Job Insecurity and Happiness Among Muslim Americans: Does the Moderating Role of Religious Involvement Differ by Gender?

Abstract

1. Introduction

Historical and Social Context

2. Theoretical and Empirical Background

2.1. Happiness

2.2. Happiness and Job Insecurity

2.3. Happiness and Religious Involvement

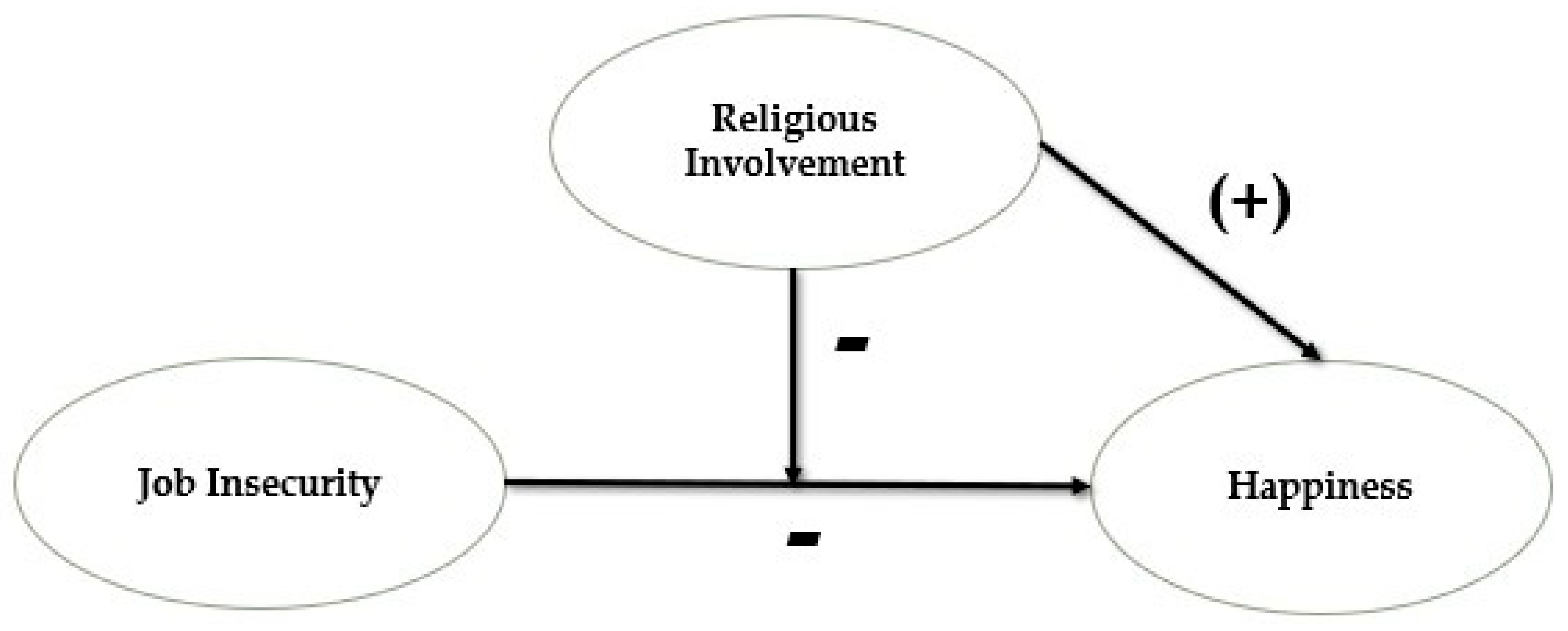

2.4. The Stress-Buffering Role of Religious Involvement

2.5. Gender and Religion

3. Conceptual Models

4. Methods

4.1. Data

4.2. Measures

4.2.1. Dependent Variable: Happiness

4.2.2. Independent Variables

4.2.3. Socio-Demographics

4.3. Analytic Strategies

5. Results

Ancillary Results

6. Discussion and Conclusions

7. Limitations and Future Research Avenues

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PSMAS | Pew Survey of Muslim American Study |

