Bidirectional Transmission Mapping of Architectural Styles of Tibetan Buddhist Temples in China from the 7th to the 18th Century

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. A Spatial–Geographical Analysis of Tibetan Buddhist Temples in China from the 7th to the 18th Century

2.1. Data Sources

2.1.1. Tibetan Buddhist Temple Data

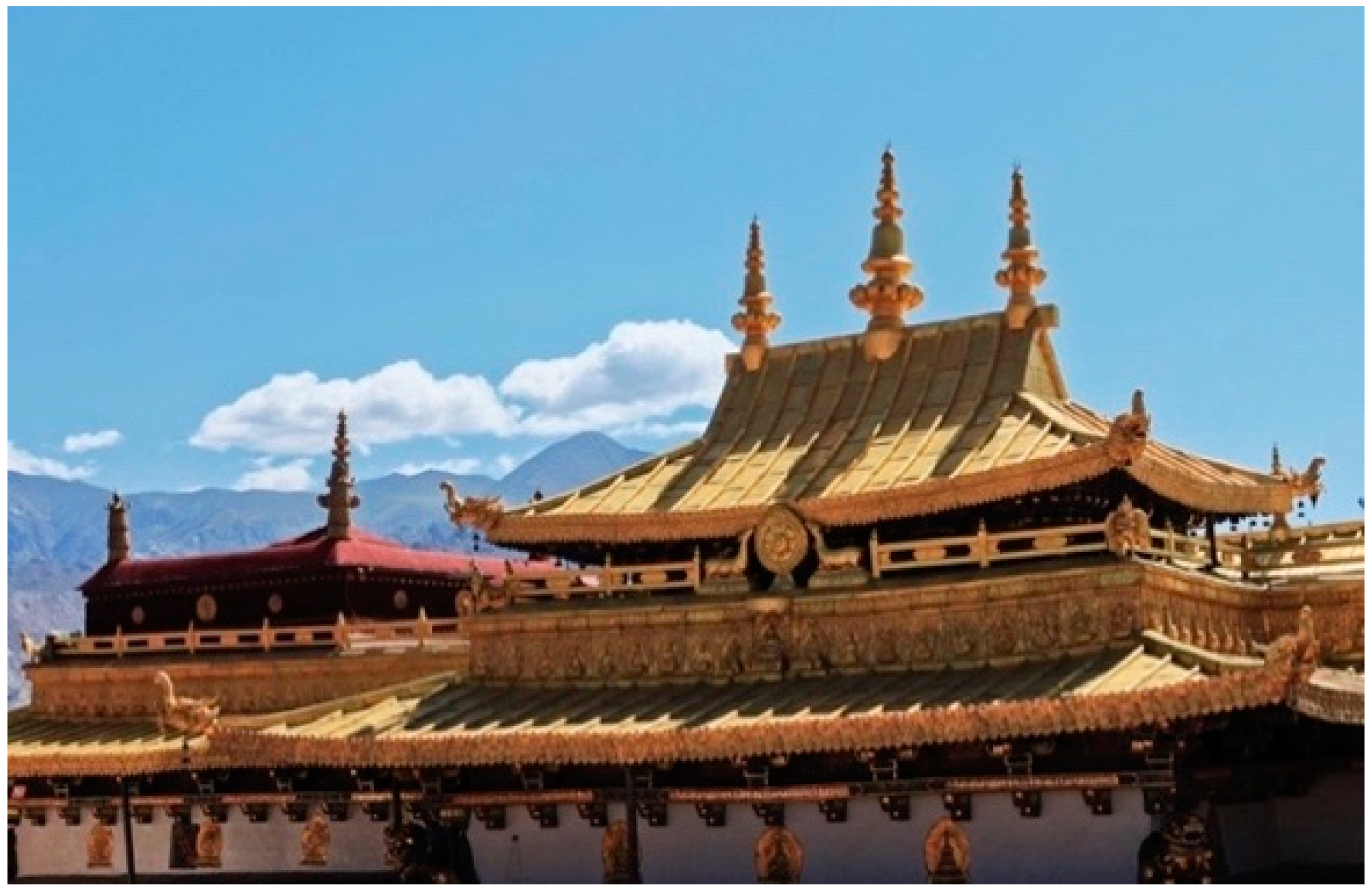

