The Interactive Relationship and Influence Between Kitchen God Beliefs and Stoves in the Han Dynasty (202 BCE–220 AD)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Exploring the Cultural Relationship Between Stoves and the Kitchen God from the Chinese Character “竈”1 and Its Vocabulary

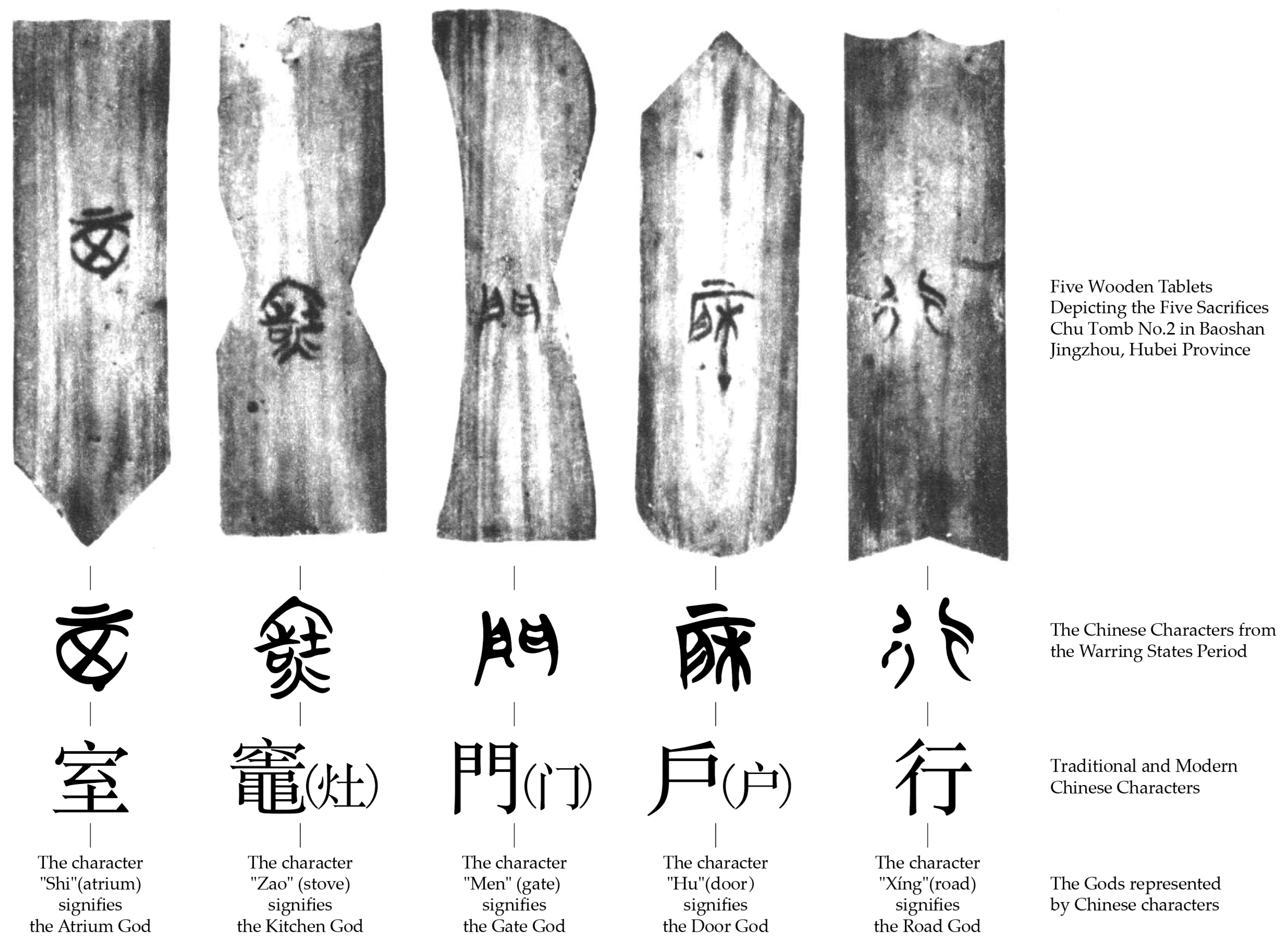

(竈) in the region of the Chu State. This evidence suggests an increasingly explicit relationship between the Kitchen God and stoves, as demonstrated by the archaeological findings in the Baoshan No. 2 Tomb from the Warring States period in Jingmen, Hubei, in which a total of five wooden tablets were unearthed (Hubei Jingsha Railway Archaeological Team 1991, p. 156). The wooden tablets are inscribed with five Chinese characters, which can be read and translated as follows: “室” (Shi Atrium), “戶” (Hu Door), “門” (Men Gate), “行” (Xing Road), and “

(竈) in the region of the Chu State. This evidence suggests an increasingly explicit relationship between the Kitchen God and stoves, as demonstrated by the archaeological findings in the Baoshan No. 2 Tomb from the Warring States period in Jingmen, Hubei, in which a total of five wooden tablets were unearthed (Hubei Jingsha Railway Archaeological Team 1991, p. 156). The wooden tablets are inscribed with five Chinese characters, which can be read and translated as follows: “室” (Shi Atrium), “戶” (Hu Door), “門” (Men Gate), “行” (Xing Road), and “ ” (Zao Kitchen Stove) (Figure 4). The wooden tablets exhibit a variety of shapes, each representing a specific deity: the Atrium God, the Door God, the Gate God, the Road God, and the Kitchen God. These five gods have been prevalent since the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE). The Chinese character “

