Abstract

The Huayansi 華嚴寺, situated at the frontier stronghold of the Liao Dynasty in the Western Capital, is a significant royal temple that preserves two main halls from the Liao and Jin Dynasties to this day. Through a systematic examination of the Liaoshi 《遼史》 and the related literature, this study offers a novel interpretation of the east–west dual-axial layout of the Huayansi and its historical significance. It further discusses the integral artistic space of the Buddha and the Dharma within the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall 薄伽教藏殿, which shapes the spiritual realm of the Western Pure Land, thereby repositioning and enhancing the historical value of the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall. The article elucidates the political and cultural core elements embedded within the formation of the parallel axes of the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall and the Mahavira Hall, which are closely associated with three pivotal years in the Liao Dynasty: 1038, 1044, and 1062. This not only reflects the grand historical context of the Liao Dynasty’s domestic governance and foreign policy during the 10th and 11th centuries but also encapsulates the rich and diverse religious beliefs and cultural traits of the Khitan 契丹 people. The axis space of the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall, constructed earlier during the reign of Xingzong 興宗 to house the Liao Canon 《遼藏》, along with the architectural complex of the Huayansi—named and commissioned by Emperor Daozong 道宗 24 years later—collectively establishes a dual-axial worship space at the Grand Huayansi, sanctified by the triad of the Buddha 佛, the Dharma 法, and the Ancestors 祖. This underscores the Liao Dynasty’s political objectives of deterring hostile states and ensuring national security within the framework of Buddhist veneration and ancestor worship.

1. Introduction

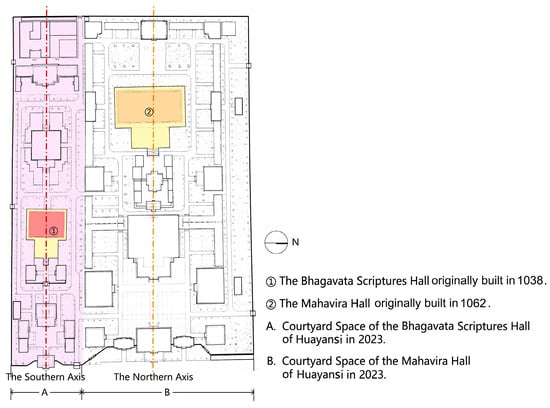

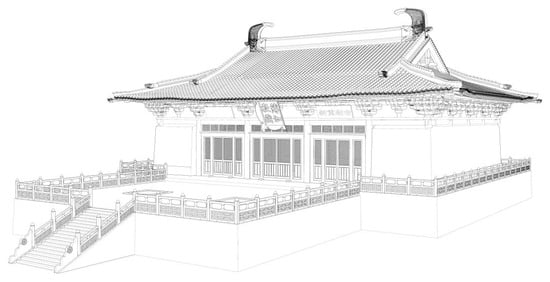

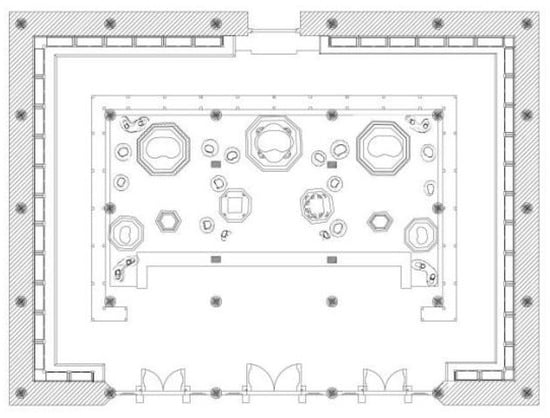

Huayansi1, the imperial temple of the Liao Dynasty, was located in the southwestern corner of the old city area and adjacent to the western city wall of Datong, Shanxi Province 山西省, the Western Capital of the Liao Dynasty. Unlike traditional Chinese temples, which typically face south, Huayansi extends along an east-west axis. Situated in a gently sloping area with the western side higher than the eastern side, the main halls face east. The two important halls, Mahavira Hali (Daxiong Baodian 大雄寶殿) and the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall (Boqie Jiaozang Dian 薄伽教藏殿 are located on separate parallel axes within the temple and are situated on elevated platforms. Each hall leads the layout of the other buildings along their respective axes, forming two sets of parallel courtyards running east to west. This arrangement contrasts with the typical spatial pattern of traditional Chinese temple complexes, which are usually organized around a central axis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overall plan of the current dual-axis alignment at Huayansi (drawing by the author’s research team2, reference map: (, Huayansi pingmian shiyitu)).

Academic studies on Huayansi have predominantly focused on the wooden structural systems of the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall and the Mahavira Hall. Representative research works include Liang Sicheng and Liu Dunzhen’s paper “Datong Gujianzhu Diaocha Baogao” (); Qi Ping, Chai Zejun, Zhang Wu’an, and Ren Yimin’s book Datong Huayansi (Shangsi) (); Liu Xiangyu’s doctoral dissertation Datong Huayansi Ji Boqie Jiaozang Dian Yanjiu (); and Nancy Shatzman Steinhardt’s book Liao Architecture (). No specialized studies have been conducted on the axial space of Huayansi. Based on a comprehensive review and textual research of the Liaoshi 《遼史》 and the related literature, this study innovatively proposes a new interpretation and historical significance of the east-west dual-axis layout of Huayansi.

Huayansi, established by imperial decree during the Liao Dynasty, received its name from the same. Historical documents, inscriptions, and field investigations reveal that the main halls along the dual axes of Huayansi were constructed in different periods. The Mahavira Hall, located along the northern axis, was originally erected in the eighth year of the Qingning 清寧 period of the Liao Dynasty (1062). During the second year of the Baoda 保大 period of the Liao Dynasty (1122), the Jin 金 army invaded and took control of the western capital, leading to significant destruction at Huayansi. The current structure of the Mahavira Hall was reconstructed by monks who raised funds from the public between the third and fourth years of the Tianjuan 天眷 period (1140–1144) of the Jin Dynasty3. This hall stands as a wooden architectural masterpiece. On the southern axis, the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall was established in the seventh year of the Zhongxi period of the Liao Dynasty (1038), 24 years before Huayansi was named. It was built to accommodate the imperial block-printed Tripitaka of the Liao Dynasty, known as the Liao Canon 《遼藏》 (Liaozang). Since its initial construction, the hall’s spatial arrangement has been preserved exceptionally well, including the wooden sutra cabinets and painted clay sculptures dating back to the Zhongxi period.

The two main halls of the extant Huayansi were constructed at different times and served distinct functions, with the original appearance of those built during the Liao Dynasty differing accordingly. This study examines the political and diplomatic systems of the Liao Dynasty from the 10th to 11th centuries, uncovering the political and cultural core elements embedded in the formation of the dual parallel axes. It elucidates the historical events that occurred in three pivotal years—1038, 1044, and 1062—and underscores their close association with the construction process of Huayansi in the Western Capital. Building upon this, the study delves into the religious and cultural content and the spatial arrangements for worship rituals at Huayansi, tracing the original intentions of the Liao Dynasty’s royal family in establishing the temple. It interprets the historical significance and political appeals inherent in the dual-axis worship space sanctified by the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Ancestors. Furthermore, it presents the religious beliefs, political intentions, and ambitions for state governance embodied in the temple’s worship spaces by the Liao Dynasty (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The Bhagavata Scriptures Hall retains its overall artistic appearance from the Zhongxi period of the Liao Dynasty (photos by the author).

2. The Rise of Western Capital in the Liao Dynasty: Political and Diplomatic Strategies from the 10th to the 11th Centuries

The Liao Dynasty established its Western Capital in 1044, with the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall constructed in 1038 and the Mahavira Hall of Huayansi built in 1062. These three pivotal years are intricately linked to significant historical events, including the completion of the Liao Canon, which was carved and printed during the reigns of Emperors Shengzong, Xingzong, and Daozong. This period also saw complex political, diplomatic, and military interactions between the Liao Dynasty and its neighbors, such as the Bohai State 渤海國, Xi State 奚國, Goryeo 高麗, Western Xia 西夏, and the Song Dynasty 宋. Furthermore, this era was characterized by shifts in territorial boundaries, the establishment of the Five Capitals, the continuation of religious worship and ceremonial practices, and urban development following the designation of Yunzhou as the Western Capital.

2.1. The Five Capitals System of the Liao Dynasty and Diplomatic Relations with Neighboring States in the 10th and 11th Centuries

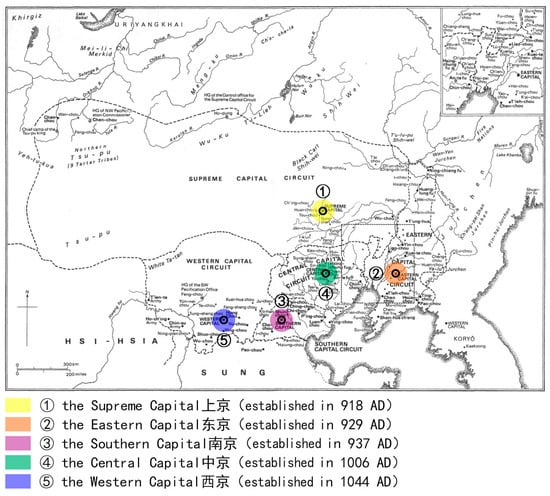

The nomadic traits of the Khitan (Qidan 契丹) pastoralists are evident in the 219-year imperial lifestyle of the Liao Dynasty. This is exemplified by the administrative system of the Five Capitals (Wujing 五京) (Figure 3) in the Liao Dynasty, where the emperor and his extensive court officials did not reside permanently in any of the Five Capitals—the Supreme Capital 上京 (Shangjing), the Eastern Capital (Dongjing 東京), the Southern Capital (Nanjing 南京), the Central Capital (Zhongjing 中京), and the Western Capital (Xijing 西京). Instead, they lived a nomadic lifestyle, conducting year-round inspection tours, sacrificial ceremonies, and hunting, moving with the four seasons and setting up temporary encampments known as “Nabo” (nabo 捺缽) (). Volume 68 of the Liaoshi documents the unique lifestyle of the Liao emperors, including their daily governance, inspection tours, sacrificial rituals, and hunting activities around the Nabo and the Five Capitals. The principal adversaries of the Liao Dynasty during the 10th and 11th centuries were primarily the Central Plains dynasties that emerged and declined around the Five Dynasties period, along with neighboring countries such as the Song Dynasty, Western Xia, Goryeo, the Bohai Kingdom, and the Xi State. The establishment of the Five Capitals was also a result of the Liao Dynasty’s political diplomacy, warfare, and territorial integration with neighboring states and tribes.

