The Prophet’s Day in China: A Study of the Inculturation of Islam in China, Based on Fieldwork in Xi’an, Najiaying, and Hezhou

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. An Overview of the Prophet’s Day

Lo! Allah and His angels shower blessings on the Prophet. O ye who believe! Ask blessings on him and salute him with a worthy salutation.(33:56)

That you [people] may believe in Allah and His Messenger and honor him and respect the Prophet and exalt Allah morning and afternoon.(48:9)

And indeed, you [Muhammad] are of a great moral character.(68:4)

1.2. Mawlid al-Nabi as the Third Festival of the Hui People of China

1.3. Methodology and Fieldwork

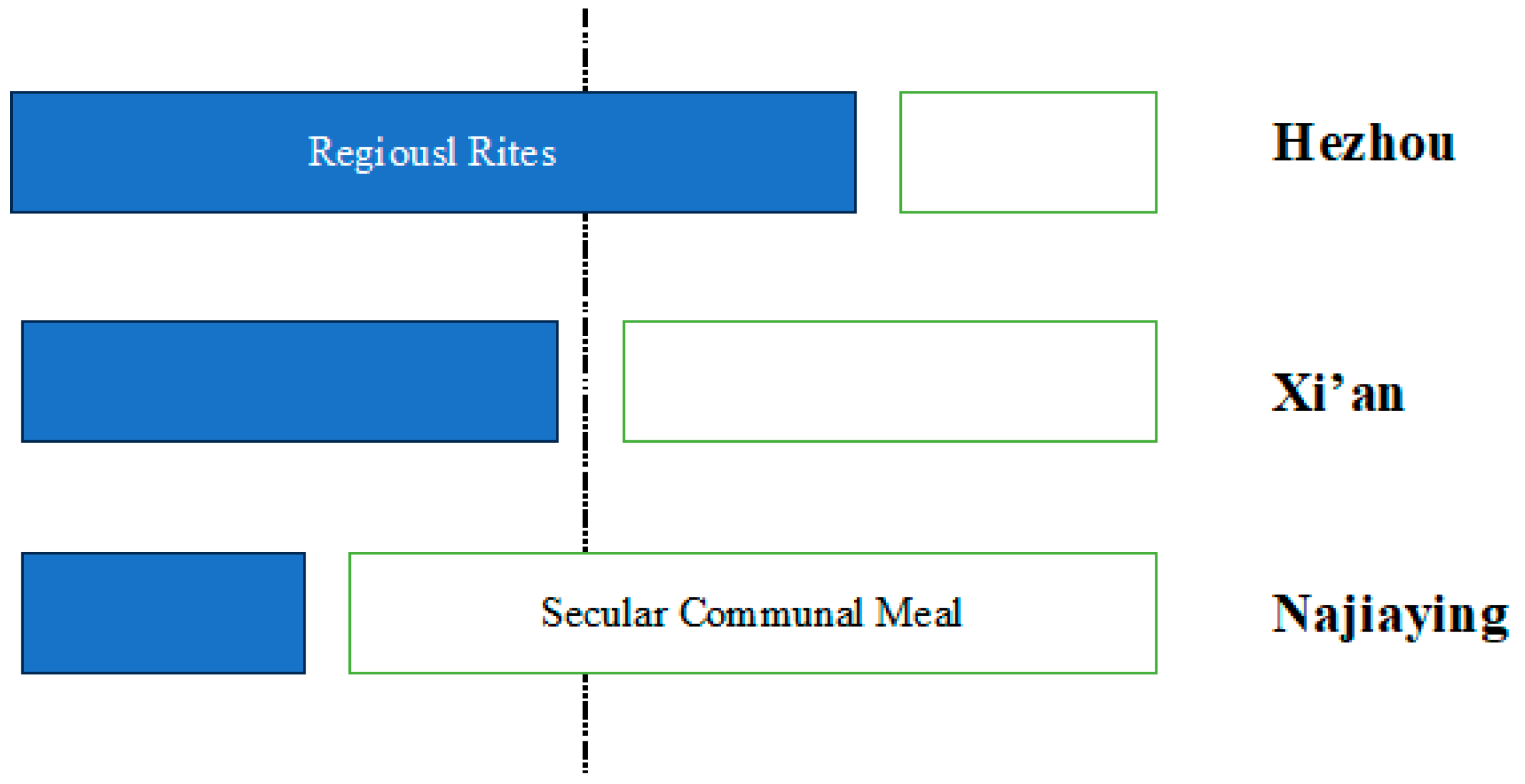

2. Xi’an: Mawlid al-Nabi as Cultural Resistance Strategy

2.1. Origin and History of the Hui People in Xi’an

2.2. The Process of the Ritual

2.2.1. Who Can Attend the Ceremony?

2.2.2. Preparations

2.2.3. The Ritual

- (1)

- Welcome Chanting from the Chanting Team

- (2)

- Reciting the Quran

- (3)

- Opening Speech

- (4)

- Supplication (Du‘a’)

- (5)

- The Second Chanting and the Appetizer

