Maṇḍala or Sign? Re-Examining the Significance of the “Viśvavajra” in the Caisson Ceilings of Dunhuang Mogao Caves †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Rising Attention

3. Why Maṇḍala?

4. Which Maṇḍala?

4.1. The Directions

4.2. The Maṇḍala

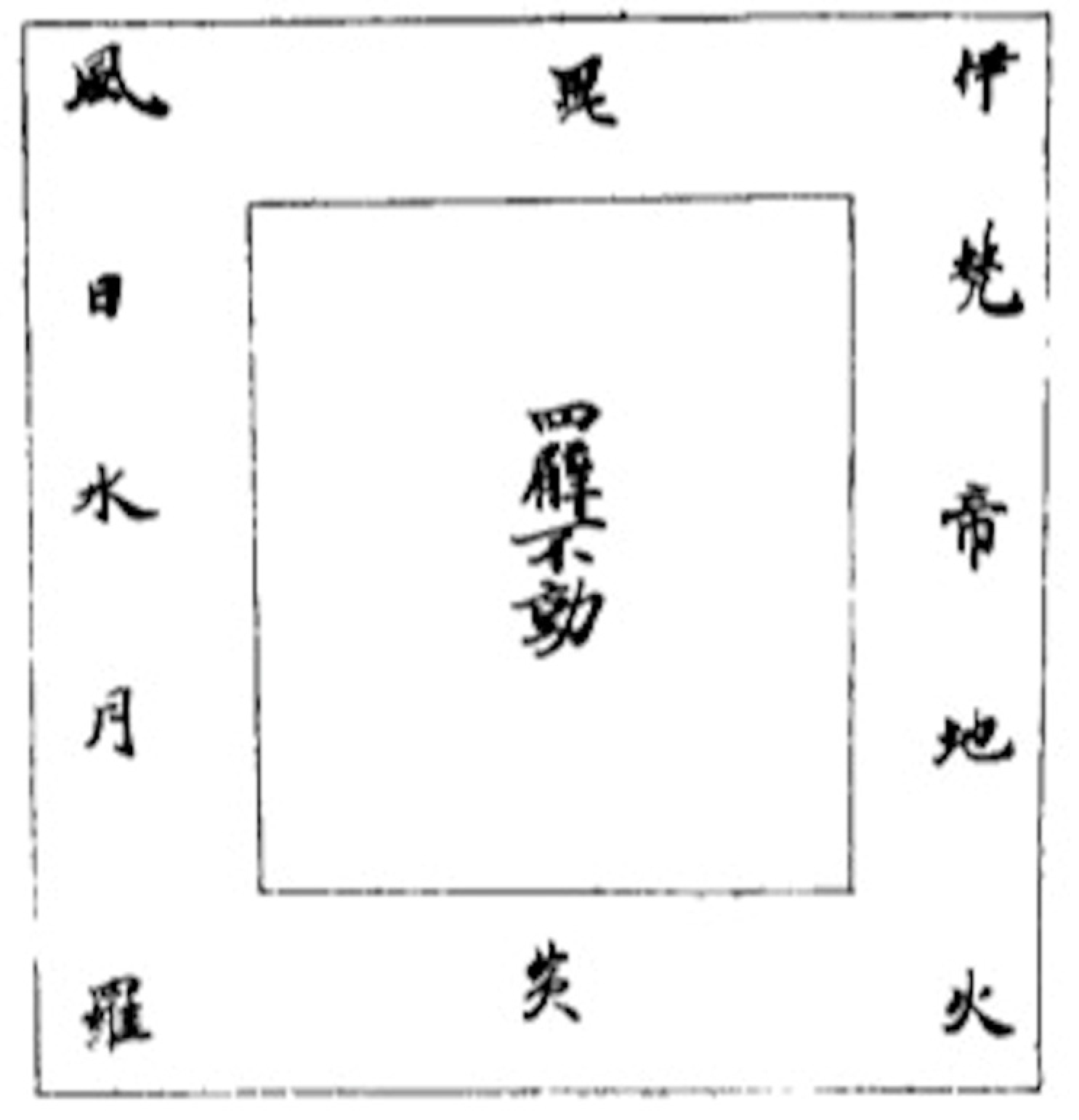

… There are five kinds of fire offering kuṇḍas, all of which should be depicted as three-layered. In the central part, a viśvavajra is drawn, with lotus leaves depicted in the four corners. In the second layer, the four signs, representing the four prajñā-pāramitā bodhisattvas, are depicted, and inner offerings are made within the four corners. In the third layer, the beings from the eight directional heavens are to be depicted at the four gates and four corners. The four external offerings are also depicted while in the center, is the Vairocana. This is the composition of śāntika kuṇḍa.11

