The Russian Orthodox Mission in Beijing (XVIII–XX Centuries): Historiography, Missionary Role, and Contemporary Assessment

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What narratives have Chinese and Russian records constructed regarding the Russian Orthodox Mission in Beijing, and what novel interpretations emerge from these accounts?

- How is the Mission perceived as a driving force in the evolution of Sino–Russian relations, especially in terms of cultural and diplomatic engagements?

- What role did the Mission play in shaping the landscape of interpersonal exchanges between the peoples of China and Russia?

2. Historical Context of the Russian Orthodox Mission in Beijing

2.1. The Limited Adventures in 1715–1860

2.2. The Rapid Growth in 1858–1917

2.3. The Unexpected Shifts in 1917–1956

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The Russian Narratives on the History of the Russian Mission in Beijing

3.2. The Chinese Narratives on the History of the Russian Mission in Beijing

3.3. The Narrative Gap in the History of the Russian Mission in Beijing

3.4. Methodological Approach

4. Analysis and Discussion

4.1. Redefining Identity Myths in Historical Context

4.2. The Cultural Diplomacy in Bridging China and Russia

the greatest Sinologist of Russia and the entire European world of the nineteenth century; he was the first scholar to apply to Sinology the method of working only with sources, rather than relying on stereotypical information from Chinese encyclopedists.

4.3. Comparative Analysis of Mission Strategies and Western Counterparts

The results and consequences of Christian missionary activity in the second half of the 19th century are as significant as they are contradictory.

The academic and practical experiences provide a strong foundation for learning Chinese language, adapting to the culture, and performing missionary work in China.(Cao 2021)

As for the reasons why the Chinese joined the church, the vast majority of Chinese practiced Orthodoxy not to save their souls but to solve real-life problems. The Russian missionaries were aware of this from the outset, and while they continued to receive baptisms, most were clearly motivated by material rewards.

Until the end of the 19th century, the Russian Orthodox Mission was not actively engaged in missionary activity in China. The missionaries themselves did not believe in the possibility of a wide spread of Orthodoxy and Christianity in general in Chinese society.

Orthodox and Protestant churches have significant differences that have led to Christian schism. In parallel, they have developed their own distinctive styles of choosing and using external manifestations of communication media, subjects, and targets.

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

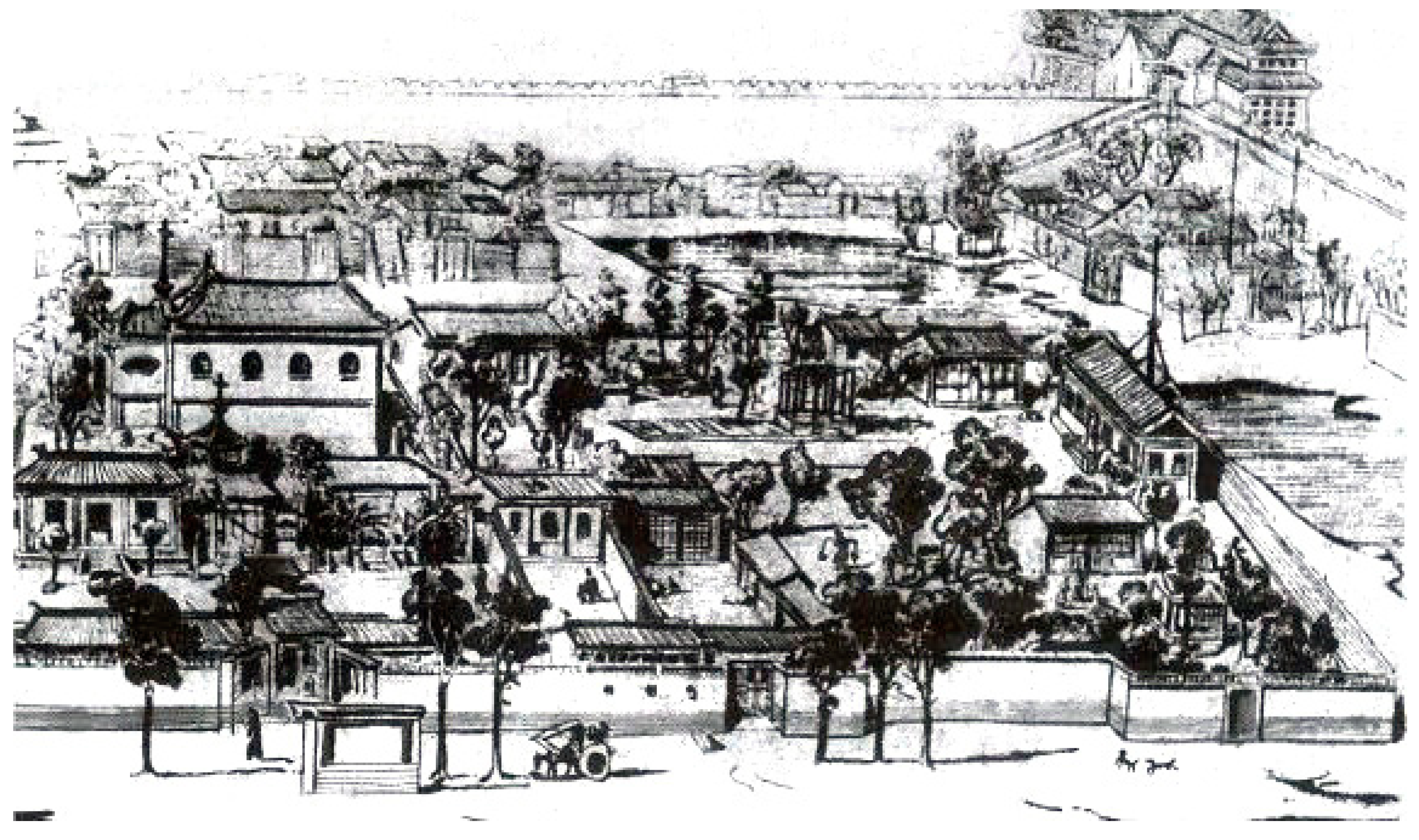

| 1 | https://www.orthodox.cn/images/1850beiguan.jpg, accessed on 25 April 2024. |

