1. Introduction

Architecture can be interpreted as the physical manifestation of societal values and ideologies (

Rosenbloom 1998). Buildings are often designed and created to meet the needs of society and the people they are supposed to serve. Culture and architectural patterns are closely tied—culture defines societal needs, and needs define the architectural patterns that emerge. Architectures are embodiments of culture (

Lounsbury 2012). As such, architectural patterns can be used to understand the culture; they are considered important evidence for understanding how societies functioned and how they were governed—snapshots of their ways of organized living or governance are evident from historical structures. At the same time, religious texts, as helpful as they may be in understanding the theological aspects of any religion and the lives of the people in question, do not always provide a clear picture of the secular aspects of the lives of the people who practiced the religion. However, religions have always had implications on the secular aspects of societies and their governance—all religions can be “applied” to nature if thought about in a pragmatic sense (

Slater 2014). However, it is known that the term “applied” is used more in Buddhist studies than in other religions; the term was later emphasized as a continuation of the 20th-century movement of engaged Buddhism (

Gleig 2021). Engaged/applied Buddhism gained popularity because, to many, it signified “Buddhist modernism” and a more contemporarily relevant side of Buddhism. More public activities were included in the scope of contemporary Buddhism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by the Buddhist activists and practitioners of the time (

Queen 2012). However, as religious practices and interpretations evolve, revisiting historical contexts provides valuable insights for refining our understanding of religious traditions and texts, which provide us with a holistic understanding of the religion, rather than solely focusing on its modern interpretations and the idiosyncratic aspects of later movements.

This article examines societal governance under religious influence by analyzing architectural evidence from historical periods shaped by a specific religion—in this case, Buddhism. Here, we present cases from two Asian countries—Cambodia and Nepal. In this article, we present notes on the

Dharmasālā of King Jayavarman VII (c. 1122–1218 CE) and the

sattal (also known as

sattra) structure from Licchavi-era Nepal (approx. 450–750 CE), together with some of the contextual underlining beliefs associated with these structures. We compare these structures to the concept of “mote halls”, or

santhāgāra, as evidenced in Buddhist religious scriptures. We use the concept of a “third place” to look at these structures, which are spaces that are neither private homes nor workplaces but places that facilitate broader civic engagement (

Oldenburg and Brissett 1982).

Although our focus is on Buddhism in this article, it has to be noted that both Nepal and Cambodia are places that have experienced a historical interplay between the two great Asian religions—Buddhism and Hinduism. Although Buddhism took dominance in Cambodia in modern times, in Nepal, it was Hinduism that eventually became the major religion. Our analysis of the structures from a Buddhist perspective does not neglect the fact that, in both of these places, Hinduism has had an immense influence in shaping the lives and realities of the people and the spaces they live in. However, our approach is to look at it from the perspective of one religion at a time to identify a clear, religious aspect of the model of idealized living. As

Otto (

1968) claims, “the Holy” is after all universal, and religions that share similar thoughts and are the forces shaping the different societies in a shared geography are not unique but rather expected. Yet, for this analysis, looking through one particular viewpoint, as we do in this article, is not abnormal (see, for example,

Thapa 2001;

Lewis 1996). Approaches such as the one we use are beneficial, as they create a better understanding of this point of view and open up the possibility of research from other points of view as well.

4. The Cambodian Case: Dharmasālā of King Jayavarman VII (c. 1122–1218)

In Cambodia, several terms are used to describe places that serve as almshouses or rest houses. For instance, sālā-samṇak (rest house), sālā-puṇya (merit-making hall), sālā-chhadāna (hall where six items are donated), and dharmasālā (dharma hall) are all similar words to denote structures that could broadly fit under the category of almshouses or rest houses. Although each term serves a slightly different function, they traditionally refer to a rest house, gathering place, or almshouse. To avoid confusion and to align with the title, the term dharmasālā is used throughout this article to refer to those terms collectively, but their meanings and functions are not necessarily limited to dharmasālā alone.

Dharmasālā is a gathering place for Buddhists to engage in various activities, such as taking part in charity, community meetings, hosting festivals, and organizing ceremonies. Dharmasālā was traditionally built by villagers on the roadside as a rest stop for travelers and passersby. Dharmasālā is normally found on either side of the road but never far from the village.

As

Choulean (

2023), a Khmer anthropologist, explained in his article, the construction of rest houses is an old tradition in Cambodia. He pointed out that this tradition became even more important when King Jayavarman VII (c. 1122–1218) came to power.

In the days before Jayavarman VII, the almshouses were known as

agnigraha, which means “fire chamber”. As the name implies,

agnigraha were associated with Brahmin fire worship. Considering the name and purpose of the

agnigraha, one can assume that it is primarily used for religious purposes rather than secular activities. In a first-hand account of the Khmer civilization written by a Chinese envoy who resided in Angkor for a year between 1296 and 1297, the Khmer referred to these resting places as “sen-mu” (Khmer,

samṇak) (

Daguan 1992, p. 65).

