Study on the Religious and Philosophical Thoughts of Xizi Pagodas in Hunan Province of China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

- The conscious exploration and initial construction based on the custom and belief of “Cherishing Papers with Characters” has pioneered the study of Xizi Pagodas in modern China. The custom of Cherishing Papers with Characters can be understood as a kind of “information worship”, a characteristic of traditional Chinese culture, in which people view information as a sacred symbol, and when this worship is put into action, the “Xizi” Rituals of burning Papers with Characters and returning them to nature are formed. Also, there are corresponding Xizi Furnaces (惜字炉), Xizi Pagodas and other materialized landscapes (Sang 1996). The earliest research on Xizi Pagodas in China was conducted in 2008 in “the Xizi Pagoda in the Ming and Qing Dynasties—Architectural Relics of “Xizi” Culture (明清惜字塔——惜字文化的建筑遗存)”, which first mentioned Xizi Pagodas and the “Xizi” Culture during this period. The study took Sichuan Xizi Pagodas as the research object and believed that the basic function of Xizi Pagodas is to incinerate Papers with Characters (Song 2008). Xizi Pagodas are commonly found by the water’s edge as the collected ash will later be poured into the sea. In addition, they are also commonly found in academies, ancestral halls, temples and other places where a large amount of Papers with Characters is produced. Sometimes, they were also built as a symbol of prosperity of local cultural beliefs at the entrance of villages (Tan and Luo 2018).

