Turkish Religious Music in the Funeral Ceremonies of Sufi Orders †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Framework

3. Methodology

4. Findings

4.1. The Meaning of Music Between Death and Life According to Sufis

4.2. Funeral Ceremonies in Sufi Orders

4.3. Religious Music at Sufi Order Funerals

4.4. Religious Music in Funeral Ceremonies of Mawlawī Order

- “O beloved, with your face adored by thousands of lovers

- Thousands of lovers have turned towards you

- O Sufi of the pure-hearted

- From your soul, say Allāh Hû

- O lover of faithful love

- From your soul, say Allāh Hû”

- (Ey âşık-ı rûy-i tû hezârân âşık

- Rû kerde be-sûy-i tâ hezârân âşık

- Ey sûf-i ehl-i safâ

- Ez can bigû Allāh hû

- Vey âşık-ı aşk-vefâ

- Ez can bigû Allāh Hû)

4.5. Religious Music in Funeral Ceremonies of Bektashī Order

- “With the permission of the Pir… In the name of the Shah… Allāh Allāh…”

- For our can (soul) who has passed on to the Al-Ḥaqq;

- The eyes of the body have reached the secret,

- May they reach the Al-Ḥaqq with the eyes of the Can (Soul).

- Hû to the Truth!”

- (Destur-u Pir… Bismişah… Allāh Allāh…

- Hakk’a yürüyen canımızın;

- Ten gözleri erdi sırra,

- Can gözüyle Hakk’a vara.

- Gerçeğe Hü!)

- “May the tongues that say ‘Allāh EyvAllāh!’ be spared from sorrow, grief, pain, and suffering.

- May the given consents be accepted in the Court of Al-Ḥaqq, Muhammad, and Ali.

- May all our souls that have passed on to Al-Ḥaqq have an eternal/easy cycle!”

- (“Allāh EyvAllāh!” diyen diller dert, keder, ağrı, acı görmeye.

- Verilen rızalıklar, Hakk, Muhammed, Ali Diva-nı’nda kabul ola.

- Hakk’a yürüyen cümle canlarımızın devr-î daim/devr-î asan ola!”)

- “With the permission of the Pir… In the name of the Shah… Allāh Allāh…

- To the rose-like countenance of Muhammad,

- To the perfection of Hasan and Hussein,

- To the path of Ali the Chosen,

- Allāh is friend, EyvAllāh Hû!”

- (“Destur-u Pir… Bismişah… Allāh Allāh…”

- Muhammed’in gül cemaline,

- Hasan’la Hüseyin’in kemaline,

- Aliyyel Murtaza’nın yoluna,

- Allāh dost eyvAllāh Hü!)

- “Permission from the Pir… In the name of the Shah… Allāh Allāh…”

- We performed this service; for the love of Al-Ḥaqq, Muhammad, Ali,

- We performed this service; for the love of our Mother Fatima, Bozatlı Hızır,

- We performed this service; for the love of our Pir Hünkâr Hacı Bektaş Veli,

- We performed this service; for the love of Hallaj Mansur, Seyyid Nesimi,

- We performed this service; for the love of Abdal Musa, Kaygusuz Sultan,

- We performed this service; for the love of Kalender Çelebi and all saints,

- We performed this service; for the love of the soul that has returned to Al-Ḥaqq,

- For the unity of Al-Ḥaqq, Muhammad, Ali,

- For the spiritual guidance of Hünkâr Hacı Bektaş Veli,

- To the moment of true saints, Hu!

- (“Destur-u Pir… Bismişah… Allāh Allāh…”

- Eyledik bu hizmeti; Hak, Muhammed, Ali aşkına,

- Eyledik bu hizmeti; Fatıma Anamız, Bozatlı Hızır aşkına,

- Eyledik bu hizmeti; Pirimiz Hünkâr Hacı Bektaş Veli aşkına,

- Eyledik bu hizmeti; Hallac-ı Mansur, Seyyid Nesimi aşkına,

- Eyledik bu hizmeti; Abdal Musa, Kaygusuz Sultan aşkına,

- Eyledik bu hizmet; Kalender Çelebi ve cümle evliya aşkına,

- Eyledik bu hizmeti; Hakk’a yürüyen can aşkına,

- Hak Muhammed Ali birliğine,

- Hünkâr Hacı Bektaş Veli Pirliğine,

- Gerçek erenler demine Hü!)

4.6. Religious Music in Funeral Ceremonies of Jarrahī Order

4.7. Religious Music in Funeral Ceremonies of Rifāʿī Order

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Appendix A.2

Appendix A.3

Appendix A.4

Appendix A.5

| Term | Academic Definition |

|---|---|

| Āyīn-i Sharīf | A major Mawlawī ritual-musical composition performed as part of the samā ceremony, characterized by a structured modal and rhythmic organization; frequently excerpted during funerary washing rites for sheikhs. |

| Alawī–Bektashī Nafas | Doctrinal poetic hymns central to Alawī-Bektashī ritual life, performed during death rites to articulate theological principles and communal identity. |

| Arakiye | A distinctively crafted ceremonial headgear placed upon the deceased sheikh or caliph before or during washing within the Jarrahī branch of the Halveti order. |

| Awrād-i Sharīfa | Canonical litanies belonging to a Sufi order, systematically recited in prescribed order during the three-stage ritual washing of the deceased (awrād, tawḥīd, ism-i jalāl). |

| Bektashī Order Cemal-Cemalelik (Jamāl-Jamāla) | A syncretic mystical tradition emphasizing the metaphysical interpretation of death as “Returning to al-Ḥaqq,” incorporating nafas, düvaz, devriye, and ritual supplications in funerary contexts. It is defined as a state of spiritual and bodily wholeness in which the individual, within Alevi social and ritual life, both becomes integrated with the community and reveals their own truth. |

| Janāza Gülbank | A formalized ritual prayer recited collectively following burial, serving as a benediction for the deceased; particularly canonical in Mawlawī and Bektashī funerary tradition. |

| Dâr’dan İndirme | A Bektashī reconciliation rite symbolizing the deceased’s posthumous spiritual and social rectification, incorporating nafas, düvaz, and communal assent (rıza). |

| Devran | A circular, rhythmically coordinated dhikr ritual performed in several Sufi orders; executed in subdued form during funerary proceedings. |

| Düvaz İmam | A devotional poetic genre venerating the Twelve Imams; integral to Alawī–Bektashī funerary ceremonies as an affirmation of lineage and spiritual authority. |

| Janāza Tawḥīd | A collective dhikr recited either during the carrying of the coffin or around the grave, emphasizing eschatological unity and spiritual solidarity. |

| Ghasl | The ceremonial purification of the deceased’s body, during which Sufi orders integrate hymnody and dhikr as symbolic enactments of spiritual transition. |

| Gülbank | A solemn, formulaic collective supplication performed at key ritual moments within Mawlawī and Bektashī traditions; central to death rites. |

| Hakk’a Yürümek | A theological expression in Alawī–Bektashī thought describing death as the soul’s return to ultimate Reality, rejecting the notion of annihilation. |

