Brexit’s Illusion: Decoding Islamophobia and Othering in Turkey’s EU Accession Discourse among British Turks

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

- Have you ever felt that you have been treated unfairly in Britain?

- To what extent has the perception of British people towards Turkish-origin people living in Britain changed since 9/11 or 7/7?

- Have you ever withdrawn yourself from certain debates for fear of misinterpretation to avoid stigmatisation, Turkophobia, and Islamophobia? Can you give some examples? How did this make you feel?

2.1. Sovereignty, Colonialism, Islamophobia, Orientalism, and Other Narratives Underlying Brexit

2.2. Turkey’s near Battle for Westernisation

3. Analysis

Synthesis of Turkism, Islamism, and Modernism

I always knew that the use of Turkey was a massive lie to get people to vote leave. Turkish people know Turkey doesn’t have good enough standards to get into the EU. There were videos also at the time saying Turkish people wouldn’t actually want to live in the cold and rainy UK (Laughing). Brexit is the biggest lie. Rather than the government blaming itself … [for its wrongdoings], it was easier to blame the EU and guess what? The migration is going up. I just find it all not logical with the Tories, and I find them racist. Remember Boris Johnson referring to Muslim women as letter boxes? That is my thoughts.(Nazli, 35 years old, Nutritionist, Leeds).

For many years, they have been scared of Turkey. It goes back to the Ottoman times, especially the French… they have always been scared of Turkey. Obviously, a vast number of Turkish citizens would flee through here. That is what they were scared of, too... but then it does not make sense because they opened doors to Romania and Bulgaria; these are not up countries like Turkey. And also, because Turkey is known to be a Muslim country, they are afraid of that. Because there are no Muslims in the EU, so obviously, there is that too; that’s why the UK was scared of Turkey, and that is one of the reasons they have come out of the EU. Turkey might go into the EU for immigration reasons. Basically, they are also scared of the fact that the whole world will be Muslim in the future; it is scary that it will come down to politics in the end. The world as a whole knows that Turkey would fight for their flag to death; it is a commitment, and they know this. As the whole world knows, Turkey is a very powerful country.(Aslı, 55 years old, Working with Autistic Children, London)

It is so complicated, my opinion is if Turkey joins Europe, we enter the EU, and it has no bearing on the UK. It is not the UK’s responsibility; I think we should join the EU; you know, all British people want to go to Turkey every summer they go to Turkey, so why would they incite a negative opinion? So, I do not think British people happened to create a hostile environment on purpose, not really. I also did not feel like I was unwelcomed during the Brexit campaign.(Erdal, 21 years old, Studying Pharmacy, Norwich/London)

I personally wanted to stay in the EU; I did not like to think about it like, ‘Oh, Turkey is joining the EU; we should leave’ I don’t really understand any of them. I did not understand the rationale behind it, I understand why they have used it, but I have never thought about that whilst, you know, voting stay or leave. I did not think about that while doing that; I rather thought, ‘Oh, it is just more beneficial to stay in the EU’ [maintaining] white British. I mean, I don’t think so; I don’t think they have voted because of Turkey, thought ‘Oh, these countries are joining the EU, so we should leave’ I don’t think that was their thought process; I think they just thought the EU as a whole which was not doing great at the moment, we can do better by ourselves kind of mentality.’(Azra, 17 years old, Studying Law and Business, London)

