Mapping the Growth of the Nones in Spain: Dynamics, Diversity, and the Porous Boundaries of Non-Religion in the Postsecular Age

Abstract

1. Introduction: Rethinking Non-Religion in and from Spain

2. Theoretical Approach to Non-Religion and Objectives of the Article

Phenomena with non-religious characteristics are diverse, and combine with religious, spiritual, and secular characteristics in numerous configurations. They can include forms of anticlerical protest; a- and nontheistic worldviews; the irreligious emotion experienced by someone performing a religious ritual from which they feel alienated; diverse forms of identification which may or may not be combined with other forms of non-religious belief and practice (‘secular humanist’ and ‘spiritual but not religious’ are both examples of non-religious identification, but each combines with different religious, spiritual, and nonreligious practices).

- Within the spectrum of functional or substantive approaches to religion (Giddens and Sutton 2021), the relational and discursive perspective (Cotter 2020) propounds a constructivist lens for exploring religion (Berger and Luckmann 1979). This outlook enables a nuanced understanding of non-religion, unbound by the constraints of a rigid and normative conception of the religious. Consequently, it facilitates an examination of the intricacies of religious and non-religious expressions in contemporary societies from the vantage point of the actors themselves. In this study, a constructivist approach has been adopted. This strategy places the construction of meaning at the center of the methodological inquiry. Furthermore, this methodological view enables the exploration of religion/non-religion within a sociohistorically contextualized framework, acknowledging the variability of meanings in relation to sociohistorical experiences and trajectories.

- Additionally, the relational/discursive perspective facilitates comprehension of non-religion as a religion-related field. This conception has been particularly advanced by Quack and Schuh (2017) based on Bourdieusian theory (see also Blankholm 2022). According to these authors, non-religion constitutes a field that is both external and yet intimately related to the religious (Quack and Schuh 2017, pp. 11–12). It is important to note that the relationship between non-religion and the religious field is not unidirectional; non-religion cannot be reduced to the negation of religion. While acknowledging the presence of a certain dialectical perspective to religion within non-religion, it is crucial to recognize the complexity and diversity of the interactions between religion and non-religion. Non-religion cannot be confined to mere denial of religion; instead, it encompasses a wide spectrum of positions and interactions with the religious that are both dynamic and plural. Research has revealed the multiple non-religious positions towards the religious, but the challenge persists in comprehending this interaction in its multidimensionality (Blankholm 2022, pp. 6–7), which has implications for both the non-religious and the religious fields. Consequently, an approach to non-religion from a field approach must avoid a rigid understanding of the boundaries between the two spaces. As Bourdieu (2000, p. 104) observes, the religious field is undergoing a process of collapse and redefinition in contexts of secularization, giving rise to new agents. It is therefore crucial to acknowledge the multifaceted and sometimes ambiguous relationship between these two fields, which often intersect, resulting in actors of the non-religious sector also engaging in the processes of re-signification and transformation within the religious field.

- Subsequent to the delineation of the theoretical approach (2), the ensuing section will present the research work and the methodology employed (3). Thereafter, the results and the discussion will be articulated in two axes of questions that will guide Section 4: What are the main trends that contribute to the growth of nones in Spain? How do these dynamics shape the reality and identity of non-religious individuals, and how do non-religious individuals, in turn, influence these dynamics? How is the pluralism of nones expressed, particularly regarding different attitudes towards the religious and the spiritual? What is the role of cultural religious/spiritual dimensions in conforming this diversity within the non-religious sector?

3. Researching Non-Religion in Spain: Sources and Methods

- Regional variation, prioritizing the representation of the regions [Comunidades Autónomas] with high non-religious populations, including Madrid, Catalonia, and the Basque Country.

- Socialization trajectory, encompassing both “nonverts” (those who have transitioned from religious to non-religious positions) and “cradle nones” (those raised without religious affiliation), thereby facilitating an examination of potential differences between these groups as highlighted in the extant literature (Bullivant 2022).

- Religious pluralism, incorporating non-religious individuals from religious traditions beyond Catholicism to investigate the growing diversity within the non-religious population. This subsample is being developed in collaboration with Dr. Zakaria Sajir (University of Salamanca, Spain), with whom previous research has been conducted (Ruiz Andrés and Sajir 2023).

- Generational differences, paying close attention to intergenerational variations in non-religious perspectives, considering both the intensity and content of non-religion as identified in previous research (Pérez-Agote 2012).

- Other sociodemographic factors such as gender, the differences between rural and urban areas, social class, and educational level, which significantly shape socioreligious realities.

- Personal trajectory: evolution of the individual’s relationship with religion, including the role of religious socialization, its influence on their life trajectory, and significant religious or non-religious milestones.

- Attitude toward religion: interviewee’s position and assessment of religion, considering its multidimensionality (Glock 1971) and analyzing potential processes of re-signification of religious and spiritual elements.

- Non-religious identity: meaning and significance of non-religious self-identification for the interviewee.

- Secular worldviews: other worldviews and existential cultures (Lee 2015) that shape the interviewee’s non-religious perspective, including their values, ideologies, and identities beyond religion.

4. Discussion: From the Dynamics for Understanding the Growth of Non-Religion in Spain to the Blurred Boundaries Between Religion and Non-Religion

- Gender: predominantly male (45.1%) compared with women (37.1%), exceeding the national average of 40.9%.

