1. Introduction

Today, people think the question, are we alone—the only physical intelligent species—in the universe, is a scientific debate. However, during the millennia that preceded the twentieth century the debate, at an academic limit, was owned by theologians and philosophers (

Crowe 2008). That there was an active ongoing debate among theologians that delved into a rich tapestry of beliefs about the existence of intelligent beings on other planets in the universe frequently is lost upon present-day atheists, agnostics, skeptics, and even many deists and theists, including Christians.

The pre-twentieth century debate on extraterrestrial life was not limited to academia. Previous to World War I, more than 140 books on extraterrestrial life written for a broad audience had appeared (

Crowe 2008, p. 159).

The assertions of nearly all present-day non-theistic and agnostic scholars has been that the discovery of life of any kind, let alone intelligent life, would be catastrophic to religious beliefs (

Bertka 2013). Their assertions are based on the belief that the discovery of life on multiple planets would prove the origin of life from a suitable prebiotic soup of chemical compounds must be so straightforward and easy that it is not necessary to invoke God as a causal agent. These non-theists and agnostic skeptics likewise assert that the discovery of ETI would prove that the evolution of intelligent life from primitive microbes must be so straightforward and easy that no God is necessary to explain it.

Many non-theists and agnostic skeptics conclude that all religious people and especially religious leaders and scholars would be threatened by evidence for extraterrestrial intelligent life (ETI). Therefore, they presume that among theistic scholars there never has been a debate about ETI, that necessarily all of them believe and have believed that physical intelligent life exists on only one body in the universe—planet Earth.

Theologians and others have countered that if life’s origin and evolution really were so straightforward and easy, we should see it occurring in real time. That we do not, they argue, implies that these steps are too hard for natural processes to achieve. As further evidence, they point out that if the origin of life really was so straightforward and easy, biochemists would have created life in the lab long ago and several times over (

Rana 2011;

Richert 2018). The fact that even the most knowledgeable, intelligent, skilled, and technologically equipped biochemists are unable to assemble any more than 50 amino acids, let alone a functional protein, and are incapable of manufacturing an RNA or DNA molecule from scratch implies that someone much more knowledgeable, intelligent, and powerful than our best biochemists must have created life.

Many theologians conclude, therefore, that God and only God must have created life. If God has done it on Earth, there is no reason, they say, why he could not have done it on another planet or moon. Some theologians argue that God’s character implies he has created life in diverse forms on a great many planets and/or moons. Others cite theological reasons why God would limit his creating life on just one or a few planets.

Theologians have posed another counter toward atheists and agnostic skeptics. They point out that a scientific determination that physical life in the universe only exists on Earth would be problematic for non-theistic and agnostic beliefs. Such a determination either would suggest or show that only Earth possesses the exceptionally fine-tuned physical and chemical features that life requires and/or that the origin of life from non-life is far from an easy naturalistic step. The bottom line is that materialists need ET and ETI to exist, whereas theists can have it either way.

Of interest to theologians and scientists of all philosophical persuasions is how revelations from science about life or the absence of life beyond Earth could illuminate humanity’s purpose and place with the cosmos. At a minimum, such revelations could help bridge gaps between scientific exploration and theological inquiry, fostering a dialog that enriches both fields and enhances our understanding of existence itself.

2. The Theological Debate

From a Christian creationist perspective, as contrasted with a variety of theistic evolutionary perspectives, we humans are here on Earth, according to the Bible, because God supernaturally intervened at multiple times and in multiple different ways with perfect timing at each incident to ensure that within a brief time window we could exist and rapidly develop a global high-technology civilization. God, of course, could perform the same set of miracles on one or more other planets in the universe. At no point does the Bible state or imply that there is another race elsewhere in the universe or that there is not. Therefore, from a biblical Christian perspective the probability of a search for extraterrestrial intelligent life (SETI) success may be greater than zero. However, Christian theologians, based on different biblical texts, have debated for two millennia whether God has created life, including intelligent beings, on multiple bodies in the universe or only on Earth. Notable examples include Origen [185–254 AD] (

Origen 2013, pp. 103–15), Augustine [354–430 AD] (

Augustine of Hippo 1909a,

1909b,

1909c), Bonaventure [1221–1274 AD] (

McColley and Miller 1937), Thomas Aquinas [1225–1274 AD] (

Aquinas 2006), Francis of Meyronnes [1280–1328 AD] (

McColley and Miller 1937), William Vorilong [1390–1463 AD] (

McColley and Miller 1937), Nicholas of Cusa [1401–1464 AD] (

Wilpert 1967), Tomasso Campanella [1568–1634 AD] (

Campanella 1994), Philip Melanchthon [1497–1560 AD] (

Melanchthon 1563), Ralph Waldo Emerson [1803–1882 AD] (

Emerson 1989), and Ellen G. White [1827–1915 AD] (

White 1948), This debate also included whether extraterrestrial intelligent beings, if they exist, could be strictly physical creatures lacking any awareness of God, sin, or an afterlife.

Christian scholars first point out that the Bible clearly and repeatedly proclaims God is the only one who can create life and who has created life. They point to Bible passages like Genesis 1, Job 39–41, Psalm 104, and Isaiah 44. Therefore, they conclude the discovery of life on another planet beyond Earth, whatever form that life might possess, would simply demonstrate that God has created life on more than one of the observable universe’s approximately trillion trillion planets.

In fact, the Bible explicitly declares God has indeed created ET, specifically ETI. These extraterrestrial intelligent beings are angels. They are described in 38 of the Bible’s 66 books. Angels, according to the Bible, differ from human beings in that they are not constrained by the universe’s laws of physics or the universe’s space-time dimensions. They predominantly live in a realm distinct from the physical universe. However, God has granted them the power, according to the Bible, to occasionally leave their realm and enter into our physical realm for brief episodes. They can enter either in physical or nonphysical form.

The existence of ETI—whether physical beings constrained by the physics and dimensions of the universe or beings who are not constrained by the physics and dimensions of the universe—poses no threat to the Christian faith. Christianity, at a minimum, teaches the existence of angelic ETI. It also is open to the possibility of God creating ET and/or ETI who, like us, are constrained by the universe’s dimensions and laws of physics.

From a Christian perspective we humans are not alone. God exists. Angels exist. What is open for debate is whether or not God has created one or more species of life on other planets who are intelligently and technologically capable, yet confined by the cosmos’s physics. This is the debate that Christian scholars have engaged one another since Christianity’s birth two millennia ago.

Several Christian thinkers have pointed out there are no Bible passages that would constrain God from creating life on other planets. In fact, the creation psalm, Psalm 104, declares that God has created life on Earth with enormous abundance and diversity. It states there is nowhere one can go on Earth’s surface, in Earth’s ocean depths, or on Earth’s mountain heights and not find life-forms God has created. Psalm 104, the other seven creation psalms (Psalm 8, 29, 33, 65, 139, 145, 148), Job 12:7–10, 38:36–41:34, and Isaiah 42:5, 44:23-24, 45:18 proclaim how abundantly and joyfully God has created all manner of life.

Several Christian scholars have cited God’s manifest, pervasive exuberance for creating life as strong evidence that physical ETI like us must be prevalent throughout the universe. Such belief explains why this kind of ETI shows up so frequently in science fiction literature written by famous Christian authors such as C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, and Madeleine L. Engle.

Other Christian scholars have countered that if, indeed, God has created physical, human-like ETI on multiple bodies throughout the universe, it seems odd that the Bible would be totally silent about such beings. This silence is all the more bizarre, such scholars declare, given how much the Bible says about angels (

Origen 2013, pp. 161–71;

Crowe 2008).

A response to this counter is that the Bible is demonstrably silent on several topics and issues that have no bearing on how humans can be saved from their sin and enter into an eternal, loving relationship with their Creator. Consequently, if extraterrestrial beings have not sinned and, therefore, are not in need of a divine Savior, these Christians conclude there would be no need for the Bible to make any mention of them.

Christian scholars who have maintained we humans are alone—the only intelligent physical species in the cosmos—point out that the New Testament gospels reveal a God who is purposeful, selective, and conservative in the miracles he performs (

Aquinas 2006;

O’Meara 1999). The gospel accounts tell of several instances where the crowds, Pharisees, and even the disciples (Matthew 12:38–42, Luke 9:51–56, John 2:14–20, 6:30) asked Jesus to perform a miracle. At Jesus’ trial, King Herod hoped to see Jesus perform a miracle (Luke 23:6–11). In every such occurrence, Jesus refused to perform a miracle. These events serve to illustrate that God apparently limits the miracles he performs to those that are necessary to fulfill his intended purposes.

This economy of divine miracles principle may apply to ETI in the following way: God needs technologically capable, intelligent physical beings endowed with spirit natures on only one planet in the universe to achieve his ultimate purpose of populating the new creation with intelligent free-will beings whom he has redeemed from sin and evil. To get this one planet, given the laws of physics God has chosen for a variety of reasons to govern the universe (

Ross 2008), the universe must be exactly as massive and large as it is. These intelligent creatures whom God has eternally redeemed and delivered from sin will spend eternity expressing love to and receiving love from God and one another. This is the biblically stated purpose for God creating human beings.

