Historically, Dunhuang was a region where diverse ethnicities coexisted and blended together. Han culture predominated, establishing Mandarin Chinese as the lingua franca. There was also a circulation of foreign cultures and languages, especially during the period of Tibetan occupation from 786 to 848 AD, when Tibetan also became an official language alongside Chinese. The question of how beginners accepted and learned Tibetan or Chinese as new languages is thus a topic worthy of exploration. Indeed, the discovery of the Dunhuang manuscripts in the last century has sparked considerable scholarly interest in this issue. Several scholars, including F. W. Thomas and G. L. M. Clauson

1, have concentrated their discussions on a particular type of material, namely bilingual and transliteration materials, which are crucial for understanding the historical process of Sino–Tibetan integration. Notably, many bilingual texts serve as educational materials for beginners, providing valuable insights into the learning process of Chinese or Tibetan for novices. As an example, the Tibetan–Chinese glossary Pelliot tibétain 1257 (hereafter, P.T. 1257), which is discussed in this paper, represents a bilingual vocabulary list of significant research value for understanding the linguistic and cultural exchange between these two traditions. Digital images of the manuscript are found at the websites of the Gallica Digital Library (

http://gallica.bnf.fr, accessed on 3 June 2024) and the International Dunhuang Project (

http://idp.bl.uk/, accessed on 3 June 2024).

The manuscript P.T. 1257 consists of (1) ten sheets, each approximately 30 cm in width and 40 cm in length

2, and (2) a cover made by joining two sheets, with the first sheet measuring 30.6 cm in width and 49 cm in length, and the second sheet measuring 30 cm in width and 45 cm in length. The bottoms of these sheets were once secured together with a bamboo stick

3. This stick, now broken into two segments, measures 16.9 cm and 12 cm in length, respectively

4.

The first set of ten sheets actually contains two distinct sections. The initial segment, spanning sheets 1 and 5–10, is a “

Tibetan-Chinese Bilingual Vocabulary List” that includes a range of Buddhist technical terms or Buddhist terms with numeric correspondence, as well as excerpts from the

Saṃdhi-nirmocana-sūtra5. This glossary contains approximately 570 entries, with the Chinese terms provided above and their corresponding Tibetan terms listed below. The vocabulary is systematically organized into word families, each beginning with a “headword” followed by its “derivatives”. For instance, the term for “Four Great Continents” is illustrated with a headword 四部洲/

glIng bzhI (10.3.6) and its derivatives 東弗於大/

shar gyI lus ’phags gling (10.3.7), 南閻浮提/

lha’I ’dzam bug (10.4.1), 西俱耶尼/

nub gyI bal glang spyod (10.4.2), and 北越單/

byang gI sgra myi snyan (10.4.3), each representing different aspects of the concept

6. The other section consists of the “

Tibetan-Chinese Bilingual Buddhist Scripture Catalogue”, covering sheets 2–4. These two sections exhibit distinct scribal characteristic. The Tibetan–Chinese bilingual entries in the “

Tibetan-Chinese Bilingual Vocabulary List” are arranged horizontally from left to right, while the “

Tibetan-Chinese Bilingual Buddhist Scripture Catalogue” features Tibetan script arranged horizontally, with Chinese characters presented in various writing forms. Furthermore, the calligraphic strokes of both the Tibetan and Chinese sections are notably distinct. Consequently, it is evident that they were not executed contemporaneously. The primary focus of this study is the first part, the bilingual glossary.

In the academic history of research, it is possible that the earliest to take note of P.T. 1257 was none other than Paul Pelliot himself, who brought this manuscript to France. In

The Northwestern Dialeacts of Tang and Five Dynasties, published in November 1933,

Luo (

1933, p. 12) mentioned that Pelliot had referred to this manuscript as a potential research material. Pelliot also promised to send him the plates later

7. However, this manuscript does not appear to have been utilized in Luo’s subsequent research, so it remains unknown whether Pelliot fulfilled his promise. Over a decade later, Lalou conducted the first thorough investigation of P.T. 1257 while compiling the catalogue of the Tibetan documents from Dunhuang housed in the

Lalou (

1950, p. 94), disclosing the physical characteristics of the manuscript.

Fujieda (

1961, p. 291) and

Drège (

1984, pp. 196–98) subsequently conducted examinations of its binding form. As research on the Tibetan documents from Dunhuang progressed, it was not until the 1970s that scholars began to focus their studies on this manuscript.

Ueyama (

1976) was the first to suggest that this manuscript may have been produced during the process of development into the

Bye brag tu rtogs par byed pa (

Mahāv yutpatti).

Hakamaya (

1984), in his study of the Tibetan translation of the

Saṃdhi-nirmocana-sūtra, examined the related vocabulary in P.T. 1257 and posited that they might have been extracted from the Tibetan translations of the

Saṃdhi-nirmocana-sūtra such as S.T. 194 and 683.

Kimura (

1985) conducted a systematic examination of the vocabulary in the manuscript, confirming that these terms were all Old Tibetan translations collected during the mid-to-late eighth century reign of the Tibetan King Khri song lde brtsan (r. 742–97 CE).

Akamatsu (

1988) analyzed the Buddhist scripture titles in P.T. 1257, and suggested that the list might be a catalog of Tibetan translated scriptures and treatises preserved in a Dunhuang temple.

Apple and Apple (

2017) revisited this manuscript with a comprehensive study, revising some of the conclusions drawn by previous researchers.

