Abstract

This paper challenges the World Religion Paradigm (WRP) dominating religious studies, advocating for a decolonial approach that focuses on diverse and often marginalized religious expressions. The approach that prioritizes world religions over the rich diversity of religious expressions in multiple modernities turns out to be insufficient and biased. Through theoretical research, this paper explores the implications of multiple modernities for the religious landscape. Drawing on Eisenstadt’s theory of multiple modernities, the analysis critiques linear notions of modernization and secularization, and it highlights the complex interplay between religious centers and peripheries. It develops a critical examination of how the theory of the Axial Age, by prioritizing elites and centers in the historical genesis of world religions, generates a preconception that overlooks the religious and spiritual productivity of the peripheries, which persists within current interpretative frameworks. To emphasize the dynamic between center and periphery as a key factor in understanding religious diversity, the text proposes some theoretical theses. By embracing a diversity paradigm and decolonizing frameworks, this paper offers a more inclusive understanding of religious phenomena, contributing to a broader discourse on religion and spirituality beyond Eurocentric perspectives.

1. Introduction: Religious Diversity Concealed by the World Religion Paradigm

The notion that religion is solely associated with a predefined set of recognizable forms within major institutionalized religions pervades both public opinion and scholarly discourse. While the current academic discourse acknowledges the complexity, diversity, and multifaceted nature of the phenomenon under scrutiny (Berger 2014; Beyer and Beaman 2019), biases persist within traditional approaches and implicitly within quantitative analyses. These approaches tend to view the subject through a paradigm that favors institutional manifestations labeled as world religions (Owen 2011; Cotter and Robertson 2016; Cox 2016).

These manifestations are typically associated with organized entities such as churches, mosques, temples, sanctuaries, and monasteries, as well as with specialized figures like prophets, pastors, priests, monks, imams, ulamas, and gurus—characteristics inherent to official religions. This tendency arises from the inclination to equate the religious solely with certain manifestations of the phenomenon, thus universalizing it and overshadowing the multitude of expressions—many of them subaltern—that have emerged throughout history and in social life. Furthermore, many of these expressions are disqualified as degraded, bastardized or false manifestations of the religious.

World Religion Paradigm (WRP)

The academic literature on religions has long criticized what is referred to as the World Religion Paradigm (WRP) (Owen 2011; Cotter and Robertson 2016; Cox 2016). The concept of world religions has been employed in the field of religious studies to encompass at least five, and sometimes more, religions considered particularly large, globally influential, or significant in shaping the world: Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, and Judaism. Scholars frequently utilize this classification to diversify the study of religion beyond its predominant focus on Christianity. Nevertheless, this conventional notion is typically centered on a relatively distinct and uniform phenomenon. It particularly focuses on what has been defined as institutionalized “religion”, as found worldwide. Other overarching categories include folk religions, Indigenous religions, and new religious movements. However, often, the rich diversity of particular and/or cross-cutting or relegated expressions of religions and spiritualities within specific historical traditions and across various geocultural regions of the world is either marginalized or completely overlooked.

This problem arises because the contemporary notion of religion, as has been pointed out by Nongbri and Smith, is a product of Western invention (Nongbri 2013; Cox 2016). Indeed, the definition of religion has been and remains problematic (Alatas 1977; Cox 2016; Schilbrack 2022), often conflated with a Eurocentric perspective on Christianity. Consequently, any endeavor to define religion should strive to be impartial and free from biases introduced by the particularities of Western society (Parker 2006; Spickard 2017). As Masuzawa (2005) elucidates, the concept of world religions, pervasive in the discourse, initially aims to acknowledge religious plurality but has served as a means through which the Western discourse on religion has upheld the distinctiveness and supremacy of Christianity. Western modernity has precisely advocated for a clear distinction between what is considered religious and what is not. On the one hand, its social and political structures have been designed to delineate the boundaries between the sacred and the secular. On the other hand, this understanding of religion has facilitated the division of functional domains within society, thereby contributing to the characterization of the phenomenon of “secularization” in modern societies. This process has developed exceptionally in Europe, where it has since been developed as an interpretive framework. This thesis has been erroneously generalized to the rest of the world when it was only valid for the European experience (Davie 2002).

2. The Issue under Study: Theoretical Foundations of the WRP

The issue we aim to address here is not the predominance of the WRP, which obscures diversity and has long been criticized by various authors (Cotter and Robertson 2016). These criticisms of the WRP acknowledge that defining religion outside of those traditions is not an easy matter and that the complexity of the religious phenomenon cannot be reduced to the major traditions, although they offer an analytical classificatory framework that is difficult to escape from (Cox 2016). How can we address diversity beyond the overarching theoretical framework of world religious traditions without falling into new neocolonial perspectives? In this work, we posit that it is necessary to delve into the origin and theoretical foundation of the paradigm of the major religions, and therefore, we focus on critically analyzing the theory of the Axial Age within the framework of the multiple modernities approach.

Hypothesis

Given our assumption that diversity, rather than unity, is the foundation of the social construction and development of religious phenomena, and recognizing the inadequacy of the WRP, we must transcend it to fully comprehend diversity. Our hypothesis is the following:

Overcoming the deficiencies of the WRP involves understanding that the theory of the Axial Age presents an incomplete picture of the emergence of universal religions as it emphasizes the role of elites and thus religious centers, thereby minimizing the role played by religious peripheries in this socio-historical-religious dynamic.

In our discussion of the results of the theoretical and critical analysis we will conduct on the theory of the Axial Age, we will propose three complementary theses that, in our view, extend and deepen the scope of the validation of the hypothesis we have put forward. In this article, our aim is to critically explore one of the main theoretical roots of the Eurocentric privilege of world religions, which we consider to be present in the shortcomings of the theory of the Axial Age.

3. The WRP in Conventional Views on Religion

Before we delve into the critical analysis of the theory of the Axial Age, let us pause to consider the dominance of the WRP in today’s conventional views on the religious phenomenon.

It can be argued that the WRP manifests in at least four major dimensions of the social construction of what is considered mainstream religion. These representations are widespread and prevalent in various regions of the planet: in how public opinion views religion; in how religious statistics are constructed; in a significant portion of teaching about world religions; and in a relevant part of the academic approach that the social sciences still have toward religions today.

3.1. WRP in Common Sense and Public Opinion

The media disseminates the WRP, contributing to the widespread acceptance of a common-sense understanding of religions today. There are numerous examples of how the media and social networks shape or set the agenda in terms of public perception of what religion is supposed to be.

If you explore the internet, you will find an extensive array of information and maps regarding religious diversity worldwide (see Appendix A). Virtually all of this information reproduces, in various forms, the more or less conventional understanding of the world’s various religions: Catholicism, Protestantism, Orthodox Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, Eastern religions (Taoism, Confucianism, Shintoism), other religions, and non-religion. Mentions of the difficulties in recognizing and analyzing minority religions and the methodological challenges of these classifications are scarce or nonexistent.

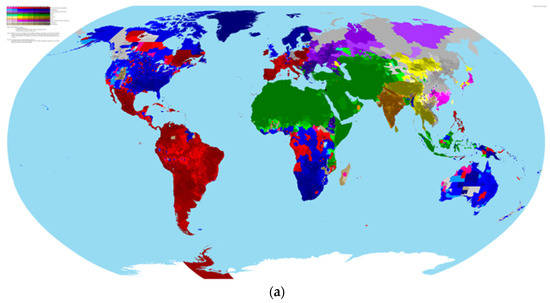

Some religious maps attempt to capture religious diversity in greater detail, such as the one we reproduce below (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(a) the whole view of Highly Detailed World Religion Map; (b) the diagram of Highly Detailed World Religion Map. Source: Map created by Reddit user scolbert08, in https://i.imgur.com/rzv85dn.png (accessed on: 13 May 2024).

