Abstract

The very latest scholarship on the Swiss Reformation has urged us to resituate the conceptual origins and first articulations of a Reformed Covenant theology in the Zurich of Zwingli, Jud, Pellikan, and Bullinger, rather than in the Geneva of Calvin and Beza. Using insights from the recent literature of early modern memory, book history, and art history, this article provides a critical new reading of the preface, text, and paratext of the 1531 folio edition of the Zurich Bible. In doing so, it elucidates how, working with a humanist conception of historical memory, an early Reformed Covenant theology was articulated through its rhetorical juxtaposition of an imagined Israel and Rabbinic Judaism. In line with recent work on the role of historical models in early Reformed Bible culture, I contend that the language of historical memory holds the key to understanding this Reformed rearticulation of Covenant theology and its intended effect on readers of the Zurich Bible. Insights from this reading shed light on the Zurich origins of Reformed Christianity’s ambivalent history of defining itself vis-a-vis an imagined Israel and Rabbinic Judaism, with implications for understanding Protestant discourses on Israel, Judaism, idolatry, antijudaism, and antisemitism.

1. Introduction: What Did Memory Mean to Zwingli and the Zurich Prophezei?

Huldrych Zwingli’s Reformation was driven by memories of Israel that emphasized different but related historical models over the course of its development.1 Jack Cottrell (1971, 1975) and Achim Detmers (2001) have argued, for example, that Zwingli responded to an array of political exigences by emphasizing a shifting array of Israelite models. These models were tied to the ways in which Zwingli believed that the Abrahamic Covenant functioned as a unity that bound together the Old and New Testaments. From 1518 to around 1525, when traditional Catholics were his primary antagonists, Zwingli juxtaposed the Levitical priesthood and Mosaic Law with Christ and the Gospel to argue against priesthood, transubstantiation, and the sacrificial character of the Mass. In the later 1520s, when faced with the increasing threat of Anabaptist separatism, Zwingli asserted an essential continuity of the Covenant that required allegiance to the state church of Zurich and legitimate temporal authority, an allegiance that to his thinking reembodied the integrated religious and political polity of Israel. Carlos Eire (1986), moreover, pointed out long ago that during the early phases of the Zurich Reformation, the iconoclastic sentiments that targeted the fabric of traditional worship in Zurich were cast as a “war against the idols,” a conscious reenactment of Israelite campaigns against the Canaanite cults that had suppressed worship owed through the Covenant to the Hebrew God alone. Much more recently, Pierrick Hildebrand (2022, 2024) has written persuasively of a decided ‘Covenantal turn’ in Zwingli’s historical imagination and preaching around the year 1525, during which the Israelite Covenant grew ever more central to the reformer’s justification for the theological and liturgical innovations of the Zurich church.

Armed with these older and more recent realizations about the centrality of Israelite models in the development of the Zurich Reformation, and cognizant of the latest insights on the unique nature of early modern memory, it remains for us to continue reappraising the early products of Zurich’s Bible culture through the lens of historical memory. Yet, given its notorious elasticity, why should we use the language of historical memory?

Employed with precision and qualification, the language of historical memory provides the most compelling way of understanding the processes by which Zwingli and his Prophezei colleagues selected and implemented their Israelite models. As Judith Pollmann (2017) has observed, in an era in which successful claims to custom and antiquity conferred legitimacy in nearly every facet of life, being able to skillfully rearticulate one’s claim to the authority of the past, always with a mind towards its bearing on an evolving set of social circumstances, proved a critically necessary skill. The normative authority of the past, Pollmann rightly asserts, was the defining feature of early modern memory, which we have since lost to modernity. The charge of novelty, therefore, especially in matters of religion and temporal authority, was an especially potent critique. Accordingly, the intellectual and social phenomena that social scientists, historians, and literary scholars would now describe as historical memory were central to early modern claims to the authority of the past, even if, as Pollmann and others have explained, the concept of memory itself meant a few different things to early moderns wrestling with historical models.

Here follows the necessary precision and qualification of my use of the language. Let me do so by addressing a series of questions; what exactly did memory mean to Zwingli and the Prophezei such that it played such a central role in their reshaping of medieval Christianity, and concurrently, of a new vernacular Bible that reflected the revised historical bases of their Covenant theology? How did the most carefully crafted masterpiece of early Reformed Bible culture—the 1531 folio edition of the Zurich Bible—reflect Zwingli and the Prophezei’s Covenant theology in terms of a historical memory potentially familiar to both the Swiss Reformation and our own, more socially scientific and media-driven methods of understanding how useful visions of the past are continually reconstructed?

For Zwingli and his Prophezei colleagues, the concept of memory (memoria) was more than just a way to refer to the psychological faculty of storage and recollection, a faculty that they would have learned about through Aristotle’s De Memoria et Reminiscentia, scholastic faculty psychology, and the mnemonic devices of the ars memorativa. They certainly employed these learned psychological and mnemonic concepts, however, as university students and as skilled preachers and pedagogues. As we shall see, their consideration for the shaping of semantic memory would play a role alongside what we would now describe as historical memory in the paratextual commonplaces in the 1531 Zurich Bible. In fact, by the early Reformation, theories of memory had become much more expansive than mere considerations of the semantic. As David Bloch (2007) has observed, Aristotle’s precise definition of memory as the product of past sensory experiences and the imagination did not survive his scholastic commentators, who synthesized his definition with the more expansive theories of Augustine and the common uses of memoria in Latin literature.

Subsequently, through the revival of its classical and patristic usages, what I would call a humanist conception of memory was heavily influenced by Augustine. Reading beyond the Confessions and De Trinitate, the two works that laid out his theories of memory most explicitly for the reformers, Kevin Grove (2021) has argued that Augustine’s sermons laid the groundwork for social and historical understandings of memory that went beyond the individual faculty psychology presented in these two well-known doctrinal works. For Zwingli and his colleagues, therefore, well versed in the Augustinian canon and Latin literature, the concept of memory also carried a conventional set of social connotations and transformational potentialities that modern theories have largely jettisoned; memory was not only a psychological faculty of the individual mind, or as Augustine described it in Book X of the Confessions, as both a container and a thing contained, reconstituting impressions of the past gained from sensory experiences in the mind’s eye. Instead, Zwingli and the Prophezei, and for that matter, their frequent inspiration Erasmus (Christ-von Wedel and Leu 2007), followed Augustine in thinking of memory as a social and historical phenomenon that could produce a real reembodiment of the past in the present, even if that which was recalled was subject to adaptation in its reembodiment.

In other words, following Augustine, Erasmus and the Zurich reformers he inspired placed memory both in the psychological realm of the immutable, as a treasury of past sensory experiences and images, and in the realm of the philosophically real and mutable, with its ability to reembody historical models adapted to an evolving set of social circumstances. To be sure, as sophisticated students of history written in the humanist mode, that is to say, with a mind towards extrapolating useful exemplars, Zwingli and his colleagues were acutely aware of historical differences, especially when writing in the declensionist mode. Yet, they fervently believed that historical differences could be overcome by the power of memory to transform the social realities of the present through the careful emulation of historical models. In this too, they followed Erasmus in distinguishing imitatio (imitation) from emulatio (emulation); historical difference made merely imitating historical exemplars an exercise in social futility or narrow obscurantism. Erasmus, for example, made this clear in his ridicule of literary slavishness to the classics and the conventions of Ciceronian rhetoric. Careful emulation, on the other hand, implied an awareness of historical difference and put into practice the humanist principle of accommodatio, or the tailoring of rhetorical strategies to suit particular audiences separated by time, space, language, and culture. As a result, the biblical past in se could never be recovered, but the virtues of its model exemplars could be recovered and reembodied anew.

Modern theories of memory, whether semantic or socially scientific, have since jettisoned these philosophically real connotations and socially transformative potentialities. When scholars speak of historical memory in early modernity, therefore, it serves at best as a kind of necessary heuristic. Erasmus and the Prophezei rarely used the term memoria in reference to the biblical past, and yet, as I hope to show through his article, the transformative power of memory was central to their plans for the reform and renewal of biblical culture. It was a habit of thought that operated, so to speak, as an engine under the hood, and its impact can be seen in the preface, text, and paratext of the 1531 Zurich Bible.

The reformers’ reticence about the concept of memory in the abstract stands to reason. The social and historical vocabulary of memory had not yet developed along modern lines, even if analogous concepts like fama (fame, reputation) and monumentum (trace, monument, reminder) were prevalent in humanist discourse. Yet, I do not wish to assert that modern theories of memory, which have since lost philosophically real connotations and socially transformative potentialities, can offer nothing to an understanding of early modern memory, but rather, that the two conceptual constellations must be brought into a working harmony to produce new insights into early Reformed Bible culture.

Working with Pollmann’s (Kuijpers et al. 2013; Pollmann 2017) assertion about the normative authority of the past in early modern memory and Aleida Assmann’s (2011) model of an early modern memory wherein labile visions of history were primarily shaped by creatively anachronistic texts and artwork, while at the same time recapturing a humanist understanding of memory as a phenomenon that could produce a real and socially transformative reembodiment of the past in the present, I hope to contribute to a new direction in the study of the Swiss Reformation that accords with the recent work of Bruce Gordon (Gordon 2014, 2021; Gordon et al. 2014), Luca Baschera (Gordon et al. 2014), Christian Moser (Gordon et al. 2014), Daniel Timmerman (2015), and Pierrick Hildebrand (2022, 2024). Each in their own way has highlighted the tremendous importance of evolving historical models and memory in shaping the biblical culture of the Swiss Reformation.

