Science Translation in Late Qing Christian Periodicals and the Disciplinary Transformation of Chinese Lixue

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Historical Development of Lixue

2.1. Pre-Qin “Lixue”

2.2. Lixue from the Tang to Qing Dynasties

2.3. “Japanese Wave” in Introduction of Western Science

2.4. Late Qing Missionaries’ Introduction of Western Science

3. Late Qing Christian Periodicals’ Translation and Introduction of Western Scientific Knowledge

3.1. A Representative Christian Periodical Case Study: Young John Allen’s the Church News

3.2. The Semantic Evolution of “Gezhi” and Its Impact on Traditional Neo-Confucianism Concepts: Gezhi and Lixue

3.2.1. The Deconstructive Role of Astronomy and Physics

3.2.2. The Positivist Impact of Biology and Chemistry

3.2.3. The Introduction of Scientific Classification Systems

4. Impact of Late Qing Christian Periodicals’ Translation of Western Scientific Knowledge

4.1. The Disciplinarization of Natural Sciences

4.2. Modernization of Attitudes

4.3. Modernization of Education

4.4. Limitations of the Christian Periodicals

4.4.1. Thesis

4.4.2. Antithesis

4.4.3. Synthesis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | According to Xu Shen 许慎’s Shuowen Jiezi 说文解字 (Explaining Graphs and Analyzing Characters), “Li” (理) means “to work jade” (Zhiyu 治玉) that is, to process jade stone. Its character structure is left-right compositional, consisting of two parts: “Jade” (Yu玉) and “Li”. Character structure: the semantic component is “Jade” (Yu玉), the phonetic component is “Li” (里) Here, “Jade” (Yu玉) as the semantic radical indicates relation to jade stone; “Li” (里) as the phonetic component indicates pronunciation. The original meaning of “Li” is to process jade stone—specifically, to split jade along its natural grain patterns to make it into useful implements. Zhanguo Ce 战国策 (The Strategies of the Warring States ) mentions: “The people of Zheng call unworked jade ‘pu’ (璞)”, where “Li” (理) refers to the processing of jade. “Li” extends to mean governance and management, such as governing a state or managing finances. It further extends to mean the patterns or principles of things, as in “Heavenly Principle” (Tianli 天理), referring to natural laws. Other extended meanings include to arrange, to heal, to appeal, to distinguish, etc. Through Xu Shen’s explanation of the character “Li”, we can see how it developed from its original meaning of processing jade into rich and diverse connotations, encompassing governance, principle, and pattern across multiple dimensions. |

| 2 | The Review of the Times was originally named The Church News, founded in Shanghai in September 1868, with American missionary Young John Allen as editor-in-chief. Its initial founding mission was “spreading the gospel” and “connecting believers.” In 1874, The Church News was renamed The Global Magazine, transforming from a purely religious publication into a comprehensive periodical disseminating science, technology, and current affairs. It ceased publication in 1883. In February 1889, The Review of the Times resumed as a monthly publication. It finally ceased publication in July 1907. |

| 3 | From 1868 to 1874, The Church News primarily disseminated religious information with minimal scientific and cultural content. From 1874 to 1894, The Global Magazine extensively translated and disseminated scientific and technological knowledge. In 1894, the First Sino-Japanese War erupted, and China’s defeat led to nationwide doubts about learning Western science and technology. Moreover, with the rise of the Boxer Rebellion in 1899, missionaries in China faced difficult circumstances amid social turmoil—a critical juncture of national peril. Consequently, The Review of the Times heavily reported current affairs with almost no scientific translation or dissemination. This situation persisted until 1900. In 1901, The Review of the Times resumed extensive translation and dissemination of scientific knowledge. |

| 4 | Yang Zi 杨子, an ancient Chinese philosopher, also known as Yang Zhu 杨朱, was an important thinker during the Warring States period and one of the representatives of the Daoist school. His core philosophical ideas included: 1. “For the self” (Weiwo 为我) and “Valuing the self” (Guiji 贵己): He advocated for the supremacy of individual life, opposing both Confucian ideals of loyalty, filial piety, benevolence, and righteousness, as well as the Mohist doctrine of “universal love” (Jianai 兼爱). He believed that one should not sacrifice self-interest for any external purpose, even proposing that he “would not pluck a single hair to benefit the entire world” (Bayimao Er Litianxia, Buweiye 拔一毛而利天下, 不为也). 2. “Valuing life lightly over material things“ (Qingwu Zhong sheng 轻物重生): He emphasized preserving the authenticity of life, avoiding the constraints that external objects impose on body and mind, and pursuing freedom and happiness in a natural state. 3. Philosophical influence: His doctrine formed a sharp contrast with Confucianism and Mohism. Mencius vehemently criticized his “egoism” (Liji Zhuyi 利己主义). |

