Abstract

Religious places represent one of the most significant categories of protected heritage. In Italy, however, places of worship belonging to minority communities often remain inconspicuous and are not legally recognized as part of the nation’s cultural heritage. Consequently, the histories of these communities face challenges in securing a space within the collective memory. This contribution, through a spatial approach and an interdisciplinary methodology, highlights the richness of the hidden heritage—both tangible and intangible—of the Greek Orthodox Church of the Nativity of St. John the Baptist in Turin. In particular, this research explores the role of the Greek language, which constitutes a significant element of intangible heritage for the community. Since the 1960s, regular celebrations in the Byzantine rite and the Greek language have been held in the Piedmontese capital. These biritual practices emerged in response to the demands of numerous Greek university students and families who revitalized the Orthodox presence in the territory during those years. In 2000, the Catholic Archdiocese granted the Greek Orthodox community the use of a church in the city’s historic center. This church is interpreted as a shared religious space, having undergone a transformation of identity over time: its Orthodox identity remains architecturally invisible, as the community continues to worship in a former Catholic church.

1. Introduction

Building on the proposal outlined in the Introduction of this Special Issue to apply “Spatial Turn” (Knott 2005, 2010a, 2010b) to the study of religious heritage, this article delves into the rich and layered heritage of the Greek Orthodox community’s place of worship in the city of Turin. Through an interdisciplinary approach, it examines the history and geography of a ‘religious place’—the Greek Orthodox Church of the Nativity of St. John the Baptist, located in Turin’s Circoscrizione I district.

This article is the result of a broader research conducted in Turin between 2023 and 2024, during which I carried out six interviews in Italian and conducted fieldwork across three different Orthodox parishes.1 The study focused specifically on the Orthodox churches located in the historic center of the city, examining the places of worship of the Greek, Romanian, and Moldovan Orthodox communities and exploring their settlement strategies, organizational structures, and spatial materialization within the urban fabric. The motivation for this research stemmed from a desire to investigate the relationship between the central location of Orthodox churches in the urban context and their actual visibility within the city’s public space. The findings revealed that legal recognition does not always translate into clear and tangible benefits for these churches, as the visibility and affluence of the different communities are often shaped by other factors. The three churches analyzed share the Orthodox faith and a location in the urban space but differ in the linguistic and national composition of their members, as well as in the level of State recognition they have achieved.

The present article will analyze, as a case study, the tangible and intangible religious heritage of the Greek Orthodox church belonging to the Ecumenical Patriarchate, which is the only one of the three to have obtained legal recognition from the State. This case study was chosen to be analyzed over the others, as it is relevant to understanding whether having legal recognition brings real benefits in terms of preservation and enhancement of tangible and intangible heritage. Furthermore, this case study is particularly significant as the Greek community enjoys dual legal protection for its intangible heritage: the Greek language is safeguarded by law as a “historic minority language”.

This church highlights the crucial role that places of worship of religious minorities play in collecting and preserving both material and immaterial assets. However, the heritage of these communities does not receive adequate protection and valorization from the State, even when it has obtained legal recognition, as demonstrated by the case study analyzed. In particular, this research explores the role of the Greek language, which constitutes a significant element of intangible heritage for the community. The language finds its most intense expression in the space of the church, the site of pre-Gregorian Byzantine chanting classes since 2012 and the place where concerts are organized to celebrate both Orthodox and Greek traditions. Despite the fact that this element is further protected as a “historical linguistic minority”, it demonstrates how legal and formal recognition does not necessarily translate into genuine enhancement. In this context, analyzing cultural heritage becomes essential for understanding the complex processes involved in constructing, preserving, recognizing, and enhancing the diverse memories and social, political, and cultural identities of ethnic, national, and local groups—especially in the context of broader historical and political dynamics.

Following this introduction, Section 2 outlines the theoretical and legal framework, while Section 3 presents the spatial approach and interdisciplinary methodology on which this research is based. Section 4 delves into the historical and geographical trajectory of Orthodox communities in Turin, with a particular focus on the establishment of the city’s first Orthodox places of worship. The aim is to provide an in-depth exploration of the history of Turin’s first Greek community, which settled and localized through migration processes. Turin serves as a unique case study for examining the interplay between religious spatiality, cultural heritage, and plural memory, given its longstanding history of religious “super-diversity” (Vertovec 2007). Section 5 presents findings from a field study on the cultural heritage of the Greek Orthodox Church of the Nativity of St. John the Baptist conducted between 2023 and 2024 in Turin. This research involved semi-structured interviews with the parish priest of the church, as well as informal conversations with worshippers and community members. This section also examines the history of the church, understood as a shared religious place that has undergone a transformation of identity over time. Finally, Section 6 draws conclusions from the field research, emphasizing how this space embodies and expresses both Greek and Orthodox identity, while also highlighting the gap between legal recognition and the lack of enhancement of its cultural and religious heritage.

2. Theoretical and Legal Framework

Religious places are among the most significant forms of protected heritage. However, in Italy, places of worship belonging to minorities often remain both symbolically and materially invisible (Burchardt and Giorda 2021) and are rarely considered as part of the national heritage. As a result, the histories of these communities struggle to find a place within the collective memory. Religious cultural heritage can be defined as the collection of material and immaterial elements that constitute the collective memory of a religious community and are deemed worthy of protection and preservation due to their exceptional value, in terms of social, cultural, and religious significance (Tsivolas 2014, p. 64). However, it is the governments that bear primary responsibility for defining and determining what qualifies as “cultural heritage” within a nation. In many cases, these religious communities are even unable to build new places of worship, leaving their sacred spaces architecturally unrecognizable, even when they continue to host religious practices, due to the absence of a clear legal framework. Religious denominations other than Catholicism encounter challenges in both internal and external recognition, and their places of worship often constitute what has been described as “resilient” religious cultural heritage (Giorda 2024, p. 19).

Heritage functions as a space where political and religious actors seek to “regulate the difference” between the majority and religious “minorities” (Burchardt 2020), providing legitimacy to contemporary social orders and conferring meaning to specific histories and memories. However, such process often entails a denial of diversity within the nation and its present (Ang 2011). Italy provides a compelling example of how the cultural heritage has the ability to shape the history and collective memory of a nation, as it embodies the tension between a historically dominant and widely perceived religious identity—Catholicism—and the multiplicity of religious traditions that coexist within its borders. In the present context, the nation inevitably harbors populations with diverse pasts, bringing into circulation memories and identities that often transcend or challenge the homogenizing image of nationhood and national heritage (Ang 2011, p. 82).

