Ngytarma and Ngamteru: Concepts of the Dead and (Non)Interactions with Them in Northern Siberia †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Discussion

3.1. The Nenets

3.2. The Nganasans

3.3. Comparison

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

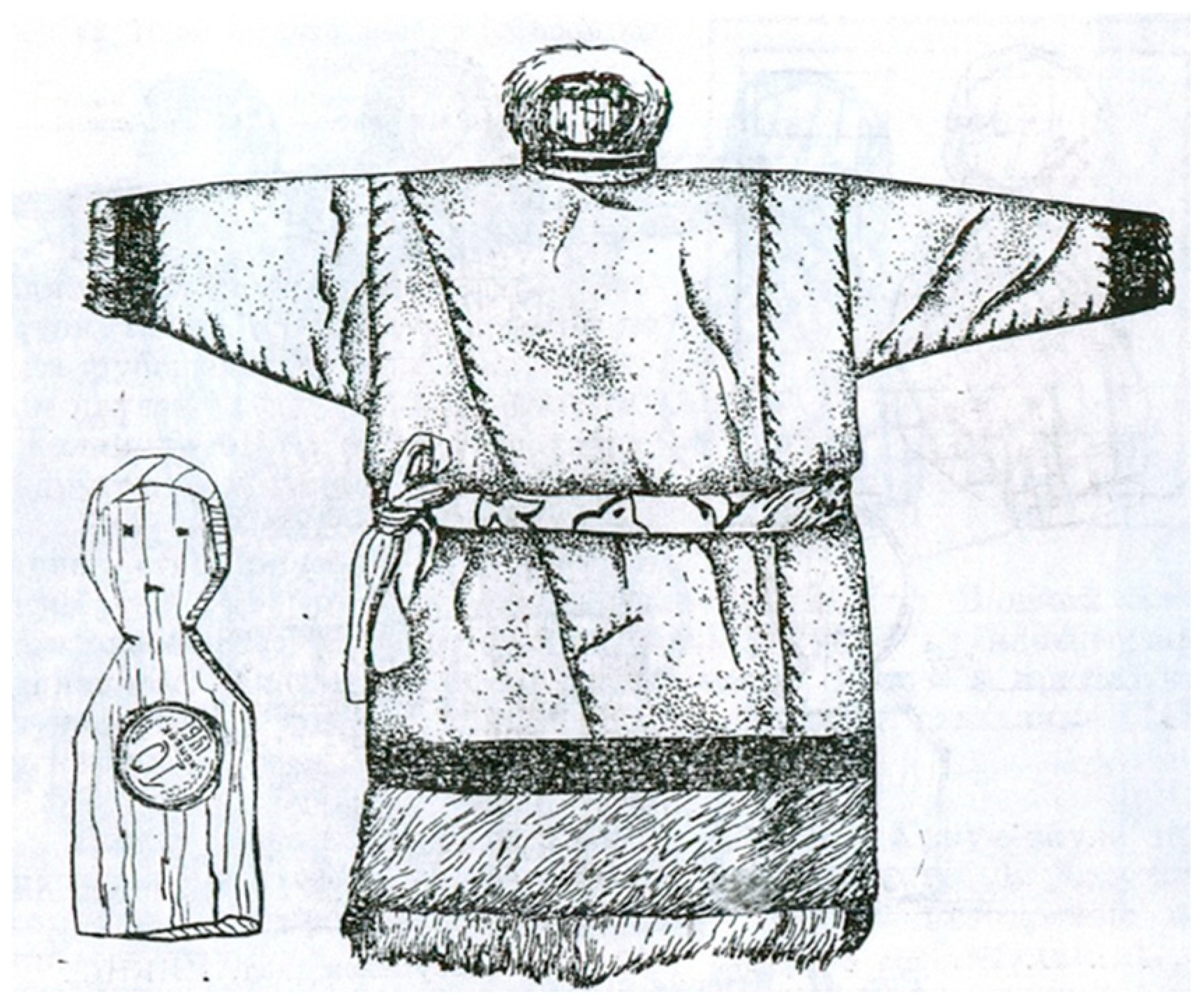

| 1 | The substitutional incarnation practices mean the creation of a particular “receptacle” from wood and/or cloth for the “soul” of the deceased and the interaction of the living with this receptacle (“doll of the dead”). |