References

- Abdel-Khalek, Ahmed M. 2006. Happiness, Health, and Religiosity: Significant Relations. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 9: 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Khalek, Ahmed M. 2007. Religiosity, Happiness, Health, and Psychopathology in a Probability Sample of Muslim Adolescents. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 10: 571–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Khalek, Ahmed M. 2014. Religiosity and Well-being in a Muslim Context. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 24: 62–70. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Khalek, Ahmed M., and David Lester. 2013. Mental Health, Subjective Well-being, and Religiosity: Significant Associations in Kuwait and USA. Journal of Muslim Mental Health 7: 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Khalek, Ahmed M., and David Lester. 2017. The Association between Religiosity, Generalized Self-efficacy, Mental health, and Happiness in Arab College Students. Personality and Individual Differences 109: 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdo, Geneive. 2005. Islam in America: Separate but Unequal. The Washington Quarterly 28: 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu El-Haj, and Thea Renda. 2007. I Was Born Here, but My Home, It’s not Here: Educating for Democratic Citizenship in an Era of Transnational Migration and Global Conflict. Harvard Educational Review 77: 285–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo, Gabriel A., Christopher G. Ellison, and Xiaohe Xu. 2014. Is it Really Religion? Comparing the Main and Stress-buffering Effects of Religious and Secular Civic Engagement on Psychological Distress. Society and Mental Health 4: 111–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeel, Sheikh, and Misbah Shakir. 2025. Impact of Job Insecurity on Work-family Conflict: The Role of Job-related Anxiety and Insomnia. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research 18: 130–47. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, Shilpa, Judith Wright, Amy Morgan, George Patton, and Nicola Reavley. 2023. Religiosity and Spirituality in the Prevention and Management of Depression and Anxiety in Young People: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 23: 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ağılkaya Şahin, Zuhal. 2018a. Bridging Pastoral Psychology and Positive Psychology. Ilahiyat Studies—A Journal on Islamic and Religious Studies 9: 183–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ağılkaya Şahin, Zuhal. 2018b. Din ve Psikoloji Arasındaki Uuçurum Gerçekten Ne Kadar Derin? Psikoterapilerdeki Dini İzler [Psychology vs. Religion: How Deep is the Cliff Really? Traces of Religion in Psychotherapy]. Cumhuriyet İlahiyat Dergisi 22: 1607–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ağılkaya Şahin, Zuhal. 2024a. Islamic Practices as Psychotherapeutic Interventions. In Heartfulness: Islamic Spiritual Practices for Health and Wellbeing. Edited by Carrie M. York. Pakistan: Alkaram Press, pp. 52–83. [Google Scholar]

- Ağılkaya Şahin, Zuhal. 2024b. Psikoloji ve Psikoterapide Din, 2nd ed. Istanbul: Çamlıca Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, Sameera, and Linda A. Reddy. 2007. Understanding the Mental Health Needs of American Muslims: Recommendations and Considerations for Practice. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development 35: 207–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kuwari, Shaikha H. 2024. Arab Americans in the United States: Immigration, Culture, and Health. Singapore: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Al Rawi, Ahmed. 2024. Preserving Religious and Associational Freedoms: Unraveling the Chilling Effect of State Security Surveillance on American Muslims’ First Amendment Rights. Ph.D. dissertation, The Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman, Nancy T., ed. 2006. Everyday Religion: Observing Modern Religious Lives. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman, Nancy T. 2014. Finding Religion in Everyday Life. Sociology of Religion 75: 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Hongyu, Xiao Gu, Bojan Obrenovic, and Danijela Godinic. 2023. The Role of Jjob Insecurity, Social Media Exposure, and Job Stress in Predicting Anxiety among White-collar Employees. Psychology Research and Behavior Management 16: 3303–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angner, Erik, Michael J. Miller, Midge N. Ray, Kenneth G. Saag, and Jeroan J. Allison. 2010. Health literacy and happiness: A community-based study. Social Indicator Research 95: 325–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anlı, Gazanfer. 2025. Positive Psychology Practices in Muslim Communities: A Systematic Review. Journal of Religion and Health 64: 3448–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyle, Michael. 2013. The Psychology of Happiness. Oxfordshire: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Argyle, Michael, and Maryanne Martin. 1991. The Psychological Causes of Happiness. In Subjective Well-Being: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Edited by Fritz Strack, Michael Argyle and Norbert Schwarz. Oxford: Pergamon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Argyle, Michael, and Peter Hills. 2000. Religious Experiences and Their Relations with Happiness and Personality. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 10: 157–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydogdu, Ramazan, Muhammed Yildiz, and Uğur Orak. 2021. Religion and Wellbeing: Devotion, Happiness and Life Satisfaction in Turkey. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 24: 961–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayub, Nadia, Shahid Iqbal, and Emaan Rangoonwala. 2022. Religious Identity and Psychological Well-being: Gender Differences among Muslim Adolescents. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research 37: 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagby, Ihsa. 2020. The American Mosque 2020: Growing and Evolving. Washington, DC: Institute of Social Policy and Understanding. [Google Scholar]

