Enhancing School Safety Frameworks Through Religious Education: Developing a Curriculum Framework for Teaching About World Religions in General Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Religious Conflicts as Safety Challenges in the Context of Multicultural Transition in South Korea

2.1. Interreligious Conflicts as Emerging Safety Challenges in Higher Education Institutions

2.1.1. Identifying the Issue: Factors in Religious Conflicts Within University Settings

2.1.2. Examining Cases of Religious Conflicts in and Beyond University Settings

Religious Conflicts at Dongguk University: Vandalism of the Buddha Statue in 2000 and Land-Claiming Prayer Activities in 2011

The Islamic Mosque Construction Conflict near Kyungpook National University

Halal Food and Prayer Space Accommodation Conflicts at Some Universities

Religious Conflicts Regarding Mandatory Chapel Attendance at Some Universities Affiliated with Christian Denominations

2.2. Toward Religious Literacy Through Religious Studies in General Education

3. Developing a Curriculum Framework for Religious Studies in General Education: Teaching About World Religions

3.1. School Safety Education Development for Enhancing Religious Literacy: The Research Institute of Comprehensive School Safety at Dongguk University

3.2. Course Overview and Class Contents

3.3. Primary Directions and Rationale for Course Design

Contemporary Needs for Religious Literacy Enhancement

Balance of Objectivity and Respect

Critical Reflection on the Category of Religion Itself

Integration of the Context of South Korea with Global Perspectives

3.4. Key Considerations in Course Design

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In South Korea, the Korean Ministry of Education uses the term school safety (Kor. 학교안전) to encompass comprehensive safety policies, measures, and preventive strategies for educational institutions, including safety protocols, emergency procedures, and educational programs across the entire educational system. The scope of school safety thus covers all educational institutions, ranging from early childhood centers to higher education. |

| 2 | According to Statistics Korea (2025), multicultural households are defined as households of those who acquired Korean nationality through naturalization or marriage immigrant households where foreign nationals are married to Korean spouses, including naturalized citizens. |

| 3 | The Research Institute of Comprehensive School Safety at Dongguk University has been actively conducting research to address these issues since September 2023. Regarding recent research outcomes from this project, see Lee et al. (2024a, 2024b); Yim and Kim (2025). |

References

- Ahn, Seungjin 안승진. 2018. “Geulsse” “Dangyeon” Cheot Halalfood Haksaengsikdang Barabo-Neun Seoul Daesaengdeul “글쎄” “당연” 첫 할랄푸드 학생식당 바라보는 서울대생들 [“Well…” “Of Course”: Seoul National University Students’ Views on the First Halal Food Student Cafeteria]. Segye Ilbo, April 2. Available online: https://www.segye.com/newsView/20180402005009 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Ahn, Shin 안신, and Sungmin Ryu 류성민. 2014. Segyeui Jonggyo [World Religions]. Seoul: Korea National Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ames, Roger T. 2005. Asian Philosophy, the Life and Creativity. Translated by Wonsuk Chang 장원석. Seoul: Sungkyunkwan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bulgyo Sinmun. 2002. Donggukdae Tto Hwebulsageon Balsaeng 동국대 또 훼불사건 발생 [Another Buddhist Vandalism Incident Occurs at Dongguk University]. Bulgyo Sinmun, February 15. Available online: https://www.ibulgyo.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=9274&utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Cho, Hyeok-jin 조혁진. 2023. “Sal-Abojido Anko”…Islam Sawon Chanban ‘Paengpaeng’ “살아보지도 않고”…이슬람 사원 찬반 ‘팽팽’ [“Without Even Living Here”…Opinions on Islamic Mosque Sharply Divided]. Daegu Sinmun, January 18. Available online: https://www.idaegu.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=408199 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Cho, Yuhyeon 조유현. 2019. Gidokgyo Daehak-Edo Islam Gidosil-i? 기독교 대학에도 이슬람 기도실이? [Islamic Prayer Rooms Even at Christian Universities?]. Daily Good News, July 30. Available online: https://www.goodnews1.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=89477 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Filipović, Ana Thea, and Marija Jurišić. 2024. Intercultural Sensitivity of Religious Education Teachers in Croatia: The Relationship between Knowledge, Experience, and Behaviour. Religions 15: 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Alliance for Disaster Risk Reduction & Resilience in the Education Sector (GADRRRES). 2022. Comprehensive School Safety Framework 2022–2030: For Child Rights and Resilience in the Education Sector. GADRRRES. Available online: https://gadrrres.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/CSSF-2022-2030-EN.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Gu, Jahyun, and Juhwan Kim. 2024a. Navigating the Intersections of Religion and Education Reflected in the Institutional Mission: Examining the Case of Dongguk University as a Buddhist-Affiliated Institution in South Korea. Religions 15: 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Jahyun, and Juhwan Kim. 2024b. Integrating Religion and Education through Institutional Missions: A Comparative Study of Yonsei and Dongguk Universities as Religiously Affiliated Institutions in South Korea. Religions 15: 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Jahyun, and Juhwan Kim. 2025. Religious Literacy in Contemporary South Korea: Challenges and Educational Approaches. Religions 16: 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, David Bentley. 2020. The Story of Christianity. Translated by Segyu Yang 양세규, and Hyerim Yun 윤혜림. Seoul: VIA. [Google Scholar]