This article therefore highlights how Zwingli and the Prophezei’s Reformed Covenant theology was articulated through juxtaposing memories of Israel with a repudiation of Rabbinic Judaism in the 1531 Zurich Bible, the first complete Protestant edition in a German dialect and a masterpiece of Renaissance translation, illustration, and printing. I begin by providing the most thorough analysis of Zwingli’s preface yet available in English, with an eye toward elucidating how he marshaled memories of Israel and Rabbinic Judaism as respective models and foils for Reformed Christianity. I then demonstrate how the 1531 Zurich Bible’s masterful image program and paratextual commonplaces, which were crafted out of a consideration for shaping both semantic memory and what scholars would now describe as historical memory, inculcated a Reformed Covenant theology that underwrote Zwingli’s expansion of the Abrahamic Covenant to Swiss Christians and his ‘reformation’ of the Eucharist into the Lord’s Supper. A new reading of this particular ‘reformation of memory’ in the 1531 Zurich Bible helps us to better understand Reformed Christianity’s foundational and ambivalent history of defining itself vis-a-vis imagined Israelite models, and the utility of the language of historical memory in understanding the transformative historical imagination of early Reformed Covenant theology.2

2. Covenant Theology and Reformed Memory in Zwingli’s 1531 Preface

Brought together through friendship and common cause, Zwingli, Jud, and Pellikan brought different modes of expression, linguistic talents, and temperaments to bear in their collective translation of the 1531 Zurich Bible.3 Zurich’s premier printer, Christoph Froschauer, was an early supporter of Zwingli’s Reformation who sought to make his own mark on the world through the technical prowess and refined aesthetics of his productions. Yet, through the 1531 folio edition, they presented their nascent church with a unified vision of historical memory grounded in the belief that the Israelite past was an ideal source of theological, political, and ecclesiological models. The Zurich Prophezei, so named for their emulation of the Old Testament prophets and regular public expositions of the biblical texts, were well aware that their Israelite models were abstractions formed from circumstances that could never be recreated. Yet, their emulation of exemplary models in biblical–historical time held the key to profound social transformation.

As far back as 1519, Zwingli had set the tone for their translation project by rejecting the cyclical and seasonal lectionary of the medieval Church in favor of preaching through the Bible as a continuous historical narrative, from the Abrahamic Covenant of Genesis 15 to its New Testament fulfillment in Christ. Preaching lectio continua rather than lectio divina, Zwingli revealed a timeless God who nevertheless revealed himself through history, forming relationships and unfolding His plan for the salvation of humanity through direct interventions in particular times, places, and peoples. By eschewing the cyclical and seasonal historical consciousness fostered by the medieval lectionary, Zwingli had introduced a new and deeply historicized conception of biblical time to the people of Zurich, a conception, moreover, which appealed to his burgeoning sense of Swiss patriotism.

For Zwingli, in fact, it was by no means an imaginative leap to view the Swiss as a people chosen by God for a special relationship like the Israelites of old. The martial signs were apparent; the Swiss were among the finest soldiers in Europe and had repeatedly humbled their Burgundian and Habsburg enemies. Like many of his compatriots, Zwingli took immense pride in the successful resistance of the Swiss, traditionally a rural people isolated by the Alps, to the would-be aristocratic rule of the Habsburgs. The reputed invincibility of Swiss pikemen on the Renaissance battlefield, which helped to safeguard the independence of the Old Swiss Confederation, was the product of a highly militarized society that could afford few other opportunities to young men but to hone their martial prowess through mercenary service in foreign armies (Gordon 2002, 2021)

According to the patriotic legend of Bruder Klaus (d. 1487), however, God had granted invincibility and independence to the Swiss in recognition of their primitive godliness and piety. For his part, Zwingli shared Klaus’ estimation of the Swiss as a chosen people, but through first-hand experience as a battlefield chaplain in the Italian Wars, he began to see in his compatriots a reembodiment of the fallen Israel. They too had turned away from the defense of native liberty in the service of foreign powers like the French monarchy and the Roman papacy. They too had forgotten their primitive godliness and embraced a ‘false religion’ taught through the sacrifice of the Mass, the cult of the saints, and late medieval biblical culture. Publishing the 1531 Zurich Bible in Alemannic German represented part of Zwingli and the Prophezei’s effort to return the Swiss to the primitive godliness of their original Covenant, or even to surpass it, by cutting the foreign ties that bound them not only militarily and politically, but also linguistically and spiritually.

By replacing Jerome’s traditional Vulgate prefaces, however, translations of which had been a fixture of the late medieval German Bible, Zwingli gave himself a crucial task in his introductory preface; in an era when successful claims to custom and antiquity conferred critical legitimacy, the reformer had to justify the work of translation and adaptation with an appeal to authoritative models from the biblical past.4 Faced with militant hostility from Catholics, Lutherans, and Anabaptists alike, Zwingli had to answer a question critical to an audience embracing the Reformed faith or questioning its right to violently suppress traditional religion. Namely, was the church in Zurich a heretical novelty, or was it the restoration of an ancient lineage, and through the transformative social power of memory, the reembodiment of Israel and the early Church for a new age?

To answer this question, Zwingli set out to explain how the church in Zurich emulated the faithful Israelites of the Old Testament and avoided the “corruption and idolatry” of an imagined Rabbinic Judaism. In performing what modern theorists would call a critical and sophisticated ‘work of memory,’ Zwingli simultaneously differentiated the church in Zurich from the Catholic Church that it had supplanted, the German Lutheran movement, and the ‘heretical’ Anabaptists. As is well known, the Anabaptists’ own historical memory of Israel emphasized a collective identification with a persecuted ‘Israel in exile,’ one that seriously threatened to tarnish Zurich’s claim to historical legitimacy.

Aligning Zurich with an orthodoxy dating back to the early Church’s struggle against Marcion of Sinope (d. 160), Zwingli asserted that God’s Covenant with the Israelites was vital to understanding and living the Christian faith.5 Rebuking the heresy of Marcion, who had held Christ to be a distinct being from a ‘vengeful’ Old Testament demiurge, and consequently, that the Old Testament Law was obsolete in light of the Gospel, Zwingli explained that God had given the Old Testament not just to the Israelites but “to humanity so that his power, wisdom, benevolence, and justice would be known, such that no one should dismiss it as an antiquated text that has been superseded and no longer applies to us. Rather, it is the proper scripture and evidence of God in which the Lord Jesus can be known to Jews, wherein he called upon them to seek through and find him. Whosoever denies the Old Testament, denies Christ also, and whosoever despises it, despised God and Christendom before it”.6 Here we can detect not only Zwingli’s belief in the universality of the Old Testament, especially its insights into the fundamental characteristics of God, but also the enduring utility of its prophetic books in proving the messiahship of Christ to Jews; jettisoning it as “antiquated” or “superseded” would obscure the Zurich church’s Abrahamic and prophetic foundations, and undermine its historical legitimacy.

Serious questions remained, however; how exactly was the ancient Hebrew religion of Israel a model for Reformed Christianity? What elements were appropriate only for the Israelites, and what could be emulated for the reformation of Zurich? Certainly, the hereditary Levitical priesthood and its regime of sacrificial penance were not to be revived in light of the Gospel and its emphasis on the universality of God’s salvific plan for the Gentiles. Instead, the Covenant that began through Abraham’s election to faith was to form the renewed local basis of a universal Church that had for too long, through the sacrifice of the Mass and cult of the saints, lapsed into the sacerdotal model of the Levites.

To this end, Zwingli explained how the benefits conferred to the Israelites through Abraham’s faith had extended to a chosen elect, known only to God, through their faith in the universal Christ: “In the Old Testament, we also learn about the eternal Providence and Election of God, in which many are included, such as Abel, Noah, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Joseph, etc. Many others were shunned like Cain, Ishmael, and Esau. Thus, God showed his mercy (however difficult to understand) through his high and chosen Son, through whom he restored and sanctified the world, and in whom all peoples are blessed and made holy, namely the son of Abraham, that is, in his beloved Son Christ, who according to his humanity was a son of Abraham. Therefore, the line of the Covenant passes through the same Son to all the pious of the world who recognize and believe in him”.7 Here Zwingli articulated a new form of faith-based Covenant theology, one which operated through the inscrutable election of individuals known only to God. As Detmers (2001, pp. 147–48) has explained, Zwingli’s election included Old Testament figures who, though predating Christ, could have only been saved through faith in Him, even if they could have only known Christ in the form of a promised Messiah and in the juxtaposition between Law and Gospel. Zwingli’s Reformed articulation, moreover, stood in stark contrast to the medieval Church’s model of a communally imputed grace that, while cultivating and praising individual faith, emphasized the necessity of communal intercession.

