1. Introduction: Memory and Contemporary Readings of the Eternal City

Rome, historically regarded as a monumental center of Catholic Christendom, now stands as a layered urban environment shaped by diverse religious communities whose coexisting traditions broaden and complicate the city’s cultural memory. While Catholic heritage remains prominent through basilicas, baroque churches, and ecclesiastical institutions, minority groups—Jewish, Muslim, Eastern Orthodox, Protestant, Methodist, Buddhist, Bahá’í, and Scientology, among others—have contributed distinct architectures, rites, and narratives. Over centuries or mere decades, these communities have inscribed tangible and intangible traces onto Rome’s topography, transforming it into a palimpsest of overlapping

lieux de mémoire (

Nora 1992). By deploying architectural idioms, iconographic motifs, ritual practices, and communal narratives, they challenge monolithic perceptions of religious uniformity and reshape the city’s memoryscape. Building on spatial and material approaches to religion (

Knott 2005;

Becci et al. 2013,

2017;

Giorda and Omenetto 2025), cultural memory studies (

Assmann 2011;

Assmann and Czaplicka 1995;

Houdek and Phillips 2017), and Warburg’s Mnemosyne methodology (

Warburg 1924–1929;

Gombrich 1986;

Michaud 2004), this article argues that minority religious communities function as active ‘memory agents’. Through architectural forms, iconographies, ritual actions, and other symbolic strategies, they adapt, transfer, and reconfigure cultural memories in contemporary Rome, resulting in a contested and ever-evolving memoryscape that redefines what counts as religious and cultural heritage in a pluralistic context. Contrary to earlier assumptions that secularization would diminish religion in public life, recent scholarship on urban religion suggests that new religious forms, heightened religious super-diversity, and ongoing negotiations over religious visibility and space have emerged instead (

Casanova 1994;

Knott 2005;

Burchardt and Westendorp 2022). Religious buildings and other venues—ranging from monumental synagogues and mosques to understated chapels, repurposed structures, community centers, and gardens for ritual gatherings—serve as points of reference for tangible and intangible heritages. UNESCO and related organizations emphasize that heritage encompasses not only monumental sites and fine art but also rituals, oral traditions, and performative acts that carry communal values and collective memory across generations. In Rome, centuries of Jewish life persist through the Great Synagogue and the surrounding quarter, where kosher eateries and Hebrew inscriptions illustrate the interplay of continuity and adaptation. The inauguration of the Mosque of Rome in 1995 similarly embeds modern religious pluralism in the city’s built environment, inviting multiethnic Muslim communities into a shared urban realm (

Giorda 2024). Likewise, the Hua Yi Si Buddhist temple, founded by the Chinese community, merges Chinese architectural forms with influences from the Indian Buddhist stupa, demonstrating how Rome’s religious landscape continuously evolves through global cultural exchanges. Furthermore, these religious sites serve not only as places of worship but also as

symbolic embassies, asserting a presence in the spiritual and cultural epicenter of Catholic Christendom. Much like how nations vie for embassies in Washington to secure diplomatic visibility, religious communities strive to establish their identity in Rome, leveraging the city’s global significance to amplify their spiritual and cultural narratives. Building on prior studies, such as those presented in

New Diversities (

Vereni and Fabretti 2016), this analysis advances the discussion by integrating Warburg’s

Mnemosyne methodology to uncover how minority religious communities in Rome function as active agents in reshaping the city’s cultural memory. Unlike approaches that focus predominantly on spatial distributions or socio-cultural dynamics, this study emphasizes the interplay of symbolic strategies, architectural forms, and intangible practices—such as rituals, chants, and oral traditions—as mechanisms for adapting and transferring memory. By deploying this multidimensional framework, the analysis reveals how these communities inscribe both tangible and ephemeral traces onto the urban fabric, challenging monolithic narratives of religious uniformity and contributing to an ever-evolving pluralistic memoryscape in the Eternal City.

Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas serves as a foundational lens in this analysis, offering a nuanced framework to examine how symbols, forms, and gestures from different religious traditions migrate, transform, and reconfigure within Rome’s urban memoryscape. Warburg’s concept of “Pathosformeln”, or emotional formulas, is particularly instructive, as it allows for the tracing of recurring motifs and symbolic energies that traverse temporal and spatial boundaries. This methodological approach underscores the dynamic interplay between tangible and intangible cultural memories, where architecture, iconography, and ritual practices are reactivated and re-contextualized to meet contemporary needs. Warburg’s Mnemosyne is not merely a catalog of static images but a tool to uncover the afterlives (Nachleben) of cultural forms as they adapt to new socio-historical milieus. By mapping the visual and performative vocabularies of minority religious communities in Rome—from the Neo-Assyrian motifs of the Great Synagogue to the Ottoman-inspired domes of the Mosque of Rome—this study demonstrates how these groups act as active memory agents, reinterpreting and integrating their cultural heritage into the city’s broader memoryscape. Such an approach elucidates the tension between continuity and innovation, revealing how religious minorities negotiate their visibility and identity within a historically Catholic-dominated context. Furthermore, the Mnemosyne lens enables the analysis of intangible heritage, such as the embodied practices of chanting, prayer, and communal celebrations, as kinetic Pathosformeln that preserve and transmit collective memory. This perspective is particularly valuable in understanding how ephemeral acts, like Quranic recitations or Jewish liturgical chants, imbue physical spaces with layered mnemonic significance. In this way, Warburg’s methodology provides a comprehensive framework for examining how Rome’s religious plurality contributes to an evolving urban identity, where new constellations of memory continuously reshape the Eternal City’s cultural and spiritual landscape.