- Age: concentrated among younger cohorts, with 58.1% of 18–24-year-olds identifying as non-religious, compared with just 15% of those aged 75 and over.

- Region: highly concentrated in certain regions, notably Catalonia (53.5%), Navarre (47.6%), the Valencian Community (44.4%), the Basque Country (44.3%), and Madrid (44.1%), all exceeding the national average (40.9%).

- Education: More prevalent among individuals with higher levels of education. While 18% of those with no education identify as non-religious, this figure rises to 53% among those with higher education.

- Political vote: more likely to vote for left-wing and regionalist/separatist parties. While only 15% of PP (center-right) voters and 25% of Vox (far-right) voters identify as non-religious, this figure rises to 48.2% among PSOE (social democracy) voters and 83.9% among Sumar (left-wing) voters.

4.1. Three Dynamics for Understanding Non-Religion in Spain

4.1.1. The Expansion of (Superficial) Irreligion

4.1.2. Non-Religion as an Increasing Religious Void (Areligion)?

4.1.3. On the Porous Boundaries Between Religion and Non-Religion: The Hybrid Nones

4.2. Culturally Religious Nones and Spiritual Nones: Two Ideal Types for Exploring the Complex Boundaries Between Religion and Non-Religion

4.2.1. Culturally Religious Nones

- In some cases, like that of Andrés [E1], Catholicism is associated with a broader notion of civilization. From his point of view, the way of life and worldview in countries like Spain are inextricably linked to Catholicism. Although non-religious, he advocates for defending Spain’s Christian character, often opposing the arrival of other religious traditions, such as Islam. In Spain there are platforms and spaces—particularly online—that disseminate this perspective, often based on the concept of “Catholic atheism” by the philosopher Gustavo Bueno (2007)7. This approach aligns with the 37% of Spaniards who, according to Pew Research Center (2018), view Islam as incompatible with Spain’s national values and—as happens in other contexts—this cultural–identitarian vision of religion has potential political implications, coming to the fore in the discourse of the radical right (Joppke 2018; Forlenza 2018).

- Other interviewees acknowledge Catholicism as a fundamental part of their worldview due to its historical and cultural significance in their lives and Spain’s history. These individuals do not adopt an ideological stance, nor do they identify as believers. While they remain critical of the Church, they value Catholicism’s cultural, social, and spiritual contributions to society as can be seen in the testimonies of Francesco [E3] and Jesús [E9].

- Another form of cultural connection is participation in religious events without identifying as religious or holding religious beliefs. This profile aligns with what Zuckerman et al. 2016) call “ritual atheists.” Due to Spain’s history, many traditions and folklore remain deeply tied to Catholicism. Events like pilgrimages and processions, including Holy Week in cities like Seville, serve as both religious rites and total social events (Moreno 2008). Non-religious participants cite cultural, familial, aesthetic, or social reasons for their involvement. For example, José described Holy Week in Andalusia as transcending religion: “It is not only a religious act but also a ceremonial, congregational, social, and artistic act” [E17]. His testimony shows how the mixture between the transversal nature of these events and the subjectivism inherent to the contemporary socioreligious landscape allows each participant to interpret and experience religious rites “in their own way”.

4.2.2. Spiritual Nones

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Reference Code | Name (Anonymized) | Brief Description | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 | Andrés | Male, born in Ciudad Real in 1991. Resident in Madrid (Spain) | 1 November 2023 |

| E2 | Jaime | Male, born in Madrid in 1987. Resident in Madrid (Spain) | 15 November 2023 |

| E3 | Francesco | Male, born in Turin (Italy) in June 1979. Resident in Madrid (Spain) | 22 November 2023 |

| E4 | Wei | Male, born in Madrid in 2000. Resident in Madrid (Spain) | 29 November 2023 |

| E5 | Ainhoa | Female, born in Bilbao in 1991. Resident in Pamplona (Spain) | 5 December 2023 |

| E6 | Teresa | Female, born in Madrid in 2000. Resident in Madrid (Spain) | 8 December 2023 |

| E7 | Carmen | Female, born in Palencia in 1957. Resident in Palencia (Spain) | 16 December 2023 |

| E8 | Joan | Male, born in Tarragona in 1992. Resident in Barcelona (Spain). | 22 December 2023 |

| E9 | Jesús | Male, born in Torrejón de Ardoz in 1999. Resident in Torrejón de Ardoz (Spain). | 15 January 2024 |

| E10 | Rocío | Female, born in a village in Segovia in 1982. Resident in Madrid (Spain) | 25 January 2024 |

| E11 | Luna | Female, born in Sabadell (Barcelona) in 1987. She lives in a village in the province of Barcelona (Spain). | 29 January 2024 |

| E12 | Montse | Female, born in Barcelona in 1989. She lives in a village in Catalonia (Spain). | 26 February 2024 |

| E13 | Nabil | Male, born in Comunidad Valenciana in 1995. He lives in Comunidad Valenciana (Spain). | 19 April 2024 |

| E14 | Tomás | Male, born in Murcia in 1989. Resident in Madrid, (Spain) | 9 October 2024 |

| E15 | Eduardo | Male, born in Valencia in 1950. Resident in Valencia (Spain) | 14 October 2024 |