| Hû Dhikr | The rhythmic repetition of the divine pronoun “Hû,” representing the Absolute Being; common in funerary processions and post-burial rituals. |

| Ism-i Hayy | The divine name “al-Hayy” (The Ever-Living). Dhikr is shifted to this name immediately if a sheikh dies during a ceremony. |

| Ism-i Jalāl | The prolonged, modulated recitation of the name “Allāh,” typically forming the climax of the three-stage washing ritual. |

| Jarrahī Order | A Sufi lineage notable for its structured funeral rites, including specialized salā forms, solemn dhikr, and hierarchical positioning during processions. |

| Qabr Tawḥīd | A dhikr performed collectively at the graveside, immediately following burial, to affirm divine unity and invoke mercy for the deceased. |

| Kun | The command of “Be”. The Qurʾānic creative imperative interpreted in Sufi metaphysics as the primordial sound-melody underlying cosmic existence and the theoretical foundation of samā. |

| Mawt al-Ikhtiyārī | Voluntary Death. A Sufi pedagogical principle meaning “Die before you die,” referring to the annihilation of the ego prior to physical death through ascetic discipline. |

| Mawlawī Order | A major Sufi order rooted in the teachings of Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī, distinguished by its semā ceremony, ritual music (āyīn), and symbolic funerary practices. |

| Na‘t | A poetic genre praising the Prophet Muḥammad; recited in funerary washing rites, especially the Na‘t-i Mevlânâ in the Mawlawī tradition. |

| Nafas | Mystically instructive lyrical compositions in Alawī–Bektashī ritual life, conveying metaphysical concepts and performed during funeral ceremonies. |

| Rifā‘ī Order | A Sufi order recognized for intense dhikr and devran rituals, employing distinctive hymns in funerary settings, particularly those glorifying Seyyid Ahmed Rifā‘ī. |

| Salā | A melodic call, frequently performed from minarets, used to announce a death and accompany the transportation of the body in funeral rites. |

| Samā | A ritual of spiritual audition and movement; in Mawlawī symbolism, it embodies metaphysical resurrection and the ascent of the soul following bodily death. |

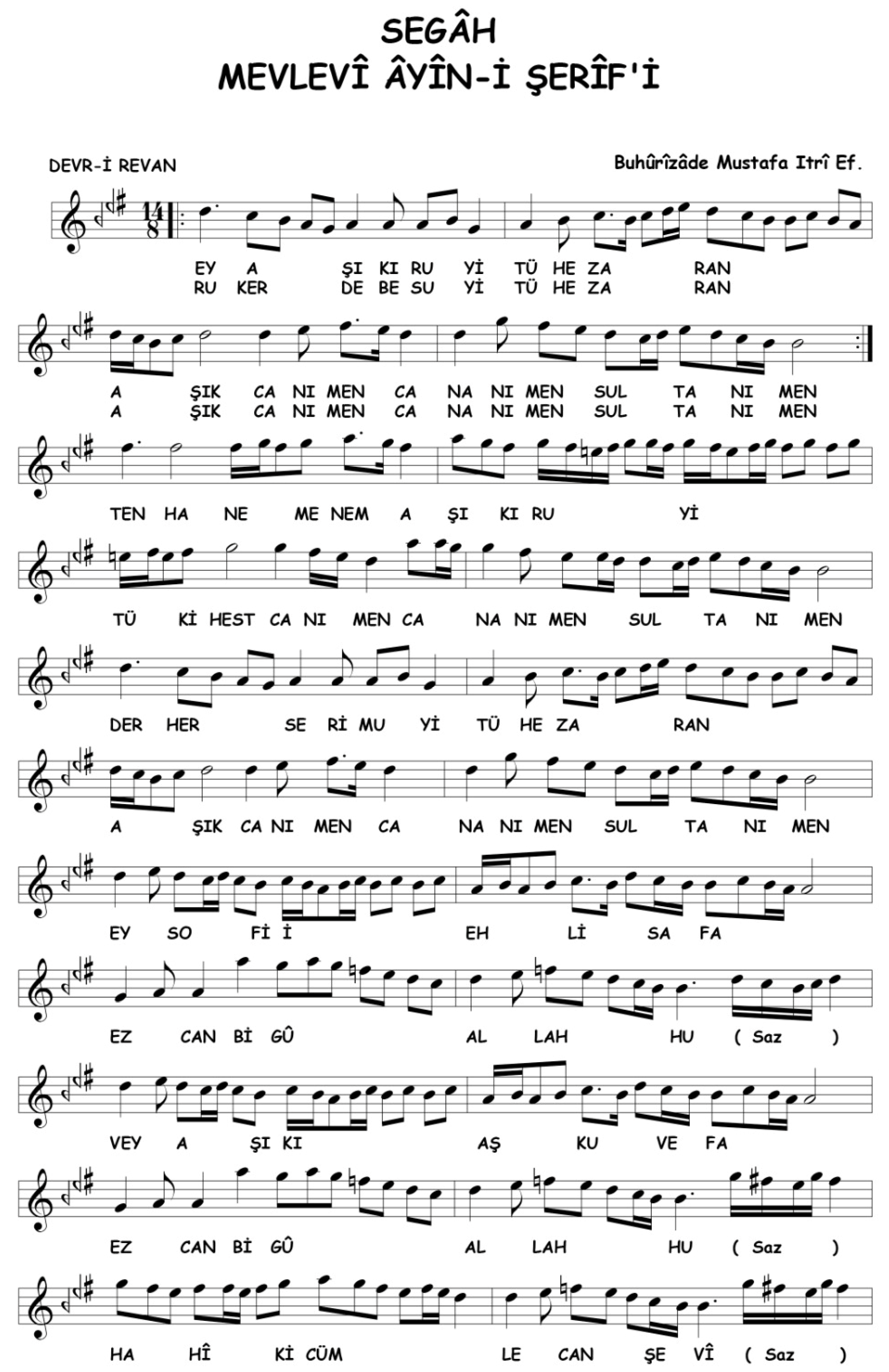

| Segāh Āyīn-i Sharīf | One of the principal Mawlawī musical compositions, historically performed during the washing of deceased sheikhs, containing Rūmī’s elegiac verses. |

| Tarīqa | Sufi Order. A structured system of spiritual training within Sufism, encompassing ritual practice, musical repertoire, and esoteric pedagogy; the article studies four: Mawlawī, Bektashī, Jarrahī, and Rifā‘ī. |

| Kalima-i Tawḥīd Kalima al- Tawḥīd | The formula “Lā ilāha illā Allāh,” performed melodically in funeral rites to reinforce theological unity and prepare participants for the metaphysical dimensions of death. |

| Tekke Wuṣlat | Sufi lodge The Sufi conceptualization of death as mystical union with the Divine (al-Ḥaqq), forming the interpretive framework for Sufi funerary aesthetics. |

