Weituo 韦驮 is one of the most frequently represented protective deities in Chinese Buddhist temples. The statue of Weituo is enshrined in virtually every standard Buddhist temple in China today, and at a unique location—in the entrance hall for the four Heavenly Kings and facing inward. Why is the Weituo statue placed at this place and why is he looking inward? The Chinese Weituo can be traced back to the Hindu god Skanda. In the past, the few studies on Weituo have focused mainly on his origin (

Péri 1916, pp. 41–56;

Y. Shi 1992, pp. 248–49;

S. Shi 1979, pp. 165–86;

F. Shi 2012;

Rösch 2007, pp. 102–11;

Nobumi 2002, pp. 33–152;

Yu 2022, pp. 85–93). The placement of Weituo’s image in the temple complex, however, has not drawn much attention from art historians. There were a few early scholars who were aware of the special functions of Weituo in Chinese Buddhism, but they only recognized Weituo as the “guardian of the sanctuary” (

Reichelt 1927, p. 245) or “protector of monasteries” (

Welch 1967, pp. 49, 79), in addition to his role as a protector of the Dharma. If Weituo protects the monastery, what is the difference between Weituo and Guan Yu 關羽 in Chinese Buddhism? Guan Yu, who is known as Qielan Pusa 伽蓝菩萨 or the “Bodhisattva of the Temple”, is actually a territory deity associated with the sanctuary.

1 In a more precise description, I propose that in China, Weituo was transformed into the patron deity of the

saṅgha or monastic community, the role of which results in the various locations of his images in Chinese Buddhist temple complexes, whereas Guan Yu is the protector of the sanctuary. Going beyond Weito’s identities, and the iconography and style of his images, in this paper, I attempt to interpret Weituo images in Chinese Buddhist temple space through the transformation of Weituo in China and the worship of Weituo in the Chinese monastic community.

1. From Skanda to Weituo: The Identities in China

It is a common perception among modern scholars that, from a very early time, Skanda in Indian mythology was the origin of Weituo (

Péri 1916, pp. 41–56). Skanda (“to leap or to attack”), who is also called Kumāra (“youthful”), Kārttikeya (“from six Kṛttikā”?), Murugan (“handsome”), Shanmukha (“six faced”), and various other names, is an old Vedic god and later became an important member of the Hindu pantheon. In Vedic literature, he is a son of Agni (fire god), and was born to bring forth more fierce power than his father to fight Asuras (semi-gods). In Hindu mythology, he is a son of Śiva. Among all his qualifications, he is best known as the General of the Army of the Devas (gods), and he eventually defeated the Asuras,

2 thereby replacing Indra and Agni and becoming the “god of war”. He also came to be associated with children (

Rana 1995, p. 41). In addition, he is also known as a malevolent god, e.g., he can spread disease;

3 and he came to be a patron deity of thieves (

Rana 1995, pp. 62–88).

Scholars usually trace the cult of Skanda in India back to the Maurya period (322–185 BCE), based on Patañjali’s commentary of the

Pāṇini’s Sutra.

4 With different names, Skanda was worshipped in different regions throughout India from early times. The Skanda cult became popular first in south India and then spread to the north, as well as other parts of south Asia and southeast Asia (

Rana 1995, pp. 89–124;

Thakur 1981, pp. 85–90;

Mann 2007, pp. 447–70). In standard Hindu iconography, Skanda appears as child and his vehicle is a peacock, the most recognizable attribute in his iconography. His form with one head and one pair of arms emerged first. The form of six heads did not appear until the Gupta period (320–550 CE).

5 In China, several images of Skanda of the pre-Tang period have survived, in Yungang Cave 8 (the second half of the fifth century) (

Shanxi Yungang Shiku Wenwu Baoguangsuo 1981, p. 17), Dunhuang Cave 285 (538–539) (

Dunhuang Yanjiuyuan 1982, pl. 119), and on a Dharmadhātu (Dharma-field) Buddha sculpture, which is also called “cosmological Buddha” in English, in the Freer Gallery (Sixth Century) (

Figure 1). In Yungang Cave 8, the Skanda image is carved on the door jamb with Maheśvara, a form of his father Śiva, on the opposite side. In Dunhuang Cave 285, Skanda is included in the Buddha’s assembly of a number of Hindu deities around the main shrine. On the cosmological Buddha sculpture, Skanda is carved on the surface of the Buddha sculpture located in the middle area between the heaven and hell as part of the cosmological world system. Again, the Skanda image is paired with Maheśvara here. All these Skanda images follow the Indian iconography of Skanda: a child riding on a peacock, with multiple arms or even with multiple heads.