The one possible biblical constraint on ETI is in Hebrews 10:12, 14: “This priest [Jesus Christ] had offered for all time one sacrifice for sins … by one sacrifice he has made perfect forever those who are made holy.” This passage appears to rule out a Creator-Savior visiting multiple planets to sacrifice himself over and over for the sins of beings like us living on multiple planets. However, it does not rule out microbes, plants, or dolphins on other planets. It does not rule out beings like us who have never thought, expressed, or done anything evil.

Some theologians, for example, Origen, Guillaumme de Vaurouillon [1392–1463], and Joseph Pohle [1852–1922] have argued that Hebrew 10 does not even rule out the possibility Jesus’s one sacrifice on Earth somehow atoned for the sins of beings like us on more than one planet (

McColley 1936). They point out just as humans today can read about Christ’s incarnation, sacrifice, and resurrection and verify the historical evidence for these events, physical-spiritual beings on another planet conceivably could learn about and verify the same events.

From a biblical perspective, Christians have a range of options on what they can hypothesize and believe about ET, ETI, and extraterrestrial civilizations. They can believe one or more of these extraterrestrial options exist on one or more planets or that physical life, constrained by the physics of the universe. exists on only one cosmic body.

From a naturalistic perspective, though, nontheists have limited options. They are compelled to believe there are no naturalistic barriers to (1) the existence of cosmic bodies with features similar to the Sun’s, Moon’s, and Earth’s, and many of the features of the other seven solar system planets at numerous Milky Way Galaxy sites and in many sites in all other galaxies in the universe, (2) the origin of life, and (3) a naturalistic evolution of the equivalent of humans from a simple bacterium. The conclusion that physical life in the universe only exists on Earth would be problematic to non-theistic and agnostic beliefs. For nontheists the universe ought to be filled with habitable planets and many of these habitable planets should host life, both unintelligent and intelligent. However, multiple naturalistic barriers appear to exist for all three (see

Section 6,

Section 7,

Section 8,

Section 10 and

Section 11).

For several millennia, the debate over are we alone in the universe was a strictly theological/philosophical debate. In the late twentieth century, scientists began to weigh in on the debate. Now, at the close of the first quarter of the twenty-first century, scientific exploration of the universe has reached a point where several of the debate issues are approaching resolution. Science now is determining which theological/philosophical positions on the “are we alone” question are valid and which are not.

3. Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligent Life (SETI)

SETI missions have been nearly continuously conducted since 1960 when a young astronomer, Frank Drake initiated Project Ozma. Drake used a 26 m (85-foot) diameter radio telescope to search for intelligent signals near 1420 megahertz from the star systems Tau Ceti and Epsilon Eridani. He detected no intelligent signals (

Drake 1961).

Drake advocated for expanding the SETI window to cover the entirety of the “water hole.” In radio astronomy, the water hole is the range of frequencies between the neutral hydrogen (H) emission line at 1420 megahertz and the hydroxyl (OH) radical line at 1612 megahertz. Since water is essential for all conceivable forms of physical life and the frequency range 1420–1612 megahertz is relatively unimpeded in interstellar space, Drake concluded that nearly all interstellar communicating intelligent civilizations would choose to broadcast their presence to other civilizations in the water hole.

The Ohio State University Radio Observatory permitted piecemeal SETI observing runs on its Big Ear radio telescope, which had four times the signal collecting area of Project Ozma’s radio telescope, during its all-sky survey of extraterrestrial radio sources conducted from 1965–1971. From 1973–1995, the Big Ear was dedicated full-time to a continuous SETI survey.

From 1983–1985, Project Sentinel simultaneously searched for intelligent extraterrestrial signals in 131,000 narrow radio band receiving channels on the 26 m (85-foot) diameter radio telescope at Harvard University’s Oak Ridge Observatory. In 1985, Project Sentinel was replaced by Project META (Megachannel Extra-Terrestrial Assay) which had an 8.4 million channel spectrum analyzer and received substantial funding from movie director Steven Spielberg. In 1995, Project BETA (Billion-channel Extraterrestrial Assay) replaced Project META. Project BETA was equipped with two adjacent receiving beams so that candidate signals could be rapidly re-observed. On 23 March 1999, a violent windstorm destroyed the Oak Ridge Observatory radio telescope, terminating Project BETA.

From 1992–1993, NASA conducted the Microwave Observing Program (MOP), a SETI project with a 15 million channel spectrum analyzer used alternately on the three 76 m (250-foot) diameter antennae of NASA’s Deep Space Network, the 305 m (1000-foot) Arecibo radio telescope, and the 43 m (140-foot) Green Bank, West Virginia radio telescope. When the U.S. Congress canceled MOP’s funding, the nonprofit SETI Institute raised private funding to resurrect MOP under the name Project Phoenix. Project Phoenix ran from 1995 to 2015 where the 64 m (210-foot) Parkes radio telescope in Australia replaced the three NASA Deep Space Network antennae. Over the 20-year period Project Phoenix searched for intelligent signals from about a thousand nearby solar-analog stars.

To a lesser degree, astronomers carried out radio SETI searches using the Low Frequency Array (LOFAR) spread across seven European nations, the Murchison Widefield Array (MWA) in Australia, and the 76 m (250-foot) Lovell telescope in the United Kingdom. SERENDIP (Search of Extraterrestrial Radio Emissions from Nearby Developed Intelligent Populations) is a piggy-back program where data from astrophysical observing programs on large radio telescopes around the world is analyzed in the hope of discovering serendipitous intelligent signals. Several optical SETI programs now are progressing. These programs are searching for laser signals targeting the solar system.

The Allen Telescope Array, named after benefactor billionaire Paul Allen, consists of an array of 6.1 m (20-foot) radio telescopes that simultaneously search for intelligent signals while astronomers conduct their observations of radio sources. However, so far, only 42 of the planned 350 radio telescopes have been built and are operational.

The most ambitious SETI project is being conducted on China’s 500 m (1640-foot) Aperture Spherical Telescope (FAST). FAST is the world’s largest single-dish radio telescope with a diameter five times larger than the second place Effelsberg telescope in Germany. FAST is the first large radio telescope built with SETI as the primary goal. Astronomers have conducted SETI observations using FAST since 2019.

4. SETI Results

Russian astronomer Gennady Sholomitskii claimed his observations during the early 1960s of the radio source CTA 102 showed a flux variation of 25–40 percent with a periodicity of 100 days (

Sholomitskii 1965;

Sholomitskii et al. 1965). He interpreted the periodicity as a beacon signal from an extraterrestrial intelligent civilization. However, observations of CTA 102 made during the same time period by two different teams of astronomers found no evidence for Sholomitskii’s claimed variations (

Caswell and Wills 1965;

Maltby and Moffet 1965), nor did observations in 1965 by a third team (

Bologna et al. 1966).

In 1967, pulsing signals from the first discovered pulsar were nicknamed by discoverers, Jocelyn Bell and Anthony Hewish, as LGM-1 for “little green men.” However, speculation that the observed pulses were SETI signals soon were squashed by the discovery of several more pulsars and theoretical physicists Thomas Gold and Franco Pacini explaining that the observed pulses are well explained by rapidly rotating neutron stars (

Gold 1968;

Pacini 1968).

The Big Ear detected a strong narrowband signal, lasting 72 s, on 15 August 1977, that astronomer Jerry Ehman labeled Wow! However, despite multiple attempts by Ehman and other astronomers, the Wow signal has not been detected since. Astronomers concluded the signal either was natural or from a human-generated source.

Project META found eleven “extrastatistical” signals (signals that appear to be more than just background noise) that had the expected features of signals from extraterrestrial transmitters, except they did not repeat. Follow up analysis led astronomers to conclude the META candidates do not indicate “transmissions from intrinsically steady sources” (

Lazio et al. 2002).

SETI observations by FAST detected one unusual signal that piqued the interests of the participating astronomers (

Luan et al. 2025). However, the astronomers, based on the signal’s polarization, frequency, and beam coverage, eliminated the possibility of the signal’s extraterrestrial origin.

So far, not a single extrastatistical signal detected in SETI programs has been observed to repeat. Given the variety of ways single extrastatistical signals can be generated (interference from Earth-based technology, interference from satellites and spacecraft, natural flares/pulses from radio sources, phenomena in Earth’s ionosphere and magnetosphere, scintillation of radio sources), astronomers have concluded that all SETI programs conducted so far have produced null results. That is, SETI results are consistent with Earth being the only cosmic body that hosts intelligent physical life capable of interstellar communication.

5. Interplanetary Panspermia

Astrobiology, the study of life beyond Earth, presently is a data free scientific discipline. In spite of much funding and decades of dedicated research endeavors, astrobiologists have yet to find any undisputed evidence of life beyond Earth. However, it is likely that it is only a matter of time before they do.

Specifically, in the relatively near future astrobiologists will discover the remains of life on another solar system body besides Earth. The reason why is that meteoritic bombardment of Earth has exported Earth’s microbes throughout the solar system. For example, astronomers calculated that meteoritic bombardment has delivered an average of 20,000 kg of Earth soil to every 100 square kilometers of the Moon’s surface (

Armstrong et al. 2002;

Armstrong 2010). For Mars, the calculated delivery is 200 kg per 100 square kilometers. For the upper atmosphere of Venus, it is approximately 1000 kg per 100 square kilometers. For all other solar system bodies, besides the Sun, the delivery rate is less than a kilogram per 100 square kilometers.