References

- Abramov, Nikolay. 1862. Ignatiy Korsakov, mitropolit Sibirskiy [Ignatiy Korsakov, Metropolitan of Siberia]. Strannik I: 155–67. [Google Scholar]

- Afinogenov, Gregory. 2015. Jesuit Conspirators and Russia’s East Asian Fur Trade, 1791–1807. Journal of Jesuit Studies 1: 56–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afinogenov, Gregory. 2020. Spies and Scholars: Chinese Secrets and Imperial Russia’s Quest For World Power. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, p. 384. [Google Scholar]

- Afonina, Ljubov’. 2017. Kitayskie pravoslavnye mucheniki 1900 g.: Analiz istoricheskih istochnikov i tserkovnoe pochitanie [Chinese Orthodox Martyrs of 1900: Analysis of Historical Sources and Church Veneration]. Obshchestvo i gosudarstvo v Kitae 47: 598–667. [Google Scholar]

- Afonina, Ljubov’. 2021. Vosstanie ihetuaney i pravoslavnye mucheniki v Kitae [The Yihetuan Rebellion and Orthodox Martyrs in China]. Moscow: Nauka, p. 559. [Google Scholar]

- Akulich, Anastasiia. 2022. “From the Seeds Sown in the Soil”: The Boxer Rebellion and the Awakening of Russian Missionary Activity in China (1900–1917). Ab Imperio 4: 61–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrov, Boris, ed. 2006. Bey-guan’: Kratkaya istoriya Rossiyskoy duhovnoy missii v Kitae [Bei-Guan: A Brief History of the Russian Spiritual Mission in China]. Moscow and St. Petersburg: Alliance-Archso, p. 217. [Google Scholar]

- Alekseev, Vasiliy. 1982. Nauka o Vostoke: Stat’i i dokumenty [The Science of the East: Articles and Documents]. Moscow: Nauka, p. 535. [Google Scholar]

- Amfilohiy (Lutovinov). 1898a. Iz istorii hristianstva v Kitae: Period perviy: S nachala hristianskoy ery do padeniya yuanskoy dinastii v 1369 g. [From the History of Christianity in China: Period One: From the Beginning of the Christian Era to the Fall of the Yuan Dynasty in 1369]. Moscow: Publ. of A.I. Snegirevaya, p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Amfilohiy (Lutovinov). 1898b. Nachatki grammatiki kitayskogo razgovornogo yazyka prisposobitel’no k formam yazyka russkogo [Beginnings of Grammar of the Chinese Spoken Language Adapted to the Forms of the Russian Language]. St. Petersburg: tip. Imp. Acad. nauk, p. 69. [Google Scholar]

- Archimandrite Peter. 1823. Zhurnal, vedennyj v Pekine po sluchaju pribytija iz Rossijskogo gosudarstva poslannika Nikolaja Gavrilovicha Spafarija [Journal kept in Beijing on the Occasion of the Arrival from the Russian State of the Envoy Nikolai Gavrilovich Spafarya]. Sibirskij Vestnik 3: 29–100. [Google Scholar]

- Avraamiy. 1916. Kratkaya istoriya Russkoi pravoslavnoi missii v Kitae, sostavlennaya po sluchayu ispolnivshegosya v 1913 godu dvukhsotletnego yubileya ee sushchestvovaniya [A Brief History of the Russian Orthodox Mission in China, Composed on the Occasion Fulfilled in 1913 Bicentennial Anniversary of its Existence]. Beijing: Tip. Usp. monastyrya, p. 223. [Google Scholar]

- Avraamiy 阿夫拉米神父, ed. 2016. Li Shi Shang Bei Jing De E Guo Dong Zheng Jiao Shi Tuan 历史上北京的俄国东正教使团 [A Brief History of the Russian Orthodox Mission in China]. Ruomei Liu 柳若梅, trans. Zhengzhou: Daxiang Chubanshe. 259p. [Google Scholar]

- Bartenev, Petr. 1893. Iz pis’ma Preosvyashchennogo Guriya k I. I. Palimpsestovu o perevode Novogo Zaveta na kitajskij yazyk. Russkij arhiv 11: 394. [Google Scholar]

- Bartol’d, Vasiliy. 2014. Istoriya izucheniya Vostoka v Evrope i Rossii [History of studying of the East in Europe and Russia]. Moscow: URSS, p. 317. [Google Scholar]

