Imitatio Dei, Imitatio Darii: Authority, Assimilation and Afterlife of the Epilogue of Bīsotūn (DB 4:36–92)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Imitatio Dei in DB

2.1. Imitatio Dei: Darius and the Cosmic Lie

2.1.1. The Narrative

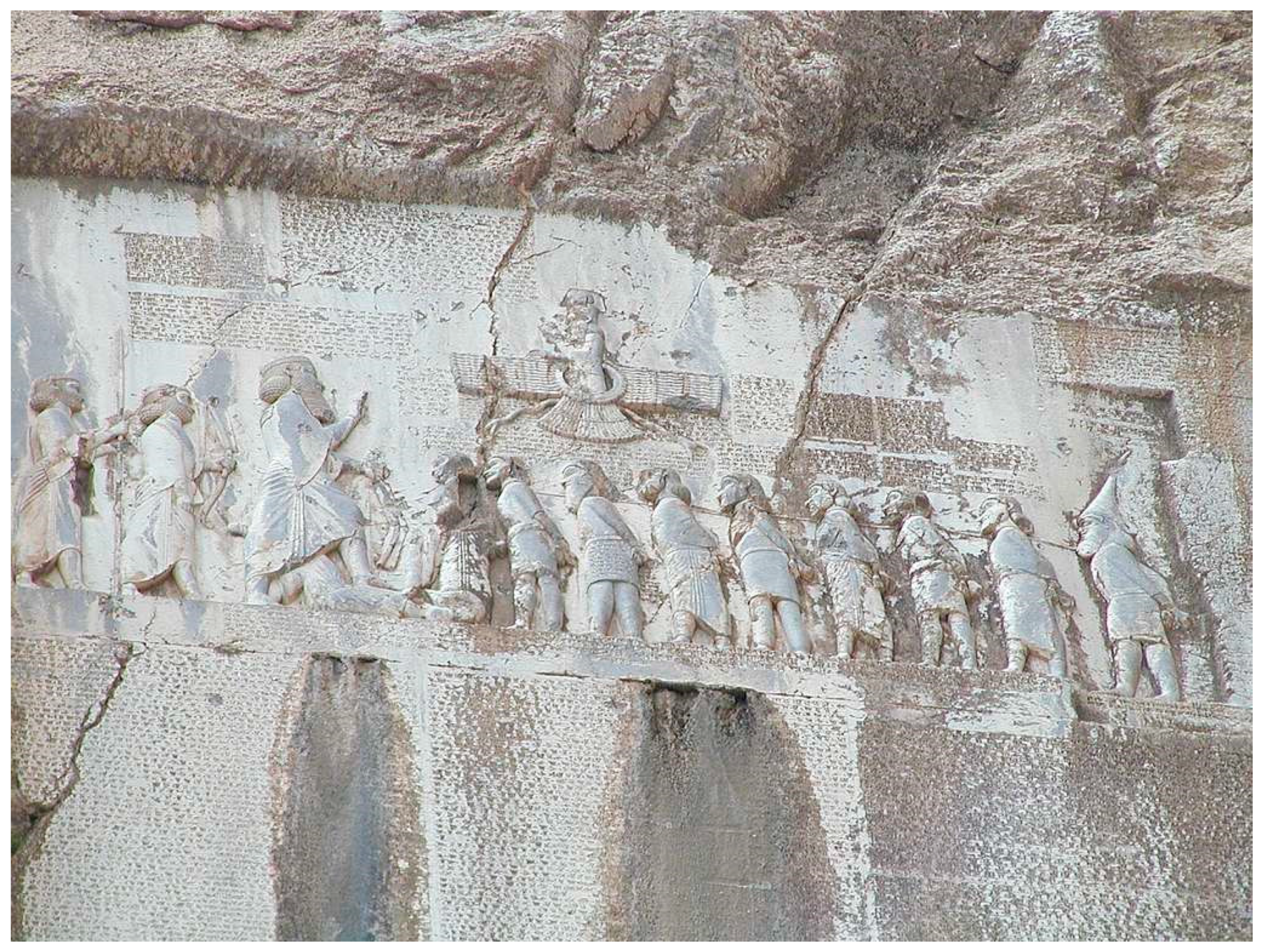