- (6)

- The Keynote Speech

- (7)

- Traditional Collective Banquet

- (8)

- Farewell Chanting

2.3. The Strategy of Date Selection

2.4. Praising the Prophet in the Melody of Shaanxi Opera

3. Najiaying: Mawlid al-Nabi as a Strategy of Cultural Insertion

3.1. Origin and History of Najiaying

3.2. The Process of the Ritual

3.2.1. Preparations

3.2.2. The Ritual

- (1)

- Day 1: al-Wa’z, Poem-chanting, and Eating

- (2)

- Day 2: the Meeting, Poem-chanting, and Eating

- (3)

- Day 3: al-Wa’z, Eating, and Farewell

3.3. The Insertion of Social Structure at the Grassroots Level

3.4. Donation and the Economic Function of the Mawlid al-Nabi

4. Hezhou: Mawlid al-Nabi as a Strategy of Cultural Innovation

4.1. Origin and History of the Hui People of Hezhou

4.2. The Ritual

4.2.1. Preparations of the Ceremony

4.2.2. Day 1: The Recitation of the Quran (Kai-Jing)

- (1)

- “Qiu-qi”: The Supplication

- (2)

- The Collective Reciting the Quran

- (3)

- Praising the Prophet

4.2.3. Day 2: The Grand Praising (Da-zan)

- (1)

- “Wan-zan”: The Complete Praising

- (2)