- Im, Kowoon, Jonghun Kim, and Eunhye Lee. 2022. Jung·Godeunghakgyo Gisul·Gajeong Gyogwaseoui Anjeongyoyuk Pyeonseong Hyeonhwang Bunseok: Hakgyoanjeongyoyuk 7dae Pyojunaneul Jungsimeuro 중·고등학교 기술·가정 교과서의 안전교육 편성 현황 분석: 학교안전교육 7 대 표준안을 중심으로 [Analyzing Safety Education Applied in Middle and High School Technology·Home Economics Textbook: Based on the 7 School Safety Education Standards]. Gyoyuk Munhwa Yeongu 교육문화연구 [Journal of Education & Culture] 28: 435–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Jieun 강지은, and Hyeyeon Park 박혜연. 2024. “Gomtang Gateungeon Mot Meokdeora”…Islam·Hindugyo Yuhaksaeng Neulja Daehak Sikdan Bakkwinda “곰탕 같은건 못 먹더라”…이슬람·힌두교 유학생 늘자 대학 식단 바뀐다 [“They Can’t Eat Things Like Gomtang”…University Cafeteria Menus Adapt as Muslim and Hindu International Students Increase]. Chosun Ilbo, January 15. Available online: https://www.chosun.com/national/national_general/2024/01/15/VP5RCQPTWVCNRASVINUU7ZARPY/ (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Kang, Jiyong, Yeonghwi Ryu, Yeon-Woo Chang, and Yae-ji Hu. 2023. 2022 Gaejeong Chodeunghakgyo Gyoyukgwajeong-Eseoui Anjeongyoyuk Banyeing Yangsang Bunseok 개정 초등학교 교육과정에서의 안전교육 반영 양상 분석 [Enhancing Safety Education in Elementary Schools: Analysis of Integration of Safety Education in the 2022 Revised National Curriculum]. Gyoyuk Munhwa Yeongu 교육문화연구 [Journal of Education & Culture] 29: 101–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keown, Damien. 2020. Buddhism: A Very Short Introduction, 2nd ed. Translated by Seunghak Koh 고승학. Paju: Gyoyoseoga. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Hyeon-tae 김현태. 2011. Donggukdae “Gyonae Bulbeopjeok Seongyohaengwi Jwasi Anket-Tta” 동국대 “교내 불법적 선교행위 좌시 않겠다” [Dongguk University: “We Will Not Tolerate Illegal Missionary Activities on Campus”]. Beopbo Sinmun, December 1. Available online: https://www.beopbo.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=68440 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Kim, Yeon-jin 김연진. 2023. Daegu Islam Sawon Sinchuk Galdeung 3 Yeonui Jeonmal 대구 이슬람 사원 신축 갈등 3년의 전말 [The Complete Story of the 3-Year Conflict Over the Construction of an Islamic Mosque in Daegu]. Jugan Chosun, June 9. Available online: https://weekly.chosun.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=26873 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Ko, Sangmin 고상민. 2013. Hanyangdae-e Halal Sikdang Isaekgaeeop…Muslim Haksaeng Hwanyeong 한양대에 할랄 식당 이색개업…무슬림 학생 환영 [Hanyang University Opens Unique Halal Restaurant…Muslim Students Welcome It]. Yonhap News, March 7. Available online: https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20130307135000004 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Korean Ministry of Education. 2015. Yu·Cho·Jung·Go Baldaldangyebyeol ‘Hakgyo Anjeongyoyuk 7 Daeyeongyeok Pyojunan’ Balpyo 유·초·중·고 발달단계별 ‘학교 안전교육 7 대영역 표준안’ 발표 [Announcement of Seven Standards for School Safety Education by Developmental Stages for Kindergarten, Elementary, Middle, and High School]. Available online: https://www.moe.go.kr/boardCnts/fileDown.do?m=0201&s=moe&fileSeq=63686eb172b508f6b0be8436d8540c7b (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Korean Ministry of Education. 2020. Hakgyo Anjeonsago Gwanrijiwon Gaeseon Bangan 학교 안전사고 관리지원 개선 방안 [School Safety Accident Management Support Improvement Plan]. Available online: https://www.moe.go.kr/boardCnts/fileDown.do?m=020402&s=moe&fileSeq=e714bb877ecf703aa670ba7614e73d9c (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Korean Ministry of Justice. 