Artistic Integration and Localized Adaptation: An Analysis of Roof Ridge Decorations in the Sinicization Process of the Yungang Grottoes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Context and Methodological Framework

2.1. Previous Scholarship and Related Issues

2.2. Methodological Framework

3. Classification of Roof Ridge Decorations in Yungang Grottoes

4. Symbolic Meaning of Roof Ridge Decorations in Yungang Grottoes

4.1. Symbolic Meaning of the Chiwei

有石闕、祠堂、石室三間,椽架高丈余,鏤石作椽,瓦室施鴟尾造。(郦道元《水經注》)

There are stone que, ancestral shrine, and stone room. The ceiling height exceeds ten feet, featuring stonework for the rafters. The tile room is designed in the chiwei style.

吳在辰,其位龍也,故小城南門上反羽為兩鯢鱙,以象龍角。越在巳地,其位蛇也,故南大門上有木蛇,北向首內,示越屬於吳也。(趙曄《吳越春秋·闔閭內傳》)

For the Wu Kingdom, located in the Chen 辰 position, with high status resembling that of a dragon, had the two feathers reflected on the top of the south gate of a small town transformed into two images of the Ni and Zha (dragon-like creatures), symbolizing the dragon’s horns. As for the Yue Kingdom, located in the Si position, its position was akin to that of a snake. Thus, a wooden snake was placed on the south gate, facing north towards the city, to indicate that the Yue Kingdom belonged to the Wu Kingdom.

越俗有火災,復起屋必以大,用勝服之。(司馬遷《史記·封禪書》)

After a fire in the Yue region, the rebuilt buildings are consistently enlarged and equipped with talismans to overcome fire.

蚩尾能避火災,置之殿堂,用勝服之。(蘇鶚《蘇氏演義》)

Chiwei can prevent the fire by strategically placing it in the Hall and using the talisman to overcome it.

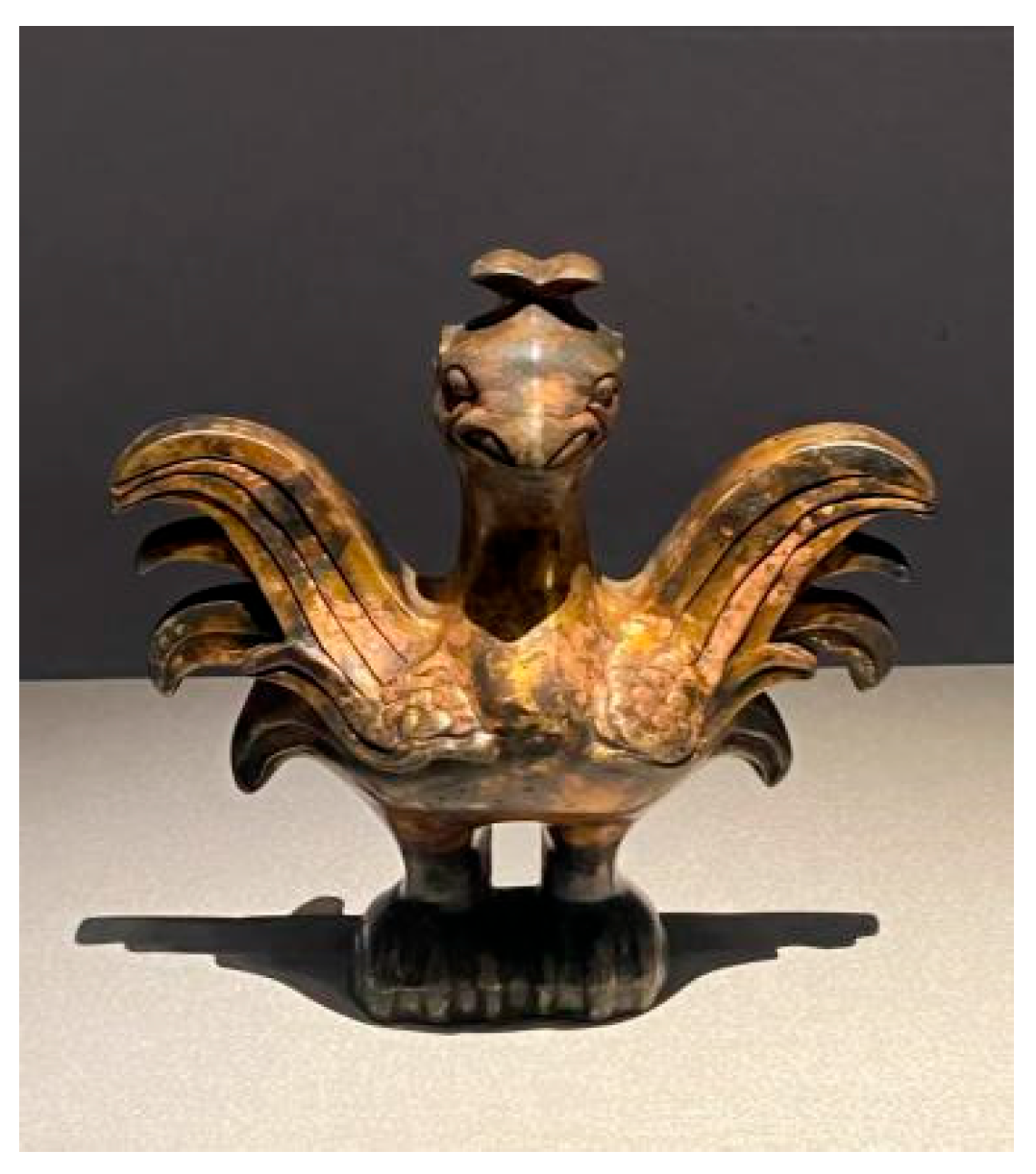

4.2. Symbolic Meaning of the Phoenix

(陳直《三輔黃圖校正》)

The perimeter of Jianzhang Palace measures 30 li. Biefeng Que, located in the east, stands at a height of 25 zhang and provides a panoramic view from its elevated location. In addition, located to the north of the palace gates is a cylindrical structure, similarly measuring 25 zhang in height, adorned with a copper phoenix positioned on its apex. it was destroyed by the Red Eyebrows Army.