In analyzing Rome’s complex religious landscape, the concept of a religioscape proves invaluable for capturing the dynamic interplay between sacred architecture, ritual practices, and the lived experiences of diverse faith communities.

Trantas (

2019) argues that religioscapes are not merely static structures but serve as active memory agents through which migrant communities inscribe and negotiate their cultural identities and narratives of de- and reterritorialization.

Hayden and Walker (

2013) extend this idea by illustrating how intersecting religioscapes create nodes of collective memory that both preserve traditional values and accommodate innovative adaptations, thereby reflecting the multifaceted nature of contemporary urban identity.

McAlister (

2005) further emphasizes that these spatial expressions are deeply intertwined with broader global processes, where the materiality of sacred spaces merges with intangible cultural practices to form new symbolic geographies. Together, these theoretical perspectives suggest that Rome’s religious plurality, where established traditions coexist with emerging minority expressions, operates as a dynamic memoryscape that continuously reshapes the city’s heritage, making further exploration of the religioscape concept essential for understanding how urban religious diversity contributes to collective identity and cultural renewal.

2. Rome: Spatial Distribution of Non-Catholic Places of Worship

The following analysis examines an informal dataset cataloging religious communities across Rome; this is the work of Luciano del Monte for his master’s thesis in History of Religions at the Università degli Studi di Roma Tre (2021–2023) (please refer to the HTML file for a visual MAP). This dataset, while incomplete, reflects the absence of a formal registry documenting the breadth and diversity of religious minorities in the city. The lack of such official records highlights the importance of this type of analysis, which seeks to shed light on the religious plurality that shapes Rome’s contemporary identity. As a city historically dominated by Catholicism, Rome is increasingly home to a variety of religious traditions. Exploring the spatial distribution, size, and cultural significance of these communities provides valuable insights into the dynamics of coexistence and the socio-cultural evolution of the city. This analysis underscores the importance of understanding Rome not only as a historic hub of Catholicism but also as a growing multi-faith metropolis. The religious geography of Rome reveals a striking plurality, shaped by centuries of migration, urban evolution, and intercultural dialogue. The dataset reflects the dominance of Catholicism, with over 300 active Catholic churches, ranging from monumental basilicas like St. Peter’s to smaller parish churches scattered throughout the city. This overwhelming presence emphasizes Rome’s identity as the epicenter of Catholic Christendom and its influence on the city’s architectural and cultural heritage.

In parallel, the dataset highlights a notable presence of Eastern Orthodox communities, with approximately 30 sites. These include Romanian, Greek, and Russian Orthodox churches that blend traditional Byzantine architectural styles with adaptive reuse of secular or Catholic structures. Such transformations embody both cultural resilience and the strategic integration of these communities into Rome’s urban fabric. Protestant denominations, including Methodist, Baptist, Anglican, and Valdese groups, collectively account for around 40 places of worship. Iconic examples like the Tempio Valdese in Piazza Cavour and the Methodist church on Via XX Settembre reflect diverse European influences, with architectural styles ranging from Gothic Revival to 19th-century eclecticism. These sites often serve dual roles as places of worship and centers for cultural and educational outreach, underscoring their role in shaping alternative narratives within Rome’s religious tapestry. The Jewish community, one of the oldest in Europe, maintains eight synagogues, including the monumental Tempio Maggiore in the Jewish Ghetto. These sites are vital for both religious observance and the preservation of Jewish cultural heritage, which are often intertwined with Rome’s broader historical memory. Meanwhile, Islamic centers, including the Grande Moschea, and smaller prayer spaces, such as El Fath in Magliana, number approximately 12. These spaces demonstrate both the demographic growth of the Muslim community and its efforts to establish architectural landmarks within Rome’s religious topography. Smaller but significant representations include Buddhist and Hindu communities, with five and four sites, respectively. These places of worship often serve dual roles as cultural hubs, catering primarily to diasporic communities from South and Southeast Asia. Similarly, Jehovah’s Witnesses operate nine Kingdom Halls, reflecting their organizational network and consistent presence in the city. Additional minority groups, including Scientologists, have carved out three dedicated sites, while emerging or less represented faiths, such as Sikhism and Bahá’í, maintain smaller, more peripheral spaces. The overall distribution of these communities highlights the layered complexity of Rome’s religious landscape. While Catholicism remains the cornerstone of its spiritual and architectural identity, the growing visibility and influence of minority religious groups illustrate the city’s evolution into a pluralistic urban environment. These sites collectively contribute to a dynamic interplay of memory, heritage, and identity, reshaping Rome’s religious narrative into one of coexistence and shared cultural expression.

The spatial distribution of religious communities in Rome reflects the interplay of historical privilege, migration patterns, and socio-economic dynamics, illustrating how diverse faiths shape and are shaped by the city’s urban landscape. Catholic churches dominate the cityscape, with a dense concentration in the historic center (Municipi I and II), underscoring Rome’s identity as the seat of the papacy and its enduring influence over urban planning. In contrast, Orthodox Christian communities, numbering approximately 30, are primarily located in peripheral areas like Lunghezza and Borghesiana, reflecting settlement trends among Eastern European migrants. Protestant and Methodist churches, such as the Tempio Valdese on Piazza Cavour and the Methodist church on Via XX Settembre, occupy historically modernized zones, signaling their integration during Italy’s post-unification era. The Jewish community remains anchored in the historic ghetto (Municipio I), a site of resilience and cultural memory. Islamic centers, including the Grande Moschea, are situated in suburban areas like Parioli Acqua Acetosa, symbolizing the growing presence of Muslim communities in Rome, with smaller prayer rooms dispersed in working-class neighborhoods like Torpignattara and Marconi. Buddhist and Hindu centers, often in less central Municipi VIII and XI, adapt converted industrial or residential spaces, reflecting pragmatic approaches by Asian migrant populations. Emerging faiths, such as Jehovah’s Witnesses and Scientology, use multi-purpose spaces in suburban zones, reflecting their more recent establishment. This mosaic of spatial distribution highlights the dual dynamics of centrality and peripherality, with dominant traditions entrenched in prime locations and minority faiths adapting to more marginal spaces, showcasing how Rome’s urban fabric accommodates a vibrant and evolving religious pluralism.