Furthermore, in Italy, there is a notable absence of clear jurisdiction over non-Catholic places of worship, both at the local and national levels. The legal framework is even more vague and less regulated for religions without a formal State Agreement (the so-called “Intesa”), such as Islam and Romanian Orthodoxy. In truth, within Orthodox Christianity, the Greek Orthodox community is uniquely positioned as the only Orthodox denomination to have entered into an Agreement with the Italian State, whereas others remain classified as “admitted cults” (“culti ammessi”) according to Law No. 1159 of 1929. Relations between the Italian State and the Holy Orthodox Archdiocese of Italy and Exarchate for Southern Europe (hereinafter “the Archdiocese”) are regulated by Law No. 126, enacted pursuant to Article 8 of the Constitution.2 This law is based on the Agreement signed on 4 April 2007, and subsequently ratified on 30 July 2012.

Notably, Article 12 of the Decree-Law No. 126/2012, which focuses on artistic and cultural heritage, states: “The Republic and the Archdiocese undertake to cooperate in the protection and enhancement of assets pertaining to the Orthodox historical and cultural heritage”.3 Regarding the intangible heritage, primarily represented by the Greek language, Law No. 482 of 15 December 1999, entitled “Provisions for the Protection of Historical Linguistic Minorities”, establishes regulations for the preservation of minority languages. Of these, twelve are officially recognized and protected by law. According to Article 2 and in implementation of Article 6 of the Constitution, as well as in alignment with the general principles set out by European and international bodies, the Italian Republic protects the Greek language.

The Archdiocese was officially recognized on 16 July 1998, as a legal entity with civil effects in Italy. The ratification of its Agreement with the Italian State in 2012 granted several rights, including eligibility for state funding to support the construction of its places of worship.

3. Methodology

This study operates within a new and hybrid field: the geo-history of religions (Giorda 2019, 2023, p. 15). The reconstruction was grounded in a spatial approach and an interdisciplinary perspective, incorporating insights from religious studies, the geography of religions, sociology, and ethnographic methods such as on-site visits and interviews with key actors. In particular, for the field research conducted between December 2023 and February 2024, I adhered to the principles outlined in the Manifesto of the international research group ShaRP LAB.4 ShaRP, which stands for Sharing Religious Places, is a network of scholars dedicated to the exploration of the spatial dynamics of religious interaction. This network has developed a collective and highly interdisciplinary approach to investigating the intersections of religion, space, and society (Fabretti and Giorda 2023).

This group helped promote the “Sharing Turn”, whose subject is the sharing of space by two or more religious groups. Sharing refers to a range of proximity possibilities ranging from hospitality to peaceful coexistence, to tolerance, competition, and violent conflict. The theme of religious sharing, approached from a holistic perspective, is addressed using various methodologies, including the study of both sites frequented by multiple religious groups and locations specifically built to foster interreligious dialog, as well as of places where forms of interaction evolve over time—such as many Orthodox places of worship. I interpret the Orthodox place of worship analyzed as a shared religious site, as it exemplifies a transformation in religious identity over time. A church that is no longer in use by the Catholic Church and has been repurposed as an Orthodox place of worship, either temporarily or permanently, represents a specific form of sharing: this transformation, understood as a conversion from religious place X (Catholic) to religious place Y (Orthodox), constitutes a form of diachronic sharing, characterized by substitution (Giorda 2023, p. 17).

By adopting the perspective of ShaRP LAB, I interpret religious sites not as static backdrops but as active agents in the construction of history, encompassing both material and immaterial dimensions. This includes not only places of worship originally built for religious purposes but also spaces initially designed for other uses—whether permanent or temporary—that have been, and continue to be, used as gathering places by religious groups (Giorda 2023). Furthermore, spaces and materiality are widely acknowledged as key elements in the construction of memory (Niglio 2025), and places serve as the vibrant core of any religious cultural heritage, as highlighted by the editors of this Special Issue in the Introduction.

Starting from the Manifesto—recently published in the journal “Annals of Religious Studies” of the ISR-FBK—the ShaRP LAB group has built a research protocol that explicates and deepens the synergy of methodological approaches used in the study of religious places. In an effort to ensure methodological coherence, I followed the unified ShaRP research protocol for examining the Orthodox worship site under examination. I aim to apply the protocol and adopting some of its different perspectives5 (historical, geographical, architectural, ethnographic, sociological) to a little-known and little-studied case: the Greek Orthodox Church of St. John the Baptist.

First, a historical framework was established, placing both the community and the religious site within their broader historical, cultural, political, and economic contexts. Reconstructing the foundation, legal framework, and developments over time, as well as identifying responsible parties, were essential steps in the historical contextualization of the place of worship.

Geographic framing was achieved through the study of the positioning of the Church of the Nativity of St. John the Baptist, in the area, neighborhood, and specific urban space. Additionally, attention was given to the accessibility of this space and the origins of the people who frequent it.

To question the visibility or invisibility of the place of worship and its recognizability or camouflage, an architectural framing was also addressed. This involved the examination of the alignment—or lack thereof—with the religious canons of the community of reference. In this regard, key considerations included: the spatial changes, both indoor and outdoor, that have occurred over time due to regulatory, liturgical, customary and cultural shifts; the management characteristics of spaces dedicated to particular groups; the accessibility of both outdoor and indoor spaces throughout the day, week, and year; as well as the material and immaterial aspects of Orthodox identity and their influence on the experience of space in the liturgy.

The sociological and ethnographic framing was facilitated by field research, which included two semi-structured interviews with the Greek parish priest (February 2024 and October 2024) and informal conversations with church members during the site visit. The observation focused particularly on the primary liturgies, events, and rituals in order to capture both the material and immaterial dimensions of the community’s religious heritage.

4. The History of Orthodox Places of Worship in Turin

In Turin, the presence of Orthodox Churches offers an interesting case study to explore how the material and immaterial elements of these places of worship intertwine, creating a rich tapestry of traditions, identities, and collective memory. The city offers a unique context for studying the relationship between religious spatiality, cultural heritage, and plural memory. With its long history of religious diversity, Turin serves as a valuable lens through which to examine the religious cultural heritage of non-majority groups.

Surveying the Italian religious landscape, Orthodoxy—shaped by recent migratory flows and its historical roots in Italy—is now estimated to be the third-largest denomination in terms of believers, following Catholicism and Islam (Cf. Aa. Vv 2023). Social, political, and economic factors have prompted many Orthodox communities to migrate to Italy, resulting in a stable religious presence that is physically and spatially manifested through places of worship.

