The Armenian Presence in Vienna: From the Coffeehouse to the Church and Back

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Historical Background

3. The First Coffeehouse in Vienna: An Armenian Success Story

4. The Mekhitarist Monastery: A Cultural Ark

5. The Surp Hripsime Church: A Cultural Hub

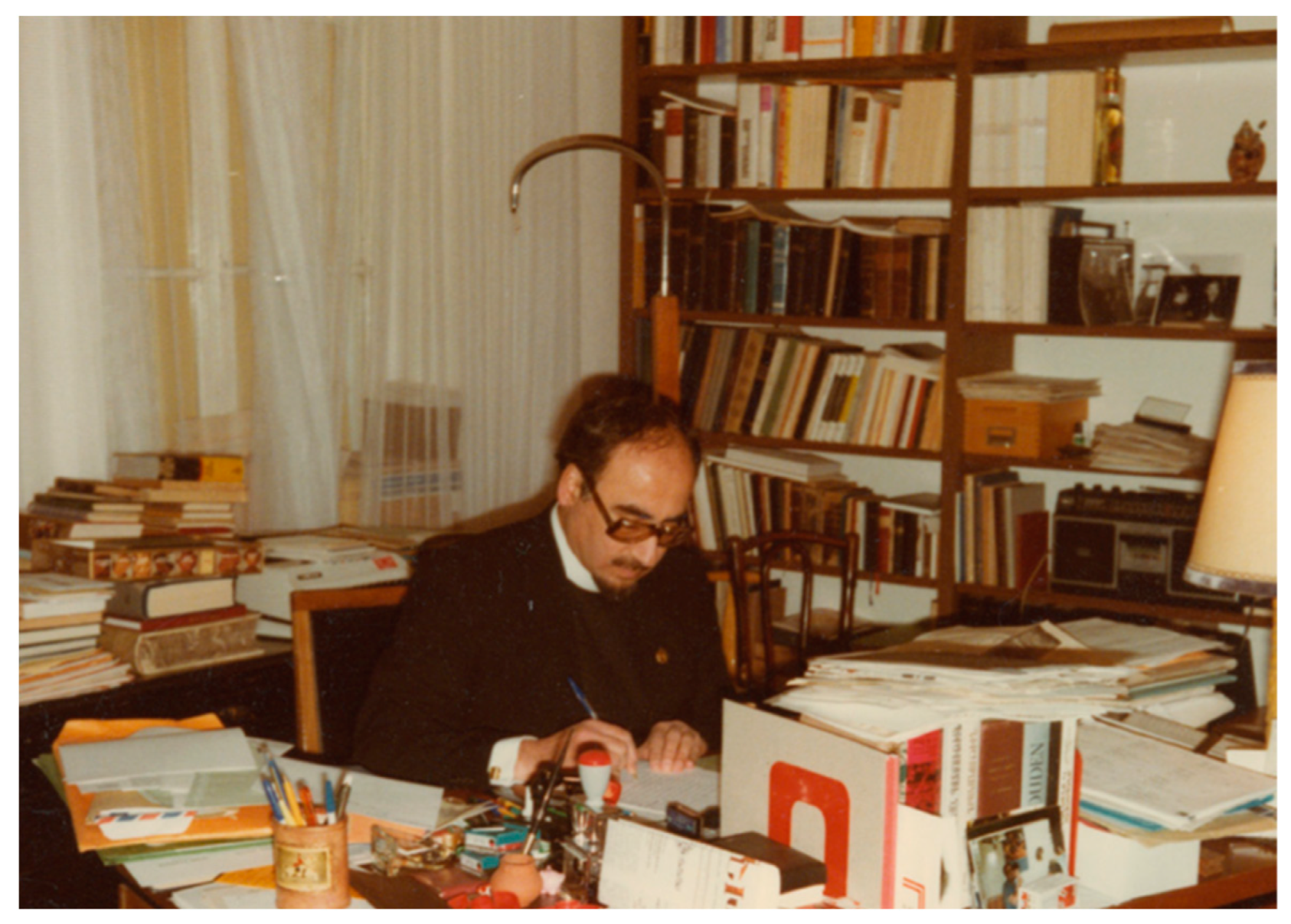

6. Armenian Scholarship: The Legacy of Archbishop Mesrob Krikorian

7. Preserving the Presence: The Legal Framework

8. Epilogue

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The Armenian Genocide, which occurred between 1915 and 1923 during the final years of the Ottoman Empire, involved the systematic mass murder and expulsion of 1.5 million Armenians. It is considered one of the first genocides of the 20th century, marked by atrocities including mass killings, forced deportations, and starvation. Despite widespread historical evidence and recognition by numerous countries and scholars, the Turkish government has consistently denied the characterization of these events as a genocide (cf. Akçam 2007). Τhe Austrian Parliament recognized the Armenian Genocide in 2015, and a memorial, khachkar (խաչքար, cf. Tsivolas 2014, p. 81), dedicated to the Genocide has been placed in the Central Cemetery of Vienna since the 1990s. Apart from raising awareness, this memorial also serves as a significant symbol of the Armenian presence in the Austrian capital. |

| 2 | Nerses converted many Turks to Christianity through his knowledge of the Turkish language and baptized them. His reputation grew further when he translated secret letters from Gabriel, an Armenian from Tokat observing Turkish military positions in Budapest, from Armenian into German in 1686. Gabriel’s adventurous life story, handwritten and preserved in the Vienna National Library (Cod. Arm. 21), tells of his marriage to a Turkish noblewoman in Erseküjvar/Neuhäusel. When the Austrians captured the city on 12 September 1685, Gabriel and his family were taken prisoner. However, he managed to escape, sending his wife and two daughters to Vienna. Gabriel followed and arrived in the imperial capital on 1 October. His family was baptized, and he received the sacrament of marriage in St. Stephen’s Cathedral on 15 January 1686. His friend, Johannes Diodatο (see below Chapter 3), became the godfather of his two daughters. Although the elder daughter was only eight years old, she married the imperial customs officer. Perhaps on an official secret mission, Gabriel returned to Hungary, scouted Turkish military positions in Budapest, and sent his reports in Armenian letters to Vienna. These letters are preserved in the State Archives of Vienna in the Turkish Department, Carton 152/April–December 1683. Vardapet Nerses translated the secret letters and was appointed as titular court chaplain on 16 January 1687, ordinary court chaplain in 1692, and canon of St. Stephen’s Cathedral in 1701. |