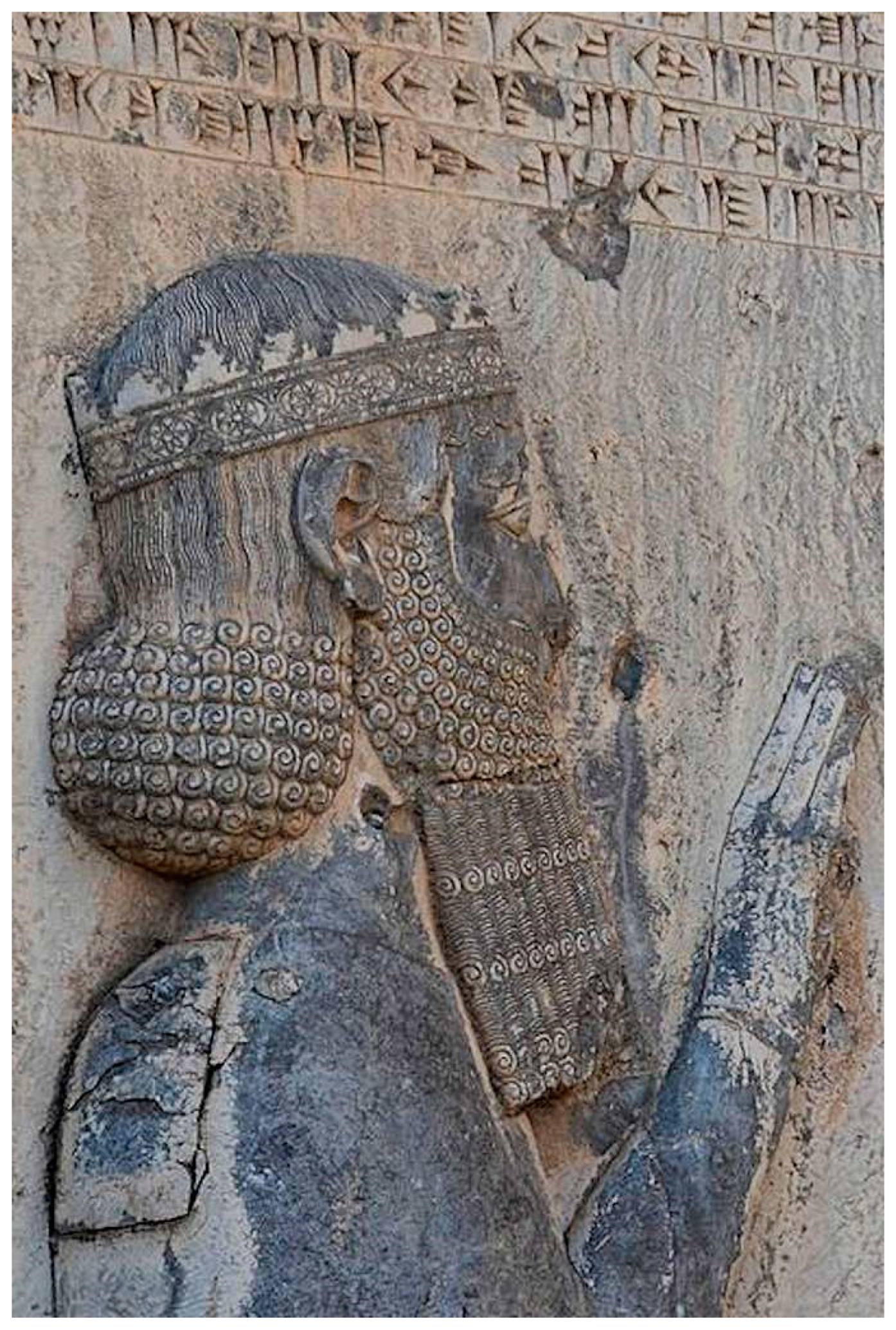

2.1.2. Pictographic Representations

3. The Darius Kerygma as the Epicenter of DB

4. The Darius Kerygma in the Longue Durée

4.1. TADAE C2.1: The Aramaic Bīsotūn Version from Elephantine

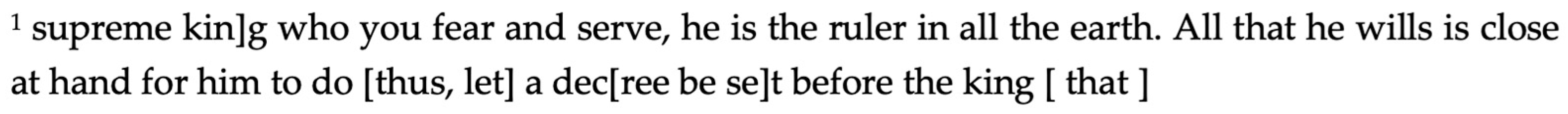