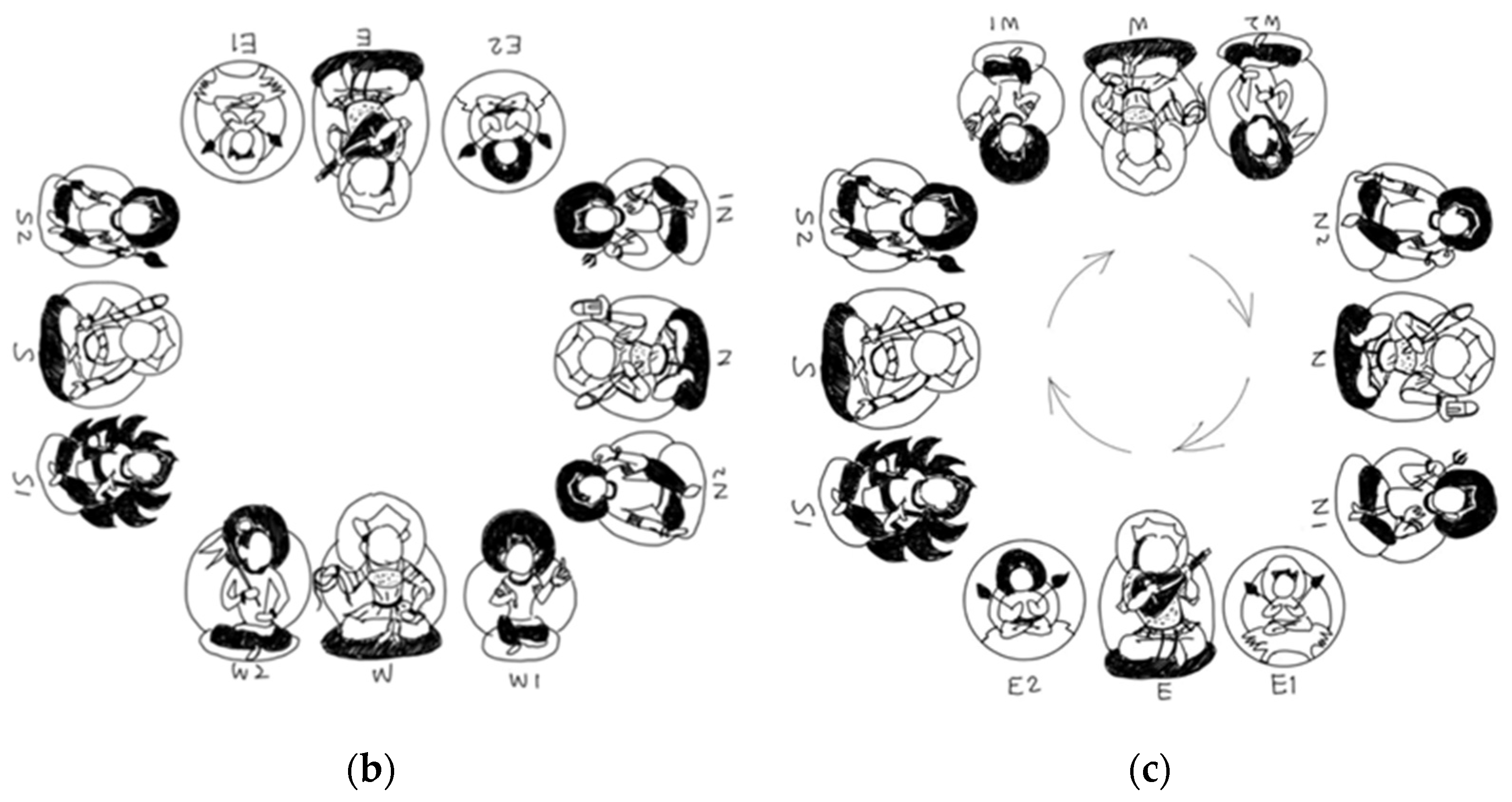

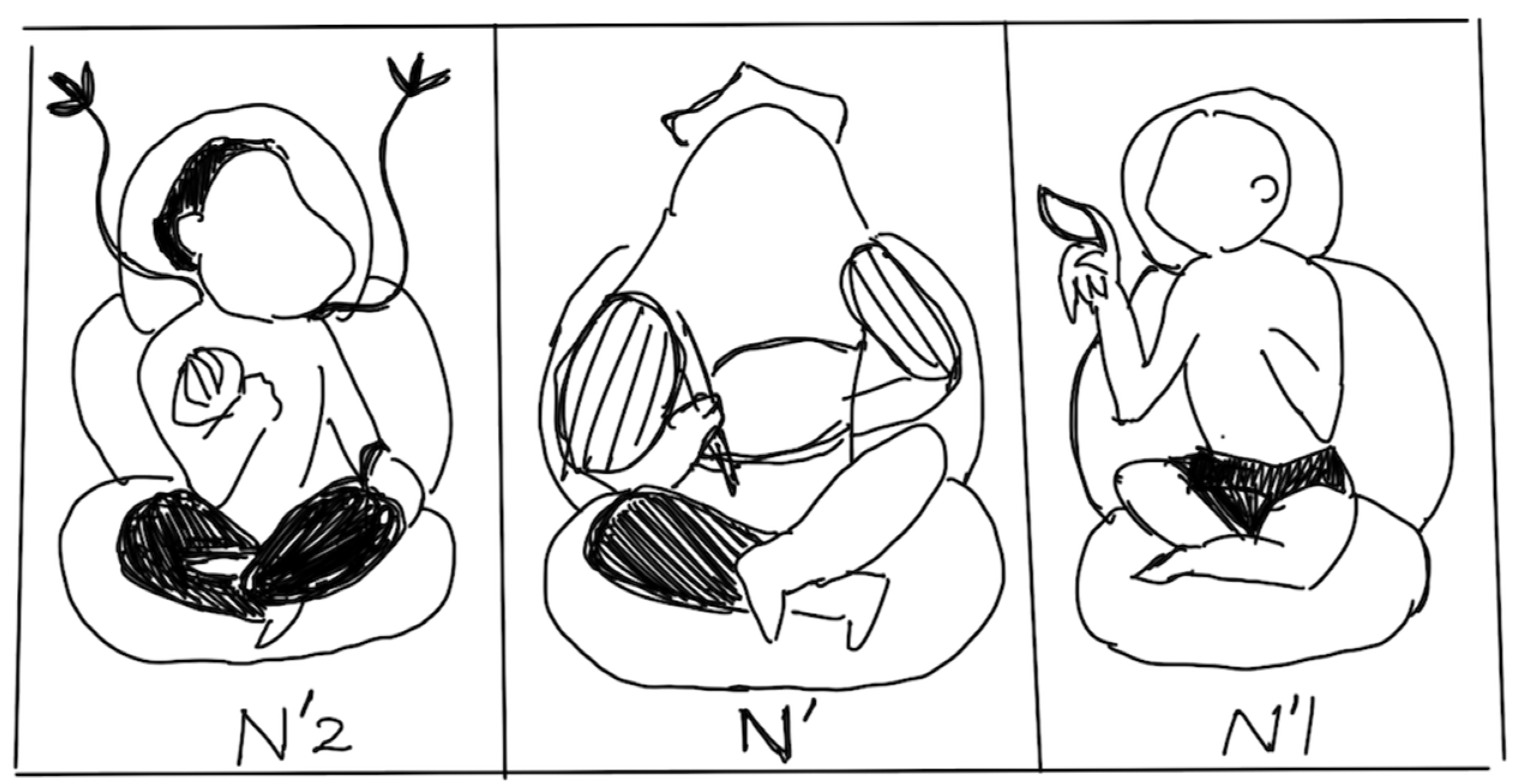

… All beings from the eight heavens, along with signs accompany the traveler. Beginning clockwise, the eastern heaven Indra is adorned with ribbons. Agni (S1), the Heaven of fire, holds a kundikā bottle, seated on a lotus throne engulfed in flames. Yama (S) is holding a two-pronged vajra decorated with human head, and his ribbons is also likely to Indra’s. Nairrtī (W1) wields a sword, seated on a throne surrounded by flames resembling Agni. Varuṇa (W), the Heaven of Water, holds a noose with both ends resembling like vajras. Vāyu (W2), the Heaven of Wind, bears a flag and sits within a lotus flower. Vaiśravaṇa (N) brandishes a staff, ribbons alike. Īśāna (N1), with a single-end trident, radiates flames upon a lotus throne. Wise individuals should understand this truth without error.16

Brahmā and Vasundhara are positioned to the right and left of Indra, with the eight directional heavens making up ten … Feeding these ten heavens … Additionally, two heavens are added among the original eight. Facing the upper heaven and the lower heaven are the sun Sūrya and the moon Candra.17

At that time, the bodhisattva Vajrapāṇi, empowered by the Buddha’s power, expounded the true practice of inner homa for all yogic practitioners. This practice was intended to forever subdue and eliminate afflictions and all demons and spirits. In performing such homa, one should increase samādhi by visualizing one’s yidam along with the respective colors of the directions. If performing the homa for the accomplishment of the Buddha family, the yogic practitioner should deeply contemplate Vairocana Buddha and visualize oneself as Vajrasattva.18

In the meditation of a homa furnace, within the vertically wide expanse of twelve fingers, establishing the seat for the central yidam. If practicing a fire offering ritual for dispelling calamities (śāntika maṇḍala) or increasing merits (pauṣṭika maṇḍala), the master should first visualize the presence of the Tathāgata Vairocana on the throne of yidam.19

Meditating on the formless fire emanating from a homa furnace internally possesses great power. Therefore, it is referred to as the inner fire offering ritual within the teachings.20

5. The Transitions from Mid-Tang to Western Xia

At that moment, the accomplished Tathāgata Amoghasiddhi for the sake of Śākyamuni Vairocana’s sign of all Tathagatas, engages in the practice of all paramita-samayas, and has attained the Vajra Empowerment Samadhi. All these samayas are self-enlightened.22