築雙鳳之崇闕,表大路以遐通。上規圜以穹隆,下矩折而繩直。長楹森以駢停,修桷揭以舒翼。(费振剛《全漢賦校註》)

The Chongque of Twin Phoenixes was erected, and a primary thoroughfare was developed to ease transit. The upper section of the building exhibits a round and grandiose design, but the lower section possesses a square and robust structure. The columns of the structure are lofty and erect, meticulously arranged akin to avian wings unfurling. The structural elements of the building, such as the beams and rafters, possess a high density and robustness, akin to the expansive wingspan of birds.(Fei 2004)

朱鳥舒翼以峙衡,騰蛇蟉虬而繞榱。(费振剛《全漢賦校註》)

The red bird extends its wings and perches on the horizontal beam, projecting an aura of solemnity and stability. The brackets and pillars are adorned with serpent and crab designs that intertwine.(Fei 2004)

簫韶11九成,鳳凰來儀。

When the Xiao and Shao music reaches its ninth perfection, the phoenix arrives in all its glory.

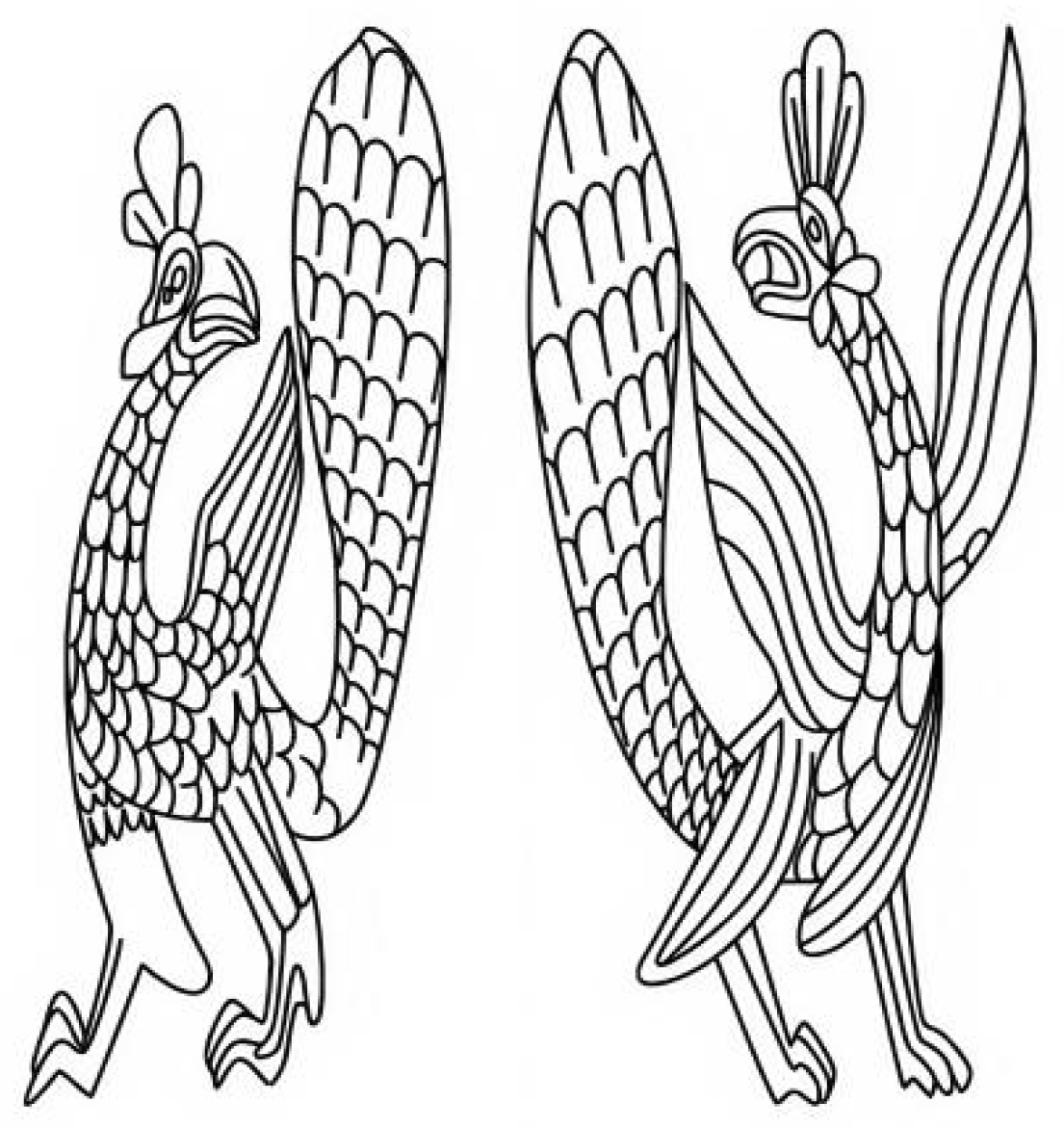

4.3. Symbolic Meaning of the Garuda

4.4. Symbolic Meaning of the Flame Element

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | One of the most important titles for the Buddha is the Sanskrit word Tathāgata, often translated as “the Thus Come One” in English and as 如來 in Chinese. |