4.2. 4Q550: An Exegetical Legend Based on DB 4:36–69

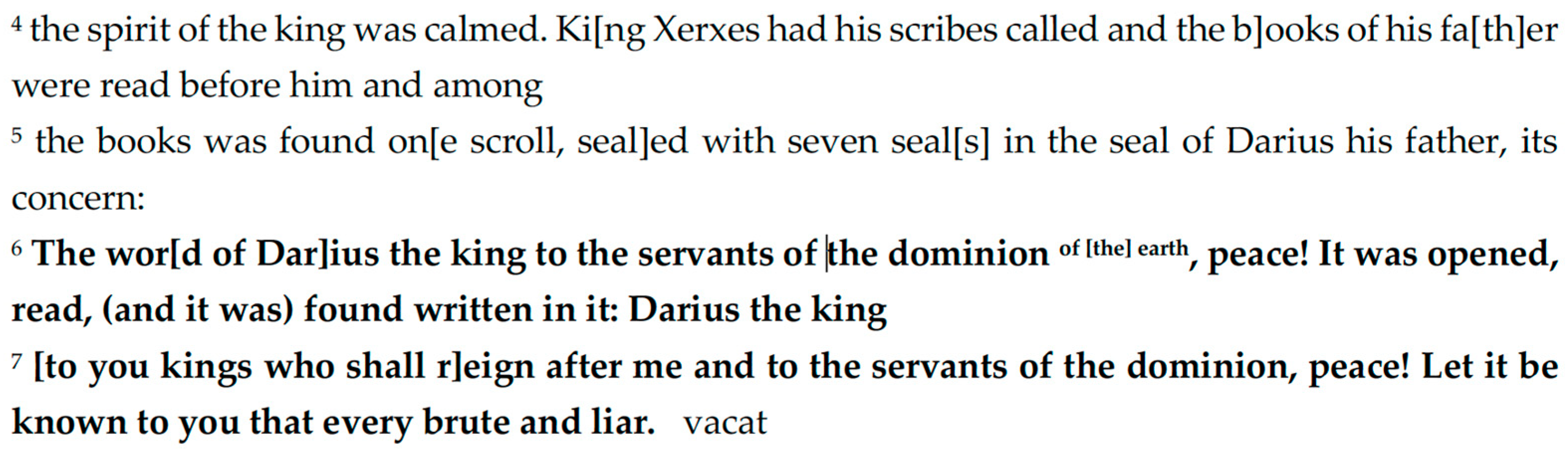

4.2.1. 4Q550: Synopsis

4.2.2. 4Q550 2:4–7 (Incl. Aramaic Text and Translation)

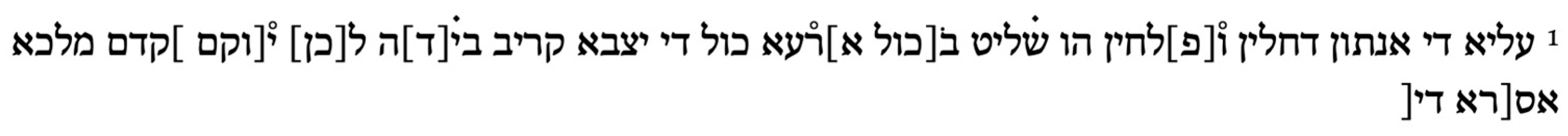

4.2.3. 4Q550 6:1 (Incl. Aramaic Text and Translation)