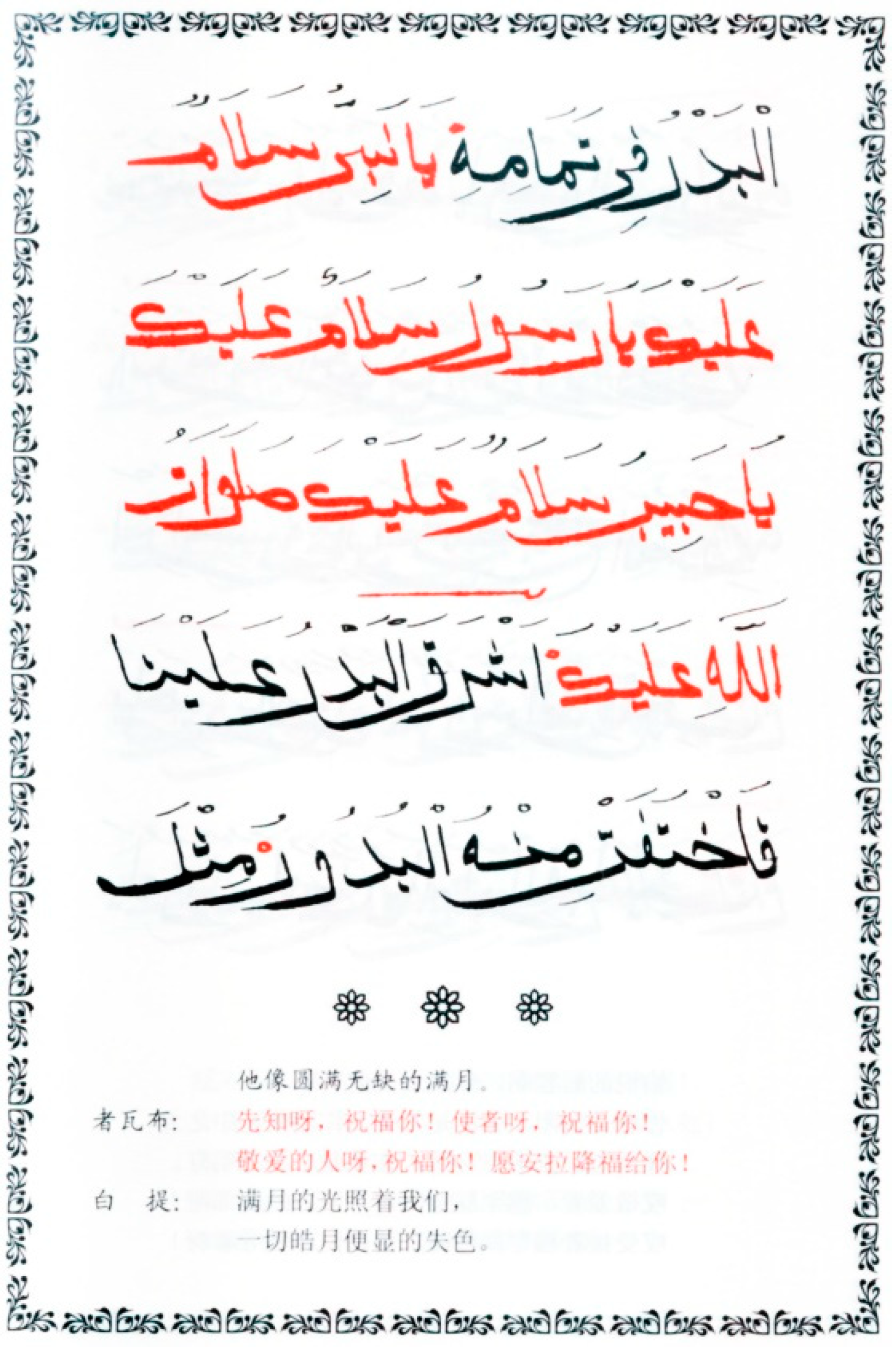

- Al-Barzanji

اخذها المخاض و اشتدت بها الامه فولدت النبي صلي الله عليه و سلم

all the people stand up, with a joss-stick in their hands, and divide into two opposite columns, leaving a passage between the entrance of the hall and the Miḥrāb (prayer niche).She went into labor and gave birth to the Prophet (peace be upon him).

- (3)

- The Bayti (couplet) and Jawāb (response)

| يا نبي سلام عليك | Oh, prophet! Peace be upon you! |

| يارسول سلام عليك | Oh, messenger! Peace be upon you! |

| يا حبيب سلام عليك | Oh, beloved! Peace be upon you! |

| صلوات الله عليك | May Allah bless you! |

| (see Figure 5). | |

- (4)

- al-Barzanji and Du’a

4.2.4. Day 3: The Dhikr of Minshār

- (1)

- “Tai-jing-lou”: A Parade of the Quran-ark

- (2)

- The Dhikr of Minshār

- “Lā ilaha illa Allāh” (no god but God). People will chant loudly and rock their body back and forth, which looks like “sawing”, raising their heads and chanting “Lā ilaha” or lowering their heads and chanting “illa Allāh”. This repeats 300 times in total, with every 100 iterations being followed by the phrase “Muhammadun rasūlullāh”.

- “Allāh Hayyun” (God is ever-living), 100 times.

- “Allāh Hayyun Dā’im Bāqī” (God is ever-living and ever-lasting), 100 times.

- “Allāh al-Hayyu” (God is the Ever-living), 100 times.

- “Allāh”, 100 times.