Collectively, their research focuses on three main issues: the antiquity of the vocabulary, the dating of the manuscript, and the users of the text. Despite extensive discussions, a definitive consensus has not been reached. Regarding the age of the vocabulary, it is generally agreed that the vocabulary largely consists of Old Tibetan translations used during the reign of Tibetan King Khri Srong lde brtsan (r. 742–97 CE) in the mid-8th century

8. However,

Hakamaya (

1984, p. 178) posits that the vocabulary may indeed incorporate a subset of the new standard translation terminology promulgated by the imperial edict of 814 CE, such as the translation of “如來” as “

de bzhin gshegs pa” (6.4.5) and “

yang dag par gshegpa” (7.3.2), as well as the translation of “成所作智” as “

bya ba nan tan gyI ye shes” (10.2.3). Secondly, regarding the dating of the manuscript, the majority of scholars concur that it was composed around the year 814, coinciding with the promulgation of the new vocabulary. However, considering the potential existence of later translation usages observed by Hakamaya, the assertion that the manuscript must have been completed prior to 814 may be somewhat overly absolute. Subsequently, the matter of the manuscript’s users has not been rigorously discussed, with previous scholars holding divergent opinions. Some have conjectured that the manuscript may have been in circulation among Chinese monks learning Tibetan, while others believe it was used by Tibetan monks learning Chinese. Moreover, their research has been predominantly within the realm of linguistics, lacking more in-depth historical and philological perspective. Consequently, there is still room for further discussion on this manuscript. The present study primarily endeavors to address the following questions:

The calligraphic characteristics of the Chinese vocabulary on each sheet and the original sequence of the sheets.

The sequence of Tibetan and Chinese vocabulary in the glossary.

Discrepancies between Tibetan and Chinese translations of the same term in the manuscript, and instances where Chinese translations are missing.

The nature of the glossary and its users.

In addition to the aforementioned issues, there are also some areas for improvement in the academic transcriptions of this manuscript, particularly with regard to the transliteration of Tibetan script. However, due to space limitations, a detailed enumeration will not be pursued here. The author’s contemplations on these matters are currently in a preliminary stage and are subject to refinement. I kindly invite feedback and correction from esteemed scholars in the field.

1. The Calligraphic and Layout Form Characteristics of Chinese Vocabulary, and the Original Arrangement Order among the Sheets

Previous scholars have regarded this

Tibetan-Chinese Bilingual Vocabulary List as a whole. For instance,

Spanien and Imaeda (

1979) posited that the sequential arrangement of the glossary’s sheets is from 10 to 4, thereby overlooking the differences that exist within its internal components.

Apple and Apple (

2017, pp. 76–77) have endeavored to ascertain the sequence of the sheet based on the continuity of vocabulary meanings, yet their efforts were not systematic. Furthermore, they posited that this manuscript contains at least five or seven distinct styles of Chinese calligraphy, but they did not specify how to distinguish between these handwritings, nor did they detail what content was written in each style. We believe that relying solely on calligraphy may entail significant risks, as some calligraphic styles may not exhibit strong individual characteristics. In fact, in addition to calligraphy, the vocabulary list also exhibits various significantly different layout forms, which can aid in understanding the complex writing process of this manuscript and in determining who wrote which parts

9.

The first sheet, line 1 to the seventh column of the eighth line on the eighth sheet, and sheets 9–10 display a high distinctive layout style, where all Chinese phrases, irrespective of their length, are written from top-to-bottom along the left side. Additionally, the calligraphy strokes within these sections are notably uniform, with the characters presenting a consistent slant. This particular style of writing is tentatively classified as Type A. Across these sections, there are a total of 327 instances where Type A script is employed, with 7 instances of omitted Chinese characters.

On the seventh sheet and below the eighth column of the eighth line on the eighth sheet, the direction of Chinese character writing is determined based on the available space and the length of the vocabulary, with characters being written vertically or horizontally. The calligraphic strokes are relatively uniform, characterized by straight strokes. We tentatively classify this writing style as Type B. There are a total of 115 vocabulary entries written in this manner, with 8 instances where Chinese characters are missing.

Sheets 5 and 6 exhibit a relatively unique writing style characterized by consistent calligraphy, with almost all vocabulary written horizontally, except for a few individual words. We tentatively designate this as Type C. There are a total of 126 vocabulary entries in this style, with 30 instances of missing Chinese characters. However, upon closer examination of the content, Type C can be further divided into two subtypes. The first subtype comprises the first and second lines on the sixth sheet, which contain Buddhist technical terms, referred to as C1. In C1, the headwords of all word families are written vertically, while the derivatives are written horizontally. There are a total of 20 vocabulary entries in this subtype. The second subtype, C2, consists of vocabulary excerpts from the Saṃdhinirmocana-sūtra, encompassing sheet 5 and the third line and below on sheet 6. There are a total of 106 vocabulary entries in this subtype, with 30 instances of missing Chinese characters.

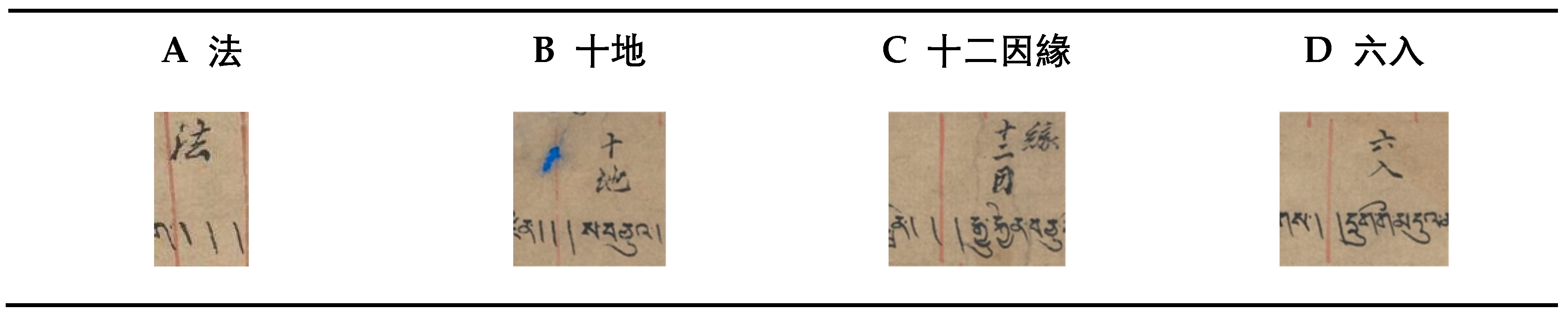

To present the differences among the various types more intuitively, I have selected four examples from each type to include in

Table 1.