| 1 | While Sufism provides the human being with a spiritual elevation, mysticism is characterized by transient and passing states of ecstasy. In mysticism, “suffering” (istirāp) is of central importance, whereas in Sufism suffering does not hold a special place. The disciplinary methods in Sufism vary according to individual temperament, a diversity that is not present in mysticism. In Sufism, spiritual advancement requires personal effort; in mysticism, such a requirement does not exist. A mystic is solely a person of ecstasy (a state of spiritual rapture), whereas a Sufi seeks both ecstasy (wajd) and knowledge (‘ilm). Unlike mysticism, Sufism is grounded in dhikr and in accompanying the spiritual master (sohbet). While the aim in Sufism is to purify the soul and guide it toward union with the Divine (Wuṣlat al-Ḥaqq), in mysticism the emphasis lies on the soul’s domination over the body (Yılmaz 2004, p. 14) |

| 2 | In Western religious studies, the term ‘God’ is commonly used, whereas in Turkish and Arabic Islamic studies, the term ‘Allāh’ is used instead. I preferred the Islamic tradition and used the term Allāh. Al-Ḥaqq (الحقّ), ‘the Absolute Truth’, is one of the names of God in the Qurʾān. Sufis prefer this to indicate Allāh. |

| 3 | Fanā: This term denotes the servant’s annihilation of the carnal and animalistic desires of the nafs, the loss of self-awareness through a state of spiritual ecstasy, and the dissolution of one’s capacity for discernment. It further signifies becoming effaced from created things (ashyāʾ) due to being wholly preoccupied with the Divine Reality in which the self is continually annihilated (Kelâbâzî 1992, pp. 182–83). |

| 4 | Baqā: Following fanā, baqā refers to the servant’s subsistence in that which pertains to the Divine after having become annihilated in all that pertains to the nafs. In other words, it denote (Kelâbâzî 1992, pp. 182–83). |

| 5 | It is a Sufi term referring to a mystic’s ability to hear things both outwardly (ẓāhir) and inwardly (bāṭin). Samā in Turkish Sema; Persian سَماع is a Sufi ceremony performed as part of the meditation and prayer practice dhikr. This term denotes an act of perceptive audition, whereas dhikr corresponds to a remembrance practice rooted in wajd (ecstasy) (Ceyhan 2009, pp. 455–57) Although samah does not completely correspond to the Samā in Mawlawī Sufi order, in Bektashī tradition it is a special Sufi ritual called samah, performed as a ceremony with similar thoughts and emotions. |

| 6 | Since Sufis describe Sufism as an ‘ilm al-ḥāl’, which refers to address a person’s spiritual state (Yılmaz 2004, p. 14). I also preferred to use the expression ‘ilm al-ḥāl’ here (Yılmaz 2004, p. 14). |

| 7 | The first feature perceived in the Qur’ān’s nazm is its sonic structure, which produces an aesthetically pleasing harmony to the ear. The distribution of vowels (ḥarakāt), rests (sukūn), elongations (madd), and nasalizations (ghunna) is so balanced and varied that it evokes a continual sense of freshness and rhythm for the reciter. This structure reveals the superiority of the Qur’ān’s sound pattern and its unique musical impact (Çağıl 2015, pp. 330–31). The Qur’ānic texts possess a distinctive harmony of their own. As can be understood from this, the vocal rendering of the Qur’ān and the inherently rhythmic nature of its texts naturally lead to an association between Qur’ānic recitation and music. This association, however, has given rise to various debates due to differing perspectives on bringing together music and sacred texts. As al-Faruqi emphasizes, Qurʾānic recitation cannot be regarded as an uncomplicated musical performance. Rather, it is executed as a vocal art grounded exclusively in the human voice, performed freely and without instrumental accompaniment (Al-Faruqi 1985, pp. 20–25). In light of Faruqi’s rationale, Qurʾānic recitation, within a comparable conceptual framework, may be situated among the sacred (maʿbed) forms of Turkish religious music (Al-Faruqi 1985, pp. 20–25). |

| 8 | Ṣalā is a form in Turkish religious music. ṣalā (ṣalāt), meaning “supplication” and “prayer” in Arabic, refers to religious compositions recited in a melodic or free form that convey invocations of mercy and peace upon the Prophet Muhammad, praise him, and request his intercession. In Ottoman culture, numerous salâ texts emerged within the tradition of invoking blessings upon the Prophet. These Arabic-language compositions were named according to the time and context in which they were recited, such as the morning ṣalā, the Friday and Eid ṣalā, and the funeral ṣalā. In detail the salāt u salām recited freely and spontaneously in a melodic form from the minaret (known in everyday Turkish as salâ or selâ) appears in various forms, such as the funeral ṣalā, the Friday (Jum’a) ṣalā, and the Eid ṣalā. The salāt u salām recited in a melodic, composed form in the mosque or the tekke is known as salawāt, such as the ṣalāt-i ummiyyah, ṣalāt-i kamāliyya, and others (Özcan 2009, pp. 15–16). |

| 9 | In Sufi orders, both individual and collective forms of dhikr are performed in accordance with specific numerical sequences and prescribed ritual principles (erkân). The zâkirbaşı is the individual who leads the collective dhikr in the tekke and, by virtue of this role, stands as the head of the other zâkirs. Within the tekke setting, the term zâkirbaşı denotes the person who brings rhythmic cohesion to the ritual and, when necessary, encourages the darwishes in their dhikr through his knowledge of music (Olgaç 1995, p. 12; Çubukçu 2017, p. 1; Erdaş 2018, p. 12). For the details of zâkir in the Bektashī tradition: (Coşkun 2013, pp. 276–77). |

| 10 | The term “dede” is a spiritual title that carries different meanings across various Sufi orders in the history of Anatolian mysticism. Although the concept appears occasionally within the Bektashī order, the central office is that of the “baba.” In the Alawī–Bektashī tradition, however, “dede” refers to an individual authorized to provide religious guidance, conduct rituals (erkân), and offer spiritual leadership to the community affiliated with a particular ocak lineage. In Mawlawīsm—where the term is widely used—the title “dede” is bestowed upon an individual who, after completing 1001 days of service, undergoes the period of spiritual retreat (çile) and attains the rank of darwish, thereby becoming eligible to reside in a hücre (cell) (Uludağ 1994, pp. 132–33). |

| 11 | It is derived from the Arabic word “nagam.” It actually means “sound.” In Turkish Music, it is mostly used in the sense of “motif.” In this way, it refers to the part that forms the basis of the construction of a lahin (melodic) fragment. From sounds come nağme, from nağme come phrases, from phrases come sections (hâne), and from sections a complete musical work is built. Turkish: ezgi, ır; Persian: neva; Greek: melos; French: mélodie; English: melody; German: Melodie (Öztuna 1990, p. 96). |

| 12 | The art in which human emotions and thoughts are expressed through sound. Among the various views on the origin of the term mūsīqī (music), the most widely accepted is the view that traces it to the Latin musica. The root of musica, which is considered to derive from the Ancient Greek mousikē (from mousa, “muse”), is the word muse. In Arabic, the term appears as mūsīqā, while in Persian and Turkish it is pronounced as mûsikî (Özcan and Çetinkaya 2020, pp. 257–61). |

| 13 | It is the phenomenon in which the vibrations produced by a moving object are transmitted through a conductive medium and perceived by our auditory system. Sound is generated through the vibration of an object. It is expressed by the French term son, the English term sound, and the German term Klang (Say 2012, p. 475). |

