Unveiling the Interplay Between Religiosity, Faith-Based Tourism, and Social Attitudes: Examining Generation Z in a Postsecular Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Religiosity and Religious Tourism in a Postsecular Era

1.2. Polish Context: Current Transformations in Religiosity

1.3. Generation Z—Digital Natives: Transforming Identity, Faith, and Travel Trends

- -

- Digital immersion: growing up in an always online environment, Generation Z is deeply embedded in social media and streaming platforms (Twenge et al. 2012), which raises concerns about self-awareness and mental well-being due to constant peer surveillance (Madden et al. 2013).

- -

- Historical imprint: shaped by major global events, including the 9/11 attacks, the 2007–2008 financial crisis, and the COVID-19 pandemic (Tapscott 2009; Turner 2015), which have influenced collective consciousness and risk perception.

- -

- Education and career anxiety: highly educated and pragmatic in career planning, yet increasingly worried about academic performance and job prospects (Adelantado-Renau et al. 2019).

- -

- Mental health vulnerability: more susceptible to anxiety, insomnia, and cognitive disorders, while also demonstrating greater awareness of these issues (Twenge et al. 2019), with a heightened sense of nostalgia potentially linked to digital media consumption and sociopolitical instability (Burrows 2022).

- -

- Progressive engagement and social responsibility: defined by a liberal outlook and active participation in cultural and identity debates (Coyette et al. 2015), Generation Z prioritizes environmental sustainability, ethical consumption (Puiu et al. 2022), and social justice movements focused on inequality and climate change (Tapscott 2009).

- -

- Declining religious affiliation but sustained spiritual openness: the least religiously affiliated generation, yet many embrace non-institutional beliefs, spirituality, and alternative religious expressions (Cox 2022; Manalang 2021). Globally, only 42% consider faith important, whereas 39% view it as irrelevant. Secularization trends are particularly prevalent in Europe (46%), Australasia (50%), and the United States (36%) (Hackett et al. 2018). Digitalization plays a central role in shaping young spiritual experiences, yet it remains underexplored. Social media platforms like YouTube, TikTok, and Instagram increasingly mediate spiritual engagement, providing access to traditional religious content and alternative practices (Campbell and Tsuria 2021). Importantly, these online practices do not remain confined to the digital realm but actively influence offline behaviors, including travel choices. Digital exposure to pilgrimage vlogs, influencer-led retreats, and online faith communities increasingly motivates Generation Z to engage in physical forms of religious and spiritual tourism, illustrating a reciprocal online–offline dynamic (Campbell and Tsuria 2021; Haddouche and Salomone 2018).

1.4. Generation Z as Spiritual and Religious Tourists: The Research Gap

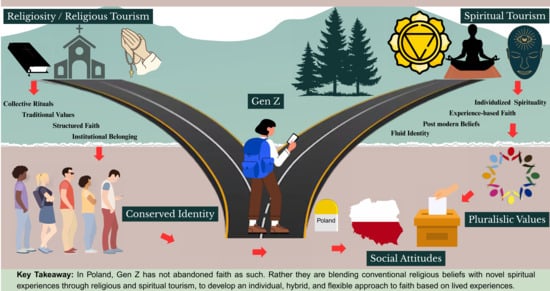

- Define the characteristics and changes of religiosity components (believing, belonging, and behaving, using Davie’s 2006) analytical framework,

- Identify key attributes of religious and spiritual tourism participation

- Analyse social attitudes toward religiosity

- Examine interrelations between religiosity components, religious and spiritual tourism participation, and social attitudes

- Explore variations in these relationships across sociodemographic factors, within broader context of sociocultural shifts.

