Abstract

The Chinese Weekly, published by the Christian Literature Society for China, functioned as a key platform for the negotiation between Western knowledge and Chinese intellectual culture in late Qing and early Republican China. Supported by an official consignment system and a nationwide distribution network, the newspaper participated deeply in China’s transformation of modern knowledge. Through the introduction of Western concepts in astronomy, geology, medicine, and education, it helped shape new cognitive frameworks through which Chinese literati interpreted the world. The “Illustrated Columns,” containing commentaries from officials and letters from gentry-merchants, illuminated the evolving thought patterns of Chinese intellectual elites as they encountered and reinterpreted Western learning. In the late Qing period, the paper penetrated local administrative structures and cultivated among officials and gentry the belief that “Western newspapers must be read.” Entering the early Republic, it increasingly emphasized reader interaction and inter-journal dialogue, fostering a renewed sense of community among the nation’s knowledge elites. Thus, while The Chinese Weekly served as a major medium for disseminating Western learning, it also became a space where Chinese intellectuals appropriated and localized such knowledge, demonstrating their agency in the processes of cultural and epistemological exchange.

1. Introduction

Newspapers, as a unique arena of knowledge dissemination in modern China, played an irreplaceable role in enlightening the people and guiding public opinion. Timothy Richard (李提摩太), the second general secretary of the Christian Literature Society for China (the C.L.S.C.), once observed that by controlling the discourse of China’s newspaper publishing, one could “control the head and backbone of the nation” (Fang 1981, p. 19). The Chinese Weekly 《大同报》, launched in the early twentieth century by the Society as a successor to A Review of the Times 《万国公报》, was a comprehensive periodical used to promote ideas of social reform among China’s elite. As one scholar noted in reference to The Chinese Progress 《时务报》1, “unlike the earlier missionary periodicals, The Chinese Progress pioneered the precedent of institutionalized reading, having won the strong support of numerous provincial governors and high officials” (Jiang 2019). Here, “institutionalized reading” refers to a socially systematic and organized reading practice ledby official authorities, aimed at disseminating new knowledge and promoting social transformation. In this regard, The Chinese Weekly went even further. Although initiated by missionaries, it developed a mutually beneficial network through the official consignment syste—a mechanismwhereby officials assisted newspaper publishers in selling papers—which enabled the paper to circulate widely among the officialdom of the late Qing and early Republican eras.

An examination of how The Chinese Weekly disseminated Western knowledge to reshape Chinese literati’s worldview, how it cultivated social networks through its distribution practices to secure official support, and how local officials experienced and received the newspaper provides a valuable lens for understanding how the C.L.S.C. constructed a reading community within the modern Chinese publishing market. Existing scholarship has primarily emphasized The Chinese Weekly’s institutional operation and its interactions with the bureaucratic system. Zhao Xiaolan has provided a comprehensive account of the newspaper’s founding, editorial staff, and content characteristics, offering the most detailed introduction to date (Zhao and Wu 2011). Chen Zhe has examined its later decline (Chen 2011). Building upon the historical trajectory of missionary journalism, Song Yanhua has analyzed how missionaries used newspapers as a medium to build networks of communication with Chinese officials (Song 2022). Further, scholars such as Song Yanhua and her collaborators have explored the evangelical and cultural dimensions of newspaper publishing undertaken by the Canadian missionary Donald MacGillivray (季理斐) in Shanghai (Song et al. 2024; Song and Tan 2024). However, few studies have approached missionary periodicals from the perspective of the sociology of knowledge to investigate their deeper connections with literati reading practices and cognitive transformation.

Building on the framework of The Chinese Weekly’s dissemination of Western learning, this article sought to reconstruct how local officials, through newspaper reading, engaged in the cognitive deconstruction and synthesis of “new Western knowledge.” By tracing these processes, it revealed the underlying logic of cultural power negotiation embedded in late Qing and early Republican reading practices. The study drew extensively on archival materials from the United Church of Canada Archives, the University of Toronto Library, the Shanghai Municipal Archives, and the East China Theological Seminary—many of which had not been cited in previous scholarship. Through integrating these primary sources with a sociological perspective on knowledge, the article offered a more dynamic understanding of how missionary publications mediated intellectual transformation.

This study provided new insights into the intersection of missionary publishing, intellectual transformation, and the sociology of knowledge in modern China. By shifting the focus from institutional operations to “reading integration”—that is, the ways in which Chinese intellectuals read The Chinese Weekly and assimilated its ideas through processes of understanding, interpretation, and cognitive incorporation—it deepened the understanding of how The Chinese Weekly mediated the encounter between Western learning and Chinese intellectual traditions. Unlike previous research that had primarily examined missionary periodicals from the perspective of editorial policy or religious propaganda, this article foregrounded the epistemic interactions between missionaries and Chinese elites as a process of mutual negotiation and recontextualization.

Furthermore, by incorporating newly uncovered archival materials from Canada and China, the study reconstructed the transnational networks that sustained the circulation of The Chinese Weekly. It demonstrated that reading was not a passive act of cultural consumption but an active arena of meaning-making and identity formation, through which Chinese officials and literati redefined their relationship with modernity and the West. In doing so, the research contributed to a more nuanced understanding of the cultural agency of Chinese intellectuals and the hybrid nature of modern knowledge formation in a missionary context.

2. The Elite Positioning of The Chinese Weekly and Its Role in Disseminating Western Knowledge

On 29 February 1904, the C.L.S.C. inaugurated The Chinese Weekly (Tatung Pao). The title “Tatung” was deliberately chosen amid intensified imperial competition, reflecting the aspiration to “dissolve prejudices, dispel hostility, eliminate distinctions between East and West, transcend differences between yellow and white races, and ultimately bring all under the realm of Great Harmony” (A Review of the Times, 1904, p. 64). Initially launched as a weekly journal under the editorship of William A. Cornaby (高葆真), a British Methodist missionary, the paper defined its mission as “exchanging knowledge and introducing civilization,” revealing its clear orientation toward China’s educated elites.

In 1907, The Chinese Weekly underwent a major reorganization. Its objectives were reaffirmed and systematically articulated as “first, to assist the New Policies; second, to strengthen education; and third, to cultivate character” (The Chinese Weekly, 1907, p. 7). Following this reorientation, the newspaper published a large number of essays devoted to the dissemination of Western learning, aligning closely with contemporary calls for social reform. Through these efforts, The Chinese Weekly not only attracted broad readership within China but also drew considerable attention from observers abroad.

The First World War in 1914 severely disrupted the C.L.S.C.’s missionary and publishing work in China. lts long-held belief in “taking Western society as a model for China’s reform” was shaken asthe war eroded Chinese trust in Europe. Consequently, scientific subjects receded from its publications: “The scientific subjects that missionaries once eagerly pursued-astronomy, physicsnatural history, agriculture, and the like-are now seldom touched upon or have been neglectedaltogether” (Ho 2004, p. 175).

In 1915, the newspaper was converted into The Chinese Monthly, with five sections—llustrations. Essays, Records, Translations, and Miscellanea—and greater emphasis on philosophy and biography. Despite its reform, the newspaper ceased publication in 1917 after 575 issues. Nevertheless, The Chinese Weekly remained a landmark in the C.L.S.C.’s history in China, exemplifying its ambition toshape modern Chinese knowledge and print culture through missionary publishing.

2.1. Dissemination of Western Astronomical and Geological Knowledge

Astronomy occupied a distinctive position in traditional China, imbued with profound political significance and sacred symbolism, and long regarded as a branch of official learning. Ordinary people, however, possessed little understanding of celestial phenomena such as meteorites. As recorded in Yiwen lu 《益闻录》, when a meteorite fell in a village in 1896, “the crowd regarded it as a treasure; each took a hammer to strike off a fragment and stored it away, valuing it as if it were gold or jade” (Yiwen lu, 1896, p. 442). Responding to the growing demand for scientific knowledge in the early twentieth century, The Chinese Weekly systematically introduced Western concepts in astronomy and geology.