4.2.4. 4Q550 7

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PN | Personal Name |

| EN | Ethnonym |

| TN | Throne Name |

| GN | Geographic Name |

| Y | Yasna |

| WaDK | Wörterbuch Der Altpersischen Königsinschriften |

| Air. Wb. | Bartholomae, Altiranisches Wörterbuch |

| LSJ | Liddell, Scott, and Jones. A Greek-English Lexicon. |

| 1 | |

| 2 | For a comparative study of all three versions, see (Bae 2001). |

| 3 | I use this term since this is an address in the second person directed at an (imagined) audience. Although the term κήρυγμα is mostly known today in a Christian context as “preaching,” it previously held the more neutral sense of “proclamation” and refers to the function of the κῆρυξ (“herald”). See LSJ s.v. κήρυγμα. |

| 4 | The NB version utilizes parāṣum for “Lie(s)”, which is used in cultic settings in the sense of “to breach an oath” as found in a Hymn to Ištar [ap]-⸢ru⸣-uṣ samam-na-ki me-e-ki ul aṣ-ṣu[r] (“[I] have been false to an oath in your name, I have not observed your rites”), see (Lambert 1959, pp. 50–55, esp. 51). |

| 5 | The verbal form duruj- is found exclusively in DB. |

| 6 | |

| 7 | Lincoln did not discuss the centrality of “the Lie” in DB but focused solely on inscriptions from Persepolis. |

| 8 | Various interpretations have been offered to explain these “other gods.” They were interpreted as foreshadowing the addition of miϑra and anāhitā to the pantheon under Artaxerxes II (Gnoli 1971, pp. 244–45) or possibly to local—Iranian and non-Iranian—deities (see overview in (Skjærvø 2014, p. 179) and most recently (Kellens 2021, p. 1217)). However, the formula “other gods who are” is limited to Darius I and, while many divinities were worshipped in the Achaemenid period (see esp. Henkelman 2021, pp. 1221–42), the divine cooperation between Ahuramazdā and the yazata Arta (ṛta) is the only one that is actually documented in imperial inscriptions of the early Achaemenid period (XPh) with this also being the sole yazata used in royal theophoric names (Artaxerxes). It thus seems to support the reading of this formula as referring to the yazatas, although it may have been interpreted more broadly at the time. |

| 9 | As first proposed by Kellens, Darius/dārayavau- took his throne name as a Zitatname from Y31.7: dāraiiat̰ vahištǝm (manō) “(that) the best thought shall possess” (Kellens and Pirart 1988, pp. 40–41; Kellens 2021, p. 1216). For a more complete treatment of the Achaemenid Zitatnamen including responses to critical views, see Barnea (2025b). |

| 10 | Darius II followed his namesake in a number of respects. He contributed to the repairs of the temple of Eanna at Uruk and was “in all probability responsible for the construction of the temple archives from which thousands of texts have been recovered” (Boyce 1982, pp. 198–99). He was also the first Persian king in over sixty years to build in Egypt and expanded the huge Amun-Hibis temple at El Khargeh built by Darius I “out of piety towards his great forbear and namesake rather than out of any real concern for the Egyptian cult” (Boyce 1982, p. 199). |

| 11 | The word bdny, which he read as the putative Old Iranian *abidaēnā- (Manichaean) Parthian ʾbdyn, (Manichaean) Middle Persian ʾywyn, “style, mode, form, ritual” (Shaked 1995, pp. 279–81). |

| 12 | There are many possible ways the Judeans may have been exposed to the court tale recoded in 4Q550. One hypothetical option is under Parthian influence. The Hasmoneans had a complex relationship with the Parthians, who also conquered Jerusalem in 40 BCE and installed the last Hasmonean king, Antigonus II Mattathias, on the throne whence he ruled as a puppet king for a period of three years. For an overview of the complexities of this period see Atkinson (2022). |