Therefore, considering the combined factors of calligraphic strokes and layout styles, it is likely that at least three individuals were responsible for the Chinese vocabulary section. If the Tibetan vocabulary section was attributed to a separate individual, then this bilingual vocabulary list was completed by at least four contributors.

Sheet 8 features at least two distinct writing styles, A and B, suggesting that they were collaboratively executed by different individuals. The transition points between Type A and Type B are marked by the terms “中阴身/lnga phung bar ma” (8.8.7) and “影像/gzugs brnyan” (8.8.8). These words, along with seventeen others from “虚空/nam ka’” (8.7.5) to “风轮/rlung gI khrul ’khor” (8.9.9), form a word family, all relating to “虚空” (emptiness). This implies that the last few words of Type A and the first few words of Type B belong to the same word family. The cessation of copying by the scribe of Type A at 8.8.7 seems to be a somewhat arbitrary choice, unrelated to the word family or the spatial distribution of the lines.

Next, let us examine the original sequence of the individual sheets. The current physical order of P. T. 1257 appears chaotic, indicating that it is not the original order among the sheets. However, based on the analysis of the calligraphy and layout styles discussed in the preceding text, combined with the content written on the sheets, we can approximately reconstruct the original arrangement and sequence of transcription among the sheets.

The sequence of the first, seventh, eighth, ninth, and tenth sheets may be directly related. Firstly, the relationship between the eighth and seventh sheets, as well as between the tenth and ninth sheets, can be easily determined. The order of the eighth and seventh sheets can be established because the selection of terms on both sheets predominantly appears in the form of word families. The last line of the eighth sheet lists “天龍八部” (eight kinds of demigods), but only mentions the first seven, whereas the first word of the first line on the seventh sheet is the eighth sect, “魔

10猴羅伽 (Mohoraja)/lto phye chen po”. The determination of the sequence of the tenth and ninth sheets follows the same method as for the eighth and seventh sheets. The last entry on the tenth sheet is “八聖道 (the Noble Eightfold Path)/

’phags pa’I laM brgyad” (10.11.9), and the first entry on the ninth sheet corresponds to the content of the Noble Eightfold Path.

Secondly, the connection between Sheet 1 and Sheet 10 can be reasonably established. Both Sheets 1 and 10 deal with the concept of Buddhist technical terms. The first sheet has already elaborated on the category of “four”, with the last group being “四顛倒 (Four inverted beliefs)/

phyIn cI log bzhI” (1.10.4). Although the first line of Sheet 10 is incomplete, evidence suggests that the missing content, as indicated by the surviving Tibetan letters “

sgo nga las skye ba” (卵生, aṇḍa-ja, birth from eggs) and the remaining complete phrase “化生 (upa-pāduka, birth by transformation)/

rdzus te skye ba’11” indicate that the missing content is “四生 (catur-yoni, four types of birth): 胎生 (jarāyu-ja, birth from the womb), 濕生 (saṃsveda-ja, birth from dampness), 卵生 (birth from eggs)”, which also falls under the Dharma numerical classification of “four”. Therefore, sheets 1 and 10 are also logically connected in terms of content continuity.

Again, the relationship between sheets 9 and 8 is not easily determined, but there is a certain correlation between them. The vocabulary from the 7th line onwards of the 9th sheet and that of the 8th sheet can be categorized into multiple groups, with the terms within each group predominantly being synonyms, while the adjacent pairs of groups tend to consist largely of antonyms. The final group of Sheet 9 consists of the words “任運成就 (to accomplish something by letting it occur naturally)/

lhun gyIs grub” and “通達 (understand thoroughly)/

khong du chud”, which are synonyms and form a small group. The first group on Sheet 8 consists of the words “

bar du gcod pa (hinder)”

12 and “障 (block)/

bsgrIbs pa”, “覆 (cover)/

gyog pa”, and “蓋 (cover)/

bkab pa”, which are synonyms and also form a small group, but they are antonyms of “任運成就” and “通達”. Therefore, it is plausible that the ninth and eighth sheets are sequentially related.

Lastly, upon meticulous examination by the author, a specific symbol “

![Religions 15 00748 i023]()

” is observed preceding the first word of the first line on the first sheet. This symbol is not part of the letters for the initial word “

dge’ ba’/善 (virtue)”, but rather the Tibetan initial mark (Yig Mgo Mdun Ma), which is a symbol traditionally written at the beginning of a document. Therefore, it can be confirmed that Sheet 1 is the starting point of the Type A content. This can also be corroborated by the content itself, as the content from the first line to the second column of the third line on this sheet belongs to the “two” category of Buddhist technical terms, followed by the “three” category, indicating that this should be the foremost content of such lexical entries.

