The following discussion draws together the theoretical and empirical strands of the study. It first addresses the problem of how modern interpreters can describe ancient genres without imposing anachronistic categories, distinguishing between emic and etic perspectives. It then considers how Mark’s genre emerges through processes of continuation and adaptation rather than invention. Finally, the discussion turns to the question of purpose and function—the point at which the comparative and computational evidence converge—showing that, while Mark may occasionally echo neighbouring literary idioms, his Gospel coheres most clearly within the scriptural mode of the LXX single-person narratives, where genre, theology, and communal identity form a unified horizon.

4.1. Genre Between Worlds: Negotiating Emic and Etic Horizons of Mark

One of the most pressing questions that arises from our analyses is how we, as modern interpreters, can speak meaningfully about genre in relation to texts that did not themselves operate with the same categories. Can we describe ancient texts by means of the categories their own authors and audiences might have recognised, or do we risk slipping into modern terminology that would have been wholly foreign to them? Ancient writers could and did speak about their works in emic terms—drawing on notions of poetry and prose, style,

imitatio,

exampla, or genre-marking conventions—yet they could not have framed their narratives within the conceptual grids of modern literary theory. The challenge for us is to acknowledge this distinction: to remain attentive to the categories that made sense within antiquity, while also recognising that the etic language we bring to the table is interpretive and therefore always at risk of obscuring as much as it reveals.

22 This problem is not limited to theoretical reflection; it has practical implications for how we read texts like Mark’s Gospel, whose literary identity resists modern genre grids.

Piotr Michalowski, in his important essay on commemoration, writing, and genre in Mesopotamia, has drawn attention to the dangers of this etic imposition (

Michalowski 1999). He demonstrates how modern observers can easily misread Mesopotamian textual culture when they approach its texts through modern conceptual categories rather than the distinctions that made sense within that world. What appears to us as “literary,” “historical,” or “religious” may, from an emic perspective, have belonged to entirely different spheres of meaning, so that without attention to the culture’s own taxonomies and logic, we risk misunderstanding both the form and the function of its writings.

A similar point is pressed by Thomas M. Bolin in his discussion of historiography and the Hebrew Bible (

Bolin 1999). This issue is all the more pressing for our purposes, since the narrative conventions of the Hebrew Bible share many of the same rhetorical and theological dynamics that later reappear in the Gospels. Yet while the Hebrew Bible itself belongs to a Semitic literary milieu, these traditions entered the Greek-speaking world through the Septuagint, where they were rearticulated within the forms and stylistic conventions of Hellenistic prose. Mark thus stands at the intersection of these currents: his work participates in the Greek literary culture of the Roman world while continuing the narrative and theological impulses of Israel’s scriptures. Understanding how genre operates in the Hebrew Bible—where narrative, theology, and communal memory are inseparable—therefore provides a crucial analogue for approaching Mark’s own literary practice. Failing to take this emic perspective seriously entails more than a minor anachronism; it risks a fundamental distortion of what ancient texts sought to do and say. The same danger faces the interpretation of Mark: if we analyse his Gospel solely through modern categories or strictly classical frameworks, we risk mistaking its communicative logic and misconstruing its literary voice.

Bolin argues, first, that it is inappropriate simply to label Hebrew Bible narratives as “historiography” in the Greco-Roman or modern sense. Such a label imposes an etic framework that privileges modern assumptions about documentation and evidence, obscuring the ways these texts represented the past through remembrance, not reconstruction. From an emic perspective, their concern with memory, identity, and divine action differs fundamentally from the explanatory and empirical aims of Greek or modern historiography. The same caution applies to Mark. When the Gospel is compared computationally with classical historiography, its linguistic and structural profile shows little affinity to that corpus, suggesting that it participates in a different narrative tradition and serves different communicative purposes.

Second, Bolin insists that some of the texts from the Hebrew Bible nevertheless do engage with the past and construct meaningful relations to it, a feature likewise visible in Mark’s continuous negotiation of collective memory and fulfilment, where the past of Israel is reactivated within a narrative that is both retrospective and anticipatory. Yet this engagement with the past does not in itself determine genre. Mark, like the Hebrew Bible narratives it echoes, uses memory and history theologically rather than historiographically. If those earlier texts are not best understood within the Greek or modern genre of historiography—as Bolin has argued—it becomes equally unlikely that Mark should be read as a work of historiography in the Greco-Roman sense, since his linguistic and structural profile aligns closely with the prototypical examples of the scriptural, LXX-based narratives identified in our computational analyses. What both Bolin’s analysis and our results underscore is that engagement with the past can be central to a text’s purpose without defining its genre.

Third, Bolin points out that earlier generations of scholars often described the texts from the Hebrew Bible as “history-writing” in a way that amounted to cultural appropriation: an attempt, framed within a Christian cultural horizon, to cast ancient Israel as unique and proto-modern. Just as biblical texts were once reframed through Christian lenses that rendered ancient Israel proto-modern, Mark has often been read as proto-Christian—interpreted through theological categories that belong to later doctrinal horizons rather than to the scriptural and cultural world in which the Gospel itself was composed. Our results likewise caution against this anachronism: they indicate that Mark is best understood within the continuum of Israel’s scriptural tradition, as a text that reimagines the past through theological conviction and communal memory, rather than through interpretive frameworks that arose in later ecclesial or doctrinal settings.

Finally, Bolin suggests that a more suitable term for these biblical engagements with the past might be “antiquarian writing,” a label that avoids the ideological freight carried by “historiography” while acknowledging the texts’ interest in memory and origins. Seen in this light, Mark’s Gospel—though written in Greek and part of the broader literary culture of the early Roman world—shares this antiquarian impulse in the story of Jesus: it gathers, reframes, and reinterprets inherited traditions to orient its community’s understanding of divine action in time. In this sense, Mark’s treatment of the past is continuous with that of Israel’s scriptures: it is not the work of a historian but of a theologian who writes through narrative. His engagement with memory and origins serves not to record events but to interpret them, transforming Israel’s remembered history into a medium of revelation and renewal. Thus, Bolin’s discussion is a timely reminder that our generic categories are not innocent; they are interpretive acts that can illuminate but also distort—and our computational results confirm that such illumination is best achieved when we allow the data themselves to show where a text like Mark most naturally belongs. Recognising this emic horizon does not preclude modern analysis; on the contrary, it clarifies what our methods can measure. In this way, computational modelling becomes an empirical means of negotiating the emic–etic divide, enabling modern analysis to recover something of the ancient logic by which genre, purpose, and function cohered.