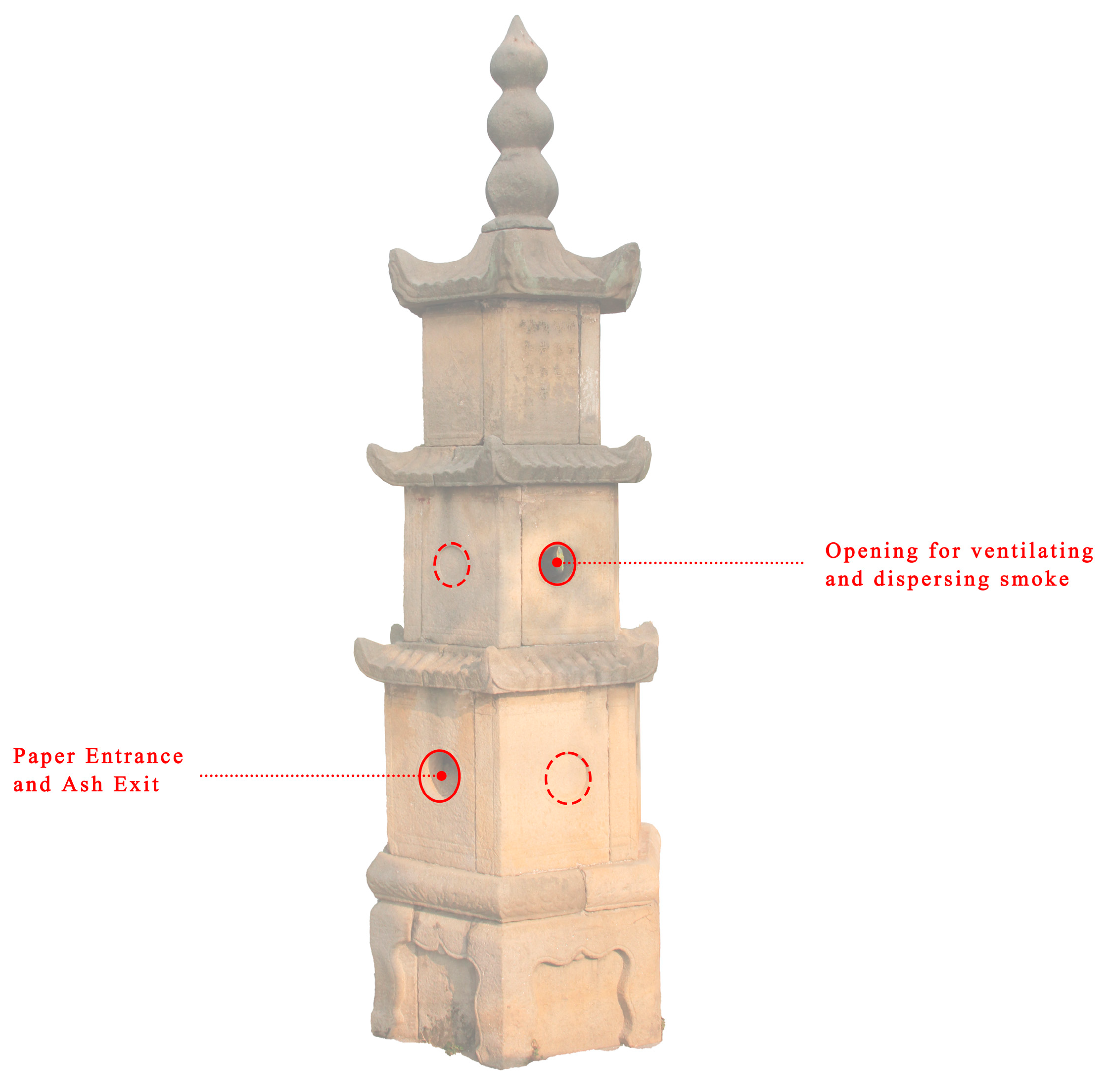

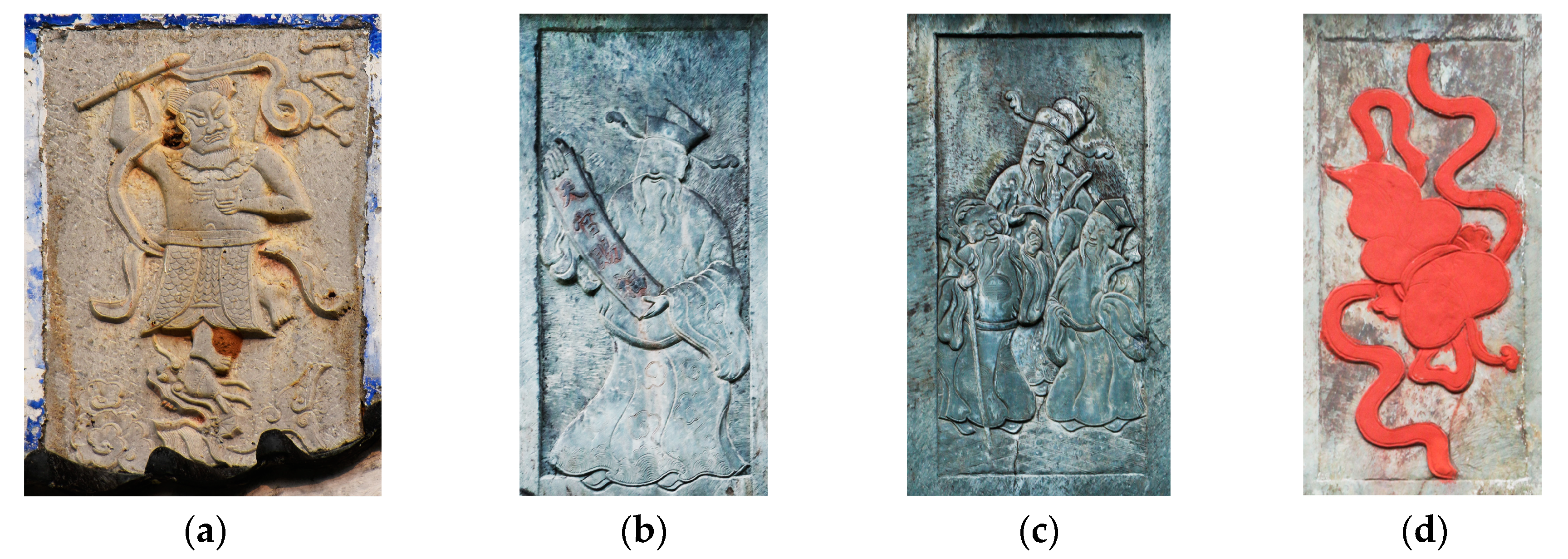

- Research on Xizi Pagodas has gradually developed with a focus on the artistic form of Xizi Pagodas and the spiritual belief behind them. The artistic form of Xizi Pagodas include geometric relationships, primary and subordinate, contrasts and differences, rhythm and rhyme, proportion and scale, balance and stability and other formal beauty principles (Zhou and Zhang 2011). Xizi Pagodas are embodiments of characters and culture. People hold the “Xizi” Ritual under Xizi Pagodas, praying for good luck in the Imperial Examination, which has gradually made Xizi Pagodas the material embodiments of prayer for blessings (H. Zhu 2013). Under the combined influence of various factors such as Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism, the thought of “Cherishing Papers with Characters” gradually matured, ultimately leading to the emergence of Xizi Pagodas. The folk belief that characters have spirituality is a key factor in promoting the development of Xizi Pagodas (Chen and Liu 2014). Due to the functional requirement of burning Papers with Characters, the interior of Xizi Pagodas are designed as a cylindrical space. Scholars have conducted a certain amount of analysis and excavations of the unique functions and morphological features of Xizi Pagodas in various regions of China, with most of the research areas focusing on the Sichuan and Chongqing regions, and some of the studies also involve Xizi Pagodas in Hunan, Hubei, Guangdong, Taiwan, and other places. Since Xizi Pagodas in one region tend to have similar