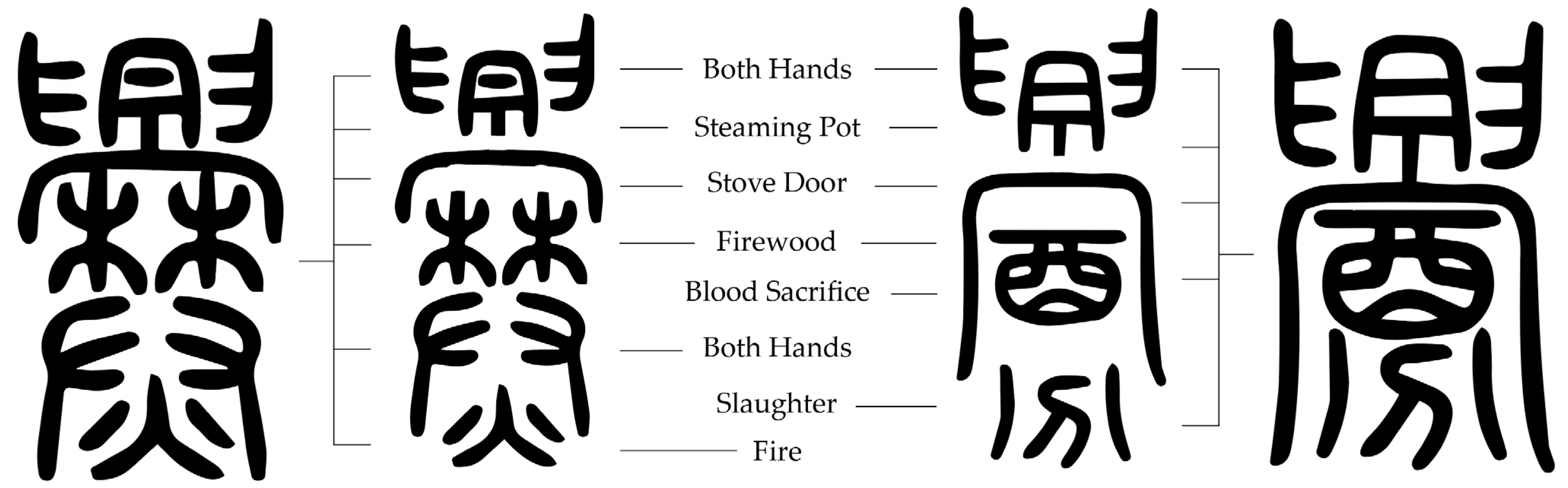

” (Zao Kitchen Stove) (Figure 4). The wooden tablets exhibit a variety of shapes, each representing a specific deity: the Atrium God, the Door God, the Gate God, the Road God, and the Kitchen God. These five gods have been prevalent since the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE). The Chinese character “ (竈)” is composed of four distinct Chinese characters, arranged from top to bottom. The character “∧” is used to represent a roof structure in buildings; “告” signifies a sacrificial ritual in which a cow is offered as a sacrifice and placed in an object prepared for presentation; “土” may be interpreted as the material used to construct the stove; and “火” represents the burning flames within. The Chinese character “

(竈)” is composed of four distinct Chinese characters, arranged from top to bottom. The character “∧” is used to represent a roof structure in buildings; “告” signifies a sacrificial ritual in which a cow is offered as a sacrifice and placed in an object prepared for presentation; “土” may be interpreted as the material used to construct the stove; and “火” represents the burning flames within. The Chinese character “ (竈)” provides a comprehensive visual representation of a real-life scene in which a cow is burned by fire as a sacrificial offering within a designated space. The wooden tablets were identified as burial objects and discovered in conjunction with the headdresses that were used on a daily basis. This indicates that by the Warring States period at the latest, the Kitchen God was regarded as a significant entity in the Chu State, with offerings made to it both during one’s lifetime and after death. The Chinese character “竈” acquired the dual meaning of the Kitchen God and stove, thereby reinforcing the intrinsic connection between spiritual belief and material culture.

(竈)” provides a comprehensive visual representation of a real-life scene in which a cow is burned by fire as a sacrificial offering within a designated space. The wooden tablets were identified as burial objects and discovered in conjunction with the headdresses that were used on a daily basis. This indicates that by the Warring States period at the latest, the Kitchen God was regarded as a significant entity in the Chu State, with offerings made to it both during one’s lifetime and after death. The Chinese character “竈” acquired the dual meaning of the Kitchen God and stove, thereby reinforcing the intrinsic connection between spiritual belief and material culture. (竈)”, which have been interpreted as a reference to the ritual sacrifice with a stove (Hubei Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology 1995, pp. 80, 103). The characters “祭

(竈)”, which have been interpreted as a reference to the ritual sacrifice with a stove (Hubei Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology 1995, pp. 80, 103). The characters “祭 (竈)” bear a striking resemblance to the characters “

(竈)” bear a striking resemblance to the characters “ (竈)” unearthed from the Baoshan No. 2 Tomb, with the exception of the character “示”, which denotes the table utilized in a sacrificial ritual for the presentation of offerings (Figure 5). The characters “祭