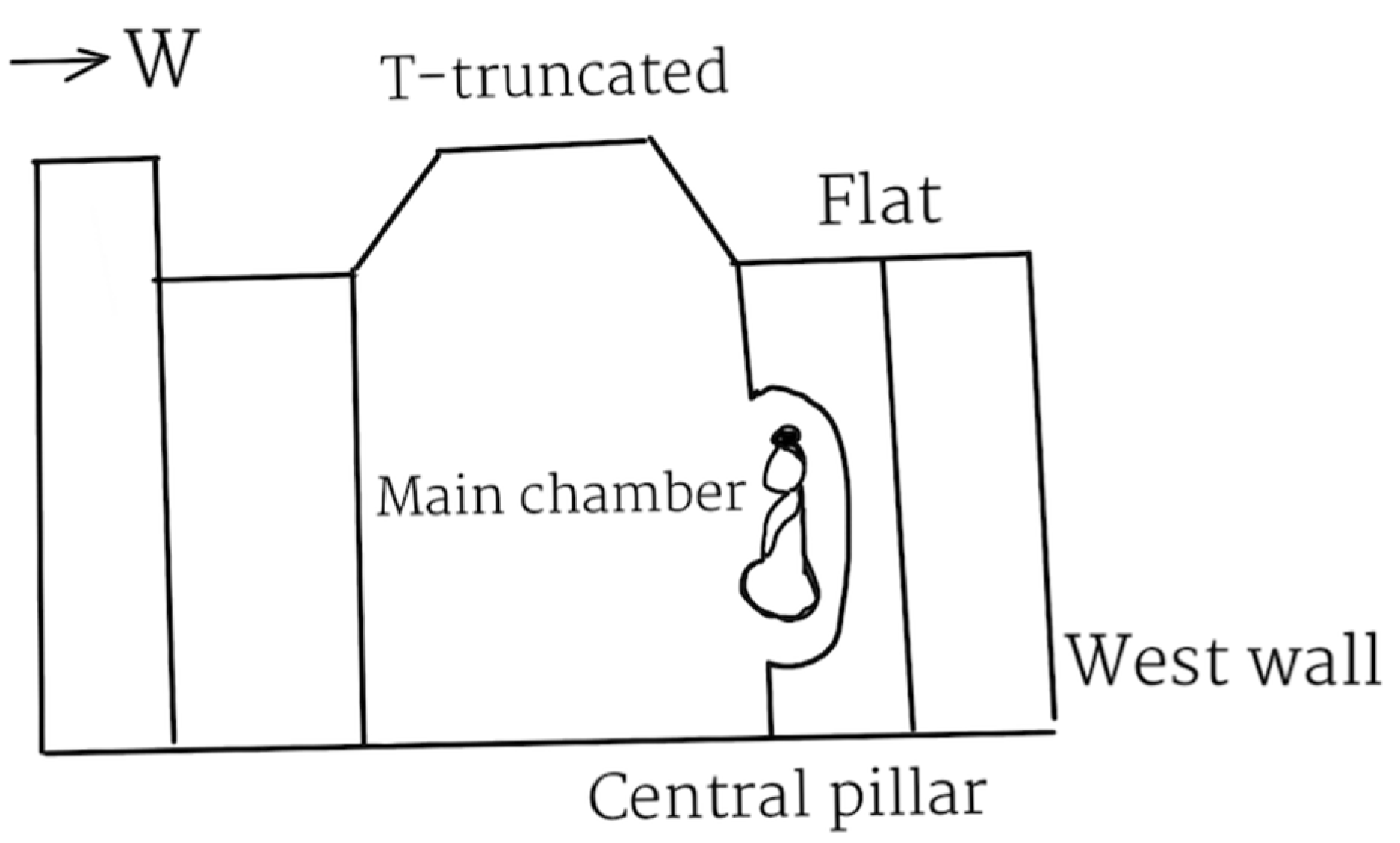

This gem-encrusted tower is square with four corners, four pillars and four doors … Now guru can open the door of this stūpa in the gem-encrusted tower. There are three Tathāgatas in this stūpa. Because of these three Tathāgatas have ultimate powers, showing the grant supernatural transformational accomplishment method. The three Tathāgatas are in this congregation.23

Those sixteen śrāmaṇeras, disciples of Buddha, have now all attained Anuttarā Samyaksaṃbodhi. In various worlds of the ten directions, they are presently teaching the Dharma, accompanied by innumerable hundreds of thousands of millions of bodhisattvas and śrāvakas as their attendants. Two of these śrāmaṇeras became Buddhas in the east: one named Akṣobhya in the Land of Joy, and the other named Merukūṭa. In the southeast, there are two Buddhas: one named Siṃhaghoṣa and the other named Siṃhadhvaja. In the south, there are two Buddhas: one named Ākāśapratiṣṭhita and the other named Nityaparinirvṛta. In the southwest, there are two Buddhas: one named Indradhvaja and the other named Brahmadhvaja. In the west, there are two Buddhas: one named Amitābha and the other named Sarvalōkadhātupadravodvega-pratyuttīrṇa. In the northwest, there are two Buddhas: one named Tamālapatra-candana-gandhâbhijña and the other named Merukalpa. In the north, there are two Buddhas: one named Meghasvaradīpa and the other named Meghasvararāja. In the northeast, there is one Buddha named Sarvalokādīptabhayamanyita-vidhvaṃsanakara. The sixteenth one is myself, Buddha Śākyamuni.24

