Abstract

This study conducts a comparative analysis of Buddhist sacred structures throughout Asia, focusing on the historical development, regional disparities, and the cultural sinification process of stūpas, caityas, and pagodas. Specifically, it delves into the origins, definitions, and terminologies of early Buddhist monuments, such as stūpas/mahācetiyas and caityas/cetiyas, emphasizing their Indian origins. The research further explores the adaptation and reinterpretation of these original Indian concepts as they spread to East Asia, morphing into new forms, such as pagodas and Buddha halls. It examines the subtle shifts in terminology and the altered meanings and functions of these monuments, from their Indian origins to their sinified representations in East Asia. The transformation of Indian Buddhist monuments through local culture and technology into East Asian architectural forms is investigated, offering a detailed perspective on the dynamic transformation of sacred spaces in Buddhism. This illustrates the religion’s adaptability and integration with the local cultures of ancient East Asia. By analyzing the terminologies and symbolic meanings associated with the architectural transition from stūpa to pagoda, the study argues that sinicized ritual spaces in East Asia have adopted architectural types from pre-Buddhist traditions to represent Indian spaces, thereby highlighting the nuanced changes and the continuous adaptation of sacred Buddhist architecture.

Keywords:

Buddhist monument; stūpas; mahācetiyas; cetiyas; caityas; pagodas; vernacularization; sinification 1. Introduction

The dwelling places of the Buddha are depicted in two distinct categories: imagined and actual. These representations manifest in various forms of art, such as bas-reliefs, paintings, and statues found in monasteries. Early Buddhist literature and architectural representation in Buddhist compounds show an array of structures with various shapes and functions, including stūpas, mahācetiyas, cetiyas/caityas, topes, dagobas, and pagodas. In these depictions, imagined dwellings are often idealized or symbolic representations, reflecting the spiritual significance and teachings of Buddhism. They do not correspond to physical structures but serve as metaphors or icons in Buddhist art and scripture.

Conversely, actual dwellings comprise concrete structures built for religious purposes, including various types of stūpas and pagodas (referred to in some traditions as ta, lou, ge, ci, and dian) that vary in architectural style, size, and design across different regions and periods. Each type—whether a stūpa, mahācetiya, or pagoda—carries a unique cultural and religious significance and serves as a place for meditation, worship, and storing sacred relics. This dichotomy between imagined and actual dwellings in Buddhist art and literature reflects the rich tapestry of Buddhist architecture and spiritual tradition, highlighting how art and physical structures have been combined to communicate the Buddha’s teachings and legacy.

This study delves into the transition of these tangible spaces from simple physical entities to complex symbols that embody meditation, enlightenment, teachings, and the Buddha’s death. In addition, it investigates how Buddha’s monuments, initially defined within the Indian context, were transformed into their sinified counterparts. Through the study of East Asian literary sources, this study analyzes how elements like stūpas, mahācetiyas, and pagodas were reinterpreted and adapted to fit into the local cultural and religious fabric (Pollock 1996, 1998).

The role of monuments in Buddhist practice expanded from stūpas to pagodas, undergoing a reinterpretation through pre-Buddhist architectural forms to echo the life and events of the Buddha. Employing critical analyses by scholars such as Bareau (1955), Sircar (1962), and Schopen (1988, 1989), this study aims to clarify the concepts and definitions associated with Buddhist monuments, such as stūpas/mahācetiyas, caityas/cetiyas, pagodas, pagodas with halls, and Buddha halls. In particular, Bareau’s analysis provides a comprehensive overview of the Buddha, who was first described as a lokottara (otherworldly being) and an ārya (saint), perfectly pure (anasrava) in spirit and body. The term lokottara implies that the Buddha lived above the world. The historical Buddha was considered a nirmāṇakāya (response body). The notion of a supernatural Buddha was then developed, attributing a body, power, and infinite longevity to the Buddha (Bareau 1955). Sircar (1962) laid important groundwork regarding the concrete definition of dhātu-vara as the Buddha’s stūpa with relics. Schopen’s work in the late 1980s considers the Buddha and his reliquaries as a token of a present being, not a reminder of the past and dead Buddha (Sircar 1962). Thus, while drawing on such established scholarship, this study introduces innovative approaches to examine shifts in the terminology and definitions used in the context of pre-Buddhist traditions, such as Brahmanism, Hinduism, and Taoism, which diverge from Buddhist scriptural descriptions, thus extending the dialogue beyond the existing frameworks established by earlier works.

This article argues that, despite regional variations in technology and materials used in reconstructing monuments and ritual spaces, pre-Buddhist architectural styles were strategically assimilated to recreate significant sites from Buddha’s life during the adaptation processes in India and East Asia. Moreover, by elucidating certain scholarly viewpoints, this research contributes to bridging existing gaps in the academic study of Buddhist architectural and spiritual traditions.

2. Sacred Buildings in Early Buddhism

Giuseppe Tucci defined stūpa as a Sanskrit term dating to the Vedas that originally referred to the top or upper portion of a head (topknot hairstyle) or tree, pillar, or something heaped up—a summit (Tucci and Chandra 1988, pp. 11–17). Stūpa relates to the construction of Vedic altars (Kramrisch 1946), which comprise a round altar that symbolizes the terrestrial world and a square altar on the top of the round body that indicates the celestial. Caitya, rendered into Pali as cetiya and elsewhere in Southeast Asian countries as ceti, was another Sanskrit term that referred to a different type of Buddha monument—memorial mounds and any object of veneration (Tucci and Chandra 1988). In Ceylon, the most common term comparable to stūpa is dagoba, derived from the Sanskrit dhātugarbha (an element or relic storehouse).

In India, Buddhist stūpas differ depending on their functions and forms. They were called stūpas, topes, and caitya in Sanskrit and mahācetiyas, thupas, and cetiyas in Pali (Kramrisch 1946). In Chinese, zhidi 制底 is derived from the Pali term cetiya, meaning a funeral pyre of the Buddha or Saint; the zhidi contains sacred relics of the Buddha or Saint like thupas and stūpas. Zhidi is a transliteration in such Mahāyāna Chinese texts as the Suvarṇaprabhāsa (uttamarāja)-sūtra (Golden Light sutra), Saddharma puṇḍarīka-sūtra (Lotus sutra), and various kinds of Dharani-sutras. The Avataṁsaka sūtra (Flower Garland sutra) and Lalitavistara-sūtra (Play in Full sutra) characterized the zhidi as tamiao 塔廟, signifying a sinified term that combined a pagoda with a hall. From mahācetiyas to pagodas, these structures served as significant symbols of sacred locations and extraordinary events, commemorating four to eight pivotal sites associated with the Buddha’s life journey, from his birth to his Mahāparinirvāṇa (the attainment of nirvana).

The terms stūpa, caitya, and thupa are used interchangeably based on locality, time, and the choice of Buddhist literature/sutras by monastic intellectuals and laypeople. Stūpa was used in various places, although it was not accepted in South India (e.g., Salihundam, Bavikonda, Nāgārjunakoṇḍa, Amaravati, and Kanaganahalli) or in Nepal (e.g., Swayambhunath). They were never called stūpa but always mahācaitya/mahācetiya, meaning “great caitya”. Only the four earthen mounds located along the axis of the street network in Patan, about five kilometers from Kathmandu, are not called caitya but thudva (thu was possibly borrowed from Pali) (Gutschow et al. 1997). Even Buddhist monuments at Nāgārjunakoṇḍa were called mahācetiya rather than stūpa and cetiya instead of caitya, while caitya was popularly used to refer to northern Indian Buddhist monuments. Therefore, caitya, cetiya, and thudva represent the same structures and are almost synonymous.

Sircar (1962) and Schopen (1988) suggested new definitions of dhātu. Sircar (1962) noted that dhātu-vara means Buddha’s relics. The English word “relic”, stemming from the Latin verb relinquere, originally meant something leftover or remaining behind; however, here, it refers to a stūpa built on Buddhist relics, which were usually called dhātugarbha (Sircar 1962). In the Nāgārjunakoṇḍa inscriptions, the redactor did not consider the dhātu or relic as a piece or part of the Buddha but as something that contained or embodied the Buddha himself, in which the Buddha was wholly present. However, if the Buddha was present in the relic, it could not represent a reminder of the past and deceased Buddha, but Buddha as a living being (Schopen 1988). This indicated a change in the concept of Buddha in Mahāsaṅghika schools. By themselves, Nāgārjunakoṇḍa monuments such as mahācetiyas and cetiyas indicate the incarnations of the living Buddha—cottages in which he lived during his lifetime, relics after his death, and shrines for worship (Kim 2024).

Therefore, stūpa/mahācetiya, caitya/cetiya, zhidi, thupa, dagoba, and pagoda imply an incarnate body—a dwelling, relic, and shrine of Buddha—where devotees held him with respect. The construction and combination of stūpa with caitya were ultimately active trials to seek merit-making for attaining rebirth into the Buddhist well-being and pure lands, demonstrating “a means to an end”. They continue to serve as sacred places for pilgrims reminiscent of activities such as teaching, nirvana, meditation, and miracles (Kim 2011, 2021).