The elective faith of the Abrahamic Covenant, however, was not the only inheritance of the Hebrew religion that Zwingli considered to be a useful model for Reformed Christianity. Like the Israelites of old, Swiss Christians were prone to stray from a proper understanding of the faith and fail to uphold the moral and ethical standards set forth by the Law. They too were a fallen people exiled from their true home in the heavenly Jerusalem, and they too had fallen into forms of idolatry that were forbidden by the Covenant of faith. They too inhabited a fallen world wherein godly governance was needed to maintain true religion, protect the weak, and dispense justice with the temporal sword. Neither the ancient Hebrew religion nor the early Church had existed outside of the bounds of civil society, and rulers who justly wielded the sword had been integral members of both (so much for Anabaptist separatism and its pacifistic memory of apostolic perfection). Accordingly, Zwingli explained that the repeated fall of the Israelites into idolatry proved that rulers needed to work alongside duly appointed pastor–prophets who were well versed in scripture and ordained by God to advise them on how best to fulfill their roles.

Their ideal relationship was evident in Zwingli’s summation of Kings I and II, in which “the entire downfall of the people originated in evil kings and rulers. In the case of Jeroboam, one sees the tragedy that resulted from a ruler that fell from God and led the people to sin against him. Their downfall was so complete, that no warning or punishment (understood, from the prophets) sufficed until they were led into captivity, first Israel and then Judah, where they were corrupted and scattered throughout all lands. And although God lead them once again out of captivity and into their land, they never again attained their formerly high and exalted state”.8 For Zwingli, therefore, the fate of the Israelites, and by extension their “corrupted and scattered” Jewish descendants, spoke to the need for a symbiosis between godly rulers and the pastor–prophets of the Reformed church. Only then could the Swiss elect root out and destroy the ‘idolatry’ that had overtaken both the ancient Israelites and their own more immediate Catholic forebears. Zwingli had crafted an Israelite model for a new kind of spiritual authority in the context of a Swiss Reformation fueled by anticlerical sentiment; like the Hebrew prophets of old, Reformed pastor–prophets were to be guided by the Holy Spirit as they interpreted the Bible for the entire political body in the Prophezei and advised its rulers on how to fulfill the Covenant.

In championing the integrated religious and political polity of Israel as a model for Zurich, however, Zwingli was at pains to differentiate the Hebrew religion of the Old Testament from the Rabbinic Judaism of the Diaspora. It was a crucial difference to articulate in light of centuries of elite antijudaism and antisemitism, which held diasporic Jews to be altogether inferior to their biblical ancestors and, alongside the encroaching Ottoman ‘Turks,’ the primary enemies of the Gospel. What did Zwingli himself believe? Laying out Zwingli’s attitude towards Jews, Detmers (2001, pp. 155–59) has explained that Zwingli’s assertion of an essential Covenantal unity between the Old and New Testaments meant that believing Christians had disinherited unbelieving Jews as the “people of God” and “children of Abraham” by their elective faith. After all, not all of Abraham’s children by natural descent had been included. For Zwingli, therefore, the grand course of sacred history disproved the concept of multiple Covenants, and the Diaspora was a sure sign that God had abandoned the great majority of unbelieving Jews in favor of the Church.

In Zwingli’s era, moreover, Rabbinic Judaism was not only a lived religion practiced in select urban centers of the Swiss lands, but it was also a rhetorical and metaphorical tool in the hands of Christian detractors. Christians could be pejoratively labeled ‘Jews’ or ‘Judaizers’ if they performed rites that accorded with Rabbinic traditions, or if they were perceived to be overly reliant upon historical or literal readings in their interpretations of scripture (Austin 2022). Accordingly, by the time that Zwingli wrote the preface to the Zurich Bible in the early months of 1531, his Catholic opponents had long since accused him of ‘Judaizing’ the Christian faith; his preaching on the enduring relevance of Old Testament Israelite models for the church in Zurich, not to mention his movement’s brazen destruction of the material fabric of traditional Christianity, which Rabbinic Jews had also repeatedly denounced as ‘idolatrous,’ had earned him the potently derisive moniker “the Great Rabbi of Zurich” (Gordon 2021, pp. 120, 270). What was needed, therefore, was to set the record straight with a clear public denunciation of Rabbinic Judaism.

Here it is critical to note that, officially speaking, there were no Jews living in Zurich during Zwingli’s Reformation. According to Austin (2022, p. 93), there is no evidence that Zwingli had contact with any Jews, while Zwingli himself tells us that he spoke with a learned Jew named Moses from Winterthur on at least two occasions. Moses apparently visited Zurich twice to listen to the Prophezei unfold the Hebrew scriptures and had sanctioned their Reformed readings (Detmers 2001, p. 157; Gordon 2021, pp. 120, 270). Whatever the truth of Zwingli’s account, engagement with living Jews was beside the point.

Zwingli established the Zurich Bible’s Israelite foundation and rejected the Rabbinic tradition with a two-pronged assault. Summoning what Jeremy Cohen (1999) has called “the hermeneutical Jew,” an early modern ‘ideal type’ socially and doctrinally crafted for Christian polemics, Zwingli maintained that rabbis were doomed to false interpretation through their ‘blindness’ to the messiahship of Christ. In doing so, he, of course, drew upon the Augustinian ‘Doctrine of Jewish witness’ to explain the persistence of Jews and Judaism in an overwhelmingly Christian society; namely, that their ‘blindness’ to the correct Christological readings of the Hebrew scriptures was a hereditary punishment visited upon them for their rejection of the Messiah, but one that fulfilled a positive function for Christians, marking Jews as a protected ‘witness people’ whose continual errors and social subjugation pointed to the truth of Christianity. Here Zwingli reestablished a medieval continuity, quite distinct from Luther’s early apocalyptic hope that the ‘liberation of the Gospel’ would bring forth Jewish conversion on a massive scale. By the 1530s, however, the failure of this mass conversion to materialize led many reformers, including Zwingli and Luther, back to well-established antisemitic tropes (Austin 2022, pp. 43–49, 76).

Zwingli’s second assertion, however, was altogether more novel, although it had some precedence in the bitter anti-Talmud debates of the thirteenth century; Rabbinic interpretative traditions were nothing more than erroneous historical accretions that failed to meet humanist standards of textual fidelity; “Now we wish to assert, that in our translation we have raised few of the points that have been recently devised by Jewish rabbis. It concerns us little what they write in their commentaries, which developed over the course of several centuries, and are so often unlearned and full of fables that it is harmful to read them. Because their own laws are so uninformed (for a blindness lies before their eyes) and all good arts either unknown or completely misunderstood, they are hardly conducive to an explanation or understanding of scripture”.9

Zwingli had marshaled the same methodological argument that critical humanists and reformers had repeatedly used against the textual fabric of medieval Christianity; textual proximity to a divinely inspired source conferred authority to a given translation, not its recourse to an interpretative tradition or historical consensus. Accordingly, by virtue of its proximity to the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, the Greek New Testament was superior to medieval Latin interpreters and commentators, just as the Hebrew Torah and Tanakh were superior to the largely Aramaic Talmud and Targums of the Diaspora. Putting it into terms familiar to both early modern and modern conceptions of memory, Zwingli believed that Reformed Bible culture constituted a more faithful reembodiment of Israel than Rabbinic Judaism; like the medieval Church, rabbis had allowed centuries of ‘human tradition’ to corrupt the biblical foundations of their ancient faith.

Zwingli’s dichotomy between Israel and Rabbinic Judaism also fundamentally shaped the Prophezei’s collective translation strategy, both in terms of their selection of textual sources and their rendering of the biblical languages. Their rejection of the Rabbinic tradition meant that the 1531 Zurich Bible relied upon what the Prophezei considered to be the oldest and most reliable textual sources: the Greek Septuagint and the Masoretic Hebrew Bible. Editorially speaking, Zwingli, Jud, and Pellikan split the difference, so to speak, between the model of an Augustine who had esteemed the Septuagint as authoritative over the Hebrew versions of his day (De doctrina Christiana, Book II, Ch. XV), a practice sanctioned by the wide usage of the Septuagint in the early Church, and a Jerome who had eventually come to privilege what he called the Hebraica veritas (Rebenich 1993).

In keeping with Zwingli’s repudiation of Rabbinic Judaism, however, the reformer was eager to dispel the notion that the Prophezei had given undue reverence to the original Hebrew form, vocabulary, and syntax. By 1531, Zwingli had become well aware that the Reformed emphasis on scriptural authority had evoked in its critics echoes of ‘Jewish literalism,’ a prevalent stereotype that characterized the Jewish faith as erroneously focused on these facets of the text to the detriment of discerning moral and spiritual lessons embedded within it. As a result, Zwingli explained how Prophezei Hebraists like Jud and Pellikan avoided this characteristically ‘Jewish’ approach to the text; “We did not ignore the Septuagint (created long before Christ) but rather esteemed it to be great because in many places the relevant points are completely and properly seen. To be sure, however, the Hebrew is even more esteemed by us as the font and foundation, but not so much according to the letters, but rather according to the intended sense and meaning”.10 Emulating Jerome’s translation strategy in rendering Hebrew and Greek into an accessible Latin, the Prophezei had placed legibility and pedagogical utility over what they saw as an unmerited reverence and adherence to the form of the original Hebrew in the Jewish tradition; “Because no one can translate the unique characteristics of a language into another and retain a utility, it is more appropriate that each language retain its idiom intact”.11