- Bolgurtsev, B. N. 1996. Russkiy flot na Dal’nem Vostoke (1860–1861 gg.): Pekinskiy dogovor i Tsusimskiy intsident [Russian Fleet in the Far East (1860–1861): The Treaty of Beijing and the Tsushima Incident]. Vladivostok: Dal’nauka, p. 133. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Xianwen 曹贤文. 2021. Ming mo qing chu ru hua ye su hui chuan jiao tuan de han yu jiao xue mo shi 明末清初入华耶稣会传教团的汉语教学模式 [Chinese language teaching patterns in Jesuit missions to China in the late Ming and early Qing dynasties]. Dui Wai Han Yu Yan Jiu 1: 50–61. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Kaike 陈开科. 2006a. 19 shi ji e guo han xue da shi ba la di de sheng ping he xue shu 19世纪俄国汉学大师巴拉第的生平和学术 [Life and research of Russian great sinologist Palladius in 19th century]. Han Xue Yan Jiu Tong Xun 25: 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Kaike 陈开科. 2006b. ba la di yu qing dai xi bei shi di xue jia de xue shu yin yuan 巴拉第与清代西北史地学家的学术因缘 [Academic Connections of Palladius and the Northwest Historians of the Qing Dynasty]. In Xi Yu Wen Shi. Beijing: Ke xue chu ban she, vol. 1, pp. 179–94. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Kaike 陈开科. 2008. Ba La Di Yu Wan Qing Zhong E Wai Jiao Guan Xi 巴拉第与晚清中俄外交关系 [Palladius and Sino-Russian Diplomatic Relations in the Late Qing Dynasty]. Shanghai: Shang Hai Shu Dian Chu Ban She, p. 559. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Kaike 陈开科. 2010. Guan Yu Zhong E 《Tian Jin Tiao Yue》 De Liang Ge Wen Ti 关于中俄《天津条约》的两个问题 [Two Issues Concerning the Sino-Russian Treaty of Tianjin]. In Jin Dai Zhong Guo: Zheng Zhi Yu Wai Jiao. Beijing: She ke wen xian chu ban she, vol. 2, pp. 117–42. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Zhen 程真, and Ziyuan Li 李滋媛. 2008. Guo tu cang e guo dong zheng jiao bei jing jiao shi tuan wen xian kao lüe 国图藏俄国东正教北京教士团文献考略 [Study on the literature on the Russian Spiritual Mission in Beijing preserved in the National Library of China]. Guo Jia Tu Shu Guan Xue Kan 2: 84–88. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Guiju 戴桂菊. 2014. E luo si dong zheng jiao hui de wai jiao zhi neng 俄罗斯东正教会的外交职能 [Diplomatic functions of the Russian Orthodox Church]. Shi Jie Zong Jiao Wen Hua 2: 46–49. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Guiju 戴桂菊. 2018. 20 shi ji 20–50 nian dai e guo zhu hua dong zheng jiao chuan jiao tuan ming yun bian qian 20世纪20–50年代俄国驻华东正教传教团命运变迁 [Vicissitude of the Russian Orthodox Churchmen in China from 1920s to 1950s]. E Luo Si Xue Kan 3: 51–63. [Google Scholar]

- Datsyshen, Vladimir. 2007. Khristianstvo v Kitae: Istoriya i sovremennost’ [Christianity in China: History and Modernity]. Moscow: Nauch.-obrazovatel’nyj forum po mezhdunar. otnosheniyam, p. 240. [Google Scholar]

- Datsyshen, Vladimir. 2010. Istoriya Rossiiskoi Dukhovnoi Missii v Kitae [History of the Russian Spiritual Mission in China]. Hong Kong: p. 448. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Mei. 2015. From Xinjiang to Australia: Shifted Meanings of Being Russian. Inner Asia 17: 243–72. [Google Scholar]

- Dmitrenko, Alexander. 2017. Istoriya perevoda Novogo Zaveta na kitayskiy yazyk svt. Guriem Karpovym [History of the translation of the New Testament into Chinese by St. Guriy Karpov]. Obshchestvo i gosudarstvo v Kitae [Society and State in China] 47: 232–38. [Google Scholar]

- Dmitrievskiy, Aleksei. 1909. Graf N. P. Ignat’ev, kak tserkovno-politicheskiy deyatel’ na pravoslavnom Vostoke [Count N.P. Ignatiev as a church-political figure in the Orthodox East]. St. Petersburg: tip. V. Kirshbauma, p. 79. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Yi 杜祎, and Yumei Xie 谢玉梅. 2016. Dong zheng jiao zai zhong guo yan jiu: hui gu yu zhan wang 东正教在中国研究: 回顾与展望 [Orthodox Christianity in China Studies: Review and Prospects]. Zong Jiao Yu Mei Guo She Hui 1: 290–308+329. [Google Scholar]

- Fedorenko, Nikolay. 1974. Iakinf Bichurin, osnovatel’ russkogo kitaevedeniya [Iakinf Bichurin, the Founder of Chinese Studies in Russia]. Izvestiya AN SSSR. Seriya literatura i yazyk 33: 341–51. [Google Scholar]

- Golovin, Sergei. 2013. Rossiiskaya dukhovnaya missiya v Kitae: Istoricheskii ocherk [Russian Spiritual Mission in China: A Historical Sketch]. Blagoveshchensk: Izd-vo BGPU, p. 284. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Fangyan 胡方艳, and Qian Wu 吴茜. 2015. Qing zhi min guo jian xin jiang yi li de dong zheng jiao 清至民国间新疆伊犁的东正教 [Orthodox Christianity in Ili, Xinjiang, between the Qing Dynasty and the Republic of China]. Zong Jiao Xue Yan Jiu 3: 256–61. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Dingtian 黄定天. 2013. Zhong E Guan Xi Tong Shi 中俄关系通史 [General History of Sino-Russian Relations]. Beijing: Ren Min Chu Ban She, p. 397. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Paulos, and Nilkolay Samoylov. 2018. Orthodoxy in China: History, Current State and Prospects for Studies. International Journal of Sino-Western Studies 14: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ipatova, A. 1991. Pis’ma arhimandrita Polikarpa (iz istorii Rossiyskoy duhovnoy missii v Pekin) [Letters of Archimandrite Polycarp (from the history of the Russian Spiritual Mission to Beijing)]. Problemy Dal’nego Vostoka 2: 91–97. [Google Scholar]

