communities of early medieval Gilgit (; ). |

| 10. | Fu Ma recently constructed a critical edition of Uigurian manuscripts in (). |

| 11. | (Ibid, pp. 195–252). In addition to this, this research also consults the Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō’s critical Sanskrit edition of the first and second Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇīs at the end of the text numbered T1153 from Volume 20, in both the Latin translation (IAST) and Siddhaṃ script, an Indic script popular in use for Buddhist Sanskrit writing since the seventh century, and in between the outermost circle and innermost square are four offering bodhisattvas. Transliterations of the first in Chinese characters can also be consulted in T1061, 1153, 1154, and 1155. A Chinese transliteration for both dhāraṇīs is found in T1153. |

| 12. | Other common places where the Chinese write dhāraṇīs are the pillars that also serve dissemination purposes. |

| 13. | The date of the translation of this dhāraṇī sūtra can be found in T2154_.55.0567a08. |

| 14. | The Scripture of the Dhāranī Spirit-Spell of Great Sovereignty, Preached by the Buddha, Whereby One Immediately Attains What Is Sought (Fóshuō suíqiú jí dé dàzìzài tuóluóní shénzhòu jīng, 佛説隨求即得大自在陀羅尼神呪經), T1154_.20.0637b15. English translation from Chinese by (). |

| 15. | “Translated by the Tripiṭaka Maṇicintana of the Great Tang and North India, Kingdom of Kāśmīra, at Tiangong Si (Luoyang)”, T1154_.20.0637b17 and T1154_.20.0637b18 |

| 16. | About why she was not called “empress”, see (). https://aaeportal-com.ezproxy-prd.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/?id=-21856 (accessed on April 2024). |

| 17. | ibid., “Chapter Six: A Woman Alone”. https://aaeportal-com.ezproxy-prd.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/?id=-21857 (accessed on April 2024). |

| 18. | While printing would not experience a full resurgence until later in the Tang dynasty, Wu Zhao’s initiatives set a precedent for Buddhist printing, inspiring rulers such as Empress Shōtoku and influencing the production of dhāraṇī amulets. |

| 19. | (). For more sizes of other samples, see (; ). |

| 20. | For a study of the chronological order of the Mahāpratisarā dhāraṇī amulets discovered in China, see (). |

| 21. | Ma suggests that there is a mistake in writing this term and that it should be guàndǐng (灌頂, a Buddhist ritual that sprinkles water on top of the devotee’s head). From (). |

| 22. | English translation from Chinese, by (). |

| 23. | Whose colophon reads as follows: [Someone from] the Bao’en Temple at Huanhuaxi in Chengdu Fu respectfully creates this print [of Buddhist scripture] (成都府浣花溪報恩寺生敬造此印施). |

| 24. | (; ). The colophon of the Chengdu amulet further supports this, indicating its production and sale: [Chengdu Fu] Chengdu Xian… Longchi Fang… Jin Bian… printed spell for sale (???成都縣?龍池坊???近卞??印賣咒本???). |

| 25. | According to sources: (; ; ; , Dasuiqiu-tuoluoni zhou jing [大随求陀罗尼经咒]; ). |

| 26. | T1154, Fo shuo sui qiu ji de da zi zai tuo luo ni shen zhou jing (佛説隨求即得大自在陀羅尼神呪經), (): The Scripture of the Dhāranī Spirit-Spell of Great Sovereignty, Preached by the Buddha, Whereby One Immediately Attains What Is Sought. Chinese translation from Sanskrit, by Bǎosīweí (寶思惟, Reconstructed Sanskrit name: Ratnacintana or Maṇicintana, d. 721). |

| 27. | T1153, Pu bian guang ming qing jing zhi sheng ru yi bao yin xin wu neng sheng da ming wang sui qiu tuo luo nijing (普遍光明清淨熾盛如意寶印心無能勝大明王大隨求陀羅尼經), The Prevalent Illuminous Pure Flaming Mind-Satisfied Treasure Seal/Gesture Heart of the Scripture of the Great Wish-Fulfilling Dhāranī of Great Illuminous Sovereignty who is Undefeatable. Chinese translation from Sanskrit, by Bùkōng (不空, Sanskrit name: Amoghavajra, fl. 705–74). Amoghavajra’s mid-eighth-century Chinese translation of the entire dhāraṇī scripture could have been titled after the Sanskrit name of this dhāraṇī (T1153_.20.0616a04). The title includes the word xīn (心, heart), which translates the Sanskrit term hṛdaya, the word according to Gergely Hidas’s “Dhāraṇī Sūtras”, meaning that it is “in a concise form… containing the essence (hṛdaya) of a longer text, said by tradition to have existed at some time in the (perhaps mythical) past”. This indicates that the title could have only been the name of the dhāraṇī instead of the dhāraṇī sūtra. |