References

- Anagnostou-Laoutides, Evangelia. 2017. In the Garden of the Gods: Models of Kingship from the Sumerians to the Seleucids. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Assmann, Jan. 1992. When Justice Fails: Jurisdiction and Imprecation in Ancient Egypt and the Near East. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 78: 149–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, Kenneth. 2022. Judean Piracy, Judea and Parthia, and the Roman Annexation of Judea: The Evidence of Pompeius Trogus. Electrum 29: 127–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, Chul-Hyun. 2001. Comparative Studies of King Darius’s Bisitun Inscription. Ph.D. thesis, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, Chul-Hyun. 2003. Literary Stemma of King Darius’s (522–486 B.C.E.) Bisitun Inscription: Evidence of the Persian Empire’s Multilingualism. Eoneohag 36: 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Barnea, Gad. 2022. Enforcing YHWH’s Covenant with Blessings and Curses—Imperial Style. TheTorah.com. Available online: https://thetorah.com/article/enforcing-yhwhs-covenant-with-blessings-and-curses-imperial-style (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Barnea, Gad. 2023. The Migration of the Elephantine Yahwists under Amasis II. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 82: 103–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnea, Gad. 2024. The Seven-Sealed Scroll in Practice, Legend and Theology: From imperial administration and Qumran to the book of Revelation. In Qumran and the New Testament. Edited by Jörg Frey. In BETL. Leuven: Peeters, pp. 411–25. [Google Scholar]

- Barnea, Gad. 2025a. 4Q550 Bīsotūn Exegetical Legend: A Critical Edition. DSSE. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Barnea, Gad. 2025b. Some Achaemenid Zoroastrian Echoes in Early Yahwistic Sources. Iran: Journal of the British Institute of Persian Studies. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnea, Gad. 2025c. The Significance of ṛtācā brzmniy in Xerxes’ Cultic Reform: A new light on the “Daiva inscription” (XPh). Iran and the Caucasus 29.2: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bledsoe, Seth A. 2015. Conflicting Loyalties: King and Context in the Aramaic Book of Ahiqar. In Political Memory in and after the Persian Empire. Edited by Jason M. Silverman and Caroline Waerzeggers. In Ancient Near East Monographs. Atlanta: SBL Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce, Mary. 1982. A History of Zoroastrianism. Leiden: Brill, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Brisch, Nicole Maria. 2022. Gods and Kings in Ancient Mesopotamia. In Sacred Kingship in World History: Between Immanence and Transcendence. Edited by Ahmed. Azfar Moin and Alan Strathern. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 72–93. [Google Scholar]

- Canepa, Matthew P. 2013. The transformation of sacred space, topography, and royal ritual in Persia and the ancient Iranian world. In Heaven on Earth: Temples, Ritual, and Cosmic Symbolism in the Ancient World. Edited by Deena Ragavan. In Oriental Institute Seminars. Chicago: Oriental Institute, pp. 319–72. [Google Scholar]

- Charpin, Dominique. 2013. “I Am the Sun of Babylon”: Solar Aspects of Royal Power in Old Babylonian Mesopotamia. In Experiencing Power, Generating Authority: Cosmos, Politics, and the Ideology of Kingship in Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. Edited by Jane A. Hill, Philip Jones and Antonio J. Morales. In Penn Museum International Research Conferences. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, pp. 65–96. [Google Scholar]

- Cowley, Arthur E. 1923. Aramaic Papyri of the Fifth Century B.C Edited, With Translation and Notes. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eliade, Mircea. 1978. A History of Religious Ideas Volume 1: From the Stone Age to the Eleusinian Mysteries. Translated by Willard R. Trask. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frandsen, Paul John. 2008. Aspects of Kingship in Ancient Egypt. In Religion and Power: Divine Kingship in the Ancient World and Beyond. Edited by Nicole Maria Brisch. Chicago: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, pp. 47–73. [Google Scholar]