The first sheet, the eighth sheet, the ninth and tenth sheets, and the sixth and fifth sheets all contain terminology excerpts from Volume One of the Saṃdhi-nirmocana-sūtra. Therefore, the sequence of these terms within the Buddhist scripture can be utilized to ascertain the relative order of these sheets. However, the order of the seventh sheet in relation to the sixth sheet appears to lack a direct connection, as the last few lines of the seventh sheet contain groups of terms that form antonyms, while the first and second lines of the sixth sheet belong to the category of technical terms starting from “three”. Therefore, they exhibit distinct characteristics. Nonetheless, given that there are six narrow strips of paper devoid of any writing between the seventh and eighth sheets, it can be inferred that there are at least six missing sheets between the seventh and eighth sheets. Therefore, at present, the possibility of a connection between the sixth and fifth sheets and the other sheets cannot be ruled out abruptly.

In summary, based on the current available analysis, it is only possible to provisionally arrange the aforementioned sheets into two groups, namely 1-10-9-8-7 and 6-5. The existing binding order is almost entirely different from the original sequence, suggesting that the binder may not have arranged the sheets in the original sequence, and may have even been unaware of the original sequence. However, the order of the last four sheets (10-9-8-7) is exactly the reverse of the original sequence, implying that when the binder collected these documents, they may have still roughly maintained a certain order.

2. The Sequence of Tibetan and Chinese Vocabulary, and Red Lines in the Lexicon

Based on the observation that there are columns or sections of the lexicon section that have only Tibetan terms and also do not have any Chinese equivalent terms written above them

13,

Kimura (

1985, p. 628) and

Apple and Apple (

2017, pp. 85–86) inferred that the original order of transcription for this lexicon was Tibetan followed by Chinese. While this inference is generally plausible, it does not provide a comprehensive explanation. Within this manuscript, there are three elements: Tibetan vocabulary, Chinese vocabulary, and red lines serving as separators between words

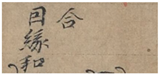

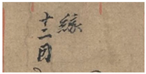

14. Therefore, the inference of James Apple and Shinobu Apple only partially explains the general transcription order of the vocabulary list. Further questions arise: (1) the sequence of writing Tibetan and Chinese terms and the red lines, and (2) whether the Chinese vocabulary was filled in after all the Tibetan terms were written.

In addition to the evidence provided by James Apple and Shinobu Apple regarding the frequent vacancies in the Chinese vocabulary, the positional relationships among Tibetan vocabulary, Chinese vocabulary, and the red lines are also worthy of our attention. These positional relationships provide the most direct basis for refining our analysis of the sequence among the three elements.

Firstly, examining the general sequence among the three elements,

Table 2 below lists the most exemplary instances from each sheet that illustrate the positional relationships between them.

Based on the statistical analysis presented in the table above, it can be observed that, with the exception of Sheets 9 and 10 where no clear positional overlap is observed among the three elements, nearly every sheet provides a typical case that illustrates the sequence of the three elements. It can be confirmed that the general order is as follows:

Furthermore, the occurrence of the red line from the previous line encroaching upon the Chinese characters in the next line on multiple sheets indicates that the scribes at least transcribed an additional line of Chinese vocabulary before drawing the red line. This sequence is observed across all types of script, suggesting that all scribes adhered to a similar order of transcription.

This is different from the general sequence mentioned earlier. This phenomenon may be explained in two ways: (1) Instead of drawing the red line after completing all the Chinese vocabulary, the scribes drew the red line after completing a portion of the Chinese vocabulary (possibly at least an additional line), and then extended the red line beyond the written Chinese vocabulary to include an additional section. (2) The last two lines may have been transcribed by a different individual from the rest of the manuscript, which would account for the observed difference in the sequence of drawing the red lines and filling in the Chinese vocabulary. Supporting the second explanation, there is evidence that the Tibetan vocabulary in the last two lines does not align with the preceding content; while the earlier content is excerpted from the Saṃdhi-nirmocana-sūtra, these two lines are Buddhist technical terms.

In summary, based on the above analysis, the general sequence of this vocabulary list is likely to be “Tibetan vocabulary → Chinese vocabulary → red lines”, and it is highly probable that the Chinese vocabulary and red lines were filled in after all the Tibetan vocabulary were written. However, the Chinese vocabulary may not have been written all at once, followed by the drawing of the red lines in a uniform manner.

3. The Phenomenon of Missing Words and the Proficiency of the Scribes in the Chinese Vocabulary List

Type A contains a total of 327 terms, among which there are seven instances where corresponding Chinese terms are not filled in, constituting approximately 2% (7/327) of the total number of terms, as shown in

Table 3.

Type B contains a total of 115 terms, among which there are eight instances where corresponding Chinese terms are not filled in, constituting approximately 7% (8/115) of the total number of terms, as shown in

Table 4.

It is noteworthy that the term “yI dags” (7.4.4) was recorded in Type A, yet it was left unwritten in Type B. Considering the analysis provided earlier, which indicates that the scribe of Type B continued the transcription from the scribe of Type A, this suggests that before filling in the words, the scribe of Type B, despite having received the vocabulary list transcribed by the scribe of Type A, may not have verified the content entered by the latter. This phenomenon may imply that the scribe of Type B was independently filling in the vocabulary list based on his own knowledge, and was not yet familiar with at least eight terms, including “yI dags”.

Type C contains a total of 126 terms, among which there are 30 instances where corresponding Chinese terms are not filled in, constituting approximately 23.8% (30/1265) of the total number of terms, as shown in

Table 5.

So, what are the reasons for these missing terms? There are essentially two possibilities: either the transcriber was unfamiliar with this Tibetan vocabulary, or was unsure of the appropriate Chinese translations for these terms. The former can be attributed to insufficient knowledge of Tibetan, while the latter can be ascribed to limited proficiency in Chinese. In fact, whatever the reason, this suggests that a standardized reference table with definitive answers was not available to the transcriber.