- Izdanie Ministerstva inostrannyh del. 1889. Sbornik dogovorov Rossii s Kitaem 1689–1881gg. [Collection of Treaties between Russia and China 1689–1881]. St. Petersburg: tipografiya imperatorskoj akademii nauk, pp. 110–21. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Yong 姜勇. 2008. Dong zheng jiao zai xin jiang ta cheng di qu chuan bo de li shi ji xian zhuang 东正教在新疆塔城地区传播的历史及现状 [The History and Present Situation of the Spread of Orthodox Christianity in the Tacheng Region of Xinjiang]. Xin Jiang Shi Fan Da Xue Xue Bao (Zhe Xue She Hui Ke Xue Ban) 1: 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kafarov, Peter. 1902. Kommentarii arkhimandrita Palladiia Kafarova na puteshestvie Marko Polo po Severnomu Kitaiu [Archimandrite Palladius Kafarov’s commentary on Marco Polo’s journey through northern China]. In Izvestiia Imperatorskogo Russkogo geograficheskogo obshchestva. St. Petersburg: Geogr. izv, vol. 38, pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Khokhlov, Alexander. 1970. P.I. Kamenskii i ego trudy po istorii Kitaya [P.I. Kamensky and his writings on the history of China]. In Konferentsiya aspirantov i molodykh nauchnykh sotrudnikov IV AN SSSR [Conference of Students and Young Scientific Workers of the IOS of AS of USSR]. Moscow: IV AN SSSR, pp. 139–40. [Google Scholar]

- Khokhlov, Alexander. 1978. N.Ya. Bichurin i ego trudy o Mongolii i Kitae [N.Ya. Bichurin and his works about Mongolia and China]. Voprosy istorii 1: 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Khokhlov, Alexander. 1979. Ob istochnikovedcheskoi baze rabot N.Ya. Bichurina o tsinskom Kitae [About the source database of the works of N. I. Bichurina about Qing China]. Narody Azii i Afriki 1: 129–37. [Google Scholar]

- Khokhlov, Alexander. 1996. Rossiyskaya pravoslavnaya missiya v Pekine i kitayskie perevody hristianskih knig [The Russian Orthodox Mission in Beijing and Chinese translations of Christian books]. In Kitayskoe yazykoznanie. VIII Mezhdunarodnaya konferentsiya. Materialy [Chinese Linguistics. VIII International Conference. Materials]. Moscow: tip. Instituta yazykoznaniya RAN, pp. 160–64. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Georgij, and Petr Shastitko, eds. 1990. Istoriya otechestvennogo vostokovedeniya do serediny XIX veka [The history of Russian Oriental studies until the mid-nineteenth century]. Moscow: Nauka, p. 439. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Loretta E., and Chengyi Zhou. 2021. The Russian Orthodox Community in Hong Kong: Religion, Ethnicity, and Intercultural Relations. Lanham and London: Lexington Books, p. 269. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Weili 李伟丽. 2005. Qing dai qian qi e guo yu xi fang chuan jiao shi zai hua chuan jiao cha yi zhi jian xi 清代前期俄国与西方传教士在华传教差异之简析 [A Brief Analysis of the Differences between Russian and Western Missionaries in China in the Early Qing Dynasty]. Hua Bei Shui Li Shui Dian Xue Yuan Xue Bao (She Ke Ban) 1: 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Lomanov, A. V. 2007. Rossiyskaya duhovnaya missiya v Kitae [Russian Spiritual Mission in China]. In Duhovnaya zhizn’ Kitaya: Entsiklopediya [Spiritual Life of China: Encyclopedia]. Moscow: Vostochnaya literature, vol. 2, pp. 332–52. [Google Scholar]

- Lukin, A. V. 2013. Status Kitayskoy avtonomnoy pravoslavnoy tserkvi i perspektivy pravoslaviya v Kitae. In Analiticheskie DOKLADY [The Status of the Chinese Autonomous Orthodox Church and the Prospects of Orthodoxy in China. Analytical REPORTS]. Moscow: MGIMO—University, vol. 39. [Google Scholar]

- Meador, J. 2021. Cossacks into Manchus: Transfrontier Intermediaries in Inner Northeast Asia. Ab Imperio 3: 75–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miasnikov, V. S., and I. F. Popova. 2002. Vklad o. Iakinfa v mirovuyu sinologiyu. K 225-letiyu so dnya rozhdeniya chlena-korrespondenta N. Ya. Bichurina [Contribution of Fr. Iakinf’s contribution to the world sinology. To the 225th anniversary of the birth of Corresponding Member N. Y. Bichurin]. Vestnik Rossiyskoy Akademii nauk 72: 1099–106. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolai (Adoratskii). 1887. Pravoslavnaya Missiya v Kitae za 200 let eya sushchestvovaniya: Opyt tserkovno-istoricheskogo issledovaniya po arkhivnym dokumentam [Orthodox Mission in China for 200 Years of Her Existence: The Experience of Church-Historical Research on Archival Documents]. Kazan: tipografiya Imperatorskogo Universiteta, vols. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolai (Adoratskii) 尼古拉(阿多拉茨基). 2007. Dong zheng jiao zai hua liang bai nian shi 东正教在华两百年史 [Bicentennial history of Orthodoxy in China]. Translated by Guodong Yan 阎国栋, and Yuqiu Xiao 肖玉秋. Guangzhou: Guangdong renmin chubanshe, p. 320. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, Zhesheng 欧阳哲生. 2016a. E guo dong zheng jiao chuan jiao tuan de guan li, zi chan ji qi bei jing wen xian (1716—1859) 俄国东正教传教团的管理, 资产及其北京文献 (1716—1859) [The Management, Assets and the Beijing Literature of the Russian Orthodox Missionary (1716—1859)]. Hua Zhong Shi Fan Da Xue Xue Bao (Ren Wen She Hui Ke Xue Ban) 3: 127–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, Zhesheng 欧阳哲生. 2016b. E guo dong zheng jiao chuan jiao tuan zai jing huo dong shu ping (1716–1859) 俄国东正教传教团在京活动述评 (1716–1859) [Review of the Activities of the Russian Orthodox Mission in Beijing (1716–1859)]. An Hui Shi Xue 1: 124–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ovsyannikov, S. 2014. Dve zhizni arhimandrita Polikarpa Tugarinova [Two lives of Archimandrite Polikarp Tugarinov]. Rybnaya sloboda: Istoriko-kul’turniy zhurnal Rybinskoy eparhii 7: 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Palladius (Kafarov). 1872. Dorozhnye zametki na puti ot Pekina do Blagoveshchenska cherez Man’chzhuriyu, v 1870 godu [Road notes on the way from Peking to Blagoveshchensk through Manchuria, in 1870]. St. Petersburg: tip. V. Bezobrazova i K°, p. 130. [Google Scholar]