Like other non-Buddhist deities in India, Skanda was subsumed into Buddhism. In the textual tradition, Skanda appears in a number of texts translated into Chinese in the early fifth century, especially those by Dhārmakṣema (385–433). For instance, in the

Mahāparinirvāṇa-sūtra and

Mahāmegha-sūtra, Skanda is mentioned as a non-Buddhist deity along with other popular Brahmanic gods; whereas in the

Suvarṇaprabhāsa-sūtra, or the

Golden Light Sūtra, as Weituo, he becomes an important Dharma-protector in Buddhism (T 16:663.350a;

Dawatrans 2006, p. 68). The

Golden Light Sūtra is an important Mahāyāna text and became extremely popular in East Asia because the text is all protections of the gods.

However, in China, Weituo, who became popular later, has little to do with the original functions and legends of the Indian Skanda. Daoxuan’s account redefined the nature of this deity. Daoxuan’s tale resulted in the special worship of Weituo in China. The new identity of Weituo was firmly established from the Daoxuan’s time on. Later accounts about this deity in the Buddhist tradition basically repeat Daoxuan’s description, with only some minor elements added.

Master Daoxuan was the founder of the Chinese Vinaya School (Lüzong), a school that emphasizes monastic rules (

vinaya). Daoxuan dedicated his life to promoting the

Dharmagupta-vinaya and wrote extensively on the vinaya. It is said that since Daoxuan was so keen to establish the right vinaya for the Chinese that gods in the heaven came to assist him and show him the Buddha’s original intention.

6 In such miraculous encounters with messengers from the heaven, Daoxuan heard about a god called Wei Jiangjun 韦将军, or General Wei, an alternative appellation of Weituo.

7 According to Daoxuan’s

Daoxuan lüshi gantong lu 道宣律師感通錄 (

Records of Miraculous Responses of the Vinaya Master Daoxuan) (664) (T 52:2107.435a–442b) and Daoshi’s

Lüxiang gantong zhuan 律相感通傳 (

Records of the Miraculous Responses to the Manifestations of the Vinaya) (667) (T 45:1989.874a–882a):

“General Wei is a general under the South Heavenly King. He is very busy. General (Wei) protects the Buddhist Dharma in three continents. If there is any dispute or peril, he will go in person and solve it”.

(T 45:1989.874c)

“General Wei kept the purity of children and practiced brahmacharya (chastity). He is freed from gods’ desire. There are eight generals under each Heavenly King. In total there are four Heavenly Kings and thirty-two generals in the four directions of the world. They patrol the world and protect monks and nuns. Among the four directions, Buddhist Dharma in the northern continent is scarce; and on the other three continents, Buddhist Dharma thrives. Nevertheless, monks and nuns often break their vows. Not many of them follow the vinaya. People in the East and West lack wisdom and are vexatious. It is difficult to convert them. Though in the southern continent many commit crimes, their minds can be easily tamed. Right before the nirvāṇa, the Buddha entrusted General Wei in person to protect the saṅgha from demons. “If no one protects monks and nuns, and they violate the precepts like such, who else will practice my Dharma teachings?” …among the thirty-two generals, General Wei exerts the greatest protection. Sons and daughters of demons often disturb monks who have less strength, and confuse them with delusions. General Wei will rush there and eliminate the danger accordingly”.

(T 45:1989.874c28–875a16)

By means of all these descriptions, the Indian god Skanda, who must have been very alien to the Chinese, now obtained a new name and identity.

First, the god was a general under the Southern Heavenly King. For human beings on the southern continent in the Buddhist cosmological world system, he would therefore be the first god directly in charge. Accordingly, Weituo also obtained a new appearance, different from that of Skanda: the outfit of a Tang general similar to that of the Heavenly Kings.

Second, entrusted directly by the Buddha, General Wei or Weituo is described as being in charge of protecting the Dharma of all the three continents, and he “exerts the greatest protection”. As a result, surpassing all protective deities, he became the most important Dharma-protector in China.

Third, General Wei committed himself to the practice of chastity (brahmacharya). He specifically guards the monks to make sure they do not violate vinaya or break their monkhood in this regard. General Wei’s concerns, as described by Daoxuan, clearly reflect Daoxuan’s interests as a vinaya master with the ambition to establish monastic rules for Chinese monks. Furthermore, Daoxuan also specifically mentioned that Weituo protects monks from being disturbed by demons. These characteristics of Weituo established him as a guardian deity for the Chinese monastic community. This special identity and function of Weituo has so far not been fully acknowledged.