- Gansell, Amy, Tero Alstola, Heidi Jauhiainen, and Saana Svärd. 2025. Neo-Assyrian Imperial Religion Counts: A Quantitative Approach to the Affiliations of Kings and Queens with Their Gods and Goddesses. Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions 24: 236–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershevitch, Ilya. 1979. The Alloglottography of Old Persian. Transactions of the Philological Society 77: 114–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnoli, Gherardo. 1971. Politica Religiosa E Concezione Della Regalità Sotto I Sassanidi. In Atti Del Convegno (Internazionale Sul Tema: La Persia Nel Medioevo (Roma 1970) Internazionale Sul Tema: La Persia Nel Medioevo (Roma, 31 Marzo—5 Aprile 1970). Roma: Accademia nazionale dei Lincei, pp. 225–53. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield, Jonas C., and Bezalel Porten. 1982. The Bisitun inscription of Darius the Great, Aramaic Version. London: Lund Humphries. [Google Scholar]

- Haran, Menahem. 1982. Bible Scrolls from Qumran to the Middle Ages. Tarbiz 51: 347–82. [Google Scholar]

- Henkelman, Wouter. 2021. The Heartland Pantheon. In A Companion to the Achaemenid Persian Empire. Edited by Bruno Jacobs and Robert Rollinger. Hoboken: Wiley, pp. 1221–42. [Google Scholar]

- Herman, David. 1994. Textual “You” and Double Deixis in Edna O’Brien’s “A Pagan Place”. Style 28: 378–410. [Google Scholar]

- Holm, Tawny L. 2013. Of Courtiers and Kings: The Biblical Daniel Narratives and Ancient Story-Collections. EANEC. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Philip. 2020. Divine and Non-Divine Kingship. In A Companion to the Ancient Near East, 2nd ed. Edited by Daniel C. Snell. In Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 243–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kadari, Tamar. 2022. As Sweet as Their Original Utterance: The Reception of the Bible in Aggadic Midrashim. Journal of the Bible and its Reception 9: 203–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavvadas, Nestor. 2024. Chrysostomic Trajectories: The Homilies on John and Syriac Exegesis from Lazaros of Beth Qandasa to Moses bar Kepha. In Fresh Perspectives on St John Chrysostom as an Exegete. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Kellens, Jean. 2021. The Achaemenids and the Avesta. In A Companion to the Achaemenid Persian Empire. Edited by Bruno Jacobs and Robert Rollinger. Hoboken: Wiley, pp. 1211–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kellens, Jean, and Eric Pirart. 1988. Les Textes Vieil-Avestiques. Vol. I: Introduction, Texte et Traduction. Wiesbaden: L. Reichert. [Google Scholar]

- Koldewey, Robert, and Friedrich Wetzel. 1932. Die Konigsburgen von Babylon Teil 2., Die Hauptburg und der Sommerpalast Nebukadnezars im Hügel Babil. 2 vols. Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichung der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft. Osnabrück: O. Zeller. [Google Scholar]

- Kratz, Reinhard Gregor. 2022. Aḥiqar and Bisitun: The Literature of the Judeans at Elephantine. In Elephantine in Context. Edited by Bernd U. Schipper and Reinhard Gregor Kratz. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, pp. 301–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, Wilfred G. 1959. Three Literary Prayers of the Babylonians. Archiv für Orientforschung 19: 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Bruce. 2008. The Role of Religion in Achaemenian Imperialism. In Religion and Power: Divine Kingship in the Ancient World and Beyond. Edited by Nicole Maria Brisch. Chicago: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, pp. 221–41. [Google Scholar]

- Luschey, Heinz. 1968. Studien zu dem Darius-Relief in Bisutun. AMI 1: 63–94. [Google Scholar]

- Maricq, André. 1958. Classica et Orientalia: 5. Res Gestae Divi Saporis. Syria 35: 295–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, M. Ángeles. 2015. Double deixis, inclusive reference, and narrative engagement: The case of YOU and ONE. Babel—AFIAL Aspectos de Filoloxía Inglesa e Alemá 24: 145–63. [Google Scholar]