(竈)” unearthed from the Baoshan No. 2 Tomb, with the exception of the character “示”, which denotes the table utilized in a sacrificial ritual for the presentation of offerings (Figure 5). The characters “祭 (竈)” on the bamboo slip provide direct evidence of the practice of sacrificing to the Kitchen God, which was prevalent in the Chu State region during the Warring States period. In comparison to the character “竈” during the Spring and Autumn period, the two Chinese characters with the same meaning used in the Chu State during the Warring States period evince a stronger religious connection and place greater emphasis on the significant role of stoves as heaters. Therefore, these two Chinese characters linked to stoves are highly likely to be the exclusive characters of the Kitchen God. The character “竈”, which dates from the Spring and Autumn period, was continued to be used during the subsequent Qin (221–207 BCE) and Han (202 BC–220 AD) periods, as evidenced by the currently available literature and archaeological discoveries. The reasons why the characters associated with the Kitchen God and stove were not disseminated and used extensively outside of the Chu State remain unclear. Further archaeological data and research may help to elucidate this enigma, thus providing a greater understanding of the historical context.

(竈)” on the bamboo slip provide direct evidence of the practice of sacrificing to the Kitchen God, which was prevalent in the Chu State region during the Warring States period. In comparison to the character “竈” during the Spring and Autumn period, the two Chinese characters with the same meaning used in the Chu State during the Warring States period evince a stronger religious connection and place greater emphasis on the significant role of stoves as heaters. Therefore, these two Chinese characters linked to stoves are highly likely to be the exclusive characters of the Kitchen God. The character “竈”, which dates from the Spring and Autumn period, was continued to be used during the subsequent Qin (221–207 BCE) and Han (202 BC–220 AD) periods, as evidenced by the currently available literature and archaeological discoveries. The reasons why the characters associated with the Kitchen God and stove were not disseminated and used extensively outside of the Chu State remain unclear. Further archaeological data and research may help to elucidate this enigma, thus providing a greater understanding of the historical context.3. The Interactive Integration of Stove Design and the Kitchen God Belief in the Han Dynasty

