2. The Principle of Generation

This section examines the principle of generation itself, beginning with Lombard’s reflections in Sent. I, d. 6. Our analysis will then proceed to Aquinas’s corresponding expositions in Super Sent. I, d. 6; De pot., q. 2, a. 3; and ST I, q. 41, a. 2. A notable absence from this list is the Summa contra Gentiles; Aquinas does not appear to delve into this specific question in that work, except for a brief refutation of Arianism in ScG IV, c. 11. The objective of this section is therefore to analyze Lombard’s elucidation of the topic alongside Aquinas’s expositions in these texts and to evaluate their doctrinal compatibility.

2.1. Sent. I, d. 6

The underlying problem in Sent. I, d. 6 is the apparent incompatibility between nature and will. If one maintains that God generates the Son willingly, then, Lombard notes, “the heretic would immediately have achieved the conclusion which he desired, namely that the Son is not the son of God’s nature, but of his will.” Lombard begins his inquiry by presenting two opposing views. The first, which he introduces as the position of others (Sent. I, d. 6, c. un., n. 2), seeks to circumvent this difficulty by asserting that “it is not to be granted that God is God by will or necessity, nor willingly or unwillingly; nor that he generated the Son by will or necessity, nor willingly or unwillingly.” He then considers an alternative view, which posits that because God’s will and nature are identical to his essence, the Son can be said to be generated by will just as he is by nature. Lombard, however, refutes this second opinion, arguing that

although the knowledge and will of God are one and the same, not everything that is said of the will is said of the knowledge, and vice versa. Nor does God will with his will all those things that he knows with his knowledge, since his knowledge knows both good and evil, whereas his will wills only what is good …. Thus, although the nature of God and his will are one, it is nevertheless said that the Father begot the Son by nature, not by will, and that he is God by nature, not by will.

(

Sent. I, d. 6, c. un., n. 3)

3

This said, Lombard returns to the first “prudently” made opinion (n. 2), according to which “God the Father is God neither willingly nor unwillingly, and that he begot the Son neither willingly nor unwillingly (that is, by will or by necessity) …” (n. 4). He then proceeds to argue that the term will in this opinion designates “a preceding or approaching will [voluntatem praecedentem vel accedentem], of the kind that Eunomius understood” (n. 4). The reference to Eunomius prompts us to return to the first paragraph of the distinction, where Lombard quotes a passage from Augustine that sheds light on Eunomius’s error:

Unable to understand and unwilling to believe that the only-begotten Word of God is the Son of God by nature, that is, begotten of the Father’s substance, [Eunomius] said that the Son is not of nature or substance, but a son of God’s will. He thereby asserted that a will approached God by which he might beget the Son [accedentem Deo voluntatem qua gigneret Filium], just as we sometimes will something that we previously did not will, on account of which our nature is understood to be mutable—may we be far from believing that this exists in God.

(Sent. I, d. 6, c. un., n. 1)

It would seem that the voluntas accedens mentioned in paragraph four corresponds to the voluntas accedens alluded to in paragraph one. As to its meaning, Lombard, following Augustine, explains that this type of will is at work when “we sometimes will something that we previously did not will.” This description suggests that voluntas accedens, when applied to the generation of the Son, would imply that the Father did not eternally will to generate the Son but came to will it at a certain point. Such a posterior act of will would entail mutability in God—a consequence Lombard explicitly rejects (Sent. I, d. 6, c. un., n. 1). Following his critique of the Eunomian position, Lombard appears to state his own stance in paragraph four:

For God is not God by a preceding or efficient will, nor was he willing before he was God. Nor did he beget the Son by a preceding or approaching will, nor did he beget the Son by willing before begetting. Nevertheless, he begot as one who is willing, just as he begot as one who is powerful, as one who is good, and as one who is wise, and so on. For if the Father is said to have begotten the Son as wise and good, why not also as willing? For God, to be willing is the same as to be God, just as to be wise is the same as to be God. Therefore, let us say that the Father, just as he is wise, so also begot the Son as willing, but not by a preceding or approaching will. Augustine explains and confirms this meaning in his commentary on the Epistle to the Ephesians, saying: “It is written of the Son of God, that is, our Lord Jesus Christ, that he was always with the Father, and the paternal will never preceded him in order for him to exist. And he is, indeed, Son by nature.”.

(Sent. I, d. 6, c. un., n. 4)

It is evident, then, that, for Lombard, who follows Augustine’s teaching, the Son is generated by nature. At the same time, Lombard’s exposition allows for the affirmation that the Father begets the Son willingly. This willing is best understood through the lens of what Aquinas would later term voluntas concomitans (concomitant will). To corroborate this avant la lettre attribution of the concept to Lombard, it is necessary to turn to Aquinas’s writings on the subject.

2.2. Super Sent. I, d. 6

Aquinas’s commentary on Sent. I, d. 6 proceeds systematically through three articles, which inquire whether the Father generates the Son by necessity (a. 1), by will (a. 2), or by nature (a. 3).

In the

sed contra of the first article, Aquinas frames the problem by citing the argument that since “every necessity is due to some stronger power compelling it,” and since nothing is stronger than God, it follows that “in God, there can be no necessity.”

4 To resolve this dilemma, Aquinas turns to Aristotle’s analysis of the multiple meanings of the term

necessary. Aquinas’s objective is to demonstrate that while God is entirely free from certain kinds of necessity, he is the ultimate foundation of another kind of necessity.

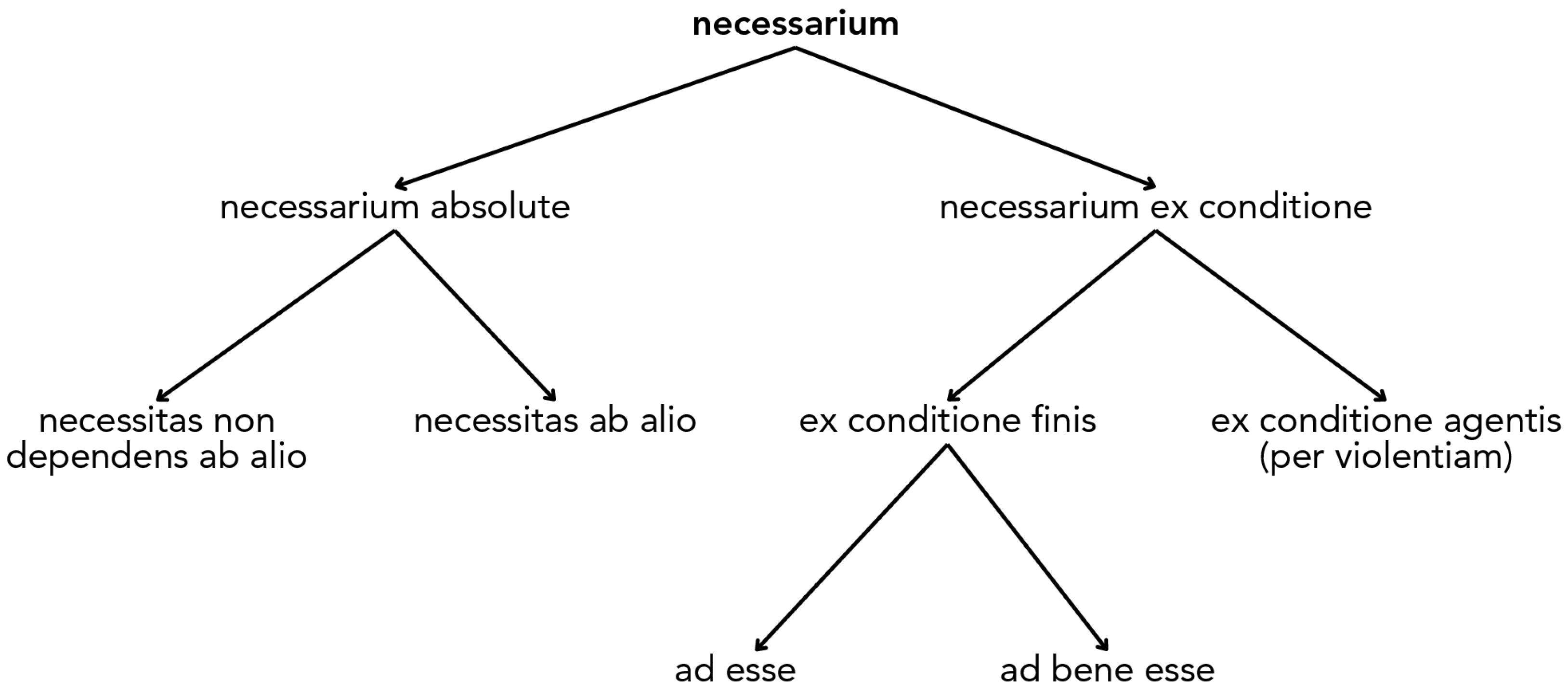

Aquinas begins by distinguishing between conditional and absolute necessity (cf.