The settlement of the first Orthodox communities in Italy dates back to the late 15th century, tied to the emigration of Byzantine Greeks after the fall of Constantinople and the collapse of the Byzantine Empire. However, the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese gained legal recognition only in 1998, ratifying an Agreement with the Italian State in 2012. Since then, Greek Orthodox communities have grown significantly, with 77 places of worship now established.6

The earliest institutional presence of an Eastern Christian church in Turin dates back to the late 18th century, with the establishment of a Russian-rite chapel designed for the local diplomatic headquarters (Berzano and Cassinasco 1999, p. 103). From the second half of the 20th century, various Orthodox communities began to take root in Turin. As Luca Bossi observes, “The immigration of single families fleeing the 1917 revolution in Russia and of mixed families from post-World War II Greece represents a small vanguard—an early “flash”—of later migrations” (Bossi 2024, p. 146). Starting in the 1960s, the Greek Orthodox presence in the city, already established for two decades, was reinvigorated primarily by university students. Simultaneously, industrial Turin attracted a small wave of Russian citizens seeking employment. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the city saw also the formation of the first communities of Coptic, Ethiopian, and Eritrean families, while groups of Italo-Romanian families, descendants of Italian immigrants to Romania between about 1870 and 1940, formed the foundational local community, branching off from the Orthodox parish already established in Milan (Bossi 2024).

The third major phase of immigration would profoundly alter Turin’s urban religious demographics and reshape the history of its places of worship. Orthodox churches became central points of reference for newcomers to Italy. As the number of believers grew, informal gatherings evolved into formal parishes, establishing public places of worship. Biritualism,7 referring to the faculty granted to Catholic priests of the Latin rite to celebrate services in the Byzantine or in other ancient Eastern churches rites, is a phenomenon that “constituted an important page in the history of Orthodox communities in Piedmont: in many cases it was the factor in their formation and development” (Berzano and Cassinasco 1999, p. 34). This phenomenon has successfully guided isolated Eastern Orthodox immigrants into cohesive, independent communities. The Orthodox community’s desire to establish their own places of worship led to the construction of churches and parishes across Italy. These efforts were further accelerated by biritualism initiatives, which facilitated the rapid proliferation of Orthodox worship spaces (Berzano and Cassinasco 1999, p. 35).

In Turin and throughout Italy, the orthodox communities are primarily located in Catholic churches leased by local dioceses. While these churches retain their Catholic architectural identity, they provide Orthodox believers with spaces designed and built for religious services, often of significant historical and artistic value (Bossi 2024, p. 145). As of February 2024, fourteen Orthodox churches are located within the city, including the Romanian Orthodox parish of the Holy Forty Martyrs of Sebaste, which was inaugurated in 2016. This church, built entirely of wood in the style of Romanian Orthodox churches from the Maramureș region, is the first and only church in the area constructed ex novo for Orthodox worship (Cozma and Giorda 2022). Located in Moncalieri, approximately 300 m from the Turin border, it is the largest Romanian Orthodox church in the southern quadrant of the city. Its location and distinctive architecture are clearly visible and recognizable from the outside, serving both the local and greater Turin populations; for this reason, it is included in the count. It is not surprising that “the first Romanian Orthodox church built ex novo arose in the Turin area (…) if one thinks of the innovations concerning the management of religions that this city has experienced and still experiences” (Giorda 2023, p. 197). Of the fourteen churches in Turin, eleven are housed in Catholic diocese properties. This underscores the central role that the Catholic diocese has played-and continues to play-in shaping Orthodox spatial strategy.

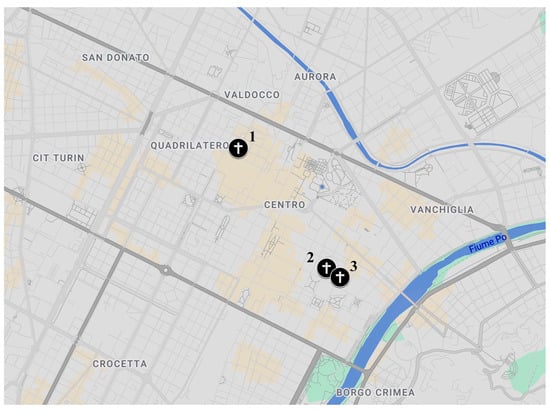

In the research I conducted, the focus was on Orthodox Christian places of worship in Turin’s historic center (Figure 1), including the Church of the Nativity of St. John the Baptist, which is the main subject of this article (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Mapping of Orthodox places of worship in the historic center of Turin—February 2024. Cross number 1 represents the location of the Greek Orthodox Church of the Nativity of St. John the Baptist. Cross number 2 represents the location of the Romanian Orthodox Church of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross. Cross number 3 represents the location of the Moldavian Orthodox Church of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker. Figure: Author’s own.

Table 1.

Places of worship of Orthodoxy in the historic center of Turin—February 2024.

These churches share a common Orthodox faith and urban location, yet they differ in linguistic and ethnic composition, as well as in the level of state recognition they have achieved. The three places of worship analyzed throughout this research are attended by the Greek, Romanian, and Moldovan Orthodox communities.

Turin’s ties to the Greek Orthodox world are longstanding, although the official presence of the Greek Orthodox Church in the city dates back only to the 20th century. Since the 1960s, regular celebrations in the Byzantine rite and Greek language have been held in the capital of Piedmont, initially starting as biritual initiatives to meet the needs of numerous university students and Greek families, who played a key role in revitalizing the Orthodox presence in the region during that period (Berzano and Cassinasco 1999). In 2000, the Catholic archdiocese granted the Greek Orthodox community the use of the church dedicated to the Annunciation, known as “Church of the Orphans” (“delle Orfane”).