3. Characterizing the Shrine-Temple Architecture in Early Indian Buddhism through the Lens of Stūpa/Mahācetiya and Caitya/Cetiya

3.1. Stūpa/Mahācetiya as the Shrine-Temple

The term “stūpa” (Pali thupa, Anglo-Indian tope), derived from the root “stup”, meaning “to heap”, is essentially a funeral mound or tumulus. Traditionally associated with funerals, these mounds often contain ashes and remnants from funeral pyres. The practice of building stūpas over physical relics predates Buddhism. Coomaraswamy (2003, p. 30) interpreted the stūpa not only as a funeral mound but also as a symbol of Buddha’s parinirvāṇa. Similarly, Havell (1920, p. 4) traced its origins to Indian burial practices, likening the stūpa to an “Aryan royal tomb”. Foucher (1960) also supported the view that the stūpa evolved from Brahmanical tumuli. Smith further emphasized this by likening stūpas to primitive tombs used in Indian burial practices, such as the Iron Age Cairns in the south and tumuli near Nandanagarha in Champāraṇa district (Foucher 1905, 2010; Marshall 1918; Przyluski 1920; Dutt 1962, 1984; Cousens 1982).

The hemispherical structure of stūpas likely developed from ancient earthen funeral mounds (śmaśāna) used in Vedic cremation rituals. This aligns with Przyluski’s (1920) study of Brahmanical śmaśāna, indicating the deep cultural and religious evolution of these Buddhist monuments (Majumdar et al. 1951, p. 488). The Mohesengzhilu 摩訶僧祇律 (Anonymous n.d.a) clarified that stūpas, as symbols of Buddha, need not contain relics. This text differentiates between stūpas (with relics) and cetiyas (without relics), underscoring their importance as symbols of Buddha’s life events, regardless of their relic status. Therefore, while śmaśāna practices were tied to concerns about pollution and, hence, situated away from villages, stūpas, especially those at sites such as Nāgārjunakoṇḍa and Amaravati, often included chambers for interring bones and other items, indicating a divergence from traditional Brahmanical customs.

In the Brahmin belief system, crematoriums and cemeteries were perceived as unlucky and impure, with rituals that involved turning to the left (prasavya). Contrastingly, stūpas or cetiyas, symbols of purity and good fortune, were commonly constructed around villages (Kosambi 1962; Ru 2006, pp. 172–73). In the Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra, Kāśyapa’s act of turning right (pradakshina) after cremation signifies purification. The Yourao fota gongde jing 右繞佛塔功德經states that circumambulating a stūpa to the right brings merits and benefits (Anonymous n.d.d). Despite positive symbolism, Brahmanism followers derogatorily referred to stūpas as eduka or rubbish structures, possibly owing to their popularity (Kim 2015).

The connection between stūpas and Vedic altars is evident in their references to trees and sacrificial poles, aligning with caitya and cetiya halls (Irwin 1980). Additionally, dolmens (stone circles) are associated with the origins of Hindu temples as altars and huts during Vedic times, a fact preserved in manuals of astrology and architecture (Meister 1988). Kramrisch (1946) argued that stūpa architecture resulted from the fusion of ancient Vedic altars and cairns. The original meaning persisted and reinforced the context when the Vedic altar found its Buddhist or Jain equivalent in the stūpa, serving as both a funeral altar and cairn. It serves as the socle, typically circular but occasionally square, within which the cairn rises like a monumental solid bubble, symbolizing the world egg (anda). Alternatively, Kramrisch (1946) stated that the stūpa is primarily a funeral mound rooted in Brahmanical traditions (Hazra 2002).

The raised platform, originally associated with the practice of erecting a cairn over the ashes of the deceased, served both ritualistic and commemorative purposes. The cairn became known as a harmikā when placed on top of a stūpa dome, reflecting the assimilation of Brahmanical traditions with the primitive practices of Jains and Buddhists.

The names of the components within the stūpa are closely associated with those of Vedic altars. According to the Mahāvaṃsa (an ancient historical record of Ceylon), a pillar, referred to as a yūpa, is to be erected at the stūpa site (Wilhelm 1996, p. 225). Early stūpas were relatively simple mounds of earth but gradually evolved into larger, dome-shaped structures. Additional elements were consistently incorporated until the stūpa assumed its “classic” form, featuring a cubical stone surrounded by a vedika, derived from the fences used around Bodhi trees during the Vedic era. In Sanchi and Amaravati, stūpas were designed with access points through four gates (toranas) situated in each cardinal direction. However, in contrast to stūpas in northern India, mahācetiyas, meaning great stūpas in Andhra Province, such as Nāgārjunakoṇḍa, Jaggayyapeta, Garikapadu, Ghantasala, Peddaganjam, and Amaravati, displayed a unique structural feature, with platforms known as āyakas projecting toward the cardinal directions, where worshippers circumambulating could place their offerings. These platforms were encircled by tall pillars made of sculpted and adorned stone, referred to as āyaka-stambhas. The āyaka was commonly found in stūpas of the Mahāsaṅghika and related sects, whereas the Mahīśāsaka sects did not typically incorporate it into the exterior of their stūpas. The presence of āyakas was relatively uncommon at Buddhist sites such as Salihundam (Srikakulam), Ramatirtham (Vizianagaram), and Sankaram (Visakhapatnam) in Andhra Pradesh.

The presence of a pole in stūpas can be traced back to tree cults that commemorated Buddha’s enlightenment under the Bodhi tree. Early depictions of stūpas often showed that they were crowned by trees with parasol-shaped leaves (Harvey 1991, pp. 77–79; Kim 2011). This suggests that stūpa worship, as evidenced by the bas-reliefs, remains similar to that in Kanaganahalli and is equivalent to the worship of the bodhi-gara (tree house), which became a symbol referring to the Buddha. Furthermore, tree worship was closely associated with rituals aimed at invoking rain and ensuring successful harvests, often under the protection of Yakṣa and Yakṣiṇī, minor deities associated with the air, forests, and trees (Coomaraswamy 1993, p. 120; Devi 2002). This indicates that the worship of the Bodhi tree may have been prevalent in Buddhist monasteries.

The large hemispherical dome (anda), which houses precious relics, might be the most significant component of the stūpa. The dome also supports a square-railed platform or throne (harmikā), which, akin to a cool summer chamber atop a building, symbolizes the Bodhi tree shrine. From the center of this harmikā rises a parasol (cattrāvali) attached to a pole (yasti) (Harvey 1990, p. 87). Havell (1920) suggests that the solid structure of brick or stone in stūpas may have originated from the domical huts constructed using bamboo or wooden ribs and that the earliest stūpas could have been inspired by the huts or tents of the Aryan chieftains, later reproduced in Vedic funeral rites as temporary abodes for the spirits of the deceased (Havell 1920, p. 18). Originally, the stūpa was akin to a building known as kuṭī, as the root meaning of kut signifies curvature. A kuṭī represents a circular dome surmounted by a pinnacle or finial (Coomaraswamy and Meister 1988, p. 18).

The Mahāvaṃsa, a historical chronicle from ancient Ceylon, offers comprehensive details on the planning and building phases of stūpas. It highlights the importance of orienting the construction site according to the four cardinal directions and a central point. The initial phase involves identifying the center, followed by erecting pillars to mark the gate locations and the path for circumambulation. The chronicle narrates that the king, upon seeing the pillar erected at the intended site of the stūpa, recalled an ancient tradition that brought him joy. After consulting with a thera (bhikkhū in Pali), he designated a specific area for the mahācetiya (stūpa) to ensure proper placement of the foundation stones. The king then had eight silver vases placed for relics, along with eight distinct bricks laid out separately. He directed an official to select one brick as the foundation stone, which was subsequently set on the eastern side atop fragrant clay. All the builders then constructed a robust platform, both circular and square in shape, from clay and bricks, along with an ambulatory path and steps oriented towards the four cardinal directions (Kim 2015; Wilhelm 1996, pp. 187–209).

Initially, stūpas functioned as burial mounds containing the relics of the Buddha. From the third century onwards, as they began to feature independent imagery, most stūpas transitioned into integral components of temple worship halls. Specifically, they evolved into focal points for religious devotion, constructed not only to house Buddha’s relics but also to enshrine other sacred relics or to denote particular holy locations. Over time, the simple act of dedicating a stūpa, irrespective of whether it housed relics, came to be viewed as an act of merit.

3.2. Caitya/Cetiya as the Shrine-Temple

The term "cetiya" originally signified a sanctuary or shrine. In Pali and Prakrit, this term traces back to a sacred tree associated with Yakṣas, as described in the Mahābhārata. This setup often included a stone table or altar under the tree, which Coomaraswamy (1993) described as the “haunt of Yakṣa”. In Ceylon, similar structures are known as dagobas, and in Myanmar, they are called shwedagon, both terms suggesting a “relic chamber”. The term “caityagṛha”, which has become prevalent in academic discussions in recent decades (Burgess 1883), was commonly used in Prakritic inscriptions at early cave sites under the variant cetiyaghara. Both caityagṛha and cetiyaghara denote a building or shrine that encloses a sacred object or a focal point of worship, fulfilling the same symbolic role as a stūpa.