2025. Chulipgukja-Mit-Cheryu-Oegukin-Tonggye 출입국자및체류외국인통계 [Statistics on Entry/Departure and Foreign Residents]. Gwacheon: Korean Statistical Information Service (KOSIS). Available online: https://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=111&tblId=DT_1B040A14&language=en (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Leaman, Oliver. 2025. Judaism. Translated by Jae-Deog Yu 유재덕. Seoul: Penielpub. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Hye-jo 이혜조. 2011. Jongrip Donggukdaemajeo Gidokgyoui Hwebulhaengwi Manyeon 종립 동국대마저 기독교의 훼불행위 만연 [Vandalism of Buddhist Property by Christians Rampant Even at Buddhist-Affiliated Dongguk University]. Bulkyodotcom, December 1. Available online: https://www.bulkyo21.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=16792 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Lee, Hyo Jung, Namin Shin, Chohee Yoon, Gwang Guk Yim, and Juhwan Kim. 2024a. Haksaeng Anjeoncheheomsiseol-ui Cheheomhyeong Anjeongyoyuk Program Gyoyuk Hyogwaseong Bunseok mit Gaeseonbangan Geomto 학생안전체험시설의 체험형 안전교육 프로그램 교육 효과성 분석 및 개선방안 검토 [An Analysis of Educational Effectiveness for Experience-Based Safety Education Programs at Student Safety Experience Facilities]. Gyoyuk Munhwa Yeongu 교육문화연구 [Journal of Education & Culture] 30: 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Juho, Jihye Kang, Jong-Bae Park, Hyun-Joo Park, and Sang-Sik Cho. 2024b. Foucault-ui 『Anjeon, Yeongto, Ingu』ui Gaenyeom Deul-Eul Tonghan COVID-19 Sidae Hakgyo Anjeonjeongchaek-e Daehan Bunseok 푸코의 『안전, 영토, 인구』의 개념 틀을 통한 코로나-19 시대 학교안전정책에 대한 분석 [Analysis of School Safety Policies in the Age of COVID-19 through Foucault’s Conceptual Framework of Security, Territory, and Population]. Gyoyuk Bipyeong 교육비평 [Education Review] 56: 140–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malović, Nenad, and Kristina Vujica. 2021. Multicultural Society as a Challenge for Coexistence in Europe. Religions 12: 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuzawa, Tomoko. 2005. The Invention of World Religions. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- National Human Rights Commission of Korea. 2022. Daehakgyoui Daechegwamok Deung Eopneun Chapel Sugang Gang-Yo-Neun Jonggyoui Jayu Chimhae 대학교의 대체과목 등 없는 채플 수강 강요는 종교의 자유 침해 [Forcing University Students to Attend Chapel Without Alternative Courses Violates Religious Freedom]. Available online: https://www.humanrights.go.kr/site/program/board/basicboard/view?currentpage=1&menuid=001004002001&pagesize=10&boardtypeid=24&boardid=7608183 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Oh, Kang-nam 오강남. 2013. 세계 종교 둘러보기 Segye Jonggyo Dulreobogi [A Tour of World Religions]. Seoul: Hyeonamsa. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Hyondo 박현도. 2024. Islam-Eul Wihan Byeonmyeong [In Defense of Islam]. Seoul: Bulkwang Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Jinyong, and Jonggap Seo. 2018. Seouldae Sikdangseo ‘Halal-Eumsik’ Jegong…Muslim “Gulmeul GEOKJEONG Anhaeseo Dahaeng” 서울대 식당서 ‘할랄음식’ 제공…무슬림 “굶을 걱정 안해서 다행” [Seoul National University Cafeteria Provides ‘Halal Food’…Muslims: “Relieved Not to Worry About Going Hungry”]. Seoul Economic Daily, April 2. Available online: https://www.sedaily.com/NewsView/1RY3N4EXA9 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Park, Jun-seong 박준성. 2012. Joleopkkaji Jehanha Chapel Deul-eo Bosyeotnayo? 졸업까지 제한한 채플 들어 보셨나요? [Have You Ever Heard About Chapel Requirements That Can Prevent Graduation?]. Cheonji Ilbo, December 4. Available online: https://www.newscj.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=161365 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Sen, Kshitimohan. 2018. Hinduism. Translated by Hyoung jun Kim 김형준, and Jiyeon Choe 최지연. Seoul: HUiNE. [Google Scholar]

