1. Introduction

Climate change is a global phenomenon with varying effects across different regions, which poses a significant threat to the survival and well-being of both human and non-human species. Climate change has rapidly increased since the 1800s due to anthropogenic activities, which are the main drivers of climate change. Furthermore, the burning of fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and gas is rapidly increasing ( the United Nations). Geographers, climate scientists, and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 2007 report on climate change have highlighted that an increase in anthropogenic activities will impact climatic conditions. Climate change effects are already visible, such as the increase in greenhouse gases (

Solomon et al. 2009) at the global level, resulting in the melting of glaciers, a rise in sea level, coastal erosion, an increase in droughts, famines and floods, a decrease in groundwater level, a change in rainfall patterns, and a fall in agricultural productivity and food security. Climate change has also affected species that have become extinct and others that are on the verge of disappearing. People, especially in impoverished communities including coastal communities and geographically low-lying and drought-prone areas, and living in developing countries (including India), are more vulnerable and severely affected (

Veldman et al. 2012).

Climate change has concerned humans since ancient times. However, in recent decades, debate on climate change has grown in academia due to the change in the atmosphere and its adverse impact on the planet (

Dove 2014). For the past two centuries, changes in climate have largely been due to human activities, such as rapid industrialization and the increased use of energy in modern times. Understanding human activities and cultures is crucial in addressing climate change. Climate change has cultural implications (

Crate 2011, p. 178) because culture influences people’s behaviours, which in turn affects their lifestyles. Religious beliefs and practices greatly influence human behaviour and ways of life, shaping the cultural dimensions of climate change (

Jenkins et al. 2018, pp. 85–86).

To effectively address climate change, it is essential to understand the local perspectives and approaches adopted by communities (

Rudiak-Gould 2014;

Kodirekkala 2018).

Altieri and Nicholls (

2017) argued that traditional agroecological strategies, such as biodiversification, soil management, and water harvesting, enable farmers to be resilient while also providing economic benefits, including climate change mitigation.

Misra and Bondla (

2010) examined the Konda Reddi and Koya tribal communities in South India, revealing cultural and religious dimensions of biodiversity conservation in their environment. The Konda Reddi community practices

podu (shifting) cultivation on the slopes and maintains crop diversity, which helps them sustain themselves in challenging climatic conditions (

Misra 2005;

Kodirekkala 2017). These conservation practices often integrate humans with plants and animals, playing a crucial role in combating climate change.

Hall and Chhangani’s (

2015) study among 19 villages, including Khejarli and neighbouring areas, found that approximately 37 per cent of community lands from 2007 to 2010 were occupied by blackbucks. The largest populations of blackbuck antelopes were located in three main villages, Khejarli, Guda Bishnois, and Bhaktasni, which are in close proximity. The Bishnois have long protected these blackbucks from poachers and predators. This commitment came to the forefront when Bollywood star Salman Khan was confronted by the Bishnois, who sought legal action against poachers following a hunting incident (

Hall and Chhangani 2015;

Jain 2011). Moreover, the Bishnois show concern for conserving local bird species, such as vultures, by providing nesting spaces in

Khejri (

Prosopis cineraria) and other indigenous trees they consider sacred. They refrain from cutting

Khejri tree branches in their agricultural fields and surroundings in order to shelter various species, especially birds (

Fisher 1997;

Brockmann and Pichler 2004).

Hall et al. (

2012) documented the Bishnois’ efforts to protect and conserve vulture species by facilitating nesting spaces. Furthermore, they provide

pani (water) sources in their agricultural fields and

chugga (grains) for various bird species through community-driven initiatives, reflecting their cultural practices and religious ethics.

Academic discussions and debates on religion and nature have taken place for a long time. However, the discourse on the concept of religion and ecology developed mainly after the article “The Historical Roots of Our Ecological Crises” by Lynn White in 1967 (

White 1967). He criticised Western religious traditions, particularly the worldview of Christianity, as significant contributors to environmental challenges. White’s assertions have ignited global discussions among scholars and religious figures (

Taylor 2016;

Taylor et al. 2016). The recent literature presents diverse perspectives on White’s thesis. In a comprehensive review of over 700 articles,

Taylor et al. (

2016) found that while “the thrust of White’s thesis is supported, the greening-of-religious hypothesis is not” (

Taylor et al. 2016, p. 1000). Conversely, White’s thesis has also faced criticism from various scholars (

Doughty 1983;

Tucker and Grim 1993 ;

Kochuthara 2010).

Various prominent members of the world’s major religious authorities and spiritual leaders have expressed their views on climate change, emphasising its moral significance within the framework of their faith. The World Council of Churches initiated a Climate Change Program in 1988. In 1990, the Buddhist spiritual leader the Dalai Lama delivered his first speech on climate change (

Jenkins et al. 2018, p. 91) and focused on individual spirituality. In 2009, Hindu spiritual leaders issued the “Hindu Declaration on Climate Change”, emphasising human responsibilities and calling for individual service to environmental welfare (

Jenkins et al. 2018, p. 91). In 2015, the “Interfaith Climate Statement” and the Parliament of World Religions meeting acknowledged that all faiths recognise the moral obligation to mitigate climate change (

Jenkins et al. 2018, p. 91). The “Islamic Declaration on Climate Change” criticised “big oil” and called for the role of the steward (khalifa) of the earth (

Jenkins et al. 2018, p. 91).

Scholars (

Tucker and Berthrong 1998;

Tucker and Chapple 2000;

Hessel and Ruether 2000;

Foltz 2003) of theology and religious studies have focused on the world’s religions and ecology for the past two decades. They stress the contributions of the world’s religious views to the conservation of ecology. Similarly, various scholars (

Tucker and Grim 2001;

Wolf and Gjerris 2009) have suggested that the world’s religions’ positive views can help challenge contemporary climate change. This is mainly because religions (organisations and leaders) address moral issues and environmental justice through their believers on a larger scale (

Veldman et al. 2012). However, there are critics of the world’s religions’ contributions to contemporary climate change issues because there are few reviews and data on the response of the world’s major religions to climate change (

Veldman et al. 2012). The world’s religions may spread awareness of climate change among religious followers, but it may be difficult at the practical level because of diversified ecological areas (

Bikku 2017).

For instance, the sacred groves of

Deve Bhoomi (abode or home of gods) in the Uttarakhand region of the western Himalayas illustrate the ecological and cultural significance of these areas. These groves are home to around 80 plant species across 75 genera and 44 families, many of which hold different kinds of economic and medicinal value, and they are actively protected by the local communities (

Singh et al. 2017, p. 2). Similarly, in the western region of Rajasthan, the Gujjar community practices the planting and worship of neem trees (

Azadirachta indica) as part of their religious tradition, believing that the worship of these trees honours their village deity, God Deonarayan. The Deonarayan Sacred Grove has thus become a sanctuary where the Gujjar people protect about 70,000 trees of varying ages and sizes across 600 settlements (

Pandey 1999, p. 4). These examples underscore the role of religious and cultural beliefs in promoting conservation efforts and preserving biodiversity through sacred spaces.

Macro-level studies generally dominate the academic discourse on climate change. In most cases, they tend to adopt a top-down approach, often neglecting the importance of understanding local environmental issues. While these macro-level studies are important, there is an urgent need for more micro-level studies to fill the gap between meta-narratives and local practices and ideas regarding climate change and initiatives for its mitigation and adaptation to their environment.