The term cayan is derived from caitya or cetiya, which is in turn derived from citi, which means funeral pyre or “to collect or pile up”. It also suggests a tumulus or earthen mound placed over the bones or ashes of the departed “saint”, and invariably, the entire mound was covered by a roof (Agrawala 2003, p. 124). The pre-Buddhist practice was to burn the dead, collect the remains and ashes, and either plant a tree, raise an earthen mound or install a wooden post at the burial ground. This ritual was called the caitya vartan. The raised earthen mound at the site is the caitya (Pant 1976, p. 27), regarded as either a funeral pyre or tomb, which is considered eerie because of its association with death (Guruge 1991, p. 266; Dutt 1984). The Ramayana mentions similar approaches associated with fear of caityas: “When Rama on his return inquired about the caityas”; “Ravana looked as fearful as the śmaśāna caitya”. Therefore, the above reference seems to indicate that the caitya was also linked to śmaśāna cults for preserving bones and ashes and commemoration, as well as a sacred worship place (Pant 1976, p. 30). This notion in the Ramayana is reminiscent of the caitya stūpa. The caitya linked with śmaśāna continued at the time of Buddha’s Nirvana: as the dead body was burned at the caitya, it subsequently became a place of worship and commemoration. Ananda referred to three kinds of cetiyas, all non-Buddhist in character: (1) Śarīrika cetiya (shrines containing physical relics, called dhātu, of a Buddha or an arhat, that refer primarily to the bones and teeth left after cremation); (2) Paribhogikā cetiya (shrines of things he used, bowls, robes, and copies); and (3) Uddesika cetiya (shrines indicating the nature of a Buddha, reminders, representations, aniconic portrayals, or images) (Shah 1952; Harvey 1990; Huntington 1990, p. 405; Tambiah 1982).

The stūpas/cetiyas, as well as pagodas/halls, represent events in the lives of historical Sakyamuni. Likewise, they demonstrate the legitimacy of their own locus of Buddhism by creating sacred sites associated with Buddha’s previous lives, relics, and other cultic objects such as the Buddha’s begging bowl, footwear, and turban (Kuwayama 1987, p. 298; Taddei 1990, pp. 298, 311; Shinohara 2003, pp. 68–107).

The term citi or citya, meaning “to collect”, is associated with the Yajna Sthana or fire altar. The Mahabharata has a reference to yūpa, yajna, and sacrifices. The bones are collected and piled up later, an act called cayana (meaning heaping up; a layer of fuel; heap) (Macdonell 1929, p. 92), namely, the collection of bones and ashes. Therefore, the caitya is related to the Vedic Yajna cults and the practice of collecting bones and filling them under a structure or a place for worship or commemoration. They display some theoretical and purposive similarities with Buddhist stūpas. The caitya with yūpa was known as caitya-yūpa; thus, it may be said that the Buddhist caitya-stūpa could be the modified and enhanced form of the Vedic yūpa (Pant 1976, p. 28).

Both the Ramayana and Mahabharata refer to the caitya as a sacred place. The Ramayana refers to it as caityaprasada and caityagṛha, a place that represents temples of ancestral deities of the Raksasas. Terms such as prasada and guha are used to qualify the caitya as significant by distinguishing between the two types of caityas. Meanwhile, caityas in northern India did not necessarily imply construction but rather encompassed trees, rocks, and other objects of worship. The Sthānāṅga Sūtra mentions the worship of caitya trees by each of the ten classes of Bhavanvasi gods (Pant 1976, p. 25). The term caitya is even used twice to denote the trees that are worshiped, specifically caityavṛkṣa and samūla caitya. Kautila and Manu also mentioned the caityavrksa, associating it with a burial ground. This Vedic tradition of caityavṛkṣa finds continuity in Buddhist tradition through the concept of the “bodhi-tree” (Guruge 1991, p. 265).

Although the terms caitya/cetiya and stūpa/mahācetiya are often interchangeably used to denote monuments, cenotaphs, temples, and shrines that include a caitya or dhātugarbha, the term caitya/cetiya specifically denotes a fundamental component of a shrine designed for worship. The usage of caitya extends beyond shrines to include sacred trees, holy sites, and other religious edifices. Coomaraswamy (1992) defines caitya broadly as “something constructed or heaped up” and connects it to the derivative “citya”, which refers to an altar or fire altar. In a similar vein, the Buddhist stūpa may be linked to earlier traditions of constructing raised funeral mounds or fire altars at places of honor and veneration. Thus, caitya/cetiya likely represents the original form of the stūpa, symbolizing commemoration, praise, and worship.

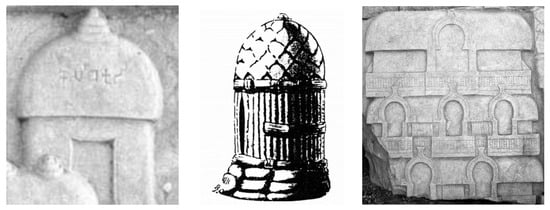

Within the constraints of monastic buildings, the cetiya/caitya became a dwelling similar to the huts or chambers in which Buddha taught and resided, reminding us of gandhakuṭī (a hall of fragrance in the Jetavana) as one of the representative houses (Das et al. 1902; Tarannatha 1970, p. 320). Gradually, they were transformed into shrines or temples as doctrinal reminders of asceticism while merging with vernacular architectural types such as kuṭī, vihāra, prāsāda, paṇṇa śālā [Figure 1], and bhavana (bhavanam). Their meaning and function expanded from a cell of ascetic friars to a temple for gods. Unlike vihāra and kuṭī, cetiyas were reminiscent of the sublime events or loci of Buddha and his disciples (Foucher 1903; Lipsey 1977; Gnoli 1978; Coomaraswamy 1992; Meister 2007; Oldenberg 2007). As Peter Harvey said, “They act as reminders of a Buddha or saint: of their spiritual qualities, their teachings, and the fact that they have actually lived on this earth. This, in turn, demonstrates that it is possible for a human to become a Buddha or a saint” (Harvey 1984, p. 68). Therefore, monuments such as stūpas/cetiyas and Buddha halls/pagodas were built to ensure that Buddha remained active. They were arranged in the center, with shrines for bodhisattvas situated in their surroundings (Hirakawa 1963, pp. 57–106).

Figure 1.

Kuṭī (Meister 2007, p. 8; Kim 2011) (Left), Panna-sala (Coomaraswamy and Meister 1988, p. 100; Kim 2011) (Middle), and Vihāra (Meister 2007, p. 9; Kim 2011) (Right). The author has obtained permission from the copyright holder.

Objects imbued with symbolic meaning became central points of reverence for monks, nuns, and devotees during their pilgrimage to holy sites. The practice of venerating relics and caityas invokes the tangible aspects of Buddha’s personality and deeds. Stūpas/cetiyas and Buddha-pagodas/Buddha-halls are regarded as both shrines and tombs—places where devotees engage in pūjā rituals, create memorials, and undertake pilgrimages to accrue merit, prosperity, and happiness.

These symbolically significant pilgrimage sites are potent places where the structures built to enshrine them evolved into temples. In East Asia, the names and images from the Indian tradition were adapted and localized; for example, Mount Putuo (Poṭalaka) became associated with Guanyin (Avalokiteśvara), Mount Wutai with Wenshu (Mañjuśrī), and Mount Emei with Puxian (Samantabhadra) (Gimello 2006). The reverence for images, scriptures, and relics—items personally associated with Buddha and his disciples—became a focal point of devotion and gradually extended to other Buddhist sites along the routes to India and near the capitals of Buddhist kingdoms.

3.3. Borrowing Caityas and Cetiyas in Pre-Buddhist Buildings

As described in the Mahāsaṅghika Vinaya, the Mahesangzhilu indicated that caityas mark important places related to Buddha’s life, such as his birth, enlightenment, turning of the wheel of law, and nirvana. Additionally, caityas may be associated with locations featuring a bodhisattva image, the caves of pratyeka buddhas, or the footprints of Buddha. They may have included Buddha flower canopies and offering equipment (Daoshi 668).

The monastic code of Mahāsaṅghika regarded cetiyas as shrines or places to commemorate significant events in Buddha’s life. These Buddhist shrines were consistently referred to as cetiyas, and a specific type of stūpa is known as the mahācetiya. Evidence from Mulasarvastivadin Vinaya, another monastic code of one of the early Buddhist sects, and Divyāvadāna (Buddhist Avadāna tales) suggests the existence of a relic cult that did not involve the traditional stūpa. These texts mention caitya and cetiya in this context. Divyāvadāna’s Toyika story, summarized by John Strong (1999), portrays Buddha encountering a shrine dedicated to a local divinity in the village of Toyika. The Brahmin plowing nearby referred to the shrine as a cetiyatthana, a caitya place, indicating that the cetiya structure had already been used as a shrine for commemoration, worship, and praise during Buddha’s lifetime rather than as a fence or tree.

Mohesengzhilu records the construction of a votive stūpa for monk Kaśyapa, which Buddha himself raised. This stūpa had a bottom platform enclosed by railings on all four sides, with two tiers in cylindrical form and square-shaped projections. A spire with disks adorned the top, which stood at an impressive height. The railings were made of bronze, and the construction took seven years, seven months, and seven days. King Krki also erected a stūpa for the Buddha, featuring niches on its four sides, along with figures of lions, elephants, and various paintings (Anonymous n.d.a).

The Śarīra (relics) of Tathāgata were also objects of worship, representing relics consistent with those of living beings, reflecting the wisdom of enlightenment. Shimoda (1997) argued that these relics align with the concept of the Buddha dhātu mentioned in the Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra, suggesting that the dhātu serves as both a relic and stūpa, thereby emphasizing the living presence of the Buddha as an object of worship.