| 2 | The influence of the Russian state on indigenous peoples is a big topic. I will only say here that in Russia, the state persecuted traditional religious systems from the 18th century and especially in the 20th century under Soviet rule. From the 1920s onwards, the state initiated changes in the economic lifestyles of the indigenous peoples of Siberia, and from the 1930s onwards, there was forced Russification. For more details, see (Slezkine 1994). |

| 3 | Ongon is a Turkic and Mongolian word for ancestral spirits and their images. In his book, Dmitry Zelenin used this word to describe the religious artifacts of all peoples of Siberia. |

| 4 | “Dolls should be put away at night. One girl did not put them away, and the dolls grew up at night and ate the whole family” (documentary film “Legends and Reality of the Nenets family”. International Fund for Cultural Initiatives “Big Arctic”, 2002. Script writer V. Nyarui, director V. Krylov). Valentina Nyarui told me that she recorded this “legend” (va’al) in Yamal from an elderly Nenets, whose name she did not specify (Nyarui 2002). |

| 5 | The Khantys (previously called the Ostyaks) are a Finno-Ugric language speaking people belonging to the Uralic language family. The Khantys are indigenous inhabitants of Western Siberia (now Khanty-Mansiysk Autonomous Okrug). |

| 6 | Si literally means ‘pure’; it is also the name of the sacred part of the dwelling (chum). |

| 7 | The word is cognate to Nenets sidryang, which is also derived from Nenets sidya, ‘two’ (Gracheva 1976, p. 46). |

References

- Gemuev, Izmail N. 1990. Mirovozzrenie mansi: Dom i kosmos [Worldview of the Mansi: Home and Space]. Novosibirsk: Nauka Publ., Siberian Branch. 232p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Golovnev, Andrei V. 1985. O kul’te ngytarma i sidriang u nentsev [On the Nenets’ cult of ngytarma and sidryang]. In Mirovozzrenie narodov Zapadnoi Sibiri po arkheologicheskim i etnograficheskim dannym [Worldview of the Peoples of Western Siberia According to Archaeological and Ethnographic Data]. Edited by Eleonora L. L’vova. Tomsk: Tomsk University Press, pp. 45–48. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Gondatti, Nikolai L. 1888. Sledy iazycheskikh verovanii u man’zov [Traces of pagan beliefs among the Mansi]. In Izvestiya obshchestvosheniya obshchestvennosti naturaleznanie, anthropologii i etnografii [Proceedings of the Ethnographic Department]. Moscow: E.G. Potapov Publishing House, vol. VIII, 91p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Gracheva, Galina N. 1971. Pogrebal’nye sooruzheniia nentsev ust’ia Obi [Burial structures of the Nenets of the Ob estuary]. In Religioznye predstavleniia i obriady narodov Sibiri v XIX–nach. XX v. [Religious Beliefs and Rituals of the Peoples of Siberia in the XIX—Early XX Century]. Edited by Leonid P. Potapov and Sergei V. Ivanov. Leningrad: Nauka Publ., pp. 248–62. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Gracheva, Galina N. 1976. Chelovek, smert’ i zemlia mertvykh u nganasan [Man, death and the land of the dead among the Nganasans]. In Priroda i chelovek v religioznykh predstavleniiakh narodov Sibiri i Severa [Nature and Man in Religious Beliefs of the Peoples of Siberia and the North]. Edited by Innokentii S. Vdovin. Leningrad: Nauka Publ., pp. 44–66. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Gracheva, Galina N. 1993. Ob adaptivnykh svoistvakh pogrebal’nogo obriada [On adaptive functions of funeral rites]. In Sibirskii etnograficheskii sbornik [Siberian Ethnographic Collection]. Edited by Yu. B. Simchenko. Moscow: IEA RAS Publ., vol. 6, pp. 23–35. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Kharyuchi, Galina P. 2001. Traditsii i innovatsii v kul’ture nenetskogo etnosa (vtoraia polovina XX v.) [Traditions and Innovations in the Culture of the Nenets (Second Half of the XX Century)]. Tomsk: Tomsk University Press. 225p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Khomich, Liudmila V. 1966. Nentsy [The Nenets]. Moscow and Leningrad: Nauka Publ. 329p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Khomich, Liudmila V. 1977. Religioznye kul’ty nentsev [Religious cults of the Nenets]. In Pamiatniki kul’tury narodov Sibiri i Severa (vtoraia polovina XIX—Nachalo XX v.) [Cultural Heritage of the Peoples of Siberia and the North (Second Half of the XIX—Beginning of the XX Century]. Leningrad: Nauka Publ., pp. 5–28. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Krashevskii, Oleg R. 2010. Nganasany. Kul’tura naroda v atributah povsednevnosti: Katalog jetnograficheskogo muzeja na ozere Lama [The Nganasans. The Culture of the People in the Attributes of Everyday Life: The Catalogue of the Ethnographic Museum in Lake Lama]. Noril’sk: Apex Publ. 271p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Lehtisalo, Toivo. 1998. Mifologiia iurako-samoedov (nentsev) [Mythology of the Yurako-Samoyeds (the Nenets)]. Translated from German by Nadezhda V. Lukina. Tomsk: Tomsk University Press. 135p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Nyarui, Valentina. 2002. Recorded in Salekhard. [Google Scholar]