References

- Allen, Young John 林乐知. 1874. Ji Shanghai Gezhi Shuyuan. 记上海创设格致书院 [Record of Establishing the Shanghai Polytechnic Institute]. [The Church News] 万国公报 306: 27–28. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Young John 林乐知. 1875. Daqingguo: Lun Xixue Sheke 大清国:论西学设科 [The Great Qing Empire: On Establishing Western Learning Subjects]. [The Church News] 万国公报 325: 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Young John 林乐知, and Erkang Cai 蔡尔康. 1896. Wenxue Xingguo Ce Xu 文学兴国策序. [The Church News] 万国公报 88: 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Young John 林乐知, and Yi Van 范祎. 1904. Mingyao Yuanliu 名药源流 [The Origins of Famous Medicines]. [The Church News] 万国公报 190: 53–54. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Young John 林乐知, and Yi Van 范祎. 1905. Celiang Shenhai 测量深海 [Measuring the Deep Sea]. [The Church News ] 万国公报 201: 56. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Ge 白鸽, and Min Du 杜敏. 2012. Jindai Xifang Laihua Chuanjiaoshi Yijie Huodong Ji Qi Dui Yuyan Biange de Yingxiang 近代西方来华传教士译介活动及其对语言变革的影响 [Translation and Introduction Activities of Modern Western Missionaries in China and Their Impact on Language Reform]. XiBei Daxue Xuebao (Zhexue Shehui Kexueban) 西北大学学报 (哲学社会科学版) [Journal of Northwest University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition)] 5: 164–67. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Li 成瓅. 2014. Jindai Laihua Chuanjiaoshi “Zhongguo Hua” Celue Xia de Jidujiao Yishu 近代来华传教士”中国化” 策略下的基督教艺术 [Christian Art under the “Sinicization” Strategy of Modern Missionaries in China]. Zongjiao Xue Yanjiu 宗教学研究 [Religious Studies] 3: 205–12. [Google Scholar]

- Eber, Irene. 2024. Bible in Modern China: The Literary and Intellectual Impact. Germany: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Elman, Benjamin A. 2005. On Their Own Terms: Science in China, 1550–1900. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fairbank, John King. 1985. Early Protestant Missionary Writings. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Tianyu 冯天瑜, and Changshun Nie 聂长顺. 2019. “Kexue” Cong Gudianyi Dao Xiandaiyi De Yanyi “科学” 从古典义到现代义的演绎 The Interpretation of “Science” from Classical Meaning to Modern Meaning. Wuhan Daxue Xuebao (Zhexue Shehui Kexueban) 武汉大学学报(哲学社会科学版) [Wuhan University Journal (Philosophy & Social Science)] 4: 111–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Jun 龚隽. 2024. Jin Dai Jinwen Jingxue Yu Foxue Zhijiaoshe: Yi Kangyouwei Liangqichao Wei Zhongxin 近代今文经学与佛学之交涉:以康有为、梁启超为中心 [On Negotiations between the Modern Script School and Buddhism: Centered on Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao]. Shijie Zongjiao Yanjiu 世界宗教研究 [Studies in World Religions] 8: 10–21. [Google Scholar]

- He, Jingjing 何晶晶. 2023. 19 Shiji Laihua Chuanjiaoshi de Zhong-Xi Yuyan Bijiao—Yi Chuanjiaoshi Zaihua Suoban Yingwen Baokan “Zhongguo Congbao” Weili 19世纪来华传教士的中西语言比较--以传教士在华所办英文报刊《中国丛报》为例 [A Comparison of Chinese and Western Languages by 19th Century Missionaries in China: A Case Study of the English-Language Periodical Chinese Repository Published by Missionaries in China]. Hanzi Wenhua 汉字文化 [Sinogram Culture] S1: 55–56. [Google Scholar]

- Latourette, Kenneth Scott. 1929. A History of Christian Mission in China. New York: The MacMillian Company. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Qichao 梁启超. 1902. Gezhixue Yange Kaolve格致學沿革考略 [A Brief History of Science]. Xinmin Congbao 新民丛报 [Xinmin Congbao] 10: 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Kwang-Ching. 1966. American Missionaries in China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Lydia H. 1995. Translingual Practice: Literature, National Culture, and Translated Modernity-China, 1900–1937. California: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Macklin, William Edward 马林, and Yushu Li 李玉书. 1901. Peigen Xinxue Gezhi Lun 培根新学格致论 [Bacon’s New Learning on Natural Philosophy]. [The Church News] 万国公报 151: 24–36. [Google Scholar]