Schopen supported this interpretation, drawing insights from the inscriptions in Nāgārjunakoṇḍa and suggesting that the dhātu or relic contained or enclosed the Buddha himself, marking a significant shift in the concept of Buddha within the Mahāsaṅghika schools (Schopen 1989, 1997, p. 91). Schopen indicated that, in this context, the term “cetiya” or ”caitya” does not refer to a stūpa but has a broader meaning of shrine. He also clarified that bhuto does not mean “become like” but simply “becomes”, correcting Conze’s translation to convey that a spot of earth becomes a caitya (shrine). This interpretation suggests that the presence of a Dharmaparyāya (dharma teaching), such as the Prajñāpāramitā (Perfection of Wisdom), in a specific place sacralizes that place in a unique way, distinct from the sacralization achieved by the presence of a stūpa (Conze 1975, pp. 149–52).

Considering Schopen’s interpretation, Nāgārjunakoṇḍa’s monuments, including stūpas and cetiyas, were seen as living Buddhas embodying his presence. This perspective extends to various architectural structures such as cottages, relics, and shrines. Schopen’s ideas play a significant role in explaining the emergence and evolution of Buddhist buildings, bridging the gap between vernacular buildings and local architectural styles. Thus, Shimoda and Schopen shed light on the profound significance of relics and their connection to the living presence of Buddha in Buddhist worship and architecture.

Schopen’s (1989) analysis of the Pali Vinaya highlights a significant omission: the lack of explicit rules concerning stūpas or cetiyas, which he interprets in two distinct ways. Firstly, he proposes that the absence of specific rules within the Khandhaka (the second book of the Theravadin Vinaya Pitaka) is noteworthy. This might suggest that such rules were originally included in the Pali Vinaya but later removed. Supporting this idea, texts like the Mahāparākramabāhu-Katikāvata (the Great Law Code of Parākramabāhu), Visudhimagga (the first book of the Theravadin Vinaya Pitaka), and Suttavibhanga (Division of Rules) hint at an original inclusion of these rules. Schopen suggests that their absence could be attributed either to accidental omission over time or deliberate exclusion in subsequent editions. Additionally, Schopen notes the peculiar absence of the term “stūpa” in the Aparamahāvinaseliyas inscriptions at Nāgārjunakoṇḍa, contrasting with its frequent use in other Indian Buddhist contexts. This absence suggests possible regional variations in terminology.

More broadly, he observes that Buddhist shrines were often termed cetiyas, especially in regions influenced by pre-Buddhist architectural forms. This suggests a significant integration of local architectural styles into Buddhist religious structures, whereby structures such as the mahācetiyas at Nāgārjunakoṇḍa are viewed not just as reliquaries but as embodiments of the Buddha’s living presence (Schopen 1988).

In refining his views, particularly between 1988 and 1989, Schopen critiques previous interpretations, notably Bareau’s reading of Vasumitra (a Buddhist monk of the Sarvastivada in the 2nd century CE), arguing that cetiyas and mahācetiyas, influenced by regional architectural traditions, should not only be considered reliquaries but also as living manifestations of the Buddha. This perspective challenges conventional views of Buddhist monuments by highlighting the deep integration of indigenous practices into the construction of these sacred sites (Bareau 1955; Schopen 1988, 1989; Stone 1994).

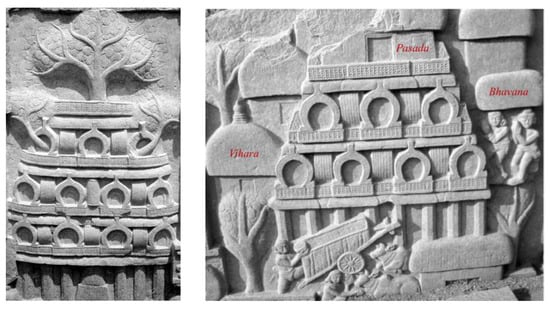

In Nāgārjunakoṇḍa, the term “cetiya”, along with mahācetiya, was employed to denote the adaptation of local architectural styles in the construction of Buddhist shrines, emphasizing the incorporation of vernacular building traditions into the sacred landscape. Conversely, the Buddhist stūpa at Kanaganahalli in South India, known for its extensive bas-reliefs with numerous labels, presents a different linguistic context. Inscriptions at Kanaganahalli recorded only four terms for small shelters or holy spaces: kuṭī, vihāra, bhavana (described as oviform, lacking a pinnacle), and paksa (meaning “wing”). Notably, the “cetiya” and “mahācetiya” are absent from Kanaganahalli’s inscriptions, highlighting regional variations in terminological usage (Meister 2007).

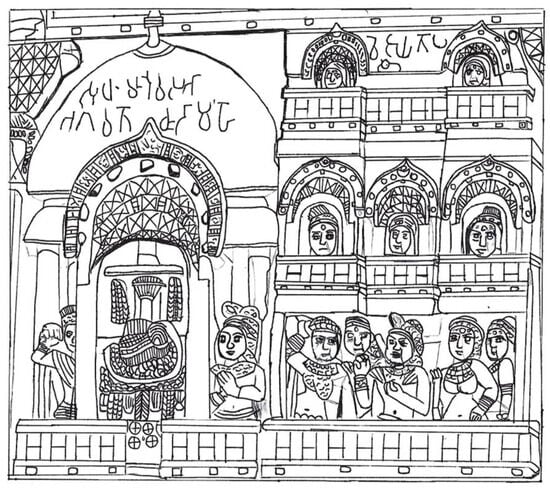

Furthermore, inscriptions on bas-reliefs depicting the palace of Indra and the hall of Gods, which are likened to stūpa-shaped shrines at Bharhut, employ the names Devasabhā (a hall of gods) and prāsāda (the upper stories of a palace) to describe multi-storied cottages and shrines, respectively [Figure 2 and Figure 3].

Figure 2.

Devasabhā, Bharhut (line drawing by the author) (Left), and three-storied prāsāda (Indra’s palace in heaven), Bharhut (line drawing by the author) (Right).

Figure 3.

Prāsāda a Tree shrine, Kanaganahalli (Meister 2007, p. 4; Kim 2011) (Left), and three-storied prāsāda (pāsāda) (Indra’s palace in heaven), Kanaganahalli (Meister 2007, p. 10; Kim 2011) (Right). The author has obtained permission from the copyright holder.

These observations clarify the deliberate avoidance of the term “stūpa” while highlighting that vernacular structures were commonly utilized when terminology for shrines, stūpas, and shelters underwent revision. This indicates that new architectural forms, such as caitya/cetiya, adopted local building styles that had been consistently used in prior centuries. The use of the term “cetiya” predates the establishment of the Nāgārjunakoṇḍa monastic complexes. The construction of cetiyas was shaped by indigenous religious practices associated with the Yakṣa, likely influenced by local northern Indian cults.

Consequently, the term “cetiya” became entrenched in the assimilation of Brahmanical shrines into Buddhist architecture, representing the standard form of a Buddhist shrine. It also included vernacular terms for shelters like kuṭī, prāsāda (notably seen in various styles derived from southern Dravidian temples), vimana, and vihāra. Over time, “cetiya” evolved to denote shrines for deities across Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism.

4. Redefining Pagodas as Ta, Dagoba, Fudo, and Zhidi

The debate over the origin of the term “pagoda” in East Asia reflects the complexities of cultural and architectural history. Sicheng Liang’s (1984) hypothesis that the term “pagoda” derived from “八角塔” (bājiǎotǎ, eight-cornered tower), based on the phonetic similarity between “bājiǎotǎ” and “pagoda” during the Tang Dynasty, represents a significant scholarly position. Liang’s theory is supported by the architectural milestone of constructing an octagonal pagoda for the esteemed monk Qingzang in Hunan province in 745, an event that arguably influenced the adoption of the term in European languages to describe similar monuments. This interpretation suggests a linguistic evolution coinciding with the architectural innovations of the time, with “bājiǎotǎ” in southern China being pronounced as “pachiaot’a” or “pagota” (Liang 1984). However, Liang’s analysis may have overlooked the historical presence of eight-cornered towers before the Tang Dynasty. Evidence of such structures has been discovered in ritual shrines and pagodas within the Hwando-seong (mountain fortress) of Jian and Najeong of Gyeongju from the Goguryeo and Silla periods as well as in the Mingtang (luminous hall) of Empress Wu. These findings, which predate Tang architectural practices, challenge the notion that the architectural form and the term “pagoda” emerged exclusively during the Tang Dynasty (Cha and Kim 2023).

Further exploration into the etymology of “pagoda” reveals that it may also derive from the Dravidian term “pagoda/pagavadi”, linked to the Sanskrit bhagavadi (referring to the Kali goddess), or the Persian butkada (temple), indicating a diverse set of linguistic and cultural influences (Thompson 2008, p. 134). These findings suggest that the term “pagoda” encapsulates a blend of architectural, religious, and linguistic elements across Asia, thus challenging the notion of a singular source of origin.

As Buddhism expanded beyond the Indian subcontinent, the names and designs of Buddhist monuments evolved to reflect the architectural and religious contexts of different regions and eras. This led to the emergence of new forms of buildings inspired by traditional stūpa and caitya architecture that displayed distinct variations in shape, function, and symbolism. These adaptations allowed Buddhist architecture to merge seamlessly with existing religious and official structures.

Taw (1912) suggested that the term “pagoda” originated from structures akin to tumuli, underscoring the widespread ancient practice of venerating ancestors’ tombs. This concept resonates with the construction of Egyptian pyramids, the Imperial Tombs of the Ming Dynasty, and other periods in China; the Roman Catholic observance of All Souls’ Day in November; and the Tomb Sweeping Festival held in April in China. Within the Buddhist context, the Sulamani pagoda, located on Mount Meru, is considered an archetypal pagoda. It is revered for enshrining the hair that Siddhartha Gautama shed during his profound renunciations of worldly life, symbolizing the pagoda’s deep-rooted connection to both spiritual and ancestral veneration (Taw 1912).