| 2 | Wuxing 五行 theory posits that five elements (wood, fire, earth, metal, water) interact through productive and destructive cycles. In the destructive cycle, water overcomes fire, which explains the water-related symbolism of chiwei as fire prevention. |

| 3 | Ancient characters (gu zi 古字) refer to the earlier orthographic forms used to represent specific lexical items in classical Chinese texts before being replaced by later character variants in subsequent historical periods. |

| 4 | 北冥有魚,其名為鯤。鯤之大,不知其幾千里也。化而為鳥,其名為鵬。鵬之背,不知其幾千里也。怒而飛,其翼若垂天之雲。 Watson translates: In the Northern Darkness there is a fish and his name is K’un. The K’un is so huge I do not know how many thousand li, he measures. He changes and becomes a bird whose name is P’eng. The back of the P’eng measures I do not know how many thousand li, across and, when he rises up and flies off, his wings are like clouds all over the sky. (Watson 1968) |

| 5 | Cishi 刺史: The Cishi system of the Han Dynasty was a balanced power structure created by ancient Chinese statesmen to regulate the relationship between central authority and local governance, ensuring long-term national unity and peace. |

| 6 | Wudian Roof 廡殿頂, also known as a hip roof, this is the highest-ranking and most prestigious roof type in traditional Chinese architecture. Characterized by five ridges and four fully sloped sides, its use was strictly reserved for imperial palaces and the most important state temples, symbolizing supreme authority. |

| 7 | Jianzhang Palace 建章宮, constructed by Emperor Wu of the Western Han Dynasty, was located southwest of Chang’an. It served as the imperial palace during the reigns of Emperor Wu and Emperor Zhaodi of the Han Dynasty. Unfortunately, it was destroyed by the Red Eyebrows Army赤眉軍 towards the end of the Western Han Dynasty. |

| 8 | Li 里, commonly referred to as the Chinese mile, is a conventional measurement of distance in China. The length of the li currently has been standardized to a length of half a kilometer. |

| 9 | Zhang 丈 is a traditional unit of length in China. In 1930, this was modified to a precise measurement of 3⅓ m. |

| 10 | Yuan He 元和: Yuan He was the second reign title of Emperor Zhang of Eastern Han Dynasty, Liu Da 劉炟. |

| 11 | Xiao Shao 簫韶: There are two categories of ancient Chinese music. The term “Xiao” designates the musical style associated with Emperor Shun, whereas “Shao” designates the musical style associated with Emperor Yao. Both individuals are regarded as paragons of virtuous governance in Chinese history. |

| 12 | 《春秋演孔圖》 Chunqiu Yan Kong Tu:「鳳,火精。」 |

| 13 | 《春秋元命苞》 Chunqiu Yuan Ming Bao: 「火離為鳳。」; Fire火: one of the Wuxing 五行, specifically the element of fire; Li離: one of the eight trigrams 八卦, associated with fire. |

References

- Buswell, Robert E., and Donald S. Lopez. 2014. The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Caswell, James O. 1988. The Written and Unwritten: A New History of the Buddhist Caves at Yungang. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Qing 常青. 2021. Zhongguo Shiku Jianshi 中國石窟簡史 [A Brief History of Chinese Grottoes]. Hangzhou: Zhejiang Guji Chubanshe 浙江古籍出版社 [Zhejiang Ancient Books Publishing House]. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Zhi 陳直. 1980. Sanfu Huangtu Jiaozheng 三輔黃圖校正 [Correction of the Sanfu Huangtu]. Shaanxi: Shaanxi renmin chubanshe陝西人民出版社 [Shaanxi People’s Publishing House]. [Google Scholar]

- Dunhuang Yanjiuyuan 敦煌研究院 Dunhuang Academy. 2016. Dunhuang shiku yishu quanji 9 Baoen jinghua juan 敦煌石窟藝術全集 9 報恩經畫卷 [Complete Collection of Dunhuang Cave Art 9: Illustrated Scrolls of the Sutra of Requiting Kindness]. Shanghai: Tongji daxue chubanshe 同濟大學出版社 [Tongji University Press]. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, Zhenggang 費振剛. 2004. Quanhanfu Jiaozhu 全漢賦校註 [Annotated Complete Collection of Han Dynasty Fu]. Guangdong: Guangdong Jiaoyu Chubanshe 廣東教育出版社 [Guangdong Education Publishing House]. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Xinian 傅熹年. 2004. Zhongguo Gudai Jianzhu Shi Lun 中國古代建築十論 [Ten Essays on Ancient Chinese Architecture]. Shanghai: Fudan Daxue Chubanshe 复旦大学出版社 [Fudan University Press]. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Yang 高陽. 2009. Zhongguo Chuantong Jianzhu Zhuangshi中國傳統建築裝飾 [Traditional Chinese Architectural Decoration], 1st ed. Tianjin: Baihua Wenyi Chubanshe 百花文艺出版社 [Baihua Literature and Art Publishing House]. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Qingfan 郭慶藩. 2012. Zhuangzi Jishi 莊子集釋 [Collected Commentaries on the Zhuangzi], 3rd ed. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju 中華書局 [Zhonghua Book Company]. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Bing 韓冰. 2015. Handai Jianzhushang de Wuji Zhuangshi 漢代建築上的屋脊裝飾 [Roof Ridge Decoration on Han Dynasty Architecture]. Henan: Zhongyuan wenwu 中原文物 [Cultural Relics of Central China]. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Houxuan 胡厚宣. 1934. Chu Minzu Yuanyu Dongfang Kao 楚民族源於東方考 [Investigation on the Eastern Origin of the Chu People]. Beijing: Beijing Daxue Chubanshe 北京大學出版社 [Peking University Press]. [Google Scholar]