2. Results

2.1. Components of Religiosity and Temporal Change

2.2. Associations Between Sociodemographic Characteristics and Religious Components

2.3. Patterns and Determinants of Religious and Spiritual Tourism

2.4. Perception of the Visited Place

2.5. Motivations for Religious and Spiritual Tourism

2.6. Sociodemographic Correlates of Religious and Spiritual Tourism

2.7. Interdependencies of the Studied Attributes of Generation Z

2.7.1. Religiosity and Social Attitudes

2.7.2. Components of Religiosity and Religious and Spiritual Tourism

2.7.3. Religious and Spiritual Tourism and Social Attitudes

3. Discussion

3.1. Patterns of Religiosity Among Generation Z

3.2. Religiosity, National Identity, and Social Attitudes

3.3. From Institutionalized Religion to Individualized Spirituality

3.4. Religious Engagement, Tourism, and Social Attitudes: Institutional and Personalized Faith in Motion

3.5. Religious and Spiritual Tourism as a Postsecular Experience

3.6. Faith in the Digital Age: Generation Z, Religious Engagement, and Mobility

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adelantado-Renau, Mireia, Diego Moliner-Urdiales, Iván Cavero-Redondo, Maria Reyes Beltran-Valls, Vicente Martínez-Vizcaíno, and Celia Álvarez-Bueno. 2019. Association Between Screen Media Use and Academic Performance Among Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Pediatrics 173: 1058–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammerman, Nancy T. 2013. Spiritual but Not Religious? Beyond Binary Choices in The Study of Religion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52: 258–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltescu, Codruta. 2019. Elements of Tourism Consumer Behaviour of Generation Z. Bulletin of the Transylvania University of Brasov, Economic Sciences 12: 63–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaumont, Justin, Klaus Eder, and Eduardo Mendieta. 2020. Reflexive Secularization? Concepts, Processes, and Antagonisms of Post-Secularity. European Journal of Social Theory 23: 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhassen, Yaniv, Kellee Caton, and William P. Stewart. 2008. The Search for Authenticity in Pilgrimage Experience. Annals of Tourism Research 35: 668–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentzen, Jeanet Sinding. 2021. In Crisis, We Pray: Religiosity and the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 192: 541–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, Peter L. 1967. The Sacred Canopy: Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion. Garden City: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Peter L. 2014. The Many Altars of Modernity: Toward a Paradigm for Religion in a Pluralist Age. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Bergler, Thomas E. 2020. Generation Z and Spiritual Maturity. Christian Education Journal: Research on Educational Ministry 17: 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilska-Wodecka, Elżbieta. 2005. Poland: Post-Communist Religious Revival. In The Changing Religious Landscape of Europe. Edited by Hans Knippenberg. Amsterdam: Het Spinhuis, pp. 120–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bilska-Wodecka, Elżbieta. 2009. Secularization and Sacralization: New Polarization of the Polish Religious Landscape in the Context of Globalization and European Integration. Acta Universitatis Carolinae 44: 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boguszewski, Rafał, Marta Makowska, Michał Bożewicz, and Magdalena Podkowińska. 2020. The COVID-19 Pandemic’s Impact on Religiosity in Poland. Religions 11: 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bora, Duygu, and Betül Çetin. 2023. Generations Y and Z’s Position in Faith Tourism. In Anatolian Landscape and Faith Tourism: Ancient Times to Present. Edited by Muharrem Tuna, Özlem Köroğlu, Gamze Kaya, Eda Hazarhun and Nuray Yıldız. Ankara: Detay Anatolia Akademik Yayıncılık, pp. 310–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bożewicz, Michał. 2022. Changes in Poles’ religiosity after the pandemic. In Sekularyzacja po polsku. Edited by Mirosława Grabowska. Warsaw: Public Opinion Research Center, pp. 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Burrows, Sam. 2022. Nostalgia, Gen Z, and the Return of History. Christian Teachers Journal 30: 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Heidi A., and Ruth Tsuria, eds. 2021. Digital Religion: Understanding Religious Practice in Digital Media. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, José. 2006. Religion, European Secular Identities, and European Integration. In Religion in an Expanding Europe. Edited by Timothy A. Byrnes and Peter J. Katzenstein. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 65–92. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, José. 2011. Cosmopolitanism, the Clash of Civilizations and Multiple Modernities. Current Sociology 59: 252–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBOS. 2021. The Religiosity of Young People in the Context of Society. Warsaw: Public Opinion Research Center (CBOS). Available online: https://www.cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2021/K_144_21.PDF (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Cheong, Pauline Hope, Peter Fischer-Nielsen, Stefan Gelfgren, and Charles Ess, eds. 2012. Digital Religion, Social Media, and Culture: Perspectives, Practices, and Futures. New York: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Erik. 1979. A Phenomenology of Tourist Experiences. Sociology 13: 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins-Kreiner, Noga. 2010. Researching Pilgrimage: Continuity and Transformations. Annals of Tourism Research 37: 440–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins-Kreiner, Noga. 2019. Pilgrimage Tourism—Past, Present, and Future Rejuvenation: A Perspective Article. Tourism Review 75: 145–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooperman, Alan, Neha Sahgal, and Anna Schiller. 2017. Religious Belief and National Belonging in Central and Eastern Europe. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2017/05/CEUP-FULL-REPORT.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Cox, Daniel A. 2022. Generation Z and the Future of Faith in America. Washington, DC: Survey Center on American Life. Available online: https://www.americansurveycenter.org/research/generation-z-future-of-faith/ (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Coyette, Catherine, Isabelle Fiasse, Annika Johansson, Fabienne Montaigne, and Helene Strandell. 2015. Being Young in Europe Today. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3217494/6776245/KS-05-14-031-EN-N.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Davie, Grace. 2006. Religion in Europe in the 21st Century: The Factors to Take Into Account. European Journal of Sociology 47: 271–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davie, Grace, and Erin K. Wilson. 2019. Religion in European society: The Factors to Take into Account. In Religion and European Society: A Primer. Edited by Benjamin Schewel and Erin K. Wilson. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Dimock, Michael. 2019. Defining Generations: Where Millennials End, and Generation Z Begins. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Dobbelaere, Karel. 1981. Secularization: A Multi-Dimensional Concept. Current Sociology 29: 3–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faith-Based Tourism Market Outlook. 2023. Delaware: Future Market Insights.