4.2. From Taxonomy to Continuation: Modelling Genre and Purpose in Mark

In light of these considerations, our approach moves beyond static taxonomies, resisting the tendency to treat genre as a rigid classificatory grid whose sole function is to assign texts to predefined categories. Following Todorov’s insight that genres evolve through repetition and transformation and Fowler’s emphasis on overlapping family resemblances rather than fixed essences, we take genre to be a dynamic and meaning-generating phenomenon—something that mediates between style, form, structure, content, purpose, and social setting. In line with Bakhtin’s view of genre as a socially embedded and dialogic practice, texts are not neutral containers of meaning but rhetorical interventions embedded in specific contexts, responding to prior utterances and anticipating future ones. At the same time, the indeterminacy Derrida observed—the constant tension between belonging and transgression—reminds us that genre boundaries are always porous and provisional. They shape, and are shaped by, the expectations of their audiences—expectations concerning form, register, length, style, truth claims, and function. Genre, in this sense, comes both first and last: it frames the initial orientation of the reader or hearer, but it is reconstituted in the very act of interpretation.

This recognition also explains why our reconstructions must remain hypothetical. The historical distance is too great, and our access to the intentions of the author, the social conditions of production, and the expectations of the first audiences is too fragmentary for us ever to recover genre with certainty. Yet the text itself offers strong clues—linguistic, structural, intertextual, and thematic—that allow us to model plausible contours. The reader we envisage as historically most plausible is one situated in the cultural world of first-century Judaea and Galilee: a world marked by familiarity with Israel’s scriptures but also by political transformations such as the Hasmonean civil war, Pompey’s conquest of Judaea in 63 BCE, the reign of the Herodian dynasty, the tetrarchic division of the kingdom, the re-establishment of Roman Judaea in 6 CE, and the brief territorial reunification under Agrippa I, whose apparent restoration of Jewish rule soon dissolved into renewed provincial fragmentation and the mounting tensions that culminated in the war of 66–70 CE. A reader within this environment would have been best placed to discern the generic signals encoded in the Gospel and to engage with its purpose as both continuation and transformation of prior discursive forms.

Ancient literary cultures, moreover, habitually developed genres through such continuations. In Greek historiography, Herodotus, Thucydides, Xenophon, and Theopompus stand in a sequence of response and redefinition, each reshaping the narrative strategies of their predecessors. As Christopher Pelling memorably observes, the “continuing dynamic” resembles that of spouses finishing one another’s sentences—sometimes tactfully, sometimes in explicit correction but always in the context of a continuing exchange about how history should be written (

Pelling 1999, p. 327). The same pattern holds in tragedy, where Sophocles reworked Aeschylean forms, and Euripides in turn reinterpreted Sophocles. It can also be observed in the epic tradition with Homer as its quintessential prototype, and in the Greek novel, scholars widely regard Chariton’s

Chaereas and Callirhoë as the generative prototype, which later writers such as Xenophon of Ephesus, Longus, and Achilles Tatius expanded and reshaped. A similar dynamic may well be at work in the Gospel of Mark, which engages inherited narrative patterns not by simple imitation but through creative reconfiguration—precisely the kind of process our analyses have shown to characterise Mark’s relationship to its literary prototypes. In doing so, the evangelist both recalls and renews the conventions of earlier traditions, suggesting that its genre, too, emerged through dialogue rather than invention

ex nihilo.