- (3)

- Banquet

4.3. Interconnection between Human Beings and the Sacred

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Han Kitab is a combination of the Chinese word “Han” and the Arabic word “Kitab”, meaning Muslim books written in Chinese. |

| 2 | Sachiko Murata, William Chittick, and Tu Weiming published their interpretation of Tianfang xingli in English. See in the references. |

| 3 | Ikhwan is a sect of Islam in China founded in the late 19th century by Akhond Ma Wanfu. He traveled to Mecca in 1888 AD and was influenced by the Wahhabis. When he returned, he started a reform movement advocating for a return “back to Quran and Sunnah”. |

| 4 | Salafiyah is a sect of Islam in China founded in the 1930s by Akhond Ma Debao. He traveled to Mecca in 1936 AD and took back several Wahhabi books. |

| 5 | Chinese Muslims traditionally refer to religious authority figures as Akhond (阿訇), a Persian term meaning “teacher”. Typically, it is synonymous with the Arabic term “Imam”. But, in Xi’an, particularly in certain mosques such as the Grand Mosque, Imam and Akhond are two different positions. The Imam is selected from local Muslim scholars and oversees local rituals and customs, while the Ahkond is an employed religious authority responsible for the madrasa, leading collective prayers, giving lectures on the Friday prayer, and providing interpretations of Sharia law. |

| 6 | The Xi’an version of the collection of poems includes 28 poems, each of which also has a Chinese translation. We cannot identify the original source of every poem, but some of them are very similar to the poems used in Hezhou (see the next section of this paper). |

| 7 | This is called the Bao-jia system in ancient China. The basic-level government under the county in the 1940s included “Xiang” (township), “Bao” (village), and “Jia” (group). At the same time, there was still another autonomous system at work, as these scholars observed. |

| 8 | The terms “old sect” and “new sect” in China are relative and subject to change over time. In the 1780s, Jahriyah was considered a “new sect” when compared with Khufiyah. Similarly, by the 20th century, Ikhwan began to be referred to as a “new sect”, with all the sects before it (including all the Sufi orders) being labelled as “old sects”. |

| 9 | The full name of this book is Maulud al-Nabī’, which belongs to the Qadiriyyah Sufi order, said to be written by ‘Idrūs. According to professor Ding Shiren, this person is mostly supposed to be a Yemen Sufi named Hussein ibn Abdullah ‘Idrūs (Ding 2023, p. 352). A famous Sufi master of China, Sheikh Ma Laichi (马来迟, 1681–1766), the founder of the Hua-si branch of Khufiyah Sufi order, traveled to Yemen, Mecca, Baghdad, Damascus, and Cairo during 1728–1734 AD. When he returned, he took several books with him, including one copy of the Maulud al-Nabī’. Since then, this copy of praising poems was used and spread throughout northwest China, especially among Sufis. We have no further information beyond these legends. |

| 10 | Madāyah is the title of another famous collection of Arabic poems in China. According to professor Ding Shiren, the popular version of this book in Hezhou is drawn from three original sources: (1) Mawlud al-Nabī’ Sharaf al-Anām; (2) selected components of Mawlid al-Barzanji; and (3) selected components of Qasīdath al-Burdath (Ding 2023, p. 347). We do not know exactly when and how these texts came into China, or who edited this version by merging different sources together. Mawlud al-Nabī’ Sharaf al-Anām is the main part of Madāyah. The author is supposed to be a Yemeni Sufi named ‘Ahmad ibn ‘Alī ibn Qāsim. The book includes three parts: (1) the poem begins with “al-Salām”; (2) the main components consist of rāwi (prose), bayti (couplet) and jawāb (response); and (3) the poems begin with Da-zan (the Grand Praising) and finish with Wan-zan (the Complete Praising) (Ding 2023, p. 347). Mawlid al-Barzanji is an Arabic collection of poems written by a Medina scholar named Ja’far ibn Hussein ‘Abud’l-Karīm (1715–1763 AD) (Ding 2023, p. 353). Qasīdath al-Burdath is so famous all over the world that no reference is needed. |

| 11 | It is said that the Prophet Zakariya was killed with a saw. Before he died, he remembered these three dhikrs. This is the reason for the term the “Minshār dhikr”. See (Ding 2023, p. 348). |