Figure 1).

5 Conditional necessity (

necessarium ex conditione) arises not from a thing’s intrinsic nature, but from an external condition imposed upon it. Aquinas identifies two forms of this necessity. The first is necessity from an agent (

necessarium ex conditione agentis), which refers to coercion by an external force. This is the type of necessity from a stronger power that the

sed contra rightly denies in God. The second is necessity for an end (

necessarium ex conditione finis), which describes something required to achieve a particular goal. This latter form is further subdivided into that which is necessary for a thing’s being (

finis ad esse), such as nourishment for life, and that which is necessary for its well-being (

finis ad bene esse), such as a ship for a sea voyage.

In contrast, absolute necessity (necessarium absolute) arises from the intrinsic principles of a thing’s essence. In composite beings, this necessity stems from their constituent principles, whether material (e.g., mortality in humans) or formal (e.g., rationality in humans). In simple beings such as God, this necessity is identical to the essence itself. Aquinas further distinguishes this absolute necessity according to its source. It can be derived, as it is in any created thing that has a cause, or it can be underived, belonging only to that being whose necessity depends on no other and is the source of all other necessity. This underived absolute necessity, he concludes, is proper to God alone.

Based on these distinctions, Aquinas resolves the initial problem. He argues that divine generation does not proceed from any conditional necessity, as it is neither compelled by an external agent nor required for an external end. Rather, the generation of the Son is necessary with an absolute, underived necessity. This necessity flows not from any external constraint or internal need, but from the uncaused, self-sufficient perfection of the divine essence, which is itself the cause of all being and all necessity (Super Sent. I, d. 6, a. 1, co.).

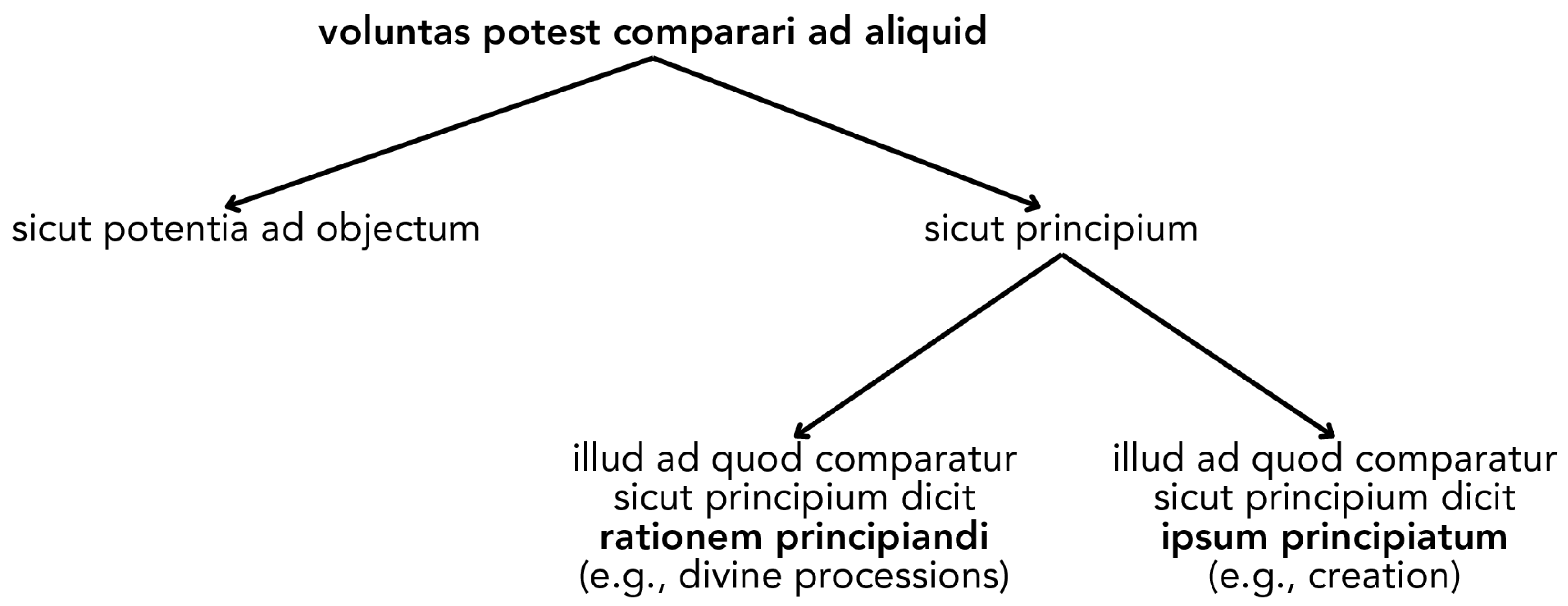

The second article of the distinction addresses whether the Father generates the Son by will (

Super Sent. I, d. 6, a. 2). Aquinas demonstrates that while the generation of the Son is a willed act, it is not willed in the same manner as creation. The solution lies in carefully distinguishing the senses in which the will can relate to an act. He begins by noting two primary modes of this relation: the will can relate to something as a power to its object (

potentia ad objectum) or as the principle of that thing (cf.

Figure 2).

First, when the will relates to something as a power to its object, its act is one of approval or resting in a good presented to it. In this mode, the will does not cause the object, but delights in it. Understood this way, “everything willed by God can be said to be by his will,” and thus one can affirm that “the Father is God by his will” and “the Father generated the Son by will.”

Second, when the will relates to something as its principle, it is the active source from which that thing proceeds. Aquinas posits that this relationship can be understood in two distinct ways: The first mode is when the object of the will expresses the foundational rationale of the originating act itself (dicit rationem principiandi). Here, that which proceeds from a principle (principiatum) is not a terminal product but the immanent, formal logic through which the principle subsequently produces other effects. Aquinas illustrates this with the processions of the divine persons. The divine will is the principium, and the procession of the Holy Spirit as uncreated Love is the principiatum. This eternal procession functions as the ratio principiandi, the very modality of the divine will’s operation. Consequently, when the divine will acts ad extra to create, it does so according to this eternal pattern of Love. In a parallel structure, the divine intellect is the principle of the eternal generation of the Son, who proceeds as the Word and Art of the Father. This generation of the Word functions as the ratio principiandi for the divine intellect’s ad extra operations. In both cases, the immanent Trinitarian processions constitute the essential, internal rationale that underpins God’s external, creative work.

In the alternative mode, the will relates to its object as the originated thing itself (dicit ipsum principiatum), focusing not on an intermediary rationale, but on the final product. According to Aquinas, whatever originates from the will in this mode proceeds according to the will’s own defining condition: its freedom. It follows that things originated by the will (principiata voluntatis) are exclusively those that are contingent, that “can be or not be.” This mode applies directly to the created order, which exists not by necessity but as a result of God’s free choice. Conversely, this mode does not apply to the generation of the Son. As an eternal and necessary act of the divine intellect, the Son’s generation cannot be understood as a principiatum of the will in this second sense.

To summarize this framework, Aquinas references a threefold distinction of the will proposed by other thinkers: voluntas accedens, voluntas concomitans, and voluntas antecedens (Super Sent. I, d. 6, a. 2, co.). This vocabulary helps to specify which sense of will properly applies to the necessary act of generation versus the free act of creation. A more detailed analysis of these terms will be undertaken later; for now, it is sufficient to note their role in Aquinas’s argument.

The final article of the distinction considers whether the Father generates the Son by nature (Super Sent. I, d. 6, a. 3). Aquinas builds upon his argument that the divine essence is the principle of all divine acts, introducing a crucial distinction: the essence, considered absolutely, is the principle not of an operation, but of existence (esse) itself.

Nevertheless, specific divine acts are attributed to the essence by virtue of its diverse attributes, which, while ontologically identical to the essence, are conceptually distinct. The character of the act determines which attribute is considered its principle. The act of understanding, for instance, proceeds from the divine essence insofar as it is intellective, while the production of contingent realities proceeds from the essence insofar as it is will. Following this logic, Aquinas reasons that since generation by definition entails the production of a being in the likeness of its generator—a process governed by the intrinsically natural principle that like begets like (ex similibus similia procreans)—it must be affirmed that the Father generates the Son by nature (Super Sent. I, d. 6, a. 3, co.).