- Bassioni, Ramy, and Kimberly Langrehr. 2021. Effects of Religious Discrimination and Fear for Safety on Life Satisfaction for Muslim Americans. Journal of Muslim Mental Health 15: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basyouni, Sawzan Sadaqa, and Mogeda El Sayed El Keshky. 2021. Job Insecurity, Work-related Flow, and Financial Anxiety in the Midst of COVID-19 Pandemic and Economic Downturn. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 632265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchflower, David G., and Andrew J. Oswald. 2004. Well-being Over Time in Britain and the USA. Journal of Public Economics 88: 1359–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodman, Herbert L., and Nayyira Tawḥīdī. 1998. Women in Muslim Societies: Diversity Within Unity. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, Christopher S., Terrence D. Hill, Amy M. Burdette, Krysia N. Mossakowski, and Robert J. Johnson. 2020. Religious Attendance and Social Support: Integration or Selection? Review of Religious Research 62: 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, Matt, and Christopher. G. Ellison. 2010. Financial Hardship and Psychological Distress: Exploring the Buffering Effects of Religion. Social Science & Medicine 71: 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradshaw, Matt, Blake V. Kent, Charlotte vanWitvliet Oyen, Byron Johnson, Sung Joon Jang, and Joseph Leman. 2022. Perceptions of Accountability to God and Psychological Well-being among US Adults. Journal of Religion and Health 61: 327–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgard, Sarah A., Jennie E. Brand, and James S. House. 2009. Perceived Job Insecurity and Worker Health in the United States. Social Science & Medicine 69: 777–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byng, Michelle D. 2008. Complex Inequalities: The Case of Muslim Americans after 9/11. American Behavioral Scientist 51: 659–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callea, Antonino, Alessandro Lo Presti, Saija Mauno, and Flavio Urbini. 2019. The Associations of Quantitative/Qualitative Job Insecurity and Well-being: The Role of Self-esteem. International Journal of Stress Management 26: 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Lei, and Jia Xue. 2023. Childhood Abuse and Substance Use in Canada: Does Religion Ameliorate or Intensify That Association? Journal of Substance Use 28: 912–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, Mark. 2004. Congregations in America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chirumbolo, Antonio, Antonino Callea, and Flavio Urbini. 2022. Living in Liquid Times: The Relationships among Job Insecurity, Life Uncertainty, and Psychosocial Well-Being. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 15225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Adam B., and Kathyryn A. Johnson. 2017. The Relation between Religion and Well-being. Applied Research in Quality of Life 12: 533–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, Edward E., IV. 2009. Muslims in America: A Short History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dana, Karam, Matt A. Barreto, and Kassra A. Oskooii. 2011. Mosques as American Institutions: Mosque Attendance, Religiosity and Integration into the Political System Among American Muslims. Religions 2: 504–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demorest, Amy P. 2019. Happiness, Love, and Compassion as Antidotes for Anxiety. The Journal of Positive Psychology 15: 438–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Witte, Hans, Jaco Pienaar, and Nele De Cuyper. 2016. Review of 30 Years of Longitudinal Studies on the Association between Job Insecurity and Health and Well-being: Is There Causal Evidence? Australian Psychologist 51: 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Witte, Hans, Tinne Vander Elst, and Nele De Cuyper. 2015. Job insecurity, Health, and Well-being. In Sustainable Working Lives: Managing Work Transitions and Health Throughout the Life Course. Edited by Jukka Vuori, Roland A. Blonk and Richard H. Price. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 109–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, Ed. 2000. Subjective Well-being: The Science of Happiness and a Proposal for a National Index. American Psychologist 55: 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, Ed, and Micaela Y. Chan. 2011. Happy People Live Longer: Subjective Well-being Contributes to Health and Longevity. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being 3: 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Albert L. 1962. Reason and Emotion in Psychotherapy. Englewood: Lyle Stuart. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, Christopher G. 1991. Religious Involvement and Subjective Well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 32: 80–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, Christopher G., and Andrea K. Henderson. 2011. Religion and Mental Health: Through the Lens of the Stress Process. In Toward a Sociological Theory of Religion and Health. Edited by Anthony Blasi. Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, Christopher G., and Darren E. Sherkat. 1995. The “Semi-involuntary Institution” Revisited: Regional Variations in Church Participation among Black Americans. Social Forces 73: 1415–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, Christopher G., and Linda K. George. 1994. Religious Involvement, Social Ties, and Social Support in a Southeastern Community. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 33: 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, Christopher G., David A. Gay, and Thomas A. Glass. 1989. Does Religious Commitment Contribute to Individual Life Satisfaction? Social Forces 68: 100–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, Christopher G., Metin Guven, Reed T. DeAngelis, and Terrence D. Hill. 2023. Perceived Neighborhood Disorder, Self-esteem, and the Moderating Role of Religion. Review of Religious Research 65: 317–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraro, Kenneth F., and Jessica A. Kelley-Moore. 2000. Religious Consolation among Men and Women: Do Health Problems Spur Seeking? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 39: 220–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetter, Anna K., and Mindi N. Thompson. 2023. The Impact of Historical Loss on Native American College Students’ Mental Health: The Protective Role of Ethnic Identity. Journal of Counseling Psychology 70: 486–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flannelly, Kevin J. 2017. Religious Beliefs, Evolutionary Psychiatry, and Mental Health: Evolutionary Threat Assessment Systems Theory. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, Leslie J., and David Lester. 1997. Religion, Personality, and Happiness. Journal of Contemporary Religion 12: 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, Leslie J., Üzeyir Ok, and Mandy Robbins. 2017. Religion and Happiness: A Study among University Students in Turkey. Journal of Religion and Health 56: 1335–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freese, Jeremy. 2004. Risk Preferences and Gender Differences in Religiousness: Evidence from the World Values Survey. Review of Religious Research 46: 88–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, Bruno S., and Alois Stutzer. 2002. What Can Economists Learn from Happiness Research? Journal of Economic Literature 40: 402–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallup. 2009. Muslim Americans: A National Portrait. Washington, DC: Gallup Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gebert, Diether, Sabine Boerner, Eric Kearney, James E. King, Kai Zhang, Jr., and Linda J. Song. 2014. Expressing Religious Identities in the Workplace: Analyzing a Neglected Diversity Dimension. Human Relations 67: 543–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari, Azadeh, and Ayşe Çiftçi. 2010. Religiosity and Self-esteem of Muslim Immigrants to the United States: The Moderating Role of Perceived Discrimination. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 20: 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, Dennis. 2002. Muslim America Poll: Accounts of Anti-Muslim Discrimination. New York: Hamilton College and Zogby International. [Google Scholar]