- Jizang 吉藏, Huiyuan 慧遠, and Zhiyi 智顗. 1990. Wuliangshoujing Yishu 無量壽經義疏 [Commentary on the Larger Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra]. Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe 上海古籍出版社 [Shanghai Classics Publishing House]. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Yonghai 賴永海, and Yueqing Wang 王月清. 2017. Zhongguo Fojiao Yishushi 中國佛教藝術史 [History of Chinese Buddhist Art]. Nanjing: Nanjing Daxue Chubanshe 南京大學出版社 Nanjing University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Daoyuan 酈道元. 2007. Shuijing Zhu Jiaozheng 水經注校證 [Proofreading of the Commentary on the Water Classic]. Proofread by Chen Qiaoyi 陳橋驛. Beijing: Zhonghua SHUJU 中華書局 [Zhonghua Book Company]. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Jingjie 李靜傑. 2022. Jinchiniao Tuxiang Fenxi 金翅鳥圖像分析 [Analysis of Garuda Images]. Gansu: Dunhuang Yanjiu 敦煌研究Dunhuang Academy. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yuqun 李裕群, and Lidu Yi. 2015. Shanxi Gaoping Dafoshan Moya Zaoxiang Kao——“Yungang Moshi” Nanchuan de Zhongyao Lizheng 山西高平大佛山摩崖造像考—“云冈模式”南传的重要例证 [On the Dafoshan Cliff-side Sculptures in Gaoping, Shanxi—An Important Evidence of the Southward Diffusion of the “Yungang Mode”]. Beijing: Wenwu 文物 [Cultural Relics]. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Sicheng 梁思成. 1947. Yungang Shiku Zhong Biaoxian de Beiwei Jianzhu 雲岡石窟中所表現的北魏建築 [The Northern Wei Architecture as Expressed in the Yungang Grottoes]. Beijing: Zhongguo Yingzao Xueshe Huikan 中國營造學社彙刊 [Bulletin of the Society for Research in Chinese Architecture]. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Xujie 劉敘傑. 2003. Zhongguo Gudai Jianzhushi, 1st ed. 中國古代建築史 (第1卷) [The History of Ancient Chinese Architecture, 1st ed.]. Beijing: Zhongguo jianzhu gongye chubanshe 中國建築工業出版社 [China Architecture & Building Press]. [Google Scholar]

- McNair, Amy. 2007. Donors of Longmen: Faith, Politics, and Patronage in Medieval Chinese Buddhist Sculpture. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, Yingtao 祁英濤. 1978. Zhongguo Gudai Jianzhu de Jishi 中國古代建築的脊飾 [Ridge Decoration of Ancient Chinese architecture]. Beijing: Wenwu 文物 [Cultural relics]. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Hong 任葒. 2014. Zhongguo Fenghuang Tuxiang Yanjiu中國鳳凰圖像研究 [Images of Chinese Phoenix]. Beijing: Zhongguo Yishu Yanjiuyuan 中國藝術研究院 [Chinese National Academy of Arts]. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Zhifang 任誌芳. 2023. Yungang Shiku Zhong Jinchiniao Xingxiang de Hanhua Chutan 雲岡石窟中金翅鳥形象的漢化初探 [Preliminary Study on the Sinicization of the Golden-Winged Bird Image in the Yungang Grottoes]. Shanxi: Shanxi Datong Daxue Xuebao (Shehui Kexue Ban) 山西大同大學學報(社會科學版) [Journal of Shanxi Datong University (Social Science Edition)]. [Google Scholar]

- Sharf, Robert H. 2002. Coming to Terms with Chinese Buddhism: A Reading of the Treasure Store Treatise. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sickman, Laurence, and Alexander Soper Coburn. 1968. The Art and Architecture of China, 3rd ed. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Sima, Qian 司馬遷. 1959. Shi Ji 史記 [Records of the Grand Historian]. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju 中華書局 [Zhonghua Book Company], p. 1402. [Google Scholar]

- Sofukawa, Hiroshi 曾布川宽. 2009. A Study of Chinese Buddhist Grottoes: Yungang, Longmen, and Xiangtangshan 中国仏教石窟の研究:雲岡・龍門・響堂山. Tokyo: Chūō Kōron Bijutsu Shuppan. [Google Scholar]

- Soper, Alexander Coburn. 1959. Literary Evidence for Early Buddhist Art in China. Ascona: Artibus Asiae Press. [Google Scholar]