References

- Akah, Josephine N., Aloysius C. Obiwulu, and Anthony C. Ajah. 2020. Recognition and Justification: Towards a Rationalization Approach to Inculturation. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 3: a6186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Shouyi. 1953. 回民起义 IV [Rebellion of the Hui People IV]. Shanghai: Shenzhou Guoguang She. [Google Scholar]

- Ballano, Vivencio. 2020. Inculturation, Anthropology, and the Empirical Dimension of Evangelization. Religions 2: 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourmaud, Philippe. 2009. The Political and Religious Dynamics of the Mawlid al-Nabawi in Mandatory Palestine. Archiv Orientální 4: 317. [Google Scholar]

- Compilation Group of General Situation of Linxia Hui Autonomous Prefecture. 1986. 临夏回族自治州概况 [General Situation of Linxia Hui Autonomous Prefecture]. Lanzhou: Gansu People’s Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Cong, Enlin. 2016. 穆斯林为什么举办圣纪 [Why do Muslim Hold Mawlid al-Nabi?]. Chinese Muslim 1: 40–43. [Google Scholar]

- Connerton, Paul. 1989. How Societies Remember. New York: Cambridge University. [Google Scholar]

- Crollius, Ary A. Roest. 1978. What Is so New about Inculturation? A Concept and Its Implications. Gregorianum 4: 721–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Shiren, ed. 2023. 中国阿拉伯波斯语文献提要 [Synopses of Arabic and Persian Literature in China]. Beijing: China Social Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- Erie, Matthew S. 2016. China and Islam: The Prophet, The Party, and Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, Xiaotong. 2011. 乡土中国·生育制度·乡土重建 [From the Soil: The Foundation of Chinese Society · Fertility System · Reconstructing Rural China]. Beijing: The Commercial Press. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Fukuan. 1997. 陕西回族史 [History of the Hui People in Shaanxi]. Xi’an: Shaanxi People’s Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman, Maurice. 1974. The Sociological Study of Chinese Religion. In Religion and Ritual in Chinese Society. Edited by Arthur P. Wolf. Standford: Standford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gansu Provincial Library. 1984. 西北民族宗教史料文摘(甘肃分册) [Abstracts of Historical Materials of Northwest Minzu and Religions (Gansu Volume)]. Lanzhou: Gansu Provincial Library. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Fayuan. 1992. 云南回族乡情调查——现状与发展研究 [An Investigation of The Rural Hui people in Yunnan: Research on the Present Situation and Development]. Kunming: Minzu Publishing House of Yunnan. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Zhanfu. 2002. 民国时期文人笔下的河州回族文化 [The culture of Hui People in Hezhou Written by Literati during The Republic Era]. Chinese Muslim 3: 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, Clifford. 1973. The Interpretation of Culture: Selected Essays. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Gillette, Maris. 2008. Violence, the State, and a Chinese Muslim Ritual Remember. The Journal of Asian Studies 3: 1011–37. [Google Scholar]

- Gladney, Dru C. 1991. Muslim Chinese: Ethnic Nationalism in the People’s Republic. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gladney, Dru C. 1998. Ethnic Identity in China: The Making of a Muslim Minority. New York: Wadsworth Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, Guangtian. 2022. The Sound of Salvation: Voice, Gender, and the Sufi Mediascape in China. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Halbwachs, Maurice. 1992. On Collective Memory. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, Joseph, and Donald Sybertz. 1996. Towards an African Narrative Theology. Nairobi: Paulines Publications Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Zhiyong, ed. 2011. 英汉社会科学大词典 [English Chinese Dictionary of Social Sciences]. Beijing: China Science Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Jupriani, Mukhayar, and Agusti Efi. 2020. Character Education Values of Attributes in Maulid Process in Sei Sariak Region VII Koto Pariaman.//2nd International Conference Innovation in Education (ICoIE 2020); Atlantis Press SARL. Available online: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ (accessed on 17 April 2023).