Therefore, there is a need to understand religion and climate change from the ecological area and community-level perspectives and their perception towards the environment. Owing to ecology-based religious beliefs, Indigenous knowledge, and worldviews, Indigenous or local religions also provide an integrated framework to follow conservation practices through a set of institutions to overcome climate change. It is essential to emphasise the cultural and, in particular, religious aspects of climate change adaptation and the ways various communities adapt to their environments (

Ramos-Castillo et al. 2017).

In this context, this paper delves into understanding the Bishnoi community’s adaptation methods and practices against climate change and how their religious beliefs and practices are shaping this adaptation for conserving biodiversity.

The Bishnoi Community and Their Religious Perspectives on Nature

The Bishnoi community primarily inhabits the Marwar region of western Rajasthan, with smaller populations spread over Haryana, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, and Madhya Pradesh. There are no official data on the Bishnoi community regarding its population in Rajasthan or India. Until the last 2011 census, no data were available on the census since Indian Independence. The community’s majority population is concentrated in western Rajasthan in the districts of Bikaner, Jodhpur, Jaisalmer, Nagaur, Pali, Ganga Nanagar, Hanum Garh, Barmer, etc., followed by Haryana, Madhya Pradesh, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, and Delhi. The Bishnoi population is estimated to be around one million in India (

Menon 2012 as cited by

Bikku 2017, p. 19).

The community was founded by Guru Jambheswar (1451–1536) in the 15th century A.D. The community worships Guru Jambheswar, who proposed 29 religious principles

1 that must be followed by anyone wishing to be considered a Bishnoi. The term “Bishnoi” is thought to be derived from the local words “

Bish” (twenty) and “

Noi” (nine), which together imply

Bish-nav (twenty-nine).

Maheshwari (

1976) suggested that the name Bishnoi means worshippers of Lord Vishnu, one of the major deities in Hinduism; during our interactions, many of the community members identified themselves as members of a distinct Bishnoi religion.

According to various sources (

Srivastava 2001), the Bishnoi community was established in the Marwar region to protect wildlife and other natural resources in the desert region. The Marwar region is in western Rajasthan, also called

Marusthal, which means deadland. Oral stories, narratives, and some modern writings from the Bishnois reveal a history of severe famines and droughts in the 15th century A.D. (

Crooke 1896;

Maheshwari 1976;

Landry 1990) that forced many people to migrate from Marwar towards other regions. Guru Jambheswar recognised the challenges posed by the desert climate and its impact on the inhabitants. In response, he developed solutions to balance ecological conditions through sustainable practices, which included the following 29 principles. Guru Jambheswar also initiated digging lakes and ponds (

nadi) in various locations, as well as creating tree plantations, particularly of the

Khejri tree. Today, lakes and ponds can still be found at numerous Bishnoi

Dhams (pilgrim sites). For instance, the Bishnois believe that Guru Jambheswar initiated

Jambholav Lake at Jambha village near Phalodi Tehsil in the Jodhpur district of Rajasthan. He inspired the desert inhabitants and people from various communities and religions to adopt these 29 principles, leading to the formation of the Bishnoi community.

The Bishnois believe that these religious principles offer solutions to the changing climatic conditions in their desert environment, helping to ensure their survival for generations. The Bishnois adhere to Guru Jambheswar’s sayings (vani), which emphasise the importance of good karma, rooted in compassion and kindness towards all life forms. For them, the Supreme Being resides in every living entity, and how we treat trees, animals, birds, and natural resources directly affects our karma. The core philosophy of the Bishnoi religion is, according to locals, jivo and jinedo, which means to live and let live, signifying that all living beings have the right to share the environment. The 29 religious principles, locally called Unatis niyam, focus on achieving salvation through conserving wildlife and natural resources. In this way, the Bishnoi faith intertwines the concepts of karma and survival, emphasising the ethical duty to protect the environment. This interdependence between human and non-human beings fosters a harmonious relationship, providing space for many species to thrive in the desert region.

As mentioned above, this paper delves into understanding how the religious beliefs and practices of the Bishnois shape their methods and practices against climate change. As the main focus of this paper is the Bishnois of Khejarli Village in the Thar Desert in Rajasthan, this paper also contributes to the broader academic discourse on the role of religious traditions in community-led biodiversity conservation, specifically in desert regions.

This paper examines the interaction between the people of the Thar Desert in Rajasthan and their environment, with special attention to the Bishnoi community’s relationship with nature. It emphasises the role of religious beliefs and practices in protecting and conserving local species, including animals, plants, and natural resources. Through this, this paper attempts to present a micro-level study that can provide additional solutions to contemporary climate challenges while exploring human perceptions of climate change and how these perceptions influence the discourses surrounding adaptation and sustainability in desert environments.