It is from the late seventh century that the Chinese started to set up the image of Weituo in Buddhist temples. According to Xingting’s 行霆 Chong bian zhutian zhuan 重编诸天传 (1173) of the Southern Song dynasty, “since the time of Emperor Gaozong (628–683) from the Tang dynasty, everywhere when Buddhist temples were constructed or reconstructed, images [of Weituo] were set up for veneration” (X 88:1658.430b).

The earliest extant image of Weituo (857), which can be dated to the Tang dynasty, has survived in the Eastern Hall in the Foguang Si 佛光寺, the second oldest extant wooden architecture in China, near Wutai Mountain in Shanxi Province (

Figure 2, no. 25 in the ground plan).

8 This statue typifies the iconography of the deity in China: a youthful Chinese-looking face, wearing helmet and armor, and holding a long

vajra-mallet.

9 This iconography of Weituo has been quite consistent since the Tang dynasty. As mentioned by Daoxuan, Weituo is said to have the purity of a child. Accordingly, the Chinese created him with a youthful image, often without mustache. This feature is coherent with his precursor, the image of Skanda in India. Being a son of Agni/Śiva, Skanda in Indian art appears like a child. Weituo’s armor aligns with his title of general and also the original nature of Skanda as a god of war.

2. The Worship of Weituo as the Protector of the Saṅgha

Weituo has been popular among monks and nuns since the Tang dynasty, and the worship of Weituo was incorporated into ritual practice that was written into the monastic rules of Buddhist temples during the Song dynasty. As the monastic rules of various schools and temples became increasingly comprehensive during the Ming and Qing dynasties, greater numbers of Weituo-related rituals were enlisted in those monastic regulations.

In Chinese Buddhist monastic communities, Weituo’s name is chanted in the daily recitation rite. Special rituals are dedicated to him monthly and annually. Additionally, Weituo is also evoked in a number of other rites related to monastic life, especially the summer meditation retreat.

Chanting Buddhist texts daily in the morning and evening is an old Buddhist practice that was first introduced into China during the Three Kingdoms (220–265). In the Tang dynasty, the Chinese Buddhist community developed its own daily chanting ritual, which was practiced in some monasteries during the Tang and Song periods. This practice was standardized and widely spread by the end of the Ming dynasty (

Chen 1999, pp. 79–80). The contemporary liturgy of the daily recitation rite is known as the

Fomen risong 佛门日诵 (

The Buddhist Daily Recitation), or

Zhaomu kesong 朝暮课诵 (

The Morning and Evening Recitation). It consists of a variety of Buddhist practices, the most important of which is the recitation of a group of carefully selected Buddhist texts and

dhāraṇi to evoke the Buddhist teachings and protections. These daily recitations are conspicuous mental and physical exercises designed as being fundamental to the training and activities for the

saṅgha and their aim is to stabilize the mind and obtain tranquility. In these daily practices, Weituo is invoked in the morning service,

10 whereas the Qielan Pusa Guan Yu, the protector of the monastery, is invoked in the evening service. In the morning recitation, Weituo is first invoked by chanting his name three times,

11 then monks recite the

Praise for Weituo—Weituo, the heavenly general, a Bodhisattva in transformation

To support Buddha Dharma, his vows are grand and profound.

With the precious chu (vajra-mallet) he subdues the demonic army

His merits hardly matched

Now we pray to you to guard our minds

Pay homage to the Pervasive-eye Bodhisattva-Mahāsattva

Mahāprajñapāramita.

As explicated in this praise, the purpose of invoking Weituo is to guard the monks’ minds. It is interesting to note that before the

Praise for Weituo, monks chant thrice the

Shannu Tian 善女天 (

Benevolent Goddess)

Dhāraṇi. Shannu Tian is an alternative name of Haritī, who was enshrined in virtually all Buddhist temples and to some extent served as a protector of the monk community in India.

The earliest extant version of the contemporary liturgy of the daily service is Zhuhong’s 袾宏 revision of the anonymous

Zhujing risong 诸经日诵 (

Various Sūtras for Daily Recitation) printed in 1600 in the Ming dynasty. The chant for Weituo was present in Zhuhong’s version of the text (J19:B044.177c–178a). Examining the authorship of the individual liturgical contents, Chen Pi-yen has argued that the liturgy should have been completed by the twelfth century or at least by the Song dynasty (

Chen 1999, pp. 10–14).