| E16 | Rubén | Male, born in 1982 in the region of Murcia. Resident in Murcia (Spain) | 24 October 2024 |

| E17 | José | Male, born in Seville in 2002. He lives in a town of the province of Seville (Spain). | 3 December 2024 |

| E18 | Jordi | Male, born in Barcelona in 1947. Resident in Barcelona | 11 December 2024 |

| E19 | Ana | Woman, born in a municipality of Asturias in 1968. Resident in Madrid | 18 December 2024 |

| E20 | Inés | Female, born in Madrid in 2002. Resident in Madrid. | 15 January 2025 |

| E21 | Francesc | Male, born in Barcelona in 1952. Resident in a village in Catalonia | 29 January 2025 |

| E22 | Paula | Female, born in Madrid in 2002. Resident in Madrid. | 4 February 2025 |

Appendix B

| Man | Woman | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Practicing Catholic | 13.8 | 21.5 | 17.8 |

| Non-practicing Catholic | 35.4 | 37.7 | 36.6 |

| Believer of another religion | 3.9 | 2.5 | 3.2 |

| Agnostic (neither denies nor excludes the existence of God) | 14.4 | 10 | 12.1 |

| Indifferent, non-believer | 12.7 | 12.7 | 12.7 |

| Atheist (denies the existence of God) | 18 | 14.4 | 16.1 |

| N.C. | 1.8 | 1.3 | 1.5 |

| (N) | 1938 | 2069 | 4007 |

| Total non-religion | 45.1 | 37.1 | 40.9 |

| 18–24 | 25–34 | 35–44 | 45–54 | 55–64 | 65–74 | 75 y + | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Practicing Catholic | 7.6 | 6.5 | 12.3 | 13.4 | 20 | 21.1 | 42.5 | 17.8 |

| Non-practicing Catholic | 29.7 | 28.1 | 31.6 | 40 | 39.3 | 44 | 39.4 | 36.6 |

| Believer of another religion | 3.9 | 6 | 3.7 | 3.4 | 2.5 | 1.9 | 1 | 3.2 |

| Agnostic (neither denies nor excludes the existence of God) | 20.4 | 13.4 | 12.6 | 12.8 | 12.6 | 10.4 | 5 | 12.1 |

| Indifferent, non-believer | 13.5 | 17.1 | 14.7 | 12.8 | 12.9 | 10.1 | 7.3 | 12.7 |

| Atheist (denies the existence of God) | 24.2 | 27.7 | 23.3 | 16.5 | 10.5 | 10.6 | 3.2 | 16.1 |

| N.C. | 0.8 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 1.1 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 1.5 |

| (N) | 330 | 487 | 686 | 785 | 689 | 511 | 520 | 4007 |

| Total non-religion | 58.1 | 58.2 | 50.6 | 42.1 | 36 | 31.1 | 15.5 | 40.9 |

| Andalucía | Aragon | Asturias (Principality of) | Balears (Illes) | Canary Islands | Cantabria | Castilla-La Mancha | Castilla y León | Catalonia | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Practicing Catholic | 19.2 | 17.1 | 22 | 15.8 | 16.5 | 15.1 | 28.2 | 24.4 | 9.1 | ||

| Non-practicing Catholic | 39.9 | 36.1 | 35.8 | 36.8 | 42.8 | 29.6 | 35.5 | 38.8 | 31.4 | ||

| Believer of another religion | 2.4 | 6.6 | 2.4 | 13.9 | 2.3 | 0 | 4.7 | 0.5 | 4.1 | ||

| Agnostic (neither denies nor excludes the existence of God) | 10.5 | 19.4 | 6.3 | 7.5 | 9.6 | 10.3 | 10.2 | 8 | 16.1 | ||

| Indifferent, non-believer | 11.2 | 9.3 | 15 | 7 | 12.2 | 28.5 | 5.7 | 10.4 | 14.9 | ||

| Atheist (denies the existence of God) | 14.3 | 11.5 | 18 | 17.6 | 15.8 | 13.6 | 11.2 | 17.4 | 22.5 | ||

| N.C. | 2.5 | 0 | 0.4 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 2.8 | 4.5 | 0.4 | 2 | ||

| (N) | 740 | 103 | 89 | 142 | 196 | 58 | 230 | 236 | 561 | ||

| Valencian Community | Extremadura | Galicia | Madrid (Community of) | Murcia (Region of) | Navarra (Comunidad Foral de) | Basque Country | Rioja (La) | Ceuta (Autonomous City of) | Melilla (Autonomous City of) | Total | |

| Practicing Catholic | 14.5 | 27.7 | 14.6 | 15 | 22.2 | 25 | 24.1 | 21.2 | 23.9 | 18.4 | 17.8 |

| Non-practicing Catholic | 37.7 | 38.8 | 40.2 | 37.3 | 33.3 | 22.5 | 29.8 | 42.9 | 21.6 | 39.1 | 36.6 |

| Believer of another religion | 2.7 | 0.5 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 4.7 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 21.1 | 20.9 | 3.2 |

| Agnostic (neither denies nor excludes the existence of God) | 11.3 | 17.1 | 10.2 | 14.2 | 10.5 | 14.7 | 15.8 | 15.9 | 0 | 4 | 12.1 |