In 1907, under the editorship of Evan Morgan (莫安仁), the newspaper published a series of translated essays on the solar system, offering detailed explanations of cosmic stones and celestial bodies. Morgan explained that meteorites emit light because, when entering the Earth’s atmosphere at speeds ranging from tens to over a hundred miles per second, they experience intense friction with the air, producing high temperatures that ignite their outer layers. He further noted that all meteorites within the solar system follow elliptical orbits: “All that move in ellipses must be related to the solar system, belonging to the same system as the Sun,” adding that the Earth’s own orbit is likewise elliptical (Morgan and Pan 1907, p. 17).

Beyond meteorites, the paper also provided detailed accounts of meteors. One article, titled “Meteors, Also Known as Shooting Stars, Commonly Called Thief Stars,” was particularly significant in identifying meteors and meteorites as the same kind of substance originating in outer space (Morgan and Pan 1907, p. 18). It also discussed variations in the velocity and color of different constellations, making it one of the earliest comprehensive Chinese-language reports on Western astronomical studies of constellations in the early Republican era.

In the field of geology, beginning in March 1907, The Chinese Weekly serialized An Introduction to Geology 《地学序言》 by the British missionary W. Gilbert Walshe (华立熙). The series introduced both the external and internal characteristics of the Earth. From an external perspective, it explained the Earth’s rotation and revolution around the Sun, noting that the revolution caused the alternation of the four seasons. “During the 365 days of the year, sunlight gradually moves northward from the equator and then returns, taking 185 days; it then moves southward from the equator and returns again, also in 185 days,” meaning that the Sun’s direct rays shift between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn, with the equator as the midpoint (Walshe and Zhang 1907, p. 21). From an internal perspective, Walshe noted that approximately three-quarters of the Earth’s surface is covered by water, while land occupies only one-quarter. The six continents were listed in order of increasing size as follows: Oceania (3 million square miles), Europe (3.75 million), South America (7 million), North America (8 million), Africa (11.025 million), and Asia (17 million) (Walshe and Zhang 1907, p. 19).

Additionally, The Chinese Weekly translated excerpts from The Age of the Earth by the British scholar William Roberts, which combined findings from biology, geology, and astronomy to explore the planet’s age. Roberts regarded tidal motion as a “celestial deceleration mechanism,” suggesting that the frictional interaction between the Earth and the Moon caused by tides could be used to estimate the Earth’s age (Roberts 1909, p. 18). He argued that the Earth’s rotation had gradually slowed over time and, based on this reasoning, calculated that the Earth was approximately four million years old. Although this conclusion proved erroneous, the introduction of tidal dynamics into geological chronology represented a significant methodological innovation. Collectively, these translated writings demonstrate The Chinese Weekly’s pioneering role in popularizing geological and astronomical knowledge, as well as in introducing Western scientific methodologies to Chinese readers during the early Republican era.

2.2. Promoting Modern Agricultural Techniques

The early twentieth century marked a period of remarkable advancement in botanical science. Across Europe and North America, figures such as the American botanist Luther Burbank (1849–1926) led pioneering efforts in crop improvement, whose innovations soon spread across Asia and Africa. By contrast, late Qing China faced recurrent natural disasters, and its traditional agrarian economy was in visible decline. In the wake of the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895, reform-minded intellectuals increasingly regarded agricultural revitalization as essential to national recovery and modernization. Against this backdrop, The Chinese Weekly actively championed agricultural reform as both a practical response to social crisis and a pathway toward national regeneration.

The newspaper not only introduced Western agricultural technologies but also devoted sustained attention to the recurring floods of the Huai River. Between 1910 and 1911, fifty-six counties in Anhui Province were devastated by catastrophic floods that triggered widespread social unrest: “The weak perished in ditches and ravines; the strong scattered to distant places; and acts of violence and plunder arose as a result” (MacGillivray 1914, p. 6). Donald MacGillivray, one of the editors of The Chinese Weekly, firmly maintained that systematic dredging of river channels was the only fundamental solution to China’s recurrent floods. It is worth noting that MacGillivray, who later became the fourth general secretary of the C.L.S.C., spent more than three decades in China (1898–1930), most of which were devoted to his work in Shanghai. There, he played a pivotal role in shaping modern China’s publishing and periodical distribution industries. According to the author’s research, between 1907 and 1914, MacGillivray contributed over 120 articles to The Chinese Weekly, making him one of its most prolific contributors. In 1913, he succeeded Evan Morgan as the newspaper’s chief editor, further consolidating his influence over its editorial direction and intellectual agenda.

In a series of essays—including “On the Relationship between Hydraulics and Agriculture after the Discussion of Zhejiang Tides”—MacGillivray argued that the key to agricultural development lay in the effective mobilization of human resources, and that among all agricultural concerns, water management was the most urgent and essential. He observed that rainfall distribution across China was extremely uneven: the Huai River frequently overflowed, submerging Xiangtan and leaving local inhabitants in constant danger, while Shaanxi and Shanxi provinces suffered from persistent droughts and locust infestations due to the lack of effective water storage methods. To address these problems, he proposed a practical and forward-looking solution: “Let the waters from highlands be discharged into the lowlands, and let the waters from lowlands be channeled to irrigate the highlands” (MacGillivray and Allen 1914, p. 5)—a concept that in principle anticipated China’s modern South-to-North Water Transfer Project.

The agricultural column of The Chinese Weekly systematically introduced advances in agricultural science, promoting the transformation of traditional Chinese agronomy through empirical experimentation. In response to the sharp rise in rice prices across China in 1910, the newspaper published “A New Method of Rice Cultivation in the United States,” which presented American innovations in mechanized land improvement and specialized rice breeding (MacGillivray 1910, p. 11). These technologies were framed as valuable references for Chinese agriculture and were later translated and disseminated in Japan and Russia.

Similarly, in “The Improvement of the Taro and the Eggplant,” Evan Morgan detailed how American agronomists scientifically grafted and improved the San Francisco taro (Morgan and Xu 1907, p. 15). Through comparative experiments, they selected superior traits, doubling the starch content to 50% and thereby enhancing its economic value. The newspaper also introduced hybridization techniques for flowers such as daisies, lilies, and cacti, along with grafting methods for peaches and plums—demonstrating how modern agricultural innovation took shape through experiment and cross-cultural transmission.

In 1913, following a severe drought in Henan Province, MacGillivray submitted his own agricultural essays to Chinese government officials. He later recalled: “I also sent one of our articles on Dry Farming to the Board of Agriculture in Peking, pointing out how necessary the new art of dry farming was to the draught-cursed regions of Honan, Shansi, etc. The Board published an Agricultural Journal, and in the second volume, No. 20, they reproduced this article from the Ta Tung Pao (The Chinese Weekly). The introdaction of dry farmine and durun wheat may be the means, under God, of saving the lives of millions of people.” (Letter from MacGillivray to MacKay 1913, p. 1). This promotion of “dry-land wheat cultivation” was subsequently reprinted in An Elementary Discussion of Agriculture 《农业浅说》 and Agricultural and Commercial Bulletin 《农商公报》.

Moreover, The Chinese Weekly incorporated chemical science into agricultural discourse to improve soil quality. In the serialized essay On the Need for Chemical Methods in Agricultural Studies of Soil Properties, the paper translated sections from American works on soil science, analyzing the chemical functions of carbon, calcium, and magnesium in plant growth (Morgan and Xu 1907, pp. 11–5). These scientific transfers introduced not only practical techniques such as grafting, breeding, and mechanized cultivation but also the chemical understanding of soil composition. Collectively, they marked a key step in China’s transition from empirical farming practices toward an experimental and scientifically informed agronomy.

2.3. Introducing Western Educational Systems

During the period of educational transformation in modern China, The Chinese Weekly paid particular attention to issues concerning children’s education. In his 1914 article “Education Based upon Primary Schooling,” Donald MacGillivray argued that elementary education formed the foundation of both moral and intellectual cultivation. He urged that each province should promptly establish primary schools—not only to train future candidates for higher learning but also to lay the groundwork for national enlightenment. Drawing on Western models of a “step-by-step” educational system, he emphasized the importance of constructing a coherent hierarchy within China’s emerging educational structure (MacGillivray 1914, p. 6).

Regarding early childhood education, MacGillivray proposed in A Mirror of Chinese Education that children should begin kindergarten at the age of four, following the progressive principle of “focusing on physical education in early childhood and on intellectual education in later years” (MacGillivray and Bao 1913, p. 36). He stressed that educational reform in China must begin with foundational enlightenment, enabling the nation to keep pace with advanced countries.