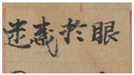

However, in the Type A section, the scribe of Tibetan terms exhibits a particular transcription habit: an additional slash is drawn between two word families, amidst the existing two slashes, to denote the separation between word families and to differentiate it from the separators used between derivatives. This practice can be observed, for example, between the word families “八聖道 (the Noble Eightfold Path)” and “十地 (Ten Grounds of Bodhisattva Path)” in the second line of Sheet 9 (see

Figure 1B), and between the word families “十地” and “十二因緣 (the twelve causes and conditions)” in the third line of Sheet 9 (see

Figure 1C). However, it is important to emphasize that this word family-level separator is unique to the Type A lexicon, and the scribe’s use of this separator is not entirely consistent. For instance, in the same ninth sheet, the fourth line between the word families “十二因緣” and “六入 (the six sense objects)” (see

Figure 1D) does not use this symbol, indicating a considerable degree of arbitrariness in the use of this particular separator.

In conclusion, the presence of a slash here does not indicate omission in the transcription of Tibetan term; rather, it is a fact that the term “

chos” was not transcribed at all during the copying of the Tibetan vocabulary (see

Figure 1B). What then prompts the Chinese scribe to write the character “法”? Was there a basis for this transcription? To address this question, it is necessary to examine the word family to which “法” belongs. This word family is “六塵 (six sense objects)/

yul drug” (10.7.11), with its derivatives being “色 (form)/

gzugs, 聲(sound)/

sgra’, 香 (fragrance)/

drI’, 味 (flavor)/

bro’, 觸 (tangible objects)/

rig, 法 (dharma)”.

Considering that these are some of the most fundamental Buddhist technical terms, the phenomenon of having the Chinese term “法” without a corresponding Tibetan term “

chos” can be interpreted in two ways: (1) The Chinese scribe may have been aware of the omission of the Tibetan term, but since the red line had already been drawn at this point by the scribe responsible for drawing the red lines, the Chinese scribe supplemented it to maintain completeness. (2) The Chinese scribe may not have been aware of the omission of the Tibetan term, but due to their familiarity with Buddhist technical terms and the ample space available for the character “法”, coupled with the fact that the red line had already been drawn at this point, he filled it in out of writing habit. In this regard, the author leans more towards the second explanation, as evidence can be found elsewhere of this filler’s tendency to not strictly correspond with the Tibetan vocabulary due to inertia. Similar to the case in line 7 of Sheet 10, there is a word family “六根 (the six sense organs)/

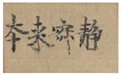

dbang po drug” listed. Its contents are as follows (see

Table 6):

It can be readily observed that, in fact, in the spelling of Tibetan vocabulary, except for the root word “dbang po drug” (six sense faculties, 六根) which has the suffix “dbang po” (root, 根), the other six derivative terms actually do not have this suffix. However, in the transcription of Chinese terms, the first two terms, “眼根” (eye) and “耳根” (ear), do include the character “根”, while the following four terms (鼻, nose; 舌, tongue; 身, body; 意, consciousness) do not have the suffix. It is believed that the presence of “根” in the first two terms is due to the habitual writing behavior of the scribe. Subsequently, realizing that the Tibetan terms do not contain the suffix “dbang po”, the scribe ceased to write the character “根” for the latter four senses.

Similarly, on the tenth sheet, eleventh line, there is the word family for “七寶” (seven treasures) (see

Table 7). In the Tibetan spelling of the vocabulary, only the root word “

rin po che bdun” has the suffix “

rin po che”, while the seven derivative terms are suffix-free. However, in the corresponding set of eight Chinese vocabulary terms, including both the root and derivative terms, six of them have the suffix “寶” (treasure), with the only two exceptions being “摩尼” (mani jewel) and “主藏神” (able ministers of the Treasury). These Chinese terms with the suffix “寶” are likely a manifestation of the scribe’s habitual writing behavior.

Let us now return to the extraneous character “法”. Based on the analysis presented above, I am inclined to posit that the scribe’s inclusion of the additional “法” was a result of habitual writing behavior.

This habitual writing behavior indicates that the scribe of the Chinese vocabulary was quite familiar with both the Chinese terminology and the Tibetan vocabulary pertaining to Buddhist Dharma numerical concepts.

The proficiency of the Chinese vocabulary scribe can be further understood through the following examples. In the vocabulary section, the term “

sangs rgyas” appears five times, specifically in 1.3.2 “覺/

sangs rgyas”

21, 1.3.8 “佛/

sangs rgyas”, 1.6.1 “獨覺/

rang sangs rgyas”, 5.1.5 “現正等覺/

mngon bar sangs rgyas”, and 9.11.5 “佛刹/

sangs rgyas gyI zhing”. However, the corresponding Chinese translations are not consistent, employing both “覺” and “佛”. A similar case can also be observed with the term “

tshor ba”, which appears four times in the vocabulary section, in 1.8.5 “受念住/

tshor ba dran ba nye bar gzhagpa’”, 9.4.4 “受/

tshor ba”, 9.10.9 “覺/

tshor ba”, and 10.5.9 “受/

tshor ba”, using both “受” and “覺” as translations for “

tshor ba”. What accounts for the variation in Chinese translations corresponding to the same Tibetan term?