The Romanian Orthodox presence in Turin began in the late 1970s. Indeed, the longest presence of an Orthodox church in the city is that of St. Parascheva Parish, founded in 1977 as a branch community of the Romanian Orthodox parish in Milan, and it was established as an independent parish in 1979, under the organization of Gheorghe Vasilescu. This parish was one of many initiated by young Romanian Orthodox clerics, who had arrived in Italy as students at Catholic theological faculties. It was within this context that the first Orthodox parishes and places of worship were established in major urban centers, before the end of the communist regime. However, with the fall of Romania’s communist regime, and unemployment soaring to 30%, immigration increased notably. In Turin, the 2006 Olympic Games attracted new foreign residents, leading to a significant increase in the demand for labor and jobs in construction and tourist accommodation sectors (Bossi 2024). The majority of these immigrants were Romanian citizens. Since the 1990s, the parish has been a point of reference for the thousands of Romanians arriving in Italy, providing a “network” of support and integration.8

The St. Parascheva Parish is an early example of religious coexistence and eventual substitution. From its founding in 1978 until 1981, it shared its liturgical space with the Italo-Albanian Catholic parish of the Byzantine rite of St. Michael the Archangel. This arrangement was facilitated by the relationship between Catholic pastor Giovanni Bugliardi and Romanian pastor Gheorghe Vasilescu, with Orthodox liturgical celebrations held at times agreed upon by both. However, the need for an independent place of worship led Father Vasilescu to approach the Piedmont Ecumenical Commission, which then intervened with the Diocesan Curia of Turin. As a result, on 30 January 1981, a contract was signed granting the Romanian parish exclusive use of the Church of Our Lady of Refuge, which had been disused for several years. The church, owned by Opera Pia Barolo, was subsequently renovated, adding an iconostasis in 1983, followed by the consecration of a new altar in 2012. In September 2015, due to restrictions on the use of the courtyard, worship activities were moved to a building on Corso Vercelli 481/9, a Catholic church that had been unused for seven years. The relocation was once again favored by the Catholic church authorities in Turin, with Archbishop Cesare Nosiglia intervening at the request of Romanian Bishop Siluan.

Following St. Parascheva’s successful example, other Romanian Orthodox communities were established in Turin. As a result of the significant wave of immigration from Romania, Italy—particularly Turin—has become a preferred destination for citizens of the Republic of Moldova, with migration trends often mirroring those of Romania. Over the past three decades, Moldovan migration has played a pivotal role in the growth of Orthodox Christian communities in Italy. Despite this significant contribution, statistical and demographic data on these migrations remain limited. The people of Moldova, although divided into five distinct ethnic groups, with the dominant ethnicity and language being Romanian and Moldavian, all share the Orthodox faith. Furthermore, “the Orthodox Metropolia of Moldova is canonically placed under the Moscow Patriarchate, although the Patriarchate of Romania disputes this affiliation, claiming sovereignty over the territories that belonged to the Kingdom of Romania before World War II, and maintaining part of the churches of the Republic of Moldova under its sovereignty” (Berzano and Cassinasco 1999, p. 183).

Parishes with a Moldovan majority, although fewer in number, are still spread throughout Italy and are generally linked to the Diocese of the Romanian Patriarchate. These parishes are typically led by Moldovan priests and are characterized by a stronger adherence to Moldovan traditions and ritual practices, particularly the use of the Julian (or “old calendar”) liturgical calendar. The places of worship attended by Moldovans are largely divided between parishes affiliated with the Bucharest Patriarchate and those linked to the Moscow Patriarchate. As Marco Guglielmi observes, “In a suggestive way, then, the Italian scenario reflects and reshapes that of the country of origin, divided geopolitically as much as ecclesiologically between Russian and Romanian influence, between Soviet heritage and pan-Romanian instances, between a Slavic Patriarchate with a clear multinational vocation, with Moscow as its capital, and one with a markedly national profile, claiming a central role in the ethnogenesis of the Romanian people and in the birth of its nation” (Guglielmi 2022, p. 64).

While social, political, and economic factors have been the driving forces behind immigration, prompting many Orthodox communities to move to Italy, the establishment of a stable religious presence is one of the key outcomes of this migration. In Italy, one of the most active and organized networks has always been the religious network, which has manifested spatially in places of worship. Religious and ethnic-national identities often intertwine, materializing in churches that serve as primary gathering spaces for immigrants. Places of worship have also played a central role in the visibility of minorities: the ability to build a place of worship is the emblem of social recognition and religious freedom, often preceding formal state recognition of these rights. In addition to being spaces for spiritual practice and assistance, these places serve as refuges for reception, integration, and orientation for new residents, where social relationships and solidarity networks are forged, reinforcing and consolidating the sense of community.

For these reasons, I interpret Orthodox parishes as vital instruments for the preservation and transmission of heritage abroad, encompassing both tangible and intangible forms. The intangible heritage, especially the native language, is a particularly strong cultural and identity marker, reinforcing the connection to the homeland and fostering bonds among believers. Without a church, particularly for newcomers, there would be no space to serve as a critical point of reference, both spiritually and in terms of identity. However, the ambiguity surrounding Italian jurisdiction regarding religious freedom, the construction of places of worship and the protection of the religious heritage of minorities complicates efforts to secure protections, permits, and identify suitable spaces for new constructions. Beyond institutional invisibility, these communities are often physically invisible in the urban space (Bossi 2024, p. 58), as they adapt and settle to secular spaces or share places of worship that are already affiliated with other religious traditions, as is the case with the Greek Orthodox Church under consideration.

5. The Greek Orthodox Church of the Nativity of St. John the Baptist as a Case Study

The Greek Orthodox Church of the Nativity of St. John the Baptist in Turin represents an intriguing case study in comparison to other examples outlined. Notably, it is the only church to have obtained legal recognition from the State. Despite the legal status of the church, there appears to be no genuine recognition regarding the preservation of the community’s cultural heritage, both material and immaterial. As highlighted in Section 1, although Article 12 of Law No. 126 of 30 July 2012 explicitly establishes a formal collaboration between the Republic and the Archdiocese for the protection and enhancement of assets pertaining to the Orthodox historical and cultural heritage, there seems to be a lack of tangible protection in practice. As noted by the parish priest in an interview, “We have been open for 24 years, and from the institutions, we have received neither damages nor benefits” (Fr. Restagno 2024, 7 February).

In 2000, the Catholic Archdiocese granted the Greek Orthodox community use of the Church dedicated to the Annunciation, known as “of the Orphans” (“delle Orfane”), located in the historic center of Turin (Quadrilatero Romano, Circoscrizione I). The church is legally owned by the Ancient Institute of the Poor Orphans of Turin and is part of a larger building complex named after the Most Holy Innocents. The church is, however, currently managed by the Greek Orthodox Parish of the Nativity of St. John the Baptist. Originally built in 1667, the structure first served as a chapel for the city’s female orphanage. As Father Restagno explained to me in an interview, “the Greek Orthodox community occupies this place through ‘a friendly loan’ without a contract” (7 February 2024).

Located at the corner of a street and an open urban space, the church sits in an area that was part of the third expansion of the historic city, dating back to the 18th century, before undergoing 20th century urban redevelopment. It is surrounded by large religious and charitable architectural complexes, as well as numerous commercial activities, ensuring a constant flow of people. Additionally, it is adjacent to Palazzo Barolo, a cultural hub hosting various museum, musical, artistic, and educational activities.