Besides mornings and evenings, Chan monasteries also have other types of sutra-chanting rituals, called Fengjing 讽经 (or “chanting text”), for different times and occasions. Although the date of its origin is unclear, it is common practice that from the first day to the seventh and from the sixteenth to the twenty-first day of a month, there are six

fengjing rites dedicated to the earth god, linear masters, Huode Xingjun 火德星君, Weituo, Puan 普庵, and Zhenshou 镇守 respectively to appreciate their protection. These are the Six Fengjing (

liu fengjing 六讽经) (

Ding 1984, 326b, 1356d). Weituo

fengjing is one of the six. That is, on two fixed days every month, the fifth and nineteenth, monks practice Weituotian Fengjing 韦驮天讽经, or the texts-reciting ritual to Weituo. The Chan school in medieval China is more representative of the diffusion of Chinese religious practices than an exclusive sect. The monastic rules established by the Chan school were widely accepted among Chinese Buddhist communities during the Song and Yuan dynasties, when Chan was the most popular form of Buddhism and received approval of the state (

Johnston 2013, p. 269).

Such practice was even transmitted to Japan. For instance, in

Keizan’s Rules of Purity (

Keizan shingi 莹山清规) written by Keizan Jōkin 莹山绍瑾 in 1324, Weituotian Fengjing is mentioned as being performed on the third day every month after the morning recitation rite—in front of the image of Weituo, chanting the

Hear Sutra and

dhāraṇis to eliminate all disasters.

12 It is likely that Keizan modeled his text on similar works imported from Yuan dynasty China. The date of this Japanese text indicates that the practice of the Weituotian Fengjing was probably already quite common in China by the Yuan.

Celebrating the birthday of Weituo annually is still among the basic birthday celebration rites of Buddhist temples in China to the present day. In the

Baizhang qinggui zhengyi ji 百丈清规证义记 (

Baizhang’s Pure Rules for Large Chan Monasteries with Orthodox Commentary) published by Yirun in 1823, Weituo’s birthday is listed as one of the important days for regular annual ceremony (X63:1244.391c). On the birthday of Weituo, the third of June of the lunar calendar, special offerings are made to the image or tablet of Weituo, unless it is a small temple in which such celebrations are ignored. There are a number of various annual birthday celebration rituals in Chinese Buddhist temple practice and laymen usually actively participate in them. However, Weituo’s birth is only celebrated within the

saṅgha (

Welch 1967, p. 109).

In addition to the routine of daily, monthly, and annual rites, Weituo is specially worshiped in the rituals associated with meditation retreat, xiaanju 夏安居, because Weituo, according to Daoxuan, protects monks from demons during meditation. The summer meditation retreat, xiaanju, called varṣā in Sanskrit, can be traced back to Śākyamuni’s time—a three-month meditation retreat during the monsoon season. Chinese monastic rules made from the Yuan dynasty (1206–1368) and beyond began to include liturgical programs in which Weituo became increasingly important. Since the Yuan dynasty, invoking Weituo in the beginning and ending ceremony of the summer meditation retreat has become common in monastic rules such as in the Zengxiu jiaoyuan qinggui 增修教苑清规 (Extended Pure Rules for Teaching Cloisters) (1347) of the Tiantai 天台School edited by Ziqing 自庆 (X57:968.327ab. 338a). This tradition was followed in temple rules written in the Ming and Qing periods, e.g., in the Chanlin shu yu kaozheng 禪林疏語考證 (X63:1251.672c) written by Yuanxian (1578–1657) of the Chan School and the Jiemo yishi 羯磨儀式 “Karma-vācanā Rite” (X60:1135.757c) written by Shuyu (1699) of the Pure-land school.

In fact, worshipping Weituo was extensively involved in various aspects of monastic life in China in the past, way beyond these most basic regular rites discussed above. Temple rules written in the Ming and Qing dynasties include more liturgical content than earlier eras, and more Weituo-related rites are recorded. As part of the wave of reviving Buddhism in the late Ming and early Qing period, a number of monastic regulations were published to rejuvenate the

saṅgha and reestablish order. In the texts of this time, it is common that Weituo is called upon in various monastic ritual ceremonies. In the

Jingtu ziliang quanji 淨土資糧全集, the practitioner is required to make veneration to Weituo and call upon him for his compassion and witness a number of times (X61:n1162.576ab, 579c, 580a, 581c, 582a, 583a, 585ab, 586b, and 587ab). The

Baizhang qinggui zhengyi ji ji 百丈清規證義記 (

Baizhang’s Pure Rules for Large Chan Monasteries with Orthodox Commentary) of the late Qing dynasty represents a summit of the compilation of monastic rules in China. This most detailed and comprehensive

vinaya reflects the Chinese Buddhist practice in general instead of the Chan sect, as the title suggests. This text proclaims that Weituo will never fail to answer a prayer to eliminate any catastrophe of the Buddhist monastery.

