“Buddhist-Christian Style”: The Collaboration of Prip-Møller and Reichelt—From Longchang Si to Tao Fong Shan Christian Centre

Abstract

1. Introduction

“Church architecture stands as a testament to the modern cultural, economic, and political exchanges and integration between East and West”.

- (1)

- The “Chinese roof with Western walls style (中西合璧)” featuring a combination of Chinese-style roofs and Western-style walls.

- (2)

- The “mixed Easten and Western façade style (装饰混杂)”, drawing inspiration from facade ornamentation details.

1.1. “Chinese Roof with Western Walls Style”

1.2. “Mixed Easten and Western Façade Style”

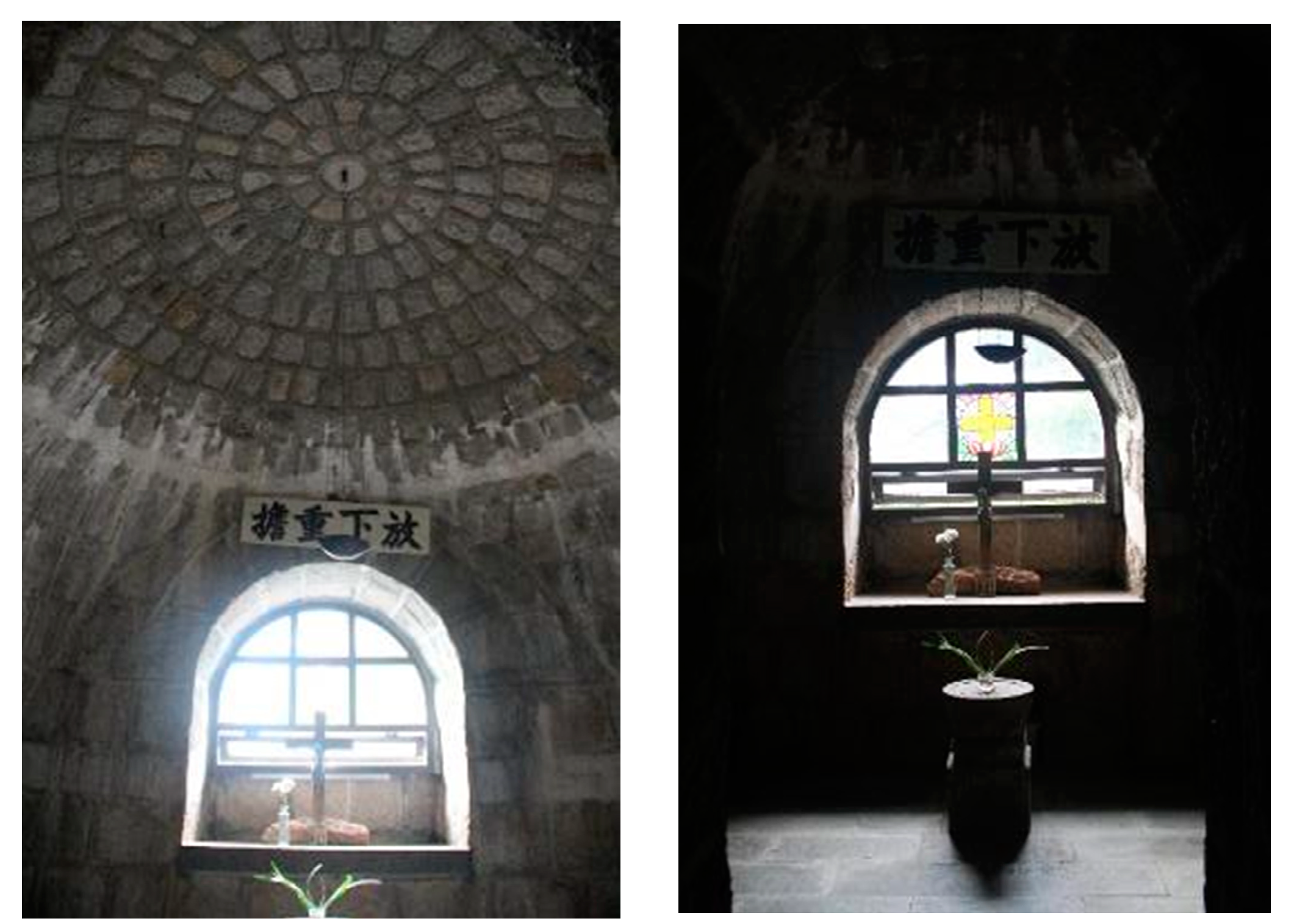

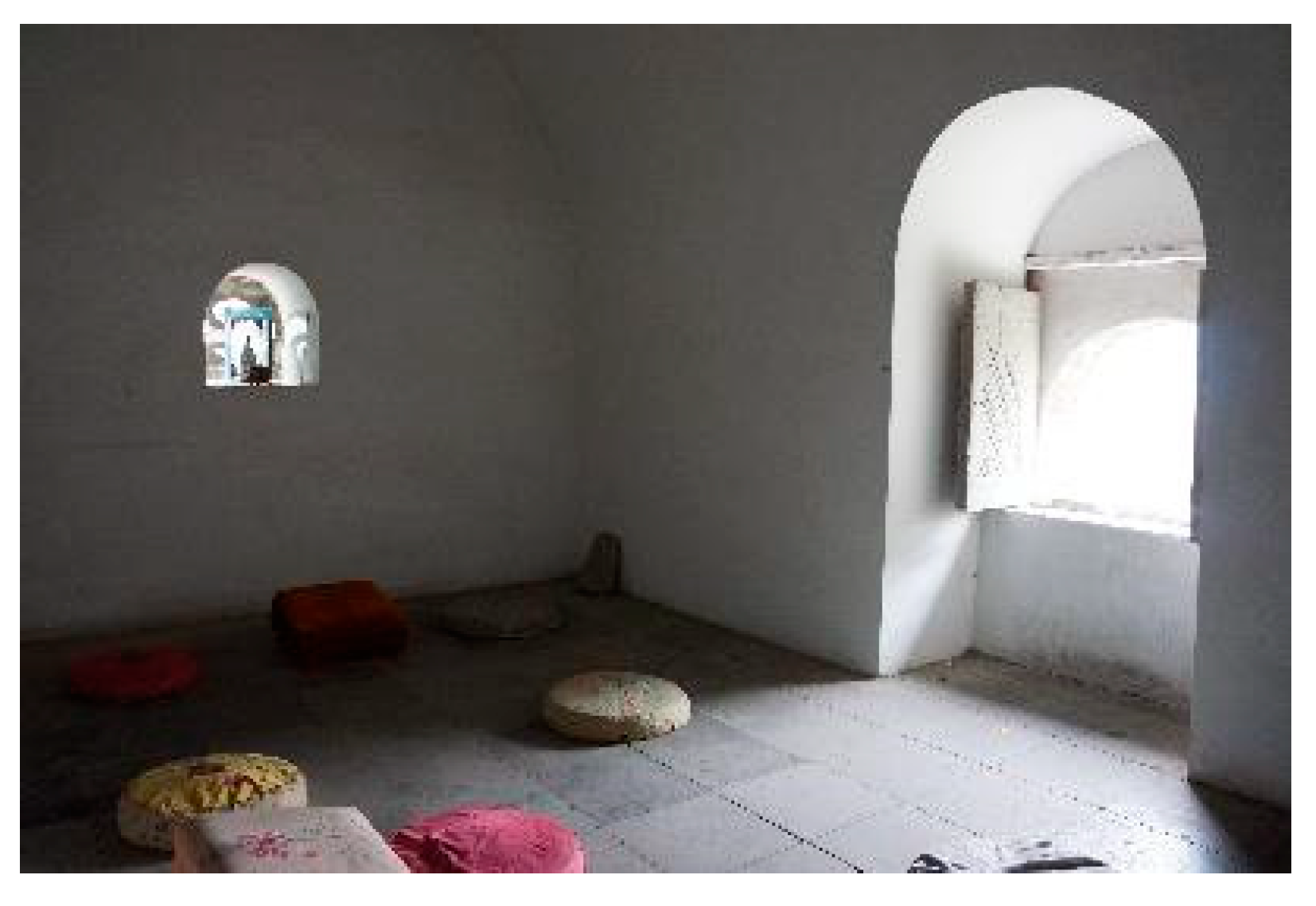

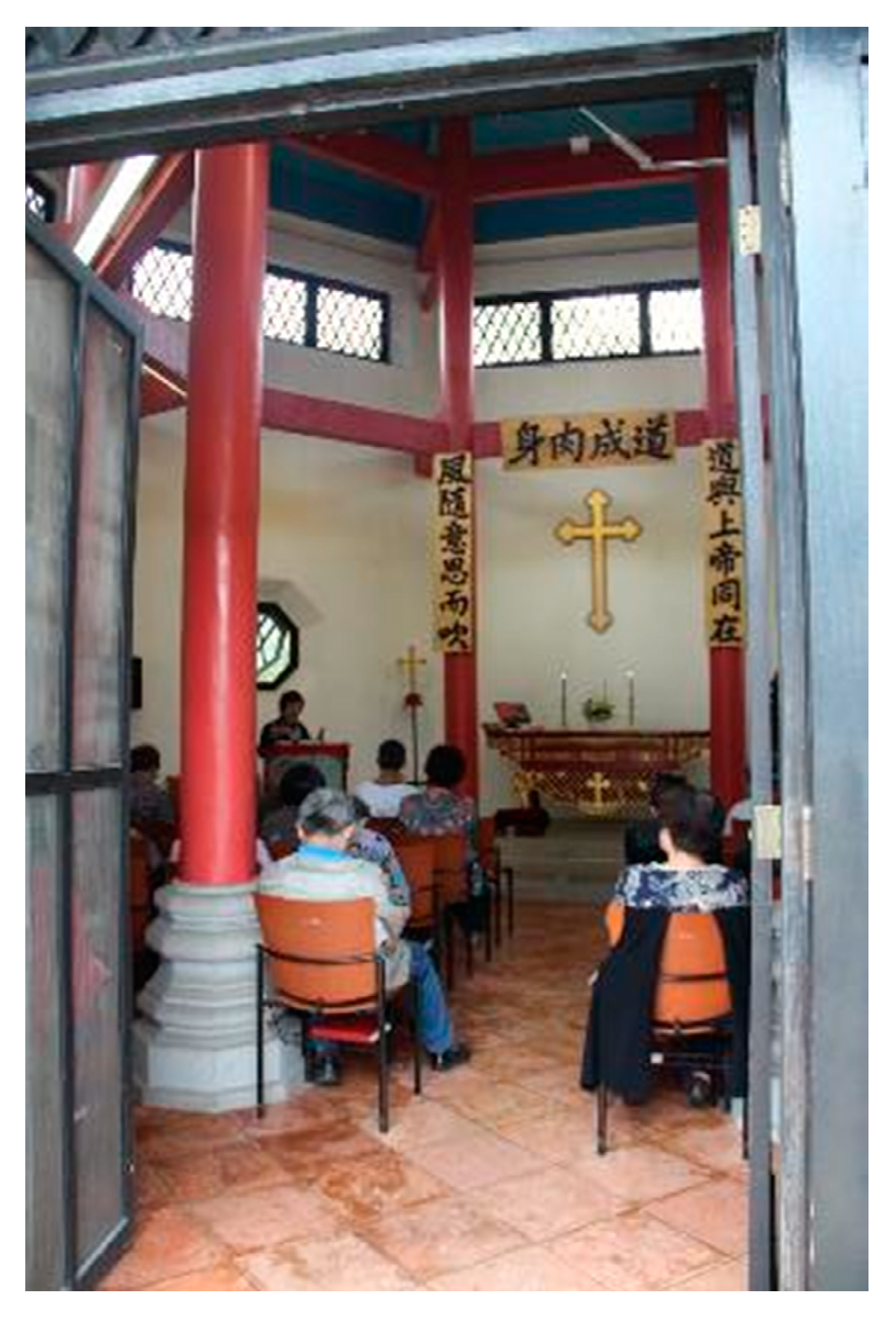

1.3. “Buddhist-Christian Style”

1.4. Research Methodology

- (1)