- Farias, Miguel, Thomas J. Coleman, III, James E. Bartlett, Lluís Oviedo, Pedro Soares, Tiago Santos, and María del Carmen Bas. 2019. Atheists on the Santiago Way: Examining Motivations to go on Pilgrimage. Sociology of Religion 80: 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-del Junco, Javier, Eva M. Sánchez-Teba, Mercedes Rodríguez-Fernández, and Isabel Gallardo-Sánchez. 2021. The Practice of Religious Tourism Among Generation Z’s Higher Education Students. Education Sciences 11: 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golan, Oren, and Marco Martini. 2022. Sacred Cyberspaces: Catholicism, New Media, and the Religious Experience. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gökarıksel, Banu. 2009. Beyond the Officially Sacred: Religion, Secularism, and the Body in the Production of Subjectivity. Social & Cultural Geography 10: 657–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzymała-Busse, Anna. 2019. Religious Nationalism and Religious Influence. In Oxford Research Encyclopaedia of Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habermas, Jürgen. 2006. Religion in the Public Sphere. European Journal of Philosophy 14: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, Conrad, Stephanie Kramer, and Anna Schiller. 2018. The Age Gap in Religion Around the World. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Haddouche, Houda, and Christian Salomone. 2018. Generation Z and the Tourist Experience: Tourist Stories and Use of Social Networks. Journal of Tourism Futures 4: 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henkel, Reinhard. 2014. The Changing Religious Space of Large Western European Cities. Geographical Studies 137: 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervieu-Léger, Danièle. 2000. Religion as a Chain of Memory. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hoover, Stewart M. 1997. The Media and Male Identity: Audience Research in Media, Religion, and Culture. In Rethinking Media, Religion, and Culture. Edited by Stewart M. Hoover and Knut Lundby. London: Sage, pp. 295–305. [Google Scholar]

