Abstract

In 1979, Ayatollah Khomeini spearheaded the Islamic Revolution, toppling the secular Shah regime, a move that resonated with millions of people. Fast-forward to 2025, there has been a notable rise in secularism in Iran, even among 1979’s religious clerics. Currently, 73% of Iranians support the idea of separating Islam from the state and advocating for a secular government. As a result, there have been widespread anti-Islamist regime and pro-democratic protests during different periods, such as 2009–2010, 2017–2018, 2019–2020, and 2022–2023. The most recent development in 2024 was the victory of reformist candidate Masoud Pezeshkian in the presidential elections, defeating conservative candidate Saeed Jalili. This study examines the factors driving the rise of secularism, namely globalization, the systemic issues within the Islamic regime, the significant influence of the Iranian diaspora, and the impact of rapid urbanization.

1. Introduction

It is commonly accepted that the first modern protests in Iran’s history took place in 1891, when Ayatollah Mirza Hossein Shirazi issued a religious fatwa prohibiting his followers from using tobacco products (Batmanghelidj 2016, p. 99). Ayatollah Mirza aimed to thwart the British tobacco company Imperial Tobacco from gaining a foothold in Iran, a move he perceived as a potential tool for further imperial control. The tobacco revolts marked the first time that people rose against the monarchy and its autocratic decisions.

Following the 1979 Islamic Revolution led by Khomeini, people continued to protest against the authoritarian decisions of their religious monarchy. For instance, the first anti-revolution protests began in March, coinciding with International Women’s Day, just one month after Khomeini’s new regime was established (Kian 1997). Initially, these protests were a celebration of International Women’s Day; however, they quickly turned into widespread protests against the Iranian Revolution’s restraints of women’s rights, particularly the regime’s statement of the mandatory hijab (veiling) (Kian 1997). These protests lasted six days, from 8 March to 14 March 1979, and attracted thousands of women; however, participants faced violent reprisals and intimidation from pro-Khomeini Islamist forces.

In 2009, three decades after the Islamic Revolution, hundreds of Iranians protested the results of the presidential election, demanding the annulment of the elections. The protesters asserted that their votes had been stolen by the regime, which staged an electoral coup and manipulated the electoral process to support its preferred candidate rather than the reformist one. This movement, known as the Green Movement or Persian Spring, endured for nearly a year, a testament to the resilience of the Iranian people. The Iranian regime responded to the protests with a variety of repressive measures, ultimately quelling the demonstrations without addressing the protesters’ demands.

Currently, people are protesting not only against the unrestricted use of tobacco products but also to express their religious, political, and social beliefs. For example, Iranian protesters chant “Zan, Zendegi, Azadi” (Woman, Life, Freedom) instead of focusing solely on tobacco issues. The struggle against repression and the fight for freedom persist in Iran despite the passage of centuries. There is also a growing secular movement within Iran’s Islamic and repressive regime, advocating for the secular, liberal, and democratic rights of the Iranian people.

As Arab and Maleki stated:

Compared with Iran’s 99.5% census figure, we found that only 40% identified as Muslim. In contrast with state propaganda that portrays Iran as a Shia nation, only 32% explicitly identified as such, while 5% said they were Sunni Muslim and 3% Sufi Muslim. Another 9% said they were atheists, along with 7% who prefer the label of spirituality. Among the other selected religions, 8% said they were Zoroastrians-which we interpret as a reflection of Persian nationalism and a desire for an alternative to Islam, rather than strict adherence to the Zoroastrian faith-while 1.5% said they were Christian.(Arab and Maleki 2020)

This article’s primary objective is to enlighten on the critical factors driving the emergence of secular trends in Iran. Among these, globalization stands out as a transformative force, while the shortcomings of the Islamic regime have fostered discontent and calls for secular change. The influential Iranian diaspora also plays a vital role in shaping perspectives and attitudes, further strengthening secular movements. Rapid urbanization adds to this dynamic, creating an environment that is conducive to progressive ideas. Together, these interconnected elements are fostering a rise in secularism and actively propelling movements that redefine Iran’s political and societal landscape.

The following four factors have been selected for their significant impact on the rise of secular trends in Iran. First, globalization and the rise of nonreligious values are crucial in influencing anti-religious and reformists’ sentiments. People are actively embracing globalization and passionately advocating for change. Iran is evolving in response to global developments, and Iranians’ expectations—especially regarding personal freedoms—have increased substantially, leading to a decline in traditional and conservative religious values. Second, the shortcomings of the Iranian regime also affect anti-regime factions, including secular groups. As disillusioned regime supporters abandon it, the strength and popularity of these anti-regime factions increase.

Additionally, the Iranian diaspora significantly shapes secular trends in Iran by introducing new ideas and lifestyles to those living in Iran. Their influence motivates and encourages calls for reform and secular change within the Iranian regime. Lastly, urbanization contributes to these trends, as more people move to city centers where access to the Internet, mass communication, socialization, and opportunities to gather and exchange ideas are more readily available. Urban places function as dynamic modernization centers, producing diverse novel ideas. These four critical factors are examined to highlight their connection to the rise of secular trends in Iran.

Accordingly, this paper contributes significantly to the literature on secular trends in Iran by examining four key factors illuminating the rise of secular trends in Iran. First, it highlights how globalization has reshaped societal norms and spurred the growth of secularism throughout the nation. Second, it analyzes the shortcomings of the Islamic regime, demonstrating how these inadequacies have fueled discontent and a shift toward secular values. Furthermore, the paper explores the important roles of the Iranian diaspora and rapid urbanization, which both further influence and accelerate secular trends. This study presents a compelling case for understanding the dynamics of secularization in Iran by examining the interconnections among these four factors. While it acknowledges that these factors are not the only contributors to the rise of secularism, they are essential for grasping the complexities of this phenomenon within the context of Iran’s Islamic regime.

This study utilizes a single case methodology to conduct an in-depth analysis of four interrelated and interdependent factors that significantly influence the sociocultural landscape of Iran. By examining these factors, the research effectively reveals the intricate and interconnected nature of these factors and their influence on the prevailing secular trends in the country. Far from being incompatible, these factors are shown to be complementary, each enhancing and reinforcing the impact of the others in shaping Iran’s evolving dynamics. This nuanced understanding underscores the complexity of these relationships and their collective influence on the broader societal context.

This study comprehensively analyzes the various factors influencing secular trends in Iran and the intricate connections among them. By addressing this critical gap in the existing literature on Iranian secularism, it offers valuable insights into the complexities surrounding secularization. It is important to note that these factors are not presented as the sole determinants of these trends; instead, they are emphasized as significant, interconnected elements that collectively shape the evolving secular landscape in Iran. This exploration of relationships provides a more nuanced understanding of the underlying dynamics within this distinctive socio-cultural context.

Moreover, it is essential to recognize that the Iranian regime operates on a foundation of anti-democratic principles, exhibiting a profound intolerance for any factions that oppose its authority, including those advocating for secularism and reform. The regime’s oppressive tactics, such as censorship, imprisonment, and the violent suppression of dissent, create a hostile environment for the emergence of secular movements. By exploring how secular trends can develop in such a repressive context, we can gain valuable insights into the strategies and conditions that facilitate the rise of secular ideologies or opposing factions in other autocratic regimes worldwide. Understanding these dynamics is vital for those seeking to promote democratic change and secular governance, as it highlights the resilience of social protests and the potential for transformative ideas to take root, even in the most restrictive environments.

2. Literature Review

There is no universally accepted definition of secularism; however, it is commonly understood as the separation of religion and state. As noted by Kettell, “The state should neither favor, disfavor, promote, nor discourage any particular religious (or nonreligious) belief and viewpoint over another” (2019, p. 3). Achieving a clear separation between state and religion is quite challenging, as both exert a significant influence over people’s public and private lives. Despite advancements in technology and the progression of secular values across the globe, 75 countries, representing 40% of the world, still have an official religion (Becker et al. 2024).