2. Methods

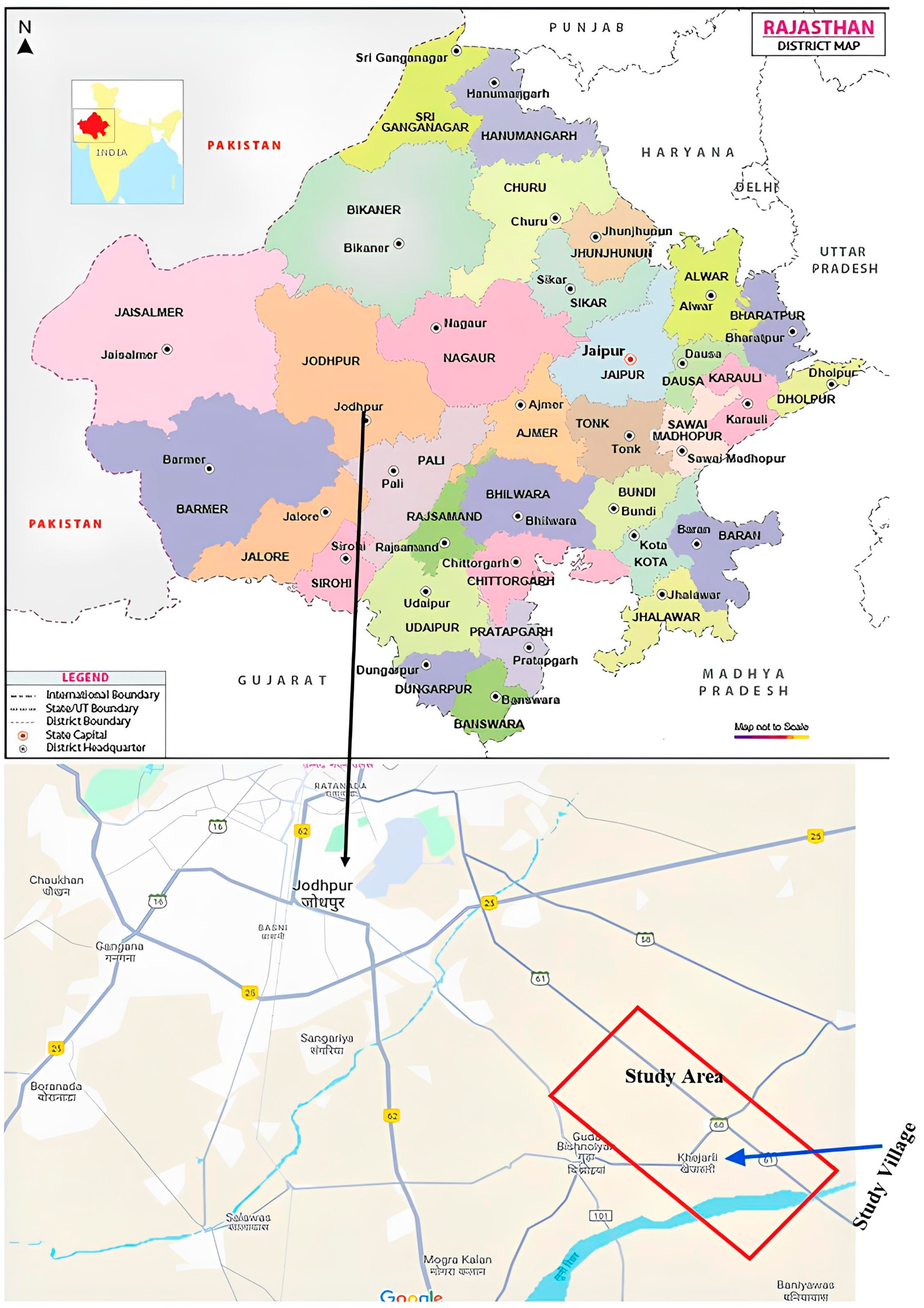

The selected field study area was chosen with the aim of investigating how the inhabitants of the arid desert region have maintained their livelihoods amid extreme climatic conditions, along with their interactive relationship with the evolving environment. Primary data were gathered from the Bishnoi community and other groups in Khejarli Village, situated in the Jodhpur district of western Rajasthan (see

Figure 1), as part of the researcher’s doctoral dissertation. Khejarli Village encompasses five additional hamlets, locally known as

Dhanis, which are dispersed over distances ranging from 1 to 6 km from the primary village. This ethnographic study was conducted in five distinct phases between 2012 and 2015, with each phase spanning 2 to 4 months, which included two rounds of pilot studies. In June and July 2024, the researcher revisited the area to observe shifts in the Bishnois’ religious beliefs and their adaptive responses to climate change over the preceding decade. The ethnographic research utilized participant observation, semi-structured interviews, focused group discussions (FGDs), and case studies to elucidate the interplay between religion and climate change.

The participant observation method was employed for an in-depth capture of the daily lives and practices of the Bishnoi community, particularly their interactions with local species—both domesticated and wild—and natural resources within the framework of their religious belief systems. This method was also used to elucidate the daily lifestyles and behaviours of the Bishnois regarding the protection and conservation of biodiversity and natural resources. By using this method, the author tried to explore their sustainable agricultural practices, water harvesting techniques, and efforts in animal husbandry and the protection of indigenous flora. Additionally, the approach facilitated an understanding of the socialisation processes among Bishnoi children, various life-cycle rituals, seasonal festivals, agricultural cultivation, and the conservation of Khejri trees and other native plants, all of which are underscored by religious practices aimed at biodiversity preservation and climate change mitigation. This observational method was further applied to understand the traditional Panchayat’s role concerning conservation practices.

The semi-structured interview method provided flexibility in collecting qualitative data while ensuring coverage of essential topics, including religious doctrines, folklore relating to community origins, and the underlying motivations for environmental conservation over the centuries. This interview method was employed to focus on the Bishnoi religious philosophy, its environmental implications, and how these conservation practices are perpetuated within the community. The semi-structured interviews were conducted with Bishnoi men, women, children, religious figures, and community leaders from various age groups to ascertain the roles of social, political, and economic institutions in the conservation of trees, birds, and animals crucial for their survival and sustainability. In-depth interviews with elders, religious priests, community leaders, and representatives from various Bishnoi conservation organisations were instrumental in documenting conservation initiatives and their effectiveness in mitigating and adapting to climate change.

Focused group discussion (FGD) was employed within the Bishnoi community to garner collective knowledge regarding biodiversity and natural resource management, capturing various opinions and group dynamics related to conservation practices. Within the context of climate change and religion, FGDs provided insight into community discussions around these pressing issues. This method also illuminated the communication of religious values in group environments and explored how individuals influence each other’s perspectives, particularly among different demographic segments such as elderly individuals, youth, and various community-based conservation groups.

Case studies were employed to capture information about various Bishnoi organisations and individuals who have significantly contributed to the conservation of regional wildlife, including animals, trees, and birds. The qualitative data accrued were analysed thematically.

In addition, quantitative data were collected through a household survey involving 554 households (213 of which belonged to Bishnois) to investigate various aspects including population demographics, occupational structures, household characteristics, educational levels, livestock ownership, and other relevant factors. Secondary data were critically analysed from journals, books, magazines, and newspapers to review the existing literature concerning the Bishnois in relation to themes of religion and ecology, as well as the nexus between religion and climate change.

3. Results

3.1. The Bishnois and Their Perceptions Towards Climate Change

Cosmological Knowledge and Bishnoi Religious Beliefs in Addressing Climate Change Impacts

Throughout human history, cosmology and religion have been closely interconnected (

Kragh 2020). However, since the Enlightenment, the significance of this relationship has received less attention. Despite this, anthropologists and sociologists have explored the connections between cosmology and religion in greater depth. Anthropologists attempt to understand the beliefs and worldviews of different communities, employing ethnographic methods to capture their cultural nuances (

Douglas 1963,

1996;

Abramson and Holbraad 2014). They view each culture as a unique way of understanding, adapting to, and interacting with its environment. As Geertz states, “cultural systems are broadly based on how people interpret the world around them” (

Pilgrim and Jules 2010, p. 3).

The peoples of the Thar Desert have faced numerous droughts and famines over the centuries. Both their historical experiences and environmental changes have led them to develop various mechanisms and predictions to mitigate the impacts of climate change. Regardless of their religion, caste, or tribe, these communities have established conservation practices to adapt to the harsh desert climate. In the field study village, it was observed that various sustainable practices had been followed by various caste groups, such as traditional water harvesting, using natural fertilizers in the agricultural field rather than chemical pesticides, etc. The researcher observed while interacting in the field with the Bishnois that the interconnection between the Bishnois’ religious beliefs and cosmological knowledge has played a vital role in helping them cope with droughts and famines in the Thar Desert region of Rajasthan. Their ongoing observations of natural elements—such as the sun, moon, heat waves, winds, stars, and clouds—and their behaviours towards the local wild and domesticated species, including plants, trees, animals, birds, and insects, enable them to predict climatic conditions. The constant interaction between the Bishnois and their environment, shaped by their values, knowledge, perceptions, worldviews, and belief systems, has deepened their connection to nature.