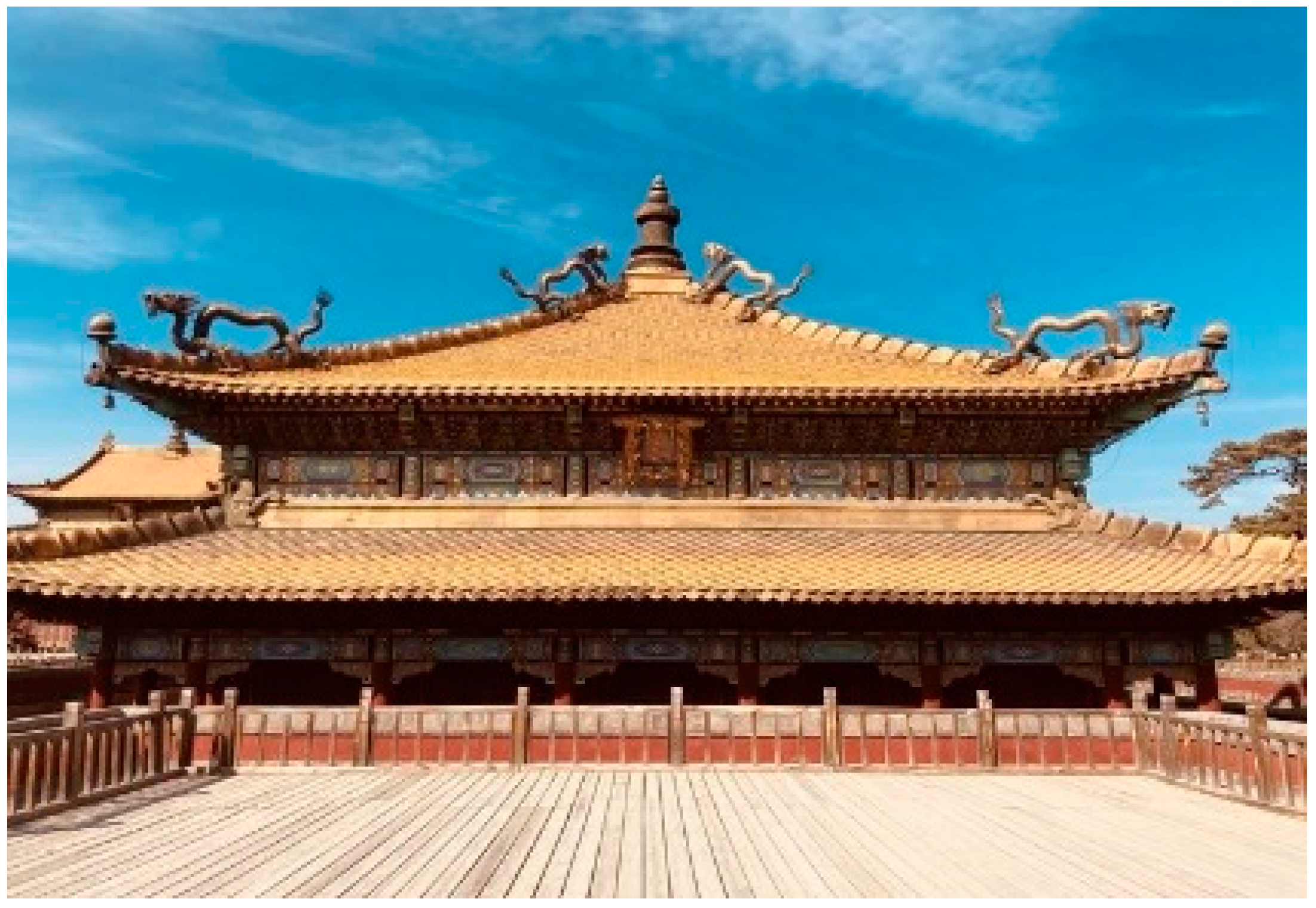

2.1.2. Maps and Geographical Data

2.2. Methods

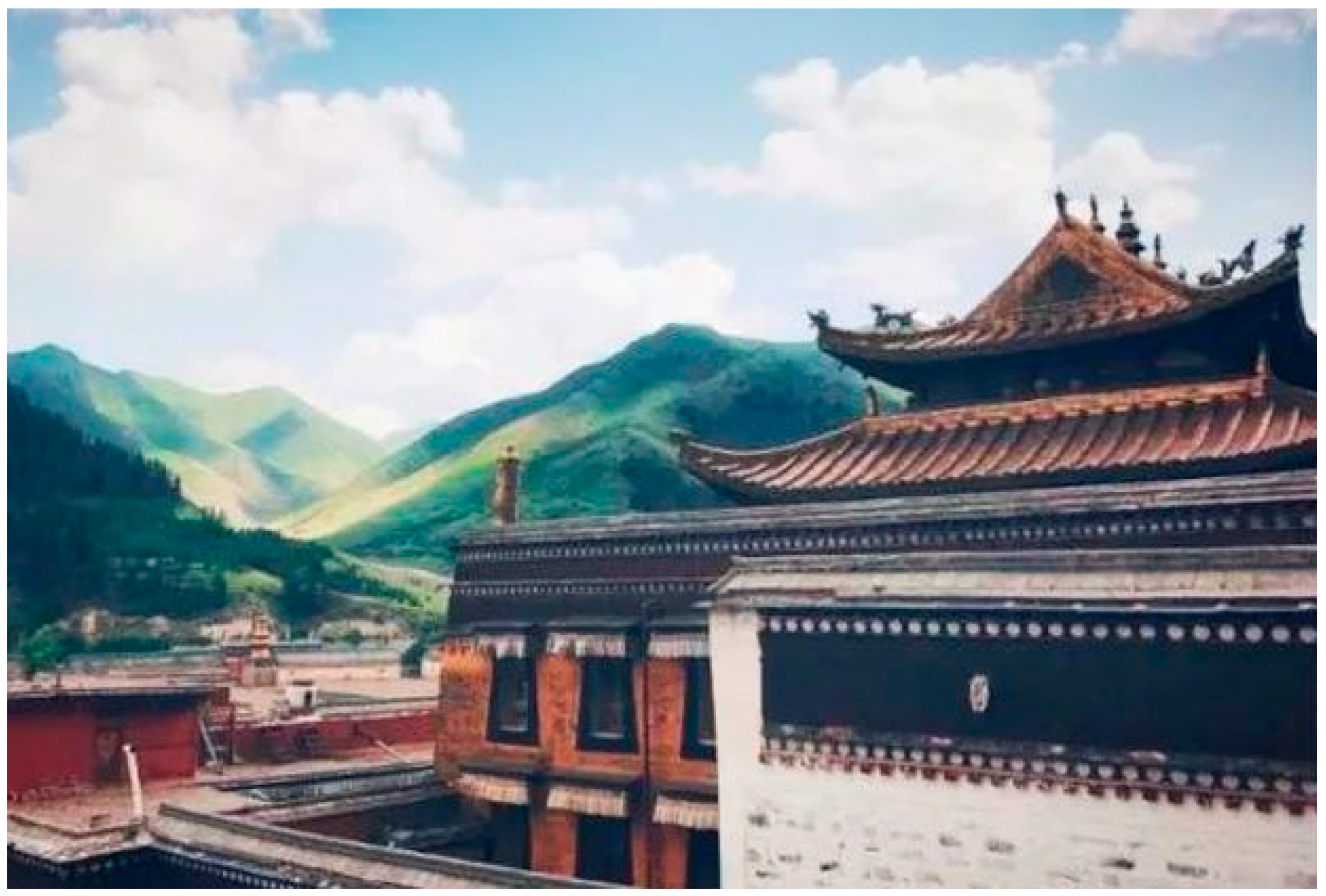

2.2.1. Establishing a Geographic Information System (GIS) Spatial Database

2.2.2. Kernel Density Estimation

2.2.3. Setting Numerical Distribution Indexes

- (1)

- Spatial Distribution Index of Tibetan Buddhist Temples (S)

- (2)

- Temporal Staging Index of Tibetan Buddhist Temples (T)