- Soper, Alexander Coburn. 1966. Imperial Cave-Chapels of the Northern Dynasties: Donors, Beneficiaries, Dates. Artibus Asiae 28: 241–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Bai 宿白. 1978. Yungang Shiku Fenqi Shilun 雲岡石窟分期試論 [A Tentative Chronology of the Yungang Grottoes]. Beijing: Kaogu Xuebao [Acta Archaeologica Sinica]. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Bai 宿白. 1991. Pingcheng shili de jiju he “Yungang moshi” de xingcheng yu fazhan 平城實力的集聚和”雲岡模式”的行程與發展 [The Concentration of Power in Pingcheng and the Formation and Development of the ‘Yungang Model’]. In Zhongguo Shiku: Yungang Shiku (1) 中國石窟:雲岡石窟(一) [Chinese Grottoes: Yungang Grottoes (Vol. 1)]. Edited by Yungang Shiku Wenwu Baoguan Suo 雲岡石窟文物保管所. Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe 文物出版社 [Cultural Relics Publishing House], pp. 174–97. [Google Scholar]

- Su, E 苏鹗. 1985. Sushi Yanyi 蘇氏演義 [Romance of the Su Family]. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju 中華書局 [Zhonghua Book Company]. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, Burton. 1968. The Complete Works of Chuang Tzu. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Jingwei 溫敬偉. 2012. Cong Jishi de Zaoqi Xingtai Kan Chiwei de Qiyuan從脊飾的早期形態看鸱尾的起源 [Tracing the Origins of chiwei Through an Analysis of Early Ridge Ornament Forms]. Guangdong: Guangzhou Wenbo 廣州文博 [Guangzhou Cultural Relics]. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Dorothy C. 2004. Chinese Steles: Pre-Buddhist and Buddhist Use of a Symbolic Form. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Xinjiang Shiku Yanjiusuo 新疆石窟研究所 [Xinjiang Research Institute of Grottoes]. 2017. Xiyu Bihua Quanji 1 西域壁畫全集1 [Complete Collection of Western Regions Murals 1]. Xinjiang: Xinjiang Wenhua Chubanshe 新疆文化出版社 [Xinjiang Cultural Publishing House]. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Yiying 徐毅英. 1995. Xuzhou Handai Huaxiangshi 徐州漢代畫像石 [Xuzhou Han Dynasty Stone Reliefs]. Beijing: Zhongguo shijieyu chubanshe 中國世界語出版社 [China Esperanto-eldonejo]. [Google Scholar]

- Yagi, Haruo 八木春生. 2000. Unkō sekkutsu mon’yō ron 雲岡石窟文様論 [A Study of Yungang Ornamentation]. Kyoto: Hōzōkan 法藏館 [Hōzōkan Publishing]. [Google Scholar]

- Yagi, Haruo 八木春生. 2004. Chūgoku Bukkyō bijutsu to kan minzokuka: Hokugi jidai kōki o chūshin to shite 中国仏教美術と漢民族化―北魏時代後期を中心として [Sinicization of Chinese Buddhist Art: Focusing on the Late Northern Wei Period]. Kyoto: Hōzōkan 法藏館 [Hōzōkan Publishing]. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Lidu. 2018. Yungang: Art, History, Archaeology, Liturgy. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Chao 張焯. 2011. Zhongguo Shiku Yishu (Yungang) 中國石窟藝術(雲岡) [Grottoes Art in China: Yungang]. Jiangsu: Jiangsu Meishu Chubanshe 江蘇美術出版社 [Jiangsu Fine Arts Press]. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Chao 张焯, Heng Wang 王恒, and Kunyu Zhao 赵昆雨, eds. 2017a. Yungang Shiku Quanji, Di Ba Juan: Di Shiyi, Shi’er Ku 云冈石窟全集·第八卷:第十一、十二窟 [The Complete Works of Yungang Grottoes, Vol. 8: Caves 11 & 12]. Qingdao: Qingdao Chubanshe 青岛出版社 [Qingdao Publishing House]. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Chao 张焯, Heng Wang 王恒, and Kunyu Zhao 赵昆雨, eds. 2017b. Yungang Shiku Quanji, Di Qi Juan: Di Jiu, Shi Ku 云冈石窟全集·第七卷:第九、十窟 [The Complete Works of Yungang Grottoes, Vol. 7: Caves 9 & 10]. Qingdao: Qingdao Chubanshe 青岛出版社 [Qingdao Publishing House]. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Chao 张焯, Heng Wang 王恒, and Kunyu Zhao 赵昆雨, eds. 2017c. Yungang Shiku Quanji, Di Shiyi Juan: Di Shisan Ku 云冈石窟全集·第十一卷:第十三窟 [The Complete Works of Yungang Grottoes, Vol. 11: Cave 13]. Qingdao: Qingdao Chubanshe 青岛出版社 [Qingdao Publishing House]. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Hua 張華. 2007. Yungang Shiku de Jianzhu Jishi 雲岡石窟的建築脊飾 [Roof Ridge Decorations in the Architectural Ornament of the Yungang Grottoes]. Gansu: Dunhuang yanjiu 敦煌研究 [Dunhuang Academy]. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Li 趙莉. 2016a. Xiyu Meishu Quanji·Qiuci Juan·Kezier Shiku Bihua 西域美術全集·龜茲卷·克孜爾石窟壁畫 [The Complete Collection of Fine Arts of the Western Regions, Kucha Volume, Murals of Kizil Caves]. Tianjin: Tianjin Renmin Meishu Chubanshe 天津人民美術出版社 [Tianjin People’s Fine Arts Publishing House]. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Li 趙莉. 2016b. Xiyu Meishu Quanji·Qiuci Juan·Kumutula Shiku Bihua 西域美術全集·龜茲卷·庫木吐喇石窟壁畫 [The Complete Collection of Fine Arts of the Western Regions, Kucha Volume, Murals of Kumutula Caves]. Tianjin: Tianjin Renmin Meishu Chubanshe 天津人民美術出版社 [Tianjin People’s Fine Arts Publishing House]. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Ye 趙曄. 2001. Wu Yue Chun Qiu 吳越春秋 [Spring and Autumn Annals of Wu and Yue]. Beijing: Shutongwen Shuzihua Jishu Youxian Gongsi 書同文數字化技術有限公司 [Unihan Digital Technology Co., Ltd.]. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Yi 朱壹. 2006. Ciqi Huoyanzhu Wenshi Yanjiu 瓷器火焰珠紋飾研究 [Study of the Porcelain’s Flame Bead Decorations]. Nanjing: Dongnan Wenhua 東南文化 Southeast Culture. [Google Scholar]