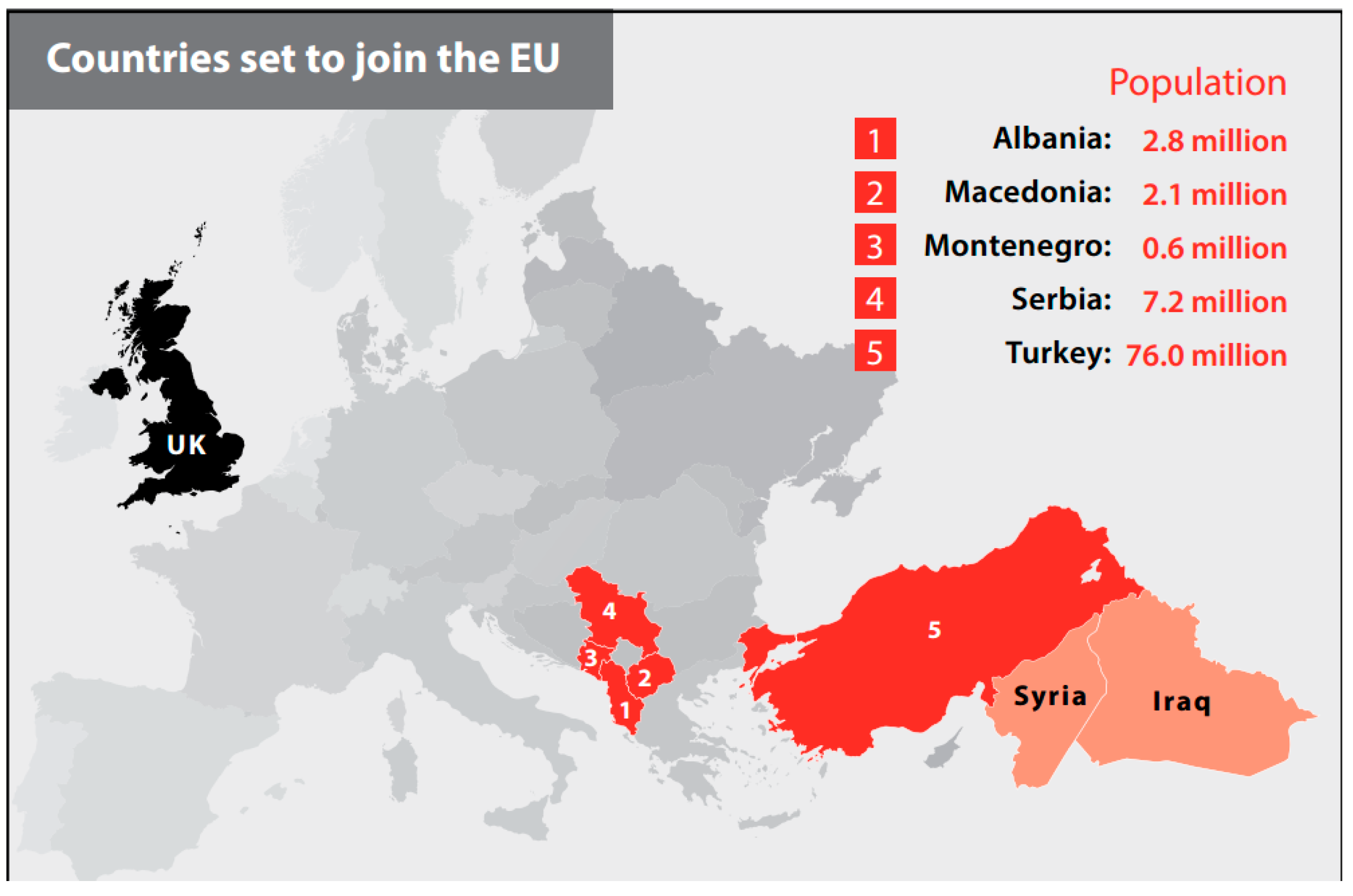

I have a memory, basically, it was in secondary school, during Brexit times, and what happened was people who promoted Brexit came to my school and handed out those leaflets, and I remember taking a look at the back of the leaflet; it was saying ‘can you imagine Turkey joining the EU?’ I was like, wow, because when I think about it, okay, I understand their viewpoint, what they might think. After all, obviously, Turkey has a large population and then a lot of problems there happening politically, and in other ways, so I can imagine so many people migrating to the UK. So, I still did not like the way they used Turkey, though. Can you imagine Turkey is joining, like aliens are coming... they did not have to print that way; it was on the leaflet... it is like, why did they feel the need to put that on… My Turkish friends and I talked about it later. Did they really do that?(Irem, 21 years old, Studying Medicine, Bridlington)