The newspaper also introduced kindergarten methods that integrated play and learning, such as using six-colored balls for shape and number recognition, comparing squares and circles, and engaging in constructive assembly games. For example, each box of six-colored balls contained three primary and three mixed colors, used to teach children to distinguish shapes, recognize colors, and count objects. These exercises were accompanied by rhythmic songs such as: “The ball moves left and right, left and right without leaving the hand; the ball moves forward and backward, forward and backward and then returns again.” By replacing rote memorization with tangible, activity-based instruction, this method encouraged children to acquire everyday understanding and basic concepts naturally through play (Chen 1908, p. 13). On 22 July 1915, Yuan Shikai (袁世凯) issued an official decree declaring that “national education must be founded upon primary schooling; by observing the conduct of primary school pupils, one may foresee the rise or decline of the nation” (Educational Bulletin 1915, p. 16). This pronouncement reflected the broader consonance between The Chinese Weekly’s advocacy for elementary education and the reformist agenda of the time.

Moreover, The Chinese Weekly offered significant reference models for China’s educational transformation through its serialization of Summary of the U.S. Educational Reports (1908) and Report on Education in Meiji Japan (1907). The American system, grounded in universal education, emphasized “the study of science and investigation” (格致之学) in secondary schools and encouraged debate and inquiry at the university level—standing in sharp contrast to the late-Qing private tutoring system, which “required only rote recitation and conformity, without concern for true understanding” (Bai 1908, p. 17). Meanwhile, Japan had launched a nationwide educational campaign that financed schools through multiple channels—state appropriations, private donations, and public savings—and implemented free education. Teachers there enjoyed high social status, “holding official rank equivalent to the third degree, comparable to prefectural officials in China,” a striking contrast to the marginal and inferior position of educators in the late Qing dynasty (Morgan and Guan 1907, p. 15).

In response to the growing enthusiasm in China for imitating Western systems, MacGillivray issued a strong caution in his article “A Discussion on the Essentials of Chinese Education.” He warned against the blind transplantation of foreign models, urging that reform be grounded in China’s own conditions—“preserving propriety and morality” while balancing the cultivation of practical talent with the transmission of “inherent moral values” (MacGillivray 1914, p. 7). He further advocated safeguarding the integrity of the Chinese written language as a cornerstone of educational modernization, envisioning a localized reform that harmonized Western learning with traditional ethical principles. Through a combination of translation, commentary, and comparative analysis, The Chinese Weekly articulated an educational vision that sought both the scientific rationality of the West and the moral continuity of Chinese tradition.

2.4. Disseminating Western Medical Knowledge

In modern China, many foreign missionaries harbored prejudiced views toward traditional Chinese medicine. The British missionary J. Sadler of the London Missionary Society once condemned Chinese physicians for “being ignorant of human physiology, unfamiliar with anatomical methods, rigidly adhering to ancient prescriptions, falsely claiming secret arts, and even resorting to spirits and incantations—showing no difference from Europe before its enlightenment” (J. Sadler 1910, p. 9). At the same time, numerous Qing officials were eager to introduce Western science and technology to strengthen the nation. Against this backdrop, The Chinese Weekly systematically presented the history of Western epidemic prevention and, in response to outbreaks of plague, cholera, and other infectious diseases, disseminated modern techniques of pathogen control and public-health hygiene.

During the 1910 plague outbreak in Shanghai, The Chinese Weekly developed a dual narrative of epidemic prevention. On the one hand, it promoted the London model of quarantine: “All rats and fleas must be kept out of houses and off the body; those already infected should be relocated to isolated areas or hospitals, their residences enclosed with iron fencing, the ground paved with cement, and the surroundings disinfected with medicinal solutions” (Morgan 1910, p. 2). On the other hand, it highlighted the contest for epidemic-control authority between Chinese and Western administrations. The newspaper reported that the Shanghai Municipal Council had resolved to permit “Chinese residents to inspect epidemic cases, establish their own hospitals, and designate independent quarantine zones,” with the sanitary boundary drawn along North Henan Road and Tibet Road—symbolizing the assertion of a national sanitary sphere within a colonial medical framework (Morgan 1910, p. 6).

This narrative tension was equally evident in the paper’s discussion of cholera prevention. The article “On the Causes and Preventive Methods of Cholera” replaced the traditional “miasma theory” with the germ theory of disease, introducing practical hygienic measures such as boiling water, sterilizing food, and keeping the abdomen warm (Cornaby and Guan 1908, p. 10). In doing so, it transformed traditional conceptions of cleanliness into operational frameworks of public health, facilitating the diffusion of a bacteriological understanding of epidemic prevention within Chinese society.

Beyond disease control, The Chinese Weekly also advocated for the legalization of human dissection in China. Constrained by long-standing cultural taboos, Chinese medicine had historically resisted anatomical study. The paper published a special report entitled “New Law Permitting Anatomical Dissection in Hubei,” announcing that the province had issued a regulation allowing physicians to conduct dissections—a precedent soon followed by others (MacGillivray 1914, p. 36). Using this opportunity, the newspaper introduced Western anatomical knowledge and encouraged civic-minded individuals to donate their bodies to medical education for the benefit of future patients.

In another essay, “A New Direction in Medicine,” the paper argued that the limited acceptance of Western medicine in China stemmed from public skepticism and resistance: “Alas, patients go to hospitals either too late for treatment or delay their visits even when gravely ill; some, even when afflicted with contagious diseases, still refuse to seek medical care” (MacGillivray 1914, p. 36). The article thus advanced the medical principle of “treating disease before its onset,” urging the government to prioritize preventive medicine and public health. In “A Sound Strategy for the Development of Chinese Medicine,” MacGillivray further emphasized that the revitalization of China’s medical system “could only be achieved through a grand plan of Sino-foreign cooperation” (MacGillivray 1914, p. 6). Citing the success of Yale Hospital in Changsha, he appealed for state support to promote collaboration between Chinese and Western medicine as a means of elevating the nation’s overall medical standards.

In 1916, Donald MacGillivray published “Reflections on the Chinese Medical Association” following the First National Medical Congress organized by Wu Liande (伍连德) and others. In this article, he called upon physicians and journalists of conscience to unite in alleviating the suffering of the people. The Chinese Medical Journal 《中华医学杂志》responded: “All members of our medical community should take Dr. MacGillivray’s compassion as their own and work earnestly to disseminate medical knowledge, so as not to fail his heartfelt exhortations” (MacGillivray 1916, p. 61).

It is noteworthy that, to appeal to Chinese literati, successive editors of The Chinese Weekly skillfully employed familiar idioms and classical quotations. In “The Need for National Attention to Children’s Physical Education,” Evan Morgan cited the Guanzi 《管子》2: “For a plan of ten years, plant trees; for a plan of a hundred years, cultivate people” (Morgan 1912, p. 1). In “Reflections on the European War and Religion,” Donald MacGillivray invoked the idiom “as unrelated as wind and cattle” (风马牛之不相及)3 to argue that Christianity was fundamentally incompatible with warfare (MacGillivray 1914, p. 1). He also quoted the Mencian maxim, When Heaven is about to confer a great responsibility on someone, it first frustrates his mind, wears out his sinews and bones, and starves his body,” to suggest that present suffering is the prelude to future blessing. By juxtaposing Confucian moral reasoning with Christian theology, The Chinese Weekly localized Western discourse through culturally resonant rhetoric, constructing a form of indigenous enlightenment that facilitated the internalization of Western thought in China.

In addition, the editors once invited Zhang Jian (张謇), a leading modern Chinese industrialist, to inscribe a dedication for the newspaper’s cover to enhance its prestige. Figure 1 shows Zhang Jian’s calligraphic inscription from March 1912 displayed on the Chinese edition’s front page.

Figure 1.

Zhang Jian’s inscription4 (The Chinese Weekly 1913. Source: [the National Index to Chinese Newspapers and Periodicals], an open-access resource. URL: https://webvpn.qdu.edu.cn/https/77726476706e69737468656265737421e7e056d2243e6a5b6d11c7af9758/literature/browseEntity/d57d89059f0b71140ee85a306ad83223?bc=&source=FULL_BROWSER (accessed on 25 November 2025)).