| Indifferent, non-believer | 14.9 | 7.2 | 18 | 12.8 | 10.8 | 13.8 | 15 | 11.7 | 29.1 | 10 | 12.7 |

| Atheist (denies the existence of God) | 18.2 | 8.2 | 13 | 17.1 | 17.7 | 19.1 | 13.5 | 7.9 | 4.2 | 7.6 | 16.1 |

| N.C. | 0.7 | 0.6 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 4.1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.5 |

| (N) | 405 | 123 | 261 | 437 | 123 | 60 | 204 | 31 | 4 | 5 | 4007 |

| No Formal Education | Primary | Secondary 1st Stage | Secondary 2nd Stage | F.P. | University | Others | N.C. | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Practicing Catholic | 18.2 | 41.2 | 18.9 | 12.5 | 10 | 15.2 | 0 | 28.2 | 17.8 |

| Non-practicing Catholic | 54.7 | 35.2 | 40.6 | 36.5 | 38.4 | 28.7 | 63.5 | 33.2 | 36.6 |

| Believer of another religion | 5.8 | 2.6 | 3.6 | 2.6 | 4.9 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3.2 |

| Agnostic (neither denies nor excludes the existence of God) | 0 | 7.1 | 10.2 | 15.7 | 11.6 | 16.5 | 0 | 0 | 12.1 |

| Indifferent, non-believer | 15 | 5.5 | 10.2 | 13.6 | 15.4 | 15.2 | 36.5 | 21.1 | 12.7 |

| Atheist (denies the existence of God) | 3 | 4.9 | 15.2 | 18.1 | 18.7 | 21.3 | 0 | 0 | 16.1 |

| N.C. | 3.3 | 3.4 | 1.3 | 1 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0 | 17.5 | 1.5 |

| (N) | 184 | 383 | 1153 | 636 | 535 | 1084 | 11 | 22 | 4007 |

| Total non-religion | 18 | 17.5 | 35.6 | 47.4 | 45.7 | 53 | 40.9 |

| PP | PSOE | VOX | Add | ERC | Junts | EH Bildu | EAJ-PNV | Other Matches | Null+ White | Did Not Vote | No Conditions for Voting | N.R+ N.C. | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Practicing Catholic | 35.3 | 11.1 | 22.1 | 3 | 7 | 16.8 | 0 | 37.6 | 9.8 | 13.1 | 14.1 | 8 | 27.2 | 17.8 |

| Non-practicing Catholic | 47.8 | 37.9 | 46.5 | 11.8 | 36.7 | 33.9 | 17.8 | 28.7 | 28.8 | 34 | 34.1 | 37 | 38.8 | 36.6 |

| Believer of another religion | 0.7 | 2.2 | 5.7 | 1.1 | 0 | 1.8 | 7.3 | 0 | 6.6 | 5.1 | 7.5 | 5.8 | 1.4 | 3.2 |

| Agnostic (neither denies nor excludes the existence of God) | 4.2 | 16 | 7.5 | 19.3 | 19.9 | 11 | 32.4 | 15.7 | 13 | 23 | 10 | 21.3 | 9.3 | 12.1 |

| Indifferent, non-believer | 5.3 | 15.2 | 11.1 | 17.3 | 12.5 | 12.2 | 18 | 9.8 | 14.5 | 10.6 | 16.5 | 7.9 | 10.8 | 12.7 |

| Atheist (denies the existence of God) | 5.5 | 17 | 6.9 | 47.3 | 22.7 | 24.4 | 24.5 | 8.2 | 25.5 | 12.9 | 14.1 | 16.6 | 9.2 | 16.1 |

| N.C. | 1.3 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 1.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 3.8 | 3.5 | 3.4 | 1.5 |

| (N) | 747 | 1036 | 327 | 397 | 46 | 53 | 34 | 27 | 139 | 118 | 643 | 60 | 380 | 4007 |

| Total non-religion | 15 | 48.2 | 25.2 | 83.9 | 55.1 | 47.6 | 74.9 | 33.7 | 53 | 46.5 | 40.6 | 45.8 | 40.9 |

| 1 | Based on Lee’s (2015, p. 85) definition of secularity “as a turn away from religion so that the religious becomes a secondary concern”. |

| 2 | More information on the sociodemographic data of the interviewees can be found in Appendix A. To refer to the content of the interviews throughout the article, I will use the anonymized name and/or interview code that is given in Table A1. |

| 3 | |

| 4 | While in 1998 and 2008 the CIS-ISSP survey allowed the choice of responses “no religion” and “atheist”, in 2017, these were reduced to “no religion”. |

| 5 | Cf. Available online: https://laicismo.org/quienes-somos/ (accessed on 21 January 2025). |

| 6 | In the case of the CIS studies, which constitute a fundamental source for this article, alongside the option “ateo” [atheist], CIS includes the following clarification of the word in the questionnaire: niegan la existencia de Dios [they deny the existence of God]. |

| 7 | It is interesting to note that Gustavo Bueno was honorary president of DENAES [Defensa de la Nación Española, “Defence of the Spanish Nation”], which was founded—among others—by Santiago Abascal, leader of the far-right party Vox in Spain. See https://nacionespanola.org/actualidad/fallece-el-filosofo-gustavo-bueno/ (accessed on 25 January 2025). |