Figure 3.

Distribution map of the Five Capitals of the Liao Dynasty in the 10th–11th centuries (drawing by the author’s research team, reference map: (, Map 7. The Liao empire, Ca. 1045)).

From the establishment of the Supreme Capital (Linhuang 臨潢, now Boroo city 波羅城 in Mongolia) in the third year of the Shence 神冊 period of Liao Taizu 遼太祖 (918) to the establishment of the fifth capital, the Western Capital, in the thirteenth year of the Zhongxi period of Emperor Xingzong 興宗 (1044), it took 126 years to complete the administrative division of the Five Capitals and Five Circuits (Wudao 五道). This was closely related to the political diplomacy of the Liao Dynasty, especially with the states engaged in wars during the 10th and 11th centuries, including the Song Dynasty, Western Xia, Goryeo, Bohai State, and Xi State. In the first year of the Tianxian 天顯 period (926), Liao Taizu conquered the Bohai State within two months (), renaming it the “East Dan State” (Dongdan Guo 東丹國) and making it a vassal state of the Liao Dynasty. In 929 AD, the capital of the East Dan State was relocated to Dongping 東平, serving as the Southern Capital of the Liao Dynasty. In 937 AD, Shi Jingtang 石敬瑭, the puppet king of Later Jin (Houjin 後晉), acknowledged Liao Taizu as his father and pledged allegiance to the Khitan, offering sixteen prefectures from Yunzhou 雲州 to Youzhou 幽州 to Liao Taizu. Consequently, Yunzhou (now Datong 大同) became part of the Liao Dynasty’s territory, with Youzhou designated as the Southern Capital of the Liao Dynasty (now Beijing 北京), while the original Southern Capital, Dongping, was renamed the Eastern Capital(now Liaoyang 遼陽). From the military campaigns of Liao Taizu to the administrative reforms of Emperor Shengzong 聖宗, the state ruled by the Xi State king was fully integrated into the Liao Dynasty as its vassal state in 997 AD. In 1006 AD, the former capital of the Xi State was designated as the Central Capital of the Liao Dynasty (now Tianyi Town 天義, Ningcheng County 寧城, Chifeng City 赤峰, becoming the second most important capital after the Supreme Capital. Thus, the Liao Dynasty had four capitals ().

2.2. Two Key Events in the Mid-11th Century: The Liao-Western Xia Confrontation (1038) and the Founding of the Western Capital (1044)

In the early 11th century, the Liao Dynasty had already annexed Bohai State and Xi State and had established long-term peaceful relations with Goryeo and the Song Dynasty through various means. By the mid-reign of Emperor Shengzong (982–1031), the emphasis on external relations had shifted to the rising power of Western Xia, which was growing increasingly influential in the southwest. The Tanguts 黨項 founded the Western Xia state in 963, and by the early 11th century, they had submitted to both the Song and Liao Dynasties, paying tribute to both. During Emperor Shengzong’s reign, in the years 997 and 1004, respectively, Li Jiqian 李繼遷 and Li Deming 李德明, rulers of Western Xia, were granted the titles of Prince of Xiping西平王, and their governance operated under a semi-autonomous model within the suzerainty of the dominant states (). Western Xia’s diplomatic strategy was inconsistent; it not only manipulated the relationships between the Liao and Song but also continuously engaged in localized conflicts with both allied states, expanding its territory in multiple directions. Additionally, it invested significant effort in competing with the Liao Dynasty for dominance over the western region inhabited by the Uyghurs (Huihu 回鶻). Its objectives were not only territorial acquisition but also the control of economic trade routes extending westward to the European continent.

In 1038, Li Yuanhao 李元昊, the king of Western Xia, declared himself the Emperor of Great Xia, usurping the imperial title and changing his surname to “Weiming” 嵬名 and first name to “Nangxiao” 曩宵, thereby completely severing ties with the Liao and Song. This action initiated the “Three-Power Stalemate” period among the Song, Liao, and Western Xia dynasties. Western Xia boldly sought equal diplomatic status with the Liao and Song, similar to the Treaty of Chanyuan 澶淵之盟 (Chanyuan Zhimeng), leading to dissatisfaction from the Liao court and a rapid deterioration of political relations ().

Also in 1038, another political event occurred that angered the Liao court: In the autumn of 1031, Emperor Xingzong ascended the throne and immediately began to fulfill the promise made during the Shengzong 聖宗 period to arrange a wedding for Li Yuanhao, the son of the Prince of Xiping Li Deming. In the twelfth month of the same year, Princess Xingping 興平公主 was married off to Li Yuanhao as his consort, and Li Yuanhao was titled Duke of Xia State (Xia Guowang 夏國公) and Imperial Son-in-law Commander (Fuma Duwei 駙馬都尉). Later, he was further titled King of Xia State (Xia Guowang 夏國王). In 1038, Princess Xingping passed away mysteriously. At that time, Li Yuanhao was preoccupied with his imperial ambitions and did not formally notify the Liao court of the proper imperial rites. Xingzong was furious and dispatched envoys carrying an imperial decree to “question the reason” (jie qigu 詰其故) (), leading to a further falling out between the Liao Dynasty and Western Xia.

The eventful seventh year of Zhongxi (1038) coincided with the construction of the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall, where inscriptions indicating the year of construction were made under its beam. The development of these political events is inevitably intertwined with the construction of the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall and its monastery complexes, indicating an inseparable internal connection. In the first month of the sixth year of Zhongxi (1037), Xingzong “went on a westward inspection tour” (xixing 西幸) (). Although the specific location of his tour was not mentioned, it is reasonable to assume that the destination included the major western stronghold of Yunzhou. It can be inferred that this westward inspection tour was aimed directly at countering the expansion ambitions of the neighboring Western Xia. Therefore, the construction of the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall complex could be considered part of the overall defensive layout of the western border regions of the Liao Dynasty.

In 1044, several tribes from the western territories of the Liao defected to Western Xia, prompting Li Yuanhao to support the rebels. That same year, Western Xia signed a treaty with the Song. In the tenth month of the thirteenth year of the Zhongxi period (1044), Xingzong mobilized a large army and invaded Western Xia through three routes, citing this as a pretext. In the eleventh month, “Xingzong was defeated by Li Yuanhao, with a narrow escape on his own” (Xingzong baiyu Li Yuanhao ye, danji tuchu, ji budetuo) (, 興宗敗於李元昊也, 單騎突出, 幾不得脫). The Battle of Hequ 河曲之戰 resulted in a major defeat, forcing Xingzong to retreat from Yunzhou back to the Liao territory. Yunzhou, situated at the intersection of the territories of the Liao, Western Xia, and Song, was a crucial stronghold in the southwest guarded by the Liao. Four days after returning from the western campaign in the eleventh month, Xingzong declared that Yunzhou would be renamed the Western Capital as one of Liao’s auxiliary capitals and established the Western Capital Circuit (Xijing Dao 西京道) with the capital at Datong Prefecture (), thus completing the local administrative system of the Liao Dynasty with the Five Capitals as its center and Five Circuits established around them.

The campaign to invade Western Xia having failed, Xingzong was frustrated. He immediately embarked on an inspection tour westward in the twelfth month of the year (), personally overseeing the enhancement of urban facilities and military defenses in the Western Capital. “Thus constructing the Western Capital with enemy monitoring towers and wooden watchtowers, extending over twenty li, with gates named Yingchun 迎春 to the east, Chaoyang 朝陽 to the south, Dingxi 定西 to the west, and Gongji 拱極 to the north. Only princes were allowed to control this important area” (Yinjian Xijing, Dilou, Penglu ju, guangmao ershili, men, dongyue Yingchun, nanyue Chaoyang, Xiyue Dingxi, beiyue Gongji……yongwei zhongdi, fei qingwang bude zhuzhi 因建西京,敵樓、棚櫓具,廣袤二十裏,門,東曰迎春,南曰朝陽,西曰定西,北曰拱極。……用爲重地,非親王不得主之) (). This transformed it into an impregnable stronghold on the western border, intended for long-term defense against both the Song and Western Xia, and prepared thoroughly for the next expedition against Western Xia and further expansion. The naming of the western city gate as “Dingxi Gate” (Dingxi men 定西門, the gate of pacifying the west) indicates the determination of the Liao court to pacify Western Xia and subdue Li Yuanhao, compelling him to once again submit to their authority.

From the completion of the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall in 1038 to the grand inauguration of the Huayansi, which was bestowed its name by imperial decree in 1062, this imperial temple of the Liao Dynasty was never confined to a singular model of Buddhist worship space. Instead, it was imbued with the protective powers of the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Ancestors to counteract the expansionist ambitions of neighboring states and safeguard the tranquility of the Liao Dynasty’s borderlands. Its establishment was closely linked to the political exchanges and conflicts between the Liao Dynasty and neighboring entities such as the Bohai State, Xi State, Goryeo, the Song Dynasty, and Western Xia, as well as the various tribes of Zubu and Nüzhen. Particularly after the mid-11th century, efforts were directed towards mitigating the threat posed by the rise of Western Xia in the southwestern region. The historical events in Liao foreign relations and domestic affairs during the Xingzong period in 1038 and 1044 were intricately intertwined with the construction of the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall, the establishment of the Western Capital, and the imperial decree to construct the Huayansi during the Daozong period in 1062.