In the study area, the Bishnois and other farmers completely depend on the monsoon; thus, they practice rain-fed agriculture. They mostly cultivate food grains such as

bajra (pearl millet),

jawar, and

till (sesamum); different pulses such as cluster bean,

moong (green Gram),

moth bean (Phaseolus aconitifolius), etc.; and some commercial crops such as

soya bean, cotton, etc. The Bishnois use natural (organic) fertilizers, such as domesticated animal droppings locally called

gober, to make the land fertile and more productive. In the study area, Bishnois and non-Bishnois try to avoid or mitigate the use of pesticides and chemical fertilizers in crops (

fasal). They have an economic relationship with both the land and their spiritual connections to it. They worship agricultural land during cultivation and harvesting times. Over time, traditional ecological knowledge has evolved among the Bishnois. Bishnois’ traditional livelihood depended on agriculture;

Table 1 shows that 209 of 554 family members in Khejarli Village belong to the Bishnoi community, hold agricultural land, and follow agricultural practices. Only four families among the Bishnois in the study village were found to be agricultural-landless (

Bikku 2017). The Bishnois also keep domestication of animals, especially cows, buffaloes, and camels.

Apart from the Bishnoi community in the study village, there are other communities, such as the

Rajputs, who are traditionally princely communities, among whom some hold a large size of agricultural land. The Brahmins are a traditional priestly community involved in agriculture, business, and serving as priests in the village temples (

Bikku 2017). The

Jat community, though small in number, practices agriculture on all available agricultural land, and some households keep domesticated animals such as goats, buffaloes, and cows. There are also traditional service communities, such as

Nayi (barbers),

Sunar (goldsmiths),

Lohar (blacksmiths),

Sutar (carpenters), and

Darji (tailors), who hold less agricultural land and are primarily dependent on their traditional occupations. Among the Muslim community in the village, there are estimated to be four different occupational groups, including

Moila (potters),

Dhobi (washermen),

Teli (oilmen), and

Mirasi.

Mirasi group households belong to the traditional storytellers known locally as

Bhat for the

Raika/Devasi community. Some households from the

Moila and

Teli (oilmen) groups are able to continue their traditional occupations; however, many

Mirasi have given up their traditional roles and adopted new occupations, such as making plastic flowers and black garlands for trucks. The

Dhobi group has also transitioned away from their traditional work and engages in agricultural labour or has migrated to other cities and towns to pursue various occupations. The most marginalized communities in the village are the Dalits, also known as traditional Untouchables, including

Meghwal,

Harijans,

Shanshi/

Mochi (leatherworkers), etc., as well as the Bhil tribe. Some in these groups are marginal farmers, but most depend on agricultural labour or work as daily wage workers. Traditional pastoralists, known as

Devasi/

Raika, herd camels, goats, and sheep and follow seasonal agricultural practices. Some households migrate with their sheep to neighbouring states, such as Haryana, Delhi, and Uttar Pradesh, to graze their animals for 8 to 9 months of the year.

There is a need to develop various local ecological knowledge and strategies to mitigate the desert climate. There are several ways of understanding droughts and famines in the study area through wildlife behaviours and observing seasonal variations. During the interview, Harsukhramji Bishnoi, a 65-year-old member of the community, mentioned that the presence of dense fog (referred to as Kohara) during the daytime in the winter season serves as a predictor for rainfall. The expected volume of rainfall is believed to correlate with the intensity of the fog, which is anticipated to occur approximately six months later. Additionally, if the leaves of the Khejri tree fall and appear yellow (referred to as pilo), it is interpreted as a sign that rain will occur in the following month. Conversely, an abundance of fruit on the Khejri tree indicates minimal rainfall or potential drought in the upcoming monsoon season. These indications are connected with the traditional seasonal calendar, which helps the Bishnois to predict weather conditions in the near future. Changes in environmental conditions are observed from time to time, documented, and then cross-checked with the previous climatic conditions, which helps local people make predictions that are as accurate as possible. The traditional calendar guides them to celebrate festivals and rituals as well as plan for occupational activities through their understanding of environmental changes.

The religious festivals and agricultural practices of the community also feature their environmental cosmology, as these events and activities are deeply intertwined with their understanding of the natural world. One such agricultural festival is locally called Aka teej. According to Babulal Beniwal, who is 58 years old and from the community, on the day of the Aka Teej festival, the Bishnois and others, irrespective of their caste or tribe, gather at one place (in the middle of the village), and they attempt to make predictions about the coming monsoon through traditional practices. The Bishnois obtain indications from wild animals, birds, and trees, in addition to the sun, moon, heat waves, winds, stars, clouds, etc., about seasonal variations so that they can predict and manage their food grains and fodder for domesticated animals. Such knowledge and practices stemming from environmental cosmology help them manage and sustain their limited natural resources in the harsh climate.

The limited plant species available in the desert are properly managed and utilized by the desert people. It was observed in the study area that the Bishnois try to protect most plant species (Khejri, neem (Azadirachta indica), hari kankedi, jal (Salvadora persica), Rohida (Tecomella undulata), etc.) as part of their religious beliefs. In this process, most of the desert inhabitants try to use the cow or buffalo’s dung cakes (them) as cooking fuel and as a fire fuel instead of wood, except for the desi (wild) bambuliya (Vachellia nilotica) and Sarkari bambuliya (babul) bushes due to their rapid growth. The Bishnois bury their dead bodies instead of cremating them as they believe that this practice protect many trees in the desert region. These kinds of practices help create a balanced ecosystem in the desert area.

3.2. The Bishnoi Religion and Its Conservation Efforts for Wildlife

The twenty-nine principles clearly reflect the Bishnois’ concern towards animals and trees. Out of the 29 religious principles, about 5 are directly related to protecting species, both plants and animals. According to the 18th principle, a Bishnoi needs jeev daya palani or jeevu par dayakarna, which means “to be compassionate towards all living beings”. The 19th principle says Rukh leela nahi dhave or Haare vraksh nahi katna, which means “Do not cut the green patches, trees, or plants”. Similarly, the 22nd principle provides for a common shelter for goat/sheep. The 23rd principle says bail badiya nahi karna, which means “not to castrate bulls”, and the 28th principle binds them against eating meat or non-vegetarian dishes.

According to the 18th principle, a Bishnoi needs jeev daya palani or jeevu par dayakarna, which means “to be compassionate towards all living beings.” As Guru Jambheswar suggested, those who follow the 29 principles must conserve and protect both domesticated animals, such as cows, bail (bulls), unt (camels), bhains (buffaloes), etc., and jingli janwar (wild animals), such as kali Hiran (blackbucks), Neel Gais (blue cows), chinkara gazelles, Indian wolves, rare Indian wolves, hyenas, etc., and bird species such as Kurja (demoiselle cranes), Mor (peacocks), vultures, Indian and Hubara bustards, larks, pipits, Indian coursers, etc. There are several types of reptiles found in this region. These wild animals and birds are endangered species mostly found in the desert region of western Rajasthan.

The Bishnois try to protect ped and poda (trees and bushes), animals, and birds from natural disasters and human exploitation. They provide pani (water) and chugga (grains) to other wild animals and birds generally every season, mostly during summer. It was observed in the field area that most of the Bishnois have built nadi and talao (water tanks and small tubes) or have made small water storage areas in their agricultural fields to quench the thirst of wild animals and birds. They ensure that they use unt (camels) or modern vehicles to fill the tanks whenever the water level is reduced. They also provide everyday water (they keep water pots in front of the home or hang them on trees) and chugga (grain) to birds and animals either in front of their habitats or in village chabutra (where grains are fed to birds). During the harvest, the Bishnois also keep some portions of crops, locally called sandh-ghera, for wild animals and birds. As a part of their religious duty, on every Amavasya (No Moon night), the Bishnois of Khejarli Village visit the Amrita Devi temple and bring chugga (cereals) such as jowar and bajra (usually 2–5 kg or even more) to feed wild birds and animals. These practices are followed in most of the villages and their places of pilgrimage. Wild animals and birds contribute significantly to agricultural production, so they have a right to share-cropping.