The varieties of secularism vary significantly. Mostly, it is categorized into “soft”, “hard”, “exclusivist”, “inclusivist”, “active”, and “passive” types (Kosmin and Keysar 2009; Kuru 2009). These classifications appear from the state’s approach to religion. France serves as a prime example of a secular state that effectively limits the influence of religion on government affairs, ensuring that the French government operates independently of religious institutions. In contrast, the United States adopts a more balanced approach to the relationship between religion and the state, maintaining a clear separation between the two. In summary, religions have been the subject of whether they should be excluded from or controlled (included) by the state. One perspective supports freedom of religion, like in the United States, while the opposing view highlights freedom from religion, as seen in France.

Supporters of the role of religion in public life argue that religion offers many valuable public goods and helps individuals to find meaning and identity (Kettell 2019, p. 1). They contend that efforts to exclude religion from the public sphere are illiberal, undemocratic, and intolerant (Kettell 2019, p. 1). According to these supporters, religious discourses and worldviews are comparable with other ideologies, such as liberalism, socialism, or conservatism, and should be treated equally (Stepan 2000; Wolterstorff 2008). They defend that repressing religions may lead to the rise of extremism and fanaticism, whether embracing religions and religious perspectives may promote moral values that address social injustices, poverty, inequality, and discrimination. Thus, religion is a significant public good or social glue, fostering public trust.

On the other hand, advocates of secularism contend that the separation of religion and state generates the optimum environment for safeguarding the rights and freedoms of all citizens, regardless of their beliefs and religious views (Sweetman 2021, p. 33; Kettell 2019, p. 1). The core assertion here is that secularism possesses a dual function: it not only shields the state from religious influence but also protects religion from governmental interference. This framework ensures rights for both religious and non-religious individuals, thereby fostering conditions that promote the common good, often referred to as public reason and benefit (Rawls 1997). For example, research by Zuckerman indicates that secular societies generally outperform religious ones across various social indicators, such as social inequality, family stability, violent crime rates, juvenile delinquency, substance abuse, and overall happiness (Zuckerman 2008).

Secularization theories delve into the gradually diminishing social significance of religious institutions, practices, and beliefs. These theories can be categorized into several primary perspectives. The modernization theory asserts that religion becomes less central to daily life as societies evolve and modernize through industrialization, urbanization, and the expansion of education (Douglas 1982). The premise suggests that enhanced rationality and scientific understanding decrease the reliance on religious explanations.

The secularization hypothesis developed by scholars such as Wilson and Bruce posits that the development of contemporary institutions, including education and mass media, results in a decline in the authority of religious institutions (Wilson 2016; Bruce 2002). Additionally, the pluralization theory argues that the emergence of diverse belief systems and the coexistence of various religions within contemporary societies contribute to diminishing religious authority (Banchoff 2007). Individuals exposed to various worldviews may opt not to adhere to traditional religious beliefs strictly.

Post-secularism scholars, in response to secularization trends, argue that contemporary society is experiencing a resurgence of interest in spirituality and religious practice, albeit in individualized and diverse forms (Possamai 2017). This theory suggests that modernity encapsulates secular and religious elements rather than existing solely within a secular framework. Cultural secularization emphasizes the broader cultural shift from religious norms and values in public life (Pecora 2006). It underscores changes in moral frameworks and social behaviors that reflect a reduced influence of religious narratives.

The religious market theory was introduced by economists such as Stark and Bainbridge, who examined religion through the lens of supply and demand (Stark and Bainbridge 1985). A competitive religious marketplace may lead to heightened levels of individual religious commitment, even within predominantly secular cultures. Each of these theories plays a pivotal role in fostering a comprehensive understanding of the manifestations of secularization and the various factors influencing this complex process across different societies.

Prior to the 1979 revolution, Iran exemplified a secular state model that was antagonistic toward religious groups, perceiving them as potential rivals for political power. The secular Shah ruled Iran from 1925 until 1979. Secularism was formalized as state policy shortly after Reza Shah Pahlavi ascended to the throne in 1925. He outlawed any public displays or expressions of religious faith, including the wearing of the headscarf (hijab) and chador by women, as well as facial hair on men (except mustaches) (Fatehrad 2017). On 7 January 1936, the Shah enacted the Unveiling Act, which prohibited the veil in public settings (Chehabi 2012).

The women of Iran had been veiled for a long time, compelled by state policies to unveil in public. The Unveiling Act aimed to promote greater participation of Iranian women in public life, facilitating their involvement in various settings, such as cafes, workplaces, retail environments, and educational institutions. However, veiled or conservative Iranian women faced oppression from the Shah’s secular regime (Fatehrad 2017). Many veiled Iranian women perceived the new public spaces as dangerous and unfamiliar (namahram) (Bāmdād 1977, pp. 7–23). As a result, they often chose to stay home, sacrificing their freedom to protect their veils. The Shah adopted a strict and exclusive attitude toward religious beliefs and movements. While his secular vision helped secular Iranian women, it did not extend the same advantages to religious ones. Consequently, the policies of secular Iran favored secular individuals, leading to a form of positive discrimination, where the principle of freedom became a casualty of these discriminatory practices.

Reza Shah aimed to secularize Iran and reduce the influence of the Shi’a clergy on both the government and society. Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, his son and successor, continued this policy of strict secularization.1 As a result, he promoted close relationships with secular nations like France, the United States, and Turkey. Mohammad Reza Shah mandated that Shi’a clerical students attend state-run universities to obtain religious certification and credentials for preaching, similar to the requirements for Catholic and Christian theology schools. Additionally, in the 1970s, he took measures to exclude Shi’a clergy from Parliament and imposed restrictions on public displays of religion and religious observance.

After 1979, in contrast to the reign of the Shah, Khomeini’s Iran regarded secularism as a form of Western colonialism and a tool of imperialism. This perspective considered secularism to be a product of Western culture that aimed to marginalize religions, particularly Islam, which conflicted with the Iranian beliefs. Khomeini came to power in 1979, and the new constitution aimed to incorporate the religious principles derived from the Twelver Ja’fari school of Shia Islam. This constitution explicitly stated that “All civil, penal, financial, economic, administrative, cultural, military, political, and other laws and regulations must be based on Islamic criteria” (Article 4) and declared the Twelver Ja’fari school of Islam as the official state religion (Article 12). According to Khomeini, “Where there is no velayat-e faqih (Guardianship of the Islamic Jurisprudent), there is idolatry… Idols disappear only if God designates authorities” (Khomeini 1979, p. 34; Boroumand and Boroumand 2000, p. 121). Therefore, secularism is seen as antireligious and, consequently, anti-Islamic. In other words, the authority of God cannot be replaced or challenged by the secular state’s governance of the people (Cox 2013, p. xxx).

Hassan and Dabbagh stated:

Combined with a further claim that Islamic ideals are (or ought to be) at the fundamental kernel of Iranian cultural identity, secularism is considered to be anti-Iranian, and a means by which foreign powers have aimed to homogenize the interests and evaluative outlook of Iranians in a way that more closely aligns with their own, thus facilitating a greater sphere of influence and an easier extraction of resources.(Hassan and Dabbagh 2023)

Iran’s new authoritarian theocratic (mullah) regime has implemented policies that are anti-secular and pro-religious, aiming to control and reshape society (Sweetman 2021, p. 305). Shia Islam and Islamic morals serve as tools for the regime to enforce strict control over the population. Khomeini’s religious government replaced the secular autocratic regime of the Shah. Women who were once forced to unveil themselves are now compelled to wear the veil. Those who refuse to veil in public are labeled as infidels and face oppression from the regime. While traditional women have experienced empowerment, secular Iranian women encounter segregation. The regime’s authoritative policies exploit the secular and anti-secular context (Fatehrad 2017). It justifies its actions as a means of civilizing society by returning to its historical and religious roots. The end of the Shah’s secular policies is framed as a rejection of Western hegemony and a return to Iran’s origins. The anti-secular stance of Shia Iran is one of the most significant elements that distinguishes the country from others. As Boroumand states: “It is a theocracy founded on the political privileges of a clerical oligarchy” (2000, p. 116).

However, Pargoo (2021) argues that contrary to the expectation that the 1979 Khomeini revolution would reinforce Islamic authority, a gradual secularization or Islamic secularity has occurred within society and governance (p. 16). Pargoo highlights how the initial fervor for Islamic governance has evolved, leading to increasing public disillusionment with theocratic rule. This secularizing trend is marked by a growing desire among citizens for personal freedoms and a more pluralistic society, especially among the youth (pp. 16–18). He examines various factors contributing to this shift, primarily the influence of globalization, technological advancements, and a rising dissatisfaction with the political elite (pp. 30–36).