In recapitulating Aquinas’s exposition in Super Sent. I, d. 6, it is clear that determining the principle of the Son’s generation requires a synthesis of nature, necessity, and will. The Son’s generation is fundamentally an act by nature, which Aquinas later calls the principium proprium of this procession (Super Sent. I, d. 7, div. text.), for it entails the production of a being in perfect likeness to its generator. This natural act is not contingent but is characterized by an absolute necessity that flows not from external compulsion or need, but from the perfection of the divine essence itself. Finally, this natural and necessary act is eternally affirmed by a concomitant will—not a will that chooses between alternatives, but one that perfectly and lovingly embraces the generation proceeding from the Father’s nature. Thus, for Aquinas, the generation of the Son is an act by nature, which is therefore absolutely necessary, and which is perpetually affirmed by a concomitant will.

2.3. De pot., q. 2, a. 3

De pot., q. 2, a. 3, offers a more philosophically detailed defense of the Son’s natural generation than the earlier

Sentences commentary and shares significant theological ground with

ST I, q. 41, a. 2. The examination of this text will begin by addressing an apparent tension between Aquinas’s argument here and his position in

Super Sent. I, d. 6, a. 2 (cf.

Table 2). The later discussion on the development of doctrine will specifically treat the classification of the types of will found in

De pot., q. 2, a. 3, ad 2.

As established in the previous section, Aquinas’s commentary on the Sentences presents the divine will as a principle of the divine processions. The argument in De pot., q. 2, a. 3, however, appears to contradict this. In this later work, Aquinas concedes that the generation of the Son is an object of the divine will, yet he claims that the will can in no way be the principle of divine generation. This apparent change in doctrine requires a close examination of the full argument in De pot., q. 2, a. 3.

Central to the argument of this article is Aquinas’s distinction between nature and will, which is drawn more sharply here than in his Sentences commentary. He defines nature as being “determined to one thing” (ad unum), a principle he will later repeat in ST I, q. 41, a. 2. Citing Avicenna, Aquinas asserts that what is uncreated exists necessarily by itself (per se necesse est esse), containing no potential for non-existence. It is in this sense that the tradition affirms that “the Son was born not by will, but by nature.”

Aquinas proceeds by considering the will from a twofold perspective: first as will qua will, and second as will that is naturally inclined to an object. The will qua will is defined by its freedom toward alternatives (ad utrumlibet). From this it follows that any effect whose primary principle is the will must be contingent, meaning it could have been otherwise. Aquinas connects this metaphysical status directly to createdness, forming a syllogism aimed at Arianism: (1) to be produced by will as a principle is to be contingent; (2) to be contingent is to be a creature; (3) therefore, to claim the Son is generated by will is to reduce him to a creature.

The second perspective concerns the will not in its freedom, but in its necessary orientation. Aquinas states that if the will’s freedom toward alternatives does not apply, “this happens to the will not insofar as it is will, but on account of a natural inclination it has toward something, such as toward the ultimate end, which it cannot not-will; just as the human will cannot not-will beatitude, nor can it will misery.” He thus explains that while the will is free regarding external objects, it possesses a necessary, natural inclination toward its ultimate end. For God, this ultimate end is himself.

When this principle is applied to the divine processions, Aquinas notes that God’s intellect engages in a natural and necessary act of knowing himself. This perfect self-knowledge is not an act chosen from alternatives, but is an eternal and essential reality. The procession of the Son as the Word is this natural act of the intellect. In a similar way, God’s will engages in a natural and necessary act of loving himself as the supreme good, which constitutes the procession of the Holy Spirit as Love.

By distinguishing between the will qua will (which is free) and the will as naturally inclined to its end (which is necessary), Aquinas can maintain that the Spirit proceeds by way of will without being a contingent creature. The procession of the Spirit is rooted in the will, but because its object is God himself, this procession is both natural and necessary. This distinction between the will qua will and the will as naturally inclined to its end also resolves the apparent contradiction between Aquinas’s earlier and later works. His statement in Super Sent. I, d. 6, a. 2, that the divine will is a principle of the processions, can be understood in light of the clarification in De pot., q. 2, a. 3: the principle is not the will qua will, but the will as naturally inclined to its ultimate end: God himself. Affirming that the principle of the divine processions is not the will qua will implies, in turn, that the divine processions are not contingent—that is, they are not events that could have failed to happen or have happened otherwise.

This framework clarifies why Aquinas insists that, while the generation of the Son is an object of the divine will, the will is not its principle. He maintains in De pot., q. 2, a. 3, ad 12, that “the Father wills the property [ratio] of the Son, which pertains to a concomitant will that regards the generation as an object, not as that of which it is the principle.” The ratio mentioned is nothing but the Son’s personal property of filiation. This act of a concomitant will is, in turn, an instance of the will as a power directed to its object (potentia ad objectum), as described in Super Sent. I, d. 6, a. 2. To posit the will as the productive principle of generation would be, in Aquinas’s view, an Arian error (ST I, q. 41, a. 2, co.).

In summary, Aquinas’s argument in De pot., q. 2, a. 3 synthesizes the concepts of nature, necessity, and will to explain the divine processions. While this text offers a less detailed treatment of the types of necessity than his commentary on the Sentences, it clearly presupposes that earlier analysis. Here, Aquinas succinctly links necessity to nature through the Avicennian principle that what is uncreated exists necessarily by itself (per se necesse est esse).

2.4. ST I, q. 41, a. 2

In ST I, q. 41, a. 2, the parallel text to Super Sent. I, d. 6, Aquinas addresses the foundational question of whether the Son’s generation is an act of will or of nature. The core of his argument rests on a sharp distinction between two modes of production. It should also be noted that while Aquinas treats the concept of necessity here, his exposition is a condensed summary of the more comprehensive analysis found in his Sentences commentary.

Production by nature is a process “determined to a single outcome” (determinata est ad unum), a principle Aquinas also invoked in De pot., q. 2, a. 3. This is the mode proper to the generation of the Son, since God is per se necessary being, an expression that echoes the reference to Avicenna in De pot. The effect of such a process proceeds from the very being of the agent and thus shares the agent’s nature, just as an effect resembles the agent’s form. For God, whose nature is one and perfect, whatever proceeds from him by nature must be someone equal to himself in nature. This procession is the generation of the Son.

Production by will, in contrast, is not determined to a single outcome. The agent chooses among various possibilities based on an understood idea (ratio intellecta), and the effect conforms not to the agent’s nature, but to the agent’s idea and desire. An artisan, for instance, builds a chair that resembles the idea of a chair in his mind rather than the artisan himself. This mode of production pertains to things that “can be one way or another,” which is characteristic of creation. Hence, Aquinas argues that to posit the Father generating the Son by will would be to categorize the Son as a creature—contingent, external to God’s essence, and not divine by nature. This was the error of the Arians, whom Aquinas explicitly refutes. The Son, therefore, proceeds from the Father by nature, whereas the universe proceeds from God by will.

To refine his position, Aquinas recognizes the ambiguity of the expression by will (voluntate) and resolves it by identifying two distinct meanings. First, it can designate the concomitant will that simply accompanies an act. In this sense, one can say that “the Father generated the Son by will, just as he is God by will.” Second, it can designate the will as the “principle of the work” (principium operis). In this sense, the will is the originating cause of a contingent act, which is how God creates.

Finally, the article’s third objection contends that the Holy Spirit must proceed voluntarily, since nothing is more voluntary than love, and the Spirit proceeds as Love. In his response, Aquinas argues that the procession of the Spirit by way of will is also a natural act, because God loves himself naturally. He thus concludes, “the Spirit proceeds naturally, although he proceeds by the mode of the will” (

ST I, q. 41, a. 2, ad 3). This statement provides a more explicit affirmation of the compatibility between proceeding by will and proceeding by nature, a compatibility to which Aquinas had already alluded in

De pot., q. 2, a. 3 (cf.

Table 3).

2.5. Development of Doctrine

An analysis of Aquinas’s treatment of the principle of the Son’s generation across his major works reveals a remarkable consistency in his fundamental position. His doctrine concerning the interplay of nature, will, and necessity in the generation of the Son remains constant: the core elements supporting his conclusions in the Summa theologiae are already operative in his commentary on the Sentences.

While the core doctrine is stable, its articulation is not static. A clear development can be traced in the way Aquinas categorizes and enumerates the types of divine will. This terminological evolution, which the following analysis will detail, demonstrates a progression toward greater precision, even as the foundational distinctions are preserved. To trace this development accurately, it is necessary to distinguish, particularly in the

Sentences commentary, between Aquinas’s formulation and the enumeration he attributes to certain other thinkers (

quidam) (cf.

Table 4).

A fundamental distinction between two primary modes of the divine will persists across the texts under consideration, forming the bedrock of Aquinas’s analysis.