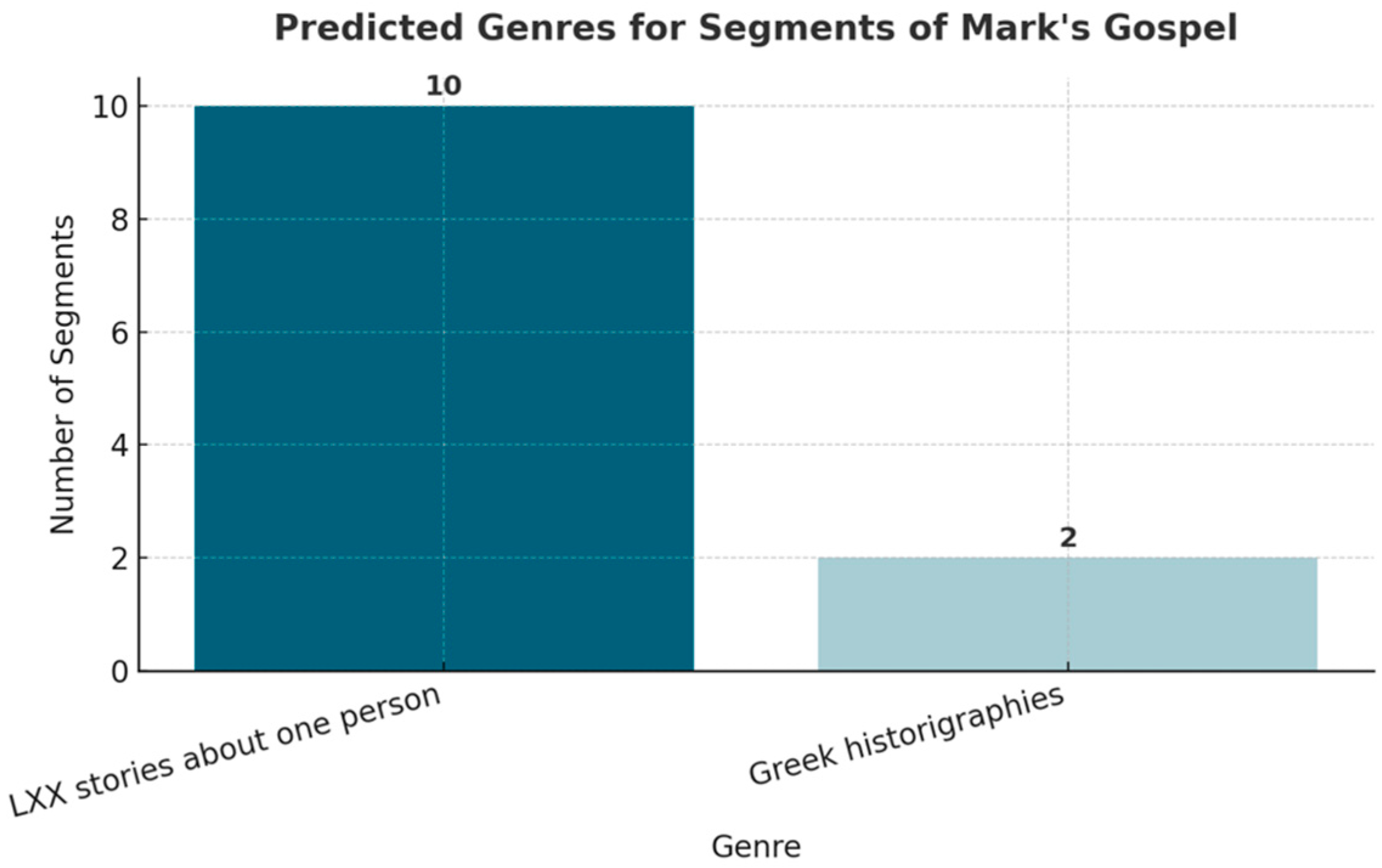

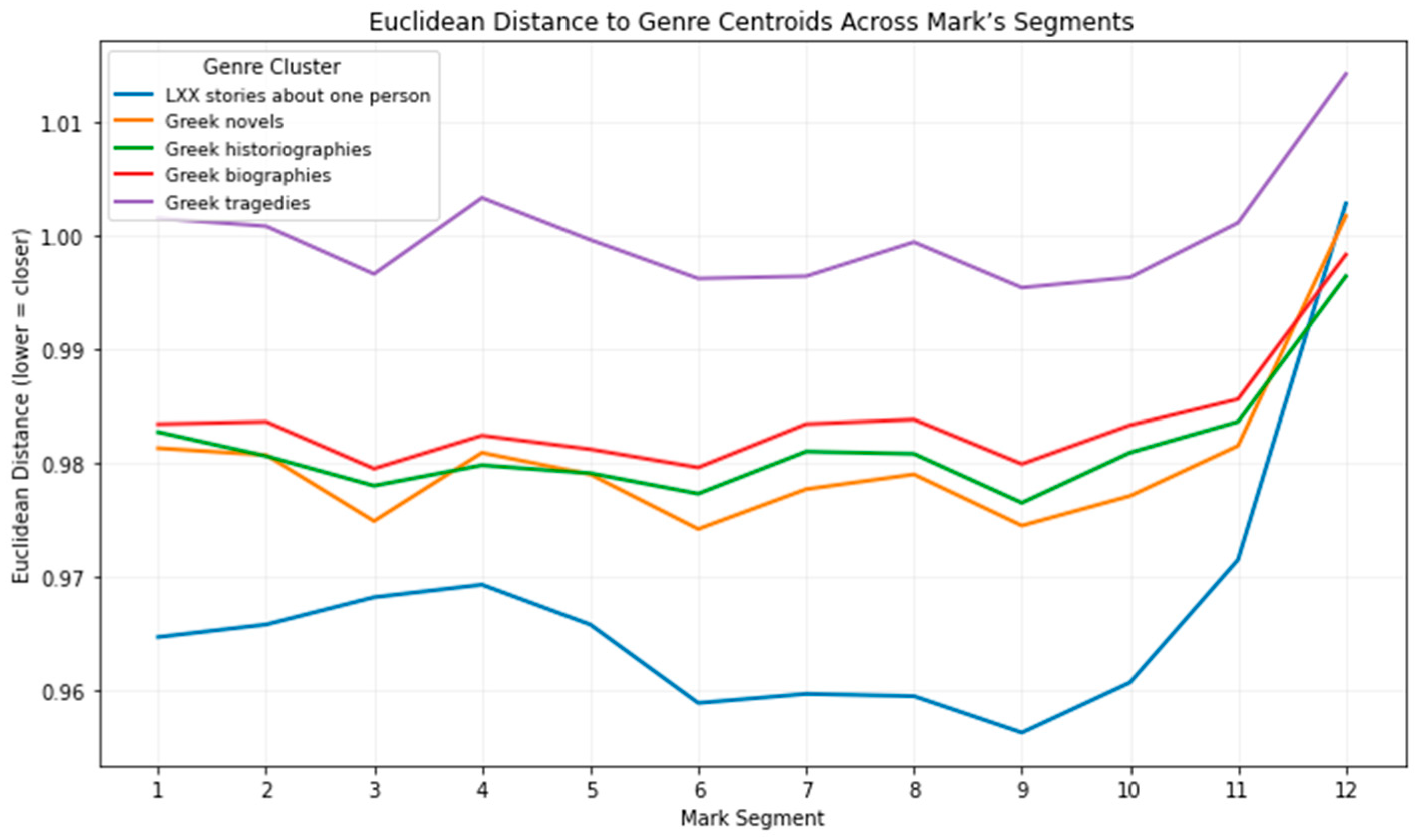

The question for the Gospel of Mark is therefore not simply whether it should be filed under biography, tragedy, historiography, or novel, but which prototypes it most closely gravitates toward within the literary field of its time. Our analyses indicate that, while Mark shares certain surface features with Greco-Roman biography, its dominant signals place it nearer to the LXX single-person stories: extended narratives of a divinely appointed figure whose mission is inseparable from the destiny of God’s people and shaped by the theological and narrative logic characteristic of its Semitic predecessors. In this respect, Mark does not so much resist classification as align itself with a recognisable prototype—one rooted in the Greek-language world of the LXX yet carrying the theological and communal weight of Israel’s scriptures that the LXX itself transmitted. To read Mark in this way is to move beyond static taxonomies and to consider how its generic identity emerges from proximity and resonance rather than from rigid boundaries. And it is precisely here that the pivotal question of purpose and function comes into sharper focus: if Mark situates itself most clearly within the company of the LXX stories, then its communicative aims are best understood in light of that tradition—identity formation, divine commissioning, and the reimagining of Israel’s destiny—rather than in terms borrowed from the moralising or commemorative functions of Greco-Roman biography. In what follows, this issue will be explored through a closer examination of how Mark’s narrative resonates with, yet remains distinct from, the major literary forms of his cultural world—reflecting occasional echoes of Greco-Roman genres while adhering most closely to the narrative logic and style of the LXX scriptural tradition.