This map seeks to establish the percentage differences in religious adherence in each country and region. There are few maps with this level of detail in similar religious cartographies.1 However, the conventional classification persists, which privileges central religions and overlooks the great diversity of peripheral or minority religions and expressions. And certainly, it does not account for the internal detailed diversity within each world religion, with its lived and diverse local expressions. Furthermore, the WRP perspective is present on web pages that provide information for global elites, reinforcing this conventional view of religions. For example, the World Economic Forum’s 2019 webpage or Ipsos 2023 (Boyon 2023).

3.2. Socio-Religious Studies and Statistics

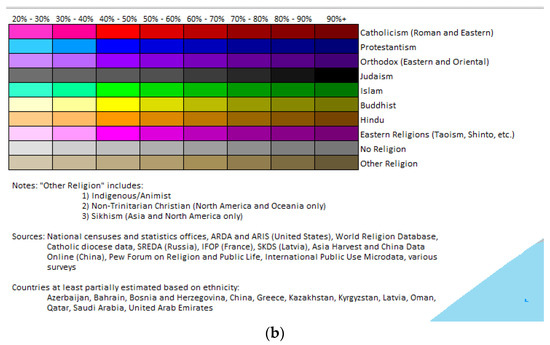

The conventional imaginary, mostly guided by a quantitative epistemology (Brink 1995; Esquivel 2018; Bruce 2018), often equates the religious phenomenon with major universal religions, as evidenced by surveys and global religious statistics. For instance, one of the foremost authorities on religious data, the Pew Research Center (2015), reports that the predominant world religions as of around 2020 include Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Taoism, Shintoism, Buddhism, and Hinduism (See Figure 2). This perspective is echoed in other reputable sources (Johnson and Grim 2018) and surveys.

Figure 2.

Major world religions on the planet following the WRP (circa 2020). Source: Own elaboration with MapChart based on data provided by the Pew Research Center (2015) and supplemented with data from the CIA World Factbook (CIA 2024).

This perspective overlooks the vast religious and spiritual diversity within geocultural regions, as illustrated by the rise of religious diversity in Latin America (Esquivel 2017; Latinobarómetro 2020) and other regions (Borup et al. 2020). Contrary to the outdated characterization of Latin America as predominantly Catholic, comprehensive surveys reveal a decline in Catholicism and a rise in Evangelical denominations and the “non-religious” category (Pew Research Center 2014). According to studies by Latinobarómetro (2020), Evangelical denominations have started to gain traction, with percentages reaching almost 50% in some countries, while the proportion of the “non-religious” rose from 7% in 1995 to 18% in 2020.

However, this quantitative approach favored by the WRP only offers a partial view of the religious landscape, neglecting the intricate diversity present within each religious tradition. In the case of Islam, as well as with other “translocal” world religions (Eller 2022), the same thing happens: characterizations of these religions as unique and homogeneous should not be taken too literally. In reality, translocal religions such as Islam, Christianity, Buddhism and Hinduism exhibit significant diversity, comprising various local groups, doctrines, and practices connected by a shared discourse and scripture. Consequently, translocal religions manifest as local religions. They interact and merge with specific cultures and populations as individuals incorporate religion into their daily lives.

3.3. WRP in Religious Education

The teaching of world religions within religious education programs has evolved over time. Still, many churches approach this topic from a confessional standpoint, aiming to reaffirm their own beliefs while presenting other religions through an apologetic lens. However, more recent initiatives, particularly within renewed churches, emphasize a more ecumenical and tolerant approach, seeking to understand and respect the teachings of other religions while still maintaining an evangelizing intent, as illustrated by Paul Carden’s work (Carden 2020). Mostly, these are endeavors of Christian churches, thus adopting a Christian-centric approach.

In Anglo-Saxon circles, the concept of WRP has been used since the 1960s, championed by scholars of religion aiming to broaden the scope of religious education beyond Christianity to encompass other significant traditions worldwide. While the WRP has been a cornerstone of undergraduate and high school courses, it has faced criticism from the Religious Study Project (Cotter and Robertson 2016).2 Critics argue that it privileges Protestantism as the standard for defining religion, is intertwined with discourses of modernity, and promotes an uncritical view of religion. I would add that it is Eurocentric and West-centric. In the world of education, several encyclopedias (Britannica 2024; Larousse 2024), handbooks and pedagogical resources (Gale 2022) also draw from the WRP. However, proponents maintain that despite these critiques, the paradigm remains valuable within educational settings, particularly if students are made aware of its constructed and complex nature.

In democratic European countries where religious diversity is expanding and interreligious dialogue is encouraged, intercultural programs about world religions have been developed. These programs aim to introduce religions within the context of European Community policy (Hourmant 2021). Collaborative efforts involving five European academic institutions have resulted in the creation of twenty online modules, which cover various traditions of world religions with an open approach to coexistence, conflicts, differences, and similarities between religions.

3.4. WRP in Social Sciences’ Scientific Approaches

In scientific approaches within the social sciences, efforts have been made to expand beyond the limitations of the WRP, although its influence persists. Scholars strive for greater inclusivity, encompassing a wide array of religions, including Indigenous beliefs, African traditions, and new religious movements, particularly within Western contexts. Additionally, cross-cultural themes such as gender and the religious experiences of diaspora communities and migrants are increasingly considered. Despite all these advances, efforts like those of Hinnells (2010) remain a Christian and Anglo-centric view regarding religious phenomena.

Moreover, the scientific literature in this field has made commendable strides in acknowledging the difficulties and improving the statistical treatment of religious data (Maoz and Henderson 2013; Lin et al. 2022). This literature provides a more detailed observation of different religious alternatives, although the classification into religions and religious trees still yields similar types.

The approaches of the social sciences to contemporary religions continue to privilege certain themes within Western-centric, Christian-centric, and congregation-centric paradigms. Herzog’s (2020) meta-analysis of 30 years of scientific studies of religion is relevant. Beyond the limitations of a study based on bibliographic sources (JSSR)3 and databases (ARDA),4 along with their biases, which the work aimed to address, the results are conclusive. They indicate that centrism remains, although perhaps to a lesser extent than in the previous decades, with the notable exception of a remaining inequality in the geographic scope.

Within the religious tradition and geographical scope there is a clear persistent inequality. The concentration of research data are mainly from Northern America and Western Europe, and are primarily focused on Christianity. This tendency is valid even for studies on Africa and Asia.5 Within the total of 191 publications that were systematically sampled for the Africa and Asia geo-tags, at least 133 were overtly focused on Christianity or on Christianity and other religions (70%). However, if we consider minority religions and some traditions not included in the WRP, we find that only 23 are focused on them (12%), while 168 include analyses involving Christianity and Islam, major world religions (88%).

Regarding social studies of religions, beyond sociodemographic studies, in the prevailing conventional sociological or political science approaches, although also in many historiographical approaches, there is a privilege given to world religions as the scope of analysis or analytical focus. Anthropological studies are a separate case. It is a social science that has moved beyond ethnocentrically evolutionism or original positivism, toward more comprehensive, contextual, structural, or ethnographic studies, including decolonial ones, where the relevance of local religions, generally associated with ethnic groups, has sought to be observed free from those etic or external categories laden with disqualifying preconceptions.

These efforts are valuable in incorporating diversity and addressing the new dynamics imposed by globalization and social change in the 21st century on world religions. However, such approaches often perpetuate a view that has the WRP as its background, in other words, a Eurocentric and neocolonial perspective, when they do not adopt critical distance or explicitly reflect on the problem.

4. Key Concepts, Approaches and Methodology

Our observation of the primacy of the WRP as such is not enough to advance toward a new way of understanding religious diversity within the framework of what is called multiple modernities. In proposing an alternative perspective, we are going to begin addressing some issues that have been advanced by both decolonial social sciences and theorizing about the center–periphery dynamics in the study of religious phenomena. These theoretical-epistemological antecedents will provide us with analytical tools for the analysis of the Axial theory.