One ton of Earth soil contains about 100 quadrillion microbes. Given the 3.8-billion-year history of abundant microbial life on Earth, a lot of Earth’s life has been exported throughout the solar system. Given that Earth was bombarded much more heavily during the first billion years of life history than it is now, most of the life exported from Earth will be the first microbes that existed on Earth.

In the example of the Moon, research affirms that these first microbes would have arrived via low-velocity, oblique-angle trajectories (

Crawford 2008). Therefore, future lunar explorer missions have the opportunity of finding nearly pristine fossils of Earth’s first life. While Earth’s geological activity has destroyed the fossils of Earth’s first life, the Moon’s geological dormancy has preserved them. Lunar missions in the near future realistically could discover the fossils of Earth’s first life and deliver them to origin-of-life research labs on Earth.

These fossils could settle several long-standing debates on what or who is responsible for the origin of Earth’s first life (see

Section 10). While interplanetary panspermia is a possibility, for many reasons interstellar panspermia likely is not (

Ross 2023a). See also

Section 11.

6. ETI Planetary Habitability Requirements

Three separate research studies conducted by astrobiology research teams have estimated the number of potentially habitable planets in the Milky Way Galaxy. One team claimed that 100 billion habitable, Earth-like planets exist in the Milky Way Galaxy (

Abe et al. 2013;

Anthony 2013). A second team said 45.5 billion such planets exist (

Guo et al. 2009). A third study put the number at 40 billion (

Petigura et al. 2013;

Overbye 2013). These numbers have been cited in numerous web articles, videos, and podcasts.

These large numbers presume planetary systems throughout our galaxy are just as abundant as they are in our solar neighborhood. Also, all three studies consider only the liquid water habitable zone and only the broadest definition of the liquid water habitable zone. Rather than defining the liquid water habitable zone as that in which liquid water exists on the planet’s surface continuously for at least two billion years (the minimum requirement for microbes to chemically transform the planet’s atmosphere, crust, and soil so that ETI can exist (

Schwartzman and Volk 1989)), it is defined as possessing liquid water on at least a tiny fraction of its surface for at least a tiny fraction of its existence.

To date, astronomers have discovered 16 planetary habitable zones and 5 galactic habitable zones. As the following lists show, for a planet to be habitable it must reside in all 21 of the known habitable zones plus all of the yet to be discovered habitable zones. The known planetary habitable zones are as follows:

6.1. Liquid Water Habitable Zone

All astrobiologists agree liquid water is essential for the existence of any conceivable kind of physical life. The liquid water planetary habitable zone is the distance range from the planet’s host star where liquid water could exist on the planet’s surface. For liquid water to remain on the planet’s surface requires just-right levels of atmospheric pressure, quantities of greenhouse gases in its atmosphere, and albedo (surface reflectivity).

The assertions that 40–100 billion habitable planets exist in our galaxy is based on efforts to make the liquid water habitable zone as broad as conceivably possible. For example, making the planet’s surface highly reflective, its quantity of atmospheric greenhouse gases very low, its atmospheric humidity no greater than 1 percent, its rotation axis tilt zero with no water transport from high latitudes to low latitudes so that tiny amounts of liquid water could persist near the planet’s poles would permit a planet orbiting a Sun-like star to possess a small quantity of surface liquid water even if it orbited at 0.5 astronomical units (0.5 AU) (

Abe et al. 2011;

Leconte et al. 2013;

Zsom et al. 2013). (An astronomical unit, AU equals the distance Earth orbits the Sun). On the other hand, making the planet as dark as the Moon (7 percent surface reflectivity), its quantity of greenhouse gases very high, its atmospheric humidity no lower than 95 percent, and filling it with geothermal hotspots would permit a planet orbiting a Sun-like star to possess some surface liquid water even if it orbited at 1.67 AU (

Abbot et al. 2012;

Ueta and Sasaki 2013).

A liquid water habitable zone as broad as 0.50–1.67 AU for a planet orbiting a Sun-like star would include planets that possess a tiny amount of surface liquid water on a miniscule fraction of planet’s surface for a fleeting moment of the planet’s history. For a planet to possess an adequate quantity of surface liquid water for a long enough time that complex life could exist requires a much narrower liquid water habitable zone. It requires a zone narrow enough that frozen water, liquid water, and water vapor can stably exist simultaneously on the planet’s surface over long time periods. It also requires the zone to be narrow enough that water efficiently transitions from one of its states to the other two. These prerequisites limit the liquid water habitable zone for planets orbiting Sun-like stars to 0.99–1.70 AU (

Kopparapu et al. 2013). The 1.70 AU limit presumes life can tolerate atmospheric carbon dioxide levels of several bars. However, the upper limit for aerobic animal ecosystems is 0.00095 bars (see

Section 6.13), which limits the liquid water habitable zone to 0.99–1.05 AU.

For planets orbiting fainter stars than the Sun, the liquid water habitable zone is closer to the star and for planets orbiting stars brighter than the Sun the liquid water habitable zone is farther from the star. The liquid water habitable zone in these cases, however, is more restrictive than it is for Sun-like stars. Stars fainter than the Sun emit many deadly flares and lack luminosity stability. Stars brighter than the Sun burn through their nuclear fuel more rapidly and become hotter at a more rapid rate.

6.2. Ultraviolet Habitable Zone

Neither the origin of life nor the survival of life is possible unless ultraviolet (uv) radiation reaches a planet’s surface. The reason why is that the synthesis of many life-essential biochemical compounds requires a minimum level of incident uv radiation (

Buccino et al. 2006). Too much incident uv radiation, however, will prevent the origin of life and damage or destroy land-based lifeforms. Both the quantity and the wavelength of incident uv radiation must fall within certain narrow ranges for life to originate or survive, and even narrower ranges, for life to flourish.

For hydrogen-burning host stars with effective temperatures below 4600 Kelvin (Celsius degrees above absolute zero), the outer edge of the uv habitable zone falls closer to the star than the inner edge of the liquid water habitable zone (

Guo et al. 2010). For hydrogen-burning host stars with effective temperatures greater than 7100 Kelvin, the inner edge of the uv habitable zone sits farther from the host star than the outer edge of the liquid water habitable zone (

Guo et al. 2010). (For comparison, the Sun’s effective temperature is 5778 Kelvin). For stars that have completed their hydrogen-burning phase, the uv habitable zone is ten times more distant from the host star than the liquid water habitable zone (

Guo et al. 2010).

The uv habitable zone width also is dependent on the host star’s metallicity, Z (fraction of the star’s mass comprising elements heavier than helium) (

Oishi and Kamaya 2016). It is widest when Z = 0.020. Only very near this metallicity can life persist on a planet for as long as 4 billion years. For the Sun, Z = 0.0196 ± 0.0014 (

von Steiger and Zurbuchen 2016). For Z < 0.020, the chance for the existence of persistent life dramatically declines with decreasing Z. About 80 percent of all stars have a metallicity <0.020. For Z > 0.020, the exposure of the host star’s planets’ surfaces to intense, deadly uv radiation increases with Z (

Shapiro et al. 2023).

The astronomers who established that the width of the uv habitable zone depends upon the host’s star’s metallicity also showed the host star’s mass is an important factor (

Oishi and Kamaya 2016). They demonstrated that for all metallicity values of host stars, a region of overlap of the liquid water and uv habitable zones exists only for stars as massive as or more massive than the Sun. This new lower stellar mass limit—for the liquid water and uv habitable zones to overlap for a significant time period—leaves only about 1.5 percent of the Milky Way Galaxy’s stars as candidates for habitability. Also including the metallicity requirements leaves less than 1 percent of stars as candidates. This percentage presumes that the host star’s candidate habitable planet(s) possess intact stable stratospheric ozone shield(s).

These candidate limits for possible habitability are for microbes only. For plants and animals to possibly exist on a planet the uv habitable zone is much narrower and there is even less possibility of overlap with the liquid water habitable zone. The constraints are more confining yet for advanced life and especially so for advanced life maintaining a high-technology civilization. (Advanced life has more severe uv radiation constraints. High-technology civilization requires near global occupation of the planet).

The fact that the liquid water and uv habitable zones must overlap for both the origin and survival of life (

Buccino et al. 2006) eliminates nearly all planetary systems as possible candidates for hosting any kind of physical life. This requirement rules out all planetary systems hosted by M-dwarf and K-dwarf stars (stars less than 0.9 times the Sun’s mass), as well as all O-, B-, and A-type stars (stars more massive than 1.6 times the Sun’s mass). All that remain are F-dwarf stars (stars ranging in mass from 1.1–1.6 times the Sun’s mass) much younger than the Sun, G-dwarf stars (stars ranging in mass from 0.9–1.1 times the Sun’s mass) no older and no less massive than the Sun. (Dwarf or main-sequence stars are stars where nearly all their energy comes from the fusion of hydrogen into helium).