Taken as a whole, The Chinese Weekly epitomized the process by which late Qing China in corporated Western knowledge to facilitate societal reform. Its editorial vision—rooted in Timothy Richard’s ideal of the universality of knowledge—integrated Western practical sciences such as agriculture, hydraulics, and other applied disciplines into the post–Sino-Japanese War discourse of statecraft and national salvation. By engaging with urgent issues like the management of the Huai River floods, the newspaper forged a tangible link between scientific knowledge and the practical imperatives of national survival. Through its empirical explanations of astronomy, it dispelled popular superstitions surrounding celestial phenomena such as meteorites, thereby reconstructing the cognitive frameworks through which China’s educated elites perceived the natural world.

Prominent intellectuals including Kang Youwei (康有为) and Liang Qichao (梁启超) were among those inspired by its influence, demonstrating the intellectual resonance of the C.L.S.C.’s synthesis of Confucian pragmatic statecraft and Western scientific rationality (Bihui 1924, p. 10). This mode of dissemination not only continued the missionary aim of spreading the gospel through printed materials, but also reshaped the role of Western learning in China. Although The Chinese Weekly was founded by missionaries and its introduction of Western knowledge carried an inherent religious purpose, the information it delivered gradually took on a broader significance. As cutting-edge knowledge of science, technology, and practical affairs entered China through the paper, it became an important source of new ideas for a society in transition. In this process, Western learning—initially tied to missionary discourse—came to be viewed as reliable, secular, and authoritative knowledge that could inform reformist thinking and guide efforts to transform society.

In doing so, The Chinese Weekly transcended its missionary origins and emerged as an intellectualplatform bridging faith and scientific rationality, contributing significantly to China’s modernizationand to ideological enlightenment—that is, the introduction of new scientific and modernperspectives that challenged traditional understandings among China’s educated elites andbroadened their intellectual horizons.

3. Collaborative Dissemination: Missionaries and Chinese Intellectual Elites in the Circulation of The Chinese Weekly

The C.L.S.C. published newspapers with the goal of introducing Western civilization to contemporary Chinese readers and, through this process, promoting social transformation. As Timothy Richard once observed, “Through literary propaganda, millions of Chinese minds can be transformed” (Fang 1981, p. 19). However, the dissemination of such publications was by no means a simple undertaking. It required navigating multiple stages—including fundraising, editing, printing, and marketing—while remaining contingent upon external factors such as postal infrastructure and political conditions. To ensure that a wider audience of Chinese officials and scholars could access its periodicals, The Chinese Weekly implemented a diversified distribution strategy that extended across the country, actively participating in the C.L.S.C.’s larger project of constructing a nationwide reading community.

3.1. Complimentary Copies and Public Contributions

The practice of distributing complimentary copies was one of the C.L.S.C.’s key strategies in building a reading community. This initiative involved sending newly published periodicals free of charge to Chinese officials and scholars. The Society adhered to a policy that every printed publication—whether sold, consigned, gifted, or mailed as a back issue—had to be fully utilized. In its early years, The Chinese Weekly gained recognition primarily through this practice: “From now on, every day and hereafter, free copies of the newspaper will be delivered into the hands of all principal officials throughout the empire” (The North-China Herald and Supreme Court & Consular Gazette 1904, p. 45.) Prince Su, Aisin-Gioro Shanqi (爱新觉罗·善耆), described his first encounter with the newspaper: “I have received the graciously sent issue of your esteemed newspaper. Upon reading it, my admiration knows no bounds. Its extensive and refined contents greatly benefit later learners. Its merit is indeed extraordinary, and I intend to subscribe immediately” (Shanqi 1907, p. 1). Figure 2 presents a portrait of Shanqi that appeared on the newspaper’s cover. By 1905, The Chinese Weekly was reportedly being read weekly by more than sixty senior government officials across China.

Figure 2.

Portrait of Shanqi (Shanqi 1907, Source: [the National Index to Chinese Newspapers and Periodicals], an open-access resource. URL: https://webvpn.qdu.edu.cn/https/77726476706e69737468656265737421e7e056d2243e6a5b6d11c7af9758/search/detail/f8a9fa651c239f63ea3260f1ea97020c/7/69284517f74f7f4c68a8c150 (accessed on 25 November 2025)).

In 1907, Li Chaoqiong (李超琼), the magistrate of Shanghai County, likewise expressed his appreciation: “Having received a complimentary copy of The Chinese Weekly, I find that it expounds political learning and integrates both Chinese and Western principles with remarkable balance. As it reforms the conventions of journalism into the structure of a magazine, its format is particularly elegant. The editors and translators have displayed admirable dedication. It deserves regular publication and wide circulation throughout the empire” (Li 1907, p. 1). Through such early promotional and circulation efforts, The Chinese Weekly achieved considerable visibility among government officials, establishing its readership through complimentary trial distribution.

The practice of complimentary circulation was also evident in the handling of back issues. In 1906, The Chinese Recorder and Missionary Journal published a letter from Donald MacGillivray to the Christian reader J. E. Cardwell, in which he explained the C.L.S.C.’s policy on distributing surplus publications. Readers could obtain back issues of A Review of the Times and The Chinese Weekly simply by paying the postage cost: “The Christian Literature Society is prepared to supply for free distribution parcels of back numbers of the Church Review, Review of the Times, and The Chinese Weekly. These periodicals contain much matter of permanent value, which would be found useful in leading readers to a fuller apprehension of the value of truth and progress” (The Chinese Recorder and Missionary Journal 1906, p. 708). The required postage fee was three yuan, with any remaining balance refunded to the applicant. This promotional strategy not only enabled the Society to manage surplus stock efficiently but also allowed readers with limited means to access the periodicals at minimal cost.

Another important means by which The Chinese Weekly engaged with its readership was through public calls for submissions on current affairs. From Volume 7, Issues 1–7 (1907), the paper published for two consecutive months a “Call for Essays” on the suppression of opium in China, offering rewards for outstanding contributions. In addition, the newspaper openly invited submissions on a broad range of topics, declaring: “We warmly welcome distinguished scholars at home and abroad to contribute their fine writings. Any valuable manuscripts presented to this journal will be carefully selected and published for the benefit of society. Kindly send all submissions to our office” (The Chinese Weekly 1907). These public solicitations for essays not only diversified the newspaper’s sources of content but also strengthened its interaction with readers, fostering a participatory reading culture around The Chinese Weekly and expanding the intellectual community it sought to build.

3.2. Publishing Portraits and Official Consignment of Newspapers

The most effective strategy employed by the C.L.S.C. in promoting The Chinese Weekly was the official consignment system, under which government officials and local gentry directly subscribed to or resold the newspaper. Timothy Richard, Donald MacGillivray, William A. Cornaby, and Evan Morgan all corresponded with high-ranking Chinese officials to solicit assistance in distributing the paper—an unprecedented practice in the history of missionary Chinese-language journalism.

In 1907, the editorial office of The Chinese Weekly sent a letter to Wu Tingbin (吴廷斌), the Financial Commissioner of Shandong, requesting his support for consignment sales. Wu replied affirmatively: “Regarding your request for the distribution of The Chinese Weekly, it shall be duly carried out” (Wu 1907, p. 2). Shortly thereafter, the Shandong Governor Yang Shixiang (杨士骧) also responded: “I have consulted with Commissioner Wu and hereby request that nine hundred copies be sent with each issue for broader circulation” (Yang 1907, p. 1). Figure 3 presents a portrait of Yang Shixiang that appeared on the newspaper’s cover.

Figure 3.

Portrait of Yang Shixiang (Yang 1907, Source: [the National Index to Chinese Newspapers and Periodicals], an open-access resource. URL: https://webvpn.qdu.edu.cn/https/77726476706e69737468656265737421e7e056d2243e6a5b6d11c7af9758/search/detail/4d777ad1c35847a628353f4482770fe1/7/6928477419ef830dee994a7b (accessed on 25 November 2025)).