- (3)

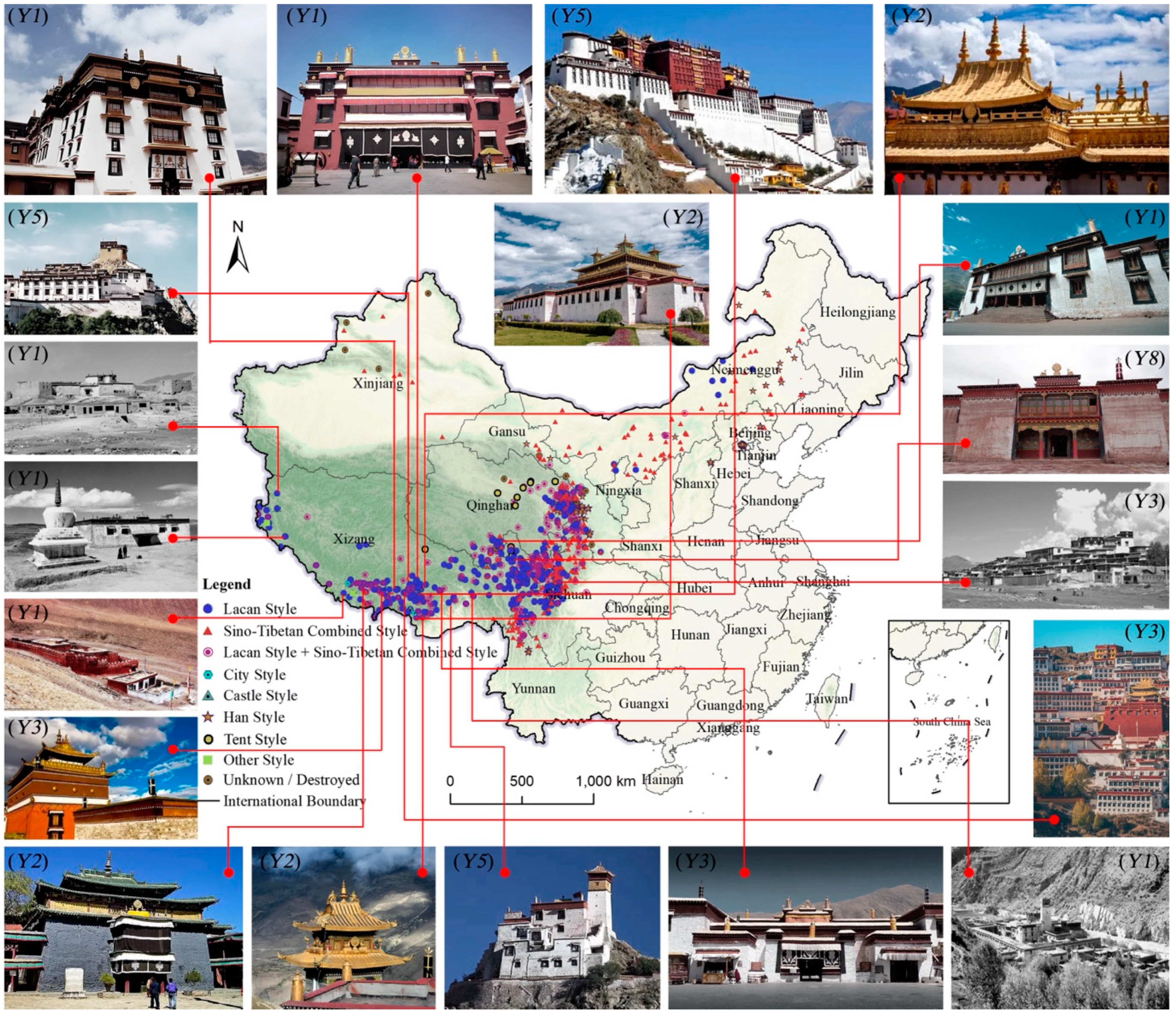

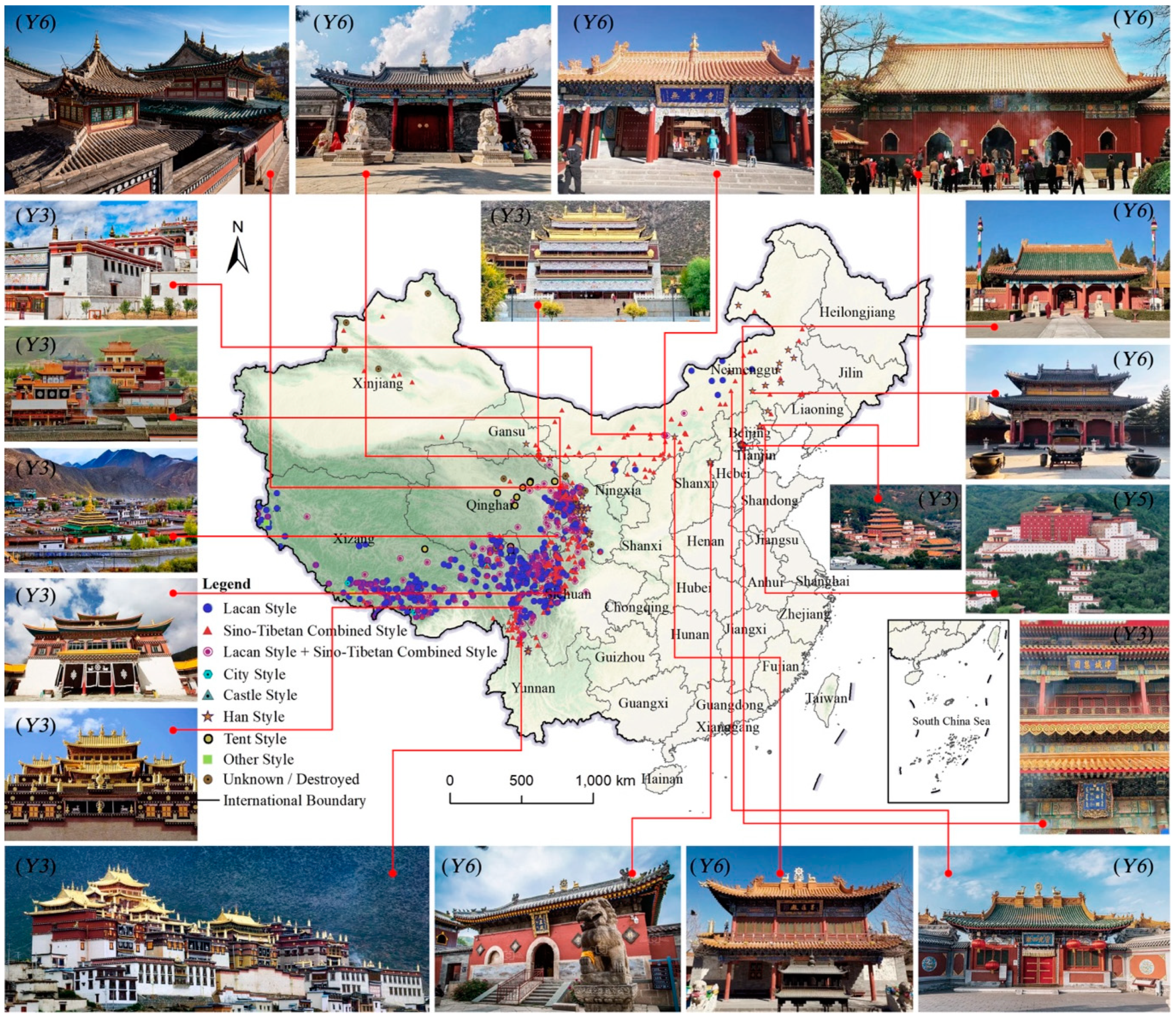

- Architectural Style Index of Tibetan Buddhist Temples (Y)

2.3. Data Distribution Analysis

2.3.1. Overall Spatial Distribution Characteristics of Tibetan Buddhist Temples

2.3.2. Overall Temporal Evolution Characteristics of Tibetan Buddhist Temples

2.3.3. Overall Evolutionary Characteristics of Architectural Styles in Tibetan Buddhist Temples

3. Westward Transmission: Analysis of the Formation Mechanism of Architectural Styles in Tibetan Buddhist Temples

3.1. Transplantation and Inheritance of Architectural Styles from the Han Region

3.2. Reconstruction and Innovation of Architectural Styles from the Han Region

4. Eastward Diffusion: Analysis of the Transmission Mechanism of Tibetan Buddhist Temple Architectural Styles

4.1. Cultural Bidirectional Exchange Driven by the Central Government

4.2. Spatial Hierarchy in the Bidirectional Transmission of Architectural Styles of Tibetan Buddhist Temples

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Historically, due to the system of political–religious unity, Tibetan Buddhist temple architecture has a broad meaning, integrating various functions and roles such as temples, palaces, and schools. |