| 14 | According to the Göktürk Inscriptions, in Turkish belief, the human soul takes the form of a bird or insect after death. This is why they say “flew away” for a deceased person. Even after accepting Islam, Western Turks say “şunkar boldu,” meaning “became a falcon,” instead of “died.” According to the Yakut Turks, when a person dies, the “kut,” or “soul,” leaves the body and takes the form of a bird. It perches on the branches of the “World Tree” that encompasses the universe. In Yakut belief, the soul can also take animal forms. The Mongolian Shaman has wings that allow him to transform into a bird. In the Orkhon Inscriptions and Divanü Lügati’t-Türk, heaven is described with the term “uçmak, uçmağ” (to fly). Alawīs, on the other hand, say for a deceased person “changed garment,” “migrated,” “returned to the God (Al-Ḥaqq),” or “rested the mold,” but never say “died.” (Eröz 1992, p. 68; Cemal 2006, p. 82). |

| 15 | “There are two main interpretations of death in Alawīsm. The first is “biological death”. They express biological death with terms such as “dying (ölme)”, “death (ölüm)”, “resting the mold”, and “returning to the Al-Ḥaqq”. Among these terms, “resting the mold” and “returning to the Al-Ḥaqq” stem from the belief that death is not an end, but the beginning of a new state. The mold mentioned here is the body, and the body has aged; it is tired or damaged. It is in a condition where it cannot fulfill its function. In this case, the body (mold) is abandoned. The one who leaves the mold came from God and will return to God. Therefore, it is said that one leaves the mold (returns to the Al-Ḥaqq) to reach God.” (Göde et al. 2015, pp. 67–68) |

| 16 | (Atasoy 2016, p. 398) In Turkmen tradition, instead of saying “death,” expressions such as: ‘He renewed his homeland’, ‘He returned his trust’, ‘He reunited with his owner’, ‘He attained God’s mercy’, ‘changing form’, ‘becoming a secret’, ‘returning the trust’, ‘reuniting with the Beauty and the Face (of God)’ are used. (Yıldız 2012, pp. 2–3) |

| 17 | In accordance with the 1924 Constitution—the founding constitution of the Turkish Republic—Law No. 677 on the Abolition of Darwish Lodges and Convents was enacted, resulting in the closure of all tekkes and zāviyas. See: Official Gazette, 13 December 1925. |

| 18 | It is observed that the practices carried out while the deceased is being taken to the cemetery in Sufi orders are generally expressed as reciting verses from the Qurʾān and remembering Allāh. “It is stated that the dhikr performed during the transportation of the deceased is often done loudly, sometimes while spinning, sometimes for a fee, and sometimes with the purpose of raising people’s awareness, especially when the funeral procession passes through crowded places like marketplaces, with loud voices and shouting.” In the fatwas given regarding the ruling of dhikr performed in this manner, it is advised to “remember Allāh with decorum and dignity, avoiding the loud dhikr which is considered makruh (disliked) by scholars.” It is also declared that “the testimony of those who perform dhikr while spinning and receive payment for their dhikr will not be accepted.” (Bıyık 2019, p. 305) |

| 19 | For fatwas regarding the permissibility of musical performance in Qurʾānic recitation, (Bıyık 2019, pp. 123–28) |

| 20 | Lyrics: A musical term used to denote the textual component of songs or poems. In Turkish music, it refers to the text/poem/güfte of both religious and non-religious compositions written in forms such as kâr, beste, semaî, şarkı, türkü, ilâhî, and nafas. The term söz, which carries the same meaning as the Persian-derived word güfte, is used in the sense of “a poem written to be set to music.” In Turkish religious music, however, the textual component of forms such as tekbir, teşbih, and salâ is referred to as the metin (“text”) (Özkan 1996, pp. 217–18.) |

| 21 | The holy name of the Divine Hu refers to Allāh’s absolute and unknowable essence, and is often used in dhikr and meditation in seeking to connect with the Divine Presence of the Absolute, and to transcend the self. The term “Hû” in the Bektashī tradition is vocalized as “Hü” in hymns, and in the literature, studies related to the Bektashī tradition also use it in the form “Hü” (Tatçı and Kurnaz 2016, p. 1). |

| 22 | Those standing at and around the grave collectively recite the Kalima al-Tawḥīd (Lā ilāha illā Allāh) in accordance with the ritual practice of the Sufi order. (Revnakoğlu 2003, pp. 245–46). |

| 23 | The term Alawī–Bektashī is widely used as an umbrella concept encompassing both Alawī culture and the Bektashī tradition. Although there are no major differences between Alawīsm and Bektashīsm in terms of beliefs and rituals, certain distinctions stemming from their social bases and lifestyles do exist. Therefore, in this study, I employ B Bektashī as an overarching concept and base my analysis on the funeral rituals of the Alawī–Bektashī tradition. |

| 24 | Gülbank is a Persian compound term meaning “sound of a rose.” It is a general expression used for a set of specially arranged prayers. Gülbank is a form in Turkish religious music. The word gülbank comes from Persian and means “the sound of the rose.” It refers to a fervently and loudly recited sequence of prayers and hymns, traditionally performed according to a specific order during various Sufi ceremonies (such as in Bektashī tradition, Mawlawī and Khalwatī Sufi orders), as well as in palace, guild, Janissary corps, mehter (Ottoman military band), and other ceremonial settings. The term also has usage examples carrying the meanings of shouting, the cry soldiers utter during battle, the sound of a nightingale, and good news (Ayverdi 2008; Uzun 1996, pp. 232–35; Öztuna 1990, p. 311). |

| 25 | Dede and Alawī–Bektashī Âşık/folk poet. |

| 26 | “Can” is a word claimed to be of Sanskrit origin. It passed from Sanskrit into Persian and, having acquired different meanings, came to be pronounced in similar ways across Eastern languages, including Turkish. It denotes meanings such as wind, soul, spirit, and the essential element that provides vitality to the body. In Arabic literature it is used with the meaning of rūḥ (spirit), while in Turkish and Persian literature—alongside the meaning of spirit—it is more commonly used to signify the element that gives the body its vitality. As a Sufi term, can may mean the human soul, as well as serve as a metaphor for the nafs-i raḥmānī and divine manifestations. In this article, however, it is used in the sense of ‘spirit.’ (Uzun 1993, pp. 138–39.) Here it is needed to clarify the concept of “rouh” (soul); The etymology of the concept of “ruh” (spirit) takes shape around the semantic fields of “breath,” “air,” “wind,” and “vitality” in various languages. Derived from the Arabic root r-w-ḥ ( ر -و- ح), rūḥ primarily denotes “breath” and “breeze.” Similarly, the Greek terms psyche and pneuma, the Latin spiritus and anima, the French âme, the German Seele, and the English soul all share semantic associations with “breath,” “air,” or a “life-giving force” (Uysal 2019, p. 22). In sum, can denotes the life-sustaining force, whereas rūḥ signifies the spiritual dimension of the human self. |

