Unraveling the Local Hymnal: Artistic Creativity and Agency in Four Indonesian Christian Communities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Experiencing Hymnals

3.1. Differing Origins

3.2. Digital Forms

3.3. Musical-Language

4. Hymnals in Society

Repeated exposure to numerous objects emanating from a different cultural tradition—if those objects are of interest to people for their own local reasons—will result in the transmission of something. Moreover, over time, it will result … in the desire not only for the objects themselves, but for the ability to produce those objects.(65)

Confronted with a cultural element, modern recipients of culture do not (or, do not in this ideal world of narratives) simply replicate the element. Instead, they place it in relation to other elements, take strands from one and intertwine them with strands from others, thereby weaving something that, while a continuation of what has come before, is also arguably something new and different.(176)

4.1. Active Theologizing

Putting songs in a book is part of our responsibility as the church. People sing about their relationship with God and all kinds of theological topics in church. The songs we sing need to be carefully selected for their theology and philosophy so that people are in a right relationship with God, self, others, and creation. These songs in the book are acceptable and excellent choices for people to use.10,11

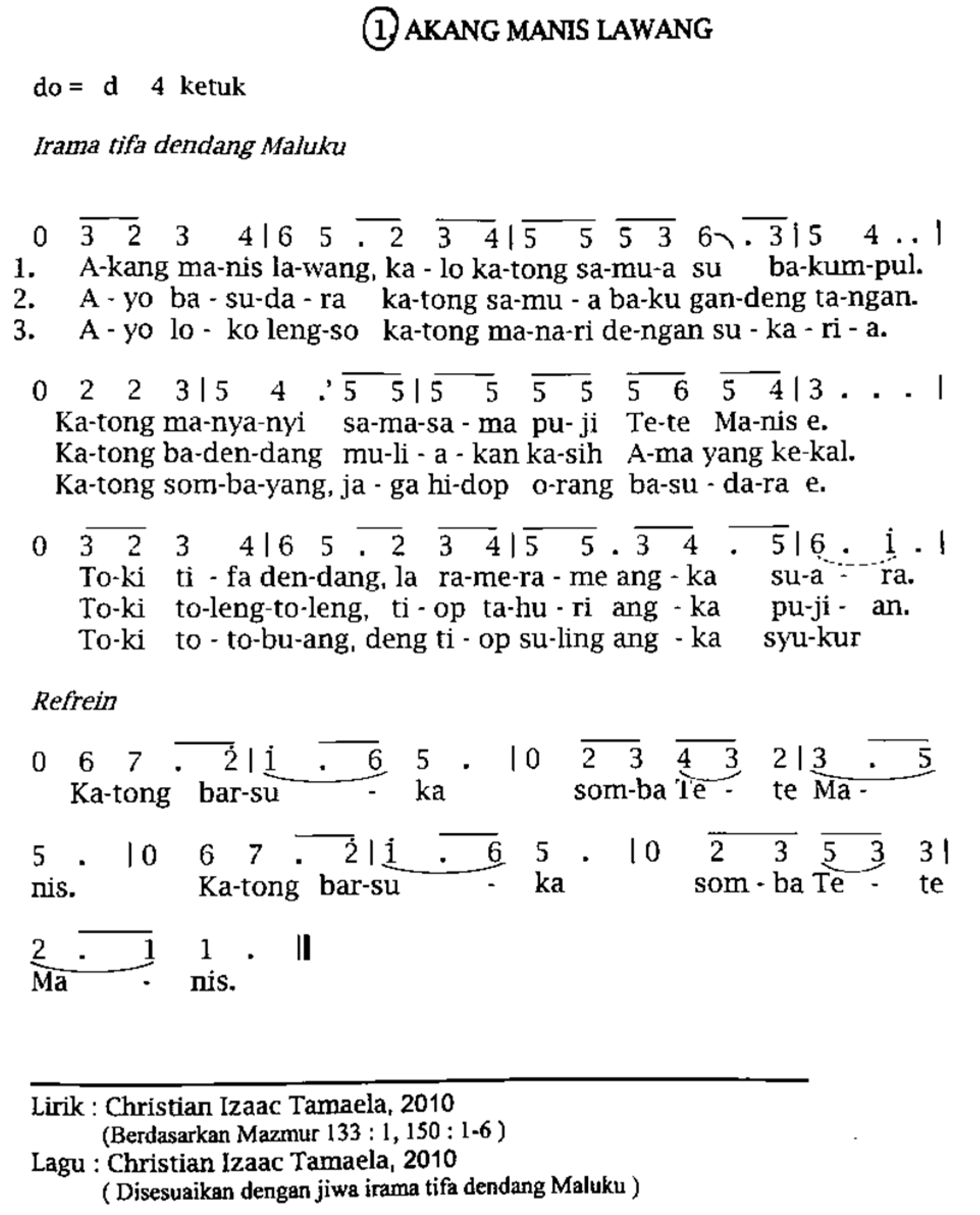

4.2. Musical Localization

In the beginning, I heard how a few people created our hymnal as songs were gathered to become one book. I heard [the missionaries] first tried using Western songs, but it was challenging. From the beginning, they had the idea to use our language, but then everyone decided to use our singing rhythm for worship, too. Using outside songs was just impossible. So they decided, “Why don’t we make new songs, make them spiritual, and use our singing style?” The singing style is Hatam, and so is the language. Now, people can understand God’s word through songs.17