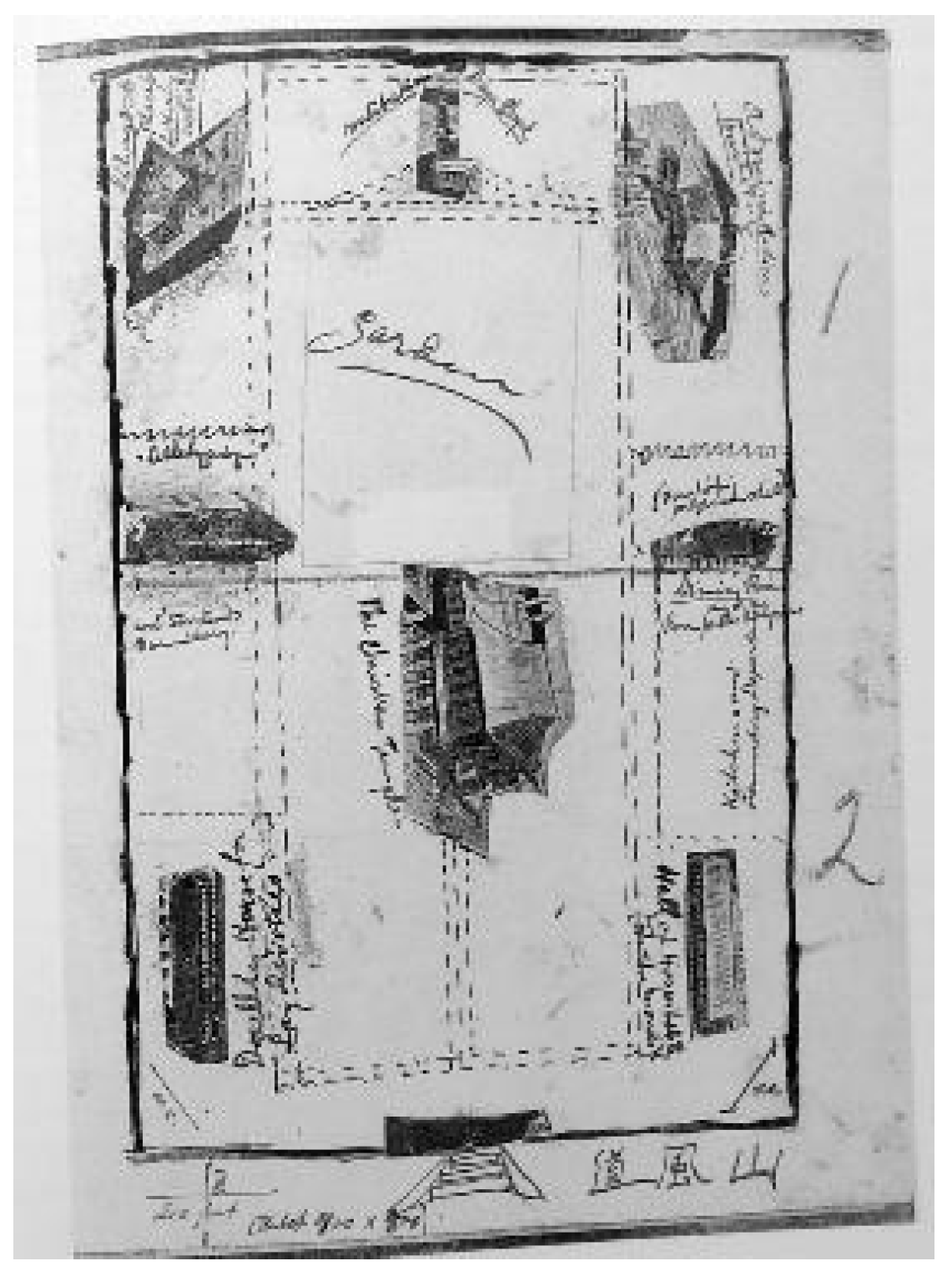

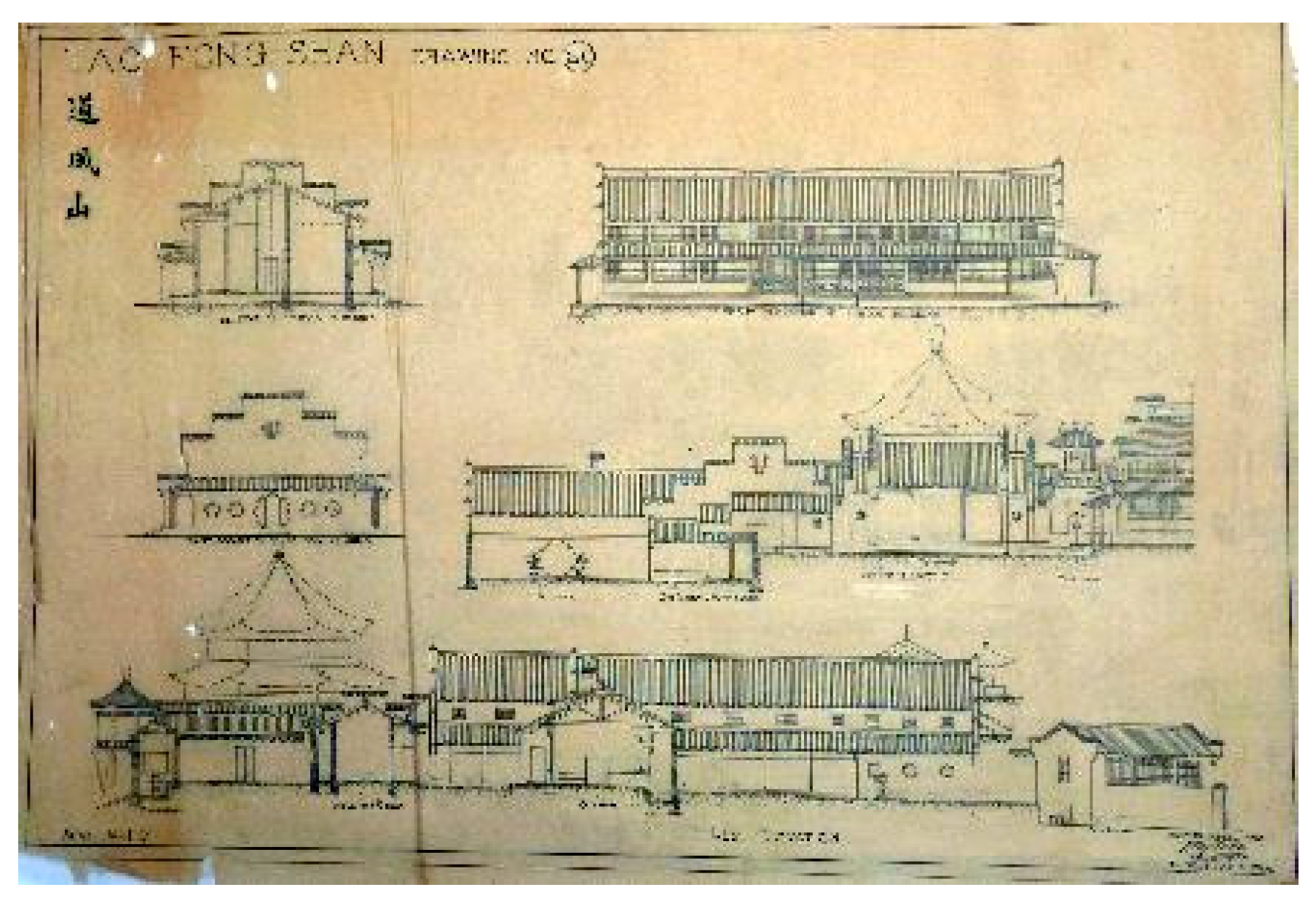

- Image analysis based on historical material: Exploring the understanding and cognition of Christianity towards Buddhism through traces revealed in the drawings, plans, photos, etc.

- (2)

- Anthropological field research: In an anthropological manner, conducting in-depth discussions on ritual studies and spatial field research methodologies at Tao Fong Shan and Longchang Si.

- (3)