This is the only Greek Orthodox parish in Turin,9 and apart from the parish priest, there are no other deacons serving in the church. The city is also home to Greek Catholics, whom the early Greek Orthodox community turned to for worship. Fr. Restagno recalls that in the 1960s and 1970s, two priests from the Turin diocese were granted biritualist status to accommodate the large number of Greek students in the city. They began celebrating Mass in the Byzantine rite at the Church of the Exaltation of the Cross in Piazza Carlo Emanuele II, a church still attended by the Romanian Orthodox community today. In addition, Byzantine rite services were held in a chapel, which remains closed due to necessary renovations that the City of Turin has yet to carry out.

I interpret this church as a shared religious place, as it has undergone a transformation in its religious identity over time. The Orthodox identity remains architecturally invisible because the community occupies a former Catholic church. Externally, the Greek Orthodox presence is signaled by a panel placed above the entrance, marking the building as an Orthodox site. Greek identity is further represented through the display of Greek flags both outside and inside the church. A garland of four triangular flags adorns the doorframe: two representing the flag of Greece, and two bearing the double-headed eagle on a gold background, the symbol of the Greek Orthodox Church. The latter flag also hangs from a pole located to the right of the parish entrance, above a metal sign that reads: “Church of the Most Holy Annunciation (“S.S. Annunziata”) (1570) of the Old Institute of the Poor Orphans of Turin, currently in use by the Greek Orthodox parish of the Nativity of St. John the Baptist”, along with a phone number and the Divine Liturgy schedule (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The Greek Orthodox Church of the Nativity of St. John the Baptist (Turin). Photo: Author’s own.

The celebrations and liturgies are primarily in Greek but also in Italian since the parish is attended by people from different countries.10 Since its establishment in 2000, the community has evolved: initially composed of Greeks settled in Turin, it has since then expanded to include Italians, Romanians, Ukrainians, and Russians, with the number of attendees growing over the years. The majority of the parishioners are from mixed families, with the exception of the Romanians. Although the Greek community was once the largest, today it is the Romanian community that forms the most significant portion of parishioners. The congregation’s average age is around 40–50 years, which is relatively young compared to the typical religious demographic. Indeed, many children also attend the church. Interestingly, most attendees live outside of Turin, as the distribution of parishioners across churches is often determined not by proximity to their homes but by their attachment to the priest and the church itself. As Fr. Restagno pointed out, many Romanians and Romanian families attend the church precisely “because they feel comfortable” (7 February 2024). Although there is no recent data on the number of Greek Orthodox in Turin, older archives report around 200, with Fr. Restagno indicating that “there are definitely more to date” (7 February 2024).

Although the Greek Orthodox Church belongs to the Ecumenical Patriarchate, which has obtained an Agreement with the State, it lacks adequate community space to meet its needs. The “friendly loan” arrangement—granted without a formal contract—significantly limits access to the majority of premises adjacent to the liturgical hall. Due to the church’s small size, it can only accommodate a limited number of worshippers. This spatial constraint becomes particularly problematic during major religious and civil festivities, which attract larger crowds. On such occasions, the number of attendees exceeds the church’s capacity, forcing the community to gather outside (Fr. Restagno 2024, 7 February). The portion of the Old Institute of the Poor Orphans of Turin complex granted to the Orthodox parish, in fact, includes only the church itself and the small sacristy, which is accessible solely via the main entrance to the liturgical hall. A connection between the church and the institute’s entrance was walled off when the concession was granted, further restricting access, as the chancel, for instance, can only be reached through a staircase located within the institute’s premises. These significant limitations underscore the pressing need for additional, and more suitable, space to accommodate the community’s activities, although the parish priest recognizes the strategic importance of its central location. From the interview with Father Restagno, it emerges that he hopes to eventually tear down the wall blocking access to a larger room, reiterating that he does not wish to relocate, as the area has become a familiar and integral part of the community’s identity. However, it is paramount to note that the church’s central location, despite offering some visibility, attracts few tourists. Its visitors are mostly school and scout groups engaged in activities exploring themes of diversity and religious integration (Fr. Restagno 2024, 7 February). The scarcity of tourists is not a problem in itself but rather a consequence of a deeper issue. Although the church is located in an area heavily frequented by tourists, it is often overlooked due to its architectural “invisibility”, as it is housed in a former Catholic church. Despite its rich cultural and religious heritage, the church is rarely visited by outsiders and does not receive the recognition it deserves. As a result, it attracts only a small number of tourists, some of whom are already familiar with the church or belong to the Orthodox faith.

An Inspection conducted by archit”ct G’ulia De Lucia shows that the Greek Orthodox church is in a good overall state of preservation.11 The small façade, restored in the 1950s after sustaining war damage, has been the subject of multiple interventions. Restoration work has also been carried out on the roofs and the interior of the church, although archival records documenting these efforts are inconsistent. In 2005, restoration work was carried out on the façade and side elevations, while in 2012, movable works of art, including the canvases of “St. Francis de Sales”, “St. Ignatius of Loyola”, and “the Annunciation” were restored. Further interventions in 2013 targeted the overall liturgical hall, including its decorations and interior surfaces. It is challenging to define with precision the procedural timeline of these works, due to the fact requests for authorization of comprehensive restorations are documented repeatedly in 2000, 2013, and 2018, with evidence of a grant from the Compagnia di San Paolo in 2001. Despite these efforts, the specific details of what was authorized versus what was actually carried out remain unclear.12

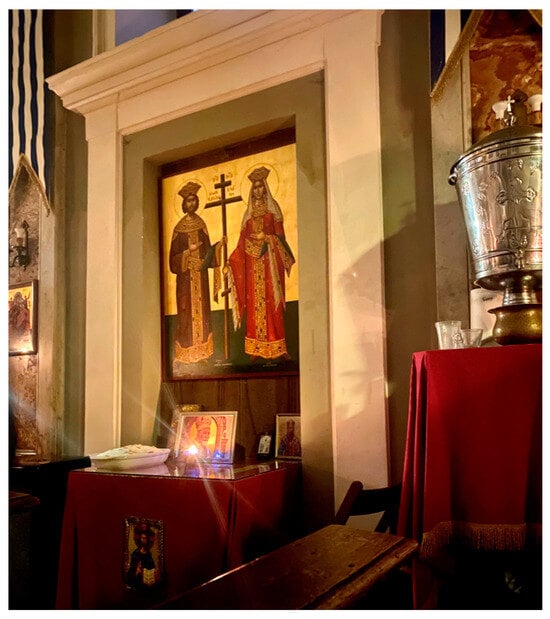

While the architecture of the church conceals its Greek Orthodox identity externally—retaining the appearance of a Catholic church and effectively camouflaging its current religious use—the interior is distinctly Orthodox. The space is adorned with numerous sacred objects and symbols, such as candles, icons, photographs, flags, candelabra, lanterns, service tables, and a prominent iconostasis (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The interior of the Greek Orthodox Church of the Nativity of St. John the Baptist (Turin). Photo: Author’s own.