Certainly, our problem extends beyond the manifestations of world religions, that are often viewed, as mentioned, through the lens of Christianity (Masuzawa 2005). This recognition encompasses both a process of subjectivization/individuation (Beyer 2020) and a simultaneous process of re-institutionalization/deinstitutionalization of religious expressions. In some regions of the planet that trend toward subjectivization, it is linked to the processes of “individuation” within the secular era (Taylor 2007) that depend on the type of “modernity” that is developing in that area (e.g., megacities, industrialization, more technologically advanced countries). Furthermore, it acknowledges that these religious and spiritual options are not merely diverse but also “lived” (McGuire 2008; Ammerman 2016; Morello 2020), with their dynamics continually diversifying and evolving into the future.

The observed changes, both historically and socially, including unprecedented diversity in the globalization of the 21st century (Beyer 2006; Beyer and Beaman 2019), challenge traditional theories of secularization, which confine religion to the private sphere and fail to recognize the complex interrelations between religion and society (Casanova 2018). As Peter Berger contends in his review of classic theories of secularization within the context of diverse modernities, we must transition toward a new paradigm capable of accommodating two pluralisms: the coexistence of different religions and the coexistence of religious and secular discourses (Berger 2014).

In Latin America, discussions have begun regarding the necessity of a critical analysis that addresses the unique processes of modernization, paving the way for theoretical approaches centered on multiple modernities (Mallimaci 2017; Parker 2019). Distinct articulations between the public and private spheres are emerging, contrasting with developments in other regions and continents within the context of a paradoxical globalization that simultaneously homogenizes and diversifies (Oro and Steil 1997; Beyer 2006; Frigerio 2020). Consequently, we will examine how a critical re-evaluation of the theory of multiple modernities (Beriain 2002, 2014; Offutt 2014; Göksel 2016; Preyer and Sussman 2016; Sinai 2020) and its theoretical and conceptual implications for analyzing the religious landscape in Latin America, Africa and Asia shed light on current processes of intercontinental religious diversification.

4.1. Efforts from a Decolonial Approach

While acknowledging the influence of Western-centric perspectives, the recent scientific literature attempts to provide a more comprehensive understanding of religious diversity. A different atmosphere prevails in the social sciences of religion in Latin America, Europa and Asia. Critical and decolonial approaches, whether explicit or implicit, are valued, with a strong emphasis on understanding various forms of religious and spiritual expression. A review of the literature, meetings, and conferences in the last few years within the context of critical social science approaches reveals a much greater focus on this religious and spiritual diversity.

Not all are systematic efforts to “deconstruct” the conventional concept of religion, although there are attempts to surpass the current paradigm. Some currents in sociology and anthropology, from decolonial perspectives (Martins 2016), aim to develop new concepts, including epistemic views from the Global South, to research cultural and religious diversity.

There are also efforts by academics to innovate in the teaching of religions in order to overcome classical approaches. For example, in Brodd and his colleagues’ (Brodd et al. 2022) Invitation to World Religions, lengthy chapters are included on Indigenous religions in North America, African religions and their relationships with colonial powers, their forms of resistance, and the analysis not only of beliefs, rituals, images, and practices but also of all religions as ways of life. Other similar efforts intend to problematize religion and world religions (Robinson and Rodrigues 2022). However, critical reflection on the problematic nature of the concept of world religions and the religious colonialism that is part of its history is insufficient. On the other hand, quantitative research centers on religions like the PEW Research Center are now striving to understand that religious dynamics can be better captured when they focus on spiritualities rather than conventionally “religious” practices (Alper et al. 2023).

A notable characteristic of these studies is that they focus on peripheral religious realities. The aim is to rescue expressions marginalized by modernity but emerging in the present as modalities of postcolonial meaning alternative to religious institutions and modern-industrial rationality (De la Torre 2019). There are many studies that could be mentioned, and we do not have the space here. Studies like those early works conducted by Parker (1996) on all kinds of popular religious expressions in Latin America or more recently by Wright (2018b) are examples of this trend. They analyze syncretisms, magic, folk, Indigenous or African worldviews and traditions, Eastern religions, spiritualism, anthroposophy, Rosicrucianism, the New Age movement, esoteric tourism, Santo Daime, neo-esotericisms, and Latino-Zen Buddhism. These are realities that have either been unnoticed or undervalued by social scientists of religion.

These expressions of religious peripheries are also those of social peripheries (Ameigeiras 2020). Studies in migrant neighborhoods on the outskirts of Barcelona conclude that “it is in the margins of the city that religious effervescence overflows, outside the limitations of previously established centralities” (Moreras 2017).

4.2. Religious Center and Periphery

From a theoretical standpoint, it is important to clarify that we are using the concepts of center and periphery in their sociological sense (as per Shils 1975) rather than in their socioeconomic sense, as in the classical proposal of Prebisch (1948), which was later widely employed in dependency theory.6 Moreover, our use of these concepts applies systematically to the study of religious production. We intend to expand the scope, seeking to understand the complexity of religious phenomenon beyond Bourdieu’s theory of the religious field (Bourdieu 1971). Our conceptualization stems from the study of phenomena within popular religions, Indigenous religions, and heterodox productions of the masses, and, as we will see, from a critical considerations about the Axial theory.

From a perspective that redefines the religious phenomenon—in a decolonial perspective that transcends a Christian-centric and Eurocentric approach—we must distance ourselves from the usual definitions of the religious and understand that the concept itself is problematic (Alatas 1977; Cox 2016; Schilbrack 2022). The religious phenomenon is socially constructed, experienced, practiced and understood in multiple ways and under patterns that can be highly divergent, making it a difficult phenomenon to study. It always has specific and local variations.

From this perspective, we understand the religious center to be the process of production and the products of socio-religious work elaborated by a specialist apparatus of the sacred (Bourdieu 1971), generally constituted in a church-type organization (Durkheim [1912] 2013) that produces doctrines, morals, beliefs, practices, objects, and salvific goods and is followed by a circle of close faithful called “practitioners”. It is an ideal type of a form of symbolic-religious production with legitimating power, often under a male authority structure within the framework of a patriarchal culture. It generally relies on social and political power, encouraging the spread of its beliefs and practices universally. This is what we can call an official and/or conventional religion, which characterizes recognized world religions, although it should be remembered that Eastern religions must be analyzed differently in order to overcome Christian-centrism.

On the other hand, we understand the religious periphery as the set of processes, productions and symbolic-ritual expressions that escape the “religious center”. This includes two different and complementary realities, which are being produced beyond, thanks to, or resisting conventional religious centers: (a) the (more or less) autonomous self-production through which the mass of faithful generate their lived religions, and (b) the non-conventional religious forms, generally ethnic or local organic religions. Generally, in religious peripheries, the role of women is greater.

Our definition of the periphery is not topological, nor primarily spatial or geographical, but rather sociocultural and existential (Rosolino 2017). In the religious context, it refers to the periphery of symbolic-religious production, which is subjected to official production and disparaged by both the religious center and the conventions of the dominant society. Peripheries will always be seen as “divergent”, even when they are situated and reproduced immediately adjacent to the center and power. For example, “indigenous religions” or ethnic religions in Latin America, Africa, or Asia are generally viewed with suspicion by the population, if not subjected to disqualifying prejudices.

Usually, between the center and the periphery, there is a relationship of coloniality and dependence, but peripheries also have relative autonomy for their own religious productions. This relationship is not dual but multiple and dialectical, with interactions that are back and forth, complementary, co-relative, or dominating/resistant, involving vertical and/or transversal exchanges subject to varying degrees of tension and/or conflict.

4.3. Dynamics, Mobility, Religious Conversions, and Migrations

With respect to religious change and diversification, the dynamic is often focused in terms of, on the one hand, conversion, and on the other hand, migration. These processes, which are intensified by the paradoxical globalization (Ritzer and Dean 2019) or glocalization (Robertson 2018) of societies with their positive and negative flows, certainly stimulate and invigorate religious diversity and increase religious peripheries.