Reflecting what James Kearney (2009) has described as a new kind of Protestant anxiety, produced by privileging the Bible as a conveyer of the ‘immaterial’ Word, but rejecting the text and the book as holy material objects, Zwingli went on to critique the belief that the form of the original Hebrew contained an inherent power, rather like the magical incantations of the Kabbalah that had been celebrated and denounced by prominent Christian Kabbalists. For Zwingli and the Prophezei, however, this magical attitude towards the Hebrew text–object was not only detrimental to producing a good translation, but it was yet another ‘idolatry’ that distracted the Christian faithful from the moral, ethical, and spiritual lessons that scripture conveyed. The language of the Bible was a protean tool that the Holy Spirit had imparted to serve the glory of God, not an idol to be revered for its own sake: “The many harmful superstitions that consider the alteration of syllables and words to be a great sin, we consider to be a proper scourge, and neither a reasonable estimation nor judgment, called for not by necessity but by encouragement”.12

Moving forward, Zwingli also discussed the implications of the Israelite model of an integrated religious and political polity for his approach to rooting out heresy in the Zurich church. Tolerance of heresy had been a virtue neither among the ancient Israelites nor the early Christians, and nor would it be in Zurich. This was especially true in light of Zwingli’s vision of the reembodiment of Israel as an alliance of godly magistrates and pastor–prophets, working together to discipline the political body of Zurich as a simulacrum for the mystical ‘body of Christ.’ Heresy constituted a grave moral and spiritual contagion in this religious–political body, one which invited God’s judgment upon the community if it was allowed to spread unchecked. From the beginning of Zwingli’s Reformation, however, he and his Prophezei colleagues were faced with the rapid growth of an eclectic group of ‘heretical’ dissenters known by their opponents as Anabaptists.

A more faithful reembodiment of Israel, the Anabaptists and their successors claimed, was to be a persecuted minority holding true to the Covenant by practicing a strict morality and living separately from a fallen world. Adherence to the Covenant demanded a faithful ‘re-baptism’ on the part of rational adults, and precluded participation in the compulsion and violence of the state and its established church. In the eyes of their Reformed neighbors, not to mention the vast majority of early modern Christians, these beliefs constituted treasonous and heretical derelictions of civic and Christian duty. From 1525 onward, the state church and the Anabaptists read from the same Froschauer Zurich Bibles as they acted out wildly divergent memories of Israel and the early Church, resulting in executions, exile, and diaspora for the beleaguered Anabaptists (Leu 2005, 2007).

In his 1531 preface, therefore, Zwingli was eager to use the early Church’s struggle against ‘heretical’ interpretations of the Old Testament to repudiate the Anabaptists and distance Zurich from what had become an embarrassing association (Leu 2007). For Zwingli, the Anabaptists were the unfortunate result of the return of widely available vernacular scripture, and their unique reembodiment of the Apostolic life reawakened heresies faced by the Fathers. Like Marcion, they denied the relevance of the Israelite regime and its model of an integrated religious–political polity. Like Augustine in his battle with the schismatic Donatists, Zwingli believed that adherence to the established state church was not optional, and that both sinners and an unknown elect owed it to one another, and to God, to uphold it. As both Cottrell (1971, 1975) and Detmers (2001) have pointed out, Zwingli viewed this obligation as the result of an essential unity of the Covenant across the two testaments, a unity which enabled the Church to reembody a faithful Israel.

Yet, Zwingli’s Anabaptist opponents went further than Marcion and the Donatists in their repudiation of an integrated religious and political polity. For Zwingli, their assertion of a discontinuity in the way the Covenant functioned across the two testaments fostered an illicit political, or ‘carnal’ liberty, one that had not been granted alongside the spiritual liberty gained through faith in a Christ who had not rejected the temporal authorities of his own age but sanctioned them. Zwingli, therefore, denied that their illicit ‘carnal’ liberty, or their desire to live apart from the state church, could be justified by scripture: “...despite the many who read the scriptures to their benefit, there are others who take from it a license to foment strife, disruption, and liberty of the flesh”.13 Zwingli nevertheless maintained that the cost of dealing with the Anabaptists and their erroneous view of the Old Testament was well worth the benefits that vernacular scripture conferred to the Church as a whole: “Others teach people to deny the truth, but that should not stop us from printing and reading good books. It would be like the vine dresser frightening others from the plant because many get drunk from it daily and misuse the noble wine”.14

Zwingli’s preface ultimately served as a skillful ‘work of memory’ that achieved its rhetorical goals. Writing in terms of humanist emulatio and accomodatio, Zwingli called for the restoration of a faithful, pure, and primitive godliness, owed by the Swiss to God via the unity of the Covenant, through the transformative power of historical memory. Speaking on behalf of the Prophezei, his call to reembody a faithful Israel and repudiate the ‘idolatry’ of an imagined Rabbinic Judaism provided a confident foundation for the historical consciousness and collective worship of the Zurich church. In doing so, he defined the contours of inclusion and exclusion in the new Israel and universal Church writ large. Zwingli incorporated the Lutherans and their Bible translations into his vision through the invocation of a linguistically diverse and multipolar early Church, but other competing memories, whether they were held by recalcitrant Catholics, Rabbinic Jews, or ‘heretical’ Anabaptists, were not to be entertained in Zurich. In a more immediate hermeneutical sense, Zwingli’s preface established an interpretative framework of Reformed Covenant theology and historical memory for the texts, paratext, and images that followed it.

3. Reading the 1531 Zurich Bible for Covenant Theology and Reformed Memory

Zwingli’s “noble wine” was delivered in the form of an imposing folio-sized Bible, masterfully crafted by Froschauer to convey the Reformed Covenant theology and historical memory of the Prophezei using the most sophisticated typographical techniques and Renaissance aesthetics. Every element of the 1531 folio edition, from its freshly cut form of Schwabacher type to its substantial paratext and image program, even down to the restrained elegance of its mise-en-page, deliberately served their vision of a Swiss people restored to primitive godliness through the rejection of idolatry and elective faith of the Covenant. In comparison to the humanist Roman type found in internationally marketed Latin Bibles, Schwabacher was a feature of German vernacular Bibles, and, in this context, it carried the cultural valences of a traditional Germanophone ‘Swissness.’ As Gordon and others have pointed out, the text was also stripped of its medieval paratextual framework and centered on the printed page, becoming the focal point of the reader in much the same way that the pulpit and the simple wooden table of the Lord’s Supper did in the churches of Zurich following the removal of traditional altars, shrines, and statuary. The restrained aesthetics of sola scriptura and the material fabric of the Reformed liturgy shaped a holistic experience that reflected Zwingli’s understanding of the Christian religion as a call to Covenantal purity and obedience to the Word (Gordon et al. 2014, pp. 16–18, 23–24).

Largely due to Zwingli’s reverence for the Septuagint, a text that, in emulation of the early Church, the Prophezei read and expounded upon regularly during their meetings at the Fraumünster Church, both canonical and apocryphal texts such as Sirach, Tobit, III-IV Esdras, and III-IV Maccabees were included in the 1531 Zurich Bible. The order of books also followed the Septuagint, distancing it from the Vulgate of the medieval Church and the Rabbinic Hebrew Bible. On the title page, the reader was presented with a frontispiece that illustrated the very reason why the Zurich Bible was necessary in the first place; while humanity had been created for the purpose of worshiping God, through its subsequent temptation, it had fallen short of that purpose and was in need of redemption.

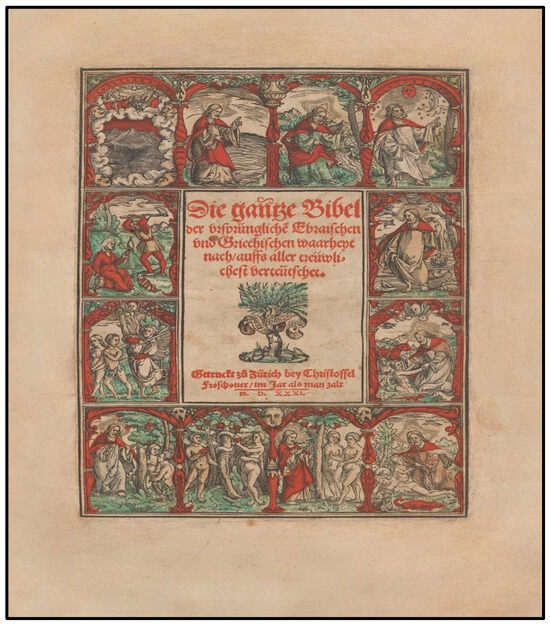

Likely crafted by the Zurich artist Hans Asper (Lavater 1983, p. 1401), the artist responsible for the most influential oil portraits of Zwingli, twelve woodcuts moved the eye through the narrative of Genesis I-V, much like the panel paintings, triptychs, and tapestries, which once decorated Zurich’s medieval churches, explaining the liturgical focus throughout the year (Figure 1). Divided by columns formed from fashionable acanthus leaves and grotesques, classical symbols of regeneration and renewal, the sequence depicted God’s creation of the heavens and the earth, day and night, the animals, Adam and Eve, the temptation of the serpent, and the expulsion from Eden. The final scene depicted Adam tilling the earth and Eve spinning with an infant swaddled at her feet. Now clothed in the working garb of the early-sixteenth century, they mirrored the fallen condition of readers and viewers. The Zurich Bible, however, promised a way to transcend this lamentable inheritance of the Fall by providing salvific knowledge of the Word and historical models for the church and temporal authority which shaped a godly community on earth.