| 3 | In 1974 the Österreichisch–Armenische Kulturgesellschaft (Austrian–Armenian Cultural Society, ÖAK) was founded to promote Armenian culture and foster connections between Austria and Armenia. Its activities include cultural events, publications, and supporting academic research on Armenian history, culture, and heritage. The ÖAK has played a key role in preserving the cultural identity of the Armenian diaspora in Austria, organizing exhibitions, concerts, and conferences related to Armenian arts, religion, and the history of Armenians in Central Europe (see https://oeak.org, accessed on 28 October 2024). Moreover, there are numerous NGOs and associations in Austria, including the General Armenian Benevolent Union/Austria Branch [Allgemeinen Armenischen Wohltätigkeitsverein/Zweig Österreich] (est. 1910/1960), the Armenian Students’ Association of Austria [Armenische Studentenvereinigung Österreich] (est. 1921/1960), the Armenia Fund Austrian Committee [Armenien Fond Österreich-Komitee] (est. 1992), the Armenian General Sports and Scouting Club Vienna [Armenischen Allgemeinen Sport-und Pfadfinder Verein Wien] (est. 1989), and the Armenian Sports Club Ararat (est. 1983/2009). |

| 4 | Johannes Diodato, born in 1648, was granted a privilege in 1685 to sell “oriental beverages”, including coffee, tea, and sherbet, marking the beginning of the Viennese coffeehouse tradition (Teply 1980, p. 104; Krikorian 1981, p. 189). |

| 5 | An extensive catalogue of rare Armenian newspapers is available online, via the Mekhitarist Congregation Library, at https://mechitaristlibrary.org/catalog_newspapers/ (accessed on 28 October 2024). |

| 6 | Since October 2011 the “Viennese Coffee House Culture” is listed as “Intangible Cultural Heritage” in the Austrian inventory of the “National Agency for the Intangible Cultural Heritage”, a part of UNESCO; the recognition of Vienna’s coffeehouses by UNESCO underscores their historical and cultural significance. In 2004, with the support of the Vienna City Hall, a park in the 4th district of Vienna was named Johannes-Diodato-Park in honor of Hovhannes/Johannes Astouatzatur, the founder of the first Viennese coffeehouse. |