- Grammich, Clifford, Kirk Hadaway, Richard Houseal, Dale E. Jones, Alexei Krindatch, Richie Stanley, and Richard H. Taylor. 2023. 2020 U.S. Religion Census: Religious Congregations & Adherents Study. Lenexa: Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies. [Google Scholar]

- Haddad, Y. Yvonne, and Jane I. Smith, eds. 1994. Muslim Communities in North America. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haddad, Yvonne Y., and Jane I. Smith. 2006. Muslim Women in America: The Challenge of Islamic Identity Today. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haniff, Ghulam M. 2003. The Muslim Community in America: A Brief Profile. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs 23: 303–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanslmaier, Michael. 2013. Crime, Fear and Subjective Well-being: How Victimization and Street Crime Affect Fear and Life Satisfaction. European Journal of Criminology 10: 515–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, Inam U., Dirk De Clercq, and Muhammad U. Azeem. 2022. Job Insecurity, Work-induced Mental Health Deprivation, and Timely Completion of Work Tasks. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 60: 405–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, Amber. 2004. Religion and Mental Health: The Case of American Muslims. Journal of Religion and Health 43: 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, Orestes P., and Kassandra K. Roeser. 2020. Happiness in Hard Times: Does Religion Buffer the Negative Effect of Unemployment on Happiness? Social Forces 99: 447–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaney, Catherine A., Barbara A. Israel, and James S. House. 1994. Chronic Job Insecurity among Automobile Workers: Effects on Job Satisfaction and Health. Social Science & Medicine 38: 1431–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedayat-Diba, Zari. 2014. Psychotherapy with Muslims. In Handbook of Psychotherapy and Religious Diversity, 2nd ed. Edited by P. Scott Richards and Allen E. Bergin. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, David R., Tarek Zidan, and Altaf Husain. 2015. Depression among Muslims in the United States: Examining the Role of Discrimination and Spirituality as Risk and Protective Factors. Social Work 61: 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, Mirya, and Erica Podrazik. 2018. Gender and Religiosity in the United States. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hout, Michael, and Orestes P. Hastings. 2014. Recession, Religion, and Happiness, 2006–2010. In Religion and Inequality in America: Research and Theory on Religion’s Role in Stratification. Edited by Lisa Keister and Darren Sherkat. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hur, Hyunkang. 2022. Job Security Matters: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of the Relationship between Job Security and Work Attitudes. Journal of Management & Organization 28: 925–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, Muhammad, and Jamal Badawi. 1993. Job Stress among Muslim Immigrants in North America: Moderating Effects of Religiosity. Stress Medicine 9: 145–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Yuri, David. A. Chiriboga, and Brent J. Small. 2008. Perceived Discrimination and Dsychological Well-being: The Mediating and Moderating Role of Sense of Control. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development 66: 213–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joelson, Lars, and Leif Wahlquist. 1987. The Psychological Meaning of Job Insecurity and Job Loss: Results of a Longitudinal Study. Social Science & Medicine 25: 179–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaca, Faruk. 2003. Dindarlığın Fonksiyonelliği Üzerine. Dini Araştırmalar 6: 75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Karaca, Faruk. 2020. Din Psikolojisi. Trabzon: Eser Ofset Matbaacılık. [Google Scholar]