References

- Astor, Avi, Rosa Martínez-Cuadros, and Víctor Albert-Blanco. 2023. Religious representation and performative citizenship: The civic dimensions of Shia lamentation rituals in Barcelona. Social Compass 70: 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez Junco, José. 2001. Mater Dolorosa: La idea de España en el siglo XIX. Madrid: Taurus. [Google Scholar]

- Banham, Rebecca. 2024. Encountering Forests with Purpose: The Role of Routine and Ritual in (a) Nonreligious Practice. Journal for the Academic Study of Religion 37: 339–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaumont, Justin, Klaus Eder, and Eduardo Mendieta. 2020. Reflexive secularization? concepts, processes, and antagonisms of postsecularity. European Journal of Social Theory 23: 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becci, Irene. 2018. Religious Superdiversity and Gray Zones in Public Total Institutions. Journal of Religion in Europe 11: 123–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beider, Nadia. 2023. Religious residue: The impact of childhood religious socialization on the religiosity of nones in France, Germany, Great Britain, and Sweden. The British Journal of Sociology 74: 50–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, Peter. 1967. The Sacred Canopy: Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion. Garden City: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Peter. 2016. Los numerosos altares de la modernidad: En busca de un paradigma para la religión en una época pluralista. Salamanca: Sígueme. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Peter, and Thomas Luckmann. 1979. La construcción social de la realidad. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu. [Google Scholar]

- Beriain, Josetxo. 2012. Tiempos de postsecularidad: Desafíos de pluralismo para la teoría. In Dialécticas de la postsecularidad. Pluralismo y corrientes de secularización. Edited by Ignacio Sánchez de la Yncera and Marta Rodríguez Fouz. Barcelona: Anthropos, pp. 31–92. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer, Peter. 2021. Theoretical and Methodological Background to Understandings of (Non)religion’. In Nonreligious Imaginaries of World Repairing. Edited by Lori G. Beaman and Timothy Stacey. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Blankholm, Joseph. 2022. The Secular Paradox. On the Religiosity of Not Religious. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 2000. Cosas Dichas. Barcelona: Gedisa. [Google Scholar]

- Bravo Vega, Fabián. 2024. ‘No-religión’ y ‘religiosidad liminal’: Propuestas investigativas para el estudio de la desafección religiosa institucional en América Latina. ’Ilu. Revista de Ciencias de Las Religiones 29: e90731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bréchon, Pierre. 2020. Sociologie de l’athéisme et de l’indifférence religieuse. In Indifférence religieuse ou athéisme militant? Penser l’irréligion aujourd’hui. Edited by Pierre Bréchon and Anne-Laure Zwilling. Fontaine: Presses universitaires de Grenoble, pp. 53–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, Steve. 2002. God Is Dead: Secularization in the West. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno, Gustavo. 2007. La fe del ateo: Las verdaderas razones del enfrentamiento de la Iglesia con el gobierno socialista. Madrid: Temas de Hoy. [Google Scholar]

- Bullivant, Stephen. 2022. Nonverts. The Making of Ex-Christian America. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bullivant, Stephen, Miguel Farias, Jonathan Lanman, and Lois Lee. 2019. Understanding Unbelief. Atheists and Agnostics Around the World. Interim Findings from 2019 Research in Brazil, China, Denmark, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Available online: https://kar.kent.ac.uk/78815/ (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Campbell, Colin. 1977. Hacia una sociología de la irreligión. Madrid: Editorial Tecnos. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, José. 1994. Public Religions in the Modern World. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Casula, Mattia. 2015. Between Secularization and Desecularization. What Future does Religion have in a Globalized World? Religioni e Società XXX: 49–61. [Google Scholar]

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS). 1998. Religión (I) (International Social Survey Programme). Estudio 2301. Available online: https://www.cis.es/detalle-ficha-estudio?origen=estudio&idEstudio=1290 (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS). 2000. Barómetro de marzo 2000: Cultura política. Estudio 2387. Available online: https://www.cis.es/es/detalle-ficha-estudio?idEstudio=1375 (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS). 2008. Religión (II) (International Social Survey Programme). Estudio 2776. Available online: https://www.cis.es/detalle-ficha-estudio?origen=estudio&idEstudio=10382 (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS). 2017. Redes sociales I/Religión (III) (International Social Survey Programme). Estudio 3197. Available online: https://www.cis.es/detalle-ficha-estudio?origen=estudio&idEstudio=14366 (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS). 2024. Barómetro de julio de 2024. Estudio 3468. Available online: https://www.cis.es/ca/detalle-ficha-estudio?idEstudio=14828 (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Cordero, Guillermo. 2014. La activación del voto religioso en España (1979–2011). Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas 147: 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo Valle, Mónica, and Maribel Blázquez Rodríguez. 2024. Espiritualidad sin religión: Características de la espiritualidad no afiliada en Madrid. Cuestiones de Pluralismo 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, Christopher R. 2020. The Critical Study of Non-Religion: Discourse, Identification and Locality. London: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Da Costa, Néstor, Gustavo Morello, Hugo Rabbia, and Catalina Romero. 2021. Exploring the Nonaffiliated in South America. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 89: 562–87. [Google Scholar]