structural features, Xizi Pagodas in other regions may have significant differences. For example, the 70 existing Xizi Pagodas in the Chongqing area are mostly stone pagodas with hollow interiors, and their basic structures and external decorations are no different from those of other pagoda-type buildings, and most of the decorations are engraved with couplets of characters and auspicious motifs (Shu and Luo 2023). In Yanting County, Sichuan Province, there are a large number of stone masonry Xizi Pagodas, which have a Baogu Stone (抱鼓石) on each floor, known as the “Yanting Classic Xizi Pagoda”, which are extremely rare in other areas (Li et al. 2022). The discovery of a number of Xizi Furnaces and Xizi Pagodas in Lianzhou City, Qingyuan, Guangdong Province, reflects the importance that Lianzhou City has historically attached to culture and education (M. Huang 2011). Shunsheng Shi (施順生) excavated more than 110 Xizi Pagodas in the Taiwan area, with a total of 33 different titles, and analyzed the morphological characteristics of the five remains of Xizi Pagodas: pavilions, furnaces, buildings, pagodas and stands (S. Shi 2007). In Xintian County, Hunan Province, the decorative pattern of the Xizi Pagodas unites the specialized auspicious forms of cultural and educational architecture (Tan et al. 2023). At the same time, their aesthetic appearance is also influenced by the spirit of Hunan Culture, such as cherishing literature and ceremonies, and having candor and optimism. It has become a unique ethnic art form in Chinese culture with a unique role in enlightenment and education (He et al. 2023).