- Jonason, Peter K., Marcin Zajenkowski, Kinga Szymaniak, and Maria Leniarska. 2022. Attitudes Towards Poland’s Ban on Abortion: Religiousness, Morality, and Situational Affordances. Personality and Individual Differences 184: 111229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, Suzanne R. 2005. Consuming Visions: Mass Culture and the Lourdes Shrine. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, Lily. 2010. Global Shifts, Theoretical Shift: Changing Geographies of Religion. Progress in Human Geography 34: 755–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kościelniak, Maciej, Agnieszka Bojanowska, and Agata Gąsiorowska. 2022. Religiosity Decline in Europe: Age, Generation, and the Mediating Role of Shifting Human Values. Journal of Religion and Health 63: 1091–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liro, Justyna. 2018. Visitors’ Diversified Motivations and Behavior: The Case of the Pilgrimage Center in Krakow (Poland). Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 15: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liro, Justyna. 2021. Visitors’ Motivations and Behaviours at Pilgrimage Centres: Push and Pull Perspectives. Journal of Heritage Tourism 16: 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liro, Justyna. 2024. The Interdependencies of Religious Tourists’ Attributes and Tourist Satisfaction: An in-depth View on Religious Tourism in the Light of Contemporary Socio-Cultural Changes. Current Issues in Tourism 27: 356–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liro, Justyna, Elżbieta Bilska-Wodecka, Magdalena Kubal-Czerwińska, Aneta Pawłowska-Legwand, Izabela Sołjan, and Anna Zielonka. 2024. The Interplay of Religiosity, Religious and Spiritual Tourism, and Social Attitudes: A Case Study of Polish Young Adults (Generation Z). Paper presented at the International Conference Earth as a Human-Environmental System: Challenges and Dynamics, Kraków, Poland, May 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liro, Justyna, and Sabrina Meneghello. 2025. Understanding Contemporary Religious Tourism through the Lens of the Experience Economy Approach. In Creating the Sacred Landscape: Pilgrimages and Ritual Practices. Edited by Darius Liutikas. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- MacCannell, Dean. 1973. Staged Authenticity: Arrangements of Social Space in Tourist Settings. American Journal of Sociology 79: 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, Mary, Amanda Lenhart, Sandra Cortesi, Urs Gasser, Maeve Duggan, Aaron Smith, and Mariya Beaton. 2013. Teens, Social Media, and Privacy. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Manalang, Aprilfaye T. T. 2021. Generation Z, minority Millennials, and disaffiliation from religious communities: Not belonging and the cultural cost of unbelief. Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion 17: 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Mannheim, Karl. 1952. The Problem of Generations. In Essays on the Sociology of Knowledge. Edited by Paul Kecskemeti. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, pp. 276–322. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, Christel J. 2019. Gen Z is the Least Religious Generation: Here’s Why That Could Be a Good Thing. Pacific Standard, May 6. Available online: https://psmag.com/ideas/gen-z-is-the-least-religious-generation-heres-why-that-could-be-a-good-thing (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Mariański, Janusz. 2006. Polish Catholicism—Continuity and Change: A Sociological Study. Lublin: KUL Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Lee J., and Wei Lu. 2018. Gen Z Is Set to Outnumber Millennials Within a Year. Bloomberg, August 20. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-08-20/gen-z-to-outnumber-millennials-within-a-year-demographic-trends (accessed on 20 August 2018).