Figure 1.

Title page of the 1531 folio edition of the Zurich Bible, featuring a woodcut cycle depicting the creation and fall narratives of Genesis I-V. Likely created by Hans Asper. Accessed on 6 September 2023. https://www.e-rara.ch/zuz/content/zoom/19291.

Asper’s frontispiece was part of a program of 198 images that supported the scriptural texts they accompanied, enabling readers to envision the biblical past in ways that were culturally legible. The tremendous methodological and technical achievements of Renaissance artistry were brought to bear in their execution by Hans Holbein the Younger, who resided in nearby Basel from 1528 to 1532 and produced 161 of the 198 images used in the 1531 folio edition. A master draftsman, Holbein employed forced perspective to give scenes from the biblical past a vivifying depth and motion. He also rendered biblical figures with the realistic anatomy and posturing characteristic of classical art, in addition to the exquisite detail and sensitivity to emotion characteristic of the Northern Renaissance. Holbein’s images were then skillfully crafted into 86 x 61mm woodcuts by Veit Specklin and integrated by Froschauer’s typesetters within columns of the scriptural text (Lavater 1983, pp. 1404–7). The result was one of the most visually arresting and historically immersive adaptations of the biblical tradition printed in the sixteenth century.

Commissioned specifically for the 1531 folio edition, Holbein’s 118 Old Testament images give us an idea of how the image program functioned to support the Prophezei’s Covenantal theology and historical memory. Once again, the transformative social power of memory was at the heart of their endeavor. As David Price (2021) has recently shown, Northern Renaissance artists such as Dürer, Cranach, and Holbein regularly provided aesthetically sophisticated biblical imagery for humanist and Reformation Bibles in order to serve a specific cultural agenda; these artists were immersed in the same genres of humanist and reformist historical discourse as the leading biblical humanists and reformers.

Artists like Holbein also read their Erasmus as a call for the reform and renewal of biblical culture through skillful emulatio and accomodatio. They applied their talents in the graphic arts to this Erasmian cultural agenda through the emulation and adaptation of classical art forms and techniques. Their connections with scholar–printers such as Froben in Basel and Froschauer in Zurich were critical in developing the visual vocabulary of these humanist and reformist historical discourses and conceptions of memory in the realm of biblical illustration. Through their illustrations, the Bible became the greatest visual monument to the piety and vitality of the classical world. In the context of a largely illiterate and highly visual society, as Scribner (1981) asserted long ago, humanist and reformist illustrations proved much more effective at generating social change than printed rhetoric. Accordingly, Holbein’s understanding of the power of humanist emulatio and accomodatio to effect social transformation accorded with that of Zwingli and his Prophezei colleagues. For his part, however, Holbein expressed it through what Assmann (2011) would describe as creatively anachronistic artworks shaped by historical memory.

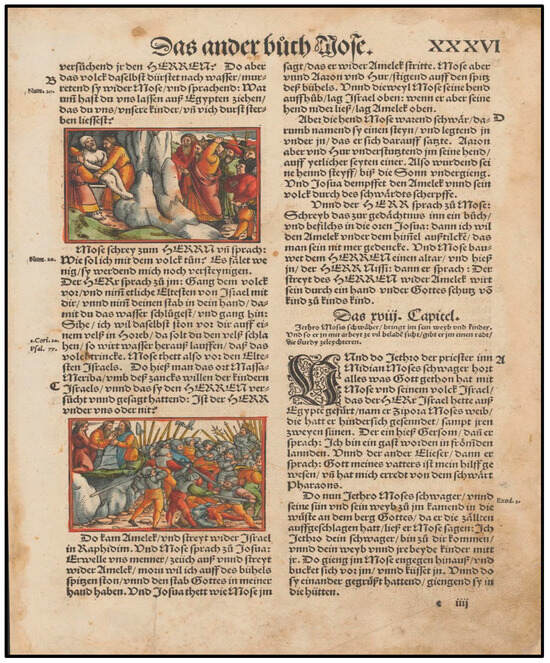

How then did the humanist notions of emulatio and accomodatio manifest in Holbein’s images? While Holbein’s rendering of the Tabernacle, holy utensils, and priestly vestments from Exodus 25–28 are meticulously detailed and accurate to the scriptural text, it was his depictions of the Israelites themselves that best illustrated Zwingli’s prefatory theme of the Swiss as a people who were called to reembody Israelite models of godliness. A note of caution must be proffered here; I do not mean to suggest that only the Swiss could envision themselves in Holbein’s illustrations, after all, they ended up being featured in several Reformation Bibles across Europe, but rather that they were especially well suited to Holbein’s original Swiss and South German cultural context. For example, Holbein’s depiction of the Israelites in battle with the nation of Amalek (Exodus 8) utilized the clothing and equipment favored by Swiss and German soldiers (Figure 2); masses of pikemen jostle in the background, while in the foreground, troops wearing the infantry half-armor of the region wield distinctive Zweihänder and Katzbalger swords against their pagan enemy (Oakeshott 1980). The same could be said about Israelites escorting the Arc of the Covenant in Joshua, as they encircle a Jericho built from Fachwerk houses and crenellated walls. Two images of Gideon’s warriors in the seventh chapter of Judges produced the same domesticated tableau. While it was common practice in Renaissance art to depict biblical figures and scenes in contemporary garb—a practice that speaks to the Bible’s contemporary role as a source of emulatable and adaptable models—the regional and cultural specificity of Holbein’s images would not have been lost on Swiss readers.

Figure 2.

Woodcut of Israel versus the nation of Amalek in Exodus 17; the armies are dressed and equipped as contemporary Swiss or German soldiers. Drafted by Hans Holbein the Younger, woodcut by Veit Specklin. Accessed on 6 September 2023. https://www.e-rara.ch/zuz/content/zoom/1929294.

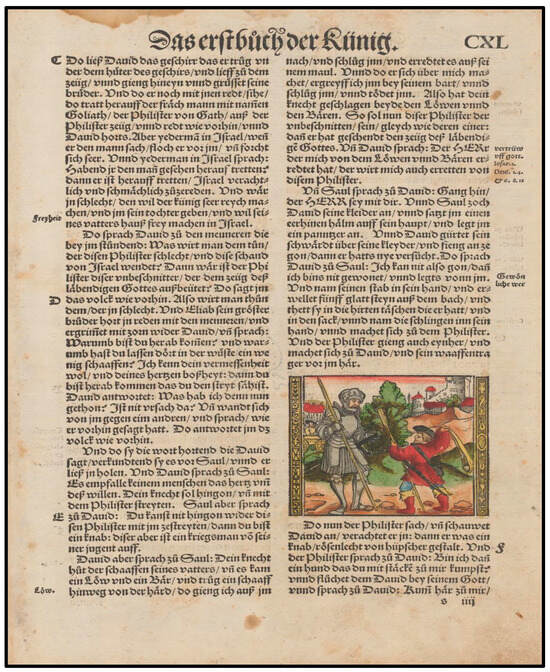

In fact, Holbein’s images told Swiss readers something particular about the Covenant using their cultural expectations. In his depiction of David’s battle with Goliath (I Samuel 17), for example, the towering Philistine wore costly and protective ‘Maximilian-style’ full armor, fashionably rounded and fluted, with square-toed sabatons (Oakeshott 1980). In contrast, the young Israelite was a rustic shepherd warrior with rudimentary weapons (Figure 3). As Goliath mocked his rustic appearance, however, David invoked the might of Israel’s faithful God: “You come to me with sword, spear, and shield. I, however, come to you in the name of the Lord of Hosts, the God of the House of Israel, which you have despised. On this day, the Lord will deliver you into my hand...And all those gathered here will know, that it is not through sword or spear that the Lord aids, for battle belongs to the Lord, and he will deliver all of you into our hands”.15 The lesson to be gleaned was that Israel, both in its ancient and novel Swiss reembodiment, could successfully resist the proud and mighty of the world if God’s Covenant was properly fulfilled through the elective faith of Abraham and his spiritual descendants. Holbein’s regionally and culturally sensitive images were paired with the Prophezei’s translation to support Zwingli’s vision of an age of primitive Swiss godliness that could be restored, in so far as it was possible in time and space, through the emulation and adaptation of heroic Israelite models.

Figure 3.

The Israelite shepherd-warrior David faces Goliath in I Samuel 17, who is dressed in costly and protective Maximillian-style armor, characteristic of nobility. Drafted by Hans Holbein the Younger, woodcut by Veit Specklin. Accessed on 6 September 2023. https://www.e-rara.ch/zuz/content/zoom/1929502.