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | 「殿屋之為園淵方井兼植荷花者,以厭火祥也。」(The halls and buildings incorporate round and square wells, with lotus flowers planted to prevent fire hazards.) See (Y. Shen 2011, p. 519). |

| 2 | Many thanks to Prof. Luo Huaqing 羅華慶 from the Dunhuang Academy. He provided me with the support needed to investigate these caves. |

| 3 | As discussed later in this article, Guo Youmeng considers the viśvavajra a key symbol suggesting a Vairocana maṇḍala. However, Robert Beer interprets it as a Buddhist sign representing the philosophical connection to the twelve nidānas 十二因缘. Venerable Ci Yi 慈怡, as explained in the Foguang Dictionary of Buddhism 佛光大辭典, also associates the viśvavajra with three prongs in each of the four directions as a metaphor for the destruction of the twelve nidānas. However, the correlation between a three-pronged viśvavajra and the twelve nidānas is only documented by Japanese monks such as Dōhan道範 (1179–1252 CE) and Chōgō 澄豪 (1259–1350 CE), with no direct evidence found in Chinese Buddhist texts. Additionally, the viśvavajra could also take shape in a five-pronged three-dimensional form. See (Guo 2009, pp. 143–74; Beer 2003, p. 95; Foguang da cidian bianxiu weiyuan hui 1968, p. 3245; and T78, No. 2502, 0879a15–16 and T77, No. 2412, 0079c11–0080a18). |

| 4 | The Huntington Archive, https://dsal.uchicago.edu/cgi-bin/huntington/show_detail.py?ObjectID=20939 (accessed on 4 March 2024). |

| 5 | As discussed later in this article, the primary motif of the caisson is a maṇḍala from the Vajra-dhatu Tantra. It wasn’t until the tenth to eleventh century, through the translation efforts of the renowned scholar Rin-chen-bzang-po (959–1055 CE), that this tantra became popularized in the Tibetan region. Prior to this, during the eighth to ninth century, Tibetans in the Hexi Corridor may have learned rituals from Chinese-translated tantras. However, before the mid-ninth century, the Maha-Vairocana Tantra had arrived and was welcomed by the Tibetan rulers. See (sBa-gsal-snang 1990, pp. 74–75). |

| 6 | While Chinese Buddhist canons do not typically distinguish between tantra and sūtra, the term yigui-jing 儀軌經, mannaluo-jing 曼拏羅經, tuoluoni-jing 陀羅尼經, and mimi-jing 秘密經, denoting sūtras of rituals, maṇḍalas or dhāraṇīs, should be classified under the tantra category within Buddhism. See (Payne 2013, pp. 71–113). |

| 7 | International Dunhuang Programme, https://idp.bl.uk/collection/81FF312DA3644094966A428765AFCE9D/?return=%2Fcollection%2F%3Fterm%3DCh.00189 (accessed on 4 March 2024). |

| 8 | 「正當四方面作羯磨杵,作金剛座之用。」T39, No. 1796, 697b25–26. |

| 9 | The Yuji-tu 禹跡圖 (1136 CE) is a north-up orientation while the Zhaoyu-tu 兆域圖designed in the Warring States Period (475–221 BCE) is a south-up orientation. See (Bol 2016, pp. 209–24; Unno 1982, p. 135). |

| 10 | 「行,前朱鳥而後玄武,左青龍而右白虎。」. |

| 11 | 「五種軍荼壇,應畫作三重。中院羯磨杵,四隅畫蓮葉。第二院四契,謂四波羅蜜,四隅內供養。第三院應畫,八方天眷屬,四隅於四門。外供養四攝,中安遍照尊,此息災軍荼。」T18, No. 908, 0916b21-27. |

| 12 | The Palace Museum, https://www.dpm.org.cn/collection/religion/234522.html (accessed on 31 May 2024). |

| 13 | 「揚掌申五輪,忍峰現羯磨,十字金剛輪。」T19, No. 1010, 0679c26–27. |

| 14 | 「息災爐正圓,應當如是作⋯⋯瑜伽者應用,息災爐作輪。」T18, No.908, 0916a22, 0916b13. |

| 15 | 「空中想大輪,五鈷而四面。」T18, No. 885, 0484b11. |

| 16 | 「八方天眷屬,亦如諸契等,皆隨行人座。而起於東方,帝釋獨股杵,繒繋左右飛。火天畫軍持,蓮座上火焔。焔摩兩股叉,其中安人頭,繒飛如帝釋。羅剎主畫刀,座焔如火天。水天畫羂索,兩頭猶股頭。風天作幡旗,而坐蓮花中。毗沙門作棒,繒繋亦如上。捨那半三股,蓮座火焔光。智者應善知,審諦無錯謬。」T18, No. 908, 0917b01–12. |

| 17 | 「於帝釋右左。置梵天地天位。與八方而十⋯⋯以施十方天食⋯⋯於八方中,加兩位,與上下天對。曜東宿西。」T18, No. 908, 0919b02–05, 0920a16. |

| 18 | 「爾時金剛手菩薩摩訶薩,承佛威神,爲修一切瑜伽行者,演説眞實内護摩法。永爲調伏滅煩惱賊,及一切鬼神故。作如護摩,増長三昧,各觀本尊并本方色。若作佛部成就護摩,瑜伽行者諦觀毘盧遮那如來,想我即是金剛薩埵。」T18, No. 868, 282a10–14. |