The necessary will of complacency in the good. The first mode is the will associated with the necessary, intra-Trinitarian life of God, specifically in the generation of the Son. In his early Sentences commentary, Aquinas uses the phrase voluntas sicut potentia ad objectum (A1) to describe the will as a natural power directed to its object. This corresponds to what some other thinkers, cited by Aquinas, call voluntas concomitans (B1). In De pot., the concept is expressed as the voluntas ex inclinatione naturali quam habet ad finem ultimum (C2), the will’s natural inclination toward its ultimate end. This concept eventually crystallizes into the more technical and relational term voluntas concomitans (B1, D1, E1). This terminological convergence underscores Aquinas’s consistent teaching that the generation of the Son is an act of the divine intellect, not of choice. The will does not cause the generation, but necessarily delights in and accompanies this natural, perfect act of divine self-knowledge.

The free will of creative action. The second mode is the will associated with God’s action ad extra, primarily creation. In the Sentences commentary, this is the will that acts as a principle signifying the originated thing itself (A3), thereby producing a contingent effect. The thinkers referenced by Aquinas in this work call this voluntas antecedens (B3), a term synonymous with voluntas praecedens (D3). De pot. articulates this mode of willing with the expression voluntas inquantum voluntas (C3)—will qua will—thereby emphasizing its innate freedom. The Summa theologiae offers the more functional description voluntas qua principium operis (E3), the will as the principle of the work. The doctrinal convergence here is theologically crucial: creation is always understood as a free act. The universe is contingent; it does not proceed from a necessity in God’s nature, but from a sovereign, uncompelled choice.

The evolution of Aquinas’s thought is most apparent in the divergences between these classifications, which reveal a refinement of his terminology and focus.

The shift tovoluntas concomitans. The move away from the descriptive phrases in the early works (A1, C2) to the technical term voluntas concomitans (E1) represents a significant terminological development. Concomitant will more precisely articulates the will’s exact role: it is a will of approval that accompanies the intellect’s necessary act. This term is more exact and less prone to misinterpretation than a general reference to a natural inclination, clarifying that the will is fully operative, but not causative in the Son’s generation.

The disappearance of the termratio principiandi. A notable divergence is the presence of the category voluntas sicut principium when it expresses the ratio principiandi (A2), an idea found exclusively in his Sentences commentary. This concept, where the immanent procession of the Son serves as the foundational pattern for the external act of creation, is not employed as a formal category of will in the later works. Its absence in De pot. and the Summa suggests a move toward a more streamlined and dichotomous presentation. While the underlying idea of the Son as the divine Exemplar or Art remains, Aquinas sets aside this specific classification of the will in favor of a more direct distinction between the will that accompanies generation and the will that causes creation, thereby avoiding the complexities inherent in positing the will as ratio principiandi.

Context-specific categories. The classifications also reveal that some distinctions are tailored to specific theological problems. The category of voluntas praecedens intellectu (D4), for example, appears in De pot. to address a particular question about the order of divine actions related to disposition and predestination. Similarly, the notion of voluntas accedens (B5), attributed to the quidam, is mentioned only to be dismissed as inapplicable to God’s immutable nature. This indicates that Aquinas did not intend to create a single, exhaustive list, but rather employed classifications suited to the argument at hand, while always relying on the above-outlined core distinction between voluntas concomitans and voluntas antecedens as his foundation.

In conclusion, the evolution of Aquinas’s enumeration of the will demonstrates a clear trajectory from broader metaphysical descriptions to more precise, functional, and technical terminology. The stable convergence on the distinction between the necessary will related to generation and the free will related to creation underscores the consistency of his core doctrine. The divergences, particularly the adoption of voluntas concomitans and the disuse of the ratio principiandi model, reveal an intellectual refinement that prioritizes clarity and a more direct articulation of how the divine will operates both within the Trinity and toward the world.

An examination of the terminology itself is necessary to trace this doctrinal development. While Lombard does not employ the term voluntas concomitans, he clearly describes the concept when he states that God “begot as one who is willing, just as he begot as one who is powerful, as one who is good, and as one who is wise, and so on” (Sent. I, d. 6, c. un., n. 4). Aquinas adopts this same understanding, identifying voluntas concomitans as pertaining to “the will’s relation to its object” (B1).

Lombard explicitly speaks only of voluntas praecedens (preceding will) and voluntas accedens (approaching will), and he consistently presents them as a disjunctive pair: voluntas praecedens vel accedens (Sent. I, d. 6, c. un., n. 4). This disjunction does not necessitate that he considered them equivalent. Interpreted through a Thomistic lens, it is plausible to view Lombard’s voluntas praecedens as synonymous with what Aquinas calls voluntas antecedens (De pot., q. 2, a. 3, ad 2), and to distinguish both from voluntas accedens, a distinction Aquinas himself makes when citing the quidam (Super Sent. I, d. 6, a. 2, co.).

Lombard understands voluntas accedens—based on his reading of Eunomius—as “[willing] something that we previously did not will” (Sent. I, d. 6, c. un., n. 1). Aquinas’s report of the quidam’s view is in harmony with this, describing it as a will that “newly approaches to the work or the worker,” a mode of willing that “does not exist in God in any sense, because his every operation is from an eternal will” (B5). Voluntas accedens refers to a will that appears in time, a new act preceding a new action. Philological evidence suggests that voluntas accedens belongs primarily to the lexicon of the young Aquinas, likely mirroring Lombard’s vocabulary. The term voluntas accedens appears in Aquinas’s corpus almost exclusively in Super Sent. I, d. 6, q. 1, a. 2, and its use elsewhere (e.g., “nisi voluntate accedente” in De virtut., q. 2, a. 3, ad 12) does not refer to this specific type of willing.

Aquinas’s references to voluntas antecedens, however, can present textual difficulties. He describes voluntas antecedens as “the will’s relation as a principle to that which is produced from it” (B3). This would be the will at work in creation (in the case of God) and in human generation (in the case of humans) (Super Sent. I, d. 6, a. 2, ad 2). In De pot., q. 2, a. 3, ad 2, however, he first denies that there is any voluntas antecedens in God “because whatever God wills at any time, he has willed from eternity.” Yet, in the same response, he affirms two types of antecedent will in God: one “preceding or antecedent in time,” which exists only with respect to a creature (D3), and one “preceding in understanding,” which exists with respect to eternal acts that terminate in creatures, such as predestination (D4). A plausible reconciliation of this passage is that when Aquinas first denies voluntas antecedens, he has in mind the concept of a temporal, changeable will, which is the proper definition of voluntas accedens (B5). Moreover, it is important to read this apparent inconsistency within the framework of Aquinas’s understanding of the God-creature relation as an asymmetrical relation—one that is real in creatures, but only of reason in God (cf. ST I, q. 13, a. 7, co.). When God created things out of nothingness, the novelty lies in the effects of God’s action (that is, in the realm of temporality), not in God himself (that is, within his own timeless eternity).

The distinction between voluntas accedens and voluntas antecedens is further clarified by examining the latter in contrast to voluntas consequens (a term raised in the objections of De pot., q. 2, a. 3). In Aquinas’s thought, antecedent will is God’s will for a thing considered in its essential nature, apart from specific circumstances—for instance, that all humans be saved (cf. De verit., q. 23, a. 2, co.; ScG I, c. 72; ST I-II, q. 19, a. 10, co.). Consequent will is God’s will for a thing considered in light of all circumstances, including free creaturely acts, by which he executes justice. This makes the distinction sharp: voluntas antecedens is an eternal, unchanging divine will applicable to God, whereas voluntas accedens “does not exist in God in any sense” (B5), since it denotes a temporal, changeable will. It is crucial to note that this entire framework of distinctions does not imply a division within God’s simple, eternal will. It is a logical distinction, from the human perspective, based on the object being willed and the circumstances surrounding it.

3. Potentia Generandi and Omnipotence

This section examines whether the Father’s potentia generandi is part of divine omnipotence. The significance of this inquiry becomes evident when considering its principal implications. An affirmative answer would suggest that the Son, as an omnipotent person, must also possess potentia generandi. A negative answer, conversely, would seem to render the term potentia in the phrase potentia generandi equivocal. Aquinas, as this article will demonstrate, resolves this dilemma through a distinction that safeguards both the singularity of the Father’s paternal relation and the Son’s full possession of the divine nature.

3.1. Sent. I, d. 7

This inquiry originates in Distinction 7 of Lombard’s Sentences, which serves as the foundation for the reflections of Aquinas to be examined here. Lombard addresses a central question regarding the immanent Trinity: “the commonness of the principle of the generation, that is, whether the power to generate is common to the Father and the Son” (Aquinas, Super Sent. I, d. 7, div. text.). The inquiry arises not from mere speculation, but from a direct polemical context, specifically the challenge posed by Arians such as Bishop Maximinus. Their argument presented a stark dilemma: if the Father was able, or willed, to beget the Son, he possessed a capacity or volition that the Son lacked, as the Son could neither will nor execute his own generation (Sent. I, d. 7, c. 1, n. 1). The Arians contended that such a disparity would entail a subordination of the Son to the Father, thereby subverting the doctrine of consubstantiality.