3. Initial Construction (1038) and Merger (1062): Integration of Bhagavata Scriptures Hall and Huayansi in the Western Capital

3.1. 1038: Establishment of the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall for the Liao Canon

3.1.1. 1038: A Historical Milestone in the Printing History of the Liao Canon

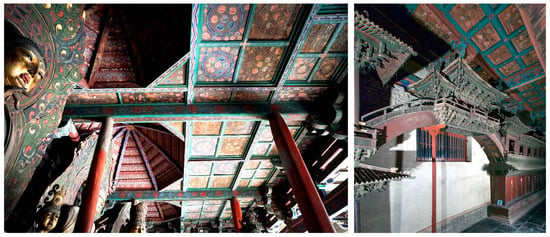

Since its completion in the seventh year of the Liao Dynasty’s Zhongxi period (1038), the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall has stood for 986 years until now, making it one of the only eight major wooden constructions from the Liao Dynasty that remain in China today (). The original Liao-era structure of the main hall featured a large wooden load-bearing system, the three main Buddha statues and their accompanying Bodhisattva groups, the caisson ceiling (Zaojin 藻井) and the checkered ceiling (Pingqi 平棊), as well as sutra cabinets for storing the Liao Canon () along the four walls of the hall (Figure 4). These elements were adorned with colorful paintings and gilding, complemented by bracket sets and various types of wooden sculptural decorations. This comprehensive preservation of the artistry, combining large woodwork, small wood components, and sculpture from the Liao period, maintains the integrity of its original artistic form, making it a uniquely characteristic cultural heritage building among the great Liao structures.

Figure 4.

Left: Colorful paintings and gilding on the caisson ceilings and checkered ceilings in the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall. Right: Sutra cabinets for storing the Liao Canon along the four walls of the hall (photos by the author).

Interpreting the name “Bhagavata Scriptures Hall”, “Bhagavata” is derived from the Sanskrit word “ ” (Bhagavat), meaning “the Blessed One”, which is one of the ten titles of Shakyamuni Buddha. “Scriptures Hall” refers to a repository for Buddhist scriptures. Therefore, it can be surmised that the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall is a place for storing Buddhist scriptures, specifically designated for housing the Liao Canon, a comprehensive Buddhist canon printed with woodblocks commissioned by the Liao Dynasty. The plaque hanging in the center of the main hall, inscribed with “Bhagavata Scriptures Hall” (Figure 5), carries the special significance of preserving both the worship of Buddha and Buddhist scriptures.

” (Bhagavat), meaning “the Blessed One”, which is one of the ten titles of Shakyamuni Buddha. “Scriptures Hall” refers to a repository for Buddhist scriptures. Therefore, it can be surmised that the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall is a place for storing Buddhist scriptures, specifically designated for housing the Liao Canon, a comprehensive Buddhist canon printed with woodblocks commissioned by the Liao Dynasty. The plaque hanging in the center of the main hall, inscribed with “Bhagavata Scriptures Hall” (Figure 5), carries the special significance of preserving both the worship of Buddha and Buddhist scriptures.

Figure 5.

Plaque of the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall (photo by the author).

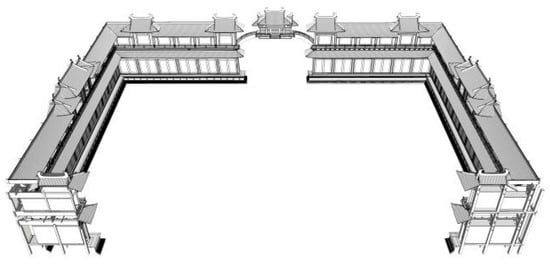

The initial construction and related information of the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall were not recorded in historical documents from the Liao, Jin, and Yuan dynasties. Only a few later inscriptions from restoration efforts mention it. The exact completion date of the seventh year of the Zhongxi period of the Liao Dynasty (1038) is derived from an inscription on the southern side of the main hall, on the bottom of the rafters: “Built on the fifteenth day of the ninth month of the seventh year of the Zhongxi period, at noon” (Wei Chongxi qinian suici Wuyin jiuyue Jiawu shuo shiwuri Wushen wushi jian 維重熙七年歲次戊寅玖月甲午朔十五日戊申午時建). Along the four walls of the hall, two-storey-high double-eaved scripture cabinets, approximately 5.5 m tall, were constructed, which were named “Bizang and Tiangong Louge” 壁藏與天宮樓閣. The lower level is the Bizang (the sutra storage cabinet 壁藏), which was used to store scriptures, while the upper level served as a Buddha niche, connecting all the Tiangong Louge (heavenly palace tower-pavilions 天宮樓閣) () by the Xinglang (corridor 行廊), mimicking the form of a large palace complex. In the middle of the west wall, a Feihongqiao (rainbow bridge 飛虹橋) and Tiangong Louge spanned the space, enclosing groups of Buddha and Bodhisattva statues, presenting an exquisitely decorated space for worship (Figure 6). The Bhagavata Scriptures Hall was built specifically to house the Liao Canon. The year 1038, as the clear construction date, has become one of the important historical landmarks for verifying the version and carving time of the Liao Canon.

Figure 6.

Overview of the sutra cabinets in the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall: Bizang and Tiangong Louge mimicking the style of a large palace complex (drawing by the author’s research team).

3.1.2. The Multi-Edition Liao Canon: Carved during the Reigns of Emperors Shengzong, Xingzong, and Daozong

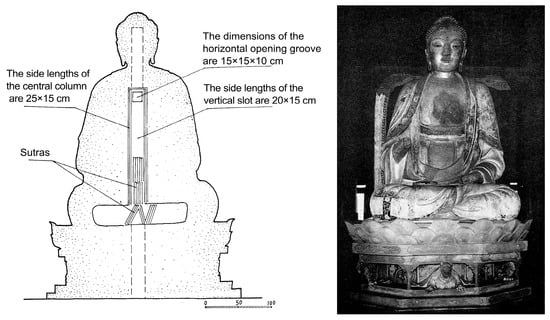

For a long time, no surviving scriptures of the Liao Canon were known, and historical records about it were scarce. It was not until July 1974 that parts of the original scrolls of the Liao Canon were discovered inside the statue of Shakyamuni Buddha on the fourth level of the Fogongsi Shakyamuni Pagoda (Fogongsi Shijia Ta 佛宮寺釋迦塔) in Yingxian County 應縣, Shanxi Province. This marked the first time in centuries that the lost Liao Canon appeared before the public in the form of woodblock-printed paper scriptures. This discovery confirmed the existence of different versions of the Liao Canon, carved during the reigns of Emperor Shengzong, Xingzong, and Daozong, and it finally revealed the comprehensive work of the Liao court in collecting, organizing, and printing the Buddist scriptures (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of the hidden space containing the Liao canon inside the Shakyamuni Buddha statue on the fourth floor of the Fogongsi Shakyamuni Pagoda (drawing created by the author’s research team, reference figure: ).

The academic community refers to the Tripitaka produced during the Tonghe period of Emperor Shengzong (983–1012), known as the “Shengzong Edition”, which was in scroll format, totaling 505 sets (zhi 帙) and 5,314 volumes (juan 卷) (), preserving the format of ancient Chinese Buddhist scriptures. The Tripitaka produced during the Zhongxi period of Emperor Xingzong (1032–1055) to the Xianyong 鹹雍 period of Emperor Daozong (1065–1075) is known as the “Zhongxi-Xianyong Edition”, which includes an additional 74 sets compared to the “Shengzong Edition”, totaling 579 sets () and approximately 6000 volumes (). This edition is available in two different woodblock printing formats: large-character scroll editions and small-character booklet editions ().

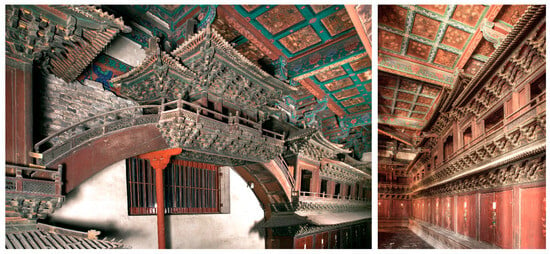

According to the Liaoshi, in the second month of the fourth year of the Xianyong period (1068), the Yuzhi Huayanjing Zan 禦制華嚴經贊 was promulgated (), signifying the official historical record of the carving and promulgation of the “Zhongxi-Xianyong Edition” of the Liao Canon. Concurrently, the inscription on Yangtai Shan Qingshui Yuan Chuangzao Cangjing Ji 陽臺山清水院創造藏經記 in Dajuesi 大覺寺, located in the West Mountain of Beijing and dated to the fourth year of Daozong’s Xianyong period (1068), records that “the imprint of the Tripitaka consists of a total of 579 sets, establishing both internal and external collections and placing them in niches” (ying Dazangjing fan wubaiqishijiu zhi, chuang neiwai zang er kancuo zhi 印大藏經凡五百七十九帙,創內外藏而龕措之) (). Indicating that by 1068 at the latest, the “Zhongxi-Xianyong Edition” of the Liao Canon had been carved and stored in niches (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Left: The appearance of heavenly palace tower-pavilions in the hall; Right: The appearance of the sutra cabinets in the hall (photos by the author).

The construction of the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall seems to have been a part of Emperor Xingzong’s comprehensive plan for the recompilation of the Liao Canon (). Initially, in the seventh year of Xingzong’s reign (1038), the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall was built to house the “Tonghe Edition” of the Liao Canon, which had been written or carved gradually before the twenty-first year of Shengzong’s reign (1003). Subsequently, the editing and carving of the “Zhongxi-Xianyong Edition” of the Liao Canon commenced, and the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall awaited the completion of this newer and more comprehensive edition to incorporate into its collection. The monk Jueyuan 覺苑, who participated in the compilation of the Liao Canon during the Daozong period, recorded in the Darijing Yishi Yanmicha 大日經義釋演密鈔 “When our Great Liao Emperor Xingzong reigned, he had a profound interest in the teachings of Buddhism, aiming to propagate them far and wide. He ordered meticulous carving and required thorough examination. Jueyuan, entrusted with the imperial decree, humbly participated in the editorial field” (ji wo DaLiao Xingzong yuyu, zhihong zangjiao, yu ji xia’er, cijin diaosou, xvren xiangkan, Jueyuan chicheng lunzhi, tianyu jiaochang 洎我大遼興宗禦宇,志弘藏教,欲及遐邇,敕盡雕鎪,須人詳勘,覺苑持承綸旨,忝預校場) (Jueyuan 1077, p. 9).