Similarly, in “Crisis in the Shiite Crescent: Ascendancy of Secularism”, Roomi and Kazemi analyze the changes in governance and social values after the 1979 revolution (Roomi and Kazemi 2021). They argue that there is a gradual shift toward secularism rather than an increase in Islamic authority. This change stems from public disappointment with theocratic rule and a growing desire for personal freedoms, particularly among the youth. Factors such as globalization, new technology, and frustration with political leaders mainly contribute to this trend. The authors demonstrate that Islamic institutions and practices are being reinterpreted in a more secular manner as Iranian society faces challenges related to identity, modernization, and individual rights.

The relationship between nationalism and secularism is thoroughly examined by Martin (2013) and Abdolmohammadi (2015). Both authors delve into the historical roots of Islamic nationalism and its resurgence after the 1979 revolution, which sought to establish an Islamic identity for the nation. Despite a robust Islamic framework, Martin posits that there remains a significant undercurrent of secularism, particularly among younger generations who strive for personal freedoms and modernization (p. 206). Likewise, Abdolmohammadi emphasizes that many Iranians, disillusioned by the restrictive nature of the Islamic Republic, are advocating for a political and cultural landscape that upholds democratic values and civil liberties (pp. 14–15). Both authors also highlight the influence of external factors, global norms, and social movements that challenge traditional values, suggesting that the ongoing dialogue between these competing ideologies could shape the future of Iran. Overall, their work underscores the dynamic interplay between Islamic nationalism and secular aspirations in the evolution of Iranian society.

In addition to the existing literature, this study also argues that the 1979 revolution did not create a robust and stable Islamic state. There have been ongoing anti-regime protests and social movements throughout Iran’s history, although their motivations, intensity, and frequency have varied. Recently, there has been a noticeable rise in anti-regime protests advocating for secularism and reform (see Table 1).2 This study examines four primary factors contributing to this growing demand, namely the effects of globalization, the Iranian diaspora’s increased influence, regime failures, and the consequences of rapid urbanization.

Table 1.

The number of major Iranian protests from 2009 to 2023.

3. Globalization

Today’s Iran is not the same as it was in 1979. The country has undergone significant changes due to global and regional developments. Globalization plays an important role in the rise of secular trends in Iran because it facilitates the exchange of ideas, values, and lifestyles that challenge traditional beliefs (Taylor 2007). There are important connections between globalization and secular trends in Iran. Iranians are increasingly traveling and learning about events happening around the world. This cultural exchange is driven by the globalization of culture through the Internet, social media, and travel. Additionally, global access and globalization demonstrate that various paths to modernity and secularization allow for the preservation of national and ethnic identities and cultural values without necessitating alignment with any Western nation or civilization (Eisenstadt 2017; Wohlrab-Sahr and Burchardt 2012). As a result, many pro-reformist and pro-secular Iranians, particularly the youth in Iran, are engaging with cultural products that promote secularism, such as fashion, music, literature, and art from various parts of the globe.

Young Iranians, in particular, have access to global music, literature, and films that introduce them to secular ideas and the benefits of secular lifestyles. Globalization accelerates the flow of information and media worldwide, exposing Iranian society to secular concepts and liberal values. This contact can lead individuals to question the established norms and beliefs associated with the Islamic regime. Gaining knowledge and realizing that there are countries with more liberal and freer conditions than Iran prompts many Iranians to challenge the Islamic regime and advocate for a more secular and liberal government. In essence, globalization fosters an awareness of the secular world and its advantages, highlighting how the theocratic regime in Iran falls behind the secular advancements elsewhere.

With the rise of globalization, Iranians now have greater access to information. The advances of the Internet, social media, and various information sources have allowed people in Iran to encounter a broader range of viewpoints. This exposure inspires critical thinking and promotes secular attitudes as individuals are introduced to alternative perspectives that challenge prevailing religious narratives. As noted by Arab and Maleki (2020), “Greater access to the world via the internet, but also through interactions with the global Iranian diaspora over the past 50 years, has generated new communities and forms of religious experience inside the country”. In developed countries like those in Europe and America, the ideals of democracy and liberalism have captured the attention of many Iranians, especially the youth. The concepts of freedom of speech, a free press, and human rights make the modern conditions in developed countries particularly appealing to them. While no one can claim that reformist Iranians desire to become European or American, they seek modernization and greater development. Globalization and its core components—such as freedom, democracy, equality, and secularism—offer potential solutions to the expectations of reformist Iranians (Mir and Khaki 2015, p. 74).

Globalization significantly impacts youth influence. The younger generations, being more engaged with global trends and communications, are likely to adopt secular values. Their interactions on a global scale can ignite a desire for modernity and secularism, often standing in contrast to the conservative views held by the older generations of Iran. The Iranian youth, in particular, are more connected to global values and changes than their predecessors. By observing secular movements and political systems in other countries, these young individuals may feel inspired to advocate for similar changes in their nation, challenging the authority of the Islamic regime. They are increasingly questioning the established norms that restrict their freedoms and lifestyles. Many express a desire to dress, eat, and socialize like their peers worldwide. Furthermore, the lack of freedoms related to speech, writing, and criticism has generated frustration among young people. Seeing the liberties enjoyed by the youth in other parts of the world compels them to push for secular reforms similar to those in developed countries.

Moreover, globalization has significantly increased educational opportunities for students worldwide. It has broadened access to education abroad, allowing students and scholars to experience secular educational systems and ideologies. These experiences can instill more liberal values in returning students, challenging the prevailing Islamic norms that they encountered in their home country. The number of Iranian students studying in the top ten destinations has nearly doubled in four years, rising from 60,000 to 110,000. This surge reflects the inadequacies of the educational system in Iran and the regime’s repression of its youth (Iran International 2024). In 2022, the Iran Migration Observatory reported that Iran ranked 17th globally for students studying abroad. Notably, the top five destinations for these students are Turkey, the United States, Canada, Italy, and Germany. While Turkey is perceived as a relatively Islamist country, the other nations represent more secular and liberal parts of the world. Even though the United States imposes visa restrictions on Iranian applicants, around 11,000 Iranian students are currently enrolled in American universities (Martinez 2024). The primary motivations behind this brain drain include the current political climate and the regime’s oppressive measures. As Nafari et al. noted, “the politicized environment of major public universities in Iran has acted as a stimulus for students to seek an educational atmosphere free from these political and social forces” (Nafari et al. 2017, p. 16).

While the world has become increasingly globalized, Iran has faced numerous international sanctions, particularly from the United States, since 1979. These sanctions have encompassed economic, trade, military, and diplomatic measures. Initially imposed under President Carter, the sanctions were continued and intensified by his successors: Reagan, Clinton, Bush, Obama, Trump, and Biden. The 1979 American Embassy hostage crisis ignited this conflict, while the events of 9/11 and Iran’s nuclear weapon project broadened and legitimized the sanctions. The United States aimed to weaken the Islamic regime by isolating it from the international community. However, the rise of the Internet and technological advancements have inspired reformist Iranians and the youth to demand democratic, liberal, and modern changes. The sanctions failed to create barriers between the developed world and these reformist Iranians. Instead, they inadvertently strengthened the regime, making it more radical, closed-minded, and conservative, as it felt less accountable to the international community. Contrary to the expectations, the isolation from the Western world extended the Islamic Republic of Iran’s existence. While the regime remained local and traditional, reformist Iranians became more globalized and modern. Observing secular movements and political systems in other countries has motivated them to advocate for similar domestic changes, thereby challenging the authority of the Islamic regime (Mir and Khaki 2015, p. 84).

The sanctions also made the developed world more appealing to Iranian women, who were categorized into two groups advocating for reforms: Islamist feminism and secular feminism (Mir and Khaki 2015). Islamist feminism emerged following the Khomeini revolution, while secular feminism has its roots in the Shah’s era. Islamist feminism advocates for the integration of Islamic values with women’s equality to men, asserting that women should be equal to men within an Islamic framework. The Khomeini revolution inspired Islamist feminism to embrace both Islamic and feminist principles, as Khomeini viewed women as carriers of tradition and sought to create ideal Muslim women. He famously stated that “Any nation that has women like the Iranian women will surely be victorious” (Paidar 1997).