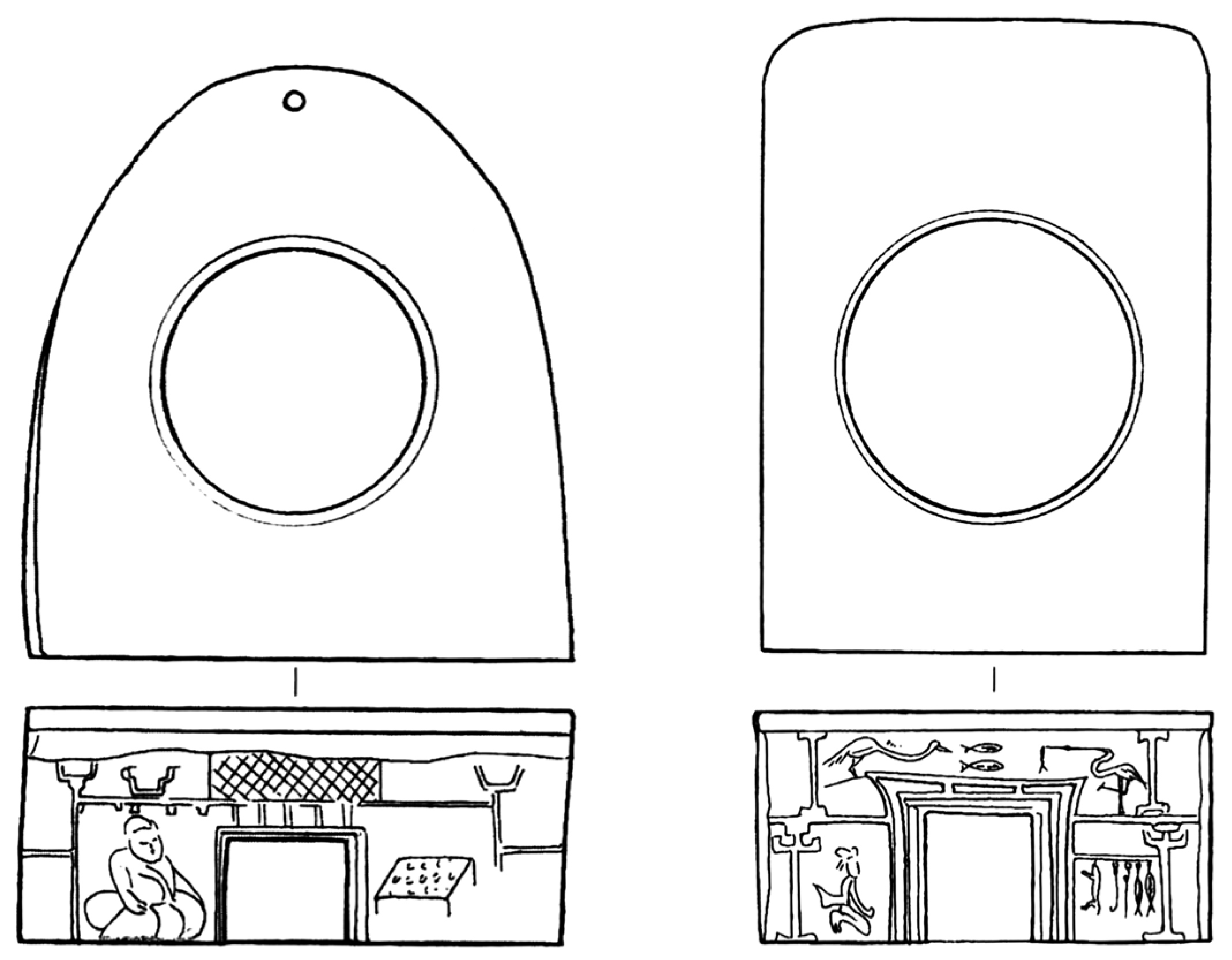

3.1. The Influence of the Kitchen God Belief on the Zaoxing 竈陘6 and Windbreak in the Han Dynasty

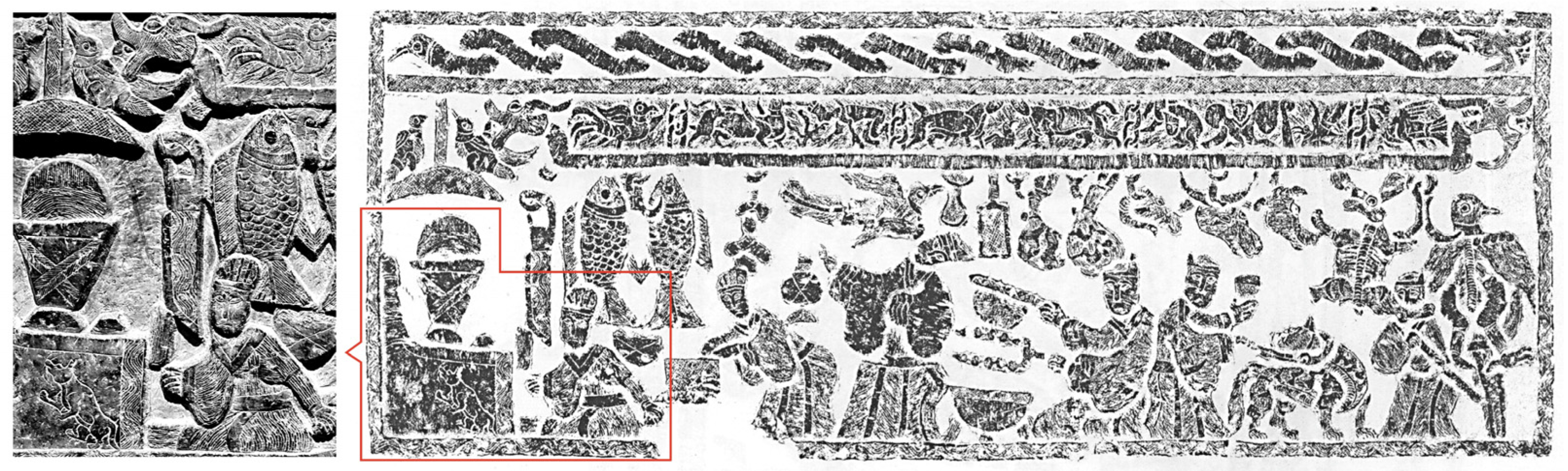

3.2. Stove and Decorative Images Show the Evolution of Stove Sacrifice Rituals in the Han Dynasty

4. The Popularization of Stoves in the Han Dynasty and the Secular Transformation of Kitchen God Beliefs

4.1. The Transformation of the Kitchen God from an Ancestor to a Household God

4.2. The Functional Change from Giving Food to Monitoring the Merits and Demerits of the World

5. The Influence of Stove Design and the Kitchen God Belief in the Han Dynasty on Later Generations

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The Chinese character “竈” (Zao Kitchen stove) was commonly used in ancient China. The modern character “灶” is a simplified version of “竈”. The analysis of the traditional Chinese beliefs about the Kitchen God and kitchen stoves in this paper begins with the character “竈”. |

| 2 | The original meaning refers to the southwest corner of the house. The ancient Chinese believed that the southwest corner was the deepest part of a house, where elders could live and sit, or where an area a place for family worship could be set up. |

| 3 | Amphibian include frogs and toads. The Chinese character “竃 Zao” (stove) and literature from the pre-Qin to Han dynasties mentioned that water in stoves can easily breed amphibian. |

| 4 | The Theory of Animal Metaplasia: Some insects or animals like to reside in stoves. People have observed this phenomenon and believe that the Kitchen God may have evolved from an insect or animal. |

| 5 | Five Sacrifices: Five types of sacrifices were established during the Zhou Dynasty, including the Shi (Zhongliu) 室(中溜), Men 門, Xing 行, Hu 戶, and Zao 竈. Sometimesthe Siming 司命and Tai Li 泰厲 are added creating seven types of sacrificial rituals. These sacrifices originated from family sacrifices and were later integrated and elevated to the national level. |

| 6 | The zaoxing 竈陘 is the part of the stove that protrudes from the edge of the stove, where people in the Han Dynasty placed the tablet of the Kitchen God. The frequency of use of the word “zao xing 竈陘” gradually decreased after the Han Dynasty. |

| 7 | http://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/rwWoVM7-aKfzU-dWKCkAHQ (accessed on 2 March 2025). |