In the Milky Way Galaxy, 75 percent of stars residing at a distance from the galactic center where life can possibly exist are older than the Sun (

Lineweaver et al. 2004). Therefore, based on the liquid water and uv habitable zones alone, less than 1 percent of Milky Way Galaxy stars are possible hosts for planets or moons on which life could survive for more than a brief time.

6.3. Photosynthetic Habitable Zone

This zone is an extension of the uv habitable zone. Nearly all multicellular life on Earth is photosynthetic or critically depends on photosynthetic life. Non-photosynthetic lifeforms and lifeforms not dependent on photosynthetic life have low metabolic rates that range from twenty times to many millions of times less than that of photosynthetic life and lifeforms dependent on photosynthetic life (

Suarez 1992;

D’Hondt et al. 2002;

Canfield et al. 2006;

Colwell and D’Hondt 2013). Without photosynthetic life no active, complex, or large-bodied lifeforms would be possible.

Photosynthetic life requires a narrower uv habitable zone than non-photosynthetic life. Advanced photosynthetic lifeforms, such as land plants, trees, and flowering plants require yet a narrower uv habitable zone. Even a star like the Sun, which possesses the widest possible photosynthetic habitable zone, cannot sustain advanced photosynthetic lifeforms for longer than a half billion years (see

Section 8).

Previous to 3 billion years ago, incident uv radiation levels from the Sun on Earth’s surface were at least a thousand times higher than present levels (

Cnossen et al. 2007). These levels explain why only microbes existed on Earth previous to 3 billion years ago. Likewise, not until a half billion years ago was incident uv radiation from the Sun at a low enough level to permit the existence of land plants and trees and, later, advanced flowering plants.

6.4. Tidal Habitable Zone

A star’s gravity exerts a stronger pull on the near sides of its surrounding planets than on the far sides. Tidal force describes the difference between the near-side tug and the far-side tug. The tidal force a star exerts on a planet is inversely proportional to the third power of the distance between them. Thus, shrinking the distance by one half increases the tidal force by eight times.

Where a planet orbits its star too closely, it become rigidly tidally locked, with one hemisphere permanently facing its star. A familiar example is the Moon where one hemisphere always faces Earth. For planets orbiting several times more closely to the host stars, the star’s tidal forces can compel a planet’s rotation period to be within a factor of three or less of its orbital period. This is the case for Mercury, with a rotation period of 59 Earth days and revolution period of 88 Earth days, and Venus, with a retrograde rotation period of 243 Earth days and an orbital period of 225 Earth days.

For both rigid and non-rigid tidal locking, one hemisphere of the planet would receive an unrelenting flow of stellar radiation for many Earth days while the opposite hemisphere would receive none. The difference between maximum daytime temperatures and minimum nighttime temperatures would be far too extreme for any kind of life to exist.

The only apparent hope for life on a rigidly tidally locked planet would be in the planet’s twilight zone—the narrow longitudinal sliver between permanent light and permanent darkness. However, if such a planet resided in the liquid water habitable zone and possessed an atmosphere, atmospheric transport would move all the planet’s surface water from the day side to the night side where it would be permanently trapped as ice (

Menou 2013). For life to exist on either a rigid or non-rigid tidally locked planet, it would need to be unicellular, with an extremely low metabolic rate, located much below the planet’s surface.

For enduring complex life to be possible on a planet, it must experience a specified low level of tidal interaction either with its star, one or more of its moons, or both. On Earth, for example, the complex interaction of solar and lunar tides sustains a huge biomass and biodiversity on its seashores and continental shelves. These tides also are optimal for recycling nutrients and wastes. They provide a rror role in maximizing rich, diverse, and abundant ecosystems.

If a planet orbits its star too closely, tidal forces relatively quickly will drive the planet’s rotation axis tilt to less than 5° (

Heller et al. 2011). Seasons on the planet either will be non-existent or minimal. This lack of seasons would radically shrink the planet’s habitable surface area and potential biomass and biodiversity.

Tidal locking takes time to develop. A planet’s initial rotation rate gradually slows to equal its rate of revolution. By far the most important factor on tidal locking time is the planet’s distance from its host star. Much less significant factors are the planet’s radius, orbital eccentricity, mass, and initial rotation rate. The rate at which a planet becomes tidally locked to its star is inversely proportional to the sixth power of its distance from the star. Therefore, even the slightest change in a planet’s distance from its star, as little as 1 percent, can place it outside the tidal habitable zone. Tidal forces exerted on Earth, for example, have slowed its rotation from 3–4 h-per-day at the time of the Moon-forming event 4.47 billion years ago to about 21 h per day 488 million years ago, as evidenced by coral reef banding (

Wells 1963;

Zhang 2010), to the current 24 h-day rate that optimally meets the needs of human civilization. (A 25 h rotation rate would generate diurnal temperature differences beyond what outdoor humans and their animals can tolerate (

Karzani et al. 2022). A 23 h rotation rate would generate more laminar cloud and weather patterns resulting in less even precipitation over Earth’s surface (

Yang et al. 2014)).

For a planet to be both in the liquid water and tidal habitable zones so that complex life can exist for more than a brief time, its host star must possess a highly fine-tuned mass. Another factor is that the lesser a star’s mass the closer a habitable planet must orbit the star and the greater will be the erosion of the planet’s rotation axis tilt. To avoid the eradication of seasons on the planet, the host star’s mass must be greater than 0.9 times the Sun’s mass for abundant microbial life to be possible (

Heller et al. 2011) and likely greater than 0.98 times the Sun’s mass for abundant advanced life to be possible. The latter figure is a consequence of the star’s tidal forces slowing down the planet’s rotation rate to a degree intolerable for advanced life by the time advanced life can appear on the planet.

The luminosity of stars rises with the fourth power of their masses. Thus, stars even slightly more massive than the Sun will burn through nuclear fuel much more rapidly and will exhibit more radical luminosity variations. They also emit more ultraviolet radiation deadly for life.

6.5. Ozone Habitable Zone

This zone is the range of distances from a host star where a planet potentially can form an ozone shield, a layer with a high concentration of ozone molecules (O3), in its upper atmosphere. Such an ozone shield is necessary to block out the deadly-for-life short wavelength ultraviolet (uv) radiation from the host star. This ozone shield requires an oxygen-rich atmosphere plus a just-right amount of incident ultraviolet radiation (uv) at a just-right range of wavelengths from the planet’s host star. That just-right amount of incident uv radiation at just-right wavelengths impinging upon a just-right amount of oxygen in the planet’s atmosphere will establish a stable ozone-oxygen cycle.

In such a cycle, ozone is created by uv light striking ordinary oxygen molecules (O2) to form individual oxygen atoms where these atoms react with unbroken O2 molecules to form O3. The resulting O3 molecules are unstable. Uv light will strike some of the O3 molecules splitting them into O2 and O. A stable ozone shield forms when there is a balance between the production of O3 and the destruction of O3.

Extremely short uv radiation (10–100 nanometers) exterminates all lifeforms. However, if a sufficient amount of nitrogen exists in a planet’s atmosphere, it screens out this radiation. Even a thin ozone shield, such as what Earth possessed beginning 2.4 billion years ago when the atmospheric oxygen level reached 0.1 percent (

Lyons et al. 2014), screens out all uv-C radiation (100–280 nanometers), permitting most microbial lifeforms to exist both in the oceans and on land (

Ruiz et al. 2023). A thick ozone shield, such as what Earth possessed beginning 538 million years ago when the atmospheric oxygen level reached 10 percent (

Lyons et al. 2014), screens out all but long wavelength uv-B radiation (280–315 nanometers), permitting the existence of plants and animals (

Lyons et al. 2021). An even thicker ozone shield such as what formed in Earth’s atmosphere 330 million years ago, when the atmospheric oxygen level reached 20 percent (

Krause et al. 2018), screens out all uv-B radiation shorter than 305 nanometers. Uv-B radiation 305–315 nanometers is crucial for the skin’s production of vitamin D in mammals. Thus, for mammals to exist, the host planet must possess an exquisitely fine-tuned ozone shield.

Atmospheric ozone levels also impact a planet’s surface temperature. When ozone is absent in a planet’s upper atmosphere, that absence makes the upper atmosphere colder and, hence, drier, which weakens the greenhouse effect. For Earth, the ozone shield warms the surface temperature by 3.5 °C (6.3 °F) (

Deitrick and Goldblatt 2023). Therefore, the ozone habitable zone alters the liquid water, ultraviolet, and photosynthetic habitable zones by substantial degrees.

6.6. Astrosphere Habitable Zone

A star’s “wind” (photon and particle radiation emission) pushes against cosmic radiation, radiation emanating from its galaxy’s core and from nearby supernova explosions. This stellar wind creates a “cocoon” of charged particles around the star. For a planet inside the cocoon, the astrosphere will protect the planet’s atmosphere and surface from high-energy cosmic radiation that would be deadly to life.

A powerful stellar wind will produce a large plasma cocoon (astrosphere). However, stellar radiation within the cocoon could kill or seriously limit prospects for life on planets within the cocoon. On the other hand, a weak stellar wind will produce a small plasma cocoon that inadequately shields a star’s potentially habitable planet from deadly cosmic radiation.