Finot (

1925, pp. 421–22) used another Sanskrit word,

dharmaçalas, to interpret these structures since he considered the highways as pilgrimage routes and the buildings beside them as religious hostels. He noted that the reason for considering

dharmaçalas is the presence of Lokeśvara Bodhisattva, which offers protection against dangers, such as brigands, elephants, snakes, and wild beasts. Although the term

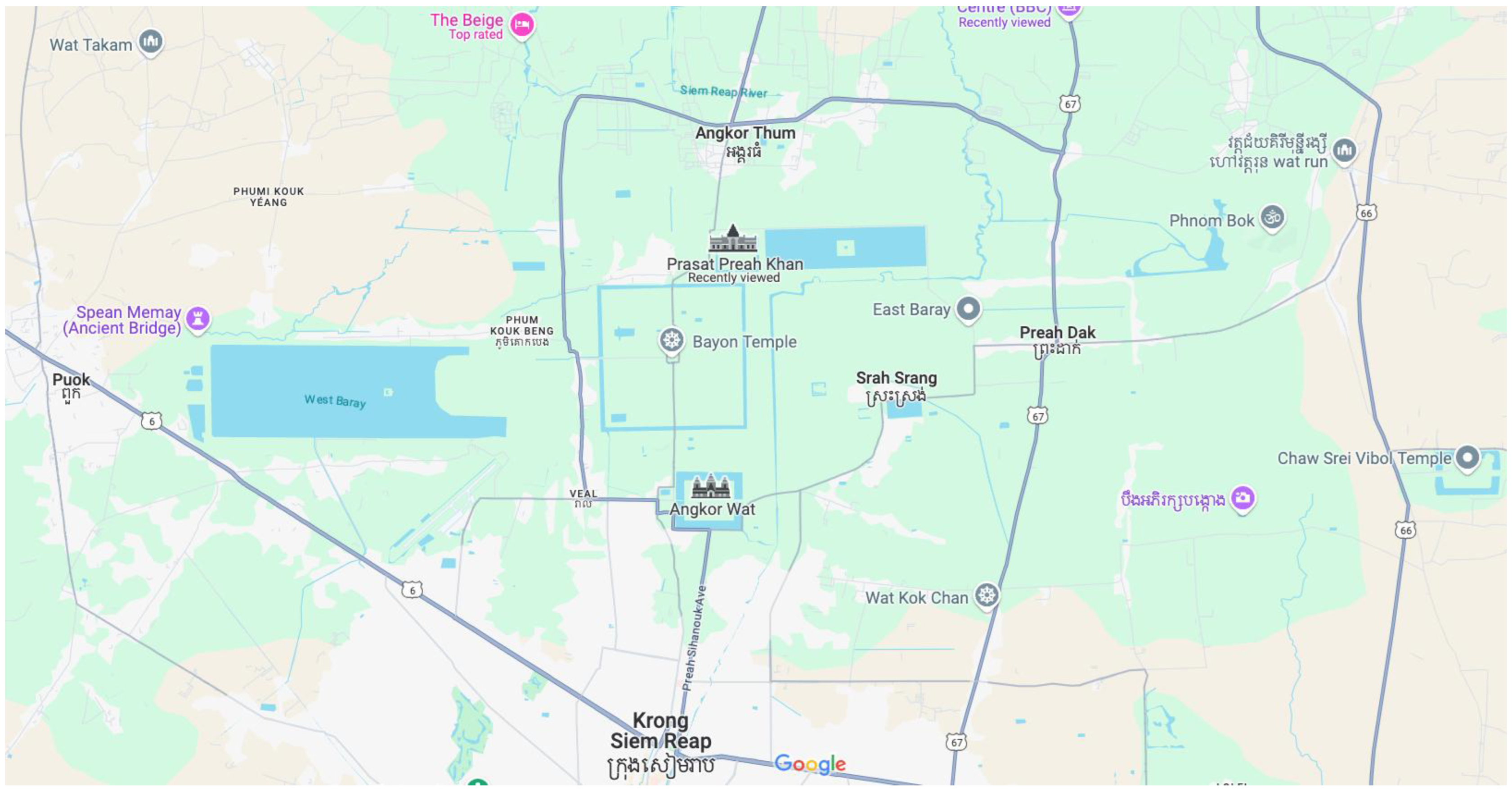

dharmaçala does not appear in the Preah Khan [

Figure 1] inscription, it has since become widely used to refer to these rest houses. English language publications often use the term

dharmasala to refer to the guesthouse structures of Jayavarman VII.