Since 2000, the church has been furnished with liturgical items, nearly all of which were sourced from Greece and funded by the community. The hall contains several horizontal pews and wooden chairs positioned near the iconostasis for the faithful. However, having retained much of the Catholic church’s original furnishings, it lacks the expansive, open central space that typically characterizes canonical Orthodox churches and allows for the tradition arrangement of worshippers inside the hall.

A central and highly visible element within the space is the light emanating from the candles, which holds profound significance in Orthodox liturgy, symbolizing the passage from death to life. Thus, the church is usually filled with candles, candelabras, chandeliers, and lanterns. Notably, there are special golden candelabras that hold both lighted and unlit candles, dedicated, respectively, to the living and the dead. There is no shortage of space at the entrance dedicated to sacred objects, where candles, books, icons, and incense are displayed and sold.

Connotating the national identity of the church interior are the four Greek flags, unfurled on the pilasters along the long walls, and two additional flags with the double-headed eagle displayed on the pilasters of the short wall flanking the iconostasis. Another subtle yet meaningful marker of identity within the church is the attire of some worshippers, which is consistently neat and appropriate to the context. The church also houses a small archive, consisting of few documents, though it is in a state of disarray and difficult to access due to its limited organization. Additional archival materials are preserved at the Holy Archdiocese of Venice, but as Fr. Restagno articulated, “they have suffered various damages over time due to floods” (7 February 2024).

Celebrations and liturgies are conducted primarily in Greek, but also in Italian, to accommodate parishioners with diverse backgrounds. The Greek identity is of great significance and is especially reflected in the use of the Greek language. The Gospels are read in their original language, Greek, highlighting its historical significance as a universal language understood everywhere when the Bible was first translated by Jewish scholars. Musical performances within the liturgy play a fundamental role, especially for this community, which places great emphasis on music and singing. Before Vespers, the Simandron (in Greek σήμαντρον), a percussion instrument struck with a wooden hammer, is played both around the church and at its entrance on the surrounding streets a few minutes before the liturgy begins. Its sound serves as a call to prayer, summoning the faithful and monks to gather. The church’s visibility is linked to sensory perception, encompassing sight, sound, and smell (Schafer 1994). The ringing of the Simandron shapes communal and spatial identities through sound, producing what scholars have described as identities and geographies of sound (Gallagher and Prior 2013). The choir director plays this instrument, and in the evening hours, the church transforms into a hub for pre-Gregorian music studies and Roman Byzantine singing school. The parish organizes various concerts featuring Byzantine chants, one of the most popular being held on Greek Language World Day (9 February). Indeed, Greek identity is also celebrated by the parish through the various national holidays commemorating historical and cultural events. One notable concert, performed by the “Irini Pasi Ensemble”, was part of the project “Greece in Turin from Alpha to Omega” to commemorate Greek Language World Day (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The concert of Byzantine chants with the “Irini Pasi Ensemble” in the Greek Orthodox Church of the Nativity of St. John the Baptist (Turin).

The final event of these three-days celebration of Greek culture was held inside the church. The texts sung in Greek represent a significant cultural heritage, “not only for the Greek people but also as a heritage of humanity” (Fr. Restagno 2024, 10 February). The concert opened with the Byzantine Hail Mary sung in Greek. As parish priest explained, “The apostles wrote the Gospels directly in Greek, chosen precisely because this language was universal, could reach anywhere, be understood anywhere (…) the Greek language being this cultural, spiritual, mystical vehicle of contact between peoples from antiquity to the present day” (Fr. Restagno 2024, 10 February). The use of the Greek in the liturgy aims to preserve a heritage that is simultaneously religious, cultural, and national. The sung Greek is the classical language of the Bible, and Byzantine music, with its ancient roots, is pre-Gregorian, modal, and non-tonal, relying on natural scales rather than the tempered ones of Western music. This type of musical experience, accompanied by Greek language, serves as a cultural, spiritual, and mystical bridge, connecting peoples across centuries, from antiquity to present day.

The Orthodox church extends its presence beyond its walls through the evocative scent of incense and the aromas of foods and sweets prepared for religious festivities and liturgies, contributing to the public smellscape (Aras 2015). The intense fragrance of incense, which permeates all liturgies, spills into the streets, creating an olfactory experience that influences both the group of worshippers inside the church and the outsiders who casually encounter this olfactory atmosphere. This smellscape is further enriched by the symbolic dishes prepared and shared during religious celebrations, evoking reflective memories of historical episodes. Food in this context transcends mere nourishment, becoming a metaphorical and a cultural element, recalling the history of the community (Harris 2015). One notable example is Còlliva (Greek: Κόλλυβα), a cake blessed and offered in church among the faithful in memory of the deceased (Figure 5). Typically, Còlliva is shared with the participants in church memorials, and later brought to relatives or friendly homes. As Father Restagno articulated during the interview (7 February 2024), “This cake symbolizes resurrection: just as the grain of wheat that fell into the ground, buried, changes texture but does not rot, and then grows better and more beautiful, in the same way the human body buried in the earth also decomposes, to rise again without being damaged, glorious in eternity”. He further explained that the origins of these customs can be traced directly to the Bible: “If a grain of wheat, as Jesus says, does not touch the ground, it cannot rise again” (7 February 2024).13

Figure 5.

The cake (Còlliva) brought by the faithful in honor of the deceased at the Greek Orthodox Church of the Nativity of St. John the Baptist (Turin). Photo: Author’s own.