| 27 | Zakirbaşı of Jarrahī Sufi order (Karagumruk Tekke/Istanbul) |

| 28 | We do not have a definitive idea about the known composition of the work. There is an “Acemaşiran” composition of the piece, whose lyrics belong to Seyyid Nizamoğlu, recently made by Cüneyd Kosal. Another work with an unknown composer is in the “Bayatî” mode. Considering that Kosal lived in a later period, although not certain, we believe that the “Bayatî” composition fits the definition of “known composition” more appropriately. |

| 29 | “Âşık is someone who newly arrives at the tekke (darwish lodge), meets with the members of the tekke, and begins to inquire about the tekke’s customs. Mürid is the person who has started learning the rules of the tekke, essentially in the position of a student. Muhib is the individual whom the sheikh accepts into the tekke and grants membership status. Mutteki is elevated to a higher level by the sheikh, given more service and responsibility within the framework of the sincerity and maturity they have attained. Derviş is the title given to one whom the sheikh, after granting “ikrar” (avow), takes into his close circle and teaches the methods of the tarīqa, patience, and the etiquette of prayer, considering their services and loyalty over time. Nakib receives this title after learning the methods of the tarīqa and gains the authority to serve elsewhere. A person with the title of Nakib becomes a Sheikh. Sheikh prioritizes instruments such as dhikr, kudum, cymbals, and bend, but does not have the authority to grant darwish status; for Muhib, they have the authority to offer sherbet but not to grant “ikrar”. Sheikh (Caliph) possesses all the authorities of the Rifāʿī order. They combine duties such as awrād (litanies), dhikr, flag, kudum, cymbals (halile), can grant darwish status, and can train sheikhs.” Source Person: Kosova Rahovec Sheikh Haji Ilyas Efendi Dergah Sheikh Haji Abdulbaki Shehu Sheikh Haji Mehdi Shehu |

| 30 | Sheik Hacı Abdulbaqi Shehu Sheik Hacı Mehdi Shehu Cosova Rahovec Sheik (Hacı İlyas Efendi Dergahı) |

| 31 | This information belongs to a participant who wishes to remain anonymous (22 June 2025). |

| 32 | For information on the Rifāʿī devotions from a procedural and musical perspective, see (Erdaş 2023a, pp. 32, 52, 90–161) |

| 33 | Source: Sheikh Haji Abdulbaki Shehu and Sheikh Haji Mehdi Shehu of the Sheikh Haji Ilyas Efendi Darwish Lodge in Rahovec, Kosovo |

| 34 | Nevbe: The name of an instrumental ensemble and a rhythmic instrument that participates in various ceremonies performed in tekkes, accompanied by music played with rhythm instruments. (Agayeva 2007, pp. 37–38) |

| 35 | Kayyali: “It was founded by Ismail al-Meczûb al-Keyyâl, who was born in the village of Ümmüabîde. Sheikh Ismail left his homeland after the Mongols entered Iraq in 656 (1258 CE) and went to Aleppo, where he remained active until his death.” (Tahralı 2008, pp. 99–103) |

| 36 | The bandir is a traditional percussion instrument that is an indispensable part of Eastern music. Commonly used in folk music and classical music, the bandir also appears in different cultures around the world with similar structures. The bandir is a percussion instrument belonging to the family of frame drums. Bandir is traditional wooden-framed instrument for rthym. |

| 37 | Tashīf if; is an Arabic text read as a “nevbe sermon” in the Kayyali order. It is a form of seeking permission from the great figures of the order by mentioning their names and serves as an invitation to send blessings and prayers to the Prophet Muhammad. It does not have a melodic structure. (Erdaş 2023b, pp. 27–28) |

| 38 | The Nebevi section is the 2nd chapter where the word “Allāh” (the exalted name) is mentioned and the veil-lifting practice takes place. (Erdaş 2023b, p. 26) |

References

- Agayeva, Süreyya. 2007. Nevbe in Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi. İstanbul: TDV Publications, vol. 33, pp. 37–38. [Google Scholar]

- Akkuş, Mustafa Asım. 2023. Cerrâhîlik’te Dinî Mûsikî. Ankara: Fecr Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Faruqi, Lois Lamya. 1985. İslama Göre Müzik ve Müzisyenler. Translated by Taha Yardım. Exeter: Akabe Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Alvan, Türkan, and Mustafa Hakan Alvan. 2016. Saz ve Söz Meclisi. Istanbul: Şule Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Ankaravi, İsmail. 2011. Minhâcu’l-Fukarâ. Edited by Saadettin Ekici and Meral Kuzu. İstanbul: İnsan Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Atasoy, Nurhan. 2016. Derviş Çeyizi. İstanbul: IBB Kültür A.Ş. Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Ayverdi, İlhan. 2008. Misalli Büyük Türkçe Sözlük. İstanbul: Kubbealtı Publishing, vol. I–III. [Google Scholar]

- Bebek, Adil. 2009. Sûr in Türk Diyanet Vakfı İslam Ansiklopedisi. İstanbul: TDV Publications, vol. 37, pp. 533–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bıyık, Tacetdin. 2019. Osmanlı Fetvalarında Musiki. Ph.D. thesis, Süleyman Demirel Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, Isparta, Türkiye. [Google Scholar]

- Buyruk, İbrahim Ethem. 2015. Bağdatlı Rûhî Divanı’nda sosyal hayat. Ph.D. thesis, Selçuk Üniversitesi, Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, Eski Türk Edebiyatı Anabilim Dalı, Konya, Türkiye. [Google Scholar]

- Cemal, Şener. 2006. Aleviler Aleviliği Tartışıyor. İstanbul: Kalkedon Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Ceyhan, Semih. 2009. Semâ in TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Ankara: TDV Publishing, vol. 36, pp. 455–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ceylan, Murat. 2023. Postnişin Fahri Özçakıl Anlatımı ile Kültür Değerlerimizden Mevlevîlik ve Mevlevî Semâ Âyini. International Journal of Social and Humanities Sciences Research 10: 3051–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coşkun, Nilgün Çıblak. 2013. Alevi-Bektaşi Geleneğinde Dârdan İndirme Cemi ve Bu Cemin Toplum Yaşamındaki Önemi. Türk Kültürü ve Hacı Bektaş Veli Araştırma Dergisi 65: 276–77. [Google Scholar]

- Çağıl, Necdet. 2015. Kur’an Kıraatinde Musiki: Ses Uyumu, Ezgilendirme/Teganni ve Kıraatlerde Fonoloji/Ses-Anlam İlişkisi. Tarihten Günümüze Kıraat İlmi: Uluslararası Kıraat Sempozyumu 285: 327–361. [Google Scholar]

- Çelik, İsa. 2009. Türk Tasavvuf Düşüncesinde Ölüm. A.Ü. Türkiyat Araştırmaları Enstitüsü Dergisi 16: 119–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çubukçu, Hatice. 2017. Sayı sembolizminin tasavvuftaki zikir sayılarına etkisi. Türk Dünyası Araştırmaları Vakfı, Türk Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi 60: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Dal, M. Fahreddin. 2006. Fahreddin Efendi’nin Tasavvufî Görüşleri. Master’s thesis, İstanbul Marmara Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, İstanbul, Türkiye. [Google Scholar]