Beyond Shandong; officials from several other provinces also took an active part in the newspaper’s consignment scheme. Hu Xianglin (胡湘林); the Provincial Treasurer of Guangdong; remarked that the task should be “handled directly through the provincial educational commissioner to ensure efficiency” (Hu 1908, p. 1). Enshou (恩寿); the Governor of Shanxi; likewise expressed his willingness to cooperate; stating: “As for the consignment of The Chinese Weekly; I shall do my utmost within my humble capacity” (En 1907, p. 1). Zhou Fu (周馥); the Viceroy of Liangguang; also replied affirmatively: “Please send one hundred copies first; beginning with the first month of next year according to the Chinese calendar. We shall observe whether sales proceed smoothly and then consider an increase” (Zhou 1907, p. 1). Figure 4 shows a portrait of Zhou Fu that appeared on the newspaper’s cover

Figure 4.

Portrait of Zhou Fu (Zhou 1907, Source: [the National Index to Chinese Newspapers and Periodicals], an open-access resource. URL: https://webvpn.qdu.edu.cn/https/77726476706e69737468656265737421e7e056d2243e6a5b6d11c7af9758/search/detail/cdc2b7d2229413f076a61e5f6d63e67b/7/6928468a00439e53791cd8dc (accessed on 25 November 2025)).

Support for the consignment of The Chinese Weekly also extended to the northeastern provinces of China. Cheng Dequan (程德全), the Governor of Heilongjiang, responded: “Having received your esteemed letter concerning the consignment of newspapers in various provinces, I shall duly comply. Please proceed with the distribution and send copies regularly, so as to broaden public knowledge” (Cheng 1907, p. 1). Da Gui (达桂), the Military Governor of Jilin, likewise expressed his endorsement, noting the scarcity of officials in the border region and proposing an initial consignment of fifty copies to promote readership: “The gentry and people of Jilin will surely be inspired by this example, eagerly seeking to read the paper and subsequently increasing their subscriptions” (Da 1907, p. 1). Even in the more remote northwestern provinces, The Chinese Weekly circulated actively. Cao Hongxun (曹鸿勋), the Governor of Shaanxi, stated: “I have instructed all subordinate prefectures to purchase more copies directly from your Society to ensure wider circulation and reading” (Cao 1907, p. 1).

The willingness of officials to participate in the consignment system was closely linked to the newspaper’s introduction, in 1907, of the Illustrated Portraits Column, which featured portraits of prominent Chinese and foreign dignitaries. For many officials, appearing in the paper became a symbol of distinction—a means of shaping public image and enhancing social prestige. Wu Tingbin, the Financial Commissioner of Shandong, remarked: “Now that it is published in your esteemed newspaper and circulated both at home and abroad, my reputation has greatly increased, and I feel deeply honored. Though I am not a man of letters like Sima Xiangru (司马相如), my likeness has become known across the seas; though my talents fall short of Di Renjie (狄仁杰), my name has nevertheless spread to distant lands” (Wu 1907, p. 1).

Na Tong (那桐), Grand Secretary of the Dongge and Minister of the Interior, expressed a similar sentiment: “I have received your letter proposing to compile portraits of eminent figures, Chinese and foreign, for publication. Though I am unworthy of such acquaintance and lack the grace and virtue to merit this inclusion, I am nonetheless humbled by the honor” (Na 1908, p. 1). Officials were eager to appear in The Chinese Weekly for two principal reasons: first, the broad influence and wide circulation of the Christian Literature Society’s publications; and second, the newspaper’s superior printing quality compared with other periodicals of the time. In an era when newspapers served as a key arena of public visibility, the C.L.S.C.’s inclusion of official portraits represented an innovative mode of image management. It not only elevated officials’ social prominence but also enabled the Society to expand its reach through official consignment—an exemplary manifestation of mutual benefit between knowledge and power.

3.3. Establishing the News Bureau

In the late Qing period, the widely circulated Sichuan Mandarin Gazette 《四川官话》frequently reprinted articles from The Chinese Weekly, particularly those concerning foreign affairs—such as the treatment of tributary states, the diplomacy of empresses, and issues of colonial maritime defense. These reprints aimed to broaden public awareness and promote enlightenment among readers. As Wang Renwen (王人文), the Provincial Treasurer of Sichuan, remarked, “The Chinese Weekly has long been popular throughout Sichuan” (Wang 1909, p. 1). Other official gazettes, including the Qinzhong Official Gazette 《秦中官报》, the Sichuan Educational Gazette 《四川教育官报》, and the Gazette of the Preparatory Constitutional Association 《预备立宪公会报》, also regularly reprinted The Chinese Weekly’s latest essays on education, agriculture, and finance.

After the founding of the Republic, as government subscriptions to the publications of the C.L.S.C. declined, the Society began using the number of reprints its articles received in other newspapers as an indicator of social influence. In 1913, the C.L.S.C. established a News Bureau and introduced a “reprint-for-gift” policy: newspapers that reprinted articles from the Society’s publications would receive complimentary copies of its latest issues. This approach significantly strengthened channels of communication and cooperation between the C.L.S.C. and Chinese press organizations. The News Bureau mailed selected articles from The Chinese Weekly twice a month to leading Chinese newspapers, “hoping that they would reprint tham and help to form public opinion on topics of vital importance to the chinese” (Letter from MacGillivray to MacKay 1914, p. 2).

Donald MacGillivray also personally undertook the task of distributing essays nationwide:

“I have been reprinting the leading articles in the Ta Tung Pao since I took the editorship of it and sending them out to about twenty papers in different parts of China, There has been a most gratifying response, many papers reprinting the articles in full. By this means a very large addition is made to the number of our readers.”(Letter from MacGillivray to MacKay 1913, p. 2).

According to the Society’s internal records, The Chinese Weekly published twenty-two articles between April and May 1913: “Twenty-two articles were sent out during April and May and we have traced a total of 68 reprints. This does not count reprints in the Christian Daily of Hongkong or the various missionary papers which have also used very many of the articles” (Letter from MacGillivray to MacKay 1914, p. 2). These figures attest to the remarkable success of the reprint-for-gift policy, which transformed The Chinese Weekly into a “shared corpus of knowledge” among its readership. By 1914, under MacGillivray’s leadership, the C.L.S.C.’s periodicals had achieved nationwide circulation and once again captured the attention of China’s social elites. As MacGillivray proudly noted, “We are touching very much leaders hitherto unreached by ordinary means” (ibid., p. 3).

3.4. Commemorative Celebrations and Elite Networking

Grand commemorative ceremonies served as a key strategy through which the C.L.S.C. enhanced its social visibility and promoted its publications. Each December, the Society invited members of its Board of Directors and benefactors to attend its annual celebration, where it distributed yearbooks containing detailed sales data for its books and periodicals in order to attract new supporters. These gatherings also provided valuable opportunities for the Society to renew and strengthen its ties with officials of the Republican government.

In 1914, on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of The Chinese Weekly, Donald MacGillivray invited prominent Chinese statesmen to contribute congratulatory inscriptions, to which many responded enthusiastically. Yuan Shikai, then Provisional President of the Republic, praised The Chinese Weekly as “a precious book among a hundred nations” that should be “widely circulated, with a copy in every hand” (Yuan 1914, p. 1). Figure 5 presents the special commemorative section published in 1914 to mark the tenth anniversary of The Chinese Weekly, featuring congratulatory messages from leading Chinese officials—the first of which was written by President Yuan Shikai himself.

Figure 5.

Message from President Yuan (Yuan 1914, Source: [the National Index to Chinese Newspapers and Periodicals], an open-access resource. URL: https://webvpn.qdu.edu.cn/https/77726476706e69737468656265737421e7e056d2243e6a5b6d11c7af9758/search/detail/b0668e14e363304fd8f4faba53e7fdd9/7/692846c900439e53791cdbff (accessed on 25 November 2025)).

Vice President Li Yuanhong (黎元洪) lauded the newspaper’s achievements in his congratulatory message:

“A grand compilation, splendid and luminous,

Reporting world affairs and conveying the wisdom of sages,

Bringing enlightenment to our students,

As the fine rain and European winds ever renew themselves.

Through ten cycles of years, its mission endures”.(Li 1914, p. 2)

Duan Qirui (段祺瑞), Minister of War, compared The Chinese Weekly to The Times of London, asserting that “its value surpasses that of all other newspapers” (Duan 1914, p. 3). In addition, Sun Baoqi (孙宝琦), Minister of Foreign Affairs, and Liang Qichao, Minister of Justice, also contributed congratulatory remarks for the paper’s tenth anniversary. These responses vividly demonstrate the significant influence and prestige that The Chinese Weekly had achieved within Republican official and intellectual circles.