4.3. Mark and the Function of Ancient Genres

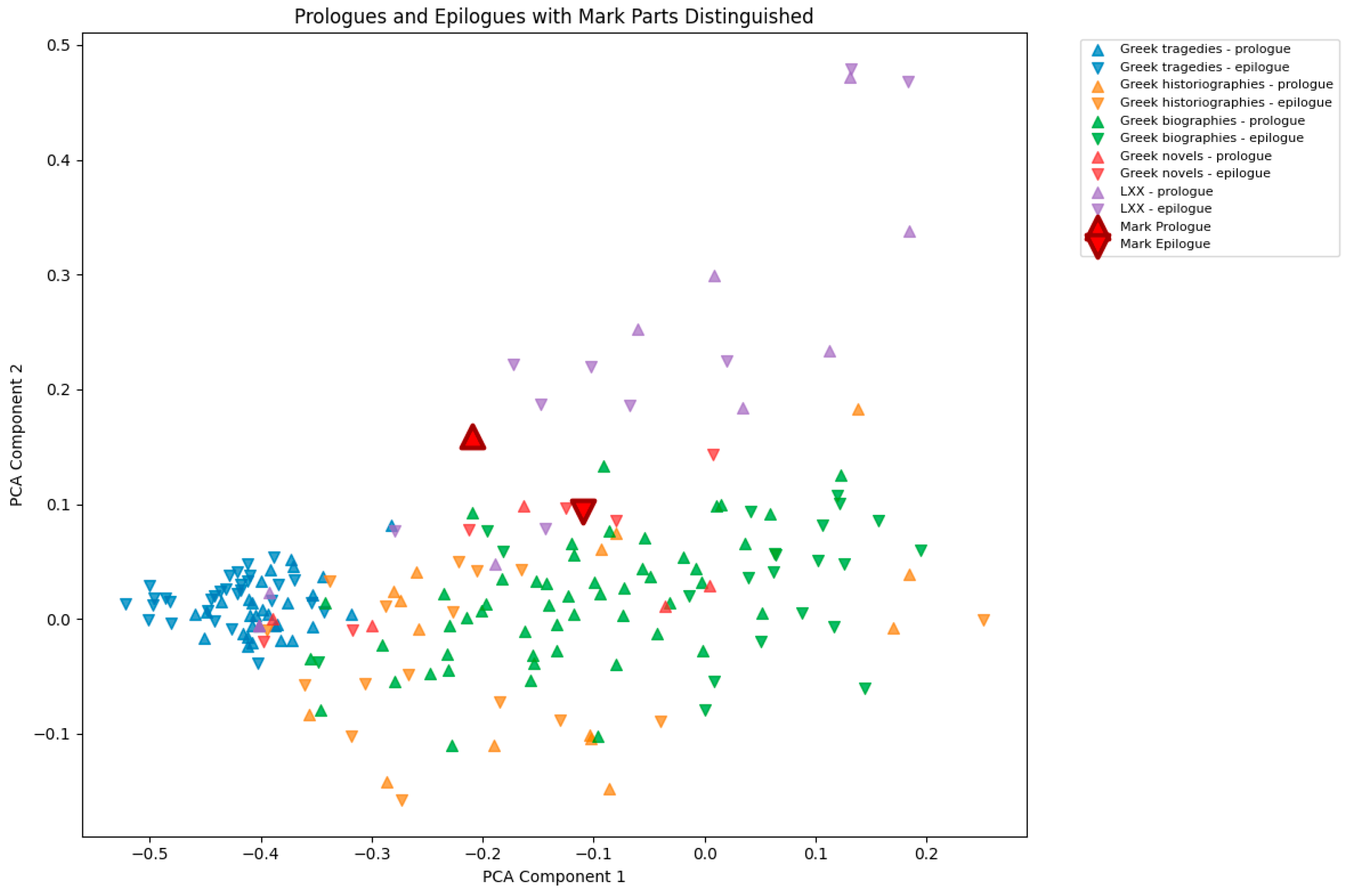

4.3.1. Tragedy

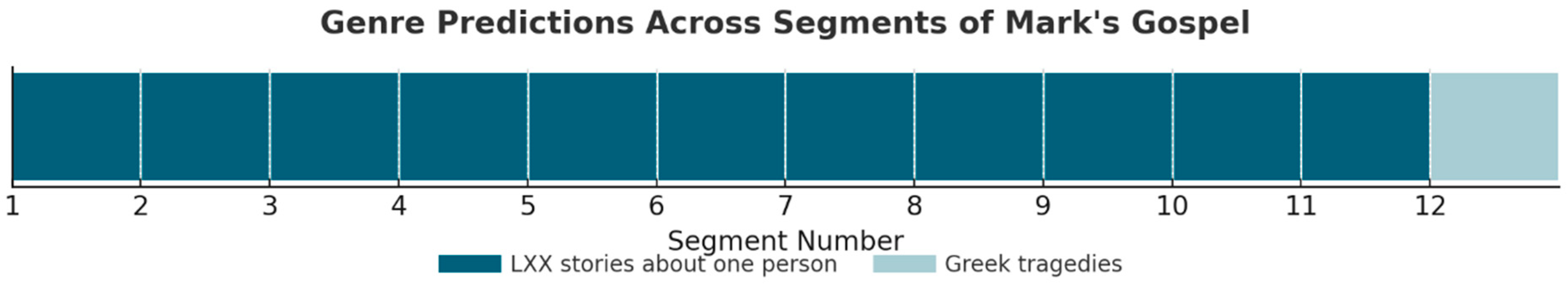

When Mark’s Gospel is compared with the corpus of ancient Greek tragedy, the results are at once illuminating and limiting. At first glance, the parallels are striking. Like Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides—and, in a Jewish adaptation of the form, Ezekiel the Tragedian—Mark presents a central protagonist whose story moves toward a climactic act that defines the fate of God’s people. Our computational analyses confirm that this proximity is not imaginary: segments of the Passion Narrative drift toward the tragic cluster, registering stylistic and lexical echoes of the tragic mode.