- Müller, Olaf. 2011. Secularization, Individualization, or (Re)Vitalization? The State and Development of Churchliness and Religiosity in Post-Communist Central and Eastern Europe. Religion and Society in Central and Eastern Europe 4: 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, Mats, and Mikael Tesfahuney. 2017. The Post-Secular Tourist: Re-Thinking Pilgrimage Tourism. Tourist Studies 18: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIQ, and World Data Lab. 2024. Spend Z: A Global Report. NIQ. Available online: https://nielseniq.com/global/en/insights/report/2024/spend-z/ (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Norman, Alex. 2011. Spiritual Tourism: Travel and Religious Practice in Western Society. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. 2004. Sacred and Secular: Religion and Politics Worldwide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Palfrey, John, and Urs Gasser. 2008. Born Digital. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paterson, Jessica, and Andrew J. Francis. 2017. Influence of Religiosity on Self-Reported Response to Psychological Therapies. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 20: 428–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B. Joseph, and James H. Gilmore. 1998. Welcome to the Experience Economy. Harvard Business Review 76: 97–105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Polok, Grzegorz, and Andrzej Szromek. 2024. Religious and Moral Attitudes of Catholics from Generation Z. Religions 15: 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popșa, Raluca Elena. 2024. Exploring the Generation Z Travel Trends and Behavior. Studies in Business and Economics 19: 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prensky, Marc. 2001. Digital Game-Based Learning. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Puiu, Silvia, Liliana Velea, Mihaela Tinca Udriștioiu, and Alessandro Gallo. 2022. A Behavioral Approach to the Tourism Consumer Decisions of Generation Z. Behavioral Sciences 12: 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, Razaq, and Kevin Griffin. 2017. Conflicts, Religion and Culture in Tourism. Wallingford and Boston: CABI. [Google Scholar]

- Saroglou, Vassilis. 2002. Religion and the Five Factors of Personality: A Meta-Analytic Review. Personality and Individual Differences 32: 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sołjan, Izabela, and Justyna Liro. 2022. The Changing Roman Catholic Pilgrimage Centers in Europe in the Context of Contemporary Socio-Cultural Changes. Social & Cultural Geography 23: 376–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Poland. 2021. National Population and Housing Census 2021. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/en/national-census/national-population-and-housing-census-2021/final-results-of-the-national-population-and-housing-census-2021/ (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Statistics Poland. 2024. Average Monthly Gross Wages and Salaries in the National Economy in 2023. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/en/latest-statistical-news/communications-and-announcements/list-of-communiques-and-announcements/average-monthly-gross-wage-and-salary-in-national-economy-in-2023%2C283%2C12.html (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Tapscott, Don. 2009. Grown Up Digital: How the Net Generation Is Changing Your World. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Paul, and Scott Keeter, eds. 2010. Millennials: A Portrait of Generation Next. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, Dallen J., and Daniel H. Olsen. 2006. Tourism, Religion and Spiritual Journeys. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Tomka, Miklós. 2011. Expanding Religion: Religious Revival in Post-Communist Central and Eastern Europe. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Anthony. 2015. Generation Z: Technology and Social Interest. Journal of Individual Psychology 71: 103–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, Jean Marie, William Keith Campbell, and Elise Catherine Freeman. 2012. Generational Differences in Young Adults’ Life Goals, Concern for Others, and Civic Orientation, 1966–2009. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 102: 1045–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twenge, Jean M., Brittany Cooper, Jacob Thomas, Meghan E. Duffy, and Sarah G. Bunau. 2019. Age, Period, and Cohort Trends in Mood Disorder and Suicide-Related Outcomes in a Nationally Representative Dataset, 2005–2017. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 128: 185–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uysal, Duygu. 2022. Gen-Z’s Consumption Behaviors in Post-Pandemic Tourism Sector. Journal of Tourism, Leisure and Hospitality 4: 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cappellen, Patty, Mélanie Toth-Gauthier, Vassilis Saroglou, and Barbara L. Fredrickson. 2016. Religion and Well-Being: The Mediating Role of Positive Emotions. Journal of Happiness Studies 17: 485–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidenfeld, Adi, and Amos Ron. 2006. Religious needs in the hospitality industry. Tourism and Hospitality Research 6: 143–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, James Emery. 2017. Meet Generation Z. Grand Rapids: Baker Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Wohlrab-Sahr, Monika, and Marian Burchardt. 2012. Multiple Secularities: Toward a Cultural Sociology of Secular Modernities. Comparative Sociology 11: 875–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodhead, Linda, and Paul Heelas, eds. 2005. The Spirituality Revolution: Religion and Spirituality in Contemporary Society. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Jing, Jing Tang, and Ernest Agyeiwaah. 2023. I Had More Time to Listen to My Inner Voice: Zen Meditation Tourism for Generation Z. Tourist Studies 23: 293–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziebertz, Hans-Georg, and Ulrich Riegel. 2012. Die Post-Critical Belief-Scale. Ein geeignetes Instrument zur Erfassung von Religiosität theologisch informierter Individuen? In Religiöser Pluralismus im Fokus quantitativer Religionsforschung. Edited by Detlef Pollack, Ingrid Tucci and Hans-Georg Ziebertz. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, pp. 39–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographics | % |

|---|---|

| Religious affiliation | |

| Roman Catholicism | 78.8 |

| atheism/agnosticism/nonaffiliated | 13.5 |

| other/no response | 7.7 |

| Education | |

| primary | 26.1 |

| secondary | 42.0 |

| technical/professional | 7.8 |

| university | 22.5 |

| other | 0.8 |

| no response | 0.8 |

| Place of residence | |

| village | 32.2 |

| Small town (<10,000) | 9.2 |

| City (10,000–100,000) | 19.0 |

| City (100,000–500,000) | 8.6 |

| City (>500,000) | 30.2 |

| no response | 0.8 |

| Employment status | |

| pupil | 34.5 |

| student | 37.3 |

| employed | 23.5 |

| unemployed | 1.2 |

| homemaker | 1.0 |

| retired | 0.2 |

| other | 1.0 |

| no response | 1.3 |

| Economic status * | |

| higher income | 48.0 |

| lower income | 11.2 |

| no response | 40.8 |

| Component | Women (n = 291) | Men (n = 210) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | U | Z | p | r | |

| a. belief in God/higher powers | 6.57 | 2.71 | 6.10 | 2.94 | 28,021.5 | −1.60 | 0.110 | 0.07 |

| b1. religious identity | 6.03 | 2.96 | 5.61 | 3.05 | 27,756.5 | −1.49 | 0.136 | 0.07 |

| b2. commitment to traditional religious values | 6.54 | 2.64 | 6.33 | 2.66 | 29,004.0 | −0.98 | 0.328 | 0.04 |

| c. participation in religious practices | 5.85 | 2.91 | 5.23 | 3.04 | 26,825.5 | −2.26 | 0.024 | 0.10 |

| Component | Education | Place of Residence | Sense of National Identity |

|---|---|---|---|

| a. belief in God/higher power | −0.04 | −0.15 ** | 0.30 *** |

| b1. religious identity | −0.05 | −0.10 * | 0.35 *** |

| b2. commitment to traditional religious values | −0.09 * | −0.16 *** | 0.33 *** |

| c. participation in religious practices | −0.13 ** | −0.16 *** | 0.33 *** |

| Component | Roman Catholics (n = 399) | Nonaffiliated (n = 69) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | U | Z | p | r | |

| a. belief in God/higher power | 7.15 | 2.36 | 3.10 | 2.36 | 3519.5 | −9.99 | <0.001 | 0.46 |

| b1. religious identity | 6.68 | 2.62 | 2.06 | 1.62 | 2189.5 | −11.22 | <0.001 | 0.52 |

| b2. commitment to traditional religious values | 7.07 | 2.27 | 3.52 | 2.52 | 4418.5 | −9.12 | <0.001 | 0.42 |

| c. participation in religious practices | 6.38 | 2.62 | 2.06 | 1.54 | 2603.5 | −10.75 | <0.001 | 0.50 |

| Roman Catholics (n = 399) | Nonaffiliated (n = 69) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| yes | 177 (44.4%) | 13 (18.8%) | χ2(2) = 16.29 |

| no | 210 (52.6%) | 54 (78.3%) | p < 0.001 |

| I don’t know | 12 (3.0%) | 2 (2.9%) | V = 0.19 |

| Primary | Secondary | Technical/Professional | University | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| yes | 8 (13.1%) | 34 (30.9%) | 9 (69.2%) | 18 (32.7%) | H(2) = 6.57 p = 0.037 |