An astrosphere’s protection depends on the star’s mass and age and the density of the interstellar medium in which the star resides. Since stars orbit around their galaxy’s center, the interstellar medium density they encounter will vary. A planet’s habitability requires the star’s astrosphere to cover the planet’s orbit about its star, with the just-right level of protection—neither too much stellar radiation for life nor too little, all within a region that simultaneously and continuously overlaps the liquid water, ultraviolet, photosynthetic, ozone, and tidal habitable zones.

For a solar-mass star, a close encounter with a dense molecular cloud will at least temporarily shrink that star’s astrosphere to a size smaller than the overlapping set of habitable zones (

Smith and Scalo 2009). Such encounters may explain some of the mass extinction events in Earth’s fossil record.

6.7. Electric Wind Habitable Zone

The Venus Express spacecraft measured the electric potential in Venus’ ionosphere (

Collinson et al. 2016). It was 10 volts. As Collinson and his colleagues demonstrated, this electric potential is sufficient by itself to expel all Venus’ atmospheric ions lighter than atomic weight 18 into interplanetary space. These ions include O

+ and all water group ions. While the solar wind and a runaway greenhouse effect contributed to making Venus bone dry, Venus’ atmospheric electric field proves to be the dominant desiccating factor.

The Venus Express research team showed that Venus’ proximity to the Sun explains its strong atmospheric electric field. Venus receives twice as much solar uv radiation as does Earth. This radiation produces a high density of free electrons and ions in the Venusian atmosphere, which produces the strong electric field. As the team noted, such a strong electric ionospheric field “has profound implications for our understanding of atmospheric loss processes for all planets” (

Collinson et al. 2016, p. 5931). All planets with atmospheres that receive more uv radiation from its host star than Earth receives from the Sun will experience some degree of oxygen and water loss. Moreover, this desiccation likely will occur before the host star’s luminosity is sufficiently stable and its radiation and wind sufficiently benign for life to possibly exist on the planet.

All planets orbiting M- and K-type stars within the liquid water habitable zone lie outside the electric wind habitable zone. This criterion alone eliminates 88 percent of all stars from possibly hosting habitable planets (

Ledrew 2001).

6.8. Eccentricity Habitable Zone

All planets orbit their host stars along an elliptical path. All moons orbit their host planets on elliptical paths. Eccentricity is defined as the departure of the orbital ellipse from circularity. For a perfect circle, the eccentricity equals zero. For a parabola, it equals one. For an ellipse, the eccentricity equals the distance from the center of the ellipse to one of the foci divided by the semi-major axis of the ellipse (see

Figure 1).

The orbital eccentricity affects the amount of radiation a planet receives from its host star at different points along the orbit. Planets with orbital eccentricities greater than 0.06 cannot simultaneously remain in the liquid water, ultraviolet, tidal, astrosphere, photosynthetic, and ozone habitable zones throughout their orbit, where habitability is defined as what is necessary for the existence of complex animal life (see

Section 6.1,

Section 6.2,

Section 6.3,

Section 6.4,

Section 6.5 and

Section 6.6). For eccentricities beyond 0.06, the greater the eccentricity the longer the time per orbit a planet resides outside one or more habitable zones.

The latest encyclopedia of known planets outside the solar system (exoplanets) has 7884 entries (

Exoplanet TEAM 2025). The number of planets in the catalog with measured or estimated orbital eccentricities is 3397. Of these 3397, 53 percent possess orbital eccentricities greater than or equal to 0.06 and 43 percent greater than or equal to 0.10.

6.9. Rotation Rate Habitable Zone

A planet’s rotation rate affects the reflectivity of its clouds, which determines how much of the host star’s heat and light reaches the planetary surface. The more rapidly a planet rotates the narrower the bands of clouds at low latitudes (

Yang et al. 2014). These narrower equatorial cloud belts reflect less of the host star’s heat and light. Thus, they cause the planet’s surface to reach higher average temperatures.

A planet’s rotation rate, therefore, alters the positions and widths of other habitable zones. For example, the faster the rotation rate, the more distant from the host star the liquid water, ultraviolet, photosynthetic, and ozone habitable zones.

6.10. Obliquity Habitable Zone

Obliquity is the tilt of a planet’s rotation axis relative to its orbital axis. Climate simulation studies show that the higher the obliquity, the warmer the planet’s global mean surface temperature (

Jenkins 2000). For planets with oceans and continents, high obliquity warms the oceans while cooling the continents.

As with a planet’s rotation rate, its obliquity alters the positions and widths of other habitable zones. For example, greater planetary obliquity pushes the liquid water, ultraviolet, photosynthetic, and ozone habitable zones outward from the host star.

6.11. Obliquity Stability Habitable Zone

Computer simulations of obliquity variations for known and hypothetical exoplanets found that the greater the differences in orbital inclinations (angle between a planet’s orbital plane and the host star’s equatorial plane) among the planets in a planetary system the greater the obliquity variations in the individual planets (

Deitrick et al. 2018b). The simulations also revealed that the larger a planet’s initial orbital inclination and/or initial orbital eccentricity the greater were future obliquity variations. In the common event where one or more planets is ejected from the planetary system by gravitational disturbances from another planet or a passing star, the inclinations and orbital eccentricities of the remaining planets are boosted, resulting in their obliquity variations becoming greater.

For planets closer to their host stars than 0.5 AU, the obliquity variations can be small enough not to threaten the long-term existence of life. However, for a planet to reside in the liquid water, ultraviolet, tidal, astrosphere, and electric wind habitable zones, it must orbit more distantly than 0.9 AU. At that distance it is almost impossible for a planet small enough to be habitable to experience obliquity variations less than ±10°. Mars, for example, has obliquity variations ±16° (

Holo et al. 2018).

Earth’s obliquity variations are remarkably tiny, only ±1.2° over the past half billion years. This obliquity stability would not be possible unless Earth was orbited by a single gigantic, nearby moon such that the Moon’s tidal forces exerted on Earth’s equatorial bulge are about double that of the Sun’s. Even so, a small change in the Moon’s mass, up or down, would induce obliquity variations that would rule out diverse ecosystems, a large human population, and global civilization (

Waltham 2004). These consequences occur for obliquity variations as small as ±2.4°.

While a single large moon orbiting nearby a relatively small planet is a requirement for obliquity stability, it is not a sufficient requirement. Multiple features of the planet’s planetary system must also be fine-tuned (

Deitrick et al. 2018b).

The most significant consequence when obliquity variations for an otherwise habitable planet exceed ±2.4° is that they “cause the ice edge, the lowest latitude extent of the ice caps, to become unstable and grow to the equator” (

Deitrick et al. 2018a, p. 1). The planet is doomed to experience a runaway glaciation where the planet’s entire surface gets covered in ice. Since ice reflects the host star’s light and heat more efficiently than any other planetary surface cover, the glaciation likely will remain even when changes in the planet’s obliquity otherwise would warm the planet. The exception is where the planet’s obliquity variation is so large that the planet oscillates between all its surface water being evaporated into steam and all its surface water being frozen into ice. This scenario rules out habitability.

6.12. Orbital Eccentricity Stability Habitable Zone

Another set of computer simulations on known and hypothetical exoplanets showed that large orbital eccentricity variations for potentially habitable planets will be just as frequently generated as large obliquity variations (

Deitrick et al. 2018a, p. 1). A consequence of Kepler’s second law of motion (a line connecting a planet to its star sweeps out equal areas during equal time intervals) implies a planet moves faster when it is closer to its star and slower when it is farther away. Thus, a planet will spend more time when its orbital distance is farthest from its star than when it is nearest. In situations when the orbital eccentricity becomes large, the planet can completely freeze over when it is most distant from its star.

It is not either or. Large orbital eccentricity variations will be accompanied by large obliquity variations (

Deitrick et al. 2018a). Obliquity variations typically disturb a planet’s climate cycles more than orbital eccentricity variations. The exception is when eccentricity variations exceed ±0.1. For potentially habitable planets, large obliquity and/or orbital eccentricity variations will generate severe climate change on time scales of a few years. The obliquity and orbital eccentricity variations either will eradicate or severely narrow the liquid water habitable zone. Our solar system is exceptionally rare in that initial planetary orbital inclinations and eccentricities, spin–orbit resonances, and gravitational perturbations have not generated obliquity and orbital eccentricity variations large enough to make its one potentially habitable planet uninhabitable.

6.13. Carbon Dioxide Habitable Zone

Certain microbes can tolerate a wide range of carbon dioxide (CO2) concentrations in their planet’s atmosphere. However, complex aerobic life, especially animals cannot.

Photosynthesis shuts down when atmospheric CO

2 levels dip below 0.000153 bar (1 bar = 0.987 of atmospheric pressure of Earth at sea level). Large-bodied mammals and birds will starve to death at atmospheric CO

2 levels below 0.00018 bar. On the other hand, exposure to atmospheric CO

2 levels above 0.0051 bar, even for half a day, prove deleterious for mammals (

Occupational Safety and Health Administration 2021). Respiratory acidosis, ion buffering changes in internal body fluids, and circulatory arrest are just three biological consequences of elevated CO

2 levels (

Azzam et al. 2010). For marine ecosystems, atmospheric CO

2 levels as low as 0.00095 bar will generate acidification that will cause corals, echinoderms, mollusks, crustaceans, and fish to disappear (

Wittmann and Pörtner 2013).