| 7 | The following is from the congregation’s official website: “In a narrow lane in the seventh district of Vienna a fine view is revealed. On top of the main door of a long building one sees acoat of arms crowned by a bishop’s mitre. It adornes the gate of the Mekhitarist Monastery. For 200 years these Armenian monks have been devoted to the preservation of the Armenian heritage. Thus the Monastery has grown into a unique centre of Armenian spiritual and cultural tradition” (https://mechitharisten.org/history-of-the-congregation/ (accessed on 28 October 2024). |

| 8 | The Mekhitarist Library collection includes over 2500 Armenian manuscripts and approximately 150,000 printed books, many of which are rare and invaluable for researchers studying Armenian history, theology, and culture. |

| 9 | Oshagan, Vahe (1997). Modern Armenian Literature and Intellectual History from 1700 to 1915. in Hovannisian, Richard. The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times, Vol. II. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 157. |

| 10 | In Armenian Սուրբ, meaning Saint. |

| 11 | On 28 June 1964, the cornerstone for the Armenian Apostolic Church “Surp Hripsime” in Vienna was laid at the Armenian Church Association’s building on 11 Kolonitzgasse; a bilingual certificate (Armenian and German) was buried beneath the cornerstone. The construction was overseen by His Holiness Vasken I, Catholicos of All Armenians, and the church was consecrated on 21 April 1968 by His Holiness Vasken I in the presence of distinguished guests. The solemn consecration was performed by Vardapet (at the time) Mesrob Krikorian. |

| 12 | Until the construction of the church, the Armenian community held its religious services in a temporary chapel located in an apartment at Dominikanerbastei 10. See (Tragut 1995, p. 11). |

| 13 | The story of Hripsime’s martyrdom in the third century, after she refused to renounce her Christian beliefs in the face of persecution, has long been an inspiration to Armenian Christians. |

| 14 | Etchmiadzin, Armenia, is home to one of the oldest churches in the world, the Etchmiadzin Cathedral, which is also a UNESCO World Heritage Site. This cathedral, dating back to the fourth century, is significant not only for its historical and architectural value but also as the center of the Armenian Apostolic Church. The site, including the cathedral and surrounding churches, illustrates the evolution of Armenian ecclesiastical architecture, particularly the central-domed cross-hall type of church that influenced much of the region’s architectural development. For more information, see https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1011/ (accessed on 28 October 2024). |

| 15 | In the center, the saint is shown as life-sized and is holding a cross in her right hand. The Holy Spirit is represented as a dove descending onto St. Hripsime’s head from heaven. Beneath her feet lies King Tiridates IV (also known as the Great, reigning from 298 to 330), who, according to an ancient legend, sought to marry the humble saint. Surrounding them are depictions of the martyrdom of St. Hripsime and her 38 companions (all Christians, led by a superior named Gayane). After Hripsime refused the king’s marriage proposal, he ordered the execution of all the innocent Christians. Tiridates later became mentally ill, and after being healed by Gregory the Illuminator (known as Գրիգոր Լուսաւորիչ [Krikor Lusavorich]), he released Gregory from prison. Eventually, Tiridates III declared Christianity as the state religion (in 301 AD), making Armenia the first officially Christian nation in the world. |

| 16 | Op. cit., fn. 1. |

| 17 | Avetis Aharonian (1866–1948) was a prominent Armenian politician, writer, and revolutionary. A leading figure in the Armenian national liberation movement, he played a crucial role in advocating for Armenian independence during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As the head of the Armenian delegation to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, Aharonian worked to secure international recognition for the Republic of Armenia. He was also a prolific author, contributing to Armenian literature with poetry, plays, and political writings that highlighted Armenian identity and struggles. |

| 18 | The monument, in addition to being a space of remembrance, has served as a focal point for annual memorial services on 24 April, the official day of remembrance for the Armenian Genocide. It has been visited by prominent figures such as Catholicos Karekin I and representatives of both the Armenian and Austrian governments, further cementing its role as an important cultural and historical site. |

| 19 | “The Armenian Apostolic Church holds services on Sundays and is thus also a very important social center since besides providing a place for celebrating the ritual mass together, it also offers a community room where people gather afterwards. It is a place for social exchange, for new arrivals to start building their network, for youth to meet dates arranged by their parents, or simply a place for having coffee with Armenian sweets” Paredes Grijalva (2017, p. 88). |