3. The Religious Embassies in Rome and Their Satellite Consulates

The complexity of cultural memory in cities like Rome arises from the interplay between official historical narratives—often institutionalized through museums, state-sanctioned commemorations, and the monumental core’s Catholic and imperial symbols—and the other memories generated by religious minorities historically marginalized or rendered invisible (

Assmann 2011;

Nora 1992). In this context, the Jewish community of Rome, which endured centuries of ghettoization and exclusion under papal authority, emerged into a new phase of civic life after emancipation. One of the most visible symbols of this newfound status is the grand Tempio Maggiore di Roma (the Great Synagogue), built between 1901 and 1904 on the banks of the Tiber River in what had been the Roman Ghetto (

Figure 1). Designed by Vincenzo Costa and Osvaldo Armanni, the synagogue’s architecture fuses Neo-Assyrian motifs with elements of Italian Art Nouveau (Stile Liberty), underscoring a strategic engagement with ancient lineage to assert a history that precedes Rome’s Christian hegemony (

Antinori 2011). The synagogue’s striking squared dome—unlike any other in the city—further signals the community’s distinct identity. Such stylistic amalgams are not merely aesthetic flourishes: applying Warburg’s Mnemosyne lens reveals that these designs operate as mnemonic devices, or “Pathosformeln”, drawn from a deep reservoir of Jewish cultural memory and then redeployed in a modern context to forge a powerful statement of belonging. Beyond its exterior, the interior spaces of the Tempio Maggiore enrich this layered memory. The sanctuary features richly decorated walls, ceilings with geometric and floral motifs, and Hebrew inscriptions that emphasize a continuous thread of sacred history. Adjacent to the main worship hall, the Jewish Museum of Rome displays ritual objects such as Torah scrolls, ornate covers, and silver ceremonial implements—all of which further anchor the Jewish past in a public and civic setting. By showcasing these artifacts side by side with local Roman references, the museum helps to integrate Jewish heritage into Rome’s broader historical mosaic. Moreover, intangible practices—Torah readings, Hebrew chants, and oral histories passed down through generations—activate the synagogue as a dynamic node of cultural memory. These practices transform the building from a static monument into a living testament to a community’s resilience, linking ancient genealogies to contemporary and historical Roman citizenship and public presence. Periodic events, educational programs, and interfaith dialogues held at the Tempio Maggiore also reflect the Jewish community’s ongoing efforts to position itself not on the margins, but at the heart of Rome’s multicultural landscape. In this way, the Great Synagogue counters dominant narratives that have historically defined the city’s identity around Catholic and imperial heritage alone. It stands as a testament to Jewish emancipation and a claim to visibility in the Eternal City—an architectural, historical, and ritual site where collective memory is articulated, updated, and woven into Rome’s civic fabric. Through the interplay of ancient Mesopotamian references, Liberty-style ornamentation, and communal religious practice, the Tempio Maggiore epitomizes the city’s complex palimpsest of competing and interlaced memories, ensuring that the Jewish experience remains a vital—and visible—part of Rome’s unfolding story.

A similar interplay of memory transfer and re-contextualization emerges with the Mosque of Rome (

Figure 2). The Great Mosque of Rome, opened in 1995, exemplifies a postmodern “transnational mosque” that merges diverse stylistic inspirations into one coherent statement of Islamic presence and interfaith dialogue in the Eternal City (

Giorda 2024;

D’Alessandro and Federici 2024). Conceived by Paolo Portoghesi, Vittorio Gigliotti, and Sami Mousawi, its design integrates Ottoman, Byzantine, and contemporary Italian motifs, symbolically weaving together multiple architectural and cultural heritages (

Antinori 2011). The domed central hall, recalling Hagia Sophia and subsequent Ottoman mosques, resonates with archetypal forms from antiquity which survive and morph across civilizations (

Warburg 1924–1929;

Gombrich 1986). At the same time, the mosque’s exterior colonnades, crafted to evoke stylized palm trees, embody a naturalistic tradition prevalent in Islamic art and architecture, while also recalling Italian baroque strategies that harmonize structure with decorative flourishes (

Giorda 2024). Situated in Rome’s northern quadrant, the mosque employs materials such as travertine and

sanpietrini, embedding itself within the city’s centuries-old construction vocabulary. Inside, geometric patterns, Arabic calligraphy, and minbar niches supplied by Egyptian artisans underscore a transnational collaboration that mirrors the global character of Rome’s contemporary Muslim community (

Becci et al. 2013;

Giorda 2024). This collaboration extends to Moroccan artisans who contributed brass chandeliers and intricately inlaid mosaics, further enhancing the sense of a “shared religious place” shaped by multiple traditions (

Giorda 2024;

Burchardt and Westendorp 2022). From a ritual standpoint, Friday sermons, Quranic readings, and Ramadan iftars continuously reaffirm the Great Mosque’s intangible cultural memory, linking the local congregation to the global ummah while fostering dialogue with Rome’s richly layered religious milieu (

Knott 2005;

Casanova 1994). Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne approach helps us understand how the mosque’s motifs migrate across time and space, retaining core symbolic energies yet adapting to local conditions (

D’Alessandro and Federici 2024;

Warburg 1924–1929;

Michaud 2004). The circular fountains, axial water channels, and references to Michelangelo’s Capitolium design reflect the architects’ ambition to embed new Islamic expressions within the existing Roman topography, creating a “system of places” that invites broader interfaith encounters.