Lombard’s response involves a reframing of divine generation. He posits that “to be able or willing to beget the Son is to be able to do or to will something; but the begetting of the Son is not one of the things which are subject to the divine power and will.” Divine generation is not a temporal act preceded by potentiality or choice, but is, rather, an eternal reality that is “above and before all things [super omnia et ante omnia].” The Father never existed in a state of non-generation, for “he did not exist before he generated because he was from all eternity and he generated from all eternity.” Crucially, Lombard distinguishes relational identity from substantive being: “to be Father is not the same as to be something [esse Patrem non est esse aliquid].” Consequently, the Father’s unique relational property of paternity does not imply that he possesses a power the Son lacks, or that he wills something that the Son, who lacks this relation, cannot. The distinction is one of relation, not of substance or capacity (Sent. I, d. 7, c. 1, n. 1). This framework, like a nascent seed, already holds the promise of what will later blossom, in Aquinas, into the full bloom of his theology of divine relations (cf. ST I, q. 28).

Lombard subsequently examines the testimony of Augustine, who had previously addressed the query from Maximinus. Augustine proposed that the Son’s not begetting is a matter of propriety, not inability: “It is not that the Son could not beget the Creator, but that it was not fitting that he should do so.” Lombard discerns from this that Augustine appears to concede that the Son possesses a latent potentia generandi. Augustine illustrates the unfittingness of exercising such a power by highlighting the logical absurdity of an infinite generative series: to demonstrate his power, the Son would need to generate a son (the Father’s grandson), who would in turn beget another, and so forth, lest any divine person be considered impotent (Sent. I, d. 7, c. 1, n. 2).

Despite his appeal to Augustine’s authority, Lombard expresses reservations regarding this line of reasoning, asserting that it is impossible for the Son to beget. Lombard’s argument proceeds by eliminating every logical alternative, demonstrating that each terminates in a theological absurdity. If the Son were to beget, he would become a father. This paternity could only exist in relation to one of four possibilities: the Father, himself, the Holy Spirit, or a de novo reality. Each option is untenable: the Father is ungenerated; no entity can generate itself; the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son through spiration, and to be generated is proper to the Son; and no other co-eternal being exists that could be generated (Sent. I, d. 7, c. 1, n. 3).

Acknowledging the problem’s intricacy, Lombard suggests that Augustine’s statement “would be better passed over in silence, if the insistence of those asking did not compel [Lombard] to say something on the matter” (Sent. I, d. 7, c. 1, n. 4). He therefore offers a reinterpretation of Augustine’s intention. Lombard proposes that Augustine’s central point was to establish that the Trinitarian personal properties are positive identifiers, not markers of privation or deficiency. Accordingly, just as the Father is Father by the property of paternity and not from any lack of power, so too the Son is Son by the property of filiation, not from an inability to be otherwise (Sent. I, d. 7, c. 1, n. 5).

This leads to Lombard’s conclusion. He affirms that the Father possesses by nature the power to beget the Son because the divine power is identical to the divine essence. This identity of power and essence, however, does not imply that the Father has a power that the Son lacks. Rather, “the Son has exactly the same power as the Father” (Sent. I, d. 7, c. 2, n. 2). It is by this single, undifferentiated divine power that the Father eternally begets and the Son is eternally begotten. The distinction lies not in the power itself, but in the properties or notions through which that power is expressed. The Father has the property by which he is Father and begetter; the Son has the property by which he is Son and begotten (Sent. I, d. 7, c. 2, n. 3). This unity of power extends to the divine will, whereby “one and the same is the will of the Son by which he wills himself to have been generated, and the Father to have generated him” (Sent. I, d. 7, c. 2, n. 4). Lombard thus resolves the Arian paradox by locating the distinction between the persons not in a hierarchy of power or will, but in the constitutive properties of the Godhead.

3.2. Super Sent. I, d. 7, q. 1, a. 1

Let us now turn to Aquinas’s commentary on that same distinction of the Sentences. In Super Sent. I, d. 7, q. 1, a. 1, Aquinas addresses whether the eternal generation of the Son falls under the purview of divine omnipotence. His analysis proceeds by distinguishing two modes of procession from God.

The first mode of procession, exemplified by the generation of the Son from the Father, is founded upon a communication of nature. Aquinas draws an analogy to the natural power in creatures, whereby a being generates another of the same nature (e.g., a human begets a human). In God, this generation is realized in a transcendent manner, as the Son receives the numerically same divine nature from the Father. Such an act is not an exercise of omnipotence. Rather, the procession of a divine person occurs “by a quasi-natural power [

per potentiam quasi naturalem]” (

Super Sent. I, d. 7, q. 1, a. 1, co.). This phrase, a

hapax legomenon in the Thomistic corpus,

6 appears to designate a power in God that is analogous to, yet transcends, the

potentia naturalis found in creatures.

The second mode of procession, which pertains to the creation of the universe, is based on the likeness an effect has to the idea in the mind of its maker. Aquinas compares this to the rational or artistic power in creatures, through which an artisan produces an artifact based on a form in the intellect (e.g., a builder constructs a house). The product conforms to the idea, but it does not share the nature of the artisan. This creative power is what is properly designated as divine omnipotence.

Therefore, Aquinas concludes that omnipotence, properly speaking, refers to God’s power over all that is creatable. Since the Son is not a creature but a divine person who proceeds by a communication of the Father’s nature, his generation is not an act of omnipotence, but an act intrinsic to the divine nature.

3.3. De pot., q. 2, a. 1

In De pot., q. 2, a. 1, Aquinas offers a more extensive argument than in his Sentences commentary for the reality of a potentia generandi in the Father. The argument hinges on demonstrating that the term potentia, in this context, does not imply imperfection (a passive potentiality), but rather signifies the perfection of an active generative capacity.

Aquinas begins with the metaphysical principle that actuality (actus) is inherently self-communicative. Whatever exists in a state of actuality tends to communicate or produce that actuality. Since God is defined as pure actuality (maxime et purissime actus), with no admixture of potentiality, it follows that he is self-communicative in the highest degree (De pot., q. 2, a. 1, co.).

Having established this principle, Aquinas distinguishes—in a manner analogous to his exposition in Super Sent. I, d. 7, q. 1, a. 1—two modes of divine communication. The first is the communication of the divine nature by likeness to creatures. These beings exist by participation and bear a likeness to God, but they do not receive the divine nature itself; a human, for instance, resembles God, but is not divine. The other mode is the “quasi-natural communication [communicatione quasi naturali]” of the divine nature itself. The one who receives this communication (the Son) is not merely like God, but is truly God, possessing the numerically same, undivided divine nature. This procession is properly called generation (De pot., q. 2, a. 1, co.). The expression communicatio quasi naturalis recalls the phrase potentia quasi naturalis from Super Sent. I, d. 7, q. 1, a. 1, co. Like its counterpart, communicatio quasi naturalis is a hapax legomenon in the Thomistic corpus.

To explain how a nature can be fully communicated without being divided or altered, Aquinas highlights two critical differences between the divine nature and all created forms. First, the divine nature is subsistent. Deity is not a quality that God possesses; it is what God is. In contrast, humanity is a nature that an individual person (such as Socrates) has, but the person is not identical to the abstract nature of humanity. Because the divine nature subsists in itself, it does not require reception into a separate, material substrate to exist. Second, in God alone, nature or essence is identical to the act of being (esse). For creatures, their nature receives being, but does not possess it inherently. This identity means that when God communicates his nature, he communicates his very being, which is one and undivided. The Son and the Father therefore share one and the same being.

To render this intelligible, Aquinas employs what he considers the most congruent analogy for the Trinity: the human mind understanding itself. When the intellect thinks, it produces an interior word or concept (verbum). When the intellect understands itself, this proceeding word (verbum progrediens) issues from the intellect as a likeness of it. In the human intellect, however, this interior word is merely a likeness, because the human intellect is not identical to the human essence, and the act of thinking does not communicate human nature. In God, by contrast, the intellect is the divine essence. Therefore, when God understands himself, the proceeding Word is not a mere likeness, but a perfect expression that is of the same essence as its source (the Father). Because this intelligible procession is also a communication of the whole nature, it can be rightly termed generation.

Finally, Aquinas addresses the term power itself (De pot., q. 2, a. 1, co.). He concedes that, in God, there is no real distinction between power (potentia) and action (actio) as there is in creatures: “the power posited in God is properly neither active nor passive, since in him there is neither the category of action nor of passion, but his action is his substance” (De pot., q. 2, a. 1, ad 1; cf. Super Sent. I, d. 7, q. 2, a. 2, co.). However, because human language derives from experience of the created world, where every action proceeds from a corresponding power, we must speak of God’s eternal act of generation by analogy. We thus attribute to the Father a potentia generandi to signify that he is the principle of this eternal act. This is a power understood not as an unrealized potential, but as the active principle of an eternal and perfect act, whereby the Son, who is not a created effect, eternally receives the same infinite nature (De pot., q. 2, a. 1, co.).