Islamic feminists in Iran have called for a change in the discriminatory aspects of the Islamic system. They advocate for legal and social equality with men and have a solid justification for their stance. These feminists emphasize the egalitarian verses found in the Qur’an and hadith (statements by prophets) while also challenging the exclusive interpretation of these texts by male jurisprudents (Mir and Khaki 2015, pp. 82–83).

Secular feminism valued the Shah’s secularism and the secularization of Iranian society, particularly Raza Shah’s ban on wearing the hijab in public spaces. In contrast, they protested against the compulsory hijab mandated by Iran’s Sharia law. According to Article 102 of the Constitution, “women who appear on the street and in public without the prescribed hijab will be condemned to 74 strokes of the lash” (Mir and Khaki 2015). Many Iranian women have lost their jobs for failing to comply with this order. Additionally, schools and universities implemented gender segregation, and women were prohibited from studying in engineering, agriculture, law, and 69 other fields. In 2012, dozens of universities banned women from 77 academic fields, including accounting, chemistry, counseling, education, and engineering (Brumberg 2013). Furthermore, polygamy was reintroduced for men, making divorce increasingly difficult for women.

Moreover, women were also prohibited from participating in and watching men’s sports (Mahdi 2004). These restrictions contributed to the rise of secular feminism in the Islamic Republic. Although secular feminism existed before the 1979 revolution, the Islamic revolution made it more appealing to reformist Iranian women. In this context, secular feminism was seen as a viable option for women who felt repressed and excluded. A notable example is Zahra Rahnavard, who initially supported the Khomeini revolution but later embraced secular feminism (Shalhoub 2019).

As Shalhoub stated:

Zahra Rahnavard represents Islamic women activists who focused on the creation of non-governmental organizations in Iran dedicated to assisting women, who clashed ideologically with conservative traditionalists, and opened communication with secularists to further achieve salience in the concept of women’s roles. Her strategy is explored as one that re-interpreted Islamic texts, and informed women in Iran of the inherent equality of opportunity and justice granted to them by Islam, and Shari’a’s patriarchal manipulation that prevents gender equality.(Shalhoub 2019, p. v-2)

The growing repression, combined with the emergence of secular feminism, culminated in significant developments during the Green Movement of 2019 (Sundquist 2013). This movement united Islamist and secular feminists in their efforts to pressure the theocratic regime for democratic change.

In 2022, the tragic death of Mahsa Amini sparked a new wave of pro-reform and feminist protests. Records indicate that Amini was detained for violating hijab laws and was subsequently tortured by police forces. The killing of this 22-year-old Kurdish Iranian woman provoked significant outrage among Iranian secular and reformist groups, leading them to organize protests against the regime. Major media outlets, including CNN and The New York Times, extensively covered these protests, which garnered international attention and served to motivate further demonstrations. The New York Times described the protests as the most significant in Iran since 2009 (Fassihi 2022). The hashtag #MahsaAmini became one of the most widely used hashtags on Persian Twitter, with the number of tweets and retweets exceeding 80 million (Goli 2024). The global interest and attention contributed to a reciprocal impact on the Mahsa Amini protests, helping to initiate, sustain, and expand them. In response to this outcry, however, the regime intensified its oppressive tactics, effectively silencing protests against the regime and fostering a climate of current fear.

Overall, globalization enhances the integration and exchange of ideas, values, and goods. As a result, it plays a significant role in shaping secular trends in Iran by promoting cultural exchange, improving access to information, and influencing socio-economic factors that encourage a shift toward secularism. Iran has been an Islamic republic since 1979, but it has been a part of the global community since its inception. Consequently, the regime’s efforts to protect the nation and state from global influences have not had the desired effect. As a result, Iran’s pro-secular and pro-reform groups are increasingly turning their attention to the developed world.

4. The Flaws Within the Islamic Regime

Khomeini established an Islamic regime by claiming he could improve Iran compared with the secular rule of the Shah. Over time, as discussed in the literature review, the revolution evolved into a form of clerical despotism, particularly after Khomeini’s death (estebdade ruhani). This change brought about the emergence of various anti-regime factions, most notably defectors from the Islamic regime who identified themselves as secular and reformist. One group among them was called the post-Islamists, who argued that Islam was neither the solution to nor the cause of society’s issues regarding freedom, democracy, and equality. The post-Islamists do not oppose Islam itself; instead, they advocate for the secularization of the Iranian regime, aka a secular rationalization (Pargoo 2021, p. 128).

Contrary to Islamism, it rejects the concept of Islamic state. While religion might play a constructive role in civil society, the state is a secular entity no matter who the statesman is. Islamic state in theory is an oxymoron; in practice it is no less than a clerical oligarchy, a Leviathan, which protects the interests of the ruling class.(Mahdavi 2011, p. 95)

In the early 1990s, these factions were primarily composed of the youth and women. It is important to note that 70% of the Iranian population was under the age of 30.

The post-Islamists began to analyze the power of the Islamic regime in the late 1980s. This group emerged in the aftermath of the Iran–Iraq war and included a variety of ideologies (Rivetti 2013). The end of the war marked the rise of post-Islamic tendencies. The eight-year conflict (1980–1988) did not result in a clear victory but instead incurred significant social and economic costs. Many people blamed Khomeini and his associates for the war’s failures, particularly because Khomeini had rejected a ceasefire, insisting on pushing Iran’s armed forces and economy to their limits. He famously claimed that accepting the ceasefire was “deadlier than swallowing poison” (Brumberg 2013). After the war, a sharp decline in oil prices, a rapid population increase, and ineffective economic policies led to numerous economic problems, including unemployment, inflation, foreign exchange crises, a lack of investment, shortages of schools and housing, the flight of capital and professionals, and the continued influx of peasants into urban slums (Abrahamian 2004, pp. 116–17). From 1996 to 1997, the average monthly income for an Iranian family was 620,000 rials, while the poverty line was set at 1 million rials (Salehi-Isfahani 2017; Mahdavi 2011).

The death of Ayatollah Khomeini in 1989 created a significant power vacuum in Iranian politics. His successor, Sayyed Ali Khamenei, lacked Khomeini’s charisma and had to lean heavily on the authority of velayat-e faqih. The clerical oligarchy adopted a more absolutist interpretation of velayat-e faqih to compensate for the absence of Khomeini’s influential presence. This move was driven by their desire to maintain the power that Khomeini had established. The legacy of Ayatollah Khomeini became the most crucial asset for the clergy to uphold their dominance in Iranian political affairs.

Some prominent figures of the 1979 Iranian revolution, including Mohsen Kadivar, Ahmad Qabel, Ayatollah Hussein Ali Montazeri, Mustafa Tajzadeh, and Mir-Hussein Musavi, rejected the absolutist interpretation of the doctrine of guardianship. Instead, they defended the concept of the nezarat-e faqih, or “supervision of the jurist”, as opposed to the jurist’s absolute guardianship. This group argued that Islam is compatible with democratic values, as it supports equal rights for both men and women, as well as for Muslims and non-Muslims. They further posited that the notion of the jurist’s guardianship lacks both religious and rational foundations. Additionally, this perspective advocated for the separation of Islam and clerical authority from the state, promoting a secular structure for the Iranian government. They criticized the Islamic regime for using religion as a tool to impose an ideology, faction, or group that aligns with its interests.

Mahdavi stated:

However, the dominant ideology of Khomeinism was no longer able to reach the youth, even though they had been raised and educated under the Islamic Republic. They were socioculturally disenchanted, politically disappointed, and economically dissatisfied. The state had failed to create the men and women or the society that Khomeini had envisioned.(Mahdavi 2011, p. 96)

Furthermore, prominent figures known as Islamic leftists from the 1979 revolution, such as Abdolkarim Soroush—who was once Khomeini’s representative during the Cultural Revolution—along with Mojtahed Shabestari and Abbas Abdi, argued that Islam should not be seen as an ideology. They contended that an Islamic political system, as claimed in Iran, was not feasible (Wright 1997; Vahdat 2000; Brumberg 2000). Instead, they advocated for a secular form of governance, asserting that political authority should not possess any religious essence (Arjomand 2009). Additionally, they supported the idea of privatizing Islam and argued that even Shiite messianism does not promote democracy. According to Wright (2010), Soroush believed that “the Islamic faith would be strengthened, not undermined, by distancing political and religious authority”.