The extant stone inscription from the second year of the Jin Dynasty ’s Dading大定 period (1162), written by Duanzi Qing 段子卿, titled Dajinguo Xijing Da Huayansi Chongxiu Boqiejiaozang Ji 大金國西京大華嚴寺重修薄伽藏教記, mentions the following “During the Liao Dynasty’s Zhongxi period, there was a further revision and verification, and it was standardized into five hundred and seventy-nine sets, as recorded in the Ruzanglu 《入藏錄》 (Catalog of Texts Entering the Collection) by Master Taibao 太保. Therefore, the Grand Huayansi has also possessed these scriptures since ancient times”(ji youliao Zhongxi jian, fujia jiaozheng, tongzhi wei wubaiqishijiu zhi, ze you Taibao dashi Ruzanglu ju zhaizhi yun, jin ci Dahuayansi congxi yilai yiyou shi jiaodian yi 及有遼重熙間,複加校證,通制為五百七十九帙,則有太保大師《入藏錄》具載之雲,今此大華嚴寺從昔以來亦有是教典矣) (). These records serve as historical evidence of the collection of the newly printed “Zhongxi-Xianyong Edition” of the Liao Canon in the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall.

3.2. 1062: Merging—The Construction and Naming of Huayansi by Imperial Decree in the Western Capital

The construction time of Huayansi is documented in various historical texts. The earliest mention of the Western Capital Circuit is found in the Geographical Records (Dili Zhi 地理志) in the Liaoshi: “Huayansi was built in the eighth year of the Qingning period, and imperial stone and bronze statues enshrined” (Qingnin banian jian Huanyansi, feng’an zhudi shixiang, tongxiang 清寧八年建華嚴寺,奉安諸帝石像、銅像) (). In the thirteenth year of Emperor Xingzong‘s Zhongxi period (1044), Yunzhou was promoted to be the Western Capital, establishing Datong Prefecture and vigorously developing the urban construction of the Western Capital. The mention of Huayansi in the Liaoshi as being built in the eighth year of Qingning (1062) should be understood as an expansion rather than its initial establishment. By the seventh year of Xingzong’s Zhongxi period (1038), the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall, which housed the Liao Canon, had already been constructed, indicating that “Before Qingning period, this temple already had scripture storage, and its scale was by no means small” (shi Qingning qian, cisi yiyou jiaozang, qi guimo juefei xialou kezhi 是清寧前,此寺已有教藏,其規模絕非狹陋可知) ().

The expanded function of Huayansi, undertaken in the eighth year of the Qingning period, was to “enshrine imperial stone and bronze statues”, thereby converting it into a venue for the imperial family’s ancestral worship. This enlargement not only augmented the temple’s scale and stature but also resulted in its naming as Huayansi by Emperor Daozong. The newly expanded Huayansi amalgamated with the previously built Bhagavata Scriptures Hall and its architectural ensemble, evolving into a multifunctional, large-scale imperial temple. This temple complex encompassed functions such as scripture storage, Buddhist worship, and ancestor veneration. It was commemorated as “Grand Huayansi” in inscriptions from the Jin, Yuan, and Ming dynasties.

In 1062, upon the completion of the expansion of Huayansi, Emperor Daozong “visited the Western Capital” (xing Xijing 幸西京) in the twelfth month of this year, and five days later “performed the Rebirth Ritual for the Empress Dowager” (yi huangtaihou xing zaishengli 以皇太后行再生禮) ().

Although the specific venue for the ceremony is not mentioned, it is stated that “In the eighth year of Qingning, Huayansi was built, and stone and bronze statues of various emperors were enshrined there”. This national grand ceremony was likely recorded in the Liaoshi as a result. From this, it can be inferred that the ceremonial location must have been in the newly commissioned Huayansi, where Emperor Daozong, accompanied by the Empress Dowager, conducted a grand rebirth ceremony.

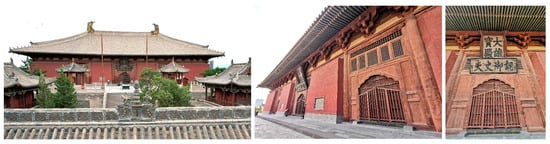

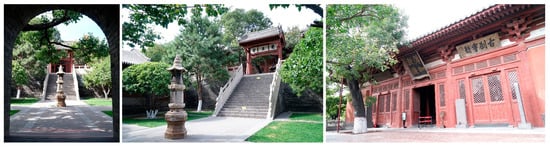

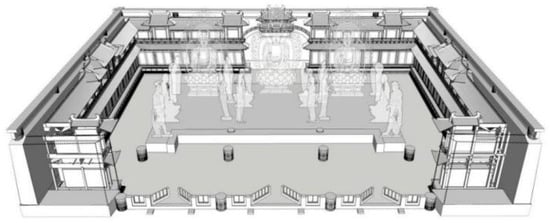

This highlights the new function of Grand Huayansi in hosting significant imperial rituals, such as ancestor worship and rites of rebirth, in addition to its roles in scripture storage, Buddhist worship, and the propagation of Buddhist teachings (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

The north axis of Huayansi and the Mahavira Hall reconstructed during the Jin Dynasty (photos by the author).

The inscription beneath the beam indicates that the construction of the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall occurred in the third year of the Zhongxi period (1038). This chronological point holds significant historical importance, as it is 24 years prior to the construction of the Huayansi complex in the eighth year of Emperor Daozong’s Qingning period (1062). By adhering to the architectural customs of the Khitan people, who favored an eastward orientation, and thus adopting an east-west axial system, the arrangement of Buddha statues and ceremonial spaces within the hall formed a cohesive whole. The prior completion of the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall influenced and dictated the organizational structure of the Huayansi complex. The axial layout of the newly expanded Huayansi complex followed the east-west pattern of the original Bhagavata Scriptures Hall complex. These two complexes run parallel to each other, unveiling two sets of temple buildings from west to east. The spatial arrangement of the initial Bhagavata Scriptures Hall complex, intended for housing the Liao Canon, informed the layout of the new Huayansi complex, presenting a dual-axis layout pattern of worship space organization characterized by parallel arrangement and equal emphasis on two functions.

4. Hidden Political Intentions: The Worship Space of Huayansi Empowered by the Triple Blessings of Buddha, Dharma, and Ancestors

4.1. Dual-Axis Worship Space of Huayansi and Its Liao to Jin Dynasty Remnants

In addition to enshrining the Three Jewels of the Buddha (Fobao 佛寶), the Dharma (Fabao 法寶), and the Sangha (Sengbao 僧寶), like regular temples, the Dharma 法寶 of Huayansi are not ordinary scriptures but the imperial-made Liao Dynasty’s Great Tripitaka Liao Canon. Huayansi also serves as an imperial ancestral shrine, creating a space that combines the functions of worshipping the Buddha, preserving scriptures, and worshipping ancestors. The unique functional organization of Huayansi, along with the dual-axis worship structure formed by the merging of the two temples, is very rare in traditional Chinese temple architecture.

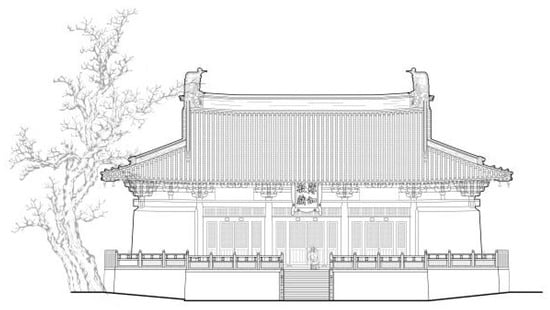

The southern axis of Huayansi is a worship space where the Buddha and the Dharma intersect. Constructed in 1038, the temple complex retains just one Liao Dynasty edifice, the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall, which stands as the sole surviving Liao Dynasty wooden structure within Huayansi. The main hall faces east, spanning a five-bay width of approximately 25.7 m and a depth of around 18.5 m. It features a single-eave gable and hip roof, elevated on a 3.5 m high terrace. To better support the extensive majestic sutra cabinet, only the central three bays of the east main entrance are equipped with floor-to-ceiling doors and windows, flanked by solid brick walls, and the back west facade lacks doors, offering just a small high window in the center of the inner hall (Figure 10). The structure integrates eight types of indoor and outdoor bracket sets that connect the wall columns to the roof. The exterior eave bracket sets on column heads are 5-puzuo 鋪作 with two jumps, while the intermediate bracket sets feature 4-puzuo 鋪作 with a single jump, positioned one set per bay. This overall timber framework demonstrates a clear and concise load distribution (Figure 11), accentuating the architectural style of the Liao Dynasty, which reflects the Tang Dynasty’s elegance, presenting a robust and stable appearance ().

Figure 10.

East facade of the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall (drawing by the author’s research team).

Figure 11.

Perspective of the Bhagavat Scriptures Hall on the tall terrace (drawing by the author’s research team).

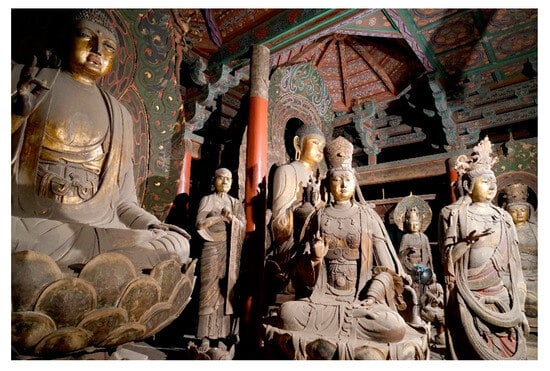

On the Sumeru throne in the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall, there are three groups of Buddha and Bodhisattva statues, surrounded by sutra cabinets that once held the Liao Canon, forming a dual worship space that embodies the coexistence of the Buddha and the Dharma. Worshippers pass through the mountain gate and inner courtyard, ascend the steps to the platform, and from the shifting axis of the space, view the hall and statues from a distance, gradually approaching and admiring this dazzling and sacred environment. This design presents a space of reverence and awe in a gradual and impressive manner (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

The sequence of spaces for worshipping Buddha along the axis of the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall (photos by the author).