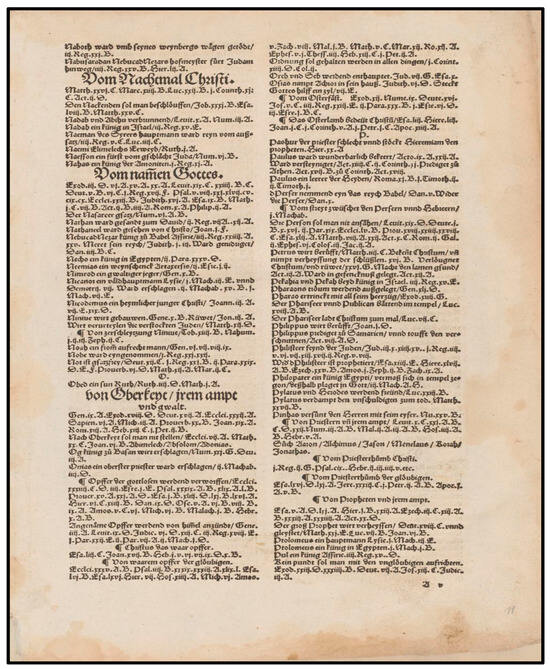

Moving forward, how were readers to make sense of this imposing mass of text and image? Now we come to the intersection of the Prophezei’s desire to shape both semantic memory and to teach new visions of what scholars would now describe as historical memory, for both types of memory played a role, working in tandem, to shape the 1531 Zurich Bible’s paratextual commonplaces. How exactly did they work together? Following Zwingli’s introductory preface, readers were presented with instructions on how to navigate the Bible using a carefully prepared index of commonplaces. Organized under topical headings, the commonplaces noted the location of passages concerning potential topics of interest as well as theological and doctrinal lessons. The commonplace tradition had been a feature of the late medieval German Bible as well. Shaped according to the concerns of late medieval piety and orthodoxy, it served to establish the narrative cohesion and concordances of the Old and New Testaments, not to mention the scriptural bases of Church-sanctioned beliefs and practices. Practically speaking, it also served as a convenient way for preachers to organize sermons and for priests to utilize biblical models in the performance of pastoral care. In 1521, however, the tradition had been radically reimagined by the Lutheran pedagogist Philip Melanchthon in his brief but highly influential loci communes, the first Protestant work of systematic theology. From then on, in the context of the broader ‘Reformation of the Bible,’ commonplaces now also taught the scriptural bases of Protestant theology and Reformed memories of the biblical past.

In the 1531 Zurich Bible, thirteen pages of commonplaces were organized according to fifty-three major topics, marked in bold, along with numerous subcategories (Figure 4).16 They ranged from where to find scriptural guidance on the imminently practical issues in early modern society, e.g., loans, theft, gossip, work, hospitality, sex, old age, the conduct of family life, etc., to scriptural reflections on the abstract, the moral, and the ethical, e.g., hardships, temptations, humility, forgiveness, and obedience, etc. While these commonplace topics were readily found in the late medieval German Bible, here they organized passages that supported Reformed Covenant theology, historical memory, and their prescriptions for an ideal relationship between the church and temporal authority.

Figure 4.

Page nine out of thirteen pages of commonplaces, featuring scriptural passages assembled to explain the reformation of the Eucharist under the topic “On the Lord’s Supper”. Christoph Froschauer. Accessed on 6 September 2023. https://www.e-rara.ch/zuz/content/zoom/1929216.

A major topic, for example, was “Political authorities, their office and powers”. Under the heading, eleven chapters from the Old Testament and six from the New were marshaled to argue for the church’s obedience to divinely ordained temporal authorities and to articulate their proper role in safeguarding the church from idolatry and heresy.17 In stark contrast, “On Priests and their Office” constituted a minor subcategory with only eight chapters, seven from the Old Testament, and only one from the New.18 It was deliberately grouped, moreover, near “The Priesthood of Christ,” (six chapters) and “The Priesthood of all Believers,” (ten chapters) in order to assert that with the ultimate sacrifice of Christ on the cross, a singular act that He performed in the function of a universal high priest before God the Father, the model of the sacerdotal (read Levitical and Catholic) priesthood had decisively given way to another Old Testament Israelite model, the Reformed pastor–prophet.19 To drive this point home, the next topic listed was “On Prophets and their Office,” with a grand total of twenty-six, mostly Old Testament, chapters.

Under “On the Life of this Age,” or rather, how the Swiss were to live out the faith in the here and now, several subtopics organized passages that were understood to champion the primacy of Christ as a teacher and intercessor, and to preclude the intercession of the saints, prayers for the dead in purgatory, and the extra-scriptural traditions of the Catholic Church: “The Teaching of Christ upsets many” (nine chapters), “Our Teacher is God the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit” (fifteen chapters), “From the Dead we can learn nothing” (three chapters), and “Against Human Teaching” (twenty-two chapters).20 Echoing the infamous ‘Sausage Rebellion’ of 1522, which had inaugurated the Reformation in Zurich, the subtopic “On the Freedom of Believers” highlighted fifteen New Testament chapters that, for the Prophezei, proved the voluntary nature of religious observances, thus obviating the mandatory feasts, vigils, and dietary prescriptions of the Catholic Church.21

In the hands of a skilled reader, these commonplaces worked to make sense of the biblical past in light of a Reformed Covenant theology that operated as a unity that bound together the Old and New Testaments across time and space. How exactly was it Reformed? Justification by faith alone and the rejection of idolatry in myriad forms formed the threads of this unity. For example, the Prophezei taught the unity of the Covenant by juxtaposing Old Testament chapters grouped under the Abrahamic “Circumcision of the Flesh” (nineteen chapters) with those concerning the “spiritual circumcision of faith” under the sign of Christian Baptism (eight chapters).22 Justification by faith alone, which Zwingli claimed to have arrived at independently of Luther sometime before 1518, formed a major thread of several commonplaces. Under “On the Merits of Mankind,” the reader was directed to passages that refuted the notion that humanity could attain justification, and therefore salvation, through the moral or ethical performance of the Law. These included the plaintive lament of King David in Psalm 142 (143): “Hear my prayer O Lord, heed my entreaty, answer me according to thy will to truth and justice. Yet, enter not into judgment of your servant, for according to your judgment there are none alive who are just,”23 not to mention Paul’s Christocentric soteriology in Galatians 2:20: “Therefore, no flesh is made holy through the works of the Law...Rather, I am dead according to and through the Law, though I am alive unto God. I am crucified with Christ, yet I live still; not to myself, but rather through Christ who lives within me. While I live in the flesh, I live also in the faith of the Son of God, who loved me, and gave himself for me”.24

In the same vein, under the bluntly didactic subtopic “Faith makes one pious and just without the aid of works,” the reader was directed to Isaiah 53:11-12, a passage traditionally interpreted to prophesize the universally redeeming effects of Christ’s sacrifice on the cross: “My righteous servant will justify many and save them through his deeds, for he will take away their sins”.25 Supporting Isaiah 53:11-12 was Saint Paul’s explanation of Abraham’s elective faith in Romans 4:1-2, a passage frequently cited by German and Swiss reformers in defense of sola fideism: “ Are we to say then that our father Abraham was made whole according to the flesh? We say this: If Abraham was made holy through works, then that is certainly an accomplishment, but not before God. Instead, what do the scriptures say: Abraham believed God, and it was accounted to him as righteousness”.26

Moving forward, these commonplaces served not only as study guides for learning Reformed Covenant theology and soteriology, but they also carried practical implications in supporting Zurich’s reformation of the liturgy and sacraments at the local and international levels. For a particularly potent example, we need to turn to the controversy that caused such staunch disagreement between the Swiss Reformers and Luther at Marburg, that is, of course, the ‘reformation’ of the Eucharist into the Lord’s Supper according to ‘sacramentarian’ or ‘memorialist’ principles. Rather than offering my own explanation of these specialized theological terms, we should read what the Zurich Bible has to say under the commonplace topic “On the Lord’s Supper”. To begin, readers were directed to Matthew 26:26-27 and Mark 14:12-26, passages that recount Christ’s final Passover Seder, in which He explained the significance of His impending death to the Apostles and gave them instructions on how to celebrate the sacred meal as a sacrament of the Church.

In the Gospel of Matthew, near Christ’s Eucharistic injunction—“Drink this, all of you, for this is my blood of the New Testament, which will be shed for the many for the forgiveness of sins”—the reader was informed via a marginal comment that “The cup is the New Testament, as in Gal. 4” (3 in modern Bibles).27 In this chapter, Paul discusses the power of the Old Testament Law to condemn Christians, and the expansion of the Abrahamic Covenant to them through faith in God’s salvific promise. Near the highlighted passages in the Gospel of Mark, two marginal comments explained the typological and symbolic relationship between the Paschal Lamb of Exodus 12, the bread broken and eaten at the Last Supper, and the ‘body of Christ’ eaten in the form of Eucharistic bread: “Christ fulfilled the Pascal Lamb on the Cross. I Cor. 5....The bread is the body of Christ and also the cup of God. Math. 26. Luc. 22. I Cor. 10”.28 So far, highlighting these relationships would have been at home in medieval Eucharistic theology, but the following four commonplace suggestions taught a decidedly Reformed take on the meaning of the sacrament.