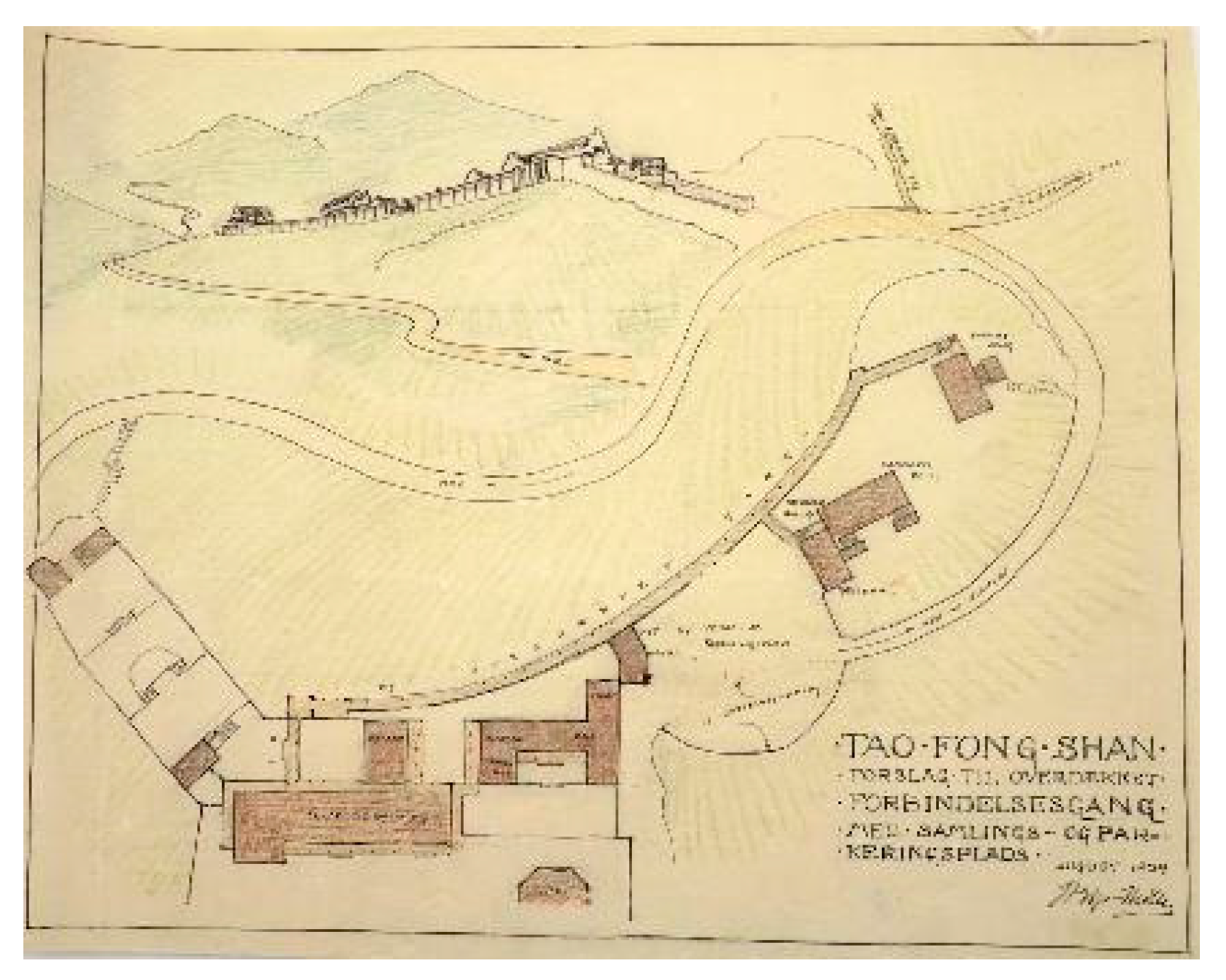

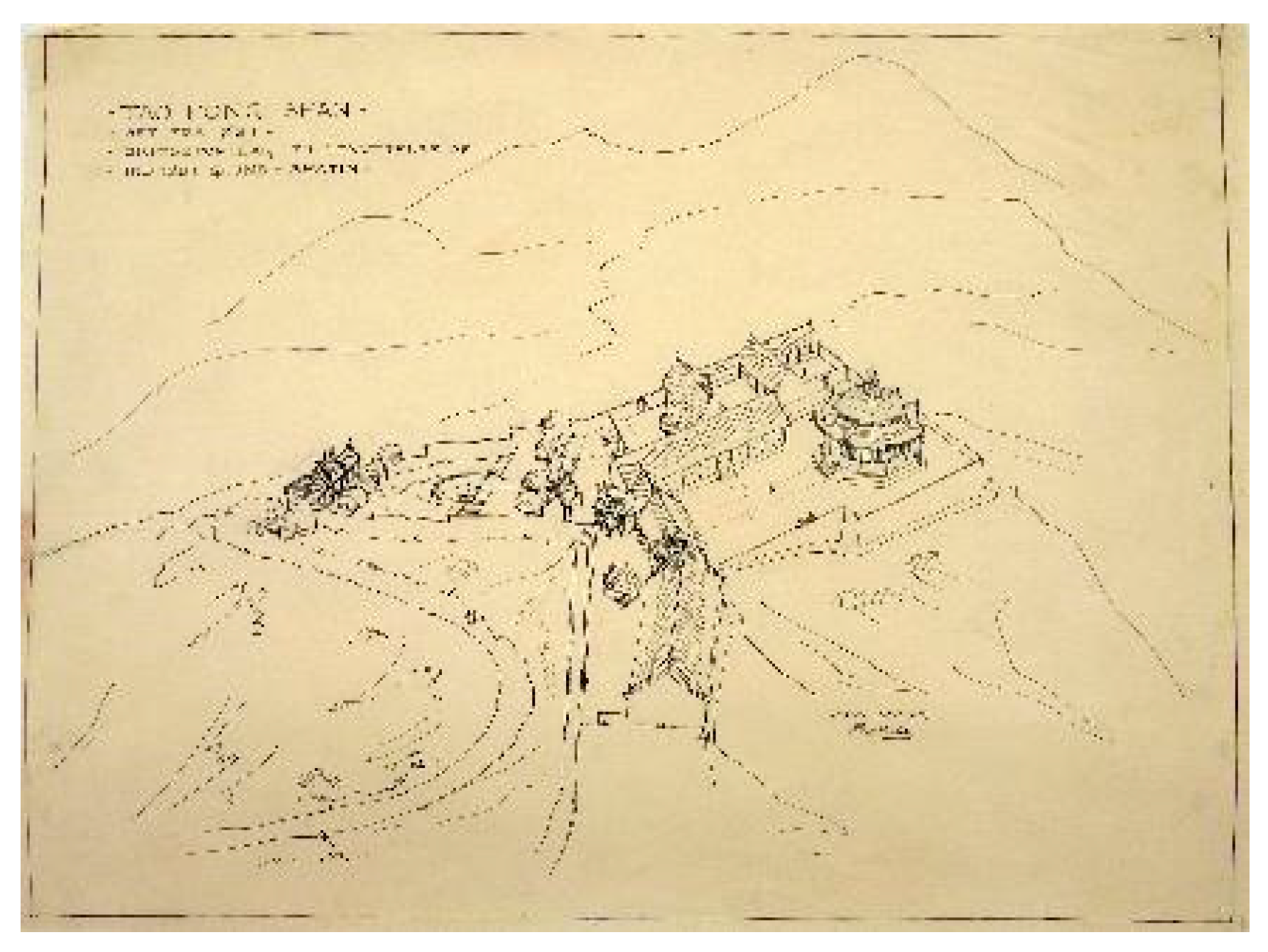

- Spatial comparative studies: Starting from site selection, layout, and architectural space design and experience, comparing the spatial imitation relationship between Tao Fong Shan and its main reference case, Longchang Si.