- Milik, Józef T. 1992. Les modèles araméens du Livre d’Esther dans la grotte 4 de Qumrân. Revue de Qumrân 15: 321–406. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, Kathleen D. 2008. When Gods Ruled: Comments on Divine Kingship. In Religion and Power: Divine Kingship in the Ancient World and Beyond. Edited by Nicole Maria Brisch. Chicago: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, pp. 267–70. [Google Scholar]

- Na’aman, Nadav. 2011. The “Discovered Book” and the Legitimation of Josiah’s Reform. Journal of Biblical Literature 130: 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrabadi, Behzad Mofidi. 2004. Beobachtungen zum Felsrelief Anubaninis. Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie 94: 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panaino, Antonio. 1986. hainā-, dušiyāra-, draṷga-: Un confronto antico-persiano avestico. Socalizio Glottologico Milanese 21: 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Panaino, Antonio. 2022. Between Semantics and Pragmatics: Origins and Developments in the Meaning of dastgerd. A New Approach to the problem. In Sasanidische Studien. Edited by Shervin Farridnejad and Touraj Daryaee. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, vol. I, pp. 215–42. [Google Scholar]

- Panaino, Antonio. 2023. Sacred Kingship in Ancient Iran: The Symbolic Language of Royalty in Achaemenid and Sasanian Ideologies. Studi Iranici Ravennati 4: 275–98. [Google Scholar]

- Pelling, Christopher. 1996. The Urine and the Vine: Astyages’ Dreams at Herodotus 1.107–8. The Classical Quarterly 46: 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porten, Bezalel, and Ada Yardeni. 1993. Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt (TADAE). Jerusalem: The Hebrew University, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Puech, Émile. 2009. Qumrân Grotte 4 XXVII: Textes Arameéns Deuxième Partie. 37 vols. Edited by Emanuel Tov. Discoveries in the Judean Desert. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rawlinson, Henry Creswicke. 1848. The Persian Cuneiform Inscription at Behistun, Decyphered and Translated; With a Memoir on Persian Cuneiform Inscriptions in General, and on That of Behistun in Particular. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 10: i–lxxi, 1–265, 268–349. [Google Scholar]

- Riddell, Peter G. 1997. The Transmission of Narrative-Based Exegesis in Islam: Al-Baghawī’s Use of Stories in his Commentary on the Qurʾān, and a Malay Descendent. Leiden: Brill, pp. 57–80. [Google Scholar]

- Root, Margaret Cool. 2013. Defining the Divine in Achaemenid Persian Kingship: The View from Bisitun. In Every Inch a King: Comparative Studies on Kings and Kingship in the Ancient and Medieval Worlds. Edited by Lynette G. Mitchell and Charles P. Melville. In Rulers & Elites. Boston: Brill, pp. 23–65. [Google Scholar]

- Sabbahy, Lisa. 2021. Kingship, Power, and Legitimacy in Ancient Egypt: From the Old Kingdom to the Middle Kingdom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sachau, Eduard. 1911. Aramäische Papyrus und Ostraka aus einer judischen Militar-Kolonie zu Elephantine: Altorientalische Sprachdenkmaler des 5. Jahrhunderts vor Chr. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs. [Google Scholar]

- Sancisi-Weerdenburg, Heleen. 1999. The Persian Kings and History. In The Limits of Historiography: Genre and Narrative in Ancient Historical Texts. Edited by Christina Shuttleworth Kraus. Leiden: Brill, pp. 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, Rüdiger. 1991. The Bisitun Inscriptions of Darius the Great: Old Persian Text. Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum. Texts 1. London: On behalf of Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum by School of Oriental and African Studies, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, Rüdiger. 2023. Die Altpersischen Inschriften der Achaimeniden: Editio Minor Mit Deutscher Übersetzung, 2. Korrigierte Auflage. Wiesbaden: Reichert. [Google Scholar]