The disciples of Neo-Shariati also critiqued the Islamic state and advocated for a secular structure in Iran. They argued that while spiritual democracy can be achieved, religious democracy is impractical (Saffari 2013). They believed that true equality, freedom, and spirituality could only exist if the state adopted a framework of democratic secularism instead of religious governance (Alijani 2011).

The fact that key figures from the Islamic Revolution publicly criticized the Islamic regime and published works expressing their views has encouraged anti-regime groups and strengthened reformist and secularist movements. These individuals mostly held significant positions during and after the 1979 revolution, so their departure from the Islamic regime and their support for the secularization of Iran represented a major break within the regime. This shift has further fueled secularist tendencies. Consequently, the Islamic regime is losing influence, while the push for secularization is gaining momentum.

Following the critical fractures within the Iranian Islamic regime, secular and reformist movements gained traction in Iran, particularly among dissatisfied women and the youth. In 1997, for the first time since the 1979 revolution, a reformist presidential candidate, Mohammad Khatami, won the elections (Boroumand and Boroumand 2000). This marked an important turning point for both the revolutionary and reformist factions. With the Iranian ulema losing their candidate under the Islamic regime, the reformists emerged as the victors in this political contest. Many Iranian women and secular advocates believed that Khatami had been forced to resign from his previous position as Minister of Culture and Islamic Guidance due to his tolerant and open-minded approach toward reformists. Khatami emphasized the need to “free our society from the old mentality of law evasion” and to “replace it with the mentality of the constitution”, which upholds “security, justice, freedom, and participation” (Khātamī 1997). Consequently, he emerged as a prominent figure and was regarded as a crucial supporter of Iran’s secular and reformist movements. In other words, the failures of the Islamic regime and the adverse reaction toward its policies helped to produce a reformist candidate for the Iranian presidency. This also contributed to the growth of secularism in Iran.

5. Iranian Diaspora

As part of globalization, travel has become more manageable, allowing people greater access and opportunities to live abroad. Consequently, the number of Iranians residing in other countries has increased significantly. While there are various reasons for this diaspora, many Iranians choose to live outside their homeland due to pressures from the Iranian regime, as well as the better educational and economic opportunities available abroad. Following the 1979 Islamic Revolution, the Iranian diaspora grew from approximately half a million to over three million by 2019 (Azadi et al. 2020). The countries hosting the most significant number of Iranian migrants today include the United States (32%), Canada (14%), Germany (11%), the United Kingdom (6%), Sweden (5%), and Turkey (5%) (Azadi et al. 2020, p. 9). The diaspora primarily consists of artists, social activists, political dissidents, ethnic and religious minorities, and LGBTQ members. This migration has also contributed to the secular movement within Iran.

Many individuals migrate and seek residency in countries that offer opportunities that are not available in Iran. A significant number of Iranians are attracted to Europe and the United States, enticed by the prospect of a lifestyle that upholds secular values and liberal freedoms. These countries provide a chance for a better life, where personal expression and individual rights are respected and celebrated.

Secular Iranians face repression under the Islamic regime. While they did not experience significant issues during the Shah’s rule, the situation drastically changed with the 1979 Islamic Revolution. The Iranian government has no tolerance for the separation of politics and Islam, as Islam is the primary source of political legitimacy in Iran. Without Islam, the political authority loses credibility and legitimacy in the eyes of the public: it is viewed as the very essence of life. The establishment of the Islamic regime in 1979 prompted many secular Iranians to leave the country for Europe and the United States. By the end of that year, approximately 500,000 Iranians had fled to escape the pressures of the Islamic regime. This group primarily consisted of political dissidents, artists, intellectuals, and skilled workers (Gholami 2016, p. 83).

In addition to secular Iranians, non-Shia, atheist, and Zoroastrian, aka Beh-din, Iranians comprise an important part of the diaspora. They identify themselves as Persian and emphasize the pre-Islamic period and national identity. They have no place for Islam in their identity. Islam is incompatible with their Iranian identity and lifestyle (Gholami 2016, p. 3). However, the Iranian regime is strictly Islamic. So, the nonbeliever Iranians migrate to live free of any religious pressure on their lives. Many even change their names to Western ones to relieve their Islamic background and feel more Western and modern. Moreover, this faction of the diaspora thinks that Islam makes Iranian society underdeveloped and closed, since the authoritarian regime uses Islam to purify its undemocratic, illegitimate, and illegal actions. Though they do not blame Islam itself, Islam is regarded as the source of the regime’s autocratic policies. Islam is perceived as a disease afflicting the Iranian nation. Thus, this segment of the diaspora defends that Iranians cannot be truly free unless they liberate themselves from Islam and all the associated aspects (Gholami 2016, p. 8). This group is not the same as the secular diaspora, since “the goal for these people is not necessarily to ‘be secular’; it is to be free to live as they wish” (Gholami 2016, p. 8). So, they reject Islam and Islamic values not only from politics but also from life.

Many Iranians have also migrated for better educational opportunities and improved economic conditions, forming a distinct part of the Iranian diaspora. This group primarily consists of skilled individuals with varying levels of education. The migration wave began in 1995 and continues to this day. These individuals tend to migrate not only to Europe and the United States but also to modern Asian countries, including Singapore and Japan (Gholami 2016, p. 84). They are drawn to places that offer economic advantages and educational facilities. Ultimately, they seek better education, job prospects, and life opportunities for themselves and their families.

Democracy and the desire for democratic freedoms are the motivating factors that have driven many Iranians to live outside of Iran. The Islamic regime’s intolerance of personal freedoms and democratic rights has motivated these individuals to migrate to more free and liberal parts of the world where they can live as they wish. Human rights violations, gender inequality, censorship, and media control are significant issues that compel these groups to seek a more tolerant and liberated environment.

Lack of democratic institutions (e.g., free and multiparty elections), crackdowns on civil society, the mandatory hijab, pressure on religious minorities, draconian interventions in various aspects of relationships between men and women, and homophobia are some embodiments of this issue.(Azadi et al. 2020, p. 15)

The Iranian diaspora operates outside the reach of the Iranian regime, allowing them complete freedom of expression and lifestyle choices. As a result, they actively promote secularism and secular trends within Iran. They openly criticize the regime and inspire Iranian society to pursue their goals. This freedom encourages many in Iran to advocate for a more secular and liberal government. Most members of the diaspora maintain connections with family and friends still living in Iran, which further contributes to the spread of secularism and progressive ideas. Social networks play a critical role in this dynamic. Globalization has enabled the Iranian diaspora to maintain connections with people in Iran and share secular perspectives through social media platforms. This network has the potential to influence attitudes and behaviors within Iran, creating a ripple effect of new ideas and teachings.

The Iranian diaspora exemplifies the possibility of a more liberal and free lifestyle in democratic countries. Living as they choose is not a utopian dream but rather a feasible reality. This diaspora is a significant representation of secular and liberal Iranians who enjoy greater freedom of expression, choice in dress, and various political views. Their way of life appeals to those still residing in Iran who long for similar opportunities. This phenomenon reflects the transfer of ideas from the outside world to those in Iran. The experiences of the Iranian diaspora illustrate the aspirations of many in Iran, highlighting how society and the regime can evolve towards a more secular, liberal, and democratic existence.

6. Rapid Urbanization

Urbanization refers to the growing proportion of people living in towns and cities. In other words, more individuals reside in large urban areas where social, economic, and cultural conditions differ significantly from those in rural regions. This phenomenon involves extensive social, economic, and cultural transformations. Urbanization is fundamentally intertwined with the modernization of society, shaping communities and driving progress toward a more advanced and dynamic future. Wilson describes this transformation as socialization, which contrasts with the appeal of religion (Wilson 1976). In this process, human relations become more complex and interdependent, leading to the reconfiguration of social roles and institutions. In the context of socialization, Wilson argues that as societies modernize, traditional religious institutions face increasing challenges in maintaining their authority and relevance.