- Kaushal, Neeraj, Robert Kaestner, and Cordelia Reimers. 2007. Labor Market Effects of September 11th on Arab and Muslim Residents of the United States. Journal of Human Resources 42: 275–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Mussarat J. 2014. Construction of Muslim Religiosity Scale. Islamic Studies 53: 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, Harold G., Michael E. McCullough, and David B. Larson. 2001. Handbook of Religion and Health. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Konow, James, and Joseph Earley. 2008. The Hedonistic Paradox: Is Homo Economicus Happier? Journal of Public Economics 92: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, Neal. 1995. Religiosity and Self-esteem among Older Adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 50: 236–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, Neal. 2006. Exploring the Stress-buffering Effects of Church-based and Secular Social Support on Self-rated Health in Late Life. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences 61B: S35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, Neal, Gary Ironson, and Peter Hill. 2018. Religious Involvement and Happiness: Assessing the Mediating Role of Compassion and Helping Others. The Journal of Social Psychology 158: 256–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhnert, Karl W., Ronald R. Sims, and Mary A. Lahey. 1989. The Relationship between Job Security and Employee Health. Group & Organization Studies 14: 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laher, Sumaya, and Sumayyah Khan. 2011. Exploring the Influence of Islam on the Perceptions of Mental Illness of Volunteers in a Johannesburg Community-based Organisation. Psychology and Developing Societies 23: 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, Jack, Wen Fan, and Phillis Moen. 2014. Is Insecurity Worse for Well-being in Turbulent Times? Mental Health in Context. Society and Mental Health 4: 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Låstad, Lena, Anna S. Tanimoto, and Petra Lindfors. 2021. How Do Job Insecurity Profiles Correspond to Employee Experiences of Work-home Interference, Self-rated Health, and Psychological Well-being? Journal of Occupational Health 63: e12253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Thao N., Mary H. Lai, and Judy Wallen. 2009. Multiculturalism and Subjective Happiness as Mediated by Cultural and Relational Variables. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology 15: 303–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, Jeffrey S., and Robert J. Taylor. 1998. Panel Analyses of Religious Involvement and Well-being in African Americans: Contemporaneous vs. Longitudinal Effects. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 37: 695–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Ziyi, Hao-Yun Zou, Hai-Jiang Wang, Lixin Jiang, Yan Tu, and Yi Zhao. 2023. Qualitative Job Insecurity, Negative Work-related Affect and Work-to-family Conflict: The Moderating Role of Core Self-evaluations. Journal of Career Development 50: 216–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Chaeyoon, and Robert D. Putnam. 2010. Religion, Social Networks, and Life Satisfaction. American Sociological Review 75: 914–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Charles E. 1994. The Black Muslims in America, 3rd ed. Grand Rapids: W. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Livengood, Jennifer S., and Monika Stodolska. 2004. The Effects of Discrimination and Constraints Negotiation on Leisure Behavior of American Muslims in the Post-September 11 America. Journal of Leisure Research 36: 183–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubomirsky, Sonja, and Heidi S. Lepper. 1999. A Measure of Subjective Happiness: Preliminary Reliability and Construct Validation. Social Indicators Research 46: 137–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, Annette, and Annmarie Cano. 2014. Introduction to the Special Section on Religion and Spirituality in Family Life: Pathways between Relational Spirituality, Family Relationships and Personal Well-being. Journal of Family Psychology 28: 735–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, Mary B. 2015. Perceived Discrimination of Muslims in Health Care. Journal of Muslim Mental Health 9: 41–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, Michael E., and Brian L. Willoughby. 2009. Religion and Self-regulation: A Review of the Evidence. Psychological Bulletin 135: 69–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Alan S., and John P. Hoffmann. 1995. Risk and Religion: An Explanation of Gender Differences in Religiosity. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 34: 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Alan S., and Rodney Stark. 2002. Gender and Religiousness: Can Socialization Explanations Be Saved? American Journal of Sociology 107: 1399–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Keith M. 2023. American Muslim Well-Being in the Era of Rising Islamophobia: Mediation Analysis of Muslim American Social Capital and Health. Ph.D. dissertation, Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, Besheer. 2025. How U.S. Muslims Compare with Other Americans Religiously and Demographically. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, June 18, Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2025/06/18/how-us-muslims-compare-with-other-americans-religiously-and-demographically/ (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Mohammed, Hassnaa. 2024. Toward a Holistic Study of Mosques in the US: A Critical Integrative Literature Review and Framework. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 92: 524–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, James D. 2003. A Formalization and Test of the Religious Economies Model. American Sociological Review 68: 782–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouzon, Dawne M., and Breanna D. Brock. 2022. Racial Discrimination, Discrimination-related Coping, and Mental Health among Older African Americans. Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics 41: 85–122. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, David. G. 2008. Religion and Human Flourishing. In The Science of Subjective Well-Being. Edited by M. Eid and R. J. Larsen. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, Ann W. 2020. Religion and Mental Health in Racial and Ethnic Minority Populations: A Review of the Literature. Innovation in Aging 4: igaa035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obrenovic, Bojan, Jianguo Du, Danijela Godinic, Mohammed Majdy M. Baslom, and Diana Tsoy. 2021. The Threat of COVID-19 and Job Insecurity Impact on Depression and Anxiety: An Empirical Study in the USA. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padela, Aasim I., and Michele Heisler. 2010. The Association of Perceived Abuse and Discrimination after September 11, 2001, with Psychological Distress, Level of Happiness, and Health Status among Arab Americans. American Journal of Public Health 100: 284–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pargament, Kenneth I. 1997. The Psychology of Religion and Coping. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Crystal L. 2005. Religion as a Meaning-making Framework in Coping With Life Stress. In Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. Edited by Ray F. Paloutzian and Crystal L. Park. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Crystal L. 2017. Religious Cognitions and Well-being: A Meaning Perspective. In The Happy Mind: Cognitive Contributions to Well-Being. Edited by M. D. Robinson and M. Eid. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlin, Leonard I., Elizabeth G. Menaghan, Morton A. Lieberman, and Joseph. T. Mullan. 1981. The Stress Process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 22: 337–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peek, Lori. 2011. Behind the Backlash: Muslim Americans After 9/11. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, Christopher, Willibald Ruch, Ursula Beermann, Nansook Park, and Martin E. P. Seligman. 2007. Strengths of Character, Orientations to Happiness, and Life Satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology 2: 149–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. 2007. Muslim Americans: Middle Class and Mostly Mainstream. May 22. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2007/05/22/muslim-americans-middle-class-and-mostly-mainstream2/ (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Pew Research Center. 2011. A Portrait of Muslim Americans: Muslims Widely Seen as Facing Discrimination. August 30. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2011/08/30/a-portrait-of-muslim-americans/ (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Pew Research Center. 2017. U.S. Muslims Concerned About Their Place in Society, but Continue to Believe in the American Dream (U.S.-Muslims-Full-Report-with-Population-Update-v2). Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Pew Research Center. 2025. 2023–24 U.S. Religious Landscape Study (RLS). Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2025/02/26/religious-landscape-study-executive-summary/ (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Pollner, Melvin. 1989. Divine Relations, Social Relations, and Well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 30: 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quran. 2025. Available online: https://quran.com/al-baqarah/216 (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Richter, Anne, and Katharina Näswall. 2019. Job Insecurity and Trust: Uncovering a Mechanism Linking Job Insecurity to Well-being. Work & Stress 33: 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, Mohd Ahsan Kabir, and Mohammad Zakir Hossain. 2017. Relationship between Religious Belief and Happiness: A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Religion and Health 56: 1561–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahraian, Ali, Abdullah Gholami, Ali Javadpour, and Benafsheh Omidvar. 2013. Association between Religiosity and Happiness among a Group of Muslim Undergraduate Students. Journal of Religion and Health 52: 450–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheible, Jana A., and Fenella Fleischmann. 2013. Gendering Islamic Religiosity in the Second Generation: Gender Differences in Religious Practices and the Association with Gender Ideology among Moroccan- and Turkish-Belgian Muslims. Gender & Society 27: 372–95. [Google Scholar]