For these, we need context; the identification of the Pascal Lamb with Christ had been given new meaning in the Eucharistic debates of the 1520s. Wrestling with traditionalist opponents, Zwingli struggled to articulate a Reformed theology of the Lord’s Supper until a scriptural solution was delivered to him in the form of a prophetic dream (Gordon 2017). In Zwingli’s dream, an admonishing apparition (considered by his opponents to be a possibly demonic omen) had revealed the ‘true’ meaning of the sacrament by guiding him to Exodus 12:11, a passage in which, to his thinking, the phrase “Das ist das Phase,” or “It is the Lord’s Passover,” had clearly been used in a symbolic sense in reference to the elements of the Passover meal. Rejecting the corporeal presence maintained by Luther, and the perpetual sacrifice of the Mass maintained by the Catholic Church, Zwingli asserted that the Passover meal and the Lord’s Supper were instead symbolically and spiritually linked through a shared historical memory of the enduring Covenant. As Bruce Gordon has explained, “That the admonisher pointed Zwingli to a passage from the Pentateuch reinforced the Covenantal nature of the sacrament. The Eucharist in Zurich found its narrative in the story of the Israelites liberation from Egypt; it is the meal of thanksgiving, and that historical memory provided the framework of the liturgy”. (Gordon 2017, p. 306)

The reader was next directed to Luke 22:19-20, which added to the previous Gospel accounts an essential passage used to radically alter the traditional theology of the sacrament; “And he took the bread, gave thanks, broke it, and gave it to them saying ‘This is my body, which will be given up for you, do this in remembrance of me”.29 What was so significant about this passage, in which Christ spoke about the role of memory in building the sacramental life of the Church? By calling attention to Christ’s command, “do this in remembrance of me,” readers were led to understand that the Lord’s Supper commemorated an event that had happened only once and was valid for all time thereafter. In other words, the sacrament was not a perpetual participation in Christ’s sacrifice effected by priests, as if once had not been sufficient for salvation, but a ‘memorial’ service meant to remind believers of their belief in the shared Covenant, and to place a faithful congregation into spiritual communion with a Christ who was not physically present in the bread and wine, but seated at the right hand of the Father in heaven. This final point was driven home, as it was by the Swiss at Marburg, by directing readers to Acts 2:34-35, in which Christ’s ascent to heaven was substantiated by recalling David’s verses in Psalm 109; “The Lord said to my Lord, sit at my right hand, until I make your enemies your footstool”.30

A decidedly Reformed, Covenantal, and ‘memorialist’ understanding of the Lord’s Supper was next illustrated by guiding readers to I Cor. 11: 20-33, in which Paul chastised the Corinthians for failing to treat the sacred meal as a solemn occasion to come together in memory of Christ’s sacrifice and promised return: “Now when you come together, do not conduct the Lord’s Supper in such a way that some have already eaten their own meals at home, and now another is hungry, and still another drunk...For as often as you eat of this bread and drink of this drink, you should proclaim the death of the Lord, until he comes”.31 In the same passages, Paul castigated those who partook of the meal without understanding its function as an inward sign of faith for the outward community. The faith of individuals and their proper discernment of the Covenantal relationship between past and present were needed to form the communal ‘body of Christ’: “Whosoever eats unworthily from this bread, or drinks from the cup of the Lord, is guilty of sinning against the body and blood of the Lord. Let everyone who eats of this bread and drinks this drink search their own conscience and remember who they are. For whosoever eats and drinks unworthily, without discerning the body of the Lord, does so unto judgment”.32

What were Zwingli and the Prophezei trying to teach through the accumulated weight of these passages? At the heart of the lesson was the poignant idea that memory, both in its individual faculty and historical emulatio and accomodatio forms, played the critical role in binding Israel and the Church together across time and space. Christ, the Pascal Lamb, had emulated and adapted the Passover of Exodus and the memorial function of the Seder in commanding His followers to remember Him as often as they came together. In the aftermath of Christ’s death and resurrection, Paul taught the Corinthians the necessity of understanding the sacrament as a solemn social sign, an outward signification of an inward faith directed towards the edification of others. In other words, according to Zwingli and the Prophezei, who shaped the 1531 Zurich Bible to teach their Reformed Covenant theology and the historical memory that undergirded it, the Lord’s Supper had always been a reminder of the expansion of the Israelite Covenant to the Church and a sacramentum in the classical sense of an oath, taken as an individual’s proof of belonging in a community bound together by memory. What am I trying to teach through the accumulated weight of this article? That the language of historical memory—both in period terms such as emulatio and accomodatio, and in our modern, social-scientific and media-driven terms—remains one of the most compelling ways of understanding the transformative historical imagination behind an early Reformed Covenant theology, its expression in early Reformed Bible culture, and its transformative social impact in the Swiss Reformation.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | This article constitutes a revised and expanded version of a conference paper delivered as part of a panel entitled “New Directions in the Swiss Reformation” at the Sixteenth Century Society and Conference, Baltimore, MD, 10/28/23. |

| 2 | While studies by Traudel Himmighöfer (1995), Wilhelm Kettler (2001), and Christoph Sigrist (2011) have provided us with authoritative accounts of the bibliographic development of the Zurich Bible as an early modern genre, as well as detailed philological and comparative treatments of the 1531 folio edition in particular, this new reading falls more in line with the work of Bruce Gordon (2014) in seeking to understand how particular editions of the Zurich Bible fostered a labile historical memory that could inform the collective identity and communal worship of the Zurich church throughout its dynamic history. |

| 3 | Other scholars have admirably provided biographies and studies of the leading members of the Zurich Prophezei. For accounts of their individual backgrounds in relation to the 1531 Zurich Bible, see Himmighöfer (1995, pp. 213–28) and Kettler (2001, pp. 99–107). |

| 4 | The authorship of the preface has been subject to some disagreement. Traudel Himmighöfer (1995) has argued that it should be attributed to Leo Jud, the Hebraist scholar who regularly preached in German and served as the ‘public face’ of the Prophezei. The consensus opinion, however, followed by Lavater (1983), Kettler (2001), Sigrist (2011), and Gordon (2021), is that the preface best accords with the rhetorical style and argumentation of Zwingli. |

| 5 | Seeking to move beyond the recent historiographical focus on Martin Luther’s hostility toward Jews near the end of his life, Kenneth Austin’s (2022, Introduction xvi, xxi, pp. 78–79) comprehensive study of the relationship between Jews, Judaism, and the Reformation has demonstrated that Judaism served as a critical category through which the new confessions fashioned their beliefs about the biblical past. Austin also claimed that the Reformed emphasis on Covenant theology rendered it the “most sympathetic” of the Protestant confessions to Judaism, even if, in practice, firm lines had to be drawn against the interpretative traditions and teachings of Rabbinic Judaism. |

| 6 | So vil vom Alten Testament/in dem sich Gott mit seyner macht/weyßeyt/ güte und gerechtigkeyt dem menschen aufthüt und zu erkennen gibt/deßhalb es von niemans verachtet werden sol als in alte gschrifft die uns nichts angange un(d) yetz verspulcht sey. Dan(n) das ist die rechte gschrifft und zeügnuß von Gott/in der der Herr Jesus die Juden weyset/unnd heyßt sy durchsüchen und erfüntelen. Welcher der gschrifft nit glaubt/der glaubt auch Christo nit/und wär sy verschupfft der hat Christum und Gott vor verschupfft. Excerpt from Hans Rudolf Lavater’s (1983) edited facsimile, Die Zürcher Bibel von 1531. Zürich: Theologischer Verlag Zürich, Preface, folio 5r. |

| 7 | Wir erlernend auch in dem büch die ewig fürsichtigkeyt und waal Gottes/in deren er etlich annimpt/als im Abel/Noe/Abrahamen/Isaac/Jaacob/Joseph/etc. Etlich verschupfft als den Cain/Ismael/Esau unnd andere. Da thüt Gott seyn barhmherzigkeyt (doch dunkel) auf/unnd zeyget an den außerwelten unnd hohen sonen/in dem er die welt widerbringen und heyl machen wolt/unnd in dem alle völker glückhafftig und sälig werden soltend/namlich im Sonen Abraham/das ist in Christo seynen geliepten sun/der nach der menschheyt ein sun Abrahe seyn solt. Deßhalb die linien der verheissung die auff den selben sonen reicht/von allen frommen von ye welten här gar fleyssig geachtet unnd wargenommen ist worden. Preface, folio 5v. |

| 8 | Da findt man mancherley beyspil der frommen und bösen künigen/wiewol der frommen der minst teyl ist/und wie aller abfal des volcks von bösen künigen unnd obren ye unnd ye enstanden ist. Dann in Jeroboam sicht man/ was schaden es bringe ein mal von Gott abgefalen sein/und das volk sünden machen wider Gott. Welcher abfall für unnd für so vil zügenommen hat/das kein warnung noch straaff hat mögen ershießen/biß sy in gefencknuß (erstlich Israel/nachmals Judah) gefürt/verderbt und in alle land zerströuwet sind. Und ob sy gleych Gott wider in ir land auß der gefencknuß fürt/kamend sy doch in so hohen unnd eerlichen staat niemer mer/als sy vormals gewesen warend...” Preface, folio 5r. |

| 9 | Nun wöllen wir hie verhalten/das in unser translation wenig der puncten acht gehebt ist/dann die selben auch neülich von den Rabinen der Juden erdacht/von anfang nit gewesen/sind. Er bekümmeret unns wenig was die Rabinen in iren commentirren shreybind/welche auch innerhalb etlich hundert jaren aufgestanden/die offt so ungerympte unnd torächte ding fabulierend/das es spöttlich ist davon zereden. Dieweyl sy dann ires eignen gsatzes so unberichtet sind (dann die blindheyt ligt inen vor den augen) unnd auch sunst aller güten künsten unwüssend und gar unverstendig/mögen sy zü erklärung und verstand der gschrifft wenig fürderlich sein. Preface, folio 4v-r. |