- Defter-i Uşşâk. n.d.Neyleyeyim Dünyâyı Bana Allâh’ım Gerek. Available online: https://defter-i-ussak.blogspot.com/2017/01/neyleyeyim-dunyay-bana-allahm-gerek.html (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Demirci, Kürşat. 1993. Cenaze in Türk Diyanet Vakfı İslam Ansiklopedisi. İstanbul: TDV Publications, vol. 7, p. 353. [Google Scholar]

- Demirci, Mustafa. 2024. Arapça Güfte ve Metinlerin Türk Din Mûsikîsindeki Yeri. Chisinau: Lambert Academic Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Dîvân Makam. n.d.Devran Bu Devran Seyran Bu Seyran—Sadeddin Rifâî Efendi (Rast). Available online: https://divanmakam.com/forum/devran-bu-devran-seyran-bu-seyran-sadettin-rifai-efendi-rast.11582/ (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Erdaş, Safiye Şeyda. 2018. Evrâd Okuma Geleneği İçerisinde Rifâî Evrâdı (İstanbul ve Rumeli Mukayeseli Örneği). Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Marmara Üniversitesi, Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, İstanbul, Türkiye. [Google Scholar]

- Erdaş, Safiye Şeyda. 2020. Üsküp Rifâî âsitânesi Şeyhi Sa’deddîn Sırrî Efendi’nin Mûsikî Yönü ve Bestelenmiş Eserleri [The Musical Aspect and Compositions of Sa’deddîn Sırrî Efendi, Sheikh of the Üsküp Rifâî Âsitâne]. Çukurova Üniversitesi İlahiyat Fakültesi Dergisi 20: 220–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdaş, Safiye Şeyda. 2023a. Evrâd Okuma Geleneği İçerisinde Rifâî Evrâdı. İstanbul: Dörtmevsim Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Erdaş, Safiye Şeyda. 2023b. Tekke Mûsikîsinde Nevbe Tertibi: Kayyâliyye Örneği [Nevbe Arrangement in Tekke Music: The Kayyâliyye Example]. İstanbul: IFAV Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Erdaş, Safiye Şeyda. 2023c. Türk Din Musikisi Formlarından Cenâze Nevbesi İcrasının İncelenmesi: Halep Örneği [Investigation of the Performance of Funeral Nevbe in Turkish Religious Music Forms: The Aleppo Example]. Rast Musicology Journal 11: 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergun, Sadeddin Nüzhet. 2017. Türk Musikisi Antolojisi, 2nd ed. Ankara: Vadi Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Eröz, Mehmet. 1992. Eski Türk Dini (Gök Tanrı İnancı) ve Alevilik-Bektaşilik. İstanbul: Türk Dünyası Araştırmaları Vakfı Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Göde, Halil, Türkan Altay, and Hüseyin Kürşat. 2015. Karaağaç Arap Nusayri Alevilerinde Ölüm İnançları ve Ritüelleri Üzerine Bir İnceleme. Türk Kültürü ve Hacı Bektaş Velî Araştırma Dergisi 73: 67–68. [Google Scholar]

- Gündüz, İrfan. 1984. Gümüşhânevî Ahmed Ziyaüddîn. İstanbul: Seha Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hünkar Hacı Bektaş Veli Foundation Council of Elders Research and Compilation Committee. 2016. Hakk’a Yürüme Erkânı. İstanbul: Serçeşme Publications. [Google Scholar]

- İnançer, Ömer Tuğrul. 2015. Antik Çağdan XXI. Yüzyıla Büyük İstanbul Tarihi. İstanbul: İBB Kültür A.Ş. Publishing, Vol. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Kara, Mustafa. 1990. Tasavvuf ve Tarikatlar Tarihi. İstanbul: Dergah Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kayserî, Davûd. 2023. Fusûsu’l-Hikem Şerhi. Translated by Tahir Uluç. İstanbul: Ketebe Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kelâbâzî. 1992. Doğuş Devrinde Tasavvuf (Ta’arruf). Edited by Süleyman Uludağ. İstanbul: Dergah Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kılıç, Mahmut Erol. 2007. Sûfî ve Şiir, 6th ed. İstanbul: İnsan Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Koç, Mustafa, ed. 2021. Revnakoğlu’nun İstanbul’u. İstanbul: Fatih Municipality. [Google Scholar]

- Kuşeyri, Abdülkerim. 1991. Risale. Translated by Süleyman Uludağ. İstanbul: Dergah Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kük, Gülçin Didem. 2021. Alevi-Bektaşi Gülbankları. Ph.D. thesis, Denizli Pamukkale Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, Denizli, Türkiye. [Google Scholar]

- Muslu, Ramazan. 2009. Türk Tasavvuf Kültüründe Sûfîlerin Ölüme Bakışı ve Cenaze Merasimleri. Ekev Academy Journal 38: 61–86. [Google Scholar]

- Mutriban. n.d.Segāh Âyin-i Şerîf. Available online: https://www.mutriban.com/mevlevi/ayin-i-serifler/segah-ayin-i-serif/ (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Neyzen. n.d.Allâh Emrin Tutalım. Zekâî Dede (Uşşâk) [PDF]. Available online: https://www.neyzen.com/nota_arsivi/01_ilahiler/096_ussak/allah_emrin_tutalim_zekai_ney.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Ocak, Ahmet Yaşar. 2014. Osmanlı Toplumunda Tasavvuf ve Sufiler. Ankara: TTK Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Olgaç, İsmet. 1995. Mûsikîmizde Zâkirbaşılık Müessesesi ve Hatib Zâkiri Hasan Efendi. Unpublished Master’s thesis, İstanbul Teknik Üniversitesi, Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, İstanbul, Türkiye. [Google Scholar]

- Özcan, Nuri. 1993. Cenâze Gülbangı in Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslam Ansiklopedisi. İstanbul: TDV Publications, vol. 7, pp. 357–58. [Google Scholar]

- Özcan, Nuri. 2009. Salâ. In TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi. İstanbul: TDV Publishing, vol. 36, pp. 15–16. [Google Scholar]

- Özcan, Nuri, and Yalçın Çetinkaya. 2020. Mûsikî. In TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Ankara: TDV Publishing, vol. 31, pp. 257–61. [Google Scholar]

- Özdamar, Mustafa. 1997. Doğumdan Ölüme Mûsiki. İstanbul: Kırk Kandil Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Özkan, İsmail Hakkı. 1996. Güfte. In TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi. İstanbul: TDV Publishing, vol. 14, pp. 217–18. [Google Scholar]

- Öztuna, Y. 1990. Büyük Türk Mûsikîsi Ansiklopedisi. İstanbul: Kültür Bakanlığı Publishing, vols. I and II, 2nd part. [Google Scholar]

- Pakalın, Zeki. 1993. Tarih Deyimleri ve Terimler Sözlüğü. İstanbul: Milli Eğitim Bakanlığı Kültür Publishing, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Revnakoğlu, Cemaleddin Server. 2003. Eski Sosyal Hayatımızda Tasavvuf ve Tarîkat Kültürü. İstanbul: Kırkambar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Say, Ahmet. 2012. Müzik Sözlüğü, 4th ed. Ankara: Müzik Ansiklopedisi Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Tahralı, Mustafa. 2008. Rifâiyye in Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi. İstanbul: TDV Publications, vol. 35, pp. 99–103. [Google Scholar]