Kimura (

1985, p. 638) and

Apple and Apple (

2017, pp. 86–87) suggest that the emergence of this phenomenon may be due to some terms being translated from Sanskrit, while others are translated from Chinese. For instance, the translation of “

tshor ba” as “受” (feeling) may be attributed to its origin from the Sanskrit term “

vedanā”, whereas the Chinese translation as “覺” (awakened) could be a result of its derivation from Chinese Chan Buddhist terminology. James Apple and Shinobu Apple further infer that:

P.T. 1257 shows a lack of coordination between its translation terms while demonstrating a Tibetan interest in both Chinese based Chan terminology and Indic terminology. This may indicate that the lexicon was not well organized or was haphazardly put together in its initial composition during a confusing time period before the imperial decrees of 814 CE.

The premise necessary for this explanation to hold is that those who filled in the Chinese vocabulary were able to accurately determine whether different instances of “tshor ba” were translated from Sanskrit or Chinese. However, this is clearly impossible, as these Tibetan terms, except for those excerpted from the Saṃdhi-nirmocana-sūtra, lack any textual context. Thus, based on a single isolated term, it is impossible to discern their nature. In the author’s view, the most plausible explanation is that the scribe of the Chinese vocabulary made appropriate translation choices based on the specific “context of the word family”.

For instance, among the five occurrences of the translation for “sangs rgyas”, three instances—1.6.1 “獨覺/rang sangs rgyas”, 5.1.5 “現正等覺/mngon bar sangs rgyas”, and 9.11.5 “佛刹/sangs rgyas gyI zhing”—can be considered to be fixed expressions that do not require extensive explanation. Section 1.3.2 “覺/sangs rgyas” and the preceding term “眾/sems chan” belong to the same word family. Given that the meaning of “眾/sems chan” is “sentient beings”, “覺/sangs rgyas” actually refers to a “full awakening” individual, which can be translated as either “覺” (awakened) or “佛” (Buddha). The translation for 1.3.8 “佛/sangs rgyas” must be “佛” (Buddha), as it is part of the same word family that includes 1.3.9 “法/chos” and 1.4.1 “僧/dge ’dun”, which corresponds to the fixed expression “佛, 法, 僧” (the Three Jewels) in Chinese. Similarly, among the four translations of “tshor ba”, 1.8.5 “受念住/tshor ba dran ba nye bar gzhag pa’” is a fixed phrase. The translations for 9.4.4 “受/tshor ba” are associated with 9.4.3 “觸/reg pa” and 9.4.5 “愛/sred pa”, which are part of the “十二因緣/rgyu rkyen bcu gnyis la” (the twelve causes and conditions), thus “受” is the appropriate translation. For 9.10.9 “覺/tshor ba”, it is paired with 9.10.8 “rIg pa” (meaning “to know” or “awareness”), and therefore “tshor ba” can only be translated as “覺” (perception), which is synonymous with “知” (to know). Lastly, 10.5.9 “受/tshor ba” and 10.5.8“色/gzugs” belong to the same word family, namely “五蘊/phung po lnga” (five groups of existence). Therefore, “tshor ba” in 10.5.9 can only correspond to the Chinese term “受”.

Upon comprehensive analysis, the author posits that it is the compilers of the Chinese lexicon who, based on varying contexts, employed diverse translations for the same Tibetan term. This demonstrates the compilers’ possession of a sufficiently rich knowledge of Chinese Buddhism.

4. Authorship and Nature of the Glossary

Finally, let us address the fourth question posed at the beginning of this paper regarding the authorship and nature of the glossary.

After conducting a comprehensive and systematic study of this manuscript,

Apple and Apple (

2017, pp. 108–9) suggested that, “This glossary could have been a draft of an official document that was offered to high-ranking Chinese monks by Tibetan authorities in order for both parties to communicate on topics related to Buddhism”, and that “it was copied and circulated by Tibetans among Chinese monks in Dunhuang in order for Tibetan monastic authorities to gain knowledge of Chinese equivalents for Tibetan terms”. The rationale for this conclusion is as follows: (1) The manuscript was written on new paper, not on re-used wastepaper, and received additional special care and treatment several times after the manuscript was initially composed; moreover, all Tibetan terms are written in a very tidy style with care and concentration. These factors suggest that P.T. 1257 seems to be treated well, as if it is a valuable property in a certain monastic community. (2) In this manuscript, the Tibetan vocabulary is written down first and is complete, yet some corresponding Chinese terms are missing.

It must be acknowledged that the conclusions they have drawn are imaginative, yet the arguments they present lack persuasiveness. Firstly, the papers were not particularly special, and the form was quite common at the time; utilizing a new sheet of paper to transcribe a glossary was not an action exclusive to official entities. Secondly, if we accept that this manuscript was commissioned and produced by the authorities for the use of Chinese monks to learn corresponding Tibetan vocabulary, then it would be expected that they would select highly competent personnel to fill in the corresponding Chinese terms, ensuring the authority of the text they provided. However, as James Apple and Shinobu Apple themselves noted in their statistics, approximately 8% of the Chinese vocabulary section is missing. This is clearly contrary to their original intent. Therefore, the hypothesis put forward by James Apple and Shinobu Apple warrants a revisiting and further discussion.

In this bilingual glossary, aside from the omission of the corresponding Tibetan term for “法” (10.8.5), the remaining Tibetan terms appear to be entirely correct

22. As observed by James Apple and Shinobu Apple, the calligraphy of the Tibetan terms is written in a very tidy and consistent style across the various sheets, suggesting that it was completed by an individual with a high level of proficiency in Tibetan. The Chinese vocabulary section, on the other hand, was filled out by at least three individuals in a relay manner, with varying levels of expertise. If the rate of missing terms is indicative of proficiency, then the levels of the scribes for Type A (2%), Type B (7%), and Type C (23.8%) decrease in sequence. Nevertheless, it is still evident that these three Chinese scribes were relatively familiar with the basic Buddhist terminology in Chinese, and their calligraphy was quite mature, indicating that they were not novices in Chinese. Conversely, their proficiency in Tibetan may have been more limited, as 45 Tibetan terms were left without corresponding Chinese translations. In other words, they were likely individuals for whom Chinese was their first language.