| 19 | 「觀想護摩爐內縱廣十二指,作安本尊位,若作息災増益法,先觀本尊位上有毗盧遮那如來。」T18, No. 889, 0550c22–24. |

| 20 | 「內心觀想護摩無性之火,有大勢力,是故教中所說內心護摩。」T21, No. 1272, 0316c08–10. |

| 21 | While Cave 177 was built in the late Tang period, the viśvavajra was painted during the Northern Song dynasty. See (Dunhuang Academy 1982, p. 61). |

| 22 | 「爾時不空成就如來,為世尊毗盧遮那一切如來遍智契故,入一切波羅蜜三摩耶,所生金剛加持三摩地已。此一切三摩耶自已契。」T18, No. 866, 0234b23–25. |

| 23 | 「其樓閣四角四柱四門⋯⋯今可開此寶樓閣窣覩波門。於彼窣覩波中,有三如來身,由此三如來威神力故,現大神變殊勝之相。彼三如來於此會中。」T19, No. 1005A, 0622a09-13. |

| 24 | 「彼佛弟子十六沙彌,今皆得阿耨多羅三藐三菩提,於十方國土,現在説法有無量百千萬億菩薩聲聞,以爲眷屬。其二沙彌東方作佛,一名阿閦在歡喜國,二名須彌頂。東南方二佛,一名師子音,二名師子相。南方二佛,一名虚空住,二名常滅。西南方二佛,一名帝相,二名梵相。西方二佛,一名阿彌陀,二名度一切世間苦惱。西北方二佛,一名多摩羅跋栴檀香神通,二名須彌相。北方二佛,一名雲自在,二名雲自在王。東北方佛名壞一切世間怖畏,第十六我釋迦牟尼佛。」T9, No. 262, 0025b23–c06. |

| 25 | However, Tibetan scholar Sangs-rgyas-bkra-shis argued that “Adun-Xili” and “Yan-mei” are both translations from Tibetan names. See (Sangs-rgyas-bkra-shis 2011, pp. 49–57). |

| 26 | Although Caves 30 and 140 were originally built in the late Tang period, they both underwent reconstruction during the Western Xia dynasty. The style of the caisson aligns with that of the Western Xia era. See (Dunhuang Academy 1982, pp. 11 and 46). |

| 27 | The Chinese text known as the sūtra Da ri jing 大日經 (Vairocanābhisaṃbodhi Sūtra) is, in fact, classified as a tantra within the category of Buddhist literature. |