In essence, media commemorations functioned as cultural communication rituals through which the C.L.S.C. actively participated in shaping social practice. As the American scholar James W. Carey observed, “In a ritual view, communication is not merely the transmission of information but the sacred ceremony that draws people together in shared community” (Carey 2005, p. 4). The participation of Chinese officials in the tenth-anniversary celebration of The Chinese Weekly stemmed from their shared identity as readers of the newspaper. The willingness of high-ranking officials to send congratulatory messages was closely related to the C.L.S.C.’s long-standing practice of official consignment. To a considerable extent, the act of “reading the world” embodied both a performance and a negotiation of power, while the establishment of such interactive networks was grounded in mutual benefit among the participants.

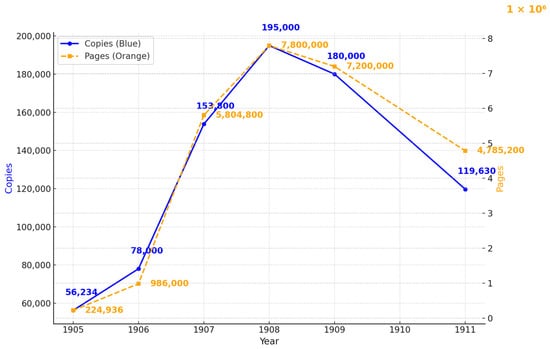

With the expansion of diversified distribution channels, the circulation of The Chinese Weekly rose substantially. Drawing on archival records from the C.L.S.C.’s annual reports, the newspaper’s circulation data are summarized as follows:

Drawing on the annual reports of the C.L.S.C., Figure 6 illustrates the circulation growth of The Chinese Weekly between 1905 and 1911. The blue line represents the number of copies distributed, while the orange dashed line indicates the total number of pages printed. The data reveal a notable surge in circulation during 1907–1908, reflecting the success of the newspaper’s expansion through official consignment and multi-channel distribution. As shown in the table above, The Chinese Weekly experienced a sharp rise in circulation after 1907, when it began publishing official portraits and implemented the official consignment system. However, by 1911, the outbreak of the Xinhai Revolution severed the newspaper’s connection to the Qing government’s patronage and financial support, resulting in a significant decline in sales. In 1913, under Donald MacGillivray’s direction of the C.L.S.C. News Bureau, The Chinese Weekly once again attracted public attention through the dual strategies of the reprint-for-gift policy and elite networking fostered by commemorative celebrations. Nevertheless, after the paper was reorganized as a monthly edition, its circulation stabilized at approximately 8500 copies—far below the prosperity of its earlier years.

Figure 6.

Circulation of The Chinese Weekly, 1905–1911. (Source: Authors)

The Chinese Weekly fulfilled a crucial role as a medium of knowledge and an integral component of the C.L.S.C.’s efforts to construct a shared reading community. During the late Qing period, missionaries used the newspaper as an intermediary to build interactive networks with Chinese officials, seeking to transform them into local agents for the Society’s publications. This practice, in turn, objectively facilitated the dissemination of modern newspapers among the bureaucratic elite. Conversely, Chinese officials’ cooperation with the C.L.S.C. was motivated by their own pursuit of social prestige and symbolic capital, leading both sides to converge upon the shared goal of promoting the press.

In the early Republican period, Donald MacGillivray’s establishment of the News Bureau and the introduction of the reprint-for-gift policy further expanded the reach of the C.L.S.C.’s periodicals. Commemorative celebrations likewise offered renewed opportunities for the Society to reestablish ties with officials of the new regime. In sum, the intersection of Western knowledge systems and mutual interests among diverse social groups transformed the dissemination of Western learning into a dynamic enterprise within China’s emerging modern cultural market.

Drawing on Christopher A. Reed’s conception of Shanghai as the cradle of “print capitalism,” The Chinese Weekly can be seen as a bridge between missionary print culture and the emerging modern reading public. As Reed notes, the rise of print capitalism was characterized by institutionalized reading habits and a nationwide market for print (Reed 2004, pp. 6–8, 279–81). Within this transformation, the C.L.S.C.—the largest Christian publishing institution of the time—played a crucial role. Its flagship periodical, The Chinese Weekly, targeted the educated elite, shaping habits of reading, discussion, and knowledge exchange. In doing so, it anticipated the formation of China’s modern reading culture and embedded missionary publishing within the broader project of cultural modernization.

4. “The Chinese Times”: Reading Experience and Hermeneutic Practice Among Chinese Intellectuals

Since the emergence of modern print media in China, one of the most pressing questions has been how to attract and sustain readers’ engagement. The ideal of “encouraging the people to read newspapers” was a shared aspiration among late Qing journalists. For any periodical, its ability to enter and shape the intellectual world of its readers was a key measure of its communicative success. From the late Qing onward, members of the literati increasingly turned to Western newspapers to stay informed about world affairs and to expand their intellectual horizons. Missionaries, seizing upon this growing curiosity, undertook printing and publishing activities that disseminated new forms of knowledge while simultaneously advancing their evangelical mission. The C.L.S.C. and similar missionary publishing organizations initially aimed to propagate the Gospel, yet in practice, they also offered Chinese intellectuals an important window through which to access and interpret global knowledge.

At first, the circulation of the C.L.S.C.’s newspapers was largely concentrated in Shanghai and several provincial capitals, making it difficult for readers in rural regions to obtain copies. The introduction of the official consignment system significantly extended the distribution of The Chinese Weekly to provincial and prefectural levels. The C.L.S.C. openly acknowledged that the newspaper enjoyed little competitive advantage within Shanghai itself; however, through diversified promotional channels, it successfully penetrated the inland market:

“Shanghai being so well supplied by native dailies, there is very little local circulation for a weekly paper of its class, but its inland circulation seems to be larger than the inland circulation of any Shanghai daily.”(The Eighteenth Annual Report of the Christian Literature Society for China, for the Year Ending September 30th, 1904–1905 [Shanghai: Christian Literature Society for China], Box 79.190C, 3 of 3, 1905, p. 17).

With the active endorsement of provincial governors and viceroys, numerous local officials soon became familiar with—and subscribed to—The Chinese Weekly. This development played a vital role in cultivating a localized readership at the prefectural and county levels for the C.L.S.C.’s publications.

Based on correspondence from officials who responded to portrait invitations and commemorative inscriptions for the tenth anniversary of The Chinese Weekly, Table 1 below summarizes the reading experiences of Chinese officials with the newspaper.

Table 1.

The Reading Experience of Chinese Officials toward The Chinese Weekly, 1905–1911.

This table compiles letters from officials across multiple provinces—including Jiangsu, Shandong, Shanxi, Shaanxi, Jilin, Heilongjiang, Fujian, Guangdong, Guizhou, Hunan, Yunnan, and Guangxi—clearly demonstrating that The Chinese Weekly was highly esteemed among government officials and widely circulated among provincial governors and bureaucrats. According to contemporary records, “The Chinese Weekly (Ta Tung Pao) was having almost fantastic sales. They quadrupled in a few months. The Governor of Manchuria placed an order for 200 copies weekly. Kwangtung’s Treasurer subscribed for 300; the Fukien Treasurer paid for 400, while the Governor of Shansi subscribed for 500 and the Shantung man 900. But the biggest surprise was a telegram from the Governor of the far-western province of Sinkiang ordering 900 copies” (Brown 1968, p. 96). Zhang Yintang (张荫棠), High Commissioner in Tibet, likewise requested that the Western Branch of the C.L.S.C. send him The Chinese Weekly regularly, even planning to establish a daily newspaper in Lhasa (The Twentieth Annual Report of the Christian Literature Society for China, for the Year Ending September 30th, 1906–1907 [Shanghai: Christian Literature Society for China], Box 79.190C, 3 of 3, 1907, p. 9).