The transformation of the term “dagoba” into “pagoda” illustrates a fascinating instance of linguistic metathesis in the context of Buddhist architecture. The term “shwedagon” is believed to have evolved from “shwe-dagob”, highlighting the linguistic shifts accompanying the geographical spread of Buddhist architectural forms. A notable distinction exists between Indian topes and Sinhalese dagobas in terms of structure and design. Indian topes are characterized by solid or nearly solid domical masses of masonry on a low base, reminiscent of the Etruscan tumulus with its conical shape, whereas Sinhalese dagobas feature relics placed within a “dhātugarbha” or relic chamber, typically situated near the structure’s pinnacle (Schopen 1988).

The Chinese terms for stūpa, including ludupo 率堵婆, sutoupo 蘇偷婆, dousoubo 斗薮波, and sutupo 窣堵婆, where “窣” is pronounced as “su”, reflect transliterations from the Sanskrit stūpa or Sinhalese dagoba (Xiao 1989, p. 145). However, the pronunciation of these terms during the Tang period likely differed from their modern forms, which had been shaped since the Qing Dynasty. This discrepancy raises intriguing questions regarding the historical evolution of pronunciation systems in East Asia, suggesting a complex interplay between the Chinese and Korean linguistic traditions. The similarity between the transliteration of “pa” in Sanskrit and its pronunciation in Korean, as opposed to Chinese, hints at the preservation of Tang-era pronunciation traditions in contemporary Korean. This phenomenon underscores the potential influence of historical pronunciation systems across different periods and regions, including the Yuan, Ming, and Qing Dynasties.

Furthermore, the term “stūpa” in Pali, known as thupa, finds its counterparts in Chinese transliterations such as doupo 兜婆, toupo 偷婆, and tapo 塔婆, alluding to the rich tapestry of linguistic adaptation and transliteration processes that have shaped the terminology of Buddhist architecture across cultures and epochs.

Zhiti 支提 or zhidi 脂帝 is a transliteration of caitya in Sanskrit and cetiya in Pali. Caitya and cetiya are synonymous and are called zhidi 制底 or zhiduo 制多. In particular, the Xu yiqiejing yinyi 續一切經音譯 (Extended Pronunciation and Meaning in the Complete Buddhist Canon) elaborates the definition further—“zhidi was formed by ‘piling up’ (earth or brick), and the tamiao 塔廟, tai 臺, and ge 閣 were installed in venues where Buddha entered into Nirvana and he taught people. Tumulus of the dead and temple of the soul were called venues where the endless virtue of Buddha was piled and collected” (Anonymous. n.d.c).

The term ‘ta’ first appeared in a fourth-century dictionary, marking its earliest usage. Previously, it was synonymous with futu 浮圖 or 浮屠, fodou 浮都, and fotu 佛圖, terms that originally denoted Buddha in East Han documents and also served as the transliteration for Buddha in Sanskrit.

The text “Yiqiejing yinyi 一切經音譯” (Pronunciation and Meaning in the Complete Buddhist Canon), compiled by Hui Lin 慧琳 (737–820 CE) during the Tang period, notes that previously no term corresponded to "ta." The work lists various transliterations such as ‘soudoubo’ 薮斗波, tabo 塔波, doupo 兜婆, toupo 偷婆, sutoupo 苏偷婆, zhidifudou 脂帝浮都, zhitifutu 支提浮圖 for stūpa, cetiya, Buddha, and caitya in Sanskrit or Pali. Sudubo 窣堵波 could be translated into miao 廟 (shrine) or fangfen 方墳 (tumulus) (Anonymous. n.d.b). In conclusion, the text underlines that the stūpa in Indian Buddhism was acknowledged as both a shrine and a grave.

Chapter 37 of Fayuan zhulin 法苑珠林 (Jewel Forests of Dharma Garden) includes the definition of ta. It says, “the ta was tapo 塔婆 (pagoda) and fangfen 方墳 (tumulus)” simultaneously (Daoshi 668). Conversely, the zhidi 支提 represents where the wicked are terminated, and the virtuous are born. The book states, “the dousoubo 斗薮波 was called huzan 护赞, meaning protection and patronization. People praise and endorse constructions highly” (Daoshi 668). The term dousoubo (or huzan) was the outcome of an endeavor to understand the true meaning of the stūpa and accommodate the building type in simonized terms. The book states, “the sudubo 窣堵波 is referred to as the miao 庙, (a type of ancestral shrines or temples), and has the shape of shrines; thus, it looks like ling miao 靈廟 (temple of spirit)” (Daoshi 668). In addition, juan 114 of the Weishu 魏書, the Shilaozhi 釋老志 (Treatise on Buddhism and Daoism) states, “it was said that the ta was zongmiao 宗廟 (ancestral shrine). Therefore, it was named tamiao 塔廟” (Chen, n.d., Juan 20; Juan 114).

These interpretative changes from the sudubo have been significant in showing that the Chinese recognized the stūpa as a temple shrine over time, similar to caitya/cetiya shrines. The character “塔” (tower or pagoda) first appeared from the Ziuan 字苑 in the third century; Ge Hong 葛洪 writes, “the ta is defined as futang 佛堂 (Buddha hall), 塔, 佛堂也” (Ge n.d.; Anonymous. n.d.b). In the Qing period, Zhuang Xin noted, “there were no characters for ‘ta’ in the ancient epoch”. The beginning literally lent sounds of beating drums (Xiao 1989, p. 145); subsequently, it was called tawu 塔宇 (Anonymous. n.d.c). Borrowed from the Sanskrit “buddhastupa”, the phonetic evolution of the term is as follows: Buddhastupa, stupa, tupa, and t’ap. (Zhiwei 2004).

This attitude indicates that stūpa, mahacetiya, and cetiya have appropriately inherited the role of shrines as both tombs and image halls and have made efforts to accurately embody all facilities for the same ceremonial functions through local architectural types.

5. Re-Making Sinified Building Types in the Conceptual Combination of Stūpas and Cetiyas

Buddhist doctrines were systematically translated into classical Chinese from the Eastern Han to the Tang periods. Many terms were transliterated into Chinese pronunciations. In terms of stūpa in China, the meaning of ta expanded from referring to the storage of Buddha relics, images, and scriptures to buildings on the graves of monks. Generally, in East Asia, stūpas have a centralized plan and towering body. When a central pillar is installed at the apex of a tower, it could be called the ta construction. In the development of the meaning, the names sarita 舍利塔, fota 佛塔, jingta 經塔, and muta 墓塔 appeared in later scriptures (Xiao 1989, p. 146). Significant attention is drawn to the Xu yiqiejing yinyi, notable for its lack of differentiation between sutupo/ludupo and zhidi, implying that these may represent functionally similar structures in the East Asian Buddhist tradition (Anonymous. n.d.c). Conversely, the “Mohesengzhilu” from the Mahāsaṅghika School offers a different view, stating that unlike sutupo 窣堵婆, which houses the Buddha Śarīra (relics), zhidi does not contain such relics and instead functions as a site where Buddha engaged in teaching and ascetic practices (Daoshi 668). While early Buddhist literature differentiated between zhidi and stūpa, later Mahāyāna texts tended to conflate these terms, suggesting that all zhidi house the Buddha Śarīra, as illustrated in the Suvarṇaprabhāsa Sūtra (Golden Light Scripture) (Anonymous and Yijing, 703).

Furthermore, the caitya/cetiya shrine hall with a stūpa or an image is explored for their association with tamiao, a pagoda with a shrine hall dedicated to the Buddha, frequently mentioned in the Avataṁsaka Sūtra (Flower Ornament Scripture) (Anonymous and Śikṣānanda 690). The definition of caitya encompasses buildings constructed to memorialize, worship, and extol the sites associated with significant events in Buddha’s life. Also, “caitya hall” refers to a distinct architectural style found in cave monasteries at rock-cut sites, characterized by vaulted ceilings and pillars with elongated and rectangular floorplans. This style accommodated the demands of both cooperative and individual rituals for the augmentation of ritual performance (Fogelin 2004; Kim and Han 2011; I-Tsing 2005; Miller 2015). These halls typically include an ambulatory that surrounds a central space with octagonal or circular pillars delineating these two areas. Caitya halls feature multiple levels, embellished with sculptures and ornate architectural carvings.

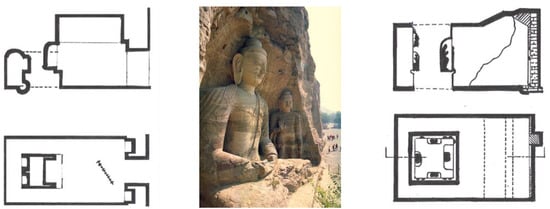

As it was implemented along the Silk Road to East Asia, this elongated space demonstrates stylistic changes and decorations based on local techniques and preferences through a hybridization process with indigenous architecture. Evident from the 5th century onward, this trend displayed various hybrid processes in places such as the Kizil, Kumtura, Yungang, and Dunhuang Buddhist Caves.