13 Whenever the

saṅgha is running out of food and encounters famine, or there is a plan for temple construction or reconstruction, a special date is to be chosen to perform the rite of praying to Weituo.

14Weituo’s functions in China were well expressed in these liturgies as early as the Yuan dynasty. The aforementioned

Zengxiu jiaoyuan qinggui includes a passage called

Weituo qian huixiang 韦天前回向, the standard dedication in front of the Weituo image. The prayer in this dedication demonstrates everything that the Chinese monks expect from Weituo—“consolidating and pacifying the Mountain Gate”, “making the warehouse abundant”, “ensuring the monks have the right thoughts and eliminating their obstacles”, and “beautifying the Buddhist temple”.

15 These expressions primarily cover three aspects. First, keep all kinds of disturbance outside the temple gate to safeguard the peaceful life inside. Second, at the material level, ensure that the monastic community receives abundant supplies for both the monks’ daily use and temple construction and decoration. Third, at the spiritual level, help the monks to fix their minds on the right thoughts and protect them in their spiritual practice.

Various rites on Weituo in Chinese Buddhist temples recorded in the temple regulations from the Yuan period in the above discussions mainly concern these three aspects. For example, in the monthly texts-reciting ritual to Weituo described in the Japanese Keizan’s Rules of Purity, Weituo was also worshipped as a guardian of the warehouse and kitchen (T 82:2589.423). In the Huanzhu An qinggui 幻住庵清規 (Pure Rules for Huanzhu An) (1317) of the Yuan dynasty, Weituo is also addressed as kusi 库司, or storage keeper. The Huanzhu an qinggui was designed solely for a private temple called Huanzhu An 幻住庵, or “Mirage Hermitage”, by Zhongfeng Mingben 中峰明本 (1263–1323), who belonged to the Yangqi sect of the Linji 临济 School, a dominant Chan sect of that time. Weituo, as well as many other protective deities related to the temple, is invited for the New Year ritual for protection and prosperity (X63:1248.578bc). Since Weituo can ensure the supply of members of the saṅgha, entitling him as the storage keeper of supplies sounds logical.

These three functions of Weituo are also reflected in the numerous efficacious stories about Weituo. In fact, most of these stories are associated with

saṅgha.

16 Such stories were already present as early as the Tang dynasty. Huaixin’s 怀信 (ninth century)

Shimen zi jing lu 释门自镜录 recorded quite a number of efficacious stories about Weituo of the Tang dynasty (T51: 2083.818a). Those stories, in turn, reinforced the worship of Weituo.