- Tatçı, Mustafa, and Cemal Kurnaz. 2016. Türk Edebiyatında Hû Şiirleri. İstanbul: H Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Uludağ, Süleyman. 1994. Dede in Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi. İstanbul: TDV Publications, vol. 9, p. 76. [Google Scholar]

- Uysal, Saliha. 2019. Ölüme Uyanmak. İstanbul: Marmara Akademi Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Uzun, M. İ. 1993. Can in Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi. İstanbul: TDV Publications, vol. 7, pp. 138–39. [Google Scholar]

- Uzun, M. İ. 1996. Gülbank in Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi. İstanbul: TDV Publications, vol. 14, pp. 232–35. [Google Scholar]

- Uzun, M. İ. 2000. İlahi in Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi. İstanbul: TDV Publications, vol. 22, pp. 64–68. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldız, Harun. 2012. Alevi Geleneğinde Ölüm ve Ölüm Sonrası Tören ve Ritüeller. Türk Kültürü ve Hacı Bektaş Veli Araştırma Dergisi 42: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz, Hasan Kamil. 2004. Anahatlarıyla Tasavvuf ve Tarikatlar. Istanbul: Ensar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

| No | Work Title | Maqām | Uṣūl | Lyrics | Composition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Segāh Âyin-i Şerif | Segāh | Devr-i Revân | Rūmī | Buhurizade Mustafa Itrī |

| 2 | Na’t-i Mevlânâ | Rast | Non-metrical | Rūmī | Buhurizade Mustafa Itrī |

| No | Work Title | Maqām | Uṣūl | Lyrics | Composition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kalktı Havalandı Gönül Kuşu | Uşşāq | Sofyan | Pir Sultan Abdal | Anonymous |

| 2 | Cihan Var Olmadan | Uşşāq | Curcuna | Şiri Baba | Collected (Âşık Ali Metin) |

| 3 | Dostlar Beni Hatırlasın | Muhayyer | Uzun Hava | Âşık Veysel | Âşık Veysel |

| 4 | Yandım da Geldim | Uşşāq | Sofyan | Şah Hatâyî | Anonymous |

| No | Theme | Sub-Theme | Ritual Element | Religious Music | Function in Ritual Text |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ontology of Death | Hakk’a Yürümek | Death as return to ultimate truth. | Devriye, slow nafas | Transformation and continuity |

| 2 | Purification | Ghasl | Bodily–spiritual cleansing. | Nafas, düvaz, soft maqāms | Purification |

| 3 | Consent Mechanism | Social Approval | Communal consent and forgiveness | Deyiş, düvaz-imam | “Consent Square” guided by deyiş recitations. |

| 4 | Doctrine of Oneness | Tawḥīd Service | Unity of being | Hymn of Tawḥīd | Collective unison chanting |

| 5 | Secrecy (Burial) | Entrusting to the Earth | Sır/Sacred mystery | Mourning, devriye | Slow melodies during sırlama |

| 6 | Devotion to Ahl al-Bayt | 12 Imams Belief | Centrality of Ahl al-Bayt | Düvaz İmam | Core oral form of death ritual |

| 7 | Cemal-Cemalelik | Unity Order | Circular Communal posture | Unity-oriented hymns | Group chanting |

| 8 | Zakirlik | Musical guidance | Zakir as ritual & musical leader | Saz, vocal recitation | Emotional tone shaped by zakir |

| 9 | Mourning and Lament | Karbala Theme | Karbala linked mourning identity | Mourning deyiş | Karbala lens for interpreting death |

| 10 | Symbolic elements | Dar-sır-covering | Symbolic postures and objects | Silent, slow tempo | Breath control and veil of mystery |

| 11 | Submission | İkrar | Vow-based commitment to the Path | İkrar nafas | Commitment reinforced through chants |

| 12 | Journey of Soul | Eternal Journey | Pre-eternal existence | Devriye | Eternal spirit belief |

| 13 | Communal Unity | Collectivity | Tradition of collective chanting | Unison nafas | Communal exclamations (Hü/Eyvalalh) |

| 14 | Prayer forms | Gülbank | Formulaic ritual prayer | Melodic gülbank | Marks transitions between services |

| 15 | Cultural Continuity | Oral tradition | Transmission of ritual knowledge | Traditional repertoire | Continuity via nafas |

| No | Work Title | Maqām | Uṣūl | Lyrics | Composition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ömür Bahçesinin Gülü Solmadan | Rast | Sofyan | Yunus Emre | Küçük Ahmet Ağa |

| 2 | Uyan Behel Gâfil | Rast | Düyek | Aziz Derviş Yunus | Hayrullah Taceddin Efendi |

| 3 | Ey Dervişler Ey Kardeşler | Hüseyni | Sofyan | Yunus Emre | Anonymous |

| 4 | Taştı Rahmet Deryası | Acem | Düyek | Aşık Yunus | Hafız Hüseyin Efendi |

| 5 | Aşkınla Çâk Olsa Bu Ten | Uşşāq | Düyek | Seyyid Nizamoğlu | Hacı Nafiz Bey |

| 6 | Allāh Emrin Tutalım | Uşşāq | Sofyan | Yunus Emre | Zekâi Dede |

| 7 | Târik-I Hak’ta Burhânım | Evc | Düyek | Kabûlî | Anonymous |

| 8 | Hayıf Bunca Geçen Ömrüme | Hüseynî | Sofyan | Yusuf Emre | Anonymous |

| 9 | Segāh Tekbir | Segāh | Non-metrical | Arabic Text | Buhurizâde Mustafa Itrī |

| 10 | Mevlâm Gözüm Yaşı Akar Sel Olur | Bayātî | Sofyan | Seyyid Seyfullah | Anonymous |

| 11 | Yanmaktan Usanmazam Mevlam | Hüseynî | Yürük Semâî | Yunus Emre | Anonymous |

| No | Theme | Sub-Theme | Codes | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Musical Structure and Function | Role of Zakirbaşı | Musical leadership; pitch setting, repertoire control, coordinating zakirs | The zakirbaşı ensures musical integrity and ritual cohesion |

| Musical Forms | Ilahi, Salā, Awrād-ı Sharif, Tevhid, Ism-i Celâl, Ism-i Hû, Gülbank | Funeral ceremonies rely on a multi-layered musical structure. | ||

| Maqam Preferences | Hüseyni, Uşşaki Beyati, Neva, Mâye | Maqam choice changes according to emotional phases | ||

| Musical Quality and Training | Ear training; pitch unison; formal training; aesthetic discipline | Performer competency is crucial to maintaining musical quality | ||

| 2 | Ritual Stages– the Position of Music | Ghasl | Yanmaktan Usanmazam/Hayıf benim… | Works expressing sorrow and seperation |

| After Ghasl | Awrād-ı Sharif, raising pitch, collective chanting | Strong vocal projection | ||