| 10 | Der sibenzig tolmätschen translation (die lang vor Christo gemachet ist) verachtend wir gar nit/sonder haltend sy groß/dann sy an vilen orten die ding gar eigentlich besähen habend. Doch giltet bey uns allwäg mer das Hebreisch/als der ursprung und grund/wiewol wir nit so vil auff den büchstaben/als auff der sinn und meynung achtend. Preface, folio 4r. |

| 11 | Dan(n) eigenschafft der spraach mag niemants mit nutz in ein andere spraach bringen/deßhalb es wäger ist man behalte einer yeden spraach ir eigenschafft unverseert. Preface, folio 4r. |

| 12 | Die torechte supersticion etlicher/die für ein grosse sünd habend von den silben und worten zeweychen/bedünckt unns mer ein eigenrichtiger kyb/weder ein vernünffitig ermässen und urteyl/von dem aber hie nit nach notturfft statt ist zereden. Preface, folio 4r. |

| 13 | Und ob darnäbend etlich sind die das läsen der gschrifft auff iren vorteyl/gyt/kyb und anfächtungen mißbrauchen/fleyschliche freyheyt darauß nemmend... Preface, folio 7v. |

| 14 | ...unnd ander leüt leerend/die warheyt widersächtend/das sol uns nit hinderen das wir darumb nit gute bücher truckind oder läsind/als wenig als sich der Räbmann vom weynpflanzern laßt abschrecken/ob gleych vil darnäbend täglich truncken werdend/unnd den edlen weyn mißbrauchend. Preface, folio 7v. |

| 15 | Du kumpst zü mir mit schwärt/spieß und schillt. Ich aber kumm zü dir in namen des HERREN Zeboath deß Gottes des zeügs Israels/die du verachtet hast. Hüts tags wirt dich der HERR in mein hannd überantworten...Und das alle dise gmeynd innen werde/das der HERR nit durch schwärt noch spieß hillft: dann der stryt ist deß HERREN/und wirdt euch geben inn unsere hennd. Using the Bible’s internal numbering system, this quote can be found on folio CXL. |

| 16 | The modern system of chapter and verse, popularized in the latter half of the sixteenth century through Robert Stephanus’ Latin editions, was not yet present in the 1531 folio edition of the Zurich Bible. Instead, chapter numbers were given with a Roman numeral, while a unique system of letters (A through G) guided the reader to a grouping of paragraphs. |

| 17 | von Oberkeyt/irem ampt und gwalt, Gen. ix. A. Exod. xviii. D. Deut. xvii. A. Ecclei. xxxii. A Sapien. vi. A. Mich. iii. A, Proverb. xx. B. Joan (John). xix. A. Rom. xiii. A. Heb. xiii. C. I Pet. ii. B. Nach oberkeyt sol man nit stellen/Ecclei. vii. A. Math. xx. C. Joan (John) vi. B. Abimelech/Absolom/Adonias. Folio A5r. |

| 18 | Von Priestern und irem ampt/ Levit. x. C. xxi. A. B. C. D. xxii., Num. iii. A. B. Mal. ii. A. iii. A. B. Hos. iiii A. B. Hebr. v. A. Such Aaron/Alchimus/Jason/Menelaus/Rorah/Jonathas. Folio A5r. |

| 19 | Vom Priesterthum Christi. I Reg. ii. G. Psal. cix., Hebr. ii, iii, iiii, v. etc. Vom Priesterthumb der Glöubigen. Esa. lxvi. D. lxi., Jere. xxxiii. C. I Petr. ii. A.B., Apoc. i. A.v. B. Folio A5r. |

| 20 | Vom läben dises zeyts...Unser Lerer ist Gott vatter/sun/und Heyliger geyst/Deut. xviii. Esa. xxx. D. xlii. liiii. C. Jere. xxxi. Mat. viii. ix. xvi. A. xxiii. B. Luc. xii. B. Joan (John).vi. xiiii. xv. Act.ii. I Joan. ii. D...Von Todten sollend wir nit lernen/Deut. xviii. B. I Reg. xxviii. Luc. xvi. Wider Menschen leer. Exod. xxiii. Deut. iiii. xxviii. Jos. xxiii. Esa. x. A. Jerem.xxiii. Ezechiel. xx. Matth. vii. B. xv. A. B. xvi. A. Luc. xi. xii. Ro. xvi. C. I Cor. vii. Eph. iiii. v. Phil. iii. A. Col. ii. B. I Timoth. iiii. II Tim. iiii. Tit. i. Heb. xiii. B. II Petr. i. C. Folio A5v. |

| 21 | Von Fryheit der glöubigen. Joa. viii. C. Act. x. B. Ro. viii. A. B. xiiii. A. B. I Cor. viii. A. ix. C. x. C. II Cor. iii. B. Gal. iiii. A. v. B. Col. ii. C. i. Petr. ii. B. Folio A3v. |

| 22 | Von Beschneidung des fleischs. Gen xvii. B. C. Exo. iiii. F. Jos. v. A. Jere. vi. B. ix. D. Ezech. xxxvi. lxiiii. Luc. ii. C. Joan (John). vii. B. Acto. xv. A. xvi. A. Rom. ii. C. xv. A. i. Corinth. vii. C. Ephes. ii. A. I Mach. i. E. II Mach. vi. Von geystlicher Beschneydung. Deut. x. D. xxx. B. Jerem. iiii. A. vi. B. Acto. vii. E. Rom. ii. C. Philip. iii. A. Colos. ii. B. Folio A2r. |

| 23 | Psalm 143: 1-4 in modern Bibles; Hör mein gebätt O HERR/vernim mein fleehen/antwort mir umd deiner warheit und gerechtigkeit willen. Doch gang nit zü gericht mit deinē knecht/dann vor deinem gericht ist nieman gerecht der da lebt. Using the internal system in Psalms, folio 52/LIII. |

| 24 | Darumb wird durch die werck des gsatzes keyn fleysch from(m) gemachet...Ich bin aber durch gsatz dem gsatz gestorben/uff das ich Gott läbe. Ich bin mit Christo gecreütziget/ich läben aber: doch yetz nit ich/sonder Christus läbt in mir. Dann was ich läb im fleisch/das läb ich in dem glaubē des suns Gottes/der mich geliebet hatt/und sich für mich dar gegeben. Using the internal system in Galatians, folio CCLXXXVr. |

| 25 | Mein gerechter knecht wirt seiner kunst die menge gerecht machen und erlösen/dan er wirt ir sünd hin tragen. Using the internal system in Isaiah, folio XCVIv. |

| 26 | Was sagend wir dan von unserem vatter Abraham das gesunden habe nach dem fleysch? Das sagend wir: Ist Abraham durch die wercke from(m) gemacht/so hat er wol rhüm/aber nit bey Gott. Was sagt aber die geschrifft: Abraham hat Gott glaubt/und das ist im (ihm) zur gerechtigkeyt. Using the internal system in Romans, folio CCLXVIIIv. |

| 27 | Trinkend alle darauß/das ist mein blüt des neüwen Testaments/welches vergossen wirdt für die menge zur v(er)gebung der sünden...Der kelch ist das nüw testament/wie Sara Gal. 4. Using the internal system in Matthew, folio CCVIr. |

| 28 | Das Osterslamb hatt Christus am crütz leyplich erfüllt. I Cor. 5...D(a)s brot ist d(er) leyb Christi und ist die Kilchen Gottes auch. Math. 26. Luc. 22. I Cor. 10. Using the internal system in Mark, folio CCXVII versio and recto. |

| 29 | Und er nam das brot/dancket/und brachs und gab es inen/und sprach: Das ist mein leib/der für euch ggeben wirt/das thün zü meiner gedächtnuß. Using the internal system in Luke, folio CCXXXIIIr. |

| 30 | Derr Herr hat gsagt zü minem Herren: Setz dich zü meiner rechten/bis d(ass) ich deine feynd leg zü schämel deiner füssen. Using the internal system in Psalms, folio XLVIv. |

| 31 | Wenn ir nun züsammen kommend mit einander/so halt man da nit des Herrenn Abentmal/dann ein yetlicher nimpt vorhin sein eigen Abentmal under dem essem. Und einer ist hungerig/der and(er) ist truncken...Dann so offt ir von disem brot essend/un(d) von disem tranck trinckend/sollend ir des Herren tod verkünden/bis das er kumpt. Using the internal system in Corinthians, folio CCLXXVIIIv. |

| 32 | Der mensch aber ersuche und erinere sich selber/unnd also esse er von disem brot/un(d) trincke von disem tranck. Dan(n) welcher unwirdig isset/und trinckt/der isset un(d) trinckt im selber das gericht/in dem/ das er nit undscheydet den leyb des Herren. Ibid. |

References

- Assmann, Aleida. 2011. Cultural Memory and Western Civilization: Functions, Media, Archives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, Kenneth. 2022. The Jews and the Reformation. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch, David. 2007. Aristotle on Memory and Recollection: Text, Translation, Interpretation, and Reception in Western Scholasticism. Boston and Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Christ-von Wedel, Christine, and Urs B. Leu, eds. 2007. Erasmus in Zurich: Eine verschwiegene Autorität. Zurich: Verlag Neue Zürcher Zeitung. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Jeremy. 1999. Living Letters of the Law: Ideas of the Jew in Medieval Christianity. Berkeley, Los Angeles and Paris: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]