Another significant example of culinary tradition within the Greek Orthodox Church is the Vasilopita, from the Greek Βασιλόπιτα, meaning “St. Basil’s cake”. This special cake is baked on January 1 and again throughout the month in honor of a miracle attributed to St. Basil. A distinctive feature of Vasilopita is the inclusion of a coin hidden inside the cake. Tradition holds that the person who finds the coin is believed to have had their prayer answered by the saint, symbolizing blessings and good fortune for the year ahead. Another beloved tradition is that of the Fanouropita, a cake dedicated to St. Fanurio, an ancient military martyr whose memory was nearly lost for centuries. According to tradition, devotion to St. Fanurio began when someone prayed to him and began to witness miracles. As a result, the custom of baking and offering him this cake arose as an expression of gratitude and devotion. The cake is traditionally prepared on 27 August but can also be made whenever someone wishes to pray for something loss of for divine assistance. In addition to cakes, other symbolic foods are shared in the church throughout the liturgical calendar. For instance, on August 6, grapes are offered to the church attendees to celebrate the first fruits of the vine, while at Easter time, hard-boiled eggs painted red are brought and shared among the faithful.

6. Conclusions

The Greek Orthodox Church of the Nativity of St. John the Baptist conceals behind its walls both material and immaterial elements that testify to and transmit religious and cultural expressions, both ancient and contemporary, which remain largely unknown. In addition, this place of worship serves as an important point of congregation and integration, maintaining a strong connection with the homeland primarily through the use of the Greek language. The language is indeed regarded as a vital instrument for transmitting memory, heritage and national identity among the Greek community in Italy, which is a part of a broader network of Orthodox faithful residing outside their native countries. The parish priest interviewed also stressed the significance of using the Greek language in celebrations, both civil and religious, to preserve national and cultural identity. Activities within the church, particularly those involving music and language, contribute to the intentional preservation of cultural heritage.

Language and religion are two main cultural markers of collective identities, and, as such, play a critical role in distinguishing between “majority” and “minorities” groups within a society (Ruiz Vieytez 2021). In the Italian Constitution, the only “minorities” explicitly mentioned are linguistic minorities (Palici di Suni 2019, p. 79), which are granted protection through special regulations outlined in Article 6. From a legal standpoint, the Italian Republic acknowledges the importance of safeguarding not only Italian language, but also the languages and cultures of historical minorities. Law No. 482, passed on 15 December 1999, titled “Provisions on the Protection of Historical Linguistic Minorities”, sets forth regulations aimed at the preservation of these minority languages. Twelve of these are officially recognized and protected by the law, including Greek. According to Article 2, “In implementation of Article 6 of the Constitution and in alignment with the general principles established by European and international bodies, the Republic protects the language and culture of the Albanian, Catalan, Germanic, Greek, Slovene, and Croatian populations, as well as those speaking French, Franco-Provençal, Friulian, Ladin, Occitan, and Sardinian”.14

The Greek Orthodox Church’s Agreeme”t wi’h the Italian State and recognition as a “historical linguistic minority” seem to be insufficient to achieve an effective valorization of its heritage, both tangible and intangible. In this context, the heritage practices of minorities, “that is, their attempts to keep the memory of their past homelands alive, tends to remain hidden from public view” (Ang 2011, p. 87). Indeed, this church, too, remains invisible and camouflaged, even to the surrounding society, which lacks the tools to understand and decipher the significance and practices taking place within this space, which, from the outside, appears “as if” it was a Catholic church. This reflects a deeper issue: legal and formal recognition does not necessarily translate into genuine, social acknowledgment. Italian norms, which predominantly reflect the majority’s interests, often fail to offer effective or substantial recognition for minority groups. Thus, there is a significant gap between prescribed legal rights and the lived experiences, between top-down policies and bottom-up realities.

This study highlights how the issue of religious heritage among minority groups extends far beyond the material preservation of objects or spaces. This place of worship materializes the community’s memory, primarily through its intangible heritage, which includes music, liturgical chants, rituals, olfactory and soundscapes—elements that blend with the surrounding urban environment. It is essential to analyze new approaches to the valorization of cultural and religious heritage of minority groups in Italy, not only to protect their history, but also to reconsider and expand our understanding of heritage and identity in a society increasingly shaped by religious and cultural diversity.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as the research focused exclusively on the historical and religious aspects of the church, including its tangible and intangible heritage, and did not involve human subjects. The interviews conducted with the parish priest were solely centered on the history and heritage of the church, and informed consent was requested and obtained prior to the conversations. At no point were sensitive, personal, or health-related data collected. Furthermore, the study did not involve any clinical, pharmacological, or medical activities, and therefore does not meet the criteria that would require mandatory approval by territorial or national ethics committees. In light of these considerations, and in accordance with Italian regulations governing historical research, ethical committee approval was not required for this study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | This article presents the results of two fieldwork projects conducted in Turin, Italy (2023; 2024). Field observations at Orthodox churches were carried out in December, January, and February 2023–2024. The first three interviews with parish priests were conducted in February 2024, as part of my Master’s thesis entitled“Luoghi religiosi nello spazio urbano: le Chiese ortodosse nel centro storico di Torino”. Subsequently, from September to December 2024, I conducted an in-depth study on the religious heritage of the so-called “minorities” in the city, as part of the project “Il patrimonio culturale e religioso a Torino: per una tutela degli spazi della diversità”, promoted by the Fondazione Benvenuti in Italia and coordinated by Maria Chiara Giorda and Sterfania Palmisano. As part of this project, I conducted 20 interviews with leaders and representatives from various religious communities, including the three Orthodox priests of the churches in the city’s historical center, whom I had previously interviewed. |

| 2 | Constitution of the Italian Republic: https://www.senato.it/documenti/repository/istituzione/costituzione_inglese.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2024). |

| 3 | See Article 12 of Law No. 126 of 30 July 2012: https://www.normattiva.it/uri-res/N2Ls?urn:nir:stato:legge:2012;126 (accessed on 15 December 2024). |

| 4 | See the Manifesto ShaRP: https://books.fbk.eu/media/uploads/files/21._Manifesto_Sharp.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2024). |

| 5 | The protocol includes different perspectives: historical, geographical, architectural, ethnographic, sociological, art historical, and digital humanities. In my research, I adopted only 5 of these perspectives. |

| 6 | Including 66 parish churches, 7 monasteries and 4 sanctuaries. See (Giorda 2023, p. 41). |

| 7 | Legally, biritualism takes the form of a renewable license granted by the Congregation for the Eastern Churches. |

| 8 | The parish was registered in Turin under the name “Romanian Orthodox Parish Santa Parascheva in Turin, Piedmont, Aosta Valley and Liguria”, which indicated the area where about 700 Romanians lived. See in particular (Giorda 2023, p. 107). |