Yet the most decisive difference is located precisely at the point where tragedy reaches its telos. In the tragic tradition, the plot reaches its irreversible resolution through the destruction or downfall of the hero—most often in death but at times through exile, disgrace, or another form of irrevocable loss. The audience’s foreknowledge of this ending heightens the dramatic tension, while the actual death brings about the cathartic release of pity and fear. In Mark, by contrast, the death of Jesus is not a resolution but a turning point. The resurrection reframes the entire narrative, situating the Passion within an eschatological horizon that transforms finality into continuation and closure into anticipation. This divergence explains why, even with local resonances, Mark consistently resists classification as tragedy in our clustering: the global profile does not align with the tragic prototype.

The tragedies themselves also differ at the level of form and reception. They are marked by stylised and often metrical language, a performative setting before a civic audience, a dramatised engagement with canonical myths, and a carefully staged alternation of prologue, episodes, and choral odes. Their thematic preoccupations—fate, divine justice, and the limits of human agency—are embedded in a mode of reception that presupposes a civic ritual context. Mark, by contrast, draws on prose narrative, is transmitted as written discourse, and reorients motifs of suffering and betrayal away from catharsis and toward proclamation of divine action in a Jewish cultural tradition.

Placed within J. Z. Smith’s comparative framework—x is like y in respect to z—Mark (x) resembles tragedy (y) insofar as both structure the protagonist’s suffering and death (z) as the dramatic climax of the narrative. But it differs radically in the resolution: where tragedy ends in death, Mark redefines death through resurrection. In this respect, the Gospel parallels the tragic mode in its portrayal of suffering, yet reorients that pattern toward theological revelation rather than dramatic finality.

From a methodological perspective, this comparison demonstrates both the value and the limits of computational evidence. The models highlight partial and domain-specific similarities, forcing us to specify exactly where the text aligns and where it diverges. At the same time, they remind us that socio-historical and performative contexts—civic theatre on the one hand, early Messianic proclamation on the other—cannot be reduced to lexical signals alone. In the end, the distance revealed by the models confirms the interpretive conclusion: Mark can adopt tragic colouring in the Passion, but it ultimately reorients that register toward a radically different horizon, where the end is not catharsis through death but hope through resurrection.

From the perspective of purpose and function, the tragic register in Mark is best understood not as a generic framework but as a parallel mode of expression that momentarily resonates with the tragic tradition while serving a different end. The Gospel does not aim at catharsis or moral reflection, as tragedy does, but at revelation: the unveiling of divine purpose through suffering. The tragic tone of the Passion Narrative thus serves a theological, not a theatrical, function.

23 It heightens the sense of human vulnerability only to expose its transformation by divine agency. In this respect, the affinities between Mark and tragedy reflect a shared concern with suffering and resolution rather than direct dependence or imitation. The motifs of betrayal, death, and lament therefore find analogous expression in both forms, but their resolution in Mark follows the logic of the LXX stories, where divine intervention overturns despair and restores purpose. The tragic mode, in other words, is not adopted but paralleled—its emotional pattern briefly echoed within a larger narrative design shaped by scriptural theology and communal memory.

4.3.2. Historiography

When Mark is compared computationally to the corpus of ancient Greek historiography—represented here, e.g., by Thucydides and Herodotus—the differences quickly outweigh the similarities. Classical historiography is marked by an explicit concern for critical enquiry, chronological precision, and empirical investigation; it integrates ethnographic observations with political and military analysis, aiming to provide a coherent explanatory account of past events. By contrast, Mark exhibits little interest in these aims or methods. His Gospel neither presents a sustained chronological framework nor pursues the kind of critical evaluation of sources that defines Greek historiographic practice. While certain elements—occasional ethnographic detail or reference to political powers—are present, these are incidental rather than constitutive of the narrative’s purpose. This explains why, in our computational clustering, Mark consistently maintains a substantial distance from the Greek historiographic corpus. This initial comparison, however, also highlights what is at stake: the concept of historiography itself and whether its etic use can meaningfully describe ancient narrative forms that engage the past in other, non-empirical ways.

The comparison gains nuance when we reconsider what is meant by “historiography,” drawing on Bolin’s observation above that the term itself can conceal a different kind of narrative logic—one more akin to the identity-creating storytelling found in the scriptures of Israel. As Bolin has shown, such narratives engage deeply with the past, yet they do so within a conceptual world very different from that of Greco-Roman or modern historiography. Their purpose is not to document events empirically but to interpret them theologically, shaping communal memory and collective identity through narrative. The Hebrew Bible thus offers stories that recount the emergence, consolidation, and territorial definition of Israel as a people, often within a loose chronological frame but embedded in a wholly different literary ecology. It contains no “pure” historiographic books, nor identifiable “authors” in the Greek or modern sense. The Pentateuch, for example, is an amalgam of narrative, poetry, law, cultic instruction, and mythic reflection—woven together for theological persuasion and communal formation rather than factual reconstruction. From Bolin’s perspective, such writing is better described as “antiquarian” than historiographical: it seeks to remember origins and interpret divine purpose rather than to explain the past by empirical or causal analysis. In this light, to label these works as “historiography” without qualification is to commit the same etic error Bolin warns against—imposing modern taxonomies on ancient texts and thereby obscuring their emic logic. The same caution applies to Mark. Although the Gospel engages with the past and situates its narrative within Israel’s history, it does so not as a historian compiling evidence but as a theologian constructing meaning. Its form and function align more closely with the scriptural mode of memory and revelation than with the analytical discourse of Greek historiography.