Taylor agrees with Wilson and argues that the emergence of modernity has created a context in which multiple worldviews coexist. This plurality has led to a fragmentation of the plausibility structures that once upheld dominant institutional religions. According to Taylor, in our current secular age, individuals encounter a wide range of beliefs and values, which makes it increasingly difficult for traditional religious frameworks to retain their authority (Taylor 2007). He analyzes how societal shifts—such as the rise of individualism, transformations in the public sphere, and the impact of science—have contributed to a landscape where belief in a singular religious truth is no longer assumed. This pluralism encourages people to question previously accepted certainties, resulting in more personal and diverse engagements with spirituality and morality. Consequently, traditional religions may struggle to resonate in a world where secular perspectives and alternative spiritualties are more widely accepted.

The decline of traditional institutions can be attributed to several factors, including the rise of secular institutions, the growing influence of technology and science, and the increasing emphasis on individualism (Wilson 1976, p. 260). Understanding this concept of socialization is crucial for grasping the dynamics of contemporary religion and its diminishing institutional power in light of evolving social norms and values. It underscores the interplay between societal development and religious affiliation, providing a nuanced view of the ongoing changes in belief systems within modern contexts. Furthermore, the rise of individualism, the impact of technology, and new communication methods can alter how people engage with political systems and ideologies. In this environment, individuals may become more critical of established political structures and seek alternative beliefs or movements that align with their personal experiences and values.

In the context of growing secular trends, urbanization and its conclusions are closely related to the previously explained globalization, regime shortcomings, and the influence of the Iranian diaspora. While urbanization is a byproduct of globalization, it also contributes to the rapidly globalized and modern Iranian society. Urbanization and globalization are interconnected forces that influence the rise of secularism. More urban people embrace more global values, such as the freedom of religion and beliefs. Urbanization drives economic growth and creates job opportunities that are often linked to a modern, globalized economy. Such economic shifts can change values, leading individuals to prioritize economic prosperity and personal freedoms over strict adherence to religious norms. This is likely to encourage an increase in secular inquiries and foster a larger community of pro-secular individuals among Iranians. Additionally, urbanization improves access to media and communication technologies. Exposure to diverse global ideas through the Internet and various media platforms introduces alternative perspectives and encourages secular ideologies.

As urbanization progresses, individuals become increasingly aware of governmental shortcomings by accessing media outlets and communication tools. In urban areas, residents are more likely to respond individually and collectively to these shortcomings rather than accepting the regime’s oppressive measures. Cities often serve as hubs for social movements and activism. With more residents living in proximity, there is an increased potential for collective action on issues such as women’s rights, civil liberties, and human rights, which frequently align with secular principles. Urbanization enhances mass communication and facilitates the global exchange of ideas. In large cities, public spaces promote gatherings and social interactions. Urban environments often attract younger populations who are more inclined to embrace secular ideals influenced by global trends and desire progressive values. Urban areas typically exhibit fewer communal and religious values, leading to greater individualism among their populations.

The Iranian diaspora also plays a crucial role in urbanization; city dwellers have greater opportunities to access and exchange ideas with diaspora members in urban centers. The cultural diversity of the diaspora offers a significant resource for pro-secular Iranians to advocate for their beliefs. This connection often leads urban residents to advocate for the separation of religion and government, while resisting governmental oppression and censorship over their lives. Furthermore, urban areas attract individuals from various ethnic, cultural, and religious backgrounds, fostering a multicultural environment. This diversity can promote the tolerance and acceptance of different ideologies, including secularism.

In short, although urbanization does not automatically lead to secularism, it can create conditions that are conducive to secular values in Iranian society, which counterbalance prevailing religious influences. Urbanization in Iran’s city centers has created a complex landscape that reshapes societal norms, economic structures, and cultural identities. These ongoing changes present challenges and opportunities for the urban Iranian society.

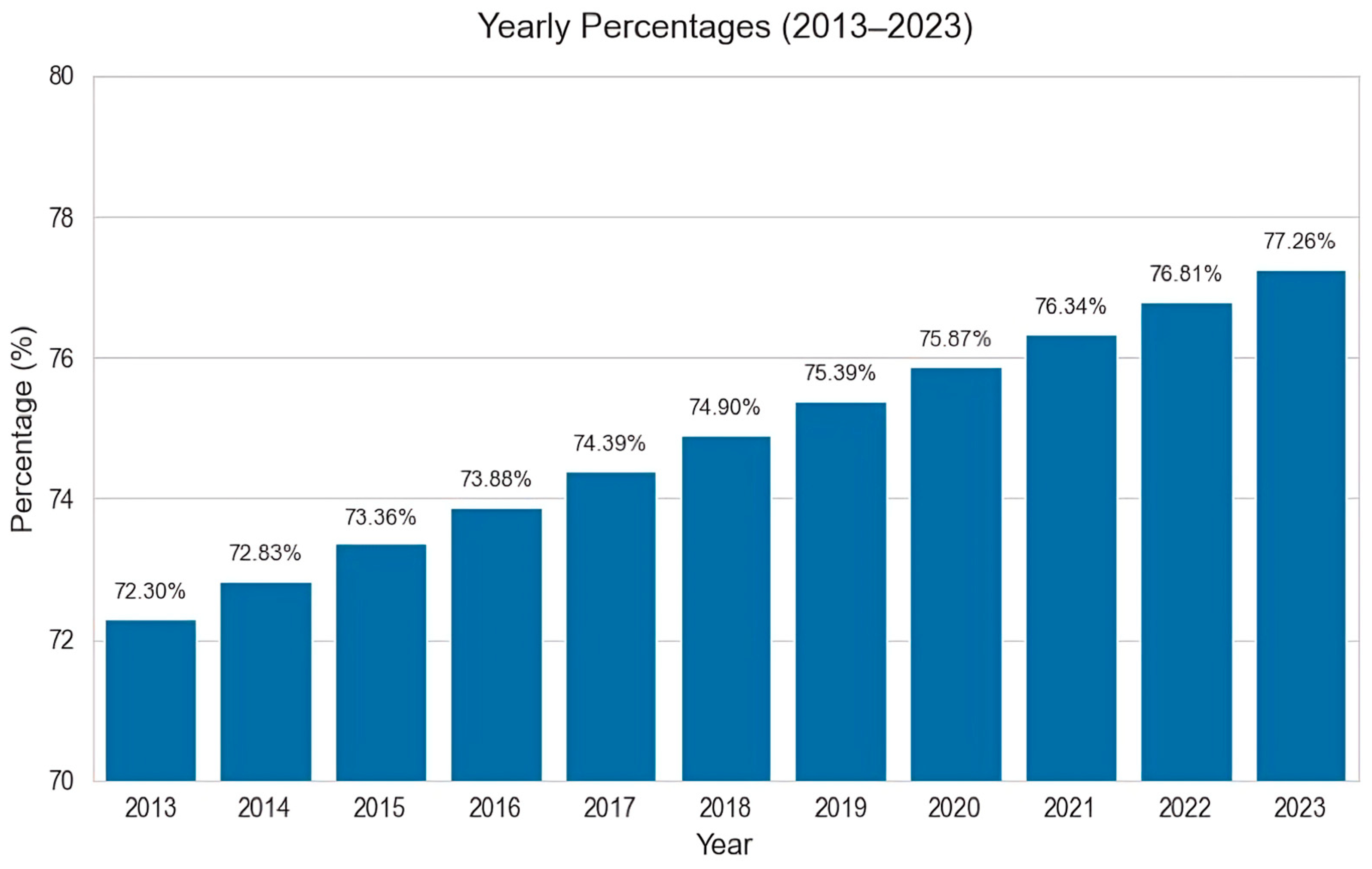

Since the end of the Iran–Iraq war in 1988, Iran has experienced significant population growth and urbanization. The Iranian population increased from 66 million to 90 million in less than 25 years, from 2000 to 2023 (World Health Organization 2025). Similarly, the urban population rose from 41 million to 68 million during the same period (Rojhelati 2024). As shown in Figure 1, the urban population constituted 77% of the total population as of 2023 (World Bank Data 2023). According to Fanni, the pace of urbanization accelerated after the Iran–Iraq war, as “local people moved from war-stricken regions to others, particularly to cities; young men migrated from rural areas to towns and then to cities (pull and push factors); and foreign migrants arrived from countries such as Afghanistan and Iraq” (Fanni 2006, p. 407). Most of the urban population resides in major cities like Isfahan, Shiraz, Tehran, Mashhad, and Tabriz (Shirazi 2013). In summary, by 2023, approximately 68 million out of 91 million people in Iran lived in urban areas. This represents a substantial proportion of the population, which has the potential to influence and shape the trends of Iranian society.