Viewed through this Warburgian lens, the Great Mosque of Rome operates as a dynamic node of cultural memory, demonstrating that local religious plurality is neither static nor marginal. Rather, it is an active force, continuously reconfiguring the city’s heritage to accommodate evolving practices, identities, and dialogues that ultimately reshape Rome’s own reputation as a vibrant crossroads of diverse spiritual legacies (

Nora 1992;

Assmann 2011). While the “El Fath” prayer room on Via della Magliana might share the same fundamental purpose as grander mosque complexes—providing a place of worship for the local Muslim community—it is completely different in scale, origin, and architectural approach. Rather than being planned and built as a mosque from the ground up, “El Fath” reuses and repurposes a modest existing urban structure. Its adaptations focus on basic practicalities, such as orienting the interior space toward Mecca and creating a quiet area for prayer, rather than on elaborate decorative or monumental design. Consequently, the result is far more understated than traditional mosques: the structure often lacks prominent external features like domes or minarets, and its interior design is simplified to meet essential needs. This emphasis on functional repurposing showcases a distinctly local process of making sacred space within the constraints of an already-built environment, highlighting the unique ways smaller communities integrate religious practices into city life. By carving out prayer halls within a neighborhood once less visibly associated with Islam, “El Fath” not only meets the community’s religious obligations but also infuses the locale with motifs that reference a broader Islamic artistic heritage, thus contributing to Rome’s evolving urban fabric. A similar, if more understated, phenomenon occurs at the prayer room in Torpignattara, another multicultural district where an unobtrusive façade conceals a meticulously oriented interior. Though lacking the monumental scale of the Great Mosque, it appropriates secular or underused spaces to create microcosms of Islamic identity. Here, small-scale décor—such as Qur’anic inscriptions, patterned rugs, and intricately carved wooden screens—anchors a congregation drawn from diverse national origins, thereby converting the site into what cultural memory studies would call an “active memory agent”. Like “El Fath”, this center operates at a local level, organizing language courses, holiday festivities, and interfaith encounters that deepen the community’s imprint on the neighborhood. These three sites illustrate how architectural gestures—and the artistic expressions within them—allow minority religious communities to adapt to the Roman landscape without erasing the city’s Catholic heritage. Rather than existing outside Rome’s memoryscape, they reshape and expand it by layering new religious forms onto centuries-old architectural idioms. In so doing, they underscore Rome’s status as a dynamic mosaic, where the interplay between ritual, design, and historical references builds a plural, constantly evolving urban identity. As these mosques incorporate Ottoman, Byzantine, Moroccan, Egyptian, and Italian elements, they embody how art and architecture serve as conduits for remembering and reimagining Islam’s place within the Eternal City, thus challenging inherited narratives of uniform Catholic supremacy and revealing a more polyphonic memoryscape that continues to unfold in the heart of Western Christendom.

Eastern Orthodox communities have become an increasingly visible aspect of Rome’s contemporary religious tapestry, reflecting both historical continuities and the reshaping of urban environments under migration and globalization pressures (

Burchardt and Giorda 2021;

Giorda 2024).

Alongside long-established congregations such as the Greek Orthodox at San Teodoro and the Russian Orthodox at Santa Caterina Martire (

Figure 3), the Romanian Orthodox presence—now Italy’s largest Orthodox minority—epitomizes this trend (

Guglielmi 2022). Despite varying degrees of legal recognition and financial stability, these parishes frequently repurpose secular or Catholic-associated structures, transforming disused warehouses or former oratories into active houses of worship (

Cozma and Giorda 2022). Externally, the buildings may retain inconspicuous façades, partially masking their liturgical role to sidestep bureaucratic hurdles or local opposition (

Bossi 2018). Internally, however, they embrace distinctive Eastern Christian aesthetics—iconostases, richly hued frescoes, and the mesmerizing cadences of liturgical chanting (

Knott 2010). This interplay between “camouflage” and robust communal life highlights both the resilience and ingenuity of these Orthodox believers, many of whom navigate economic constraints while simultaneously seeking to preserve their cultural roots. In such contexts, faithful participants carry out rites that scholars often conceptualize as a rhetoric of gesture and reenactment, emblematic or emotionally charged forms traversing historical and geographical boundaries (

Morgan 2021). Indeed, the process of adapting industrial or underused urban spaces underscores a creative synthesis of old and new: although the outward appearance may be subdued, the interior fosters a vibrant sense of communal identity, complete with icons, incense, and choral antiphons that link today’s congregants to Byzantine or Slavic Christian traditions. Notably, the presence of these Eastern Orthodox enclaves complicates Rome’s traditionally Latin, papal image, forging alternative narratives of Christian belonging within the city (

Della Dora 2018). As they settle in neighborhoods ranging from the bustling center to the industrial suburbs, they contribute to local economies through small businesses and social programs. Many parishes, for instance, offer Italian-language classes to help new arrivals integrate, while also organizing intercultural gatherings and festive religious celebrations that draw in curious Roman residents. On major feast days—such as Easter or the Nativity—these churches become lively focal points where clergy, lay members, and visitors converge around richly symbolic rituals. Such grassroots engagements illustrate the communities’ growing public profile, even if their worship spaces often remain discreet. In some cases, parishes must negotiate periodic uncertainty about their leases or confront zoning regulations that fail to accommodate the layered realities of diaspora religious life (