- Palladius (Kafarov), and Pavel Popov. 1888. Kitaysko-russkiy slovar’ [Chinese-Russian Dictionary]. Beijing: tip. Tung-wen-guan, vols. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, Tatiana. 1998. Review of Posol’stvo Yu. A. Golovkina i 9—â Rossijskaâ Duhovnaya Missiâ v Kitae. (Provoslavie na Dal’nem Vostoke. Vypusk 2. Pamâti svâitelâ Nikolaâ apostola âponii 1836–1912), by I. T. Moroz. Revue Bibliographique de Sinologie 16: 147–48. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, Tatiana. 2000. Arhim. Ilarion (Lezhayskiy) i pervaya Pekinskaya duhovnaya missiya (1717–1729) [Archim. Hilarion (Lezhaysky) and the First Beijing Spiritual Mission (1717–1729)]. Istoricheskiy vestnik 6: 196–202. [Google Scholar]

- Pogosyan, Lilit. 2016. Rossiysko-kitayskie otnosheniya XVIII veka [Russian-Chinese relations of the XVIII century]. Nauchno-metodicheskiy elektronniy zhurnal «Kontsept» 33: 83–87. [Google Scholar]

- Pozdnyaev, Dionisij. 1998. Pravoslavie v Kitae: (1900–1997) [Orthodoxy in China: (1900–1997)]. Moscow: Izd-vo Svyato-Vladim. Bratstva, p. 278. [Google Scholar]

- Rong, Jie 荣洁, Wei Zhao 赵为, Mengxue Zhao 赵梦雪, and Jie Zheng 郑捷. 2011. E Qiao yu Hei Long Jiang Wen Hua: E Luo Si Qiao Min Dui Ha Er Bin de Ying Xiang 俄侨与黑龙江文化:俄罗斯侨民对哈尔滨的影响 [Russian Emigrants and the Culture of Heilongjiang: The Influence of Russian Emigrants on Harbin]. Harbin: Hei Long Jiang Da Xue Chu Ban She, p. 224. [Google Scholar]

- Samoylov, Nikolay. 2016. Russian-Chinese Cultural Exchanges in the Early Modern Period: Missionaries, Sinologists, and Artists. In Reshaping the Boundaries: The Christian Intersection of China and the West in the Modern Era. Edited by Song Gang. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, pp. 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Samoylov, Nikolay. 2020. Konferentsii «Pravoslavie na Dal’nem vostoke» (1991–2003 gg.): Stanovlenie unikal’nogo nauchnogo napravleniya [Conference “Orthodoxy in the Far East” (1991–2003): The formation of a unique scientific direction]. Vestnik Istoricheskogo obshchestva Sankt-Peterburgskoy Duhovnoy Akademii 5: 24–50. [Google Scholar]

- Samoylov, Nikolay. 2021. Izuchenie istorii Rossiyskoy duhovnoy missii v Kitae: Osnovnye napravleniya, podhody i perspektivy [Studying the history of the Russian Spiritual Mission in China: Main directions, approaches and prospects]. Vestnik Istoricheskogo obshchestva Sankt-Peterburgskoy Duhovnoy Akademii 7: 48–76. [Google Scholar]

- Samoylov, Nikolay, ed. 1993. Pravoslavie na Dal’nem Vostoke. 275-letie russkoi dukhovnoi missii v Kitae: Sb. st/Vost. f-t Peterb. un-ta [Orthodoxy in the far East. 275-Anniversary of Russian Spiritual Mission in China: Collection of papers by Oriental faculty St. Petersburg. Univ.]. Saint Petersburg: Andreev i synov’ya, p. 159. [Google Scholar]

- Selivanovskii, Victor, ed. 2013. Pravoslavie v Kitae [Orthodoxy in China]. Blagoveshchensk: Amurskaya yarmarka, p. 65. [Google Scholar]

- Shubina, Svetlana. 1998. Russkaya pravoslavnaya missiya v Kitai (XVIII—nachalo XX vv.) [Russian Orthodox Mission in China (XVIII—Beginning of XX Centuries)]: diss. … kand. ist. nauk. Yaroslavl: Yaroslavskii gosudarstvennyi universitet, p. 533. [Google Scholar]

- Skachkov, Petr. 1960a. Pervyi prepodavatel’ kitaiskogo i man’chzhurskogo iazykov v Rossii [The First Teachers of Chinese and Manchu Languages in Russia]. Problemy vostokovedeniia 3: 198–201. [Google Scholar]

- Skachkov, Petr. 1960b. Znachenie rukopisnogo naslediia russkikh kitaevedov [Significance of Manuscript Heritage of Russian Chinese Studies]. Voprosy istorii 1: 116–23. [Google Scholar]

- Skachkov, Petr. 1977. Ocherki Istorii Russkogo Kitaevedeniya [Sketches of History of Russian Sinology]. Moscow: Nauka, p. 505. [Google Scholar]