- Macklin, William Edward 马林, and Yushu Li 李玉书. 1903. Gezhi Jinhua Lun 格致进化论 [The Theory of Evolution in Gezhi Studies]. [The Church News] 万国公报 169: 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Masini, Federico. 1993. The Formation of Modern Chinese Lexicon and its Evolution toward a National Language: The Period from 1840 to 1898. Journal of Chinese Linguistics Monograph Series 6: i-295. [Google Scholar]

- Muirhead, William 慕维廉. 1892. Gezhi Xinxue 格致新學 [New Learning in Science]. [The Church News] 万国公报 46: 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, Douglas R. 1993. China, 1898–1912: The Xinzheng Revolution and Japan. Brill: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sanetō, Keishū. 1960. Chūgokujin Nihon ryūgakushi 中國人日本留學史. Tokyo: Kuroshio Shuppan. [Google Scholar]

- Shenbao. 1902. 大学程材 [University Curriculum Standards]. 申报 Shunpao. October 21, p. 1. Available online: https://www.bksy.ns.sjuku.top/search/advance (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- State Council Academic Degrees Committee & Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. 2018. Xuewei Shouyu He Rencai Peiyang Mulu学位授予和人才培养学科目录 Academic Degrees Granted and Talent Training Disciplines Catalog. Beijing: Guowuyuan Xuewei Weiyuanhui he Jiaoyubu 国务院学位委员会和教育部 State Council Academic Degrees Committee & Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Yang 孙杨. 2007. Wanqing Zaihua Chuanjiaoshi de Jingji Xingwei 晚清在华传教士的经济行为 [The Economic Activities of Missionaries in China during the Late Qing Dynasty]. Shi Ji Qiao 世纪桥 [Bridge of Century] 1: 86–90. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Bingkun 王炳堃. 1907. Waigao: Erjiao Zhiguo Gongyi Duogua 外稿:二教之国公益多寡 [The Situation of Public Welfare in Countries with Two Religions]. [The Church News] 万国公报 224: 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Guowei 王国维. 1906. Shangbian Zhengshi Men: Cuilun: Zouding Jingxueke Daxue Wenke Daxue Zhangcheng Shuhou上编政事门: 粹论: 奏定经学科大学文学科大学章程书后 [Upper Section, Political Affairs Division: Selected Essays: Postscript to the Memorial on the Regulations for Colleges of Classical Studies and Liberal Arts]. [Guangyi Congbao] 广益丛报 120: 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Jiadi 王佳娣. 2014. Houzhimin Yi Lun Xia de Ming Qing Laihua Chuanjiaoshi Fanyi Celue Yanjiu后殖民译论下的明清来华传教士翻译策略研究 [A Study on the Translation Strategies of Missionaries in the Ming and Qing Dynasties from the Perspective of Postcolonial Translation Theory]. Changjiang Daxue Xueba (Shehui Kexue Ban) 长江大学学报(社会科学版) [Journal of Yangtze University (Social Sciences Edition)] 10: 108–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Lixin 王立新. 1997. Meiguo Chuanjiaoshi Yu Wanqing Zhongguo Xiandaihua 美国传教士与晚清中国现代化 [American Missionaries And Modernization Of China in the Late Qing Dynasty]. Tianjin: Tianjin People’s Publishing House 天津人民出版社, pp. 158–65. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Yanfang 王艳芳. 2015. 19 Shiji Zhongye Zhi 20 Shiji Chu Laihua Xifang Renshi de Hanyu Xuexi Ji Qi Yingxiang 19世纪中叶至20世纪初来华西方人士的汉语学习及其影响 [Chinese Language Learning by Westerners in China from the Mid-19th to Early 20th Century and Its Impact]. Lantai Shijie 兰台世界 [Lantai World] 36: 174–75. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Yixiong 吴义雄. 2000. Zai Zongjiao Yu Shisu Zhijian: Jidujiao Xinjiao Chuanjiaoshi Zai Huanan Yanhai de Zaogi Huodong Yanjiu 在宗教与世俗之间: 基督教新教传教士在华南沿海的早期活动研究 [Between the Sacred and the Secular: A Study of the Early Activities of Protestant Missionaries along the South China Coast]. Fujian: Fujian Education Press 福建教育出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Wylie, Alexander. 1867. Memorials of Protestant Missionaries to the Chinese. Shanghai: American Presbyterian Mission 661 Press. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Zhihui 谢智慧, and Jixuan Shi 石济瑄. 2017. Xifang Laihua Chuanjiaoshi Li Madou Zaihua de Yuyan Shenghuo 西方来华传教士利玛窦在华的语言生活 [The Linguistic Life of Matteo Ricci, the Western Missionary to China]. Qingnian Wenxuejia 青年文学家 [Youth Literator] 15: 188–89. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Fangming 颜方明. 2014. Fanyi Zhong de Yiyu Jingdian Chonggou—Chuanjiaoshi Shengjing Hanyi de Jingdian Hua Celue Yanjiu 翻译中的异域经典重构-传教士《圣经》汉译的经典化策略研究 [Recanonization of foreign classics in translation: A Case study of thecanonization strategy of missionaries’ translating Bible into chinese]. Zhongnan Daxue Xuebao (Shehui Kexue Ban) 中南大学学报 (社会科学版) [Journal of Central South University (Social Sciences)] 4: 259–63. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Jie 杨洁, and Xinde Li 李新德. 2013. Qingmo Minchu Yingguo Chuanjiaoshi Yu Wenzhou Minsu de Pengzhuang He Shiying清末民初英国传教士与温州民俗的碰撞和适应 [The Conflicts and Adaption between the Missionaries and Wenzhou Folklore from Late Qing Dynasty to the Early Republic of China]. Wenzhou Daxue Xuebao (Shehui Kexue Ban) 温州大学学报 (社会科学版) [Journal of Wenzhou University(Social Science Edition)] 2: 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Wenjuan 尹文娟. 2005. Yesu Hushi yu Xinjiao Chuanjiaoshi Dui Jingbao de Jieyi 耶稣会士与新教传教士对《京报》的节译 Selected Translation of Peking Gazette by Jesuits and Protestant Missionarie. Shijie Zongjiao Yanjiu 世界宗教研究 [Studies in World Religions] 2: 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Xianqing 张先清. 1998. 1990–1996 Nianjian Mingqing Tianzhujiao Zaihua Chuanboshi Yanjiu Gaishu 1990–1996 年间明清天主教在华传播史研究概述 [A Review of the Study of the History of Catholicism in Ming and Qing China from 1990 to 1996]. Zhongguoshi Yanjiu Dongtai 中国史研究动态 [Trends of Recent Researches on the History of China] 6: 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Xiping 张西平. 2009. Qingdai Laihua Chuanjiaoshi Maruose Yanjiu 清代来华传教士马若瑟研究 [An Examination of Joseph de Prémare’s Scholarship and his Influence on European Sinology]. Qingshi Yanjiu 清史研究 [The Qing History Journal] 2: 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Hongjuan 赵洪娟. 2024. Zaoqi Meiguo Laihua Chuanjiaoshi de Zhongguo Minsu Guanzhu Ji Qi Yingxiang 早期美国来华传教士的中国民俗关注及其影响 [The Attention and Influence of Early American Missionaries on Chinese Folklore]. Jidujiao Zongjiao Yanjiu 基督宗教研究 [Study of Christianity] 1: 309–22. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Shiyu 周世愚. 2023. Wanqing Deguo Laihua Chuanjiaoshi Hua Zhi’an de Zongjiao Jingji Guan Jianshu 晚清德国来华传教士花之安的宗教经济观简述 [A Brief Account of the Religious Economic View of Ernst Faber, a German Missionary to China in the Late Qing Dynasty]. Shijie Zongjiao Wenhua 世界宗教文化 [The World Religious Cultures] 4: 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Xi 朱熹. 1983. Sishu Zhangju Jizhu 四书章句集注 [Collected Commentaries on the Four Books]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company 中华书局. [Google Scholar]