2. “Buddhist-Christian Style”: The Collaboration of Prip-Møller and Reichelt

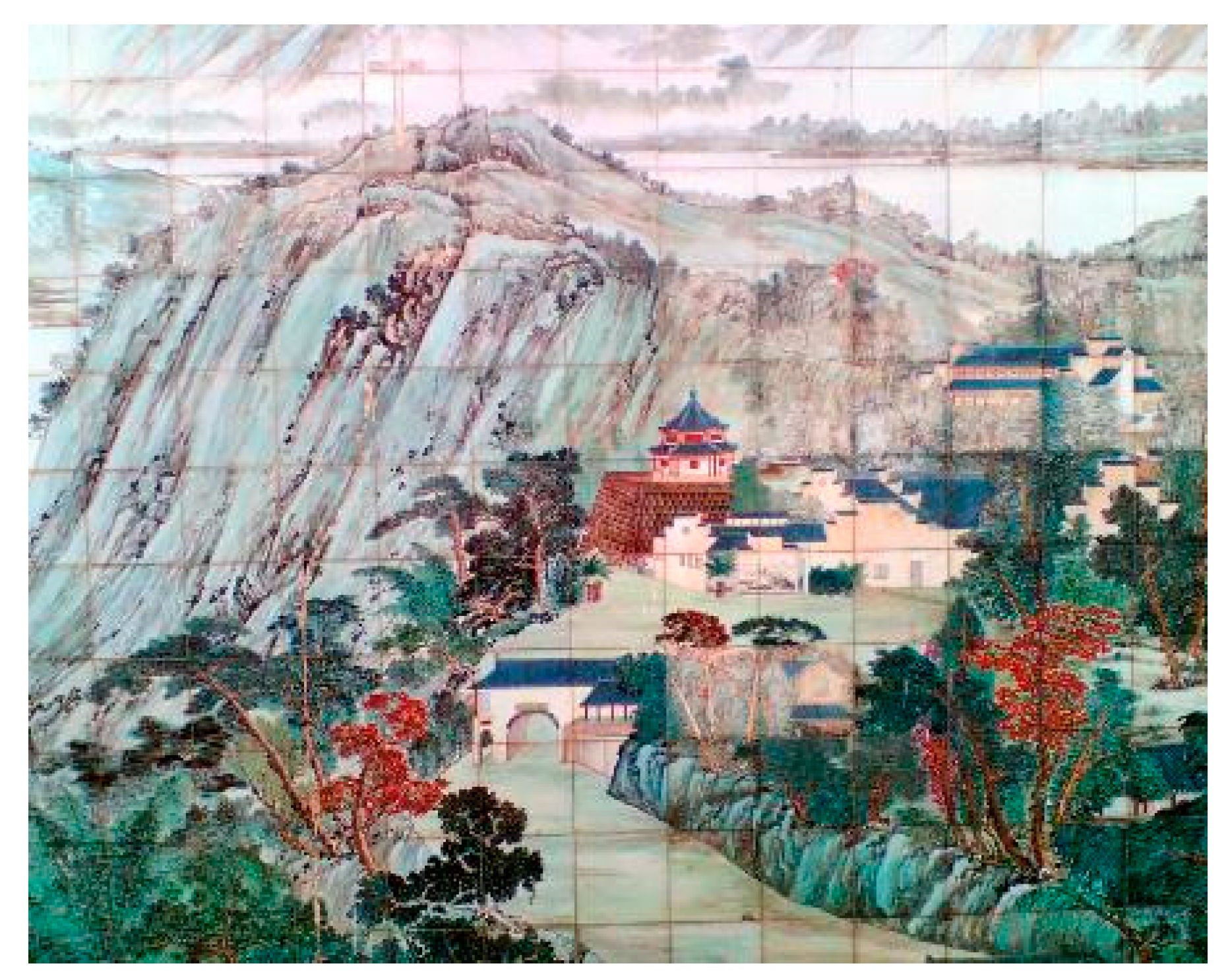

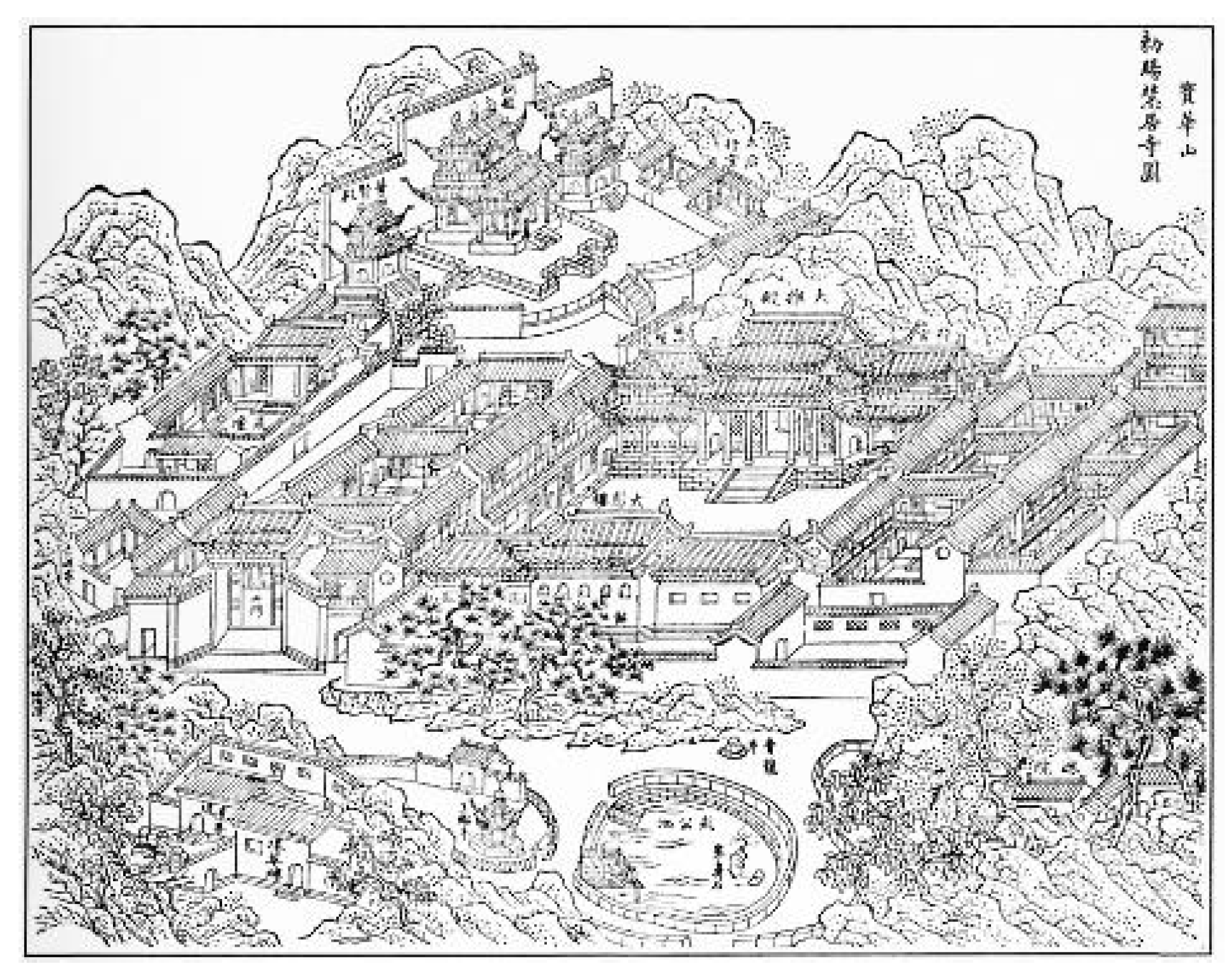

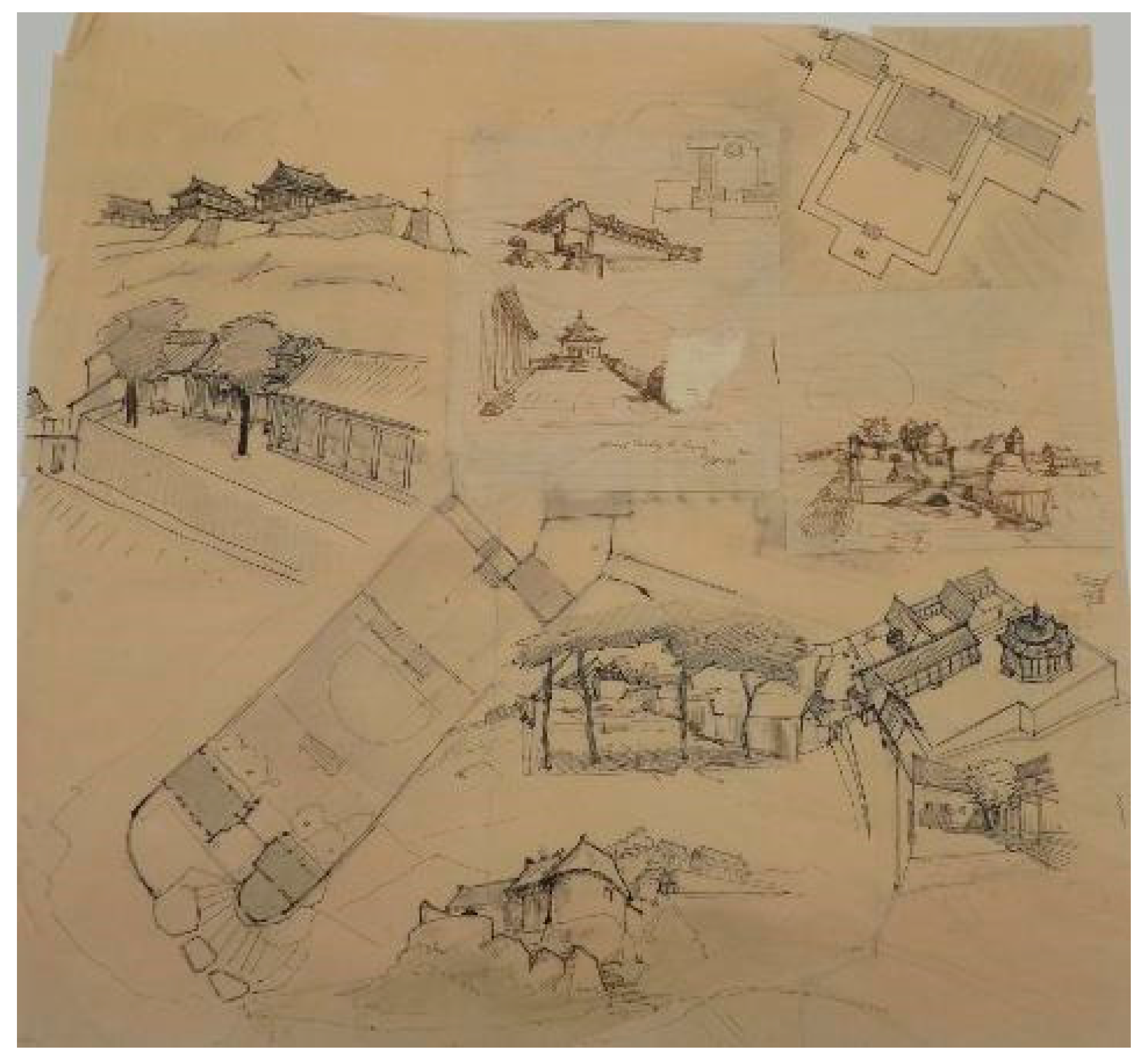

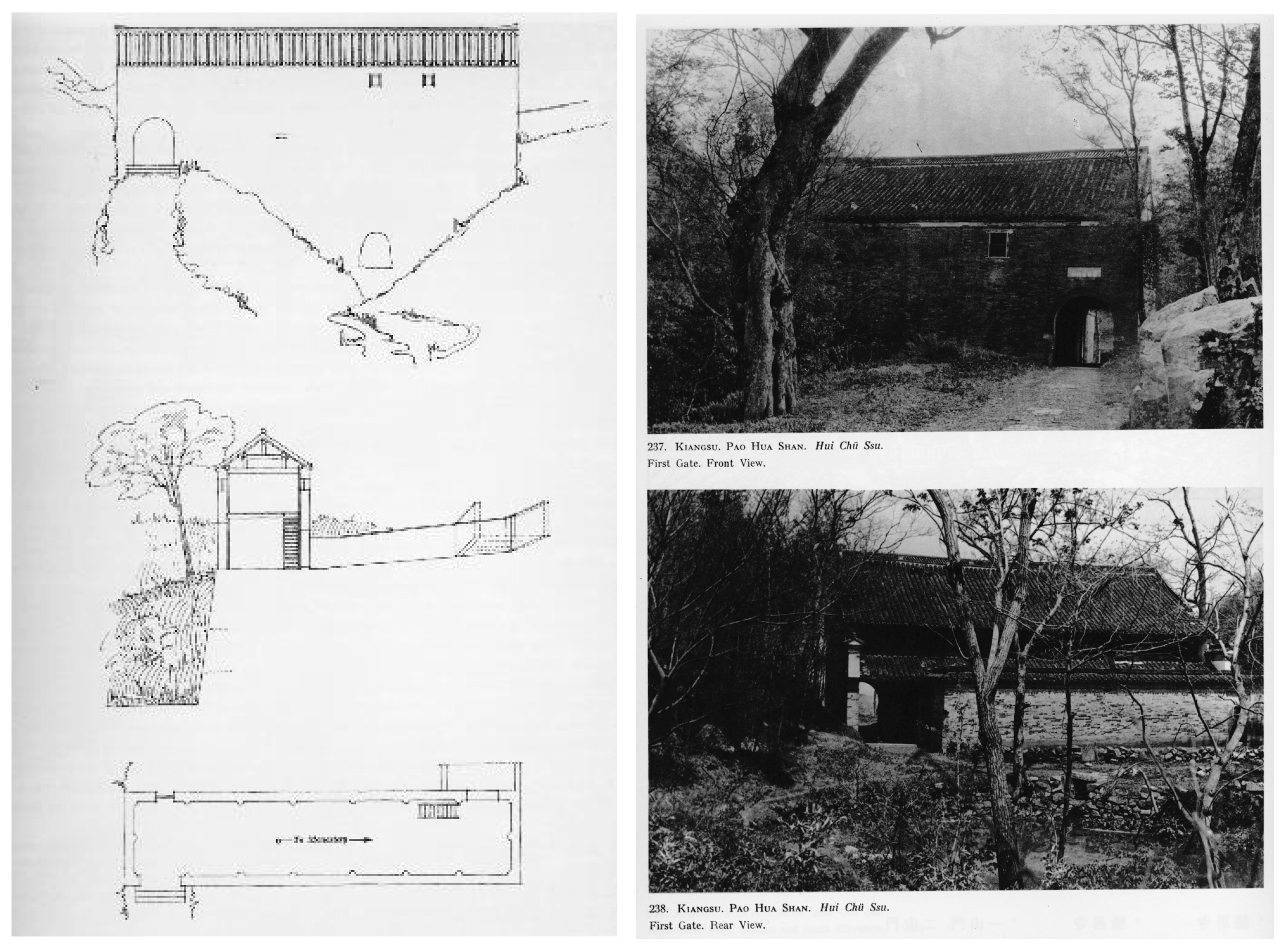

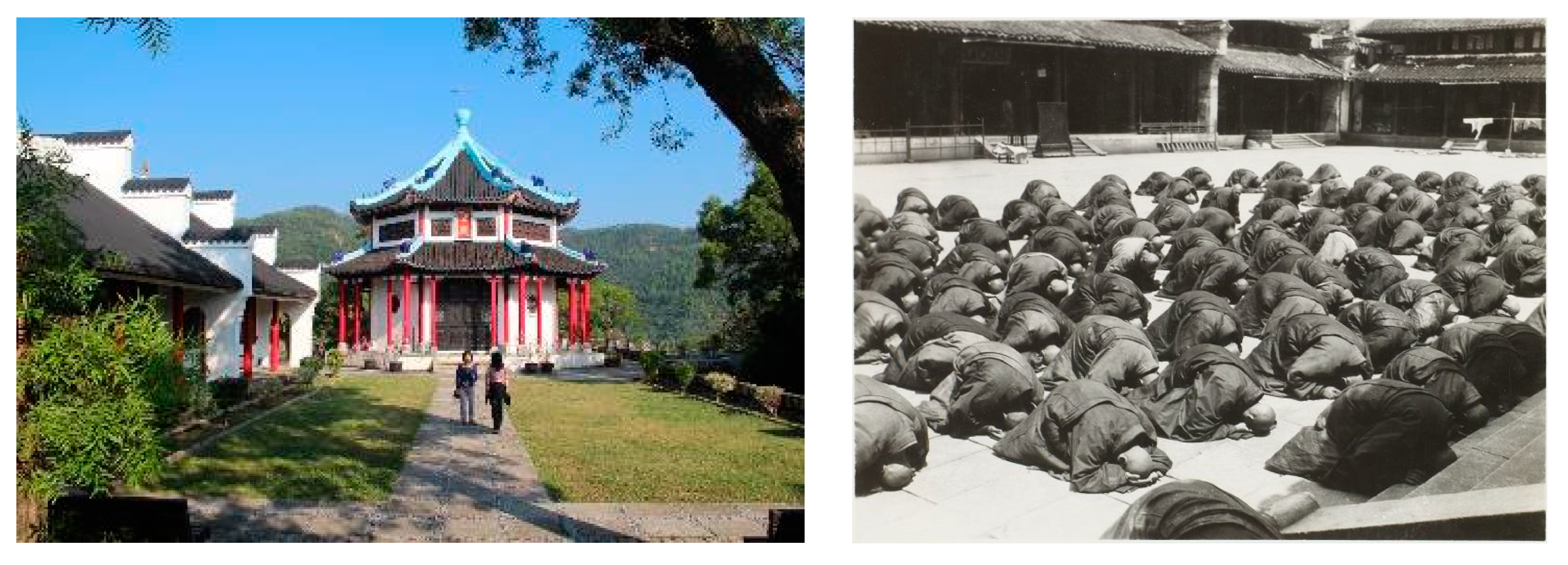

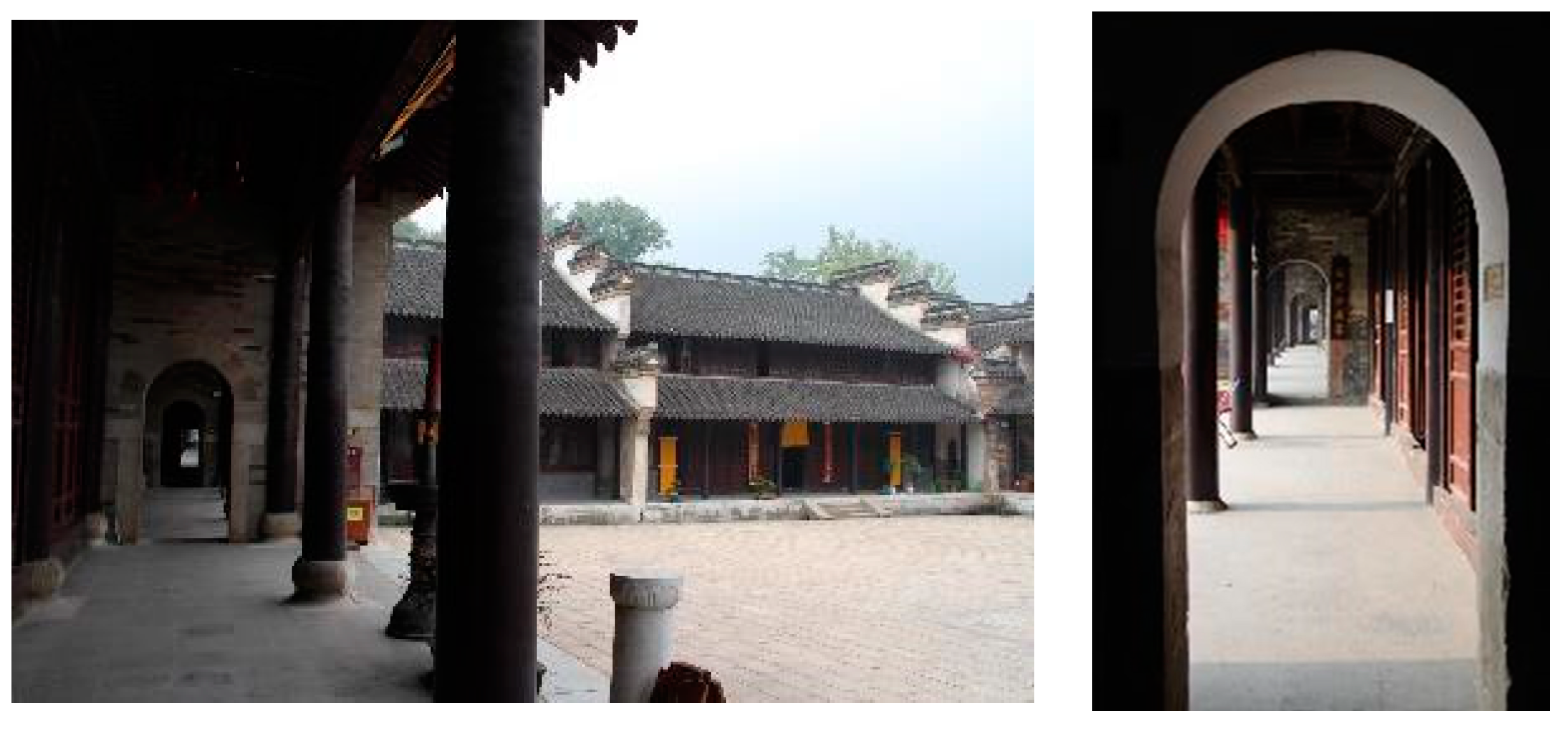

2.1. Prip-Møller and Longchang Si

2.2. Karl Ludvig Reichelt and His Buddhist Encounters

“Tao Fong Shan is still a small paradise on earth, created through the lifelong efforts of Karl Ludvig Reichelt with the brilliant assistance of architect Johannes Prip-Møller”.

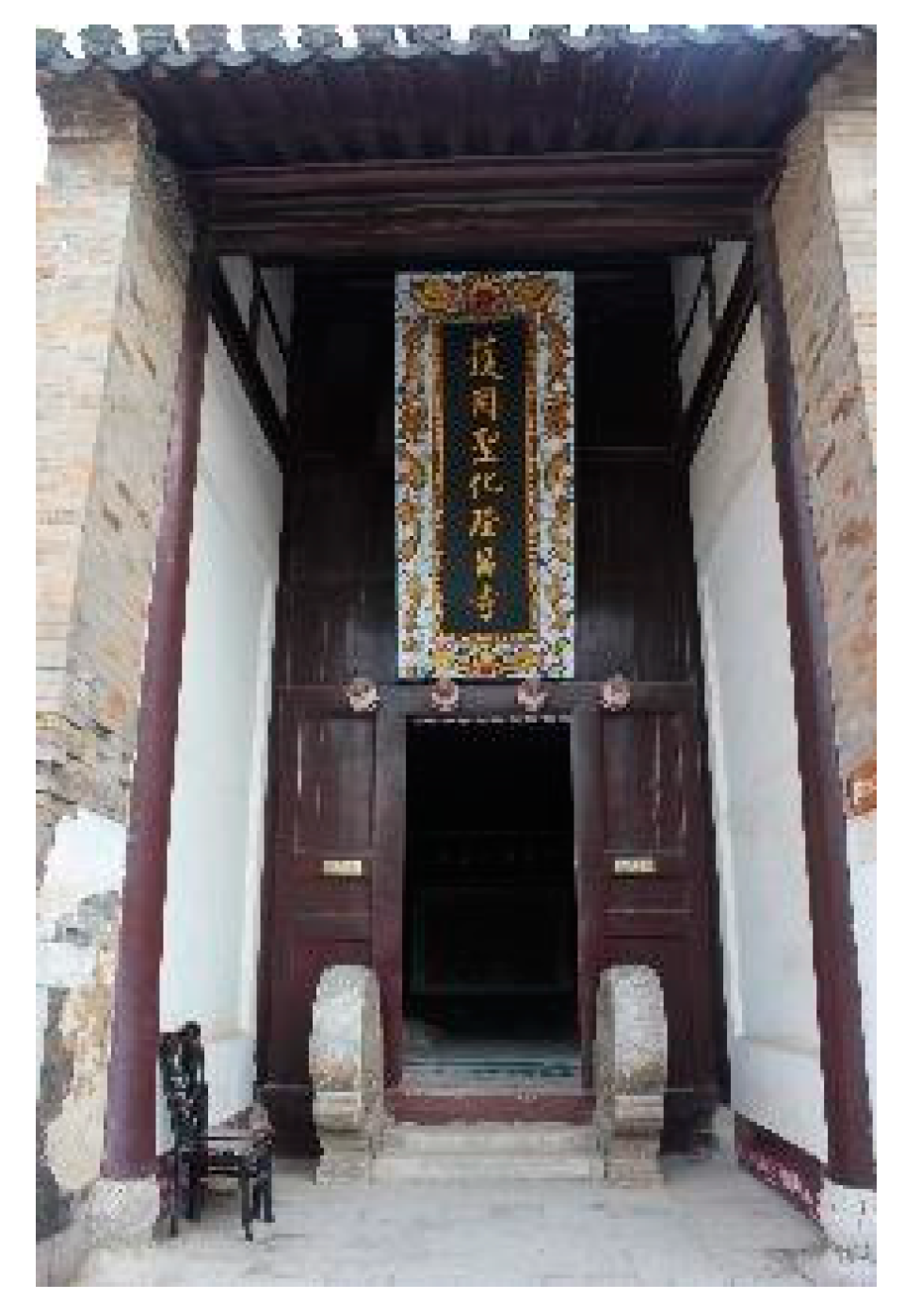

3. The Sinicization Construction of Christian Architecture: From Longchang Si to Tao Fong Shan Christian Centre

3.1. Site Selection