Musical localization … is capable of encompassing the ecumenical aspirations of the concepts of inculturation and contextualization and the emphasis on local agency signified by indigenization without succumbing to their pitfalls, especially those of ethnocentrism and essentialized notions of authenticity. … The process of localization as we define it here is inherently relational; through it, a community positions itself in historical and cultural relationship with—not just in distinction from—often multiple others.

We have received Western culture and now feel it is our own. Through contextualization, it’s like [our culture] is renewed as two things have fused. We can’t fault songwriters for using the seventh in their songs because now we like how it sounds. We tend to be so allergic to other sounds, but we can’t fault the seventh because it is a part of us now. … [The seventh] is in me now, but this doesn’t mean our local songs aren’t good. It just means we need to accommodate other musical traditions, too. It enhances our worship. We can perform all these kinds of songs, and our worship is enriched. Now, people worldwide can know how we Moluccans worship. Hearing our worship is how we spread the gospel. This enriches the global church.19

5. The Once and Future Hymnal

Metaculture is significant in part, at least, because it imparts an accelerative force to culture. It aids culture in its motion through space and time. It gives a boost to the culture that it is about, helping to propel it on its journey. The interpretation of culture that is intrinsic to metaculture, immaterial as it is, focuses attention on the cultural thing, helps to make it an object of interest, and, hence, facilitates its circulation.