| 9 | In Italy, churches of the Patriarchate of Constantinople are present in the following regions: Veneto (7), Friuli-Venezia Giulia (8), Trento (1), Lombardy (10), Piedmont (2), Emilia-Romagna (6), Tuscany (5), Liguria (2), Romagna (4), San Marino (1), Marche (6), Abruzzo (2), Lazio (7), Umbria (3), Campania (7), Apulia (8), Calabria (9), Sicily (8), and Sardinia (2). See in particular: https://ortodossia.it (accessed on 20 December 2024). |

| 10 | The parish priest in the course of the interview informs me that on Sundays, the Lord’s Prayer is recited in eight languages: Georgian, Aramaic, Greek, Italian, Romanian, Slavic, Albanian, and English (Fr. Restagno 2024, 7 February). |

| 11 | The inspection activity took place on 28 April 2023 by architect Giulia de Lucia. See: De Lucia and Caterino (2024). |

| 12 | There is little clarity regarding what has been authorized and the actual restoration work carried out, as no documents exist to certify all phases of the process. I believe this example is relevant because it illustrates the complexity and challenges inherent in the conservation process of these religious sites. In particular, it highlights how the lack of adequate documentation makes it difficult to accurately reconstruct the details of the restoration work, including the timing and methods employed. The only available information about the restorations of this church has been provided by architect Giulia de Lucia. See: (De Lucia and Caterino 2024). |

| 13 | This custom dates back to early Christian times, and is related to the Perídeípna (Greek: Περίδειπνα,), the meal held after the funeral services in ancient Greek and other cultures. Còlliva is prepared for PsychoSavvata (i.e., “Saturdays of departed souls”), such as the Saturdays before Carnival Sundays, Tyrinis and First Lent, and the Saturday before Pentecost Sunday. It is also made whenever people want to commemorate deceased loved ones. |

| 14 | See: https://www.normattiva.it/uri-res/N2Ls?urn:nir:stato:legge:1999;482 (accessed on 28 December 2024). |

References

- Aa. Vv. 2023. Dossier Statistico Immigrazione 2023. Rome: Centro Studi e Ricerche IDOS in partenariato con il Centro Studi Confronti. [Google Scholar]

- Ang, Ien. 2011. Unsettling the Nation: Heritage and Diaspora. In Heritage, Memory and Identity. Edited by Helmut K. Anheier and Yudhishthir Raj Isar. Cultures and Globalization Series, 4; Los Angeles and London: Sage Publications Ltd., pp. 82–94. [Google Scholar]

- Aras, Roxana Maria. 2015. Sacred Smellscapes: The Olfactory in Contemporary Christian and Muslim Libanese Communities. Master’s thesis, Department of History, Central European University, Budapest, Hungary. CEU eTD Collection. [Google Scholar]

- Berzano, Luigi, and Andrea Cassinasco. 1999. Cristiani d’oriente in Piemonte. Torino: L’Harmattan Italia. [Google Scholar]

- Bossi, Luca. 2024. Le religioni e la città. La governance locale della diversità. Bologna: Il Mulino. [Google Scholar]

- Burchardt, Marian. 2020. Regulating Difference: Religious Diversity and Nationhood in the Secular West. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burchardt, Marian, and Maria Chiara Giorda. 2021. Geographies of Encounter. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Cozma, Ioan, and Maria Chiara Giorda. 2022. Luoghi di culto della Chiesa ortodossa romena in Italia: Dinamiche di insediamento. In Le Chiese romene in Italia. Percorsi, pratiche e identità. Edited by Marco Guglielmi. Rome: Carocci Editore & Biblioteca di Testi e Studi, pp. 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- De Lucia, Giulia, and Roberto Caterino. 2024. Chiese del centro storico di Torino. Interpretazione storica delle azioni di cura e conservazione di un patrimonio urbano per la pianificazione di strategie sistemiche. Torino: Fondazione 1563 Arte e Cultura. [Google Scholar]

- Fabretti, Valeria, and Maria Chiara Giorda. 2023. Religioni e spazialità/Religions and Spatiality. In Annali di studi religiosi. Trento: FBK Press, vol. 24, pp. 123–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fr. Restagno, Iosif. 2024. The Greek Orthodox Church of the Nativity of St. John the Baptist, Turin, Italy. Personal communication.

- Gallagher, Michael, and Jonathan Prior. 2013. Sonic Geographies: Exploring Phono-graphic Methods. Progress in Human Geography 38: 267–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorda, Maria Chiara. 2019. Geografia delle religioni. In Manuale di Scienze della religione. Edited by Giovanni Filoramo, Maria Chiara Giorda and Natale Spineto. Brescia: Morcelliana Scholé, pp. 201–22. [Google Scholar]

- Giorda, Maria Chiara. 2023. La chiesa ortodossa romena in Italia. Per una geografia storico-religiosa. Rome: Viella. [Google Scholar]

- Giorda, Maria Chiara. 2024. History and Heritage of the Great Mosque of Rome: Interdisciplinary Approaches through the Space. Historia Religionum: An International Journal 16: 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmi, Marco. 2022. Le Chiese romene in Italia: Percorsi, pratiche e identità. Rome: Carrocci Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Marvin. 2015. Buono da mangiare. Enigmi del gusto e tradizioni alimentari. Torino: Einaudi. [Google Scholar]

- Knott, Kim. 2005. The Location of Religion: A Spatial Analysis. London: Equinox. [Google Scholar]

- Knott, Kim. 2010a. Geography, Space and the Sacred. In The Routledge Companion to the Study of Religion. Edited by John Hinnells. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Knott, Kim. 2010b. Religion, Space and Place: The Spatial Turn in Research on Religion. Religion and Society: Advances in Research 1: 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niglio, Olimpia. 2025. Culture of The Sacred Space. In Advances in Science, Technology & Innovation (ASTI), Papers presented at the USAS 2022–2023, University of East London; University of Pisa, Italy. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palici di Suni, Elisabetta. 2019. La tutela delle minoranze linguistiche in Italia: Il quadro costituzionale e la sua attuazione. In Le lingue minoritarie nell’Europa latina mediterranea. Diritto alla lingua e pratiche linguistiche. Edited by Gianmario Raimondi and Dario Elia Tosi. Alessandria: Edizioni dell’Orso, pp. 79–92. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Vieytez, Eduardo J. 2021. Protecting Linguistic and Religious Minorities: Looking for Synergies among Legal Instruments. Religions 12: 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, Raymond Murray. 1994. The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World. Vermont: Destiny Books. [Google Scholar]

- Tsivolas, Theodosios. 2014. Law and Religious Cultural Heritage in Europe. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Vertovec, Steven. 2007. Super-Diversity and Its Implications. Ethnic and Radical Studies 30: 1024–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).