- Orlova, Elena N. 1926. Iuratskie igrushki [Toys of the Juraks]. In Sibirskaia Zhivaia Starina [Siberian Living Antiquity]. Irkutsk: S.n., vol. V, pp. 145–52. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Pavlovskii, Vladimir G. 1907. Voguly [The Voguls]. Kazan: Typo-lithography of the Imperial University. 229p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Popov, Andrei A. 1936. Tavgijcy. Materialy po jetnografii avamskih i vedeevskih tavgijcev. Trudy Instituta Etnografii im. N.N. Mikluho-Maklaja AN SSSR. [The Tawhiti. Materials on Ethnography of Avamsky and Vadeevsky Tawhiti. Proceedings of Institute of Ethnography, USSR Academy of Sciences]. Moscow and Leningrad: AN SSSR Publ., vol. 1, 112p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Popov, Andrei A. 1976. Dusha i smert’ po vozzreniiam nganasanov [Soul and death according to Nganasan beliefs]. In Priroda i chelovek v religioznykh predstavleniiakh narodov Sibiri i Severa [Nature and Man in Religious Beliefs of the Peoples of Siberia and the North]. Edited by Innokentii S. Vdovin. Leningrad: Nauka Publ., pp. 5–43. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Shishlo, Boris P. 1972. Kul’t predkov i zamestiteli umershikh [The cult of ancestors and substitutes of the dead]. Vestnik Leningradskogo universiteta [Bulletin of the Leningrad University] 8: 66–72. (In Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Slezkine, Yu. 1994. Arctic Mirrors: Russia and the Small Peoples of the North. Ithaka and London: Cornell University Press. 484p. [Google Scholar]