The claim that the liquid water habitable zone can be very wide presumes atmospheric CO

2 can range from 0–20 bars (

Schwieterman et al. 2019). However, the range for aerobic animal ecosystems is limited to 0.00018–0.00095 bars. Therefore, for such life to possibly exist the liquid water habitable zone must be very narrow. For it to exist for more than a hundred million years requires an extraordinarily fine-tuned carbonate-silicate cycle to draw down atmospheric CO

2 at a near continuous fixed rate to compensate for the increasing brightness of the host star (

Kasting 2025). This fine-tuned draw down appears to only be possible for Earth-like planets with orbital distances between 0.982 and 1.18 AU (

Bonati and Ramirez 2021;

Levenson 2021;

Graham and Pierrehumbert 2024), high mantle abundances of thorium and uranium (

Oosterloo et al. 2021), and an ocean-to-land-area ratio comparable to the present Earth (

Höning and Spohn 2023).

6.14. Carbon Monoxide Habitable Zone

For animals with circulatory systems, carbon monoxide (CO) is highly toxic even at abundance levels as low as 9 parts per million (

Townsend and Maynard 2002). Neither can such animals exist with an atmospheric molecular oxygen level below 0.10 bar.

Planets orbiting stars less massive than the Sun will receive less near-uv radiation. With this deficit, even with no more than 0.10 bar of oxygen and low CO

2 levels in the atmosphere and even with abundant surface liquid water, so little OH (hydroxide) is produced in the atmosphere that the CO lifetime is greatly lengthened (

Schwieterman et al. 2019). Thus, for planets orbiting stars only slightly less massive than the Sun, there will be higher atmospheric CO levels than is the case for Earth.

Making this problem worse is the fact that certain simple lifeforms that must be abundant for complex aerobic life to exist produce CO (

Fichot and Miller 2010). Biomass burning (

Andreae and Merlet 2001;

Andreae 2019) and photolysis of dissolved organic matter in surface layers of oceans and lakes also pump CO into the atmosphere (

Conte et al. 2019). Consequently, planets orbiting stars less massive than the Sun will be uninhabitable for complex aerobic life.

6.15. Stellar Flares Habitable Zone

X-ray and ultraviolet (xuv) radiation from flares emitted by a planet’s host star can result in massive hydrogen loss via thermal escape and equally massive oxygen loss via non-thermal escape from a planet’s surface and atmosphere (

Airapetian et al. 2017). These losses can render an otherwise habitable planet bone dry within a few tens to hundreds of millions of years. These losses are especially substantial for planets with orbital distances less than 1.0 AU.

All stars within a half billion years after their birth emit frequent powerful xuv flares. Absent a robust, enduring powerful magnetosphere enveloping a potentially habitable planet, flares from its host star will erode away most of its atmosphere and all its surface and atmospheric water before the planet is even a half billion years old. (A magnetosphere, created by an active, stable interior dynamo, is the region of space surrounding an astronomical body in which charged particles are influenced by its magnetic field).

6.16. Coupled Magnetosphere Habitable Zone

This habitable zone is the most restrictive of all known habitable zones. Not only do stars during their first half billion years emit intense gamma-ray, X-ray and uv radiation, they also discharge streams of energetic particles. The combination of this radiation and particles efficiently and rapidly sputters away the atmosphere and surface water of any potentially habitable planet that is not enveloped by a powerful magnetosphere. Analysis of 9+ years of data from the Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution (MAVEN) spacecraft that orbits in Mars upper atmosphere and ionosphere showed that sputtering rates are more than four times higher than stellar model predictions and are especially elevated during stellar storm events (

Curry et al. 2025). Measurements of stellar activity levels reveal that the Sun has the lowest sputtering rate of any known star (

Maehara et al. 2012;

Reinhold et al. 2020).

Earth possesses a powerful magnetosphere, but even its magnetosphere is not up to the task of protecting Earth’s atmosphere and surface water from being sputtered away by the youthful Sun. What allowed Earth to eventually host life was the extraordinary Moon-forming event and the coupling, that is, joining together, of the magnetospheres of Earth and the Moon during the first half billion years of the Earth-Moon system.

Earth’s moon did not form like other moons. It formed as an outcome of the collision-merger between Theia, the solar system’s fifth rocky planet that was about twice Mars’ mass, and the proto-Earth (

Canup and Asphaug 2001;

Canup et al. 2023). The residual heat from that collision-merger kept the Moon’s iron core in a liquid state up until 3.9 billion years ago.

The Moon’s proximity to Earth during its first half billion years provided the convection currents to circulate the liquid iron in its core. The pull of Earth’s gravity on the Moon’s near side was substantially stronger than on its far side. This difference caused the Moon to wobble. (A much smaller wobble persists to this day). This wobbling circulated the liquid iron in the lunar core, producing the Moon’s early strong magnetic field and enshrouding magnetosphere. Analysis of lunar rocks has affirmed that 4.4–3.9 billion years ago the Moon’s maximum magnetic field strength was the same as Earth’s (

Mighani et al. 2020). Similarly, the pull of the Moon’s gravity on Earth circulated the liquid iron in Earth’s core. Consequently, both the youthful Earth and Moon were enshrouded by powerful magnetospheres.

While the present-day Moon is separated from Earth by 384,000 km or 30 Earth diameters, some 4.0 billion years ago, the two bodies were separated by a mere 114,700 km or 9 Earth diameters (

Zharkov 2000;

Farhat et al. 2022;

Farhat et al. 2023). The proximity of the Moon and Earth to one another before 4.0 billion years ago brought about a coupling of the two bodies’ magnetospheres (

Green et al. 2020).

The coupling of the magnetospheres of Earth and the Moon provided a magnetic shield of sufficient strength and size to prevent the blast of particles and radiation from the Sun previous to 4.0 billion years ago from sputtering away all Earth’s atmosphere and surface water. Without the added boost from joining forces with the Moon’s magnetosphere, Earth’s magnetosphere would have been too weak to a protect the young planet.

After 3.9 billion years ago, the Moon’s magnetic field became too weak and the Moon too distant from Earth to provide significant magnetospheric protection for Earth’s atmosphere, hydrosphere, and life. However, since 3.9 billion years ago, the protection necessary to retain these life essentials had lessened considerably. The Sun’s flaring activity, particle outflows, and intensities of gamma-ray, X-ray, and ultraviolet emission had dramatically declined to levels so that Earth’s magnetosphere, by itself, provided adequate protection.

The team that discovered and determined the nature of the early Earth-Moon coupled magnetosphere concluded that it is “relevant not only for the study of the early Earth and Moon but also for the habitability of exoplanets” (

Green et al. 2020, p. 4). The implication of the coupled magnetosphere habitable zone is that for any planet to host life more complex than a few primitive microbial species for more than a few million years, it needs to be part of a planet-moon configuration nearly identical to the Earth-Moon system with a nearly identical dynamical and magnetic history. It is important to add that such a planet-moon system also must orbit a star with a mass nearly equal to the Sun’s, given that stars more massive or less massive than the Sun pose a significantly greater risk to the sputtering away of any nearby planet’s atmosphere, hydrosphere, and, thus, to life.

7. ETI Galactic Habitability Requirements

Just as there are known planetary habitable zones, there are known galactic habitable zones. A galactic habitable zone is a region within a galaxy where a planet or moon must reside for that planet or moon to possibly host life (

Gonzalez et al. 2001;

Lineweaver et al. 2004). As with planetary habitable zones, the galactic habitable zones are very much smaller for advanced life than for microbial life. Likewise, for a planet or moon to be truly habitable it must simultaneously reside in all the known galactic habitable zones.

So far, astronomers have discovered 5 galactic habitable zones:

7.1. Co-Rotation Distance Habitable Zone

The first discovered galactic habitable zone was the co-rotation distance habitable zone. Newton’s laws of motion determine the rate at which stars revolve around a galaxy’s center. The greater a star’s distance from the center the longer it takes to make one revolution around it. Galactic density waves (

Feitzinger and Schmidt-Kaler 1980;

Bobylev et al. 2008;

Griv et al. 2025) determine the rotation rate of the spiral arm structure.

The farther is a star from the galaxy’s co-rotation radius (the distance from the galactic center where stars revolve at the same rate as the spiral structure rotates), the more frequently that star crosses a spiral arm. Spiral arm crossings are hazardous to life. Spiral arms are filled with young supergiant stars, giant molecular clouds, and star-forming nebulae that shower their vicinities with deadly radiation. These stars, clouds, and nebulae also gravitationally disturb any nearby planetary system’s asteroid-comet belts, unleashing an enhanced bombardment on those planets. Only stars near the co-rotation radius avoid frequent spiral arm crossings.