5.1. Stable–Malleable

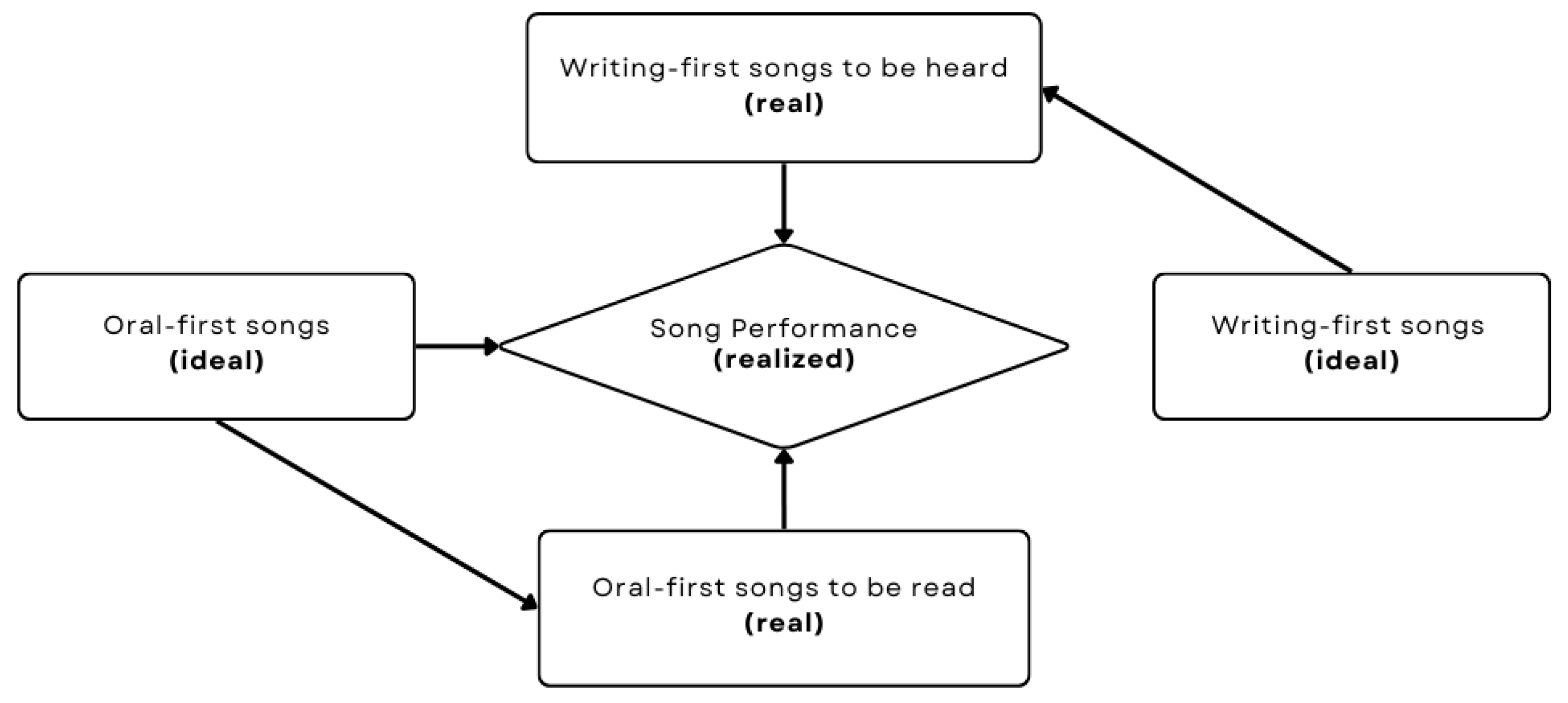

5.1.1. Stable–Malleable in Performance

What makes [notated music] ideal in another sense is that—in virtue of having an existence disconnected from the world of real objects—[the songs] would seem to be protected from the caprices of the real world and thus the dangers that threaten the existence of real objects.(7)

5.1.2. Stable–Malleable in Culture

The transition from an oral culture to a literate culture is a transition from incorporating practices to inscribing practices. The impact of writing depends upon the fact that any account which is transmitted by means of inscriptions is unalterably fixed, the process of its composition being definitively closed. The standard edition and the canonic work are the emblems of this condition. This fixity is the spring that releases innovation.(75)

The metaculture of tradition has been, first and foremost, concerned with the culture passing through words rather than with the culture passing through nonlinguistic things, such as pots and machetes. And it is the culture contained in spoken words that is the most mercurial, most in need of a metaculture of tradition for its stabilization or containment. … Writing, in some measure, fixes the disseminated object.

5.2. Onceness

5.3. Optimal Distinctiveness and Futurity

The creation of musical hybrids results from the desire to move beyond the conventions of established forms, to add an “ethnic accent” (logat etnis) that emerges not from the inability to speak without one … but from a conscious effort to introduce “local” elements into a global form—to add something new and thus to participate in the replication of culture characteristic of the metaculture of modernity.(259)

6. Conclusions

To say that societies are self-interpreting communities is to indicate the nature of that deposit … among the most powerful of these self-interpretations are the images of themselves as continuously existing that societies create and preserve.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | For more about community-centric, autogenic research and its role in musical revitalization movements, see (Saurman 2013). |

| 2 | It is important to acknowledge my connections to the Hatam community. My wife’s grandparents began working among the Hatam in the late 1950s in response to a request from the community for missionaries and continued serving there until the late 1990s. I have more recently engaged with the Hatam after a request for a songwriting workshop in 2024. |

| 3 | The journey of each song toward incorporation in a hymnal is another fascinating topic but beyond the scope of this study. For example, some songs, such as those from Hatam, were passed down orally before being written down for inclusion in a songbook. The Minahasa hymnal has its origins in a songwriting workshop facilitated by the church for the specific purpose of creating a hymnal. |

| 4 | When describing orality, I follow the definition created by Charles Madinger from the Institute for Orality Strategies (https://i-os.org, accessed on 30 August 2024). In the forthcoming second edition of Creating Local Arts Together by Schrag, Madinger defines orality as “A preference for and reliance on oral communication; a learned framework for expressing mind and heart through all five senses” (Schrag, forthcoming). |