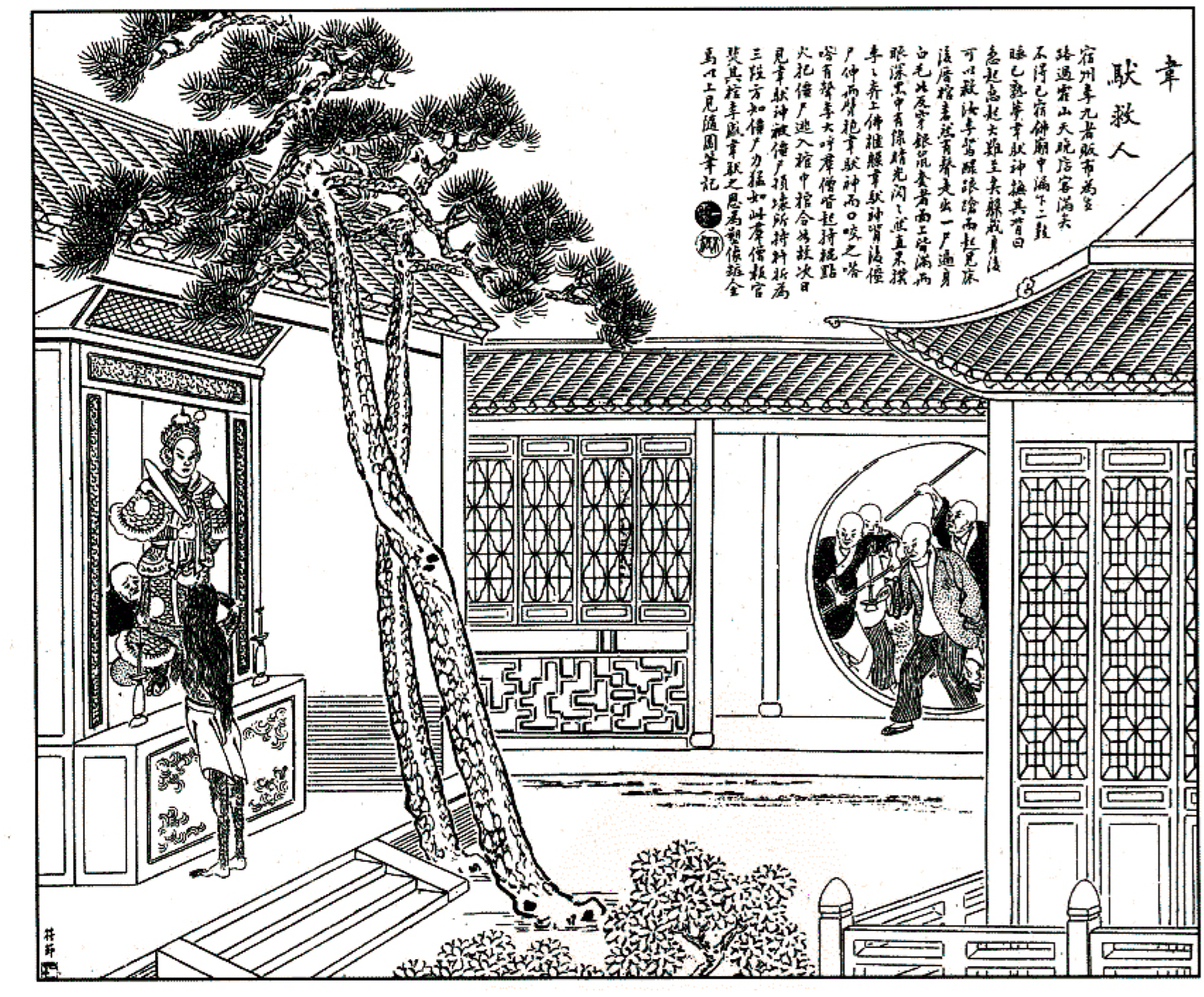

An example of the first function, keeping all kinds of disturbance outside the temple gates, can be seen in the Dianshizhai

Pictorial 點石齋畫報, China’s earliest popular news pictorial published in Shanghai in

1884–1898, during the later days of the Qing dynasty, as an illustrated supplement of the Shen Bao newspaper.

17 Figure 3 shows the event, “Weituo Saving a Person”: A merchant called Li Jiu stayed in a temple in Huoshan Mountain overnight. He dreamt that Weituo urged him to wake up because a calamity was coming and instructed him to hide behind him. Li woke up and saw a zombie chasing him. He ran to hide behind the Weituo statue. The noise woke up the monks who came and chased the zombie away.

To thank and honor Weituo, Li had the Weituo statue gilded. Such legends of Weituo are abundant. Presented as news in a modern medium, the report in the Dianshizhai Pictorial demonstrates the continued presence of belief in Weituo in contemporary times.As to the second function, ensuring that the monastic community receives abundant supplies, Weituo is often worshipped in the saṅgha as a provider of various things. In one type of miracle story, Weituo provides food or other help to monks in desperate situations. There is a saying—“Weituo can urge people to make offerings”, called Weituo gan gong 韦驮赶供. For example, according to the Miyun canshi yulu 密云禅师语录 [Quotations from Can Master Miyun] (1645) compiled by Tongqi 通奇, when Chan master Miyun 密云 (1566–1642) and his temple ran out of food, local devotees brought them offerings just in time because Weituo sent them messages through dreams (J10:A158.81b).

For the third function, helping the monks to fix their minds on the right thoughts and protecting them in their spiritual practice, there is a well-known story from Mt. Tianmu which became a sacred mountain of Weituo in the Song dynasty, because Weituo manifested there. In China, there are four sacred mountains, or the

bodhimaṇḍa, “a place used as a seat, where the essence of enlightenment is present”, dedicated to the four most popular Bodhisattvas, respectively. This is the only one for a protective deity with an Indian precursor. Efficacious stories of Weituo in the area are especially copious. A story about Chan master Gaofeng Yuanmiao 高峰原妙 (1238–1295) of the Southern Song dynasty became quite popular through Xuanhua Shangren 宣化上人 (1918–1995). Gaofeng Yuanmiao belonged to the Yangqi 杨岐 sect of the Linji 临济 School of the Chan tradition. He used to fall asleep during meditation. To solve this problem, he decided to meditate on an overhanging rock on the western peak of the Tianmu Mountain so that he would fall off the cliff if he dozed off. He fell off the mountain twice, and twice he was saved by Weituo. In his persistent effort, Gaofeng made tremendous progress in the end (

Xuanhua Shangren 1968). Helping monks with their safety and with overcoming obstacles in their spiritual journey, especially during meditation, are the primary duties of Weituo.