Long and narrow architectural plans gained popularity in the Xinjiang region. Specifically, Cave 38 at Kizil was designed without an antechamber or vestibule and is characterized by a barrel-vaulted ceiling with the entrance located on the narrower end. Over time, at Kucha and Kumtura, the main room’s back wall became flanked by arched passageways leading to a rear chamber, which is as narrow as a corridor. These passageways form a square unit that functions as a central pillar, although it does not house a pillared stupa. Instead, it features independent Buddha images set against simple arched niches or walls directly in view (Ho 1992, p. 61). This architectural choice likely represents the best solution within the technical constraints of wooden structures at that time. This method of construction may be seen as a precursor to techniques used in later cave monasteries such as Dunhuang and Yungang, marking a progression in excavation methods (Ning 2004; Kim and Han 2011). The initial five large grottoes at Yungang were typically designed with oval-shaped plans and domed, hut-like ceilings, resembling large modern yurts (Chang 2021). The common central pillar type seen in regions like Kizil, Dunhuang, Bezeklik, and Yungang, is usually situated at the intersection of two passageways along the lateral walls and extends to the rear wall, forming an ambulatory pathway [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Kizil Cave 38 from the late 4th Century (line drawing by the author) (Left), the Buddha statue of Yunkang Cave 20 (the middle 5th Century) (photo by the author) (Middle), the Line Drawing of the Sectional elevation and Ground plan at Dunhuang Cave 257 (the 6th Century) (line drawing by the author) (Right).

Monasteries featuring a central pillar facilitate the symbolic connection between the divine and human realms by enabling circumambulation around the shrine. This central pillar system may have been adopted by monks in Kucha to incorporate Indian ritual practices. By the late 5th century, this style had evolved and was prominently represented in Yungang. In Central Asia, these cave monasteries, which trace their origins to Indian influences, consistently positioned an independent Buddha image at the cave’s center. They preserved many elements of Indian sanctuaries, transitioning from a squared central pillar supporting independent Buddha images, consequently transmitting these architectural and religious features from India through Central Asia to East Asia.

Although much confusion surrounded the meaning of stūpa before the Sui to Tang Dynasty transition (613–628), it had been indicated as a tumulus, spirit shrine, ancestral temple, and even as a Buddha hall. Ta used the transliteration of caitya/cetiya. Even if the implications of the ta were subsequently extended in comparison to the initial grave of Buddha, in the end, ta was a Buddhist monument for memorialization and worship.

Therefore, ta adopted the functions and meanings of stūpa and those of caitya/cetiya construction simultaneously and was, thus, referred to as an “ancestral shrine 廟”, and “Buddha hall 佛堂”, respectively, keeping the original meaning and function of stūpa in Indian Buddhism.

Juan 49 of the Sanguozhi 三國志 recorded features of early Buddhist pagodas, conveying the early representation of a pagoda in East Asian culture. The historical source states, “Zhai Rong 窄融, a devotee who resided in the province of Jiangsi, erected the Futu-ci 浮圖祠, and he made a human figure of bronze gilded and clad in brocade. Nine-storied bronze disks were hanging down above the two-storied pavilion. The covered flying passageway of the two-storied pavilion could hold about 3000 devotees” (Chen n.d.; Wei n.d.a).

Another record of Fudu-si architecture, included in the Later Hanshu, reads, “Zhai Rong erected the Fudu-si 浮屠寺. Golden plates were superimposed above a two-storied pavilion 重楼 (a multi-storied pavilion that consists of one dwelling superimposed on another dwelling), which was surrounded by the tang (hall) and ge (pavilion surmounted by vertical and straight columns), which could accommodate about 3000 people. There is a gilded image clad in brocade” (Fan 398–446 CE, 63).

The historical documentation surrounding the Futu-si offers significant insights into the architectural and linguistic integration that accompanied the spread of Buddhism to East Asia. The term “futu”, a transliteration of “Buddha” in Sanskrit, underscores the syncretic nature of early Buddhist architecture, combining existing local structures with new religious forms introduced by Buddhism. The designation “futu” was specifically applied to stūpas, indicating that during this period, the specific term “fota” 佛塔 for pagoda had not yet been established. The suffix “ci” or “si” denotes an ancestral shrine or a temple, although “ci” was historically associated with government office quarters during the Han dynasty, where it referred to a place at which nine ministers convened to discuss national affairs (Anonymous 2004).

Thus, the term “Futu-si” or “Futu-ci” represents a pagoda-temple or pagoda-ancestral shrine, highlighting the dual function of these structures as both religious and memorial spaces. Historical records, such as the Sanguozhi from the second century CE and the Hou Hanshu by Fan Ye 範曄 in the fifth century CE, offer diverse perspectives on the classification of these structures as either shrines or temples. If we prioritize Sanguozhi as an earlier source, this suggests that early Buddhist pagodas were conceptualized primarily as shrines dedicated to Buddha. The use of “si” to denote a Buddhist temple became more common after the Late Han period, reflecting a gradual linguistic and conceptual shift wherein the pagoda was increasingly seen as part of the Buddhist monastic complex [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

The pagoda-temple in monasteries, engraved from a portrait brick unearthed from Shifang, Sichuan, the tomb of the late Eastern Han Dynasty, photo from Yun’ao He (1993, plate 3). The author has obtained permission from the copyright holder.

This evolution in terminology and architectural function mirrored changes in Indian cultural contexts, where the term vihāra expanded in meaning from a simple cell to a monastery over time. Similarly, the transformation from “ci” to “si” in the context of pagoda-temple structures illustrates a broader adaptation and integration of Buddhist concepts into local architectural and ritual practices. Over time, “si” became the standard term for a Buddhist temple, indicative of the dynamic interplay between Buddhism and local cultural traditions in shaping the religious landscape.

The combination of a pagoda with a shrine or temple had already appeared during the Han period. In the Shiji, the emperor (Han Wudi) ordered the construction of the Feillianguan Watchtower 飛廉觀 upon receiving advice from Gong, and then Ganquan 甘泉 (a spring of sweet water) was installed, adding the Yanshouguan Watchtower 延壽觀. The official Qingchi 卿持 was tasked with setting up this arrangement, initiating a vigil for the arrival of immortals.

Following this, the Tongtian Tai, an open terraced platform for facilitating communication with heaven, was constructed with shrines positioned below this platform to invoke immortals. Additionally, a front hall was established in front of the Ganquan, culminating in the expansion of the gongshi 宮室, the palace complex (Qian n.d.). Interestingly, he ordered the construction of the Tongtiantai Platform and then directed which shrines to be installed below the platform to incur variants of Gods and set up the front hall in the Gan Quan. In his annotation of the Tongtiantai Platform, Yanshigu 顏師古 (581–645) described the platform as a towering structure: the platform was high, and goes through heaven, thirty zhang in height” (Bangu n.d.). The lower sections of these structures featured the Ganquan Spring, the main hall (front hall) for ancestral shrines 祠廟, and furnished and decorated halls 殿堂 to appease the immortals.

Lanxiang Huang (2007) added a supplementary account: “The installation of the ancestral shrines and the halls to incur immortals below the terraced platform provides an interesting contrast with the Buddhist temple afterward”. As stated above, the Futu-si had two functions on the upper and lower floors of a building—a pagoda and a shrine/temple, respectively. Later, the combination of a pagoda with a shrine was divided into a pagoda and a hall, reminiscent of the Mahabodhi temple at Bodh Gaya temple, where Faxian and Xuanzang visited in the 5th and 7th centuries CE, respectively (Adachi 1987, pp. 42–45). For instance, when Ling Taihou 靈太后, an empress and mother of Xiaomingdi (孝明帝, r. 515~528), the eighth ruler of Northern Wei, constructed the Buddhist temple, the Buddha Hall (main hall) was placed in the north side (rear side) of the Buddha pagoda” (Huang 2007); it is conceived that the Hall was decorated and furnished as a mechanism for attracting immortals. In contrast, the pagoda provided a view of the main hall and stood at the peak of Mount Sumeru of Buddha and his dwellings in Buddha’s biography (Kim 2024). The hall and pagoda became one of the sacred locales presented by King Asoka and resembled dwellings (caitya/cetiya) where Buddha had once stayed and tumulus (stūpas) in which his saris were enshrined after his death. Subsequently, they became sacred locales where his saris were laid out and presented. These places have become key targets for pilgrims and rituals.

Different theories exist regarding the development of the Buddha pagoda in East Asian culture; some scholars considered the pagoda a combination of the Indian stūpa with the multi-storied watch tower or pavilions of East Asian buildings in the pre-Buddhist tradition (Ledderos 1980, pp. 240–43; Liang 1984, p. 124; Liu 1984, p. 56). Ko Adachi (1987) suggested that the pagoda resembled the multi-storied pavilions of Indian Buddhist halls or that it derived from the ancient Chinese “divine tower”. He understood that the Mahabodhi Temple at Bodh Gaya was a kind of shrine (Buddha hall) widely prevalent in India at that time; specifically, the temple was built to create an image that represented Buddha’s enlightenment (Adachi 1987, pp. 42–45).

The pagoda was regarded as a synthesis of the Indian stūpa and traditional Chinese multi-storied watchtowers or pavilions. Historical accounts of Futu-si (or Futu-ci; pagoda-temples) often mention “nine-storied disks” stacked atop “double-eaved” or “double-storied” pavilions, specifically referencing a “double-eaved pavilion (zhonglou)” and the capacity to accommodate “5000 devotees”. It is suggested that these constructions melded local architectural styles featuring timber with elements from the Indian stūpa, such as the chattrayaṣṭi (parasol or canopy), represented by “nine-stories of disks” symbolizing nine-tiered jewel disks 九輪 (jiulun). These accounts illustrate how early Buddhist architecture integrated local structures like lou, ge, and tang with the Indian stūpa. Additionally, Sicheng Liang (1984) noted that the pagoda has been a significant architectural feature shaping the Chinese landscape from its inception to the present, typically retaining the form of “a multi-storied tower topped by a pile of metal discs”. This structure reflects the fusion of the “multi-storied tower”—reminiscent of the lou or ge used in local construction—with the “pile of metal discs” characteristic of the Indian stūpa. Liang further categorized the evolution of Chinese pagodas into four main types based on this architectural synthesis: one-storied, multi-storied, multi-eaves, and stūpas (Liang 1984).