Before Jayavarman VII came to power, Brahmanism was a dominant religion in Cambodia. Several practices, cults, and architectural concepts were influenced by Brahmanism, such as the concept of building temples and the cult of

devarājā or God-king established in the early 9th century by Jayavarman II, founder of the Khmer empire. As soon as Jayavarman VII assumed the throne, he declared himself a Bodhisattva and adopted Buddhism as the state religion. Many Brahmanism cults and traditions were consequently replaced by Buddhism. He applied Buddhist principles to his state policy and adopted the new concept of

buddharājā or

bodhisattva king, looking at himself as “the living Buddha” or “the Buddha-to-be” to govern the state, ultimately leading it to its pinnacle (

San 2024a,

2024b).

There were significant cultural and political transitions during Jayavarman VII’s reign, as he favored Buddhism over Brahmanism. However, elements and terminologies of Brahmanism continued to be used alongside Buddhism in many inscriptions to link the king’s authority to divine power and to portray him as a legitimate savior, capable of alleviating both the physical and mental suffering of his subjects. For instance, in the Preah Khan inscription (

Maxwell 2007, p. 36), Jayavarman VII was compared with Rāma, one of the most popular avatars of Lord Vishnu:

Both Rāma and he (Jayavarman VII) accomplished works for gods and men. Both were primarily devoted to their fathers and both vanquished a descendant of Bhargu (more commonly written as “bhṛgu” or “bhārgava”). However, the former (Rāma) built a causeway of stone across the sea for monkeys, whereas the latter (Jayavarman), built a bridge of gold for men to cross beyond the ocean of rebirths.

The religious principle of Jayavarman VII is based on the spirit of benevolence in Mahayana Buddhism and is expressed as “benefiting others” or “rescuing people”. As stated in the Say-Fong inscription (

Honda 1965), Jayavarman VII puts the well-being of his subjects first:

(Once) a person has a physical disease, his (i.e., his) mental disease is far more painful. For the suffering of people, is the suffering of masters, not (only) the suffering of people (themselves).

During his reign,

dharmasālās were built to serve a variety of purposes, such as community engagement, religious worship, and for travelers and merchants to stay.

As mentioned in verses 122–126 of the inscriptions on Preah Khan stele dated from 1191 CE, we learn that Jayavarman VII built 121 rest houses on the main roads leading from the Angkor capital, Yasodharapura, to distant areas. There were 57 rest houses with fire as staging posts along the road from Yasodharapura to the city of Campā, which is now located in Vietnam, and 17 rest houses along the road from Yasodharapura to Vimāyapura, which is now located in north-east Thailand (

Maxwell 2007, pp. 84–85).

When discussing the

dharmasālā, it is essential to mention the 102

ārogyaśālās, royal-sponsored hospitals, which stand as one of Jayavarman VII’s most remarkable legacies in the establishment of a free healthcare system during his reign. The healthcare infrastructure established under Jayavarman VII has been the subject of extensive scholarly research (

Chhem 2005).

Ārogyaśālā, based on the Say-Fong inscription (

Honda 1965), is available for all four castes. Although Cambodia borrowed the Sanskrit term

varṇas from India to refer to the four castes, identifying different social divisions, it did not carry the same meaning as the Indian caste system, as Cambodia did not have a caste system exactly similar to that of India (

Mabbett 1977).

One might question how we can determine that the

ārogyaśālā were influenced by Buddhism rather than Brahmanism. The evidence supporting this claim is found in the inscriptions of the 102

ārogyaśālā, which record the veneration of Bhaiṣajyaguru, the Healing Buddha or the Master of Medicine in Tantric Mahayana Buddhism (

Honda 1965;

Chhem 2005;

Chhom 2023).

According to the Say-Fong inscription, 98 people were assigned to work and provide free medical care to the people at each

ārogyaśālā. Those 98 people were divided into different groups based on their specializations and skills. Storekeepers distributed remedies, paddy, and wood, whereas two cooks handled food, fuel, water, flowers, and medicinal herbs and were responsible for cleaning the sanctuary. Two sacrificers managed to offer plates, assisted by two men who gathered remedies, fuel, and food. Further, 14 men guarded the hospital and handed out the cures, with a total of 22, including assistants. In addition, there were six women assigned to heat water and ground medicines, plus two who pounded paddy, each with two girl assistants, totaling thirty-two servants. In all, including the assistants, this made a total of 98. The workforce also included two priests and an accountant, appointed by the superior of the holy monastery of the king (

Honda 1965).

The above-mentioned inscription also listed commodities and traditional medicine that were distributed and stored at each

ārogyaśālā for medical treatment, such as a quantity of wax honey, sesame, ghee, rice, gran, jujube juice, butter, nutmeg, garlic, cinnamon, cardamom, dry ginger, mustard, cumin seed, pepper, candle, garment, mantel, clothes, triad of vessels and other local remedies, medical herbs and substances with camphor and sugar (

Honda 1965).