Seen against this background, the comparison can now be refined through J. Z. Smith’s principle of analogy—x is like y in respect to z: our x is Mark, our y the corpus of Greek historiographic texts, and our z the use of the past to shape collective identity. In this respect, Mark shows certain affinities with historiography: his narrative incorporates ancestral memory, prophetic fulfilment, and territorial motifs to define a community’s place in time. Yet these features function differently from their counterparts in Greek historiography. Rather than documenting events or establishing causal explanations, Mark’s treatment of the past operates through recollection and interpretation—it is theological and communal rather than empirical and analytical. What our computational comparisons make visible is precisely this distinction: Mark shows certain structural parallels to the outward form of history-telling, yet the purpose of his narrative operates in a different register. The Gospel’s engagement with origins and destiny is not historiographic in the classical sense but closer to what might be called antiquarian or identity-creating writing—a narrative mode that remembers the past to construct meaning for the present. Rather than adopting historiographic form, Mark’s narrative simply converges with it at the level of outward pattern, while its underlying logic points in another direction: a rearticulation of history as revelation, grounded in a distinct literary and theological horizon.

From the perspective of purpose and function, Mark’s relationship to the historiographic mode is best understood in terms of surface resemblance rather than conscious adaptation. The Gospel displays familiar references to the past, to rulers and regions, and to public events, which create a surface of historical depth; yet their function is not to document the past but to interpret it. What may initially appear as a historiographic gesture thus parallels, rather than imitates, the explanatory stance of classical history-writing, while serving a distinct theological purpose: the past is not recorded but understood through divine action within time. In this sense, these historiographic echoes in Mark point to a theological aim—they define communal identity through memory, not through chronology or empiricism.

24 Mark therefore belongs not within historiographic discourse but within the scriptural practice of remembering the past as the sphere of divine disclosure—a mode of writing where history is not recorded but interpreted, and where memory itself becomes revelation.

4.3.3. Biography

When the Gospel of Mark is compared computationally to ancient biographical literature—especially Greco-Roman bioi—certain surface similarities emerge. Both Mark and the bioi are centred on a named protagonist whose words and deeds dominate the narrative. Ancient biography typically seeks to present the life of its subject in a way that reveals his character and the values he embodies, often integrating formative episodes, exemplary actions, and moral instruction. Yet here the parallels between Mark and biography become strained. Mark shows little interest in Jesus’ life as a private individual, his upbringing, or the cultivation of personal virtues in the manner of Plutarch or Xenophon. Instead, the Gospel focuses on the public activity of Jesus—his works of healing, teaching, and exorcism—not as expressions of a moral philosophy but as acts that disclose the nature of God, manifest divine authority, and fulfil the eschatological promises embedded in the scriptures of Israel.

The thematic centre of Mark’s narrative is thus not the personality of Jesus as a moral exemplar but his identity and mission as the decisive agent in God’s redemptive plan. From a computational perspective, these differences are borne out in measurable ways. Lexical and structural features that dominate bioi—extended character portraits, moralising commentary, and balanced coverage of different life stages—are largely absent in Mark. The Gospel instead exhibits patterns more characteristic of proclamation, eschatological urgency, and scriptural argumentation. This explains why, in our clustering, Mark occasionally approaches the biographical corpus at a superficial level, yet diverges sharply in its deeper narrative logic. This is underscored by the Gospel’s dense network of scriptural allusions, which portray Jesus as the one who fulfils, reinscribes, and reinterprets the prophetic hopes of Israel. In this respect, the “life” presented in Mark is not a biographical life in the Greek sense but a theologically framed mission narrative. Yet because the narrative remains organised around a single, named protagonist whose actions reveal his importance, it inevitably invites comparison with ancient forms of “life writing.” Understanding what this resemblance does—and does not—entail requires a more precise framework for comparison.

Applying J. Z. Smith’s comparative model—x is like y in respect to z—our x is Mark, our y the corpus of ancient bioi, and our z the structuring of a narrative around a central figure’s actions as the expression of his significance. In this respect, Mark resembles ancient bioi insofar as he organises the story around a single protagonist whose actions disclose his importance. Yet the resemblance is only formal. The Gospel does not, like the bioi described by Burridge and others, construct a moral portrait or offer the reader an exemplar of virtue. Instead, it defines significance in theological rather than ethical terms: the protagonist’s deeds reveal divine authority, not human excellence; his death is the moment of fulfilment, not of tragic closure; and his resurrection transforms the narrative into proclamation rather than commemoration. What creates the superficial impression of biographical form is therefore not dependence on bios conventions but the shared narrative impulse—found also in Israel’s scriptures—to tell the story of a single, divinely chosen figure, whose life determines the fate of the community. Mark stands within this broader ancient tradition of single-protagonist storytelling, yet within a scriptural and eschatological horizon rather than a moral–philosophical one. The familiar shape of “a life” finds a loose parallel in his narrative, but its organising logic differs fundamentally: not the cultivation of character but the revelation of divine purpose through mission and fulfilment. The Gospel therefore parallels the outward form of a biography while operating within a distinct theological framework, where the focus lies on identity, vocation, and hope rather than moral exemplarity.

From the perspective of purpose and function, the resemblances between Mark and ancient biography point not to dependence but to distinction: they reflect shared narrative conventions yet ultimately serve divergent aims. Both centre their narratives on a single, consequential life, yet in Mark, this life is not primarily the object of moral contemplation but the vehicle of divine revelation. What looks, at first sight, like the pattern of a bios—a sequence of deeds leading toward a climactic end—belongs to a literary world in which the portrayal of a life served an ethical and philosophical end. In the Greco-Roman tradition, the bios offered a paradeigma, a moral exemplum virtutis to be contemplated and imitated. The telling of a life was not a neutral record but an act of moral pedagogy, shaping the reader’s disposition through the spectacle of virtue embodied in action. Such narratives sought to impress a typos or charaktēr upon their audience—a moral imprint through which the ideal of the good life could be discerned and internalised. Nowhere is this more evident than in the works of Plutarch, whose Parallel Lives epitomise the biographical ideal: by pairing Greek and Roman figures, he turned the genre into a mirror of moral reflection and cultural mediation, constructing virtue as a shared measure between moral and political traditions. Seen against this background, the distinctive purpose of Mark’s narrative becomes clear. Its coherence arises not from the cultivation of character but from the unfolding of vocation; its protagonist acts not only as a moral paradigm but also as the agent through whom divine purpose is disclosed. Yet Mark’s narrative does not abolish the ethical altogether: it reframes it. The call to follow, serve, and share in the path of its central figure remains, but this ethic is grounded in revelation and covenant rather than in moral self-formation. What seems on the surface to trace the contours of a life instead reveals the shape of a mission—the movement of divine purpose within history. In this sense, Mark reorients what might appear biographical into a theology of vocation and fulfilment, where imitation is transformed by revelation, and moral example becomes participation in God’s redemptive design.