| 5 | I use the terms field, domain, and individual as described by Csikszentmihalyi (2014) in his systems model of creativity. In the systems model, the contribution of the individual is to produce a variation in the existing domain. The field is the people in the system who play the role of selecting which new things will succeed and be incorporated into the domain. The domain is the information: the structured body of knowledge, attitudes, and skills for performing, creating, or innovating, which is stored and transmitted by existing practitioners and experts. “Creativity occurs when a person makes a change in the information contained in a domain, a change that will be selected by the field for inclusion in the domain” (442). |

| 6 | It should be noted that although the Figure 2 situates oral-ideal songs as more malleable than written-ideal songs, this is a generalization and not always the case. Krabill (1995) notes the presence of fixed-oral songs in Harrist hymnody, resulting in a very stable ideal, oral form transmitted across many generations (10). In the same way, written-ideal songs can also be malleable when performers ignore written harmonies or other aspects of the notation. |

| 7 | Simson Dowansiba, in discussion with the author, May 2024. |

| 8 | An excellent example of this is a playlist on YouTube of many songs from the Maluku hymnal: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL1mNX6YgkMdFa0QUJJvlZg9ajkKKUBFrq (accessed on 30 August 2024). |

| 9 | A fuller exploration into the digital presences of these hymnals is needed, exploring topics such as purpose, perception, and creation. However, this goes beyond the scope of the current study. |

| 10 | All interviews were conducted in Indonesian or Manado Malay. Translations to English are my own. |

| 11 | John Beay, in discussion with the author, May 2024. |

| 12 | UKIT theology professors, in discussion with the author, March 2023. |

| 13 | Ramli Sarimbangun, in discussion with the author, March 2023. |

| 14 | See note 7. |

| 15 | Elyaser Palondongan, in conversation with the author, May 2024. |

| 16 | See note 7. |

| 17 | Daniel Dowansiba, in conversation with the author, May 2024. |

| 18 | See note 11. |

| 19 | See note 11. |

| 20 | A search online reveals numerous news articles about the successes of Indonesian choirs in international competitions. For example, six Indonesian choirs won awards in 2023 at the Tokyo International Choir Competition. An Indonesian choir won the Tolosa Choral Contest in 2017, qualifying for the finals in the European Grand Prix for Choral Singing. A children’s choir won the grand prize at a festival in Florence, Italy in 2023. An Indonesian university choir placed second in the Taipei International Choir Competition in 2023. Choirs from the archipelago frequently compete in the World Choir Games. Indonesia also hosts many competitions, such as the Bali International Choir festival and the Bandung International Choir Festival. |

| 21 | A hymnal is one kind of artistic communication genre, and the songs within are another. |

| 22 | See note 5 and The Systems Model of Creativity (Csikszentmihalyi 2014) for a fuller explanation of the individual, field, and domain in the creative process. |

References

- Badan Pekerja Majelis Sinode GMIM. 2009. Nyanyikanlah Nyanyian Baru Bagi Tuhan, 1st ed. Tomohon: Badan Pekerja Majelis Sinode GMIM. [Google Scholar]

- Badan Pekerja Majelis Sinode GMIM. 2010. Nyanyikanlah Nyanyian Baru Bagi Tuhan, 2nd ed. Tomohon: Badan Pekerja Majelis Sinode GMIM. [Google Scholar]