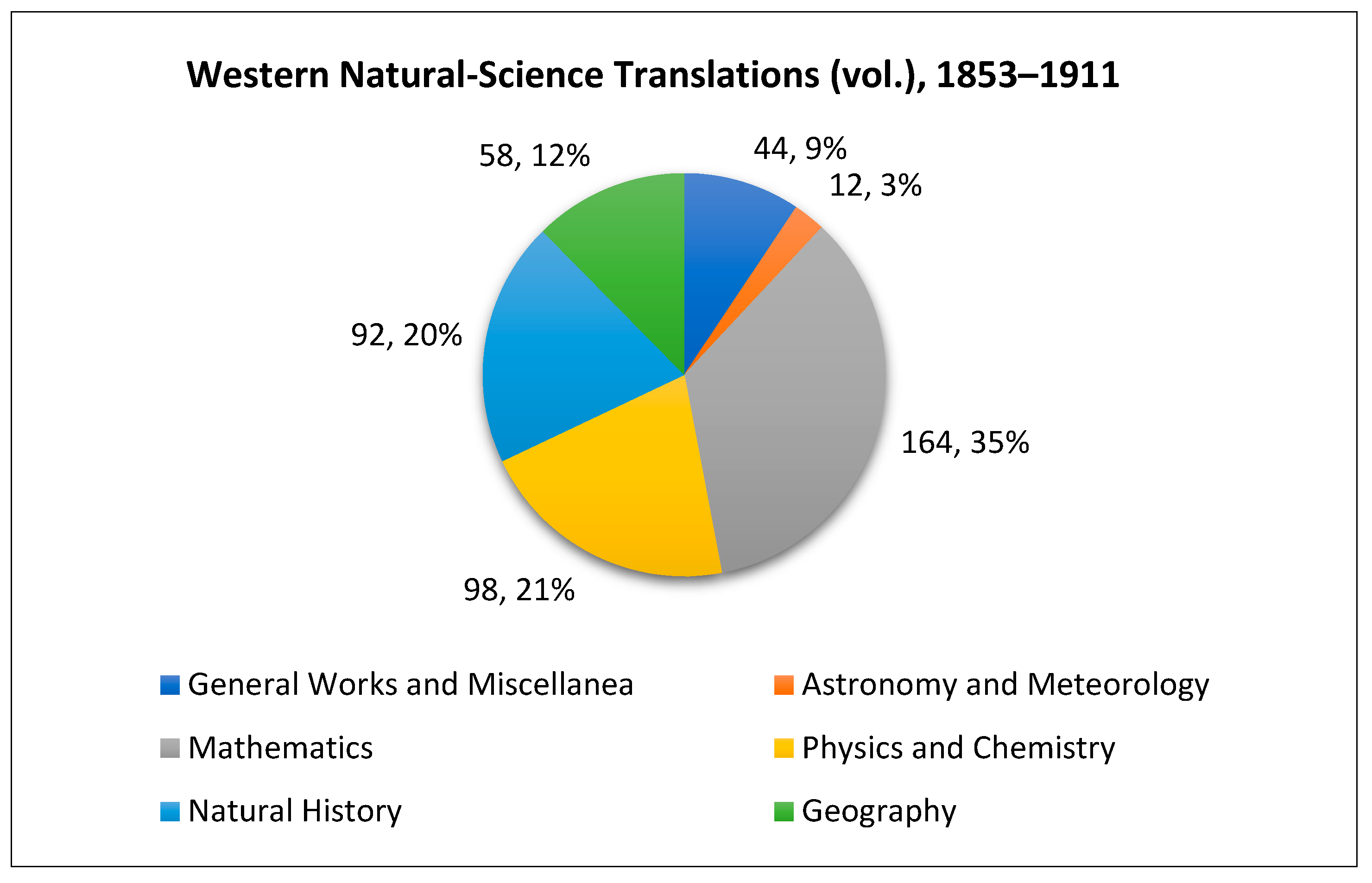

| Category | Quantity |

|---|---|

| General Works and Miscellanea | 44 volumes |

| Astronomy and Meteorology | 12 volumes |

| Mathematics | 164 volumes |

| Physics and Chemistry | 98 volumes |

| Natural History | 92 volumes |

| Geography | 58 volumes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, M.; Lin, A. Science Translation in Late Qing Christian Periodicals and the Disciplinary Transformation of Chinese Lixue. Religions 2025, 16, 1472. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16111472

Lu M, Lin A. Science Translation in Late Qing Christian Periodicals and the Disciplinary Transformation of Chinese Lixue. Religions. 2025; 16(11):1472. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16111472

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Mingyu, and Aiai Lin. 2025. "Science Translation in Late Qing Christian Periodicals and the Disciplinary Transformation of Chinese Lixue" Religions 16, no. 11: 1472. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16111472

APA StyleLu, M., & Lin, A. (2025). Science Translation in Late Qing Christian Periodicals and the Disciplinary Transformation of Chinese Lixue. Religions, 16(11), 1472. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16111472