| 8 | https://www.chnmus.net/ch/collection/appraise/details.html?id=512153402845896505 (accessed on 2 March 2025). |

| 9 | Shuowen Jiezi, China’s first dictionary, was a tool compiled by Xu Shen, a literalist of the Eastern Han Dynasty. It is the earliest Chinese language dictionary that systematically analyzes the glyphs of Chinese characters and examines their origins. |

| 10 | There are almost no images of basins and bottles on the pottery stoves of the Han Dynasty discovered by Chinese archaeologists. This may be because the pot on the stove was used as a substitute to hold food. |

| 11 | http://hylae.com/index.php?ac=article&at=read&did=1842 (accessed on 2 March 2025). |

| 12 | https://www.xabwy.com/showtwo.html?id=927&type=190&num=5 (accessed on 2 March 2025). |

| 13 | Fire Virtue: Fire virtue plays an important role in Chinese culture and the Five Elements theory, which is associated with both the mythological god of fire, or Yandi, and the element of fire in the Five Elements theory, where it is believed that a person can prosper by possessing the virtue of fire. |

| 14 | https://www.hermitagemuseum.org/digital-collection/313435?lng=en (accessed on 2 March 2025). |

| 15 | https://www.hermitagemuseum.org/digital-collection/289345?lng=en (accessed on 2 March 2025). |

References

- Anne, Swann Goodrich. 1991. Peking Paper Gods: A Look at Home Worship. Monumenta Serica Monograph Series No. 23; Nettetal: Steyler. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. 1901. Zao Wang Zhen Jing 竈王真經 (The Kitchen God Sutra). Engraved Edition of the 27th Year of Guangxu Reign. Available online: https://taolibrary.com/category/category61/c61102.htm (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- Anonymous. 2011. Kong Zi Jia Yu 孔子家語 (Saying of Confucius). Edited by Xiumei Wang and Wang Guoxuan. Beijing: Zhong Hua Shu Ju 中華書局 (Zhonghua Book Company). [Google Scholar]

- Arthur, Wolf. 1974. Religion and Ritual in Chinese Society. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ban, Gu. 1994. Bai Hu Tong Yi 白虎通義. Beijing: Zhong Hua Shu Ju 中華書局 (Zhonghua Book Company). [Google Scholar]

- Ban, Gu. 2007. Han Shu 漢書 (Book of Han Dynasty). Beijing: Zhong Hua Shu Ju 中華書局 (Zhonghua Book Company). [Google Scholar]

- Bray, Francesca. 1997. Technology and Gender: Fabrics of Power in Late Imperial China. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Yong. 1990. Du Duan 獨斷. Shanghai: Shang Hai Gu Ji Chu Ban She 上海古籍出版社 (Shanghai Classics Publishing House). [Google Scholar]

- Chard, Robert L. 1990a. Master of the Family: History and Development of the Chinese Cult of the Stove. Master’s thesis, University of California at Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Chard, Robert L. 1990b. Folktales on the God of the Stove. Chinese Studies 8: 149–82. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Shouqi. 2012. Wu Jing Yi Yi Shu Zheng 五經異義疏證 (Explanation and Proof of the Differences Among the Five Classics). Edited by Jiandun Cao. Shanghai: Shang Hai Gu Ji Chu Ban She 上海古籍出版社 (Shanghai Classics Publishing House). [Google Scholar]

- Confucius and His Disciples. 2011. Lun Yu 論語 (The Analects of Confucius). Edited by Xiaofen Chen and Ruzong Xu. Beijing: Zhong Hua Shu Ju 中華書局 (Zhonghua Book Company). [Google Scholar]

- David, Johnson, and Songnian Pu. 1992. Domesticated Deities and Auspicious Emblems: The Iconography of Everyday Life in Village China. Berkeley: Chinese Popular Culture Project. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Chengshi. 2002. You Yang Za Zu 酉陽雜俎 (Miscellaneous Morsels from Youyang). Jilin: Ji Lin Ren Min Chu Ban She 吉林人民出版社 (Jilin People’s Publishing House). [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Menghe. 1991. Xian Qin Tao Zao De Chu Bu Yan Jiu 先秦陶竈的初步研究 (Preliminary Study on Pre Qin Pottery Stove). Kao Gu 考古 (Archaeology) 11: 1019–22. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Qingfan. 1985. Zhuang Zi Ji Shi 莊子集釋 (Zhuangzi’s Collection of Explanations). Edited and Translated by Xiaoyu Wang. Beijing: Zhong Hua Shu Ju 中華書局 (Zhonghua Book Company). [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich, Heine. 1985. Concerning the History of Religion and Philosophy in Germany. Translated by Mustard Helen. New York: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Yingguang. 2022. Nan Du Yi Zhen: Zhang Heng Bo Wu Guan Guan Cang Wen Wu Jing Cui 南都遗珍: 张衡博物馆馆藏文物精粹 Southern Capital Heritage: The Essence of Cultural Relics from the Zhangheng Museum Collection. Zhengzhou: Zhongzhou Classics Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Yongfeng, and Luansheng Lin. 2016. Zao Shen Xin Yang De Jia Ting Lun Li Guan Ji Qi Dang Dai Qi Shi 竈神信仰的家庭倫理觀及其當代啓示 (The Family Ethics of Kitchen God Belief and Its Contemporary Revelation). Shi Jie Zong Jiao Yan Jiu 世界宗教研究 (Studies in World Religions) 3: 136–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hubei Jingsha Railway Archaeological Team. 1991. Bao Shan Chu Mu 包山楚墓 (Baoshan Chu Tomb). Beijing: Wen Wu Chu Ban She 文物出版社 (Cultural Relics Publishing House). [Google Scholar]