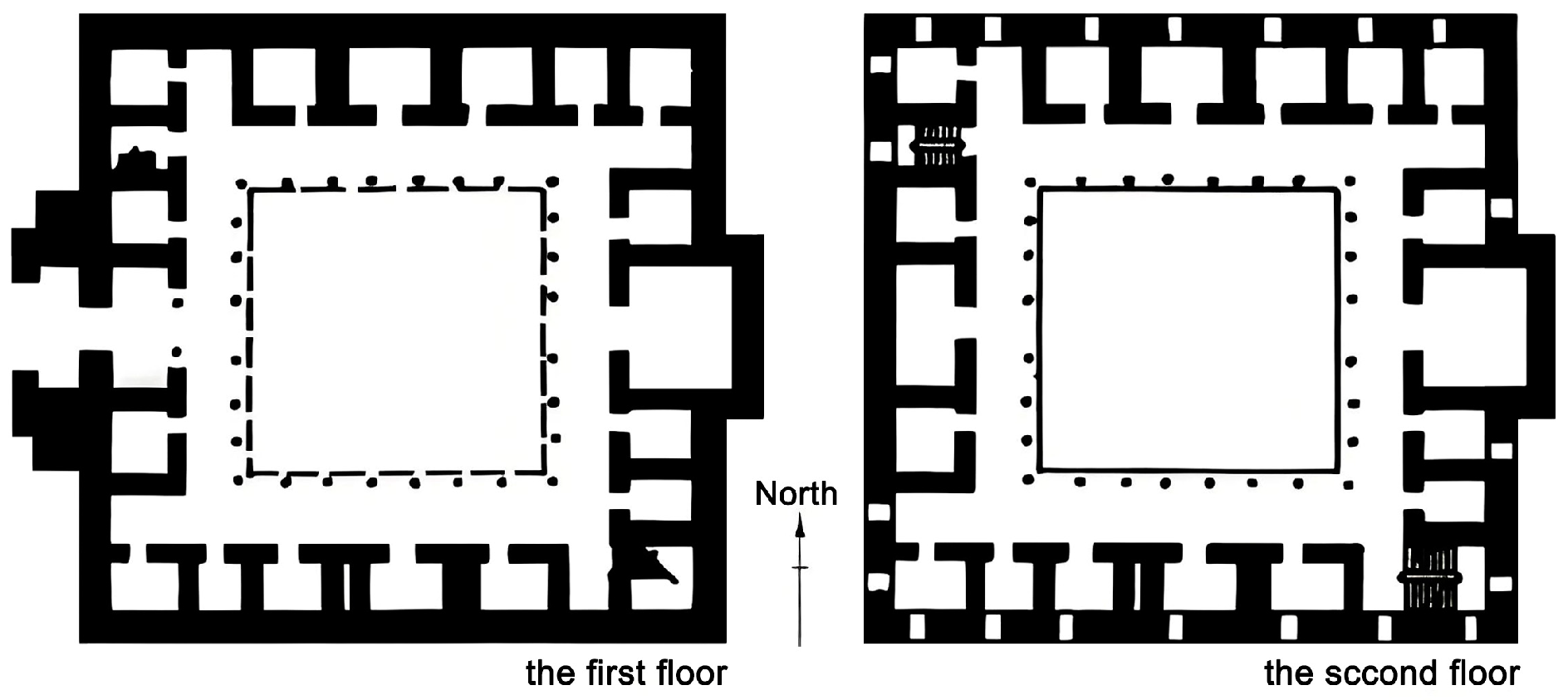

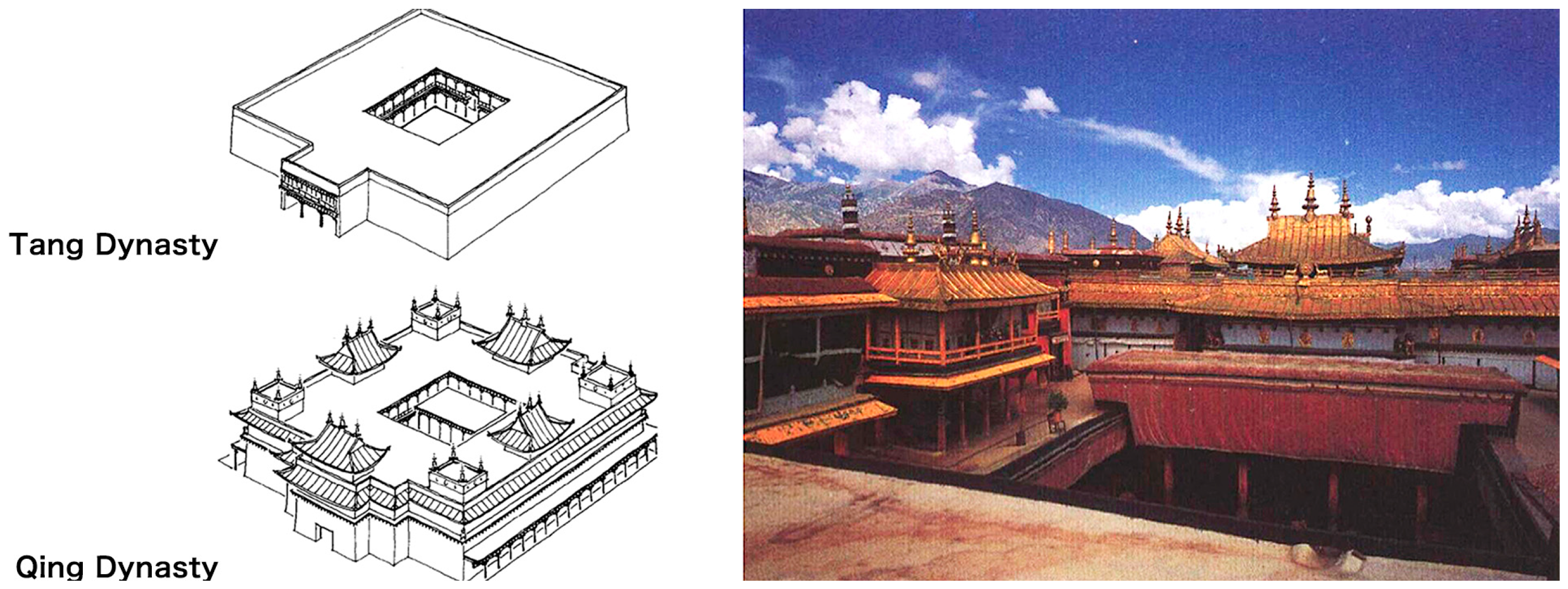

| 2 | The architectural style of the Jokhang Temple features a square courtyard surrounded by small halls, with a large Buddha hall located on the back wall. In contrast, the Samye Temple style centers around a longitudinal rectangular Buddha hall, encircled by a circumambulation corridor. A narrow, horizontal scripture hall is situated in front of the Buddha hall and the circumambulation corridor, with other buildings positioned around this core structure. |

| 3 | The data sources referenced in this article include archaeological studies on Tibetan Buddhist temple architecture, such as Temples of Western Tibet and Their Artistic Features Part I (1935), Temples of Western Tibet and Their Artistic Features Part II (1936), Gyantse and Its Temples (1941), Archaeology of Tibetan Buddhist Temples 藏传佛教寺院考古(1996), Records of Tibet 西藏记(1985), and Archaeology of Tibet 西藏考古 (1987). Additionally, the article draws from collections of Tibetan Buddhist temple architecture, including Chinese Tibetan Buddhist Temples 中国藏传佛教寺院 (1994), Tibetan Buddhist Temples 西藏佛教寺庙 (2003), Guidelines for Traditional Tibetan Architecture 西藏传统建筑导则 (2004), Tibetan Buddhist Temples in Gansu and Qinghai 甘青藏传佛教寺院 (1990), Tibetan Buddhist Temples in Tibet 西藏藏传佛教寺院 (2009), Tibetan Buddhist Temples in Qinghai 青海藏传佛教寺院 (2014), Tibetan Buddhist Temples in Gansu 甘肃藏传佛教寺院 (2013), Tibetan Buddhist Temples in Beijing 北京藏传佛教寺院 (2014), and Tibetan Buddhist Temples in Sichuan and Yunnan 四川, 云南藏传佛教寺院 (2014). We also consult local chronicles from various provinces, regions, cities, and counties, such as Tibet Chronicle 西藏志 (1936), Lhasa City Chronicle 拉萨市志 (2007), Cultural Relics Chronicle of Ali Region 阿里地区文物志 (1993), Ganzi Prefecture Chronicle 甘孜州志 (2010), Hohhot City Chronicle 呼和浩特市志 (1999), Cultural Relics Chronicle of Zhanang County 扎囊县文物志 (1986), Cultural Relics Chronicle of Qonggyai County 琼结县文物志 (1986), and Cultural Relics Chronicle of Yadong, Kangma, Gamba, and Dingjie Counties 亚东, 康马, 岗巴, 定结县文物志 (1993). |

| 4 | The Tang–Tibet ancient road began in Chang‘an (Xi‘an) and ended in Lhasa, with a total length of more than 3000 km, passing through today’s Shaanxi, Gansu, Qinghai and Tibet provinces and regions. |

| 5 | The current Ramoche Temple is a reconstruction from later generations; only the ground floor shrine remains from the early construction. |