“Our architectural appearance must as closely as possible resemble the model of Chinese Buddhist temples. The purpose of this is to make visiting pilgrims feel at home and comfortable. Danish architect Johannes Prip-Møller’s plan for the Tao Fong Shan complex is also based on this principle, believing that it not only determines whether people can live comfortably inside the buildings but also signifies that the architecture aligns with the lifestyle within”.

3.2. Monastic Layout

3.3. Space Formation

4. Conclusions

“Every religion conveys its message through the language of art. Simultaneously, art undergoes transformation by religion in the process of fulfilling this task. Thus, religion and art always maintain an inseparable and organic connection in human culture”.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bai, Yin 白颖, and Tao Chen 陈涛. 2023. Space Formed by Bricks: The Beamless Hall of Linggu Monastery in Early Ming Dynasty 砖塑造的空间: 明初南京灵谷寺无梁殿研究. Architectural Journal 4: 102–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedict XV. 1919. Maximum Illud. Apostolic Letter. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xv/en/apost_letters/documents/hf_ben-xv_apl_19191130_maximum-illud.html (accessed on 16 May 2024).

- Boerschmann, Ernst. 1923. Baukunst und landschaft in China: Eine reise durch zwölf provinzen. Germany: E. Wasmuth a. g. [Google Scholar]

- Boerschmann, Ernst. 1982. Old China in Historic Photographs. New York: Dover Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Min 程旻. 2019. Chinese and Foreign Scholars and Institutions’ Survey of Ancient Archiecture in Zhejiang Province in the First Half of Twentieth Century and Related Issus Study 20 世纪上半叶中外学者和机构对浙江古建筑的调查及相关问题研究. Ph.D. dissertation, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Xiaochong 程枭翀. 2016. Interpretation on the View of Chinese Architecture of Modern Western Scholars from a “Non-Historical” Perspective 解读近代西方学者“非历史”视角下的中国建筑观. Ph.D. dissertation, Tianjin University, Tianjin, China. [Google Scholar]

- Chuta, Ito. 2014. History of Chinese Architecture. Changsha: Hunan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cody, Jeffrey W. 2021. Zhu ye Zhongguo: Hengli. K. Maofei de “shi ying xing jian zhu” (1914–1935) Building in China Henry K. Murphy’s “Adaptive Architecture”, 1914–1935, 1st ed. Translated by Wei Lu, and Tian Leng. Beijing: Wen hua fa zhan chu ban she. [Google Scholar]