- Smorzhevskii, Hieromonk Feodosii. 2016. Notes on the Jesuits in China. Translated by Afinogenov Gregory. Chestnut Hill: Institute of Jesuits Sources, Boston College, p. 116. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Shulin 谭树林. 2002. Bei jing chuan jiao shi tuan yu e guo zao qi han xue 北京传教士团与俄国早期汉学 [The Spiritual Mission in Beijing and Early Chinese Studies in Russia]. Shan Dong Shi Fan Da Xue Xue Bao 5: 99–101. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Tianyu 谭天宇. 2015. shi xi zhong e 《qia ke tu tiao yue》 dui e luo si zhu bei jing dong zheng jiao chuan jiao tuan de ying xiang 试析中俄《恰克图条约》对俄罗斯驻北京东正教传教团的影响 [An Analysis of the Influence of Sino–Russian Treaty of Kyakhta on Russian Orthodox Mission in Beijing]. Chi Feng Xue Yuan Xue Bao (Han Wen Zhe Xue She Hui Ke Xue Ban) 9: 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Ge 唐戈. 2001. Xian cun de zhong guo dong zheng jiao jiao tang 现存的中国东正教教堂 [The Existing Chinese Orthodox Churches]. Shi Jie Zong Jiao Wen Hua 3: 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Ge 唐戈. 2003. Xun fang nei di san zuo dong zheng jiao tang jiu zhi寻访内地三座东正教堂旧址 [Visiting former addresses of three Orthodox churches in China]. Shi Jie Zong Jiao Wen Hua 3: 33–35. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Yuan 陶源, and Pin Nie 聂品. 2019. Zhong Guo he E Luo Si Ren Wen Jiao Liu Shi (17 Shi Ji Zhi Jin) 中国和俄罗斯人文交流史(17世纪至今) [History of Humanitarian Exchanges between China and Russia (17th Century to the Present)]. Beijing: Ke xue chu ban she, p. 229. [Google Scholar]

- Tikhvinskii, Sergei. 1988. Vydayushchiisya russkii kitaeved N.Ya. Bichurin: k 200-letiyu so dnya rozhdeniya [An Outstanding Russian Sinologist N.Ya. Bichurin: To the 200-th Anniversary from Birthday]. In Kitai i Vsemirnaya istoriya. Moscow: Nauka, p. 591. [Google Scholar]

- Tikhvinskii, Sergei, ed. 1997. Istoriya Rossiiskoi dukhovnoi missii v Kitae: Sb. st [History of the Russian Spiritual Mission in China: Collection of Papers]. Moscow: Izd-vo Svyato-Vladimir. bratstva, p. 414. [Google Scholar]

- Titarenko, Mihail, ed. 2010. Pravoslavie v Kitae [Orthodoxy in China]. Moscow: Otdel vneshnikh tserkovnykh svyazei Moskovskogo Patriarkhata, p. 251. [Google Scholar]

- Veselovskii, Nikolay, ed. 1905. Materialy dlya istorii Rossiiskoi dukhovnoi missii v Pekine [Materials for the History of the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission in Beijing]. Saint-Petersburg: tip. Glav. upr. Udelov, vol. 1, p. 72. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Lina 王丽娜. 2021. Er Shi Shi Ji Ha Er Bin Dong Zheng Jiao yu Ji Du Xin Jiao Chuan Bo Fang Shi Bi Jiao Yan Jiu 二十世纪哈尔滨东正教与基督新教传播方式比较研究 [Comparative Study on the Spread Modes between Harbin Orthodox and Protestantism in the 20th Century]. Ph.D. thesis, Heilongjiang University, Harbin, China; p. 260. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Zhijun 王志军. 2015. Ha er bin e luo si dong zheng jiao shi yan jiu zong shu 哈尔滨俄罗斯东正教史研究综述 [A Summary of the Studies on the Russian Orthodox History in Harbin]. Shi Jie Zong Jiao Wen Hua 6: 140–57. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Zhijun 王志军, and Meihua Wang 王美华. 2022. 20 shi ji shang ban ye ha er bin e luo si dong zheng jiao shi shu lun 20世纪上半叶哈尔滨俄罗斯东正教史述论 [A historical account of the Russian Orthodox Church in Harbin in the first half of the 20th century]. Shi Jie Zong Jiao Yan Jiu 12: 102–12. [Google Scholar]