- Seong, Hae-young 성해영. 2024. ‘Jonggyo Munhaeryeok’ui Uimiwa Yeokhal’: Sahoejeok Hwalyong Banganeul Jungsimeuro ‘종교 문해력’의 의미와 역할: 사회적 활용 방안을 중심으로 [The Meaning and Role of ‘Religious Literacy’: Focusing on Social Application Strategies]. Jonggyo Yeongu 종교연구 [Studies in Religion (The Journal of the Korean Association for the History of Religions)] 84: 9–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Arvind. 2013. Our Religions: The Seven World Religions Introduced by Preeminent Scholars from Each Tradition. Translated by Myung-Kwon Lee 이명권. Seoul: Sonamu. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Pyeong-in 송평인. 2000. Donggukdae Bongwan-ap Yaoebulsang Sipjaga Geuryeojinchae Hweson 동국대 본관앞 야외불상 십자가 그려진채 훼손 [Buddhist Statue in Front of Dongguk University Main Building Vandalized with Cross Drawn on It]. Dong-A Ilbo, June 5. Available online: https://www.donga.com/news/article/all/20000605/7543250/1 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Statistics Korea. 2025. 2025 Population and Housing Census: Multicultural Households. Daejeon: Korean Statistical Information Service (KOSIS). Available online: https://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=101&tblId=DT_1JD1505&language=ko (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Yang, Seung-sik 양승식. 2011. “Gidokgyoui Dokseonjeokin Seongyohaengwi Mukgwa Anket-tta” Donggukdae-e Museun-il-i? “기독교의 독선적인 선교행위 묵과 않겠다” 동국대에서 무슨일이? [“We Will Not Overlook Christianity’s Dogmatic Missionary Activities” What’s Happening at Dongguk University?]. Chosun Ilbo, November 30. Available online: https://www.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2011/11/30/2011113002667.html (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Yim, Gwang Guk, and Juhwan Kim. 2025. Wiheomui Gaeinhwawa Taljeongchihwaga Hakgyoanjeongyoyuk-e Michin Yeonghyang: Beck, Giddens, Foucault-ui Gwanjeom-Eul Jungsim-Euro 위험의 개인화와 탈정치화가 학교안전교육에 미친 영향: Beck, Giddens, Foucault의 관점을 중심으로 [The Impact of Risk Individualization and Depoliticization on School Safety Education: A Critical Analysis Based on the Theories of Ulrich Beck, Anthony Giddens, and Michel Foucault]. Gyoyuk-ui Irongwa Silcheon 교육의 이론과 실천 [Theory and Practice of Education] 30: 19–39. [Google Scholar]