3.4. De pot., q. 2, a. 5

In De pot., q. 2, a. 5, Aquinas also inquires whether the Father’s potentia generandi is part of divine omnipotence. His argument rests upon the nuanced thesis that potentia generandi pertains to the omnipotence of the Father, but not to omnipotence considered absolutely (simpliciter). The subtlety of this distinction marks a development from his exposition in Super Sent. I, d. 7, q. 1, a. 1, where the exclusion of potentia generandi from the domain of divine omnipotence was more categorical: “the power to generate is not contained under omnipotence, as the power to create is” (Super Sent. I, d. 7, q. 1, a. 1, co.).

The argument requires a twofold distinction within divine omnipotence. On the one hand, omnipotentia simpliciter refers to the divine power as it is rooted in the divine essence, which is common to all three persons. The Father, the Son, and the Spirit equally possess this one omnipotence. On the other hand, omnipotentia Patris (paternal omnipotence) is the same divine omnipotence, but considered together with the specific, personal property of the Father. It is not a different or separate power, but is omnipotence as expressed through the Father’s personal mode of being (omnipotentia prout est Patris tantum). This expression should be read in light of the previously mentioned phrases potentia quasi naturalis (Super Sent. I, d. 7, q. 1, a. 1, co.) and communicatio quasi naturalis (De pot., q. 2, a. 1, co.).

A similar formulation appears in De pot., q. 9, a. 9, where Aquinas asks how the Son can possess the whole divine nature, but not the generative power inherent to it. He resolves this by reasoning that potentia generandi is not a property of the divine nature taken absolutely, as if it were an attribute like omnipotence. Instead, paternity belongs to the divine nature as it is expressed in the person of the Father (prout est in persona Patris). The Son, therefore, possesses the same divine nature, but he possesses it as Son, a mode of being constituted by the opposite relation of filiation (De pot., q. 9, a. 9, ad 2; cf. ad 10).

These formulations all articulate how an essential reality, common to the divine persons, is possessed in a personal mode by the Father. The Father and Son share the same absolute reality: the divine essence. Paternity is this one, simple divine essence as it subsists in the Father. It cannot subsist in the Son because the relation of paternity is defined by its opposition to the relation of filiation, which constitutes the distinct person of the Son.

This raises the central question: If the Father has paternity—and therefore potentia generandi—and the Son does not, does this imply the Father has something the Son lacks, thereby violating their equality? Aquinas’s answer is negative. The distinction between Father and Son is not one of substance (quid), but of relation (ad quid). Thus, the Father does not have something (aliquid) the Son lacks; rather, the divine essence subsists in him with a different relation than it does in the Son.

In conclusion, potentia generandi is divine omnipotence, but it is omnipotence considered under the relational aspect of paternity; it is a personal act, not an essential one. The Son possesses the same omnipotence as the Father because he possesses the same essence and can do everything the Father can do in an absolute sense. He cannot, however, generate, because the term generate already implies the personal relation of paternity, which he does not have. His inability to generate is not a lack of power, but a consequence of his personal identity as the Son. In Aquinas’s words, “generare ad aliquid dicitur”—“to generate is said relatively” (De pot., q. 2, a. 5, co.).

3.5. ST I, q. 41, a. 4

In ST I, q. 41, a. 4, Aquinas distinguishes potentia generandi (and potentia spirandi) from creaturely potentiality and from the way we speak of God’s power to will or understand. Aquinas applies the definition of potentia as “the principle of an act” to the Trinity. The Father is understood as the principle of the act of generation, while the Father and the Son are the principle of the act of spiration. Therefore, since they are the principles of these acts, it follows that corresponding powers must be attributed to them: potentia generandi and potentia spirandi (ST I, q. 41, a. 4, co.).

A key distinction in Aquinas’s analysis appears in ST I, q. 41, a. 4, ad 3, where he outlines two ways a principle can be distinguished from that which proceeds from it. The first way involves a real distinction (secundum rem). This real distinction can be either essential, as between God as principle and creatures as his proceeding effects, or personal, as between the Father as principle and the divine persons who proceed from him through the notional acts of generation and spiration. Because these acts terminate in something really distinct—whether essentially or personally—from the principle, a power (to create, to generate, to spirate) can be properly attributed to God.

The second way involves a merely conceptual distinction (secundum rationem) between an agent and an act, such as God’s acts of understanding and willing. In this case, the distinction between God as the principle and the acts that proceed from him is one of reason alone, given that in reality, these acts are identical to the divine essence and do not terminate in anything distinct from God. Because there is no real distinction between the agent and the act, one cannot speak of a “power to will” or a “power to understand” in the same proper sense. Such terms are used only “according to our mode of understanding and signifying,” as an accommodation of human language to divine reality (ST I, q. 41, a. 4, ad 3; cf. Super Sent. I, d. 7, q. 2, a. 1).

In summary, Aquinas affirms the language of power for the acts of generation and spiration because they involve a real distinction between the persons as principle and term. He thereby assigns metaphysical weight to the personal actions within the Trinity, while simultaneously distinguishing them from God’s ad extra actions (such as creating) and his ad intra self-identical acts (such as willing).

4. The Nature of Potentia Generandi

This section concerns the nature of the Father’s potentia generandi: is it an essential attribute belonging to the divine nature common to all three persons, or is it a personal one belonging exclusively to the Father? The theological implications of this question are significant. If generation is an act of the divine nature, the power for that act must also be essential. Yet, if potentia generandi belongs to the divine essence, it would seem that all three persons should possess it, a conclusion that contradicts orthodox Trinitarian doctrine.

4.1. Super Sent. I, d. 7, q. 1, a. 2

In Super Sent. I, d. 7, q. 1, a. 2, Aquinas posits a nuanced intermediate category, rejecting a simple dichotomous classification. He argues that potentia generandi is neither purely absolute and essential nor purely relative and personal, but a unique hybrid: it is essential “under the aspect of a relation” (essentiale sub ratione relationis) (Super Sent. I, d. 7, q. 1, a. 2, co.). This phrase, a hapax legomenon in the Thomistic corpus, conveys an idea Aquinas repeats elsewhere (cf. Super Sent. I, d. 23, q. 1, a. 3, ad s.c.).

His position unfolds as follows. The ultimate principle of any divine act, including generation, is the one divine essence; in this respect, the power is absolute and essential. The essence, however, does not act in a generic or undifferentiated manner, but through the distinct personal properties. According to Aquinas’s key formula, the principle of generation is the divine essence “insofar as it is paternity itself” (

essentia secundum quod est ipsa paternitas).

Potentia generandi, then, is wielded not by the essence in the abstract, but by the Father, in whom the essence subsists with the unique relational property of paternity (

Super Sent. I, d. 7, q. 1, a. 2, co.). This formulation might well be a precursor to his later expression, “

omnipotentia prout est Patris tantum” (

De pot., q. 2, a. 5, co.), which was examined in

Section 3.4.

Aquinas employs an analogy with creatures to clarify this point, only to demonstrate how the divine reality transcends it. In creatures, a common nature (such as the animal soul) is contracted or limited by the specific faculty it inhabits (e.g., an eye sees, an ear hears). This does not occur in God. The divine nature is not limited or altered by the personal properties of the Father, the Son, and the Spirit. This is because the properties are not accidents added to the essence; they are the essence, subsisting in particular relational modes. The relation of paternity does not change the essence, but it does distinguish the Father as a person eternally ordered toward another (ad alterum)—that is, toward the Son (Super Sent. I, d. 7, q. 1, a. 2, ad 3).

In sum, potentia generandi is “a kind of middle ground [quasi medium] between the essential and the personal” (Super Sent. I, d. 7, q. 1, a. 2, co.)— “between the absolute and the relative” (Super Sent. I, d. 7, q. 1, a. 2, ad 3). It is absolute insofar as it is rooted in the essence, which is its source, and it is relative insofar as it is conjoined to the personal operation. This solution allows Aquinas to maintain that the divine essence is the single source of power in the Trinity while simultaneously explaining how certain acts, such as generation, are exclusive to a single person.