It should be noted, however, that not all official subscriptions were entirely voluntary; some were motivated by bureaucratic obligation. As Lian Jia (连甲), the former Provincial Treasurer of Fujian, remarked: “Considering the current conditions in Fujian, it may be possible to distribute three or four hundred copies on behalf of the Society, but if the required quota must be met in full, I fear it will be impossible to comply” (Lian 1907, p. 1).

The years 1905–1911, highlighted in the accompanying table, represent the zenith of The Chinese Weekly’s circulation and influence. This period coincided with the late Qing “New Policies” reforms, when provincial bureaucrats became increasingly engaged in projects of modernization and governance reform. Their large-scale institutional subscriptions not only extended the newspaper’s reach into administrative networks but also transformed it into a semi-official channel for knowledge circulation. The widespread bureaucratic participation during these years thus illustrates the central argument of this article: that The Chinese Weekly functioned not merely as a missionary publication but as a medium through which Western knowledge was absorbed, adapted, and recontextualized within China’s own bureaucratic and intellectual systems.

The subscription behavior of government officials exerted a certain guiding influence on the local populace. In 1905, eight gentry members from Yichang jointly subscribed to The Chinese Weekly for a full year. Dong Yingchan (董影禅), president of the Danyang Chamber of Commerce, was among its loyal readers: “Since the publication of your esteemed newspaper, I have shared a subscription with friends” (Dong 1908, p. 1). In 1908, Dai Shiduo (戴师铎) and Jue Minfu (觉民甫) published a reflection on their reading experience: “Its content—covering constitutional government, finance, education, transportation, mining, and public health—introduces, one by one, the very systems that have proven effective in Europe and America. If our country could compose such works, and our people could draw upon these models for inspiration, how could we not, through collective effort, swiftly rise to prosperity?” (Dai and Jue 1908, p. 3).

Moreover, many missionaries stationed in remote rural towns also circulated the paper among themselves. The C.L.S.C. once received a letter from a missionary stating: “By its aid, I have gained friendly intercourse with one or two of the leading families of this city. We all look for the Chinese Weekly with eagerness, and devour its well-edited contents as soon as it arrives” (The Eighteenth Annual Report of the Christian Literature Society for China, for the Year Ending September 30th, 1904–1905 [Shanghai: Christian Literature Society for China], Box 79.190C, 3 of 3, 1905, p. 17).

Purchasing newspapers in the countryside was not easy, as readers had to weigh both the subscription cost and postage fees. Consequently, a single copy of The Chinese Weekly was often circulated from reader to reader in rural areas until it became worn out. As one missionary observed, “The number of its issues by no means represents the extent of its influence” (ibid., p. 18).

The Chinese Weekly consistently emphasized its “sole mission to safeguard peace in East Asia and to support China in her weakness,” a position that, to a certain extent, reflected a missionary strategy veiled beneath the rhetoric of Christian civilizational superiority (The Chinese Weekly 1914, p. 8). While introducing Western knowledge to construct an authoritative discourse of modernity, the newspaper systematically embedded religious logic within its texts. Donald MacGillivray attributed the medical achievements of ancient Chinese physicians such as Hua Tuo (华佗) and Bian Que (扁鹊) to divine grace, asserting that they “bear witness to God’s love for humankind” (MacGillivray 1914, p. 36). Margaret H. Brown (薄玉珍), who chaired the C.L.S.C. Publishing Committee, stated even more explicitly that the publication’s purpose was to articulate “the Christian view of the various forces now shaping the world” (Brown and He 1948, p. 5). This strategy of “sacralizing knowledge” effectively transformed scientific progress into theological proof, while simultaneously eroding the intrinsic value of Chinese culture. In essence, it advanced a subtle form of cultural colonization—seeking to supplant China’s indigenous moral order with the value system of Christian civilization.

In seeking to employ Western knowledge as a tool to open China’s traditional belief structures, The Chinese Weekly revealed the intrinsic dilemma faced by foreign religious civilization in the context of China’s modernization. Chinese intellectuals and readers possessed strong cultural subjectivity: they selectively disseminated and interpreted the newspaper’s content rather than passively accepting missionary intentions. Reflecting on the challenges of “newspaper evangelism” in 1917, Donald MacGillivray wrote:

“Eight persons were asked to write eight articles for the special effort. They were all well-known persons, but the result is not very satisfactory. Some of them were not able to produce an article suitable for the newspapers as they never did so before. Two failed and asked somebody else to write for them, and finally two articles had to be supplied by our own office. The articles as a whole have not as much of the Gospel in them as I would like, the writers fearing that too much plainness of speech would offend the readers”.(Letter from MacGillivray to MacKay 1917, p. 1)

This account vividly illustrates that Chinese intellectuals maintained their own interpretive frameworks and belief systems; they were neither easily transformed nor ideologically molded by missionary discourse. In the process of transplanting foreign knowledge, the discursive authority of The Chinese Weekly inevitably encountered the filtration and reconstruction of China’s indigenous cultural networks. Although the paper sought to subtly promote Christianity through its articles, its evangelistic influence remained limited. Paradoxically, the Western scientific knowledge originally intended for evangelization became widely disseminated, resonating with China’s reformist aspirations amid internal crises and external pressures.

Beyond its religious mission, The Chinese Weekly also offered a multifaceted model for the enlightenment of modern Chinese journalism and contributed to the modernization of China’s press industry. During the late Qing period, influential newspapers such as the Sichuan Mandarin Gazette, the Official Gazette of Qinzhong 《秦中官报》, the Sichuan Educational Gazette 《四川教育官报》, and the Gazette of the Preparatory Constitutional Association 《预备立宪公会报》 frequently reprinted The Chinese Weekly’s most recent essays on education, agriculture, and finance—testifying to its far-reaching impact on China’s intellectual and journalistic transformation.

Despite its wide circulation, however, The Chinese Weekly struggled financially. According to the C.L.S.C.’s 1916 annual report, the newspaper’s total income for that year was $910.14, while total expenditures reached $1052.05, resulting in a deficit of $141.91 (The Twenty-Ninth Annual Report of the Christian Literature Society for China, for the Year Ending September 30th, 1915–1916 [Shanghai: The Christian Literature Society for China], Box 79.190C, 3 of 3, 1916, p. 24). MacGillivray attributed the losses primarily to the fact that “we are unable to include our address in the articles and therefore cannot correspond with inquirers,” which prevented readers from providing direct financial support to the paper (MacGillivray 1915, p. 596). To address this, he proposed improving editorial quality and expanding channels of communication and outreach, though these measures yielded little success. In 1917, The Chinese Weekly ceased publication after issuing a total of 575 numbers. Its discontinuation symbolized the near-complete withdrawal of the C.L.S.C. from the forefront of political reform and intellectual debate in early twentieth-century China.

5. Conclusions

As a distinctive missionary publication, The Chinese Weekly reflected both the dissemination and transformation of modern knowledge in late Qing and early Republican China. Through its systematic introduction of Western science, education, and social thought, it mediated the encounter between missionary enterprise and China’s reformist agenda. By establishing an official consignment system, the C.L.S.C. integrated its newspaper into the bureaucratic reading routines of Chinese officials, thereby pioneering an institutionalized model of reading among missionary publications in modern China and fostering the habit that “Western newspapers must be read.” This practice not only expanded the reach of missionary journalism but also embedded Western learning within the routines of administrative correspondence and local governance.

From the perspective of circulation, the active participation of provincial officials in distributing and reading The Chinese Weekly revealed the newspaper’s dual function as both an evangelical medium and an instrument of bureaucratic communication. For many officials, engagement with the paper provided symbolic capital and social prestige; for the C.L.S.C., it offered channels through which its periodicals could penetrate official networks. This mutually beneficial relationship fostered an interactive pattern between knowledge and power, highlighting how Western information entered Chinese officialdom not merely as ideology but as practical knowledge serving governance and reform.

From the perspective of reading experience, Chinese intellectuals and officials did not simply absorb missionary discourse. Instead, they interpreted, selected, and adapted the knowledge disseminated through The Chinese Weekly according to their own intellectual traditions and pragmatic concerns. The newspaper’s content—ranging from astronomy and agriculture to education and medicine—became a medium through which Western learning was localized and redefined. In this process, The Chinese Weekly inadvertently facilitated China’s intellectual modernization, transforming a missionary endeavor into a platform for rational inquiry and reformist reflection.