- Hubei Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics, and Archaeology, Department of Chinese at Peking University. 1995. Wang Shan Chu Jian 望山楚简 (Wangshan Chu Bamboo Slips). Beijing: Zhong Hua Shu Ju 中華書局 (Zhong Hua Book Company). [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Archaeology Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Guangzhou Municipal Cultural Relics Management Committee, Guangzhou Museum. 1981. Guang Zhou Han Mu 廣州漢墓 (Guangzhou Han Tomb). Beijing: Wen Wu Chu Ban She 文物出版社 (Cultural Relics Publishing House). [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Yanhong. 2003. Lue Lun Xian Qin Liang Han Min Jian De Zao Shen Chong Bai 略論先秦兩漢民間的竈神崇拜 (A Brief Discussion on the Worship of Kitchen God in the Folk of the Pre-Qin and Han Dynasties). Guan Zi Xue Kan 管子學刊 (Guan Zi Journal) 3: 81–83. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Fang. 2008. Taiping Yulan 太平御覽 (Imperial Readings of the Taiping Era). Shanghai: Shang Hai Gu Ji Chu Ban She 上海古籍出版社 (Shanghai Classics Publishing House). [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Jingyu, Yancui Zhang, Ruitong Guo, and Heyong Shen. 2021. A Jungian Analysis of the Chinese Kitchen God Image. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Yun. 1999. Lun Qin Han Shi Dai De Tao Zao 论秦汉时代的陶灶 (On Pottery Stove of Qin and Han). Kao Gu Yu Wen Wu 考古与文物 (Archaeology and Cultural Relics) 1: 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Jifu. 1997. Han Zu Shao Shu Min Zu Zao Shen Xin Yang Bi Jiao Yan Jiu 漢族、少數民族竈神信仰比較研究 (A Comparative Study of Kitchen God Belief of Han Chinese and Ethnic Minorities). Min Su Yan Jiu 民俗研究 (Folklore Studies) 1: 67–68. [Google Scholar]

- Linyi Museum. 2002. Lin Yi Han Hua Xiang Shi 臨沂漢畫像石 (Linyi Han Dynasty Stone Carvings). Jinan: Shan Dong Mei Shu Chu Ban She 山東美術出版社 (Shandong Fine Arts Publishing House). [Google Scholar]

- Liu, An. 2012a. Huai Nan Zi 淮南子. Edited by Chen Guangzhong. Beijing: Zhong Hua Shu Ju 中華書局 (Zhonghua Book Company). [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Mi, and Zhijun Wu. 2017. Zhong Guo Zao Ju Xing Tai De Yan Bian Li Cheng Tan Xi 中國竈具形態的演變歷程探析 (Analysis of the Evolution Process of the Chinese Cookstove Form). Jia Ju Yu Shi Nei Zhuang Shi 傢俱與室內裝飾 (Furniture&Interior Design) 7: 23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Ruiming. 2003. Zao Shen Shen Hua Yan Jiu Bu Shuo 竈神神話研究補說 (The Evolution of Kitchen God). Si Chuan Da Xue Xue Bao Zhe Xue She Hui Ke Xue Ban 四川大學學報(哲學社會科學版) Journal of Sichuan University (Social Science Edition) 1: 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Xiang. 2012b. Zhan Guo Ce 戰國策 (The Strategies of the Warring States). Edited by Miao Wenyuan, Miao Wei and Luo Yonglian. Beijing: Zhong Hua Shu Ju 中華書局 (Zhonghua Book Company). [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Xiang. 2013. Guo Yu 國語 (The Discourses of the States). Edited by Tongsheng Chen. Beijing: Zhong Hua Shu Ju 中華書局 (Zhonghua Book Company). [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Yuntao. 1999. Shan Dong Ju Xian Shuang He Cun Han Mu 山東莒縣雙合村漢墓 (Han Dynasty Tombs in Shuanghe Village, Juxian County, Shandong Province). Wen Wu 文物 (Cultural Relics) 12: 25–27+100+02. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Zhen. 2008. Dong Guan Han Ji 東觀漢記. Edited by Shuping Wu. Beijing: Zhong Hua Shu Ju 中華書局 (Zhonghua Book Company). [Google Scholar]

- Lü, Buwei. 2011. Lü Shi Chun Qiu 呂氏春秋 (Lü Shi Spring and Autumn Annals). Edited by Jiu Lu. Beijing: Zhong Hua Shu Ju 中華書局 (Zhonghua Book Company). [Google Scholar]

- Michael, Loewe. 2005. Faith, Myth, and Reason in Han China. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Pu, Songnian. 2021. Zhong Guo Zao Jun Shen Ma 中國竈君神禡 (The Chinese Kitchen God). Beijing: Ren Min Mei Shu Chu Ban She 人民美術出版社 (People‘s Fine Arts Publishing House). [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Jun. 1999. Zao Shen Kao Yuan 竈神考源 (The Origin of the Kitchen God in Research). Zhong Guo Shi Yan Jiu 中國史研究 (Journal of Chinese Historical Studies) 1: 160–62. [Google Scholar]