- Schieman, Scott. 2011. Religious Beliefs and Mental Health: Applications and Extensions of the Stress Process Model. In The SAGE Handbook of Mental Health and Illness. Edited by David Pilgrim, Anne Rogers and Bernice Pescosolido. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Schieman, Scott, Kim Nguyen, and Diana Elliott. 2003. Religiosity, Socioeconomic Status, and the Sense of Mastery. Social Psychology Quarterly 66: 202–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffrin, Holly H., and S. Katherine Nelson. 2010. Stressed and Happy? Investigating the Relationship between Happiness and Perceived Stress. Journal of Happiness Studies 11: 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, Landon. 2016. The Gender Pray Gap: Wage Labor and the Religiosity of High-earning Women and Men. Gender & Society 30: 643–69. [Google Scholar]

- Schnabel, Landon. 2017. Gendered Religiosity. Review of Religious Research 59: 547–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, Martin E. P. 2002. Authentic Happiness: Using the New Positive Psychology to Realize Your Potential for Lasting Fulfillment. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shahama, Aishath, Aashiya Patel, Jerome Carson, and Ahmed M. Abdel-Khalek. 2022. The Pursuit of Happiness Within Islam: A Systematic Review of Two Decades of Research on Religiosity and Happiness in Islamic Groups. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 25: 629–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, Manfusa. 1993. Religiosity as a Predictor of Well-being and Moderator of the Psychological Impact of Unemployment. The British Journal of Medical Psychology 66: 341–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, Sunitha, Sowmya Kshtriya, and Reimara Valk. 2023. Health, Hope, and Harmony: A Systematic Review of the Determinants of Happiness Across Cultures and Countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20: 3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snoep, Liesbeth. 2008. Religiousness and Happiness in Three Nations: A Research Note. Journal of Happiness Studies 9: 207–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, Andrew. 2019. Happiness and Health. Annual Review of Public Health 40: 339–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglbauer, Barbara, and Bernad Batinic. 2015. Proactive Coping With Job Insecurity: Is It Always Beneficial to Well-being? Work & Stress 29: 264–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhail, Kausar, and Haroon R. Chaudhry. 2004. Predictors of Subjective Well-being in an Eastern Muslim Culture. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 23: 359–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinyard, William R., Ah-Keng Kau, and Hui-Yin Phua. 2001. Happiness, Materialism, and Religious Experience in the US and Singapore. Journal of Happiness Studies 2: 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Robert J., Linda M. Chatters, and Jeffrey Levin. 2004. Religion in the Lives of African Americans: Social, Psychological, and Health Perspectives. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Tokur, Behlül. 2017. Stres ve Din. Istanbul: Çamlıca Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Tokur, Behlül. 2018. İmtihan Psikolojisi. Ankara: Fecr Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, Khalil, Syed Muddasar Ali Shah, and Irshad Ahmad. 2024. Investigating the Moderating Role of Itikaf on the Relationship between Psychological Distress and Subjective Happiness. International Journal of Social Science Archives 7: 1145–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upenieks, Laura. 2025. Are Religious People Any Happier? Probing the Divine Relationship, Organizational Religiosity, and the Role of Education and Income in the United States. Journal of Religion and Health, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upenieks, Laura, and Christopher G. Ellison. 2022. Changes in Religiosity and Reliance on God during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Protective Role under Conditions of Financial Strain? Review of Religious Research 64: 853–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustaoğlu, Murat. 2024. Muslim Minorities in the United States. In The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Islamic Finance and Economics. Edited by Murat Ustaoglu and Cenap Çakmak. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Meer, Peter Douve, Thomas van Huizen, and Janneke Plantenga. 2025. ‘No Manner of Hurt Was Found Upon Him’: The Role of Religiousness in the Mental Health Effect of Job Insecurity. Social Science & Medicine 364: 117502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanderWeele, Tyler J. 2017a. On the Promotion of Human Flourishing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 114: 8148–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanderWeele, Tyler J. 2017b. Religious Communities and Human Flourishing. Current Directions in Psychological Science 26: 476–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenhoven, Ruut. 1991. Is Happiness Relative? Social Indicators Research 24: 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Monica L., Marie-Rachelle Narcisse, Katherine Togher, and Pearl A. McElfish. 2024. Job Flexibility, Job Security, and Mental Health among US Working Adults. JAMA Network Open 7: e243439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, Mark. 2000. Fear of Crime in the United States: Avenues for Research and Policy. Criminal Justice 4: 451–89. [Google Scholar]

- Wikström, Owe. 1987. Attribution, Roles and Religion: A Theoretical Analysis of Sundén’s Role Theory of Religion and the Attributional Approach to Religious Experience. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 26: 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Xin, Chen Zhang, Jiayan Gou, and Shih-Yu Lee. 2024. The Influence of Psychosocial Work Environment, Personal Perceived Health, and Job Crafting on Nurses’ Well-being: A Cross-sectional Survey Study. BMC Nursing 23: 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Percentage | Mean | Range | SD | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Happiness | 82.94 | - | 0−1 | - | 1008 |

| Job insecurity | - | 1.19 | 0−3 | 1.15 | 1050 |

| Surveillance worry | - | 1.05 | 0−3 | 1.16 | 1050 |

| Hijab worry | 1.55 | 0−3 | 1.07 | 1050 | |

| Experiences of actual discrimination (Index) | - | 1.28 | 0−7 | 1.53 | 992 |

| Importance of religion | - | 2.56 | 0−3 | 0.75 | 1050 |

| Mosque attendance | - | 2.60 | 0−5 | 1.72 | 1050 |

| Daily Salah | - | 2.74 | 0−4 | 1.35 | 1050 |

| Age | - | 42.36 | 18−88 | 15.85 | 1050 |

| Female | 47.14 | - | 0−1 | - | 495 |

| Male | 52.86 | - | 0−1 | - | 555 |

| Asian | 29.52 | - | 0−1 | - | 310 |

| Black | 20.19 | - | 0−1 | - | 212 |

| White | 32.86 | - | 0−1 | - | 345 |

| Other Races | 17.43 | - | 0−1 | - | 183 |

| Married | 67.44 | - | 0−1 | - | 694 |

| Education | - | 5.14 | 1−9 | 1.78 | 1050 |

| Excellent financial situation | 11.55 | - | 0−1 | - | 117 |

| Part-time employment | 17.39 | - | 0−1 | - | 177 |

| Born in the US | 26.56 | - | 0−1 | - | 272 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Focal Variables | ||||||||||