| Funeral Procession | Salā, high-pitched hymns | Unity-oriented hymns | ||

| Musalla | Tawḥīd, Ism-i Celâl, Ism-i Hû, prayer, gülbank | The ritual’s spiritual climax with intensified dhikr | ||

| After Burial | Returning with Tawḥīd | The ritual’s soothing and concluding phase | ||

| 3 | Repertoire Sources– Historical Origins | Oral Tradition | Usta, çırak, hafızlar, Sefer Dal, Fahreddin Efendi | Tradition is largely sustained through oral transmission |

| Notated Sources | Suphi Ezgi, Cüneyt Kosal archives | Written sources support modern performances. | ||

| Order-specific Compositions | Works of Ahmet Özhan, Metin Alknalı; local melodic motifs | Unique compositions maintain the vitality of the repertoire. | ||

| 4 | Religious Sufi Meaning and Spiritual Function of Music | Concept of Wuslat | Shab-e Arus Spiritual guidance “Lovers do not die” | Death-Union; Music-Meaning |

| Aesthetic–Spiritual Depth | Tears, serenity, sorrow, contemplation | Music guides emotion and enhances spiritual depth. | ||

| Bid’at-i Hasene | Worship aesthetics; beautification of devotional acts | Music intensifies devotional consciousness | ||

| 5 | Influence of Community and Tarīqa Structure | Crowd Dynamics | Large procession, collective performance | Religious music organizes and regulates group movement |

| Change of Murshid | 40-day mourning; istikhāra; unity | Communal identity continues through ritual after the murshid’s passing | ||

| 6 | Musical Aesthetics, Emotion Regulation and Psychology | Managing Grief | Voice choking; emotional intensity | Performers embody and transmit collective grief |

| Aesthetic Coherence | Maqām harmony; rhythmic flow | Musical coherence strengthens the ritual’s aesthetic presence |

| No | Work Title | Maqām | Tempo | Lyrics | Composition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Şehitlerin Ser Çeşmesi | Uşşāq | Devr-i Hindi | Yunus Emre | (Compilation) Raif Vırmiça |

| 2 | Devran Bu Devran | Rast | Sofyan | Şeyh Sırrî Efendi | Şeyh Sadettin Rifai |

| 3 | Kudret Kandili | Hüseynî Nafas | Serbest | Sadettin Sırrî Efendi | Anonymous |

| 4 | Ömrün Şu Biten Neşvesi | Uşşāq | Yürük Semâî | Yahya Kemal Beyatlı | Süleyman Erguner (Neyzen) |

| 5 | Akbele’l-bedru aleynâ (Şugul) | Ḥicāz | Sofyan | Anonymous | Anonymous |

| 6 | Rifâî Leyyâ (Şugul) | Ḥicāz | Sofyan | Anonymous | Anonymous |

| 7 | Allāhümme Salli Alâ Muhammed (Şugul) | Ḥicāz | Sofyan | Anonymous | Anonymous |

| 8 | Efdalu’l-Âlemîn (Şugul) | Ḥicāz | Sofyan | Anonymous | Anonymous |

| 9 | Ente Nüshatü’l-Ekvân (Şugul) | Segāh | Sofyan | Anonymous | Anonymous |

| 10 | Mâ Medde Li Hayri’l-Halki Yedâ (Şugul) | Hüzzam | Sofyan | Anonymous | Anonymous |

| 11 | Yâ Erhame’r-Rahimin (Şugul) | Çargâh | Sofyan | Anonymous | Anonymous |

| 12 | Aleyke Sallallâh (Şugul) | Ḥicāz | Sofyan | Anonymous | Anonymous |

| 13 | Salâtullâh Selâmullâh Aleyke Yâ Rasûlallâh (Şugul) | Ḥicāz | Sofyan | Anonymous | Anonymous |

| No | Theme | Subtheme | Elements of Religious Music | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Spiritual Ranks in the Rifāʿī Order | Āshiq—Murīd Muhibb—Muttaqī Darwish—Naqīb Shaykh—Khalīfa | Hierarchy, maturity, dhikr level, ritual responsibility | As spiritual rank increases, musical participation, and ritual responsibility increase. |

| Şerbet ceremony, ikrar, darwish training | Adab-erkān, training, introduction to musical method | Music becomes a tool of spiritual formation as rank rises. | ||

| 2. | Funeral Ritual Music | Washing ritual | Dhikr, asmāʾ al-husnā, awrād | Music enters the funeral ritual from the beginning. |

| Procession to the grave | Asmāʾ, Hū dhikr, Lā ilāha illā Allāh | Collective rhythmic vocalization is central. | ||

| 3. | Funeral Ritual Music | Selection of hymns | Hymns chosen by shaykh or based on deceased’s preference | Selection is based on personal and spiritual harmony. |

| Rank-based variation | Different rites for Khalīfa, Shaykh, Darwish, Muhibb, Āshiq | Musical intensity corresponds to spiritual rank. | ||

| 4. | Post-Funeral Practices | Black flag (şed) | Symbol of mourning | Represents spiritual mourning within the tekke. |

| İnstrument prohibition | No instruments used | Music becomes minimal until the new shaykh takes the post. | ||

| Regular ceremonies | 7th, 40th day, 6th month, 1st year | Religious music continues in post-funeral cycles. | ||

| 5. | Dhikr & Awrād Structure | Awrād-ı Sharīf Rifāʿī | Dhikr leadership, rhythmic patterns | Performed in modes Ḥicāz, Segāh, Hüzzam with rhythmic structures. |

| Asmāʾ dhikrs | Monophonic, rhythmic repetition | Ensures collective unity. | ||

| Repetition of Hū | Breath technique, emphasis | Regulates group breathing and rhythim. | ||

| 6. | Ritual Space | Semahane/Tekke courtyard Home | Acoustic, spatial suitability Limited musical volume | Preferred for Shaykh and Khalīfa funerals. |

| washing | Music becomes minimal in private settings. | |||

| 7. | Procedural Difference | Shared Adab-Erkan | Common values | Modes, dhikr, hymns share smiliar structuras. |

| Order-spesific method | Rifāʿī intense rhythms | Rifāʿī dhikr identified with powerful collective sound | ||

| 8. | Functional Dimension | Spiritual consolation | Emotion regulation | Music transforms grief into contemplation. |

| Communal unity | Synchronization, collective breath | Dhikr creates collective unity | ||

| Spiritual transition | Accompanying the soul’s journey | Music supports the spiritual passage of the deceased |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

DEMİRCİ, M. Turkish Religious Music in the Funeral Ceremonies of Sufi Orders. Religions 2025, 16, 1578. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16121578

DEMİRCİ M. Turkish Religious Music in the Funeral Ceremonies of Sufi Orders. Religions. 2025; 16(12):1578. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16121578

Chicago/Turabian StyleDEMİRCİ, Mustafa. 2025. "Turkish Religious Music in the Funeral Ceremonies of Sufi Orders" Religions 16, no. 12: 1578. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16121578

APA StyleDEMİRCİ, M. (2025). Turkish Religious Music in the Funeral Ceremonies of Sufi Orders. Religions, 16(12), 1578. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16121578