One thing we must not overlook is that the commodities or furnishings provided in the ārogyaśālā are not only traditional medicine but also a variety of food and necessities of life. This indicates that ārogyaśālā was used as a form of relief for the poor as well as medical treatment at that time. Moreover, this demonstrates the Buddhist spirit of benevolence, which was introduced to the king.

Nowadays, little remains of the buildings once used by long-distance travelers. It is only possible to imagine that each structure was made of wood and that multiple buildings existed at each site. However, what has survived is a laterite structure, with sandstone primarily used around doors, windows, and carvings on the towers. One such example is the

dharmasālā at Preah Khan Temple in Siem Reap Province, Cambodia. These structures are long (approximately 17 m × 8 m) and consist of a long hall, or

maṇḍapa, ending with a tower on the western side (see

Figure 2). This tower once housed a statue—most notably of Lokeśvara Bodhisattva—where travelers could worship or pray. Within the prayer hall, there is a fire chamber, which is why it is sometimes referred to as an

agnigraha. The windows typically face the roadway. In addition, where these stone buildings are found, there was often a nearby wooden structure that served as a resting place for travelers staying for a short period.

The functions of dharmasālā have evolved and changed, including its names. The original function of the dharmasālā remains as a small resting place built along the side of the road to provide temporary shelter for travelers. That is why it is called a sālā-samṇak or resting place.

However, in addition to its initial role of serving travelers, the dharmasālā is also used by villagers as a gathering place for community festivals, especially the “village festival”, which usually takes place after the harvest in May. In the Cambodian Buddhist community, this kind of building is often referred to as sālā-puṇya (merit-making hall) or sālā-chhadāna, meaning the six-item-donating hall. The six items provided for travelers are as follows: (1) a sleeping place, (2) a water jar, (3) a toilet, (4) a mosquito net and mattress, (5) pillows, and (6) traditional medicine. Although the above buildings serve many similar purposes in the Cambodian Buddhist community, they also have distinct differences.

Since the building belongs to the community, the villagers or community members take turns caring for it by performing regular maintenance, ensuring cleanliness, and providing necessary supplies for travelers and visitors. They sweep the floors, refill water jars, repair any structural damage, and replace worn-out items with new, functional ones. During festivals or communal gatherings, they also take responsibility for decorating the space, arranging seating, and preparing offerings. This collective effort not only preserves the building’s functionality but also strengthens the sense of community and shared responsibility among the villagers.

5. The Nepalese Case: Sattal from Licchavi Era Kathmandu Valley (450–750 CE)

Among the various aspects of the historical urban settlements of Kathmandu valley, which show influences from Buddhism, the Newar Buddhist monasteries, known locally as

Baha and

Bahi, are well studied (

Gellner 1992;

Locke 1985). Yet another type of Buddhist structure is

sattal or

sattra, which either translates to “rest house” or “almshouse” but also serves a varied set of purposes for the whole town or village it is located in (

Hutt and Gellner 1994;

Slusser and Vajrācārya 1974). Historical records show that such structures came to prominence in the valley largely during the Licchavi era, which is considered to have been approximately at its height between 450 and 750 CE. Though the dates given by most historians on the span of the Licchavi era differ, generally, the dates are accepted. Works of

Hasrat (

1970),

Shaha (

1990), and

Michaels (

2024) also support these dates. Since the dates are not the point here, we do not discuss this at length.

The structures, commonly referred to as

sattal, are also often called

maṇḍapa and may resemble other similar structures such as

phalacā (small resting platforms with a roof, also often called

pāṭī). However, a clear distinction is that they have upper levels, which can be used as storage spaces or for basic amenities for travelers. Describing the general structure of

sattals,

Slusser and Vajrācārya (

1974, p. 179) write that “

sattal is a rectangular, two-story structure, or two and a half if we include the transitional half-story”.

Phalacā structures allow for resting and taking temporary shelter from the rain, but they are not as central or grand in their build as compared to

sattal and often do not have the upper levels.

As a world heritage site, the old towns of Kathmandu valley

1 have several of these structures spread around the historical urban areas. During the 2015 earthquake in Nepal, a total of 37

sattals and 256

pāṭī (

phalacā) were damaged partially or fully requiring reconstruction (

Sharma et al. 2022). The total number of such structures is hard to accurately provide given that some are no longer in their original form and have been subject to encroachments. There have been activities initiated to document such heritage structures

2, but the numbers provided in such documentation cannot be taken to be exhaustive and nor do they claim to be.

A common feature of

sattals is the centrality of these structures within the city planning. They are always located in the vicinity of major squares within the old towns.