Figure 1.

Urbanization trend in Iran (2013–2023). Source: World Bank Data 2023.

Modern Iran is increasingly at odds with its traditional roots. This shift has been driven by demographic trends reflecting a growing interest among the population in rational theology, as well as secular and liberal values. As Brumberg noted, “Iran’s modernization efforts produced groups which now reject or seek to reform the regime that made their ascent possible. Iran’s expanded middle class-particularly in the urban metropolis of Tehran-is literate, educated and worldly. Middle class Iranians seek legitimate political representation in a system that now limits or denies their participation. They envision a far more democratic system than would likely be tolerated by the regime and its most hardline supporters or ‘principlists’” (2013).

Urbanization often leads to economic growth, improved education, and enhanced access to information and scientific knowledge. These changes contribute to a more secular Iran, as Iranians increasingly focus on scientific and rational explanations rather than religious and traditional ones (Taylor 2007). In other words, the process of rationalization among Iranians is contributing to an increase in secular trends (Mendieta 2014). For instance, the literacy rate has improved significantly due to better access to educational facilities. While the literacy rate was approximately 50% in the early 1980s, it rose to 89% by 2022 (Azadi et al. 2022). As a result of rapid urbanization and the expansion of higher education, Iran was recognized in 1998 as one of the top ten countries in the world for having closed the gender gap in education (Brumberg 2013). By 2023, women comprised 40% of all graduates (Mahdavi 2011, p. 96). This increased access to education can also be attributed to urbanization.

Furthermore, as of 2022, about 82 million people in Iran had access to the Internet, resulting in a penetration rate of 96% (Hashemzadegan and Gholami 2022). Surveys indicated that 73% of the population uses at least one social networking platform, with WhatsApp, Telegram, and Instagram being the most popular (ISPA 2021). Thus, urbanization has not only transformed Iran economically but also digitally. This transformation contrasts sharply with the more limited access to education and information in rural areas, where opportunities for awareness are less prevalent.

Cities often serve as centers of organization, modernization, and individualism. The emphasis on personal achievement and self-expression in urban environments can result in a decline in communal religious activities and a rise in secular values (Hölscher 1995, p. 275). The rapid migration from rural areas to urban centers has also accelerated secular trends. With increased mobility and mass communication in cities, people have greater opportunities to meet and discuss the regime’s repressions and religious restrictions (Vidich and Bensman 1968). While social media platforms have facilitated digital networking and created virtual spaces, cafes and city centers have also played an essential role in this development. Approximately 70% of Iranian adults are members of at least one social media platform (Arab and Maleki 2020). The Green Movement serves as a concrete example of how virtual spaces have enabled people to organize and confront the obstacles posed by the regime (Reisinezhad 2015, p. 2000).

In the words of Cox:

Urbanization constitutes a massive change in the way men live together, and became possible in its contemporary form only with the scientific and technological advances, which sprang from the wreckage of religious world-views. Secularization, an equally epochal movement, marks a change in the way men grasp and understand their life together, and it occurred only when the cosmopolitan confrontations of city living exposed the relativity of the myths and traditions men once thought were unquestionable (2013, p. 1).

Urbanization has led to a cultural shift that prioritizes individualism and personal freedoms, which can clash with Iran’s Islamic regime. Iranians, particularly the youth, are increasingly focused on personal and individual needs, contrasting sharply with traditional expectations and societal pressures. As a result, religious beliefs and practices have become more private matters (Taylor 2007). Urbanization, which transforms sacred cities into secular ones, is emerging as a significant driver of secularization (Cox 2013, p. xxxv).3 Furthermore, technological advancements in urban areas have given rise to a technopolis, which provides residents with access to more liberal and modern influences. This environment encourages individuals to pursue personal freedoms and actively critique the oppressive rules and measures that restrict their autonomy.

Moreover, people from various backgrounds and beliefs have the opportunity to live in close-knit metropolitan cities (Kettell 2019; Wilson 1976). As Mumford (1961) explained, cities, in contrast with the kinship- or blood relation-based social structures of rural areas, offer an environment where strangers can become fellow citizens. In other words, urban settings represent a shift from kinship ties to civic loyalties. This cosmopolitan and diverse social makeup can foster a more secular public sphere where no single religion or religious group dominates. The five major cities serve as hubs for the youth to socialize and exchange ideas, which promotes active citizenship and civic engagement, resulting in increased participation and interaction (Xu 2022).

In large cities, individuals are more likely to engage with secular social networks and institutions, such as professional and volunteer organizations, clubs, coffee shops, and community groups, which can further promote secular values (Bruce 2017). This phenomenon, along with globalization and the Iranian diaspora, has contributed to a rapid increase in urbanization, leading the Iranian youth to focus on modern and developed parts of the world, particularly Europe and the United States. These regions exemplify strong political, social, and economic development, as well as secular governance. Consequently, modernization and secular systems are inherently linked. That is why modern countries are often perceived as secular, or secular nations are viewed as modern.

Economic growth in urban areas can significantly impact the political and legal frameworks that support secularism. For instance, urban populations may advocate for policies that separate religion from state affairs, leading to a more secular governance structure (Sweetman 2021). As a result, greater economic security can diminish the reliance on faith in a higher power to navigate life’s uncertainties, increasing trust in scientific developments that offer empirical explanations rather than religious ones (Habermas 2008). Consequently, the pursuit of knowledge takes precedence over faith. As a result, religion has increasingly become a private matter, rather than a public or political issue.

Urbanization can lead to significant cultural shifts by socialization, particularly with the rise of secularism in public life (Wilson 1976). This shift often changes attitudes toward issues such as marriage, gender equality, and personal freedoms, which are increasingly shaped by secular values (Sweetman 2021). As a result, urban Iranians tend to embrace a more secular culture and its associated features. Consequently, their public and personal lifestyles are often aligned with secular views rather than religious beliefs. This shift is one reason why many reject the repressive measures of the religious regime and express their discontent through protests. Notable examples include the Day of Rage in 2011, My Stealthy Freedom in 2014, the Ahvaz Unrest in 2015, and the Mahsa Amini protests in 2022. Most major protests in contemporary urban Iran have arisen in response to the regime’s oppressive actions, fueled by the mobilization of crowds, a heightened sensitivity to these issues, and the public reaction against repression.

Urbanization has played a significant role in the modernization process by improving access to information, increasing opportunities for social interaction, and raising the overall educational level of the population. Modernization creates environments where secularism and secular ideas can flourish, thanks to the interaction of diverse populations, economic and social changes, and supportive political frameworks. In turn, secular societies tend to modernize further to create a more open, tolerant, and developed environment. Therefore, it can be concluded that while secular societies are often found in urban areas, the conditions and opportunities in these urban settings primarily foster and support secular individuals. This leads to a close relationship between urbanization and trends in secularization (McLeod 2005, p. 9).

7. Conclusions

This paper explores the recent increase in secular trends in Iran, outlining the reasons behind this experience. Firstly, it demonstrates how globalization and its effects have attracted secular Iranians. Secondly, the impact of the weaknesses and flaws of the Islamic regime on secular trends is discussed. Thirdly, the influence of the Iranian diaspora on the secular segments of the population is highlighted. Finally, the paper explains the connection between Iran’s level of urbanization and the rise in secular trends.

As mentioned, the factors contributing to the growing secular trends in Iran are interconnected and not isolated. It is crucial to emphasize that these factors work together to foster a demand for a more secular Iran, aiming to alleviate the regime’s repression and allow for greater self-expression. People increasingly seek more freedom, liberty, women’s rights, and democratization. Secularism serves as an umbrella that unites various opposition groups and reformists against the regime. Protesters want to be recognized as the people as the individuals, not the people as the faithful. As a result, secularism has emerged as a viable pathway to reform the Islamic regime’s orthodoxy. However, despite the rising opposition movements in Iran, the Islamic Republic continues its repressive measures to suppress secular demands. The regime believes that making concessions could lead to further demands that would ultimately threaten its power. Supporters of the regime view opposition groups as puppets of foreign enemies of Iran. Consequently, the regime seeks to stifle any avenues for negotiation or concession.