- Widmer, Eric. 1976. The Russian Ecclesiastical Mission in Peking During the Eighteenth Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Asia Center, p. 262. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Yuqiu 肖玉秋. 2003. 18 shi ji e guo lai hua liu xue sheng ji qi han xue yan jiu 18世纪俄国来华留学生及其汉学研究 [Russian Students in China in the Eighteenth Century and Their Study of Sinology]. Han Xue Yan Jiu, 172–84. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Yuqiu 肖玉秋. 2005. Shi lun e guo dong zheng jiao zhu bei jing chuan jiao shi tuan wen hua yu wai jiao huo dong 试论俄国东正教驻北京传教士团文化与外交活动 [On the cultural and diplomatic activities of Russian ecclesiastical mission in Beijing]. Shi Jie Li Shi 6: 66–75. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Yuqiu 肖玉秋. 2006. E guo zhu bei jing chuan jiao shi tuan dong zheng jiao jing shu han yi yu kan yin huo dong shu lüe 俄国驻北京传教士团东正教经书汉译与刊印活动述略 [About the translation and publication of Orthodox literature to Chinese language of the Russian ecclesiastical mission in Beijing]. Shi Jie Zong Jiao Yan Jiu 1: 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Yuqiu 肖玉秋. 2007. 19 shi ji xia ban qi e guo dong zheng jiao zhu bei jing chuan jiao shi tuan zong jiao huo dong fen xi 19世纪下半期俄国东正教驻北京传教士团宗教活动分析 [Analysis of the Religious Activities of the Russian Orthodox Mission in Beijing in the Second Half of the Nineteenth Century]. Shi Jie Jin Xian Dai Shi Yan Jiu, 207–21. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Yuqiu 肖玉秋. 2008a. 20 shi ji chu e guo dong zheng jiao zhu bei jing chuan jiao shi tuan zong jiao huo dong fen xi 20世纪初俄国东正教驻北京传教士团宗教活动分析 [Analysis of the Religious Activities of the Russian Orthodox Mission in Beijing at the Beginning of the 20th Century]. Shi Jie Jin Xian Dai Shi Yan Jiu, 167–84+324. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Yuqiu 肖玉秋. 2008b. Shi lun qing dai zhong e wen hua jiao liu de bu ping heng xing 试论清代中俄文化交流的不平衡性 [Study of the Imbalance of Sino-Russian Cultural Exchanges in the Qing Dynasty]. Shi xue ji kan 4: 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Yuqiu 肖玉秋. 2008c. Qing ji e luo si wen guan yan pin e ren jiao xi yan jiu 清季俄罗斯文馆延聘俄人教习研究 [A Study of the Employment of Russian Teachers in the Russian School in the Qing Empire]. Shi Xue Yue Kan 12: 80–88. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Yuqiu 肖玉秋. 2009. E Guo Chuan Jiao Tuan yu Qing Dai Zhong E Wen Hua Jiao Liu 俄国传教团与清代中俄文化交流 [Russian Orthodox Missions and Sino-Russian Cultural Exchange in the Qing Dynasty]. Tianjin: Tian Jin Ren Min Chu Ban She, p. 310. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Yuqiu 肖玉秋. 2010a. 1917 Nian qian e guo zai hua dong zheng jiao chuan jiao shi yu tian zhu jiao he xin jiao chuan jiao shi 1917年前俄国在华东正教传教士与天主教和新教传教士 [Orthodox missionaries from Russia and the Catholic, Protestant missionaries in China before 1917]. Shi Jie Li Shi 5: 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Yuqiu 肖玉秋. 2010b. E guo dong zheng jiao zhu bei jing chuan jiao tuan jian hu guan kao lüe 俄国东正教驻北京传教团监护官考略 [A study of officer history of Russian ecclesiastical mission in Beijing]. Qing Shi Yan Jiu 2: 125–30. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Yuqiu 肖玉秋. 2013. 1917 Nian qian e guo guan yu zhu bei jing chuan jiao tuan zheng ce de yan bian 1917年前俄国关于驻北京传教团政策的演变 [The changes in Russian policy on Russian ecclesiastical mission in Beijing untill 1917]. Nan Kai Xue Bao 1: 68–78. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Yuqiu 肖玉秋. 2021. E guo chuan jiao tuan cheng yuan zai bei jing de ri chang sheng huo —— yi 1840–1842 nian ge er si ji de jia shu wei ji chu 俄国传教团成员在北京的日常生活——以1840–1842年戈尔斯基的家书为基础 [The Daily Life of Russian Missionaries in Beijing: Based on the Home Letters of V.V. Gorskiy from 1840 to 1842]. Shi Xue Yue Kan 3: 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Yuqiu 肖玉秋, and Guodong Yan 阎国栋. 2020. Qing dai e luo si guan yu bei jing huang si de jiao wang—yi 19 shi ji 20–30 nian dai e luo si guan cheng yuan ji shu wei ji chu 清代俄罗斯馆与北京黄寺的交往——以19世纪20–30年代俄罗斯馆成员记述为基础 [The Communication between Russian Orthodox Mission and Huangsi Temple in Beijing during Qing Dynasty: Based on the Narrations and Records from the Members of the Russian Orthodox Mission in Beijing from 1820s to 1830s]. Shi Jie Zong Jiao Yan Jiu 4: 36–46. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Yuqiu 肖玉秋, Guodong Yan 阎国栋, and Jinpeng Chen 陈金鹏. 2016. Zhong E Wen Hua Jiao Liu Shi Qing Dai Min Guo Juan 中俄文化交流史 清代民国卷 [A History of the Cultural Exchanges between China and Russia. Qing Dynasty and Republic of China Volume]. Tianjin: Tian Jin Ren Min Chu Ban She, p. 566. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Baichuan 叶柏川, and Baikun Yu 于白昆. 2021. Jin san shi nian lai qing dai zhong e zheng zhi wai jiao wen ti yan jiu shu ping 近三十年来清代中俄政治外交问题研究述评 [A Review of the Research on Sino-Russian Political and Diplomatic Issues in the Qing Dynasty in the Past Thirty Years]. Zhong Nan Min Zu Da Xue Xue Bao (Ren Wen She Hui Ke Xue Ban) 5: 95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Lixia 袁丽霞. 2019. E luo si zhu bei jing zong jiao dai biao tuan han xue jia П.И. ka mian si ji dui zhong yi zai e luo si chuan bo he yan jiu de zuo yong yan jiu 俄罗斯驻北京宗教代表团汉学家П.И.卡缅斯基对中医在俄罗斯传播和研究的作用研究 [Study of Sinologist of the Russian Religious Mission in Beijing P.I. Kamensky on the Role of Spreading and Research of Traditional Chinese Medicine in Russia]. San Wen Bai Jia 6: 251–52. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, Feng 乐峰. 1999. Dong Zheng Jiao Shi 东正教史 [History of Orthodoxy]. Beijing: Zhong Guo She Hui Ke Xue Chu Ban She, p. 366. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, Feng 乐峰. 2002. Dong zheng jiao yu zhong guo wen hua 东正教与中国文化 [Orthodoxy and Chinese culture]. Shi Jie Zong Jiao Wen Hua 3: 47–48. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Baichun 张百春. 2017. Dang dai e luo si dong zheng jiao hui zui gao guan li ji gou 当代俄罗斯东正教会最高管理机构 [The supreme governing body of the contemporary Russian Orthodox Church]. Shi Jie Zong Jiao Wen Hua 2: 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Bing 张冰. 2022. Zhong guo wen hua zai e luo si de chuan bo zhu ti: bi qiu lin shi qi 中国文化在俄罗斯的传播主体:比丘林时期 [Communicators of Chinese Culture in Russia: The Bichurin Period]. Guo Ji Han Xue 4: 156–64+203–4. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Sui 张绥. 1986. Dong Zheng Jiao he Dong Zheng Jiao Zai Zhong Guo 东正教和东正教在中国 [Orthodoxy and Orthodoxy in China]. Shanghai: Xue Lin Chu Ban She, p. 345. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Xuefeng 张雪峰. 2009. A er ba jin ren zai zhong e guan xi shi shang de di wei 阿尔巴津人在中俄关系史上的地位 [The Role of the Albazinians in the History of Sino-Russian Relations]. Xi Bo Li Ya Yan Jiu 5: 72–74. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Xiaoyang 赵晓阳. 2018. E guo dong zheng jiao zhu bei jing chuan jiao tuan de han yi sheng jing yan jiu 俄国东正教驻北京传教团的汉译圣经研究 [A Study of the Chinese Translation of the Bible in the Russian Orthodox Mission in Beijing]. Ji du Zong Jiao Yan Jiu 2: 92–103. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Yongwang 郑永旺. 2010. E Luo Si Dong Zheng Jiao yu Hei Long Jiang Wen Hua: Long Jiang Da Di Shang E Luo Si Dong Zheng Jiao de Li Shi Hui Sheng 俄罗斯东正教与黑龙江文化:龙江大地上俄罗斯东正教的历史回声 [Russian Orthodoxy and the Culture of Heilongjiang: Historical Echo of Russian Orthodox Church on the Long-Jiang Land]. Heilongjiang: Hei Long Jiang Da Xue Chu Ban She, p. 225. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Yongwang 郑永旺. 2015. E luo si dong zheng jiao zai zhong guo de fan rong yu shuai luo 俄罗斯东正教在中国的繁荣与衰落 [The Flourishing and Decline of the Russian Orthodox Church in China]. Xue Shu Jiao Liu 12: 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Nailing 周乃蓤. 2018. Qian long n ian jian e luo si dong zheng jiao shi bi xia zai bei jing de ye su hui shi—ping si mo er zhe fu si ji 《zai hua ye su hui shi ji shu》 乾隆年间俄罗斯东正教士笔下在北京的耶稣会士——评斯莫尔哲夫斯基《在华耶稣会士记述》 [Jesuits in Beijing in the Writings of a Russian Orthodox Clergyman in the 18th Century: Review of Feodosii Smorzhevskii’s Notes on the Jesuits in China]. Guo Ji Han Xue 4: 186–88. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Xiangyu 朱香玉. 2023. Chu zou yu hui gui: 20 shi ji e luo si dong zheng jiao jing wai jiao hui de bian qian 出走与回归: 20世纪俄罗斯东正教境外教会的变迁 [Exodus and Returan: The Transformation of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia in the 20th Century]. Shi Jie Zong Jiao Wen Hua 2: 50–57. [Google Scholar]