- Davie, Grace. 2006. Religion in Europe in the 21st Century: The Factors to Take into Account. European Journal of Sociology 47: 271–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, Abby. 2010. Researching Belief without Asking Religious Questions. Fieldwork in Religion 4: 86–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Cueva, Julio, and Feliciano Montero. 2007. Introducción: Clericalismo y anticlericalismo en la España contemporánea. In La secularización conflictiva en España (1898–1931). Edited by Julio de la Cueva and Feliciano Montero. Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva, pp. 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz de Rada, Vidal, and Javier Gil-Gimeno. 2023. Have the Inhabitants of France, Great Britain, Spain, and the US Been Secularized? An Analysis Comparing the Religious Data in These Countries. Religions 14: 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz Salazar, Rafael. 1994. La religión vacía. Una análisis de la transición religiosa en Occidente. In Formas modernas de religión. Edited by Rafael Díaz-Salazar, Salvador Giner and Fernando Velasco. Madrid: Alianza, pp. 71–114. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz Salazar, Rafael. 2007. España laica: Ciudadanía plural y convivencia nacional. Madrid: Espasa. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, Jennifer, and Venus Evans-Winters. 2022. Introduction to Intersectional Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Forlenza, Rosario. 2018. ‘Abendland in Christian hands’ Religion and populism in contemporary European politics. In Populism and the Crisis of Democracy. Migration, Gender and Religion. Edited by Gregor Fitzi, Juergen Mackert and Bryan Turner. New York: Routledge, vol. 3, pp. 133–49. [Google Scholar]

- Furseth, Inger. 2018. Secularization, Deprivatization, or Religious Complexity? In Religious Complexity in the Public Sphere Comparing Nordic Countries. Edited by Inger Furseth. Cham: Springer, pp. 291–312. [Google Scholar]

- García Martín, Joseba, and Ignacia Perugorría. 2024. Fighting against assisted dying in Spain: Catholic-inspired civic mobilization during the COVID-19 pandemic. Politics and Religion 17: 315–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, Anthony, and Philip W. Sutton. 2021. Sociology. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glock, Charles Y. 1971. Sobre las dimensiones de la religiosidad. In Introducción a la sociología de la religión. Edited by Joachim Matthes. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, pp. 166–88. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, John. 2019. Siete tipos de ateísmo. Madrid: Sexto Piso. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, Jürgen. 2006. Entre naturalismo y religión. Barcelona: Paidós Ibérica. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, Jürgen. 2008. Apostillas sobre una sociedad postsecular. Revista Colombiana de Sociología 31: 169–83. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock, Rosemary. 2024. ‘Lived’ Environmentalism: Lifestyle Politics or Nonreligious Worldview? Journal for the Academic Study of Religion 37: 274–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herranz-de-Rafael, Gonzalo, and Juan S. Fernández-Prados. 2024. Religious Beliefs and Socialization: An Empirical Study on the Transformation of Religiosity in Spain from 1998 to 2018. Religions 15: 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, Ronald F. 2020. Giving Up on God The Global Decline of Religion. Foreign Affairs. August 11. Available online: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/world/2020-08-11/religion-giving-god (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Joppke, Christian Georg. 2018. Culturalizing religion in Western Europe: Patterns and puzzles. Social Compass 65: 234–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kasselstrand, Isabella. 2015. Nonbelievers in the Church: A Study of Cultural Religion in Sweden. Sociology of Religion 76: 275–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latour, Bruno. 1993. Nunca hemos sido modernos: Ensayo de antropología simétrica. Madrid: Debate. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Lois. 2015. Recognizing the Non-Religious: Reimagining the Secular. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Lois. 2016. Non-religion. In The Oxford Handbook of the Study of Religion. Edited by Michael Stausberg and Steven Engler. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 84–94. [Google Scholar]

- Leguina, Joaquín, and Alejandro Macarrón. 2023. Transformación y crisis de la institución matrimonial en España, Observatorio Demográfico/CEU–CEFAS. Available online: https://cefas.ceu.es/wp-content/uploads/Informe-Nupcialidad-Observatorio-Demografico.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Luckmann, Thomas. 1973. La religión invisible: El problema de la religión en la sociedad moderna. Salamanca: Sígueme. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann, Niklas. 2007. La religión de la sociedad. Madrid: Editorial Trotta. [Google Scholar]

- Mauritsen, Anne Lundahl, Jørn Borup, Marie Vejrup Nielsen, and Benjamin Grant Purzycki. 2023. Cultural Religion: Patterns of Contemporary Majority Religion in Denmark. Journal of Contemporary Religion 38: 261–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauss, Armand L. 1969. Dimensions of Religious Defection. Review of Religious Research 10: 128–35. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, Isidoro. 2008. La Semana Santa andaluza como “hecho social total” y marcador cultural: Continuidades, refuncionalizaciones y resignificaciones. In La Semana Santa: Antropología y religión en Latinoamérica. Edited by José Luis Alonso Ponga, David Álvarez Cineira, María Pilar Panero García and Pablo Tirado Marro. Valladolid: Ayuntamiento de Valladolid, pp. 193–205. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, James, Fergal W. Jones, and Dennis Nigbur. 2023. Seeing is Believing: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis of the Experiences of the “Spiritual But Not Religious” in Britain. Secularism and Nonreligion 12: 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarra Ordoño, Andreu. 2019. El ateísmo. La aventura de pensar libremente en España. Madrid: Cátedra. [Google Scholar]