The northern axis of Huayansi is a space dedicated to the worship of both Buddha and ancestors, expanded in 1062 and granted the imperial name Huayansi, serving as a dual-purpose worship site. Unfortunately, all the temples and structures built during the Liao Dynasty have been destroyed, and the precise location of the remnants remains uncertain, with the current buildings being later reconstructions. Historical records indicate that during the second year of the Baoda period of the Liao Dynasty (1122), when the Jin army attacked the Western Capital, Huayansi, situated within the city walls, became a major battlefield. “It marked the beginning of the Jin Dynasty. The Jin army seized the Western Capital of Liao. Huayansi was fiercely attacked and severely damaged, with only the dining hall, kitchen, pagoda, Bhagavata Scriptures Hall, and the Portrait Hall of Master Situ 司徒 remaining” (fuyu benchao dakai zhengtong, tianbin yigu, ducheng sixian, diangelouguan, ererhuizhi, wei Zhaitang, Kuchu, Baota, Jingzang jishou Shitu Dashi Yingtang cunyan 伏遇本朝大開正統,天兵一鼓,都城四陷,殿閣樓觀,俄而灰之,唯齋堂、廚庫、寶塔、經藏、洎守司徒大師影堂存焉) (). The Mahavira Hall, the Yurong Hall for ancestral worship, and all significant Liao Dynasty structures along the northern axis were obliterated in this conflict. Sixty years after its expansion, Huayansi was abandoned due to the ravages of war.

It was not until the third year of the Jin Dynasty’s Tianjuan period (1140) that several eminent monks, including Master Tonglu, succeeded in raising funds to reconstruct the temple buildings, including the Mahavira Hall, on the remnants of the Liao Dynasty’s architecture. Thus, Huayansi was revived, albeit without fully restoring the complete architectural style of the Liao Dynasty on both the northern and southern axes (Figure 13). “They rebuilt Huayansi on its original site, constructing main halls with nine and seven bays, as well as the Cishi, Guanyin, and Demon-Subduing Pavilions, the Scripture Hall, Bell Tower, Temple Gate, and Side Hall, without setting a deadline, and it gradually took shape. However, the left and right chambers, surrounding corridors, and pavilions were still missing” (nai renqi jiuzhi, er tejian jiujian, qijian zhidian, you goucehng cishi, guanyin, xiangmo zhige, ji huijing, zhonglou, sanmen, duodian, bushe riqi, weihu youcheng, qi zuoyou dongfang, simian wulang, shang queru ye 乃仍其舊址,而特建九間、七間之殿,又構成慈氏、觀音、降魔之閣,及會經、鐘樓、三門、垛殿,不設期日,巍乎有成, 其左右洞房,四面廊廡,尚闕如也) ().

Figure 13.

Left: The southern axis of the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall (1038); Right: The northern axis of Huayansi Mahavira Hall (1062) (photos by the author).

The Mahavira Hall, reconstructed in 1140 during the Jin Dynasty, has been preserved through the Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties to the present day, with clear ink inscriptions on the beams. The wooden board beneath the ridge beam in the central bay is inscribed with “The reconstruction was undertaken in the third year of Tianjuan (庚申年), on the twelfth day of the sixth month 甲申月, at the time of Wuchen 戊辰時, with the auspicious Qian divinatory symbols of Yuanhenglizhen” (wei Tianquan sannian suici Gengshen run liuyue Guiyou Shuo shi’er ri Jiashen Wuchen shi chongjian ji Qianyuan Hengli zhengji 維天眷三年歲次庚申閏六月癸酉朔十二日甲申戊辰時重建記乾元亨利貞吉). On the four-rafter-beam of the north second bay, there is an inscription written with a brush: “In the fourth year of Huangtong, on the fourth day of the fifth month” (wei tian Huangtong sinian wuyue siri 維天皇統四年五月四日) ().

These inscriptions range from the third year of the Tianjuan period (1140) to the fourth year of the Huangtong period (1144) of Emperor Xizong in the Jin Dynasty, indicating that the reconstruction of the Mahavira Hall spanned five years. This reflects the arduous task of organizing monks to raise funds from the public for the repair and reconstruction of the temple, which cannot be compared to the scale and efficiency of the Liao Dynasty’s imperial construction and organization of Huayansi.

The unique spatial layout of Huayansi, with parallel axes, merged in 1062 and gradually separated into Upper and Lower Huayansi from the Hongwu 洪武 to Xuande 宣德 periods of the Ming Dynasty, forming two independent temple complexes. This confirms the dual-axis layout of Huayansi, reflecting the historical development trajectory of two temples built successively and then merged. Based on the compilation of the literature and on-site research and the interpretation of the dual-axis layout of Huayansi, this study will further elaborate on the rich historical connotations and artistic tension presented in its worship spaces dedicated to the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Ancestors.

4.2. The Western Pure Land Created by Buddha and Dharma in the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall

What is meant by “the Buddha and the Dharma”? They refer to the Buddha’s treasure and the Dharma’s treasure. Shakyamuni Buddha himself, along with his statues and images, constitute the Buddha’s treasure. The teachings of Buddha represent the Dharma treasure. Buddha embodies Dharma as its essence, and Dharma relies on Buddha; thus, Buddha and Dharma are inseparable. Constructed by the Liao Dynasty royal family to enshrine Shakyamuni Buddha and the Liao Canon, the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall presents a unique and innovative form in the material spatial manifestation of Buddha and Dharma. This is evident from its architectural design to the arrangement of sculptures. By creating an imagined Western Pure Land through physical spatial construction, the hall establishes a new worship space that highlights the sacredness of Buddha and Dharma through masterful artistic techniques.

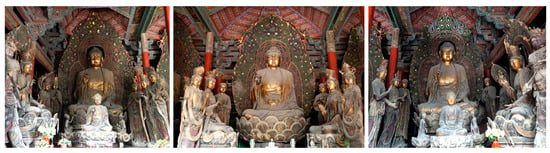

Within the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall, 34 statues are currently preserved, of which 29 are colorfully decorated clay sculptures dating back to the seventh year of the Zhongxi era of the Liao Dynasty (1038). The statues of the Threefold Buddha (or the Three Bodies of Buddha) on the Sumeru pedestal are depicted in the posture of teaching, sitting in the lotus position with their right hand raised in front of the chest in a teaching mudra, and their left hand either resting flat or hanging down by the knee (Figure 14). The disciples Ananda and Kasyapa, along with fourteen attendant bodhisattvas, form three “U”-shaped groups of statues with the main Buddha. These groups are relatively independent yet interconnected, taking both vertical and horizontal perspectives into account to create a dynamic spatial layout (Figure 15). The arrangement includes the three tall main Buddha statues and four medium-sized seated bodhisattvas, as well as standing bodhisattvas, Ananda, Kasyapa, and smaller-sized offering child 供養童子 statues, arranged orderly without obstructing each other. This ensures a diverse and complete composition of the worship space from various angles. Additionally, the hall is home to the Liao Canon, which encompasses eighty-four thousand of the Buddha’s teachings. This serves as the Dharma treasure, establishing an imagined space where the Buddha treasure and the Dharma treasure mutually reinforce each other for the propagation and protection of the Dharma. The faith in the Buddha and the Dharma thus serves as a spiritual support, stabilizing the western frontier of the Liao kingdom.

Figure 14.

Three “U”-shaped groups of painted clay sculptures on the Buddha Altar in the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall (photos by the author).

Figure 15.

Dynamic and lively spatial layout of painted clay sculptures on the Buddha Altar in the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall (photo by the author).

The sutra cabinets in the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall, which house the Liao Canon, are known as the “Bizang and Tiangong Louge” (). Excluding the three bays with doors at the eastern entrance, the tall sutra cabinets are continuously arranged along the walls, encircling the central rectangular Sumeru throne Buddha Altar in the hall, thereby forming a complete interior loop space (Figure 16). The 5.5 m high sutra cabinets create a magnificent and exquisite celestial palace pavilion architecture, allowing worshippers to kneel before the three Buddha statues and then circumambulate the altar, surrounded by the continuous space storing the Liao Canon. This immersion in the solemn and grand world of the Buddha realm completes the ritual of worship within the realm where the treasures of Buddha and Dharma are harmoniously integrated.

Figure 16.

The majestic sutra cabinets enclosing the Buddha Altar, forming a loop worship space in the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall (drawing by the author’s research team).

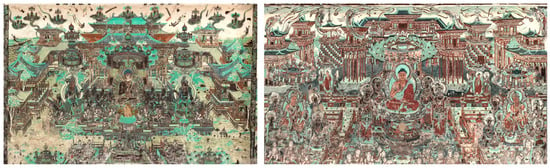

The group of statues featuring the three main Buddhas and attendant Bodhisattvas is situated on the Buddha Altar in the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall, with the sutra cabinets mimicking palace-style celestial palace pavilion architecture as a backdrop. The overall spatial arrangement aims to depict the grand scene of Buddha preaching and expounding the Dharma in the Western Pure Land, offering worshippers a new, immersive Buddhist contemplative space. The murals illustrating the transformation scenes from the Infinite Life Sutra on the eastern wall of Cave 148 in Dunhuang, the northern wall of Cave 172, the northern wall of Cave 217, and the southern wall of Cave 25 in Yulin depict the Buddha preaching in the Pure Land (Figure 17). In these scenes, Manjushri, Samantabhadra, Avalokiteshvara, and Mahasthamaprapta Bodhisattvas are seated on either side of the Buddha while attendant Bodhisattvas joyfully listen to the Buddha’s teachings. Palaces, pavilions, gates, bridges, and rainbow bridges frame the scene from behind and on both sides while flying Apsaras musicians and auspicious clouds encircle the celestial pavilions. These murals vividly and perfectly recreate the splendid scenes of the Western Pure Land in Paradise, conveyed in a two-dimensional imaginary space. The scale proportions of the Buddha and the Bodhisattvas, their U-shaped arrangement, as well as the spatial form constructed by the sutra cabinets’ architectural style and decoration of the celestial pavilions are all faithfully reproduced in the real three-dimensional physical space of the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall. This enriches the sacredness of the Pure Land space created by the hall and enhances the power and grandeur bestowed by the Buddha and the Dharma, thereby significantly strengthening the force of Buddhist faith () (Figure 18).

Figure 17.

The transformation scenes from the Infinite Life Sutra on the northern wall of Cave 172 (left) and Cave 217 (right) in Dunhuang ().