- Badan Pekerja Majelis Sinode GMIM. 2011. Nyanyikanlah Nyanyian Baru Bagi Tuhan (Edisi Empat Suara), 3rd ed. (empat suara). Tomohon: Badan Pekerja Majelis Sinode GMIM. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, Bruce Ellis. 2003. The Improvisation of Musical Dialogue: A Phenomenology of Music. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Harris M. 2012. Phenomenological Approaches in the History of Ethnomusicology. In Oxford Handbooks Online: Music: Scholarly Research Reviews. Edited by Oxford Handbooks Editorial Board. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, Harris M., and Ruth M. Stone. 2019. Introduction. In Theory for Ethnomusicology, 2nd ed. Edited by Harris M. Berger and Ruth M. Stone. New York: Routledge, pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bhabha, Homi K. 1996. Culture’s In-Between. In Questions of Cultural Identity. Edited by Stuart Hall and Paul du Gay. London: SAGE Publications Ltd., pp. 52–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bowie, Andrew. 2003. Music, Language and Literature. In Aesthetics and Subjectivity. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 221–57. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt155jcnj.11 (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Brewer, Marilynn B., Jorge M. Manzi, and John S. Shaw. 1993. In-Group Identification as a Function of Depersonalization, Distinctiveness, and Status. Psychological Science 4: 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brittingham, John Thomas. 2016. Four on the Floor: Phenomenological Reflections on Liturgy and Music. In In Spirit and in Truth: Philosophical Reflections on Liturgy and Worship. Edited by Wm. Curtis Holtzen and Matthew Nelson Hill. Claremont Studies in Methodism & Wesleyanism. Claremont: Claremont Press, pp. 147–64. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvbcd2kx.14 (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- Brown, Frank Burch. 2003. Good Taste, Bad Taste, and Christian Taste: Aesthetics in Religious Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cheong, John. 2018. Polycentrism in Majority World Theologizing: An Engagement with Power and Essentialism. In Majority World Theologies: Theologizing from Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Ends of the Earth. Evangelical Missiological Society Series 26; Littleton: William Carey Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Connerton, Paul. 1989. How Societies Remember. Themes in the Social Sciences. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Connor, Matt. 2022. Creativity, Liminality, and Metaphor in Songwriting. Global Forum on Arts and Christian Faith 10: A61–A76. [Google Scholar]

- Connor, Matt, and Matt Menger. 2021. Strengthening Christian Identity through Scripture Songwriting in Indonesia. Religions 12: 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. 2014. The Systems Model of Creativity. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, Per. 2017a. Music Performance as Creative Practice. In Music and Knowledge: A Performer’s Perspective. Leiden: Brill, pp. 13–24. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctv2gjx0b4.6 (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Dahl, Per. 2017b. Phenomenology. In Music and Knowledge: A Performer’s Perspective. Leiden: Brill, pp. 107–14. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctv2gjx0b4.15 (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Derrida, Jacques. 1982. Margins of Philosophy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dowansiba, S., R. I. Griffiths, and H. Iwou. 2017. Doia Mem Musyamei Nya. Manokwari: Gereja Persekutuan Kristen Alkitab di Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt, A Royce. 2010. What Is a Hymnal?: Much More than a Songbook. The Covenant Quarterly 68: 42–51. [Google Scholar]

- Faudree, Paja. 2012. Music, Language, and Texts: Sound and Semiotic Ethnography. Annual Review of Anthropology 41: 519–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gereja Protestan Maluku. 2015. Nyanyian Jemaat, 3rd ed. Jakarta: Gereja Protestan Maluku. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, Cheryl. 2012. Hysteresis. In Pierre Bourdieu: Key Concepts, 2nd ed. Edited by Michael Grenfell. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, Martin. 2009. Poetry, Language, Thought. New York: Perennial Classics. [Google Scholar]

- Husserl, Edmund, and Lee Hardy. 1999. The Idea of Phenomenology: A Translation of Die Idee Der Phänomenologie, Husserliana II. Edmund Husserl Collected Works. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Ingalls, Monique Marie, Muriel Swijghuisen Reigersberg, and Zoe C. Sherinian, eds. 2018. Making Congregational Music Local in Christian Communities Worldwide. Congregational Music Studies Series; New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Shin Ji. 2016. Postcolonial Reflection on the Christian Mission: The Case of North Korean Refugees in China and South Korea. Social Sciences 5: 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Roberta Rose. 2009. Pathways in Christian Music Communication: The Case of the Senufo of Côte d’Ivoire. Eugene: Pickwick Publications. [Google Scholar]

- King, Roberta Rose. 2019. Global Arts and Christian Witness: Exegeting Culture, Translating the Message, and Communicating Christ. Mission in Global Community. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. [Google Scholar]

- King, Roberta Rose, Jean Ngoya Kidula, James R. Krabill, and Thomas Oduro. 2008. Music in the Life of the African Church. Waco: Baylor University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Krabill, James R. 1995. The Hymnody of the Harrist Church among the Dida of South-Central Ivory Coast (1913–1949): A Historico-Religious Study. Studien Zur Interkulturellen Geschichte Des Christentums, Etudes d’histoire Interculturelle Du Christianisme. Studies in the Intercultural History of Christianity, Bd. 74. Frankfurt am Main: P. Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Leonardelli, Geoffrey J., Cynthia L. Pickett, and Marilynn B. Brewer. 2010. Optimal Distinctiveness Theory. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Amsterdam: Elsevier, vol. 43, pp. 63–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menger, Matt. 2020. Kolintang Studies during a Pandemic. Global Forum on Arts and Christian Faith 8: WP9–WP20. [Google Scholar]