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | UKIP’s controversial Turkey video |

| 2 | In 2021, there were approximately 4 million EU-born residents in the UK, making up 6% of the population and 37% of all those born abroad. The top countries of origin for EU-born residents are Poland (21%), Romania (14%), the Republic of Ireland (10%), Germany (7%), and Italy (7%). M. V. Cuibus (2023, November 20). EU migration to and from the UK. Migration Observatory. |

| 3 | Kemalism is the founding myth of the Turkish Republic, and secularism is an integral part of it. Kemalism inferiorised religion in terms of modernity and progress: in these terms, religion is “reaction”, irtica, and conservative/backward. Being modem is being secular. Modernism and secularism are associated with Western models, extending to the minutiae of everyday life, such as dress, family relations, and personal comportment. Zubaida (1996). |

| 4 | Alevism is a mystical belief that is rooted in Islam and Sufism with some traditions of Christianity and Shamanism. That being said, some segments of the Alevi community argue that features of their belief and culture do not follow Islamic or other religious codes strictly. For simplicity’s sake, I do not delve into further detail about atheist Alevis and Alevis who oppose Islamic religiosity but adhere to Turkish nationalism. A. Dudek (2017). Religious diversity and the Alevi struggle for equality in Turkey. Retrieved from., A. Akdemir (2016). Alevis in Britain: emerging identities in a transnational social space. |

| 5 | Islamophobia is a pervasive kind of racism. Its effect ranges from everyday slow-burning microaggressions to eruptions of violence and murder; its scope extends from classrooms and workplaces to neighbourhoods and state frontiers, from print and social media to the public square. Muslims find themselves framed by Islamophobia in the form of questions about national security, social cohesion, freedom of speech, gender inequality, and cultural belonging. Bhatti (2021). |

| 6 | The Ottoman Empire was the only Muslim great power. It was also the only Muslim state to rule over a vast Christian population, a great number of which resided in Rumelia. Throughout the nineteenth century the Great Powers—Austria-Hungary, Great Britain, France, Russia, and the latecomers, Germany and Italy—engaged in a full-fledged struggle to win the hearts and minds of the Balkan Christians and thus draw them into their own sphere of influence. The Bulgarian revolt became an important step in a chain of events that would eventually result in the creation of a new state, Bulgaria. It could be argued that the April uprising in 1876 led directly to the outbreak of the Russo–Ottoman War of 1877–78, which would change the map of Europe and create a new balance of power in which Germany would play a leading role. A. Kilic (2014). The International Repercussions Of The 1876 April Uprising Within The Ottoman Empire. Uluslararasi Suçlar Ve Tarih (15). |

| 7 | For a discussion of Turkish Orientalism from the 1920s to the present, see (Eldem 2015, pp. 226–69) |

| 8 | The Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, AKP) entered Turkey’s political scene in 2002, established by Recep Tayyip Erdogan. With the increasing power and authoritarianism of religious government in Turkey since 2002, the concept of secular, also known as white Turk, has been denigrated by the current head of state, Recep Tayyip Erdogan himself, on the grounds that white Turkishness has always been the marker of the secular and Kemalist segment of Turks. Tayyip Erdogan, therefore, called himself a black Turk in 2003 in a report published by The New York Times. He said: ‘In this country, there is a segregation of Black Turks and White Turks... Your brother Tayyip belongs to the Black Turks’ (Brennan and Herzog 2014, p. xvi). |

| 9 | This number does not indicate a definite or approximate number since Turkey is currently undergoing a demographic transition; it hosts 4 million refugees, and 3.6 million are Syrians. E. C. Auditors (2018). |

| 10 | Moore and Ramsay (2017). UK media coverage of the 2016 EU Referendum campaign. <https://www.kcl.ac.uk/policy-institute/assets/cmcp/uk-media-coverage-of-the-2016-eu-referendum-campaign.pdf> (accessed on 22 May 2022). |

| 11 | Gilroy contends that the collapse of the Empire has left a lingering sense of melancholy within the identity of white Britain. This melancholy stems from the shift in power dynamics, where the dominance once exerted over various races and nations is now directed towards the marginalisation of those who have sought refuge in the UK, referred to as the ‘escaped’ subjects (Gilroy 2004, p. 120). The British populace was assured prosperity through the British Empire and the exploitation of the Majority World, a trajectory that cemented an unchallenged belief in British racial superiority/exceptionalism (Anne Turner 2022). |