- China is now paying increasing attention to the protection of ancient buildings, with the promulgation of a series of laws such as the “Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Cultural Relics (中华人民共和国文物保护法)” and the “Regulations for the Implementation of the Law on the Protection of Cultural Relics (文物保护法实施条例)”. Using the Third Cultural Heritage Census (第三次文物普查) carried out from 2007 to 2011, many Xizi Pagodas were discovered. At this time, people began to attach importance to the material cultural heritage of Xizi Pagodas. In the restoration of the Xizi Pagoda in Chating Town, Wangcheng County, Hunan Province, Professor Liu Su (柳肃) combined the expertise of experts from many disciplines, including botany, materials science, chemistry and chemical engineering, to preserve the unique landscape of the combination of the Xizi Pagoda and trees (Liu 2008). Some scholars gradually began to photograph Xizi Pagodas in the field, measure the data on the spot, build 3D digital models, and carry out digital art restoration based on the proportionality of the pagodas (W. Huang 2022). Other scholars used finite element numerical simulation analysis and concluded that Xizi Pagodas have good stability, and the reason is related to the plan form of Xizi Pagodas and their architectural components (He et al. 2023).

3. Materials and Methods

- Hunan Province has had a flourishing literary style since ancient times. During the Ming and Qing Dynasties, there were 429 palace graduates (进士) from Hunan Province, accounting for 56.2 percent of the total number of palace graduates (进士) in the country (Nie and Wan 2005). Under the influence of Zhou Dunyi (周敦颐) (1017–1073), the pioneer of Sung Ming Neo-Confucianism5, until the Ming and Qing Dynasties, Hunan became the flourishing place of Confucianism and has developed academic thought with local characteristics. There were many famous Confucian scholars, such as Hu Anguo (胡安国) (1074–1138), Hu Hong (胡宏) (circa 1105–circa 1155), Zhu Xi (朱熹) (1130–1200) and Zhang Shi (张栻) (1133–1180), who taught Confucian classics in Hunan. Against this background, the “Xizi” Culture was widely spread in Hunan, and a large number of Xizi Pagodas were built and relatively well preserved.

- By searching “China National Knowledge Infrastructure” and “Web of Science” literature platform, we can find 28 studies on Xizi Pagodas, but only 4 studies on Xizi Pagodas in Hunan Province. Thus, more studies need to be conducted.

- The research team of authors belongs to the key universities of Hunan Province, China, and has long been carrying out research on Hunan vernacular landscape, with a rich research foundation, close contact with the local government and relevant social groups. Also, conducting the study in Hunan Province is also more convenient considering geographical factors.

4. The Religious Thought of “Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism” of the Xizi Pagodas

4.1. The Emergence of Xizi Pagodas Is Connected to the Development of Confucianism

4.2. Xizi Pagodas Incorporate Buddhist Thoughts and Inherit the Form of Buddhist Pagodas

4.3. The “Xizi” Ritual and Images of Deities on Xizi Pagodas Associated with Taoism

5. The “Xizi” Cultural Inheritance and Xizi Pagodas Protection

6. Conclusions

- The emergence of Xizi Pagodas is connected to the development of Confucianism. The “Xizi” thought had already appeared in the Northern Qi Dynasty; under the influence of the political system of the literati as officials, the “Xizi” trend began to prevail in the Song Dynasty. The improvement of the Imperial Examination System in the Ming and Qing Dynasties brought the “Xizi-belief” to a peak. The Xizi Pagoda’s image, such as “Fish Leaping the Dragon Gate”, and its couplets contain Confucian cultural connotations, all of which are intended to emphasize Confucian ethics and morals and to spread Confucian thought through the “Xizi” Ritual.