Another theory suggests that the pagoda was derived from the multi-storied pavilions of Indian Buddhist halls. Indian construction was introduced through the building of preliminary Buddhist temples in China, established in 68 CE under the patronage of Emperor Ming in the Eastern Han capital Luoyang. In the Weishi, Shilaozhi mentioned the White Horse Monastery and described futu (used here to indicate the stūpa). The historical book reads, “The plan of the temple–stūpa is in every case a many-storied structure based on Indian models. The stories may number one, three, five, seven, and nine. Men of the world call these pagodas, called the ‘futu’ 浮圖 (a transliteration of Buddha)” (Wei n.d.b). Shilaozhi states, “The correct name of futu is called fotuo, and the sound of futu and that of fotuo have a likeness to each other. Both originated in the western region (India) 浮屠. 正號曰佛陀. 佛陀與浮圖. 聲相近.皆西方言”. This implies that the term futu, which indicates a Buddha pagoda, was derived from fotuo, the transliteration of the Buddha (Wei n.d.b).

The final theory contends that the primitive model of the pagoda’s sinification had already existed in earthenware building miniatures, such as architectural lacquer miniatures, since the Han period. Most miniatures discovered thus far have been uncovered in areas adjacent to Luoyang, the capital of East Han (Henan Museum 2002). Many architectural constructions, such as the earliest reliefs of the Chinese pagoda, were also imprinted on cave temples. They portray multi-storied constructions with wooden posts, beams, tie-beams, and dougong, which provide exemplary evidence of the Indian stūpa sinicized by the Northern Wei (Liang 1984, p. 31; Liu 1984, pp. 56, 78–80).

During the Qin and Han dynasties, emperors sought to incorporate Daoist concepts of immortality into their architectural endeavors. This is evidenced by the construction of towering structures like the Bailiangtai, Tongtiantai, Shenmingtai Platforms, and Jingganlou Pavilion, as documented in Shiji (Qian n.d.), which classified various building types used in sacrificial rituals as lou, ge, ting, and tai. These elevated constructions featured top stories designed as contact points for immortals fond of dew. Emperors placed dew basins, known as lupan 露盤, adorned with figurines of immortals collecting dew to attract these celestial beings. The lupan was held by figures of immortals, who collected the dew in their palms. Both Shiji and Hanshu mention these dew-collecting tubs (lupan) on the Bailiangtai and Shenmingtai Platforms. Under Emperor Wudi’s decree, two highrise terraces were erected within Jianzhanggong Palace, with the Shenmingtai and Jingganlou advised by an ascetic from Guandong, while the Bailiangtai was recommended by Shao Wen and Gongsun Qing.

In Buddhist architecture, the lupan was adapted atop stūpas to support the fubo 覆鉢, an inverted earthenware basin crowned with a chattrayaṣṭi (parasol) and encircled by a harmikā (a squared platform with railings atop the stūpa). This integration of Daoist terminology and design elements illustrates the merging of new Buddhist architectural forms with pre-existing ones, suggesting a syncretic approach to building (Huang 2007, pp. 20–22; Tanaka 1988). The architectural design of the Futu-si pagoda-temple/shrine also borrowed elements from Taoist structures like the Re-ci 仁祠 and Zhuolong-gong 濯龍宮, built by Chu Wangying 楚王英 and Han Huandi 漢桓帝, respectively. These buildings combined high-rise buildings intended for meetings with immortals and a “main hall” for offerings to these beings.

As Buddhism expanded throughout East Asia, rather than merely transplanting the Indian stūpa, local building styles, and architectural methods were adapted to suit regional preferences and religious functions (Ledderos 1980, p. 242; Xu 2020). Ledderos noted that while pre-Buddhist concepts were not entirely discarded, mature Buddhist architecture attempted to balance traditional local structures with the original doctrinal requirements of Buddhist constructions. This architectural strategy was not just about creating religious spaces but was also part of a broader imperial strategy to communicate with the heavenly realm, aiming to secure an immortal afterlife; specifically, rulers hoped to be borne into with Buddhist well-being and pure lands.

6. Conclusions

This study delves into the transformation and regional distinctions in the terminology and architectural principles of Buddhist edifices, focusing on the shift from the terms “stūpa” to “cetiya” and “mahācetiya and then “pagoda”. It demonstrates a strategic transition in the terms used within Buddhist scriptures and engravings, mirroring an extensive regional impact on the architectural lexicon of sacred Buddhist locations. This transition highlights the incorporation of indigenous architectural customs into the creation of Buddhist shrines, where cetiya implies structures that encapsulate the Buddha’s living essence, signaling that they surpassed their function as mere reliquaries. It further elucidates the integration of Brahmanical and local shrines into Buddhist architecture, establishing the cetiya as a crucial architectural entity within Buddhism. Consequently, the “cetiya” and “mahācetiya” symbolize the syncretic evolution of religious architecture into shrine-temples across the Indian subcontinent, embracing an array of cultural, religious, and architectural influences. These notions of shrine-temples have significantly shaped the foundational design principles of the main buildings in East Asian Buddhist temples.

Additionally, this study reflects the amalgamation of Buddhist architectural concepts in China, illustrating the gradual merging of stūpas and cetiyas into singularly significant monuments for both commemoration and veneration. This underscores the pivotal role of the Han Dynasty in amalgamating pagodas with regional shrines and temples and the vital role of syncretism in the proliferation of Buddhist monuments throughout East Asian history. The discourse navigates through the sinification of the Buddhist pagoda, showcasing how the term “futu” signifies the blending of native architectural styles with Buddhist symbolism, positioning pagodas as both spiritual symbols and monumental landscape features.

Moreover, the discussion ventures into the Daoist influence on Buddhist architectural endeavors, depicting how antecedent constructions were adapted and integrated into Buddhist architectural designs, thereby promoting cultural and religious confluence. This is particularly evident in the fusion of the elevated structures for divine communication with the main halls designated for offerings.

The architectural ritual spaces of Indian Buddhism adopted indigenous ritual buildings that existed before the establishment of Buddhism to reproduce places related to the life of the Buddha. This approach of utilizing local ritual buildings was similarly adopted in the development of Buddhist architecture across China and East Asia, with a commitment to preserving the ritual traditions rooted in Indian Buddhism. This adaptation is also mirrored in Buddhist texts, where the terms stūpa/mahācetiya and caitya/cetiya were modified to describe structures ranging from simple pagodas to more complex forms such as pagodas with halls or images. For instance, the term “zhidi”, a transliteration of cetiya, appears in the Suvarṇaprabhāsa Sūtra (Golden Light Sutra) to signify the concept of a Buddha-pagoda with halls. Similarly, in the Avataṁsaka Sūtra (Flower Garland Sutra), “tamiao” denotes the idea of stupa-shrines or image-shrines, underscoring their significance in Buddhist architectural and ritual contexts.

Essentially, this study presents the evolution of Buddhist pagodas in East Asia as a complex interplay between local traditions and Buddhist ideologies, leading to unique architectural manifestations that serve dual sacred and secular purposes. This dynamic adaptation of Buddhism within the East Asian architectural and cultural framework signifies a cautious balance between the conservation of local traditions and acceptance of foundational Buddhist doctrines.

Funding

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education [(No.2021R1I1A3059811)]. Also, this work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2021S1A5A8073054).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

Primary Sources

Anonymous. Śikṣānanda. 690. Avataṁsaka Sūtra (Flower Ornament Scripture), Taisho 279Anonymous. Yijing. 703. Suvarṇaprabhāsa Sūtra (Golden Light), Taisho 16, no. 665Anonymous. 2004. Handian. Available online: http://www.zdic.net (accessed on 10 June 2023).Anonymous. n.d.a. Mohesengzhilu. Taisho 53 no. 1425Anonymous. n.d.b. Xu-Yiqiejing yinyi Taisho. vol. 54. no 2129Anonymous. n.d.c. Yiqiejing yinyi Taisho 54 no 2128Anonymous. n.d.d. Yourao fota gongde jing. Taisho 16 no 7.Bangu. Wudiji di liu 6, Hanshu. 6 vols.Chen Shou, n.d. Sanguozhi.Daoshi. 668. Fayuan Zhulin. Taisho 53.Fan, Ye (398–446 CE). Hou hanshu, Tao qian chuan, Liechuan 63.Handian. 2004. Available online: http://www.zdic.net (accessed on 10 June 2023).Qian, Sima. n.d. Shiji, ‘Xiao wu benji 12’ vol. 12.Wei, Shou (506–572 CE). n.d.a. Wushu, Liukuang chuan, vol. 4, Sanguozhi, vol. 49.Wei, Shou. n.d.b. Weishi. Shilaozhi 10, Juan 20.Secondary Sources