However, as Algranti and Setton (2008) argue, an adequate analysis requires taking into account the overlap of these two drivers of change. On the one hand, conversion, which not only allows for the creation of an army of missionaries but also drastically changes religious affiliations. On the other hand, these dynamics (conversion and migrations) relax real and symbolic boundaries, erasing strong affiliations, increasing spaces for the circulation of people, beliefs, and symbolic goods, transforming routes and daily and historical trajectories (Sanchez et al. 2017), and decreasing the influence of canonical doctrines from the religious center. Cases of diaspora rituals such as the celebration of the Peruvian Lord of Miracles in Barcelona (Fernández-Mostaza and Muñoz Henriquez 2018) reveal the coexistence of tensions between unity and differences, integration and resistances in migratory contexts amid center–periphery dynamics. All of this leads to the instability of strong religious identities, which is precisely considered a risk for the religious center, prompting them to reaffirm their doctrinal and disciplinary controls by reactivating fundamentalism or extremism. Thus, the religious field and the center–periphery dynamics are being reconfigured in their dynamics.

4.4. A Theoretical Methodology

The primary methodology employed in this article is theoretical research (Swedberg 2014) combined with qualitative analysis (Creswell and Poth 2018). The theoretical and conceptual reflections presented herein are based on a dual approach. Firstly, we have compiled information, data, and analyses gathered over nearly three decades. This includes observation of direct and indirect sources from historical, anthropological, and sociological perspectives. It focuses on the study and interpretation of the religious phenomenon, more focused on Latin America but also observing African and Asian realities. Secondly, we explore key aspects of the theoretical discourse surrounding theories of multiple modernities and religions (Beriain 2002; Possamai 2009; Parker 2019). The corresponding debate involves various positions, authors, and controversies and has been ongoing for some time.

Many of the ideas discussed in this article have previously undergone examination and critique by sociological colleagues at recent conferences or have been the subject of academic scrutiny through prior publications. At this juncture, our focus acknowledges a particular locus of our writing as we contemplate global phenomena through the lens of the religious and cultural landscape of the Latin American continent, in which we have conducted empirical research for a long time and which constitutes a significant portion of the Global South.

4.5. A Decolonial Sociological Approach

We have explicitly stated the georeference of our approach and contextualized it. Now it is necessary to clarify that, from an epistemological standpoint, this work adopts a decolonial sociological approach in the broader context of Latin American cultural studies over recent decades (Ávila-Rojas 2021; De la Torre 2022; Boidin 2023). We do not align ourselves with any specific decolonial current; rather, we embrace the epistemic endeavor to break free from Eurocentric and colonialist thought structures, critically challenging the dominant scientific paradigms of modern Western capitalism. Our intention is not to engage in a debate regarding the subjects, identities, and political or ideological functions associated with decolonialism’s dialogue with anti-colonial positions. Furthermore, our proposal takes distance from African anti-colonial currents or European critical post-colonial currents (Boidin 2023), as this endeavor would necessitate a separate study.

When we assert that the decolonial approach involves relinquishing the primacy of the religious center in favor of religious peripheries, we are not advocating for a normative or inherently ethical or political preference. It is crucial to acknowledge that not all religious centers have historically supported colonialist policies. Indeed, there have been periods in history where movements originating from the religious center have prophesied against injustice, advocating for the liberation of the oppressed, and in recent centuries, serving as advocates for human dignity, peace, harmony, and the establishment of just and democratic orders. Similarly, the preference for peripheries stems from an analytical and phenomenological necessity to explore religious and spiritual diversity in all its density and dimensions rather than from an ethical or political standpoint. History often illustrates how various religious, spiritual, and mystical expressions from the peripheries have not contributed to liberation but rather to religious alienation, serving as instruments of domination and legitimization of unjust systems.

Therefore, the examination of religious protest and liberation movements, whether emanating from the center or the peripheries, must consider the socio-historical circumstances, contexts, and junctures surrounding them for a crucial comprehensive analyze. Hence, we endeavor to justify the recognition of this diversity as a phenomenon originating from the peripheries, necessitating a decolonial approach (De la Torre 2022) that shifts the focus away from the center, contrary to what the WRP does.

5. Results of the Theoretical and Epistemic Analysis: The Theory of Multiple Modernities and the Axial Age

The increasing religious diversity in Latin America, Africa and Asia can be comprehended through the convergence of various phenomena, albeit it must undoubtedly also be considered as an integral part of a global phenomenon. In investigating this phenomenon, Eisenstadt’s theory of multiple modernizations (Eisenstadt 2000, 2003, 2013) emerges as pertinent. Its validity has been affirmed as it enables us to challenge traditional evolutionary theories, such as linear and Eurocentric modernization, which would imply a direct transition to secularization. Additionally, it facilitates an understanding of the socio-historical, ideological, and institutional contexts that have engendered various forms of modernity worldwide since the advent of the modern era. This theory not only proves beneficial for comprehending contemporary changes in religions worldwide but also encourages a deeper exploration of its implications for the theory of secularization (Smith and Vaidyanathan 2011). The logical consequence of applying this theory of multiple modernities to religion is that there are and will continue to be various processes of “multiple secularizations” (Martin 2005) and multiple “resacralizations” (Offutt 2014). For example, as the paradoxical processes of modernization advance, Pentecostalism and charismatic movements increase in the Global South (Vijgen and van der Haak 2018). Indeed, secularization must be conceived as a complex and nonlinear process of transformations experienced by all societies immersed in modernization processes (Bruce 2011), although each in its own way and with its own nuances. Globalization leaves a variety of traces that affect different religious trajectories (Oro and Steil 1997).

Beyond Eisenstadt’s contributions to sociological theory and his debates with structural functionalism, rational choice theory, and neo-Marxism concerning key concepts such as norms and institutions, charisma and institutions, culture and religion, structure and agency, his global vision of multiple modernities shows a challenging path for global sociological analysis.

At this point, what are the multiple modernities we are referring to? Eisenstadt (2003) primarily recognizes those he calls axial civilizations: those linked to the great civilizations generated in the Axial Age. These include Western modernity, China, India, and Islam. To these, we must add the “non-axial” civilization of Japan. Europe and North America are classified as Western civilization. According to the author, the major transformations from modernity onwards have generated a second global Axial Age: the current modernity as a distinctive civilization (Eisenstadt 2003, p. 493ff). The analysis of axial civilizations focuses on the division of labor and the institutionalization that made possible the formation of a strong social and cultural center. The transcendental visions and the center formation were developed and articulated by emerging elites, especially intellectual elites.

Thus, the theory of multiple modernities divides the planet into different civilizations, and the distinctive element that sets one apart from another turns out to be nothing less than the world religions to which they are tributary: Judeo-Christianity, Buddhism and Hinduism, Confucianism and Taoism, Shintoism and Islam. Hence, the theories of WRP and the theory of multiple modernities are deeply theoretically, historically, and culturally associated.

In fact Eisenstadt’s theory of multiple modernities is founded on a specific understanding of the Axial Age (Eisenstadt 1982; Bellah and Joas 2012; Beriain 2014), a period marked by significant intellectual and institutional transformations in several civilizations. The inclination toward focusing on elites and the center (Shils 1972, 1975) and their role in social change, particularly during the transition from pre-Axial societies to Axial civilizations, despite its analytical contribution, overlooks crucial dynamics in shaping religious diversity, especially center–periphery dynamics.

5.1. The Axial Age and the Key Role of the New Elites

As is commonly known, the theory of the Axial Age was initially proposed by Karl Jaspers (1948) and further developed in sociology by Shmuel Eisenstadt (2000, 2003). It posits that human history witnessed an extraordinary period marked by significant advancements in philosophy, religion, and intellect between the eighth and third centuries BCE. This era, known as the Axial Age, saw the emergence of new elites who played a pivotal role (Pérez-Argote 2017) in shaping these developments. These elites included Jewish prophets, Greek philosophers, Chinese literati, Hindu Brahmins, Buddhist Sangha, (and later, Islamic ulamas). These intellectual groups were responsible for introducing new transcendent concepts.