- Xizi Pagodas incorporate Buddhist thoughts and inherit the form of Buddhist Pagodas. The thought of “Cherishing Papers with Characters” was in line with the Buddhist thought of cherishing the classics and was further developed as the religion grew and spread. The modeling of Xizi Pagodas originates from Buddhist Pagodas, inheriting the construction method, flat and facade form and decorative features of Buddhist Pagodas, and at the same time, it innovates the entrance and exit form with the function of smoke evacuation.

- The “Xizi” Ritual and images of deities on Xizi Pagodas are associated with Taoism. The “Xizi” Ritual has absorbed the burning rituals of Taoist sacrifices and has strong Chinese Taoist characteristics. The continuous development and refinement of the ritual gave rise to the Xizi Pagoda. Most Xizi Pagodas are usually carved with images of Kuixing, Fu Lu Shou and other deities from Taoist mythology. It is believed that performing the “Xizi” Ritual under the watchful eyes of these deities will eliminate disasters and bring blessings.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | “Jing Xi Zi Zhi (敬惜字纸)” means Cherishing Papers with Characters, which is often abbreviated to “Xi Zi (惜字)” and carved on Xizi Pagodas. The word “Xi (惜)” means to treasure and cherish, while “Zi (字)” means Chinese characters, and “Xizi (惜字)” represents “Cherishing Characters”. |

| 2 | In China, the concept of “Scholarly Culture (书香文化)” first came from a plant called “Ruta graveolens L. (芸草)”, whose scent was said to repel insects. Readers used to put the plant in their books and called the aroma of the plants “the aroma of the book(书香)”. Later, “Scholarly Culture(书香文化)” came to refer to the culture of reading. |

| 3 | “Cangjie Creating Characters (仓颉造字)” is one of the myths and legends of ancient China. Cangjie (仓颉) had collected, organized, standardized and used the characters that had been passed down among the ancestors and played an important role in the creation of Chinese characters, and was honored by later generations as the “Sage of Character Creation”. Cangjie’s action moved the gods of heaven, when the grain fell from the sky like rain, frightening the ghosts and monsters so much that they cried at night. |

| 4 | Wenchang Di (文昌帝君) is a deity revered by Chinese folklore and Taoism as being in charge of the achievements and positions of scholars. |

| 5 | Sung Ming neo-Confucianism is a generic term for the Confucian thought and doctrine of the Song, Yuan, and Ming periods, a neo-Confucianism centered on traditional Confucianism and compatible with the philosophical theories of Buddhism and Taoism. |

| 6 | The “Fish Leaping the Dragon Gate (鱼跃龙门)” is an ancient Chinese folklore. In ancient times, people imagined that after jumping over the Dragon Gate, these carp would change into dragons and ascend to heaven, which was a metaphor for a successful career or a high position. |

| 7 | Stūpa is a form of pagoda originating from India, which is mainly used to enshrine and house the bones (relics), scriptures and dharma objects of the Buddha and holy monks. |

| 8 | Feng Shui (风水) is a theoretical system based on Chinese philosophy of “Qi (气)”, which is used to explain the ideal living environment model of Chinese people, specifically referring to the location of residential bases, graveyards, etc. Chinese people believe that the quality of “Feng Shui” can affect the fortunes of their families. |

| 9 | Phase Wheel (相轮) is the metal ring in the middle part of the pagoda’s Vertical Shaft, which serves as an indication of the pagoda and plays a role in honoring the Buddha. The more layers of the phase wheel, the higher the virtue. |

| 10 | Four Noble Truths (四圣谛): The Four Noble Truths (Sanskrit: Catursatya), is one of the basic teachings of Buddhism. It refers to the Four Noble Truths of suffering, collection, annihilation and the Way. |

| 11 | Reincarnation (六道轮回): The Six Paths of Reincarnation are the paths that naturally lead to different paths according to the karmic consequences of one’s life. The six paths are divided into three good paths and three evil paths. |

| 12 | Eightfold Path (八正道): The Eightfold Path (Sanskrit Aryastangika-marga) is a Buddhist term. It means the eight ways to reach the highest ideal state of Buddhism. |

| 13 | Sumeru, of Indian origin, is a pedestal on which statues of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas are placed. Later, it was used to refer to the decorative base of buildings. |

| 14 | According to Chinese Taoism, the soul is divided into Hun (魂) and Po (魄), with the Hun being the “Yang Qi (阳气)” that makes up a person’s mind and intellect. Po is the coarse, heavy and turbid “Yin Qi (阴气)”, which constitutes the human sensory form. When a person dies, the Hun returns to heaven, and the Po returns to the earth. |

| 15 | The Eight Immortals (八仙) are eight Taoist gods who are popular in Chinese folklore. The magic weapons used by each of the immortals are gourd (Tie Guai Li 铁拐李), palm leaf fan (Han Zhong Li 汉钟离), fish drum (Zhang Guolao 张果老), lotus flower (He Xian Gu 何仙姑), flower basket (Lan Cai He 蓝采和), sword (Lv Dong Bin 吕洞宾), flute (Han Xiang Zi 韩湘子) and jade board (Cao Guo Jiu 曹国舅). |

| 16 | In ancient China, there existed a man named Li Ruyi (李如一), who avidly acquired rare books at any cost and performed ceremonial rituals with burning incense to venerate them. |

| 17 | Fan Qin, the Minister of War in the Ming Dynasty, initiated the construction of a library known as “Tianyi Pavilion” in the eastern part of his residence, which housed an impressive collection of over 70,000 volumes at that time. Tianyi Pavilion, established more than four centuries ago, stands as a pioneering example of Chinese private book collections. |