References

Primary Sources

Shen, Yue 沈約 (441–531 CE) ed. 2011. Zhi di ba, Li wu 志第八, 禮五 [The eighth volume of Zhi, the fifth chapter of Li] in Song Shu宋書 (Books of Song). Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company 中華書局, p. 13.T= SAT Daizōkyō Text Database 大正新脩大蔵経 [The Tripiṭaka Newly Edited in the Taishō Era (1912–1926 CE)]. Edited by Takakusu Junjirō 高楠順次郎 (1866–1945 CE) and Watanabe Kaigyoku 渡辺海旭 (1872–1933 CE). 100 vols. Tokyo: Taishō/Issai-Kyō Kankō kwai.(T9, No.262) Miaofa lianhua jing 妙法蓮華經 [The Wonderful Dharma Lotus Sūtra]. Translated by Kumārajīva (344–413 CE).(T10, No.279) Da fang guang fo Huayan jing 華嚴經 (The Flower Garland Sūtra).Translated by Śikṣānanda (652–710 CE).(T18, No.866) Jingang ding yujia zhong lüe chu niansong jing 金剛頂瑜伽中略出念誦經 [Sūtra Abridged for Recitation]. Translated by Vajrabodhi (669–741 CE).(T18, No.868) Zhu fo jingjie she zhenshi jing 諸佛境界攝眞實經 [Reality Assembly of the Attained Realm of the Buddhas]. Translated by Prajñā (734 CE–?).(T18, No.885) Fo shuo yiqie rulai jingang sanye zuishang mimi da jiaowang jing 佛説一切如來金剛三業最上祕密大教王經 [Guhyasamājatantra]. Translated by Dānapāla (?–1017 CE).(T18, No.889) Yiqie rulai da mimi wang weiceng you zuishang weimiao da mannaluo jing 一切如來大秘密王未曾有最上微妙大曼拏羅經 [Great Secret Wondrous Abdhuta-Dharma Maṇḍala of All Tathāgata Tantra]. Translated by Devaśāntika (?–1000 CE).(T18, No.901). Tuoluoni ji jing 陀羅尼集經 [Dhāraṇī Collection Scripture]. Translated by Atikūṭa (?-?)(T18, No.908) Jingang ding yujia humo yigui 金剛頂瑜伽護摩儀軌 [Homa Ritual Procedures of the Vajra Pinnacle Yoga]. Translated by Amoghavajra (705–774 CE).(T18, No.909) Jingang ding yujia humo yigui 金剛頂瑜伽護摩儀軌 [Homa Ritual Procedures of the Vajra Pinnacle Yoga]. Translated by Amoghavajra (705–774 CE).(T19, No.1010) Fo shuo chusheng wubian men tuoluoni yigui 佛說出生無邊門陀羅尼儀軌 [Scripture of the Sublime Grasp of the Immeasurable Portal]. Translated by Amoghavajra (705–774 CE).(T19, No.1005A) Dabao guangbo louge shanzhu mimi tuoluoni jing 大寶廣博樓閣善住祕密陀羅尼經 [Most Secret, Well-Established Dhāraṇi of the Vast, Widely Renowned, Gem-Encrusted Tower]. Translated by Amoghavajra (705–774 CE).(T20, No.1191) Wenshu shili genben yigui jing 文殊師利根本儀軌經 [Mañjuśrī-mūla-kalpa]. Translated by Devaśāntika (?—1000 CE).(T21, No.1272) Jingang saduo shuo pin na ye jia tian chengjiu yigui jing 金剛薩埵說頻那夜迦天成就儀軌經 [Vajrasattva Tells of Vināyaka Accomplishment Ritual Tantra]. Translated by Devaśāntika (?–1000 CE).(T39, No.1796) Da pi lu zhe na chengfo jingshu 大毗盧遮那成佛經疏 [Commentary on the Vairocana Tantra]. Translated by Yi Xing (683-727 CE).(T61, No.2225) Jingang ding da jiaowang jing siji 金剛頂大教王經私記 [Private Notes on the Vairocana Tantra]. Written by Donjyaku (1674–1742 CE).(T77, No.2412) Zongchi chao總持抄 [Notes on Dhāranī]. Written by Chōgō (1259–1350 CE).(T78, No.2502) Xingfa gan ye chao行法肝葉鈔 [Notes on the Methods of Practice]. Written by Dōhan (1179–1252 CE).Takakusu, Junjirō, ed. 1978. Taishō shinshū daizōkyō zuzōbu 大正新脩大藏經図像部 [Images of SAT Daizōkyō]. Tokyo: Daizo shuppan大蔵出版, vol. 1, p. 1169, no.1; vol. 2, p. 491, no. 18 and vol. 4, p. 168, no. 57.Yin, Zhenre 尹真人. Xingming shuangxiu wanshen guizhi (Yuan) 性命雙修萬神圭旨(元) [The Guiding Principles of Ten Thousand Spirits on Dual Cultivation of Nature and Life (Yuan)]. Qianlong period (1736–1795 CE), Block-printed edition, p. 38.Secondary Sources

- Beer, Robert. 2003. The Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols. Boston: Shambhala. [Google Scholar]

- Bol, Peter K. 2016. Exploring the Propositions in Maps: The Case of the “Yuji Tu” of 1136. Journal of Song-Yuan Studies 46: 209–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunhuang Academy 敦煌研究院, ed. 1982. Dunhuang Mogaoku neirong zonglu 敦煌莫高窟内容總錄 [The Overall Record of Dunhuang Mogao Grottoes]. Beijing: Culture Relics Press 文物出版社, pp. 1–176. [Google Scholar]

- Dunhuang Academy 敦煌研究院, ed. 1986. Mogaoku gongyang ren tiji 敦煌莫高窟供養人題記 [Inscriptions by Donors at the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang]. Beijing: Culture Relics Press 文物出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Dunhuang Academy 敦煌研究院, ed. 1987. Zhongguo shiku: Dunhuang Mogaoku 5 中國石窟: 敦煌莫高窟5 [Cave Temples in China: Dunhuang Mogao Caves 5]. Beijing: Culture Relics Press 文物出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Dunhuang Academy 敦煌研究院, ed. 1996. Dunhuang shiku yishu, Mogaoku di yi si ku 敦煌石窟藝術: 莫高窟第一四窟 [Dunhuang Cave Art: Mogao Cave 14]. Nanjing: Jiangsu Art Publishing House 江蘇美術出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Dunhuang Academy 敦煌研究院, ed. 2012. Zhongguo shiku: Anxi Yulin ku 中國石窟:安西榆林窟 [Cave Temples in China: Anxi Yulin Caves]. Beijing: Culture Relics Press 文物出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Dunhuang Academy 敦煌研究院, ed. 2016. Dunhuang shiku yishu quanji 14 敦煌石窟藝術全集14 [The Complete Collection of Dunhuang Cave Arts 14]. Shanghai: Tongji University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson, James, and J. Burgess. 1880. The Cave Temples of India. London: W.H. Allen & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Foguang da cidian bianxiu weiyuan hui 佛光大辭典編修委員會, ed. 1968. Foguang da cidian 佛光大辭典 [Foguang Dictionary of Buddhism]. Taipei: Foguang Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Youmeng 郭祐孟. 2006. Dunhuang mijiao shiku tiyong guan chutan- yi Mogao ku 14 ku weili kan Fahua mjiao de kaizhan 敦煌密教石窟體用觀初探—以莫高窟14窟為例看法華密教的開展 [A Preliminary Exploration of the Essence and Application of Dunhuang Esoteric Buddhist Caves—Examining the Development of Fahua Esoteric Buddhism with Cave 14 of the Mogao Grottoes as an Example]. Yuanguang Foxue Xuebao 圓光佛學學報 10: 139–67. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Youmeng 郭祐孟. 2009. Dunhuang Mogaoku 361 ku zhi yanjiu 敦煌莫高窟361 窟之研究 [Research on Dun-huang Mo-kao Cave 361]. Yuanguang Foxue Xuebao 圓光佛學學報 15: 143–74. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Yingjie 黃英傑. 2014. Jue Yuan de Huayan mijiao panjiao guan tanxi 覺苑的華嚴密教判教觀析探 [Jue Yuan’s Analysis and Exploration of Huayan Esoteric Buddhism Discrimination Doctrine]. In 2013 Huayan zhuan zong guoji xueshu yantao hui lunwen ji 2013 華嚴專宗國際學術研討會論文集 [2013 Collected Papers of the International Academic Conference on Huayan Buddhism]. Taipei: Huayen Lotus Association 華嚴蓮社, pp. 291–316. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, Richard K. 2013. Mijiao zai dongya daolun《密教在東亞》導論 [Introduction: Tantric Buddhism in East Asia]. In He wei mijiao? Guanyu miijiao de dingyi, xiuxi, fuhao he lishi de quanshi yu zhenglun 何謂密教?關於密教的定義、修習、符號和歷史的詮釋與爭論 [What’s Tantrism? The Interpretation and Controversy of the Definition, Practice, Semiology, and Historiography of Tantrism]. Translated by Shen Li 沈麗, and Kung Ling-wei 孔令偉. Edited by Weirong Shen 沈衛榮. Beijing: China Tibetology Publishing House 中國藏學出版社, pp. 71–113. [Google Scholar]