In sum, the worship of Weituo in the saṅgha became increasingly institutionalized in China until the end of the dynastic periods. With the functions of Weituo given by the Chinese monks and the proliferation of Weituo’s legends, it is not surprising that images of Weituo were set up for worship in Buddhist temples in China, and that they were placed in specific locations in the iconographic plan of a temple.

3. The Independent Weituo Statue in the Temple Complex

In Chinese Buddhist temples, a Weituo image can be an independent statue on an altar for worship, or just an attendant to another main figure. This paper is concerned with the former, when a Weituo image is an independent statue on an altar to receive worship. The most common location of this independent Weituo statue in a standard Chinese Buddhist temple complex is the entrance hall of the Heavenly Kings. Although, his statue can also be enshrined in a number of other places, such as the Weituo Hall, the meditation cloister, and in the kitchen. These images and their locations in the temple space materialize the expression of Weituo worship in the saṅgha.

The hall of the Heavenly Kings is the main place for Weituo images in a temple. This hall, which also serves as the entrance hall, came into existence in the iconographic plan of a Chinese Buddhist temple in the Song dynasty (

Ho 1998, pp. 127–37). Before the Song dynasty, the Heavenly King images were placed on the main altar with the Buddha or at the doorway. It is believed that the Weituo image was also set up in the hall of the Heavenly Kings during the Song dynasty (

Zhou [1991] 2007, p. 3). For instance, the Weituo image (

Figure 4) in the Heavenly Kings Hall in Lingyin Si is said to be dated from the Southern Song period (1127–1279) (

Xingen n.d., chp. 6;

Lin 2003, p. 31). In the iconographic program of this Heavenly Kings Hall, the four kings are placed on the two sides; the future Buddha Maitreya is enshrined in the center; and the statue of Weituo is always set at the back of Maitreya facing inward to the temple compound. In the identity of Weituo as established in China, he is a general under the Southern Heavenly King and the head of all the thirty-two generals under the four Heavenly Kings. Thus, the Heavenly Kings Hall is actually his logical and proper location. Facing inward is also significant. It indicates his duties of overseeing the community inside while guarding the gateway. This placement manifests Weituo’s role as the protector of the

saṅgha.

18In hall of the Heavenly Kings, Weituo is normally represented as standing in two postures, holding the

vajra mallet horizontally on his two arms with the two hands in the

añjali mudra (

Figure 5), or letting the

vajra mallet stand on the ground with one hand pressing on top of the mallet (

Figure 4). The former is said to indicate that the monastery provides accommodation to monks from other temples, while the latter indicates the opposite (

Z. Liang 1983, p. 128). To what extent the Weituo image was used to show the visitors a monastery policy in the past is not clear. However, the fact that it is the Weituo statue, not other statues, that is used to display whether a temple accepts visiting monks is quite meaningful because of Weituo’s close ties to the Chinese

saṅgha. Occasionally, the posture of holding the weapon in one arm also appears, e.g., the Weituo statue in the Heavenly Kings Hall in the White Horse Temple (

Baimasi Hanwei Gucheng Wenwu Guanlisuo 1980, p. 7).

Before placing the Weituo statue in the Heavenly Kings’ Hall became standard, the statue of Weituo would have been set up in front of the Buddha image in the main hall or enshrined in an independent Weituo Hall. These traditions were continued in some temples later on. For instance, the earliest extant Weituo statue in Foguang Si was placed in the central platform in the main Buddha hall. Here, Weituo is a seated image placed in the front-left of the Buddha.

The Weituo image on an altar can be a seated sculpture. The

Jiemo yishi 羯磨仪式 (1699) written by Shuyu 书玉, a ritual text of the Qing dynasty, describes how to arrange the altar for the rite of the summer meditation retreat. It is the same arrangement; the Śākyamuni image should be placed in the center and the Weituo image to the front-left of the Buddha (X60: 1135.757c). In the main Buddha hall in the Linshan Si 灵山寺 in Xinyang County, the Kaiyuan Si 开元寺 in Zhengzhou, and the Baima Si 白马寺 (

Figure 5) in Luoyang, Weituo is a life-sized statue (of the Ming dynasty) standing in the front-left of the Buddha statues (

Lu 2003, p. 546;

Zhengzhoushi Difangzhi Bianchuan Weiyuanhui 1986, p. 73;

Meng 2004, p. 175).