- Kaptein, Nico. 1992. Materials for the History of the Prophet Muhammad’s Birthday Celebration in Mecca. Der Islam Journal of the History and Culture of the Middle East 2: 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, Marion Holmes. 2007. The Birth of the Prophet Muhammad: Devotional Piety in Sunni Islam. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, Marion Holmes. 2018. Commemoration of the Prophet’s Birthday as a Domestic Ritual in Fifteenth and Sixteenth Century Damascus. In Domestic Devotions in the Early Modern World. Leiden. Edited by Marco Faini and Alessia Meneghin. Boston: Brill, pp. 167–80. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Jianbiao. 2000. 执着岁月:回族史与伊斯兰文化 [Years of Obsession: The History of the Hui and Islamic Culture]. Xi’an: Shaanxi People’s Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Xinghua. 2006. 河州伊斯兰教研究 [Studies on the Islam of Hezhou Region]. Journal of Hui Muslim Minority Studies 1: 109–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Weipin. 2004. 台湾汉人的神像:谈神如何具象 [The Statue of gods of Taiwan Chinese: How the gods to be Objectified]. In 物与物质文化 [Things and the Material Culture]. Edited by Huang Yinggui. Taibei: Institute of Ethnology of the Academia Sinica, pp. 335–77. [Google Scholar]

- Linxia Prefecture Annals Compilation Committee. 1993. 临夏回族自治州志 [Records of Linxia Hui Autonomous Prefecture]. Lanzhou: Gansu People’s Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Weidong. 2003. 清代陕西回族的人口变动 [On the Population Change of Shaanxi Hui in Qing Dynasty]. Journal of Hui Muslim Minority Studies 4: 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Changshou. 2003. 同治年间陕西回民起义历史调查记录 [Historical Investigation Records of Hui Uprising in Shaanxi during Tongzhi Period]. Xi’an: Shaanxi People’s Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Hui. 2013. “圣纪节”的宗教人类学考察与研究——以临夏地区为例 [The Investigate of “Mawlid” in a Perpective of Anthropology of Religion—Taking Linxia as an Example]. Master’s thesis, Northwest University for Nationalities, Lanzhou, China. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Jianjun. 2008. 西安回族民俗文化 [Folk Culture of Hui People in Xi’an]. Xi’an: San Qin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Liqiang, and Junqing Min. 2016. 伊斯兰教在中国本土化的古老传统——《圣纪节在中国》摄制活动纪实 [The Ancient Tradition of Islam Localized in China—A Documentary of the Filming Activities of The Mawlid-al-Nabi in China]. Chinese Muslim 2: 12–14+42–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Xuefeng. 2013. 从教门到民族——西南边地一个少数民族社群的民族史 [From Jiaomen to Nationality: The History of a Ethnic Minority Community in the Southwest Frontier]. Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Xuefeng, and Min Su, eds. 2019. 魁阁三学者文集 [Collected Essays of Three Scholars of Kuige]. Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mauss, Marcel. 2002. The Gift: The Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Minzu Affairs Commission of Tonghai County. 1991. 通海县少数民族志 [Records of Ethnic Groups in Tonghai County]. Kunming: Yunnan People’s Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Murata, Sachiko, William C. Chittick, and Tu Weiming. 2009. The Sage Learning of Liu Zhi: Islamic Thought in Confucian Terms. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nasr, Seyyed Hossein. 1999. Three Muslim Sages: Avicenna, Suhrawardi, Ibn Arabi. Lahore: Suhail Academy. [Google Scholar]

- Nche, Georege C., Lawrence N. Okwuosa, and Theresa C. Nwaoga. 2016. Revisiting the Concept of Inculturation in A Modern Africa: A Reflection on Salient Issues. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 72: a3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Parvez, Z. Fareen. 2014. Celebrating the Prophet: Religious Nationalism and the Politics of Milad-un-Nabi Festivals in India. Nations and Nationalism 20: 218–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierret, Thomas. 2012. Staging the Authority of the Ulama: The Celebration of the Mawlid in Urban Syria. In Ethnographies of Islam: Ritual Performances and Everyday Practices. Edited by Baudouin Dupret, Thomas Pierret, Paulo G. Pinto and Kathryn Spellman-Poots. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 93–101. [Google Scholar]