Slusser and Vajrācārya (

1974) have mentioned several

sattals such as Ikhālakhu-sattal and Sundhārā-sattal in Patan and Dattātreya in Bhaktapur, all of which are in major squares of the old towns. An even more apparent example of the centrality of the structures within the cities of Kathmandu valley is the four

sattals located at the heart of the old town of Kathmandu

3—Siṃha-sattal, Lakṣmī-Nārāyaṇa, Kavīndrapura, and Kāṣṭhamaṇḍapa. Among the four, the most well known is Kāṣṭhamaṇḍapa

4, which is argued to be the monument through which the name Kathmandu originates (

Rajopadhyaya 2019;

Slusser and Vajrācārya 1974, p. 207). We discuss here more in detail about Kāṣṭhamaṇḍapa as it is the cream of the crop for our purpose to delineate the nature of these structures.

Until Kāṣṭhamaṇḍapa was brought down by the huge earthquake of 2015, it was considered the oldest standing monument in Nepal (

Risal 2015). Although the exact history of the monument conflicts with some sources erroneously dating the establishment of the monument to the 17th century (

Bajracharya and Michaels 2012), clear mention of the monument was already found in a manuscript that was dated 1143 CE (

Risal 2015). With a later archaeological survey conducted after the 2015 earthquake, it was established that the original foundations of the monument already existed by at least 879 CE, with the initial foundation likely laid in the 7th century (

Coningham et al. 2016). Even though the monument was renovated several times, it is claimed that many of the ground plans from the 9th century were retained till 2015 (

Risal 2015;

Slusser and Vajrācārya 1974). Afterward, the reconstruction was completed retaining the original ground plan and the architectural integrity, as seen through sketches by Wolfgang Korn before the earthquake of 2015 (

Korn 1976).

Although there is a shrine to Gorakhnath, a Hindu sage, on the lower level of Kāṣṭhamaṇḍapa, the structure predates Gorakhnath, as it is established that the structure was already constructed in the 7th century. The shrine itself is claimed to have been built in 1465 AD, long after the initial construction of the structure (

Joshi et al. 2021). The mythological accounts suggest that the structure was built by a Buddhist tantric practitioner, Līlāvajra, who is believed to be from the 8th century CE, suggesting Buddhist origins of the structure (ibid.). If the structure was indeed built in the 7th century, it could have been built during the Licchavi period (

Michaels 2024). Although the Licchavi rulers were mostly Hindu, they were also the most important patrons of Buddhism within the Buddhist history of Nepal, with the period under their rule being called the golden age for the growth of Buddhism in Nepal (

Thapa 2001). Regardless of the shared nature of the ownership of Kāṣṭhamaṇḍapa between Hinduism and Buddhism, the structure holds special relevance for the Buddhists of Kathmandu valley.