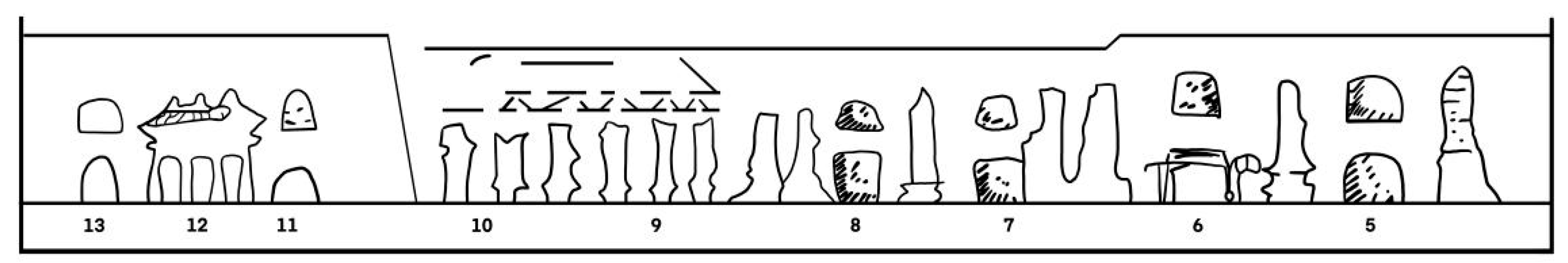

| Main Ridge | Vertical Ridges | Illustration | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central | Both Sides | Both Ends | Upper Section | Lower Section | |||