- Redfield, Robert, Ralph Linton, and Melville J. Herskovits. 1936. Memorandum for the Study of Acculturation. American Anthropologist 38: 149–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Gui. 2012. 传统的继承与重构:巍山回族圣纪节的当代变迁 [Inheritance and Reconstruction of Tradition: The Contemporary Change of Weishan Hui People’s Mawlid al-Nabi]. Ethno-National Studies 2: 44–54. [Google Scholar]

- Rong, Gui, Hacer zekiye Gönül, and Xiawan Zhang. 2016. Hui Muslims in China. Leuven: Leuven University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Said, Edward W. 1994. Culture and Imperialism. New York: A Division of Random House, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Schussman, Aviva. 1998. The Legitimacy and Nature of Mawlid al-Nabi: Analysis of a Fatwa. Islamic Law and Society 2: 214–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, Andrea L. 2015. Celebrating Muhammad’s Birthday in the Middle East Supporting or Complicating Muslim Identify Projects? In Identity Discourses and Communities in International Events, Festivals and Spectacles. Edited by Udo Merkel. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 192–206. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Victor. 1967. The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual. London: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Daiyu. 1999. 正教真诠 [The Real Commentary of the True Teaching]. Yinchuan: Ningxia People’s Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Mu, and Caixian Yu. 2007. 明清之际河州基层社会变革对穆斯林社会的影响 [The Influence of Hezhou’s Basic Social Reform on Muslim Society During The Ming and Qing Dynasties]. Studies in World Religions 2: 106–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Yuyu. 2008. 西方文论中的中国 [China in Western Literatures]. Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Xi’an People’s Government. 2023. 民族宗教 [Ethnic Minorities and Religions]. Available online: http://www.xa.gov.cn/sq/csgk/mzzj/1.html (accessed on 17 April 2023).

- Yang, Zhaojun, ed. 1994. 云南回族史(修订本) [History of Hui People in Yunnan]. Kunming: Minzu Publishing House of Yunan. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Jide, and Mang Xiao. 2001. 云南民族村寨调查:回族——通海纳古镇 [An Investigation on Villages of Minzu in Yunnan: Hui People In Nagu Town, Tonghai County]. Kunming: Yunnan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Jide, Rongkun Li, and Zuo Zhang. 2005. 云南伊斯兰教史 [The History of Islam in Yunnan]. Kunming: Yunnan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Zhengui, and Xiaojing Lei, eds. 2001. 中国回族金石录 [The Jinshilu of Hui People in China]. Yinchuan: Ningxia People’s Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Zhiqin. 2013. 北京牛街礼拜寺圣纪节研究 [Study on the Mawlid Festival of Niujie Mosque in Beijing]. Master’s thesis, Minzu University of China, Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Weidong. 2013. “双轨政治”转型与村治结构创新 [The Transformation of “Dual Track Politics” and Governance Structure Innovation in Chinese Villages]. Fudan Journal (Social Sciences) 1: 146–53+159–60. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Chuanbin. 2012. 回道对话与文化共享——宁夏固原二十里铺拱北的人类学解读 [The Dialogue between Islam and Daoism and Cultural Sharing: A anthropological Interpretation of the Er-shi-li-pu Qubbah of Guyuan, Ningxia]. N. W. Journal of Ethnology 4: 46–55. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Chuanbin, and Xuefeng Ma. 2004. 都市回族社会结构的范式问题探讨——以北京回族社区结构变迁为例 [A Paradigm Discussion on Social Structure of Urban Hui Muslim Minority: As the Case of Beijing]. Journal of Hui Muslim Minority Studies 3: 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Chuanbin, and Wenkui Ma. 2014. 回族砖雕中凤凰图案的宗教意蕴——基于临夏市伊斯兰教拱北建筑的象征人类学分析 [The Religious Meaning of the Phoenix in Brick-Carvings of Hui People: A Symbolic Anthropological Analysis of Architectures of Islamic Qubbah in Linxia]. Journal of Beifang University of Nationalities 3: 101–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Chuanbin, and Wenkui Ma. 2017. 回道对话:基于甘肃临夏大拱北门宦建筑中砖雕图案的象征分析 [Dialogue between Islam and Daoism: An Analysis on the Brick-Carving Images of the Sufi Architectures of the Grand Qubbah Tariq of Linxia, Gansu]. The World Religious Cultures 5: 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Weizhou. 1997. 陕西通史(民族卷) [General History of Shaanxi (Minzu Volume)]. Xi’an: Shaanxi Normal University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Xiaoxiao, and Rong Gui. 2013. 回族节日文化重构的几种类型——基于云南巍山回族圣纪节文化变迁的民族志研究 [On the Reconstruction Types of Ethnic Hui’s Cultural Festivals: An Ethnographic Study Based on Hui Mawlid Cultural Change in Weishan, Yunnan]. Journal of Hui Muslim Minority Studies 3: 80–86. [Google Scholar]