4.3.4. Novel

When the Gospel of Mark is compared computationally to the corpus of ancient Greek novels—Chariton, Xenophon of Ephesus, Achilles Tatius, Longus, Heliodorus, and the anonymous Life of Aesop—the results show only limited alignment. The Greek novels are, at their core, literary works designed to entertain: they are marked by erotic intrigue, improbable adventures, shipwrecks, recognitions, and reversals; they operate within a world of aesthetic polish and elite cultural amusement. Their narrative structures sustain suspense and delight, offering the reader a sequence of imaginative and often fantastic episodes in which virtue and love are tested, threatened, and ultimately vindicated. Mark, by contrast, exhibits little interest in entertainment in this sense. His Gospel neither cultivates the ornamental style nor the leisurely pace of the Greek novel; its urgency, abrupt transitions, and focus on the fulfilment of divine purpose stand in sharp contrast to the novels’ cultivated artifice. If Mark may be called “elitist,” it is not because it participates in the Greco-Roman tradition of refined literary amusement but because it presupposes a different form of paideia altogether. In the Hellenistic world, paideia denoted education as a marker of status—an aesthetic and rhetorical accomplishment that distinguished the socially privileged from the untrained many. In Mark, by contrast, intellectual and spiritual distinction lies in mastery of a different economy of knowledge: literacy in the scriptures, fluency in inherited traditions, and the capacity to discern divine meaning in their reinterpretation. His Gospel assumes a readership capable of reading symbolically rather than ornamentally, attuned to parables, prophecy, and fulfilment. The “elite” implied here is not a Greco-Roman cultural class but an interpretive community—those formed by scriptural paideia, grounded in what later rabbinic idiom would call the “tradition of the elders.” This paideia operated through its own hermeneutical logics, often opaque to (ethnic) outsiders: the use of repetition and synonymous balance (parallellismus membrorum) that could appear pleonastic to Hellenistic taste; the weaving of citation and commentary into a single discursive fabric; and the conviction that wisdom was transmitted through preservation rather than invention. Within this horizon, true education is marked not by rhetorical polish but by knowledge of God’s acts in history. What defines the learned is not cultural refinement but interpretive wisdom—the ability to discern meaning within the scriptural tradition.

Applying J. Z. Smith’s comparative model—x is like y in respect to z—helps to clarify both the reach and the limits of this comparison. Our x is Mark; our y is the corpus of Greek novels; and our z is the use of a continuous narrative centred on the testing and vindication of virtue and love through peril and reversal. In this respect, Mark shares with the novels a narrative concern for conflict and resolution, but the resemblance is only formal. The Greek novels employ such patterns for entertainment and emotional engagement, whereas in Mark the sequence of peril and restoration serves a theological purpose: it dramatises divine agency rather than human fortune. What in the Greek novel offers delight in improbable adventure becomes, in Mark, a proclamation of divine action unfolding within history. If the Greek novels use adventure to delight and entertain, the Jewish counterparts deploy similar narrative energies toward markedly different ends—identity formation, communal reassurance, and the interpretation of divine purpose in history.

This contrast with the Greek novels also highlights the need to reconsider how modern scholarship has framed the relationship between Hellenistic and Jewish narrative traditions. The comparison acquires further nuance when we turn to what Lawrence Wills and others have called “Jewish novels”—a label applied, somewhat anachronistically, to certain Second Temple and post-biblical narratives that share structural features with the Greek novel yet differ radically in function and purpose (e.g., Joseph, Daniel, Jonah, Esther, Judith, Joseph and Aseneth, etc.) (

Wills 1995,

1997,

2011,

2021). These texts, like the Greek novels, are often adventure-driven and plot-centred, but their aims are markedly different. They are not designed for leisure reading or aesthetic pleasure; instead, their narrative form is harnessed for theological and communal ends—identity formation, reassurance amid crisis, and the reinforcement of covenantal values. Their protagonists are not lovers or wanderers but agents through whom divine justice, covenant fidelity, and providential reversal are revealed. The label “Jewish novel,” however, is itself problematic: it is a modern, etic construct that imposes Greek and modern generic nomenclature on Semitic literary traditions with distinct emic logics—different conceptions of coherence, authority, and purpose. Some of the most sophisticated examples—such as the Joseph or Moses narratives—are embedded within larger literary wholes like Genesis or the Pentateuch and therefore lack the discrete, “closed” form of the Greek novels, whose structures were designed for reading pleasure and resolution. This difference in literary ecology raises an important methodological question: what, precisely, is being compared when Mark is placed alongside them?

Applying J. Z. Smith’s comparative model—x is like y in respect to z—as a heuristic rather than an empirical exercise helps to illustrate the stakes of such comparison. Our x is Mark; our y the so-called “Jewish novels”; and our z the use of adventure-driven storytelling to negotiate divine purpose, identity, and communal destiny. Mark shares with these narratives an emphasis on peril and deliverance, divine oversight amid crisis, and the testing of faith through trial. The similarity lies less in literary type than in a shared theological grammar—a narrative logic in which suspense and reversal become means of articulating how God acts on behalf of his people. What modern scholarship terms the “Jewish novel” thus approximates the narrative world of Mark but only as an etic construct—revealing in its analogies, yet limited in scope. It gestures toward, without fully capturing, the recurrent patterns of theological storytelling that, for analytical purposes, we describe as the LXX single-person narratives.