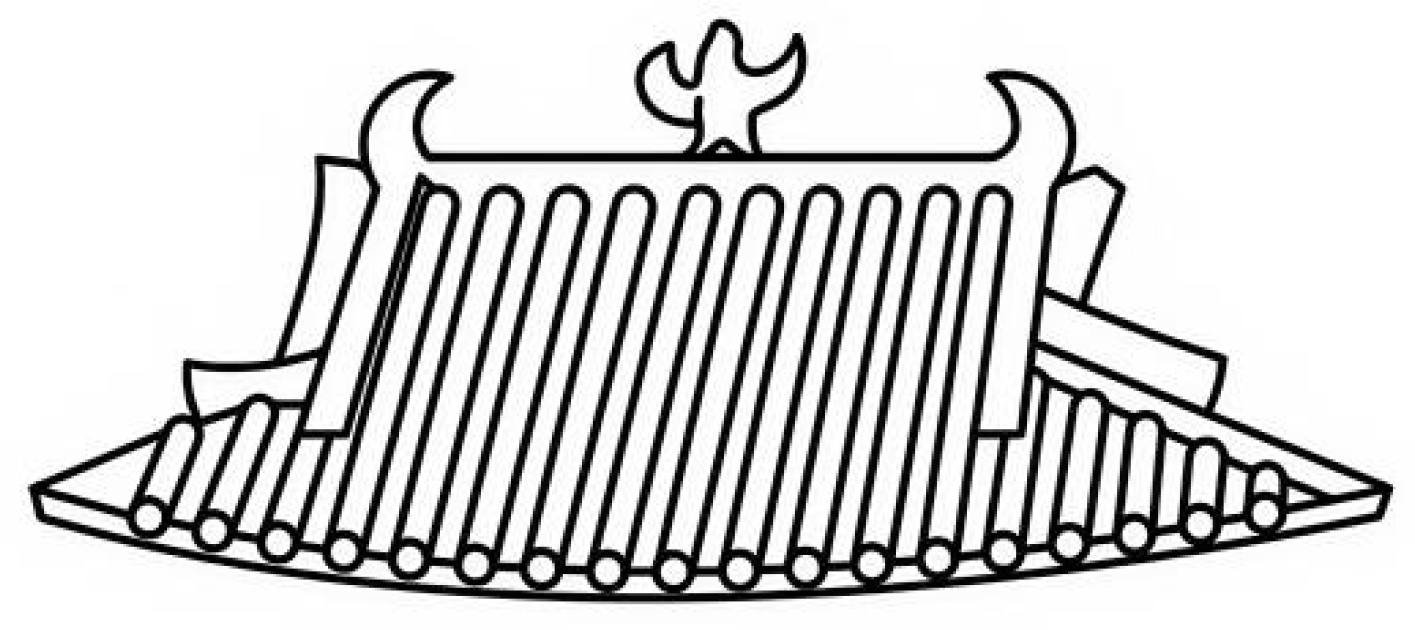

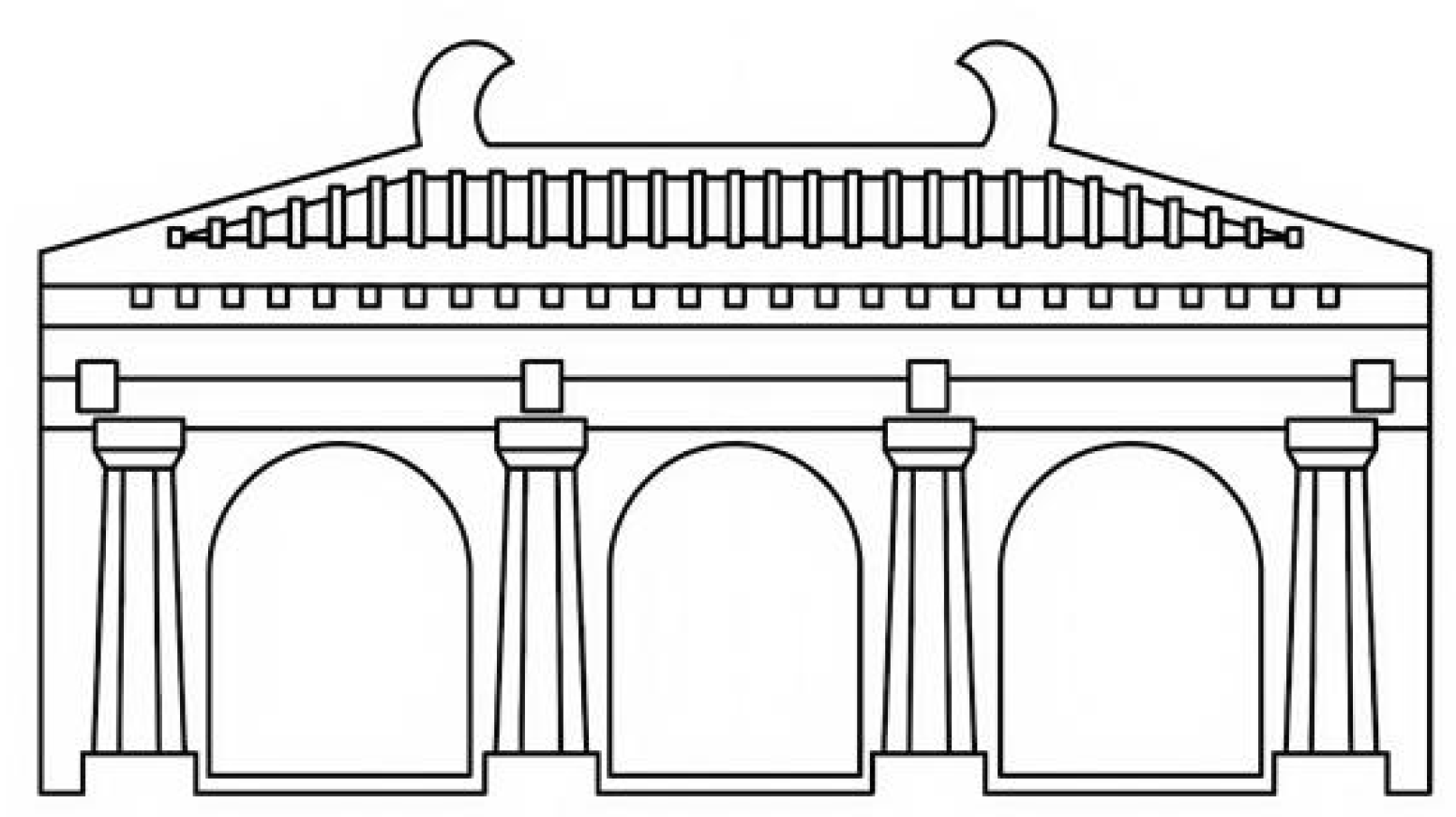

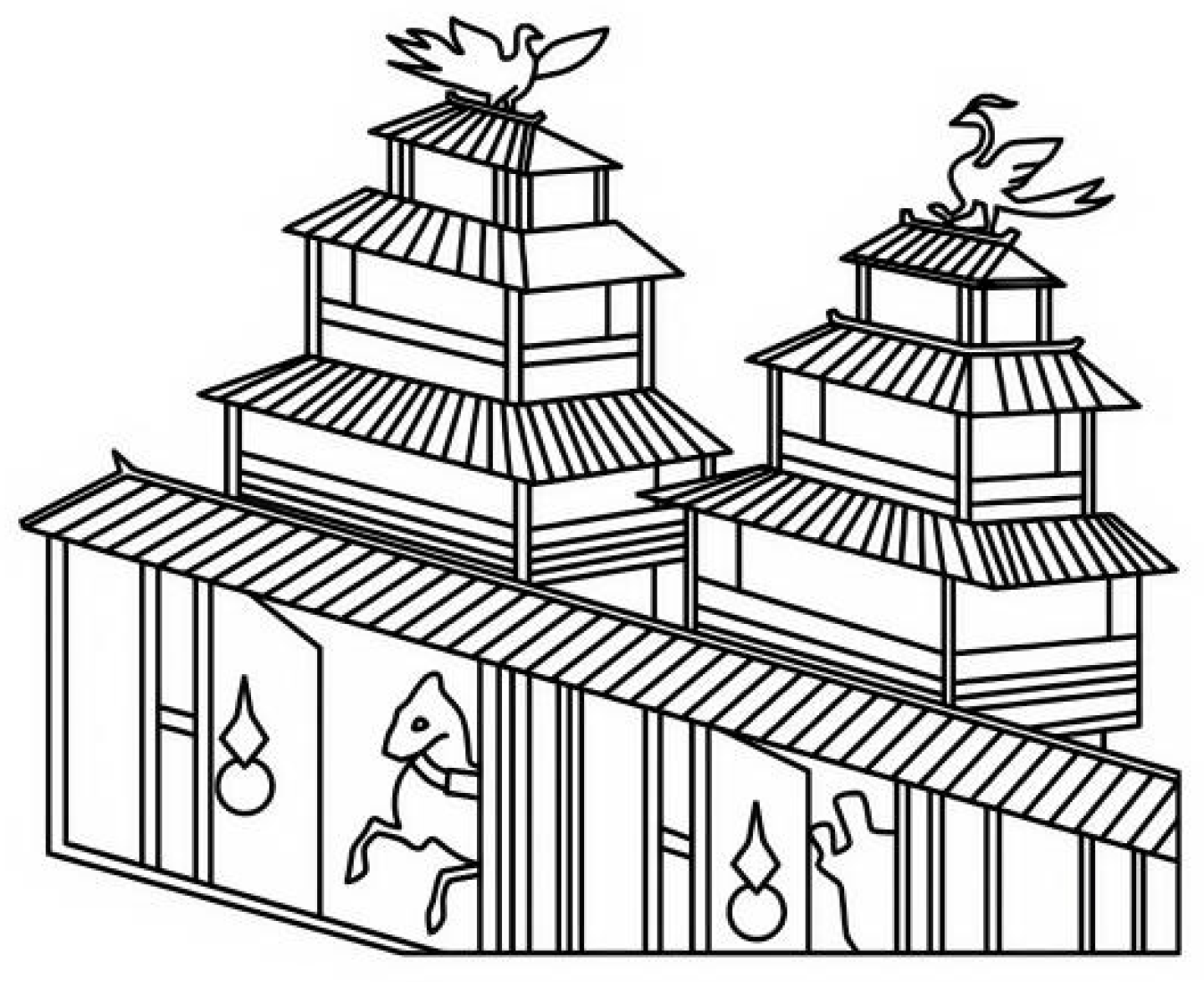

| A | Aa | Garuda | Chiwei | Side-bodied Garuda |  House-shaped niche on the fourth tier of the west wall, front chamber of Cave 9, Yungang Grottoes. After (Zhang et al. 2017b). | ||

| Ab | Triangle Patterns | Garuda Facing Backwards |  The house-shaped niche on the second tier of the western side of the north wall, in the antechamber of Cave 12, Yungang Grottoes. Photograph by authors, 2024. | ||||

| Ac | - | - |  The house-shaped niche to the left of the three-niche statuary unit, located in the first row on the fourth tier of the east wall in Cave 13, Yungang Grottoes.+-- After (Zhang et al. 2017c). | ||||

| B | Ba | Triangle Patterns | Garuda Facing Backwards | Chiwei |  The house-shaped niche located above the three central figures of the Seven Standing Buddhas group, on the south wall of Cave 13, Yungang Grottoes. Photograph by authors, 2024. | ||

| Bb | Triangle Patterns |  House-shaped niche in the narrative reliefs on the third tier of the south wall of the rear chamber at the Yungang Grottoes. After (Zhang et al. 2017b). | |||||

| Bc | - |  The house-shaped niche to the right of the three-niche statuary unit, located in the first row on the fourth tier of the east wall in Cave 13, Yungang Grottoes. After (Zhang et al. 2017c). | |||||

| C | Ca | - | Triangle Patterns |  The house-shaped niche on the third tier of the eastern side of the south wall, in the rear chamber of Cave 10, Yungang Grottoes. After (Zhang et al. 2017a). | |||