| Years | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Students | 96,357 | 115,927 | 135,087 | 160,670 | 180,131 | 153,361 | 163,697 | 197,234 | 226,507 |

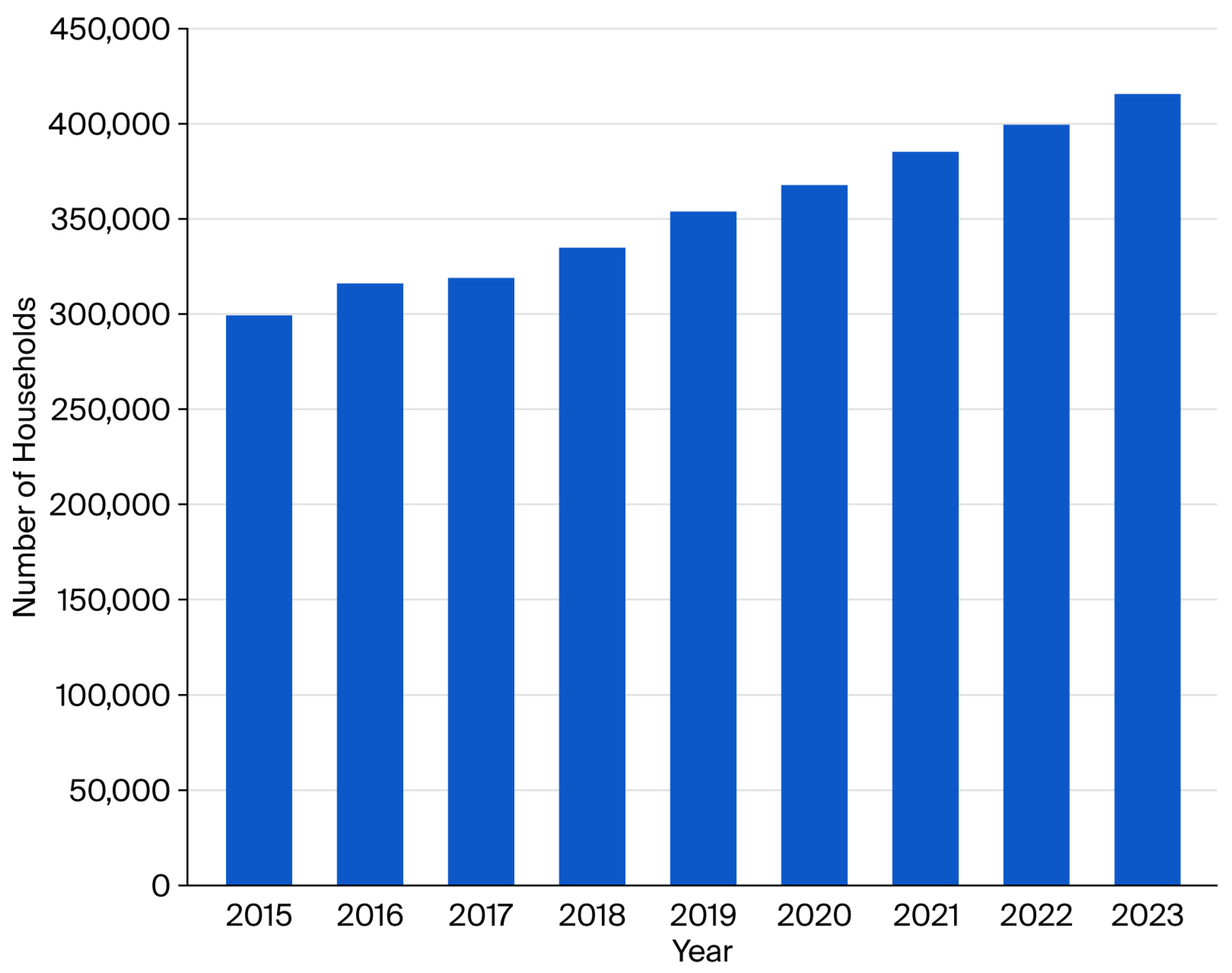

| Years | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Households | 299,241 | 316,067 | 318,917 | 334,856 | 353,803 | 367,775 | 385,219 | 399,396 | 415,584 |