Customary Laws and Protection of Wild Animals and Birds Among the Bishnois

The Bishnois’ religious values and practices forbid them from harming the surrounding wildlife. They have a close relationship with wild animals and birds; therefore, wild animals and birds fearlessly roam around Bishnoi habitations. Deer, blackbucks, peacocks, rabbits, Neel gayi, etc., are commonly found in their surroundings. This study found that the Bishnois take precautionary measures to protect wildlife in their surrounding environment. The Bishnois’ traditional Panchayat system is strong with regard to wildlife protection. They strictly follow their religious values and customary laws. The punishment for poaching in the Bishnois’ region is decided by the Bishnois’ Panchayat, i.e., whether poachers have to hand their catch over to the police or should accept the decision at the Panchayat level. The punishment depends on the nature of poaching and the acceptance of the poacher’s mistakes. Usually, punishment includes fines ranging from INR 10,000 to 51,000 and maybe more. The fine amount is used for the construction of water tanks and to buy grain for wild animals and birds or for planting trees.

3.3. The Bishnois and Conservation and Protection of Plants and Trees

The Bishnois have long practised the conservation of various plants and trees in their region, rooted in their spiritual relationship with nature. Their dedication towards preserving trees and plants has been influenced by their spiritual leader, Guru Jambheswar, beginning in the 15th century, as well as by climatic factors. This commitment is reflected in their religious principle number 19, which instructs the Bishnois

Rukh leela nahi dhave or hara vruksh nahi katana, which means “do not cut green trees or plants” (

Bikku 2017). According to the Bishnois from the studied village, Guru Jambheswar travelled to several places in India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan, encouraging people to plant trees, particularly indigenous varieties such as the

Khejri tree, and to protect them. The Bishnois believe that Guru Jambheswar personally planted 3600

Khejri trees around the village of Rotu in the Nagaur district of Rajasthan and urged the local inhabitants to safeguard these trees. During a visit to the village, the researcher interacted with the residents, who confirmed the presence of many

Khejri and other trees in the area. The Bishnois also hold the

vishwas (belief) that Guru Jambheswar planted

Khejri trees in Lodhipur, located in Moradabad district, Uttar Pradesh, among other places. He preached to the people about treating all living beings as equals to humans. As followers of Guru Jambheswar, the Bishnois strive to protect wild trees, particularly the

Khejri tree in western Rajasthan. This commitment to conservation is crucial for mitigating the harsh climatic conditions of the Thar Desert, where frequent droughts and famines lead to food and water shortages for humans and fodder scarcity for cattle. Protecting trees and green areas helps stabilize the region’s climatic conditions.

The Bishnois are concerned with conserving trees which are indigenous, especially

Khejri (

Prosopis cineraria) trees and other trees like

Rohida (

Tecomella undulate),

ja1 (

Salvadora persica),

Harikankedi,

Dhaman (

Cenchrus ciliaris),

Bordi (

Ziziphus nummularia),

kairiya (

Capparis decidua),

kumatiya (

Acacia senegal),

Gramna (

Panicum antidotale), and

Babool (

Acacia nilotica) (

Bikku 2017;

Kar 2014). In addition, the harsh, dry climate in the desert region makes them find peace with green trees. These trees provide not only shelter but also sheds and oxygen, and they cool the temperature. As observed in the research during the field study in 2014, between 25 and 30

Khejri and other trees are protected per hectare of land. During a recent visit in 2024, the researcher observed that indigenous tree numbers in agriculture have increased, finding at least 35 to 40 trees per hectare. The increase in the number of trees grown on the agricultural land within a decade is due to the Bishnoi farmers having started fencing their agricultural land, providing less possibility of exploitation of these trees/plants in the field. These trees provide economic and social security to the desert inhabitants during droughts and famines and in summer.

In western Rajasthan, the

Khejri tree, locally known as

Khejdi or

Kelada, holds significant cultural and ecological importance. The Government of Rajasthan designated it as the state tree in 1982-83. The Bishnois, a local community, emphasise the deep roots of the

Khejri tree, which reach the water table, enriching the soil and enhancing crop yields. This factor contributes to the prevalence of

Khejri trees in agricultural fields throughout the region. Remarkably resilient, the

Khejri tree can endure temperatures from as high as 45 to 48 degrees Celsius in peak summer to as low as 10 degrees Celsius in winter, adapting well to the harsh desert climate (

Bikku 2017). The

Khejri tree serves as a source of shelter for both people and wildlife, with each part of the tree proving useful resources for various consumption and ethno-medicinal applications. The fallen leaves enrich the soil, acting as natural fertilizer, while the tree itself casts light shade, helping retain surface moisture essential for crops. Its nutrient-rich leaves are utilized as fodder for domestic animals all year round. The Bishnoi community believes that the abundant

Khejri trees in their fields contribute to improved soil fertility and higher agricultural productivity. Additionally, the

Khejri tree yields nutritious pods, known locally as

Sangri and

Kho-kha (dried

Sangri), which are a vital food source for the community. These green

Sangri (pods) and

Kho-kha (dried

Sangri) are consumed in curries, and the dry

Sangri (pods) are stored for future use.

Sangri and

Kho-kha (dried

Sangri) are nutritious and highly sought after in local markets, priced between INR 200 and 300 per kilogram. The health benefits of

Sangri pods can be used to prevent mineral deficiency (

Bikku 2017).

Another significant tree in this region is

Kher (

Capparis decidua), locally referred to as

Kheria. As mentioned by the Bishnois, “these grow along with other small plants. They said that during famines,

Kheria fruits provide a source of diet. This tree survives by consuming less water and provide good vegetation for the local people, animals, and birds during summer” (

Bikku 2017, p. 160). The Bishnois state that during times of famine,

Kheria fruits become a vital food source, demonstrating the tree’s adaptability as it requires minimal water while providing sustenance for local communities, animals, and birds during the hot months (

Bikku 2017). The green Kher fruits are not only turned into

achar (pickle) but also cooked and enjoyed as vegetables. Often prepared alongside the fruits of the

Khejri tree, they are utilized in local cuisine. In the Thar Desert, these trees play a role in agroforestry, which helps increase the production of crops in rain-fed agricultural regions. Agroforestry is considered an efficient system in the utilization of land and water and helps in sustained biomass production in arid and semi-arid regions.

They explain that birds and wild animals live on and under the trees. The Bishnois’ concern is not limited only to plants and animals but also encompasses small insects. It is observed that in the study area, the Bishnois thoroughly shake fire fuel (firewood) and thepadi (cow dung cake) before putting it in the fire so that no insect loses its life in the process. They serve the first part of the daily food (the first roti prepared) to dogs, the reason being that dogs should not be forced to remain hungry or to kill any other bird or animal. These kinds of practices clearly reflect the 18th principle among the Bishnois. In fact, in the month of Shravan Bhadu, the Bishnois of Khejarli Village prepare laddu (sweet item) for dogs. This is known as the dog festival. On this occasion, the Bishnois collect grain and money from all members of the community, and rotis and laddus are prepared. These are fed to the dogs of the village and surrounding villages. This custom is practised daily, one village at a time, by each village. They believe that if they feed the dogs, there will be good rainfall in the coming season. The reason for choosing dogs is that they will not attack the wild animals in their region, especially blackbucks and Chinkaras. The Bishnois are conscious of the need to protect wild animals and birds from domesticated animals like dogs.