Max Weber ([1921] 1958, [1915] 1959, [1922] 1965, [1922] 1971), whose ideas greatly influenced Jaspers and Eisenstadt, focused his attention on the intellectual leaders of the world’s major religions rather than on popular religious practices or local charismatic leaders. Weber was primarily interested in the processes of rationalization and the transformation of charisma into established hierarchies. According to historian David Christian (2004), Jaspers’ concept of the Axial Age is closely linked to the rise of the first “universal religions”, coinciding with the emergence of the initial universal empires and international trade networks during the first millennium BCE. It is relevant to note that these new elites, which transform centers and generate universal religions, are predominantly male and patriarchal.

5.2. The Axial Age and the Emergence of Dualism

The theory of the Axial Age posits a significant leap in human comprehension of truth around 500 BCE, characterized by a distinct recognition of a dichotomy between two realms: the “mundane” and the “transmundane”. This perception of division was accompanied by a focus on the existence of a superior transcendent moral or metaphysical order beyond any specific mundane reality (Eisenstadt 2003, p. 199). During this period, both the theory of transcendence and that of two worlds were formulated. Thus, the advancements during the Axial Age can be delineated by two principal aspects: universalization and distancing (Assmann 2012).

Universalization denotes the acknowledgment of absolute truths applicable across all epochs and cultures, involving reflexivity, abstraction, theoretical formulation, systematization, and second-order thinking. Distancing entails the introduction of ontological and epistemological distinctions, such as those between eternal and temporal worlds, spirit and matter, and the critical evaluation of the given in light of the true.

In contrast, pre-Axial religions, or local traditions, upheld a homologous (non-dualistic) perception of the relationship between the transcendent and mundane orders, prioritizing symbolic structures that mirrored the mundane world (Eisenstadt 2003).

A pivotal role in the transition to universal dualism was assumed by scriptures and orthodoxy. Writing, within religious contexts, enabled religions to assert their truth over mythical claims by grounding truth in revelation, which was then formalized through canonization. All the major world religions, including Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism, Confucianism, Taoism, and Islam, are founded on a canon of sacred scriptures (Assmann 2012). Thus, the shift to universalization entailed a departure from local or ethnic religions and the creation of universal religions, commonly referred to as world religions.

The transition from local or ethnic religions to world religions necessitated a move from oral traditions and rituals to textual continuity, resulting in a comprehensive reorganization of cultural memory. This transition fostered the emergence of transcultural and transnational world religions, which became the predominant center for new practices, narratives, and identities. The canon served as a new transethnic homeland and a transcultural tool for formation and education. The canonization of scriptures not only enables the existence of world religions but also serves to differentiate them from ethnic and local religions. Scriptures create a universal narrative that displaces and deterritorializes local narratives.

In the sociology of religion, the emergence of universal world religions is typically linked to the growth of cities and states capable of producing surpluses. Religious work has been associated to factors such as the division of intellectual and practical labor, urban-rural differentiation, the desacralization of nature, and the rationalization and moralization of life (Marx and Engels [1932] 1968; Weber [1921] 1958, [1915] 1959, [1922] 1965, [1922] 1971; Houtart 1989; Bourdieu 1971). However, from a cultural and religious perspective, uprooting and writing play pivotal roles. The term world in world religion precisely signifies the capacity for uprooting. World religions transcend territorial, political, ethnic, and cultural boundaries, being both transnational and trans-territorial. Consequently, they acquire the ability for mission, conversion, and diaspora (Assmann 2012, p. 271).

When this capability is combined with dominant power, it becomes a contributing factor to colonialism. The notion of true religions has often been utilized to distinguish major religious traditions from other practices considered to be magic, superstition, or false religions. Within the context of colonial expansion, this distinction has been employed as a tool of cultural and religious imposition. The supremacy of Christianity, particularly in supporting the colonial expansion of the West, has made the Christian faith a fundamental component of Western expansion.

5.3. Privilege of the Center and World Religions

Eisenstadt’s explanation of the Axial Age focuses on the organization of social centers, contrasting with pre-Axial Age societies that integrated sacred, primordial, and charismatic elements to construct a social order. Social centers, as delineated by Shils (1975), were organized around power, typically colonial or imperial, emphasizing their symbolic differentiation from the periphery. These centers served as primary sources for the charismatic resolution of tensions and the construction of cultural and social orders (Eisenstadt 2003, p. 204).

The formation of centers and the establishment of Great Traditions are interconnected processes. The development of centers is evident in monumental architectural works and the reverence for scholarly books and codices. However, Great Traditions extend beyond this, organizing and creating symbolic distinction, thus establishing a fundamental semantic distance from the Small Traditions of the periphery (Eisenstadt 2003, p. 205). Consequently, a hegemony of the center is established, reinforced by the Great Traditions as symbols legitimizing central powers. Eisenstadt acknowledges the hegemony of the center and its impact on the relationship between the Great and the Small Traditions. This hegemony permeates the periphery, leading to attempts to assimilate or dissociate the Great and Small Traditions, resulting in conflicts, rebellions, and the institutionalization of order by the center.

From this context of colonial expansion, the concept of world religions emerges to denote those major religious traditions with a global presence, such as Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism. However, due to the influence of the underlying model of Judeo-Christianity, there exists a biased conventional interpretation of Eastern religions like Buddhism, Hinduism, Taoism, Confucianism, and Shintoism, which fails to fully acknowledge their distinctive features and unique belief systems (Masuzawa 2005). Anyway, the primacy of world religions has led to a minimization of local and secondary traditions in favor of these major religions.

Returning to our author, it is important to note that Eisenstadt adopts a functionalist perspective here, which recognizes the functional conflict of different forms of institutionalization (Preyer and Sussman 2016) but does not address the socio-structural conflict of surplus societies as a central factor in social dynamics. He focuses on how the center institutionalizes order rather than on how conflict shapes historical dynamics, thereby downplaying the center–periphery dialectic.

6. Discussion: The Neocolonial Bias of Axial Theory and the Effort to Overcome It

The multiple modernity theory represents a daring departure from conventional sociological paradigms. By recognizing the diverse pathways to modernity taken by different civilizations, a rich terrain for inquiry that transcends the limitations of Eurocentric perspectives is opened. Notwithstanding, this perspective still proves insufficient to delve into the complexities of religious diversity.

As we have seen in the first part of this paper, the theory of the WRP remains valid and continues to be predominant today, and its alignment with the theory of the Axial Age is evident. These approaches, as we have seen, still remain West-centered and Christian-centric, continuing to fuel interpretations about civilizational diversity at the core of multiple modernities.

The perspective of the WRP traces the origins of stablished religions exclusively to the Middle Eastern region, encompassing Mesopotamia and Egypt, as well as Zoroastrianism, before their further development in Greece and Rome. From a broader global standpoint, it focuses on the Great Traditions of world religions, such as Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, Christianity, and later on Islam, along with the principal religious traditions of China and Japan (Dowley 2018).

It becomes necessary to move away from this predominant approach, but it is not a task easy to deal with. The specialists in religious studies grapple with how to speak and teach about the various manifestations of religion, diversity, comparisons, and how to delve into particularities without falling into the trap of resorting to the predetermined categories of the WRP.

We cannot un-invent world religions because they exist, but they can be redefined and relativized as social forms that are shaped by religious centers and their respective peripheries. In the contemporary world, diversity is present, and the public becomes aware of the similarities and differences between religions. The elaboration of nuanced discourses on concurrent religions and dialogues in intercultural and interreligious contexts should be the subject of study for the social sciences of religion. The tensions between religious centers and between centers and their peripheries imply contacts, borrowings, mixtures, conflicts, and alliances, and they must also be the object of research.

To undertake this conceptual shift, it is imperative to (a) acknowledge the dynamics and conflicts between the center and the periphery; (b) recognize the religious and spiritual innovations emerging from the peripheries; and (c) acknowledge the multitude of diverse religious expressions, extending beyond orthodox canons.

Therefore, advocating for the peripheries and advancing a decolonial perspective becomes necessary. Why? Because the emphasis on the center, the elites, and their influence on social change during the transition from pre-Axial societies to Axial civilizations perpetuates a neocolonial viewpoint. This viewpoint, we argue, remains implicit in the WRP understanding of world religions and their hegemony today.