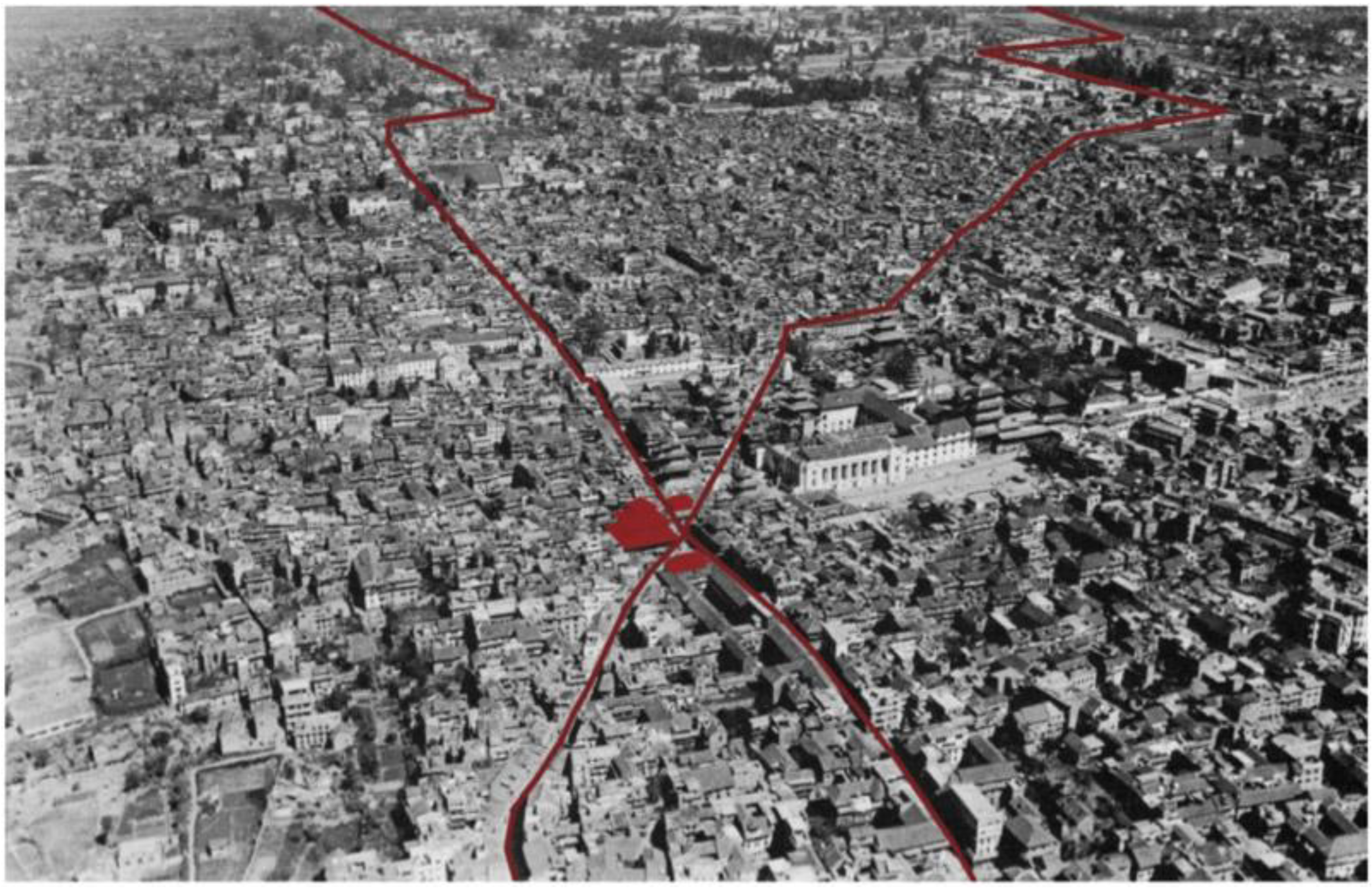

Geographically, Kāṣṭhamaṇḍapa has been suggested to have been built as the central hub between two historical villages, Koligrama and Dakshina Koligrama (later known as Yambu and Yangal), at the cross-section of two major roads in Kathmandu valley (

Rajopadhyaya 2019;

Risal 2015). This has been shown by

Risal (

2015) in a diagram as well, which is presented here in

Figure 3. As noted by

Risal (

2015), a painting by Henry Oldfield from the 1860s shows that the structure and the surrounding vicinity were a major marketplace and a hub for social activities during the mid-1800s.

The structure was built with four 7 m tall center posts, with a base of 18.70 m by 18.73 m. The structure is 16.30 m total in height. The structure has three tiers of tiled roofs. With an open ground floor, which has a porch and four pavilions in each of the four corners, Kāṣṭhamaṇḍapa’s design clearly suggests that it was intended for general public use (

Slusser and Vajrācārya 1974). The cross-section diagram depicted by Wolfgang Korn (1974) is provided in

Figure 4. Although there is evidence that the building was owned by royalty, suggesting that it was a hall built for royal assemblies and other state affairs, the Buddhist elements such as

maṇḍala5 feature in the building, as per the findings of an archaeological survey conducted after the 2015 earthquake (

Coningham et al. 2016). The existing contemporary Buddhist practices such as

pañcadāna, a Buddhist alms-giving function, conducted within the structure, clearly show a more general-purpose nature of the building, accessible to the commoners (

Joshi et al. 2021;

Slusser and Vajrācārya 1974).

The

pañcadāna activity that happens in Kāṣṭhamaṇḍapa is conducted by a

guthi. Guthi is the term that refers to philanthropic community organizations that are associated with most historical structures and religious festivals of Katmandu Valley. They are civic associations that receive large endowments as donations from their founders in the form of arable lands and are tasked with various religious, cultural, and public utility activities, such as maintaining temples, conducting religious rituals, maintaining water sources, conducting cremations, and so on (

Gellner 1992, pp. 221–48;

Toffin 2005;

Shakya and Drechsler 2019). Donations and charity are a central aspect of Buddhist beliefs and practices; it can be seen that such principles are well reflected in the

guthi institution as well.

As with virtually all vernacular structures within Nepal Mandala,

sattals are too associated with one or more

guthis.

Guthis collectively own these structures, using them for their activities while also managing their upkeep. With shrines housed within these spaces,

sattals function as both religious and communal structures, and the associated

guthis frequently engage in both religious and secular activities linked to them (

Risal 2015). Except for the activities conducted within the structure by the several

guthis associated with the structure, other social events were also often conducted in the building. In fact, a blood donation program was conducted in it during the 2015 earthquake when it came down (

Joshi et al. 2021). In most of recent history, it was also a stage for political protests and discussions as much as a venue for cultural and social events.