The religious principles of the Bishnois serve as a guiding force in their daily lives. Whenever there is a threat to the lives of wild animals, such as deer, foxes, blue cows (

Neelgai), and rabbits, or when trees in their area are being cut down, the Bishnois act swiftly to protect them. Many members of the Bishnoi community have even sacrificed their lives for the sake of wildlife and trees. A notable example of this commitment occurred in 1730 A.D

2. in Khejarli Village, located in the Jodhpur kingdom. During this incident, it is estimated that 363 Bishnois sacrificed their lives by embracing

Khejri trees to prevent them from being felled. This site is now locally known as Sahid Sthal (martyr’s place) and is well remembered among the Bishnoi people. They constructed a memorial to honour the 363 martyrs and the temple of Guru Jambheswar. In the field study, it was observed that the Bishnois celebrate the 363

Sahid Mela (Martyr Fair) twice a year at a high level, participating in and attracting participants from all over India, including both Bishnois and non-Bishnois. During this fair, the temple receives large donations of grains and ghee (clarified butter) from devotees. The grains are fed to wild animals and birds daily, while the ghee is used to light lamps. At the

Mela, Bishnois individuals also engage in raising awareness about the importance of protecting wildlife in the region. In memory of the 363 martyrs, the Bishnoi

Mela committee distributes

Khejri and other plants to devotees free of charge, encouraging them to plant and care for these trees. The Bishnois have actively planted a variety of trees, predominantly

Khejri, at the martyrs’ site. Notably, the world-renowned Chipko movement in the Himalayan region was inspired by the Bishnois’ environmental activism (

Shiva 1988;

Bahuguna et al. 2007).

The case against popular Bollywood film star Salman Khan for the killing of two blackbucks in Bishnoi territory in 1998 is also a pointer in the direction of their concern for the environment and its ecology. In January 2014, a young farmer, Saitan Singh Bishnoi (aged 25 years), sacrificed his life while stopping poachers from killing Chinkaras in Phalodi Tehsil of the Jodhpur district in Rajasthan (

Times of India 2014).

3.4. Socialisation Process Among the Bishnoi Children and Their Perspective Towards Climate Change

Children from the Thar Desert are generally aware of the region’s climate conditions and consequences. The importance of conserving species and implementing mitigation strategies for climate change is deeply integrated into their religious beliefs and practices. Through socialisation, Bishnoi children are taught how to adapt to the harsh climates they experience during different seasons. The Bishnoi community places great emphasis on ensuring that their children learn about environmental stewardship and develop a strong connection with local trees, plants, domesticated and wild species, and other natural resources. Their religious beliefs and daily practices are intertwined, fostering a sense of responsibility toward the environment from a young age. Children observe and emulate the behaviours of their parents, siblings, friends, and community members regarding the treatment of both domesticated and wild species. They learn alongside their parents how to feed grain to wild animals and birds and provide them with water. Additionally, they are instructed on how to plant indigenous trees, such as

Khejri, in their agricultural fields and understand their benefits. The community’s commitment to wildlife protection is also emphasised. Ruki (55 years) is from Bishnoi-Ki-Dhani in Khejarli Kalan and is engaged in agriculture activities. She said her grandchildren feel happy if

chugga (grains) and water are fed to the birds and animals. Such hospitality is a part of the Bishnois’ tradition that no visitor to a Bishnoi habitation should leave hungry and thirsty (

Bikku 2017). The village has a notable history, including the sacrifice of 363 Bishnoi individuals who gave their lives to protect

Khejri trees. In the village, children’s play activities often reflect the lives and contributions of community legends regarding tree protection. A prominent example is Amrita Devi, the first woman from the community known for her sacrifices in the protection of trees in the 1730s, who is celebrated in the primary educational curriculum focusing on Khejarli Village sacrifices.

As part of their daily life, the Bishnois have been concerned about their environment for centuries. Parents and elderly people from the community have a prime concern for and duty to teach the new generation about the conservation and protection of species in the region, as mentioned by one of the elderly people from the Bishnoi community from the village of Birmaram Beniwal (aged 80 years): “There is a need to teach children about the importance of natural resources and how to protect them, and how to utilize them systematically. This will help the next generation avoid natural resource scarcity.” (

Bikku 2017, p. 119). He also mentioned that if we are not protecting

ped,

podha, and

janwar, and

pakshi (trees, plants and animals, and birds), it would be exceedingly difficult to survive in the region. Therefore, they have equated wild species with their religious ethos. As the Bishnoi practices includes various festivals, fairs, and life-cycle rituals, they connect with the protection of wildlife and teach their children the importance of the environment. Thus, Guru Jambheswar’s teaching of environmental protection became important to the Bishnois, and these teachings have been passed from generation to generation.

The researcher observed in the field study that the Sugra Sanskar is an important life-cycle ritual that is performed when children reach the age of 12. During this ceremony, Sadhus (religious priests), who act as religious teachers, impart knowledge to Bishnoi children about environmental conservation and the significance of the teachings, specifically the 120 Sabdvani (sayings) of Guru Jambheswar. The children are encouraged to make a lifelong commitment to uphold these principles and protect wildlife. In the field study, the researcher observed that many Bishnoi children are familiar with the religious doctrines that emphasise the importance of conserving plants and animals. These children can recite at least 20 of the 120 Sabd sayings on average. Some of these sayings specifically address the need to safeguard the environment, including wild species and natural resources. The community believes that the Sugra Sanskar is essential for every Bishnoi child, as by the age of 12, they have developed enough understanding and maturity to respect and continue the conservation traditions. From a young age, these children learn about the environment, enabling them to recognise various animals, birds, trees, and plants. They also possess knowledge of seasonal fruits such as Sangri from the Khejri tree and others like the Boldi and Peelu of meethi jal (Salvadora tree).

3.5. The Bishnois’ Organisations Working Towards Mitigating Climate Change

The Bishnois provide water and chugga (grains) to wild animals and birds and allow them to move freely in the surrounding areas. All the Bishnoi individuals ensure that wild animals and plants are protected from poachers and tree fellers. Apart from community-level conservation practices, some individuals and groups from the Bishnois have formed groups or organisations that have been working for the past several decades.