Cozma et al. 2023). Nonetheless, through charitable outreach and ongoing dialogue with local institutions, Orthodox congregations frequently become catalysts for intercultural exchange. While some maintain deliberate low visibility to avoid friction, others embrace transparency by hosting open-door events or partnering with Catholic parishes for joint initiatives. Ultimately, these multifaceted strategies underscore the enduring diversity of Rome’s spiritual landscape. Far from peripheral, Eastern Orthodox communities have carved out places of worship that blend everyday survival tactics with liturgical grandeur, revitalizing urban niches that once lay dormant. By doing so, they not only expand the capital’s religious geography but also illuminate how faith, memory, and spatial adaptation intersect to form new expressions of Eastern Christianity in the heart of the Eternal City. Viewed through a Warburghian lens, in which images and ritual forms serve as living vessels of memory migrating across epochs and regions, the Eastern Orthodox parishes in Rome demonstrate a dynamic “afterlife” (Nachleben) of sacred motifs that transcends rigid boundaries of time and space. Their icons, frescoes, and elaborate liturgical practices not only uphold ancestral heritage but also channel an ongoing process of renewal within the city’s repurposed warehouses and former oratories. By transplanting Byzantine and Slavic visual culture into these urban niches, these communities enact a creative survival strategy—simultaneously conserving and transforming their traditions—thereby cultivating a form of “non-resilient heritage.” The subtle exteriors, housing a riot of color and ritual sound inside, highlight how these churches weave ancestral memories into contemporary settings. In doing so, they infuse Rome’s spiritual tapestry with vibrant threads of Orthodox expression, illustrating the power of faith-based images to adapt and flourish amid the evolving currents of migration and globalization.

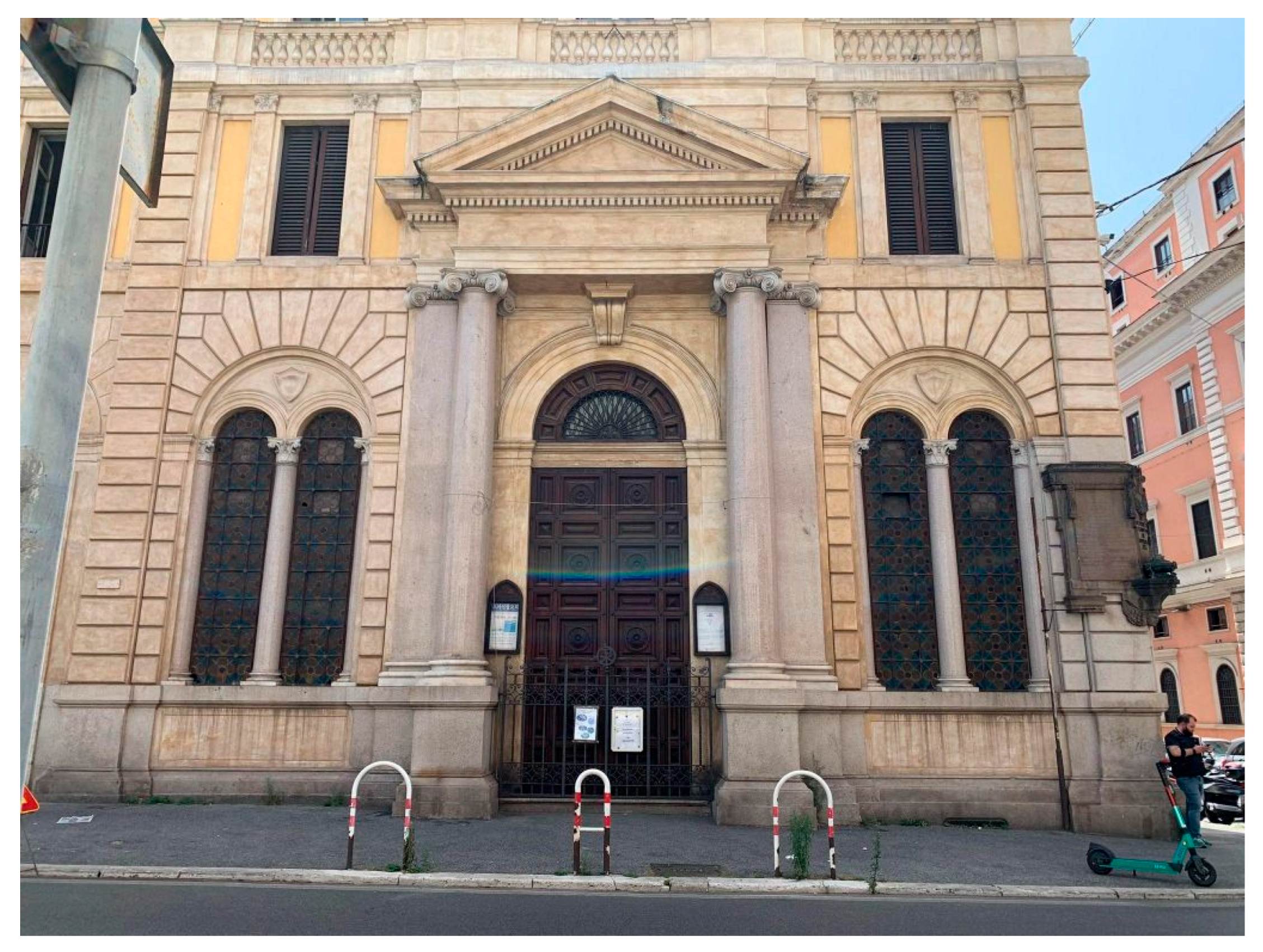

Following Rome’s unification with the Kingdom of Italy, the Methodist and Waldensian communities seized new opportunities to establish places of worship that would reflect their respective theological identities, while also engaging with the city’s evolving architectural and urban heritage. In the Castro Pretorio district, the Methodist church on Via XX Settembre commissioned by Reverend William Burt in 1891 and designed by Rodolfo Buti and Carlo Busiri Vici (