| 20 | Over the next several years, he held numerous teaching positions, including lecturing on Armenian history, ancient Armenian, and bibliography at the seminary. His deep knowledge and passion for Armenian history and literature were evident as he took on roles such as deputy director of the seminary’s library and head of the printing house. During this period, he also completed his Archimandrite thesis on the manuscripts of Antelias, a monumental work that earned him a doctoral degree in 1956. The following decades saw Archbishop Mesrob’s scholarly output flourish, including the publication of six comprehensive volumes of religious textbooks between 1955 and 1956, covering topics such as the history of the Holy Book and the history of the Armenian Church. |

| 21 | The Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, established in 1956, is a philanthropic institution based in Lisbon, Portugal. It was created according to the wishes of Calouste Sarkis Gulbenkian, a wealthy Armenian businessman and philanthropist. The foundation promotes arts, education, science, and charitable projects, with a particular focus on fostering Armenian heritage. It operates the Gulbenkian Museum, which houses an extensive collection of art, and provides grants and scholarships worldwide, contributing to both cultural and social causes. A notable project supported by the foundation is the digitization of the Mekhitarist Library. To date, the online library of the Mekhitarist press and its corresponding databases have been endowed with more than 400,000 pages of digitized Armenian newspapers and periodicals from the rich collection of the Mekhitarist Monastery of Vienna. The digitization of these materials and making them available to the public has been made possible through the collaboration between the Mekhitarist Congregation, the Armenian Communities Department of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, and the Fundamental Scientific Library of the National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia (see https://gulbenkian.pt/armenian-communities/2022/01/28/the-press-collection-of-the-mekhitarist-library-is-now-online/ accessed on 28 October 2024). |

| 22 | Kirkorian, M. (1963) The participation of the Armenian community in Ottoman public life in Eastern Anatolia and Syria, 1860–1908, Durham theses, Durham University. It is available online at Durham E-Theses: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/8124/ (accessed on 28 October 2024). The dissertation was later published as Krikorian M. (1977). Armenians in the service of the Ottoman Empire 1860–1908. London: Routledge. |

| 23 | Pro Oriente is a church foundation established on 4 November 1964, by Cardinal Franz König, the Archbishop of Vienna. The foundation was created during the Second Vatican Council with the goal of fostering dialogue and improving relationships between the Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox churches, which have been historically separated (see https://www.pro-oriente.at/en/about-us, accessed on 28 October 2024). |

| 24 | Franz König (1905–2004) was an influential Austrian cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church. He served as the Archbishop of Vienna from 1956 to 1985 and was one of the most prominent Catholic leaders in Austria during the 20th century. Also, he played a significant role in Vatican II (1962–1965), the ecumenical council that brought many reforms to the Catholic Church, including greater openness to other Christian denominations and world religions. König was known for his advocacy of human rights, his efforts to promote dialogue between different religions, and his support for religious freedom in Eastern Europe, especially during the Cold War. As a key figure in the Catholic Church’s post-World War II revival, he contributed to Austria’s religious and social development and was deeply respected for his diplomatic and ecumenical work. König was also close to Archbishop Mesrob, with whom he worked to strengthen the relationship between the Catholic Church and the Armenian Apostolic Church, as well as foster ties with the Armenian community in Austria. He was named a cardinal by Pope Paul VI in 1958 and remained active in church affairs until his retirement in the mid-1980s. |

| 25 | On 16 February 1998, the Association of Austrian Armenian Studies (ÖASG) was founded to promote Armenian studies in Austria through public lectures and academic symposiums. From its inception until 2010, Archbishop Mesrob served as chairman, continuing as deputy chairman until his passing in 2017; he was succeeded by Prof. Dr. Werner Seibt (b. 1942). The ÖASG collaborates with the Institute of Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies at the University of Vienna, organizing significant events such as the 1999 Symposium on the Christianization of the Caucasus and the 2005 symposium on Caucasian alphabets, with published proceedings by the Austrian Academy of Sciences Press (for further information, see https://www.byzneo.univie.ac.at/en/about-us/associations-and-societies/accociation-of-austrian-armenian-studies/ accessed on 28 October 2024). |