- Menger, Matt. 2024. The Original Hymnody of Gereja Masehi Injili Di Minahasa. Ethnodoxology 12: A26–A53. [Google Scholar]

- Moran, Dermot. 2000. Jacques Derrida: From Phenomenology to Deconstruction. In Introduction to Phenomenology. New York: Routledge, pp. 435–74. [Google Scholar]

- Nattiez, Jean-Jacques. 1990. Music and Discourse: Toward a Semiology of Music. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Poplawska, Marzanna. 2011. Christianity and Inculturated Music in Indonesia. Southeast Review of Asian Studies 33: 186–98. [Google Scholar]

- Poplawska, Marzanna. 2018. Inculturation, Institutions, and the Creation of a Localized Congregational Repertoire in Indonesia. In Making Congregational Music Local in Christian Communities Worldwide. Congregational Music Studies Series; New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Poplawska, Marzanna. 2020. Performing Faith: Christian Music, Identity and Inculturation in Indonesia. SOAS Studies in Music. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Randolph, Jacob. 2021. ‘Tough and Tender’: Theology and Masculinity in the 1991 Baptist Hymnal. Baptist History and Heritage 56: 39–59. [Google Scholar]

- Rynkiewich, Michael. 2012. Colonialism, Neocolonialism, and Postcolonialism. In Soul, Self, and Society: A Postmodern Anthropology for Mission in a Postcolonial World. Eugene: Cascade Books, pp. 169–97. [Google Scholar]

- Saurman, Todd. 2013. Singing for Survival in the Highlands of Cambodia: Revitalization of Music as Mediation and Cultural Reflexivity. Ph.D. dissertation, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand. [Google Scholar]

- Schrag, Brian. 2021. Artistic Dynamos: An Ethnography on Music in Central African Kingdoms. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Schrag, Brian. Forthcoming. Creating Local Arts Together: A Manual to Help Communities to Reach Their Kingdom Goals, 2nd ed. Pasadena: William Carey Library.

- Simmons, J. Aaron. 2010. Continuing to Look for God in France: On the Relationship between Phenomenology and Theology. In Words of Life: New Theological Turns in French Phenomenology. Edited by Norman Wirzba and Bruce Ellis Benson. Perspectives in Continental Philosophy. New York: Fordham University Press, pp. 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, James K. A. 2013. Imagining the Kingdom: How Worship Works. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Tippett, Alan Richard. 1967. Solomon Islands Christianity: A Study in Growth and Obstruction. New York: Friendship Press. Available online: http://archive.org/details/solomonislandsch0000tipp (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Turino, Thomas. 2008. Music as Social Life: The Politics of Participation. Chicago Studies in Ethnomusicology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Turino, Thomas. 2014. Peircean Thought As Core Theory For A Phenomenological Ethnomusicology. Ethnomusicology 58: 185–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, Greg. 2001. Metaculture: How Culture Moves through the World. Public Worlds, v. 8. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wallach, Jeremy. 2008. Modern Noise, Fluid Genres: Popular Music in Indonesia, 1997–2001. New Perspectives in Southeast Asian Studies. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, John D. 1988. Scripture in an Oral Culture: The Yali of Irian Jaya. Master’s thesis, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Young, Robert. 2020. Postcolonialism: A Very Short Introduction, 2nd ed. Very Short Introductions 98. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Menger, M. Unraveling the Local Hymnal: Artistic Creativity and Agency in Four Indonesian Christian Communities. Religions 2024, 15, 1130. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15091130

Menger M. Unraveling the Local Hymnal: Artistic Creativity and Agency in Four Indonesian Christian Communities. Religions. 2024; 15(9):1130. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15091130

Chicago/Turabian StyleMenger, Matt. 2024. "Unraveling the Local Hymnal: Artistic Creativity and Agency in Four Indonesian Christian Communities" Religions 15, no. 9: 1130. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15091130

APA StyleMenger, M. (2024). Unraveling the Local Hymnal: Artistic Creativity and Agency in Four Indonesian Christian Communities. Religions, 15(9), 1130. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15091130