References

- Chen, Fang, and Xiaodong Liu. 2014. A Brief Discussion on the Character Library Tower—Starting from the Qing Dynasty Character Library Tower in the Collection of Chengdu Wuhou Temple Museum 字库塔小议——从成都武侯祠博物馆馆藏清代字库塔说起. Chinese Culture Forum 中华文化论坛 8: 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Li, and Zilu Yang. 2024. Covering paper and Burning Money: A Study on the Funeral Rituals of the Juehuang Altar in Yongchuan, Chongqing 盖纸与烧钱:重庆永川觉皇宝坛丧葬仪式研究. Religious studies 宗教学研究 1: 225–33. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, Xiaotong. 1997. My Reflections on My Scholarship—One of the Humanistic Values Reconsidered 我对自己学术的反思——人文价值再思考之一. Du Shu 读书 9: 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, Huiling. 2018. From Confucianism to Witchcraft?—Historical Changes in Taiwan’s Academic Schools 由儒入巫?——台湾书院的历史变化. Image Historical Studies 形象史学 2: 136–66. [Google Scholar]

- Guang, Yin. 1932. Notes on the Works of Venerable Yin Guang 印光法师文钞. Shanghai: Buddhist Studies Bookstore 佛学书局. [Google Scholar]

- He, Yiwen, Xuemin Zhang, Xinlei Chen, Dong Fu, Bei Zhang, and Xubin Xie. 2023. Study on the Protection of the Spatial Structure and Artistic Value of the Architectural Heritage Xizi Pagoda in Hunan Province of China. Sustainability 15: 8352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Guoqun. 2021. The Historical Change and Cultural Connotation of the Xizi Culture 惜字文化的历史流变及内涵. Folk Art 民艺 2: 123–25. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Minqiang. 2011. Words can preserve the past, Xizi pagoda can burn the papers with characters—The Xizi pagoda shows the glorious history and culture of Lianzhou 字内能存千古事 炉中可化万年书——从化字炉管窥连州辉煌的历史文化. Cultural Relics in Southern China 南方文物 4: 181–83. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Wushu. 2022. Technical Approach to the Restoration of Xizi Pagoda in Northern Sichuan in a Digital Way—Case Study of Xizi Pagoda in Wentanqiao 数字化艺术修复川北惜字塔的技术途径——以文滩桥惜字塔为例. Art and Literature for the Masses 大众文艺 524: 38–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ino, Kanori. 1991. Taiwan Culture 台湾文化志. Taibei: Documentation Committee of Taiwan Province of China 台湾省文献委员会. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Xiangdong, Xiaoli Zhu, Shuting Lei, Danli Li, and Jing Xu. 2017. On the Historical and Cultural Value of Konglin Academy and its Restoration 论孔林书院及其修复的历史文化价值. Shaoguan College Journal 韶关学院学报 38: 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki, Michiko. 2015. About Cherishing Papers with Characters—Cherishing Papers with Characters by nakara morishima and bakin takizawa 敬惜字紙について ─森島中良・瀧澤馬琴の敬惜字紙. Eastern Philosophy and Culture 東洋思想文化 2: 154–58. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Na. 2011. Research on the Belief in Awe of ScriptPaper During the Qing Dynasty and Republic of China 清代、民国民间惜字信仰研究. Master’s thesis, Central China Normal University 华中师范大学, Wuhan, China. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yong. 2013. The Inheritance and Change of the Faith Practice of Honouring Paper with characters in Overseas Countries—A Case Study of Chongwenge in Singapore 敬惜字纸信仰习俗在海外的传承与变迁——以新加坡崇文阁为例. Studies in World Religions 世界宗教研究 2: 89–95+194. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yunzhang, Xiangmei Yang, and Fen Wu. 2022. Analysis on the Classic Architectural Form of Ziku Pagodas in Yanting County 盐亭经典式字库塔形制特征研究. Traditional Chinese Architecture and Gardens 古建园林技术 4: 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Qizi. 2001. Charity and Indoctrination 施善与教化. Shijiazhuang: Hebei Education Publishing House 河北教育出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Su. 2008. Practice and Exploration of Comprehensive Conservation of Ancient Architecture and Ancient Environment 古建筑与古环境综合保护的实践与探索. Paper presented at 2008 Academic Symposium of the Architectural Historical Branch of the Architectural Society of China 中国建筑学会建筑史学分会2008年学术研讨会论文集, Kaifeng, China, October 27. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Xun. 1973. Dawn Blossoms Plucked at Dusk 朝花夕拾. Beijing: People’s Literature Publishing House 人民文学出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Xun. 2016. Origins of Characters and Literature 门外文谈. Beijing: Beijing Publishing Group 北京出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Zhewen. 1983. Chinese Pagoda 中国古塔. Beijing: Heritage Publishing House 文物出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Memory of China Project Centre. 2014. National Library of China 国家图书馆中国记忆项目中心. Our Characters 我们的文字. Beijing: Tsinghua University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, Ronghua, and Li Wan. 2005. The General Theory of Hunan Culture 湖湘文化通论. Hunan: Hunan University Press 湖南大学出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Sang, Liangzhi. 1996. The Cult of Information in Ancient China--Shizi Lin, Ziqi Monks and Dunhuang Grottoes 中国古代的信息崇拜——惜字林、拾字僧与敦煌石窟. Journal of Peking University (Philosophy and Social Sciences) 北京大学学报(哲学社会科学版) 3: 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Yatong. 2015. The Interpretation of Types of Chinese Stupas in the Sight of History of Buddhist Thought 佛教思想史视域下的中国佛塔类型研究. Master’s thesis, Shandong University 山东大学, Shandong, China. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Zhuhong. 1942. Zi Zhi Lu 自知录. Shanghai: Guoguang Publishing House 国光印书馆. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Minfeng. 2021. An Examination of the Popular Reverence for Papers with Words in Qing Dynasty Huzhou: With the Reverence for Words Tablet Inscriptions and Local Records as a Major Example 清代湖州民间敬惜字纸传统论考——以《惜字林碑记》及地方志为中心. China Local Records 中国地方志 3: 112–18. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Shunsheng. 2007. A Study on Name of “Respect Words Pavilion” in Taiwan Area 台灣地區敬字亭稱謂之探討. Chinese Culture University Chinese Journal 中國文化大學中文學報 15: 117–68. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Zhenlin. 1907. Xiqing Sanji 西青散记. Shanghai: Shanghai Guangzhi Bookstore 上海广智书局. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, Ying, and Yang Luo. 2023. Word Stock Tower in Chongqing’s Countryside: The Guardianship of Ploughing and Reading Culture 巴渝乡村字库塔:耕读文化的守望. City Geography 城市地理 11: 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Benrong. 2008. Xizi Pagoda in Ming and Qing Dynasties—Xizi Culture in the Architectural Form 明清惜字塔——惜字文化的建筑遗存. Forbid City 紫禁城 165: 176–81. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Dandan, and Ming Luo. 2018. Analysis on the Culture of the Xizi Pagoda Based on the Belief of Cherishing Pape—Taking Changsha and Its Surrounding Areas as an Example 浅析基于”敬惜字纸”信仰的惜字塔建筑文化——以长沙市及其周边地区为例. Chinese & Overseas Architecture 中外建筑 204: 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Dandan, Shidong Shi, and Ming Luo. 2023. A Study on the Architecture Decorative Texture of Script Paper Towers in the Cultural Background of Revering Script Paper: A case Study on Xintian County,Yongzhou City 敬惜字纸文化信仰背景下的惜字塔建筑装饰纹理研究——以永州市新田县为例. Traditional Chinese Architecture and Gardens 古建园林技术 6: 88–92. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Jianchuan, and Wanchuan Lin. 1999. Folk Religious Scripture Literature of the Ming and Qing Dynasties 明清民间宗教经卷文献. 11 vols. Taibei: New Wenfeng Publishing House 新文丰出版社, vol. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Xianqian. 1930. Commentary on Hou Han Shu 后汉书集解. Shanghai: The Commercial Press 商务印书馆. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Xingpin. 2001. Dissemination and Study of Wenchang Culture in Western Societies 文昌文化在西方社会的传播和研究. China Taoism 中国道教 2: 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yin. 1932. Records of Book Collections of the Ming and Qing Dynasties 明清螵林辑传. Beijing: Chinese Library Association中华图书馆协会. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Yi, and Chonggang Deng. 2016. Ziku: The Faith of Characters Written on Pagodas 字库书写在塔上的文字信仰. National Geographic China 中国国家地理 7: 132–47. [Google Scholar]

- Xinhuanet. 2021. Opinions on Strengthening the Protection and Inheritance of History and Culture in Urban and Rural Construction Issued by the General Office of the CPC Central Committee and the General Office of the State Council 中共中央办公厅 国务院办公厅印发《关于在城乡建设中加强历史文化保护传承的意见》. Bulletin of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China 中华人民共和国国务院公报 26: 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Zhitui. 1936. Yan’s Family Trainings 颜氏家训. Shanghai: Daode Bookstore 道德书局. [Google Scholar]