| no | 43 (70.5%) | 71 (64.5%) | 4 (30.8%) | 34 (61.8%) | |

| I don’t know | 10 (16.4%) | 5 (4.5%) | 0 | 3 (5.5%) |

| Social Attitudes | a. Belief in God/Higher Power | b1. Religious Identity | b2. Commitment to Traditional Religious Values | c. Participation in Religious Practices |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| i. Faith and religious identity are not strongly correlated | −0.13 ** | −0.24 *** | −0.18 *** | −0.21 *** |

| ii. Faith does not require alignment with institutional practices | −0.05 | −0.14 ** | −0.09 * | −0.19 *** |

| iii. Personal beliefs and freedom of choice are central to religiosity | −0.16 *** | −0.21 *** | −0.15 *** | −0.17 *** |

| iv. My faith is a personal choice rather than a result of family upbringing | −0.15 *** | −0.19 *** | −0.23 *** | −0.21 *** |

| v. My faith has significantly declined in recent years | −0.43 *** | −0.43 *** | −0.23 *** | −0.42 *** |

| vi. Religious institutions must address moral and social issues publicly | 0.31 *** | 0.33 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.33 *** |

| vii. Religious institutions should also engage in political discourse | 0.16 *** | 0.21 *** | 0.13 ** | 0.22 *** |

| viii. Church involvement in public life strengthens faith and religious identity | 0.35 *** | 0.39 *** | 0.32 *** | 0.35 *** |

| ix. Church involvement strengthens national identity | 0.31 *** | 0.37 *** | 0.35 *** | 0.37 *** |

| x. Catholicism is central to Polish national identity | 0.46 *** | 0.48 *** | 0.43 *** | 0.42 *** |

| Religious Tourism | Spiritual Tourism | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 202) | No (n = 291) | Yes (n = 69) | No (n = 155) | |||||||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | U | Z | p | r | M | SD | M | SD | U | Z | p | r | |

| a. belief in God/higher power | 7.40 | 2.60 | 5.59 | 2.79 | 18,305.5 | −7.18 | <0.001 | 0.32 | 7.83 | 2.41 | 5.70 | 2.88 | 2976.0 | −5.34 | <0.001 | 0.36 |

| b1. religious identity | 7.16 | 2.78 | 4.86 | 2.84 | 16,066.0 | −8.49 | <0.001 | 0.38 | 7.32 | 2.72 | 5.03 | 2.81 | 2844.5 | −5.45 | <0.001 | 0.37 |

| b2. commitment to traditional religious values | 7.27 | 2.39 | 5.81 | 2.72 | 20,040.5 | −6.06 | <0.001 | 0.27 | 7.22 | 2.42 | 6.09 | 2.73 | 3968.0 | −3.11 | 0.002 | 0.21 |

| c. participation in religious practices | 6.79 | 2.64 | 4.67 | 2.93 | 17,358.5 | −7.74 | <0.001 | 0.35 | 6.81 | 2.65 | 4.64 | 3.13 | 3303.0 | −4.61 | <0.001 | 0.31 |

| Religious Tourism | Spiritual Tourism | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 200) | No (n = 290) | Yes (n = 69) | No (n = 155) | |||||||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | U | Z | p | r | M | SD | M | SD | U | Z | p | r | |

| i. Faith and religious identity are not strongly correlated | 3.19 | 1.16 | 3.50 | 1.17 | 24,930.5 | −2.72 | 0.006 | 0.12 | 3.39 | 1.11 | 3.51 | 1.14 | 4994.0 | −0.82 | 0.415 | 0.05 |

| ii. Faith does not require alignment with institutional practices | 3.37 | 1.26 | 3.54 | 1.32 | 26,619.0 | −1.59 | 0.112 | 0.07 | 3.48 | 1.18 | 3.67 | 1.23 | 4768.5 | −1.34 | 0.181 | 0.09 |