| Cb | - |  The doorway on the south wall of the rear chamber in Cave 9, Yungang Grottoes. After (Zhang et al. 2017b). | |||||

| D | Phoenix Bird | - | Garuda Facing Backwards | Chiwei |  The house-shaped niche located above the two standing Buddhas to the east of the Seven Standing Buddhas, on the south wall of Cave 13, Yungang Grottoes. Photograph by authors, 2024. | ||

| E | Triangle Patterns | Flame bead and Triangle Patterns | Triangle Patterns |  The house-shaped niche on the third tier of the central section of the south wall in Cave 6, Yungang Grottoes. Photograph by authors, 2024. | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Z.; Chang, Q. Artistic Integration and Localized Adaptation: An Analysis of Roof Ridge Decorations in the Sinicization Process of the Yungang Grottoes. Religions 2025, 16, 1562. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16121562

Wang Z, Chang Q. Artistic Integration and Localized Adaptation: An Analysis of Roof Ridge Decorations in the Sinicization Process of the Yungang Grottoes. Religions. 2025; 16(12):1562. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16121562

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Zi, and Qing Chang. 2025. "Artistic Integration and Localized Adaptation: An Analysis of Roof Ridge Decorations in the Sinicization Process of the Yungang Grottoes" Religions 16, no. 12: 1562. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16121562

APA StyleWang, Z., & Chang, Q. (2025). Artistic Integration and Localized Adaptation: An Analysis of Roof Ridge Decorations in the Sinicization Process of the Yungang Grottoes. Religions, 16(12), 1562. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16121562