By situating The Chinese Weekly within the broader landscape of missionary publishing and China’s evolving print culture, this study reveals that the encounter between foreign evangelism and indigenous readership was not a one-way process of influence, but a dynamic negotiation shaped by local agency and intellectual selectivity. Rather than constituting a fixed system of “epistemic governance,” it was through these negotiations—between editors and readers, missionaries and officials—that modern Chinese knowledge communities gradually emerged. Positioned at the intersection of missionary enterprise, bureaucratic participation, and knowledge circulation, The Chinese Weekly exemplifies how cross-cultural interaction reconfigured the contours of modern Chinese print culture and helped redefine the intellectual foundations of China’s path toward modernization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.S. and S.T.; methodology, S.T.; software, Y.S.; validation, S.T.; formal analysis, S.T.; investigation, Y.S.; resources, Y.S.; data curation, Y.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.S.; writing—review and editing, Y.S. and S.T.; visualization, Y.S.; supervision, S.T.; project administration, Y.S.; funding acquisition, Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Fund of China, grant number 24CZS078. The APC was funded by the 2024 National Social Science Fund of China, Youth Project “A Study on European Publishers and the Overseas Dissemination of Chinese Classics after the Opium War (1840–1945)”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the three anonymous reviewers, whose critical feedback and expertise helped this article to flourish. We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the staff of the National Index to Chinese Newspapers and Periodicals, the Shanghai Municipal Archives, the United Church of Canada Archives, and the East China Theological Seminary Library for their valuable assistance during our data collection process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary of Names

| Aisin Gioro Shanqi 爱新觉罗·善耆 (1866–1922) was a noble statesman of the late Qing dynasty and one of the twelve “Iron-Cap Princes” of the Qing imperial clan. He was among the founders of China’s modern police system and played a key role in promoting municipal development in Beijing. |

| Bian Que 扁鹊 (c. 407–310 BCE) was a famed Warring States physician who created the four diagnostic methods and is honored as the founder of pulse diagnosis. |

| Cao Hongxun 曹鸿勋 (1846–1910) was a late Qing zhuangyuan, official, and calligrapher. Serving as Governor of Shaanxi, he oversaw the drilling of China’s first onshore oil well, pioneering the modern petroleum industry. |

| Da Gui 达桂 (1860–1926), courtesy name Xinshan, a Han Plain Yellow Banner official, served as Governor-General of Heilongjiang and Jilin. He founded the Guangxin Company, advanced land reclamation, reformed the banner system, and was dismissed in 1907, later residing in Tianjin. |

| Di Renjie 狄仁杰 (630–700), courtesy name Huaiying, was a Wu Zhou statesman famed for his integrity and discernment. He advised Empress Wu Zetian 武则天 to reinstate Li Xian 李显 as crown prince, securing the Tang dynasty’s succession. |

| Duan Qirui 段祺瑞 (1865–1936) was leader of the Anhui Clique and one of the Three Beiyang Leaders. He served as Premier and Acting President, suppressed Zhang Xun’s Restoration, resigned after the March 18 Massacre, and later refused to collaborate with Japan. |

| Hua Tuo 华佗 (c. 145–208) was a famed Eastern Han physician from Bozhou, Anhui. He invented “Mafeisan,” created the Five-Animal Exercises, and is revered as the founder of Chinese surgery. |

| Kang Youwei 康有为 (1858–1927) was an important Chinese statesman, thinker, and educator active from the late Qing dynasty to the early Republic of China. A leading representative of bourgeois reformism, he is best known for initiating the Petition of the Scholars and assisting Emperor Guangxu in carrying out the Hundred Days’ Reform. |

| Li Yuanhong 黎元洪 (1864–1928), courtesy name Songqing, from Huangpi, Hubei, became military governor after the Wuchang Uprising and twice served as president of the Republic of China. He joined the Cabinet–Presidency Conflict and later engaged in industry. |

| Liang Qichao 梁启超 (1873–1929), a native of Xinhui County, Guangdong Province, was a prominent bourgeois politician and thinker in modern China. He was one of the leaders of the Hundred Days’ Reform in the late Qing dynasty and the founder of several political parties during the Republic of China. |

| MacGillivray, Donald 季理斐 (1862–1930) was a Canadian missionary, publisher, and philanthropist active in China. As the fourth General Secretary of the C.L.S.C., he was dedicated to spreading Christianity and modern knowledge through publishing and charitable relief work. |

| Morgan, Evan 莫安仁 (1860–1941) was a British Baptist missionary who served in China. Renowned for his work in Chinese language teaching, linguistic studies, and lexicography, he was a prominent editor at the C.L.S.C. in Shanghai and helped launch the Chinese Weekly. |

| Pang Hongshu 庞鸿书 (1848–1915) served as Judicial Commissioner of Hunan and Governor of Guizhou. He founded the Hunan Library, China’s first provincial public library, and promoted reforms, education, and industry before his dismissal. |

| Sima Xiangru 司马相如 (c. 179–118 BCE) was the foremost of the Four Great Masters of Han Rhapsody. He also served as envoy to the Southwestern Tribes, promoting ethnic and cultural exchange, and is celebrated for his romantic story with Zhuo Wenjun. |

| Sun Baoqi 孙宝琦 (1867–1931), from Qiantang, Zhejiang, was a late Qing and early Republican statesman and diplomat. He served as Premier, promoted constitutional reform and ties with the Soviet Union, resigned over the Franc Loan Incident, and later engaged in philanthropy and industry. |

| Wang Renwen 王人文 (1863–1939) was acting Governor-General of Sichuan during the 1911 Railway Protection Movement. He opposed Sheng Xuanhuai 盛宣怀, later served as a senator in the Republic, and was hailed as one of the Eight Meritorious Figures of the Sichuan Revolution. |

| Wu Tingbin 吴廷斌 (1839–1914) was a late Qing official from Jing County, Anhui. As Governor of Shanxi and Shandong, he promoted Shandong’s economic modernization and established the Bureau of Industry Promotion in 1908. |

| Xiong Xiling 熊希龄 (1869–1937), from Fenghuang, Hunan, was a late Qing and early Republican statesman and philanthropist. He served as Premier, founded the Xiangshan Children’s Home in 1920, and was hailed as the pioneer of China’s child welfare. |

| Yang Shixiang 杨士骧 (1860–1909), a native of Sixian, Anhui, was a late Qing official who served as Governor of Shandong and Viceroy of Zhili. He advanced education, foreign affairs, and water conservancy. |

| Yuan Shikai 袁世凯 (1859–1916) was a military leader from Xiangcheng, Henan Province. He was a prominent political and military figure in modern Chinese history and the leader of the Beiyang warlords. |

| Zhou Fu 周馥 (1837–1921), courtesy name Yushan, was a statesman and military figure from Jiande, Anhui. Active from the late Qing to the early Republic, he was a key promoter of the Self-Strengthening Movement, achieving distinction in river management, education, industry, and military modernization. |

| Zhu Baosan 朱葆三 (1848–1926) was a leader of the Ningbo Group, an industrialist, and a philanthropist. Rising from a hardware apprentice, he founded the China Commercial Bank and many enterprises, later serving as Shanghai’s Finance Minister and Chamber of Commerce President. |

Notes

| 1 | The Chinese Progress was a comprehensive semi-monthly journal founded during the Reform Movement. It was first published in Shanghai on 9 August 1896, by Huang Zunxian, Wang Kangnian, and Liang Qichao. Using lithographic printing on continuous-history paper, it was the first privately operated magazine in China. |

| 2 | Guanzi is a compilation attributed to Guan Zhong, formed by scholars of the Jixia Academy. Integrating Daoist, Legalist, Confucian, and Yin-Yang ideas, it presents an eclectic system of statecraft. |

| 3 | It means that even galloping horses or running cattle would not cross into each other’s territory, describing a vast distance or great expanse. It is also used metaphorically to indicate things that are completely unrelated. |

| 4 | Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 in this manuscript are all sourced from The Chinese Weekly during the late Qing and Republican periods. The original materials are available through the National Index to Chinese Newspapers and Periodicals, an online database developed and maintained by the Shanghai Library. After purchasing institutional or personal access, users may download these archival materials freely. All images used here originate from this open-access, publicly available. |

References

Primary Sources