- Scrignoli, Micol. 2018. duruj-, drauga-, draujana-, dallo studio delle valenze semantiche attestate all’individuazione della triade iranica nella lingua antico persiana. In Studi Iranici Ravennati II. Edited by Andrea Piras, Antonio Panaino and Paolo Ognibene. Milano: Mimesis, pp. 259–70. [Google Scholar]

- Segal, Judah B. 1983. Aramaic Texts from North Saqqâra, with Some Fragments in Phoenician. London: Egypt Exploration Society. [Google Scholar]

- Shaked, Shaul. 1995. Qumran: Some Iranian Connections. In Solving Riddles and Untying Knots: Biblical, Epigraphic, and Semitic Studies in Honor of Jonas C. Greenfield. Edited by Ziony Zevit, Seymour Gitin and Michael Sokoloff. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 265–69. [Google Scholar]

- Sims-Williams, Nicholas. 1981. The Final Paragraph of the Tomb-Inscription of Darius I (DNb, 50–60): The Old Persian Text in the Light of an Aramaic Version. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 44: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skjærvø, Prods O. 2014. Achaemenid Religion. Religion Compass 8: 175–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorlin, Sandrine. 2022. The Stylistics of ‘You’: Second-Person Pronoun and Its Pragmatic Effects. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tavernier, Jan. 1999. The Origin of DB Aram 66–69. Nouvelles Assyriologiques Brèves et Utilitaires 4: 83–84. [Google Scholar]

- Tavernier, Jan. 2001. An Achaemenid Royal Inscription: The Text of Paragraph 13 of the Aramaic Version of the Bisitun Inscription. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 60: 161–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavernier, Jan. 2021. Sar-e Pol-e Zahab relief (Anubanini). In The Encyclopedia of Ancient History: Asia and Africa. Edited by Daniel T. Potts, Ethan Harkness, Jason Neelis and Roderick McIntosh. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Utas, Bo. 1965–1966. Old Persian Miscellanea. Orientalia Suecana 14–15: 118–40. [Google Scholar]

- von Voigtlander, Elizabeth N. 1978. The Bisutun Inscription of Darius the Great. Babylonian Version. Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum Part I: Inscriptions of Ancient Iran Vol. II: The Babylonian Version of the Achaemenian Inscriptions. Texts I. London: Lund Humphries. [Google Scholar]

- Weissbach, Franz Heinrich. 1903. Babylonische Miscellen. 4 vols. Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichung der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs’sche. [Google Scholar]

- Wesselius, Jan W. 1984. Review of the Bisitun Inscription of Darius the Great: Aramaic Version. Bibliotheca Orientalis 41: 440–45. [Google Scholar]

- Wills, Lawrence M. 1990. The Jew in the Court of the Foreign King: Ancient Jewish Court Legends. Harvard Dissertations in Religion. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, vol. 26. [Google Scholar]

- Winnerman, Jonathan. 2023. Divine Kingship and the Royal Ka. In Ancient Egyptian Society: Challenging Assumptions, Exploring Approaches. Edited by Danielle Candelora, Nadia Ben-Marzouk and Kathlyn M. Cooney. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 40–48. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barnea, G. Imitatio Dei, Imitatio Darii: Authority, Assimilation and Afterlife of the Epilogue of Bīsotūn (DB 4:36–92). Religions 2025, 16, 597. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16050597

Barnea G. Imitatio Dei, Imitatio Darii: Authority, Assimilation and Afterlife of the Epilogue of Bīsotūn (DB 4:36–92). Religions. 2025; 16(5):597. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16050597

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarnea, Gad. 2025. "Imitatio Dei, Imitatio Darii: Authority, Assimilation and Afterlife of the Epilogue of Bīsotūn (DB 4:36–92)" Religions 16, no. 5: 597. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16050597

APA StyleBarnea, G. (2025). Imitatio Dei, Imitatio Darii: Authority, Assimilation and Afterlife of the Epilogue of Bīsotūn (DB 4:36–92). Religions, 16(5), 597. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16050597