| Job insecurity | 0.71 | ** | 0.71 | ** | 0.71 | * | 0.70 | * | 0.71 | * |

| Surveillance worry | 1.22 | 1.23 | 1.21 | 1.21 | 1.22 | |||||

| Hijab worry | 1.22 | 1.20 | 1.33 | 1.32 | 1.31 | |||||

| Experiences of actual discrimination (Index) | 0.86 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 | |||||

| Sociodemographics | ||||||||||

| Age | 0.98 | 0.98 | * | 0.98 | 0.98 | |||||

| Black | 0.65 | 0.48 | 0.47 | 0.49 | ||||||

| Asian | 0.95 | 1.03 | 0.89 | 0.93 | ||||||

| Other Races | 0.48 | * | 0.40 | * | 0.36 | * | 0.38 | * | ||

| Married | 1.22 | 1.32 | 1.34 | 1.30 | ||||||

| Education (Continuous) | 1.19 | * | 1.18 | * | 1.18 | * | ||||

| Excellent finance | 2.50 | 2.71 | 2.81 | * | ||||||

| Part-time employment | 0.42 | ** | 0.38 | ** | 0.38 | ** | ||||

| Born in the U.S. | 2.56 | * | 2.69 | * | 2.61 | * | ||||

| Religious Covariates | ||||||||||

| Importance of religion | 1.05 | 1.03 | ||||||||

| Mosque attendance | 1.27 | * | 1.26 | * | ||||||

| Pray five times a day | 0.79 | 0.79 | ||||||||

| Interaction Effect | ||||||||||

| Importance of religion X Job insecurity | 1.13 | |||||||||

| Model df | 502 | 439 | 423 | 423 | 423 | |||||

| F Test | 3.41 | ** | 2.10 | * | 3.22 | *** | 3.01 | *** | 2.81 | *** |

| N | 502 | 495 | 478 | 478 | 478 | |||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Focal Variables | ||||||||||

| Job insecurity | 0.60 | *** | 0.58 | *** | 0.58 | ** | 0.52 | *** | 0.50 | *** |

| Surveillance worry | 1.00 | 1.04 | 1.03 | 1.31 | 1.16 | |||||

| Hijab worry | 1.41 | * | 1.40 | * | 1.42 | * | 1.50 | * | 1.52 | * |

| Experiences of actual discrimination (Index) | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.77 | * | 0.72 | * | 0.70 | ** | ||

| Sociodemographics | ||||||||||

| Age | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | ||||||

| Black | 2.04 | 1.73 | 1.46 | 1.45 | ||||||

| Asian | 1.97 | 2.70 | * | 2.15 | 2.13 | |||||

| Other Races | 1.70 | 1.74 | 1.74 | 1.75 | ||||||

| Married | 2.09 | * | 2.50 | ** | 2.03 | * | 1.91 | * | ||

| Education (Continuous) | 1.26 | ** | 1.35 | ** | 1.36 | ** | ||||

| Excellent finance | 3.20 | 3.60 | * | 3.65 | * | |||||

| Part-time employment | 0.68 | 0.61 | 0.61 | |||||||

| Born in the U.S. | 3.78 | ** | 3.70 | ** | 3.74 | ** | ||||

| Religious Covariates | ||||||||||

| Importance of religion | 1.77 | * | 1.98 | ** | ||||||

| Mosque attendance | 0.88 | 0.88 | ||||||||

| Pray five times a day | 1.19 | 1.18 | ||||||||

| Interaction Effect | ||||||||||

| Importance of religion X Job insecurity | - | 1.49 | * | |||||||

| Model df | 426 | 416 | 405 | 405 | 405 | |||||

| F Test | 4.59 | * | 3.44 | ** | 3.83 | *** | 3.54 | *** | 3.39 | *** |

| N | 452 | 442 | 429 | 429 | 429 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Güven, M.; Acevedo, G.A. Job Insecurity and Happiness Among Muslim Americans: Does the Moderating Role of Religious Involvement Differ by Gender? Religions 2025, 16, 1246. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16101246

Güven M, Acevedo GA. Job Insecurity and Happiness Among Muslim Americans: Does the Moderating Role of Religious Involvement Differ by Gender? Religions. 2025; 16(10):1246. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16101246

Chicago/Turabian StyleGüven, Metin, and Gabriel A. Acevedo. 2025. "Job Insecurity and Happiness Among Muslim Americans: Does the Moderating Role of Religious Involvement Differ by Gender?" Religions 16, no. 10: 1246. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16101246

APA StyleGüven, M., & Acevedo, G. A. (2025). Job Insecurity and Happiness Among Muslim Americans: Does the Moderating Role of Religious Involvement Differ by Gender? Religions, 16(10), 1246. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16101246