Giorda and Omenetto 2025) pushes forward a different hypothesis regarding the architectural authorship of the church) stands on the site where older sacred buildings, including the Church of San Caio and two Carmelite monasteries, were demolished as part of the 1881 master plan (

Figure 4). Completed in 1895, the exterior adopts a sixteenth-century style characterized by rusticated stonework and tall lesenes that traverse multiple floors, while the entrance portal on Via XX Settembre is surmounted by a pediment borne by columns. Inside, the rectangular sanctuary features a horseshoe matroneum, Corinthian-style pilaster strips on a high base, and bifora windows with round arches, articulating a measured classicism unusual in a city dominated by baroque or neo-Renaissance motifs. Significant decorative interventions occurred in 1924 when Paolo Paschetto was commissioned to design both the mural ornaments and stained-glass windows, infusing the interior with symbolic references familiar to early Christian iconography—such as the dove, the lamb, or the peacock—thus positioning this Methodist space in continuity with Rome’s broader religious memoryscape while maintaining its own confessional markers. The organ, built by Carlo Vegezzi-Bossi in 1895, and the 1930 pulpit underscore the community’s longstanding investment in liturgical and musical elements that emphasize preaching and congregational participation. A similar dynamic can be observed in the Waldensian tradition, which also established churches in areas such as Via XX Settembre, Castro Pretorio, and Piazza Cavour, employing architectural solutions that balanced modern functional requirements with an aesthetic language reminiscent of Reformation-era sobriety and scriptural focus. The Waldensian temple in Piazza Cavour, for instance, pairs simpler ornamental strategies with localized construction materials, creating a dialogue between the transalpine Protestant ethos and Rome’s historic built environment. Both Methodist and Waldensian edifices, by drawing on classical, Renaissance, or even neo-medieval stylistic inflections, claim a place in the city’s palimpsest of religious sites, forging spaces that honor their theological foundations while simultaneously assimilating aspects of local architectural traditions such as travertine cladding, rustication, or bifora apertures. In Warburgian terms, these structures deploy “migratory” forms—like the Corinthian lesenes or the symbolic stained-glass motifs—to produce new layers of cultural memory that challenge the once-exclusive predominance of Catholic iconography. Their distinctive stained glass, pulpits, and organ galleries simultaneously embed a Protestant narrative within Rome’s monumental fabric and reconfigure the surrounding neighborhood’s identity, projecting a sense of super-diversity that reshapes the city’s religious heritage. By situating themselves in historically significant, often radically restructured areas—like the former site of San Caio or the redesigned Piazza Cavour—these churches serve not only as worship venues but also as agents of memory transfer, affirming that the Reformation legacy has become part of Rome’s enduring architectural mosaic and underscoring how minority faiths, through adaptive reuse and stylistic innovation, actively re-inscribe their presence into the Eternal City’s ever-evolving spiritual and cultural landscape.

While the concepts of migration and stylistic blending in religious architecture may appear commonplace, the presence of minority religious sites in Rome invites deeper reflection on questions of intentionality and representation. These spaces often carry symbolic weight, as their visibility within the city subtly challenges the historical dominance of Catholicism and expands the city’s identity as a multi-faith metropolis. Their architectural designs, spatial choices, and public roles often reflect a conscious effort to assert cultural identity and offer an alternative perspective within Rome’s predominantly Catholic heritage. In this sense, these sites function not only as places of worship but also as cultural landmarks that embody the values, histories, and aspirations of their communities. They also act as symbolic embassies, establishing their communities’ presence in the spiritual and cultural epicenter of Catholic Christendom. Much like diplomatic embassies and their consulates in global capitals, these religious spaces project the identity, dignity, and heritage of their communities onto a prominent international stage. By embedding themselves within the fabric of a city steeped in Catholic tradition, these religious spaces contribute to a broader dialogue about inclusion, diversity, and shared cultural memory. They symbolize both the resilience of minority communities and their active participation in shaping Rome’s evolving spiritual and historical identity, reaffirming the city’s status as a dynamic and pluralistic urban environment.

Beyond these historically established minority traditions, Rome’s religious diversity also includes newer movements such as Scientology (

Figure 5) and contemporary sites like the Tempio di Roma Italia, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints temple in Rome. These examples highlight distinct approaches to religious presence and memory-making in the modern urban landscape. The Tempio di Roma Italia, inaugurated in 2019, reflects the global expansion of Mormonism and its integration into the local context (