References

- Akdemir, Ayşegül. 2016. Alevis in Britain: Emerging Identities in a Transnational Social Space. Doctoral dissertation, University of Essex, Colchester, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Alpan, Basak. 2019. The Impact of EU-based Populism on Turkey-EU Relations. The International Spectator 54: 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anne Turner, Victoria. 2022. Interrogating whiteness through the lens of class in Britain: Empire, entitlement and exceptionalism. Practical Theology 15: 107–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auditors, E. C. 2018. The Facility for Refugees in Turkey: Helpful Support, but Improvements Needed to Deliver More Value for Money. Luxemburg: European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Babacan, Muhammed. 2021. Young Turks in Britain and Islamophobia: Perceptions, Experiences and Identity Strategies. Ph.D. dissertation, Bristol University, Bristol, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Bale, Tim. 2022. Policy, office, votes–and integrity. The British Conservative Party, Brexit, and immigration. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48: 482–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhambra, Gurminder K. 2017. The current crisis of Europe: Refugees, colonialism, and the limits of cosmopolitanism. European Law Journal 23: 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, Tabetha. 2021. Defining Islamophobia: A Contemporary Understanding of How Expressions of Muslimness are Targeted. London: The Muslim Council of Britain. [Google Scholar]

- Bozdağlioğlu, Yücel. 2008. Modernity, identity, and Turkey’s foreign policy. Insight Turkey 10: 55–75. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2013. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. London: SAGE Publications Ltd., pp. 1–400. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, Shane, and Marc Herzog. 2014. Turkey and the Politics of National Identity: Social, Economic and Cultural Transformation. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Burak, C. O. P. 2019. Countdown for Brexit: What to Expect for UK, EU and Turkey? New York: JSTOR. [Google Scholar]

- Cagaptay, Soner. 2006. Islam, Secularism, and Nationalism in Modern Turkey: Who Is a Turk? London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Çarmikli, Eyüp Sabri. 2011. Caught between Islam and the West: Secularism in the Kemalist Discourse. Ph.D. thesis, University of Westminster, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 2008a. Interventions. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 2008b. Kerim Yildiz Foreword by Noam Chomsky. London and Ann Arbor: Pluto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cowburn, Ashley. 2016. EU referendum: Brexit campaign accused of ‘fanning the flames of division’ with controversial map. The Independent, June 6. [Google Scholar]

- Cuibus, Mihnea V. 2023. EU Migration to and from the UK; Migration Observatory. Available online: https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/briefings/eu-migration-to-and-from-the-uk/ (accessed on 8 April 2024).

- Dudek, A. 2017. Religious Diversity and the Alevi Struggle for Equality in Turkey. Jersey City: Forbes. [Google Scholar]

- Eldem, Edhem. 2015. The Ottoman Empire and Orientalism: An awkward relationship. In After Orientalism. Leiden: Brill, pp. 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Ergin, Murat. 2016. “Is the Turk a White Man?”: Race and Modernity in the Making of Turkish Identity. Leiden: Brill, Vol. 95. [Google Scholar]

- Garner, Steve. 2012. A moral economy of whiteness: Behaviours, belonging and Britishness. Ethnicities 12: 445–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, Steve. 2023. Not in a Relationship. In The Oxford Handbook of Superdiversity. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 359. [Google Scholar]

- Gasimzade, İlhama. 2018. Brexit: The impact on the United Kingdom and Turkey. Uluslararası Beşeri Bilimler ve Eğitim Dergisi 4: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Gilroy, Paul. 2004. After Empire. London: Routledge, Vol. 105. [Google Scholar]

- Gilroy, Paul. 2011. The closed circle of Britain’s postcolonial melancholia. In The Literature of Melancholia: Early Modern to Postmodern. New York: Springer, pp. 187–204. [Google Scholar]

- Gökalp, Ziya. 1969. Türkçülüğün Esasları. İstanbul: Varlık Yayınevi. [Google Scholar]

- Göle, Nilüfer. 1997. Secularism and Islamism in Turkey: The making of elites and counter-elites. The Middle East Journal 51: 46–58. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, Michele, Vivian Gerrand, and Anna Halafoff. 2020. Australia: Diversity, neutrality, and exceptionalism. In Routledge Handbook on the Governance of Religious Diversity. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 296–308. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, Tiffany. 2020. Race, ethnicity, and documentation status have brightened boundaries of exclusion in the US and Europe. In Routledge International Handbook of Contemporary Racism. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ker-Lindsay, James. 2018. Turkey’s EU accession as a factor in the 2016 Brexit referendum. Turkish Studies 19: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Kamran. 2023. The Perceptions of Sharia: Beyond Words and Intentions. In Media Language on Islam and Muslims: Terminologies and Their Effects. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 225–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kilic, Ayten. 2014. The International Repercussions Of The 1876 April Uprising Within The Ottoman Empire. Uluslararasi Suçlar ve Tarih 15: 11–45. [Google Scholar]