| 6 | The golden roof, also known as the golden tile roof, is commonly found in the main halls of Tibetan Buddhist temples. It is a yellow glazed–tile gable-and-hip roof that imitates the palace architecture of the Han region, replacing the glazed tiles with gold–plated copper. The golden roof is also an essential component and architectural decoration of Tibetan temples, palaces, and pagodas. |

| 7 | Due to the intermarriage between the Xia Luwan clan and the Sakya lineage, the emperors of the Yuan Dynasty held the Xia Lu lineage in high regard, referring to them as “You are the maternal uncle of the Sakya people for generations, and thus, you are also our maternal uncle.” In the second year of the Tianli era of the Yuan Dynasty (1329 AD), the Xia Lu Temple suffered severe damage from an earthquake. Consequently, the central government of the Yuan Dynasty dispatched a large number of Han artisans and resources to repair and expand the temple. |

| 8 | The six great temples of Tibetan Buddhism include: Ganden Temple, Sera Temple, and Drepung Temple in Lhasa, Tibet; Tashilhunpo Temple in Shigatse, Tibet; Kumbum Temple in Xining, Qinghai; and Labrang Temple in Xiahe, Gansu. |

References

- Alexander, Andre. 2005. The Temples of Lhasa: Tibetan Buddhist Architecture from the 7th to the 21st Centuries. Chicago: Serindia Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Ba, Seinang. 1990. dba’ bzhed 拔协. Translated by Jinghua Tong. Chengdu: Sichuan Nationalities Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Callieri, Pierfrancesco, and Jiafeng Cheng. 2013. Giuseppe Tucci as Archaeologist. Journal of Tibetology 8: 130–41+205. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Fulin 陈福麟. 2023. Mingqing shiqi zangchuan fojiao gelupai chuanbo yu zhungeerbu de xinqi 明清时期藏传佛教格鲁派传播与准噶尔部的兴起 [Gelug Sect of Tibetan Buddhism during the Rise of the Jungar Khanate]. Journal of the Western Mongolian Studies 2: 38–47+126. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Yaodong 陈耀东. 1994. Xialusi: Yuan guanshi jianzhu zai Xizang de zhenyi 夏鲁寺:元官式建筑在西藏地区的珍遗 [Shalu Temple: The Precious Remains of Yuan Official Architecture in Tibet]. Cultural Relics 5: 35. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Yaodong 陈耀东. 2007. Zhongguo zangzu jiangzhu 中国藏族建筑 [Tibetan Architecture in China]. Beijing: China Architecture Industry Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dikshi, Sangay Gyatso. 2009. History of Gelugpa Teachings: The Yellow Glazed Book. Translated by Xu Decun. Lhasa: Tibetan People’s Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Dunga, Losang Chilie 东嘎·洛桑赤列. 2002. Dongga zangxue da cidian 东嘎藏学大辞典 [Dunga Dictionary of Tibetan Studies]. Beijing: China Tibetology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Qingyuan 傅清远, and Liping Wang 王立平. 2015. Chengde waibamiao 承德外八庙 [Chengde Eight Outer Temples]. Beijing: China Architecture Industry Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Qi 高琦, Xiangwu Meng 孟祥武, and David Luo 罗戴维. 2019. Labolengsi zhi jianzhu yingzao jiyi yu chuancheng 拉卜楞寺之建筑营造技艺与传承 [Building Construction Techniques and Inheritance of Labrang Temple]. Journal of Xi’an University of Architecture 10: 731. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, Ian N. 2003. A Place in History: A Guide to Using GIS in Historical Research. Oxford: Oxbow Books. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Ying 韩瑛, Hao Li 李昊, Xiuli Zhu 朱秀莉, and Changming Yang 杨昌鸣. 2021. Qing alashanqi zangchuan fojiao simiao de shidong fengbu tezheng yanjiu 清阿拉善旗藏传佛教寺庙的时空分布特征研究 [Research on the Temporal and Spatial Distribution Characteristics of Tibetan Buddhist Temples in Alashan Qi in the Qing Dynasty]. World Architecture 4: 82–86. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, Lily. 2001. Mapping ‘New’ Geographies of Religion: Politics and Poetics in Modernity. Progress in Human Geography 25: 211–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Shangquan 李尚全. 1993. Tubo fojiao shilun 吐蕃佛教史论 [History of Buddhism in Tubo]. Tibetan Studies 3: 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Dunzhen 刘敦桢. 2005. Zhongguo gudai jianzhushi 中国古代建筑史 [A History of Ancient Chinese Architecture]. Beijing: China Construction Industry Press, pp. 360–91+181. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Fengqiang 刘凤强. 2018. Baxie banben ji xiangguan wenti kaoshu 《拔协》版本及相关问题考述 [An examination of the editions of the Bakhyo and related issues]. Journal of Tibet University for Nationalities 6: 64–71. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Yuan 刘源. 1996. Yonghegong lishi 雍和宫历史 [The history of the Yonghe Palace]. Beijing Archives 2: 17. [Google Scholar]

- Longzhu, Dorje 龙珠多杰. 2016. Zangchuan fojiao siyuan jianzhu wenhua yanjiu 藏传佛教寺院建筑文化研究 [Research on the Architectural Culture of Tibetan Buddhist Temples]. Beijing: Social Science Literature Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Min, Tianyi 闵天怡, and Tong Zhang 张彤. 2021. Hanzang hebi jianzhu Fengge de yanjing 汉藏合壁建筑风格的演进 [Evolution of the architectural style of Sino–Tibetan joint wall]. China Ethnic News. August 26. Available online: http://www.mzb.com.cn/html/report/210832310-1.htm (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Ngawang, Lobsang Gyatso 昂旺罗桑嘉措. 2002. Xizang wangcheng ji 西藏王臣记 [A Record of Tibetan Kings and Ministers]. Translated by Liu Liqian. Beijing: Nationalities Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Puncog, Chabai Tsedan 恰白·次旦平措, Norzang Ugyen 诺章·吴坚, and Phuntshog Tsering 平措次仁. 1996. Xizang Tongshi: Lvsong Baochuan 西藏通史:绿松宝串 [The General History of Tibet: Turquoise Strings]. Lhasa: Tibet Antiquities Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Pu, Wencheng 蒲文成. 1990. Ganqing zangchuan fojiao siyuan 甘青藏传佛教寺院 [Ganqing Tibetan Buddhist Temple]. Xining: Qinghai People’s Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Qinze, Wangbu 钦则旺布. 2000. Weizang Daoba Shengshu Zhi. 卫藏道场胜迹志. Translated by Liqian Li. Beijing: Minzu Publishing House, pp. 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Shuo 石硕. 2014. Zangzu sanda chuantong dili quyu xingcheng guocheng tantao 藏族三大传统地理区域形成过程探讨 [Exploring the Formation Process of the Three Traditional Geographic Regions of the Tibetan]. China Tibetology 3: 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Sopher, David E. 1981. Geography and Religions. Progress in Human Geography 5: 510–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Bai 宿白. 2021. Zangchuan fojiao kaogu藏传佛教寺院考古 [Tibetan Buddhist temple archaeology]. Beijing: SDX Joint Publishing Company, pp. 120–41+183. [Google Scholar]