Figure 6). Architecturally, it combines modern design elements with classical inspirations, featuring white granite façades and a domed roof reminiscent of Renaissance forms, symbolizing harmony between modernity and tradition. The temple is accompanied by landscaped gardens and visitor centers, creating an environment of serenity and reflection that aligns with the Latter-day Saints’ emphasis on sacred space as a site for personal and communal spiritual growth. While new, the temple embeds itself into Rome’s religious tapestry by merging contemporary architectural principles with the symbolic language of its faith, contributing to a pluralistic religious heritage. Scientology, by contrast, challenges conventional categories of religious heritage through its secularized and modernized aesthetics. Lacking ancient iconographies or ancestral rituals, it transforms urban spaces—such as offices, former cinemas, or rented halls—into spiritual training centers that reflect its organizational and therapeutic ethos. These spaces create subtle mnemonic interventions within the city, fostering memory and identity for adherents without traditional religious visuals. Anchored by the figure of L. Ron Hubbard, Scientology’s teachings, and its global movement’s narratives, these understated sites add another layer to Rome’s multifaceted religious identity. From a Mnemosyne perspective, both the Tempio di Roma Italia and Scientology illustrate how memory carriers in the urban religious landscape extend beyond universally recognized symbols. While the former aligns more closely with traditional religious aesthetics, the latter generates its mnemonic codes and performative patterns, forging continuity between global ideological lineages and the local cityscape. Together, these examples reflect the evolving dynamics of religious heritage in Rome, where established traditions coexist with emerging and innovative expressions of faith.

Rome’s diverse religious landscape is further enriched by several lesser-known Buddhist, Hindu, and Sikh temples, though some have ceased to exist or face challenges in maintaining their presence. Among the notable Buddhist sites are the Hua Yi Si temple and the Putuoshan Temple in Esquilino. The Hua Yi Si temple, whose name combines “Hua” (China), “Yi” (Italy), and “Si” (temple), was established through the efforts of the local Chinese community and donations from China and Taiwan. Its architecture reflects the traditional Chinese pagoda style, which, while iconic today, was influenced by the Indian Buddhist stupa—a structure originally designed to house sacred relics of the Buddha. In keeping with tradition, the temple features a lion statue in the courtyard, symbolizing protection and strength, and a statue of the Laughing Buddha, Bodhisattva Maitreya, within its halls. The Putuoshan Temple, or “Small Temple”, founded by immigrants from Putuo Island, continues the architectural traditions of Chinese Buddhism, though its smaller scale emphasizes its intimate, community-focused nature. Hindu and Sikh temples, though fewer in number and often situated in Rome’s suburban peripheries, serve as both religious and cultural anchors for their communities. The Om Hindu Mandir in Torpignattara features a simple yet functional design that reflects its role as a prayer hall (Mandir) while emphasizing the spiritual connection symbolized by “Om”, the sound of the universe. Similarly, the Sikh temple in Anagnina balances modest architecture with functional community spaces for worship and gatherings. However, the transient nature of some of these places of worship—whether due to relocation, financial struggles, or lack of formal recognition—underscores the challenges faced by minority religious communities in maintaining their sacred spaces. Many of these temples, particularly smaller or informal ones, have disappeared over the years, leaving behind only traces of their architectural and cultural significance. This impermanence contrasts with the enduring visibility of larger religious structures in Rome, highlighting the precarious status of minority religious heritage in an ever-changing urban landscape.

4. Conclusions

All these religious minorities engage in intangible heritage to sustain memory in ways that transcend architecture and art. Cultural memory studies underscore that traditions are not solely preserved in static monuments but are dynamically enacted through performances, ceremonies, oral histories, and repeated ritual practices that enable communities to reaffirm their identity and origins (

Assmann 2011;

Houdek and Phillips 2017). Examples such as Jewish chanting, Quranic recitation, Byzantine choral hymns, Protestant and Methodist hymnody, and Scientology’s training exercises exemplify how embodied participation reinforces collective memory and cultural continuity. Nevertheless, an ethnographic inquiry into memory remains a crucial avenue for further research. How can memory be systematically studied in these contexts? Which individuals or groups should be engaged, and what methodologies are best suited to capture the nuances of lived memory practices? Future scholarship would benefit from incorporating ethnographic fieldwork to examine how intangible heritage is activated, negotiated, and transmitted within these communities. Such an approach would provide a richer understanding of the role of memory in shaping the identities of religious minorities and their contributions to the pluralistic cultural landscape of contemporary Rome. Warburg’s methodology, though initially concerned with images, can be extended to these performative dimensions of memory. Ritual practices operate as kinetic Pathosformeln, behavioral memory patterns that transfer emotional intensities and existential meanings across generations and geographies. This broadened Warburgian lens underscores that the city’s religious plurality is not only visible in stone, glass, and mosaic but also audible in prayers, chants, and lectures, and tangible in the communal atmosphere of feasts, fasts, and gatherings. The integration of these religious minorities into Rome’s cultural memory does not occur without tension. Legal frameworks, municipal regulations, interfaith relations, and sometimes anti-migrant sentiment shape the conditions under which religious communities can build, expand, or renovate their places of worship. The Jewish Great Synagogue, constructed after emancipation and Italian unification, marked a radical shift from an era of enforced marginality, with its prominent dome defiantly interrupting a Catholic skyline and asserting a right to public religious visibility (

Antinori 2011). The Mosque of Rome’s minaret similarly signals that Islam, far from being a foreign element, now claims recognized space in the city. Orthodox domes, Protestant spires, Methodist chapels, and Scientology centers all negotiate their presence amid a Catholic-dominated heritage industry that celebrates Rome’s Christian imperium and papal legacy. Sometimes these negotiations spark controversy: debates arise over the height of a minaret, the conversion of a historic structure into a non-Catholic religious center, or the legitimacy of new religious movements to define themselves as “churches” in a city so closely identified with the seat of Catholic authority. Thus, the act of reactivating mnemonic forms and introducing new memory layers can provoke cultural frictions that reveal the contested nature of urban heritage.