- Coomans, Thomas 高曼士, and Jinze Cui 崔金泽. 2016. From Western-Christian to Sino-Christia: Architecture asTool of Inculturation in China, 1919–1939 从西式基督教到中式基督教风格——在中国推进本土文化适应中的建筑手段. Journal of Architectural History 38: 190–200. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Li 董黎. 1996. The Expression of Social Significance in Architectural Symbols: A Case Study of Church University Buildings in China 建筑符号的社会意义表达方式──以中国教会大学建筑为例. South Architecture 3: 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Faber, Tobias. 1994. A Danish Architect in China: Johannes Prip-Møller. Christian Mission to Buddhists. [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima, Ayako. 2018. A Comprehensive Survey of Catholic Churches in Hongkong: From the 1840s to the early 1940s 香港カトリック教会建築の悉皆調査: 1840年代–1940年代前半. AIJ Journal of Technology and Design 24: 1273–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fukushima, Ayako. 2019a. A Comprehensive Survey of Catholic Churches in Hongkong: From 1945 to 1955 香港カトリック教会建築の悉皆調査: 1945–1955年. AIJ Journal of Technology and Design 25: 467–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fukushima, Ayako. 2019b. Social and Political Factors in Induction of Catholic Churches in Hong Kong: Churches Established between 1956 and 1961. Nihon Kenchiku Gakkai Keikakukei Ronbunshū 84: 977–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, Ayako. 2020. Building St. Francis of Assisi Church and School in Hong Kong: Emergence of Church and School Complex in the 1950s. Nihon Kenchiku Gakkai Keikakukei Ronbunshū 85: 453–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Huanzhong 韩焕忠. 2015. Theological Interpretation and Sinicization of Christianity: A Comparison between Reichelt’s Mission in China and Buddhist Sinicization 神学格义与基督教的中国化: 从佛教中国化看艾香德的宣教实践. Journal of Comparative Scripture 2: 211–32. [Google Scholar]

- He, Qi 何琦. 2001. The Four Historical Periods of Indigenization of Christian Art in China 中国基督教艺术本色化的四个历史时期. Jinling Theological Review. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Guoliang 季国良. 2015. Architectural Activities and Spatial Characteristics of Modern Foreign Catholic Organizations in China 近代外国天主教会组织在华建筑活动及其空间特征. The World Religious Cultures 3: 148–53. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Zhihao 李智浩. 2006. Rethinking of Syncretism: Discussion of How Karl Ludvig Reichelt Used the Elements of Buddhism to Present Christianity 混合主义的迷思——析论艾香德以耶释佛的尝试与根据. Journal of Religion and Culture of National Cheng Kung University, 139–77. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen, Hans Helge. 2003. Prip-Møllers Kina: Arkitekt, missionær og fotograf i 1920rne og 30rne. Copenhagen: Arkitektens Forlag. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Changxin 彭长歆. 2011. Normalization or Localization: Adaptability Strategies of Church Architecture in ModernChina—Investigations in Lingnan 规范化或地方化:中国近代教会建筑的适应性策略——以岭南为中心的考察. South Architecture, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prip-Møller, Johannes. 1935. The Hall of Lin Ku Ssu, Nanking. Artes; Monuments et Memoires 3: 167–211. [Google Scholar]

- Prip-Møller, Johannes. 1937. Chinese Buddhist Monasteries. Their Plan and its Function as a Setting for Buddhist Monastic Life. Copenhagen: G. E. C. Gads Forlag. [Google Scholar]

- Reichelt, Karl Ludvig. 1913. Kinas Religioner: Haandbok i den Kinesiske Religionshistorie. Stavanger: Det Norske Missionsselskaps Boktrykkeri. [Google Scholar]

- Reichelt, Karl Ludvig. 1934. Trends in China’s Non-Christian Religions. Chinese Recorder 65. [Google Scholar]

- Reichelt, Karl Ludvig. 1951. Religion in Chinese Garment. New York: Philosophical Library. [Google Scholar]

- Reichelt, Karl Ludvig, and Kathrina Van Wagenen Bugge. 1927. Truth and Tradition in Chinese Buddhism; A Study of Chinese Mahayana Buddhism. Shanghai: The Commercial Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe, Eric J., Hong Shen, and Xinan Yang. 2021. Karl Ludvig Reichelt: Missionary, Scholar and Pilgrim 艾香德: 传教士、学者和朝圣者, 1st ed. Hongkong: Dao feng shu she. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Shangyang 孙尚扬. 2016. From Rejecting Buddhism and Embracing Confucianism to Integrating Buddhism and Dispersing Confucianism: A Comparison of the Missionary Strategies of Matteo Ricci and Karl Ludvig Reichelt 从合儒斥佛到融佛疏儒——利玛窦与艾香德的传教方略比较. Jianhan Tribune 7: 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Yiping 孙亦平. 2010. Karl Ludvig Reichelt and Chinese Buddhism—A case analysis of religious dialogue in the Republic of China 艾香德牧师与中国佛教: 民国时期宗教对话的一个案例. Studies in World Religions世界宗教研究 6: 55–62+194. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeten, Alan Richard. 2020. China’s Old Churches: The History, Architecture, and Legacy of Catholic Sacred Structures in Beijing, Tianjin, and Hebei Province. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Tao Fong Shan Christian Center Website. n.d. Available online: https://www.tfscc.org/about/#vocation (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Wang, Tieya. 1957. Zhong wai jiu yue zhang hui bian. Beijing: Sheng huo du shu xin zhi san lian shu dian. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Weiqiao. 2023. Comparative Review of Ideal Layouts in Han Buddhist and Catholic Monasteries. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 11: 1–38. (In press). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Zhixin 王治心. 2004. Zhongguo Jidu jiao shi gang 中国基督教史纲, 1st ed. Penglai ge cong shu. Shanghai: Shanghai Ancient Works Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Anping 肖安平. 2014. A Reflection on the Sinicization of Christianity: The Indigenization Movement--Discussing the Intersection of Christianity and Chinese Culture 一个基督教中国化的反思: 本色化运动——兼论基督教与中国文化的交会. Jinling Theological Review 金陵神学志 Z1: 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Liping 徐丽萍. 2014. General Revelation and Religious Dialogue: An Analysis of Reichelt’s Unique Missionary Approach 一般启示与宗教对话:艾香德式的独特传教进路探析. Master dissertation, Shanghai Normal University, Shanghai, China. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Ying 薛颖, and Pan Yin 鄞盼. 2021. Study on the Localization of Modern Anglican Church Buildings in Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao 粤港澳近代圣公会教堂建筑的本土化研究. Architecture and Culture 2: 249–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Bingde. 2003. Zhongguo jin dai Zhong xi jian zhu wen hua jiao rong shi = The Combination History of Sino-West Architectural Culture in Modern Times of China, 1st ed. Wuhan: Hubei jiao yu chu ban she. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Wuna 周悟拿. 2023. Norwegian Missionary Society in Hunan Province of China (1902–1950) 挪威信义会在湖南活动之研究 (1902–1950). Ph.D. dissertation, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Zhenru. 2022. Transcending History: (Re)Building Longchang Monastery of Mount Baohua in the Seventeenth Century. Religions 13: 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, W.; Liu, Y. “Buddhist-Christian Style”: The Collaboration of Prip-Møller and Reichelt—From Longchang Si to Tao Fong Shan Christian Centre. Religions 2024, 15, 801. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15070801

Wang W, Liu Y. “Buddhist-Christian Style”: The Collaboration of Prip-Møller and Reichelt—From Longchang Si to Tao Fong Shan Christian Centre. Religions. 2024; 15(7):801. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15070801

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Weiqiao, and Yan Liu. 2024. "“Buddhist-Christian Style”: The Collaboration of Prip-Møller and Reichelt—From Longchang Si to Tao Fong Shan Christian Centre" Religions 15, no. 7: 801. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15070801

APA StyleWang, W., & Liu, Y. (2024). “Buddhist-Christian Style”: The Collaboration of Prip-Møller and Reichelt—From Longchang Si to Tao Fong Shan Christian Centre. Religions, 15(7), 801. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15070801