It was also the community ownership of the building that was emphasized when the structure was brought down during the 2015 earthquake, which prompted the local community to step up to demand reconstruction with the direct involvement of community members (

Lekakis et al. 2018;

Shakya and Drechsler 2019). It was the utmost priority of the local residents that reconstruction be completed with their participation, enabling an egalitarian and bottom-up approach in the reconstruction, where the common people had a voice in the reconstruction process too. This followed the

guthi principle while also adhering to the Buddhist ideals of deliberative practices in making decisions, a practice that was and even is central to the organization of the

saṅgha.

Even though the early reconstruction attempts through direct community ownership of the reconstruction project were thwarted due to the local government wanting to take ownership of the reconstruction project, in the end, due to immense public pressure, the Kathmandu Metropolitan City office had to relent, and the reconstruction was started under a committee comprising local community members but headed by a member of the provincial parliament, Rajesh Shakya (

Shakya and Drechsler 2019). The reconstruction process started with Buddhist

Vajrayana rituals

6 being performed with the entire community getting involved in a celebration (

Joshi et al. 2021). With the reconstruction completed and the rebuilt structure inaugurated, the community will likely get its iconic building back to serve its common purposes as before (

The Rising Nepal 2025). A picture of the reconstructed structure is provided in

Figure 5.

6. Māhā-Umagga-Jataka and Mahosadha’s Great Hall

Mentions of assembly halls are not rare within Buddhist literature as well, with mentions of assembly halls or

santhāgāra among clans of the proto-republic states of Buddhist or pre-Buddhist India (

Gautam 2019, p. 53;

Sarkisyanz 1965, p. 18). Clans, such as the Sākya, the historical Buddha’s clan, Licchavi, Videha, and Malla, all used “town halls” in which they openly discussed matters of state affairs and probably allowed even the non-privileged classes to join in with debates (

Sarkisyanz 1965, pp. 18–19).

The question of how these assembly halls in Buddhist and pre-Buddhist India looked or if they were even remotely similar to the

sattal structures of Kathmandu valley, in structure and positioning within the towns, does remain intriguing. Pursuing this to find more evidence of the same in Buddhist scriptures does not prove fruitful, so we rather turn to the

Jataka scriptures, which, despite not necessarily being historical, can be useful to depict the ideas on various matters such as morality and ethics during the time these

Jatakas were written (

Shaw 2019). A notable mention in Buddhist scriptures of a great hall for use by the general public is Mahosadha’s great hall mentioned in

Māhā-ummagga-jataka, built by Mahosadha, in one of the Buddha’s previous lives (

Cowell and Rouse 1907).

As the story goes in the

Māhā-ummagga-jataka, the

Bodhisatva descends to earth from the heaven of the thirty-three and is reborn as Mahosadha to Sirivaddhaka and his wife Sumanādevī (

Cowell and Rouse 1907). Along with him, on the same day, 1000 other sons are born in the city, all of them also descending from heaven, who become his friends. As the boys grew to a young age, while playing, a rainstorm forced them to run to a nearby house. Seeing that many of his friends fell and bruised their knees, Mahosadha suggested building a great hall where he and his friends could play while being protected from rain and wind. To build this great hall, he asked each of his friends to bring a coin. Through the money collected, he employed a carpenter and instructed him to build a great hall. The hall, as it is built, would have some of the following features (

Cowell and Rouse 1907, p. 156):

one part a place for ordinary strangers, in another a lodging for the destitute, in another a place for the lying-in of destitute women, in another a lodging for stranger Buddhist priests and Brahmins, in another a lodging for other sorts of men, in another place where foreign merchants should stow their goods, and all these apartments had doors opening outside. There also he had a public place erected for sports, and a court of justice, and a hall for religious assemblies.

Once the hall was completed and beautifully painted, Mahosadha further considered that the hall was incomplete and decided to add a tank (pond) with a thousand bends

7 in the bank and a hundred bathing

ghāts (platforms); he also planted trees and created a park. He even established the distribution of alms to holy men. The hall eventually drew in crowds of people, and he discussed right and wrong and passed judgments to petitioners who resorted there (

Cowell and Rouse 1907).

It is clear from Mahosadha’s great hall that the idea of a “town hall” adhering to Buddhist ethics and morals was that of a central hub, where all people, regardless of their status, could gather and use it in common; where holy men and monks could receive alms, traders could stow their goods, and all sorts of people in need could take refuge from the elements. The Jataka tale may not be reasonable to account for the scale and design of the structure descriptively; however, one can take clues from the story to grasp the underlying ideologies behind such a structure, which does compare to sattal structures of Kathmandu valley or the dharmasālā structures from Cambodia.

An infrastructure for common use, the Buddhist idea for a town hall would also function as a community hub with space for various purposes while also being a space for public deliberations, where matters of state could also be discussed, similar to that of the santhāgāra of historical states of proto-republics of the Buddhist and pre-Buddhist era. Moreover, rather than belonging to the monarch, it belonged to the common people, with even the funds to build it potentially collected from the community.