- Koegler, Caroline, Malreddy Pavan Kumar, and Tronicke Mariena. 2020. The colonial remains of Brexit: Empire nostalgia and narcissistic nationalism. Journal of Postcolonial Writing 56: 585–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Geoffrey. 1961. The Emergence of Modern Turkey. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Martin, and Gordon Ramsay. 2017. UK Media Coverage of the 2016 EU Referendum Campaign. Available online: https://www.kcl.ac.uk/policy-institute/assets/cmcp/uk-media-coverage-of-the-2016-eu-referendum-campaign.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2022).

- Onay, Özge, and Gareth Millington. 2024. Negotiations with whiteness in British Turkish Muslims’ encounters with Islamophobia. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öniş, Ziya. 2004. Turkish modernisation and challenges for the new Europe. Perceptions: Journal of International Affairs 9: 5–28. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes, James, and Natalie-Anne Hall. 2020. Racism, nationalism and the politics of resentment in contemporary England. In Routledge International Handbook of Contemporary Racism. Solomos: Routledge, pp. 284–99. [Google Scholar]

- Said, Edward W. 1978. Orientalism, 1st ed. New York: Pantheon Books. [Google Scholar]

- Saini, Rima, Michael Bankole, and Neema Begum. 2023. The 2022 Conservative leadership campaign and post-racial gatekeeping. Race & Class 65: 03063968231164599. [Google Scholar]

- Sayyid, Bobby S. 1997. A Fundamental Fear: Eurocentrism and the Emergence of Islamism. London: Zed Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sealy, Thomas, and Tariq Modood. 2020. The United Kingdom: Weak establishment and pragmatic pluralism. In Routledge Handbook on the Governance of Religious Diversity. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 46–56. [Google Scholar]

- Solomos, John, and Les Back. 1996. Racism and Society. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Somay, Bülent. 2014. The Psychopolitics of the Oriental Father: Between Omnipotence and Emasculation. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Türkmenoğlu, Ahmet T. 2022. Orientalist Traces in the Brexit Referendum: A Semiotic Analysis on the Brexit Posters. Erciyes İletişim Dergisi 9: 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakil, AbdoolKarim, and S. Sayyid. 2023. Towards a Grammar of Islamophobia. In Media Language on Islam and Muslims: Terminologies and Their Effects. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 29–56. [Google Scholar]

- Völkel, Jan C. 2019. The impact of Brexit on the European Parliament: The role of British MEPs in Euro-Mediterranean affairs. In Brexit and Democracy: The Role of Parliaments in the UK and the European Union. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 263–91. [Google Scholar]

- Wellings, Ben. 2018. Brexit and English identity. In The Routledge Handbook of the Politics of Brexit. London: Routledge, pp. 147–56. [Google Scholar]

- Yegenoglu, Meyda. 2012. Islam, Migrancy, and Hospitality in Europe. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Zubaida, Sami. 1996. The survival of Kemalism. Cahiers d’études sur la Méditerranée Orientale et le Monde Turco-Iranien. Vol. 21, pp. 291–96, Online since 5 May 2006, Connection on 8 September 2020. Available online: https://journals.openedition.org/cemoti/571?lang=en (accessed on 8 April 2024). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Onay, Ö. Brexit’s Illusion: Decoding Islamophobia and Othering in Turkey’s EU Accession Discourse among British Turks. Religions 2024, 15, 498. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15040498

Onay Ö. Brexit’s Illusion: Decoding Islamophobia and Othering in Turkey’s EU Accession Discourse among British Turks. Religions. 2024; 15(4):498. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15040498

Chicago/Turabian StyleOnay, Özge. 2024. "Brexit’s Illusion: Decoding Islamophobia and Othering in Turkey’s EU Accession Discourse among British Turks" Religions 15, no. 4: 498. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15040498

APA StyleOnay, Ö. (2024). Brexit’s Illusion: Decoding Islamophobia and Othering in Turkey’s EU Accession Discourse among British Turks. Religions, 15(4), 498. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15040498