| Category | Title [English Translation] | Author [Korean Translator] | Publisher | Year | ISBN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Textbook | Segye Jonggyo Dulreobogi [A Tour of World Religions] | Oh, Kang-nam | Hyeonamsa | 2013 | 9788932316727 |

| Textbook | Our Religions: The Seven World Religions Introduced by Preeminent Scholars from Each Tradition | Sharma, Arvind [Lee, Myung-Kwon] | Sonamu | 2013 | 9788971395790 |

| Textbook | Segyeui Jonggyo [World Religions] | Ahn, Shin & Ryu, Sungmin | Korea National Open University Press | 2014 | 9788971395790 |

| Supplementary Text | Hinduism | Sen, Kshitimohan [Kim Hyoung jun & Choe Jiyeon] | HUiNE | 2018 | 9791159013782 |

| Supplementary Text | Buddhism: A Very Short Introduction, Second Edition | Keown, Damien [Koh, Seunghak] | Gyoyoseoga | 2020 | 9791190277402 |

| Supplementary Text | Asian Philosophy, the Life and Creativity | Ames, Roger T. [Chang, Wonsuk] | Sungkyunkwan University Press | 2005 | 9788979866094 |

| Supplementary Text | Judaism | Leaman, Oliver [Yu, Jae-Deog] | Penielpub | 2025 | 9791193092392 |

| Supplementary Text | The Story of Christianity | David Bentley Hart [Yang Segyu & Yun Hyerim] | VIA | 2020 | 9788928647538 |

| Supplementary Text | Islam-eul Wihan Byeonmyeong [In Defense of Islam] | Park Hyondo | Bulkwang Publishing | 2024 | 9791193454619 |

| Week | Class Topic | Class Objective | Class Contents |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | What is Religion? |

|

|

| 2 | Indigenous Religions and Shamanism |

|

|

| 3 | Hinduism: Formation and Development |

|

|

| 4 | Sikhism and Jainism |

|

|

| 5 | Buddhism: Origins and Development |

|

|

| 6 | Buddhism: Transmission and Regional Variations |

|

|

| 7 | East Asian Religious Traditions |

|

|

| 8 | Midterm Exam |

| Week | Class Topic | Class Objective | Class Contents |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | Judaism |

|

|

| 10 | Christianity: Formation and Expansion |

|

|

| 11 | Christianity: Divisions and Modern Developments |

|

|

| 12 | Islam: Foundation and Expansion |

|

|

| 13 | Islamic Civilization and Contemporary Islam |

|

|

| 14 | Atheism and Contemporary Religious Discourses |

|

|

| 15 | Interreligious Dialogue and the Future |

|

|

| 16 | Final Exam |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gu, J.; Kim, J. Enhancing School Safety Frameworks Through Religious Education: Developing a Curriculum Framework for Teaching About World Religions in General Education. Religions 2025, 16, 1465. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16111465

Gu J, Kim J. Enhancing School Safety Frameworks Through Religious Education: Developing a Curriculum Framework for Teaching About World Religions in General Education. Religions. 2025; 16(11):1465. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16111465

Chicago/Turabian StyleGu, Jahyun, and Juhwan Kim. 2025. "Enhancing School Safety Frameworks Through Religious Education: Developing a Curriculum Framework for Teaching About World Religions in General Education" Religions 16, no. 11: 1465. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16111465

APA StyleGu, J., & Kim, J. (2025). Enhancing School Safety Frameworks Through Religious Education: Developing a Curriculum Framework for Teaching About World Religions in General Education. Religions, 16(11), 1465. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16111465