3.5.1. The Akhil Bhartiya Bishnoi Maha Sabha (ABBMS)

Different organisations and individuals work to raise environmental awareness and try to continue their traditional conservation practices. The Akhil Bhartiya Bishnoi Maha Sabha (ABBMS) is a national-level community organisation established in 1936 that aims to protect Bishnoi culture and traditions, conserve the environment, protect wildlife, and promote Bishnoi religious values. As one of the oldest organisations dedicated to community and environmental issues, the ABBMS has members working at various levels, such as state, district, tehsil (block), and village. This organisation has successfully engaged in political negotiations. It has spread awareness about the Bishnoi religious ethos and teachings of their founder, Guru Jambheswar, which emphasises the conservation of wild species. To build awareness of community heroes in history who sacrificed their lives to protect wild species and their religious ethos towards the environment, the ABBMS conducts state- and regional-level exams for students from both Bishnoi and non-Bishnoi communities. The organization conducts tests for students from the sixth to twelve classes, or standards. In this exam, the ABBMS gives first, second, and third prizes as a competition. In this competition exam, boys and girls are confident. In interviews with ABBMS members at their pilgrimage place, called Muktidham Mukam, in Rajasthan, they said that “the world has just awakened and concern about the environment and climate change, but the Bishnois have been concerned about the environment and climate of that desert for centuries, and they have been sustaining in harsh climate conditions by co-existing with different species”. The Bishnois’ contributions have not been widely recognised on a global level.

3.5.2. Akhila Bharatiya Jeev Raksha Bishnois Sabha (ABJRBS)

In addition to the (ABBMS), several other organisations and groups operate at national, state, and regional levels, focusing on wildlife protection and the conservation of natural resources. Some well-known organisations include the Akhila Bharatiya Jeev Raksha Bishnois Sabha (ABJRBS) and the Bishnoi Tiger Force (BTF). Both the ABJRBS and BTF operate at the national level and are active in the states of Rajasthan, Haryana, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, and Madhya Pradesh, working to protect wildlife and raise awareness.

The ABJRBS, formerly known as

the Jeev Raksha Bishnoi Sabha (JRBS), was established in 1974 by Santh Kumar Raad and other prominent wildlife protection activists from the Bishnoi community. The organisation quickly gained national and international recognition for its dedication to wildlife conservation and its promotion of Bishnoi religious doctrines, which emphasise the philosophy of

jivo and jeendo, which means “live and let live” (

Bikku 2017, p. 142). At the district level, non-Bishnoi individuals also participate as active members in efforts against poaching and deforestation.

The researcher interviewed some well-known individuals, namely, Ranaram Bishnoi (70), Khamuram Bishnoi (50), Dolaram Beniwal (50), Mokram Dharnia (55), and Vinod Kadvasara (35), who were working at the district and state levels in Rajasthan and Haryana during the fieldwork. Environmental activist Vinod Kadwasara (aged 35) and state ABJRBS president Rameshwar Delu (Comrade) (aged 65) reported that several blackbucks and blue bulls (Neel Gais) had suffered injuries, with some dying due to fencing erected by the Nuclear Power Corporation of India Limited (NPCIL) in the Gorakhpur and Fatehabad districts of Haryana. The ABJRBS opposed this fencing, which covers 125 acres of land in the Bodapal area, encroaching on the natural habitats of blackbucks and blue bulls. Researchers visited the natural habitat site and observed that a large group of blackbucks and blue bulls struggled with their movements, forcing them into agricultural fields. The ABJRBS has been actively working to protect wildlife in various regions and has initiated several similar movements. In recognition of its contributions, the organisation received the Indira Gandhi Paryavaraṇa Award. The governments of Rajasthan, Punjab, and Haryana have also recognised the efforts of the ABJRBS.

3.5.3. The Bishnoi Tiger Force (BTF)

The Bishnoi Tiger Force (BTF) was founded by Rampal Bhavad and other members of the Bishnoi community from Jodhpur, Rajasthan, in 1998 and 1999. Key members included Ram Nivas, Ramnivas Dholu, Omprakash Godhara, Ramu Ram, and Omprakash Koth. The organisation became a registered NGO in 2007. Since its inception, the BTF has focused on the protection of trees, especially the

Khejri tree, as well as the conservation of wild animals and birds. Additionally, it promotes the community’s religious principles, such as “Jeev Daya Palani,” which means “to be compassionate and kind to all beings,” and “

Rukh Lila Nahin Ghave” or “

Haare Vraksh Nahi Katna,” meaning “do not cut down green trees and patches” (

Bikku 2017, pp. 94–95). The BTF primarily operates in western Rajasthan, where it rescues wild animals and birds, such as blackbucks, Neelgais (blue bulls), and peacocks. Since the BTF’s formation, numerous individuals from the Bishnoi community and other communities have voluntarily participated in protecting these species. It is estimated that the BTF currently has around 4000 to 5000 individuals involved in its efforts. Due to a ban on poaching and tree cutting in western Rajasthan, where the Bishnoi population is high, the region has a larger number of wild species.

Various national, state, and regional organisations collaborate with volunteers from both the Bishnoi and non-Bishnoi communities. Some of these groups also collaborate with forest departments. In addition to these organisations, several individuals are actively working for the environment, including Ranaram Bishnoi, known as the “Tree Man of the Desert”, and Khamuram Bishnoi (

Bikku 2017). Khamuram Bishnoi, a 57-year-old member of the Bishnoi community from the Jodhpur region, has been raising awareness about plastic pollution and advocating for the use of jute bags instead. He leads a team of nearly 100 volunteers who participate in local fairs known as

Melas (local fairs). During a conversation with the researcher, Khamuram shared that he has been invited by various universities and institutions in France and other European countries to raise awareness about environmental protection and the Bishnoi philosophy, which emphasises a strong concern for nature. He has also been honoured and recognised by Bishnoi associations, the state government, and educational institutions and universities in India (

Bikku 2017, pp. 186–87).

4. Discussion

The above ethnographic study shows that local religious belief systems and knowledge have shaped the relationship between people and their ecology. This study focused on religion and ecology, which are closely tied to the local climatic conditions. This complex relationship between the Bishnois’ social, economic, cultural, and religious institutions and their environment has enabled them to be resilient and adapt to climate change. There are other examples, for instance, the Hopi Indians from the deserts of Arizona, United States of America, cultivate a variety of crops, including indigenous plants such as corn, beans, and squash (

Ford 1981). Their agricultural methods, including arid farming and corn cultivation, are central to Hopi identity. These physical and spiritual practices support their existence in the desert (

Soleri and Cleveland 1993;

Wall and Masayesva 2004). Similarly, the Maasai pastoralists of Eastern Africa often regard certain lands and wildlife as sacred, a belief that plays a crucial role in integrating their traditional knowledge systems with spiritual practices. This integration allows them to effectively manage grazing land and conserve various species (

Homewood and Rodgers 1984;

Oduor et al. 2015). The Bishnois’ community, environmental ethics, customary laws, and other local agricultural practices play a significant role in protecting biodiversity and sustaining life in the arid region. The Bishnoi community’s traditional political institution is locally called the Panchayat, which plays a vital role in implementing conservation rules and regulations to protect wild species from exploitation. The Panchayat imposes fines in the form of cash or

chugga (grain) (or sometimes both) if someone is caught poaching blackbucks or felling

Khejri trees in their region. Socio-religious institutions within the community have regulations governing behaviour and activities, which further motivate the Bishnois to maintain a strong relationship with both their community and the local environment. The prediction of climatic conditions among Bishnois has tremendous value because through the prediction, they can arrange food and other resources for themselves as well as

chara (fodder) and

pani (water) for animal species.