- Yinguang. 1940. Continuation of Venerable Yinguang’s Notes 印光法师文钞续编. Shanghai: Guoguang Publishing House 国光印书馆. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Qiuyu. 2012. The Chinese Literary Vein 中国文脉. Wuhan: Changjiang Literature & Art Press 长江文艺出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Qiuyu. 2019. The Chinese Literary Vein 中国文脉. Beijing: Beijing United Publishing Co., Ltd. 北京联合出版公司. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Huakun. 2008. The Constructing Principles and Form Analyses on Shanxi Pagodas in Early Period 山西早期佛塔营造理念与形态分析. Master’s thesis, Taiyuan University of Technology 太原理工大学, Taiyuan, China. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Yuchu. 1445. The Daozang of the Zhengtong Period 正统道藏. Beijing: the Ming Dynasty Royal Family 明朝皇室. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Yuhuan. 2000. Chinese Pagodas 中国塔. Taiyuan: Shanxi People’s Publishing House 山西人民出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Haiou. 2024. Books Store the Past and the Present and Nourish the Soul 书藏古今 滋养心灵. People’s Daily 人民日报 7: 007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Lipeng. 1991. Mathematical Analysis and Implications of the Evolution of the Plane of Ancient Pagodas in China 中国古塔平面演变的数理分析与启示. Huazhong Architecture 华中建筑 9: 46–48. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Lingli. 2011. Study on Sichuan Xizi Pagoda as Cultural Heritage and Its Preservation and Restoration 四川字库塔的文化遗产价值与保护修复研究. Master’s thesis, Southwest Jiaotong University 西南交通大学, Chengdu, China. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Lingli, and Xianjin Zhang. 2011. Interpretation of the Architectural Art of Xingxian Pagoda 兴贤塔字库建筑艺术的解读. Huazhong Architecture 华中建筑 29: 167–70. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Hui. 2013. The Etiquette and Cultural Construction of the Ancient Chinese Character Library Pagoda in Sichuan: Taking the Wenfeng Pagoda in Shangli, Ya’an, Sichuan as an Example 四川古代小品建筑字库塔的礼仪文化构筑——以四川雅安上里文峰塔为例. Journal of Panzhihua University 攀枝花学院学报 30: 52–55. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Xiechen. 1942. A Compilation of the Laws of Merit and Demerit Related to the Discussion in the Pure Land 净土问辨功过格合编. Shanghai: Guoguang Publishing House 国光印书馆. [Google Scholar]

- 백두현. 1998. An Examination of 19th Century Korean Literature19 세기 한글 문헌에 대한 고찰. The Waterlily Language Collection 수련어문논집 24: 70. [Google Scholar]

| Region | Location | Time of Construction | Shape of Plane | Number of Floors | Overall Height (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jiahe County, Chengzhou 郴州嘉禾县 | Xizi Pagoda in Chujiang Village 楚江村惜字塔 | (1814) Emperor Jiaqing’s reign 嘉庆十九年 | 4 Quadrilateral | 1 | 3.03 |

| Xizi Pagoda in Qingshan Village 青山村惜字塔 | (1816) Emperor Jiaqing’s reign 嘉庆二十年 | 6 Hexagonal | 3 | 4.30 | |

| Guiyang County, Chengzhou 郴州桂阳县 | Xizi Pagoda in Shanglongquan Village 上龙泉惜字塔 | (1821) Emperor Daoguang’s reign 道光元年 | 4 Quadrilateral | 1 | 1.62 (Remaining height) |

| Xizi Pagoda in Chenxi Village 陈溪村惜字塔 | (1862) Emperor Tongzhi’s reign 同治三年 | 6 Hexagonal | 3 | 5.68 | |

| Xizi Pagoda in Shuangjiang Village 双江村惜字塔 | (1875) Emperor Guangxu’s reign 光绪元年 | 6 Hexagonal | 5 | 9.30 | |

| Xizi Pagoda in Maofu Village 毛甫村惜字塔 | (1850) Emperor Daoguang’s reign 道光叁年 | 6 Hexagonal | 3 | 5.65 | |

| Xizi Pagoda in Zhongliu Village 中留村惜字塔 | (1875) Emperor Guangxu’s reign 清光绪元年 | 6 Hexagonal | 2 | 3.60 | |

| Linwu County, Chengzhou 郴州临武县 | Xizi Pagoda in Shihuiyao Village 石灰窑惜字塔 | (1839) Emperor Daoguang’s reign 清道光十九年 | 4 Quadrilateral | 1 | 2.59 |

| Xizi Pagoda in Shijia Village 石家村惜字塔 | Emperor Qianlong’s reign 清乾隆年间 | 6 Hexagonal | 3 | 4.05 | |

| Jianghua County, Yongzhou 永州江华县 | Xizi Pagoda in Daxu Town 大圩镇惜字塔 | Early Qing Dynasty 清初 | 6 Hexagonal | 5 | - |

| Xintian County, Yongzhou 永州市新田县 | Xizi Pagoda in Xiulingshui Village 秀岭水村惜字塔 | Qing Dynasty 清代 | 6 Hexagonal | 3 | 5.2 |

| Xizi Pagoda in Changfu Village 长富村惜字塔 | (1882) Emperor Guangxu’s reign 光绪八年 | 6 Hexagonal | 5 | 7.44 | |