| Date | Place |

|---|---|

| 5 February 2018, Monday The 20th Day of the 12th Lunar Month | Yuanjia Village Mosque 袁家村清真寺 |

| 11 February 2018, Sunday The 26th Day of the 12th Lunar Month | YanLiang Mosque 阎良清真寺 |

| 15 February 2018, Thursday The 30th Day of the 12th Lunar Month Chinese New Year’s Eve | Beiguangji Street Mosque 北广济街清真寺 |

| 16 February 2018, Friday The 1st Day of the 1st Lunar Month Chinese New Year | Nancheng Mosque 南城清真寺 |

| 17 February 2018, Saturday The 2nd Day of the 1st Lunar Month | Old Sajinqiao Mosque 洒金桥清真古寺 |

| 18 February 2018, Sunday The 3rd Day of the 1st Lunar Month | Huajue Lane Mosque (The Grand Mosque) 西安化觉巷清真大寺 |

| 19 February 2018, Monday The 4th Day of the 1st Lunar Month | Xiaopiyuan Mosque 小皮院清真寺 |

| 20 February 2018, Tuesday The 5th Day of the 1st Lunar Month | Xiangmiyuan Lushan Mosque 香米园旅陕清真寺 |

| 21 February 2018, Wednesday The 6th Day of the 1st Lunar Month | Xiaoxuexi Line Mosque 小学习巷清真中寺 |

| 25 February 2018, Sunday The 10th Day of the 1st Lunar Month | Lintong Mosque 临潼清真寺 |

| 3 March 2018, Saturday The 16th Day of the 1st Lunar Month | Hansenzhai Mosque 韩森寨清真寺 |

| 11 March 2018, Sunday The 24th Day of the 1st Lunar Month | New Beiguan Mosque 北关清真新寺 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, C.; Shang, P.; Ma, W. The Prophet’s Day in China: A Study of the Inculturation of Islam in China, Based on Fieldwork in Xi’an, Najiaying, and Hezhou. Religions 2024, 15, 630. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060630

Zhou C, Shang P, Ma W. The Prophet’s Day in China: A Study of the Inculturation of Islam in China, Based on Fieldwork in Xi’an, Najiaying, and Hezhou. Religions. 2024; 15(6):630. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060630

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Chuanbin, Ping Shang, and Wenkui Ma. 2024. "The Prophet’s Day in China: A Study of the Inculturation of Islam in China, Based on Fieldwork in Xi’an, Najiaying, and Hezhou" Religions 15, no. 6: 630. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060630

APA StyleZhou, C., Shang, P., & Ma, W. (2024). The Prophet’s Day in China: A Study of the Inculturation of Islam in China, Based on Fieldwork in Xi’an, Najiaying, and Hezhou. Religions, 15(6), 630. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060630