Figure 18.

The Buddha and the Dharma worship space in the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall, presenting the Western Pure Land depicted in Dunhuang Mural Paintings (drawing by the author’s research team).

4.3. Ancestral Protection within the Yurong Worship Space at Huayansi

The Zuozhuan 《左傳》 states, ”The major affairs of the country lie in sacrificial rituals and warfare. Sacrificial ceremonies are significant rituals for interacting with the gods” (guo zhi dashi, zai siyurong, si you zhifan, rong you shoushen, shen zhi dajie ye 國之大事,在祀與戎,祀有執膰,戎有受脤,神之大節也) (). The Liao Dynasty was deeply influenced by Han culture and governed through a combination of rituals and laws. Toqto’a wrote in the Jin Liaoshi Biao 《進遼史表》 that the Liao Dynasty “established the foundation of the state through warfare, governed effectively through rituals and laws, respected heaven and honored ancestors, and performed sacrificial rituals for all activities” (zaobang benxi yu gange, zhizhi nengzi yu fufu, jintian zhunzhu, er churu biji 造邦本席於干戈,致治能資於黼黻,敬天尊祖,而出入必祭) (). The reverence for gods and ancestral worship were both important state ceremonies of the Liao Dynasty, where the divine spirits of heaven and earth and the imperial ancestors were crucial deities protecting the country and its people. The Liao Dynasty placed great importance on ancestor worship, developing a system of national ancestral shrines and ritual ceremonies with distinctive Khitan characteristics. Through ancestor worship activities, they served both the functions of seeking blessings and promoting moral education, ultimately serving the imperial rule.

The Liao Dynasty’s ancestral shrines were classified based on their locations, including capital shrines, provincial shrines, mausoleum shrines, and Mount Muye shrines, as well as “mobile shrines” established with the imperial entourage camp. According to their types, there were imperial ancestral temples, mausoleum temples, and shrines dedicated to individual emperors. As recorded in the “Gaomiao Ceremony” (Gaomiao Yi 告廟儀) and “Yemiao Ceremony” (Yemiao Yi 謁廟儀) in the Liaoshi (), the ancestral shrines of the Liao Dynasty did not enshrine the spirit tablets of ancestors but rather imperial portraits and statues of successive emperors, unlike any other dynasty. Even in the ancestral shrine of the Khitan imperial clan in Mount Muye, they enshrined “painted sculptures of two saints and their eight divine children” (huisu ersheng bing bazi xiang 繪塑二聖並八子神像) (), not the spirit tablets. Therefore, the ancestral shrines of the Liao Dynasty can be regarded as “Yurong Hall” (Yurong Dian 禦容殿) enshrining imperial portraits and statues, but the places where these halls were set up were not necessarily temples. There were more Yurong Halls in terms of quantity and form, which could be worshipped in noble residences and imperial temples. Only two temples for enshrining imperial portraits and statues are recorded in the Liaoshi: “One built by Liao Taizu Abaoji in the Tianzan period (922–926) in the Supreme Capital, where he enshrined the imperial portrait of his father, Emperor Dezu Xuanjian” (you yu neicheng dongnanyu jian Tianxiongsi, fengan liekao xuanjian huangdi yixiang 又於內城東南隅建天雄寺,奉安烈考宣簡皇帝遺像) (). The other was “The Yurong Hall built during the expansion of the Huayansi in the Western Capital in the eighth year of the Qingning period (1062), where stone and bronze statues of successive emperors of the Liao Dynasty were enshrined there” (Qingning banian jian Huayansi, fengan zhudi shixiang, tongxiang 清寧八年建華嚴寺,奉安諸帝石像、銅像) ().

The Liao Dynasty’s five capitals4, except for the Western Capital, all had ancestral shrines. The establishment of the imperial ancestral worship space in the Huayansi in 1062 was closely related to the absence of ancestral sacrificial sites following the upgrading of Yunzhou to the Western Capital. In 1044, Emperor Xingzong suffered a disastrous defeat when leading his army to invade Western Xia, riding a horse and fleeing back to Yunzhou alone. He was forced to accept the proposal of surrendering to the Liao Dynasty made by Li Yuanhao, the king of Western Xia, before the battle, temporarily restoring peace. This defeat prompted Emperor Xingzong to resolve to pacify Western Xia, upgrade Yunzhou to the Western Capital, enhance the city’s military infrastructure and ceremonial space, fortify the frontier town, and prepare for another expedition. According to the Liaoshi “Liyizhi. Junyi” 《遼史·禮儀制·軍儀》, the first item, the “Imperial Expedition Ceremony”, stipulates “Before setting out on a campaign, the emperor must first announce it to the ancestral shrines. The emperor dons armor and worships at the ancestral shrines of the former emperors before reviewing the troops” (). Setting up a place for ancestral worship in the Western Capital became an important necessity, facilitating the holding of the Gaomiao Ceremony, a state ritual, before the emperor’s expedition. However, with Li Yuanhao’s assassination in 1048, the Liao Dynasty launched several small-scale attacks on Western Xia in the following years. In 1053, Western Xia formally sought peace with the Liao Dynasty, and in 1055, Emperor Xingzong, aged 40, died suddenly in his traveling palace (). This series of historical events likely contributed to the delay in building ancestral shrines in the Western Capital. It was not until the eighth year of the Qingning period of Emperor Daozong that, during the expansion of the Huayansi, a grand Yurong Hall was specifically established in the temple to enshrine statues of successive emperors and empresses, finally constructing an ancestral blessing and protective space in the frontier of the Western Capital.

Sixty years after the expansion of Huayansi, the temple experienced military turmoil during the chaotic Baoda period at the end of the Liao Dynasty, resulting in the destruction of all significant buildings on the northern axis. The Yurong Hall within the temple ceased to exist with the collapse of the Liao Dynasty, and its location and spatial form became unknown. The Jinshi 《金史》 mentions the enshrinement of statues of emperors and empresses in Huayansi in two places. One instance is recorded in the Jinshi “Benji”: “On Wushen day (in the sixth year of the Dading period of Emperor Sizong, 1166 AD) of the fifth month, Emperor Shizong visited Huayansi to view the bronze statues of the former emperors of the Liao Dynasty” (wuyue Wushen, xing Huayansi, guan guliao zhudi tongxiang 五月戊申,幸華嚴寺,觀故遼諸帝銅像) (). The second instance is mentioned in the Jinshi “Dilizhi”: ”There are statues of the emperors and empresses of the Liao Dynasty in Huayansi” (you Liao dihou xiang zai Huayansi有遼帝後像在華嚴寺) (). Until the Yuan Dynasty, these imperial statues were still preserved in Huayansi: “The bronze statues of the emperors and empresses of the Liao Dynasty that were in the Western Capital still exist today, and there is no record of any prohibition” ().

During the Qing Guangxu period, the Shanxi Tongzhi 山西通志 provided specific descriptions of these imperial portraits: “Huayansi of the Liao Dynasty was located inside the west gate of Datong Prefecture大同府. Below the Northern Pavilion of the temple, there were several stone and bronze statues, traditionally believed to be statues of the emperors and empresses of the Liao Dynasty... There were five stone statues, three male and two female; and six bronze statues, four male and two female. One bronze figure, depicting the appearance of an emperor wearing ceremonial attire and a ceremonial crown, sitting in a relaxed pose, while the others wear headgear, ordinary attire, and sit upright” (Liao Huyansi zai Datong Fuyu ximen nei, si zhongbeigei xia tongshixiang shuzun, xiangchuan Liao dihou xiang...fan shixiang wu, nansan nv’er, tongxiang liu, nansi nv’er, neiyi tongren, gunmian diwang zhixiang, cuizu erzuo yu jie jinze changfu weizuo 遼華嚴寺在大同府域西門內,寺中北閣下銅石像數尊,相傳遼帝後像……凡石像五,男三女二;銅像六,男四女二。內一銅人,袞冕帝王之象,垂足而坐,餘皆巾幘常服危坐 (). Based on the above information and in conjunction with the details of the relevant imperial statue worship ceremonies recorded in Liaoshi “Lizhi Yi. Jiyi” 《遼史》禮志一·吉儀, including “Caice Ceremony” (Caice Yi 柴冊儀), “Gaomiao Ceremony”, “Yemiao Ceremony” (), and Liaoshi “Lizhi Liu. Shuishizayi” 《遼史》禮志六·歲時雜儀, which includes “Rebirth Ceremony” (Zaisheng Li 再生禮) (), brief speculation can be made regarding the rituals and spatial form of the Yurong Hall in Huayansi.

First, the specifications and ceremonial procedures of the “Gaomiao Ceremony” and the “Yemiao Ceremony” are different. “Gaomiao Ceremony” and “Yemiao Ceremony” are both referred to as paying respect to ancestors. “Gaomiao Ceremony” is performed before a military campaign, while “Yemiao Ceremony” is performed when visiting various capitals. Although the Yurong Hall in Huayansi is not an ancestral shrine, if the emperor were to perform ancestral worship before a military campaign, a high-standard ceremony similar to the “Gaomiao Ceremony” may be conducted here.

Second, according to the description in the Shanxi Tongzhi during the Qing Guangxu period, the Yurong Hall in Huayansi housed eleven imperial statues made of stone and bronze. Among these, there were seven male figures corresponding precisely to the seven emperors before Emperor Daozong. This arrangement of imperial statues, encompassing all the emperors of the Liao Dynasty within a single hall for worship, was a high-level ceremonial scene not seen in any ancestral or temple hall in the Liao Dynasty. However, only statues of four empresses remain, indicating the possible loss or damage of the other three. While the specific allocation of space for each emperor’s life-size statues within the hall remains unknown, according to the “Zhaomu System” (Zhaomu Zhizhi 昭穆之制)5 of the imperial ancestral shrine rites, it is conceivable that seven distinct spaces were designated within the Yurong Hall, each dedicated to a single emperor, resembling individual ancestral shrines. The construction of such a grand “Yurong Hall of the Seven Ancestors” in the Western Capital reflects Emperor Daozong’s fervent aspirations for the gathering of ancestral spirits to safeguard peace and stability on the western border.