| Number | Tenure | Leader |

|---|---|---|

| The 1st Mission | 1715–1728 | Illarion (Lezhaysky) |

| The 2nd Mission | 1729–1735 | Anthony (Platkovsky) |

| The 3rd Mission | 1736–1745 | Illarion (Trusov) |

| The 4th Mission | 1745–1755 | Gervasiy (Lintsevsky) |

| The 5th Mission | 1754–1771 | Amvrosiy (Yumatov) |

| The 6th Mission | 1771–1782 | Nikolai (Tsvet) |

| The 7th Mission | 1781–1795 | Ioakim (Shishkovsky) |

| The 8th Mission | 1794–1808 | Sophroniy (Gribovsky) |

| The 9th Mission | 1808–1821 | Iakinf (Bichurin) |

| The 10th Mission | 1820–1831 | Peter (Kamensky) |

| The 11th Mission | 1830–1841 | Veniamin (Moracevich) |

| The 12th Mission | 1840–1850 | Polikarp (Tugarinov) |

| The 13th Mission | 1849–1859 | Palladius (Kafarov) |

| The 14th Mission | 1858–1864 | Guriy (Karpov) |

| The 15th Mission | 1865–1878 | Palladius (Kafarov) |

| The 16th Mission | 1879–1883 | Flavian (Gorodetsky) |

| The 17th Mission | 1884–1897 | Amfilohiy (Lutovinov) |

| The 18th Mission | 1897–1931 | Innokenty (Figurovsky) |

| The 19th Mission | 1931–1933 | Simon (Vinogradov) |

| The 20th Mission | 1933–1956 | Victor (Svyatin) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, J. The Russian Orthodox Mission in Beijing (XVIII–XX Centuries): Historiography, Missionary Role, and Contemporary Assessment. Religions 2024, 15, 557. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15050557

Li J. The Russian Orthodox Mission in Beijing (XVIII–XX Centuries): Historiography, Missionary Role, and Contemporary Assessment. Religions. 2024; 15(5):557. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15050557

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Jingcheng. 2024. "The Russian Orthodox Mission in Beijing (XVIII–XX Centuries): Historiography, Missionary Role, and Contemporary Assessment" Religions 15, no. 5: 557. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15050557

APA StyleLi, J. (2024). The Russian Orthodox Mission in Beijing (XVIII–XX Centuries): Historiography, Missionary Role, and Contemporary Assessment. Religions, 15(5), 557. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15050557