The co-rotation radius is different for each spiral galaxy. It depends upon the galaxy’s total mass, stellar mass, gas mass, bulge mass, magnetic field, and stellar disk dimensions. For the Milky Way Galaxy (MWG), the co-rotation radius is far enough from the galactic center that planetary systems near the co-rotation radius will not be exposed to sterilizing radiation from the galactic nucleus. However, any planetary system forming much farther out from the co-rotation radius will be unable to accrete sufficient quantities of life-essential heavy elements. The reasons why are that the density of matter in the galactic disk decreases with distance from the galactic center and the ratio of heavy-to-light elements varies with distance from the galactic center in a complex manner (

Mishurov et al. 2002).

The safest place for life would not be exactly at the co-rotation distance. A planetary system in that precise place would experience chaos from destructive mean-motion resonances (

Voglis et al. 2006). The safest orbital distance would be just inside the co-rotation radius. The Sun orbits the center of the MWG at 98 percent of the co-rotation radius (

Dias et al. 2019) (see

Figure 2).

Just inside the co-rotation radius the star density is at a minimum (

Barros et al. 2013;

Barros and Lépine 2014). This is the optimal location for intelligent physical life to launch and sustain civilization.

7.2. Black Holes Habitable Zones

Advanced life requires a safe distance from the supermassive black hole (SMBH) that resides in the nucleus of every large galaxy. For the MWG the safe distance is anywhere beyond just inside the co-rotation radius. Advanced life also requires safe distances from stellar-mass black holes that are consuming matter. For spiral galaxies, nearly all such black holes reside either in the arms or the nucleus.

Animals cannot exist without r-process elements. R-process elements form when lighter elements rapidly capture neutrons (

Lee et al. 2022). Such rapid neutron capture needs a dense stream of fast-moving neutrons that only core-collapse supernovae and neutron star merging events provide. The larger the initial masses of merging neutron stars, the greater the production of r-process elements. Neutron star mergers where the combined mass of the merging neutron stars exceeds 2.5 times the Sun’s mass, considerably less where the neutrons stars’ interiors are elastic, result in black holes (

Bauswein et al. 2020).

Stars with masses greater than 25 times the Sun’s mass will enter the core-collapse phase and end up as black holes (

Heger et al. 2003;

Côté et al. 2016). Stars with masses 10–25 times the Sun’s mass have a high likelihood of entering the core-collapse phase and in doing so will eject much greater quantities of r-process elements into the interstellar medium than stars more massive than 25 times the Sun’s mass (

Yutaka et al. 2014).

Essential for animals’ existence are adequate quantities of nickel, copper, zinc, arsenic, selenium, molybdenum, iodine, and tin. For such quantities of these elements to be available for animals it is crucial that the host planet or moon form in a region of the galaxy where black hole forming events (neutron star mergers and/or core collapse supernovae) are frequent and nearby. Roughly, the greater the distance from the galactic center the fewer the number of core collapse supernovae and neutron star merging events. Therefore, for animal life to be possible, the host planet or moon must form in the inner, not the outer, part of its galaxy.

For all galaxies, the black hole habitable zone and the co-rotation distance habitable zone fail by a wide margin to overlap. For example, in the MWG the region where a planet can be adequately enriched with the r-process elements that animals need is considerably interior to the co-rotation radius. Nevertheless, the solar system is far more enriched with r-process elements than its present location in the MWG would permit. (Heavy element abundance takes a significant dip at the co-rotation radius (

Mishurov et al. 2002)).

The solution to this enigma is that the black hole habitable zone is not one zone, but two zones separated in time and space. The condition that the host planet be adequately enriched with r-process elements must be met before the origin of life. The condition that the host planet be distant from deadly radiation from neutron star merging events, core collapse supernova events, and black holes must be met after the origin of life. The two conditions can be met if the host planetary system forms inside the zone rich in r-process elements and migrates shortly thereafter into the co-rotation distance habitable zone that also happens to be sufficiently distant from deadly radiation from black holes, neutron star mergers, and core collapse supernova events.

This scenario requires a spiral galaxy fine-tuned in size, mass, stellar population, and stellar distribution. It also requires a planetary system to form at a fine-tuned location in the galaxy and after being enriched in r-process elements to migrate from its birth location to just inside the co-rotation distance and remain at that location undisturbed for a few billion years.

Astronomical observations and research studies affirm that this scenario was played out for the solar system. The Sun is part of the G-dwarf problem. In the Sun’s local neighborhood there are two diverse populations of G-dwarf stars (

Jorgensen 2000;

Caimmi 2008). One has a distinctly low abundance of heavy elements that show similarities with stars in our galaxy’s halo. The second, like the Sun, has a distinctly high abundance that show similarities with stars in our galaxy’s central bulge (

Caimmi 2008). The second population also is older on average than the first population. This age difference makes the elemental abundance difference greater since our galaxy’s heavy element abundance increases with its age. The difference in heavy element abundance indicates that the two populations did not form in the same region of the galaxy. The first population apparently formed in a region of our galaxy where few, if any, neutron star merging and core collapse supernova events occurred, while the second population apparently formed in a different region of our galaxy where many neutron star merging and core collapse supernova events occurred. This scenario is well explained if the majority population formed where they are presently located just inside the co-rotation distance and if the minority population formed in a dense cluster of about 20,000 stars (

Arakawa and Kokubo 2023) just beyond our galaxy’s central bulge and got strongly ejected from the cluster shortly after they were enriched with heavy elements to end up in their present location (

Schönrich and Binney 2009;

Minchev and Famaey 2010;

Wang and Zhao 2013). This scenario also explains how Earth ended up with such an extreme abundance of the r-process elements uranium and thorium.

Figure 3 shows the required migration route. For advanced life to be possible on any other planetary system, something similar to this scenario must have played out.

7.3. Ejection Distance Habitable Zone

This galactic habitable zone is a consequence of the black hole galactic habitable zone. For advanced life to be possible, the host planetary system needs to form at a distance from the galactic center where the planet can be adequately enriched in r-process elements. Once the required enrichment has been achieved, the planetary system must be ejected from that location then stop and settle in just inside the co-rotation distance, on the condition that for the host galaxy, just inside the co-rotation distance also is a region distant enough from radiation sources problematic for animals and intelligent physical life.

The timing of the ejection must be fine-tuned. The ejection distance also must be fine-tuned.

7.4. Star Density Habitable Zone

The density of stars in a spiral galaxy decreases with distance from the galactic center. For advanced life to be possible in a planetary system, the system must be distant from regions with high star density and reside in a region of exceptionally low star density. Only then can the planetary system be isolated from radiation and gravitational disturbances that would be survival issues for animals and intelligent physical life. While these conditions are met in the outskirts of spiral galaxies, those outskirt locations are well outside the co-rotation distance, black hole distance, and ejection distance habitable zones.

7.5. Bubble Habitable Zone

This galactic habitable zone is a consequence of the star density habitable zone and the co-rotation distance habitable zone plus the need for protection from cosmic rays. For galaxies where the co-rotation distance, black hole distance, and ejection distance habitable zones overlap one another and are all compatible with one another, the star density habitability criterion requires that the planetary system sit inside in a large bubble that resides just inside the co-rotation distance.

Magnetized cavities, termed galactic bubbles, are voids of exceptionally low gas and dust density that are a few hundred light years in diameter. These bubbles are carved out by co-moving groups of near simultaneous supernova eruptions (

Fuchs et al. 2006;

Pelgrims et al. 2020). By impacting the directionality of cosmic rays and producing cosmic ray diffusion (

Gebauer et al. 2015), the magnetized bubbles mitigate to a substantial degree damage to advanced life from cosmic radiation. The bubbles, though, are temporary, lasting just a few tens of millions of years (

Fuchs et al. 2006;

Zucker et al. 2022;

Siegert et al. 2024). For an advanced civilization to be possible the host planet must reside in such a bubble at the just-right time where the bubble is situated just inside the co-rotation distance.

Other galactic features can impact the planetary habitable zones. For example, nearby supernovae, supergiant stars, magnetically active stars, and/or stellar mass black holes can shrink the ultraviolet planetary habitable zone.

8. ETI Stellar Habitability Requirements

For advanced life to exist, its host star’s age must fall within a narrow range. Human beings or their functional equivalents need fine-tuned atmospheric oxygen, carbon dioxide, nitrogen, and water vapor levels. They need plentiful vegetation with efficient photosynthesis. They need their planet to be richly endowed in biodeposits, for example, topsoil, limestone, gypsum, coal, oil, and natural gas. They need surface metal deposits to be largely insoluble, not soluble, which requires at least a 2-billion-year period of an enormous abundance and diversity of sulfate-reducing bacteria (

Logan et al. 1995;

Ross 2016, pp. 132–34;

Sabuda et al. 2020). They need radiation from potassium-40, uranium-235, uranium-238, and thorium-232 in their planet’s crust to decay to a level neither too high nor too low for large-bodied mammals with long lifespans (

Upton 2001;

Mitchel et al. 2003;

Liu 2006;

Doss 2018;

Sosin et al. 2024;

Sutou 2025). All these needs imply a 3+ billion-year-history of non-advanced life that precedes advanced life.