We must remember that such a perspective disregards crucial aspects of historical religious phenomena and their contemporary manifestations. These include the real mosaic of religious diversity, the dialectic between elite and popular religions, and the contrasts between institutionalized and lived religions (Tweed 2015). Additionally, it overlooks the significance of the role of women in religious histories, the diverse existence of alternative and dissenting religious movements, and the differentiation between religion and spirituality.

It is imperative to consider all these factors to grasp the complex realm of religious diversity (Beyer and Beaman 2019) within the context of multiple processes of modernization. In order to advance within this critical and cutting-edge perspective, revisiting a collection of conceptual and theoretical understandings and assumptions is necessary. Taking the first steps in that direction, we propose three primary theoretical theses:

Three theoretical theses around the idea of a center–periphery religious dialectic to understand contemporary religious diversity.

First: The religious center’s prominence depends on the peripheries.

The relationship between the religious center and the periphery is one of interdependence, where the center’s prominence and legitimacy stem from its connection to the periphery. Central religions are characterized by their complexity and sophistication, which are defined by their distinction from myriad subordinate religious and spiritual expressions. While central expressions may orbit around, mutually reinforce, and sustain dominant central power (often maintaining ties and alliances fraught with tension), their religious authority and impact are contingent upon the support, vitality, adherence, and/or dissent of the multitude of believers and expressions originating in the peripheries.

Throughout religious history, it is evident that world religions have assimilated unique transnational and transcultural attributes that remain powerful or influential, insofar as aligning themselves with imperial and colonial centers. Conversely, the heterogeneous expressions of the masses and local and ethnic religions contribute to a centrifugal dynamic in which the relevance of the periphery lies, either in non-subordinate expressions or in subordinated expressions with relative autonomy.

Second: In the religious center, hierocracy tends to predominate, while lived religious expressions tend to predominate in the peripheries.

The religious center is marked by a hierocracy that, albeit not always effectively, prioritizes authority, canonical doctrine, and institutional control. Here, the concept of hierocracy is an ideal type associated with Weberian sociology of domination (Sathler 2016). Weber ([1922] 1971); (see also Murvar 1967) describes a hierocracy as a system where religious or priestly power is organized in a rational and bureaucratic manner. He also defines it as the religious authority’s ability to govern, backed by the exclusive right to manage sacred or religious values by distributing or withholding them. We must emphasize that, although Weber did not analyze it, hierocracies are also characterized by the exercise of male domination (Bourdieu 1998).

Conversely, the peripheries foster their own dynamics, emphasizing lived religious expressions (McGuire 2008; Ammerman 2016; Morello 2020; Juárez et al. 2022) that encompass personal experiences and diverse manifestations of faith and spirituality within individuals and communities. Religious peripheries in some cases tend to vindicate the feminine, the body, and sexual diversities, which generally challenge the patriarchal religious order.

As a result, the periphery fosters greater individual agency, encourages creative interpretations, and facilitates the proliferation of spaces where personal and communal faith and spirituality can be experienced and expressed with a relative degree of freedom. This creativity encourages the emergence of syncretic and heterodox expressions of different types that from time to time—depending on the historical and cultural contexts—tend to bypass hierocratic controls. Many spiritualities that have recently emerged, in some regions where there is greater religious freedom, are eco-spiritualities and eco-feminists (Ottuh 2021).

Third: A comprehensive appreciation of religious diversity requires consideration of the center–periphery dialectic.

To fully grasp the intricacies and breadth of religious diversity (Beyer and Beaman 2019), one must delve into the dynamic interplay between dominant religious institutions (the center) and marginalized or alternative forms of faith (the peripheries). It is imperative to closely examine this dialectical relationship between elite/popular religions or institutionalized/lived religions (Possamai 2015).

The implication of these assertions is that genuine understanding of religious diversity stems from adopting a diversity paradigm. Approaches that inherently favor a unified view of the phenomenon, such as the WRP, risk falling into the trap of the epistemic fallacy of partial truth. While they may contain elements of truth, they obscure fundamental aspects of the phenomenon, leading to a form of deception through omission.

Conversely, the emerging paradigmatic perspective advocates for a diversity paradigm that encompasses the entire spectrum of religious and spiritual expressions, transcending conventional and dominant narratives. It represents a novel paradigm concerning religious and spiritual phenomena, offering a global and holistic viewpoint that is gaining traction by embracing diverse realities and the multitude of religious experiences. This perspective contributes to a comprehensive understanding of religious diversity.

Beyond common perceptions that obscure them, these genuinely diverse religious and spiritual peripheries have been recognized within academic circles in recent decades. However, studies in the fields of history, sociology, and anthropology of religions, while acknowledging this deep diversity, often fail to situate it within a broader theoretical and critical framework. By neglecting to account the privileging of the colonial center and failing to explicitly address this diversity as inherently complex, these studies inadvertently perpetuate the notion that the observable reality of world religions—the first layer—represents the pinnacle of legitimacy and diversity—a hegemonic stance. In narrowly focusing on localized, ethnographic studies, they mask the fact that they are primarily exploring a secondary and underlying layer of religious expression, one that resides deeper within the socio-symbolic fabric of societies. In doing so, they unintentionally elevate world religions to a position of supremacy, echoing the limitations of the WRP and relegating the true, complex diversity that emanates from the peripheries to a secondary status, often characterized as “folkloric”, “exotic”, and alternative; in other words, a secondary order of reality.

7. Conclusions: Analyzing Religious and Spiritual Diversity within Multiple Modernities

The complexity of religious diversity in the contemporary world, Asia, Latin America, and Africa, extends beyond the narrow scope proposed by the WRP, which often emphasizes only a handful of major world religions. Merely attributing diversity to the Axial Age and its manifestation in the various modernities shaped by these Great Traditions overlooks the deeper layers of religious and spiritual peripheral expressions, some of them coming from a millennia-old process. This is especially actual when, following the Axial theory, we overemphasize the role of the religious center and its hierocracies and canonical narratives, we do not take into account the center-periphery dialectic in religious production, and we forget the lived religions in the multiple peripheries.

Many of these world religions have been intertwined with colonialism (Gascoigne 2008; Strathern 2016), leaving a lasting epistemological partiality that tends to overlook diversity. The dominant narrative of the WRP manifests “the coloniality of knowledge” (Lander 2000); in other words, it reproduces the unequal power of knowledge production. This coloniality is more than a matter of scholars not being exhaustive enough in their research but rather of the great hegemony of an epistemological perspective, which overlooks a vast production of symbolic-religious expressions. In terms of the current debate in the social sciences about religion and diversity, the sociology of religion contributes beneficially when it undertakes the path to decolonization.

Following that path, what unfolds when we venture beyond the confines of the conventional paradigm is myriad forms of symbolic-religious-spiritual expression. The decolonial and phenomenological perspective observes and scrutinizes lived religions, fluid spiritualities that thrive ubiquitously: whether official, alternative, or syncretic and miscellaneous. Thus, the dialectic driving the narrative of contemporary religious history, between the conspicuous and identifiable religious centers and the multifaceted expressions emanating from the peripheries with which these centers interact, is unveiled. The religious phenomenon fully emerges, revealing the collective effervescences described by Durkheim ([1912] 2013) and the diverse spiritualities (traditional or post-traditional) (Heelas 2008; Wright 2018a; Camurça 2018) that subtly populate the contemporary religious landscapes.

The peripheries, in the context of multiple modernities, encompass thousands of mystical, spiritual, neo-magical, or syncretic practices, some of them stemming from healing and divination, either traditional or post-religious pursuits. These quests may be supported by churches or may dissent from or resist religious centers. Ordinary citizens from the margins or even across borders promote expressions that challenge canonical categories. Usually, the conventional WRP view of religion either will label them as non-believers (or nones) (Lee 2016; Da Costa et al. 2021) or they will be characterized as non-practicing, dissident, folk, popular, magical, esoteric or neopagan religious forms.