- Sangs-rgyas-bkra-shis 桑吉扎西. 2011. Dunhuang Tubo shiqi de zangchuan fojiao huihua yishu 敦煌石窟土蕃時期的藏傳佛教繪畫藝術 [Tibetan Buddhist Paintings of the Tubo Period in the Dunhuang Caves]. Fa Yin 法音 2: 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- sBa-gsal-snang (active in the eighth century). 1990. Ba xie (zengbu ben) yizhu 拔協(增補本)譯注 [sBa-bzhed-ces-by-aba-las-sba-gsal-snang-gi-bzhid-pa-bzhugs]. Translated by Jinhua Tong 童錦華, and Huang Bufan 黃布凡. Chengdu: Sichuan Ethnic Publishing House 四川民族出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto, Keishō 塚本啓祥, Matsunaga Yūkei 松長有慶, and Isoda Hirofumi 磯田煕文. 1989. A Descriptive Bibliography of the Buddhist Sanskrit literature, IV: The Buddhist Tantra 梵語佛典の研究:密教経典篇. Kyoto: Heirakuji Bookstore 平楽寺書店. [Google Scholar]

- Unno, K. 1982. Note on an Early Chinese Mausoleum Plan. Imago Mundi 34: 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Guangming 殷光明. 2014. Dunhuang xianmi wufangfo tuxiang de zhuanbian yu fashen sixiang 敦煌顯密五方佛圖像的轉變與法身思想 [Evolution of the Five-Buddha Images in Esoteric Buddhism with Chinese Characteristics at Dunhuang and Thoughts on Dharmakaya]. Dunhuang Research 敦煌研究 143: 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Xiaoxin 趙曉星. 2017. Tubo tongzhi shiqi Dunhuang mijiao yanjiu 吐蕃統治時期敦煌密教研究 [Study of Esoteric Buddhism in Dunhuang during the Tibetan Rule over Dunhuang]. Lanzhou: Gansu Education Publishing House 甘肅教育出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Zhongguo Banhua Quanji bianwei hui, ed. 2008. Zhongguo banhua quanji 1 中國版畫全集·1 [The Complete Collection of Chinese Woodblock Prints 1]. Beijing: Forbidden City Publishing House 紫禁城出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Yiliang 周一良. 1996. Tang dai mi zong 唐代密宗 [Tantrism in Tang Dynasty]. Translated by Wenzhong Qian 錢文忠. Shanghai: Shanghai Far East Publishing House 上海遠東出版社, pp. 55–79. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shen, L. Maṇḍala or Sign? Re-Examining the Significance of the “Viśvavajra” in the Caisson Ceilings of Dunhuang Mogao Caves. Religions 2024, 15, 803. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15070803

Shen L. Maṇḍala or Sign? Re-Examining the Significance of the “Viśvavajra” in the Caisson Ceilings of Dunhuang Mogao Caves. Religions. 2024; 15(7):803. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15070803

Chicago/Turabian StyleShen, Li. 2024. "Maṇḍala or Sign? Re-Examining the Significance of the “Viśvavajra” in the Caisson Ceilings of Dunhuang Mogao Caves" Religions 15, no. 7: 803. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15070803

APA StyleShen, L. (2024). Maṇḍala or Sign? Re-Examining the Significance of the “Viśvavajra” in the Caisson Ceilings of Dunhuang Mogao Caves. Religions, 15(7), 803. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15070803