- Thorang, Wangdui 索朗旺堆, and Zhoude He 何周德. 1986. Shannan xian wengu zhi 山南县文物志 [Zhanan County Cultural Relics Journal]. Xi’an: Shanxi Provincial Printing House. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Guixiang 王贵祥. 2016. Zhongguo hanchuan fojiao jianzhu shi 中国汉传佛教建筑史 [The History of Chinese Han Buddhist Architecture]. Beijing: Tsinghua University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Seng 王森. 1997. Xizang fojiao fazhanshi lue 西藏佛教发展史略 [History of the Development of Buddhism in Tibet]. Beijing: China Social Sciences Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Shiren 王世仁. 2015. Chengde waibamiao de duo minzu jianzhu xingshi承德外八庙的多民族建筑形式. [Multi-ethnic architectural forms of the Eight Outer Temples in Chengde]. Art Panorama 7: 106–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Yongping 汪永平, Tingting Niu 牛婷婷, and Xiaomeng Zong 宗晓萌. 2021. Xizang zangchuan fojiao jianzhu shi 西藏藏传佛教建筑史 [A History of Tibetan Buddhistrchitecture]. Nanjing: Southeast University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Jisheng 谢继胜. 2018. Hanzang wenming de xingcheng yu duominzu Zhongguo wenming fazhanshi—yi 7–13 shiji hanzang yishu fazhan weili 汉藏文明的形成与多民族中国文明发展史—以7–13世纪汉藏艺术发展为例 [The Formation of Sino–Tibetan Civilization and the History of the Development of Multi-ethnic Chinese Civilization: Taking the Development of Sino–Tibetan Art from the 7th to 13th Centuries as an Example]. Chinese Social Science Today. February 23. Available online: https://epaper.csstoday.net/mepaper/mobile/paper/pageList?pubCode=zgshkxb&pubDate=2018-02-23&pageTitle=1 (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Xie, Jisheng 谢继胜, and Ziying Man 满孜颖. 2021. The Progress of Tibetan Art Research in the Last 70 Years. China Tibetology 1: 59–80. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Jiaming 杨嘉铭. 2003. Xizang jianzhu de lishi wenhua 西藏建筑的历史文化 [The History and Culture of Tibetan Architecture]. Xining: Qinghai People’s Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Yingwei, Kenneth Dean, Chen Chieh Feng, Guan Thye Hue, Khee heong Koh, Lily Kong, Chang Woei Ong, Arthur Tay, Yichen Wang, and Yiran Xue. 2020. Chinese Temple Networks in Southeast Asia: A WebGIS Digital Humanities Platform for the Collaborative Study of the Chinese Diaspora in Southeast Asia. Religions 11: 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Jianlin 张健林. 2017. Zhuixun wangri huihuang: Sajiabeisi kaogu ji 追寻往日辉煌:萨迦北寺考古记 [In Search of Past Splendor: An Archaeological Record of the Sakya Northern Temple]. China Tibet 2: 57. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Pengju 张鹏举. 2012. Neimenggu zangchuan fojiao jianzhu 内蒙古藏传佛教建筑 [Inner Mongolia Tibetan Buddhism Architecture]. Beijing: China Construction Industry Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Gaiping 赵改萍. 2009. Yuanming shiqi zangchuan fojiao zai neidi de fazhan ji yingxiang 元明时期藏传佛教在内地的发展及影响 [A Study of Tibetan Buddhism Depend on Development of Inland and Effect in Yuan and Ming Dynasty]. Beijing: China Social Sciences Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Yexi, and Shuming Bao. 2014. Space–Time Analysis of Religious Landscape in China. Tropical Geography 34: 591–98. [Google Scholar]

| Stage | Temporal Scale | Description |

|---|---|---|

| First Stage (T1) | 633–977 AD | Includes the Tubo period (633–842 AD), also known as the pre-propagation period of Tibetan Buddhism; the period of division and fragmentation (843–977 AD) |

| Second Stage (T2) | 978–1246 AD | From the beginning of the post-propagation period of Tibetan Buddhism to the establishment of the Sakya local regime |

| Third Stage (T3) | 1247–1367 AD | From the establishment of the Sakya local regime (Tibet was incorporated into the Yuan Dynasty) to the end of the Yuan Dynasty |

| Fourth Stage (T4) | 1368–1643 AD | Ming Dynasty |

| Fifth Stage (T5) | 1644–1796 AD | From the early Qing Dynasty to the mid-Qing Dynasty |

| Quantitative Ranking | Province/ Municipality | Number of Temples | Proportion | Average Kernel Density |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Xizang | 530 | 30.8% | 11.15 |

| 2 | Sichuan (Ganzi, Aba, etc.) | 464 | 27% | 22.95 |

| 3 | Qinghai | 366 | 21.3% | 13.08 |

| 4 | Gansu | 105 | 6.1% | 6.73 |

| 5 | Inner Mongolia | 95 | 5.5% | 4.07 |

| 6 | Beijing | 74 | 4.3% | 52.31 |

| 7 | Yunnan (Diqing, Lijiang) | 44 | 2.6% | 5.84 |

| 8 | Xinjiang | 22 | 1.3% | 0.56 |

| 9 | Hebei (Chengde) | 12 | 0.7% | 0.72 |

| 10 | Shanxi (Wutaishan) | 8 | 0.5% | 0.98 |

| Kernel Density Ranking | Quantitative Ranking | State/Prefecture-Level City | Kernel Density | Number of Temples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8 | Beijing | 52.31 | 74 |