Examples of an independent Weituo Hall in a Buddhist temple are not uncommon.

Figure 6 shows the ground plan of the Guangsheng Xiasi 广胜下寺 (Lower Temple of Guangsheng) of the Yuan dynasty (ca.1264 and 1294). In this temple, the Weituo Hall, no. 6 in the ground plan, is a side hall in the front-right of the main Buddha hall. The

Jinling fancha zhi 金陵梵剎志 (

Record of Buddhist Temples at Jinling) records all the Buddhist temples in Nanjing of the Ming dynasty. For all the temples listed, eleven monasteries have a Weituo Hall, among which, six are small temples with the Weituo Hall as the entrance hall

19 and five of them have a Weituo Hall in addition to the Heavenly Kings Hall. In Faqing Yuan 法庆院, the Weituo Hall is the side hall on the left (

Ge 1936, p. 719). In four temples, the Weituo Hall is located in the Chan Cloister (Chantang 禅堂).

20 In the Linggu Si 灵谷寺, besides the Chan cloister, there is another Weituo Hall built in the Vinaya Cloister (Lütang 律堂) (

Ge 1936, p. 303). The Chan Cloister and Vinaya Cloister are related to the Chan meditation practice and

vinaya. Both of them are attached to the function of Weituo. Locations either in the Chan Cloister or Vinaya Cloister speak of Weituo’s duty as a patron deity of the

saṅgha.

The Weituo Hall or the space in front of the main Weituo image of a temple also serves for the rituals related to Weituo. In the aforementioned

Baizhang qinggui zhengyi ji ji of the late Qing period, the rites, which should be performed when a temple is running out of food or there is a need for temple construction/reconstruction, are clearly specified to be held in either the main hall or the Weituo Hall.

21Indeed, the altar of the Weitu constitutes an organic part of monastic life. Based on mainly oral information from abbots of major monasteries in China, Holmes Welch presented a detailed description of the modern practice in Chinese Buddhist monasteries of the first half of the twentieth century before the practice was discontinued in the PRC period. In the experience of one monk, who, according to Holmes Welch, seems to have been exposed to a different system of novitiate altogether, he, with about twenty novices from nearby small temples, had his head shaved before the image of Weituo in a large hereditary temple in a collective ceremony, with

each master shaving his own disciples (

Welch 1967, p. 284).

Today, monks in the well-known temple Guiyuan Si 归元寺 in Wuhan had a unique tradition. The selection of the abbot of this temple was decided by drawing lots in front of the Weituo statue. As described by Welch, this is in fact a tradition of the Hunan province, with its roots conceivably lying in India (

Welch 1967, pp. 166–70).

Furthermore, in Chan temples in the past, the administrative notices were announced through hanging a tablet, called

painshi 牌示. The tablet would be hung up in different locations according to the nature of the announcement. Shown in the

Gaominsi siliao guiyue 高旻寺四寮规约, for rituals, the tablet should be hung in front of the main hall, whereas for the promotion of monks such as

shengzuo 升座 and

mianli 免礼, the tablet is to be hung in front of the Weituo Hall (

Ciyi 1989, p. 5818). Located in Yangzhou, the Gaomin Si 高旻寺 temple is one of the four most important Chan temples in China. The monastic rules of this temple, written by master Laiguolao 来果老 in the early modern time, are a synthesis and modification of the long tradition of Buddhist practice in China.

Head shaving marks one’s monkhood, and the other examples all concern important personnel issues of the

saṅgha. In addition, Welch also observed another use of the Weituo Hall that is rarely known. During the meditation period, when a monk has a minor illness, the precentor would excuse him from a certain number of meditation sections and let him spend the day resting in the hall of Weituo (

Welch 1967, p. 79). What would a better place than the Weituo Hall when a monk is seeking protection?

Weituo images can also be enshrined in the kitchens of Chan monasteries (

Ciyi 1989, p. 2701). Jiexian 戒显 (1644–1672), in his

Xianguo suilu 现果随录, mentioned a Weituo image in the kitchen of the Anguo Si 安国寺 which was built in the Southern Tang dynasty (937–976). This was a seated statue.

22 Placing a Weituo shrine in the kitchen reflects his role of ensuring the food supply for the

saṅgha. This tradition of enshrining Weituo in the kitchen was also transmitted into Japan.