- Sokolova, Zoia P. 1990. O kul’te predkov u khantov i mansi [On the cult of ancestors among the Khanty and the Mansi]. In Mirovozzrenie finno-ugorskikh narodov [Worldview of Finno-Ugric Peoples]. Novosibirsk: Nauka, Siberian Bran, pp. 58–72. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Tereshchenko, Natalia M. 1965. Nenetsko-russkii slovar’ [Nenets-Russian Dictionary]. Moscow: The Soviet Encyclopaedia Publ. 942p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Vadetskaia, Elga B. 1985. Mumii i kukly v pogrebal’noi obriadnosti narodov Zapadnoi i Iuzhnoi Sibiri [Mummies and dolls in the funeral rites of the peoples of Western and Southern Siberia]. In Mirovozzrenie narodov Zapadnoi Sibiri po arkheologicheskim i etnograficheskim dannym [Worldview of the Peoples of Western Siberia According to Archaeological and Ethnographic Data]. Edited by Eleonora L. L’vova. Tomsk: Tomsk University Press, pp. 36–38. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Zelenin, Dmitrii K. 1936. Kul’t ongonov v Sibiri. Perezhitki totemizma v ideologii sibirskikh narodov [Ongon Cult in Siberia. Survivals of Totemism in the Ideology of Siberian Peoples]. Moscow and Leningrad: AN SSSR Publ. 436p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Zhuravskii, Andrei V. 1911. Evropeiskii russkii Sever [European Russian North]. Arkhangelsk: Gubernskaia Publ. 36p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

| Name of Personage | Sidryang * | Ngytarma ** | Hehe, Siadey, and Tadyobtsyo | Ngyleka ** | Uko and Nguhuko |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The character of the personage | The shadow soul of the deceased for about 3 years after death | The shadow soul of highly respected persons (shamans and deep elders) 7–10 years after death | Spirit guardians and spirit masters of loci and spirit assistants of the shaman | The evil spirit and the spirit of illness | A doll or a children’s toy |

| Image | Permanent and made by relatives before the burial of the deceased | Permanent and made by a shaman or relatives on his instructions, and he “revives” it | Permanent and made by a shaman | Not permanent and occasionally used for healing; made by a shaman | Permanent and anyone can perform it; includes children (girls) |

| Body | No | Yes (usually) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Clothes | Yes | Yes (maybe several sets) | Maybe (the siadeys do not have it) | No | Yes |

| Face | Yes, longay (a copper button or coin) | Yes (usually) | Maybe (the siadeys definitely do have it ***) | Yes | Goose (duck) beak |

| Behaviour towards a human being | Passive (a human takes care of it—feeds it, puts it to bed, etc.) | Active and patronizing (predicts the weather, calms storms, guards the dwelling, searches for lost reindeer, and heals) | Active and determined by a human being’s actions | Active and harmful (inhabits a person and causes illnesses) | Passive |

| Name of Personage | Sydangka/Sydaranka | Ngamteru | Kuoyka, Nguo, and Dyamada. | Barusi, Kocha, and Syrada | – * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The character of the personage | The shadow soul of the deceased for about 3 years after death | The shadow soul of highly respected persons (shamans and elders) 7–10 years after death | Spirit guardians and spirit masters of loci and spirit assistants of the shaman | The evil spirit and the spirit of illness | A doll or a children’s toy |

| Image | No | No | Permanent and made by a shaman | No | – |

| Body | Yes | ||||

| Clothes | Maybe | ||||

| Face | Maybe | ||||

| Behaviour towards a human being | Neutral | Active and harmful (inhabits a person and causes illnesses) | Active and determined by a human being’s actions | Active and harmful (inhabits a person and causes illnesses) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khristoforova, O.B. Ngytarma and Ngamteru: Concepts of the Dead and (Non)Interactions with Them in Northern Siberia. Religions 2024, 15, 740. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060740

Khristoforova OB. Ngytarma and Ngamteru: Concepts of the Dead and (Non)Interactions with Them in Northern Siberia. Religions. 2024; 15(6):740. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060740

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhristoforova, Olga B. 2024. "Ngytarma and Ngamteru: Concepts of the Dead and (Non)Interactions with Them in Northern Siberia" Religions 15, no. 6: 740. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060740

APA StyleKhristoforova, O. B. (2024). Ngytarma and Ngamteru: Concepts of the Dead and (Non)Interactions with Them in Northern Siberia. Religions, 15(6), 740. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060740