- Adachi, Ko 足立康. 1987. Toba Kenchiku No Kenkyu 塔婆建築の硏究 [A Study of Stupa Architecture]. Tokyo: Chuo Koron Bijutsu Shuppan. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawala, Vasudeva S. 2003. Indian Art: (a History of Indian Art From the Earliest Times up to the Third Century A.D.). Kathmandu: Prithivi Prakashan. [Google Scholar]

- Bareau, André. 1955. Les Sectes Bouddhiques Du Petit VéHicule. Saigon: Ecole française d’Extrême-Orient. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, James. 1883. Report on the Buddhist Cave Temples and their Inscriptions. London: Archaeological Survey of Western India, vol. IV. [Google Scholar]

- Cha, Ju-Hwan, and Young-Jae Kim. 2023. Recognizing the correlation of architectural drawing methods between ancient mathematical books and octagonal timber-framed monuments in East Asia. International Journal of Architectural Heritage 17: 988–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Qing 常青. 2021. Zhongguo Shiku Jianshi 中國石窟簡史 [A Brief History of Chinese Grottoes]. Hangzhou: Zhejiang guji chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Conze, Edward. 1975. The Large Sutra on Perfect Wisdom, with the Divisions of the Abhisamayalaṅkara. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coomaraswamy, Ananda K. 1992. Early Indian architecture. In Essays in Early Indian Architecture. Edited by Michael W. Meister. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coomaraswamy, Ananda K. 1993. Yaksas: Essays in the Water Cosmology. New Delhi: Gandhi National Center for the Arts. [Google Scholar]

- Coomaraswamy, Ananda K. 2003. History of Indian and Indonesian Art. Whitefish: Kessinger Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Coomaraswamy, Ananda Kentish, and Michael W. Meister. 1988. Early Indian architecture: IV. Huts and related temple types. RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 15: 5–26. [Google Scholar]

- Cousens, Henry. 1982. The Architectural Antiquities of Western India. New Delhi: Cosmo. [Google Scholar]

- Das, Sarat Chandra, Graham Sandberg, and Augustus William Heyde. 1902. A Tibetan English Dictionary. Calcutta: Bengal Secretariat Books Depot. [Google Scholar]

- Devi, Ragini. 2002. Dance Dialects of India. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Dutt, Sukumar. 1962. Buddhist Monks and Monasteries of India. Their history and their contribution to Indian culture. London: George Allen. [Google Scholar]

- Dutt, Sukumar. 1984. Early Buddhist Monachism. Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal. [Google Scholar]

- Fogelin, Lars. 2004. Sacred architecture, sacred landscape: Early Buddhism in north coastal Andhra Pradesh. In Archaeology as History in Early South Asia. Edited by Himan-shu Prabha Ray and Carla M. Sinopoli. New Delhi: Aryan Books, pp. 376–91. [Google Scholar]

- Foucher, Alfred. 1903. ‘Les bas-reliefs du stūpa de Sikri’, Extrait du Jounal asiatique. Paris: Imprimerie nationale. [Google Scholar]

- Foucher, Alfred. 1905. L’art gréco-bouddhique du Gandhâra: étude sur les origines de l’influence classique dans l’art bouddhique de l’Inde et de l’Extrême-Orient. Paris: E. Leroux. [Google Scholar]

- Foucher, Alfred. 1960. Etude sur le Stūpa Dans l’Inde Ancienne. Bulletin de l’école française de l’Extrême-Orient 50: 37–116. [Google Scholar]

- Foucher, Alfred. 2010. The Beginnings of Buddhist Art and Other Essays in Indian and Central-Asian Archaeology. Charleston: Nabu Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gimello, Robert. 2006. “Environments” Worldly and Other-Worldly: Wutaishan and the Question of What Makes a Buddhist Mountain “Sacred”. International Seminar of Buddhist Ecology. [Google Scholar]

- Gnoli, ed. 1978. The Gilgit Manuscript of the Sayanasanavastu and the Adhikaranavastu: Being of the 15th and 16th Sections the Vinaya of the Mulasarvastivadin. Roma: Istituto italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente. [Google Scholar]

- Guruge, Ananda W. P. 1991. The Society of the Ramayaṇa. Ajmer: Abhinav Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Gutschow, Niels, David N. Gellner, and Bijay Basukala. 1997. The Nepalese Caitya: 1500 Years of Buddhist Votive Architecture in the Kathmandu Valley. Stuttgart: Menges. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, Peter. 1984. The symbolism of the early stūpa. Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 7: 67–94. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, Peter. 1990. Venerated Objects and Symbols of Early Buddhism. In Symbols in Art and Religion: The Indian and the Comparative Perspective. Edited by Karel Werner. London: Curzon Press, pp. 68–102. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, Peter. 1991. An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Havell, Ernest Binfield. 1920. A Handbook of Indian Art. London: John Murray, vol. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Hazra, Kanai Lal. 2002. Buddhism and Buddhist Literature in Early Indian Epigraphy. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- He, Yun’ao 賀雲翱. 1993. Fojiao chuchuan nanfang zhilu 佛教初傳南方之路: 文物圖錄 [The Path of Early Buddhist Transmission to the South: Illustrated Catalogue of Cultural Relics]. Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Henan Museum. 2002. Henan Chutu Handai Jianzu Mingqi 河南出土漢代建築明器 [Han Dynasty architectural mingqi excavated in Henan]. Zhengzhou: Henan Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Hirakawa, Akira. 1963. The Rise of Mahayana Buddhism and its Relationship to the Worship of Stūpas. Memoirs of the Research Department of the Toyo Bunko 22: 57–106. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, Puay-Peng. 1992. Cave-Temple Pillar Symbolism, Sacred Architecture. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Lanxiang 黃蘭翔. 2007. Chuqi zhongguo fojiao siyuan peizhi de qiyuan yu fazhan 初期中國佛教寺院配置的起源與發展 [The Origins and Development of the Layout of Early Chinese Buddhist Temples]. In Fojiaojianzhu de chuantong yu chuangxin: 2006 nian fagushsn fojisojisnzhu yantao huilunwenji, shi sheng yan deng zhu. 佛教建築的傳統與創新:2006年法鼓山佛教建築研討會論文集 [Tradition and Innovation in Buddhist Architecture: Proceedings of the 2006 Dharma Drum Mountain Buddhist Architecture Symposium]. Taibei: fagushan wenhuashi yegufen youxiangongsi, pp. 13–73. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington, Susan L. 1990. Early Buddhist art and the theory of aniconism. Art Journal 49: 401–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, John. 1980. The Axial Symbolism of the Early Stūpa: An exegesis. In The Stūpa: Its Religious, Historical and Architectural Significance. Edited by Anna Libera Dallapiccola. Wiesbaden: Steiner, pp. 12–58. [Google Scholar]

- I-Tsing. 2005. A Record of the Buddhist Religion as Practiced in India and the Malay Archipelago (A.D. 671–695). Arlington: AES. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Young Jae. 2011. Architectural Representation of the Pure Land: Constructing the Cosmopolitan Temple Complex from Nagarjunakonda to Bulguksa. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Young Jae. 2015. Reconsidering the symbolic meaning of the stūpa. Journal of the Regional Association of Architectural Institute of Korea 17: 159–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Young Jae. 2021. Reconstructing Pure Land Buddhist Architecture in Ancient East Asia. Religions 12: 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Young Jae. 2024. Constructing the Buddha’s Life in Early Buddhist Monastic Arrangements at Nagarjunakonda. Religions 15: 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Young Jae, and Dong Soo Han. 2011. Evolution, Transformation, and Representation in Buddhist Architecture: The Square Shrines of Buddhist Monasteries in Central Asia after the fourth century. Architectural Research 13: 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosambi, Damodar D. 1962. Myth and Reality; Bombay. Bombay: Popular Press Prakashan. [Google Scholar]

- Kramrisch, Stella. 1946. The Hindu Temple. Kolkata: University of Calcutta. [Google Scholar]

- Kuwayama, Shoshin. 1987. The Buddha’s bowl in Gandhara and the relevant problems. South Asian Archaeology 2: 946–77. [Google Scholar]

- Ledderos, Lothar. 1980. Chinese Prototypes of the Pagoda. In the Stūpa: Its Religious, Historical and Architectural Significance. Edited by Anna Libera Dallapiccola and Stephanie Zingel-AvLallemant. Wiesbaden: Steiner, pp. 240–243. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Sicheng. 1984. A Pictorial History of Chinese Architecture: A Study of the Development of Its Structural System and the Evolution of Its Types. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey, Roger. 1977. Symbolism of the Dome Coomaraswamy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Dunzhen 劉敦楨. 1984. Zhongguo gudai jianzhu shi, Jianzhu ke xue yan jiuyuan jianzhushi bian wei hui zu zhi bian xie 中國古代建築史, 建築科學研究院建築史編委會組織編寫 [History of Ancient Chinese Architecture, compiled by the Architectural History Editorial Committee of the Building Science Research Institute]. Beijing: Zhongguo jian zhu gong ye: Xin hua shu dian jing xiao. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonell, Arthur Anthony. 1929. A Practical Sanskrit Dictionary with Transliteration, Accentuation, and Etymological Analysis Throughout. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar, R. C., Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, and Bhāratītya Itihāsa Samiti. 1951. The History and Culture of the Indian People. Simlaj: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, John. 1918. Guide to Sanchi. Calcutta: Superiwnentendent Government Printing India. [Google Scholar]

- Meister, Michael W. 1988. Prâsâda as palace: Kûtina origins of the Nâgara temple. Artibus Asiae 49: 254–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]