If we accept the category of Jewish novel, its thematic core diverges sharply from that of the Greek novel. Such works tend to emphasise adherence to the Law, loyalty to covenant and kinship, the theological centrality of the land—its conquest, inheritance, protection, and restoration—and the motif of the divinely chosen or specially gifted individual whose vocation serves the fulfilment of God’s plan. These emphases align closely with much of Mark’s thematic repertoire, but to acknowledge this already brings us to the threshold of a different generic horizon: the LXX single-person narratives, where such patterns are more consistently codified, and the comparison becomes genuinely illuminating. Recognising these convergences thus requires a shift in analytical focus: from the modern construct of the “Jewish novel” to the scriptural narratives whose theological grammar—here described analytically as the LXX single-person narratives—offers the most coherent framework for situating Mark’s storytelling within its broader Second Temple horizon.

4.3.5. LXX Person-Oriented Stories

Among the various literary groupings considered so far, none captures the distinctive texture of Mark’s Gospel as fully as what may be termed the LXX single-person narratives. This category marks the point of culmination in our investigation: it brings into focus a corpus of scriptural stories whose formal design, thematic preoccupations, and theological outlook most closely mirror those of the Gospel. Unlike tragedy, historiography, biography, or the Greek novel, these narratives speak from within the same ethnic, conceptual and religious world as Mark and therefore offer the most coherent frame of comparison. The term itself is not ancient but analytic—a construct developed for the purposes of this study to describe a cluster of texts in the Septuagint and related traditions, diverse in setting yet unified by their focus on a single, divinely commissioned protagonist. Its foundation is heuristic rather than theoretical, assembled inductively from recurrent features in the texts rather than from any inherited taxonomy. Yet because it is drawn directly from the scriptural corpus itself, the category approaches an emic level of description: it names what ancient readers would have recognised intuitively, even if they lacked a formal term for it. In this sense, the LXX single-person narratives are best understood not as an artificial construct imposed upon the data but as a retrospective gathering of patterns already latent within the biblical tradition—a grouping that clarifies, rather than distorts, the literary and theological matrix from which Mark’s Gospel emerged.

Stylistically, these narratives take the form of extended prose accounts centred on a single protagonist whose life unfolds in a continuous sequence of divine commission, conflict, and resolution. Thematically, they revolve around a figure chosen and empowered by God—often distinguished by fidelity to the Law and exemplary piety—through whom the covenant people are preserved or delivered. Most crucially, they differ from the genres considered earlier in their social setting, function, and purpose. Where Greek tragedy offered spectacle to the theatre-going elite, historiography sought to instruct civic leaders through examples of political prudence, biography modelled virtue for the morally ambitious, and the novel entertained readers formed by the leisure of empire, these scriptural narratives belong to a different world. They speak to communities living under foreign domination, sustained not by cultural prestige but by faith in divine intervention. Their purpose is not aesthetic pleasure or moral refinement but survival, remembrance, and hope—the theological maintenance of identity through the retelling of God’s acts in history. In this, they are not merely stories about deliverance; they are acts of deliverance, narrative spaces where a threatened people rehearses its conviction that God will again raise a deliverer on their behalf. In this, they are not opposed to the Hellenistic world from which they emerged but participate in it on their own terms—adapting its narrative conventions to articulate a scriptural understanding of history, agency, and hope.

Applying J. Z. Smith’s formula—x is like y in respect to z—our x is Mark, our y the corpus of LXX single-person narratives, and our z the convergence of narrative form, theological content, and socio-historical function within contexts of oppression and divine intervention. In this comparison, both Mark and these scriptural stories organise their plots around the actions of a divinely commissioned protagonist whose faithfulness under trial secures the deliverance of God’s people. Each is animated by the conviction that divine power is revealed not in stability or prestige but in crisis, reversal, and restoration. The resemblance lies in the shared conviction that history itself is the arena of God’s redemptive agency and that narrative is the medium through which that agency is discerned. Mark’s Gospel thus participates directly in this scriptural mode of storytelling: it employs the same narrative grammar to interpret divine action in history and to express renewed hope for God’s intervention on behalf of Israel.

The socio-historical horizon assumed by these narratives is one of longing for restoration—the gathering of God’s people, the return to the land, the re-establishment of temple worship and priestly service, and renewed observance of the Law, often accompanied by the expectation that surrounding nations will be judged and overthrown. Read within this framework, Mark’s Gospel shares not only their formal and thematic contours but also their ideological horizon. Like the Exodus, the conquest traditions in Joshua, the rise of kingship in Samuel and Kings, and the prophetic responses to exile, Mark’s story turns on the conviction that God will again act decisively to liberate and restore his people. In this sense, the LXX single-person narratives provide the most compelling analytic framework for understanding Mark’s literary identity: they reveal how his Gospel translates the language of deliverance and restoration into a narrative of divine action within history.

From the perspective of purpose and function, the LXX single-person narratives illuminate not only the literary matrix of Mark’s Gospel but also its self-understanding. The patterns observed in these scriptural stories—divine commissioning, testing through suffering, vindication, and the restoration of God’s people—are not merely parallel to Mark’s narrative design; they appear to constitute the very logic through which the evangelist conceives his work. If Mark is read within this scriptural continuum, his Gospel emerges not as an innovation that departs from Israel’s literary traditions but as their renewal under eschatological pressure: the same God who acted through Joseph, Moses, Elijah, or Esther now acts again through the anointed one. It is therefore plausible to imagine that Mark himself, or at least his earliest readers, would have recognised his account as belonging to this same lineage of sacred storytelling—a continuation of Israel’s narrative history rather than the creation of a new genre.

Were we to describe Mark’s work in ancient rather than modern terms, we might speak of it as a graphē of divine deliverance or, in the idiom of the LXX itself, a logion peri tou Theou ergou—a narrative of God’s decisive act through a chosen servant. In contemporary terms, one might simply call it a scriptural narrative of divine agency: a text that reconfigures Israel’s literary past in order to proclaim God’s intervention in the present. However we name it, this analytic grouping—rooted in the scriptural tradition itself—provides the clearest vantage point from which to grasp both the literary coherence and the theological intention of Mark’s Gospel: it situates the evangelist precisely where he belongs—within the living continuum of Israel’s scriptures.