- Observatorio del Pluralismo Religioso en España. 2013. II Encuesta sobre opiniones y actitudes de los españoles ante la dimensión cotidiana de la religiosidad y su gestión pública. Madrid: Observatorio del Pluralismo Religioso en España. Available online: https://observatorioreligion.es/upload/74/95/II_Encuesta_sobre_opiniones_y_actitudes_de_los_espanoles_ante_la_dimension_cotidiana_de_la_religiosidad_y_su_gestion_publica.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Pew Research Center. 2018. Being Christian in Western Europe. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2018/05/29/being-christian-in-western-europe/ (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Pérez-Agote, Alfonso. 2012. Cambio religioso en España: Los avatares de la secularización. Madrid: CIS. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Agote, Alfonso. 2014. The notion of secularization: Drawing the boundaries of its contemporary scientific validity. Current Sociology 62: 886–904. [Google Scholar]

- Portier, Philippe. 2020. Conclusion. Une sociologie de l’arreligion contemporaine. In Indifférence religieuse ou athéisme militant? Penser l’irréligion aujourd’hui. Edited by Pierre Bréchon and Anne-Laure Zwilling. Fontaine: Presses universitaires de Grenoble, pp. 157–69. [Google Scholar]

- Quack, Johannes, and Cora Schuh. 2017. Conceptualising Religious Indifferences in Relation to Religion and Nonreligion. In Religious Indifference. New Perspectives from Studies on Secularization and Nonreligion. Edited by Johannes Quack and Cora Schuh. Cham: Springer, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, Hartmut. 2019. Resonancia. Una sociología de la relación con el mundo. Buenos Aires and Madrid: Katz. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Andrés, Rafael. 2022a. Historical Sociology and Secularisation: The Political Use of ‘Culturalised Religion’ by the Radical Right in Spain. Journal of Historical Sociology 35: 250–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Andrés, Rafael. 2022b. La secularización en España. Rupturas y cambios religiosos desde la sociología histórica. Madrid: Cátedra. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Andrés, Rafael. 2022c. La postsecularización. Un nuevo paradigma en sociología de la religión. Política y Sociedad 59: e72876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Andrés, Rafael. 2024. La no-religión: Una realidad creciente y plural en España. Cuestiones de pluralismo 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Andrés, Rafael, and Zakaria Sajir. 2023. Desinformación e islamofobia en tiempos de infodemia. Un análisis sociológico desde España. Revista Internacional de Sociología 81: e236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajir, Zakaria. 2023. A Post-Secular Approach to Managing Diversity in Liberal Democracies: Exploring the Interplay of Human Rights, Religious Identity, and Inclusive Governance in Western Societies. Religions 14: 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajir, Zakaria, and Rafael Ruiz Andrés, eds. 2025. Religious Diversity in Post Secular Societies Conceptual Foundations, Public Management and Upcoming Prospects. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Salguero, Óscar, and Hutan Hejazi. 2020. El islam en el espacio público madrileño. Disparidades. Revista de Antropología 75: e011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saroglou, Vassilis. 2014. Conclusion: Understanding religion and irreligion. In Religion, Personality, and Social Behavior. Edited by Vassilis Saroglou. New York: Psychology Press, pp. 361–91. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, David. 2020. Interpreting Qualitative Data. London: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Jesse M. 2011. Becoming an Atheist in America: Constructing Identity and Meaning from the Rejection of Theism. Sociology of Religion 72: 215–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taves, Ann. 2020. From religious studies to worldview studies. Religions 50: 137–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Charles. 2014. La era secular. Barcelona: Gedisa, vol. II. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Steven J., Robert Bodgan, and Majorie L. De Vault. 2016. Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods. A Guidebook and Resource. Hoboken: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Thiessen, Joel, and Sarah Wilkins-Laflamme. 2020. None of the Above: Nonreligious Identity in the US and Canada. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Torres Macías, Augusto. 2021. Las organizaciones de descreídos en habla hispana. Balajú. Revista de cultura y comunicación de la Universidad Veracruzana 15: 25–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen, Olivier. 1991. The Secularization Paradigm: A Systematization. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 30: 395–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, Brian S. 2010. Religion in a Post-secular Society. In The New Blackwell Companion to The Sociology of Religion. Edited by Brian S. Turner. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 649–67. [Google Scholar]

- Turpin, Hugh. 2020. Leaving Roman Catholicism. In Handbook of Leaving Religion. Edited by Daniel Enstedt, Göran Larsson and Teemu T. Mantsinen. Leiden: Brill, pp. 186–99. [Google Scholar]

- Uriarte, Luzio. 2017. La “no-religión” y su vivencia. Estudos de Religião 31: 207–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waite, Hannah. 2022. The Nones: Who Are They and What Do They Believe? London: Theos. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Max. 2014. Conceptos sociológicos fundamentales. Madrid: Alianza Editorial. First published 1922. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman, Phil, Luke W. Galen, and Frank Pasquale. 2016. The Nonreligious. Understanding Secular People and Societies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