- Roel, Sterckx. 2011. Food, Sacrifice, and Sagehood in Early China. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ronald, G. Knapp. 1999. China’s Living Houses: Folk Beliefs, Symbols, and Household Ornamentation. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shanghai Museum. 1987. Shang Zhou Qing Tong Qi Ming Wen Xuan 2 商周青銅器銘文選 2 (Selected Inscriptions on Shang and Zhou Bronze Ware Vol. 2). Beijing: Wen Wu Chu Ban She 文物出版社 (Cultural Relics Publishing House). [Google Scholar]

- Sima, Qian. 1959. (145–86 BCE). Shi Ji 史記 (Records of the Grand Historian). Beijing: Zhong Hua Shu Ju 中華書局 (Zhonghua Book Company). [Google Scholar]

- The Hubei Provincial Museum. 1976. Yi Chang Qian Ping Zhan Guo Liang Han Mu 宜昌前坪战国两汉墓 (Excavations of the Warring States and Han Tombs at Qian-ping in Yi-chang, Hubei Province). Kao Gu Xue Bao 考古学报 (Acta Archaeologica Sinica), 115–48. [Google Scholar]

- The Nanyang Museum. 1982. He Nan Nan Yang Shi Qiao Han Hua Xiang Shi Mu 河南南阳石桥汉画像石墓 (Han Dynasty Portrait Stone Tomb in Shiqiao, Nanyang, Henan Province). Kao Gu Yu Wen Wu 考古与文物 (Archaeology and Cultural Relics) 1: 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Qiang, and Yu Bai. 2010. Zhong Guo Zao Ju She Ji Yan Bian Yan Jiu 中國古代竈具設計演變研究 (Evolution of Chinese Ancient Stove Design). Zhuang Shi 裝飾 11: 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Zimu. 2017. Meng Liang Lu 夢樑錄. Quan Song Bi Ji 全宋筆記 (A Notebook of the Whole Song Dynasty (960–1279). Zhengzhou: Da Xiang Chu Ban She 大象出版社 (Elephant Press), vol. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Wuzhi County Cultural Center. 1983. Wu Zhi Chu Tu Da Xing Han Dai Tao Lou 武陟出土的大型漢代陶樓 (Large Han Dynasty pottery tower unearthed in Wuzhi). Zhong Yuan Wen Wu 中原文物 (Cultural Relics of Central China) 1: 22. [Google Scholar]

- Xi’an Institute of Cultural Relics Protection and Archaeology. 2009. Xi An Dong Han Mu西安东汉墓 Tombs of the Eastern Han Dynasty in Xi’an. Beijing: Wen Wu Chu Ban She 文物出版社 (Cultural Relics Publishing House). [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Shen. 1963. Shuo Wen Jie Zi 说文解字. Beijing: Zhong Hua Shu Ju 中華書局 (Zhonghua Book Company). [Google Scholar]

- XuZhou Museum. 1993. Xu Zhou Hou Lou Shan Xi Han Mu Fa Jue Bao Gao 徐州後樓山西漢墓發掘報告 (Excavation Report of Shanxi Han Tomb in Xuzhou Houlou). Wen Wu 文物 (Cultural Relics) 4: 36. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Dongyan. 2001. Bai Ma Zang Zu Xin Yang Xi Su Xian Zhuang Diao Cha Yan Jiu (白馬)藏族信仰習俗現狀調查研究 (Research On the Tibetan Religious Belief and Customs in BaiMa Regions). Xi Bei Min Zu Yan Jiu 西北民族研究 (Northwestern Journal of Ethnology) 3: 66–68. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Fuquan. 1995. Zao Yu Zaoshen 竈與竈神 (Kitchen Stoves and Kitchen God). Beijing: Xue Yuan Chu Ban She 學苑出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Hua. 2004. ’Wu Si’ Ji Dao Yu Chu Han Wen Hua De Ji Cheng “五祀”祭禱與楚漢文化的繼承 (The Five Sacrifices and the Inheritance of Chu Han Culture). Jiang Han Lun Tan 江漢論壇 (Jianghan Tribune) 9: 95–101. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Kun. 1991. Yang Kun Min Zu Xue Yan Jiu Wen Ji 楊堃民族學研究文集 (Yang Koon Ethnographic Research Collection). Beijing: Min Zu Chu Ban She 民族出版社 (The Ethnic Publishing House). [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Xiong. 1990. Tai Xuan Jing 太玄經. Shanghai: Shang Hai Gu Ji Chu Ban She 上海古籍出版社 (Shanghai Classics Publishing House). [Google Scholar]