The international political landscape has shifted in ways that are detrimental to Iran’s interests. Firstly, Iran’s ally, Syrian President Bashar Assad, lost the prolonged proxy war in Syria and fled to Russia in 2024. Secondly, Iran’s other ally, Hezbollah, suffered significant losses in its conflicts against Israel in Lebanon and Palestine. Thirdly, the re-election of American President Donald Trump in 2024 has made Israel more aggressive towards Iran, increasing the likelihood of an attack or harsher sanctions against Iran’s nuclear program. Additionally, Iran’s strong ally, Russia, has begun to weaken due to its isolation by European countries following the invasion of Ukraine and its failure to secure victory in that conflict. Thus, as international dynamics further undermine the Iranian regime, the possibility of reformist or liberal changes within the regime’s conservative framework appears to be increasing.4

Two questions remain to be addressed: How long will the regime be able to withstand international sanctions while maintaining its conservative policies at home? More importantly, can reformists make a meaningful difference in the long run, and if so, how? Brumberg notes, “While we all may hope that such anomalies will one day surrender to a new dawn, we should not be surprised if Iran’s leaders devise solutions that leave the country’s changing political system suspended somewhere between Heaven and Hades” (Brumberg 2000, p. 134).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The difference between secularism and secularization is that secularism is an ideology, while secularization is the process or implementation of this ideology (Cox 2013, p. xx). |

| 2 | While some scholars, such as Asef Bayat, Farhad Khosrokhavar, and Ladan Boroumand, argue that the protests in Iran have lost their momentum, it is important to recognize that the country is still under a religious autocracy. However, all autocratic regimes, including Iran’s, have the potential to evolve toward a less authoritarian governance or even democracy sooner or later. As a result, people often become weary of their autocratic leaders and periodically demand change for various reasons. |

| 3 | The 1979 Khomeini revolution and the Arab Spring serve as prime examples of how cities like Tehran, Tunis, and Cairo play crucial roles in protests and social mobilization. |

| 4 | As an example of the Iranian regime’s vulnerabilities, Iranian President Sayyid Ebrahim Raisi died in a helicopter crash on May 19, 2024, under conditions affected by the climate and atmosphere. Furthermore, Iran’s most influential military figure, Qasem Soleimani, known as the Shadow Commander, was assassinated on 3 January 2020. |

References

- Abdolmohammadi, Pejman. 2015. The Revival of Nationalism and Secularism in Modern Iran. LSE Middle East Centre Paper Series 11: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Abrahamian, Ervand. 2004. Empire Strikes Back: Iran in U.S. Sights. In Inventing the Axis of Evil: The Truth About North Korea, Iran, and Syria. Edited by Bruce Cumings, Ervand Abrahamian and Moshe Ma’oz. New York: New Press, pp. 116–17. [Google Scholar]

- Alijani, Reza. 2011. Pre-secular Iranians in a post-secular age: The death of God, the resurrection of God. Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 31: 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab, Pooyan Tamimi, and Ammar Maleki. 2020. Iran’s Secular Shift: New Survey Reveals Huge Changes in Religious Beliefs, The Conversation.

- Arjomand, Said Amir. 2009. After Khomeini: Iran Under His Successors. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Azadi, Pooya, Matin Mirramezani, and Mohsen B. Mesgaran. 2020. Migration and Brain Drain from Iran. Stanford: Stanford Iran 2040 Project. [Google Scholar]

- Azadi, Pooya, Mohsen B. Mesgaran, and Matin Mirramezani. 2022. The struggle for Development in Iran: The Evolution of Governance, Economy, and Society. Redwood City: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Banchoff, Thomas, ed. 2007. Democracy and the New Religious Pluralism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Batmanghelidj, Esfandyar. 2016. From Tobacco Revolt to Youth Rebellion: A Social History of the Cigarette in Iran. Iranian Studies 49: 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bāmdād, Badr al-Mulūk. 1977. From Darkness into Light: Women’s Emancipation in Iran. Hicksville: Exposition Press. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, Sascha O., Jared Rubin, and Ludger Woessmann. 2024. Religion and growth. Journal of Economic Literature 62: 1094–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boroumand, Ladan, and Roya Boroumand. 2000. Reform at an Impasse. Journal of Democracy 11: 114–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, Steve. 2002. God Is Dead: Secularization in the West. Oxford: Blackwell, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, Steve. 2017. Secularization and Its Consequences. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brumberg, Daniel. 2000. A comparativist’s perspective. Journal of Democracy 11: 129–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumberg, Daniel. 2013. Iran’s Successes and Failures—34 Years Later. February 9. Available online: http://iranprimer.com/discussion/2013/feb/10/iran%E2%80%99s-successes-and-failures-34-years-later (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Chehabi, Houchang E. 2012. The Banning of the Veil and its Consequences. In The Making of Modern Iran. London: Routledge, pp. 193–210. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, Harvey. 2013. The Secular City: Secularization and Urbanization in Theological Perspective. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, Mary. 1982. The effects of modernization on religious change. Daedalus 111: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstadt, Shmuel Noah. 2017. Multiple modernities. In Multiple Modernities. London: Routledge, pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Fanni, Zohreh. 2006. Cities and urbanization in Iran after the Islamic revolution. Cities 23: 407–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassihi, Farnaz. 2022. Protests Erupt in Iranian Cities After Woman’s Death in Custody. The New York Times. September 20. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/20/world/middleeast/iran-protests-mahsa-amini.html (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Fatehrad, Azadeh. 2017. State/religion: Rethinking gender politics in the public sphere in Iran. Parse 6: 134–47. [Google Scholar]

- Gholami, Reza. 2016. Secularism and Identity: Non-Islamiosity in the Iranian Diaspora. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Goli, Maryam. 2024. Digital Echoes of a Movement: Analyzing the Evolution of the WomanLifeFreedom Movement Through Hashtag Analysis. Master’s thesis, University of Nevada, Reno, NV, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, Jürgen. 2008. Notes on post-secular society. New Perspectives Quarterly 25: 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemzadegan, Alireza, and Ali Gholami. 2022. Internet Censorship in Iran: An Inside Look. Journal of Cyberspace Studies 6: 183–204. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, Patrick, and Hossein Dabbagh. 2023. November 6. Available online: https://aeon.co/essays/secularism-in-iran-is-not-just-a-form-of-western-imperialism (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Hölscher, Lucian. 1995. Secularization and urbanization in the nineteenth century: An interpretative model. European Religion in the Age of the Great Cities 1830–1930: 263–88. [Google Scholar]

- Iran International. 2024. Iranian Students Abroad Hits Record High as Hope for Change Fades. December 31. Available online: https://www.iranintl.com/en/202412311687 (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- ISPA. 2021. 73.6 Percent of the Population over 18 Years Using Social Media. February 22. Available online: https://ispa.ir/Default/Details/fa/2282 (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Kettell, Steven. 2019. Secularism and Religion. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. January 25. Available online: https://oxfordre.com/politics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-898 (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Khātamī, Muḥammad. 1997. Hope and Challenge: The Iranian President Speaks. Binghamton: Institute of Global Cultural Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Khomeini, Ayatollah. 1979. Sahife-ye-Noor. Tehran 6: 34. [Google Scholar]

- Kian, Azadeh. 1997. Women and politics in post-islamist Iran: The gender conscious drive to change. British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 24: 75–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmin, Barry Alexander, and Ariela Keysar. 2009. American Religious Identification Survey (ARIS 2008): Summary Report. Hartford: Trinity College. [Google Scholar]

- Kuru, Ahmet T. 2009. A research note on Islam, democracy, and secularism. Insight Turkey 11: 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Mahdavi, Mojtaba. 2011. Post-Islamist Trends in Postrevolutionary Iran. Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 31: 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, Ali Akbar. 2004. The Iranian Women’s Movement: A Century Long Struggle. Muslim World 94: 427–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, Vanessa. 2013. Iran Between Islamic Nationalism and Secularism. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, Alexandre. 2024. Hundreds of Iranian Students and Scholars Are Facing a Visa Backlog. February 28. Available online: https://prismreports.org/2024/02/28/iranian-students-visa-backlog/ (accessed on 23 January 2025).