In this article, we have not delved into the numerous works that initiate studies on diversity from post-conventional perspectives. Nor have we analyzed the management of religious diversity, a matter of religious freedom, as both topics deserve much more attention than we can give them in this space. We have focused on a specific topic: the need to understand religious diversity in terms of the center-periphery dynamics.

Numerous spaces, interfaces, dialogues, intersections, conflicts, and tensions emerge, prompting an epistemological shift (De la Torre 2022) in our understanding of religious phenomena within the context of multiple modernities. Just as modernity is not solely a Western phenomenon, having historically originated in the West, religion is not incompatible with modernity and can adopt various forms of engagement with it (Kamil 2018).

Religious diversity is burgeoning globally within the multiple modernities worldwide and especially in the Global South. Certainly more research is needed on the religious phenomenon through the lens of diversity within a decolonial perspective. Advancing this type of approach becomes imperative to move beyond Eurocentrism and foster a more horizontal, universal and all-encompassing understanding (Sunar 2016). The results of our theoretical analysis of the WRP and the supporting Axial Age theory indicate that several centrist trends persist and continue to plague the scientific study of religion, highlighting the need for more critical attention.

Funding

This research was funded by Universidad de Santiago de Chile, Project: AYUDANTE_DICYT, Código 032491PG_Ayudante-VRIIC.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All the data used are available in the same text or in the Appendix A and Appendix B.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Examples of websites with information about world religions (all accessed during April–May 2024):

Appendix B

Table A1.

Religious tradition in the Africa–Asia JSSR articles (2010–2020).

Table A1.

Religious tradition in the Africa–Asia JSSR articles (2010–2020).

| Religious Tradition | # | # +Xn | # −Xn |

|---|---|---|---|

| Christianity | 40 | 40 | 0 |

| Protestantism | 19 | 19 | 0 |

| Catholicism | 23 | 23 | 0 |

| Islam | 43 | 16 | 27 |

| Judaism | 14 | 7 | 7 |

| Buddhism | 12 | 6 | 6 |

| Atheism | 6 | 2 | 4 |

| Mormonism | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| Hinduism | 5 | 4 | 1 |

| Folk Religions | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| Taoism | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| New Religious Movements | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Confucianism | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| African Spirituality | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Unitarian Universalism | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Mysticism | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Baha’i | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Jainism | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Shintoism | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Sikhism | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Neo-Paganism | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 21 total religions | 191 | 133 | 58 |

Note: +Xn: Christianity included. −Xn: Christianity excluded. Source: Compilation from JSSR (2010–2020) in Herzog (2020, p. 18).

Notes

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion (JSSR). |

| 4 | Association for Religious Research Archives (ARDA). |

| 5 | See Table A1 in Appendix B. |

| 6 | Certainly, we do not here enter into the debate surrounding dependency theory, which has extensively employed the concepts of the center and periphery. Well known are its more radical authors, Andre Gunder Frank and Samir Amin, as well as its more moderate ones, Cardoso, Faletto, and Sunkel. Our use of the center–periphery dialectic refers to the dynamics of religious production. |

References

- Alatas, Syed. 1977. Problems of Defining Religion. International Social Sciences Journal 29: 213–34. [Google Scholar]

- Algranti, Joaquín, and Damian Setton. 2008. Las formas de la periferia religiosa. Estudio comparado sobre los modos de pertenecer en el campo judaico y neopentecostal en Buenos Aires. Paper presented at the IX Congreso Argentino de Antropología Social, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 5–8 August 2008; Posadas: Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales—Universidad Nacional de Misiones. [Google Scholar]

- Alper, Becka A., Michael Rotolo, Patricia Tevington, Justin Nortey, and Asta Kallo. 2023. Spirituality among Americans; Pew Research Center, December. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2023/12/07/spirituality-among-americans/ (accessed on 7 May 2024).

- Ameigeiras, Aldo. 2020. Religión, Migración y Desigualdad en la Periferia Urbana del Gran Buenos Aires. Buenos Aires: CONICET, vol. 774, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman, Nancy T. 2016. Lived Religion as an Emerging Field: An Assessment of Its Contours and Frontiers. Nordic Journal of Religion and Society 1: 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assmann, Jan. 2012. World Religions and the Theory of Axial Age. In Dynamics in the History of Religions between Asia and Europe. Edited by Volkhard Krech and Marion Steinicke. Leiden: Brill, pp. 255–72. [Google Scholar]

- Ávila-Rojas, Odín. 2021. ¿Anti o decolonialismo en América Latina? Un debate actual. Sociedad y Economía 44: e10210669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellah, Robert N., and Hans Joas, eds. 2012. The Axial Age and Its Consequences. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Peter L. 2014. The Many Altars of Modernity. Boston and Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Beriain, Josetxo. 2002. Modernidades Múltiples y encuentro de civilizaciones. Revista Paspers 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beriain, Josetxo. 2014. Imaginarios postaxiales y resacralizaciones modernas. Revista Latina de Sociología RELASO 4: 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, Peter. 2006. Religion in Global Society. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer, Peter. 2020. Religion in Interesting Times: Contesting Form, Function, and Future. Sociology of Religion 81: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, Peter, and Lori G. Beaman. 2019. Dimensions of Diversity: Toward a More Complex Conceptualization. Religions 10: 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boidin, Capucine. 2023. Qu’est-ce que les «études décoloniales» latino-américaines? Décoloniser! Notions, Enjeux et Horizons Politiques. 2023. Available online: https://www.ritimo.org/Qu-est-ce-que-les-etudes-decoloniales-latino-americaines (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- Borup, Jørn, Marianne Qvortrup Fibiger, and Lene Kühle, eds. 2020. Religious Diversity in Asia. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1971. Génese et structure du champ religieux. Revue Francaise de Sociologie 12: 295–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1998. La Domination Masculine. Peris: Éditions du Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Boyon, Nicolas. 2023. IPSOS, Global Religion 2023. Ipsos. Available online: https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2023-05/Ipsos%20Global%20Advisor%20-%20Religion%202023%20Report%20-%2026%20countries_0.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2024).

- Brink, Terry L. 1995. Quantitative and/or Qualitative Methods in the Scientific Study of Religion. Zygon 30: 461–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britannica. 2024. Religion. Encyclopedia Britannica. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/topic/religion (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Brodd, Jeffrey, Layne Little, Bradley Nystrom, Robert Platzner, Richard Shek, and Erin Stiles. 2022. Invitation to World Religions, 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, Steve. 2011. Secularization: In Defence of an Unfashionable Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, Steve. 2018. Researching Religion: Why We Need Social Science. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Camurça, Marcelo. 2018. ‘Espiritualidades’, redes religiosas New Age no Brasil: A Linguagem franca das terapias, oriente, esoterismos e energias. In Religiones en cuestión: Campos, Fronteras y Perspectivas. Edited by Juan Cruz Esquivel and Verónica Giménez. Buenos Aires: Fundación CICCUS, pp. 237–52. [Google Scholar]

- Carden, Paul. 2020. World Religions Made Easy. Peabody: Rose Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, José. 2018. The Karel Dobbelaere Lecture: Divergent Global Roads to Secularization and Religious Pluralism. Social Compass 65: 187–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, David. 2004. Maps of Time. An Introduction to Big History. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- CIA. 2024. The World Factbook. Travel the Globe with CIA’s World Factbook. Available online: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/ (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- Cotter, Christopher R., and David G. Robertson, eds. 2016. After World Religions: Reconstructing Religious Studies. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, James L. 2016. Foreword: Before the ‘After’ in ‘After World Religions’—Wilfred Cantwell Smith on the Meaning and End of Religion. In After World Religions: Reconstructing Religious Studies. Edited by Christopher R. Cotter and David G. Robertson. London and New York: Routledge, pp. xii–xvii. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, John, and Cheryl Poth. 2018. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. Los Angeles: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Da Costa, Néstor, Gustavo Morello, Hugo Rabbia, and Catalina Romero. 2021. Exploring the Nonaffiliated in South America. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 89: 562–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davie, Grace. 2002. Europe: The Exceptional Case—Parameters of Faith in the Modern World. New York: Orbis Books. [Google Scholar]