7. Buddhist Governance: Reflecting on the Significance of the “Third Place”

Open public spaces such as Mahosadha’s hall and structures such as

sattal in Kathmandu or

dharmasālā in Cambodia can be taken as “third places”, which are places other than the workplace/school or one’s home where activities involving social interaction can be conducted (

Oldenburg and Brissett 1982;

Oldenburg 1997).

Oldenburg (

1997) asserted the importance of third places showing the concern of the changing urban spaces in the United States, where the attributes of cities and housing were leading to life becoming more privatized, with reduced provisions for community life to foster. This is not an occurrence unique to the United States. In Asian countries such as Cambodia and Nepal, too many open public spaces and third places are rapidly disappearing as newer gated residential areas and mega infrastructure projects are pushed by the government (

Shakya 2020).

Third places help build community life and foster participation in political action as well. While being central to the people in question, third places are not necessarily places of “special” status in the eyes of the people who “appropriate” the places as their own (

Oldenburg and Brissett 1982, p. 270).

Oldenburg and Brissett (

1982) give examples of taverns or bars as the dominant third place in US society. However, they argue that places of business such as businessmen’s clubs and singles’ bars are not effective as “third places” because there is already “an intense devotion to the business at hand” (

Oldenburg and Brissett 1982, p. 269). Rather than having a “purposive association”, a “third place” should rather concern only “pure sociability”, where the people “are expressing their unique sense of individuality are equals as nowhere else” (

Oldenburg and Brissett 1982, p. 271).

The “third place” can be imagined as existing beyond the hierarchy and the relationship dynamics of the conventional social realm; here, positions and statuses are forgotten, and speeches and actions can flow unrestricted. The third place would fall within the “public realm”, which, as conceptualized by

Arendt (

1958, p. 52), is like a table that “gathers us together and yet prevents our falling over each other”. Such places bring us together but also separate us at the same time, keeping us adequately apart so that the individuality of each one of us sitting around a table is maintained.

Arendt (

1958) listed three elements that constitute the human condition, namely, labor, work, and action. Of the three, action, she mentions, is “the only activity that goes on directly between men without the intermediary of things or matter, corresponds to the human condition of plurality” (

Arendt 1958, p. 7). Plurality is, she mentions, “the condition of human action because we are all the same, that is, human, in such a way that nobody is ever the same as anyone else who ever lived, lives, or will live” (

Arendt 1958, p. 8). The

polis represents the public realm in her writing, but the use of

polis in describing her idea of action in a public realm is more metaphorical—she mentions

polis is “the organization of the people as it arises out of acting and speaking together, and its true space lies between people living together for this purpose, no matter where they happen to be” (

Arendt 1958, p. 198).

Structures such as

sattal and

dharmasālā can be looked at from the conceptual framework of “third places” or places of the public realm where people gather to act and speak. Indeed, the various functions, social, religious, or political, that Buddhist “third places” are the venue for deal with organizing activities in the “public realm”. The centrality of open “commons” (

Ostrom 1990) spaces within the Buddhist concept of urban governance represents the significance of such a node within a living space that ties all aspects of lives, where hierarchy and class are extricated, and people, regardless of their individual identities and necessities, converge into a bustling center, from where the vibrancy and liveliness of the city sprout. There have been studies that have highlighted the importance of Buddhist structures within the urban landscape and lifestyle of cities in several Asian regions, for example, in Kathmandu valley (

Pant and Funo 1998) and Bangkok (

Boonjubun et al. 2021).

At the same time, being central to the political lives of the people living in the city, a humble “mote hall” is also, in a way, the space where the collective future of the people is forged through political actions. These third places are often also “almshouses” where the monastic order meets with the laity, not only to receive alms but also to exchange knowledge in a two-way conversation; the

saṅgha are informed of the lay world, and the laity is absorbed in the Dhamma doctrines as orated by the

saṅgha. Foremost, these halls as spaces for merit making are central to the ideology of Buddhism, which emphasizes

dāna, the method of merit making in Buddhism, which can take on various forms, such as teachings of dharma (

dhamma-dāna), charity (

āmisa-dāna), and giving the gift of fearlessness (

abhaya-dāna) (

Bhikkhu Bodhi 2007, p. 305).

Dāna is the first ethical duty of laypeople, the fundamental form of fulfilling the perfection (

pārami) of the Bodhisattva, and the primary principle of

dhammarāja ideal kingship to perform among the 10 roles of

dasavidyarāja-dhamma (

Ngailia et al. 2024). Buddhist structures are designed to facilitate the giving of

dāna by not only the monarch but also the common people. Inclusivity and horizontality in everyday activities in the “public realm” should be taken as a key aspect of Buddhist governance.