Third, the worship ceremony in the Yurong Hall follows a clear spatial sequence both indoors and outdoors, unfolding along a series of architectural spaces that combine indoor and outdoor elements, including the “upper hall”, exposed terraces, red terraces, and balustrades. During the worship process in the Yurong Hall, which involves multiple cycles of bowing, kneeling, and repositioning, there is a series of spatial arrangements for standing, bowing, kneeling, offering incense, and presenting offerings, following a prescribed ritual protocol. After completing the designated worship procedures, the ceremonial official “leads the group” (Yingban 引班) to usher the worshippers into the “upper hall” (Shangdia 上殿) in batches, proceeding with the offering of Yurong wine three times, then guiding their departure, marking the conclusion of the ritual (). Here, the “upper hall” refers to a space distinct from the area designated for the worship of imperial statues, potentially located within the same roof structure of the Yurong Hall but in a different spatial sequence. Alternatively, it could be an independent hall situated along the axis behind the Yurong Hall. The term “upper” expresses the spatial relationship of front and back.

Fourth, participation in the Yurong worship ceremony involves a large number of people, including the emperor, empress, courtiers, priests, officiating officials, and musicians, necessitating a spacious indoor area within the Yurong Hall to accommodate the gathering. Additionally, the hall is equipped with an outdoor terrace to facilitate the frequent transitions between indoor and outdoor spaces during the ritual procession. This terrace also serves as ample space for the sacrificial music ensemble to perform ().

Fifth, “The Emperor descends from the carriage, leading the officials from the southern and northern ministries to enter the temple, forming two lines on the left and right sides. Upon reaching the cinnabar courtyard of the temple, they merge into a single line, and the Emperor ascends the sacrificial terrace of the temple” (huangdi jiangche, fengyin nanbei chenliao zuoyou ru, zhi Danchi ruwei, heban, huangdi sheng lutai ruwei皇帝降車, 分引南北臣僚左右入, 至丹墀褥位, 合班, 皇帝升露臺褥位) (). The spatial configuration reflected by these actions indicates that religious buildings, ancestral shrines, and imperial halls in the Liao Dynasty were often built on elevated platforms. Their architectural style should be similar to the grand elevated platforms found in extant Liao-era structures such as the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall and the Mahavira Hall of the Huayansi. In the stele corridor located on the northern axis of the Huayansi, there is an inscription from the fifty-ninth year of the Qianlong period in the Qing Dynasty, which records the following: “The Huayansi in Yunzhong has a long history, and there have been repairs over the generations. However, due to the passage of time, it has unavoidably become dilapidated. Additionally, the original site of the Heavenly Kings Hall was quite elevated, and the mountain gate is steep and inaccessible” (Yunzhong Shang Huayansi youlai yijiu, daiyou xiubu, bumian yushi qingsi, qie Tianwang jiushi shenggao, shanmen yi jun er buke ☐雲中上華嚴寺由來已久,代有修補,不免逾時傾圮,且天王舊址甚高,山門亦峻而不可☐) (). The old site of the Heavenly Kings Hall on the high platform might have been the location of the Yurong Hall with a terrace. The Jin Dynasty Stela records “It was restored to its original site, and halls with nine and seven bays were specially built” (nai renqi jiuzhi, er tejian jiujian qijian zhidian 乃仍其舊址,而特建九間、七間之殿) (). The Mahavira Hall of Huayansi, with nine bays and rebuilt during the Jin Dynasty, still exists today. Originally constructed during the eighth year of the Qingning period of the Liao Dynasty (1062), it may have served as the highest-level Yurong Hall for the simultaneous worship of the seven ancestors ().

In 1062, Emperor Daozong issued a decree to establish the Yurong Hall of the Seven Ancestors in the Huayansi. This hall was chosen for expansion on the side of the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall completed in 1038 for housing the Liao Canon. This decision allowed for the integration of blessings from the Buddhas, the Dharma, and the ancestral deities, showcasing their combined protective power. The choice to rely on the original east-west axis layout of the existing architectural complex should have been a significant influencing factor. During the Liao Dynasty, the predominant ethnic group, the Khitan people, worshipped the sun and revered the customs of the East. Historical records abound with such practices: all rituals were conducted facing east, referred to as “Rituals To The East” (Ji Dong 祭東) (). The establishment of the “Sun Worship Ceremony” (Bairi Yi 拜日儀) involved conducting activities to worship the sun towards the east at the beginning and middle of each month. During imperial court assemblies to discuss state affairs, the east was regarded with reverence ().

The emperor’s imperial tent faced eastward, with the east-west direction serving as the horizontal longitude axis and the north-south direction as the vertical latitude axis. This was in the opposite direction to the conventional longitudinal and latitudinal directions, as commonly agreed upon. Hence, the imperial tent was referred to as a “Horizontal Tent” (Hengzhang 橫帳) (). The Yurong Hall, one of the seven ancestral halls established in the Western Capital, was situated atop high platforms, facing west to east, in accordance with the ethnic and cultural beliefs of the Khitan people. Simultaneously, the remaining four capitals among the Five Capitals are situated to the east of the Western Capital, spanning a vast territory. The Yurong Hall of Huayansi faces west to east, positioning the statues of the seven former emperors to face the four capitals. Standing on the western frontier, they watch over and guard the territory of the Liao Dynasty. This arrangement represents the best metaphor for the worship space dedicated to the protection of ancestors.

4.4. The Liao Court’s Political Intent in Buddhist Worship: The Triple Blessings of Buddha, Dharma, and Ancestors in Border Protection

From the founding of the Liao Dynasty by Emperor Taizu in 907 AD and his adoption of the imperial title in 916 AD until its fall to the Jin Dynasty in 1125 AD, a period spanning 219 years, the reverence and belief in Buddhism by the imperial family and the court has remained integral to both the domestic governance and foreign affairs of the Liao Dynasty. The development of its religious beliefs was closely linked to the changing political landscape ().

Although the Liao Dynasty did not establish itself as a Buddhist state, alongside Buddhist beliefs, there existed the indigenous religious practices of the Khitan people such as nature worship, ancestor worship, and Taoist beliefs. However, successive emperors of the dynasty devoutly believed in Buddhism, regarding Avalokitesvara, Shakyamuni Buddha, and various Bodhisattvas as protective deities of the ancestors, the state, and the people. In the Taizu Ji 太祖紀 in the Liaoshi (in office from 907 to 926), it is recorded that “In the fourth year of the Shence period, he visited Buddhist temples and Taoist temples” (Shence sinian……fen ye siguan 神冊四年……分謁寺觀), and “In the fourth year of the Tianzan period, he visited the Anguo Temple and made offerings to the monks” (Tianzan sinian……xing Anguosi, fanseng 天贊四年……幸安國寺,飯僧) (). Subsequent emperors, empresses, crown princes, and important ministers regularly visited and made offerings at temples, venerating the Triple Gems of the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha. Particularly during the period of Emperor Taizong 太宗 (927–47), he visited the Great Compassion Pavilion (Dabei Ge 大悲閣) in Youzhou and brought a statue of the White-robed Avalokitesvara to Mount Muye (Muye Sha 木葉山), a sacred mountain of the Liao Dynasty, where a Bodhisattva hall was erected for worship, honoring Avalokitesvara as the guardian deity of the imperial family and clan. At the same time, the ritual of paying homage to the Bodhisattva hall was added, leading to modifications in the ceremonial procedure of the “Mountain Sacrifice Ceremony“ (Jishan Yi 祭山儀), which served as a state ritual. Subsequently, the sacrificial ritual at Mount Muye began with worship at the Bodhisattva hall, followed by the mountain worship ceremony (). The fact that the Liao court placed the worship of Avalokitesvara before the essential ceremonies honoring ancestors and mountain deities underscores Emperor Taizong’s devoutness to Buddhism and the fervor with which he promoted widespread Buddhist beliefs among the populace.

The periods of Emperors Shengzong, Xingzong, and Daozong were a prosperous era in terms of socioeconomic aspects and a period of military and political prosperity in the Liao Dynasty, also marking the peak of Buddhist reverence. The adoption of Buddhist names as childhood names by the emperors and empresses offers insight into the flourishing Buddhism in the Liao Dynasty: Emperor Shengzong’s childhood name was “Wenshu Nu” 文殊奴 (Manjushri Bodhisattva’s Servant), Empress of Shengzong’s childhood name was known as “Pusa Ge” 菩薩哥 (Bodhisattva Brother, a woman’s intimate address for a man), and the Empress of Daozong’s childhood name was “Avalokitesvara” (Guanyin 觀音) (). During the period of Emperor Shengzong, efforts to compile and collect Buddhist scriptures began, with the woodblock printing of the Liao Canon commencing no later than the twenty-first year of the Tiance period (1003). This monumental project, spanning the periods of Emperor Shengzong, Xingzong, and Daozong, was spearheaded by the emperor and involved numerous eminent monks from various regions, culminating in its completion under full support from the court. Emperor Xingzong continued the dedication of Shengzong to Buddhism, often engaging in Buddhist debates in the palace and making offerings to monks in temples (). In the ninth month of 1038, the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall was completed in the strategic border territory of Datong in Yunzhou, housing the Liao Canon compiled from the period of Emperor Shengzong to Xingzong. Yunzhou, thus, became a holy site of Buddhism in the Liao Dynasty. Utilizing the divine power of the Buddha and the Dharma to safeguard the western border, particularly to deter the ambitious Western Xia led by Li Yuanhao, who proclaimed himself emperor in 1038, was imperative. In the same year, in the twelfth month of 1038, in the records of the Liaoshi, Emperor Xingzong ”visited a Buddhist temple to receive precepts” (xing fosi, shoujie 幸佛寺,受戒) (). This likely refers to his visit to the newly constructed Bhagavata Scriptures Hall, where the Liao Canon was housed and where he received the precepts. This act by Emperor Xingzong further propelled the populace towards the path of Buddhism.