- De la Torre, Renée. 2019. Reseña del libro Periferias sagradas en la modernidad argentina. Revista Cultura & Religión 13: 122–26. [Google Scholar]

- De la Torre, Renée. 2022. Algunas rutas para descolonizar la investigación internacional: Desandando el poder en sentido contrario. In La Horizontalidad en las Instituciones de Producción de Conocimiento: ¿Perspectiva o Paradoja? Edited by Sarah Corona. Ciudad de México: Gedisa, pp. 51–84. [Google Scholar]

- Dowley, Tim. 2018. Atlas of World Religions. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, Émile. 2013. Les Formes Élémentaires de La Vie Religieuse. Paris: PUF. First published 1912. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstadt, Shmuel N. 1982. The Axial Age: The Emergence of Transcendental Visions and the Rise of Clerics. European Journal of Sociology 23: 294–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenstadt, Shmuel N. 2000. Multiple Modernities. Daedalus 129: 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstadt, Shmuel N. 2003. Comparative Civilizations and Multiple Modernities. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstadt, Shmuel N. 2013. Latin America and the Problem of Multiple Modernities. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales, Nueva Época 58: 153–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eller, Jack David. 2022. Translocal or ‘world’ religions. In Introducing Anthropology of Religion. Culture to the Ultimate, 3rd ed. Edited by Jack David Eller. New York: Routledge, pp. 201–27. [Google Scholar]

- Esquivel, Juan Cruz. 2017. Transformations of Religious Affiliation in Contemporary Latin America: An Approach from Quantitative Data. International Journal of Latin American Religions 1: 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquivel, Juan Cruz. 2018. Abordajes cuantitativos en los estudios de la religión: Desafíos teórico-metodológicos y alcances de la investigación. In Religiones en Cuestión: Campos, Fronteras y Perspectivas. Edited by Juan Cruz Esquivel and Verónica Giménez. Buenos Aires: Fundación CICCUS, pp. 125–32. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Mostaza, M. Esther, and Wilson Muñoz Henriquez. 2018. A Cristo moreno in Barcelona: The Staging of Identity-Based Unity and Difference in the Procession of the Lord of Miracles. Religions 9: 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigerio, Alejandro. 2020. Encontrando la religión por fuera de las ‘religiones’: Una propuesta para visibilizar el amplio y rico mundo que hay entre las ‘iglesias’ y el ‘individuo. ’ Religiao e Sociedade 40: 21–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, Aaron M. 2022. Introduction to World Religions. A Clear Path. Kendall Hunt Publishing. Available online: https://wvu.khpcontent.com/introreligions/page/unit1pg1 (accessed on 9 May 2024).

- Gascoigne, John. 2008. Religion and Empire, an Historiographical Perspective. Journal of Religious History 32: 159–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göksel, Oğuzhan. 2016. In Search of a Non-Eurocentric Understanding of Modernization: Turkey as a Case of ‘Multiple Modernities’. Mediterranean Politics 21: 246–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heelas, Paul. 2008. Spiritualities of Life. In The Oxford Handbook of the Sociology of Religion. Edited by Peter Clarke. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 758–83. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog, Snell Patricia. 2020. Global Studies of Religiosity and Spirituality: A Systematic Review for Geographic and Topic Scopes. Religions 11: 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinnells, John. 2010. The Penguin Handbook of the World’s Living Religions. London: Penguin Editors. [Google Scholar]

- Hourmant, Louis. 2021. Introduction aux Religions (Modules rédigés par IERS), 2018, IESR—Institut d’étude des religions et de la laïcité, mis à jour le: 17/05/2021. Available online: https://irel.ephe.psl.eu/ressources-pedagogiques/fiches-pedagogiques/introduction-aux-religions-modules-rediges-iers (accessed on 9 May 2024).

- Houtart, François. 1989. Religión y Modos de Producción Precapitalistas. Madrid: Iepala. [Google Scholar]

- Jaspers, Karl. 1948. The Axial Age of Human History: A Base for the Unity of Mankind. Commentary 6: 430–35. Available online: https://commentary.org/articles/karl-jaspers/the-axial-age-of-human-historya-base-for-the-unity-of-mankind/ (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Johnson, Todd M., and Brian J. Grim, eds. 2018. World Religion Database. Leiden/Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Juárez, Nahayeilli, Renée de la Torre, and Cristina Gutiérrez. 2022. Religiosidad bisagra: Articulaciones de la religiosidad vivida con la dimensión colectiva en México. Revista de Estudios Sociales 82: 119–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamil, Sukron. 2018. Is Religion Compatible with Modernity? An Overview on Modernity’s Measurements and its Relation to Religion. Insaniyat: Journal of Islam and Humanities 2: 85–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lander, Edgardo, ed. 2000. La Colonialidad del Saber: Eurocentrismo y Ciencias Sociales. Perspectivas Latinoamericanas. Buenos Aires: CLACSO. [Google Scholar]

- Larousse. 2024. Religion. Encyclopedie Larousse. Available online: https://www.larousse.fr/encyclopedie/divers/religion/87050 (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Latinobarómetro. 2020. Opinión pública latinoamericana. Latinobarómetro. Available online: https://www.latinobarometro.org/lat.jsp (accessed on 23 January 2022).

- Lee, Lois. 2016. Non-Religion. In The Oxford Handbook of the Study of Religion. Edited by Michael Stausberg and Steven Engler. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 84–96. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Xiaobiao, Qinghe Chen, Luyao Wei, Yuqi Lu, Yu Chen, and Zhichao He. 2022. Exploring the trend in religious diversity: Based on the geographical perspective. PLoS ONE 17: e0271343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallimaci, Fortunato. 2017. Modernidades religiosas latinoamericanas. un renovado debate epistemológico y conceptual. Caravelle 108: 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maoz, Zeev, and Errol A. Henderson. 2013. The World Religion Dataset, 1945–2010: Logic, Estimates, and Trends. International Interactions: Empirical and Theoretical Research in International Relations 39: 265–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, David. 2005. On Secularization: Towards a Revised General Theory. Aldershot: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, Bruno Sena. 2016. Antropología y poscolonialismo. La memoria postabismal. Revista Andaluza de Antropología 10: 102–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, Karl, and Friedrich Engels. 1968. L’idéologie Allemande. Paris: Editions Sociales. First published 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Masuzawa, Tomoko. 2005. The Invention of World Religions or, How European Universalism was Preserved in the Language of Pluralism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, Meredith. 2008. Lived Religion, Faith and Practice in Everyday Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morello, Gustavo. 2020. Una Modernidad Encantada. Religión Vivida En Latinoamérica. Córdoba: Editorial Universidad Católica de Córdoba. [Google Scholar]

- Moreras, Jordi. 2017. Las periferias religiosas: Allá donde la ciudad pierde (¿o recupera?) su fe. In Antropologias en Transformación: Sentidos, Compromisos y Utopias, Paper presented at the XIV Congreso de Antropología, Valencia, Spain 5–8 September 2017. Edited by Teresa Vicente, MaríaJosé García and Tono Vizcaino. Valencia: Universitat de Valencia, pp. 785–98. [Google Scholar]

- Murvar, Vatro. 1967. Max Weber’s Concept of Hierocracy: A Study in the Typology of Church-State Relationships. Sociological Analysis 28: 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nongbri, Brent. 2013. Before Religion. A History of a Modern Concept. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Offutt, Stephen. 2014. Multiple Modernities: The Role of World Religions in an Emerging Paradigm. Journal of Contemporary Religion 29: 393–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oro, Ari Pedro, and Carlos Alberto Steil, eds. 1997. Globalização e Religião. Petrópolis: Vozes. [Google Scholar]

- Ottuh, Peter. 2021. Spiritual Ecofeminism: Towards Deemphasizing Christian Patriarchy. Abraka Journal of Religion and Philosophy 1: 1. Available online: https://abrakajournal.com/index.php/ajrp/article/view/5/3 (accessed on 9 May 2024).