| iii. Personal beliefs and freedom of choice are central to religiosity | 3.63 | 1.21 | 4.09 | 1.15 | 22,026.5 | −4.76 | <0.001 | 0.22 | 3.75 | 1.21 | 4.11 | 1.03 | 4479.5 | −2.05 | 0.040 | 0.14 |

| iv. My faith is a personal choice rather than a result of family upbringing | 2.18 | 1.35 | 2.51 | 1.43 | 25,143.0 | −2.55 | 0.011 | 0.12 | 2.01 | 1.32 | 2.17 | 1.41 | 5064.5 | −0.68 | 0.496 | 0.05 |

| v. My faith has significantly declined in recent years | 2.31 | 1.48 | 3.01 | 1.51 | 20,957.0 | −5.29 | <0.001 | 0.24 | 2.09 | 1.42 | 3.28 | 1.53 | 3032.0 | −5.19 | <0.001 | 0.35 |

| vi. Religious institutions must address moral and social issues publicly | 3.33 | 1.33 | 2.44 | 1.32 | 18,585.0 | −6.92 | <0.001 | 0.31 | 2.99 | 1.43 | 2.90 | 1.33 | 5177.5 | −0.39 | 0.698 | 0.03 |

| vii. Religious institutions should also engage in political discourse | 2.48 | 1.33 | 2.05 | 1.27 | 23,385.5 | −3.77 | <0.001 | 0.17 | 2.25 | 1.22 | 1.85 | 1.20 | 4182.5 | −2.83 | 0.005 | 0.19 |

| viii. Church involvement in public life strengthens faith and religious identity | 3.06 | 1.26 | 2.38 | 1.22 | 20,361.5 | −5.70 | <0.001 | 0.26 | 2.75 | 1.33 | 2.68 | 1.27 | 5205.5 | −0.33 | 0.745 | 0.02 |

| ix. Church involvement strengthens national identity | 2.85 | 1.22 | 2.33 | 1.22 | 22,163.0 | −4.52 | <0.001 | 0.20 | 2.54 | 1.26 | 2.32 | 1.13 | 4863.5 | −1.12 | 0.263 | 0.07 |

| x. Catholicism is central to Polish national identity | 3.56 | 1.29 | 2.81 | 1.34 | 13,147.5 | −5.50 | <0.001 | 0.28 | 3.16 | 1.38 | 2.95 | 1.39 | 4901.5 | −1.02 | 0.308 | 0.07 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liro, J.; Kubal-Czerwińska, M.; Pawłowska-Legwand, A.; Bilska-Wodecka, E.; Sołjan, I.; Meneghello, S.; Zielonka, A. Unveiling the Interplay Between Religiosity, Faith-Based Tourism, and Social Attitudes: Examining Generation Z in a Postsecular Context. Religions 2025, 16, 1325. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16101325

Liro J, Kubal-Czerwińska M, Pawłowska-Legwand A, Bilska-Wodecka E, Sołjan I, Meneghello S, Zielonka A. Unveiling the Interplay Between Religiosity, Faith-Based Tourism, and Social Attitudes: Examining Generation Z in a Postsecular Context. Religions. 2025; 16(10):1325. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16101325

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiro, Justyna, Magdalena Kubal-Czerwińska, Aneta Pawłowska-Legwand, Elżbieta Bilska-Wodecka, Izabela Sołjan, Sabrina Meneghello, and Anna Zielonka. 2025. "Unveiling the Interplay Between Religiosity, Faith-Based Tourism, and Social Attitudes: Examining Generation Z in a Postsecular Context" Religions 16, no. 10: 1325. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16101325

APA StyleLiro, J., Kubal-Czerwińska, M., Pawłowska-Legwand, A., Bilska-Wodecka, E., Sołjan, I., Meneghello, S., & Zielonka, A. (2025). Unveiling the Interplay Between Religiosity, Faith-Based Tourism, and Social Attitudes: Examining Generation Z in a Postsecular Context. Religions, 16(10), 1325. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16101325