All stars get progressively brighter as their nuclear furnaces fuse hydrogen into helium. For example, presently the Sun is about 23% brighter than at the time of life’s origin. However, life can tolerate at most only a 2% change in the host star’s brightness before being driven to permanent extinction (

Hart 1979). On Earth, this catastrophe was avoided because different life at different times in Earth’s history regulated the rate at which the silicate-carbonate cycle removed heat-trapping greenhouse gases from the atmosphere (

Ross 2016, pp. 159–64;

Hakim et al. 2019). As the Sun brightened, the reduction in greenhouse gases in Earth’s atmosphere perfectly compensated for the Sun’s brightening so that Earth’s surface temperature remained optimal for life.

Future compensation, though, will require the reduction in atmospheric carbon dioxide to a level below that which is minimal to sustain photosynthesis. Advanced life cannot be sustained without photosynthetic vegetation. Within only a few million years Earth’s surface either will be too warm for large-bodied advanced animals or contain too little atmospheric carbon dioxide to host abundant photosynthetic vegetation.

There also is a looming atmospheric oxygen problem. Future deoxygenation of Earth’s atmosphere and the atmospheres of Earth-like planets is an inevitable consequence of nuclear-burning stars becoming increasingly more luminous (

Ozaki and Reinhard 2021).

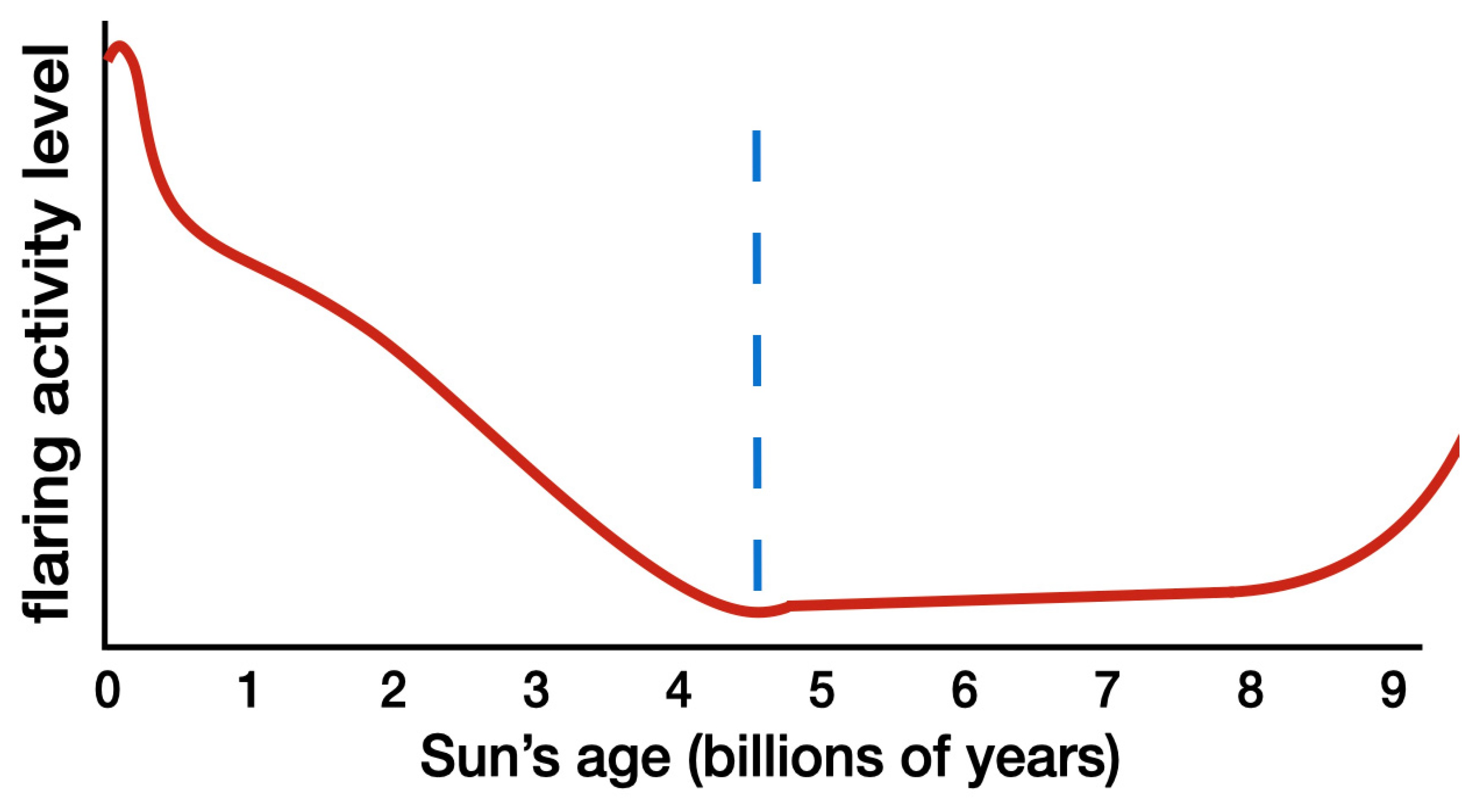

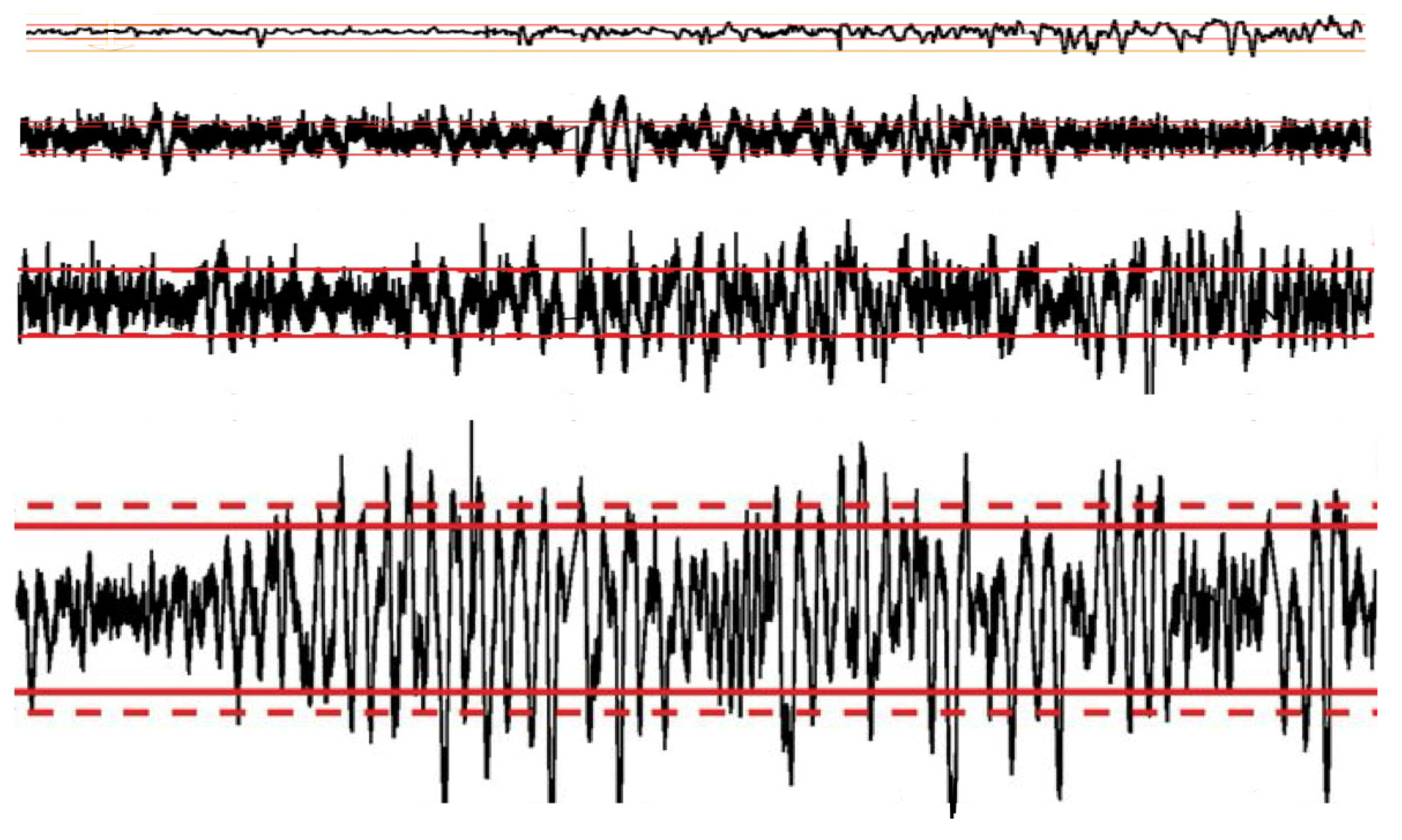

Therefore, for a star to host a planet on which advanced intelligent life can exist, its age must be within about 100 million years of the Sun’s present age. For advanced intelligent life that sustains global civilization the host star’s age must be within about 10 million years of the Sun’s. This age range constraint is a consequence of intelligent life and its civilization requiring a host star with exceptional luminosity stability (required for planetary climate stability) and minimal flaring activity (see the following five paragraphs and

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

All nuclear burning stars produce flares, powerful explosions from the release of magnetic energy near starspots. An exhaustive analysis of catalogs of solar and stellar flares shows that the Sun and solar-type stars share the same physical process in the spot-to-flare activity (