- Ying, Shao. 1981. Feng Su Tong Yi Jiao Zhu 風俗通義校注. Edited by Liqi Wang. Beijing: Zhong Hua Shu Ju 中華書局 (Zhonghua Book Company). [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Chenglong. 2009. Zhan Guo Chu Bu Shi Qi Dao Jian Zhong De ’Wu Si’ 戰國楚卜筮祈禱簡中的“五祀” ’Wusi’ (five si) in the Slips Recording Prognostication Prayers of Chu Shamans in the Warring States Period. Gu Gong Bo Wu Yuan Yuan Kan 故宮博物院院刊 (Palace Museum Journal) 2: 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Jing, and Chengming Zhang. 2012. Liang Han Mu Zang Zhong Chu Tu Tao Zao De Kao Gu Lei Xing Xue 兩漢墓葬中出土陶竈的考古類型學研究 (A Typological Study of the Pottery Kitchen Stove models Excavated from Han Tombs). Jiang Han Kao Gu 江漢考古 (Jianghan Archaeology) 1: 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, Shichuang, and Xiufang Zhang. 1994. Huo Yu Zao Shen Xing Xiang Shan Bian Lun 火與竈神形象嬗變論 (On the Transmutation of the Image of Fire and Kitchen God). Shi Jie Zong Jiao Yan Jiu 世界宗教研究 (Studies in World Religions) 1: 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Xuan. 2008. Li Ji Zheng Yi 禮記正義 (The Book of Rites and Justice). Shanghai: Shang Hai Gu Ji Chu Ban She 上海古籍出版社 (Shanghai Classics Publishing House). [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Gongdan. 2014. Zhou Li 周禮 (The Ritual of Zhou). Edited by Xu Zhengying and Chang Peiyu. Beijing: Zhong Hua Shu Ju 中華書局 (Zhonghua Book Company). [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, Qiuming. 2012. Zuo Zhuan 左傳. Edited by Dan Guo, Xiaoqing Cheng and Binyuan Li. Beijing: Zhong Hua Shu Ju 中華書局 (Zhonghua Book Company). [Google Scholar]

| Serial No. | Literature | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Records of the Grand Historian: Basic annals of the Filial Martial Emperor 史記·孝武帝本紀 | During the reign of Emperor Wu 汉武帝 (156–87 BCE) of the Han Dynasty, a man named Li Shaojun 李少君 gained considerable influence due to his practice of offering sacrifices to the stove, fasting, and employing techniques to reverse the effects of aging. The emperor held him in high regard (Sima 1959, p. 453). 如武帝之時,有李少君,以祠竈、辟穀、卻老方見上,上尊重之。 |

| 2 | The Huainanzi: Zhushuxun 淮南子·主術訓 | Following the consumption of a meal, an offering would be made to the stove (A. Liu 2012a, p. 492). 已飯而祭竈。 |

| 3 | Book of Han Dynasty: Vol. 45 漢书·卷四十五 | Luan Bu’s mother was honoured for her virtue, but committed a great sin by sitting on the stove and cursing the emperor to the Kitchen God (Ban 2007, p. 474). 躬母聖,坐祠竈祝詛上,大逆不道。 |

| 4 | Book of Han Dynasty: Vol. 77 漢书·卷七十七 | Subsequently, Sun Bao was appointed to the role of registrar. He relocated to the residence allocated to him, offered sacrifices to the Kitchen God, and extended invitations to his neighbors for a meal (Ban 2007, p. 778). 後署寳主簿,寳徙入舍,祭竈請比鄰。 |

| 5 | Saying of Confucius: Zigong’s enquiry as to petty rites 孔子家語·曲禮子貢問 | Burn wood in the stove to sacrifice to the Kitchen God (Anonymous 2011, p. 500). 燔柴於竈以祀焉。 |

| 6 | Du Duan: I 獨斷·卷上 | The ritual sacrifice to the Kitchen God in summer is to sacrifice the sun, as this season is when yang qi is at its strongest and all things are growing. This is the reason for the sacrifice before the Kitchen God. The ceremony of sacrifice to the Kitchen God is conducted to the east of the door of the temple. First, the emperor stands eastwards on the west side behind the door, then a spiritual tablet for the deceased is established on the edges of the stove (Cai 1990, p. 7). 竈夏為太陽,其氣長养,祀之於竈。祀竈之禮,在廟門外之東,先帝於門奥西東,設主於竈陘也。 |

| 7 | Shuo Wen Jie Zi: Part of cuan 説文解字·爨部 | The term “釁”(Xin) is used to denote a blood sacrifice, which serves to symbolize the ritual sacrifice to the Kitchen God (Xu 1963, p. 60). 釁:血祭也。象祭竈也。 |

| 8 | Dong Guan Han Ji: The Biography of Huang Xiang 東觀漢記·黃香傳 | On the day of his appointment to the government post, he did not engage in the customary ritual of offering sacrifices to the Kitchen God to seek blessings (Z. Liu 2008, p. 764). 到官之日,不祭竈求福。 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, X. The Interactive Relationship and Influence Between Kitchen God Beliefs and Stoves in the Han Dynasty (202 BCE–220 AD). Religions 2025, 16, 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16030319

Liu X. The Interactive Relationship and Influence Between Kitchen God Beliefs and Stoves in the Han Dynasty (202 BCE–220 AD). Religions. 2025; 16(3):319. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16030319

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Xiangyu. 2025. "The Interactive Relationship and Influence Between Kitchen God Beliefs and Stoves in the Han Dynasty (202 BCE–220 AD)" Religions 16, no. 3: 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16030319

APA StyleLiu, X. (2025). The Interactive Relationship and Influence Between Kitchen God Beliefs and Stoves in the Han Dynasty (202 BCE–220 AD). Religions, 16(3), 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16030319