4.2. Super Sent. I, d. 23, q. 1, a. 3

In Super Sent. I, d. 23, q. 1, a. 3, ad s.c., Aquinas delineates four distinct modes of signification in divine matters. He explains that while some terms signify the absolute in an absolute manner (e.g., God) and others signify a relation in a relative manner (e.g., Father), this simple dichotomy is insufficient. He therefore posits a third mode, in which a concept such as potentia generandi signifies something absolute, but does so in the manner of a relation (absolutum per modum relationis). This formulation mirrors his expression in Super Sent. I, d. 7, q. 1, a. 2: “essentiale sub ratione relationis.” This third mode is then distinguished from a fourth, which presents a conceptual structure inverse to the third: the term person itself signifies what is relative, but does so in the manner of an absolute substance. Aquinas grounds the possibility of these varied modes of signification in the real identity of relation and substance in God, concluding that it is because the divine relation is the divine essence that divine realities can be signified in these different ways (Super Sent. I, d. 23, q. 1, a. 3, ad s.c.).

4.3. De pot., q. 2, a. 2

In De pot., q. 2, a. 2—as he did in Super Sent. I, d. 7, q. 1, a. 2, and will do in ST I, q. 41, a. 5—Aquinas examines what, precisely, the term potentia generandi signifies. He approaches this methodically, refuting two insufficient opinions before arriving at his own synthetic conclusion.

The first opinion, as reported by Aquinas, argues that since power (potentia) implies a principle, and principle is a relative term (i.e., a principle of something), potentia generandi must be purely relational or notional—a term signifying a personal distinction, such as paternity. Aquinas refutes this opinion on two grounds. First, he distinguishes between the concept of a principle (ratio principii), which is relational, and the thing that is the principle, which is an absolute reality or form. He notes that Aristotle places power in the category of quality, not relation; therefore, potentia generandi must be rooted in an absolute reality. Second, Aquinas argues that notional terms are those that define the persons in relation to each other (e.g., paternity, filiation), whereas terms referring to divine operations (such as willing or understanding) are considered essential, belonging to the one divine nature. Since potentia generandi is a principle of an operation, it cannot be purely notional.

Having established that potentia generandi must be rooted in the divine essence, the next logical position is that it signifies only the essence, a view supported by several authorities cited in the sed contra. Aquinas argues, however, that an action, while proceeding from a common nature, always bears the characteristics of the specific agent performing it. He employs an analogy: the power of imagination is common to animals, but in a human being, it is elevated and modified by rationality. Similarly, while generation proceeds from the common divine nature, it is an act performed only by the Father. Therefore, the divine nature, as the principle of this specific act, must be considered as it is determined by the personal property of the Father (secundum quod competit proprietati personali Patri). It is thus impossible to speak of potentia generandi without implicitly referring to the person who alone possesses it. To say it signifies only the essence is insufficient, as this ignores the personal character of the act.

After demonstrating the inadequacy of viewing potentia generandi as either merely the relation of paternity or as an abstract power of the divine nature, Aquinas arrives at his conclusion: the term signifies the divine essence and paternity at once (simul). It signifies the divine essence as the absolute reality and principle of the act of generation, and it simultaneously signifies the personal notion of paternity, because it is the essence as possessed by the Father and ordered specifically to the act proper to him alone—the generation of the Son.

4.4. ST I, q. 41, a. 5

In ST I, q. 41, a. 5, in an argument parallel to those previously examined (Super Sent. I, d. 7, q. 1, a. 2; De pot., q. 2, a. 2), Aquinas begins by refuting the position that potentia generandi signifies only the relation of paternity. He notes that potentia generandi in any being is that reality in which (in quo) the offspring is similar to the parent. The Son is similar to the Father not in the relation of paternity, but in their shared divine nature. It follows, therefore, that the divine nature is the potentia generandi in the Father (in ipso).

Aquinas thus argues that potentia generandi signifies the divine essence principally (principaliter) and directly (in recto), while signifying the relation of paternity indirectly (in obliquo). He states: “the power to generate principally signifies the divine essence, as the Master says in Sent. I, d. 7, and not just the relation. Nor does it signify the essence insofar as it is the same as the relation, such that it would signify both equally” (ST I, q. 41, a. 5, co.).

His argument against identifying potentia generandi with the personal property proceeds by analogy. In creatures, the individual form (e.g., that which makes Socrates Socrates) constitutes the person, but it is not the means of generation; if it were, Socrates would generate another Socrates. Likewise, paternity constitutes the person of the Father, but it cannot be that by which he generates; otherwise, the Father would generate another Father. That by which he generates is the divine nature, in which the Son is assimilated to him (ST I, q. 41, a. 5, co.). At this point, it is crucial to distinguish between the principle who acts (the agent, i.e., the Father) and the principle by which the agent acts (the divine nature). Potentia generandi refers to the latter—the shared nature—which is why this power does not imply a division within God (ST I, q. 41, a. 5, ad 1). The term potentia generandi, then, signifies power directly and generation obliquely, just as the phrase essentia Patris signifies essence directly and Father obliquely. Consequently, with respect to the essence which is signified, potentia generandi is common to the three persons; but with respect to the notion which is connoted, it is proper to the person of the Father (ST I, q. 41, a. 5, ad 3).

In summary, the affirmation that potentia generandi signifies the divine essence principally (principaliter) and directly (in recto), while signifying the relation of paternity indirectly (in obliquo), allows Aquinas to maintain that this power is substantially the divine essence, while also explaining why only the Father can be said to possess it.

4.5. ST I, q. 42, a. 6, ad 3

In

ST I, q. 42, a. 6, ad 3, Aquinas refutes the objection that the Son is not equal in power to the Father, arguing that the objection misunderstands the nature of divine power and relation. He explains that, just as the one divine essence is paternity in the Father and filiation in the Son, so the one divine omnipotence is possessed by each according to his personal mode. The Son has the same power as the Father, but with a different relation: the Father possesses it in a giving mode, signified by the act of generating, while the Son possesses it in a receiving mode, signified by the act of being generated. Therefore, Aquinas concludes, the inability to generate does not indicate a lesser power in the Son, but rather manifests his distinct personal relation. The objection’s error, he notes, lies in treating a relational act (generating) as if it were an absolute capacity (

quid), when it is truly a matter of relation (

ad aliquid) (cf.

Section 3.4).

4.6. Development of Doctrine

The question of whether the Father’s

potentia generandi is essential or relational reveals shifts of emphasis in Aquinas’s position, even as he maintains his core affirmations. In

Super Sent. I, d. 7, q. 1, a. 2, he asserts that

potentia generandi is essential “under the aspect of a relation” (

essentiale sub ratione relationis)—an expression echoed elsewhere in the same work, where he describes it as signifying the absolute in the manner of a relation (

absolutum per modum relationis) (

Super Sent. I, d. 23, q. 1, a. 3, ad s.c.). Within

Super Sent. I, d. 7, a certain priority of the essential over the personal is already discernible: the power is essential, yet qualified by a relation. As Boyle rightly observes, Aquinas’s rejection of a purely personal understanding of this power is motivated by the analogical character of power itself: in the created order, power is essential. If divine power were purely personal, the analogy between it and creaturely power would break down (

Boyle 2000, p. 585). This apparent precedence of the essential is, however, qualified by Aquinas’s other affirmation in the same passage that

potentia generandi is “a kind of middle ground [

quasi medium] between the essential and the personal.” If

medium is understood as an equidistant point between two extremes, then it would be incoherent to affirm that the power is more essential than it is relational.

In

De pot., q. 2, a. 2, co., an expression resonates with the

essentiale sub ratione relationis of the

Sentences commentary. Here, Aquinas upholds the divine nature as the principle of generation “inasmuch as it is determined by the personal property of the Father” (

secundum quod competit proprietati personali Patri). His conclusion, nonetheless, is still reminiscent of the

quasi medium, stating that

potentia generandi “signifies the essence and the notion simultaneously” (

simul), implying that it is equally essential and notional. The development in

De potentia lies in its honing of the analogical reasoning, as Boyle has suggested (

Boyle 2000, pp. 586–87). Whereas the commentary on the

Sentences offers the general analogue of the sensitive soul operating differently in various organs (

Super Sent. I, d. 7, q. 1, a. 2, co.),

De potentia presents more developed creaturely analogues:

For instance, an action which is due to animal nature is done in a human being according to what is fitting for the principles of the human species; hence a human being has the act of the imaginative power more perfectly than other animals, according as it is fitting to his rationality. Similarly, the action of a human being is found in this or that human being according to what is fitting for the individual principles of this or that one, from which it happens that one person understands more clearly than another.

(De pot., q. 2, a. 2, co.)

A decisive breakthrough appears in ST I, q. 41, a. 5, with the affirmation that “the power to generate principally signifies the divine essence, as the Master says in Sent. I, d. 7, and not just the relation. Nor does it signify the essence insofar as it is the same as the relation, such that it would signify both equally” (ST I, q. 41, a. 5, co.). Here, it becomes clear that potentia generandi is closer to the essential pole than to the relational one. This shift is, in fact, perceivable in the Alia lectura (d. 7, q. 2, co.), a work of debated authenticity roughly contemporary with the Prima Pars. In ST I, q. 41, a. 5, potentia generandi is no longer a quasi medium; it principally and directly (principaliter et in recto) designates the divine essence, signifying the relation of paternity only obliquely.