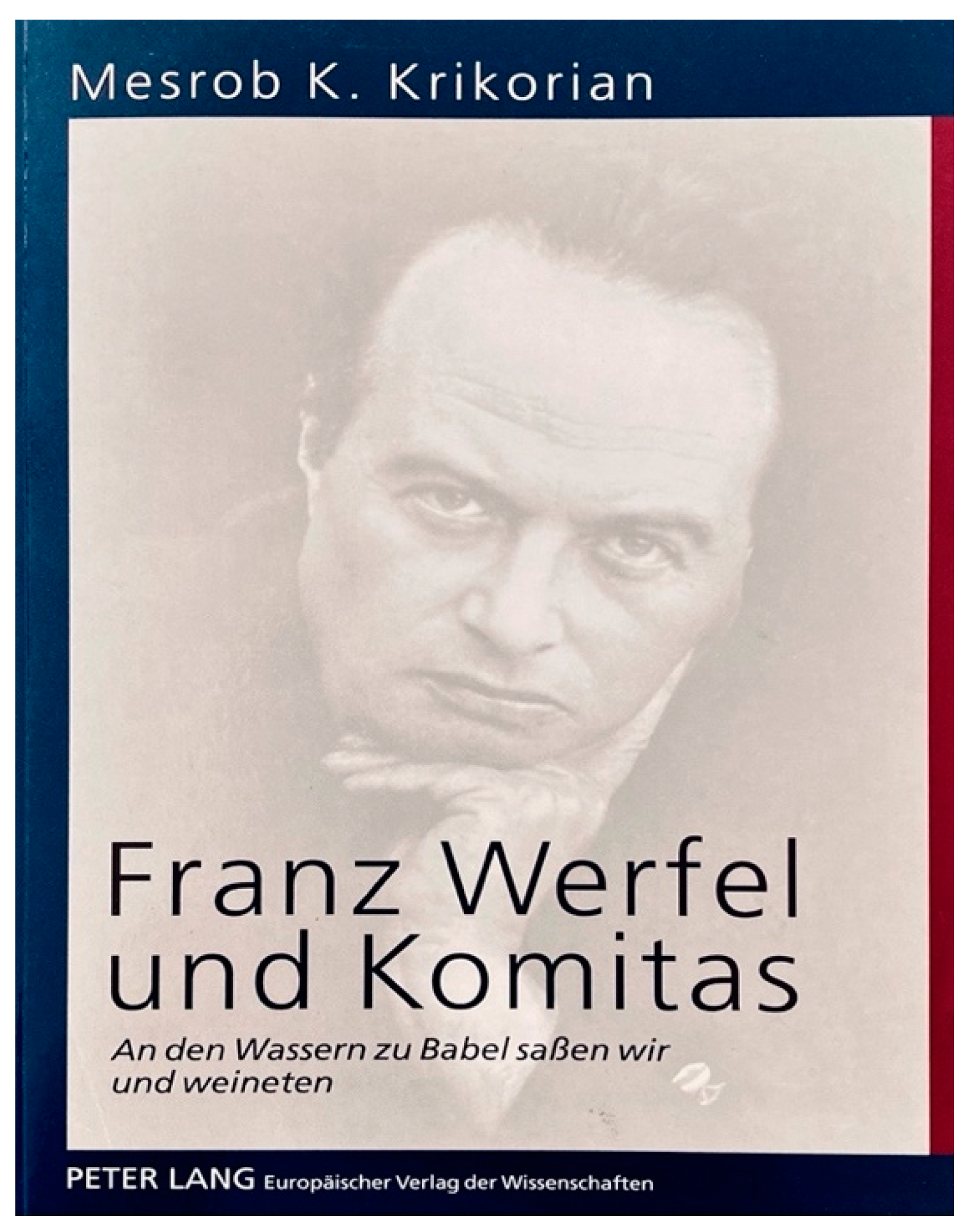

| 26 | In addition to his academic work, Archbishop Mesrob published numerous books and articles, including a study on Franz Werfel and Komitas in 1999 (see Figure 11), which explored the legacy of the Armenian Genocide, while his 2003 publication, The Armenian Church, further solidified his reputation as a scholar of both Armenian theology and history. His contributions to the Matenadaran series, particularly on Armenian medieval literature and historiography, are widely respected in the academic world (cf. Kirschläger and Stirnemann 1992). |

| 27 | An extensive book is currently being prepared by Zaven Krikorian (b. 1941), the brother of Archbishop Mesrob. Zaven Krikorian is a notable writer, journalist, and educator residing in Greece, and his latest project aims to detail the biography and works of Revered Archbishop Mesrob, offering a comprehensive look into his life, academic contributions, and spiritual leadership. Through this work, the legacy of Archbishop Mesrob will be meticulously chronicled, shedding light on his influence within both the Armenian Church and the academic world, particularly his role in relation to the Armenian diaspora in Vienna. |