| Xizi Pagoda in Pengzicheng Village 彭梓城村惜字塔 | Qing Dynasty 清代 | 6 Hexagonal | 4 | 11.35 | |

| Ningyuan County, Yongzhou 永州市宁远县 | Xizi Pagoda in Xiwan Village 西湾村惜字塔 | (1852) 清咸丰二年 | 6 Hexagonal | 2 | 4.1 |

| Xizi Pagoda in Pipagang Village 琵琶岗村惜字塔 | Qing Dynasty 清代 | 6 Hexagonal | 3 | 4.3 | |

| Xizi Pagoda in Tangtouling Village 塘头岭村惜字塔 | Qing Dynasty 清代 | 6 Hexagonal | 3 (Original 5) | 7.8 (Remaining height) | |

| Xizi Pagoda in Laobaijia Village 老柏家村惜字塔 | (1860) Emperor Xianfeng’s reign 清咸丰十年 | 6 Hexagonal | 3 | 6.5 | |

| Lengshuitan District, Yongzhou 永州市冷水滩区 | Xizi Pagoda in Xiangjiang West Road 湘江西路惜字塔 | Qing Dynasty 清代 | 6 Hexagonal | 3 | 8 |

| Jiangyong County, Yongzhou 永州市江永县 | Xizi Pagoda in Shanggantang Village 上甘棠村惜字塔 | Qing Dynasty 清代 | 8 Octagonal | 2 | 2.46 |

| Changsha County, Changsha 长沙市长沙县 | Xizi Pagoda in Xinzhong Village 新中村惜字塔 | (1830) Emperor Daoguang’s reign 清道光十年 | 6 Hexagonal | 2 | 4.50 |

| Wangcheng District, Changsha 长沙市望城区 | Xizi Pagoda in Chating Town 茶亭惜字塔 | (1838) Emperor Daoguang’s reign 道光十八年 | 6 Hexagonal | 5 | 12 |

| Xizi Pagoda in Shanmuqiao Town 杉木桥惜字塔 | (1887) Emperor Guangxu’s reign 清光绪十三年 | 6 Hexagonal | 5 | 15 | |

| Xizi Pagoda in Xinhua Village 新华村惜字塔 | (1843) Emperor Daoguang’s reign 清道光廿三年 | 6 Hexagonal | 2 | 4.0 | |

| Liuyang Gounty, Changsha 长沙市浏阳市 | Xizi Pagoda in Chudong Village 楚东村惜字塔 | (1907) Emperor Guangxu’s reign 清光绪三十三年 | 6 Hexagonal | 3 | 4.07 |

| Longhui County, Shaoyang 邵阳市隆回县 | Xizi Pagoda in Hebian Village 河边村惜字塔 | (1851) Emperor Xianfeng’s reign 清咸丰元年 | 4+8+6 Quadrilateral+Octagonal+Hexagonal | 3 | 14.5 |

| Shaoyang County, Shaoyang 邵阳市邵阳县 | Xizi Pagoda in Shutang Village 树塘村惜字塔 | (1851) Emperor Xianfeng’s reign 清咸丰元年 | 8 Octagonal | 5 | 7.05 |

| Shuangqing District, Shaoyang 邵阳市双清区 | Xizi Pagoda in Dongta temple 东塔寺惜字塔 | Qing Dynasty 清代 | 4+6 Quadrilateral+ Hexagonal | 2 | 5.15 |

| Liling County, Zhuzhou 株洲市醴陵市 | Xizi Pagoda in Weishan Village 沩山村惜字塔 | Qing Dynasty 清代 | 6 Hexagonal | 5 | 11.9 |

| Hengnan County, Hengyang 衡阳市衡南县 | Xizi Pagoda in Zhanhe Village 占禾村惜字塔 | (1886) Emperor Guangxu’s reign 清光绪十二年 | 6 Hexagonal | 3 | 5.0 |

| Xizi Pagoda in Chizu Village 赤足村惜字塔 | (1876) Emperor Guangxu’s reign 清光绪二年 | 6 Hexagonal | 4 | 10.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

He, Y.; He, L.; Zhou, Q.; Xie, X. Study on the Religious and Philosophical Thoughts of Xizi Pagodas in Hunan Province of China. Religions 2024, 15, 866. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15070866

He Y, He L, Zhou Q, Xie X. Study on the Religious and Philosophical Thoughts of Xizi Pagodas in Hunan Province of China. Religions. 2024; 15(7):866. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15070866

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Yiwen, Lai He, Qixuan Zhou, and Xubin Xie. 2024. "Study on the Religious and Philosophical Thoughts of Xizi Pagodas in Hunan Province of China" Religions 15, no. 7: 866. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15070866

APA StyleHe, Y., He, L., Zhou, Q., & Xie, X. (2024). Study on the Religious and Philosophical Thoughts of Xizi Pagodas in Hunan Province of China. Religions, 15(7), 866. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15070866