The reason for this increased precedence of the essential is a matter of speculation. A plausible explanation, however, may be found in the theological imperative suggested by an earlier text, De pot., q. 2, a. 2, where Aquinas identifies the divine nature as the principle of generation. The more nuanced position in the Summa appears to be a deliberate effort to ground divine operations firmly in the divine nature. By doing so, Aquinas can more robustly affirm that the Son’s inability to generate does not entail less power, since he—sharing the same divine nature—possesses the same omnipotence as the Father.

5. The Unity and Order of Divine Power

This section examines Aquinas’s inquiry into the relationship between God’s potentia generandi and potentia creandi. Are they the same power or two different powers? Is there an order of priority between them?

5.1. Super Sent. I, d. 7, q. 1, a. 3

In Super Sent. I, d. 7, q. 1, a. 3, Aquinas establishes the primacy of generation while maintaining the unity of God’s power. The relationship between potentia generandi and potentia creandi changes depending on the perspective from which they are viewed. When considered from their origin—the singular, undivided divine essence—they are not two separate powers, but are “numerically one power” (una numero potentia), flowing from the single wellspring of divine being. From this vantage point, there is no order or priority, only unity. When considered in relation to the acts they produce (that is, in relation to their respective operations), however, these powers become distinct in our understanding and fall into a clear hierarchy. Because the act of generation is an eternal, ad intra act and the act of creating is a temporal, ad extra one, potentia generandi is understood to be prior to potentia creandi. God’s power, in sum, is both one (in its essence) and ordered (in its operations).

The reply to the fourth objection in this article reveals a further nuance. The objection argues that what is common (the divine essence and its creative power, shared by all three persons) must be prior to what is proper (the act of generation, which is exclusive to the Father). Aquinas refutes this with a subtle clarification: while the divine essence in itself is conceptually prior to the persons, the divine essence as it relates to creatures is conceptually posterior to the personal properties that constitute the inner life of God. In other words, the fecundity of the inner-Trinitarian life is presented as more fundamental than the power to create the universe.

5.2. De pot., q. 2, a. 6; q. 3, a. 16

In De pot., q. 2, a. 6, co., and similarly in De pot., q. 3, a. 16, ad 9, Aquinas affirms that potentia generandi and potentia creandi are one and the same power, but they differ in their respect to their distinct acts. To understand this, Aquinas conceptually divides a power into two aspects. The first is the substance of the power (substantia potentiae, to borrow his expression from De pot., q. 2, a. 6, ad 3). In God, since power is identical with the divine essence, there can only be one such substantial power. On this level, potentia generandi and potentia creandi are absolutely one and the same, not merely univocal (De pot., q. 2, a. 6, ad 3; cf. Super Sent. I, d. 7, q. 1, a. 3, co.). The second aspect is the respect to diverse acts (respectus ad actus diversos), which is the ordering or direction of that one power toward a specific action. It is on this level that a distinction arises: potentia creandi has a respect to an essential act (creation), which is common to all three persons, whereas potentia generandi has a respect to a notional act (generation), which is proper to the person of the Father alone. On this level, potentia generandi is prior to potentia creandi, just as generation is prior to creation.

This solution is grounded in divine simplicity. Aquinas rejects any theory that would multiply absolute realities in God, such as positing a separate personal being alongside the essential being. Since there is only one divine essence, and power is identical with that essence, there can only be one divine power. Any distinction made cannot be a real division in God himself, but must be a distinction of reason, based on the different ways this one power relates to different kinds of acts.

Aquinas’s replies to several objections further illuminate his position by showing how this single power can be the source of different kinds of actions. First, an act can proceed from the same power either by natural inclination (as in generation) or by command of the will (as in creation). This does not necessitate two separate powers, just as the human intellect can be moved to different acts by nature (e.g., understanding first principles) or by will (e.g., believing) (De pot., q. 2, a. 6, ad 1). Second, Aquinas argues that the more perfect and powerful a faculty is, the more unified it is. Human senses are many and distinct, while imagination is a single power covering all sensible objects. The divine power, being supremely perfect, is maximally unified and is not divided by the multiplicity of its effects (De pot., q. 2, a. 6, ad 2).

In conclusion, there is one infinite divine power—which is the divine essence—that is conceived of differently according to the different relations it has to its effects: one relation to the immanent, personal act of generation, and another relation to the external, essential act of creation.

In De pot., q. 3, a. 16, ad 9, Aquinas similarly maintains that while potentia generandi and potentia creandi are, in reality, one and the same power in God, they are nevertheless distinguished by the different respect or relationship that each connotes. He specifies that potentia generandi has a respect to that which proceeds by nature, and for this reason, its product must necessarily be one. Potentia creandi, on the other hand, implies a respect to that which proceeds from the will, and hence its product is not necessarily singular, but can be multiple.

5.3. Development of Doctrine

Across the texts analyzed in this section, Aquinas consistently affirms that potentia generandi and potentia creandi are one and the same power when the substance of the power itself is considered, but that an order of priority exists between them when the divine power is considered in its relation to distinct acts.

Despite the coherence in their conclusions, the argument in De pot., q. 2, a. 6, co., when compared to the exposition in Super Sent. I, d. 7, q. 1, a. 3, is more explicitly grounded in divine simplicity. This emphasis appears to be motivated by a polemical context surrounding the opinion of certain theologians (quidam). As Aquinas notes, “it must not be conceded that anything absolute in the divine is multiplied, as some [quidam] say, that in the divine there is a twofold being, essential and personal” (De pot., q. 2, a. 6, co.). This grounding in divine simplicity reinforces Aquinas’s own position, which had remained stable since his early academic career as a commentator on the Sentences.

6. Potentia Generandi in the Son

This section addresses the question of whether the Son possesses potentia generandi—that is, whether the Son can generate another son.

6.1. Super Sent. I, d. 7, q. 2, a. 1

This section tackles a seemingly paradoxical question raised in Super Sent. I, d. 7, q. 2, a. 1: Does the Son possess potentia generandi? Given that generation is the unique act of the Father, attributing this power to the Son appears contradictory. Aquinas’s solution rests upon demonstrating that the term potentia generandi is ambiguous. He argues that its meaning changes depending on the grammatical sense of the gerund generandi, a distinction that allows him to affirm that the Son has this power while denying any heretical implications.

He identifies three senses of potentia generandi in this article, an enumeration he would later present again without modification in De pot., q. 2, a. 4, ad 15.

The impersonal sense: The power by which the event of generation takes place. This power is the divine essence itself (cf. Super Sent. I, d. 7, q. 2, a. 1, ad 1). Since the Son fully possesses the divine essence, he possesses the power by which he is generated. This sense is applicable to the Son.

The active sense: The power to actively generate another. This is the unique role of the Father, defined by the personal property of paternity. This sense does not apply to the Son.

The passive sense: The power to be generated. This is the unique role of the Son, defined by the personal property of filiation. Aquinas asserts that this is the same power, i.e., the divine essence, that is in the Father, but viewed from the perspective of the one receiving, not the one giving.

The foundation for this entire argument is the doctrine that potentia generandi is the single divine essence. This one essence, when viewed through the relational lens of paternity, is actively generative; when viewed through the lens of filiation, it is passively generated.

The reply to the fourth objection adds a significant clarification, explaining why power (potentia) can be tied to a specific person in a way that knowledge (scientia) and will (voluntas) cannot. Knowledge and will, Aquinas observes, are principles of God’s ad extra acts, such as creating. Because creation proceeds in the manner of art, it is an act of the divine intellect and will, which are common to all three persons acting ad extra as one principle. Power, however, is also the principle of God’s internal act, generation. Because generation proceeds “by way of nature,” it is directly linked to the constitution of the persons. Therefore, the concept of power is more intimately connected to the personal distinctions and can be “drawn to the personal” (potest trahi ad personale) in a way that knowledge and will cannot when discussing the inner life of God (Super Sent. I, d. 7, q. 2, a. 1, ad 4).

In conclusion, by parsing the language of power, Aquinas shows how one can affirm the presence of potentia generandi in the Son without infringing upon the Father’s unique role as the sole principle of generation. He thus affirms both the unity of the divine essence and the real, relational distinctions of the persons.

6.2. Super Sent. I, d. 7, q. 2, a. 2

Super Sent. I, d. 7, q. 2, a. 2, provides a decisive argument against the possibility of the Son generating another son. This argument also serves as a confirmation of Aquinas’s stance, examined in the previous section, that potentia generandi can be attributed to the Son only in its impersonal and passive senses, not in its active sense.