| 28 | The monument was designed by architect Roland Martirosyan and crafted by sculptor Vahan Petrosyan. Franz Werfel (1890–1945) is renowned for his novel The Forty Days of Musa Dagh (1933), which brought international attention to the plight of Armenians during the 1915 genocide. |

| 29 | Komitas (1869–1935), born Սողոմոն Սողոմոնեան [Soghomon Soghomonian], was a pioneering Armenian composer, ethnomusicologist, and priest whose work played a crucial role in the revival of Armenian folk music and choral music in the early 20th century, leaving a lasting legacy in the realm of Armenian cultural heritage. |

| 30 | The diverse array of the international conventions, declarations, recommendations, policies, and guidelines makes abundantly clear that there are two basic (although in many cases overlapping) types of religious cultural elements, whether functional or not, that is, tangible and intangible. Although the international instruments protecting cultural heritage initially focused primarily on the former, such protection has now been frequently extended also to the latter (Tsivolas 2014, p. 79 f.). |

| 31 | St. George’s Brotherhood was founded between 1723 and 1726 by Greek Orthodox merchants from the Ottoman Empire. In 1802, George Karayiannis purchased the house that today houses the Church of St. George. In 1776, Empress Maria Theresia granted the brotherhood special privileges, which were later reaffirmed by Emperor Joseph II in 1782 and his successors. By 1766, 134 Ottoman citizens were involved in commerce in Vienna, 82 of whom were Greek. During the 18th and 19th centuries, the majority of Viennese Greeks came from the regions of Epirus, Macedonia, and Thessaly. A short walk down the alley of “Griechengasse” leads to the Church of the Holy Trinity. The community of Holy Trinity was granted imperial privileges in 1787 and was founded by Greek Orthodox members who had acquired citizenship in the Habsburg Empire. A major renovation of the building took place between 1857 and 1859, based on designs by Theophil Hansen and funded by Simon Sinas. The Church of St. George was also restored in 1898.The Greek Orthodox community of Holy Trinity established a Greek school in 1801, and on 6 May 1804, Emperor Franz I granted the school “public law status” (Öffentlichkeitsrecht) (cf. Koimzoglu 1912). Today, the school is still located in its original premises, on the first floor above the Church of the Holy Trinity. The Metropolis of Austria has been situated in the same building since 1963. |

| 32 | See above “Historical Background”, § 2. It was not until December 1912 that an Armenian chapel for church services was founded, which was set up in the attic of a house at Dominikanerbastei 10. Τhanks to the initiatives and efforts of Archbishop Mesrob, the resources necessary for the St. Hripsime church’s construction were successfully secured. |

| 33 | Federal Law 229/23.6.1967 (published in issue number 54 of the Government Gazette) regarding the recognition of the Holy Metropolis of Austria as a legal entity under public law. |

| 34 | Verordnung des Bundesministers für Unterricht und Kunst vom 12. Dezember 1972 betreffend die Anerkennung der Anhänger der Armenisch-apostolischen Kirche in Österreich als Religionsgesellschaft aufgrund des § 2 des Gesetzes vom 20. Mai 1874 RGBI Nr. 68 (published in the Government Gazette on 5 January 1973). In Austria, the recognition of religious communities is governed by the Austrian Federal Law on the Recognition of Religious Societies (Anerkennung der Religionsgesellschaften Gesetz), which was enacted in 1874 and later amended. This law provides a legal framework for the official recognition of religious communities, granting them rights and privileges, such as tax exemptions, the right to own property, and the ability to perform certain religious ceremonies. To be officially recognized, a religious group must meet certain criteria, including a minimum number of adherents and the establishment of a formal organization. |

| 35 | See, for instance, the 2003 UNESCO Convention on the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, which covers the religious “practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills—as well as the instruments, objects, artefacts and cultural spaces associated therewith”, which religious communities and groups recognize as part of their cultural heritage. UNESCO had already launched the ‘Living Human Treasures Systems’ in 1993 and the ‘Proclamation of Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity’ in 1998. In the framework of the latter, member states were free to submit candidates to this list of masterpieces, and an international jury was created to review and approve such proposals. |

References

- Akçam, Taner. 2007. A Shameful Act: The Armenian Genocide and the Question of Turkish Responsibility. London: Constable. [Google Scholar]