Deeply influenced by Xingzong, Emperor Daozong was also a devout Buddhist who constructed numerous temples and pagodas, with monks and nuns numbering as high as 360,000 across various regions (). Emperor Daozong possessed profound scholarly knowledge in Chinese studies and had a thorough understanding of Buddhist teachings. Under his leadership, the second expanded version of the Liao Canon was completed through woodblock printing. The Liaoshi records that in the eighth year of the Qingning period (1062), Emperor Daozong decreed the construction of Huayansi. In the fourth year of the Xianyong period (1068), he issued the Yuzhi Huayanjing Zan 禦制華嚴經贊. In the eighth year of the Xianyong period (1072), he presented the imperial inscription of Huayan Wusong 華嚴經五頌 to his ministers (). These historical facts illustrate Emperor Daozong’s adherence to the Huayan sect, his study of the Huayan Sutra, his promotion of the woodblock printing of the Liao Canon, and his vigorous efforts to propagate Buddhism.

While fostering friendly relations with the Song Dynasty since the signing of the Treaty of Chanyuan, the Liao Dynasty also sought to rival the state’s strength of the Song Dynasty. Learning that neighboring countries Goryeo and Western Xia were requesting the Tripitaka from the Song Dynasty, Emperor Daozong, shortly after the high development of Buddhism and the completion of the Liao Canon woodblock printing, more precisely in the twelfth month of the eighth year of Xianyong period (1072), granted one set of the Liao Canon to the King of Goryeo (). Historical records depict the King of Goryeo personally receiving the gift with great pomp and ceremony. This event reflects the political intent of the Liao court’s reverence for Buddhism, utilizing it to advance peaceful diplomacy and showcase the value of the empire’s power on the international stage.

After the development during the periods of Emperor Shengzong, Xingzong, and Daozong, Buddhism in the Liao Dynasty gradually entered its heyday in the 10th and 11th centuries. The court, utilizing the divine protection of the Buddha and the Dharma, as well as the educational function of the Buddhist faith, employed it as a dual means in both domestic governance and foreign diplomacy. The decree by Daozong to build the Huayansi and the construction of the grand Seven Ancestors’ Hall in the Western Capital were emblematic products of the Liao’s political and diplomatic history in the 10th–11th centuries. The sacred spatial composition of Huayansi included Buddhist statues along the two axes in 1038 and 1062, the repository of scriptures from the Khitan and Tibetan cultures, and the ancestral worship space for the seven generations of Liao emperors. These elements combined to form a triple blessing of the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Ancestors, serving as the protective stronghold of the western capital of Datong Prefecture in the Liao Dynasty, collectively bearing the political expectations bestowed by the Liao court.

5. Conclusions

The article clarifies the context of the preservation and continuation of the wooden structure hall architecture of Huayansi during the Liao and Jin dynasties. It explains that the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall was constructed in advance during the Xingzong period specifically to house the Liao Canon. It also discusses the spiritual realm of the Western Pure Land created by the holistic artistic space of the Buddha and the Dharma presented within the hall. Additionally, it examines how the construction of the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall, with its dual-axis worship space blessed by both the Buddha and the Dharma, served as a powerful realm through which the Liao court expressed its hopes to deter neighboring countries and ensure the safety of the western frontier. This contrasts with the functions of Huayansi, which was built 24 years later during the Daozong period, and its existing Mahavira Hall, a significant Buddhist temple of the Huayan School. The article reassesses and elevates the historical significance of the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall.

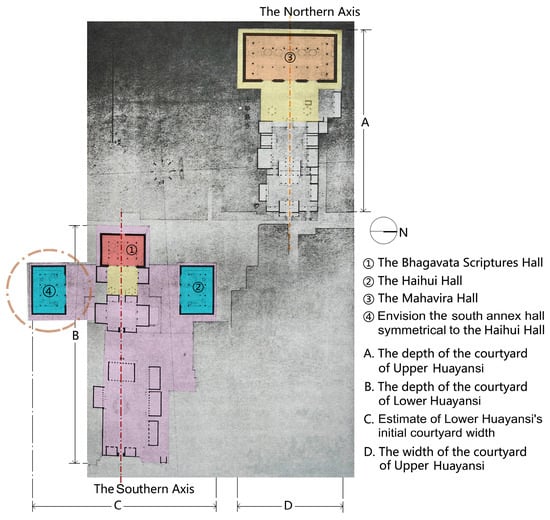

Simultaneously, the article systematically reviews and verifies the Liao History and the related literature to provide a comprehensive understanding, further proposing a new connotation and historical significance of Huayansi’s east-west-oriented dual-axis. The Bhagavata Scriptures Hall on the south axis was constructed in the seventh year of the Liao Zhongxi period (1038) and housed the scriptures of the Liao Canon, copied and printed during the reigns of Emperors Shengzong and Xingzong. In 1933, Liang Sicheng and Liu Dunzhen demonstrated in the “Datong Gujianzhu Diaocha Baogao” that the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall and the Haihui Hall were built in the same era, as they are the preserved original structures from the Liao Dynasty (). Although the Haihui Hall was destroyed in the 1950s, estimates based on the dimensions of the existing site suggest that, according to the symmetrical relationship between the Haihui Hall and the south axis, the mirrored layout of the southern auxiliary hall of the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall forms a total courtyard width (Figure 19), indicating that its original scale was far greater than the courtyard scale presented by the current south axis building group (Figure 1).

Figure 19.

General plan of the Upper and Lower Huayansi in 1933: parallel dual-axis temple spaces with an initial courtyard width proposal for the Lower Huayansi (drawing created by the author’s research team, reference map: ()).

The north axis is the architectural complex of Huayansi, bestowed the name of the Daozong emperor and constructed in the eighth year of the Liao Qingning period (1062), marking the beginning of Huayansi in Yunzhou. The north axis complex not only includes the grand Mahavira Hall dedicated to the worship of the Buddha in the Huayan world but also features large royal ancestral halls such as the Yuyong Hall, which houses statues of the Seven Ancestors. This fills the gap for an important ceremonial space necessary for conducting national ancestral worship rites, which became essential after Yunzhou was elevated to the status of the Western Capital in 1044.

The political and cultural core elements hidden within the dual-axis worship space of Huayansi are closely related to three significant years in Liao history: 1038, 1044, and 1062. The major historical events associated with these years include the completion of the entire set of Liao Canon through the engraving efforts during the reigns of Emperors Shengzong, Xingzong, and Daozong; the complex political diplomacy and military conflicts between the Liao state and the Bohai, Xi, Goryeo, Western Xia, and Song dynasties, which led to territorial changes in the Liao period and the successive establishment of the Five Capitals; the continuation of religious worship and sacrificial systems in the Liao state, as well as the urban construction following Yunzhou’s elevation to the status of the Western Capital, among others. The rich connotation of the dual-axis worship space, oriented from west to east, not only reflects the grand historical background of internal governance and foreign policy in the Liao Dynasty during the 10th and 11th centuries but also carries the diverse religious beliefs and cultural characteristics of the Khitan people.

The architectural complex of Huayansi, oriented along an east-west dual-axis line, was formed by merging two groups of temples built in different periods and serving distinct functions, with a time difference of at least 24 years. The dual-axis design, extending from the spatial layout to architectural form, has been endowed with innovative regulations, collectively constructing a multidimensional worship space at the Great Huayansi of the Liao Dynasty, which is imbued with the triple empowerment and protection of the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Ancestors. This space intersects and condenses the Liao state’s internal governance philosophy of ruling through Buddhism and honoring ancestors with its military and diplomatic strategies aimed at intimidating enemy nations and safeguarding the state, all materialized within the historical context and spatial dimensions of the parallel dual-axis architectural complex of the Huayansi.

Funding

This research was funded by [Shanxi Provincial Bureau of Cultural Relics 2023 Cultural Relics Technology Project] grant number [Tong Wenwu Zi (2022) No. 95, D.76-0113-23-031], and [2023 National Social Science Foundation Art General Project] grant number [23BG141].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | In the academic community, various English translations for 華嚴寺 have been used, including Huayan Temple, Huayan Monastery, Huayansi, and Huayan Si. This article, drawing upon the work of Nancy Shatzman Steinhardt in her book Liao Architecture, has chosen to employ the term ‘Huayansi’ for its expression. |

| 2 | The images, including Figures 1, 3, 6, 7, 10, 11, 16, 18 and 19, were created by the author’s research team. The members of the research team who participated in the surveying and drawing of the Bhagavata Scriptures Hall are: Huizhong Bin (宾慧中), Sijia Liu (刘思佳), Yu Mei (梅宇), Chaoying Pu (濮超颖), Nan Nie (聂楠), Yu Li (李钰), Min Din (丁敏), Jiahao Huang (黄家浩), Yunfan Chen (程云帆), Xinran Shi (史馨然), Sijie Chen (陈思洁), and Xinjia Huang (黄心佳). |

| 3 | The two precise historical dates mentioned here are derived from inscriptions found beneath the beams of the main hall of Huayansi. For further details, please refer to the quotations of these inscriptions provided in Section 4.1 of the “Dual-Axis Worship Space of Huayansi and Its Liao to Jin Dynasty Remnants”. |

| 4 | According to records in the Liaoshi, the Capital Shrines were as follows: The Supreme Capital (Shangjing 上京) featured the ancestral shrine of Taizu (Taizumiao 太祖廟), the imperial ancestral temple (Taimiao 太廟), and the shrine of Emperor Xuanjian (Xuanjian Huangdi Miao 宣簡皇帝廟); The Eastern Capital (Dongjing 東京) housed the ancestral shrine of Taizu, the shrine of Emperor Rangguo (Rangguo Huangdi Miao 讓國皇帝廟), and the shrine of Emperor Shizong (Shizong Miao 世宗廟); The Southern Capital (Nanjing 南京) contained the ancestral shrine of Taizu, the shrine of Emperor Taizong (Taizong Miao 太宗廟), the shrine of Emperor Jingzong (Jingzong Miao 景宗廟), and the Temple of Emperor Qishou Khan (Qishou Khan Miao 奇首可汗廟); The Central Capital (Zhongjing 中京) included the ancestral shrine of Taizu, the imperial ancestral temple, and the shrine of Emperor Jingzong. |

| 5 | The Zhaomu System refers to one of the systems of ancestral temples. According to the temple system regulations, the emperor establishes seven temples, princes establish five temples, high-ranking officials establish three temples, gentlemen establish one temple, and common people are not entitled to establish temples, thereby distinguishing between different ranks and statuses. |

References

Primary Sources