The Bishnois’ religious beliefs and collective efforts for the conservation of wildlife and natural resources provide them with a strong foundation to address contemporary climate change in their desert region. A total of 5 (the 18th, 19th, 22nd, 23rd, and 28th) out of their 29 religious principles are directly related to the conservation of various species, and the Bishnois adhere to these doctrines, which are essential for their survival in harsh climates. The protection and conservation of species have long been integral to the Bishnois’ way of life, and they are committed to ensuring that future generations continue these traditions. The Bishnois’ religious doctrines of the 18th and 19th principles say to “be compassionate towards all living beings” and “do not cut trees or green patches”, directing them towards the conservation and protection of various species. They teach their children how to plant and protect trees in agricultural fields and other areas. Additionally, they educate their children on how to coexist with wild animals and birds. The Sugra Sanskar, a life-cycle ritual among the Bishnois, serves to raise awareness about their heritage and responsibilities. Through these practices, Bishnoi children learn the importance of protecting local species and natural resources. The close relationships between animals and plants foster a sense of responsibility in them, encouraging ongoing conservation efforts and helping to combat climate change.

A recent visit to the study village revealed that the Bishnoi youth have united to form an environmental protection group, spreading awareness among the young people in the region. During discussions with Raju Bishnoi, Rajesh Beniwal, and others, it became clear that these young Bishnois are actively involved in planting hundreds of trees and protecting local wildlife, particularly blackbucks, from poachers. The Bishnoi youth and children also play a significant role in organising a Mela (fair) in the village, where they promote awareness about the harmful effects of plastic use and distribute saplings to attendees. This dedication to wildlife conservation not only helps protect the environment but also contributes to mitigating climate change. These kinds of practices help the Bishnois to reenforce their conservation practices and ecological knowledge in the protection of trees in the region.

The Algonkian people of eastern Canada and the northeastern United States have a significant connection with game animals, which is reflected in their religious rituals of “Animal Ceremonialism” (

Hultkrantz 1981, p. 120). These animal ceremonies help prevent overhunting and foster a strong association between the community and animals, ultimately promoting the protection and conservation of species in their natural habitats (

Martin 1980;

Hultkrantz 1981). Similarly, the Bishnois’ religious beliefs and knowledge foster a reciprocal relationship with local species through various festivals and ceremonies, where the Bishnois engage with one another and raise awareness about climate issues. Folk festivals and

Melas (fairs) serve as platforms for interaction among Bishnois from different regions. During the

Mela, they remember the 363 martyrs, known as

Sahid Sthal (martyr place), from Khejarli Village, where a significant incident occurred in the 1730s. Many Bishnois sacrificed their lives to protect the

Khejri trees and other local vegetation. At the

Mela, the Bishnois emphasise the importance of wildlife protection and climate change, which are particularly relevant in the desert region. In honour of these martyrs, the Bishnoi

Mela committee distributes

Khejri and other local plants for free to attendees, encouraging them to plant and protect these trees. The Bishnois continue their efforts to make the desert region more sustainable and help mitigate climate change.

The Bishnois’ oral literature provides inputs to continue their traditional beliefs and practices in the desert’s climatic conditions. The increased awareness and concerns about various environmental issues and climate change phenomena are of recent origin. However, the Bishnoi community has been sustained in the harsh desert climate, as have neighbouring peoples, for centuries. Various mechanisms have been adopted, developed, and modified to mitigate the suffering of people from the adverse effects of climate change. The social structure also plays an important role among people, which creates a symbiotic relationship with their environment.

Traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) systems have been important among local and Indigenous communities and play a pivotal role in conserving, protecting, and managing the natural environment. TEK encompasses a comprehensive body of knowledge, beliefs, rules, codes of behaviour, institutions, worldviews, and practices that continuously interact between local or Indigenous communities and the natural environment (

Toledo 2002;

Berkes 2004,

2008). The application of TEK by these communities not only ensures their livelihoods (

McDade et al. 2007;

Reyes-García et al. 2008) but also contributes to the maintenance of biodiversity and the health of ecosystems (

Gadgil et al. 1993;

Reid et al. 2006). The application of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) in

podu (shifting) cultivation on slopes by the Konda Reddi and Koya tribal communities in South India helps preserve crop diversity, which is crucial for sustaining their livelihoods amid increasingly challenging climatic conditions (

Misra 2005;

Misra and Bondla 2010;

Kodirekkala 2017). Similarly, an in-depth study of Bishnois’ religious views and their perceptions and practices towards their local environment reveals that local knowledge (traditional ecological knowledge), including local religious beliefs, has effectively mitigated climate change in the region. The local knowledge and practices initiated by their religious ethics have helped the Bishnois conserve and protect their environment for centuries. Bishnoi religious beliefs are expressed through rituals, ceremonies, festivals,

Melas (fairs), and various social gatherings. Such practices foster close relationships within the community and connect individuals with their environment. As these practices become ingrained in the community’s customs, they help develop respect, compassion, care, fearlessness, and a spiritual bond with the natural world.

During the recent field visit, the researcher observed that while initiatives taken by the Bishnois have yielded positive outcomes, they have also introduced new challenges. One significant issue identified was the increasing usage of fencing around agricultural lands to protect crops. As previously discussed, the Bishnoi community in the region has a deep cultural and spiritual connection with hirans (blackbucks) and other wild animals and birds, exemplified by traditions such as women breastfeeding orphaned fawns and allowing antelopes to move freely near human settlements. When asked about the necessity of fencing agricultural lands, two elderly Bishnoi men explained that it was primarily for safeguarding farmland from other domesticated animals like cows and buffaloes. Furthermore, conversations with three other male (middle-aged) community members revealed that the recent rise in land prices has intensified the desire to protect one’s property. This evolving dynamic highlights a shift in land-use priorities, where traditional coexistence with wildlife is increasingly challenged by the economic value attributed to land.

Another notable observation was the establishment of a government-run wildlife rescue centre in Khejarli Village, which significantly influences how people interact with wildlife. Traditionally, Bishnois and wildlife enthusiast tourists have visited the area to observe wildlife in open fields and forests. For the Bishnois, interacting with wildlife in its natural habitat is essential for passing down ecological knowledge and coexistence practices to younger generations. However, the rescue centre, which provides medical care and rehabilitation for injured animals, has now become one of the primary sites for wildlife interaction for both tourists and local communities, including the Bishnois. This shift may disrupt traditional ecological learning, as younger generations might become less familiar with wildlife in natural habitats, potentially hindering their ability to continue traditional practices and methods for environmental conservation—practices that are vital in the face of climate change and its impacts.

The fencing of agricultural lands combined with the rescue centre’s role as a site of interaction between animals and humans could further impact endangered species like blackbucks. Additionally, this shift could commercialize interactions between humans and animals, altering the community’s traditional conservation practices and methods. According to

Hall and Chhangani (

2015), approximately 37 percent of community land in 19 villages in the area was occupied by blackbucks. However, the construction of government infrastructure projects, such as hospitals, rescue centres, and playgrounds, exacerbates environmental and resource management challenges. Lands that previously served as shared spaces for both domestic livestock and wild animals to graze and roam freely are now being affected because these infrastructure projects are situated on common grazing lands. These communal grazing lands are also vital for community members, as they historically provided bushes and vegetation used as fuel sources. Consequently, recent infrastructural projects have made these natural resources scarcer, impacting both the community and the local wildlife.