- Arat, Mari Kristin. 1990. Die Wiener Mechitharisten: Armenische Mönche in der Diaspora. Koeln: Bohlau Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Heckel, Martin. 1968. Staat, Kirche, Kunst: Rechtsfragen kirchlicher Kulturdenkmäler. Tübingen: Mohr. [Google Scholar]

- Inglisian, Vahan. 1961. 150 Jahre Mechitharisten in Wien. Wien: Mechitaristen-Congregation. [Google Scholar]

- Kalb, Herbert, Richard Potz, and Brigitte Schinkele. 2003. Religionsrecht. Wien: WUV Universitätsverlag. [Google Scholar]

- Kirschläger, Rudolf, and Alfred Stirnemann. 1992. Chalzedon und di Folgen. Festschrift 60. Geburtstag von Bischof Mesrob K. Krikorian. Wien: Tyrolia Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Koimzoglu, Michel. 1912. Geschichte der Griech-Orientalischen Kirchengemeinde “zum hl. Georg” in Wien. Wien: Buchdruckerei Artur Stern. [Google Scholar]

- Krikorian, Mersob. 1981. Die Armenier in Österreich. In Pro Oriente, Veritati in caritate. Der Beitrag des Kardinals zum Ökumenismus. Innsbruck: Tyrolia Verlag, pp. 188–97. [Google Scholar]

- Krikorian, Mesrob K. 2007. Die Armenische Kirche, Materialien zur armenischen Geschichte, Theologie und Kultur. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Lehner, Erich, and Artem Ohandjanian. 2004. Die Baukunst Armeniens. Christliche Kultur an der Schwelle des Abendlandes. Wien: Institut für Vergleichende Architekturforschung. [Google Scholar]

- Link, Olaf. 2011. Geschichte(n) Wiener Kaffeehäuser. Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, Benny, and Dror Ze’evi. 2019. The Thirty-Year Genocide. Turkey’s Destruction of Its Christian Minorities, 1894–1924. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paredes Grijalva, Daniela. 2017. Caring for the homeland from a distance: The Armenian diaspora in Vienna and transnational engagements. In Migration and its Impact on Armenia. Edited by Gabriele Rasuly-Paleczek and Maria Six-Hohenbalken. Vienna: Department for Social and Cultural Anthropology, pp. 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Pοtz, Richard. 2009. Religious freedom and the concept of law and religion in Austria. In Human Dimension Implementation Meeting. Warsaw: Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Scherer, Franz. 1890. Die Mechitharisten in Wien: Mit einer kurzen Skizze über armenische Sprache und Literatur. Wien: F. Scherer’s Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Stoye, John. 2007. The Siege of Vienna. New York: Pegasus Books. [Google Scholar]

- Strzygowski, Josef, and Thoros Thoramanian. 1918. Die Baukunst der Armenier und Europa. Wien: Kunstverlag Anton Schroll & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Suny, Ronald Grigor. 2015. A History of the Armenian Genocide. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Teply, Karl. 1980. Die Einführung des Kaffees in Wien. Georg Franz Kolschitzky, Johannes Diodato, Isaak de Luca. Wien: Kommissionsverlag Jugend und Volk Wien-Munchen. [Google Scholar]

- Tragut, Jasmin. 1995. Armenier in Österreich. Graz: Universitätsbibliothek. Available online: https://unipub.uni-graz.at/download/pdf/2749111.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Tsivolas, Theodosios. 2014. Law and Religious Cultural Heritage in Europe. Heidelberg and New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Wieshaider, Wolfgang. 2002. Denkmalschutzrecht: Eine systematische Darstellung für die österreichische Praxis. Wien and New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsivolas, T.; Krikorian, A. The Armenian Presence in Vienna: From the Coffeehouse to the Church and Back. Religions 2025, 16, 379. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16030379

Tsivolas T, Krikorian A. The Armenian Presence in Vienna: From the Coffeehouse to the Church and Back. Religions. 2025; 16(3):379. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16030379

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsivolas, Theodosios, and Ani Krikorian. 2025. "The Armenian Presence in Vienna: From the Coffeehouse to the Church and Back" Religions 16, no. 3: 379. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16030379

APA StyleTsivolas, T., & Krikorian, A. (2025). The Armenian Presence in Vienna: From the Coffeehouse to the Church and Back. Religions, 16(3), 379. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16030379