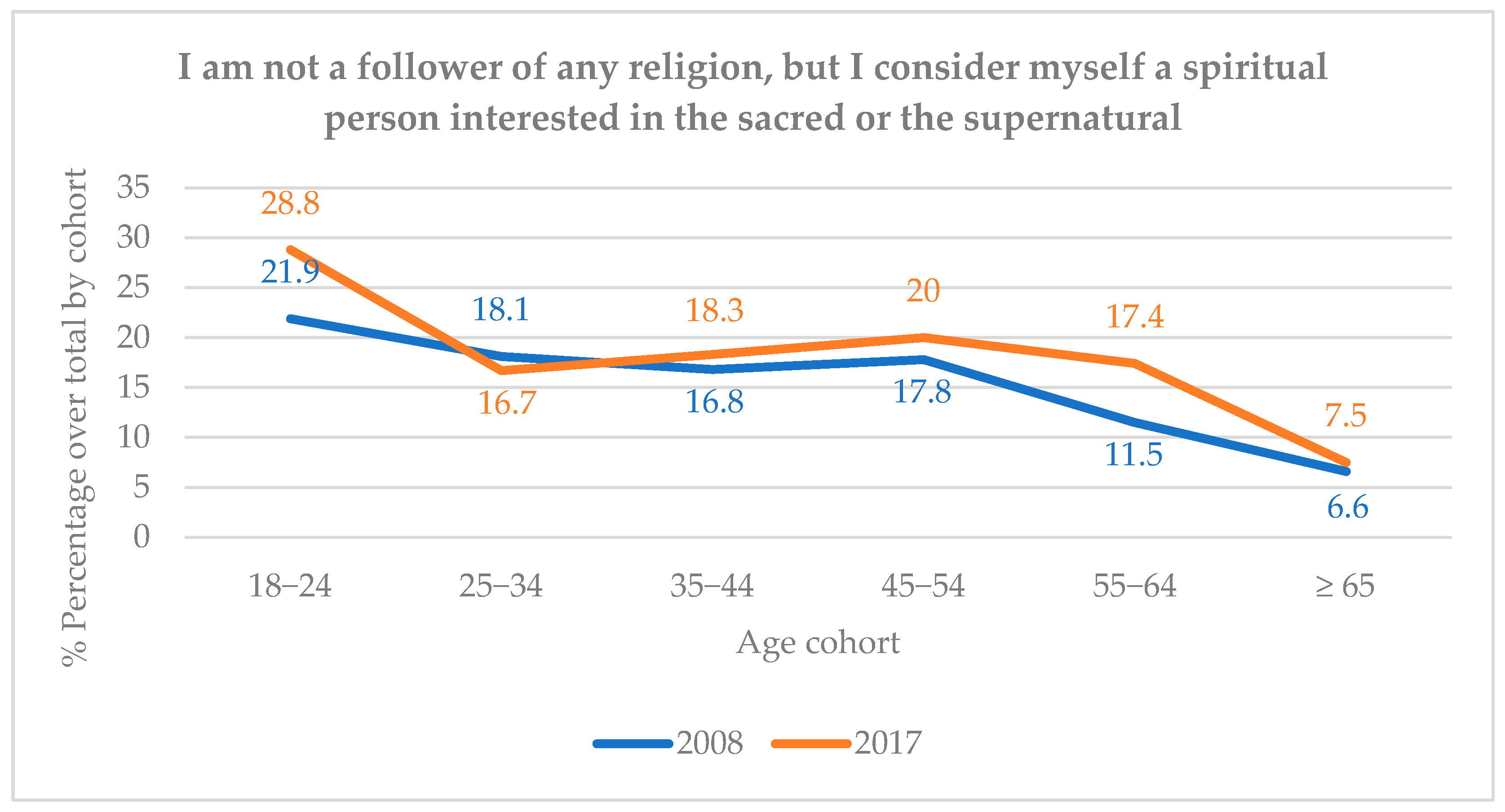

| Definition of Spirituality/Religiosity | 2008 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|

| I am a follower of a religion and I consider myself a spiritual person, interested in the sacred or the supernatural | 20.1 | 15.9 |

| I am a follower of a religion, but I do not consider myself a spiritual person interested in the sacred or the supernatural | 36.2 | 33.1 |

| I am not a follower of any religion, but I consider myself a spiritual person interested in the sacred or the supernatural | 14.7 | 16.8 |

| I am not a follower of any religion and I do not consider myself a spiritual person interested in the sacred or the supernatural | 21.7 | 30.2 |

| I cannot choose | 6.3 | 3.1 |

| NA | 1.1 | 0.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruiz Andrés, R. Mapping the Growth of the Nones in Spain: Dynamics, Diversity, and the Porous Boundaries of Non-Religion in the Postsecular Age. Religions 2025, 16, 417. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16040417

Ruiz Andrés R. Mapping the Growth of the Nones in Spain: Dynamics, Diversity, and the Porous Boundaries of Non-Religion in the Postsecular Age. Religions. 2025; 16(4):417. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16040417

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuiz Andrés, Rafael. 2025. "Mapping the Growth of the Nones in Spain: Dynamics, Diversity, and the Porous Boundaries of Non-Religion in the Postsecular Age" Religions 16, no. 4: 417. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16040417

APA StyleRuiz Andrés, R. (2025). Mapping the Growth of the Nones in Spain: Dynamics, Diversity, and the Porous Boundaries of Non-Religion in the Postsecular Age. Religions, 16(4), 417. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16040417