Thus, the question arises as to why, on the same manuscript with the Tibetan vocabulary already inscribed, three individuals would collaborate in relay to fill in the Chinese vocabulary. This question, which has not been raised in previous studies, is nevertheless a key issue in understanding this bilingual vocabulary list. This collaborative approach reminds the author of the fact that many Chinese manuscripts, including some for juvenile readers, were also completed by multiple contributors. The presence of multiple handwriting styles within a single manuscript is a phenomenon observable in numerous Dunhuang manuscripts. Additionally, there are also documents that are read by one person and written by another. For example, a manuscript of the popular Tang dynasty children’s primer “Taigong Jiajiao” (太公家教, The Teaching of Taigong) (P.2825) includes a colophon stating, “On the 15th day of the first month in the fourth year of the Dazhong era (850 CE), student Song Wenxian read, An Wende wrote”, 大中四年(850年)正月十五日,學生宋文顯讀,安文德寫 indicating that this juvenile reader’s book was collaboratively completed by two individuals. Consequently, the author surmises that the Chinese vocabulary in the P.T. 1257 bilingual glossary may have been accomplished in a similar fashion: through the collaborative efforts of three individuals who collectively held ownership of this manuscript.

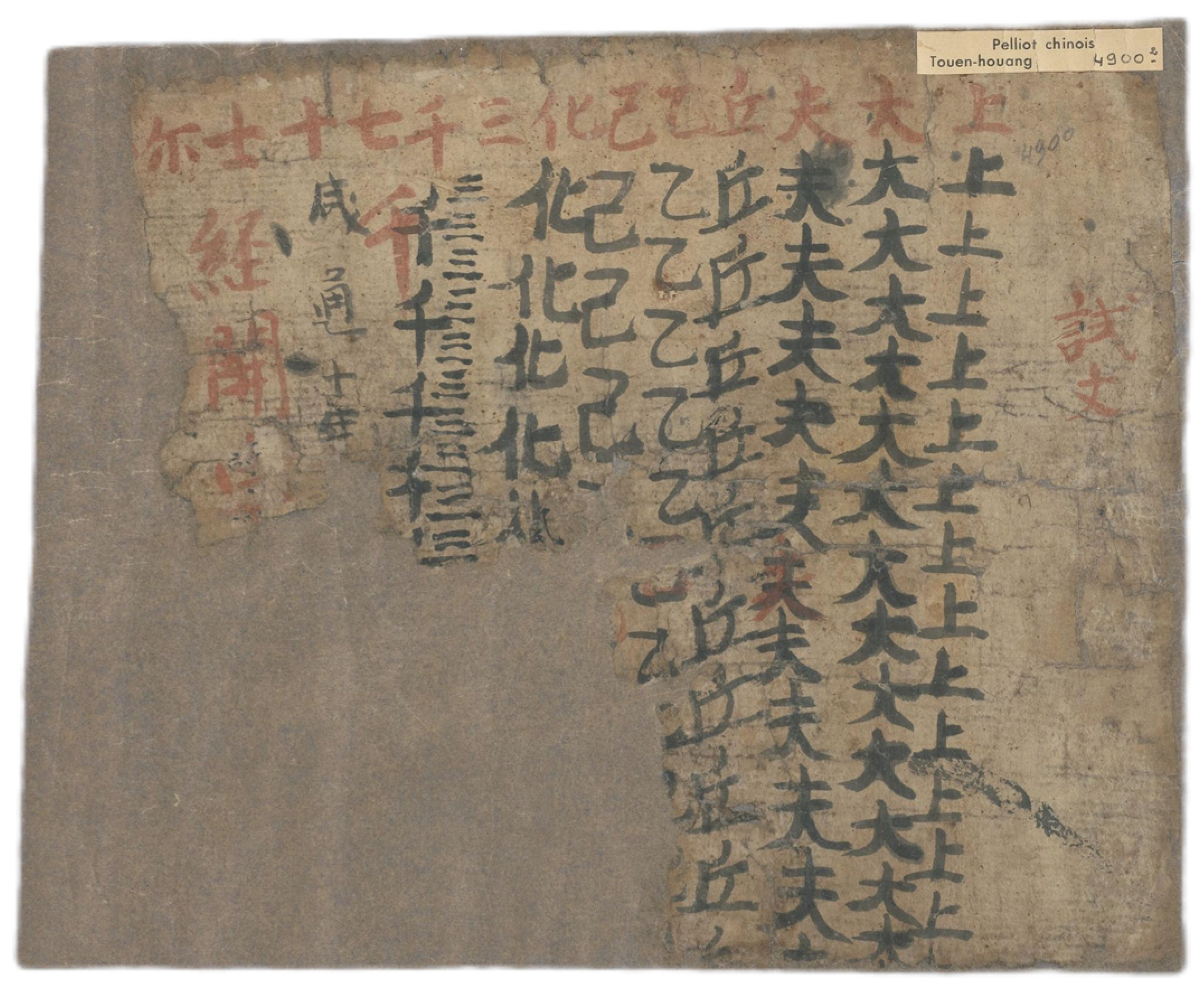

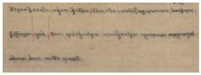

Furthermore, this format, where one person initially writes Tibetan vocabulary and others subsequently fill in corresponding Chinese vocabulary, also easily brings to mind a type of student workbook found in Dunhuang manuscripts. In such workbooks, the teacher first writes down some exercises (such as Chinese characters) that need to be practiced after class, and then the students continue to fill in below the teacher’s handwriting. An example of such an opinion manuscript is P.4900V (see

Figure 2) “The test for

Shang dafu” (上大夫試文), where the teacher initially writes “上大夫丘乙己化三千七十士爾…” at the top of the paper with a brush dipped in vermilion ink, and then the students copy it in ink below, a practice known as “

Shun zhu” 順朱, i.e., following the vermilion (

Unno 2011). From a formal perspective, P.T. 1257 appears very similar to this: first, a Tibetan teacher writes Tibetan vocabulary on the manuscript, and then Chinese students fill in corresponding Chinese vocabulary above the Tibetan vocabulary.