These Roman scenarios mirror broader patterns in European cities undergoing religious diversification. London’s repurposed churches turned into Sikh gurdwaras or West African Pentecostal chapels, Berlin’s new mosques and Vietnamese Buddhist temples, and New York’s multiplicity of religious storefronts and transnational congregations all confirm that global migration and religious pluralism reshape urban memory landscapes (

Garbin and Strhan 2017). Warburg’s Mnemosyne suggests that what we witness today is part of a long history of symbolic forms traveling and being continuously reinterpreted. Religious minorities are not anomalies but participants in a historical process of cultural translation and adaptation, each wave of newcomers or emerging religious traditions inscribing fresh mnemonic patterns onto the urban palimpsest. At the same time, the attribution of “heritage” value to minority sites and intangible practices is not a tension-free process. Key stakeholders—be they local authorities, majority communities, or heritage institutions—do not always recognize or validate these new cultural forms, sometimes perceiving them as disruptive or insufficiently “authentic”. Such conflicts reveal that heritage-making itself can be contested: minority communities often must lobby for acknowledgment of their places of worship, rituals, and commemorations as legitimate parts of the city’s memory landscape. Intangible heritage practices—pilgrimages, festivals, interfaith dialogues, and commemorations of martyrdom or deliverance—further ensure that new memories are not only carved in stone but also transmitted through narrative, ritual, and collective remembrance. Understanding religious minorities as co-authors of the city’s cultural memory can reorient heritage preservation and cultural policy. Instead of focusing exclusively on Rome’s classical ruins, Christian basilicas, and Vatican treasures, cultural institutions might also acknowledge that the Great Synagogue, the Mosque of Rome, Orthodox chapels, Protestant and Methodist churches, and Scientology centers contribute to the evolving definition of heritage. Such a perspective aligns with broader scholarly and institutional shifts toward recognizing intangible cultural heritage as equally important, as reflected in UNESCO’s 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. While intangible heritage is often associated with music, dance, oral literature, and craft traditions, religious rituals and community practices are no less integral to the cultural memory that animates urban life. By recognizing that tensions do arise—particularly regarding whose cultural practices are validated and how—the process of heritage-making can move toward more inclusive urban identities. Ultimately, acknowledging religious minorities’ role in heritage-making can help mitigate conflicts by affirming that all communities have stakes in the city’s past, present, and future narratives.

By applying Warburg’s Mnemosyne, we gain methodological clarity on how symbols, motifs, and gestures recurrently emerge in new contexts as “afterlives” (Nachleben) of cultural forms. In Rome, Jewish, Islamic, Orthodox, Protestant, Methodist, and Scientology references do not simply blend into a neutral pluralism; rather, they create intricate constellations of memory. Symbols, forms, and gestures from diverse religious traditions emerge in new contexts, reflecting the dynamic interplay of cultural and spiritual heritage. The selection of religious traditions in this analysis—Jewish, Islamic, Orthodox, Protestant, Methodist, and Scientology—highlights their role as symbolic embassies within the heart of Catholic Christendom. These religious spaces, much like diplomatic missions in a political capital, assert a presence and project cultural identity in a city of unparalleled spiritual significance. By establishing themselves in Rome, these communities engage in a process of representation, signaling their participation in the city’s pluralistic fabric while fostering dialogue and negotiating visibility. Rather than blending into a neutral pluralism, these sites actively contribute to reshaping Rome’s evolving cultural and spiritual landscape. This embassy-like role underscores their importance not only as spaces of worship but also as cultural and political markers within a contested and layered urban environment. The layering of Assyrian-inspired synagogue decor over a Roman substrate, or the placement of an Islamic minaret alongside baroque churches, can be read as cultural montages that reveal the city’s complexity. The intangible dimension, from reciting Hebrew prayers once confined to the ghetto to chanting Quranic verses in a city once largely unfamiliar with Islam, or singing Methodist hymns alongside centuries-old Catholic chant traditions, underscores that the city is not a static repository but a dynamic process of memory reconfiguration. Each religious minority brings a specific memory code, and together they expand the narrative horizon, ensuring that Rome’s cultural memory cannot be reduced to a single tradition. The distribution of religious communities in Rome reflects a dynamic interplay of historical, socio-economic, and cultural factors that have shaped the city’s evolving spiritual landscape. Municipio I, encompassing the historic center, remains dominated by Catholic landmarks, underscoring its role as the epicenter of Rome’s ecclesiastical heritage, while peripheral areas like Municipio VI have become hubs for immigrant-led faith groups, including Pentecostal churches and Islamic prayer rooms. This spatial division highlights the centrality of the historic core for symbolic and monumental religious sites, contrasted with the functional clustering of minority communities in socio-economically accommodating zones. Municipi such as VII exhibit remarkable diversity, housing Catholic, Orthodox, Protestant, and Muslim places of worship, whereas areas like XII are predominantly Catholic, reflecting both the enduring influence of Catholicism and the strategic localization of minorities. Affluent areas such as Municipio II are home to culturally integrated sites like San Paolo Dentro le Mura and the Great Mosque of Rome, blending religious and cultural significance, while lower-income zones, including VIII and XIII, accommodate mixed-use worship spaces that illustrate financial constraints yet emphasize community adaptability. Interfaith proximity in central Municipi fosters opportunities for dialogue and shared cultural engagement, whereas outer zones like IX and XIV show less overlap, indicating spatial segregation and potential for infrastructural growth. The temporal evolution of these communities further underscores migration’s impact, with Orthodox and Muslim groups expanding significantly post-20th century in response to geopolitical shifts. This distribution not only mirrors Rome’s socio-economic stratification but also enriches its urban fabric, presenting a palimpsest of historical continuity and modern plurality, with central monumental sites symbolizing enduring traditions and peripheral zones embracing the transformative energy of religious diversity.