| 2 | 7 | Haidong, Qinghai | 45.81 | 89 |

| 3 | 10 | Xining, Qinghai | 43.74 | 39 |

| 4 | 5 | Lhasa, Xizang | 37.19 | 109 |

| 5 | 1 | Ganzi, Sichuan | 20.56 | 327 |

| 6 | 4 | Shannan, Xizang | 16.83 | 128 |

| 7 | 2 | Aba, Sichuan | 12.75 | 135 |

| 8 | 9 | Gannan, Gansu | 10.28 | 54 |

| 9 | 3 | Shigatse, Xizang | 11.16 | 133 |

| 10 | 5 | Yushu, Qinghai | 4.95 | 109 |

| Time Scale | Scale Length (Year) | Number of Temples | Proportion | Construction Density | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (T1) | 633–977 | 344 | 148 | 8.6% | 0.43 |

| (T2) | 978–1246 | 268 | 219 | 12.7% | 0.85 |

| (T3) | 1247–1367 | 120 | 244 | 14.2% | 2.03 |

| (T4) | 1368–1643 | 275 | 477 | 27.7% | 1.73 |

| (T5) | 1644–1796 | 152 | 632 | 36.7% | 4.16 |

| (Y1) | (Y2) | (Y3) | (Y4) | (Y5) | (Y6) | (Y7) | (Y8) | (Y9) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (T1) | 131 | – | – | – | 5 | 4 | – | 8 | – | 148 |

| (T2) | 189 | 9 | 19 | – | – | – | – | 2 | – | 219 |

| (T3) | 110 | 47 | 58 | 4 | 2 | 15 | – | 2 | 6 | 244 |

| (T4) | 112 | 138 | 170 | 2 | 1 | 39 | 2 | 1 | 12 | 477 |

| (T5) | 60 | 215 | 230 | 11 | – | 88 | 9 | – | 19 | 632 |

| Total | 602 | 409 | 477 | 17 | 8 | 146 | 11 | 13 | 37 | 1720 |

| Origin | Content | Similarities |

|---|---|---|

| Han Influence | Temple Site Selection | Geomancy |

| Wooden Structure System: Chashou (叉手, inverted V-shaped brace), Shuzhu (蜀柱, short post), Dougong (斗拱), and other wooden components | Consistent with the form and craftsmanship of Tang Dynasty components | |

| Mural techniques | Consistent with the meticulous painting methods of the Han region | |

| Tibetan Characteristics | Architectural Layout: Lacan Style | Consistent with local architecture |

| Architectural Colors | ||

| Influence from Nepal, India, and other regions | Decorative Art of Components such as Beams, Columns, and Lintels | Decorative Techniques |

| Temple Name | Construction Time | Location | Layout | Form | Style |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jokhang Temple 大昭寺 | 7th century | Lhasa | Buildings facing east–west | Lhakhang Form | Lacan Style (Y1), Han Style (Y6), Other Style (Y8) |

| Samye Temple 桑耶寺 | 763 | Zhanang County, Shannan | Layout imitating the ideal Buddhist kingdom with Mount Meru as the center | Lhakhang Form | Lacan Style (Y1), Han Style (Y6), Other Style (Y8) |

| Sakya South Temple 萨迦南寺 | 1268 | Shigatse | Square city layout | Lhakhang Form | City Style (Y4) |

| Shalu Temple 夏鲁寺 | Rebuilt in 1329 | Shigatse | Courtyard layout, buildings facing east–west | Sino–Tibetan Combined Form | Sino–Tibetan Combined Style (Y2) |

| Ganden Temple 甘丹寺 | 1409 | Dagzê County, Lhasa | Centered on Coqen Hall, layout according to the mountain | Dugang style, Sino–Tibetan Combined Form | Lacan Style + Sino–Tibetan Combined Style (Y3) |

| Drepung Temple 哲蚌寺 | 1416 | Lhasa | Centered on Coqen Hall, cascading layout according to hierarchy | Dugang style, Sino–Tibetan Combined Form | Lacan Style + Sino–Tibetan Combined Style (Y3) |

| Sera Temple 色拉寺 | 1419 | Lhasa | Centered on Coqen Hall, free layout from east to west | Dugang style, Sino–Tibetan Combined Form | Lacan Style + Sino–Tibetan Combined Style (Y3) |

| Tashi Lhunpo Temple 扎什伦布寺 | 1447 | Shigatse | Centered on Coqen Hall, layout according to the mountain | Dugang style, Sino–Tibetan Combined Form | Lacan Style + Sino–Tibetan Combined Style (Y3) |

| Kumbum Temple 塔尔寺 | 1560 | Huangzhong County, Qinghai | Centered on the Great Golden Tiled Hall | Dugang style, Sino–Tibetan Combined Form | Lacan Style + Sino–Tibetan Combined Style (Y3) |

| Labrang Temple 拉卜楞寺 | 1709 | Xiahe County, Gansu | Centered on Coqen Hall and the Great Golden Tiled Hall | Dugang style, Sino–Tibetan Combined Form | Lacan Style + Sino–Tibetan Combined Style (Y3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Min, T.; Zhang, T. Bidirectional Transmission Mapping of Architectural Styles of Tibetan Buddhist Temples in China from the 7th to the 18th Century. Religions 2024, 15, 1120. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15091120

Min T, Zhang T. Bidirectional Transmission Mapping of Architectural Styles of Tibetan Buddhist Temples in China from the 7th to the 18th Century. Religions. 2024; 15(9):1120. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15091120

Chicago/Turabian StyleMin, Tianyi, and Tong Zhang. 2024. "Bidirectional Transmission Mapping of Architectural Styles of Tibetan Buddhist Temples in China from the 7th to the 18th Century" Religions 15, no. 9: 1120. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15091120

APA StyleMin, T., & Zhang, T. (2024). Bidirectional Transmission Mapping of Architectural Styles of Tibetan Buddhist Temples in China from the 7th to the 18th Century. Religions, 15(9), 1120. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15091120