Therefore, based on the above discussion, we believe that this bilingual vocabulary list is likely a workbook created by a Tibetan teacher for Chinese students to learn Tibetan vocabulary. This workbook is filled with Chinese vocabulary by Chinese students, and would have remained in their possession and use thereafter. The Chinese miscellaneous writings on the back of the vocabulary list, such as “大乘百法明门” and “大雲寺張闍和上”, indicate that this vocabulary list later circulated among the Chinese community in Dunhuang. This fact could also serve as evidence that the vocabulary list was originally written and used by the Chinese.

Of course, these so-called “Chinese students” were not young beginners, but rather individuals who were proficient in writing Chinese characters and possessed a considerable amount of knowledge about Chinese Buddhism. The approximate date of this bilingual vocabulary list—shortly before 814 CE—is also a significant issue that merits attention. By this time, it had been over a quarter of a century since the Tibetan occupation of Dunhuang in 786 CE. During this period, many of the Dunhuang residents under Tibetan rule initially learned Chinese knowledge, only beginning to study Tibetan under specific circumstances and at specific times. This indicates that the Tibetan authorities did not enforce a uniform Tibetan education in the occupied regions.

So, under what circumstances did these Dunhuang residents, who already had considerable proficiency in Chinese, begin to learn Tibetan? Or rather, what was their purpose for learning Tibetan? I surmise that this should be related to the booming Tibetan sutra-copying business at that time. According to research, although large-scale sutra copying began during the reign of the King Khri-gtsug-lde-brtsan (802–38, ruled 815–36), the activity likely began to develop during the reign of his father, King Khri-lDe sRong-bTsan (761–815, ruled 798–815). This is because Buddhism experienced rapid development during his reign, and the translation of Buddhist texts made significant advancements. He promulgated the Mahāv yutpatti, which standardized Buddhist translation terminology for the first time.

Dunhuang was an important center for the Tibetan Empire’s Buddhist sutra-copying business, with the sutras copied in Dunhuang being sent to Tibet proper to be offered to the King (

Ma 2009). Of course, for the local sutra copiers in Dunhuang, participating in the sutra-copying project initiated by the King not only meant fulfilling the political tasks assigned to them by the empire, but also meant they could receive sufficient economic rewards. According to

Hao (

1998, pp. 363–65), a monk in Dunhuang in the 9th to 10th centuries could earn 12 to 30

shi 石 (approximately 948 to 2370 kg)

23 of wheat per year by participating in Buddhist ritual activities, while the income from copying a single volume sutra was 1

shi of wheat (

Zheng 2005, pp. 163–64). Therefore, it can be seen that participating in sutra-copying was significant for the economic livelihood of the copyists.

5. Conclusions

Building on the foundation of previous research, this paper conducts a systematic re-examination of the bilingual Tibetan–Chinese vocabulary list in P.T. 1217. By analyzing the interrelations among the vocabulary, the paper confirms the sequential order of the seven folios containing Tibetan–Chinese vocabulary, namely 1-10-9-8-7 and 6-5. In the analysis of the Chinese vocabulary section, the paper proposes a classification method different from previous studies, categorizing the terms not based on their content but on the form of transcription, which suggests that at least three individuals were involved in completing the Chinese vocabulary. By studying the Chinese vocabulary sections assigned to each individual, the author attempts to infer their levels of Chinese cultural proficiency, suggesting that the use of different Chinese translations for the same Tibetan word in different contexts demonstrates a rich knowledge of Chinese Buddhism among the scribes. Finally, the paper argues that this bilingual vocabulary list was likely a workbook created by a Tibetan teacher for Chinese students to learn Tibetan vocabulary. The workbook was filled with Chinese vocabulary by Chinese students, and remained in their possession and use afterward. The Chinese in Dunhuang likely began learning Tibetan due to the Buddhist sutra-copying project initiated by the Tibetan king at the time. Participating in the imperial sutra copying project was not only a political task, but also a lucrative activity for them to earn economic rewards.

” is observed preceding the first word of the first line on the first sheet. This symbol is not part of the letters for the initial word “dge’ ba’/善 (virtue)”, but rather the Tibetan initial mark (Yig Mgo Mdun Ma), which is a symbol traditionally written at the beginning of a document. Therefore, it can be confirmed that Sheet 1 is the starting point of the Type A content. This can also be corroborated by the content itself, as the content from the first line to the second column of the third line on this sheet belongs to the “two” category of Buddhist technical terms, followed by the “three” category, indicating that this should be the foremost content of such lexical entries.

” is observed preceding the first word of the first line on the first sheet. This symbol is not part of the letters for the initial word “dge’ ba’/善 (virtue)”, but rather the Tibetan initial mark (Yig Mgo Mdun Ma), which is a symbol traditionally written at the beginning of a document. Therefore, it can be confirmed that Sheet 1 is the starting point of the Type A content. This can also be corroborated by the content itself, as the content from the first line to the second column of the third line on this sheet belongs to the “two” category of Buddhist technical terms, followed by the “three” category, indicating that this should be the foremost content of such lexical entries.